The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Writing of News, by Charles G. Ross

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Writing of News

A Handbook with Chapters on Newspaper Correspondence and Copy Reading

Author: Charles G. Ross

Release Date: June 22, 2019 [EBook #59791]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WRITING OF NEWS ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

THE

WRITING OF NEWS

A HANDBOOK

WITH CHAPTERS ON NEWSPAPER

CORRESPONDENCE AND COPY READING

BY

CHARLES G. ROSS

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF JOURNALISM IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Copyright, 1911,

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Published November, 1911

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

TO

MY MOTHER

In preparing this volume the author has had in mind the needs not only of students in schools of journalism, but of others who may desire a concise statement of the principles that govern the art of news writing as practiced by the American newspaper. It is hoped the book will prove helpful either as a laboratory guide in the school room or as a text book for home use.

As the title indicates, the book deals with one phase of journalism, the presentation of the news story, more especially with the writing of the story—the reporter’s part in the day’s work. No attempt has been made to go into other aspects of journalism—the writing of editorials, the administrative features of the work, the delicate adjustment that every newspaper must make between its business and news departments—except in so far as they bear directly upon the subject in hand.

The term journalism is broadly used here to mean all branches of newspaper endeavor. In common with other newspaper men, the author admitsvi an aversion to the word as restricted to the working field of the men who get and write the news. They call themselves not journalists, but reporters or newspaper men. It is for newspaper men and women in the making that the book is primarily designed.

The nature of newspaper work makes it impossible to formulate an all-sufficing series of rules by which the news writer shall invariably be guided. But there are certain well-defined principles, largely technical, that set apart the news story as a distinct form of composition, and these the author has tried to put down simply and concisely—after the fashion of the news story itself. Going beyond the common practice, there is wide divergence among newspapers in the details of “office style.” Methods peculiar to the individual paper can readily be acquired by one grounded in the essentials of the craft; hence only the more significant points of departure from the generally accepted practice have been noted.

Practically all the examples in the book are from published news stories, reproduced in most cases exactly as they appeared in print. In some, for obvious reasons, fictitious names and addresses have been substituted for the real. With one or two exceptionsvii the examples illustrating right methods of news presentation have been chosen not for special brilliancy, but as fairly showing the everyday output of the trained news writer.

University of Missouri,

Columbia,

July, 1911.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Newspaper Copy Terminology—Directions for Preparing Copy |

1 |

| II. | The English of the Newspapers Clearness—Conciseness—Force |

7 |

| III. | The Writer’s Viewpoint Fairness—Impersonality—Good Taste—Originality |

17 |

| IV. | The Importance of Accuracy In Observation—In Names—In Street Addresses—In Spelling |

30 |

| V. | News Values The Reporter—What Is News?—The Newspaper’s Problem—Kinds of Stories |

41 |

| VI. | Writing the Lead What the Lead Is—What the Lead Should Contain—Observance of Style—Leads to Be Avoided—Sentence Structure—Leads That Begin With Names—The General Rule—Study of 100 Typical Stories |

57 |

| VII. | The Story Proper Compression and Expansion—The Mechanics of the Story |

79 |

| VIII. | The Feature Story What the Feature Story Is Not—Stories for Entertainment—The Human-Interest Story—The Editor’s Problem—Sunday Magazine Stories |

98 |

| x IX. | The Interview When the Interview Is Incidental—When the Interview Is the Story |

113 |

| X. | Special Types of Stories Stories of Fires—Deaths—Weddings—Crimes—Business—Second-Day Stories—Rewriting |

129 |

| XI. | The Correspondent Writing for the Wire—Some Pitfalls to Be Avoided—What Not to Send—What to Send—Sporting News—How to Send—Handling the Big Story—Sending by Mail—General Instructions—Payment |

150 |

| XII. | Copy Reading Qualifications for the Work—Organization of Copy Readers—Editing the Story—Rules About Libel—The Guide Line—Marks Used in Editing—Additions and Insertions—The Lighter Side—The Copy Reader’s Schedule |

171 |

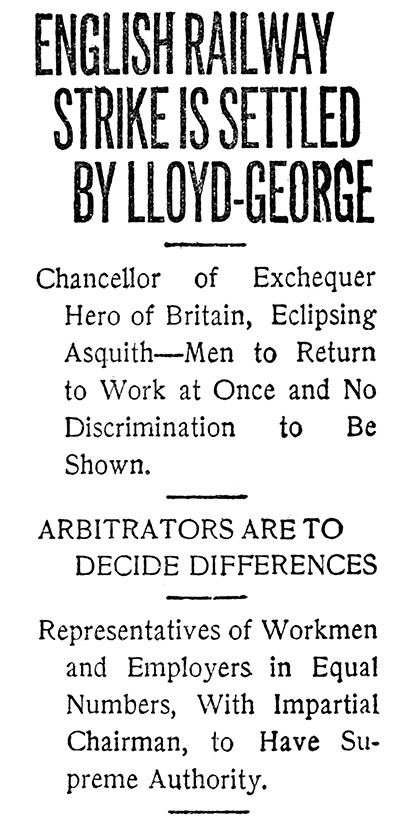

| XIII. | Writing the Head First Requisites of the Head—Definiteness—The Question of Tense—The Mechanics of the Head—Some Things to Avoid—Symmetry and Sense—Special Kinds of Heads—Capitalization |

193 |

| XIV. | Don’ts for the News Writer | 211 |

| XV. | Newspaper Bromides | 224 |

| Index | 231 |

THE WRITING OF NEWS

... But however great a gift, if news instinct as born were turned loose in any newspaper office in New York without the control of sound judgment bred by considerable experience and training, the results would be much more pleasing to the lawyers than to the editor. One of the chief difficulties in journalism now is to keep the news from running rampant over the restraints of accuracy and conscience. And if a “nose for news” is born in the cradle, does not the instinct, like other great qualities, need development by teaching, by training, by practical object-lessons illustrating the good and the bad, the right and the wrong, the popular and the unpopular, the things that succeed and the things that fail, and above all the things that deserve to succeed, and the things that do not—not the things only that make circulation for to-day, but the things that make character and influence and public confidence?—From an article by Joseph Pulitzer in the North American Review.

THE WRITING OF NEWS

This is the age of the reporter—the age of news, not views. We are influencing our public through the presentation of facts; and the gathering, the assembling and the presentation of these facts is the work of the reporter. There are two ideals of news. The first is to give the news colorless, the absolute truth. The second is to take the best attitude for the perpetuation of our democracy. The first would be all right if there were such a thing as absolute truth. When jesting Pilate asked, “What is truth?” he expressed the eternal question of modern journals. The best we can do is to follow the second ideal, which is to point out the truth as seen from the broadest, the most human and the most interesting point of view.—From an address by Will Irwin at the University of Missouri.

All manuscript for the press is copy. Clean copy is manuscript that requires little or no editing. The various steps in the gathering and writing of news that precede printing are indicated briefly in the following explanation of newspaper terms:

Story.—Any article prepared for a newspaper.2 A three-line item and a three-column account of a convention are both, in the newspaper sense, stories. The term is applied also to the happening with which the story deals. Thus a reporter sent to get the facts about a fire is said to be covering a fire story. A happening of unusual importance makes a big news story. Reporters are assigned or detailed by the city editor to cover certain stories, and the task given each is his assignment. A reporter assigned to visit certain definite places which are covered regularly in the search for news (as police stations, hospitals, courts, fire headquarters, city hall, etc.) is said to have a run or a beat. A reporter scoops competing news gatherers when he gets an exclusive story. The story is called a scoop or a beat.

Stickful.—A term frequently used in defining the length of a story. A stickful is about two inches of type—the amount held by a composing stick, a metal frame used by the printer in setting type by hand.

