Project Gutenberg's The Detective's Clew, by O. S. (Old Hutch) Adams

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

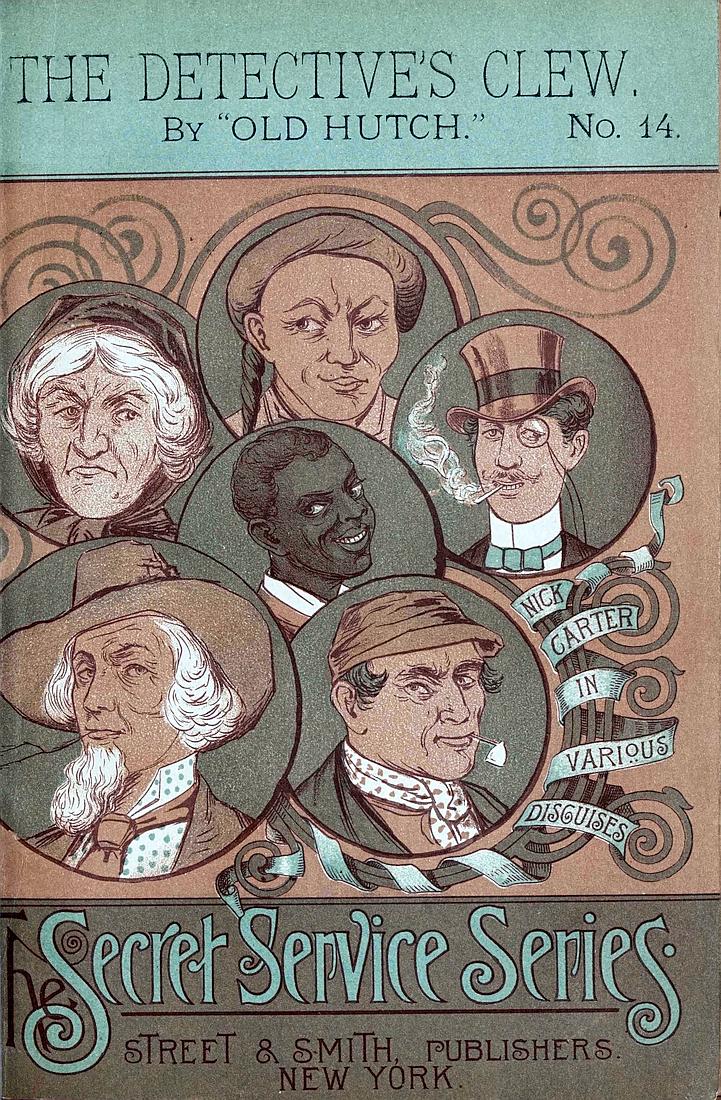

Title: The Detective's Clew

The Tragedy of Elm Grove

Author: O. S. (Old Hutch) Adams

Release Date: June 15, 2019 [EBook #59760]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DETECTIVE'S CLEW ***

Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

A Table of Contents was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book and are identified in the text by a dotted underline and may be seen in a tool-tip by hovering the mouse over the underline.

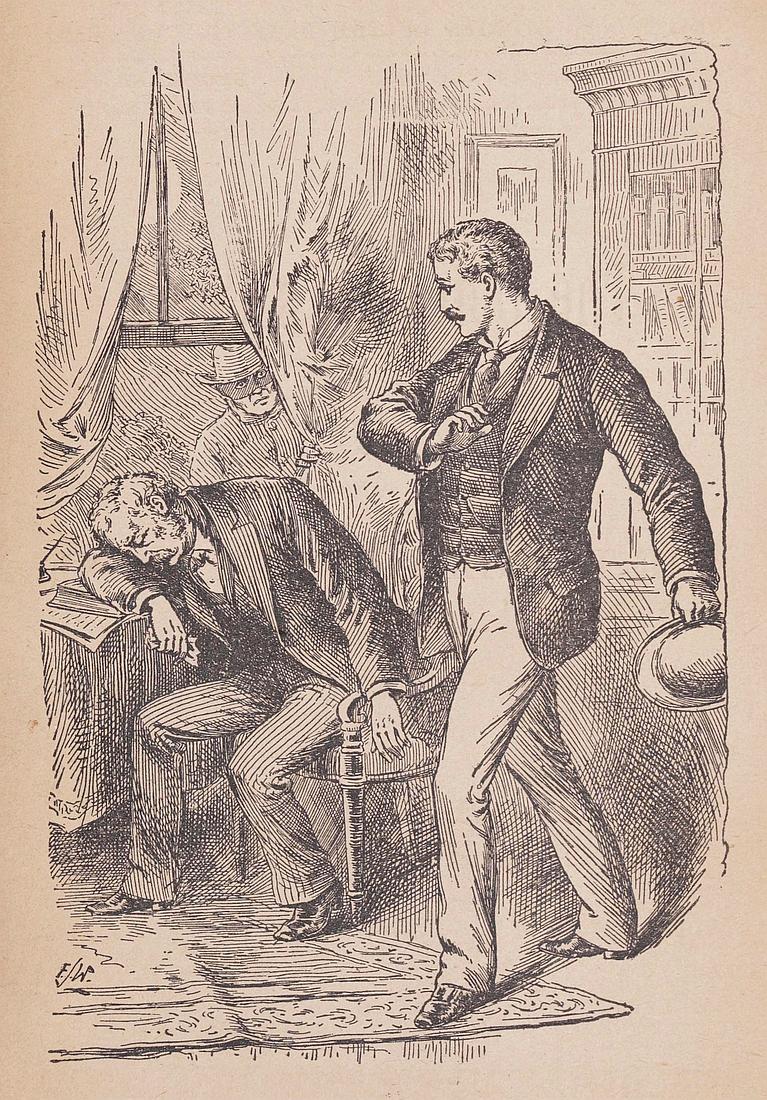

HE STEPPED AROUND TO THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOTIONLESS FORM.

(P. 28.)

THE SECRET SERVICE SERIES—NO. 14.

A Monthly Periodical,

DEVOTED TO STORIES OF THE DETECTION OF CRIME.

SUBSCRIPTION PRICE, $3 PER YEAR.

DECEMBER, 1888.

Entered at the Post Office, New York, as Second-Class Matter.

The Detective’s Clew:

OR,

THE TRAGEDY OF ELM GROVE.

BY

“OLD HUTCH.”

NEW YORK:

STREET & SMITH, Publishers,

31 Rose Street.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1888,

BY STREET & SMITH,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at

Washington,

D. C.

I. THE BROTHER’S MESSAGE.

II. GEOFFREY HAYWOOD.

III. “SEVEN O’CLOCK.”

IV. A FIGHT AND A FLIGHT.

V. THE WRONG MAN.

VI. UNDERGROUND.

VII. IN STRANGE QUARTERS.

VIII. THE ARREST.

IX. GEOFFREY HAYWOOD’S MOVEMENTS.

X. THE PRISONER AND HIS CAPTORS.

XI. THE EXAMINATION.

XII. THE NEW YORK DETECTIVE.

XIII. STRANGE DISCOVERIES.

XIV. THE CUSTOM-HOUSE DETECTIVE.

XV. FREE.

XVI. A REFUGE.

XVII. A GLAD MEETING.

XVIII. GEOFFREY HAYWOOD’S SECRET JOURNEY.

XIX. THREE INTERVIEWS.

XX. AN ADVENTURE THAT BEFELL THE REV. MR. WITHERS.

XXI. FLORENCE DARLEY.

XXII. THE NEW MUSIC-TEACHER.

XXIII. A STRANGE REVELATION.

XXIV. DANGER AND MORE EXPOSURE.

XXV. GEOFFREY HAYWOOD AT WORK—A MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE.

XXVI. A DARK NIGHT’S WORK.

XXVII. ON THE TRACK.

XXVIII. VICTORY.

XXIX. CONCLUSION.

THE DETECTIVE’S CLEW.

The little steamer Neptune plowed through the water, sweeping past lovely scenes of green verdure and jutting rocks, almost making her passengers regret that their journey’s end was so near. And, in truth, the approach to Dalton did form a most delightful close to a journey of some forty miles from one of the principal cities on the New England coast. The trip could be made by rail, but the Neptune had been fitted up by a company of enterprising men, who offered comfort and pleasure in opposition to speed and dust. The project succeeded well, the little steamer receiving its fair proportion of passenger traffic.

On she sped, cutting the water cleanly, and rapidly drawing near the wharf.

Two young men stood on the deck in a position where they could best view the town. One of them was a trifle below the medium height, but his form was well proportioned, and his features indicative of individuality and character. His complexion was rather light, and so was his hair, but his eyes were black, deep-set, and luminous. He had a frank expression, which was marred, however, for the moment by a look of uneasiness and a shade of sadness.

