Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, October 17, 1882, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, October 17, 1882

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: June 1, 2019 [EBook #59649]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| "THEIR GIRL." |

| "JUST LIKE A COMET!" |

| THE IGUANA. |

| THE CRUISE OF THE CANOE CLUB. |

| HANDICRAFT. |

| THE BATTLE OF LAKE BORGNE. |

| WHO WON THE BICYCLE? |

| AUTUMN LEAVES. |

| THE DARING MICE. |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| vol. iii.—no. 155. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, October 17, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Author of "Toby Tyler," "Tim and Tip," "Mr. Stubbs's Brother," etc.

The morning on which the famous excursion was to be made dawned as bright and clear as the most exacting boy could have wished, and Johnny and Jimmy were in the best possible spirits.

The boat on which they were to start was to leave the pier at ten o'clock, and as early as six they had concluded the most elaborate of toilets. They were dressed so much that the effort to move about in such a manner as not to destroy their general elegance really cost them no little pain.

Johnny had been up some time before it was light, making such a racket as he moved about the house, bent on getting this thing or that which would add to his general appearance, that Mother Brown had jumped out of bed twice in the greatest alarm, believing burglars were in the house. He had not only made his own toilet, but he had aided Jimmy in his, until both were in such a state of gorgeousness that they almost feared to walk through the streets because of the excitement they might cause.

The night previous Johnny had invested five cents in butter, greatly to the mystification of Jimmy, and when the work of dressing began, he brought it forward triumphantly, bestowing such liberal quantities upon his own head and Jimmy's that each particular hair lay down so flat that the most furious gust of wind could not have disturbed it. It was fully half an hour before Johnny, with the aid of an old shoe-brush, could arrange this portion of the toilet to please him; but it was accomplished at last, and the remainder of the work begun.

During the first week of the summer Jimmy had taken the place, for one day, of a friend who sold papers on the Harlem Railroad, and in order that he might improve his personal appearance somewhat had purchased a paper collar. Of course he had worn it until it was so thoroughly soiled that it would have been difficult to have said what its original color was.

This Johnny used for a pattern, and from a piece of white paper had made two collars, which had the merit of being clean, even if they did not fit as well as they might have done. They were rather high in the back and low in front, with a decided tendency to wrinkle; but those little defects Johnny was certain would not be noticed in the general beauty of the whole.

Jimmy's coat, which he had borrowed from Tom Dowling for this special occasion, had originally been brown, trimmed with fur, and many sizes too large for him. In the years that had passed since it was new it had not grown smaller, but the color had departed from it, and what had once been fur now looked like strips of very poor leather. But Jimmy was perfectly satisfied with it, since it was large enough to enable him to conceal the lack of vest, and short enough to leave fully three inches of his linen trousers exposed to view.

He wore a felt hat with an abundance of brim and a sad deficiency of crown, while his neck-tie was a modest and unassuming one, with alternate red and yellow stripes about an inch wide. With the exception, perhaps, of his coat, it was in his shoes that he took the greatest pride. It is true that there were several holes in them, but he had blackened them and his feet so skillfully that an ordinarily careless glance would have failed to show that they were other than whole.

While Jimmy believed that he looked thoroughly genteel, he freely admitted that Johnny would have carried away the prize for fashionable attire had any been offered. Not because his clothes were any more expensive than were his partner's, but because it might be said they were more seasonable.

Johnny was clothed entirely in brown linen. Mother Brown had on hand a suit belonging to her son, who had inadvertently left it at home when he ran away to sea, and this she sold to Johnny for thirty cents, to be paid in ten weekly installments.

Young Brown must have been very tall, or else his clothes had been made in expectation of his growing very rapidly, for the coat, in its original condition, nearly dragged on the ground when Johnny tried it on. Mrs. Brown had remedied this defect, however, by making a fold about five inches wide across the entire garment, which both the boys thought a great improvement. The trousers had simply been cut off at the bottom, so that they were a good fit so far as length was concerned, and it was very little trouble to fold them in around the waist.

Mrs. Brown, without extra charge, had starched the garments very stiff, so that they would stand out boldly without betraying the fact that the wearer did not occupy all the space in them he might have done had he been about twice as large as he was. When Johnny had the clothes on, with a brilliant green neck-tie to enhance the effect, it must have been a prejudiced party who would not have admitted that it was a striking costume. His shoes were not blackened quite as brilliantly as were his partner's, but the reason for this apparent neglect was that, not having as many holes in them as Jimmy's had, there was no reason for quite so high a polish.

As they had anticipated, they did attract considerable attention as they walked into the City Hall Park, with so much time at their disposal that they were not obliged to hurry in order to keep their engagement. Even the men looked at them with no slight degree of interest, while the boys proved their admiration by greeting them with all kinds of criticism, some less complimentary than others. Some of the boys Johnny spoke with kindly, as if to show that even if he was magnificent, he was not proud; but others he paid no attention to whatever, giving as a reason to Jimmy that when they were dressed as they were he thought that some distinction should be made by them between the reputable newspaper merchants and those whose credit had been impaired by their own misdeeds.

Very many of their acquaintances in business knew about "their girl," and also knew of the accident she had met with, therefore they readily understood by the display of costumes that Katy was to be released from the hospital. Nearly all of them sent some message of congratulation to the black-pin girl that her recovery was complete, and one even offered to loan the boys ten cents, without other security than their word, if they were going to take "their girl" out for a good time.

Jimmy would have accepted this offer eagerly, for their funds were so limited that even the slightest addition would have been welcome; but Johnny prevented him at once by saying to the would-be lender:

"We're much obliged to yer, Jack, and we'll do the same for you some time; but yer see we couldn't think of takin' Katy out on borrowed money, for she wouldn't have as good a time if she knew it."

Then the boys walked directly to the hospital, arriving there some time before eight o'clock, and for more than an hour were they obliged to wait in the street, suffering greatly from the heat and their fear lest they should disarrange their carefully made toilets.

It seemed as if Katy must have been as impatient for the meeting as they were, for just at nine o'clock she came out of the hospital gates, looking pale and worn, but as happy as she ever was in her life. She had on the new dress, and even though it was not made in the latest fashion, nor of the richest materials, the boys were very much surprised by the improvement in her appearance.

"You look like a reg'lar swell!" exclaimed Johnny, approvingly, and then he turned slowly around in front of her, that she might see and admire him.

"I hain't sure but the dress looks jest as well as if it was red," said Jimmy, too much "dressed up" even to rub his chin, and then he too began to revolve for Katy's benefit. For some moments it was truly a mutual admiration society of three members.

Then after they had sufficiently complimented each other, and after Katy had vainly tried to thank the boys for their kindness, Johnny announced the programme for the day, explaining that the excursion was necessary as a means of showing their thankfulness for the recovery of "their girl."

"We're goin' to be reg'lar folks, ain't we?" cried Katy, when, to her great pleasure, the boys led the way to the nearest elevated railroad station, thus giving her the opportunity of having such a ride as she had long desired.

"I guess you'll think so before we get back," replied Johnny, decidedly; and when he paid thirty cents for the ride, thereby diminishing their funds sadly, he looked at Katy in a satisfied way, happy at being able to give her so much pleasure.

At the steamboat pier they mingled with the crowd that would probably spend more money than they, but yet have less enjoyment, and it was as much as Katy could do to see everything around her, so many times did she look at her dress—new and whole.

During the sail Ikey Moses had no reason to complain that the boys did not keep their word in regard to patronizing him, for hardly five minutes went by without their making a purchase of some kind. Katy had pea-nuts, apples, candy, and cakes piled up on the seat in front of her until it seemed certain that if she ate them all she would be obliged to return to the hospital.

When the boys were not gladdening Ikey Moses' heart by buying his wares, they were busily engaged in pointing out to Katy the different points of interest in the harbor, or in telling her of the wonderful things she was to see; and in this way the time passed so rapidly that before it seemed possible they could have been away from the pier ten minutes they were at Coney Island.

