The Project Gutenberg EBook of The South American Tour, by Annie S. Peck This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The South American Tour Author: Annie S. Peck Release Date: June 9, 2019 [EBook #59715] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SOUTH AMERICAN TOUR *** Produced by Donald Cummings, Adrian Mastronardi, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

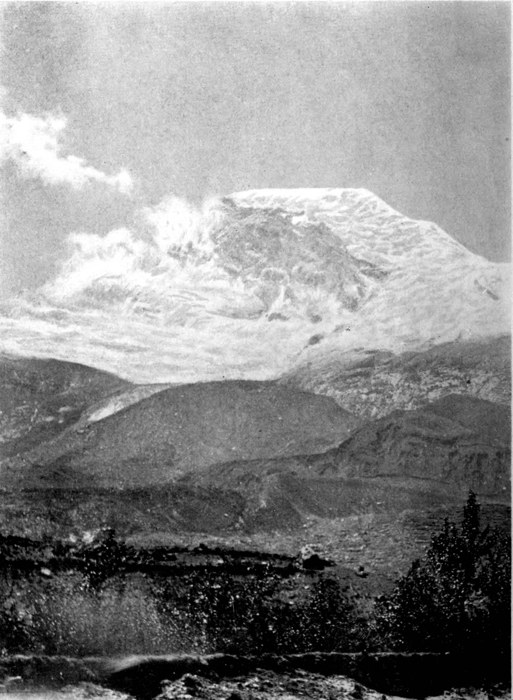

NORTH PEAK OF MT. HUASCARÁN, 21,812 FT.

THIS PEAK, ASCENDED BY MISS PECK, SEPTEMBER 2, 1908, IS 1,500

FEET HIGHER THAN MT. McKINLEY.

I congratulate Miss Annie S. Peck, the publisher of this book, and those who consult or read it, upon the preparation of a work of this character. Interest in Latin America is now so rapidly growing throughout all the world, and especially in the United States, that a descriptive guide-book of this kind regarding the regions commonly visited by tourists has become an actual need; such a work by Miss Peck is a practical and timely contribution to the literature of the day. There are few persons better qualified to write a book of this character. The remarkable explorations which Miss Peck has undertaken in the most difficult sections of Latin America, and the traveling she has done in all parts of it, not only have provided her with a vast fund of useful information about the countries of South America but give especial authority to what she writes. Her book contains in compact form an amount of definite information concerning the countries considered, which should place it in the forefront of works of this character.

While, of course, it is impossible for the Pan American Union, as an official organization, and myself, as its official head, to endorse in any way a particular book or accept responsibility for the statements and views it contains, it gives me real pleasure, from a personal standpoint, to express the hope that this work of Miss Peck will have a wide circulation and prove of decided help in promoting travel to and through the Latin American countries.

The Pan American Union, which, as readers of this book probably know, is the office of all the American republics—the United States and its twenty sister Latin American countries—organized and maintained by them for the purpose of developing commerce, friendship, better acquaintance, and peace among them all, is doing everything possible and legitimate to persuade the traveling public of the United States and Europe to visit the Latin American countries and become familiar with their progress and development. There is no viinfluence in the world that helps more to advance friendship, comity, and commerce among countries than travel back and forth of their representative men and women. Nearly every person who visits Latin America under the advice of the Pan American Union, upon his or her return, writes a letter expressing appreciation that this opportunity has been afforded of seeing these wonderful countries of the south.

In conclusion, I would observe that if those who may become interested in Latin America through reading Miss Peck’s book desire further information about any or all of these republics, the Pan American Union will always be glad to provide them with such data as it may have for distribution.

Washington, D.C., U.S.A., October, 21, 1913.

To all Americans both of the Northland and of the South this book with due modesty is inscribed, in the hope that by inciting to travel and acquaintance it may promote commercial intercourse, with the resulting ties of mutual benefit and respect: in the hope, too, that the slender cord now feebly entwining the various Republics may soon draw them all into more intimate relations of friendship; at last into a harmonious Sisterhood, in which neither age nor size shall confer superior rights, but mutual confidence based upon the foundations of justice shall insure perpetual peace.

The opportunity is here improved to express my grateful acknowledgment of kindly assistance and attentions of diverse character, received throughout my travels from many of my own countrymen, from Englishmen invariably interested and ready to aid, and from the ever courteous and helpful Latin Americans: officials and private individuals, with members of my own sex. As a complete list of these would be too long I permit myself the mention of those only who are entitled to especial recognition, our Minister to Bolivia, 1910-1913, the Honorable Horace G. Knowles, and the Governments of Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, without whose prompt and substantial aid this work would have been impossible. That its usefulness may be such as to convey to them a valid return is my earnest aspiration.

The indulgence of critics and of tourists is sought for errors (few, I trust) and deficiencies which may be discovered. These and other faults will have crept in on account of a preparation somewhat hurried that the book might earlier be of service, and from the impossibility of securing on some points exact and adequate information, in spite of diligent investigation and careful scrutiny of facts and figures.

Many items of interest and importance have been omitted lest the book should be too long. The selection of material it viiiis hoped will be suitable to the general reader, though doubtless every one will find topics presented to which he is indifferent and others neglected which appear to him of greater consequence.

Hours have been spent in searching for the best authority as to widely different figures and even as to varying accents and spelling. In the absence of other information a few statements have with some trepidation been copied from authors whose recognized blunders have made their unverified observations appear questionable.

While a different statement made by some other, albeit notable writer cannot be taken as conclusive evidence of error, any just criticism or suggestion presented to the author will be gratefully received and considered with a view to incorporating it in a subsequent edition.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | What the Tour Is—How and When to Go—What It Costs | 1 |

| II | The Voyage to Panama | 6 |

| III | The Isthmus—The Canal—Colon | 12 |

| IV | Colon to Panama—Panama City | 23 |

| V | Steamship Lines on the West Coast—Ecuador | 36 |

| VI | On the Way to Callao | 43 |

| VII | Salaverry, Chan Chan, Chimbote, the Huailas Valley | 50 |

| VIII | Callao to Lima—History | 59 |

| IX | Lima, the City of the Kings | 66 |

| X | The Suburbs of Lima—The Oroya Railway—Cerro de Pasco | 86 |

| XI | The Southern Railway of Peru, Arequipa | 99 |

| XII | The Southern Railway—Cuzco | 109 |

| XIII | Bolivia—Cuzco to La Paz | 123 |

| XIV | The City of La Paz | 133 |

| XV | Other Regions of Bolivia and Routes to the Sea | 142 |

| XVI | Along the Chilian Coast, Arica to Valparaiso | 154 |

| XVII | Valparaiso | 163 |

| XVIII | Santiago | 170 |

| XIX | Santiago—Continued | 179 |

| XX | Southern Chile—Santiago to Buenos Aires by Sea | 191 |

| XXI | Across the Andes to Mendoza | 198 |

| XXII | Argentina—Across the Plains to Buenos Aires | 213 |

| XXIII | Buenos Aires | 222 |

| XXIV | Buenos Aires—Continued | 238 |

| XXV | A Side Trip to Iguassu Falls and to Paraguay, including Important Argentine Cities | 257 |