Lead.—Loosely used to indicate the introduction, usually the first paragraph, of the story. In the ordinary sense the news story has no such thing as an introduction. The lead goes straight to the point without preliminaries. Do not confuse this3 word, pronounced “leed,” with the word of the same spelling pronounced “led.” The latter word lead, as a verb, is an order to the printer to put thin strips of metal (leads) between the lines of the story in type, thus giving additional white space and making the story stand out more prominently on the printed page. Editorials are usually leaded.

Copy Reader.—A sub-editor who puts the copy into shape for the printer and writes the headlines. Sometimes called copy editor. Do not confuse copy reading with proofreading (the correction of proof sheets), which is done in another department.

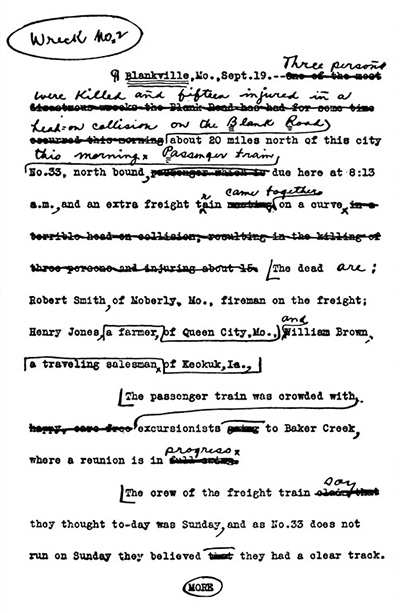

Slug.—A solid line of machine-set type. As used by the copy reader, the term usually means the identifying name given a story, as “wedding,” “fire,” “wreck.” A story is slugged when it is so named for convenience in keeping tab on it.

Head.—Abbreviation for headlines. A copy reader is said to build a head on a certain feature of the story.

Feature.—Noun: The most interesting part of a story is the feature. Verb: A story is featured or played up when it is prominently displayed. Adjective: A feature story usually depends for its4 interest on some other element than that of immediate news value.

Make up.—Verb: To arrange the type in forms for printing. Noun (make-up): The process of arranging the type or the result as seen in the printed page. A newspaper is said to have an effective make-up when the disposition of the stories on a page and the general typographical appearance of the whole contribute toward making the desired impression on the reader. The make-up editor supervises the work of making up. A page may be made over to insert late news.

Most newspapers insist on typewritten copy; all prefer it. It can be prepared more quickly than long-hand copy after one has mastered the use of the machine; it makes for accuracy; it is easier to edit, and, because of its uniform legibility, it saves time and expense in type-setting.

Adjust your typewriter to leave two or three spaces between lines, so that legible interlining in long-hand will be possible. Closely written copy is the abomination of the copy reader, compelling him to cut and paste in order to make corrections.

5 Never write on both sides of the paper. Never fasten sheets of copy together.

Write your name in the upper left-hand corner of the first page. Number each page.

Begin the story about the middle of the first page, the space at the top being left for writing in the headlines.

Don’t crowd the page with writing. Leave a margin of an inch to an inch and a half at each side. Leave an inch at top and bottom for convenience in pasting sheets together.

Avoid dividing words. Never divide a word from one page to another.

In writing a story in short “takes,” or installments, make each page end with a sentence.

Indent for a paragraph about a third the width of the page.

In making corrections it is usually safer to cross out and rewrite. Be particularly careful about names and figures.

Letter inserted pages. For example, between pages 3 and 4, the inserted pages should be designated 3a, 3b, etc.

Use an end-mark to show the story has been completed. The figures 30 in a circle may be used.

Use every effort to make long-hand copy easily6 legible. Overscore n and o and underscore u and a when there is any possibility of confusion. Print proper names and unusual words. Draw a small circle around periods or use a small cross instead.

Draw a circle around an abbreviation to show it is to be spelled out. To make sure a letter will be set as a capital draw three lines under it.

If there is a chance that a word intentionally misspelled, as in dialect, will be changed by the printer or the proofreader, draw a circle around the word, run a line to the margin and there write “Follow copy.”

Unless you are pressed for time, read over your story carefully before turning it in.

Accuracy is the first essential of news writing. Above all, watch names.

Of the three generally recognized qualities of good style—clarity, force and grace—it is the last and the last alone in which critics of newspaper English find their material. It would be ludicrously superfluous to illustrate here the prevailing clearness of what one reads in the daily press. To it everything else is sacrificed. He who runs through the pages of his paper at a speed that keeps even pace with that of his car or train, and yet understands what he reads, without difficulty and without delay, would give short hearing to a complaint on this score. The same assertion may safely be made of the second of the trio of good qualities. Whenever and wherever force is needed, the reporter, no matter what his limitations of time and distracting circumstances, manages to put it into his writing.

The result is plain—and inevitable. Beauty, grace, suggestion of that final touch which confers upon its object the immortality of perfect art, are nearly always conspicuously absent. We know at a glance what has happened and we get the force of whatever significance the writer has wished to impress, but it is all hurled at our heads in the same wholesale fashion, with the same neglect of “form,” that the genuine American is accustomed to in his quick-lunch resort, and, in his heart, really likes. ... Without intending to be dogmatic about it, we are inclined to say that, if a newspaper’s English makes a fair approach to the level of an educated, intelligent man’s serious conversation, it will be doing about all that can justly be expected. Whatever it accomplishes more than this is to its credit.—From an editorial in the New York Evening Post.

8 “Newspaper English” has often been used as a term of reproach, as if the newspapers, by concerted action, had been guilty of creating an inferior, trademarked brand of English for their own purposes. The term has been hurled indiscriminately at all newspapers, the good as well as the bad, and young writers have been warned in a vague, general way to beware of the reporter’s style. As applied to loosely edited newspapers the criticism is just. It is not true, however, that “newspaper English” constitutes a special variety of language, to be shunned by all who would attain purity in writing. There are good books and bad books, just as there are good newspapers and bad newspapers, and it would be as reasonable to condemn all books because they are written in a “bookish” style as it is to include all news writing in a sweeping condemnation.

No defense is needed of the style of writing in the well-edited modern newspaper. Free from pedantry and obsolete expressions, the English of the best newspapers fulfills its purpose of telling the news of the day in language that all can understand. Newspaper English has not been created by the newspapers alone. It is the language of the people, clarified and simplified in the writing, as9 opposed to the language of an earlier day which obscured the writer’s thought in a maze of high-sounding words. Newspaper English, at its best, is nothing more nor less than good English employed in the setting forth of news. At its worst it embodies the common faults of writing.

The reporter writes his story for readers of all degrees of intelligence—for the man whose only reading is newspapers and for the man of cultivated taste. Simplicity is the keynote. This does not mean crudity or slovenliness, for while the good news story is written with the limitations of the least intelligent reader in mind, it should not offend the educated reader. In this respect the Bible, the simplest of all books, is an excellent model for the news writer.

In keeping with its essential simplicity of style, the good news story is clear, concise and forceful.

Simplicity of structure and diction implies clearness. The story that would appeal to the masses defeats its purpose if not readily intelligible. The average newspaper reader has neither time nor inclination to puzzle over an involved sentence or to10 consult a glossary for the definition of a technical phrase.

Scientific terms, if not in general use, should be translated into everyday English. This is true also of legal phraseology and other words and expressions of purely technical meaning. Let your story explain itself. If Mrs. Jones got a divorce, say so; don’t confuse the reader with the verbiage of the courts. Get as close to the speech of the people as good taste and correctness will allow. Vulgar and silly slang is not tolerated by the good newspaper, but an expressive colloquialism may be used to avoid pedantry.

In striving for simplicity and clarity beware of dullness. “Fine writing”—the kind that speaks of a barber shop as a “tonsorial parlor”—has no place in the modern newspaper office, but there is a demand for the writer who can infuse freshness and vigor into his story. The style of your story should be simple, its meaning clear and its diction pure. Try also to give it that element of originality and charm that distinguishes the best writing from merely good writing. Newspaper English, as used by skillful writers, displays often, in its well-turned phrases, its quick description and its “featuring” of the leading facts, the touch of the true11 artist. For all this the story is none the less, in the manner of its telling, simple and clear.