Having spent so much of their wealth on the steamer, it was necessary for them to be careful of their money if they expected to get any dinner, and in order that the purchases might be made more judiciously, Jimmy gave his portion of the funds to Johnny, thereby making him responsible for the manner in which the forty remaining cents were spent.

If they did not have quite as much money, they felt of just as much importance as any one on the beach, and they walked along in all the glory of good clothes and a contented mind. They would have enjoyed a swim—at least the boys would—but bathing suits were necessary; and after Johnny had vainly tried to persuade the man at the bath-house that ten cents ought to be enough for the hire of three suits, they concluded that perhaps they ought not waste so much time in the water, when they could be sight-seeing.

Never before had the three been on an excursion "dressed up," and they enjoyed their own condition quite as much as they did that which they saw. Even the dinner was a success, for Johnny bought one plate of chowder, with crackers for three, and on the clean though rather warm sand they sat around the one plate, quite as contented as if they had had all that money could buy.

It was not until the last trip of the boat on which Ikey Moses was employed that they started for home, and then they gave their friend no extra work in waiting upon them, for they had such a trifling sum in the treasury—that is to say, in Johnny's pockets—that they would be able to buy only a small stock of papers the next morning.

But they insisted on introducing Ikey to Katy, and obliged him to hear a detailed account of the manner in which they celebrated the release of "their girl" from the hospital. Katy very obligingly stood up that Master Moses could see her dress from every point of view, and long and loud was the discussion the boys entered into as to what color would have been the most beautiful, for they all condemned Mrs. Spratt's taste in the matter.

It was well that they had not arranged to spend more than one day at the sea-shore, for the costume of the boys was not well calculated to stand much service. As it was, the starch had departed so entirely from Johnny's clothes that they hung limp and in folds around him, while the improvised paper collars were such a wreck that they were discarded before the party reached home.

By some means the secret of where they were going had been discovered by their friends, and when they landed they found as many as twenty waiting to greet Katy, as well as to learn all the particulars of this excursion which had been made in such a fashionable manner, so far as clothes were concerned.

It was not until a late hour that night that Mother Brown's boarders retired, and just before they did go to bed they startled the old lady out of her first sleep and a portion of her senses by giving three rousing cheers for Johnny, Jimmy, and "their girl."

A little maid, so wondrous wise

In speech, and with observing eyes,

Was wakened at the early morn,

And to an eastern window borne,

That she might see the comet bright,

And nevermore forget the sight.

The shining star was pointed out,

Its head with splendor rayed about,

And then, outspreading like a dress,

Its train of dazzling loveliness,

And all the points that made it far

More beautiful than any star.

The little maiden gazed, and gazed;

At such a wonder much amazed;

And never had she seen before

The morning sky so spangled o'er,

Or fancied that the silver moon

Staid out so late, or rose so soon.

The stars kept winking overhead,

As if they longed to be in bed,

And two bright orbs in mamma's lap

Were closed to finish out their nap,

While still the comet swept the skies,

The marvel of admiring eyes.

Next day within the nursery

The little maiden chanced to be,

When baby was on dress parade,

Its pretty finery well displayed,

As high in nurse's arms 'twas held

With all its frowns and fears dispelled.

Its flaxen head, with aureole bright,

Its lengthy train of dazzling white,

Were noted by the maid so wise,

Who stood, with widely opened eyes,

And said, "It looks"—her speech was slow—

"Just like a comet!" And 'twas so.

"I DO LOVE DOLLY SO MUCH!"

"I DO LOVE DOLLY SO MUCH!"

The iguana is a very large and very ugly-looking lizard, which is found all through the American tropics. It measures fully five feet in length, its body being over two feet, and its long tapering tail nearly three. It is covered with scales, and its usual color is green shaded with brown. Iguanas possess, however, to an extent exceeded only by the chameleon, the power of changing their colors, the brilliant green becoming transformed in an instant, through the influence of fear or anger, into darker hues, or even into black.

The eyes of the iguana are large, as is also its head, while a pouch, serrated in front, depends from the lower jaw. It also has a serrated tuft, like a comb, extending along its back and half the length of its tail. Its legs are long, and its feet are armed with strong claws, which enable it to climb about among the branches of the trees with the greatest rapidity.

One would think that so large a creature would be slow and clumsy in its movements, but no squirrel or small lizard could be lighter and more active than the iguana. It is as much at home in the water as on the land, and can remain under the surface a long time without coming up to breathe. When swimming, it propels itself ahead with marvellous quickness by waving its long tail from side to side, and using its paws very much in the manner that a boy would use his arms.

A singular instance of the power and velocity of the iguana is related by an English traveller. On the bank of a river he came suddenly upon one of these huge lizards lying concealed in the tall grass. Alarmed by the appearance of a man, whom the iguana recognizes as its deadly enemy, the creature sprang into the water; but in place of swimming, so great was the force of its spring that it skimmed across the broad river, scarcely touching the surface with its feet. In two minutes it reached the sand-banks of the opposite shore, and vanished among the bushes.

Although of such immense size, the weight of the iguana is scarcely ten pounds, which fact probably accounts for its extreme lightness of motion.

It is not very pleasant for a person of civilized taste to think of eating a lizard, but the flesh of the iguana is considered a great delicacy. Indians hunt it with bows and arrows, and when brought to market it is sold for a high price. Another method of catching it is to slip a noose around its neck as it sits in fancied security upon the branch of a tree. The country people roast it in hot ashes, and the meat is said to be tender and juicy, and very delicate in flavor. The eggs, too, which are rich and oily, are favorite eating. They are about as large as a dove's eggs, and of a glistening white. The iguana buries them, eighteen or twenty together, in a hole in the sand, and leaves them to be hatched by the sun.

The little ones are left to take care of themselves as best they can. Humboldt, the great traveller and naturalist, found nests of young iguanas which were apparently just hatched. They were not over four inches long, and were very spry little things, and much prettier than later on in their lizard life.

The iguana will never attack an enemy, but when cornered, is a valiant fighter. It will hiss and spit like a cat, and erecting the comb on its back, it will spring at its enemy, dealing powerful blows with its tail, and biting with its sharp teeth. The following story is told by an Australian settler of an encounter between an iguana and a snake: "I saw a heavy fight the other day between a large iguana and a tree-snake about five feet long. They were both going to pay a visit to a ''possum' which lived in a big hole in a tree. Each went up a different side of the tree, and met at the entrance to the hole, and then the row began. The great lizard squealed in a most defiant manner, and the snake was in no way behindhand in hissing. In fact, strong reptile language filled the air for fully ten minutes before the fight commenced; then they went at it. But the iguana was too much for the snake, and killed him in a few minutes, seeming to take no notice of a good many bites, for the snake fought pluckily. The ''possum' profited by this chance to escape to a top limb of the tree, where he sat blinking in the sunlight, till presently a great eagle-hawk came swooping down on him, and was carrying him off, when I put in a word, or rather a charge of shot, and so earned 2s. 6d., that is, head-money."

Iguanas which have been captured have at first acted in a most violent manner, hissing and snapping at everything which approached the cage; but they soon grow accustomed to captivity, and will become so tame as to take lettuce leaves and other food from the hands of the keeper. But confinement is not healthy for these large creatures, and they lie sluggishly in their cages, taking no notice of their surroundings, and doing nothing but eat, until by degrees they shrivel up and die.

THE IGUANA.

THE IGUANA.

Author of "The Moral Pirates," "The Cruise of the 'Ghost,'" etc., etc.

Charley and Harry took in their sails, keeping the canoes head to sea with an occasional stroke of the paddle. When all was made snug, and the moment for turning the canoes had arrived, they realized that they were about to attempt the most hazardous feat of the whole cruise.