| xXXVI | Uruguay | 272 |

| XXVII | Brazil—Along the Coast to Santos | 286 |

| XXVIII | Santos and São Paulo | 295 |

| XXIX | Rio de Janeiro—Bay and City | 306 |

| XXX | Rio de Janeiro—Continued | 321 |

| XXXI | Rio de Janeiro—Concluded | 330 |

| XXXII | Northern Brazil—Homeward | 341 |

| XXXIII | South American Trade | 360 |

| Index | 391 |

| PAGE | |

| North Peak of Mt. Huascarán, 21,812 Feet | Frontispiece |

| Mt. Huascarán from an Altitude of 10,000 Feet | 56 |

| Llanganuco Gorge | 56 |

| Callao Harbor; receiving Secretary Root | 66 |

| Plaza de Armas, Cathedral | 66 |

| Portales and Municipal Building | 70 |

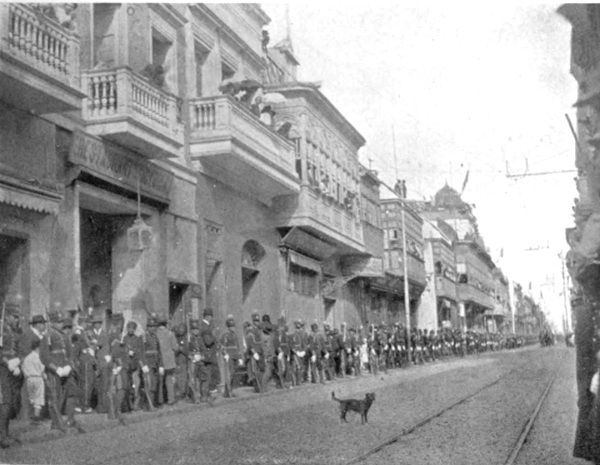

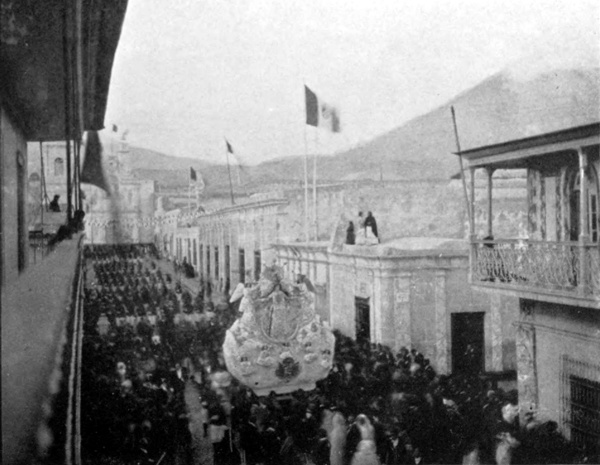

| Calle Junín, Inauguration of President Leguia | 70 |

| Paseo Colón and Exposition Palace | 78 |

| In the Museum, Exposition Palace | 78 |

| Statue of Bolívar, Plaza de la Inquisición | 82 |

| Peruvian Mummy, University of San Marcos | 82 |

| On the Oroya Railway | 94 |

| Plaza, Cerro de Pasco | 96 |

| Near the Source of the Amazon (Marañon) | 96 |

| On the Southern Railway of Peru | 102 |

| Religious Procession, El Misti at the Right | 102 |

| Cathedral, Plaza Matríz | 116 |

| Ancient Wall | 116 |

| Balsas, Lake Titicaca | 128 |

| La Paz from the Hills | 128 |

| Cathedral and Government Palace | 134 |

| Hall of Congress, Monument to Murillo | 134 |

| Street Near the Market | 138 |

| In the Cemetery of La Paz | 138 |

| Monolithic Gateway, Tiahuanaco | 142 |

| Indians at Festival, Tiahuanaco | 142 |

| Mt. Illampu, 21,750 Feet, from the Plateau, 13,000 Feet | 146 |

| Sorata Town | 146 |

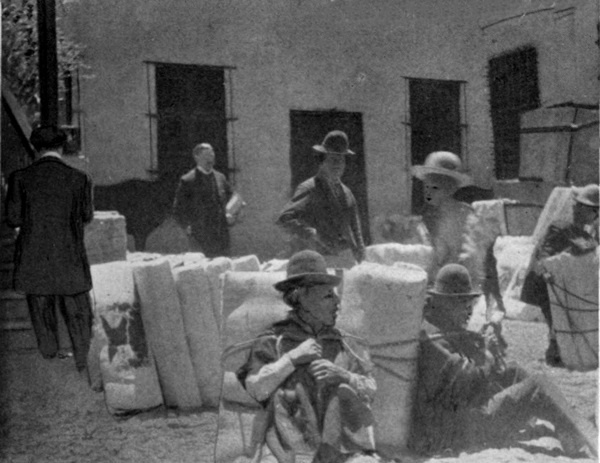

| Indians Transporting Freight | 150 |

| Plaza and Government Palace, Oruro | 150 |

| Valparaiso Harbor | 164 |

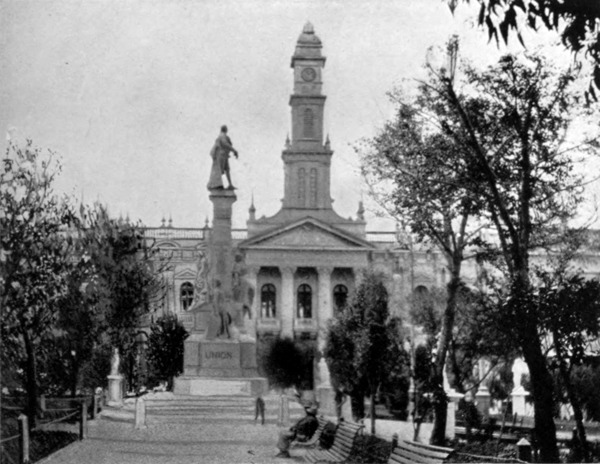

| xiiMonument to Arturo Prat, Plaza Independencia | 164 |

| Avenida Brazil, with British Monument | 168 |

| Residence, Viña del Mar | 168 |

| New Hall of Congress, Library at the Left | 174 |

| Palace of Fine Arts | 180 |

| Entrance to Parque Santa Lucia | 180 |

| Palacio de la Moneda | 186 |

| Cemetery in Rose Time | 186 |

| Tierra del Fuego | 196 |

| Entrance to Andine Tunnel, Chilian Side | 196 |

| Avenida de Mayo | 224 |

| The Capitol Plaza, Buenos Aires | 230 |

| Palermo Park | 230 |

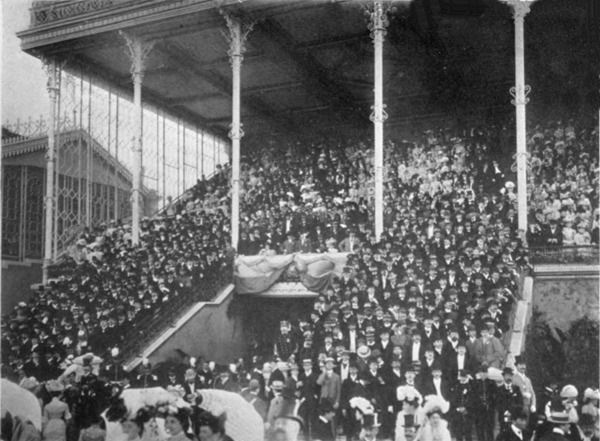

| Jockey Club Stand, Hippodrome | 236 |

| Centennial Exposition, Rural Society | 236 |

| Botanical Garden | 240 |

| Zoological Garden, House of Zebus | 240 |

| Patio in New Hall of Justice | 246 |

| Colón Theatre | 246 |

| Tomb, Recoleta Cemetery | 248 |

| Recoleta Park | 248 |

| Mercado de Frutos and Riachuelo | 250 |

| Building of Public School Sarmiento | 250 |

| Paseo Colón, Grain Elevators in the Distance | 252 |

| Darsena Nord and Marine Shops | 252 |

| On the River Tigre | 254 |

| Legislative Building, La Plata | 254 |

| University Building, La Plata | 256 |

| Museum, La Plata | 256 |

| A Fraction of the Iguassú Falls | 260 |

| Judiciary Building, Rosario | 264 |

| Residence on an Argentine Estancia | 264 |

| Government Palace, Asunción | 268 |

| New Legislative Palace, Montevideo | 276 |

| Solis Theatre | 280 |

| Government Palace | 280 |

| xiiiPort of Santos | 296 |

| Luz Station, São Paulo | 300 |

| Municipal Theatre | 300 |

| Ypiranga Museum | 302 |

| Hotel of Immigrants, São Paulo | 302 |

| Coffee Fazenda | 304 |

| Coffee Tree | 304 |

| Avenida de Rio Branco | 314 |

| Boulevard Beira Mar from Pensão Suissa | 314 |

| National Library | 322 |

| School of Fine Arts | 322 |

| Avenida do Manque | 326 |

| Residence of the President | 332 |

| Botanical Garden | 332 |

| Corcovado from the Boulevard Beira Mar | 336 |

| Through the Clouds, from Corcovado | 336 |

| United States Embassy, Petropolis | 340 |

| Street with River | 340 |

| Praça de Frei Caetano Brandão, Pará | 354 |

| Bahia | 354 |

The South American Tour! “Como no?” “Why not?” as many Spanish Americans say when they wish to give hearty assent. Have you been around the world? Do you travel for pleasure or business? Whatever your object, whether your purse is full or you wish to fill it, the southern half of our hemisphere is a land which should not be ignored.

What is there to see? May the journey be taken in comfort? These things shall be revealed in detail after a few general facts have been presented.

Is the enjoyment of scenery the chief aim of your travel? With ease you may behold some of the finest in the world,—much more if you care to take a little trouble: snow clad mountains galore rising above 20,000 feet, dwarfing the Alps into insignificance, giants to be admired not only from afar as tourists in India gaze upon the Himalayas, but from nearer points, even from their very foot; smoking volcanoes, cliffs more lofty than those of the Yosemite, wonderful lake scenery including the highest sheet of water (12,500 feet) where steamboats ply; strange yet fascinating deserts; wondrous waterfalls, one of these surpassing Niagara in height, volume, and beauty; magnificent tropical vegetation and forests, the highest railroads, the most picturesque and beautiful harbor of the world. All of these, with the exception of the great cataract, are easily accessible, and form a combination of scenic attractions unsurpassed in any portion of the globe.