“Boil it down” is an injunction frequently heard in the newspaper office. The requirements both of the public and of the newspaper demand that the story be concisely told. The hurried reader has no time for the story clogged with unnecessary words and trivial detail; the newspaper has no space for it.

Daily there comes to the newspaper a stream of copy from various sources. The local room contributes its share, while the telegraph editor receives scores of dispatches from special correspondents, besides the regular service of one of the great news gathering organizations. It would be neither possible nor desirable to print all of the immense amount of news matter received. The paper as the reader sees it is the result of a process of careful selection. Many stories have been omitted, some of them having been “killed” after progressing as far as the type forms, and others have been “boiled down” to a few sentences.

The news writer, then, should study to be terse. Verbosity merely makes work for the copy reader’s12 pencil. Try to say in one word what the writer who strains after effect might put into half a dozen. Don’t say “devouring element” when you mean “fire.” “Fire” is a good Anglo-Saxon word that everybody understands and uses—and it is twelve letters shorter. “A house is building” is simpler, shorter and more effective than “A house is in process of construction.” “The society met last night and elected officers for the year” is the simple, natural equivalent of “At a meeting held last night the society perfected its organization for the year by the election of officers.”

Wordiness, like bad spelling, is a sign of mental laziness, and the newspaper office has no room for the lazy.

Force grows out of simplicity, clearness, terseness of style. The story told in plain, curt phrase is more effective than the story which shows a conscious striving after effect. Diction is important. A strong word lends strength to an entire sentence, while a weak word may spoil the vividness of an impression. As a rule the words that are deeply rooted in everyday speech are stronger than their synonyms of foreign origin. Words derived13 from the Anglo-Saxon are the bone and sinew of the language. The writer who neglects them for the longer and often more euphonious words from the Latin may add elegance to his style, but he takes away from its power to impress. The reader feels the difference, though he may not be able to explain it.

Brevity as well as force favors the Anglo-Saxon. “Begin” is shorter than “commence.” It is a better word for the news writer. Likewise it is better to say “A movement was begun” than “A movement was inaugurated.” The latter is a word in good standing—presidents are inaugurated—but let it be confined to its proper use. “Build” is preferable to “construct” when the words may be used interchangeably. Examples might be multiplied, but in the end the writer must rely on his own judgment of word-values, sharpened by a study of good writing.

This rule may be formulated: In seeking force, choose the Anglo-Saxon word instead of its foreign equivalent unless clearness demands the latter.

The active voice is usually more forcible than the passive. “Jones succeeds Smith” and “A house is building” are better news sentences for14 this reason than “Smith is succeeded by Jones” and “A house is being built.”

Short sentences, unless they become monotonous, are preferable to long. The speed with which stories are put together in the newspaper office, especially when the writer is working to “catch an edition,” is one factor that makes news writing forcible. Working under pressure, the reporter writes with a nervous, hurried energy that makes for short sentences and quick, telling phrases. He has no time for involved construction and prettiness of language. His aim is to “feature” the big facts of the story—to put what he calls a “punch” into the lead. What such a story lacks in elegance it makes up in force.

I.—A good news story, illustrating especially the virtue of conciseness:

CHICAGO, Nov. 5.—“It is hard to give away money,” declared James A. Patten, retired Board of Trade operator, at a Y. M. C. A. meeting last night at Evanston. “A person must acquire the habit,” he added. “After that it comes easy.”

Then he gave the Evanston association $25,000, with the condition that it raise an additional $75,000 within the next ten days. The meeting opened a campaign for raising a fund of $100,000.

15 (Note in the foregoing the effective use of direct quotation.)

II.—Simplicity of form and diction adds to the force of the following news dispatch:

LONDON, Nov. 5.—Dr. Hawley H. Crippen, convicted of the murder of his wife, Belle Elmore, the actress, to-day played his last card and lost. He will be hanged on November 8.

Changed as he was physically, Crippen maintained his composure even in the trying moment when he heard his doom pronounced. At once the Court’s decision was announced, a warden touched the prisoner on the shoulder and the latter, without a word or gesture, turned and left the dock. He was conducted at once to Pentonville Prison.

Those who have seen Crippen during his imprisonment say that his bearing has never changed from the moment of his arrest. He sleeps throughout the night soundly and eats heartily. He spends much time in reading. Miss Leneve has visited him in the prison three times.

(All the salient facts of the story are summed up in the opening paragraph. Note the use of metaphor—“played his last card and lost.” Touches such as this lift a story above the commonplace. Note, too, that no attempt is made at so-called “fine writing.”)

III.—Rewrite the following:

Within three hours after a “ten spot” had been deposited with Chief of Police William Smith as a reward16 to the patrolman arresting one Fred Wilson, charged with the larceny of a coat and a pair of shoes from J. W. Morris at a South street rooming house, said Fred Wilson was resting his tired body within the confines of the city bastile.

Morris left the reward and a description of the man who, he said, had taken the articles. Each policeman was given the description and told to look out for the man. It fell to Officer John Haden at the Frisco Depot to garner the loose change by collaring Wilson and taking him to headquarters. He had the shoes and coat in his possession at the time and told Haden that he had merely put them on to wear for a little while.

It is believed that he was preparing to leave Smithton for another haven when arrested.

(The foregoing is a sample of “fine writing.” Why not say $10 or “a ten-dollar bill” instead of “ten spot”? “Charged with stealing” is shorter and more to the point than the technical expression, “charged with the larceny of.” “Within the confines of the city bastile” evidently means “in the city jail.” Other violations of good news style will be apparent after a moment’s thought. When in doubt ask yourself: How would I say this if I were relating the incident in conversation? Then write it that way. Be natural.)

Newspaper work is an exacting profession, because things a journalist has done do not count. Like a hen he must lay an entirely new egg every day.—From an address by Arthur Brisbane at Columbia University, New York.

As many changes have come in recent years in country journalism as in any other line of human endeavor.... The pronoun “we” has been banished from the editorial and news columns, and the “slop” and “hog wash” known as “puffs”—that is, fulsome compliment and paid-for flattery—has become obsolete.—From an editorial in the Fulton (Mo.) Gazette.

The three notes of modern reporting are clarity, terseness, objectivity. The news writer of to-day aims to tell a story that shall be absolutely intelligible, even to minds below the average—since everybody reads; to economize space to the last degree, and to keep himself, his prejudices, preferences, opinions, out of the story altogether.—From an editorial in the St. Louis Republic.

The news writer is the agent of the paper that employs him. As such, in a wider sense he is the agent of the public, which relies on the newspaper to keep it informed of the day’s happenings. The story is the all-important thing; the reader as a rule cares nothing about who wrote it or what the writer thinks of it. The viewpoint of the news writer18 must be that of the unprejudiced, but alert, observer. He must approach his story with a mind open to the facts and he must record the facts unvarnished by his own preferences and opinions. Comment on the news of the day is the function of the editorial columns. It has no place in the news story. The writer who willfully injects his own likes and dislikes into the story breaks faith with his employer, whose space he is using, and with the public that buys the paper.

The ideal news story, apart from questions of style, has these qualities:

1. It is written without prejudice. It is fair, both in spirit and in detail.

2. It is written from an impersonal, objective viewpoint.

3. It is written in good taste.

4. It has originality.

In writing your story remember always that it will be read not merely by a circle of men and women of your own tastes and opinions, but by persons of all classes, of all races, of dozens of different shades of religious and political belief. The daily press is the popular university. Protestant,19 Catholic and Jew look to it for information; it sets the standard of English for the masses; for many it is the only reading. The tremendous influence of the press imposes an obligation on the news writer. His story must be simple and direct, so that all can understand; more important still, it must be fair.

