TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

In the original text a narrative change from one battalion to another was indicated by some additional blank space. In this etext two blank lines similarly indicates this transition.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter or section.

The original text had a dot under the superscripts; this dot has been removed in the etext.

Six town names with āo ending have been changed to ão for consistency.

The book title and author have been superimposed by the transcriber on the image of the original cover; this modified image is placed in the public domain.

A larger version of each map can be displayed by clicking on the map image.

Some other minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE RIFLE BRIGADE

LONDON: PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

AND PARLIAMENT STREET

(THE PRINCE CONSORT’S OWN)

FORMERLY THE

95th

BY

SIR WILLIAM H. COPE, BART.

LATE LIEUTENANT RIFLE BRIGADE

WITH MAPS AND PLANS

London

CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1877

TO

FIELD-MARSHAL

HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS

THE PRINCE OF WALES, K.G.

&c. &c.

COLONEL-IN-CHIEF

THIS RECORD OF THE SERVICES OF

THE RIFLE BRIGADE

IS

BY HIS GRACIOUS PERMISSION

MOST RESPECTFULLY

DEDICATED

A wish had long been entertained and often expressed by Riflemen, both by those serving in the Regiment and by those who had formerly served in it, that a detailed record of its services should be compiled. It was suggested to me by many of my friends that I should undertake this task. The will certainly was not wanting; but the ability to carry out their wish has not, I fear, been equal to their partial opinion, or to my own desire to do justice to the subject.

The materials for such a compilation were not wanting. The late Colonel Leach published a very brief sketch of the Services of the Regiment,[1] and his ‘Rough Notes’[2] give many and accurate particulars of events during the time he served in it. The Autobiography of Quarter-Master Surtees[3] is a most valuable record of the events in which he took part. Surtees came as a private into the 95th from the 56th Regiment in 1802. His good conduct raised him through the various grades of non-commissioned officer to Quarter-Master of the old 3rd Battalion.[viii] His book I have found, on comparing it with other records, most accurate in every particular. As the 3rd Battalion was disbanded before the order for drawing up and preserving regimental records issued from the Horse Guards, no formal record of its services exists;[4] and had it not been for the facts and dates preserved and recorded by Surtees, I should have found it difficult, if not impossible, to have given any detailed account of the actions of that Battalion in the Peninsula and at New Orleans. Though tinged with the peculiar religious opinions which Surtees adopted, and which perhaps scarcely have place in a military record, his work is written with a distinctness and in a style which do him honour. And the high character of the man which breathes through his work has led me to place every confidence in his statements.

Very different are Sir John Kincaid’s two books.[5] These, though written in too jocular and light a strain for regular history (‘ad jocos forte propensior quam decet’) contain many anecdotes and facts of which I have gladly availed myself. And I have found his dates and statements confirmed by other and more formal materials to which I had access.

Costello’s little work[6] has also afforded me much information; and he has recorded many circumstances unnoticed or lightly touched upon by others.

The ‘Recollections of Rifleman Harris’[7] have[ix] also been of considerable service to me in compiling this record, especially as preserving many particulars, elsewhere unnoticed, of the retreat to Corunna and of the expedition to Walcheren. His editor, however, seems to have used the materials Harris wrote or dictated without any attempt at arrangement; so that it is difficult, and in some cases almost impossible, to disentangle the narrative, or to arrange the events he describes in chronological order.

The valuable List of the Officers of the Regiment, compiled by Mr. Stooks Smith,[8] has also been of much use to me; and I have to thank that gentleman for some additional information, and for permission to republish that list with continuation to the present time, of which I hope at some future period to avail myself.

Nor can I close this list of printed works bearing on the history of the Regiment without mentioning the ‘Recollections of a Rifleman’s Wife,’ by Mrs. Fitzmaurice, to which I am indebted for many facts and anecdotes, many of them especially valuable because they relate to the less stirring times of peace; nor without expressing my thanks for her permission to use the materials she has thus preserved.

When I proceed to acknowledge the personal recollections and the journals of services in the Regiment which have been placed at my disposal, I scarcely know how adequately to express my obligations to those who have aided me. Everyone who[x] has worn the green jacket, from Generals to private Riflemen, to whom I have applied, or who has heard of my endeavour to preserve a record of the services of the Regiment, has, almost without exception, most kindly placed journals and letters in my hands, or assisted me by personal reminiscences.

The aid of my friend Lieutenant-General Sir Alfred Horsford procured for me the transcript of many valuable records and the elucidation of many points which I could not otherwise have obtained. Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Lawrence not only communicated to me many particulars of the services of the 2nd Battalion in the Crimea, but placed in my hands his private letters written from thence, which afforded me most valuable information. Major-General Hill was so good as to draw up for me a detailed statement of the services of the 2nd Battalion, which he commanded during the Indian Mutiny. To Major-General Leicester Smyth I am indebted not only for a narrative of the battle of Berea, but also for the perusal of a private letter written by him directly after, and describing that engagement, and for much valuable information. By permission of Brigadier-General Ross, Lady Ross transmitted to me his letters to his family both from the Crimea and from India, to the perusal of which I cannot attach too great importance.

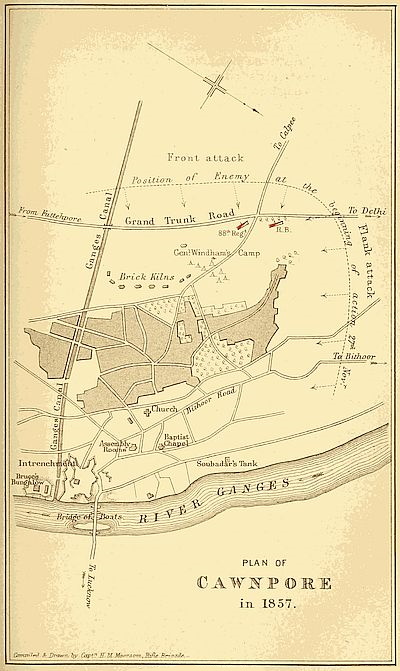

Colonel Smith, now I believe the oldest officer of the Regiment living,[9] has freely and kindly communicated to me his recollections of services in the Peninsula and elsewhere, and has patiently borne with my many enquiries which his accurate memory has enabled him to[xi] answer. To Colonel Dillon I am indebted for much valuable information which he kindly obtained for me. Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander was so good as to write out for me from his journals a detailed account of the movements and actions of the 3rd Battalion in India, in which he took part. Lieutenant-Colonel Sotheby had the kindness to transcribe for me his journal during the Indian Mutiny, and to illustrate it with sketch-maps. Lieutenant-Colonel FitzRoy Fremantle, Lieutenant-Colonel Eyre, Captain Percival, Captain George Curzon, and Major Harvey placed in my hands their valuable journals and diaries. Colonel H. Newdigate and Captain Austin favoured me with detailed and important particulars as to the services of the companies of Riflemen who formed the Camel Corps. To Lieutenant-Colonel Green I am indebted for his own narrative and that of Mr. Mansel (drawn up at the time) of the affair at Jamo in which he was so desperately wounded. I have to thank Captain Boyle for allowing me to see his continuation to the year 1860 of Mr. Stooks Smith’s List of Officers, and for much other information. To Captain Moorsom I am under great obligations, not only for the three plans (of New Orleans, of Cawnpore, and of Lucknow) which he has contributed to this work, but for materially aiding me in obtaining important information. And to Surgeon-Major Reade I am indebted for an accurate and interesting account of the march to Cawnpore of Colonel Fyers’ detachment, to which he was attached.

Sergeant-Major Bond, of the Sligo Militia, and formerly of the 1st Battalion, gave me a detailed[xii] account, from his journal, of the Kaffir War of 1847–9; and Corporal Scott, late of the 1st Battalion, communicated to me a most minute and accurate journal which he kept in short-hand during the Kaffir War of 1851–52, during the Crimean campaign, and during his service in Canada. It is not too much to say that without the valuable contributions of these two non-commissioned officers it would have been impossible to give any detailed account of the doings of the 1st Battalion during these wars. Sergeant Fisher, late of the 2nd Battalion, placed in my hands an interesting journal kept during the Indian Mutiny; and Sergeant Carroll, of that Battalion, has communicated many particulars respecting the Camel Corps.

To these and to other Riflemen I owe my thanks, not only for the documents they have communicated to me, but for the kindness with which they have entertained, and the courtesy with which they have replied to my many questions for further information or details.

The officers commanding the four Battalions have given free access to, or transcripts of the several Battalion Records. These, though drawn up in obedience to an order issued in 1822, do not seem to have been compiled till some years afterwards.

That of the 1st Battalion appears to have been written by, or under the eye of, Sir Amos Norcott, who then commanded it, and by whom the transcript transmitted to the Horse Guards is signed. For it is very full and explicit in relating the actions in which he was personally engaged (as, for instance, the account of the[xiii] engagement at Buenos Ayres, which bears internal evidence of having been drawn up by an eye-witness) but is rather slight and meagre in the narrative of many Peninsular and other victories.