His companion was a fair sample of the young American of the present day. He was a trifle taller than his companion, well built, with brown hair and blue eyes, a dark mustache overhanging a well-cut mouth, erect in carriage, deliberate in his motions, his general appearance designating him to the casual observer as a “man of business.” You would naturally feel that he would be equal to any emergency—that his self possession would not be likely, even under trying circumstances, to desert him. Very different in this respect was he from his companion, who was plainly excitable, and whose total “make-up” suggested that he might not at all times be master of himself.

The latter spoke:

“I don’t know how my uncle will receive me, Leonard,” he said. “I almost tremble at going into his presence.”

“Nonsense!” said the other. “I should not tremble at all. All you have to do is to tell your story, and then, if he doesn’t behave himself, quietly bid him good-day.”

“Ah, I know that would be your way,” was the reply, “but I could not do it. He is my father’s brother.”

“Yes, and a model brother, too. His course has entitled him to so much respect that I should think you would be considerate of his feelings.”

The tone was impatient and ironical.

“But I am here for reconciliation, you know. They have been like strangers so long—never holding any communication with each other—and on his dying bed my father enjoined me to go to him and tell him how it all came about—how Geoffrey Haywood produced, by his lies and misrepresentations, an estrangement between two brothers that had always been so fond of each other. They were both passionate, and neither would seek explanations. Haywood was cool and calculating, and knew how to approach both of them.”

“And Haywood now lives in Dalton?”

“Yes; he still keeps on the right side of Colonel Conrad, and, I suspect, owes all his prosperity to his influence and aid.”

“When did your father discover that Haywood had been the means of the feud?”

“Nearly a year ago. His health was at that time poor, and he was unable to leave Europe, where he was traveling. He wrote to his brother, but the letter came back unopened. My father never grew better. He thought that, if I could see my uncle and lay the case before him, he might go down to his grave without the old hate rankling in his heart.”

The youth grew excited, and paced up and down the deck. Then he continued:

“I am to see this savage monster—this irate beast, as I have learned to regard him—and run the risk of hearing the memory of my father reviled, and his name insulted. It seems as if I could not bear it. His living face is yet too fresh in my memory. But the mission is intrusted to me, and I must fulfill it. I will tell him the facts, and my duty will have been done.”

Leonard Lester looked upon his cousin as he spoke, and smiled a pitying smile.

“It is rather tough,” he said, “to be obliged to get down on your knees to such an individual as I imagine your, or, rather, our uncle, to be—for I suppose he must be my uncle, since you and I are cousins, although I have never seen him. But I believe I am to accompany you, and if he lets off too much steam, I will let off some, too. I can do it, when there’s occasion.”

His eyes proclaimed the truth of what he said.

Leonard Lester and Carlos Conrad were distant cousins, and cherished a strong regard for each other. Carlos was the son of Anthony Conrad, who, years before, had married a Spanish girl. Her dark beauty had won the affection of the American, and they had lived together ten years, when she died. The only fruit of the union was a boy, whom they named Carlos. He inherited the warm and voluptuous nature of his mother, and the firm and stable, though somewhat passionate, character of his father. And there was within him a vein of delicate sensibility, peculiarly his own, which added to the refinement of his nature, though it might at times render him weak and irresolute. A considerable portion of his life had been spent in Europe, near the home of his mother, and in other portions of the Continent.

His father had died but a few weeks before the time at which this chapter opens, and had charged Carlos with a mission which, as we have seen, he was about to undertake.

Leonard Lester was connected with a large importing house in New York. He had been abroad on business for the firm several times, and had met Carlos in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and other places. The cousins seemed to gravitate toward each other, and a warm affection sprang up between them.

On this occasion they were going together to the residence of Anthony Conrad’s brother, Colonel William Conrad, whose home was in the suburbs of the beautiful village of Dalton.

The steamer bumped against the dock, making everybody give an involuntary pitch forward, and was soon fastened to her moorings. The plank was thrown out, and the passengers thronged ashore.

Leonard and Carlos stood looking about for a moment, endeavoring to decide which way to turn.

“Shall we go to a hotel?” asked Leonard.

“Yes, by all means,” quickly responded Carlos. “We will not intrude on his hospitality until we know what our reception is to be.”

“It will be all right, I will venture,” said Leonard, cheeringly. “If you have proofs of what you are about to say, he surely will not be so unreasonable as to turn you off.”

Carlos sighed, but did not reply, as they stepped into a hack. They were driven rapidly through the lively streets of the busy village, and conveyed to a hospitable-looking hotel. A pleasant room, which commanded a fine view of the ocean in the distance, was placed at their disposal.

After an hour’s rest and a good supper, they approached the hotel clerk, Leonard saying:

“I believe that Colonel Conrad is a resident of this place?”

“Yes, sir, he is,” replied the clerk.

“Can you inform me where he lives?”

“He lives on his place—Elm Grove—about a mile out of the village.”

“In what direction is Elm Grove?”

“Straight north, on this street—Main street it is called.”

“Thank you.”

And the cousins stepped aside.

“I wonder what they can want of Colonel Conrad?” mused the clerk, staring after them.

After discussing the matter, Carlos and Leonard determined not to visit their uncle until the next morning. So, after spending an hour in rambling about town, and by the shore of the bay, they returned to the hotel and retired at an early hour.

The next morning they set out for Colonel Conrad’s residence. The walk was dusty at first, but soon merged into a pleasant avenue, shaded on either side by ancient and noble trees. Then there was a gentle ascent, a slope downward, and a short distance farther, situated on a rise of ground, was Elm Grove, the residence of Colonel Conrad.

The heart of Carlos beat nervously, his step was hurried, and his motions were quick. Not so with Leonard. He was cool and composed, and, as the two passed through the open gate, and up the broad gravel walk, he said:

“Come, now pick up courage. Think of your father, be a man, and defend him from insult, whoever it comes from.”

The words had their desired effect. A look of resolution came into Carlos’ face, which Leonard regarded with satisfaction.

They ascended the steps and rang the door-bell.

A servant appeared.

“Is Colonel Conrad at home?” asked Carlos.

“I think he is,” replied the servant. “Shall I take your names?”

They handed him their cards. Carlos’ was edged with black. Soon the servant returned, and said that Colonel Conrad would see them.

They were ushered through a wide hall, on the left side of which was the room where Colonel Conrad awaited them.

The servant bowed them in.

The room was not a large one, but it was fitted up with elegance and taste. On one side was a row of shelves, on which were ranged books of all sizes and colors.

It was the colonel’s library, and a choice one it was, too, valuable principally for the age and rarity of some of the volumes.

There was a fire-place, a writing-table, a closed desk, heavy, rich, and antique in pattern, a huge clock, reaching from the floor to the ceiling, a smaller case of book-shelves near it, a couch, and a few chairs.

All this was taken in at a glance, as was also the figure of the proprietor of the mansion, seated in an easy-chair, with an open book lying on the table beside him.

Never were two persons more surprised than were the cousins at the appearance of Colonel Conrad. They had expected to see in their uncle a large, frowzy, ferocious-looking monster in human form, with a face expressive of malice, and that peculiar expression that always belongs to lips given to invective and denunciation.

Instead, there sat before them a man not above the medium size, with hair thickly tinged with gray, and a careworn, studious, thoughtful face. His eyes were blue, and, in contrast with his appearance otherwise, were bright as those of a youth of twenty. His brow was wrinkled irregularly, suggesting inward conflict and mental anxiety.

He sat and looked at his nephews steadily without speaking. Carlos gazed earnestly and apprehensively into his face, while Leonard stood in an easy attitude, apparently not in the least discomfited.

At length the uncle bent his gaze more particularly on Carlos. It was impossible to tell the thoughts that occupied his mind. Finally he said:

“You’re his son?”

“I am your brother’s son,” replied Carlos.

“I suppose it is unnecessary to ask what that means?” said Colonel Conrad, holding up the card edged with black.

“You can readily imagine,” said Carlos, with difficulty controlling his emotion.

The old man bowed his head for an instant, and then looking up again, said, impatiently:

“Well, well, why don’t you be seated? What are you standing up for? There are plenty of chairs.”

The cousins smiled, and acted on the hint thus conveyed.

“I’m a wonderfully forgiving man,” began Colonel Conrad; “if I were not, I wouldn’t so much as suffer your presence in sight of my house.” He was addressing himself to Carlos. “You know the old saying is that the sins of the fathers shall be visited on the children, and I ought to visit the sins of your father on you; for you know how he deeply wronged me, or at least you ought to know it, for if he didn’t confess it on his dying bed I should have but little hope for his future――”

“Colonel Conrad,” interrupted Carlos, endeavoring to control himself so as to appear calm, “you must not talk in that way. I’ll not hear it—no, not even from you. Your dead brother was a good man, and I, his son, will not hear his name traduced.”