Approach every story in a spirit of open-mindedness, remembering that nearly every question has two or more sides. Tell the facts and let the reader draw his own conclusions. Tell all the facts essential to a clear understanding of the story. A story may be true in detail and yet work an injustice by omission. Let your story be fair in detail and in the impression it leaves.

Even aside from the ethical obligation, business reasons demand fairness. No paper can afford to offend a large group of readers by a slighting reference to a race or a religious sect. Call the races by their right names. Words such as “Dago” are forbidden by fairness, by good taste and by business policy.

Before making a damaging statement about a person, be sure you have legal evidence in which there is no loophole. Hesitate even then—go to the city editor for instruction. If you are a correspondent,20 let your office know the facts—all the facts. Bear in mind that homicide is not necessarily murder. There is grave danger, no matter how convincing the evidence may appear to be, in calling a person a murderer before he has been so branded by the courts. If he is acquitted he has ground for a libel suit against the newspaper that has charged him with crime.

News writing is objective to the last degree, in the sense that the writer is not allowed to “editorialize.” He must leave himself out of the story. True, he may give it, in his way of telling the facts, a certain individuality and power, but he is not permitted to cross the border line between the strict presentation of news and the editorial. Only writers whose stories are signed are allowed to use the capital I. They are the exceptions in modern newspaper making. The average news writer, however brilliant his work, receives only the commendation of his fellows. It is for this he strives, and the satisfaction that comes of work well done, rather than for public recognition. Always in the middle of things, close to history in the making,—and that is one of the fascinations of the “game”—the21 newspaper man must yet remain in the background. The story is the big, the vital thing. In it, for the time being, he is willing to sink his personality.

The age of personal journalism in its old sense has passed. In the new era the writer’s personality counts for just as much, or more, but he must use it wholly as an instrument belonging to his newspaper and the public. It is not meant by this that he must work always by rule and line, but that he must refrain from coloring his story with his personal prejudices and opinions. Even the “we” of the editorial columns is fast being discarded for a more impersonal form. Most city newspapers now avoid it altogether and the same tendency is seen in the more enterprising country journals. It is still used in a large number of papers published in the rural districts, both editorially and in the news sections, but these are gossipy neighborhood chronicles rather than newspapers in the modern understanding of the word.

Impersonal writing does not consist alone in the omission of “we” and “I.” Avoid generalities that are likely to imply approval or disapproval on the part of the writer. If Smith was killed by a neighbor, tell when and where and how he was killed. Don’t generalize by saying, “A dastardly22 crime was committed.” If your story is pathetic it is not necessary to tell the reader so. Let him find it out from the simple, human facts. In describing a pretty girl, don’t stop with saying she is pretty; tell how she is pretty—tell the color of her hair and eyes.

Strive always to be specific. With this in mind you are not likely to stray far from the impersonal.

Cultivate good taste in news writing, as in all kinds of writing. Your story is read by the woman in the home as well as by the man on the street. Leave out all revolting details and think twice before you use a word or an expression of doubtful propriety. Good taste distinguishes the story written carefully, with its possible effect on the reader’s sensibilities in mind, from the story that runs recklessly into paths avoided in conversation.

Never use cheap slang. One kind of slang, that which is clean-cut and expressive, without taint of vulgarity, may afford a legitimate short-cut in news writing as in speech. An expression of this type, if it persists in the language, ultimately finds a place in the dictionary. It is the other kind of slang, the23 vulgar or silly, against which the news writer must be on his guard.

Horrible details are not wanted by the well-edited newspaper. Leave out the three buckets of blood. The word “blood” in itself brings an unpleasant picture before the reader and may shock a person of delicate sensibilities. Most newspapers caution their writers against its overuse.

Certain things are glossed over in our daily speech. This is true in ever greater degree of the newspapers. Horace Greeley said that what Providence permitted to happen he wasn’t too proud to report. That is not the working principle of the modern newspaper, which omits some things and edits others. The moral obligation of the newspaper to its readers, as well as good taste, demands the pruning down of some classes of news. “All the News That’s Fit to Print” implies this obligation.

It is poor taste to attempt facetiousness in reporting a death. Never call a body a “stiff.” Puns on the names of persons, unless they are peculiarly apt or are justified by special circumstances, are to be avoided. The same rule applies to exaggerated dialect put in an offensive manner and to nicknames of the races. These instances further24 illustrate the need of fairness and sanity in the writer’s viewpoint. Common sense is an excellent guide in many of the delicate little problems of this kind that crop up daily in every newspaper office.

Originality is the quality that gives a news story distinction. Rules may aid, but the power to make a story original must come largely from the writer himself. Many writers can put facts together into a coherent whole. The highest rewards are reserved for those who can tell old facts in a new way.

The main secret of original news writing lies in keeping the impression fresh. Everything interests the new reporter. As he gains familiarity with the work, there is danger that his viewpoint will become jaded. Especially if he is covering the same run of news day after day must he fight against this tendency to fall into a rut. The newspaper has no use for the man in a rut. The reporter who becomes cynical loses the news writer’s best asset, the power to feel the pathos or the injustice or the humor of the thing he is writing about. If he himself cannot feel his story he is not likely to impress the reader with it.

25 The newspaper workshop, unlike any other, must create something different every day, although human nature, from which it gets its raw materials, remains the same through the ages. There is no variation from one day to another in the basic themes of the news, but there is an endless variation in the local color, in the shadings of motive, in all the details that go to make one story different from all others. Take the story of death in a tenement house fire. There is the outline, the basic fact, of stories without number; yet each story, told with its wealth of human, moving detail, has the power to affect the reader as if the theme itself were absolutely new. A dozen houses in the same block look alike from the outside; yet the life that each conceals is different from the life in all the others.

Here, then, is need for originality in the writing of news. If the reporter’s outlook is cynical he is likely to overlook the human side of the story for the lifeless skeleton of commonplace facts. His story may be mechanically correct, but it has no power of appeal. Without distorting a single fact, in plain, everyday words, the news writer may tell a story of human suffering that will rouse his readers to generous response. This he may do, not by26 editorial comment, but by putting the facts in the most effective, which is usually the simplest, manner. Editorial comment in such a story would weaken the effect. The facts, properly told, are enough.

One word of caution perhaps should be given: In looking for the feature do not descend to the trivial. To return to an illustration just used, don’t write the lead of your fire story on the rescue of the family cat and overlook the fact that human lives were lost. Originality does not consist in straining after a feature at the expense of the vital things in a story. Triviality comes with cynicism. The power to be truly original, to put life into a story based on a commonplace theme, comes with the broad, human sympathy that results from keeping the impression ever fresh.

I.—The following story, adapted from a newspaper, violates practically every rule that can be laid down for the writing of news. Apart from its errors of style, it is written with prejudice and in bad taste. Rewrite the facts in half the present space, remembering (1) to be fair; (2) to leave yourself out of the story; (3) to omit revolting27 details; (4) to avoid “fine writing” and cheap slang.

Tom Jones, one of Smithton’s worthless citizens, tried to shuffle off this mortal coil last Friday afternoon by cutting his throat with a pocket knife.

It seems Jones had filed complaint against John Smith and Susie Williams for stealing. They were brought up in Justice Wagner’s court on Friday afternoon for trial, Jones being the prosecuting witness. When he was put upon the witness stand he flatly contradicted himself in statements made in his complaint to the Prosecuting Attorney. When he did this Mr. Brown at once dismissed the case against John Smith and Susie Williams and filed complaint against Jones for perjury, and put him under arrest. Constable Walker at once took him in charge and was preparing commitment papers, when Jones expressed a wish to go into the hall for a drink of water, which permission was given him by the constable. Soon after he had left the room an unusual noise was heard like the rushing of water and on investigation the man was found lying on the floor with his throat cut and the blood spurting like water from a fountain. He stuck the blade of an ordinary pocket knife into his throat and severed some of the arteries, and would probably have bled to death, except for the unfortunate arrival of a physician who stopped the blood, and he is now in a fair way to recover and may yet go over the road.