"Can we do it?" asked Harry, doubtfully.

"We've got to do it," replied Charley.

"Why can't we unship our rudders and back water till we get to the reeds?"

"It might be possible, but the chances are that we would be swamped. The seas would overtake us, and we couldn't keep out of the way of them. No, we've got to turn around and sail back in the regular way."

"You know best, of course," said Harry; "but what's the use of taking in our sails before we turn around? We'll have trouble in setting them again with the wind astern."

"We can turn the canoes quicker without sails than we could with the sails set, and every second that we can gain is worth something. Besides, if we are capsized, it will be an advantage to have the sails furled. But we're wasting time. Let your canoe get right astern of mine, so that mine will keep a little of the sea off of you; then watch for two or three big seas, and turn your canoe when they have passed."

Harry followed his friend's instructions, and succeeded in turning his canoe without accident. Then Charley, getting into the lee of the Sunshine, did his best to imitate Harry's successful feat. He managed to turn the canoe, but while in the act a heavy sea rolled into the cockpit and filled the Midnight absolutely full. The beef bladders, however, kept the canoe afloat, but she lay like a log on the water, and every successive wave swept over her.

Charley did not lose his presence of mind. He shouted to Harry to run up his sail and keep his canoe out of the way of the seas, and then he busied himself shaking out the reef of his mainsail, so that he could set the whole sail. The moment the canoe felt the strain of her canvas she began to rush through the water in spite of her great weight, and no more seas came aboard her. Steering with one hand, Charley bailed with his hat with such energy that he soon freed the canoe of water. Meanwhile he rapidly overtook Harry, and reached the reeds, while the Sunshine was a quarter of a mile behind him.

Tom and Joe were found sitting in their canoes and suffering the pangs of hunger. Charley put on dry clothes, while Harry prepared a lunch of dried beef and crackers, after which the canoeists resigned themselves as cheerfully as they could to spending the rest of the afternoon and the night in the reeds. It was not a pleasant place, but the wind kept the mosquitoes away, and the boys managed to fall asleep soon after sunset. The wind died out during the night, and the boys found, the next morning, that only a few rods below the place where they had spent the night there was an open channel by which they could easily have reached the shore. This was rather aggravating, and it increased the disgust with which they remembered Lake St. Peter and its reed-lined shores.

The voyage down the St. Lawrence seemed monotonous after the excitement of running the Magog rapids, and the various adventures of the sail down the Richelieu. The St. Lawrence has very little shade along its banks, for, owing to the direction in which it runs, the sun shines on the water all day long. The weather was exceedingly hot while the boys were on the river, and on the third day after leaving Lake St. Peter they suffered so greatly that they were afraid to stay on the water lest they should be sunstruck. Going ashore on the low sandy bank, they were unable to find a single tree, or even a hillock large enough to afford any shade. They thought of drawing the canoes ashore, and sitting in the shade of them, but there was not a breath of air stirring, and the very ground was so hot that it almost scorched their feet. Half a mile away on a meadow they saw a tree, but it was far too hot to think of walking that distance. They decided at last to get into their canoes and to paddle a few rods farther, to a place where a small stream joined the river, and where they hoped to find the water somewhat cooler for bathing.

On reaching the mouth of the little stream the bows of the canoes were run ashore, so that they would not float away, and the boys, hastily undressing, sprang into the water. They had a delightful bath, and it was not until they began to feel chilly that they thought of coming out and dressing. Tom was the first to go ashore, and as he was wading out of the water, he suddenly felt himself sinking in the sand. Harry and Joe attempted to land a few yards from the place where Tom was trying to drag his feet out of the clinging sand, and they too found themselves in the same difficulty. Harry at once perceived what was the matter, and, making frantic efforts to get to the shore, cried out to his comrades that they were caught in a quicksand.

The struggles made by the three boys were all in vain.[Pg 806] When they tried to lift one foot out of the sand, the other foot would sink still deeper. It was impossible for them to throw themselves at full length on the quicksand, for there were nearly two feet of water over it, and they were not close enough together to give one another any assistance. By the time Charley fully understood the peril they were in, Tom had sunk above his knees in the sand, and Joe and Harry, finding that they could not extricate themselves, were waiting with white faces and trembling lips for Charley to come to their help.

Charley knew perfectly well that if he ventured too near the other boys, he would himself be caught in the quicksand, and there would be no hope that any of them could escape. Keeping his presence of mind, he swam to the stern of one of the canoes, set it afloat, and pushed it toward Tom, so that the latter could get hold of its bow. He then brought two other canoes to the help of Joe and Harry; and when each of the three unfortunate canoeists was thus furnished with something to cling to, he climbed into his own canoe.

"What are we to do now?" asked Harry.

"Just hold on to your canoes until I can tow them out into the stream. You can't sink while you hang on to them."

"Won't the canoes sink with us?" asked Tom.

"Not a bit of it. You wouldn't sink yourselves if you could lie down flat on the quicksand. I was caught in a quicksand once, and that's the way I saved myself."

"I hope it's all right," exclaimed Joe; "but it seems to me that you'll have to get a derrick to hoist me out. But I'm not complaining. I can hang on to my canoe all day, only I don't want to be drowned and buried both at the same time."

Charley, meanwhile, was busily making his canoe fast to Tom's canoe with his painter. When this was done, he paddled away from the shore with all his might, while Tom tried to lift himself out of the quicksand by throwing the weight of his body on the canoe. Slowly Tom and his canoe yielded to the vigorous strokes of Charley's paddle, and were towed out into deep water. By the same means Joe and Harry were rescued, and then the entire fleet—Charley paddling, and the others swimming and pushing their canoes—floated a short distance down stream, and finally landed where the sand was firm and hard.

"What should we have done if you'd got into the quicksand, as we did?" said Harry to Charley, as they were dressing.

"By this time we should all have disappeared," replied Charley.

"I shall never go ashore again while we're on this river without making sure that I'm not walking into a quicksand," continued Harry. "It was awful to find myself sinking deeper and deeper, and to know that I couldn't help myself."

"Very likely there isn't another quicksand the whole length of the St. Lawrence," said Charley. "However, it's well enough to be careful where we land. I've noticed that where a little stream joins a big one the bottom is likely to be soft; but, after all, a regular dangerous quicksand isn't often met. I never saw but one before."

"Tell us about it," suggested Joe.

"No; we've talked enough about quicksands, and the subject isn't a cheerful one. Do you see that pile of boards? Let's make a board shanty, and go to sleep in it after we've had some lunch. It will be too hot to paddle before the end of the afternoon."

A shanty was easily made by leaning a dozen planks against the top of the pile of boards, and after a comfortable lunch the boys took a long nap. When they awoke they were disgusted to find that their canoes were high and dry two rods from the edge of the water. They had reached a part of the river where the tide was felt, and without knowing it they had gone ashore at high tide. They had to carry the canoes, with all their contents, down to the water, and as the receding tide had left a muddy and slippery surface to walk over, the task was not a pleasant one. They congratulated themselves that they had not gone ashore at low tide, in which case the rising of the water during the night would have carried away the canoes.

Sailing down the river with a gentle breeze, and with the help of the ebbing tide, the canoeists came to the mouth of a small river which entered the St. Lawrence from the north. They knew by means of the map that the small river was the Jacques Cartier. It was a swift, shallow, and noisy stream, flowing between high, precipitous banks, and spanned by a lofty and picturesque bridge. Taking in their sails, the boys entered the Jacques Cartier, picking their way carefully among the rocks, and making headway very slowly against the rapid current. They stopped under the bridge, just above which there was an impassable rapid, and went ashore for lunch.

Near by there was a saw-mill, and from one of the workmen who came to look at the canoes the boys heard wonderful reports of the fish to be caught in the stream. It was full of salmon—so the man said—and about nine miles from its mouth there was a pool where the trout actually clamored to be caught. The enthusiasm of the canoeists was kindled; and they resolved to make a camp on the bank of the stream, and to spend a few days in fishing.