“Y-o-u’-l-l not h-e-a-r his name tr-a-d-u-c-e-d!” repeated Colonel Conrad, in a prolonged, contemptuous tone, staring at Carlos with his piercing eyes. “I’d like to know what you are going to do about it?”

“I’ll defend him, sir, with my right arm,” said Carlos, rising to his feet. “I’ll call out the first man who dares to slander him. He was a good and true man, and I am here to prove it.”

“You had better sit down, young man,” said the colonel. “I suppose you have come here begging, but you’ll not gain anything by such behavior, I can tell you.”

“I am no beggar,” retorted Carlos, angrily, “and I will accept none of your money. But I have an errand to do, and after it is performed, I will leave you. It is a message from my father.”

“Well, Carlos,” said his uncle, suddenly assuming a nonchalant manner, “I see you have pluck, and I like you for it. But too much pluck is not always a good thing. I have had too much of it in my day, so has your father, the vil—but no, I’ll not call him names now; let him rest in peace.”

After a pause and a moment’s dreamy silence, he resumed:

“I have seen much sorrow in my time, boys, and have gone through some hard experiences. There was that quarrel with my brother—we were both hasty, and have not seen each other since. There was my wife—bless her memory!—who died many years ago, leaving me no children. Yes, I have passed through some sad experiences, and all I have to do in my old age is to sit still and think about them. I tinker a little with one thing and another—bother my head over machinery and philosophy—and that is about all I have to relieve the tedium of my life. But no, there’s Florence—she’s a good girl.”

The last words he spoke rather to himself than to his listeners.

“You have a nephew living in Dalton, have you not?” said Leonard, who had as yet taken no part in the conversation.

“A nephew? Oh, yes—Geoffrey Haywood, I suppose you mean. He is a very good man—very pious and very honest. He has met with great success in his business. Yes, Geoffrey is my best friend.”

He glanced up, as he spoke, in a slightly defiant manner, as if he expected to be contradicted; but seeing no such purpose on the part of his auditors, he ceased speaking, and drummed nervously on the table.

“Well, Colonel Conrad,” said Leonard, “Carlos has come here on an errand, and he wishes, though he dreads, to open the subject. It is from your dead brother, Anthony. Carlos knows of the enmity that existed between you and him, but he hopes and I hope that you will hear him through.”

The old man shook his head.

“No good can come of any talk about my dead brother,” he said, sadly; “but he may speak. I will hear what he has to say, for if his father left with him a message, it is his duty to deliver it.”

“Thank you for those words, uncle,” said Carlos, “for now I can go on and tell the story untrammeled. It is a tale of deep wrong, which should bring curses on the perpetrator. The quarrel between you and my father was the work of a villain, whose heart must have been black and rotten—whose sordid desire for wealth must have made him forget all that was noble and manly within him.”

Carlos then began at a period dating years back, giving the details of a plot that had separated Anthony and William Conrad, filling them with hate and venom toward each other. There was one who had caused it all—who had studied his plans well, and carried them out with fiendish precision; and who was now reaping the harvest of his mischief by living near Colonel Conrad, enjoying his friendship and—his gold.

“Need I mention the name of the villain?” asked Carlos. “Is not one, and only one, person brought to your mind, and that Geoffrey Haywood? Stop! do not interrupt me now. I must finish, and then I will go or stay, as you bid me. My father learned all the facts a year ago. He wrote to you, but the letter was returned unopened――”

“I never received it,” said Colonel Conrad, huskily.

“Ah! that is some more of Haywood’s work. My father’s health was poor, and he never left Europe after writing the letter. But a few weeks ago, on his dying bed, he told me about it, and charged me to come to you and inform you how you had both been wronged. He gave me this package to deliver to you, which he says contains convincing proofs. He died reconciled to you in his heart, and wished you to forgive him while he yet lived on this earth. Take the package and examine it impartially, for the memory of the love which you once cherished for your brother.”

Carlos laid the package down and ceased speaking. He had performed his duty.

Colonel Conrad’s head was bowed, and he appeared to be in deep thought. A hard, impenetrable look came across his features, and he said, in a perfectly calm voice:

“Carlos, your story is a strange one. If true, it is indeed a terrible record of wrong. You have done your duty, and I cherish no ill-will toward you. But I am lost and perplexed. Don’t you think it would stagger any man? I must think. You must leave me for the rest of the day—or rather I must leave you, for you will, both of you, be my guests. I must shut myself up. I will read the papers contained in the package, for that will be no more than an act of simple justice.”

“Thank you, my uncle,” said Carlos. “But I shall not consent to share your hospitality at present. As yet, you are my father’s enemy, and may continue to be so. We will remain at a hotel until you have investigated the matter and rendered a decision.”

“Yes,” said Leonard, “Carlos is right. For the present our abiding-place shall be the hotel.”

Colonel Conrad was not in a condition to dispute their decision or urge them to stay. His mind seemed to be under a cloud, and he made no reply to their remarks.

He did not rise, nor speak, but simply bowed, as they bade him good-day and took their departure.

No. 32 Main street was the most elegant store in Dalton. Silks and laces, arranged in perfect order and taste, graced its windows; the counters bore a new and polished look, and everything about it betokened unwearying care and constant watchfulness on the part of its proprietor. The clerks had a subdued look, and moved about in an automaton-like manner, like horses thoroughly broken in, or trained dogs going through with their parts. When their master passed through the store, their submissive expression was augmented, if possible; and if his keen eye detected nothing to disapprove, they shot glances of mutual congratulation at each other.

Geoffrey Haywood was not called a hard employer, nor an illiberal man, but those under him well knew that every cent they received was well and dearly earned. Nothing remiss was ever overlooked—no neglect of duty forgotten. When pay-day came, every inattention and inadvertence was found faithfully recorded against the delinquent.

Mr. Haywood himself was not bad-looking. With an erect, well-proportioned form, a luxuriant black beard and mustache always neatly combed and brushed, a fair complexion and black eyes and hair, he was called a handsome man. He had a fine set of teeth, which glistened brightly through his beard when he opened his mouth to smile. We say when he opened his mouth to smile, yet he seldom smiled. When occasion seemed to call for a look of pleasure, he would part his lips and show his teeth, but no other feature of his face altered its lines; his eyes shone no brighter—there were no crows’ feet at the corners; the embryo smile was nipped in the bud, it vanished into space, it diffused itself behind the glossy beard, and buried itself in the unfathomable depths of the glistening eyes. This movement of the mouth, this attempt at a smile, answered many purposes. It terrified delinquent debtors; it took all the starch out of a clerk whom it was desirable to awe; it sent beggars away abashed at their own audacity; it even said to the minister, “Keep on in your humble efforts, and you may possibly win my approval some day or other.”

On the day that Carlos Conrad and Leonard Lester arrived in town, Geoffrey Haywood chanced to be looking from the door of his store across the street at the hotel just as the hack drove up. He saw at once that the cousins were strangers, and that they were rather distinguished-looking.

Consequently he put on his hat and walked slowly over to the hotel, at his even, cat-like pace. No unnecessary noise did he ever make; his boots never creaked, and his cane never thumped the sidewalk or floor.

He saw on the young men’s trunk the initials “L. L.,” and “C. C.,” and read on the hotel register the names, “Carlos Conrad” and “Leonard Lester.”

The only evidence of surprise which he gave was a half-whistle, which he suppressed almost as soon as it escaped him. He immediately returned to his store and shut himself up in his private office. There he sat down and reflected as follows:

“What can this mean? Carlos is the son of old Anthony, and the colonel hates him worse than death. It can’t be that they’ve become reconciled. That would be impossible. The game was played too well and has gone on smoothly too long for that. But what can his son be doing here? and his cousin with him, too!”

Mr. Haywood’s manner, now that he was unobserved, lost something of its calm and unruffled exterior. He got up and paced the room, evidently much disturbed in mind.

“By Heaven!” he thought, “I must find out the object of this visit. There is too much at stake to be off guard a moment. If the old man should find out the part I took in his quarrel with his brother, I would in all likelihood be disturbed in my present snug berth. That cannot be the object of Carlos, though. The colonel will never see him. He will not speak to him when he finds out that he is Anthony’s son. Ha, ha! my young boy, if you have come here expecting to win favor from Colonel Conrad, you are most grandly mistaken. I can give you that information without your taking the trouble to walk out to his house. I’ll watch you.”

The next day he observed, of course, that the two cousins called at Elm Grove, and it was with a feeling of almost terror that he noticed that they did not return for more than two hours. So disturbed with conjectures and suspicions was he that he resolved to call on Colonel Conrad at once, to satisfy the burning curiosity that tortured him.