Do strange people and cities interest you more? You may wander in towns old and quaint, containing buildings of centuries past, and in cities quite up to date growing with the rapidity of our own. In a few places Indians in peculiar garb may be seen by the side of Paris gowns and English masculine attire, in others an Indian with sandals, hood, and poncho would attract as much attention as on Broadway. xviiiSeveral cities have boulevards, parks, and opera houses finer than any of which North America can boast.

Do you care for ruins, antiquities? These also abound. Whole cities of the dead are there, and others where the new civilization rises above or by the side of the old. Temples, palaces, fortifications, ancient statues, mummies, and pottery may be cursorily admired or profoundly studied, and search may still be made for undiscovered monuments of a prehistoric past.

These countries rapidly advancing, with astonishing mineral and agricultural resources awaiting development, with railroads to be laid, with fast growing markets for almost every kind of merchandise, invite the trader and the capitalist to investigate hitherto neglected opportunities before it is too late.

Well informed as to what there is to see, the possible tourist is certain to inquire if the journey will be comfortable. Perhaps, indeed, the order of the questions should be reversed; for few, I greatly fear, would be tempted to say “Let us go!” if the tour involved any hardship. Happily this is not the case. Though the Imperator, the Mauretania, and the Olympic do not yet sail in that direction, the names of several steamship lines which serve the traveler to Panama, or Buenos Aires are a guarantee of comfort and of sufficient luxury. The steamers elsewhere are commodious, having for the most part state rooms provided with electric fans, and satisfying all reasonable requirements. The railroads in the various countries have the usual equipment. The hotels, if one does not depart from the ordinary line of travel, will in general be found satisfactory, providing excellent food, good beds, etc., and in those cities where some little time should be spent meeting the wants of all except the ultra fastidious tourist.

If we do not sympathize with the cry “See America first,” bearing in mind that America is the whole and not a fraction of the Western Continent, at least, when we have seen the Old World, instead of ever retracing our steps in familiar ways, let us seek the strange New World beyond the equator where a brief tour will reveal a multitude of scenes amazing and delightful, even to the experienced traveler.

The South American Tour, rapidly becoming fashionable and popular, and about to be described, includes the most interesting and accessible portions of that continent,—its finest scenery, its greatest cities. A wonderful variety in the swiftly moving pictures prevents any dullness on the part of the intelligent traveler, who is ever kept alert for the continually fresh experiences of this remarkable journey.

Where. My tourist party will be conducted first to Panama, where soon the sail from ocean to ocean through an immense artificial channel will awaken sensations of wonder and pride. The opportunity then to continue in the same vessel along the West Coast of South America, invaluable for commerce and for those on business bent, may prove a disadvantage to the pleasure traveler, by tempting him to pass with a mere glance the City of Panama and other spots worthy of observation.

On the Pacific side Peru, Bolivia, and Chile will be visited by every one: a few may make the side trip to Ecuador,—Guayaquil and Quito. In order to return along the East Coast one may complete the circuit of the continent by sailing down, through the Straits of Magellan, past Punta Arenas, and up on this side, or with the greater number may cross the Andes by rail, thus to reach the metropolis of South America, Buenos Aires. Thence, after, or if not including, an excursion to Paraguay and to the greatest of American waterfalls, the Iguassú, one may sail to Montevideo in Uruguay, 2from there to Brazil, returning from Rio de Janeiro directly to New York, or by way of Europe as preferred. Similarly the trip may be made from Europe by several lines of steamers direct to Panama, or more quickly by way of New York, with a return from Rio.

Altogether omitted from this itinerary are the countries on the northern shore of South America. Of these Colombia and Venezuela are better included in a West India trip. The Guianas by ordinary tourists are neglected.

Obviously the journey may be made in either direction: as above, or in reverse order; but unless the season of the year invites a change the former sequence should by all means be followed. Thus taken the journey is one of ever increasing interest, until its culmination in the delightful harbor and city of Rio de Janeiro. Not that Peru is inferior to Bolivia and Chile, or Buenos Aires to Rio, let me hasten to add; each has its own peculiar charm; but one who begins with the West Coast will find the entire journey far more enjoyable and impressive.

When one should go depends more upon when one wishes to leave home than upon the conditions prevailing in South America; also upon one’s individual taste as to temperature. In brief, one may safely make the trip whenever it suits his convenience. Bearing in mind what so many seem to forget, that the seasons are reversed in the northern and southern hemispheres, one may leave home to escape either heat or cold, or to avoid March winds, as he may elect. In none of the countries to be visited is the variation between winter and summer so great as in the latitude of New York, nor is the tropical heat anywhere on the journey so intense as that on many days of every summer here.

Leaving the United States on a four months’ tour at any time between the middle of November and the last of August, I strongly advise one to visit the West Coast first. During the remaining three months, one who dislikes hot weather might better begin with Brazil. In December, January, and February, the mercury at Rio is mostly in the eighties. In January I found it comfortable enough for summer weather, but I needed the ten degrees lower temperature of an earlier or a later season to make my visit absolutely ideal. 3With a delightful climate during nine months of the year, the city at any time is perfectly healthy; since the yellow fever, formerly a dreaded scourge, was stamped out at Rio during the same period that this was accomplished in Panama.

Buenos Aires also may be more advantageously visited during the cooler weather, both because the opera and social festivities are then in full swing, and because one is likely to be more energetic for sight-seeing, of which there is much to be done. In Peru and Bolivia, on the usual route of travel it is never hot enough to be troublesome. Chile, in the central and most visited portion, is a trifle less agreeable during the southern summer than in spring or fall, especially on account of the dust, but this matters little for a brief stay.

Four months should be allowed for the trip. A couple who made it in three, though delighted with their journey, mourned over the unavoidable omissions and were planning to go again. Six months is not too much; a whole year could be profitably employed: but in four months or a trifle more, one may visit the most important places and gain a fair idea of the various countries. The personally conducted parties for three months only are well worth while.

The expense of the trip will naturally vary according to the time and extent of the journey and the economy or extravagance of the tourist. A round trip ticket from New York to New York, good either by the Straits or across the Andes, may be purchased for $475, or including a return by way of Europe for $505. Additional expenses may be from $500 or less to $1000 or more according to the person, the time, and the number of side trips taken. By several tourist agencies personally conducted parties are semi-annually dispatched to South America at a cost varying from $1375 for a tour of 98 or 99 days to $2250 for 146 days. Also the Hamburg-American Line has sent a ship around to Valparaiso by way of the Straits. Tickets $475 to $3000; optional extra shore trips $300 or more. On the completion of the Canal they will probably have a ship making the entire circuit.

Persons who prefer to be relieved of care, or who do not speak Spanish, the language current at all points of the journey save Brazil, and there understood by educated people, will do well to join a party, especially if their time is limited. 4Those who can devote a longer period to the trip and who like to do their own planning may see more by themselves at either greater or less expense. One who speaks only English, by keeping to the main line of travel and patronizing the leading hotels, should have no serious difficulty; though it is, of course, an advantage, readily gained by one who is familiar with Latin or French, to have some acquaintance with Spanish, an easy and beautiful language. A bare smattering picked up from a phrase book on the voyage is better than nothing, while a conversational knowledge greatly enhances the pleasure and profit of the journey.

Baggage. In regard to baggage, the less taken the better, both on account of the expense and because of the care it entails; yet it is well to have a fair supply of good clothes, since evening dress is everywhere more strictly en règle than in most parts of the United States. The steamships are not all rigid as to the precise amount of baggage, though the allowance on different lines varies from 150 to 400 lbs.; the railroads are strict and extra baggage is expensive; only 100 lbs. are allowed. Going up to Bolivia by the Southern Railway of Peru, a heavy box or two may cost as much as the ticket. Many tourists take only hand baggage to Cuzco and La Paz, leaving on board the steamer their heavy pieces, to be reclaimed later at Valparaiso. On all roads, the hand baggage goes free; hence suit cases, etc., are much in evidence.

Clothing. One needs a supply of both light and heavy weight, the proportion of each depending upon the season of the year. Always by way of the Isthmus there are eight or ten days of summer weather en route, and several weeks during the East Coast journey. Along the seaboard of Peru and Chile woolen or heavy underwear may be desirable for many, as on the highlands of Peru and Bolivia; also in Chile and Argentina during their winter season, when a temperature in the forties and fifties will be experienced; some hotels have no fires, and the nights and mornings are chill. On the mountain railways, as during a portion of the sea voyage, wraps and rugs are needed in addition to moderately heavy clothing. Furs though unnecessary may be found agreeable during the months of winter, June to September.