After having thus excited his young hearers, the workman cruelly told them that the right to fish for salmon was owned by a man living in Montreal, and that any one catching a salmon without permission would be heavily fined. The trout, however, belonged to nobody, and the boys, though greatly disappointed about the salmon, would not give up their plan of trout fishing. They hired two carts from a farmer living a short distance from the river, and placing their canoes on the carts, walked beside them over a wretchedly rough road until they reached a place deep in the woods, where a little stream, icy cold, joined the Jacques Cartier. Just before entering the latter the little stream formed a quiet pool, in which the trout could be seen jumping. The point of land between the trout stream and the river was covered with a carpet of soft grass, and on this the canoes were placed and made ready to be slept in.

"THEY FOUND A BEAR FEASTING UPON THE REMAINS OF THEIR

BREAKFAST."

"THEY FOUND A BEAR FEASTING UPON THE REMAINS OF THEIR

BREAKFAST."

The workman at the mouth of the Jacques Cartier had not exaggerated the number of trout in the pool. It was alive with fish. The boys were charmed with the beauty of their camping ground and the luxury of their table. It was rather tiresome to walk two miles every day to the nearest farm-house for milk, but with the milk rice griddle-cakes were made, and upon these and fresh-killed trout the canoeists feasted for three delightful days.

They had one real adventure while on the Jacques Cartier. One day when they returned to their camp from an exploration of the upper part of the trout stream, they found a bear feasting upon the remains of their breakfast and their bottle of maple syrup, which he had upset and broken. The animal was full-grown, and looked like a very ugly customer; but no sooner did he see the boys than he started on a rapid run for the woods. By the time the boys had found their pistols and were ready to follow him, the bear had disappeared, and though they hunted for him all the rest of the day they could not find him. Had the bear taken it into his head to hunt the boys, he would probably have been much more successful, for their pistol-bullets would have had little effect upon him, except to sharpen his appetite for tender and wholesome boy's-meat.

It is the practice in some families to have each child taught some common useful work or handicraft. There are two families which in regard to wealth and social position may be said to stand as high as any in this world where great attention is paid to this kind of training.

The young Rothschilds are all made to use their hands, and the sons and grandsons of the Emperor of Germany have been regularly instructed in various trades. The old Kaiser has a room in his palace at Berlin where he can read books that have been bound by the Crown Prince, and sit in chairs made by his grandson.

I often think we would all be happier if we followed the example thus set. I do not fancy that either the kings of men or the kings of money have educated their children in this way under any belief that they might be compelled to get their living by the labor of their hands. If the Rothschilds were to be bankrupt, and the Hohenzollerns driven into exile, the former could always make a livelihood as business men, and the latter as officers and commanders in an army.

It is not, then, to provide against any possible accidents to their fortunes that they have been taught other work than that which they are called on as princes and bankers to spend their lives in doing. It has been rather to teach them habits of patience and industry in doing work where no hope of gain or fame is present to urge the worker on. We can all take pains when we want to make money or get some reputation, but very few of us think that whatever is worth doing at all is worth doing well and in a workman-like manner, although it is merely a pastime.

There is another view of the question which must not be left out of sight. We are all of us very fond of using our hands, and if we do not use them to make something, we use them to destroy something. In this respect girls are generally better educated than boys, for they all learn sewing without any idea of ever being seamstresses.

Give a girl a needle and thread, and she amuses herself with a hundred useful things. Give a boy a jackknife, and he first cuts his fingers, and then cuts the school-desks. Even when we have a box of tools given us, we are never made to learn how to use them properly. Jig-saws and the like never seemed to quite satisfy the boyish mind; the work was too "finicking," and not varied enough; in fact, it was to real work what fancy embroidery is to plain needle-work, and struck one as being nearly useless.

Handicrafts differ in one peculiar respect from the labors to which most of us will have to give our time. We have in everything we do to use our hands and our brains, but in most cases we shall have to use our hands to carry out the work of our brains. In handicrafts we have to use our brains to guide and direct our hands, and our minds, instead of being continually on the strain, have merely to superintend a mechanical operation. Our thoughts are employed without the trouble of thinking.

When the British made up their minds, near the end of the year 1814, to take New Orleans, and thus to get control of the Mississippi River, there seemed to be very little difficulty in their way.

So far as anybody on either side could see, their only trouble was likely to be in making a landing. If they could once get their splendid army on shore anywhere near the city, there was very little to prevent them from taking the town, and if they had taken it, it is easy to see that the whole history of the United States would have been changed.

They did make a landing, but they did not take New Orleans, and perhaps I shall hereafter tell how and why they failed. At present I want to tell how they landed.

The expedition consisted of a large fleet bearing a large army. At first the intention was to sail up the Mississippi River, but General Jackson made that impossible by building strong forts on the stream, and so it was necessary to try some other plan.

It happens that New Orleans has two entrances from the sea. The river flows in front of the city, and by that route it is about a hundred miles from the city to the sea; but just behind the town, only a few miles away, lies a great bay called Lake Pontchartrain. This bay is connected by a narrow strait with another bay called Lake Borgne, which is connected directly with the sea.

Lake Borgne is very shallow, but the British knew little about it. They only knew that if they could land anywhere on the banks of Lake Borgne or Lake Pontchartrain they would be within an easy march of New Orleans.

Accordingly, the fleet bearing the British army, instead of entering the mouth of the Mississippi, and trying to get to New Orleans in front, sailed in by the back way, and anchored near the entrance of Lake Borgne.

Here the British had their first sight of the preparations made to resist them. Six little gun-boats, carrying twenty-three guns in all, were afloat on the lake under command of Lieutenant Thomas Ap Catesby Jones. These gun-boats were mere mosquitoes in comparison with the great British men-of-war, and when they made their appearance in the track of the invading fleet, the British laughed and wondered at the foolhardiness of the American commander in sending such vessels there.

Lieutenant Thomas Ap Catesby Jones knew what he was about, however, as the British soon found out. He sailed up almost within cannon-shot of the enemy's ships, and they, of course, gave chase to him. Then he nimbly sailed away, with the fleet after him. Very soon a large man-of-war ran aground; then another and another struck the bottom, and the British Admiral began to understand the trick. It was evident that Lake Borgne was much too shallow for the large ships, and so the commander called a halt, and transferred the troops to the smaller vessels of the fleet.

When this was done the chase was begun again by the smaller ships, and for a time with every prospect of success; but presently even these ships were hard aground, and the whole British fleet which had been intended to carry the army across the lake was stuck fast in the mud near the entrance, and thirty miles from the point at which the landing was to be made.

The British commander was at his wits' end. It was clear that the ships could not cross the lake, and the only thing to be done was to transport the army across little by little in the ships' boats, and make a landing in that way. But to do that while Lieutenant Jones and his gun-boats were afloat was manifestly impossible. If it had been attempted, the little gun-boats, which could sail anywhere on the lake, would have destroyed the British army by boat-loads.

There was nothing to be done until the saucy little fleet was out of the way, and to put it out of the way was not easy.

Lieutenant Jones was an officer very much given to hard fighting, and in this case the British saw that they must fight him at a disadvantage. As they could not get to him in their ships, they must make an attack in open boats, which, of course, was a very dangerous thing to do, as the American gun-boats were armed with cannon.

The British commander wanted his bravest men for such work, and so he called for volunteers to man the boats. A thousand gallant fellows offered themselves, and were placed in fifty boats, under command of Captain Lockyer. Each boat was armed with a carronade—a kind of[Pg 808] small cannon—but the men well knew that the real fighting was not to be done with carronades. The only hope of success lay in a sudden, determined attack. The only way to capture the American gun-boats was to row up to them in the face of their fire, climb over their sides, and take them by force in a hand-to-hand fight.