Accordingly, in the afternoon, he set out for Elm Grove, not hurrying in the least, although so tumultuous were the feelings that raged within his breast that he would have run at the top of his speed had he acted on his natural impulse. But to act on impulse was not part of Geoffrey Haywood’s life. His policy was to be always calm, self-possessed, and unapproachable, except so far as he chose to be approached. Consequently he walked with his usual stately gait, and when he presented himself at the door of Colonel Conrad’s mansion, his manner betrayed naught but complacency and a kind of obtrusive quietness.

To the servant who answered his ring, he said:

“Ah, Barker, good afternoon. Is your master in?”

Barker said he would see, and in a few moments returned with the intelligence that his master was indisposed, and could see no one.

“Go and tell him that it’s I, Barker,” said Haywood, with some loftiness.

Barker departed again, and again returned.

“He sent me out of his room and locked the door, sir, and said as how not to disturb him no more.”

“What—ahem—are you sure you understood him aright, Barker?”

“Yes, sir, sure,” said Barker, smiling, as he thought of the very emphatic manner in which the speech had been given, which he had repeated in a somewhat modified form to Haywood.

“Is Miss Florence in?” asked the merchant.

“No, sir, she left early this morning for a visit to the Cummingses.”

Haywood stood and reflected a moment. Then he said to Barker, who had turned to depart:

“Well—ah—Barker, wait a moment. Did two young men visit your master this morning?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Could you tell me their names?”

“Well, not knowing ’em, I couldn’t.”

“Did he see them?”

“Yes, sir, they were in his room with him more’n an hour.”

“Ah! You don’t know what their business was, of course? That is, you didn’t happen to overhear any of their conversation?”

“No, sir, only at first there was some pretty loud words passed between them, and afterward there was a good deal of talking in an ordinary tone.”

“Yes. Well it’s nothing in particular to me. I thought possibly they might be a couple of friends of mine whom I expect to visit me. And, by the way, Barker, you needn’t say anything about what I’ve been asking you. Here’s a dollar. I’ve been intending to make you a present for a long time.”

Barker stared in astonishment, for it was the first instance of liberality he had ever witnessed on the part of Mr. Haywood. He stood speechless while that august personage moved slowly down the path and into the street.

“A little tight!” was the laconic comment as he pocketed the dollar.

Haywood walked to his store, and entered in silent meditation, almost forgetting the stereotyped glance which he was wont to cast around at his clerks, seeming to say to them:

“I suspect you—every one of you. It’s useless for you to attempt to evade my scrutiny. It would be worse than folly for you to try to deceive me.”

This was with no appearance of inquisitiveness, but with a calm assertion of omniscience into their every thought and action as connected with his business.

No one ever knew how long he remained in his private office that night—how he pondered and sat in a brown study for hour after hour. If his rascality were to be exposed now—if Colonel Conrad should cast him off—what would become of him? Years before he had risked reputation, honor, everything, to get on the right side of his uncle, and become a partaker of the benefits of his wealth. He had succeeded. Anthony and William Conrad were taught to hate each other, and Haywood made the latter believe that he was his best friend.

William Conrad had been a colonel in the Mexican war, and during his military career had made acquaintances who subsequently induced him to invest a large portion of his means in gold mines. The investment was a profitable one, and brought him a large annual income.

And now, Haywood, who had acquired wealth and position through the aid of Colonel Conrad, was greatly disturbed at the visit of Leonard and Carlos. It suggested to his mind complete disgrace and utter ruin.

Besides, his uncle’s refusal did not add to his comfort. All in all, he was in a terribly perplexed and apprehensive state of mind. He determined to call again at Elm Grove the next morning, and, accordingly, on the following morning presented himself at the door.

“Oh, good-morning, Miss Florence. Is my uncle in?”

“Yes, Mr. Haywood, he is in, but I doubt whether he is disengaged at present. He has been very busy yesterday and to-day.”

“Indeed! But I think he will see me. I wish to talk with him for a moment on a matter of business.”

“I will ask him,” said the girl, “although he has given me strict orders not to be disturbed. Will you walk into the parlor in the meantime?”

He signified his assent, and she led the way. He stopped on the threshold for an instant in surprise, as he saw two young men in the room.

“Mr. Haywood,” said Florence, “permit me to introduce you to Mr. Carlos Conrad. This is Mr. Lester. Please excuse me for a moment.”

And she gracefully retired from the room, leaving the gentlemen to make the acquaintance of and entertain each other.

It was an awkward meeting. Haywood, for once in his life, was lost for something to say. Carlos eyed him steadily, and betrayed agitation. Leonard endeavored to open a conversation.

“We are on a visit to Dalton,” he said, “and called this morning to see our uncle, but he is indisposed, and we are forced to forego the pleasure of an interview with him.”

“Ah!” was Mr. Haywood’s sole comment.

“Yes, but we have had the pleasure of spending a few moments with the very lovely girl who just left us. I judge that you are acquainted with her. May I ask whether she is a relative of Colonel Conrad?”

“She is an adopted daughter of Colonel Conrad, who, as you doubtless know, never had any children. Her name is Florence Darley.”

“She has a beautiful face,” said Leonard.

“Yes,” said Haywood, showing three of his teeth, “everybody admires her beauty.”

At this moment the object of their conversation returned. She said:

“Colonel Conrad will see you for a moment, Mr. Haywood.”

Haywood rose from his seat, cast a barely perceptible look of triumph at the two young men, and left the parlor. He proceeded directly to his uncle’s room, and knocked. He was bade to enter.

He opened the door, expecting to see Colonel Conrad stretched out on a couch, with his dressing-gown on, a bottle of medicine by his side, and other indications of illness. But instead, there was the old man seated upright in his chair, with papers and writing material before him, staring at his visitor with an irritated expression, and looking the very reverse of weak.

“Ahem! Uncle Conrad,” began Haywood, “I called yester to see you, but――”

“Yes, I know you did,” replied the colonel, curtly. “You say you wish to see me on a matter of business. What is it?”

“Yes, it was a small matter, and not of so very much consequence. Yesterday, when you sent word that you were ill, I was quite troubled about you. So I thought I would step up this morning――”

“Oh, then you haven’t any particular business with me. I’m perfectly well now, if that is all you want; never was in better health.”

Haywood’s thick beard concealed the flush of vexation that arose to his face. It was something new for him to meet with such a reception. But he had for a long time exercised a certain control over his uncle, and he could not give it up without a struggle. So he did not take the hint that his presence was no longer desired, but still lingered, and said:

“Two nephews of yours are in town. I was surprised at your receiving the son of――”

“What is it to you, sir?” asked the old man, in wrath. “My brother is dead. Our love or hate can no longer affect him. And if I choose to see his son, I suppose it is my right, is it not?”

“Oh, certainly. And your brother is dead, is he? Dear me, how sudden! Well, it quite overcomes me. Ahem! Very sad that he should have departed without making restitution. But I was going to ask you if you could accommodate with a thousand dollars this morning.”

“No, nor a thousand cents. But stay—I expect a dividend to-morrow or next day from California, and then I may let you have it. Good-morning.”

This was delivered in a very emphatic tone, and left no pretext for hesitation. So, with outward serenity but inward vexation, Haywood left the room. He did not enter the parlor again, being in no mood to converse with those who had caused him so much disturbance of mind. He passed silently through the hall, a little faster than his usual pace, and was soon on his way back to the store.

No one but himself knew the terrible agony of suspense and fear that agitated his darkened soul.

Carlos Conrad and Leonard Lester remained for a few moments after Haywood’s departure in conversation with Florence Darley. As their remarks were commonplace, we will take this opportunity to give a brief sketch of the young lady.

She was an orphan whom Colonel Conrad had adopted ten years before the opening of our story. He had educated her, lavished on her all the tender love and care of a heart that had no other object on which to bestow its affections, and made her all that a daughter could be to him. She had paid him by tender devotion and a deep regard.

In person she was a beautiful girl. She was neither tall nor short, but her form was one of rare symmetry in its proportions, being rather slim, but round and full in development. The principal attraction of her face was not the regularity of its features, but rather the soul which looked out of the beaming eyes, and the atmosphere of light which seemed to be cast around her. Every one felt the gentle influence of her presence, and her manner was charming, oftentimes even unto fascination.

Carlos Conrad felt this, and he gazed at her in such a spell as he had never known before, even when associated with the dark Spanish beauties among whom he had been thrown. He could scarcely utter a word, so deep were the feelings stirred within him as he gazed on the lovely Florence.

Leonard noticed this, and a half smile played about the corners of his mouth, while Florence must have observed it, for a slight blush rose to her cheeks.

But the young men did not linger long. They felt that their presence beneath that roof was out of place for the present—that they should forego intruding on their uncle’s hospitality until the issue of their visit of the preceding day was made known.