Money may be carried in letters of credit on W. R. Grace or 5other bankers, or by American Express or Travelers’ Cheques, together with a moderate supply of gold, preferably in English sovereigns. The English pound, being precisely the same as the Peruvian, is interchangeable with them; in other countries it is more acceptable and convenient than American gold, though in the large cities either will be readily exchanged. A point to be noted and remembered is that most resident Americans and English, a few natives, and travelers in South America generally, speak of certain coins, soles or pesos, as dollars; a poor custom which should not be imitated. Since it is prevalent, one must be on guard to avoid mistakes. In Panama a clerk or a coachman saying twenty cents or one dollar means silver; i. e., 10 and 50 cents, United States currency. A man in Lima who speaks of twenty dollars probably means soles, practically ten dollars. In Bolivia a bolivian is about 40 cents, a peso in Chile is 22 cents more or less, in Argentina 44, in Uruguay $1.04; in Brazil a milreis is 33 cents. All of the countries divide their unit decimally, and if it were not for the foolish custom of English-speaking folk, there would be no confusion. In this book the words dollars and cents and the sign $ will everywhere signify United States currency; otherwise the names employed by the respective countries will be used, as soles, pesos, and centavos. In connection with Brazilian money the sign $ is put after the number; thus 15 milreis is written 15$000.

In 1903, before the United States’ occupation, there was no choice as to means of transport to the Isthmus. A single steamship company, that of the Panama Railroad, dispatched a vessel from New York once a week. Now there are four different lines with as many weekly sailings, besides one from New Orleans, a more convenient point of departure for many south of Mason and Dixon’s line. The four companies, all with headquarters in New York, will gladly furnish the latest information in regard to their own sailing and accommodations as on other points in reference to the tour.

Fares. The lowest fare from New York to Colon, $75.00, to Panama, $78.00, is the same on all lines, better accommodations being provided for a supplementary fee of from $15.00 up. It is wisdom to purchase, if not a ticket for the round trip, one as far at least as Mollendo, $191, as a slight reduction is made on through tickets. Stop-overs are allowed at any of the ports of call, and on the East or West Coasts of South America the journey may, if more convenient, be resumed on certain other lines of steamers without extra charge, save for embarking or disembarking in the small boats.

The respective merits of the four steamship lines to Panama are a matter of opinion. On three of these I have enjoyed the voyage, especially my last in a luxurious suite on the Prinz August Wilhelm of the Atlas Hamburg-American Line.

The old Panama Company claims that its boats are provided with all of the comforts afforded by the others, including rooms with private baths. It has slightly irregular sailings, seven a month, with several steamers making the journey in six days, instead of the seven, eight, or nine occupied by ships of the other lines. Those who prefer American cooking or the shorter voyage will choose one of these ships.

7The Royal Mail and the Hamburg-American lines are quite similar to each other in service and accommodations; the boats of the former sail for Colon on alternate Saturdays, calling on the way at Antilla, Cuba, and at Kingston, Jamaica: those of the latter sail every Saturday, touching at Santiago de Cuba and Kingston. The Royal Mail Steamers are scheduled to arrive at Colon on Sunday, eight days from New York, connecting with the P.S.N. boats departing on Monday for the south. But through tickets are good by any of the three lines on the other side; and one may delay on the Isthmus for a few days or weeks of sight-seeing. The Hamburg-American steamers arrive at Colon Monday, one week connecting with a P.S.N. steamer, the next with one of the Peruvian and another of the Chilian Line sailing the same afternoon. No one, however, who is making a pleasure trip should cross the Isthmus without staying over a few days.

The United Fruit Company boasts of a great white fleet with four sailings to Colon a week; two, on Wednesday and Saturday, from New York; and two on the same days from New Orleans. These ships, they say, are the only ones going to Colon which were designed and built especially for tropical service, thus having all of the latest devices for comfort as well as for safety. Among these are bilge keels and automatic water-tight compartments. A wireless equipment as a matter of course the boats of all lines carry; these have also a submarine signal apparatus, to give warning of the proximity of another vessel, and, as an especial feature, lifeboats which with a patent lever may be swung off and lowered by a single man. By the system of ventilation the temperature of the rooms at night may be kept down to 55° if desired, a boon to many on the muggy Caribbean; and the electric lights have the rare quality of burning low. All of the boats on the various lines have pianos and music, most of them cards, checkers, chess, and libraries, the United Fruit Company supplying the latest magazines.

The Saturday steamers of this line from New York call Thursday at Kingston, Jamaica, where they remain until two p.m. Friday. They are due at Colon at noon on Sunday. The Wednesday steamers take a day less for the trip; at Kingston where they arrive on Monday they remain from 7 8a.m. till 4 p.m. The Isthmus is reached at 1 p.m. on Wednesday.

Via New Orleans. The opportunity to go by way of New Orleans may appeal, especially in winter, to some who have not visited that city and to those who desire to avoid the possibility of two or three cold stormy days on the sea before entering the regions of perpetual summer. The steamers sail in five days to Colon, the Saturday boats arriving Thursday a.m. and the Wednesday boats Monday morning.

The voyage to Panama, indeed all of the six or seven weeks on the sea, which are a necessary part of this tour, will be likely to prove an agreeable experience even to those who as a rule do not enjoy the ocean. While the waters of the Atlantic may at any season be turbulent and tempestuous, the portions of both oceans which are to be traversed are for the most part so smooth that unless persons are determined to be seasick whether they have occasion or not, it is probable that they will suffer little or none from this unpleasant malady. Ordinarily the sail to Panama, under sunny skies, over unruffled seas, in weather, after a day or two, warm enough for summer clothing, is a pleasure unalloyed. On the Caribbean it may be a trifle muggy and sticky, but if favored with sunshine the wonderful blue of the waters, deeper than that of the Bay of Naples, affords solace. On some of the ships a little dance on deck, if happily under a tropical moon, may be an experience affording delightful memories.

Watling’s Island. After leaving New York harbor and the adjoining coast the first land to come within range of vision is that of Watling’s Island, noted for a lighthouse of great power and value. Otherwise unimportant, it acquires interest from the fact that on this shore Columbus is believed to have made his first landing in the Western World. The island is thus entitled to the more pretentious name, San Salvador, bestowed by the great explorer upon the land where first he trod in devout thanksgiving, after many weeks of painful suspense upon the limitless ocean.

Fortunate is the traveler who towards sunset enters Windward Channel, passing before dark the desolate wooded bluffs of the eastern extremity of Cuba, Cape Maysi, and later having a look at the southeast shores where rise sombre, forest 9covered peaks to an imposing height, the loftiest above 8000 feet. From a Panama or United Fruit Company steamer no more will you see of Cuba; but on a boat of the Royal Mail you will already have called at Antilla, in the eastern section of the island’s northern shore, a new and growing seaport on Nipe Bay, and the north terminus of the Cuban Railway. Extensive docking facilities have been provided, large warehouses, immense tanks for molasses, a good hotel: and plans are made for building here a great commercial city.

Santiago de Cuba. By the Hamburg-American Line the first call is made on the south side of the island at the more famous and considerable city, Santiago de Cuba, which, founded in 1514, is said to be the oldest settlement of size in the Western Hemisphere. With a population of 50,000, among Cuban cities it comes next to Havana. It has also historic interest. That Hernando Cortez from this port, Nov. 18, 1518, set out for the bold conquest of the Aztec Empire is a fact less widely known than the more recent circumstance that in this sheltered harbor the fleet of Admiral Cervera lay concealed, until July 3, 1898, it sailed forth to its doom. In the narrow portal, less than 600 feet wide, rests the old Merrimac, sunk by Lt. Hobson and seven others, June 3, 1898. On the right of the entrance, crowning a bluff 200 feet high, is the old Morro Castle, an ancient fortress of picturesque appearance, begun soon after the founding of the city and possessing towers and turrets in genuine mediæval style. Six miles farther, at the head of the bay, on a sloping terrace with steep hills behind, is the bright, gay city; though at the noontide hour it may seem a trifle sleepy and dull.

If time permits, a drive on the fine roads will be enjoyed. To the San Juan battlefield three miles distant and to El Caney a little farther the fare is $1.50 for a single person, $2.00 for several. The longer drive to Morro Castle, fare $3.50, affords charming views. In the city one proceeds first to the plaza, where on one side is the great cathedral called the largest in Cuba, containing rare marbles and mahogany choir stalls. On the other sides are the Casa Grande Hotel and the Venus Restaurant. Near by is the Filarmonia Theatre where the famous diva, Adalina Patti, is said to have made her début. A few may care to visit the spot where the Captain and sailors 10of the Virginius were executed as filibusters in 1873, a slaughter pen near the harbor front to the east of the Cuba Railway Station. An inscribed tablet there commemorates the sad event.

Kingston, Jamaica, is visited by all of the steamers except those of the Panama Line, the Wednesday boat of the United Fruit Company having previously touched at Port Antonio on the northeast end of the same island; the port, a busy place, owing its present prosperity chiefly to our fondness for bananas. Captain Baker of Boston in 1868 began the trade which the United Fruit Company has developed to immense proportions. The splendid Hotel Titchfield which the company has erected affords every facility for a delightful summer outing during our winter season.