The Record of the 2nd Battalion, transmitted to the Horse Guards, and dated March 10, 1831, is a model of what such a document should be. It has been compiled with great accuracy; and the movements and engagements of the Battalion, the lists of killed and wounded, and the distinctions won by its officers and men, are recorded under separate heads and with great minuteness.

These Records have been continued to the present time, for the most part with great accuracy and precision.

The Records of the 3rd and 4th Battalions have also been placed in my hands. The latter, containing, of course, only the movements of the Battalion, calls for no comment; that of the 3rd Battalion has been, in the earlier parts, kept irregularly, probably in consequence of the Battalion being broken up and constantly in the field; and no one perusing it could form an idea of, or trace accurately the distinguished service of that Battalion during the Indian Mutiny.

Nor is it to Riflemen alone that I am indebted for assistance. I have to thank Major-General Sir John Adye for permission to use the plan of Cawnpore, published in his account of those eventful days; Major-General Payn for an interesting letter on the same subject; the author of the articles on Ashantee in ‘Colburn’s United Service Magazine’ for his liberal and unsolicited authority to use them as materials for my[xiv] narrative; and especially Lieutenant-Colonel Home, R.E. for his kindness in giving me tracings of the plans of the operations at New Orleans deposited in the Quarter-Master General’s Office, and for permission to have copies made of the plans prepared in the topographical department of that office for the Record of the 52nd.

I have expressed in another place the assistance I have derived from the accurately kept journal of the late Major George Simmons, and from his separate memoir on Waterloo, which were placed in my hands by his widow.

I have not attempted to trace the strategical or tactical movements of the armies of which the Battalions have formed part, for two reasons: my own inability to record what has been so well described by abler pens; and also because any attempt to have done so would have swelled this book to an extent altogether disproportionate to its object.

For it must be borne in mind that I profess to be the historian, not of wars, but of this particular Corps only, and of that part it alone bore in them.

So, in like manner, I have not recorded the deeds of other regiments which may have acted with the Riflemen, save in a very few instances where it was impossible to separate the narrative of their movements from that of the movements of regiments which fought beside, or supported them. In the case of their old and most frequent companions in arms, the 43rd and 52nd, it was unnecessary that I should record their actions, since the histories of both these distinguished[xv] Corps have been fully and well written.[10] And if others who have fought, and fought well, beside the Riflemen are here unnoticed, and as yet without a special history, they must believe that their gallant deeds, albeit unrecorded here, live in the recollection and the praise of many Riflemen.

To some readers some of the facts and anecdotes I have here recorded may appear trifling and unworthy of mention. But it must be borne in mind that I write for Riflemen, at the desire of Riflemen, and to preserve the memory of the deeds of Riflemen. By them I am sure nothing will be considered trivial, nothing out of place in a history of the Regiment, which records the valour, the acts, the sufferings or even preserves an anecdote of any (of whatever rank) of the members of that brotherhood.

W. H. C.

Bramshill: December 1876.

[1] ‘Sketch of the Field Services of the Rifle Brigade from its Formation to the Battle of Waterloo.’ London, 1838, pp. 32.

[2] ‘Rough Sketches in the Life of an Old Soldier.’ London, 1831.

[3] ‘Twenty-five Years in the Rifle Brigade.’ Edinburgh, 1833.

[4] The order for keeping regimental records is dated September 1822. The 3rd Battalion was disbanded in 1818.

[5] ‘Adventures in the Rifle Brigade’ and ‘Random Shots from a Rifleman.’

[6] ‘Adventures of a Soldier.’ London, 1852.

[7] Edited by Henry Curling. London, 1848.

[8] ‘Alphabetical List of the Officers of the Rifle Brigade from 1800 to 1850.’ London, 1851.

[9] He joined the 1st Battalion in April 1808.

[10] ‘Historical Records of the 43rd Regiment.’ By Sir Richard G. A. Levinge, Bart. 1868.

‘Historical Records of the 52nd Regiment.’ Edited by Capt. W. S. Moorsom. 1860.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Formation of an Experimental Corps of Riflemen—Expedition to Ferrol—Re-formation of the Rifle Corps—First list of officers—Account of Lieut.-Colonel the Hon. W. Stewart—Standing orders—First Expedition to Copenhagen—Nelson’s testimony—He gives a medal to the Riflemen—The Rifle Corps numbered 95—Camp at Shorncliffe under Sir John Moore—Formation of the 2nd Battalion—Account of Lieut.-Colonel Wade—Sidney Beckwith’s magnanimity—Expedition to Germany—Attack on Monte Video—Attack on Buenos Ayres—Second Expedition to Denmark—Battle of Kioge—Three companies proceed to Sweden—Arrival of Riflemen in Portugal—Affair at Obidos—Battle of Roleia—Battle of Vimiera—Both Battalions in Spain—Meeting of the Riflemen at the Trianon—Retreat—General Craufurd’s stern discipline—2nd Battalion embarks at Vigo—Fight at Cacabelos—Tom Plunket shoots a French General—Battle of Corunna—Embarkation of 1st Battalion—Casualties—Arrival in England—Death of Colonel Manningham | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

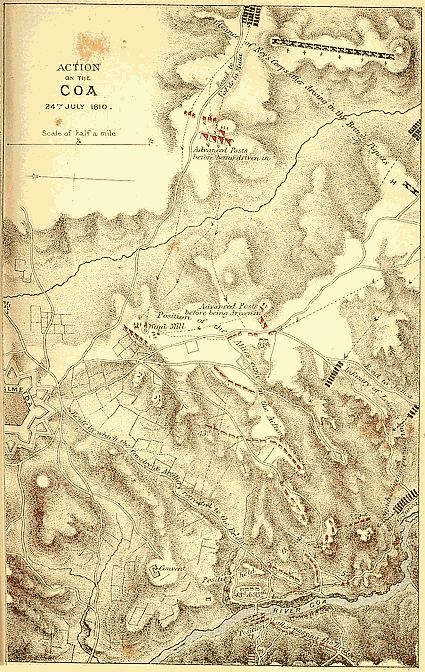

| Formation of the 3rd Battalion—1st Battalion again proceed to Portugal—Join the Light Division—March from Calzada to Talavera—March to the bridge of Almaraz—Scarcity of food—Winter quarters at Campo Major—2nd Battalion embark for Holland—Humbley seizes a French picquet—Siege of Flushing—Walcheren fever—1st Battalion on the Coa—Fight at Barba del Puerco—Craufurd’s Divisional Order—Beckwith’s system of command—Night march to Gallegos—Fight at the Coa—Casualties—Battle of Busaco—Lines of Torres Vedras—Fight at Sobral—Simmons takes some French prisoners—Massena’s retreat—Fight near Valle—Winter quarters—A company of the 2nd Battalion with Ballesteros—Defence of Tarifa—Defence of Cadiz—Battle of Barrosa | 42 |