So after a short time they rose and announced their intention of departing, bidding Florence Darley good-day. They left the house and made their way toward the village. Carlos was taciturn, and spoke to his cousin only in monosyllables. His mind seemed to remain at Elm Grove, even though his footsteps carried him from it.

“So soon, eh?” laughed Leonard, gazing around into his face.

“What do you mean?” asked Carlos, starting.

“Why, you haven’t seen her half an hour yet.”

“Pshaw!” exclaimed Carlos.

He made no further reply, nor could his cousin induce him to enter into conversation during their entire walk to the hotel. Little did Leonard care for this. He whistled merrily, and walked along in undisturbed spirits.

When they arrived at the hotel he asked the clerk if there were no sources of amusement in Dalton—it was insufferably dull.

“Well,” replied the clerk, “you can play billiards, or you can hire a horse or buggy and drive to Rocky Beach, some four miles off, where there’s splendid fishing.”

“Just the thing!” exclaimed Leonard. “I’ll go off and make the arrangements at once.” He turned around to speak to Carlos, but he had disappeared. “I won’t wait for him,” thought Leonard, “he’ll be ready enough to go after I have made arrangements.”

And straightway he proceeded to a livery stable to engage a horse.

Carlos, meantime, had strolled down the street, and stepped into a news-room. Here he picked up a daily paper, and read an announcement of a concert by a celebrated artiste, to take place in a neighboring town that evening.

He was a passionate lover of music, and had studied the art himself. Here was an opportunity he had long wished for, and he determined to embrace it.

Briefly, then, Leonard Lester set off in one direction, on a fishing excursion, and Carlos Conrad in another, to hear the celebrated Madame P―― sing.

Now, if both could have foreseen what was to take place within the next twenty-four hours, they would probably have materially changed their course; for a great tragedy was about to be enacted—the whole village was to be thrilled through and through with excitement.

The road which Carlos took was the same which led to Elm Grove; so that, in making his journey, he was obliged to pass the residence of his uncle.

Carlos drove swiftly along until he came near Elm Grove, when he brought his horse to a walk. He noticed an express-wagon in front of the gate, and two men carrying a small but heavy box in between them. He looked curiously at this, and the driver of the wagon, who remained on his seat, holding the horse said:

“Prob’ly you don’t know what’s in that box, bein’ a stranger in town?”

“No,” answered Carlos; “I certainly do not know what it contains.”

“Ha, ha! Thought so. Well, I’ll tell you. It’s gold.”

“Gold!”

“Yes. Colonel Conrad owns a mine out West, and about three times a year they send him a box full of gold. You saw, didn’t you, how strong the box was ironed together?”

“Yes, I noticed it.”

“There’s about thirty thousand dollars in it, I’m told.”

“Indeed!” laughed Carlos. “That’s more than one man deserves, I should think.”

And he whipped up his horse to a brisk trot, as he had by this time passed the expressman, and could only talk to him by dint of shouting.

We will pass by the visit of Carlos to Knoxtown, which was his destination, the concert, his enthusiastic admiration of the singer, and the general excitement of applause.

At a late hour in the night he set out on his return. It was starlight, and the air was sultry. He gave himself up to deep thought. What to conclude in regard to his uncle he knew not. He had been agreeably surprised at the reception he had received, for he had expected a storm of reproaches and immediate dismissal.

However, the fact that his uncle had since refused to see him, and at the same time had admitted Haywood, their common enemy, into his own private room, filled him with misgiving. Had he told Haywood the story, and shown the documents to him, so as to give him a chance to explain it all away? If the artful intriguer and mischief-maker were thus early to be allowed the opportunity to justify his conduct, and speciously smooth over his wrong-doing, then indeed had Carlos’ journey been in vain. Thus he thought, and his reflections made him gloomy as he sped on the road to Dalton.

It was past twelve o’clock when he came in sight of his uncle’s residence. It was but natural that he should drive more slowly, and look at the house and grounds.

He approached from the north side. Everything was quiet and gloomy. The air was still and clear, with not a breath of wind stirring. Silence reigned, broken only by the stepping of the horse, and the creaking of the wheels on the ground.

As he passed the house, and looked back at the south side, Carlos gave an involuntary start at seeing one room brilliantly lighted. This was so unexpected, and seemed so out of keeping with the general solitude, that he pulled up his horse and stopped.

He turned around in his seat, and regarded intently the window from which came the light. A careful scrutiny and calculation enabled him to conclude that the room must be his uncle’s study. It was on the ground floor, and, as near as he could judge, in that portion of the house to which he and Leonard had been conducted on their first interview with Colonel Conrad.

What could he be doing at that late hour? Surely, all the rest of the household were abed; and if Colonel Conrad were indisposed, it was, to say the least, curious that he should be occupied reading or studying at that hour. Perhaps he was so ill as to be unable to leave the room or summon assistance.

Suddenly Carlos discovered a dark form hovering stealthily in the shrubbery near the window. This sight decided him. He leaped from the buggy, tied his horse to a stump on the side of the road, and proceeded cautiously toward his uncle’s house.

Slowly he went, climbing over the fence, and making as little noise as possible. He avoided the gravel paths, but kept on the green lawn, which was velvet-like in its softness.

He arrived by the clump of rose-bushes, and thought he heard a rustling among them. He stopped and listened, holding his breath that no sound might escape his ear. Nothing was discernible to break the silence, however, and he resumed his way toward the house.

Finally he stood on the greensward, about a rod from the window he sought. The light was shining brightly still. But another circumstance increased the surprise of Carlos. The window was a long one, extending to the floor, and protected on the outside by blinds.

The blinds were open, and the lower sash of the window was raised.

He again stopped and listened, but still could hear no sound. He crept slowly up to the window and looked in.

There sat Colonel Conrad by the table, his head bowed over on it, motionless, and apparently asleep. The lamp stood beside him, burning brightly.

Carlos looked earnestly in at the figure of his uncle, debating what step to take next. Should he speak or depart, silently as he had come, leaving him to awake at his leisure?

But even as he looked something sent a choking, sickening sensation through him. He gasped for breath, and nearly fainted away, as he saw on the floor beside his uncle a dark-red pool.

It lay there, a glistening, horrible, fascinating puddle. Carlos stood rooted to the spot, for the moment thrown into a dumb, helpless lethargy. But the spell passed from him, and he suddenly roused himself into action.

He sprang into the room, approached his uncle, and touched his shoulder. The figure moved not. Carlos shivered from head to foot. Then he looked about him furtively. He stepped around to the other side of the motionless form, and saw in the neck a bloody wound, as if from a single vigorous deep thrust of a dagger. All this was so sudden and so awful that he could not realize its horror for the time being.

HE STEPPED AROUND TO THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOTIONLESS FORM.

Again he walked around to the other side of the table. The face of the dead body was bent over, out of sight; one arm was extended out straight, and the other was bent and the fingers clutched tightly together. Carlos could see that within this hand was a fragment of white paper. He seized hold of the fingers, not yet cold and stiff, and unclasped them. The paper was crumpled and wrinkled from the tightness with which it had been grasped. Carlos straightened it out, pulled it smooth, and examined it. It was irregular in shape, with two edges smooth and the other rough and jagged, as if it had been torn from a sheet. On it were two words, in the colonel’s handwriting. The paper and the writing were as follows:

On the table was an envelope, addressed as follows:

“TIMOTHY TIBBS, Esq.,

“Att’y,

“Dalton.”

Carlos merely glanced at the envelope, and then his gaze immediately returned to the piece of paper he held in his hand.

“Seven o’clock,” he repeated, and uttered the words over and over again in a low, husky voice. “Good Heaven! how horrible!”

But in the midst of it all he was calm enough to reflect.

“This paper,” he thought, “is a fragment of something my uncle was writing. Where is the other part?”

And he looked on the table and on the floor. His search was fruitless.

But again the pool of blood met his eye, and again the sickly, deathly feeling passed over him.

“Murdered!” he exclaimed, “in the night! Ah, who could have done it?”

At that instant he heard a sound without—it was unmistakable this time—and then he suddenly realized his position. What if he were discovered there at that hour, alone with that dead body, which had so recently been living, acting, moving? There could be but one conclusion. He would be accused of being a murderer.

Horrified at the thought, he leaped from the window, only to be met by the stalwart figure of a man, large in stature, and threatening in aspect, bearing in his hand a long, gleaming knife. He had on a black mask, and was advancing slowly, his hand raised as if to strike at an instant’s warning.

Carlos stopped in terror, regarding the mysterious figure in silence, and awaiting its onslaught.

A conflict seemed inevitable, and, gazing for an instant heavenward, he prayed for strength. Then, with sudden resolve, he stood erect, and braced his nerves for whatever might follow.

Carlos and the stranger paused, regarding each other with the quick calculation of antagonists measuring their opponents’ strength.