The older and larger city of Kingston is on the south side of the island, by the excellent and far-famed harbor of Port Royal. The town of that name, ancient rendezvous of Morgan and the buccaneers, once stood on the long sandy spit which separates the bay from the ocean. But on a day in 1692 occurred one of those memorable tragedies at which the whole world stands appalled. The earth was shaken. The city sank beneath the sea, where it is said that some of the buildings may yet be seen, when the waves are still, deep down below the smiling tranquil surface. Kingston, then founded on the main shore, recently suffered (January 14, 1907), as we well remember, a similar though less complete disaster, being merely shaken down instead of swallowed up. Like San Francisco it was promptly rebuilt with better architecture. Quite up to date with electric cars and other modern conveniences, it is an attractive place of scenic and tropical beauty, excellent too for shopping. Interesting are the markets, the old Parish Church, badly shaken, but still standing; the main streets, King and Queen, at right angles to each other; the Jamaica Institute with museum and library where among other historical curios may be seen the famous Shark papers, in 1799 thrown overboard, swallowed by a shark, but soon after rescued from his maw, to the discomfiture of the Yankee captain of the Nancy, an American privateer. In the suburbs of the city within easy reach is King’s House, the fine residence of the Governor-General. Worth visiting (electric 11cars) is Hope Gardens, an estate of 220 acres, with a fine collection of indigenous plants and many exotics. The splendid roads over the island, the possibilities for delightful excursions,—the most enchanting the ascent of Blue Mountain, 7423 feet,—would tempt to a longer stay. But we hasten onward to more distant and greater glories.

Western Tourists. Tourists living west of the Rocky Mountains may prefer to sail from San Francisco or Los Angeles to Balboa, the port of Panama, at a considerable saving of expense, though not of time. Express steamers twice a month make the voyage from San Francisco in 14 days with the single call at San Pedro (Los Angeles), fare $85; while three times a month there are other boats which do not stop at San Pedro, but make eleven calls in Mexico and Central America, thus affording opportunity to see some of those ports, consuming 26 days on the trip. On these steamers the fare is $120. All these boats are of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. By way of New York the journey from San Francisco to Panama may, with close connection, be made in 10 or 12 days.

European Tourists may sail from Southampton by Royal Mail steamer in 18 days to Colon, fare $125, or from Cherbourg, 17 days, fare $100.

Other companies which have steamers sailing from Europe to Colon are the Hamburg-American, four times monthly from Havre and Hamburg, the Leyland C. Harrison, three times a month from Liverpool, the Cia. Generale Transatlantica, once a month from St. Nazaire and once from Bordeaux, the Cia. Transatlantica and the Cia. La Veloce, each monthly from Barcelona and Genoa.

Two days from Jamaica, six, seven, eight, or nine from New York, one arrives at Colon, eager to witness the wonderful operations now well-nigh concluded, or to behold the finished work, when great ships, no longer halting at the Atlantic shore, shall, through a broad channel among green hills and islands, sail onward to the serene Pacific. Every one knows of the marvellous transformation on the Isthmus during the last ten years, but the most imaginative person, now arriving for the first time, will hardly fancy what it was like in 1903.

Colon, once called the most repulsive, disagreeable, filthy hole of a place in all Christendom, though always a pretty picture from the sea, is at present fair enough on land. The climate only remains unchanged. It still rains—and rains: 130 inches a year: not all the time even in the rainy season, which it is very apt to be, as that continues eight months, from the first of May to January, leaving a dry season of only four. Even in this period it is liable to rain, so it behoves every one to be provided with raincoat and umbrella, if not with overshoes. Everywhere there are good walks and in the towns, paved streets, beyond which the tropical sun soon dries the mud.

The agreeableness of the Isthmian climate as a whole and in various localities, if to some extent indicated by figures, is largely a matter of individual temperament. With little difference in temperature Colon has double the rainfall of Panama with a corresponding excess of humidity. Yet happily for the welfare of the great work and the workers, it has been the fashion on the Isthmus for every one to have local pride; to like his own station the best, whether on either shore, or in one of the pleasant villages along the line. It is genuine summer weather all the year around; not excessive heat, like 13our days in the 90’s and 100’s; but mostly in the plain 80’s by day, with cooler and comfortable nights.

This section of the New World was first visited in 1501 by Columbus, who touched at Nombre de Dios and Porto Bello east of Colon, perhaps sailing into Limon Bay; this he certainly did in 1502, naming the place Puerto Naos, Navy Bay, as it was called until recent years. It is just 400 years ago, September 25, 1513, that Vasco Nuñez de Balboa first saw the great Pacific, then named the South Sea,—not, as often said, from the hill near Gorgona, called Balboa, more properly the Cerro Gigante, but from another 120 miles east, as he was crossing the San Blas country. Thence he continued to the Bay San Miguel of Darien. This bold explorer, like many another, fared badly. He was beheaded a few years later at the age of forty-four. In 1519 the site of an Indian fishing village near the farther shore was selected by Governor Pedrarias as that of his future capital, and in 1521, it was made a city by royal decree. This was Old Panama which soon became a place of great wealth and luxury, as for a century or more the rich treasures of Peru passed by this route to Old Spain. Yet it suffered many vicissitudes from fires, buccaneers, and insurrections till at length, when its prosperity had already begun to wane on account of the ships going by the Strait of Magellan, it was captured, plundered, and destroyed, by the freebooter, Henry Morgan, January 19, 1671, never to be rebuilt. January 21, 1673, the new city of Panama, about four miles distant, was dedicated. Until 1821 the Isthmus was under the dominion of Spain, and after that, in spite of numerous insurrections, remained a part of the country of New Granada, later Colombia, until its sudden practical transfer to the United States. On November 3, 1903, its independence was proclaimed, on the sixth the infant Republic was recognized by the United States, and on February 26, 1904, a treaty with the United States was signed by which it became a Protectorate, with a position similar to that of Cuba.

As early as 1527 an explorer from Panama city went from the Pacific up the Rio Grande Valley, crossed the divide by Culebra and sailed down the Chagres River to the Atlantic Ocean. Soon this was a popular route,—to sail up the Chagres to a point fifteen miles from Panama and continue by land to that city. As early as 1534 the idea of a canal occurred to that great monarch, Charles V, who had a route surveyed. Pronounced too expensive even for his great wealth, the project was abandoned, but 381 years later, 14a far greater canal than he dreamed of will be opened in the very same track which his surveyors followed.

Various canal projects in the meanwhile have been cherished, though the building of the Panama Railroad, 1850-1855, had a deterrent effect on the enterprise; but in May, 1876, the Government of Colombia made a concession for the work to a French Company and operations soon followed. After surveys by Lieutenant Wyse a sea-level canal from Limon Bay to Panama by the pass at Culebra (meaning snake) was decided upon. January 10, 1881, Ferdinand de Lesseps, promoter of the Suez Canal, made the ceremonial beginning at the Pacific entrance, and January 20, 1882, the first excavation was begun near the continental divide where, in the section called the Culebra Cut, work has proceeded ever since except from 1888 to 1891. The French were badly handicapped by disease, Colombian interference, incomplete plans, and insufficient funds, and were injured at home by rumors of sickness, extravagance, etc. In 1887 the sea-level plan was transformed to a lock-level, and February 4, 1889, the company went into the hands of a receiver. Several persons were convicted of fraud including Ferdinand de Lesseps, who, eighty-six years of age, was probably in entire ignorance of the business details. He died soon after.

In 1894 energetic work was recommenced by the new company which continued operations until the Americans took possession, May 4, 1904. $225,000,000 had been spent upon the work for which the United States paid $40,000,000. Recently it was estimated to have been worth $42,799,826. The advantages of the Americans over the French in having political control of the region, modern sanitary methods, better means of excavating, and unlimited money should be considered; and due credit and admiration should be awarded by all to de Lesseps and the Frenchmen who did so much, according to the verdict of praise rendered by our own engineers.

Panama Canal. In June, 1904, Chief Engineer Wallace, Col. W. C. Gorgas, and others sailed to the Isthmus to pursue the great work which had been transferred to the United States, May 4, by the French. Digging in the Culebra Cut was continued, but the chief labor for two years and a half was to remedy the unsanitary conditions, to provide accommodations for the employees, to perfect the organization, to reconstruct and double-track the railroad, and to improve the terminal facilities: necessary preparations for the colossal task. The sanitation of Colon and Panama included repaving, 15sewerage systems, and fresh water supply, as a part of the war against yellow and malarial fever. A proportionate sum spent on sanitation in the United States would be $12,000,000,000 a year, one-third of the entire amount devoted to all government expenses. Since January, 1907, the work has progressed rapidly, so that the canal is expected to be completed and in operation some time before the date of its formal inauguration January 1, 1915.

In spite of being hampered in many ways, much valuable work was accomplished by Chief Engineer John F. Wallace, who resigned after one year, and by his successor, John F. Stevens. He serving until 1907 is said by Col. Goethals to have laid out the transportation scheme in a manner which could not have been equaled by any army engineer. The engineering skill and the great administrative ability of Col. George W. Goethals, Chairman of the Isthmian Canal Commission, Chief Engineer, President of the Railroad, Governor of the Zone, etc., are so well known and already so highly honored as to need no encomiums here. A benevolent despot, able, wise, just, and honest, it is indeed a pleasure in this day and generation to find one as to whose virtues all are agreed, whose undying fame is as yet free from the malice of petty jealousy.