(“It seems” is unnecessary at the beginning of the second paragraph. Instead of “tried to shuffle off this mortal coil” say simply that he “tried to kill himself.” Cut out the grandiloquent phrases.)

28 II.—Note the stereotyped form of the following story, in which the feature is obscured by a mass of routine detail. The story is as lifeless as if it had been constructed by filling in blank spaces in a set form. Although it has certain unusual elements, it is totally lacking in originality of treatment:

After he had been arrested on complaint of Henry Flannigan, 56 years old, who conducts a repair shop at 1000 Center street, on a charge of stealing two revolvers from the shop Sunday afternoon, William Weaver, 18 years old, of 3445 Broadway, turned on the man and accused him of being a second Fagin, of running a fence and of having several small boys employed to steal goods for him.

The police arrested Flannigan and his sons, Henry, Jr., aged 15, and Fred, 14, at their home, 841 Division street, and Alex. Jones, 19, 1043 West avenue. Flannigan denied he was running a “fence” but admitted buying a lot of goods from the boys. They were locked up at the Fifteenth District Police Station.

(Query: Does the average reader understand what “running a fence” means? Why not make this clear? It may be noted that some newspapers insist that police stations be identified for the reader, not by their numbers, but by the names of the streets on which they are situated. Thus, in St. Louis, the Fourth District Station is called the Carr29 Street Station; the Ninth, the Dayton Street Station, and so on. The number, as a rule, means nothing to the reader, while the street name gives him at once an idea of the locality.)

III.—In the following short feature story the writer has got away from set forms and produced a readable story. Little stories of this type are highly esteemed by newspapers with a leaning toward human-interest news—especially if they are accompanied with pictures:

CHICAGO, Nov. 7.—Stephen Rheim hit into a double play, although he didn’t know it for several days, when his safe hit won a game for the West Chicago High School baseball team over the Wheaton nine last June. In the grand stand was Miss Catherine Smith, also of West Chicago, and a loyal fan. “If he makes a hit I’ll marry him,” she cried, according to friends, as Rheim came to bat at a critical point in the game. After Rheim’s hit had won the game friends told him of Miss Smith’s remark and introduced him to the blushing young woman, who explained that she was “just joking.” But Rheim fell in love and remained there.

The surest guarantee for right-doing in journalism is contained in the teaching that right is always right and that it must be done for its own sake. This is the great basic truth to be taught the students of schools of journalism and impressed upon the minds of all newspaper workers. No other “endowment” than this of sound principles is to be desired, either for newspapers or individuals, because both must work out their own salvation in life’s daily battle, which is won for the right only by those steadfast souls that fight for the sake of right alone.—From an editorial in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

The haste and hurry of which so much is made may and does prevent polished work in a newspaper office. But it does not prevent accurate, careful, painstaking work. The history of the world which lay on your doorstep this morning is amazingly accurate; the mistakes in it are few and far between ... The average high school of to-day turns out a variety of English that the best natured city editor consigns to perdition in seven tongues, and beats out of the aspiring cub without delay or remorse. And in the important matter of brevity and directness of saying what you have to say in the curtest and plainest phrase of which the language is capable, the newspaper is the greatest educator in the world.—From an article by George L. Knapp.

A first essential of good news writing is accuracy. The word should be graven in the mind of every reporter and every editor. It is spoken by31 the city editor to his reporters almost every hour of his working day. Placards on the walls may call attention to it, as in some offices where, with laudable brevity, the motto is urged upon the staff:

ACCURACY

TERSENESS

ACCURACY

If a story is accurate, if it is written with a nice attention to detail, it is likely to be fair. If a story is not accurate, it is not news in the best sense.

Accuracy implies more than mere grammatical correctness. It means more even than the stating of every fact with precision. A story may be taken to pieces, fact by fact, and every sentence found to be correct; yet the whole may give a false impression. Accuracy means the spirit as well as the letter of the truth.

Truthful, precise writing is the fruit of accurate observation. If one would write news, he must learn first to see news clearly and without prejudice. Therein the trained reporter excels the casual observer. The one has learned to observe keenly; the32 other, well equipped though he may be in the rules of rhetoric, has not schooled himself in the business of seeing things with an eye single to getting the facts in right proportion. Learn to observe and you will have gone far toward mastering the art of news getting and news writing. Casual observation is nearly always faulty. Take for example the conflicting statements of persons on the witness stand. One man, telling his version of an automobile accident, swears the car was going fully thirty miles an hour, another is certain the speed was only eight miles; one heard the driver sound a warning “honk,” another is equally positive no warning was given. Each witness is a reputable citizen and each thinks his version is the truth. The discrepancy in their testimony is due, not to any effort to deceive, but to the common failure to observe carefully.

It is the business of the newspaper man, whose eyes must serve thousands of readers each day, to see rightly what others see imperfectly or not at all. He is subject to the same human limitations as the others, but he must make it his duty, by training his mind and his eye, to reduce those limitations to the minimum. Then, and then only, can33 he gather and write news with the maximum of efficiency.

In giving names and street addresses there is special need of accuracy. Watch, too, the spelling of all the words in your copy. Remember the dictionary is made for use.

The average good citizen likes to see his name in print, but he is deeply offended at seeing it misspelled. Smythe’s name is a thing peculiarly his own; he can never cherish any particular regard for the newspaper that persists in calling him Smith. So with Browne and Maughs and Willson. Their names are not Brown, Moss, Wilson. A reader whose name is misspelled feels, unconsciously perhaps, that he has been robbed of some intimate possession. A blow has been aimed at his individuality. To paraphrase a great reporter of life, his “good name” has been stolen, and as a good citizen he resents the theft.

The misplacing of an initial or the careless dropping of a letter from a name may cost the newspaper a subscriber. Certainly it convicts the paper of inaccuracy in one man’s eyes. He reasons that34 if the paper is mistaken in the spelling of his name, it may be guilty of other grave inaccuracies in its news. His faith in the paper is shaken. And the newspaper that loses the faith of its readers is in danger of losing the good will that is its chief asset.

Care should be taken in the writing of street addresses. The difference between two street numbers may represent the difference between respectability and its opposite. A serious injustice may be done a person by printing his name with the wrong street address. Such a mistake was made not long ago by a western newspaper, which gave an address in a neighborhood of doubtful reputation to a citizen of high standing. As a result of the writer’s carelessness the newspaper was sued for libel.

The reporter should be constantly on his guard in taking down the addresses given by unknown persons. Especially is this true with reference to the data furnished by criminals for the police “blotter.” It is a common practice of habitual criminals to give as their own the addresses of reputable citizens.

Learn all you can of the city in which you work.35 Such knowledge will be invaluable as a safeguard against many pitfalls. The city directory is an excellent guide, but sometimes is inaccurate.

Spell correctly. This applies not alone to proper names. Some news writers are prone to shift the burden of spelling to the man who edits the copy or to the proofreader. Doubtless there are many brilliant news gatherers who are deficient in spelling, but, other things being equal, the man who spells correctly is preferred to him who is slovenly in this respect. Bad spelling, though not fatal to a writer’s chances, is often a sign of lazy habits of mind. The precise thinker, as a rule, has too much regard for the tools of his trade—his words—to abuse them. The city editor judges the new man largely by his copy. The story that shows attention to spelling, to all the little niceties of writing, assuredly has a better chance of a favorable reception than the story, of equal news value, that betrays carelessness.

If any hard-and-fast first principle relating to accuracy can be laid down, it is this: Get the names36 right. Once this principle is grounded in the mind of the reporter, he is fairly sure to strive for accuracy in all the details of his story.