“You killed my uncle,” said Carlos, in a low tone.

“Your uncle! No—you killed him!”

“I?”

“Yes; you’re the only one that’s been here to-night. Nobody has seen me in or near Dalton.”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s lucky that you did happen along here, for I think I can fasten the deed on you. Stop! Don’t move nor speak aloud.”

Carlos had started to leave the spot, but the long knife was presented at his breast in a manner that threatened instant death if he stirred.

“Great Heaven! who are you and why did you kill him?”

“Silence!” was the reply, given in a fierce whisper, and accompanied by a terrible oath. “Don’t repeat that. I say you killed him. And here’s the evidence of it.”

He wiped the dagger, which was still bloody, on Carlos’ coat and vest, leaving great red stains.

“What is that for?” asked Carlos.

“You’ll find out when the spots are discovered. They’ll be pretty bad evidence against you. Ha! that makes you wince. But there is one thing more. I have been watching you, and I want that piece of paper you took from the old man’s hand. Fork it over.”

“What do you want of it?” asked Carlos.

“It belongs to this letter, and the letter is useless without it,” said the man, drawing a white paper partially from his pocket. “Come, give it up, and we will both leave this place quietly.”

But Carlos, seeing that the villain was off his guard for an instant, darted forward with the quickness of lightning and dealt him a powerful blow between the eyes.

The effect might have been serious had not the man been protected by his mask. As it was, it blinded him for a moment, and caused him to drop his dagger.

Carlos stooped to pick it up, but his antagonist recovered quicker than he had expected. He felt a blow on the side of the head that sent him reeling for a distance of two or three yards, and then he fell to the ground. The man was after him, but he was on his feet in an instant, and the two closed.

The man was large, and possessed great muscular strength. Carlos though smaller in stature, had well-developed muscles, and was, moreover, lithe and active. His antagonist soon discovered this, and found that his work was not so easy as he had anticipated.

They struggled and rolled over on the grass, each striving to obtain an advantage over the other. They seemed to be equally matched. But Carlos soon saw that in endurance he would fail. He felt his strength departing from him while the ruffian seemed to be fresh and unwearied. He must end the fight soon, or be beaten.

These thoughts passed rapidly through his mind, and at that instant he saw his opportunity. He suddenly ceased his efforts, and relaxed his struggles, throwing his antagonist off guard for a moment. Then he doubled up quickly, bringing his knees to his breast, and letting his heels fly out violently against his adversary’s stomach.

This mode of proceeding was entirely unexpected. The villain rolled over and uttered a deep grunt.

Carlos was free. He sprang to his feet and fled. He was instantly pursued, however, and if he had not been fleet of foot, would have been overtaken. He ran to the fence, cleared it with a bound, and then went directly to his horse and buggy.

He was almost to the carriage, the ruffian in hot pursuit. He saw that he would not have time to untie the horse, and so, running, he took out his pocket knife and opened the blade. When he came up to the horse he cut the halter, leaving it dangling to the stump.

Then he sprang into the buggy, applied the whip vigorously, and drove rapidly down the road.

Near by was a clump of trees, in the shade of which he saw a horse standing, saddled. Wondering at this, he still drove on, but looked back.

When on the brow of a little hillock he saw his pursuer stop and untie the horse.

“Ha!” thought Carlos, “he is coming after me on horseback. His horse may be fleeter than mine, and in that case he’ll surely overtake me. Ah, here’s a chance to circumvent him!”

He had come to a narrow street branching off from the main road, and into this he turned. As he was about a quarter of a mile ahead, and it was rapidly growing cloudy, he could neither be seen nor heard.

He urged his horse to a quicker rate of speed, and flew along the road blindly, recklessly. At first he passed farm dwellings frequently, and in one or two of them dim lights were burning. Dogs ran out to the gates and barked as he sped by, alarmed at the unusual noise. Again and again he lashed his horse, until the beast was covered with foam.

It now began to grow dark rapidly. Clouds shut out the stars from view, and thunder rumbled in the heavens, mingled with flashes of lightning. Then the rain began to fall in large drops.

Carlos was in a state bordering on delirium. The shock of coming so unexpectedly on the murdered body of his uncle would have been too much for the nerves of a much stronger man than he. The threat of the murderer of fastening the crime on him had filled him with apprehension. Then came the struggle, the pursuit, and the escape; all these following one another, produced on him a terrible state of excitement.

Not until he had driven four or five miles did he once halt or slacken his speed, or reflect that he was beyond the reach of his pursuer. By that time the rain was falling in torrents, loud peals of thunder rent the air, and vivid flashes of lightning came in quick succession.

The rain falling on his heated brow had the effect of cooling his excitement somewhat, and he began to reflect. He stopped urging his horse, and the poor beast dropped into a walk, enjoying the shower falling on his steaming flanks.

Carlos endeavored to look around him, but it was pitch-dark. Where was he? How far from Dalton? How near any human habitation? He knew not. Then he thought:

“Why this flight? I am guilty of nothing. My pursuer is off my track. I should be pursuing him, not he me. Where has he gone? Why did he kill my uncle?” Carlos shuddered as he thought of the body leaning over the table, and the pool of blood on the floor. “I must quickly return to Dalton, or in truth I may be suspected. The villain wiped his dagger on my coat, but I apprehend the rain has washed it all off. Besides, I could have no motive, and nobody saw me near the house. I must arouse the officers, and the murderer must be found.”

Alas! that these thoughts had come so late!

He then stopped the horse and began to consider the best mode of proceeding. He was in a lonely, unknown road, and finally decided to let the horse take his own course. So, dropping the lines, he commanded him to go forward.

The animal obeyed, stepping slowly and cautiously, his feet splashing and sinking deep in the mud at every step, and drawing out with difficulty.

The rain now was falling with less violence, and the thunder and lightning were not so frequent. Carlos was wet through to the skin, and the water ran from each side of his horse in little streams. Both animal and man were chilled and shivering. They plodded on slowly through the darkness, which was so dense as to seem almost like a material substance. Carlos gave himself up to a gloomy despondency, for, although innocent, he had a foreboding that the events of the night would bring evil and misfortune to him.

Suddenly the horse altered his course and turned quickly to the right. As he proceeded, the hub of one of the buggy wheels came in contact with some object—not with such force, however, as to stop the vehicle; and in a moment Carlos no longer felt the rain beating down upon him, but heard it over him, striking some intervening object. They were under a shelter. The horse had turned into a farm-yard and walked under a shed. He stood still, evidently determined to postpone the remainder of his journey until an improvement in the weather should take place.

This was a new and vexatious phase of affairs, and Carlos was confronted with the prospect of remaining in his strange quarters until daybreak.

He had not, up to this moment, heard a sniffing, smelling noise, which came from a large watch-dog, who had been walking around the buggy silently and regarding the new arrival with suspicion. The darkness had prevented him from seeing and the rain from hearing the animal. But now, as he was about to step from the buggy to tie the horse and make things secure for the night, a low growling arrested him. He stopped and listened, and knew that a large dog was in close proximity.

He leaped to the ground notwithstanding, and instantly the growls deepened and a shaggy body sprang against his breast. The dog had aimed for his throat, but seized his coat-collar instead.

Carlos did not lose his presence of mind, but seized the brute suddenly around the lower jaw, holding it with a vise-like grip. There was all the energy of a life-struggle in his grasp, and so tightly was his jaw held that the dog could not bring his teeth together. He was a large, heavy animal, and he bore Carlos to the ground. There they lay, and struggled and floundered, the dog uttering howls of rage, but Carlos never once relinquished his grasp.

The noise aroused the inmates of the house, which was near by. Soon a voice was heard:

“Tige! Tige! what’s the matter out there?”

It was a man who spoke.

“Help! for God’s sake!” cried Carlos.

“Who are you?” asked the voice.

“Call the dog off!” cried Carlos. “My strength is nearly gone!”

The man advanced, carrying a lantern, and peering cautiously ahead of him. He seemed in no hurry to relieve Carlos from his unpleasant position, but looked around as if to assure himself that no one else was about. Having become satisfied on this point, he exclaimed:

“There, Tige, get off. Get off, I say!” giving him a savage kick in the side.

Carlos let go his hold, and the dog, giving a short yelp, ran under the buggy, and seated himself on his haunches, glaring out at them with hungry eyes.

Carlos sank back on the ground and fainted.

“Well, who be you, anyhow?” asked the man.

Receiving no reply, he bent over the prostrate body, and, seeing that it was unconscious, he said:

“I’ll call Kit. Here—go into the house, you hound!”

The dog slunk on ahead of his master, peering backward, first one side, and then the other, with wicked eyes. On arriving at the door, the man roared:

“Kit! Oh, here you are. I should have thought the infernal noise would ha’ ’woke you.”