The length of the Canal, from deep water on one side to the same on the other, that is, from the Toro Point breakwater on the Atlantic side to Naos Island on the Pacific side, is about 50 miles,—40 miles from shore to shore. From the Atlantic entrance, by a channel 41 feet deep with a bottom width of 500 feet, it is seven miles to Gatun, two-thirds of which is in Limon Bay, the rest apparently along a fairly broad river. At Gatun, as everybody knows, are the locks, a double series of three, by means of which the ships will be raised 85 feet to the level of Gatun Lake. This, with an area of 164 square miles, is without doubt the largest artificial sheet of water in the world. The lake naturally has a widely varying depth and a highly irregular shape, with large and small arms, promontories, and islands; but vessels may sail at full speed along a channel from 500 to 1000 feet in width for a distance of 24 miles until at Bas Obispo the Culebra Cut is entered. This, about nine miles long, has a bottom width, except 16on the curves, of 300 feet only, making a slower rate of speed necessary. At Pedro Miguel the ship will be lowered by one lock to a smaller lake covering 1200 acres, 30 feet below. A mile and a half beyond, at Miraflores, the ship, by means of two locks, will return to sea level, thence sailing on, 8½ miles more, out into the Pacific.

The sail from ocean to ocean will to all be of intense interest, though more highly appreciated by those who visited the region before it was submerged, watched the great shovels cutting away the range of hills which forms the continental divide, and saw the locks in process of formation.

The great Gatun dam seems a wonderful creation, though the only remarkable feature is its size. It should be borne in mind that the extensive surface of the lake among the hills does not cause any greater pressure upon the wall of the dam than if it covered but a single acre; the depth of the water being the determining factor, not the extent of surface. The dam is nearly a mile and a half long at the top; half a mile wide at the bottom, 400 feet at the water surface, and 100 at its crest, designed to be 105 feet above sea level and 20 feet above the normal level of the lake: a very wide margin of safety. Of the entire length of the dam only 500 feet, a small fraction, one-fifteenth, of the whole, will be exposed to the maximum water head, 87 feet. The thickness of the dam is greater than was deemed necessary by engineers, with the result that there is no seepage: but it was thought best to satisfy over-apprehensive Congressmen by the employment of excessive caution. The interior of the dam is an impermeable mixture of sand and clay obtained by dredging above and below, placed between two parallel ridges of rock and ordinary material obtained from the steam-shovel excavations. The upstream slope of slight grade is thoroughly riprapped ten feet below and ten above the mean water level. The 21 million cubic yards of material composing the dam, which covers 400 acres, is sufficient to build a wall three feet high and thick nearly halfway around the world.

The Gatun Lake will receive all the waters of the Chagres basin of 1320 square miles and will contain at its ordinary level 206 billion cubic feet of water. An outlet, an obvious necessity, is provided in the spillway, a cut through a hill 17of rock nearly in the center of the dam, southwest of the locks. This opening, lined with concrete, is 1200 feet long and 285 feet wide, with the bottom, at the upper end ten feet above sea level, sloping down.

Until the construction of the dam was well advanced the water from the Chagres and its tributaries flowed out through this opening. Then it was closed at the upper or lake end by a dam of concrete 808 feet long in the form of an arc of a circle, its crest 69 feet above the sea. Upon this, 13 concrete piers rise to a height of 115.5 feet, with steel gates by which the water level of the lake will be regulated.

The immense double locks deserve more than a cursory glance. Similar in construction and dimensions, each has a usable length of 1000 feet and a width of 110 feet. The chambers have floors and walls of concrete with mitering gates at each end. The walls, perpendicular on the inside, are 45 to 50 feet thick near the bottom, but the outer walls narrow from a point 24 feet above the floor to a thickness of 8 feet at the top. The middle wall separating the double locks is 60 feet thick and 81 high, with both faces vertical; but in the upper part it is not solid. A tunnel in the wall has three divisions, the lowest for drainage, the middle for electric wires to operate the gate and valve machinery, the highest as a passage way for the operators. An enormous amount of concrete has been employed for the locks, four million or more cubic yards, with as many barrels of cement, enough to make a sidewalk 9 feet wide and 6 inches thick more than twice around the world.

Matching the walls are immense steel gates, 7 feet thick, 65 feet wide, and from 47 to 82 feet high, with a weight of from 390 to 730 tons each. At the entrance to the locks are double gates, also at the lower end of the upper lock in each flight, in case of ramming by a ship accidentally breaking through the fender chain; for there are 24 chains in addition to the gates, to prevent the gates being rammed by a ship under its own steam or having escaped from the towing locomotive. The chains will be lowered into a groove to allow the ships to pass.

Ships will not be permitted to enter the locks under their own steam, but will be towed through by electric locomotives, 18usually four to each vessel, two ahead and two astern, the latter to keep the vessel in the middle, and in the right place. The gates and valves are also operated by electricity, with power obtained through water turbines from the head created by Gatun Lake. The locks will be filled and emptied by a system of culverts, one of which, about the size of the Hudson River tunnels of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 18 feet in diameter, extends along the side and middle walls, with smaller branches under the floor of the locks. The water enters and leaves by holes in the floor. The culverts are so arranged as to economize water by passing it from one twin lock to the other. To save both time and water each lock chamber has a single gate near the middle dividing it into two parts, only one of which will be used for vessels less than 600 feet long. To fill and empty a lock will require about 15 minutes: to pass through the three at Gatun, about an hour and a half, and as much more to go down the locks on the Pacific side. The entire passage through the Canal will occupy 10 or 12 hours according to the speed of the ship, in the narrower parts all being obliged to go slowly. While it is hoped that the first steamer will pass through the Canal in December, 1913, if not earlier, there is no expectation of its being open for general traffic before the summer of 1914.

Colon. Passengers arriving on a Panama Railroad Steamship at Christobal, practically a part of Colon, may find waiting on the dock a special train to carry them across the Isthmus. The tourist, en route to a Pacific port, with his heavy baggage checked through, may let that go on to Balboa, the place of embarkation on the other side, and himself remain with hand luggage to look about Colon. Tourists on other steamers land at a Colon dock, from which it is a five minutes’ walk to the railway station. Men and boys are about, to assist with hand baggage. All that is checked through should be transported to Balboa without personal care; but the cautious traveler will have an eye upon it to see that it goes to the station here, and aboard the proper steamer on the Pacific side.

Hotels. Washington, E. P. Rooms $3.00 per day and up, December 1 to June 1. June to December $2.00. Meals $1.00 each or à la carte. Imperial Hotel, Park Hotel.

19Carriage Fare, 10 cents for one, 20 cents for two, 25 cents for three, 30 cents for four. By the hour 75 cents for one, $1.00 for two, and so on.

Regular trains for Panama (June, 1913) at 5:10 and 10:30 a.m., and 4:25 p.m.; time two and one-half hours. Inquire as to special sight-seeing trains.

Landing early in the morning one may have sufficient time to look about Colon and Christobal before taking the afternoon train for Panama. Those planning a longer stay, to enjoy some of the excursions available, will drive at once to the new Washington Hotel on Colon Beach, near the site of the old house of that name, which, giving way to its stately successor, now stands in the rear of Christ Church and there fulfills its original purpose to supply lodging for the railway employees. The new hotel, built of hollow tiles and re-enforced concrete in a modification of the Spanish Mission style, is quite up to date with baths, electric lights, lounging rooms, etc., broad verandas on the side towards the sea, and a pretty garden between the house and sea wall. A swimming pool has been constructed near by, 100x125 feet, from 3 to 9 feet deep, open on the sea side, where a baffle wall protects it from rough water. In 1903 I looked at the water with longing eyes, but the numerous sharks deter most persons from venturing into the ocean. The hotel with some rooms with bath, and others without, accommodates 175 persons. Like the Tivoli it has no bar, and since April 24, 1913, there are no saloons in the Zone outside of the cities, Colon and Panama, which except for sanitary regulations are under Panamanian control. The hotel enjoys a breeze all the year around and is said to be as cool as Bar Harbor in July, and no warmer in winter; but it did not seem that way to me when I spent a few days in Colon in 1903, the excessive humidity rendering the heat oppressive.

In the center of the garden in front of the hotel is a rather ugly monument, a red granite shaft on a triangular base, bearing busts of John L. Stephens, Henry Chauncey, and of William H. Aspinwall, after whom Americans called the town for some years. To these three men, in December, 1848, a concession was granted by Colombia to build a railroad across the isthmus. The discovery of gold in California made it possible to raise money for the enterprise. Work began in 201850, and the first train crossed the continent January 28, 1855. The passenger and the freight trade have been both heavy and expensive, so that from 1852 to the present time annual dividends of from 3 to 61 per cent have been paid. Most of the traffic to California and Oregon was diverted on the completion in 1869 of the transcontinental railway, but good dividends continued. In 1881 the French Canal Company bought most of the shares, as the road was an obvious necessity to their work; it therefore came into possession of the United States Government, May 4, 1904, when the purchase of the French rights, work, and equipment was consummated.