Persons who know nothing of the inner workings of the newspaper office may profess to believe that stories are written without regard to accuracy and are thrown into type haphazard, just as they come from the writers. Nothing could be farther from the truth. A newspaper that permitted such a condition would be swamped with libel suits within a week. In every newspaper office, certainly in every newspaper office worthy the name, there is an unceasing war against inaccuracy of every kind. The new reporter learns this when he comes in jubilant from an assignment, only to be sent back to get the middle initial of a name. The out-of-town correspondent learns it when he is called from his bed by long-distance telephone to explain a vague statement in a story he had wired earlier in the night. When one considers the difficulties under which news is gathered and the limited time at the newspaper’s command, the wonder is not that errors occasionally creep into the news columns but that the errors are so few.

The newspaper as it goes to the reader, though it is the product of many very human persons working37 under pressure, is remarkably accurate. A painstaking effort has been made to give the reader a true picture of the day’s happenings. Copy readers have gone over the reporters’ copy for errors of fact and of style; proofreaders have corrected typographical errors after the matter has been set in type; one or more editors have read the revised proofs with an eye single to detecting faults.

The newspaper, of all modern institutions, is the most human. It is written by, for and about men and women. Its failings are the common failings of humankind. Forewarned thus against himself, it is the duty of the news writer, even while he works with one eye on the clock, to be always vigilant in the battle against inaccuracy—to do his full share, and more, in keeping the columns of his paper free from misstatement of every kind.

The following stories are presented, not for any specific bearing on the discussion of accuracy, but as “horrible examples” of bad news writing in general. Inaccuracy in a news story seldom stands alone as a fault, because if a story is inaccurate the chances are it is deficient in other respects. The writer who does not take his work seriously enough38 to get his facts correct is not likely to pay attention to style. The stories here reproduced may serve as a warning against some of the faults pointed out in the preceding chapters.

I. This and the story under II show the absurdity of attempted “fine writing”:

Shrouded in deep mystery and in spite of the fact that strenuous efforts were made to keep the details of the affair secret, startling facts regarding the robbery of the Blank sorority house came to light yesterday. The house was entered by a burglar some time during the Christmas recess and some valuable silverware was taken.

But this is not all. Although when interviewed on the subject the members of the sorority refused to give any of the details to the public, some unique traits have developed in the burglar which may enable an ambitious Sherlock to unravel as deep a mystery as has ever puzzled Pinkerton’s band of trained sleuths.

(Query: Isn’t it about time to give the word “strenuous” a needed rest?)

II. The story of a death was told thus in a small newspaper:

Mrs. Eliza Williams, mother of Mrs. Geo. Brown, was released from her physical surroundings Saturday morning at ten o’clock and called to occupy a building, a house not made with hands eternally in the heavens. She has been in this earth life 87 years.

(Evidently the foregoing means: “Mrs. Eliza Williams, mother of Mrs. George Brown, died at39 10 o’clock Saturday morning. She was 87 years old.” The simplest style is always the best in writing of death. Say “body,” not “remains”; “coffin,” not “casket”; “the dead man (or woman),” not “the deceased” or “the defunct.” “Burial” is better than “interment.” “The late” is nearly always useless. “Obsequies” implies that the ceremonies were imposing; in most cases “funeral” is the proper word. Never use a flippant word in a death story. In all news writing spell out proper names: e.g., “George,” not “Geo.” Most newspapers use numerals in giving the hour, as 10 o’clock. It is usually preferable to place the hour before the day; thus, “at 10 o’clock Saturday morning.” Be careful to refer to the dead in the past tense; the verb in the last sentence of the story quoted should be “had been.”)

III. Note the use of cheap slang in the following story:

Fred Smith, a young man about 18 or 19 years old, who formerly resided in this neighborhood but more recently at Jonesburg, had been boozing at the saloon all day and in the evening walked out of that burg on the railroad track. He evidently fell with his head down on one side of the dump and one foot over the rail. The 7 o’clock passenger struck him and mashed the foot. He was picked up by the train crew and brought to town and received medical attention.

40 (It is seldom in good taste, nor is it safe, to accuse a person of drunkenness. Bear in mind the injunction: Tell the facts and let the reader draw his own conclusions.)

The newspaper man is compelled, as the price of success in his calling, and often through severe experience, to learn that only that which is true is “news.” There is a popular impression that all is grist that comes to the newspaper mill, and that everything brought into the office is published. The fact is that the hardest task of newspaper work is to sift the truth out of the masses of falsehood offered daily.... Daily newspaper workers have neither time nor need to fabricate falsehoods for public deception. Their time and their energies are too fully engaged in trying to winnow out the truth from the ignorant or willful distortions of it with which they have to deal daily. Often the falsehoods are unintentional, and arise from the fact that few people are gifted with ability to tell the exact truth, and nothing else, about what they have seen or heard. But they have also to deal with masses of downright lies, inspired by interest or malice.—From an editorial in the Chicago Inter-Ocean.

The foregoing chapters have dealt with news writing in its general aspects. This and succeeding chapters will be devoted to the more technical phases of the subject.

It is not the purpose here to discuss in detail methods of gathering news, but to tell how to write news. The reporter, when he sits down to his42 story, is assumed to be in possession of the facts. The problem then is how to put those facts together most effectively. But since news writing presupposes news gathering, a general knowledge of the reporter’s work and of what is implied by the term “news” is essential to a clear understanding of the technical side of the story.

What the eyes are to the body the reporter is to his paper and to the public that reads it. His work is the foundation of modern newspaper making. Editorial comment illuminates the news, make-up and headlines aid in its attractive presentation but after all the story is the main thing. It is for the story that all other features of the newspaper exist.

No matter what branch of newspaper work one may eventually enter, training gained as a reporter will be invaluable. The men who reach executive positions in a newspaper office without having served a reporter’s apprenticeship are rare exceptions. Practically all who have attained high rank in journalism began work as gatherers of news. They learned first to see news and to estimate its values.

A reporter may be able to see news without being43 able to write a good story, but the opposite seldom holds good. Certainly the best news writers are those who have learned, as reporters, what news is. The city editor of a metropolitan newspaper holds his position largely by virtue of his ability to pass quick and accurate judgment on the news value of a story. He has a “nose for news” that enables him to discard the trivial in the grist of the day’s happenings for the vital and interesting. It is this ability that the reporter must cultivate by every means in his power.

News has been roughly defined as that which interests people. But that definition is too general. A book or a sermon or a play may interest people, but in themselves they are not news. The fact, however, that a book has been published or a sermon preached or a play produced, is news, if that fact has an element of public interest.

The importance of a story in the eyes of the editor depends on one or more of several considerations—on the property involved, as in a fire or an earthquake; on the number and the prominence of the persons concerned; on the distance of the happening from the place of publication; on the timeliness44 of the story; on the element of human interest. This list is not exhaustive; local and temporary reasons often have weight in the editor’s judgment of a given story. To illustrate, suppose a newspaper is waging a crusade against grade crossings in its city. The story of a grade crossing accident immediately assumes an importance for that newspaper beyond its ordinary news value. Before the crusade was started the story might have been told in a paragraph; now it is allowed to run at length.

Remember, in forming your estimate of the news value of a story, that the newspaper is read by men and women of all classes—by the banker and his stenographer, the day laborer and the college professor. A story is valuable as news in proportion to the number of persons it interests. The account of a great disaster, like the San Francisco earthquake and fire, appeals to all readers. It is the big news of the day, taking precedence over all other stories in the make-up of the paper. News of an increase in the cost of some necessary article of food is valuable because of the vast number of persons it affects. So with the story of a national election, a great labor strike or a declaration of war.45 These are the exceptional stories whose importance as news is as obvious to one unskilled in newspaper making as to the trained editor.

But what of the more commonplace happenings of the day? The problem that confronts the editor daily is to make a paper that will appeal to as many readers as possible. The man who asks a newspaper to print, as news, a long dissertation on recent discoveries in Asia Minor mistakes the purpose of daily journalism. Such an article might interest other men engaged in making similar discoveries, but it would be passed over by the vast majority of readers.