| [xviii] | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Massena’s retreat from Santarem—Skirmishes at Paialvo; at Pombal; at Redinha—French politeness—Skirmishes at Casal-nova; at Foz d’Aronce; at Ponte da Murcella; at Freixadas—Lieutenant James Stewart—Combat at Sabugal—Skirmish at the bridge of Marialva; at Fuentes d’Onor—Battle of Fuentes d’Onor—Night panic at Sabugal—March to the Alemtejo—Cantonments on the Agueda—Retreat to Soita—Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo—Assault of San Francisco—Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo—Casualties—Anecdotes of General Craufurd—Military Executions—Siege of Badajos—Capture of La Picurina—Storming of Badajos—Casualties—Harry Smith’s romantic adventure | 71 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Character of Sidney Beckwith—Riflemen reviewed by Lord Wellington—Skirmish near Rueda; at Castrejon—Manœuvring near Salamanca—Battle of Salamanca—March to Madrid—2nd Battalion companies fight at Seville; at Puente Larga—Departure from Madrid—Death of Lieutenant Firman—Retreat to the frontier of Portugal—Sufferings of the Riflemen—Their high state of discipline—Spanish recruits—Campaign of 1813—Affair at the Hormuza—Skirmish at San Millan—Battle of Vittoria—The 95th capture the first gun; and the last at the Araquil—March to intercept Clausel; to Pamplona; to the Pyrenees—Skirmish at Santa Barbara—Night marches—Fight at the bridge of Yanci; at Echalar—First Regimental dinner—Storming of S. Sebastian—Fight at the Bidassoa—Cadoux’s picquet at the bridge of Vera—Forcing the pass of Vera—The Arrhunes | 112 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Battle of Nivelle—Fight at Arcangues—Good feeling between the Riflemen and the French outposts—Battle of the Nive—Outpost courtesies and discourtesies—Gave d’Oleron—March to Orthez—Battle of Orthez—Battle of Tarbes—Fight at Tournefeuille—Battle of Toulouse—Suspension of arms—Embarkation for England and arrival there—Expedition to Holland—Investment of Bergen-op-Zoom—Skirmishes before Antwerp; at Donk—Fight at Merxem—Failure of Graham’s attempts on Antwerp—Bergen-op-Zoom—Sorties from Antwerp and alarms—The companies in this expedition occupy Belgium, and eventually join the Battalions in the Waterloo campaign—Expedition to New Orleans—Disembarkation—James Travers captures an American picquet—Attack on the bivouack of the Riflemen—Hallen’s picquet—Advance towards New Orleans—Attacks on the [xix] American lines—Truce to remove dead and wounded—Dishonourable conduct of the Americans during the truce—Difficult march to the shore—Re-embarkation—Arrival at Île Dauphine—Sergeant Fukes turns the tables on a Yankee officer—Fort Boyer surrenders—Return to England | 154 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Embarkation for the Netherlands—Advance of the 1st Battalion to Brussels—March to Quatre Bras—Battle of Quatre Bras—Riflemen the first English engaged; under the eye of the Duke of Wellington—Retreat through Genappe to Waterloo—Battle of Waterloo—Casualties; and Anecdotes—Charles Beckwith—March to Paris—Army of occupation—The 95th made ‘the Rifle Brigade’—Return to England—Death of Amphlett—The 3rd Battalion disbanded | 195 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Home Service—1st Battalion sent to Glasgow to suppress riots—2nd Battalion proceeds to Ireland—The Duke of Wellington Colonel-in-chief—Address to him on that occasion—Both Battalions in Ireland—Names of victories to be borne on the pouch-belt—Outrage on some women of the Regiment—Engagement with Irish insurgents at Carrigamanus; and at Dasure—Embarkation of the 1st Battalion for Nova Scotia; and of the 2nd Battalion for Malta—The Depôt engaged against rioters in Ireland—Death of Sir William Stewart—The Depôts of both Battalions reviewed by the Duke of Clarence—Service abroad and at home—A Depôt Company of 1st Battalion suppresses smuggling at Hastings—Return of the 1st Battalion to England—Riflemen sent to Persia—Death of Colonel Eeles—Return of the 2nd Battalion to England—Coronation of Queen Victoria—Review in Hyde Park—Inspection by the Colonel-in-Chief and Marshal Soult—Birmingham Riots—The 1st Battalion embarks for Malta—Guards of Honour to Queen Victoria—Riots in South Wales—Embarkation of 2nd Battalion for Bermuda—Reserve Battalion formed—1st Battalion ordered to the Cape—Speech of Lord Seaton | 217 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Landing in South Africa—Marches to Kaffraria—Death of Captain Gibson and Assistant-Surgeon Howell—Bivouack on Mount Misery—Fording the Kei river—Attack on the Kaffirs—Fire at King William’s-town—Expedition to the Amatola [xx] Mountains—Surrender of Sandilli—Arrival of Sir Harry Smith—War against the Boers—Crossing the Orange river—Battle of Boemplaats—Death of Captain Murray—Submission of the Rebels—Riflemen employed in building—2nd Battalion in Canada—Shipwreck at Sault Ste. Marie—Embarkation of the 1st Battalion—Sir Harry Smith’s General Order—Return to England—The Reserve Battalion done away with | 245 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Last review by the Duke of Wellington—1st Battalion again embark for Kaffraria—Disasters of the ‘Megæra’—Landing at Algoa bay—Marches up the country—Skirmishes at Mundell’s Krantz; at Ingilby’s farm—Reconnaissance to the Waterkloof and Blinkwater—Patrols and reconnaissances—Attack on the Waterkloof—General Cathcart’s General Order—Escorts—Final attack on the Waterkloof—Road-making and patrols—Expedition to Moshesh’s country—Battle of Berea—Death of the Duke of Wellington—Riflemen guard and escort his body—His funeral—Return of the 2nd Battalion to England—The Prince Consort appointed Colonel-in-Chief—Return of the 1st Battalion—General Cathcart’s order on that occasion—Camp at Chobham | 269 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Embarkation for the East—The 2nd Battalion in Turkey and Bulgaria—Disembarkation in the Crimea—Kindness of Sir George Cathcart—Advance to Kentúgan and Kamishli—Popularity of the Riflemen with the inhabitants—False alarms—Advance to the Búlganak—Battle of the Alma—March to the Katchka and the Belbek—Russian baggage captured at Mackenzie’s farm—Attack on Balaklava—Both Battalions before Sebastopol—Wheatley disposes of a live shell—Remarkable shot by a Rifleman—Attack on Fyers’ picquet—Hugh Hannan’s single combat—Battle of Balaklava—Markham’s picquet at the Magazine Grotto—Wing of 2nd Battalion sent to the heights of Balaklava—Battle of Inkerman—Exploit at the Ovens—General Canrobert’s ‘Ordre Général’—Severe duty—Sufferings and sickness—Russian attempt to retake the Ovens—Reconnaissance on Kamara—Increased suffering and disease—Huts erected—Death of Sir Andrew Barnard—Second reconnaissance on Kamara—A 3rd Battalion added—Attacks and volunteers—Victoria Cross won by three Riflemen—New clothing—Wing of the 2nd Battalion embark for Kertch, but return countermanded—Queen Victoria distributes the Crimean Medal to 24 Riflemen (officers and men)—Capture of the Quarries—Attack on the Redan—Death of Lord Raglan—Thirteen Riflemen [xxi] shot down coming off picquet—Captain Balfour’s affair in the trenches—Final attack on Sebastopol—Captain Hammond—Explosion in French lines—The armistice—Reviews by French and Russian Generals—Embarkation for England—Corunna in 1809 and 1856—Both Battalions at Aldershot—Reviewed by the Queen—Formation of the 3rd Battalion—The 1st Battalion proceeds to Scotland—Fire and riots—2nd Battalion reviewed by the Queen in Hyde Park, when Her Majesty gave the Victoria Cross to eight Riflemen (officers and others)—Afterwards proceeds to Dublin—A 4th Battalion added to the Regiment | 298 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Sepoy Mutiny—2nd and 3rd Battalions embark for India—Woodford’s detachment arrives at Calcutta—March up the country—Arrival of Fyers’ detachment—Woodford’s party reach Cawnpore—Fight at the Pandoo Nuddee—Battle of November 27—Fyers’ march from Futtehpore to Cawnpore—Atherley’s company (3rd Battalion) reach Cawnpore—Battle of November 28—Death of Colonel Woodford—The Riflemen take two guns—Fight on November 29—Woodford’s body recovered and buried—Arrival of the 3rd Battalion at Calcutta—Marches up the country—Final battle of Cawnpore—Attack on the Subhadar’s tank—Arrival of the 2nd Battalion Head-quarters—Marches and expeditions—Capture of the fort of Etawah—Operations on the Ramgunga—Return to Cawnpore—Formation of the Oude field force—Expedition to intercept the Nana—Return re infectâ—Escorts—Advance towards Lucknow—The Riflemen join Outram’s force—Operations on the left bank of the Goomtee—First engagement there—Attack on a picquet of Riflemen—Capture of the Yellow Bungalow—Escort of mortars—Reconnaissance in force—The iron and stone bridges—Wilmot’s fight near the iron bridge—Deaths of Captain Thynne and Lieutenant Cooper—Capture of Lucknow—Expedition to Koorsie—Formation of the Camel Corps—Sickness in the 3rd Battalion—Fight at Baree—Expeditions—Pursuit of Beni Madhoo—March to Nuggur—Sufferings from the heat—Fight at Nuggur—Night panic—Pursuit of rebels—Camp at Chinhut—Night march to Nawabgunge—Sufferings of the Riflemen from fatigue, dust, and thirst—Battle of Nawabgunge—Sir Hope Grant’s opinion of the enemy—Shaw’s combat with a Ghazee—Casualties from wounds and sunstroke—Sir Hope Grant’s despatches | 347 |

| [xxii] | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Return of the 3rd Battalion to Lucknow—Distressing march of the 2nd Battalion to Sultanpore—Cross the Gogra—A company of the 3rd Battalion proceed to Sundeelah—Green’s fight at Jamo—Capture of Birwah—Death of Ensign Richards—Expedition to the fort of Amethie—March to Shunkerpore—Escape of Beni Madhoo—Expedition to Koilee—Fight near Hydergurh—Pursuit of rebels—Riflemen mounted on gun-limbers—Trans-Gogra campaign—March to Baraitch—Christmas dinner at Jeta—Skirmish near Churdah—Capture of Mejidia—Night march to Bankee—Fight at the Raptee—Renewed pursuit of Beni Madhoo—Capture of Oomria—March to Gonda—Expedition into Nepaul—Fight at Sidka Ghât—Expeditions near the Raptee—Fight at Akouna—Clearing the Jugdespore jungles—Patrols near the fords of the Raptee—End of the Mutiny—2nd Battalion return to Lucknow—Marches, services, and casualties of the 2nd Battalion—Inspection by Lord Clyde—3rd Battalion moves to Tulsipore to receive captured guns—Proceeds to Agra | 394 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Camel Corps—Riding drill—Move to Cawnpore—Proceed to join Sir Hugh Rose—Cross the Jumna—Battle of Goolowlee—Capture of Calpee—Return to Cawnpore—Move to Allahabad and Benares—Cross the Ganges—Expedition to Mohaneea—Standing camp at Kurroundea—Expedition to Nassreegunge; to Bikrumgunge; to Kochus—Fight at Sukreta—Various expeditions in pursuit of rebels—March to Fyzabad—Ordered to Lucknow—Pursuit of Tantia Topee—Capture of Tantia Topee—Camel Corps cross the Chumbul—March to Saugor—Operations in the jungles—Fight at Mitharden—Chase of rebels near Shahgurh—Move to Agra—Camel Corps broken up—Colonel Ross’ testimony to their zeal and discipline | 429 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