When the flotilla set sail, on the 14th of December, Lieutenant Jones knew what their mode of attack would be quite as well as Captain Lockyer did. If he let them attack him in the open lake he knew very well that the British could overpower him and capture his fleet; but he did not intend to be attacked in the open lake if he could help it. His plan was to sail slowly, keeping just out of reach of the row-boats, and gradually draw them to the mouth of the strait which leads into Lake Pontchartrain. At that point there was a well-armed fort, and if he could anchor his gun-boats across the narrow channel, he believed he could destroy the British flotilla with the aid of the fort, and thus beat off the expedition from New Orleans.

Unluckily while the fleet was yet far from the mouth of the strait the wind failed entirely, and the gun-boats were helpless. They could not sail without wind, and they must receive the attack right where they were.

At daylight on the morning of December 15, the British flotilla was about nine miles away, but was rapidly drawing nearer, the boats being propelled by oars. Lieutenant Jones called the commanders of his gun-boats together, gave them instructions, and informed them of his purpose to make as obstinate a fight as possible. His case was hopeless; his fleet would be captured, but by fighting obstinately he could at least gain time for General Jackson at New Orleans, and time was greatly needed there.

Meanwhile the British boats, carrying a thousand men, all hardened to desperate fighting, approached and anchored just out of gunshot. Captain Lockyer wished his men to go into action in the best condition, and therefore he came to anchor to rest the oarsmen, and to give the men time for breakfast.

At half past ten o'clock the British weighed anchor, and, forming in line, began the advance. As soon as they came within range the American gun-boats opened fire, but with little effect at first. Of course the British could not reply at such a distance, but being under fire, their chief need was to go forward as fast and come to close quarters as quickly as possible. The sailors bent to their oars, and the boats flew over the water. Soon the men at the bows began to fire the carronades in reply to the American cannon. Then, as the boats drew nearer, small-arms came into use, and the battle grew fiercer with every moment. The British boats were with difficulty kept in line, and their advance grew slower. Oarsmen were killed, and time was lost in putting others into their places. Still the line was preserved, and the battle went on, the attacking boats still slowly and steadily advancing.

BOARDING THE GUN-BOATS.

BOARDING THE GUN-BOATS.

Two of the American gun-boats had drifted out of place, and were considerably in advance of the rest. Seeing this, Captain Lockyer ordered the men commanding the boats to surround them, and a few minutes later the British were climbing over the sides of these vessels.

Their attack was stoutly resisted. The American sailors above them fired volleys into their faces, and beat them back with handspikes. Scores of the British fell back into the water, dead or wounded, while their comrades pressed forward to fill their places. There were so many of them that in spite of all the Americans could do to beat them off they swarmed over the gunwales and gained the decks. Their work was not yet done, however. The Americans fiercely contested every inch of their advance, and the two parties hewed each other down with cutlasses, the Americans being slowly beaten back by superior numbers, but still obstinately fighting until they could fight no more.

One by one all the gun-boats were taken in this way, Lieutenant Jones's vessel holding out longest, and the Lieutenant himself fighting till he was stricken down with a severe wound.

Having thus cleared Lake Borgne, the British were free to begin the work of landing. It was a terrible undertaking, however—scarcely less so than the fight itself. The whole army had to be carried thirty miles in open boats and landed in a swamp. The men were drenched with rain, and a frost coming on, their clothes were frozen on their bodies. There was no fuel to be had on the island where they made their first landing, and to their sufferings from cold was added severe suffering from hunger before supplies of food could be brought to them. Some of the sailors who were engaged in rowing the boats were kept at work for four days and nights without relief.

The landing was secured, however, and the British cared little for the sufferings it had cost them. They believed then that they had little more to do except to march twelve miles and take possession of the city, with its one hundred and fifty thousand bales of cotton and its ten thousand hogsheads of sugar. How it came about that they were disappointed I shall hope to tell you next time.

"I WANT SOMEBODY TO PLAY WITH."

"I WANT SOMEBODY TO PLAY WITH."

"Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah! Bimb! bang! boom!" and as they shouted out the school cheer, a group of Vilney boys flung up their caps and danced about to catch them again in a fashion that showed they felt much too jolly to keep them decorously on their heads.

It was the first Friday after the fall opening of the High School, and the cause of the cheering was the fact that the next day was the date of the Boys' Olympic Games at the Fair Grounds. The entertainment was quite a novel one, as none but school-boys were allowed to take part, and the prizes offered were pocket-knives, archery sets, tennis outfits, and last, but by no means least, an elegant full-nickel bicycle of the finest make. Cups, silver services, gold medals, and embroidered banners were all cast into the shade by the latter magnificent inducement, to be presented to the winner of the three-mile bicycle race.

The games had been organized and the prizes provided by a wealthy young bachelor who had lately come to reside in the town, and who was exceedingly fond of boys. Nearly every member of the Vilney High School was entered for one or more of the contests, and Olympic Games had been the absorbing topic of conversation for weeks.

One especially interested was Alec Barsbey. He was the son of a farmer who seemed never to make more than enough to support his family, minus luxuries, which perhaps may be accounted for by the fact that he ought not to have been a farmer at all, but a lawyer or minister, for he was so extremely fond of books. Alec inherited his father's taste for learning—a taste which Mr. Barsbey resolved should be cultivated by the best schooling, to be followed by a college course. He was now in his fifteenth year, nearly ready to enter upon the latter, but the severe study had begun to tell upon his health, when he luckily conceived a strong and sudden fondness for bicycling (for as a rule he did not care for sports or games), and on his friend Murray Hart's machine took now and then an invigorating "spin."

Murray lived just across the road from the Barsbeys, and when the rage for "wheels" broke out in town, he was among the first to own one. However, being also the happy possessor of a pony, he divided his time out-of-doors between the two, and as he was a fast friend of Alec's, he was only too happy when he could prevail upon the latter to accept the loan of his machine.

But if the Barsbeys were poor in purse, they were wealthy in a spirit of independence, and it was only after repeated urgings on the part of Murray that Alec could be induced to ride another's property. Yet even with the limited amount of practice he allowed himself, he speedily became an expert "'cyclist," although this fact was not an unmixed pleasure to him, as it only increased his desire to have a machine of his own, which in the present state of the Barsbey finances was quite out of the question.

Now, however, the Olympic Games presented a possible means of obtaining a splendid one, and Alec made haste to hire at the "bi" head-quarters a trusty wheel on which to practice and ride the race.

But while we have been making this lengthy explanation, Friday has passed, and Saturday morning dawned cool and clear.

What a babble of boys' tongues there was in the dressing-room under the grand stand, and what a crush of boys, girls, fathers, mothers, and cousins on top of it!

Mr. Lancewood, the young bachelor, who was as jolly as he was generous, bustled about from performers to public, boys to girls, grown people to children, until everybody began to believe there must be two of him.

Suddenly he stopped, looked at his watch, and then waved his handkerchief. Instantly a clear-toned trumpet proclaimed the opening of the games, and a brass band rattled off a lively air, at the close of which ten boys in flannel shirts and polo caps walked out from the dressing-rooms and toed the mark for the hundred-yard dash. Mr. Lancewood took his station behind them, pistol in hand, while at the other end of the course two young men held a broad reel ribbon between them to indicate the goal.

"One, two, three! Are you ready? [Bang.] Go!" and off shot the ten as if from the pistol itself.

The spectators sprang to their feet in the excitement. But it only lasts an instant; for Charley Brown has distanced Jack Merks by a pace or two, and now comes panting back, with the ribbon streaming from his shoulders.

Then follows the sack race, in which Ed Primstone falls and rolls two steps for every one he attempts to walk, to the irrepressible mirth of all the small boys, and the consternation of his mother.