“It did,” responded a female voice. “What is the matter?”

“A young chap’s out here on the ground that has had a tussle with Tige. He’s gone clear away, and we’ll have to bring him in, I s’pose?”

“Oh, yes! It’s a dreadful night. You carry him in, and I will get some lights and make a place for him.”

Carlos was soon deposited on a couch, with a rough man staring at him, and a young girl, not so rough, endeavoring to restore him.

The man was tall and dark, with a shaggy beard covering nearly his whole face, and heavy eyebrows, overhanging a pair of deep-set, small, restless-looking eyes. He was large as well as tall, and his build betokened great strength. His position was not erect, but his gait was slouching, his look sullen, and his manner that of one at odds with all the world.

The daughter was also large of frame, but she did not share the devil-may-care look of her father. To be sure there was danger in those black eyes when her nature was once aroused, but there was the woman in them—womanly care, womanly softness, womanly passion.

As she bent over the form of Carlos, she overflowed with pity, and used gentle means to restore him.

And when her efforts were rewarded with success she stared at him eagerly, with a loud beating heart, and tears just ready to fall. Then for the first time her hand trembled and her steadiness of nerve forsook her.

Carlos slowly opened his eyes, pressed his hands to his forehead for a moment, and then looked his thanks at the being whose hands were deftly making him comfortable. Beneath his gaze she trembled violently and blushed a deep red. Her face was half averted, and she could find neither words nor voice to express her joy.

Her father saw that Carlos was returning to consciousness, and, going to a chair on the opposite side of the room, said, gruffly, as he sat down:

“He’ll do well enough now.”

At that Carlos sprang up suddenly, saying:

“Yes, I’m all right, and I must go. How far is it to Dalton?”

“Oh, sir,” said the girl, finding her voice, “you must not go to-night. You can’t.”

“Yes, I must,” said Carlos. “Can you tell me how far it is to Dalton?”

“A matter o’ four mile,” replied the man.

“Yes, it’s four miles, and it’s a bad road, with ever so many turns,” said the girl.

Carlos stepped to the door and looked out. It had nearly stopped raining, but the darkness was intense, and the water could be heard rushing in torrents in the ditch beside the road.

“If I only knew the way,” he said, straining his eyes in the vain endeavor to discern surrounding objects; “if I only knew the way, I would not hesitate a moment.”

“If you don’t know the way,” said the girl, “you couldn’t possibly find it. No, it wouldn’t do for you to try. You will have to stay with us until daylight.”

This seemed to be the only alternative, and Carlos reluctantly submitted. A fire was built for him to dry his clothes by, and the room was abandoned to his sole occupancy.

He was agitated, and bewailed the necessity of inaction.

“To remain away all night will make them suspect me,” he thought.

But he was exhausted, and, lying down on the couch, he sank into a troubled sleep. His dreams were disturbing, and he flung his arms and talked wildly as he slept.

Not till morning dawned and the sun was up did he awake. He sprang from the couch, and it took him some moments to recover full consciousness of his situation. Then with a groan he commenced dressing, and was soon in a presentable condition.

The father and daughter were already up, and in the next room had a breakfast prepared, although it was not yet six o’clock.

“We thought you ought to have something to eat before setting out,” said the girl, greeting him with a smile.

“I thank you very much,” replied Carlos. “I will take a cup of coffee, and then must be off.”

During the meal he inquired the names of his host and hostess. The man was Jake Heath, and the girl was his daughter Kate.

“Thank you,” said Carlos. “I will remember you, and repay you some time, if I ever have an opportunity.”

He shrank from offering money, as he instinctively felt that it would offend Kate. So, after again and again expressing his gratitude, he took leave of the two, shaking hands with them heartily.

Kate stood and watched him, a new light coming into her eyes, and a sigh escaping her, coming from the profoundest depths of her nature. The seeds of a hopeless passion had been planted in her heart.

Carlos’ thoughts were different. As he turned toward Dalton he was filled with terrible though vague apprehensions. Although he drove rapidly, he approached the village with fear and trembling, and felt that he was rushing into the jaws of death. And even at the early hour at which he entered the town, he saw that there was an unusual stir. The few that were out, instead of going quietly about their usual business, were talking with one another in excited tones, with sober looks and blanched faces.

Well did he know the terrible nature of their half-whispered words and low-spoken discussions.

The masked stranger tore through the shrubbery in mad pursuit after Carlos, uttering the most fearful imprecations.

He strained every nerve to increase his speed, and groaned in desperation as he saw Carlos jump into his buggy and drive off. He ran on to the spot where his horse was stationed, and, once mounted, there was a chance that he might overtake the object of his pursuit.

But Carlos drove rapidly, and, by the time the assassin was mounted, was out of sight.

The man applied the spurs and whip, and his horse galloped along swiftly, making the dirt and stones fly far behind him.

On they flew, swifter and swifter. Like an arrow they shot by the road where Carlos had turned. It was well that the latter adopted this ruse, or he would inevitably have been overtaken, for his pursuer’s horse was a fleet one.

Soon the rider began to grow uneasy.

“I should have come up with him by this time,” he thought. “There’s no horse in the Dalton livery-stable that mine ought not to have run down before this.”

He strained his eyes to look ahead, but the gathering clouds prevented him from discerning objects at any distance. Then he halted and listened. A faint rumbling of wheels greeted his ear, but it was not sufficiently distinct for him to determine from what direction it came. He concluded that it must be toward the village, and again lashed his horse and urged him ahead.

HE STRAINED HIS EYES TO LOOK AHEAD, BUT COULD NOT DISCERN OBJECTS AT ANY DISTANCE.

As he entered the streets of Dalton he began to feel a misgiving that he had been outwitted. But not a single chance must be cast aside, and he neither turned nor slackened his pace. Down the main thoroughfare, and around the corner of a street which led to the livery-stable, he proceeded, and there he saw a horse trotting briskly along, drawing a buggy containing a single occupant.

“Ha! my man,” he thought, “you’re too sure! You thought you were so far ahead that I couldn’t come up with you, but I’ll show you in a moment your mistake!”

Speaking a word to his horse, he dashed on with renewed speed, and was soon but a rod or two behind the buggy. He thought it strange that his approach was apparently not noticed, that there was no attempt to distance him, or avoid him in any way. He whom he supposed to be Carlos Conrad simply looked around once, and then drove on, neither slackening nor increasing his speed.

“Ah, I have it,” thought the pursuer. “He doesn’t know I have a horse. He didn’t see him under the shade of the trees. He thinks I am a mile off, and that some innocent cove is following him. I’ll tackle him now.”

Acting promptly on this theory, he galloped up to the side of the buggy supposed to contain Carlos.

The clouds by this time were quite thick, and rendered everything indistinct to the vision. The pursuer hailed his man:

“Hallo, stranger, hold on!”

The stranger looked around, and said:

“What do you want?”

His apparent unconcern startled the murderer, who, with a sudden impulse, leaped from his horse’s back into the buggy. The action was so quick as to meet with no repulse. The lines were jerked from the driver’s hands, his neck was encircled with a strong arm, and he was quickly chocked into submissiveness. The horse was reined in and stood still. The murderer’s horse, a well-trained animal, also halted and stood motionless.

“Now,” said the assailant, “if you’ll give up that piece of paper, I’ll let you go.”

“What do you mean?” gasped the victim, whose throat was firmly held.

“No fooling,” was the reply, given in an angry tone. “Just hand it over, or it will be the worse for you.”

“Hand what over?”

“The paper.”

“What paper?”

“You know as well as I,” was the reply, accompanied with a curse. “I saw you take it out of his hand.”

“I do not understand you.”

And the victim struggled to free himself. It was in vain. He was held in a vise-like grip.

“Are you not Colonel Conrad’s nephew?” asked the assailant, beginning to cherish doubts as to having hold of the right man.

“Yes, I am Colonel Conrad’s nephew,” was the reply.

“Then do as I wish, or you’ll be murdered, too.”

“I murdered, too! Please explain yourself. And I’ll thank you to give me a clear idea of what you want. If it is my watch, take it. I am helpless; and to have my throat in the embrace of your arm is far from comfortable. You can have my pocket-book, too, although there is precious little in it. At all events, I wish you would transact your business, whatever it is, and then release me.”

Further words were cut short by a blow on the head from a small bag of shot, and Leonard Lester sank back on the seat of the buggy unconscious. For it was he. He had started to return from his fishing excursion at Rocky Beach past midnight, and had arrived in Dalton just in time to fall in with the villain who was in pursuit of Carlos, and to be mistaken for his cousin.

When he first noticed the horseman approaching, he thought it rather strange that he should be out at such an hour, and, of course, did not suspect his object. And when he accosted him, and leaped into the buggy, and made the strange demand for that “piece of paper,” of course Leonard was bewildered. He dared not struggle violently, for the ruffian had him in such a manner that he could, by a contraction of his powerful arm, have easily broken or dislocated his neck. Consequently he was powerless to resist.