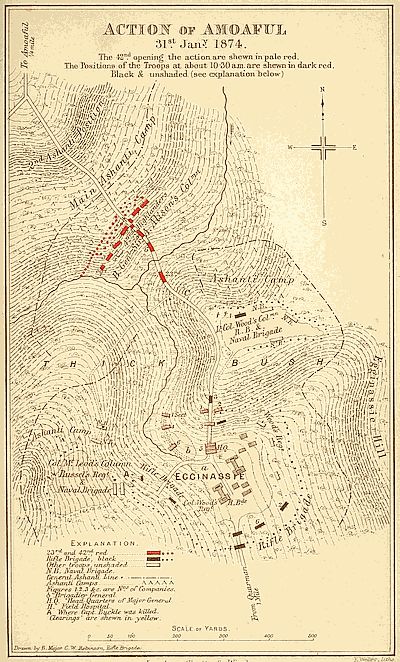

| Home service—1st Battalion inspected by Sir Harry Smith—His speech—4th Battalion embarks for Malta—Death of Sir Harry Smith—Marches in India—1st Battalion in Ireland—The Rifle Brigade exempted from being required to carry a colour on guards—The ‘Trent’ affair—Embarks for North America—Dangers of the voyage—Death of the Prince Consort—The designation ‘The Prince Consort’s Own’ granted to the Regiment—Journey from St. John’s New Brunswick to Rivière de Loup—Service abroad—Sir George Brown Colonel-in-Chief—Expedition against the Mohmunds—Battle of Shubkudder—Testimonies to the [xxiii] good conduct of the 1st Battalion in Canada—4th Battalion proceeds to Canada—Death of Sir George Brown—Bravery of two Riflemen—Fenian raid—Return of the 2nd and 4th Battalions to England—The Prince of Wales Colonel-in-Chief—Prince Arthur joins 1st Battalion as Lieutenant—Two Battalions at Aldershot—Flying columns—Return of the 1st Battalion to England—Autumn manœuvres—Return of the 3rd Battalion to England—Illness of H.R.H. the Colonel-in-Chief—Autumn manœuvres, 1872—Thanksgiving for the recovery of the Prince of Wales—2nd and 4th Battalions move to Ireland—Review before the Shah—Ashantee Expedition—2nd Battalion embarks for the Gold Coast—Autumn manœuvres of 1873—4th Battalion proceeds to India—Entry of the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh into London | 451 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Disembarkation at Cape Coast Castle—March to the Prah—Meeting with a supposed rhinoceros—African fever—Death of Captain Huyshe—Advance beyond the Prah—First contact with the Ashantees—Battle of Amoaful—Defence of Quarman—Advance from Amoaful—Fight near the Ordah—Crossing the river—Fight at Ordahsu—Advance to Coomassie—Return towards the coast—Aggemamu fortified—Arrival at Cape Coast and return to England—Reception at Portsmouth and Winchester—Reviews—2nd Battalion proceeds to Gibraltar—Death of Lieutenant-Colonel Nixon—The Colonel-in-Chief in India—The Duke of Connaught takes command of the 1st Battalion—Conclusion | 482 |

| APPENDIX I. | |

| Succession of Colonels-in-Chief and Colonels-Commandant | 513 |

| APPENDIX II. | |

| On the Armament of the Regiment | 515 |

| APPENDIX III. | |

| Actions and Casualties of the Regiment | 518 |

| APPENDIX IV. | |

| Rewards for Distinguished Service | 523 |

| INDEX | 529 |

⁂ I have not inserted plans of the Crimean actions, as accurate and detailed plans of these battles are to be found in Mr. Kinglake’s ‘Invasion of the Crimea,’ and in other works of the period, which are generally accessible.

[11] The position of the troops on this plan is that of November 27, 1857; but the plan will explain the actions on the other days.

Page 337, line 31: the name of the sergeant who distinguished himself is James Harrywood.

THE RIFLE BRIGADE.

Towards the close of the last century Colonel Coote Manningham and Lieutenant-Colonel the Honourable William Stewart addressed a representation to the Government, pointing out the importance of having a corps furnished with arms of precision, and the advantage of training such a corps in the special duties of Riflemen. It would have been interesting to preserve the text of this document; but I regret that it does not now exist. Every search has been made in the records of the War Department, by the kindness of Mr. Denham Robinson, of the War Office, but, I regret to say, without success; and it has been suggested that it may probably have been transferred to the Small Arms Department, and may have perished with the records of that office in the fire at the Tower of London in 1841.

However, in consequence of the suggestions it contained, the following Circular was issued to the commanding officers of fourteen regiments of infantry:—

Circular.

Horse Guards: January 17, 1800.

Addressed to Officers Commanding the 2nd Battalion Royals, the 21st, 23rd, 25th, 27th, 29th, 49th, 55th, 69th, 71st, 72nd, 79th, 85th, and 92nd Regiments.

Sir,—I have the honour to inform you that it is His Royal Highness the Commander-in-Chief’s[12] intention to form a corps of detachments from the different regiments of the line for the purpose of its being instructed in the use of the rifle, and in the system of exercise adopted by soldiers so armed. It is His Royal Highness’s pleasure that you shall select from the regiment under your command 2 sergeants, 2 corporals, and 30 private men for this duty, all of them being such men as appear most capable of receiving the above instructions, and most competent to the performance of the duty of Riflemen. These non-commissioned officers and privates are not to be considered as being drafted from their regiments, but merely as detached for the purpose above recited; they will continue to be borne on the strength of their regiments, and will be clothed by their respective colonels.

His Royal Highness desires you will recommend 1 captain, 1 lieutenant, and 1 ensign of the regiment under your command, who volunteer to serve in this corps of Riflemen, in order that His Royal Highness may select from the officers recommended from the regiments which furnish their quota on this occasion a sufficient number of officers for the Rifle Corps. These officers are to be considered as detached on duty from their respective regiments, and will share in all the promotion that occurs in them during their absence.

Eight drummers will be required to act as bugle-horns, and I request you will acquaint me, for the information of His Royal Highness, whether you have any in the — Regiment qualified to act as such, or of a capacity to be easily instructed.

I have, &c.

Harry Calvert.

A. G.

Thus we see that the Regiment was formed as a corps d’élite; and as regards the officers there was a double selection, eight of each rank of company officers being selected from the fourteen originally recommended.

The detachments so selected assembled at Horsham, in Sussex, in March 1800, and their first parade as ‘An Experimental Corps of Riflemen’ took place there on April 1 in that year; Lieutenant-Colonel the Honourable William Stewart being apparently in command.

The following is the Return of the state and strength of the Corps on this its first formation:

| Lieut.- Colonel | Captains | Lieut- enants | Ensigns | Sergeants | Drummers | Rank and file | |

| 1st Foot | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | |

| 21st ” | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||

| 23rd ” | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||||

| 25th ” | 1 | 2 | 32 | ||||

| 27th ” | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | |

| 29th ” | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||

| 49th ” | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | |

| 55th ” | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | |||

| 67th ” | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 69th ” | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||

| 71st ” | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | |||

| 72nd ” | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||

| 79th ” | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||

| 85th ” | 1 | 27 | |||||

| 92nd ” | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 32 | ||

| Total | 1 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 27 | 12 | 443 |

| Wanting to complete | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Establishment | 1 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 28 | 13 | 448 |

The Corps being now formed marched to a camp of exercise[3] at Swinley in Windsor Forest in May, and proceeded actively with their training as Riflemen. They are mentioned with great approbation by Mr. W. H. Fremantle in a letter, dated July 15, 1800, to the Marquis of Buckingham, as being ‘good, and much more useful’ than some other regiments then in that camp.[13] The camp broke up at the end of July, and at the request of Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart three companies of the corps (Captains Travers’,[14] Hamilton’s, and Gardner’s) were ordered to embark, under his command, with the expedition against the north coast of Spain, under Lieutenant-General Sir James Pulteney, Bart., and Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, K.B.