Next came the potato race, in which each boy was provided with a basket and a row of potatoes, the latter being placed about three feet apart, all the rows of course being of equal length. The task consisted in trying who could first transfer a row of potatoes from the ground to the basket.

But we have not time to further describe this nor the succeeding three-legged race, in which the right and left legs of two boys were tied together, and their arms placed around one another's necks, the object being to run faster than other pairs similarly fettered. We must hasten on to the grand feature of the programme, the bicycle race, the riders in which presently made their appearance on the track trundling their machines.

There were five entries for the contest—Frank Le Grand, Harry Clare, Dick Summers, Murray Hart, and Alec Barsbey. The latter is pale but determined-looking, and there is that in the ease with which he slides into his seat that causes a by-stander to remark, "That slim young fellow in the blue shirt doesn't make much show, but he has the look of both speed and endurance."

The start was to be from the saddle, and the distance twenty-one times around the track, which latter was simply marked out with lime, as a barrier offering any resistance was apt to prove dangerous.

Quickly and quietly the five lads range themselves in line, with the help of their friends, and when the word is given, off they glide, all abreast, on their smooth-running steeds. Very soon, however, Harry Clare shoots ahead, and a great shout goes up from the spectators as he keeps the lead for the remainder of the first lap.

But sharp eyes can see that he is overexerting himself too early in the race, and now the applause of the multitude inspires him to an additional spurt, which so exhausts him that he is soon obliged to materially slacken his speed.

Alec and Murray Hart keep together for round after round, and it is evident that both are saving themselves for the finish.

Frank Le Grand comes next, not far behind; but poor Dick Summers is soon dropped "out of sight," so to speak, and before making the tenth lap he rides outside the line, dismounts, and resting his elbow on the saddle, good-naturedly turns his attention to cheering on the others.

By this time Alec has left Murray, and is rapidly gaining on Clare, who now reaps the fruits of his over-enthusiasm at the start. He loses inch after inch of his lead, until finally Alec dashes past him amid the wild cheers of the spectators and a special burst of brass from the band.

Harry, however, has no intention of giving up so easily; for after his friends have provided him with a match or two to chew on, he appears to feel re-inspired, and rolls around the track with old-time swiftness.

And now the excitement begins in earnest. Frank Le Grand having followed Dick's example, there are only three competitors left; and as Murray seems to be taking things pretty comfortably, all eyes are centred on Alec and Harry. The former is exerting every nerve, resolved[Pg 811] not to take second place again, while Clare seems as determined that he shall.

Around and around they fly, their noiseless movements lending an additional interest to the race. They look neither to the right nor left, except that Alec, every time he approaches a certain spot opposite the grand stand, gives a single glance toward one corner of it.

"Keep it up, Harry!"

"Go it, Alec!"

"Catch 'em, Murray!"

These and other cries, sent forth with the full power of youthful lungs, urge their subjects on to victory, and presently keen observers can trace a gradual widening of the breach between Barsbey and his pursuer. Both boys are working terribly hard, and an on-looker not accustomed to such contests, and ignorant of the careful training that is supposed to precede them, might expect to see one or both lads fall in their tracks.

Suddenly Alec gives an extra spurt, and an instant later reaches the point where he is in the habit of throwing his strange glance toward the grand stand. True to his custom, he raises his eyes, and at once a troubled expression overspreads his face. Then, instead of continuing on for his triumphant eighteenth lap, to the amazement of all he steers into the centre field and quickly dismounts. He leaves his machine lying on the grass, runs back across the track, and disappears among the crowd on the stand.

What can it mean? He has certainly not given out, or he could not have moved about so easily. A number of the boys, in their curiosity, hurry over to examine Alec's machine, but a warning shout from Murray turns the general attention back to the race between the only two now remaining in it.

Harry seems to be completely exhausted, while Hart, who is only half a lap behind now, appears to be almost as fresh as at the start. Harry makes a feeble final effort, and thus causes the race, amid the wildest excitement, to result in a tie.

What was to be done? The bicycle could not be presented to both, nor could the race be repeated later on, as the games were now over.

In the midst of the discussion Murray disappeared, for he was anxious to find out what had happened to Alec. Somebody had seen him leave the grounds; so, tired as he was, Hart mounted his machine and posted off to the Barsbeys'. He met Alec at the gate, just coming out.

"Who won?" was the latter's first question; but Murray did not answer it.

"Tell me, Alec Barsbey," he exclaimed, "why on earth you dropped out of that race?"

The other colored, glanced back toward the house, and then linking arms with his friend, drew him out toward the orchard as he replied: "I'll tell you, Murray, but don't look so fierce about it. You know how nervous mother is? Well, I told her she'd better not come to the games if she thought she'd worry about me; but she declared she'd worry worse if she didn't keep me in sight. She's never very well, and any overexcitement may bring on one of her bad turns. At first I didn't know what to do about it. I hated to give up the race, although I knew that was the safest plan, and at the same time didn't want to run the risk of frightening mother into another sick spell. Then I thought of a way to fix matters, which was to have mother go with father, and take a seat near the entrance where I could see her every time I came around. She was to carry in her pocket a green silk handkerchief, which I believe once belonged to some Irish ancestor of the family, and when she found the excitement was becoming too much for her nerves she was to wave it, and I would stop at once—which I did, as you saw, and just in time, too, for she hated to give the sign, and had nearly fainted. Father and I helped her out, brought her home, and now she's all right. Of course I'm no end sorry to have missed the finish, but then it would have been dreadful to have gone on and let mother suffer. And now tell me who's won the machine."

"You have," cried Murray; "and if you'll go up to your room and rest, and promise not to stir out of it until I come back in about fifteen minutes, I'll have it brought over and duly presented."

"But why can't I go—" began Alec.

"Hush! not a word!" returned his friend, authoritatively. "Imagine your mother's feelings if you should go near those grounds again to-day! Now go in and tell her the good news, with my compliments."

"But I don't see how I could have won, when—" but Murray was already speeding off on his "wheel," and Alec could do nothing else than wait patiently for him to come back.

When Mr. Lancewood heard the story of the green silk handkerchief he hailed it as the best solution possible of the difficulty caused by the tie to announce Alexander Barsbey as winner of the bicycle.

Harry Clare declared that no way of settling the matter could have pleased him better, while as for Murray, he hurried back to the Barsbeys' so eagerly that he took two "headers" in one block.

Of course the machine itself could not be presented until the size of the winner was known. Murray had forgotten this fact when he promised Alec to return with the prize, but the precious slip of paper Mr. Lancewood had given him to deliver answered every purpose.

The bicycle, which was truly a beauty, arrived early the next week, and all Vilney affirms that it was most bravely won.

Last year hundreds of persons obtained from the Superintendent of Central Park, in New York, special permits to gather autumn leaves, from the ground only, in any part of the Park. These leaves, when dried, are used by artists and designers as types of nature's beautiful forms and color-work, also by botanists and wax-flower workers, and for home decoration, or are disposed of to city florists, at so much per hundred leaves, to be worked up in various floral designs. Thousands of "American Autumn Leaves" are sent every year to Europe, where they are highly prized.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

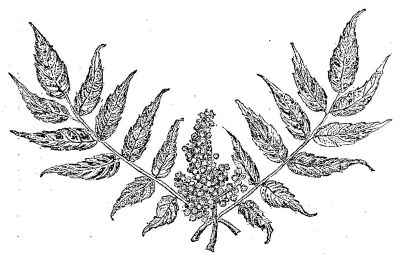

Among some of the best varieties of leaves as regards color, form, and durability are those of the maples, sweet gum, sumac, dogwood, Virginia creeper, and crane's-bill geranium. The popular idea that an early frost is needed to insure the brilliancy and perfection of autumn foliage is a mistake. A lingering and moist fall is all that is required to produce the most brilliant colors.