Newspapers are often charged with pandering to the sensational. Why, it is asked, do they print the story of a murder on the first page, while general religious news is published in a separate department, if published at all? The shop window of the merchant furnishes the answer: the merchant, like the newspaper, puts his most alluring wares in front. The display in both cases is based on a sound knowledge of human nature. What do people talk about in the evening? On his answer to that question the editor’s choice of stories largely depends. Mrs. Jones, talking to Mrs. Smith, tells first about the elopement of a neighbor’s daughter.46 Not until that is disposed of does she comment on last Sunday’s sermon.

Newspapers formerly were made on the assumption that men were the only readers. Now they are made with the tastes of women ever in mind. The evening newspaper, especially, is edited for the women, on the theory that it is taken home in the evening, while the morning newspaper is taken out of the home by the man going to work.

The newspaper is a business enterprise. In order to live it must get advertising. To get advertising it must have circulation and to get circulation it must interest its readers. It can not do this by shooting continually over the heads of its readers. But, while the newspaper reflects public taste, it is generally a little better than public taste. Certain classes of news are suppressed and others are carefully edited. What is done with news on the border line depends on the individual policy of the paper.

While the variety of news is infinite and no hard-and-fast classification can be attempted, news stories may be roughly grouped in three large divisions:

1. The story based on a recent happening of more or less importance in itself, as a fire or a business47 transaction, told without attempt at embellishment. This may be called the plain news story. It is the primary form of news writing. Clearness and conciseness are its first requisites.

2. The story called by the newspaper man a feature or a human-interest story. Into this class falls practically all news writing—except that set aside in departments—which does not fit in the preceding group. Some writers perhaps would make a distinction between “feature” and “human-interest” as applied to news, but since the terms are often used interchangeably, it has seemed simpler to include them under one head. A feature story, then, adopting this as a general term, is a story based on something odd or unusual, humorous or pathetic. Such a story often depends more on the manner of the telling than on what is told. “Human-interest” narrows the definition to the story that appeals to the emotions by its humor or pathos. Stripped to the bare facts, a human-interest story may be without news value; but told with the keen sympathy that comes of accurate observation and a knowledge of human nature it may have an even greater value, that of giving the reader a clearer insight into the real life about him. Feature stories concerning odd or unusual or grotesque48 things, such as the man with the longest beard in the world or the boy who builds an airship in his back yard, may be only a few lines in length or they may be developed into page Sunday articles. A study of the magazine and feature pages of any metropolitan daily paper will show the possibilities of this kind of story. Almost any subject may be made into a feature story if the writer has the gift of originality.

3. Department or classified news. Under this head come stories that are grouped by the newspaper in separate departments, as sporting news, market reports and society notes. The extent to which news is classified varies widely with different newspapers. Some include only a few broad departments, while others classify news on many subjects, as schools and colleges, genealogy, women’s clubs, etc. When, however, a department story becomes of general interest, it is taken out of its department and placed in the general news columns. This may be done, for example, with the story of a world’s championship baseball game or of a sudden break in the stock market.

It must be understood that this grouping is subject to many variations. There is often an overlapping of the three kinds of stories described.49 The nature of news, based as it is on the doings of people, makes it impossible for one to put a finger on a story and say: This falls under Section A and is written according to Rule Blank. The classification is suggested only as a guide in the study of news writing.

The interview, one of the most important features of the modern newspaper, is not here listed as a distinct kind of story. It may either form an essential part of a story or be itself a news story of any of the types mentioned.

I. Tell how the following plain news story could be developed into a feature story of a column or more:

BOSTON, Nov. 12.—The third new star to be discovered at the Harvard College Observatory in the last six weeks was announced to-night by Professor Edward C. Pickering. Miss A. J. Gannon of the observatory staff found the star in an examination of old photographic plates taken August 10, 1899. It appears in the constellation sagittarius from that date until October, 1901.

II. Concise, well-told story of a humorous incident, used by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as a “filler” on Page 1. Note that the story is not clogged with irrelevant police data:

50 Two burglars enjoyed a laugh, and a saloon keeper’s money was saved by the wit of Joe Johnson, a negro porter, early Wednesday. The burglars entered Edward Krenninghaus’ saloon at 3948 Easton avenue, and finding the porter asleep in the back room awakened him.

“Where’s the boss’ money?” asked one of the burglars as he held a revolver to Johnson’s head. “Sakes alive,” the porter stuttered. “If the boss kept his money here he wouldn’t let me sleep in the place.” The burglars laughed heartily and departed.

III. The following story—a mother’s account of the death of her son—is a fine example of the best type of human-interest story. It was published in the New York Sun (morning), often referred to as the “newspaper man’s newspaper” because of the high standard of writing that it maintains. “Study the Sun’s style” is the advice given to reporters in many newspaper offices. The story here reproduced is by Frank Ward O’Malley. It was reprinted in the Outlook of November 9, 1907:

Mrs. Catherine Sheehan stood in the darkened parlor of her home at 361 West Fifteenth street late yesterday afternoon, and told her version of the murder of her son Gene, the youthful policeman whom a thug named Billy Morley shot in the forehead, down under the Chatham Square elevated station early yesterday morning. Gene’s mother was thankful that her boy hadn’t killed Billy Morley before he died, “because,” she said, “I can say honestly, even now, that I’d rather have Gene’s dead body brought home to me, as it will be to-night, than to have51 him come to me and say, ‘Mother, I had to kill a man this morning.’

“God comfort the poor wretch that killed the boy,” the mother went on, “because he is more unhappy to-night than we are here. Maybe he was weak-minded through drink. He couldn’t have known Gene or he wouldn’t have killed him. Did they tell you at the Oak Street Station that the other policemen called Gene Happy Sheehan? Anything they told you about him is true, because no one would lie about him. He was always happy, and he was a fine-looking young man, and he always had to duck his helmet when he walked under the gas fixture in the hall, as he went out the door.

“He was doing dance steps on the floor of the basement, after his dinner yesterday noon, for the girls—his sisters, I mean—and he stopped of a sudden when he saw the clock and picked up his helmet. Out on the street he made pretend to arrest a little boy he knows, who was standing there—to see Gene come out, I suppose—and when the little lad ran away laughing, I called out, ‘You couldn’t catch Willie, Gene; you’re getting fat.’

“‘Yes, and old, mammy,’ he said, him who is—who was—only twenty-six—‘so fat,’ he said, ‘that I’m getting a new dress coat that’ll make you proud when you see me in it, mammy.’ And he went over Fifteenth street whistling a tune and slapping his leg with a folded newspaper. And he hasn’t come back again.

“But I saw him once after that, thank God, before he was shot. It’s strange, isn’t it, that I hunted him up on his beat late yesterday afternoon for the first time in my life? I never go around where my children are working or studying—one I sent through college with what I earned at dressmaking, and some other little money I had, and he’s now a teacher; and the youngest I have at college now. I don’t mean that their father wouldn’t send52 them if he could, but he’s an invalid, although he’s got a position lately that isn’t too hard for him. I got Gene prepared for college, too, but he wanted to go right into an office in Wall street. I got him in there, but it was too quiet and tame for him, Lord have mercy on his soul; and then, two years ago, he wanted to go on the police force, and he went.

“After he went down the street yesterday I found a little book on a chair, a little list of the streets or something, that Gene had forgot. I knew how particular they are about such things, and I didn’t want the boy to get in trouble, and so I threw on a shawl and walked over through Chambers street toward the river to find him. He was standing on a corner some place down there near the bridge clapping time with his hands for a little newsy that was dancing; but he stopped clapping, struck, Gene did, when he saw me. He laughed when I handed him the little book and told that was why I’d searched for him, patting me on the shoulder when he laughed—patting me on the shoulder.