The expedition arrived before the harbour of Ferrol on August 25, and immediately commenced its disembarkation. This was effected without opposition in a small bay near Cape Prioriño; but on the troops proceeding to occupy a ridge of hills adjoining the bay, the Rifle Corps, which covered the advance, just as they gained the summit fell in with a party of the enemy which they drove back. In this skirmish Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart was dangerously wounded through the body. On the next morning, at daybreak, the position was attacked by a considerable body of the enemy, who were repulsed with much loss, and the English troops remained in complete possession of the heights. But in this action Captains Travers and Hamilton, and Lieutenant Edmonston, attached to the Rifle Corps, and eight rank and file were wounded. Sir James Pulteney being, however, of opinion that Ferrol could not be taken, or the ground he occupied be held, re-embarked the troops.[15] It was subsequently stated in the House of Lords that at the very moment he did so the proper officer was on his way with the keys of the place, to surrender it. And Mr. Ford affirms that ‘had the expedition sailed boldly up to the Ferrol, the Gallicians were only waiting to surrender, being, as usual, absolutely without means of defence.’ He attributes the failure to the combined indecision of the leaders.[16]

Of this, the first affair in which the Regiment was engaged, it may be observed that it has the high honour of having shed its first blood before its actual embodiment, and while it consisted only of detachments experimentally assembled for instruction. It was the only corps engaged on the day of disembarkation, and (with the exception of one officer of the 52nd) the only officers wounded were attached to it. August 25, the day on which it was first engaged, was the date of the commissions of its first officers when it was formally embodied.

The expedition then proceeded to Malta; and an order was issued by the Commander-in-Chief for all officers and men of the Rifle Corps, whose regiments formed part of the expedition, to rejoin them, and for those whose regiments were not so employed to be attached to corps serving with the expedition.

Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart, Captain Travers, and Lieutenant Edmonston returned to England.

The Rifle Corps was immediately re-formed, principally from detachments of fencible regiments serving in Ireland, and I presume also, on the return of the expedition, from the men originally selected as Riflemen. These detachments began to assemble at Blatchington in Sussex, near Lewes, about the end of August, and continued to join during the autumn. The whole of the officers who had been attached to the experimental corps were appointed to it; their commissions being ante-dated, as I have observed, to August 25, the anniversary of which has been since observed as the foundation-day of the Regiment. A second lieutenant-colonel and two majors were appointed, and some others were added to complete the Corps to eight companies, with a captain and two subalterns to each. The establishment was, therefore, on December 25, returned as follows:

| Colonel | 1 |

| Lieut.-Colonels | 2 |

| Majors | 2 |

| Captains | 8 |

| First Lieutenants | 8 |

| Second Lieutenants | 8 |

| Paymaster | 1 |

| Adjutant | 1 |

| Quarter-Master | 1 |

| Surgeon | 1 |

| Assistant Surgeon | 1 |

| Staff-Sergeants | 5 |

| Sergeants | 40 |

| Buglers | 18 |

| Corporals | 40 |

| Privates | 760 |

The officers on its formation were:

| Robert Travers. | Thomas Sidney Beckwith. |

| Cornelius Cuyler. | Timothy Hamilton. |

| Thomas Christopher Gardner. | Alexander Stewart. |

| Henry Shepherd. |

| Blois Lynch. | John Ross. |

| J. A. Grant. | Edward Bedwell Law. |

| John Stuart. | Henry Powell. |

| Peter O’Hare. | William Cotter. |

| Thomas Stirling Edmonston. | John Cameron. |

| Robert Duncan. | —— Douglas. |

| Alexander Clarke. | L. H. Bennet. |

| Niel Campbell. |

| Henry Goode. | Patrick Turner. |

| James Macdonald. | Samuel Mitchel. |

| Thomas Brereton. | George Elder. |

| Loftus Gray. | James Pendergast. |

| John Jenkins. | John Burton. |

The Regiment, as it has existed since, and as it has won lasting renown in so many fields, as ‘a Corps of Riflemen,’ ‘the Rifle Corps,’[17] ‘the 95th,’ and ‘the Rifle Brigade,’ was then and thus organised under Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart. For though Manningham was the colonel, and justly shares the honour of its formation, he seems seldom to have been present with it; for he was equerry to George III., and often at Court.

William Stewart was the fourth son of John, seventh Earl of Galloway, and at the early age of thirteen was appointed Ensign in the 42nd Regiment; but subsequently served in the 22nd and 67th, and with the former had seen service at the capture of the French West India Islands in 1793. We have seen that it was owing to Manningham’s and his suggestions that the Rifle Corps was formed; and after its embodiment he also addressed a long letter to the Adjutant-General on the discipline and internal economy of such a corps. His recommendations (which were adopted) were: that it should first be formed of volunteers from infantry battalions which best could spare them, and by men from the undrafted part of the Irish militia; and he added the (rather singular) opinion that Irishmen were preferable for Riflemen, as ‘perhaps from being less spoiled and more hardy than British soldiers, better calculated for light troops.’[18]

He now set himself vigorously to organise and discipline the Corps thus formed at his suggestions. The standing orders of the Regiment, which, though issued of course in Manningham’s name, were probably principally compiled by Stewart, testify not only to his capability for organising and disciplining it, but in a most remarkable way to his pre-eminence above and beyond the military ideas of his time. The germs, if not, indeed, the actual existence of most of the late improvements for the training and advantage of the soldier are found in these orders. The good-conduct medal; the medals for acts of valour in the field; the attention given and the methods adopted to secure accurate shooting, dividing men into classes according to their practice at the target, and instituting a class of Marksmen; the rules for a regimental[7] school, and for periodical examination of its scholars; the institution of a library; the provision for lectures on military subjects, tactics and outpost duties; the encouragement of athletic exercises; these and many other plans, carried out in the British army only after the middle of the nineteenth century, are inculcated in the original standing orders, and were adopted in the Regiment from its formation.[19]

Sir Charles Napier, who was appointed to a lieutenancy in the Rifle Corps, December 25, 1800, and joined it at Blatchington, in his letters to his family, bears high testimony to Stewart’s ability in organising the Corps; though he seems not to have liked him, and eventually to have quarrelled with him. ‘Stewart makes it a rule to strike at the heads. With him the field-officers must first be steady, and then he goes downwards: hence the privates say: “We had better look sharp if he is so strict with the officers.”’[20]

In 1801 Colonel Stewart was selected to command the troops (the 49th Regiment and a company of the Rifle Corps) ordered to embark on board the fleet commanded by Admiral Sir Hyde Parker. And on February 28 Captain Beckwith’s[21] company, consisting of 1 captain, 2 first lieutenants, 1 second lieutenant, 5 sergeants, 2 buglers, 1 armourer, and 101 rank and file, embarked at Portsmouth on board H.M.S. ‘St. George,’ bearing the flag of Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson. On arrival in Yarmouth Roads the right platoon of Captain Beckwith’s Riflemen was shifted to the ‘London,’ Sir Hyde Parker’s flag-ship. But the men of the Rifle Corps seem to have been distributed, on arrival in the Baltic, among the ships of Nelson’s squadron, which on April 2 attacked and reduced the Danish fleet at Copenhagen.

In this action First Lieutenant and Adjutant Grant was killed ‘whilst gallantly fighting the quarter-deck guns of H.M.S. “Isis.”’ He was the first officer of the Regiment killed in action. He had volunteered for this service. His head was taken off by a cannon-ball as clean as if severed by[8] a scimitar. Stewart recommended Second Lieutenant Pendergast, who was in the expedition, for the vacancy, and he was accordingly promoted on May 9. Two rank and file were also killed; and 1 sergeant and 5 rank and file wounded, of whom some subsequently died of their wounds.[22]

Lord Nelson, in his despatch, says: ‘The Honourable Colonel Stewart did me the favour to be on board the “Elephant;” and himself, with every officer and soldier under his orders, shared with pleasure the toils and dangers of the day.’

It is said in the Record of the 1st Battalion that ‘an appropriate medal was issued upon this occasion by Admiral Lord Nelson to the non-commissioned officers and several soldiers.’ I have not been able to find any trace of this medal, which does not seem to have been given to the officers. For it appears from a correspondence between Stewart (then Lieutenant-General Sir William Stewart), Earl St. Vincent, and Lord Sidmouth in 1821–2, that Nelson had been desirous of obtaining a medal for the captains of his squadron who were engaged at Copenhagen, and had recommended Stewart for one; but that Lords St. Vincent and Sidmouth opposed the issue of any such medal, on the ground that it would be a very invidious distinction from those captains who, being with Parker’s fleet, were not engaged. Stewart advanced a request for this medal in 1821, on the plea that, being a military man, his case was essentially different from that of the captains. But though his application was then supported by Earl St. Vincent, it was refused (in very flattering terms however) by Lord Sidmouth.[23]

The Regiment marched to Weymouth in the early part of the summer, and was encamped there. Their being near Windsor the year before, and now at Weymouth, the[9] summer residence of George III., was probably due to Manningham’s being attached to the person of that sovereign. They returned to Blatchington barracks in the autumn.

On June 25 the establishment of the Corps was again changed, and companies were given to the field-officers, as was then the case in line regiments. But this arrangement was of short duration, for on March 27 following field-officers’ companies were abolished, and effective captains were appointed in their place.

In the autumn of 1802 the Regiment marched to Chatham. On this march, at Maidstone, some of the men broke open the plate-chest of the officers’ mess. One of the offenders was discovered, and being tried by court-martial, was sentenced to receive 800 lashes, the whole of which were inflicted at one time.