When gathering leaves, always select those that are fully matured, and are leathery and fibrous. It is always best to secure them in small bunches, each bunch to contain several leaves attached to a small twig. Be careful also not to have the twig so long or thick that it will interfere with the pressing. I have found a small and light box with a close-fitting cover very useful when collecting leaves. A layer of damp (not wet) moss or grass should be placed on the bottom of the box to keep the air moist, and thus prevent the drying up or wilting of the leaves.

For drying the leaves, old and smooth newspapers, useless books, old sheet music, and old account-books will answer just as well as the most expensive botanical dryers. When arranging the leaves in the dryers, try and place those of the same thickness together, so that there may be a uniform pressure when the weights are applied. I have found a soap-box, filled with stones or other heavy material, and placed on the dryers, one of the best of make-shifts in the way of a well-ordered botanical press.

The time required for drying the leaves is governed by the amount of sap they contain, and the dryness of the atmosphere. Never attempt what is known as "hot-pressing"—that is, pressing with a hot flat-iron—unless you wish to sacrifice the delicate tints of the leaves, and turn to an unpleasant brown the masses of heavy and strong color. I have found by experience that coating the surfaces of the leaves with varnish, bees-wax, and other materials of a waxy nature, is not an advantage. This is particularly true of varnish, which gives to the leaves a glossy and unnatural look, while bees-wax, stearine, and spermaceti cause dust to adhere, which soon disfigures and obscures their beautiful colors.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Some years ago I became acquainted with a large number of children who lived on "our block," and their mothers and their fathers; in fact, I was one of the fathers. As a rule, they were all pleasant young people, and it became a pastime with me to entertain, amuse, and find them something to do, particularly during holidays and on Saturdays. In course of time two large and vacant rooms were secured in one of the houses, and I received a sort of standing commission from the parents of the children to fit up and furnish the two rooms as a play house. The following description will give a pretty fair idea as to how the walls were furnished.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

First a reliable and communicative colored kalsominer was called in to kalsomine the walls of one room in alternate perpendicular bands of a very light blue and a very quiet gray tint, each band or stripe of color being nine inches in width. The other room was papered with a cheap wall-paper which cost about nine cents a roll. This paper was twenty inches wide; the pattern consisted of several styles of imitation chestnut-wood graining. Having on hand a very large quantity of autumn leaves, we set to work disposing of them on the walls of the rooms in the following manner:

First two glue-pots were made, as shown in Fig. 1, from empty fruit cans, the inner or smaller can to contain the glue, and the outer or larger boiling water. To the outer can a wire handle is attached. With the two cans a constant supply of hot glue was always on hand.

To the grained paper the leaves and tendrils of the Virginia creeper were fastened as shown in the right hand part of Fig. 2. The design, which is here horizontal, will of course be upright on the wall. To every other stripe of graining the leaves of the Virginia creeper without the tendrils were fastened, so as to avoid too much sameness. In this room the top bordering consisted of sumac leaves and berries, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

To the blue and gray bands of kalsomine were fastened the brilliant leaves and clusters of the crimson berries of the staghorn sumac, as shown in Fig. 4, and a top bordering of sumac and maple leaves, as shown in Fig. 5.

The leaves were used in a bold and vigorous manner; all fine and close work was avoided, as it would be lost, and the general effect spoiled. For the amount of time expended and the labor and trouble this work cost, we felt well repaid, and every one decided that the result was a great success, and that we had certainly discovered a novel and beautiful use for autumn leaves.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Some mice in council met one night,

And vowed by this and that

That they would arm themselves for fight,

And brave the tyrant cat.

Said they: "Why longer fear her power?

'Tis time our strength to try.

We'll hang her by the neck this hour,

Or in the effort die!"

Two pistols and a carving-knife,

A rifle and a rope,

Were instruments of war enough

To justify their hope.

So with the Captain in the front,

The hangman in the rear,

They started out to search for puss

Without a thought of fear.

Through silent halls and broken walls

With cautious step and slow,

And furtive glances right and left,

From room to room they go.

Now pausing by a nook or sill,

Where trouble might be found,

Now crowding close and closer still

At every trifling sound.

But when before an open door

The cat appeared in sight,

The very instruments they bore

Seemed paralyzed with fright.

The Captain shrinking in the van,

The hangman crouched behind,

The pistol-shot and rifleman

Had but a single mind.

In doubt and dread they turned and fled,

And lucky mice were they

To find a hole so large that all

At once could run away.

New York City.

Dear Readers of the Post-office Box,—I have a story to tell you which will certainly please all those who have cute little kittens to pet and play with. I hope, too, it will put into some of your hearts a sweet thought of imitating the children I am going to write about. I think I will call the story

PUSSY'S CONTRIBUTION.

"That ends it; not another one will I make! Bother! just to break off when I wanted it! Well, I don't care."

The speaker was a boy about fourteen, sitting in a scantily furnished room, busily cutting sticks by the light of a small lamp, and surrounded by a plentiful supply of chips. On a bed in one corner was a little girl some four years younger, the last of a family who had moved out West, father, mother, and some older children having died, leaving only these two. The little girl had been for some years a cripple with spinal trouble, and the boy the worker and care-taker.

Very pale looked the little face, and sad the voice sounded that called just then,

"Andrew, can you come here a minute?"

"Yes, Jessie. What's the matter?"

As he sat down on the bed she took his hand, saying:

"What was it broke? Your knife? I was afraid that was it. What will you do?"

"Do? Nothing, except give you a nice blaze with those old sticks. You don't often have one."

"And give up the Cot? Oh, Andrew!" and her dark eyes spoke the disappointment even more than her voice.

"Well," said Andrew, a little upset by her distress, "what's the use? My knife's broken; I can't pay to have it mended, nor buy another, and even if I wanted to, I don't know where I could borrow one, and then, when I get my sticks all made, it will be only a dollar, which great sum won't go far to help buy the Cot that the paper wants. Besides, after all, it will really be Mrs. Fuller's money, for I know she could get them made cheaper at the carpenter's. I heard her say to her daughter the day she gave me the order, 'Nellie, as Andrew is wishing to make some money to give to Young People's Cot, I will let him make the flower sticks for me instead of giving them to Mr. Dawson, and he will have that to give—ten dozen, at ten cents a dozen.' I suppose you told Miss Nellie what I was wishing for?"

"Yes, after she brought the paper asking for the money for the Cot. Don't you remember, you read it to me, and how we were wishing we could make some money to give? I think it is very kind of Mrs. Fuller to think of you."

"Well, at first I thought so too; but to-night, as I sat working at the sticks, I felt as she was somehow giving it to me, and just taking the sticks to make believe I was working for the money, and it made me feel angry. Then I have only six dozen finished, and it is tiresome, after working hard all day, to spend the evening working too, and I don't believe it worth all the trouble, just for one dollar."

Throwing himself on the bed, he looked as if he considered the matter settled.

Not so Jessie, the little comforter.

"Why, Andrew, Miss Nellie said the other day, when she was here, how fast you had worked, and how nicely the sticks looked tied up in bundles, and I should not wonder if she could mend your knife. I think she can do almost anything."

"Why, Jessie," said Andrew, laughing merrily, "she couldn't do that. Girls can't mend knives."

"Miss Nellie is not a girl, Andrew. You should not speak so of her."

"Well, she's a young lady, and that's pretty much the same. They can't do much."

"Oh, Andrew, how can you speak so?" said Jessie, indignantly. "I should like to know who it was persuaded Mr. Fuller to give you the place in his office, and often gives you shoes and clothes, but Miss Nellie, and who lent us money to help pay the rent the time you were sick, and comes to see me so often, bringing books, papers, and many things, but a young lady, even Miss Nellie. You ought to be ashamed of yourself." And the voice which began so strongly to fight Miss Nellie's battle ended in a sob.

In a moment Andrew, who was really a kind-hearted, manly boy, only just now tired and disappointed, had his arm around the little girl.