The city of Colon, which the Colombian Government very properly insisted upon calling after Columbus, is on the Island of Manzanillo (formerly separated by a narrow strait from the main land), a coral reef with a mangrove swamp at the back. Here in 1850 some shanties and stores were built by the pioneers of the railroad. The village grew and prospered in spite of the swampy location, which was improved by the deposits of rock and earth made by the French on the part now known as Christobal for the homes of the employees. In 1904 there were 10,000 people in the town, 9000 living in shanties on stilts in the terrible section back of Front street. Now in Christobal-Colon there are 20,000 people, and the place is drained and healthful.

Just east of the Washington Hotel is the gray stone building, modified Gothic, of Christ Episcopal Church, dedicated in 1865. Built by contributions from the Panama Railroad Company and various missionary societies, it was at first American, after 1883 Anglican, and in 1907 again American Episcopal. Whites and blacks here worship together, with a majority of negroes.

Half a mile farther on is the fine Colon hospital with 525 beds, of course a Commission affair. Built right over the water on piles a few feet high, one is almost tempted to be sick to be housed in so attractive a place. Beyond is the quarantine station where persons coming from plague or fever ports are detained six or seven days.

The numerous negroes from Jamaica and Martinique will interest many, their dwellings on the back streets, the drainage 21ditch, and Front street lined with stores, where curios of a sort could formerly be purchased better than in Panama,—bags or caps of cocoanut skins, heads carved from cocoanuts, and carved gourds, large and small, the latter used as drinking cups.

In Christobal are dwellings of the Canal employees; a large building occupied by the Commissary Department contains a cold storage plant, a bakery, and a laundry, which serve all the employees of the canal, the railroad, and the U. S. Government on the Isthmus:—these with their families numbering at times 60,000. Also there is a Commission Hotel with meals at 30 cents for employees, 50 cents for transients, providing better fare than can be procured in most parts of the United States for the price to employees; and a Y. M. C. A. building which supplies a reading room, opportunity for games and for social diversions including dances, lectures, and other entertainments. There are five other similar structures along the line.

At the end of the Point are two houses constructed for Ferdinand de Lesseps and his son, now moved closer together and devoted to offices of the Commissary and Health Departments. Beyond is the statue of the great Discoverer: the monument, cast at Turin, a replica of one in Lima, presented by Empress Eugénie to the Republic of Colombia to be erected at Colon. Columbus, of noble countenance, is represented in attitude of explanation to an Indian maiden personifying America, whose face expresses wonder and alarm.

Porto Bello. With time to spare an excursion may be made to the beautiful harbor of Porto Bello, 18 miles northeast of Colon, where the Commission has been operating, in a great rock quarry, one of the largest stone crushers in the world. Millions of cubic yards of rock have been taken from here, a smaller size for the concrete of the Gatun locks and spillway, a larger size for the Colon breakwater. Porto Bello and Nombre de Dios were the two safe harbors found by the Spaniards on this coast. The former has been a Spanish town since 1597. With a fine location the town is considered unhealthy, having an extraordinary amount of rain, 237 inches in 1909. A tug leaves Christobal wharf every morning returning at night. One has two hours or more to view the 22American settlement of 1000 people at the stone quarries and to cross the bay to the old village to see the finest ruins on the Isthmus: an old customs house, old bridges, the remains of Fort San Jerome, and the old plaza. There is a population of over 2000, with a church and stores.

Some miles beyond Porto Bello begins the large section of country inhabited by the San Blas Indians, who have been smart and sensible enough to keep the white man out of their territory, thus preserving their independence to the present day. They come to Colon to trade, but seldom allow a stranger to remain over night in their territory.

San Lorenzo Fort. Another excursion of interest is to San Lorenzo Fort, at the mouth of the Chagres River, either by sea in a motor boat, or better, in a canoe down the river from Gatun, a sail of ten miles, during which one has a glimpse of the real tropical jungle; the sea route affords a better view of the old fort. The remains are very complete, an outer wall, and a castle to be entered by a drawbridge. There are strong rooms, galleries for prison cells, manacles, etc., seeing which the tourist is apt to be more contented with his own lot. At the foot of the hill is the little village of Chagres.

In front of Christobal a construction of five piers is being made enclosing ten docks capable of berthing ships 1000 feet long, these being the Atlantic terminal docks for the canal. Across the bay is Toro Point. From this headland a breakwater has been constructed to protect the canal entrance and Limon Bay from the violent northers which occasionally visit this coast. It will also reduce the amount of silt to be washed into the dredged canal. From Toro Point the breakwater extends northeast for a distance of over two miles. The bottom width varies with the depth of the water; at the top it is 15 feet wide and 10 feet above mean sea level. A double-track trestle was first constructed, from which carloads of rock were dumped into the sea. The cost is about $5,500,000. It has recently been decided to construct an additional though smaller breakwater on the Colon side, extending west, some distance north of Christobal Point. Fortifications for the defense of the canal are being raised, both at Toro Point and on the east side at Margarita Island, one mile north of Manzanillo.

Four daily trains in about 2 hours at 3.00, 6.00 and 10.40 a.m. and 4.00 p.m. Special train for sight-seers, round trip fare $4.00, from Colon at 8 a.m., with barge service on lake, $1.50 extra.

Guides for tourist parties to inspect Canal, $7.50 per day, on application to Railway Ticket Agents, Colon or Panama.

While the sail through the great canal will be an extraordinary delight, the railroad ride will also afford much pleasure. On leaving Colon the line passes various docks, the Government printing plant, the marine shop and dry dock at Mount Hope, and the main storehouse of supplies for canal and railroad. On the east side of the railroad, opposite the warehouse, is Mount Hope Cemetery, where many French and others are buried, on a knoll which for a time was called Monkey Hill on account of the many monkeys there. These creatures are found in the woods all over the Isthmus. Stone piers which may be seen on the east beyond Mindi were erected by the French for a viaduct with the design of relocating the railroad. This, obviously necessary for the Americans, has been accomplished at a cost of nearly $9,000,000. In the swamp lands along here much papyrus is growing.

New Gatun. From Colon to Gatun a distance of 7 miles the track rises 95 feet. New Gatun, on the hill, is a village but a few years old, the site of the ancient town now being covered by the dam. In 1904 Gatun was a busy place on the Chagres River, where sometimes 100 dugouts loaded with bananas would tie at the bank, and seven or eight car loads a week would be shipped. In former days the railroad followed up the Chagres Valley, but now it is obliged to turn east to make a detour around the lake. It is desirable to alight here to examine the locks and if possible the spillway. Along the 24edge of the lock walls may be seen the cog rail for the towing locomotives, and farther back the return track without center cog. Tall concrete columns along the top of the walls are the standards for electric lights to illuminate the locks. Tall towers, apparently light houses, are range lights on the center lines of the straight stretches of the canal, so that a vessel lining up with the tower would know it was on the center line of the canal. From the building on Gatun hill containing the office of the Division Engineer may be had the best view of the canal obtainable from any one point. Northward are the waters of Limon Bay; and the masts of shipping at Colon harbor are visible. Close at hand are the locks and dam and a broad stretch of the lake.

Leaving Gatun the new road turns east along Gatun ridge, then south with pretty glimpses of the jungle, crossing the Gatun Valley to Monte Lirio. From this point it skirts the east shore of the lake to Bas Obispo at the beginning of the Culebra Cut. Several immense embankments were necessary to cross the Gatun Valley section above the surface of the lake, and others were made for dumping the spoil from Culebra Cut near its north end. Half a mile beyond Monte Lirio the railroad crosses the Gatun River by a steel girder bridge 318 feet long, built in three spans, one of which may be lifted to permit access by boat to the upper arm of the lake. Another steel girder bridge, one-quarter of a mile long, crosses the Chagres River at Gamboa, with the channel span a 200-foot truss, the other fourteen, plate girder spans, each 80 feet long. From this bridge, at the north end of which a new town-site has been laid out, a glimpse of the northern end of Culebra Cut may be had. It was originally expected to carry the road through the Cut, 10 feet above the water level, but the slides making this impracticable, the relocation has been made by cutting through a ridge of solid rock and working around east of Gold Hill, passing Culebra at a distance of 2 miles. Then the track runs down the Pedro Miguel Valley to Pedro Miguel Station, where it is within 300 feet of the locks. The highest elevation of the track is 270 feet above the sea about opposite Las Cascadas. The Continental Divide is crossed 240 feet above the sea in about the same line as Culebra.