The Regiment appears, even at this early period, to have been a favourite one with volunteers from the line and militia; and Surtees mentions four men in the ranks who had been commissioned officers; one of whom, indeed, was drawing half-pay, and was eventually recalled to full pay as lieutenant.

After a short stay at Chatham, the Regiment was moved for the winter to Shorncliffe and forts in the vicinity.

On December 25, 1802, the Rifle Corps was ordered to be numbered as the 95th Regiment, and thus assumed the name under which it was long known, and which its services on the continent of Europe made famous.

In May 1803, the head-quarters, with five companies, returned to their old quarters at Blatchington, and in November moved to Colchester, and eventually to Warley and Woodbridge barracks; the other five companies, under Colonel Beckwith, remaining during the summer at Shorncliffe, where, on Colonel Stewart’s promotion to Brigadier-General and command of a district, the head-quarters and other five companies joined them. Here they formed part of that camp of instruction under Sir John Moore, the marvellous results of which have been so truly and eloquently described by Sir William Napier;[24] and here they first met and were brigaded with their compeers, the 43rd and 52nd, in united action with whom, as the Light Division in the Peninsula, so many of their laurels were won.

During the time the Regiment was encamped at Shorncliffe, Colonel Manningham, carrying out the intentions of his own standing orders, delivered a course of lectures on the duties of Riflemen in active service, which he published.[25]

On the breaking up of that camp, the Regiment moved into Hythe barracks till April 1805, when it appears to have returned to Shorncliffe.

On May 6, 1805, the 2nd Battalion was formed by the transfer of 21 sergeants, 20 corporals, 7 buglers, and 250 privates from the original Corps (now the 1st Battalion); the remainder of the proposed establishment being made up by volunteers from the militia; 1 major (Gardner), 6 captains and 3 first lieutenants being promoted from the 1st Battalion, which also supplied the adjutant. The command and formation of the Battalion was conferred on Wade,[26] of the 1st Battalion, who was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel; and so vigorously did he proceed in its organisation, that in less than three months it wanted only 7 sergeants,[11] 6 buglers, and 98 privates to complete its full strength. It was formed at Canterbury, but moved to Brabourn Lees, near Ashford, in June, where it was brigaded with the 1st Battalion.

It was while the two Battalions were stationed at Brabourn Lees that a singular instance of self-control and magnanimity was shown by Sidney Beckwith, then commanding the 1st Battalion. Some men, volunteers from the Irish militia, meeting Mrs. Beckwith, with her child and nurse, on the Ashford Road, most grossly insulted them, proceeding to such lengths (Surtees says) as delicacy forbids to mention. The culprits were discovered, but not punished; for Beckwith next day on parade forming the Battalion into square, addressed them; and, after relating the outrage, added: ‘Although I know who the ruffians are, I will not proceed any further in the business because it was my own wife whom they attacked; but had it been the wife of the meanest soldier in the Regiment, I solemnly declare I would have given the offenders every lash to which a Court-Martial might have sentenced them.’ It is no wonder that by such acts of generosity, as well as by his leading them in the field, this man ‘won the heart of every soldier in the Battalion;’ as Surtees tells us, who served in the ranks under him.

So rapidly and effectually had the 2nd Battalion been organised, that it was in September of this year ordered on service; the right wing being marched to Dover to embark for the Continent, and the left wing to Winchester, to prepare to embark for the Mediterranean. However, it was subsequently countermanded; the right wing, from Dover, being marched to Hailsham in October, and the left from Winchester to Eastbourne; and both in November assembled at Bexhill, where they were quartered till March 1806.

In October 1805 the head-quarters and five companies of the 1st Battalion, under Beckwith, marched to Deal, and embarked at Ramsgate for Germany, in the expedition commanded by Lord Cathcart. After a stormy passage, in which some part of the Battalion seems to have been in great danger from the misconduct of the master of a transport,[27] they reached the Elbe in November, and on the 18th disembarked at Cuxhaven, and marched at once for Dorum, a village twelve or[12] fourteen miles distant, and proceeded by Osterholz and Bremerlehe to Bremen, the Riflemen forming the advanced guard. On their arrival before Bremen on the 24th, the barriers were shut, and the commandant of the Prussian garrison refused to let the troops enter; the Senate of Bremen also demurring to General Don’s request for a passage through the place, on account of its neutrality. However, Beckwith, who commanded the advanced corps, was not the man to be daunted by such refusals. He accordingly informed the Prussian commandant that unless his corps was admitted he should force an entrance. This he did on the morning of the 26th, opening the barriers by force, apparently without any armed resistance; and the refusal of the Senate seems to have been prompted rather by coyness than dislike, for the authorities of the town and the inhabitants generally received the advanced guard with expressions of friendship and satisfaction, the Prussian garrison alone looking on these tokens of welcome with great dissatisfaction. The Riflemen passed on, still in advance, to Delmenhorst, a Prussian regiment accompanying them through the city and across the bridge over the Weser, in order to guard their magazine of corn at Bremen for the use of their army on the Weser. From Delmenhorst the Riflemen were detached: three companies at Oldenburg, and two, under Major Robert Travers, at Wildeshausen, on outpost duty. These last were soon moved back to Delmenhorst, and shortly after reunited to the other three companies at Oldenburg. Here they were welcomed and entertained by the inhabitants, and by none more than by the reigning Grand-Duke of Oldenburg, who became extremely fond of the Regiment, officers and men. In consequence of the battle of Austerlitz in December, and the powerful armies set free by that event, and by Mack’s surrender of Ulm, to act against us in the North of Europe, the outposts were withdrawn to Delmenhorst, and eventually into Bremen; and on their march from Oldenburg the Duke sent forward plentiful refreshments for the Riflemen, both officers and men.

They continued at Bremen till February 1806, when the army moved towards a place of embarkation, Beckwith’s force covering the retreat; but as great numbers of the Germans, who formed part of the British army there, were[13] deserting, the 95th were directed to remain in the villages in order to intercept them. However, eventually Beckwith’s Riflemen also retreated, and embarking at Cuxhaven, arrived and landed at Yarmouth on the 19th; thence they marched, by Lowestoft, to Woodbridge barracks, where they rejoined the remainder of the Battalion. During this abortive expedition they had never, I believe, been engaged with the enemy.

From Woodbridge the Battalion marched, in the spring of 1806, to Deal, and afterwards to quarters at Ospringe and Faversham, where they joined the 2nd Battalion, which had moved there from Bexhill.

On June 13 three companies of the 2nd Battalion (Captains Macdonald’s, Elder’s, and Dickenson’s), under the command of Major Gardner, marched from Faversham and embarked at Portsmouth, as part of the force under Sir Samuel Auchmuty, destined for service in South America. The transports in which the troops were embarked were in such bad condition that they were obliged to put into Rio; and it was not until January 16, 1807, that a landing was effected at Maldonado, near the mouth of the river La Plata. This operation was not accomplished without opposition, in which one bugler was killed and Lieutenant Chawner wounded. The General moved forward and occupied the suburbs of Monte Video, with a view to investing the place. On the morning of the 20th the enemy made a sortie, and attacked our troops with a force of 6,000 men. They advanced in two columns, one of which pressed our picquet so hard, that Colonel Gore Browne, of the 40th, who commanded the left of our line, ordered up three companies of that regiment in support. These companies fell in with the head of the enemy’s column and very bravely charged it. The charge was as bravely received, and great numbers fell on both sides. At length the column began to give way, when it was suddenly and impetuously attacked in flank by the Riflemen and by a light battalion which Auchmuty had ordered up. The column then gave way on all sides, and was pursued with great slaughter to the town. The other column, observing the fate of their companions, retired without coming into action. In this sortie the Riflemen lost 5 men killed and 25 wounded.

A breach having been effected, Auchmuty resolved to[14] assault the place; and an hour before daybreak on the morning of February 3 the attacking column moved forward. It was headed by the Riflemen under Gardner; the storming party being led by Captain Dickenson at the head of his own company. They got near the walls before they were discovered, when a destructive fire was opened from every gun that could bear on the column and from the musketry of the garrison. The enemy had piled up hides in the breach; and unfortunately, in the darkness, its situation was not immediately discovered, and the troops remained under a heavy fire for a quarter of an hour. At last the breach was discovered and pointed out by Captain Renny, of the 40th (which formed part of the attacking column), who fell in the assault. Our troops at once mounted it, led by Dickenson and the Riflemen, and forced their way into the town; and though cannon placed at the head of all the principal streets opened a destructive fire, the place was taken and occupied.

In this gallant affair Dickenson fell gloriously at the head of his company; 10 rank and file were killed, and Lieutenants Scanlan and Macnamara, 4 sergeants, and 15 rank and file were wounded. The Riflemen engaged were specially thanked in General Orders; and eleven sergeants received silver medals under the sanction of the Duke of York, Commander-in-Chief, for their gallantry on this occasion.

The three companies under Gardner remained in La Plata until they were joined in May by a wing of the 1st Battalion.

This force, consisting of five companies (Norcott’s,[28] O’Hare’s,[29] Jenkinson’s, Ramage’s, and Bennett’s), under the command of Majors M’Leod and Travers, and numbering 25 sergeants and 370 rank and file, marched from Faversham on July 23, 1806, and embarked at Gravesend on the 26th on board the ‘Chapman,’ armed transport. Their voyage was a slow one. They sailed on the 27th, remained at anchor in the Downs from the 30th till August 4, arrived on the 21st in Plymouth Sound, were disembarked on September 2, and encamped on Buckland Down till the 13th, when they re-embarked, Norcott’s and Bennett’s companies being placed[15] on board the ‘Alexander’ transport. They did not sail, however, till October 6, and then only to Falmouth; the other ship, with the head-quarters, having preceded them on September 28.

On October 24, Brigadier-General Robert Craufurd (under whom the Regiment served subsequently so long and so gloriously in other fields) arrived at Falmouth and took command of the troops assembled in that harbour for (as it was then called) ‘the remote expedition.’

It sailed on November 12, and arrived in Porto Praza Bay, in the island of St. Jago (Cape Verde) on December 14. Here Craufurd, with the zeal for discipline which always distinguished him, minutely inspected the troops forming the expedition, on board the several transports. The companies of the 95th were frequently landed for exercise during their stay at this island. They sailed from St. Jago on January 11, 1807, and anchored in Simon’s Bay, Cape of Good Hope, on March 14, and in Table Bay on the 20th.

Here General Craufurd received instructions to proceed, not to the coast of Chili, to which the expedition was originally destined, but to the river La Plata to join the force under Sir Samuel Auchmuty. The troops therefore sailed on April 6, and arrived at St. Helena on the 21st; sailed again on the 26th, and anchored in the river La Plata on the 27th. They were not, however, disembarked; and on June 4 a most violent gale drove the ships out to sea, and they did not reach Monte Video till the 14th. Every preparation having been completed for the service on which it was about to be employed, the expedition, comprising the troops under General Craufurd and those already at Monte Video under Sir Samuel Auchmuty, sailed on June 17. General Whitelocke had been appointed to command the whole force, most unfortunately, as the event proved, and assumed his command at Monte Video. On the 27th they arrived at Ensenada de Barragon, about thirty miles to the eastward of Buenos Ayres, where they disembarked on the morning of the 28th, at nine o’clock.[30] After some fatiguing marches through a country much intersected by swamps and muddy rivulets, the army reached Reduction, a village nine miles distant[16] from the bridge over the Rio Chuello, on the opposite bank of which the enemy had constructed a formidable line of defence. The General resolved to cross the river higher up and to turn this position. On the evening of July 2, the light division of General Gower’s column crossed at the ford of Passo Chico; the Chuello was about waist-deep, and the Riflemen carried their pouches on their shoulders. They were soon seriously engaged with the enemy. They charged rapidly, and overthrew their opponents in a few minutes, with great loss, taking twelve guns. In this affair Major Travers and the officers and men of both Battalions serving with this force greatly distinguished themselves. One sergeant and 1 private of the 1st Battalion were killed, and 2 sergeants and 10 rank and file wounded; and 1 private of the 2nd Battalion was killed, and Captain Elder and 10 rank and file wounded.[31]

The left column, with the Commander of the Forces, united with that under Major-General Gower in the suburbs of Buenos Ayres on the afternoon of July 3, and the whole army was placed in position. Two companies of the 1st Battalion, under Major Norcott, were immediately detached to occupy an advanced post, and became warmly engaged until dark; by which time they had completely dislodged a very superior force of the enemy from every point in their front which they were ordered to occupy.

On the morning of the 4th this picquet was furiously attacked by several hundreds of the enemy, whose continued exertions to dislodge it proved fruitless. Major M’Leod joined the post about the middle of the day, and distinguished himself by his gallantry and judicious arrangements. This affair lasted until dusk, and our loss amounted to 2 officers (Lieutenants James Coane and Charles Noble) severely wounded, 1 sergeant and 1 rank and file killed, and 2 sergeants and 2 rank and file wounded. The two companies were relieved at night by a detachment of the 36th, and joined the army in its position.

Orders were received during the early part of the night for the attack of the town at daylight on the 5th. The five companies of the 1st Battalion formed a part of the column of attack under Brigadier-General Craufurd and Lieutenant-Colonel Packe, leaving one company as an advanced guard to each division, supported by a light company. Major Travers commanded the advance of the right column and Major Norcott that of the left.

The companies of the 2nd Battalion seem to have been attached to Sir Samuel Auchmuty’s division, the light battalion of which was divided into wings, each followed by a party of the 95th. These troops were all unloaded, and were directed not to fire until the columns had reached their final points and formed.

At the appointed signal the troops were in motion. The right column proceeded down the line of street it was directed to take, until it nearly reached the river; when, turning to the left, with the view of making for the Franciscan Convent and taking possession of it, it was assailed from the parapets and windows of every house along the whole street in so vigorous a manner as to render it impossible to penetrate further without the probable loss of every officer and man. Orders were at this moment given to retire; and General Craufurd took post in the great Convent of St. Domingo, occupying as many houses as his means enabled him to break into, on the flat parapetted tops of which the troops formed. Every possible effort was made to assail the enemy from all parts of the Convent, but without success; for those points which the men were enabled to reach were mostly commanded by the neighbouring houses on one side, which the Riflemen had not been able to force open, and from which fire they suffered dreadfully. With the exception of the operations of the force under Sir Samuel Auchmuty, and of the 45th Regiment, every point of attack failed.

The capture of the 88th Regiment, together with the Light Brigade under Lieutenant-Colonels Packe and Cadogan, and the immense loss of killed and wounded, furnished the enemy with such powerful means of attack that at three o’clock he had dislodged our force from every house they occupied, and confined our operations entirely to one or two[18] points of the Convent. The loss of officers and men at this time increased most considerably. Every effort was made to preserve the posts; but, finding his troops deprived of all means of succour, or prospect of success in holding out, having ascertained the fate of the neighbouring columns, and further resistance proving quite useless, the Brigadier surrendered with his column at four o’clock in the afternoon, and the officers and men were immediately marched as prisoners to the citadel and other buildings. Major M’Leod, of the 95th, however, on Craufurd consulting the field-officers in the Convent, was the only one who demurred to the necessity of surrendering. But when Craufurd offered, if M’Leod was decidedly of opinion that they could force their way out, to head the column with him, he declined the responsibility.[32]

The left column moved as directed until it came in view of the river; it had scarcely approached the Franciscan Convent when, by an almost invisible fire, it lost nearly half its officers and men. Finding it impossible to penetrate to the objects of attack, Lieutenant-Colonel Packe acceded to Lieutenant-Colonel Cadogan’s taking possession of some houses. This was effected, and they were afterwards defended to the last extremity by that officer and Major Travers; but they were at length compelled to surrender, having suffered most severely in killed and wounded, and all chance of further resistance being deemed useless on account of the capture of the column on their left. Nothing could exceed the persevering gallantry and conduct of every officer and man of the Regiment engaged on this unfortunate day.[33]

The loss of the five companies of the 1st Battalion was Captain Jenkinson, 2 sergeants, 2 buglers, and 36 rank and file, killed; Captain O’Hare, Lieutenants Cadoux, Macleod, and Turner,[34] wounded severely; Majors Travers and M’Leod, and Lieutenant M’Cullock, wounded slightly; and[19] 8 sergeants, 2 buglers, and 73 rank and file wounded; and 2 sergeants, 2 buglers, and 39 rank and file missing.

Of the three companies of the 2nd Battalion the loss was 3 sergeants, 1 bugler, and 46 rank and file killed; and Lieutenants Hill[35] and Scott, 6 sergeants, and 40 rank and file wounded.

In consequence of the treaty which had been concluded on the 7th, the prisoners were released on the morning of the 8th July, and joined the different posts occupied by the army.

Every arrangement having been completed for the evacuation of the country on the south side of the river La Plata, the army was embarked by the 12th, sailed on the 13th, and anchored at Monte Video on the 15th.

On August 8 the five companies of the 1st Battalion sailed for England, and arrived at Falmouth on November 9. They proceeded to Dover by sea about the end of January, 1808, whence they marched to Shorncliffe barracks, and soon after to Colchester to join the other five companies of the Battalion, to which station they had moved after their return from Germany.[36]

The three companies of the 2nd Battalion embarked also, under Major Gardner, on July 12th. They landed at Portsmouth on December 2, and joined the Battalion at Hythe on the 18th.

But we must return to the companies of both Battalions which remained in England. In July, 1807, five companies of the 1st Battalion, under Colonel Beckwith, and five companies of the 2nd Battalion, under Colonel Wade, embarked at Deal with the expedition to Denmark under Lord Cathcart. They arrived in the Sound on August 18, and disembarked at Veldbeck, about ten or twelve miles from Copenhagen, on the 16th. Immediately on landing, the Riflemen of both Battalions were sent on in advance towards Copenhagen. And here first they served under the immediate command of the great chief, who commanded the advance; under whose eye they were so often to fight; whose praise they were so[20] often to receive: their future Colonel, then Major-General Sir Arthur Wellesley.