On the other hand, the murderer of Colonel Conrad did not dare risk a prolonged struggle in the public street, even at that late hour, to obtain the fragment of paper he so coveted. There was too much danger of making a noise and rousing the dwellers in the neighborhood.

So he adopted the expedient of rendering Leonard insensible for the time being.

By this time the rain-storm had come up. The thunder began to roar and the lightning flashed through the sky.

The ruffian bound Leonard’s hands, and then, lifting him up and placing him astride of his horse, he joined his feet by a cord, drawing it firmly and tying it securely. All this was effected with much trouble, as Leonard was helpless, and was by no means a light weight to handle.

His captor mounted behind him, and, placing his arms around him, held him in position, at the same time grasping the bridle with his hands.

“Now get up, Bill,” he said, “and take us home in short order.”

And he brought his heels violently against the sides of his horse. The animal sprang forward with a snort, and dashed through the streets of the town, amid the driving rain and deafening thunder. The horse and buggy used by Leonard were left behind to take care of themselves as best they might.

On drove the strange couple, one bewildered and confounded by his situation, and the other destined to be scarcely less so, for what would be his emotions on discovering that his prisoner was not the man he had pursued from the grounds of Colonel Conrad?

After a time Leonard returned to consciousness, the jolting ride and the drenching rain arousing his nerves into action. He attempted to struggle, but soon found that the effort was futile. He could move neither his hands nor his feet, and, as he only maintained an upright position by the aid of his companion, he conceived the idea that it would be policy to remain quiet.

On recovering from the effects of the blow he had received, he had immediately comprehended his situation, and was aware that he was being carried rapidly out of town for some purpose—though what he could not imagine.

“Where am I?” he asked; “and who are you?”

“Ah, you’re awake, awake, are you?” was the reply. “You’ll find out who I am soon enough. I’ll take you to a place where you’ll come to terms, I’ll be bound. If you had been reasonable, and given me what I wanted, you might have been abed and asleep by this time. Now I’m afraid it will go a little hard with you.”

“Oh, you’re still harping on that, are you?” said Leonard. “Well, I’ll give you all the pieces of paper I’ve got, if you will leave me one ten-dollar bill for present necessities.”

“Too late now; you ought to have made that offer when I first came up with you. You must go with me now, and I’m thinking you won’t come back in a hurry either.”

“Why? What do you mean?” asked Leonard, in some alarm.

“Oh, nothing, only it will be necessary to take you to a place that you probably never dreamt of; and if we should let you go, it might be the ruination of us.”

“If you should let me go! And don’t you mean to let me go?”

“We can tell better about that pretty soon. By the lightning, how it does pour down! Get up, Bill!”

For as much as half an hour longer they went on their lonely road, now through thick woods, now by open fields. At last the murmur of the sea was faintly heard. They were approaching the shore of the ocean.

Leonard kept a sharp lookout.

Their course was now over rough places and through jagged paths. Every moment the roar of the sea grew more distinct.

At length Leonard’s captor reined in the horse. He took a small instrument from his pocket, placed it to his mouth, and gave three long, shrill whistles.

After a moment’s pause, the signal was answered. Then they pushed forward again, and after riding a short distance, halted.

Leonard could just discern in the darkness a high mass of rocks near him, while the washing of the waves on the shore could be heard close at hand.

“Now,” said his captor, “I’m going to take you down from the horse, and you’ll have to walk a spell. But I warn you that there’ll be no use in your trying to escape—you can’t do it. So look sharp and mind your footing, and keep close to me.”

He took a knife and cut the cords that bound Leonard, for they were so swelled with the rain that it was impossible to untie them.

Leonard leaped to the ground, and stretched his limbs, for they were cramped and painful.

“Now walk ahead of me,” was the command, and the two proceeded forward, Leonard’s mind being active and on the alert for some means of escape from his strange custody.

They were walking parallel with the edge of the water, some rods distant from it.

Suddenly, Leonard turned abruptly to the right and fled. He rushed directly toward the murmuring waves, and stumbled across a small skiff.

A yell of warning followed him, but he leaped into the boat, seized the oars, and rowed rapidly from the shore.

The man reached the water’s edge just too late. With an exclamation of baffled rage, he fired two pistol shots.

Leonard rowed vigorously, and soon put quite a distance between himself and the shore. He hoped, in the darkness, to confuse and outwit his pursuer.

But all at once he heard a suspicious sound, and paused to listen.

It was the sound of oars.

The strokes were quick and strong, and were made by more than one pair of arms. They came from more than one direction, too.

The conviction flashed upon Leonard’s mind that other boats were at hand, and that he was pursued. He threw all his energy into his work, and rowed rapidly. Even as he did so, he was conscious that the odds were against him, but his spirits did not sink, nor did his efforts abate. Although the bow of the little skiff cut the waves gallantly, and shot a stream of seething foam out either side, she was rapidly gained upon. Soon Leonard could hear the strokes of the pursuing oars even while his own were in motion, and they gradually but surely grew more distinct.

Even when it became a certainty that he must be overtaken, he calmly awaited the course of events, not without fear, but still cool and self-possessed.

Leonard had scarcely left the shore two rods behind him when his pursuer reached the point where he had leaped into the boat.

Pausing a moment and retracing his steps, he ran to the base of a high cliff of rocks, and again blew his whistle.

“Ratter! Beattie! Hawkins! Out here, quick! There’s work to do.”

“Hi! Snags, what is it?” responded a voice apparently coming from the depths of the rock.

“I had a prisoner and he has flown. He is in a boat now, rowing for dear life.”

“In a boat! How in thunder did you come to let him get a boat? Who is he, anyhow?”

“Do not ask any questions, but be after him as quick as you can. He must not escape!”

“Well, I’ll call the boys.”

“Confound it, you should not have to call them. Why didn’t you get ready for action when you heard my first whistle?”

“Didn’t suppose there was going to be any trouble of this kind. You ought to have watched him more careful――”

“Well, well. Never mind that now. He is pulling away fast, and every moment is precious.”

“Yes, we’re coming. Can’t you tell a fellow what kind of a job it is, Snags?”

“No, not till I see Roake. I don’t know much about it myself yet. Only it’s life or death to get that chap that’s leaving us so fast.”

By this time four men had emerged from an aperture in the rocks, and were hastening to the shore.

“Take two boats, branch out, head him in—be sure that you catch him!” shouted Snags, and before he had fairly ceased speaking, the pursuers were pulling from the shore.

They rowed rapidly, and with a certainty and confidence that betokened an intimate knowledge of the locality.

Snags now turned toward the perpendicular ascent of rock and entered the aperture from which the men had emerged. He stepped into what was apparently a small fissure in the rocks, overhung by a projecting crag.

He proceeded for some distance through a dark passage, and then emerged into a large apartment, dimly lighted by a high, swinging lamp.

It was a cave, the walls of which on all sides were of dark-colored rock, rough and uneven, with moisture oozing out here and there. The ceiling was high, and from it was suspended by a wire the lamp, which cast a ghostly and uncertain glimmer about.

Going directly across the apartment, he came to an opening which branched off in the form of a long, narrow hall. This hall he traversed for some distance, and finally halted before an iron door, over which swung a small lamp.

He knocked. Receiving no answer, he knocked again, louder.

A volley of oaths greeted his ear, uttered in an angry tone.

Waiting until the storm had subsided, he said:

“Roake, let me in. It is I—Snags. Open the door.”

“What the duse is the matter?” uttered the voice, somewhat more mildly, but still with vexation in the tone.

“I’ll tell you when I’m alone with you.”

A rattling at the latch was now heard, and the iron door swung open heavily. It disclosed an apartment fifteen or twenty feet square, which, like the rooms through which Snags had already passed, was feebly illuminated.

On one side was a bed, and there were tables, chairs, a couch, and a cupboard, in different parts of the room. Everything bore an untidy, disorderly look.

As Snags entered, Roake said:

“I suppose everything worked all right—didn’t it?”

Instead of replying, Snags said, cautiously:

“I suppose the ‘Boss’ isn’t around, is he?”

“No, of course not. Why?”

“Nothing, only I’m afraid he wouldn’t be over and above pleased with what I’ve had to do to-night.”

“What have you had to do?” said the other, sharply.

“Well, you see,” said Snags, drawing a long breath, “I got up to the grove about twelve o’clock, and went to the window mentioned. There was a light in the room, and there sat the colonel, writing. I could just see this through a corner of the curtain, which was turned up a little. He wrote more’n an hour, and I out there waiting for him to get through. But he didn’t get through, and I was revolving in my mind a change of tactics, when he got up.