Journeying by the new road from Gatun, the old traveler or 25resident will miss some familiar names, the bearers of which, if not concealed under water, are now remote and vanishing. Lion and Tiger Hills were small hamlets, but Bohio was quite a place, where the French had a machine shop. It was once considered as a possible site for the locks and dam. Frijoles (beans) and Tabernilla have been places of some importance and Gorgona of more, because here were the American machine shops, now removed to Balboa. The place with the peculiar name Matachin, which everybody remembered, will not be covered over with water, but like others farther on will relapse into a small hamlet. The prevalent notion that this name was derived from matar, to kill, and Chino, and was applied on account of the wholesale deaths of Chinese is incorrect. It is the Spanish word meaning a dance by grotesque figures.

Bas Obispo beyond Gamboa is one of the old places still visible, at the north end of the Culebra Cut. Near by, December 12, 1908, occurred the greatest accident in the construction of the Canal when 44,000 pounds of 45 per cent dynamite which had been packed into fifty-three holes were set off by the explosion of one, as the last hole was being tamped. As the hour was 11.10 many men were passing home to lunch. The hillside, falling into the Cut, as had been planned for a later hour, buried several men, and others were struck by flying rock. In all twenty-six were killed and a dozen permanently maimed. Near Bas Obispo is Camp Elliott, where a battalion of marines has long been stationed.

Empire. Las Cascadas, where once a stream tumbled down a precipice 40 feet towards the Chagres, formerly came next, then Empire, one of the largest of the Canal villages. Here the French began excavations in the Cut, as previously mentioned, January 20, 1882, before a large assemblage of officials of the Canal Company and of Panama. The work was blessed by the Bishop and the too common champagne celebrated the occasion.

Culebra was the real capital of the Zone after John F. Stevens in 1906 moved his quarters there from Ancon. Here has been the home and office of Col. Goethals, the head of everything, and of other prominent officials. In 1908 Culebra had a population of 5516, but is now much smaller. The side of the hill towards the Cut has been gradually slipping away, 26taking a part of the village, but so slowly that the houses were first removed to the rear slopes.

The average depth of the Cut through its nine miles of length is 120 feet. The heaviest point is near Culebra village between Gold Hill on the east side and Contractors’ Hill on the west, where the depth averages 375 feet. The summit of Gold Hill is 660 feet above the sea, of Contractors’ Hill, 410 feet. Beyond Gold Hill is the troublesome Cucuracha slide, though the largest is the one at the Culebra village on the west. One slide here involved 1,550,000 cubic yards. At this point the Cut is about 2000 feet across. The dwellings of the employees here, as at Christobal and all along the line, look very pretty and comfortable with their screened verandas. Market facilities have been good with prices generally lower than at home for meat and other things brought in cold storage from the States. The climate is not objectionable to the majority, and many will be grieved, when, the Canal being finished and only a select few remaining for its service, they shall be obliged to return home again. Some, no doubt, being now weaned from excessive affection for one particular spot, will go on to other parts of Spanish America. There, intelligent men of the right spirit, who have saved a portion of their earnings, will find agreeable opportunities for work and for investments of various kinds.

Beyond Pedro Miguel is the Miraflores Lake and the two Miraflores locks by which the ships reach sea level again. After passing through a concrete lined tunnel 736 feet long, Ancon Hill, overlooking the Pacific entrance to the Canal, is straight ahead. One more station, Corozal, headquarters of the Pacific Division, and the city of Panama is reached.

Hotels. The Tivoli, $5.50 and up a day, American plan; the Central, $3.00 a day, American plan; the International, Metropole, and several others, smaller and less expensive, but some of them neat and respectable.

Carriage Fare, 10 cents, U. S. currency, for one person, 20 cents for two, etc., in Panama City, or 20 cents and 40 cents silver, Panama money. Panama to Balboa docks, 50 cents U. S. currency.

Automobile Tariff, first hour, for cars seating five, six, or seven persons, $5.00, $6.00, or $7.00; second hour $1.00 less. Local fares 27about the city, 50 cents for each person. To Balboa Docks and return, $3.50, five-seat car; $5.00, seven-seat car. To Old Panama and return, $5.00, or $7.00, if within one hour; if more, on hourly basis.

Electric Cars, fare five cents, run every ten minutes from Hotel Tivoli past the railway station down Avenue Central to the National Palace near the sea wall; also beyond the Tivoli to the Catholic Chapel on the Ancon Hospital road. Of two other lines, one runs from Santa Ana Park by C, 16th, and B streets, and so on to Balboa; another branching from Central avenue at 13th street and following North avenue goes out the Sabanas road.

The Republic of Panama, proclaimed Nov. 3, 1903, by treaty of Feb. 26, 1904, came under the protection of the United States, receiving $10,000,000 cash for the sovereignty of the Canal Zone and after 1913 a yearly rental of $250,000. The form of government of the Republic is similar to that of the United States. The country is 340 miles long from east to west, from the Atrato River on the Colombia side to Costa Rica on the west. From north to south its widest point is 120 miles in the province of Veraguas, and the narrowest less than 40 in Darien. There are mountains 7000 feet high in Darien and 11,000 feet in Chiriqui; the lowest pass, 312 feet, is that used by the Canal and Railroad. The population, outside the Zone about 340,000, includes 36,000 Indians, and a very large proportion of negroes and mixed races. The country has excellent possibilities for agriculture and cattle raising, with smaller ones for minerals.

Panama. The new city of Panama, founded January 21, 1673, was soon protected by a sea wall, still standing, and on the single land side by a wall, and a deep moat crossed by a drawbridge. To make it proof against further raids two forts were erected on the land side and one by the sea. The residences built of wood suffered from various fires so that few old buildings remain, yet the masonry structures have the appearance of age. One hundred and twenty years ago the city had 7857 inhabitants, double that in 1870, and in 1911, 37,505.

Hotel Tivoli. Arriving at Panama, almost every one who can afford it will go to the Hotel Tivoli, near the station, delightfully situated at the foot of Ancon Hill, on the farther side of a small park called the Plaza de Lesseps. It is intended 28some day to erect in the center of the plaza a statue to the hero of the Suez Canal, initiator of the great work at Panama. On a knoll, overlooking the city and part of the bay, the hotel has many rooms opening on the broad verandas which afford charming prospects. The nights are comfortably cool, and the table affords good American fare. The hotel was erected by the Government especially to accommodate Canal employees on their arrival, and persons whose business with the administration caused them to come to the Isthmus. Also it was designed to afford recreation to employees on the line desirous of an occasional trip to the city. With this end in view a large dance hall was provided about 80x40 feet, where the Tivoli Club, organized among the employees, has given dances two Saturday evenings each month. The hotel, opened Jan. 1, 1907, has 220 guest rooms, and a dining-room seating 700. The building, 314 feet long with wings 156 feet deep, has a court in front 91 feet in depth with a carriage road and garden. Of late on account of increased travel the hotel has been enlarged and is much used by tourists. The prices, $5.50 a day and up, will seem reasonable enough to patrons of the large New York hotels.

The Hotel Central may be preferred by some on account of the lower prices, $3.00 and up, or because it is in the center of things on the principal plaza of Panama (now called the Independencia), opposite the cathedral; its location and its clientele afford an opportunity to see more of Spanish American life. The building is four stories high, in Spanish style around a central court or patio. Built in 1880 it has recently been renewed, and the rooms are large and airy. The table formerly left something to be desired, but has very likely improved with the competition. Once it was the only place where anybody could go.

The International Hotel is most convenient to the railway station on the Railway Plaza; a large fireproof building in Spanish Mission style, completed in 1912, and affording all modern conveniences. The smaller hotels on the Avenida Central may be patronized by those to whom the saving of a few dollars is important. The Hotel Metropole is pleasantly situated on the Santa Ana Plaza.

A new and modern hotel, accommodating 500 persons, built 29by British capital on Chiriqui Point overlooking the bay, is expected to be ready for guests in November, 1914.

Sight-seeing may begin from the Tivoli or International with a walk or ride down the Avenida Central, which goes first in a rather southerly direction, but in town when crossing the plaza about east and west. The northern part of the town is rather new, belonging to the Canal period, French and American. On the right at some little distance a three-story white concrete building, very ornate, with broad portico, is the club house of the Spanish Benevolent Society. Next door is the American Consulate. Two blocks farther is the Plaza Santa Ana, with trees, plants, and walks, where on Thursday nights there is a band concert and hundreds of people promenading. Besides the Church, there are saloons, a Variety Theater with roof garden, promenade balcony, and fine interior decorations, erected 1911-12, and on the west side the Metropole Hotel. On the road, one block south of the plaza, leading west to Balboa is the Santo Tomas Hospital, with 350 beds, under the direction of an American doctor with good nurses and physicians, maintained by the Panama Government. The three cemeteries are beyond, one each for Chinese, Hebrews, and Christians. Tragic tales are told of the yellow fever days, and space for burial is still leased.