To this march no opposition was offered by the enemy; a small patrol of cavalry appeared in their front, but retired on the approach of the Riflemen. They halted for the night at Lingbye, rested on their arms all night, and early next morning again advanced, and about mid-day took up a position within a long gunshot of Copenhagen, and invested the place.

About three o’clock on that day (August 17) a considerable body of the enemy advanced from the town and attacked the picquets on the left of the line towards the seashore. This small force, consisting of four companies of the 2nd Battalion and six of two line regiments, in all not more than 1,000 men with two light field-pieces, were opposed to about 3,000 of the enemy. But almost as soon as they came in contact the Danes gave way and retired into the town, leaving a good many dead and wounded. The detachment of the 2nd Battalion lost 1 man killed, and 2 men were wounded.

On the 19th the 2nd Battalion was moved further to the right, and nearer to the town; and from this day till the 24th a constant fire was kept up between the advanced posts and the place; by which, however, no loss seems to have been inflicted on the Riflemen. On the 24th they were under arms at two o’clock in the morning, and immediately advanced, driving in the Danish outposts; in this operation they encountered considerable opposition, and had some skirmishing among the gardens and suburbs. During the 25th a constant fire both of artillery and small arms was kept up from the place, by which a battalion of the German Legion suffered rather severely. They were relieved on outpost duty a little before dark by the 2nd Battalion, who did not lose a man at this post. On the 26th a division was formed, under Sir Arthur Wellesley, to which the two Battalions of the 95th were attached; and they were ordered to proceed into the interior to disperse a large body of militia and armed peasantry. They marched about three P.M., and made their way through the country on the left of the great road to Roeskild. They halted that night at Cagstrup; and next morning continued to advance towards Kioge, halting in the evening at a village near Roeskild. The troops were now, or just previously,[21] formed into two brigades, the five companies of the 1st Battalion being attached to that under the immediate command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, and those of the 2nd Battalion to General Baron Linsingen’s brigade.

On the 29th Sir Arthur Wellesley attacked the Danish army, which was established in position on the north side of the town and rivulet of Kioge. He sent round Baron Linsingen’s brigade to cross the rivulet at Salbye and fall upon the enemy’s left flank, while Sir Arthur himself advanced on his front, covered by the 1st Battalion skirmishers. The enemy gave way at once before an attack by the 92nd, and retreated in disorder, ‘followed in the most gallant style by the 1st Battalion of the 95th,’[37] and eventually by the whole infantry. Major-General Oxholm, the second in command of the Danish army, attempted to make a stand with the rear-guard in the village of Hervolge, but was briskly attacked by some German hussars and a company of the 2nd Battalion; and though he took up a strong position in the churchyard, which was considerably higher than any other part of the village, he was, after a short resistance, compelled to surrender with several officers and about 400 men. In this action at Kioge the loss suffered by the 95th appears to have been inconsiderable; no mention of casualties appears in the 2nd Battalion Record; Sir Arthur Wellesley says that ‘a few men of the 95th fell.’[38] They must have belonged to the 1st Battalion. The conduct and steadiness of the 1st Battalion of the 95th, under Colonel Beckwith, are ‘mentioned particularly’ in Sir Arthur Wellesley’s despatch.[39]

The two Battalions were engaged all the remainder of the 29th and during the 30th in scouring the woods near Kioge, in order to complete the dispersion of the Danish force and to prevent its reassembling. They reached Ringstæd on the 31st; and as the regular portion of the troops of the enemy had retired into one of the islands, and the militia had entirely disbanded itself, they halted here till after the surrender of[22] Copenhagen on September 7. But during this halt detachments were occasionally sent out to search for and disperse any lurking parties of the enemy, and to bring in arms or stores. One of these detachments, consisting of 100 men of the 2nd Battalion, mounted in light German waggons, scoured a considerable tract of country, and took possession of ten guns of small calibre, forty rifles, and a number of muskets.

The terms of the capitulation of Copenhagen extended only to the British and Danish forces in the Island of Zealand, and the troops were, therefore, still liable to attack from any Danish force which might be reassembled on the mainland or in the other islands. Strong outposts were therefore established in the towns and villages along the Belt, and the two Rifle Battalions were employed on this service; the 1st Battalion occupying Callundborg, Slagelse, Corsoer, and Skielskior; and the 2nd Battalion, Nestved, Lundbye, Wordingborg, and Præstoe. They remained in their cantonments till October 15, when they retired towards Copenhagen, which they reached on the 17th. The two Battalions embarked on board the ‘Princess Caroline,’ 74, a Danish prize, sailed on the 21st, arrived in Yarmouth Roads in November, and (after a stormy passage) at Dover on the 15th, landed next day at Deal, and joined their Battalions at Hythe.[40]

On April 8, 1808, three companies of the 1st Battalion (Major Norcott’s, Captains Ross’[41] and O’Hare’s), under the command of Major Gilmour, marched to Harwich, embarked the next day, sailed the following day, and joined the troops assembled in Yarmouth Roads destined for the Baltic, under Sir John Moore, to co-operate with Sweden. They arrived at Gottenburg on May 17, but owing to misunderstandings with the King of Sweden they never landed; and having remained on board their transports nearly ten weeks, they sailed at the latter end of July, and eventually landed in Portugal, at Peniche, at the end of August, and formed a junction with the force under Sir Arthur Wellesley.

But previously to their arrival there, two companies from those of the Battalion remaining in England (Captains[23] Cameron’s[42] and Ramage’s), under Colonel Beckwith, embarked at Harwich early in July. The strength of this detachment was about 180 men;[43] these landed on August 19, a few days before Major Gilmour’s force, which was immediately united to it.

About the same time four companies of the 2nd Battalion, under the command of Major Robert Travers, had embarked at Dover on June 8, and formed part of the force destined for Portugal under Sir Arthur Wellesley. The transports assembled in Cork harbour early in July. The strength of the detachment of the 2nd Battalion was 1 field-officer, 4 captains, 13 subalterns, 1 staff, 20 sergeants, 8 buglers, and 399 rank and file.[44] These disembarked at Figueira, in Mondego Bay, on August 1, 1808.

These four 2nd Battalion companies were attached to General Fane’s brigade; and, immediately after disembarkation, pushed on, keeping their right towards the sea, several miles over an unbroken plain of white sand. The men, who had been many weeks on board ship, were much fatigued by this their first day’s march, as the weather was hot, and the sand so loose that they sank ankle-deep every step. They encamped at night near the village of Lavaos, to which the rest of the army moved up as soon as they disembarked. On August 9, these companies, forming part of the advance, marched from Lavaos about three o’clock in the morning. Their destination was Leiria, and their orders were, if the enemy were in strength at Leiria not to drive him out till the 10th, but to halt in the pine-woods which cover the country between Lavaos and Leiria. And General Hill was ordered to let 200 Riflemen and a few dragoons feel their way into Leiria, and if they obtained possession to support them with his whole corps.[45] However, the French had evacuated Leiria before the Riflemen entered it, and it bore terrible marks of their cruelty and excesses.

The army marched hence towards Lisbon, the Riflemen still forming the advance, and daily expecting to fall in with the enemy, who were gradually retiring before them. The first meeting took place at Obidos on the evening of August 15, where, after a long march, a party of French[24] cavalry and infantry were found. These were immediately attacked by the Riflemen under Major Travers, together with some of the 60th, and forced to retire. In the eagerness of this first encounter the pursuit was continued too far, and the Riflemen pushed on to a distance of three miles from Obidos, and quite away from any support. They were then attacked by a superior body of the enemy, who attempted to cut them off from the main body of the detachment to which they belonged, which now advanced to their support. Larger bodies of the enemy appeared on both flanks, and it was with some difficulty that General Spencer, who had gone out to Obidos, when he heard that the Riflemen had advanced, was able to extricate them.[46] In this sharp skirmish Lieutenant Bunbury and 2 men were killed, and Captain Pakenham[47] and 6 men wounded. Ralph Bunbury was the first English officer who fell in the Peninsula. Harris says that he was ‘the first man that was hit;’ and he was much regretted by his brother officers. It is painful to add that this first blood was spilt, in Sir Arthur Wellesley’s opinion, unnecessarily. ‘The affair,’ he writes to Lord Castlereagh, ‘was unpleasant, because it was quite useless; and was occasioned solely by the imprudence of the officer and the dash and eagerness of the men; they behaved remarkably well, and did some execution with their rifles.’[48] And to the Duke of Richmond he says, ‘that it was foolishly brought on by the over-eagerness of the Riflemen in the pursuit of an enemy’s picquet; the troops behaved remarkably well, but not with great prudence.’[49]

They held possession that night of an extensive knoll near the road by which the enemy had retired, and were under arms till morning, when they occupied the village of Obidos till the morning of the 17th.