"There, don't cry, Jessie; you know I didn't mean anything. I know Miss Nellie is very good to us. I don't know what we would do without her, only I'm sure she couldn't mend a knife," boy-like, not willing to give up his opinion.

"Well, Andrew, I don't know about that, only I wish I could be just such a young lady as she is, and I'm sorry I spoke so cross, and just when we were trying to work for the good of others; that's a poor way to copy Miss Nellie."

"Meow, meow," now sounded in very decided tones from somewhere below the quilt.

"Oh, Andrew, I forgot kitty," said Jessie, pulling out from under the covers a very pretty little Maltese kitten, with a blue ribbon on its neck, the latter a present from the famous Miss Nellie!

The kitten had strayed into the room some weeks before, and staid with Jessie ever since then, a much-loved companion to the lonely little girl. At present she had been occupying her usual abode under the covers near Jessie, and in the making up of the children had rather suffered from close quarters. When pussy had been made comfortable again, Jessie said:

"Andrew, I want to tell you a secret. Put your head down on the pillow by me, but don't hurt Twilight"—the name Jessie had chosen for her cat because of its color and its coming to her at that time of day. "I was talking to Miss Nellie the day she was speaking of the Cot, and wished I could do something for it, but could not, as I was not able to work. She said perhaps I could find something to give up that would bring some money, something to bear instead of do, and said she would try and think, and so must I. Well, she had not been gone more than an hour when there was a knock on the door, and in came a lovely-looking little girl about my age, holding Twilight in her arms, and saying, 'Is this your kitty? Will you sell her to me? I'll give you a dollar for her. I just want a little cat, and saw this one as I passed, and came in to see if you would let me have her. My name is Helen Lathrop, and I live in that big house on the hill that you see from here.' 'Sell my kitty!' I said; catching her rather roughly, I am afraid, out of her hands, 'no, indeed, not for any money,' and at once I put Twilight under the covers for fear she might take her away. 'I think you might,' she said; 'I will take such good care of her—better than you can here,' looking round the room. Then turning to me, she said, 'Why don't you get up, and not lie in bed this time of day; it is 'most three o'clock?' When I told her I was sick, and could not get up, she seemed very sorry, and said she would not ask any more for kitty, only if I ever wanted to sell her, she would buy her, and went away. When she was gone I gave Twilight a scolding for being out, and then had a good cry to think how near I came to losing kitty, and was so startled with my strange visitor. After I got quiet I lay looking at the house on the hill, and telling kitty all my trouble, but she seemed quite happy, and would shut her eyes and then open them partly, just, I think, to let me know she was listening, and finally went to sleep, but I could not, I felt so upset. While I lay looking at the house suddenly a thought seemed to jump into my mind: 'You were wishing to make some money for the Cot. Here is a chance—sell Twilight.'"

"Oh, Jessie, you wouldn't, would you?" for besides Jessie's pleasure, Andrew had a soft little corner in his own heart for kitty.

"Wait, Andrew, until I tell you. I said nothing to you, and Miss Nellie did not come for a few days, so I just thought and talked to Twilight. At first it seemed so hard I told her I would never let her go, and then I would think of all Miss Nellie told me of the poor little sick children in New York so much worse off than I am—you know, she used to live there—and how comfortable they were made at St. Mary's Hospital. So I thought and thought in the daytime, and dreamed about it at night, until Miss Nellie came, and we had a long talk about it, and Miss Nellie said she thought it would be a great deal for me to do, and told me the story of the widow's mite, and said it would be something like that, though I couldn't see exactly why, as I don't think kitty a mite, but a great deal, so I made up my mind, and kitty must go. I couldn't help crying over her some, Andrew. You know I shall miss her so! And I think Miss Nellie was sorry to lose her too, for I saw tears in her eyes as she kissed me good-by, and she is going to write a note to Helen Lathrop, and tell her she can buy dear Twilight."

"Jessie, you must not give puss away. How can you get along without her? she is all you have to love," said Andrew, taking one of the little dark paws lying out of the covers and rubbing it softly. Puss blinked her eyes, as much as to say she knew very well how important she was.

"Oh, Andrew, don't say that. You know, first, I have Jesus, who loves and takes care of me, and helps me bear my pain," said Jessie, reverently; "and dear Miss Nellie, who taught me to love Him and all that is good; and then this dear boy, who is always so kind and loving to me—I can't sell you at any price," putting her thin little hand lovingly on his face, the fear of hurting kitty preventing a kiss; "and even Mrs. O'Brian upstairs, when she comes to 'cheer me up like,' as she says, 'with a wee bit of a story,' although she 'most always tells such queer ones, I feel frightened when she goes away. And then, Andrew, you know Twilight will be so much better off—I suppose live on cream and sleep on a silk cushion. And you know sometimes when you are away she gets into trouble, and I can't help her, like the day the cross boy threw stones at her. So, Andrew, won't you finish your sticks? and then we can send two dollars to the Cot."

"Well, Jessie, I rather guess I will, indeed, and perhaps I can grind my knife enough to use. I will run over now to Mr. Hammond, who is still working, and see," said Andrew, getting up; and I think, if the light had been stronger, Jessie would have thought Andrew sorry to lose kitty too, for there were a good many tears in his eyes. And as he went out he thought to himself: "Well, I ought to feel ashamed. Here is Jessie, only a girl, as I often say, and a sick one at that, setting me such an example of unselfishness. Dear little thing, I don't wonder Miss Nellie loves her so."

In one acknowledgment of the Cot in Harper's Young People appeared the following: "Twilight, $1, Andrew Thornton, $1, Seneca, Kansas."

Aunt Edna.

La Grange, Illinois.

Perhaps some little readers, less fortunate than I, may like to hear about my pleasant trip this summer to Denver, Colorado. We were forty-two hours in the cars between Chicago and Denver, and I was tired crossing the plains, as there is nothing to see but prairie grass, and it was so dusty, but when we arrived at our destination I was quite delighted. Denver is a fine city, and has some buildings as pretty as those in Chicago, and then the mountains are so near!

We took a trip up Clear Creek Cañon to Idaho Springs, thirty-eight miles through the Rocky Mountains, and the scenery was just awfully grand—mountains above mountains, with lots of gold and silver in them! The air is light and clear, and this mountain refuge stands about eight thousand feet above the sea-level. It was funny to see the hot springs; the water was so warm that I could not hold my hand in it. And then there are ice-cold soda springs; but the water does not taste good, although they say it is wholesome to drink it. I would rather have lake water. We climbed up a good way, and got some nice stones with silver and gold in them.

My papa also took us to the great mining exposition, and, oh, my! it would have done your readers good to see the great chunks of gold ore. One big piece was valued at twenty-seven thousand dollars. And then there were so many pretty stones and metals—gold, silver, galena, copper, iron, lead, zinc, tin, soda, salt, granite, marble, and coal. It is built of stone, and is outside of the city. You get there by the steam-cars for ten cents. It is a permanent structure, and will be in better order next year.

It would take too much space to tell all we saw, but I would urge on all who can to take a trip to Colorado. We intend going next year again, and until then adieu.

Eliza B. S.

Lockland, Ohio.

I have taken your paper only a short time, beginning August 15. I have two kitties—one Snip, and the other Tabbie. I have some chickens. I think a good deal of one I call Bess. She knows her name, and will come to me when I call her. I have a little curly-headed brother, who is the sunshine of the whole house. I have a swing, and Albert, the little darling, likes to swing. I have to hold him in my lap. He is two and a half and I am thirteen years, and we are the only children. I want to take music lessons, but we have no piano. Papa does not know I am writing this letter, and it will please him very much to see it in print. Mamma always looks over my letters, so of course she knows this is the first letter I have ever written to you.

Grace M. S.

If I were you, I would learn to read music, and then when you have a piano, as I hope you will some day, you will be all ready to begin your study in earnest.

New York City.