“‘It’s a bad place for you here, Gene,’ I said. ‘Then it must be bad for you, too, mammy,’ said he; and as he walked to the end of his beat with me—it was dark then—he said, ‘They’re lots of crooks here, mother, and they know and hate me and they’re afraid of me’—proud, he said it—‘but maybe they’ll get me some night.’ He patted me on the back and turned and walked east toward his death. Wasn’t it strange that Gene said that?

“You know how he was killed, of course, and how—Now let me talk about it, children, if I want to. I promised you, didn’t I, that I wouldn’t cry any more or carry on? Well, it was five o’clock this morning when a boy rang the bell here at the house and I looked out the window and said, ‘Is Gene dead?’ ‘No, ma’am,’ answered the lad, ‘but they told me to tell you he was hurt in a fire53 and is in the hospital.’ Jerry, my other boy, had opened the door for the lad and was talking to him while I dressed a bit. And then I walked down stairs and saw Jerry standing silent under the gaslight, and I said again, ‘Jerry, is Gene dead?’ And he said ‘Yes,’ and he went out.

“After a while I went down to the Oak Street Station myself, because I couldn’t wait for Jerry to come back. The policemen all stopped talking when I came in, and then one of them told me it was against the rules to show me Gene at that time. But I knew the policeman only thought I’d break down, but I promised him I wouldn’t carry on, and he took me into a room to let me see Gene. It was Gene.

“I know to-day how they killed him. The poor boy that shot him was standing in Chatham Square arguing with another man when Gene told him to move on. When the young man wouldn’t, but only answered back, Gene shoved him, and the young man pulled a revolver and shot Gene in the face, and he died before Father Rafferty, of St. James’s, got to him. God rest his soul. A lot of policemen heard the shot, and they all came running with their pistols and clubs in their hands. Policeman Laux—I’ll never forget his name or any of the others that ran to help Gene—came down the Bowery and ran out into the middle of the square where Gene lay.

“When the man that shot Gene saw the policemen coming, he crouched down and shot at Policeman Laux, but, thank God, he missed him. Then policemen named Harrington and Rourke and Moran and Kehoe chased the man all around the streets there, some heading him off when he tried to run into that street that goes off at an angle—East Broadway, is it?—a big crowd had come out of Chinatown now and was chasing the man, too, until Policemen Rourke and Kehoe got him backed up against a wall. When Policeman Kehoe came up close, the man54 shot his pistol right at Kehoe and the bullet grazed Kehoe’s helmet.

“All the policemen jumped at the man then, and one of them knocked the pistol out of his hand with a blow of a club. They beat him, this Billy Morley, so Jerry says his name is, but they had to because he fought so hard. They told me this evening that it will go hard with the unfortunate murderer, because Jerry says that when a man named Frank O’Hare, who was arrested this evening charged with stealing cloth or something, was being taken into headquarters, he told Detective Gegan that he and a one-armed man who answered to the description of Morley, the young man who killed Gene, had a drink last night in a saloon at Twenty-second street and Avenue A and that when the one-armed man was leaving the saloon he turned and said, ‘Boys, I’m going out now to bang a guy with buttons.’

“They haven’t brought me Gene’s body yet. Coroner Shrady, so my Jerry says, held Billy Morley, the murderer, without letting him get out on bail, and I suppose that in a case like this they have to do a lot of things before they can let me have the body here. If Gene only hadn’t died before Father Rafferty got to him, I’d be happier. He didn’t need to make his confession, you know, but it would have been better, wouldn’t it? He wasn’t bad, and he went to mass on Sunday without being told; and even in Lent, when we always say the rosary out loud in the dining-room every night, Gene himself said to me the day after Ash Wednesday, ‘If you want to say the rosary at noon, mammy, before I go out, instead of at night when I can’t be here, we’ll do it.’

“God will see that Gene’s happy to-night, won’t he, after Gene said that?” the mother asked as she walked out into the hallway with her black-robed daughters grouped behind her. “I know he will,” she said, “and I’ll—”55 She stopped with an arm resting on the banister to support her. “I—I know I promised you, girls,” said Gene’s mother, “that I’d try not to cry any more, but I can’t help it.” And she turned toward the wall and covered her face with her apron.

This story was reprinted in the Outlook, under the title, “The Death of Happy Gene Sheehan,” with the following editorial preface:

“The ‘stories’ of the reporter on a daily paper are written under such trying conditions of hurry and confusion that they seldom have, in the very nature of the case, what is called the ‘literary touch.’ But occasionally a news writer produces a story which has real qualities of vividness, pathos and power. The following account of the death of Happy Gene Sheehan, which we reprint by special permission from the New York Sun, belongs to this class. On the morning when it appeared, a group of business men, one of whom has related the incident to us, were riding from Peekskill to New York in a commuters’ club car. Several games of cards were in progress, and the rest of the passengers were busy with their newspapers or in conversation. Suddenly a clergyman, who had been reading the Sun, rose and asked permission to read a story which he had just finished. He had read56 only a few lines before the card games were stopped, newspapers were laid down, and every man in the car was giving earnest attention to the reading. It was the story of Happy Sheehan; and the effect which it produced upon such a group of busy men, not easily to be moved by sentiment, and not at all, except to disgust, by sentimentality, was the best compliment which it could have received.”

Newspaper English is the standard. There may be critics, who belong to a past generation and who have learned by rule, but for flexible, expressive use of the language the newspaper and the other publications for the masses cannot be surpassed.... When scientific or technical terms are employed there is sufficient context to make clear the application. There is no strained effort or laborious use of words to-day. Nor is there a deterioration, as some of the professors of English would have us believe. Newspaper style is simple, direct, concise, instructive and self-explanatory. This sets the standard for the great mass of the public.—From an editorial in the Washington Herald.

The method of telling the news story is usually the opposite of that employed by the writer of fiction. Instead of giving the setting of his story and then working gradually toward the climax, the news writer, as a rule, puts the climax in the very beginning—in what is technically called the lead of the story. If three persons were killed in a train wreck he tells that fact succinctly in the opening sentence. There is no halting, no preliminary catching of the breath, but a straightforward plunge into the main facts. Here again news writing is closely akin to58 everyday speech. If you were telling, in a hurried conversation, of a baseball game you had just seen, you would begin by giving the score—the result of the game. Then, as time permitted, you would elaborate with details. That is the method of the news story of immediate importance, whose primary purpose is to inform.

A distinction was made in the preceding chapter between a story of this kind and a feature story. What is said here of the lead does not apply to feature writing, which often follows the fictional method of holding the reader in suspense. Neither does it apply to the news story which is told so briefly that a summary of the facts in the beginning would result in immediate and useless repetition in the body of the story.

The straight news lead of the story that is allotted enough space to warrant the giving of details contains the main facts boiled down in the opening sentences. The lead should be complete in itself, so that the reader may grasp the essentials without being compelled to read the entire story. Remember that your story is not an essay to be read at leisure. It is written for busy men and women,59 and its function is to inform, and inform quickly. The average American reader has no time for the rambling type of story that describes the “dark and stilly night” to the extent of a column and then tells in the last paragraph that a man was murdered. He demands to know about the murder at once. Then, if he is interested, he will read the details.

Seldom is the lead longer than a paragraph, unless it is broken up by making each sentence a paragraph. This first paragraph—the most important in the story, since it tells the facts in a nutshell—should be made as concise and pithy as possible. Tell all the essential facts, but avoid cumbersome sentence structure in doing so. Short, simple sentences are the most forcible. Above all, make the lead easy for the reader to understand.

Who? What? When? Where? Why? It is a standard rule that the news lead should answer these questions about the story. Properly interpreted, the rule is a good one, but it may be applied too literally. The beginner in news writing is inclined to go to the extreme in trying to answer each question in the first sentence. The result is often an involved sentence in which the reader becomes60 lost in a maze of participles and qualifying clauses. Here is a sample from a story turned in by a “cub” reporter: