J. Webber del. I. Andrews. Sc.

A Hawaiian Chief.

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/kianatradition00jarvrich |

J. Webber del. I. Andrews. Sc.

A Hawaiian Chief.

KIANA:

A TRADITION OF HAWAII.

BY

JAMES J. JARVES,

Author of “History of the Hawaiian Islands,” “Parisian” and “Italian Sights,”

“Art-Hints,” &c., &c.

BOSTON AND CAMBRIDGE:

JAMES MUNROE AND COMPANY.

LONDON:

S. LOW, SON, AND COMPANY,

Ludgate Hill.

M DCCC LVII.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1857, by

James Munroe and Company,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

CAMBRIDGE:

THURSTON AND TORRY, PRINTERS.

TO

HIS MAJESTY

ALEXANDER LIHOLIHO,

WHO NOW SO WORTHILY FILLS THE THRONE OF THE

HAWAIIAN ISLANDS,

AS

KAMEHAMEHA IV.,

THIS TRADITION OF HIS KINGDOM IS

RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED.

Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as Fiction. Every emotion, thought, or action embodied into literature has been human experience at some time. We can imagine nothing within the laws of nature, but what has had or may have an actual existence. A novel, therefore, but personifies the Truth. In giving a local interest to its actors, it introduces them to the reader through the medium of sympathies and passions, common to his own heart, of reason intelligible to his own mind, or of moral sentiments that find an echo in his own soul. Its success depends upon the skill and feeling with which the author works out his characters into a consistent whole—creating a simple and effective unity out of his plot, locality, and motive. Still every reader likes to feel that the persons whose fates warm his interest in the pages of a romance, actually lived and were as tangibly human as himself, and his degree of interest is apt to be in ratio to his belief that they were real personages. I am glad, therefore, to be able to assure my readers of the following facts.

In my youth I spent several years in different parts of the Pacific Ocean, but chiefly at the Sandwich or Hawaiian[6] Islands. While engaged in procuring materials for their history,—first published in 1843,—I was much struck with a tradition relating to their history by Europeans, two and a half centuries before Cook so accidentally stumbled upon them. Briefly it was this—

Eighteen generations of kings previous to Kamehameha I., during the reign of Kahoukapa, or Kiana, there arrived at Hawaii, a white priest, bringing with him an idol, which, by his persuasion, was enrolled in the calendar of the Hawaiian gods, and a temple erected for its service. The stranger priest acquired great influence, and left a reputation for goodness that was green in the memories of the people of Hawaii three centuries later. Another statement adds that a vessel was wrecked on the island, and the captain and his sister reached the shore, where they were kindly received and adopted into the families of the chiefs.

Without enlarging here upon the tradition, and the light my subsequent researches threw upon it, I will simply state that I became convinced that a Spanish priest, woman, and several men were rescued from a wreck, landed and lived in Hawaii, and acquired power and consideration from their superior knowledge, and for a while were even regarded as gods. Some of them intermarried with the aborigines, and their blood still exists (or did recently) among certain families, who pride themselves greatly upon their foreign origin.

Other traces of their existence are perceptible in the customs, ideas, and even the language of the natives,[7] which last has a number of words strikingly analogous to the Spanish of the same meaning. Captain Cook found among them a remnant of a sword-blade and another bit of iron. They were not strangers to this metal, and as no ores exist in their soil, they could have derived their knowledge solely from foreign intercourse.

Soon after the conquest of Mexico, Cortez sent three vessels upon an exploring expedition to California. After sailing as far as 29° north, one was sent back to report progress. The other two held on and were never heard from. Why may not one of these be the vessel that was wrecked on Hawaii? The winds would naturally drive her in that direction, and the date of the expedition agrees, so far as can be made out from Hawaiian chronology, with the time of the first arrival of white men on that island. Indeed, at that period of maritime discovery, white men could come from no other quarter. For my part, I believe that a port of Mexico was the starting point of the wrecked party; a conjecture which derives some plausibility from the fact, that, when the natives offered the whites bananas and other tropical fruits, they were familiar with them, which would be the case, if they came from Tehuantepec, from whence Cortez fitted out his vessel.

To absolutely identify the white strangers of Hawaii with the missing ships of Cortez, is not now possible. But the interest in them, left thus isolated from civilization amid savages, upon an island in the centre of the then unknown ocean, is peculiar. Especially have I[8] always been curious to trace the fate of the solitary white woman,—a waif of refinement cast thus on a barbarous shore,—and of the priest too,—to learn how far their joint influence tempered the heathenism into which they were thrown, or whether they were finally overcome by paganism.

Twelve years ago, while amid the scenery described in this volume, and the customs and traditions of the natives were fresh in my mind, I began to pen their history; but other objects prevented my going on, until the past winter, when leisure and the advice of friends, pleased with the subject, prompted its completion. The descriptions of the natural features of this remarkable island, of the religion, customs, government, and conditions of its aborigines, as well as the events in general, are as faithful transcripts, in words, of the actual, to my personal knowledge, as it is in my power to give.

In saying thus much for the facts, I am in duty bound to add a word for the ideas. Prefaces, some say, are never read. It may be so. But for myself, I like the good old custom, by which as author, or reader, I can talk or be talked directly to. It is the only way of familiar intercourse between two parties so essential to each other. I shall therefore speak on.

Every tale is based upon certain ideas, which are its life-blood. Of late, fiction has become the channel by which the topics most in the thought of the age, or which bear directly upon its welfare, reach most readily the popular mind. But few authors, however, can count[9] upon many readers, and I am not one of them. Still what a man has to say to the public, should be his earnest thought frankly told. No one has a monopoly of wisdom. The most gifted author cannot fill the measure of the understanding. The humblest may give utterance to ideas, that, however plain to most thinkers, may through him be the means of first reaching some minds, or at least suggesting thoughts that shall leave them wiser and happier. If what he say, has in it no substance of truth, it will speedily come to naught. But on the contrary, if it contain simply the seeds of truth, they will be sure to find a ripening soil somewhere in human hearts, and bud and blossom into peace and progress. With this motive I have spoken freely such views as have been prompted by my experience and reflections. They are not much to read, nor much to skip. Whichever the reader does, he carries with him my warmest wishes for his welfare, and the hope that if he find in the Story nothing to instruct, it may still be not without the power “to amuse.”

Casa Dauphiné,

Piazza Maria Antonia,

Florence, 1857.

“They that sail on the sea tell of the danger thereof; and when we hear it with our ears, we marvel thereat.”—Ecclesiasticus, xliii. 24.

To be alone on the great ocean, to feel besides the ship that bears you, nothing human floats within your world’s horizon, begets in a thoughtful mind a deep solemnity. The voyager is, as it were, at once brought before the material image of eternity. Sky and sea, each recedes without limit from his view; a circle above, a circle around, a circle underneath, no beginning, no ending, no repose for the sight, no boundary on which to fix the thought, but growing higher and higher, wider and wider, deeper and deeper, as the eye gazes and finds no resting point,—both sea and sky suggest, with overpowering force, that condition of soul which, knowing neither time nor space, forever[12] mounts Godward. In no mood does Nature speak louder to the heart than in her silence. When her thunders roll through the atmosphere and the hills tremble, the ocean surges and the wind wails; when she laughs through her thousand notes from bird or blossom, the heart either exults at the strife, or grows tender with sympathy in the universal joy. But place man alone on the ocean, shrouded in silence, with no living thing beyond his own tiny, wooden world for companionship, he begins to realize in the mighty expanse which engulfs his vision his own physical insignificancy. The very stars that look down upon him, with light twinkling and faint, from the rapidity with which they have sent their rays through distant firmaments to greet his vision and tell him there are countless worlds of greater beauty and higher perfection for his spirit to explore; even they deepen his feeling of littleness, till, finally, his soul recovers its dignity in the very magnitude of the scenery spread for its exploration. It knows that all this is but a portion of its heritage; that earth, air and water, the very planets that mock its curiosity, are ministering spirits, given with all their mysteries to be finally absorbed into its own all-penetrating nature.

Few, however, can so realize their own spirit-power, as to be calm in a calm. A motionless ship upon a silent ocean has a phantom look. The tall, tapering spars, the symmetrical tracery of ropes, the useless sails in white drooping folds, the black body in sharp relief in the white light, added[13] to the ghost-ship,—the twin of the one in the air,—in dimly-shadowed companionship, hull uppermost and her masts pointing downwards in the blue water, make up a spectral picture. As day after day passes, overhead a hot burning sun whose rays blind without rejoicing, no ripple upon the water, no life, because neither fish nor bird can bear the heat; the very garbage thrown overboard floating untouched, as if destruction rejected her own; the night mantling all in darkness, making silence still more oppressive,—for even the blocks refuse their wonted creaking;—all this consumes the body like rust slowly eating into iron. Nature faints and man sinks into her lassitude. He feels deserted of his own mother. She that bore him mocks him. Perchance a cold grey sky, pregnant with gloom, shuts down all around him, reflecting itself in the ocean which looks even greyer and colder. The atmosphere grows barren of light. No wind comes. Silent, motionless, and despairing, the vessel lies upon the waters; not slumbering, for every nerve within is quickened to unnatural keenness to catch a sign of change. It comes not. The seamen’s hearts, too worn to pray or curse, daily sink deeper within them, like masses of lead slowly finding their way through the fathomless depths of the ocean. A sail, a floating spar, a shark or devil fish, anything that were of man or beast, a shrub, the tiniest sea-snail or wildest bird, would be welcomed as Columbus hailed the floating signs that told to his mutinous crew a coming shore.

But none come. Weeks go by thus. Is man a god that his soul cannot fail within him! Must he not sympathize with the surrounding inanition! Welcome battle, welcome storm, welcome all that excites his energies, though it consume blood and muscle; be the mind racked and the body tortured; still man marches triumphantly on to his object. But take away opposition, reduce him to nothingness, convince him that action begets no result, that will is powerless, and he is no longer man. Not to act is conscious annihilation. But Nature never wholly deserts. She leaves hope to cheer humanity with promises that sooner or later must be fulfilled. There is, however, no condition so destitute of all that makes man Man as helpless solitude, when mind and body alike without action, stagnate and forget their origin.

Such was the condition of the crew of a vessel about the year 1530, lying motionless on the waters of the Pacific, not far from 25° north latitude and 140° west longitude. The bark was of that frail class, called caravel, scarcely fitted to navigate a small lake, much less to explore unknown seas. Yet, in those days European navigators did not hesitate to trust their lives and fortunes, on voyages of years’ duration, to craft which would now be condemned even for river navigation. The one of which we speak was of about seventy tons burden, with a high poop, which gave a comfortable cabin, a half deck and a forecastle, raised like the poop, sufficient to give partial shelter to the numerous crew. One mast with a large lateen sail rose from[15] the centre of the vessel, but her progress was aided as much by oars as by canvas. At the masthead was a castle-shaped box, in which the seamen could comfortably remain, either as lookouts, or for defence. This gave to the spar a clumsy, top-heavy look, wholly inconsistent with our modern ideas of nautical symmetry.

It was plain that the caravel had been long from port, and had suffered much from stress of weather. Her sides were rusty grey; barnacles clung so thickly below and above the water line, as to greatly interfere with her sailing qualities; the seams were open, and as the hot sun poured upon them, pitch oozed out. A tattered and threadbare sail hung loosely from the long yard which swayed from the masthead. The cordage appeared strained and worn to its last tension. Iron rust had eaten through and stained the wood in all parts of the hull. If paint had ever existed, the elements had long since eaten it up. Everything indicated long and hard usage. Yet amid all there were signs of seamanship and discipline; for bad and shattered as were rope, spar, and sail, everything was in its place and in the best order its condition permitted.

Within the cabin was a weather-beaten young man, well made, of a strong and active frame, features bronzed by long exposure to varied climates, and fine soft hair, somewhat light in color, which even now would have curled gracefully, had it been properly cared for. He lay ill and panting on the transom, with his face close to the open[16] port, gasping for air; not that he was seriously reduced, for it was readily seen that fatigue, anxiety and scanty fare had more to do with his weak condition than actual disease. Near him was a rude chart of the coasts of Mexico and adjacent sea, which he had long and carefully, and, to all appearance, fruitlessly studied. It was covered with a labyrinth of pencil marks, indicating a confused idea both of navigation and his present position. He had been recently poring over it, and at last had thrown it aside as utterly worthless, or at all events as affording him no clue by which to extricate himself from his present situation in a sea wholly unknown to the navigators of his day.

Near him sat a priest, whose thoughtful, benevolent face was far from expressing despair even under their present circumstances. He talked to the young man of the necessity of trusting themselves to the guidance of Providence, and sought to cheer him by his own hopeful serenity and untiring action.

Around the deck and under such shelter from the heat as they could contrive, the crew reclined in mournful groups; some with faces hardened into despair, and others careless or indifferent. A few only manifested a spirit of pious resignation. The strongest seldom spoke. Their looks were as sullen as their tempers were fierce, and if they opened their mouths, it was to mutter or curse, daring Nature to do her worst. Nothing but their physical debility prevented frequent violent explosions of the pent-up irritability arising from their[17] helpless state. Disease and starvation were rapidly adding fresh horrors to their situation. One seaman lay on the hard deck with a broken thigh, in which mortification had already begun, groaning and piteously asking for water. In his thirst he would have drank more in one hour than was allowanced to the entire crew for a day’s consumption. Several others, whose fevered tongues rattled from dryness, were also tossing and moaning on the rough planks, too weak or hopeless to join in the fruitless appeal of their dying comrade. Such water as they had was clotted with slime, and impregnated with foul odors. Their meat was all gone, and the little bread left, musty and worm-eaten.

All wore the look of having long struggled with adverse fortune. They were men whose element was made up of hardship and adventure; men, who, forgetting in one hour’s better fortune all that had brought them to their present condition, would not hesitate to embark again on a similar errand. Here they were, bowed in spirit, haggard in features, their hardy limbs lying torpidly about, indifferent to death itself, but worn to worse than death by drifting for weeks about under a pitiless sun on an unknown sea, which the oldest of them had never heard of, and which seemed to them as if they had arrived within the confines of stagnant matter, where they were doomed to rot in body and decay in mind, coffined in their vessel, whose slow destruction kept even pace with their own.

Five of their number had already died and been cast overboard. Gladly would they have seen[18] sharks gorge themselves on their late shipmates, as that would have shown them that the water still contained life. But no carrion fishes came near them. With faces upturned and glassy eyes fixed upon the caravel, those corpses floated about them so long that the crew were at last afraid to look over the bulwarks for fear of seeing what they desired so much to forget.

But humanity had not altogether abandoned them. The frailest in body among that vessel’s company proved the strongest in faith and action. A woman was of their number. Consuming even less of their provisions than the others, she reserved herself, and in great measure her allowance of food, for those whose necessity she considered as greater than her own. At all hours was she to be seen moving quietly about, speaking hope and courage to one, giving to eat or drink to another, or fanning the hot brow of a half delirious sufferer, while she talked to him of a home into which no suffering could enter, if the heart once were right. Especially was she devoted to the young man in the cabin. He evidently relied even more upon her than upon the priest, and imbibed fresh strength and hope from her voice and example. The priest was equally unwearied with his bodily aid and spiritual counsel to the crew. Thus it was that amid the most trying of the experiences of ocean-life, despair did not altogether quench hope.

Yet what situation could be more cheerless! One altogether similar in the history of navigation had never occurred before, and by the hurried course[19] of discovery and civilization, would not again occur. They were literally alone, drifting on an unknown, motionless sea. No winds stirred its surface; no birds flew by; no fishes came up from beneath their keel; there was no change except from the burning day to the feverish night, which brought with it no cooling dew, nor any sign to excite a sailor’s hope. Although they could not know the fact, not a vessel beside theirs for thousands of miles east or west, north or south, floated on that ocean. Driven thither against their wills, they were the first to explore its solitude. It was true that continents and archipelagoes thickly peopled were around them, but for all they knew, they were being carried by an irresistible fate to the boundary of nature, whence they would drop into a fathomless void. They were therefore literally alone.

The caravel in question was more than ordinarily frail, having been hastily equipped with two others from the port of Tehuantepec in Mexico, at the order of Cortez for the exploration of the continent about and above the gulf of California. It is true, an experienced seaman named Grijalva had been put in command, and he had been so far successful as to have reached the twenty-ninth degree of north latitude. Thence one vessel had been sent back with an account of his progress. The other two continued their explorations northward, with the hope of arriving at that kingdom so rich in precious metals, of which they had heard so many rumors from the recently conquered Mexicans. Creeping coastwise slowly upward, many fine bays with shores rich in verdure met their view, but of gold they found no traces, and of inhabitants, with the exception of an occasional glimpse of a naked savage, who ran terrified away, they were equally[21] unsuccessful. Yet they were navigating waters, the tributary streams of which were literally bedded in gold. But neither the time nor people to which this treasure was to be disclosed had arrived. Consequently, Grijalva, with his eyes blinded to what was constantly within his reach, saw nothing but a vast wilderness, which promised neither wealth nor honor as the reward of further exploration. Reluctantly, therefore, he turned his course southward. That night a severe gale came on, and both caravels were driven far from their course towards the southwest. It was in vain with such unseaworthy vessels that Grijalva sought to regain the coast. The wind blew him still farther into unknown seas, which daily became more tempestuous, until his storm-shattered vessel sank in sight of her scarcely better conditioned consort, engulfing all on board.

This sight for the moment chilled the hearts of the surviving crew, and paralyzed their exertions. But Spanish seamen and the soldiers of Cortez were too accustomed to death in every form, to long despair. They redoubled their efforts, and by bailing and cautious steering, keeping the vessel directly before the wind, weathered the gale, which the next day was succeeded by the fatal calm, already described.

There were on board some twenty persons, veterans in the hardships and conflicts of the new world. Their commander was the young man that lay exhausted in the cabin. He spoke to the woman who now sat with his head on her lap,[22] while she gave him such meagre refreshment as their famished bark afforded. His name was Juan Alvirez. Hers was Beatriz. They were brother and sister. He had been a volunteer with Narvaez, and after his defeat enlisted under Cortez, and was present at the siege of Mexico, and all the subsequent expeditions of his commander, to whom he was greatly attached. This attachment was founded in a congeniality of temperament, which led him to emulate the heroic daring and unflinching perseverance of Cortez, while his more powerful intellect was equally an object of his profound admiration. With the same thirst for adventure, the same chivalric courage, the same devotion to the Catholic worship, the same contempt for the rights, feelings or sufferings of others so that his own desire was gained, devout and loyal, with deep affections, easily moved to anger or kindness, childlike in his impulses, yet strong in action, Alvirez in most points, except judgment, might be considered a Cortez on a small scale. Indeed, his intimacy with him, begun when Alvirez was not twenty years of age, had, by strengthening the natural traits of character so similar to his own, quite merged him into his commander. His individuality was shown chiefly in executing what Cortez ordered, and in blind though gallant acts of devotion, upon the spur of emergency, in which prudence or generalship were not often considered.

Alvirez was frank and social. These qualities joined to his tried bravery made him the favorite of all. Even the Mexicans who had so often suffered[23] from his arm, learned to distinguish and admire in him that generous fearlessness to all danger, which pitiless to them, was self-devoted to his own cause, and stooping to no artifice in action, went direct to its mark, like the swoop of a hawk upon its quarry. With them he was known as Tonatiuh, ‘the child of the sun,’ from his burning glance and stroke as quick as light. His thirst for adventure keeping him in continual action, he gladly volunteered to command the soldiery in the expeditions which Cortez sent to explore and subdue the unknown regions to the north of Mexico.

Not yet in the prime of life, we find this Spanish cavalier, faint from exertions which had wearied out all on board, lying half helpless, grieving over the fate of the brave seamen who had so long and skilfully kept the little squadron afloat.

His sister Beatriz shared many of these traits with her brother. She was as brave, self-devoted, ardent, and impulsive as he, but true womanhood and a benevolence of heart which instinctively led her to seek the happiness of those with whom she was, made her in conduct an altogether different being. Deeply imbued with the Roman Catholic faith, while she sedulously conformed to the demands of its ritual, its principles tempered by her own native goodness and purity, reflected through her peace and good will towards all men. Juan was all energy and action. His will flowed from desire like a torrent, rending asunder its natural barriers, and spreading mingled ruin and fertility in its course. Her will was deep, calm, and sure,[24] without noise, with no sudden movement, but like the quiet uprising of an ocean-tide, it steadily rose, floating all things safely higher and still higher on its bosom, until they attained its own level. All about her felt its movement, wondered at the effect, and welcomed the cause.

Her influence over rude men was not the result of charms that most attract the common eye. The oval of her head was faultless. Her hair was of ethereal softness, and seemed to take its hue and character from her mind rather than from nature’s pigments. Considering her race, her complexion was rare, being blonde. Warmth, firmness, decision, and much heart-suffering, were denoted by her mouth. Her eyes spoke at will the language of her soul, or kept its emotions as a sealed book. Yet they were not beautiful in the strictly physical sense, being in repose somewhat lifeless in color, but when they talked, an illumination as if from another sphere overspread her countenance, and surrounded her entire person with an atmosphere radiant with spirit emotion. So gentle, yet so penetrating was her speech, that it seemed as though she breathed her language. To the listener it was as if some delicious strain of music had passed through him, harmonizing his whole nature. This, no doubt, was owing rather to her purity and earnestness, as they found language and a responsive echo and all that was true and good in others, than to any wonderful endowment of voice. Her vital organization being acute and generous, she was extremely susceptible to all life emotions, yet so[25] well-balanced was her character, which was the result of a varied experience, garnered into wisdom, that came more from intuition than out of the cold processes of reason, that rarely was she otherwise than the same quiet high-toned woman, as persuasive to good by her presence, as faithful to it by her example. None, therefore, asked her age, debated her beauty, or questioned her motives. All, even the mercenary soldier, the profane seamen, and the untutored Indian, felt themselves better, happier and safer, for having her among them. Her sad, sympathizing face, her winning speech, generous action, and noiseless, graceful carriage, were to them more of the Madonna than of the earth-woman. Yet she was strictly human, differing from others of her sex only in being a larger type of God’s handiwork, with fuller capacities both to receive and give, whether of suffering or joy. The key to her character was her invariably following her own noble instincts, sanctioned and aided as they were by the principles of her faith. In this respect, she was fortunate in possessing for her confessor the priest who was with them. He was a Dominican monk, Olmedo by name, and although attached by education to his theology, was of enlarged and humane mind, and felt that love rather than force was the only sure principle of conversion of the heathen to Christianity.

Olmedo had come from Spain with the father of Alvirez, who held a post of trust in Cuba. Thence he followed Cortez to Mexico, and on repeated occasions had done much to soften his[26] fanaticism, and inspire him with a more humane policy towards the unhappy Indians. When Alvirez set out on the present expedition, his sister and Olmedo determined to accompany him; the former from her love for Juan, and the latter from attachment to both, and the hope that he might find a field for missionary labor, in which the principles that animated him and Beatriz might have free scope, unneutralized by the brutality and excesses of the miscalled soldiers of the Cross.

The other members of the caravel’s company need just now no special mention, except that although bred in the Cortez school of blood and rapine, they were, almost unconsciously to themselves, influenced much not only by the high toned courage and unflinching perseverance of their commander, but still more by the purer examples and earnest faith of Beatriz and Olmedo; each of whom, as opportunity offered, sought to deepen this impression, and to persuade them that there was truer treasure on earth than even the gold for which they lavished their blood, and better enjoyment to be found than in the brutal indulgence of base passions. There was, in consequence, in most of them a devotion to their leader and confessor, loftier and more sincere than the force of discipline, or the ordinary inspiration of their religion, because founded on an appeal to their hearts. For Beatriz the rudest one among them would willingly have shed all his blood to save a drop of hers.

“May the Holy Mother receive their souls,” somewhat abruptly exclaimed Juan, who had been[27] musing upon the fate of Grijalva. His sister did not reply, except by a deep sigh, feeling that silence best expressed her sympathy with her brother’s ejaculation.

Juan and those of the crew who now remained alive, exhausted by their sufferings and labors, soon sunk into a sound sleep. Olmedo and Beatriz were alone left awake, and avoiding by a common instinct the past, they talked only of their present situation and probable future. There was nothing in their external conditions to authorize hope for maiden or priest; yet a reliance on divine care so completely filled their hearts, that although no light penetrated their ocean-horizon, each felt and spoke words of encouragement to the other.

While they talked, light breezes began in variable puffs to stir the sails. As the wind increased, it grew contrary to the course for Mexico, yet it was balmy, and as the sea under its influence began to rise and fall in gentle swells, the air became cooler, and the sky was gradually interspersed with fleecy clouds which occasionally shed a little rain.

Awakening Juan and the crew, Olmedo pointed to the clouds, which, driving before them, seemed to beckon to some unknown haven beyond. “Our deliverance has come,” exclaimed he; “let us lose no time in welcoming the breeze.”

“We cannot reach Mexico with this wind,” said Juan glancing aloft; then, as his spirits revived with the brightening prospect, he gaily added, “Let us follow whither it blows; new fields of adventure may repay us for those we have lost.”

“My son,” solemnly replied Olmedo, “we are a feeble band, but trusting in Him who ordereth all things, we may accept with gratitude the auspicious breeze; not to carry us to new scenes of slaughter, but in the hope that He who has preserved us alike from the storm and calm, reserves us for a more noble mission.”

“What say you, Beatriz, is father Olmedo right?” asked Juan, more to hear her voice than as desiring her opinion, which he knew would conform to her confessor’s.

“Dear brother, our father is right. Orphans that we are, let us abandon ourselves to the guidance of the Holy Virgin and the saints. They will lead us to the work they have for us to do.”

To the followers of Alvirez, any course which promised a new excitement or conquest was welcome. They therefore bestirred themselves with such alacrity as their famished condition permitted. In a short time the caravel was going before the wind with all the speed she was capable of, while the crew, excepting the necessary watch, again betook themselves to the repose they so greatly needed, and which, sustained as it now was by hope, did much to revive their strength.

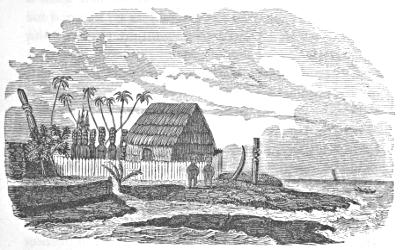

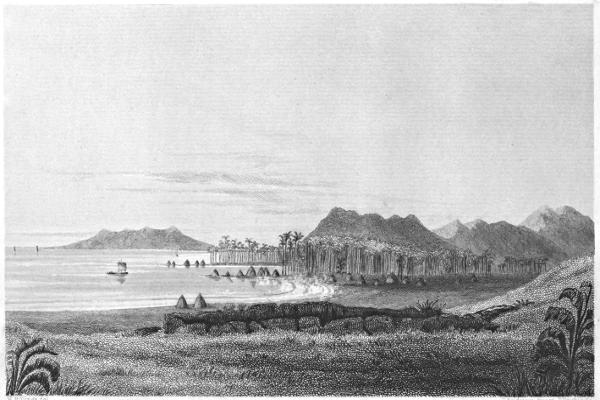

In the nineteenth degree of north latitude, and one hundred and fifty-five degrees west, lies a large and important island, one of a group stretching for several hundred miles in a north-westerly direction. At the date of this tale, it was wholly unknown, except to its aborigines. Situated in the centre of the vast North Pacific, not another inhabitable land within thousands of miles, it was quietly biding its destiny, when in the circumnavigating advance of civilization westward to its original seat in the Orient, it should become a new centre of commerce and Christianity; and, as it were, an Inn of nature’s own building on the great highway of nations.

Up to this time, however, not a sail had ever been seen from its shores. Nothing had ever reached them within the memories of its population, to disprove to them that their horizon was not the limits of the world, and that they were not its sole possessors. It is true, that in the songs of their[30] bards, there were faint traces of a more extended knowledge, but so faint as to have lost all meaning to the masses, who in themselves saw the entire human race.

Hawaii, for such was the aboriginal name of the largest and easternmost island, was a fitting ocean-beacon to guide the mariner to hospitable shores. Rising as it does fourteen thousand feet above the level of the sea, snow-capped in places, in others shooting up thick masses of fire and smoke from active volcanoes, it could be seen for a great distance on the water, except, as was often the case, it was shrouded in dense clouds. Generally, either the gigantic dome of Mauna Loa, which embosomed an active crater of twenty-seven miles in circumference on its summit, which was more than two and a half miles high, or the still loftier, craggy and frost-clad peaks of Mauna Kea, met the sight long before its picturesque coast-line came into view. As usually seen at a long distance, these two mountain summits, so nigh each other and yet so unlike in outline, seemingly repose on a bed of clouds, like celestial islands floating in ether. This illusion is the more complete from their great elevation, and coming as they do with their lower drapery of vapor, so suddenly upon the sight of the voyager, after weeks, and, as it often happens, months of ocean solitude.

Nowhere does nature display a more active laboratory or on a grander scale. At her bidding, fire and water here meet, and, amid throes, explosions, upheavings and submergings, the outpourings of[31] liquid rock, the roars of a burning ocean, hissing, recoiling and steaming at the base of fiery mountains, which amid quakings and thunders shoot up high into air, not only flame and smoke, but give birth to other mountains, which run in fluid masses to the shore forming new coast-lines, she gradually creates to herself fresh domains out of the fathomless sea, destined by a slower and more peaceful process to be finally fitted for the abode of man. For ages before the human race appeared, this fierce labor had been going on. Slowly decreasing in violence as the solid fabric arose from the sea, the vegetable and animal kingdom at last successively claimed their right to colonize the land thus prepared for them. Nature, however, had not yet finished the substructure; for although she had extinguished a portion of her fires and allowed the forests to grow in some spots in undisturbed luxuriance, yet there were others still active and on a scale to be seen nowhere else on the globe. At intervals, rarer as they became older, they belched forth ruin, to add in time greater stability and more fertility to the new-formed earth.

Even to this day, Hawaii continues in a transition state. The vast agencies to which the island owes its origin, not unfrequently shake it to its centre, giving a new impetus to its geological growth. Sometimes it rocks, so it seems, on its centre, and alternately rising and falling, the ocean invades the land, sweeping from the coast by its fast rushing tide,—piled up by its velocity into such a wall of water as in its recoil overwhelmed Pharaoh’s host[32] in the Red Sea,—whole villages, and carrying off numbers of their struggling population to perish in its vortex. So rapid is its reflux and over so vast a space, that it often leaves bare its own bed, with the finny tribes stranded amid its coral forests, or flapping helplessly on its sandy bottom. When this phenomenon occurs it is generally in quick successive waves, without previous warning, and so rapidly, that were it not for the amphibious habits of the islanders, the destruction of life would be great.

The sister islands further to the west have long since ceased to fear earthquake or volcanic eruption. Their surfaces are covered with extinct craters, lined in general with verdure and melodious with the notes of birds. Around each of the group, by the labors of the tiniest of her creatures, as if to show how the feeblest agencies at her bidding can control the strongest, Nature is slowly but surely constructing a coral frame, a fit setting to her sunny picture. The busy little zoöphyte, by its minute industry sets that bound to the ocean, which Canute in all his power was unable to do. Over its barriers and through its vegetable-like forms, trees and shrubs, blossoms and flowers, rich in every hue which gives beauty to the land, the rushing wave can pass only by giving toll to these water bees. They have not to seek their food, but they make the everlasting waters bring it to their door, and pour over them, in their struggle to reach the shore, a glad symphony of power and praise.

On the northeast of Hawaii lies a deep bay,[33] fringed with coral reefs, but in many places presenting high cliffs, precipitous masses of volcanic rock, rent by deep chasms, or forming valleys through which pour streams of fresh water along banks of surpassing fertility. Everywhere the soil is good and the vegetation profuse. Numerous cascades tumble from the hills in all directions, giving life and music to the scene. Some are mere threads of water lost in spray amid rainbow arches, before reaching the rocky basins underneath. Others shoot from precipices, waving, foaming torrents, which thunder over stream-worn rocks, far away beneath in sunless and almost inaccessible dells. Emerging from these into placid rivers, they flow quietly on till meeting the incoming surges of the ocean, which, as they struggle over the coral bars at their mouths, whiten their surfaces with foam and break into eddies and uncertain currents, creating trying navigation for the frail canoes of the islanders.

The vegetation was unequal in luxuriance. In some spots it pushed its verdure quite into the brine, which not unfrequently watered the roots of trees that overhung it. In others, broad belts of sand came between the grasses and the water. These glistened in the sun’s rays in contrast with the back ground of dense green, like burnished metal. Earth, the provident mother, had not, however, so overdone her good works, as in some of the more southern groups to provide a meal without other labor than plucking. There were fine groves of the different species of food-bearing palms,—orchards[34] of bread-fruit and other kinds of trees, from which man could derive both sustenance and material to clothe and house him; but for these purposes and the culture of the taro plant, which was his main resource, no little labor and skill were necessary.

Metals were unknown. The animal and feathered creature were scanty in species and numbers, and much of the island surface was still a wilderness of basaltic rock or fields of lava and cinders. But such was the salubrity of the climate and the activity of nature, that its resources for the comfort, and to a considerable degree of the civilization of man, were making rapid development; not sufficient as yet to release him from the active exercise of his faculties, and thus induce a sensual repose, but just enough to reward him for exertion, while indolence was sure to beget actual want.

The little caravel with her famished and sickly crew that we left in the midst of the North Pacific, rolling before a fresh breeze from the northeast, which proved to be the regular trade-wind, had continued her course for several days in the same direction. During this time, several others of the ship’s company had died and been cast overboard. Frequent showers, and the occasional catching of flying-fish, and now and then a dolphin or porpoise, did somewhat to restore the physical energies of the survivors, while the balmy condition of the air, the exhilaration of rapid motion, and the prospect of novel adventure, had much weight in raising the spirits of all.

Still there were no indications of land. The sun had set for the tenth time behind the same purple canopy of clouds; the same birds screamed and flew overhead; the waves rose and toppled after them with gushing foam, just so high and no higher; the sails bellied out with monotonous fulness; not a rope was stirred nor oar moved; on, on, rolled the caravel, now dipping this bulwark, now that, surging aside the water and trailing it in her wake with the noise of a mill-course; no variety, except that the north-star sank lower each night, until the very evenness of their way, hour answering to hour and day to day, began to beget in them a feeling of doubt as to the actual existence of land in the direction they were heading. This, combined with the weariness which inevitably steals over the senses when long at sea without change, led to greater carelessness in the night-watches. They fancied themselves borne onward by a fate which their own precautions could neither alter nor avert. Hence it was, that having worn out conjecture and argument as to their positive and probable destiny, they had on the tenth evening more than ordinarily abandoned themselves to chance. The day had been thicker than usual, and there was no light at night except the uncertain twinkling of stars through driving masses of clouds.

All except the helmsman slept. He dozed. Habit kept him sufficiently awake to keep the caravel to her course, but nothing more. Suddenly a dull, weighty sound was heard, like the roll of[36] heavy waters, dying slowly away in the distance. Another; then another; quicker and quicker, each louder and nearer. The caravel was lifted high on one sea and fell heavily into the trough of another, rolling so uneasily as to start up all on board. At this moment the pilot, catching the gleam of a long line of breakers, hoarsely shouted “all hands, quick, or by the saints we are lost,” at the same moment putting the helm hard down to bring her into the wind. He was too late. The craft fell broadside into the rollers and became unmanageable. The mast snapped off close to the deck, and was pitched into the water to the leeward. At the same instant a grinding, crushing sound was heard underneath, as the caravel was lifted and thrown heavily upon the reef, breaking in the floor timbers and flooding her hold with water. It was too dark to distinguish anything but the white crest of the breakers all around, while their noise prevented any orders being distinctly heard. Indeed so sudden and complete was the disaster, that there was nothing to be done by the crew but to cling to the wreck and passively await their fate. Death came soon to a number, who were washed overboard and taken by the undertow seaward, where sharks fed upon them. Waves washed over the vessel in quick succession, gradually breaking her up. The after cabin held together longest, affording some shelter to its occupants. In a little while, however, even this was gone. All left on board were floated off, they knew not whither, clinging to whatever they could grasp, and rolled over in the surf until[37] most of them became insensible. Beatriz, however, retained her presence of mind, and aided by the almost superhuman efforts of Tolta, a Mexican captive, was finally cast upon a soft beach, without other injury than a few skin bruises and the swallowing of a little water, of which she was soon relieved. It was too dark to learn the fate of the others. Dragging themselves beyond the wash of the breakers, in anxious suspense they awaited daybreak to disclose more fully their situation.

Within the tropics the sun lights up the earth or leaves it, with scarcely any of the mysterious greeting or farewell, with which in more northern climates he loiters on his way, dyeing the landscape with subtle gradations of colors, from the fullest display of his mingled glories in a yellow and purple blaze, to the faintest hues of every shade, delicate and aerial, like the gossamer robes of spirit land. His coming is punctual and his welcome hearty. Objects take their hue and shape from out of the night almost instantaneously, changing from black to golden brightness, as by the touch of magic. There is loss of beauty to the eye in this, though the earth may gain in fertility from not having to wait so long for the fruitful warmth.

It was well nigh morning when the caravel broke up in the reef. The air was warm, and although the surf roared as loudly as ever, the wind had gone down. Soon the sun began to appear above[39] the horizon. Beatriz, availing herself of its earliest light, began to search for her brother and his company. Tolta was active also. Bits of the wreck strewed the beach, with here and there articles that might still be of service, but she paid no attention to them. Hurriedly looking about her, hoping yet fearful, she espied a body half-buried in the sand. In an instant she was beside it, but it was one of the crew, stiff and cold. There was no time to spare for a corpse, so she continued her search for the living. An object half hidden amid low shrubbery caught her eye. Hastening thither, she saw the well known white robe of Olmedo. With a cry of joy she rushed to it, and then breathlessly knelt at his side, placing her hand upon Olmedo’s heart and her mouth close to his, to detect any signs of life. He was warm and breathing. His eyes slowly opened, and recognizing Beatriz, for a moment he seemed to have forgotten the wreck, and to imagine himself still at sea. As he stretched out his hand with a smile, to give her his wonted welcome, she seized it passionately, kissed it and burst into tears.

The good father, surprised at this feeling in one usually so calm, yet carried away by it without knowing why, pressed her hand warmly in return, while a tear found its way also to his eye. Instantly recovering her usual manner, Beatriz asked if he could give her tidings of Juan.

The question recalled to Olmedo the disaster of the night. He had himself been thrown ashore, on top of a plank to which he had clung at the breaking[40] up of the caravel, and had scrambled up the beach, until he reached the bushes, where he had been found half gone in faintness and sleep.

At the name of Juan he started to his feet and said, “Let us lose no time in looking for him. The wreck was so sudden that human efforts could not have availed to save any one. God may have brought him safely to shore as he has us.”

They had not gone far before a well known voice was heard calling loudly upon Beatriz. In an instant, she was clasped in the embrace of her brother. He had rushed from a neighboring grove, as he caught sight of his sister, and now the two in their sudden joy clung to each other with mingled sobs and laughter; for being twins their active affections had been formed together in one maternal mould.

Juan led the party to the spot from which he had emerged, where they found three of the seamen. It seems that Juan had reached the land, somewhat bruised, in company with them, and the four had spent their time in searching for Beatriz and others of the crew, but owing to the darkness of the night and the loudness of the surf, they were neither seen nor heard. Farther search assured them that they were the sole survivors of the wreck. Accordingly having secured the few objects of utility that had been thrown ashore from it, they began to explore their new home in reference to their future wants.

The land was much broken and thickly covered with vegetation, some of which was familiar to them from being common to the “tierra caliente” of Mexico. As they wandered inland they came[41] to cultivated patches of yam and the sweet potato. Many of the fields were enclosed in well constructed stone walls. They were therefore in an inhabited land, and, as they thought, must soon meet the tillers of the soil. Bananas and other fruit hung within their reach. Numerous paths intersected grounds, which were divided into square or oblong lots, surrounded by dykes, planted with the broad leafed, nutritious taro, and irrigated by so admirable a network of water-courses as to extort from all exclamations of surprise. Following up the most trodden of these paths, they came to a retired valley embosomed amid forest-clad hills, with a quiet stream flowing through its centre, and cultivated as far up as the eye could see, in the same manner as the fields through which they had passed. Soon houses came into view. They were in clusters, low, of thatch, raised on embankments, with stone pavements around them, or fenced in by rude palisades.

Expecting each minute to meet the owners, they proceeded cautiously towards them. They were disappointed, however, for not a human being appeared; not even a dog or domestic animal of any kind; the air was still and the sun hot; there was no hum of insects or song of birds; the sole life that met their view was now and then a stray lizard, that glided so quickly and silently away as but to make the surrounding stillness still more sensible.

They began to distrust their senses. Were they in an enchanted land? Was their shipwreck real,[42] or were they dreaming? Their very voices seemed to die out in the universal silence. They gathered fruit and eat, and this reassured them of the reality of their appetites at least, but their own shadows as they lengthened before them seemed unreal, while those of tree and rock cast spectral forms about their path.

Terrible and oppressive grew upon them the ambiguity of their position. Were they watched and being led by enchantment into the power of savage foes, or were they tantalized by illusions, like the dreams of starving men who rave of dainties ever within their reach? What meant this life without life, harvest without reapers, houses without owners, this atmosphere without insect-hum or bird-song? The very waters enclosed in rocky basins, or overshadowed by motionless foliage, were unrippled by current or wave, and repeating the landscape in their still depths, made it even more unreal. The gracefully shaped canoes which floated upon them without moving, looked as if painted upon the surface of the stream.

Juan’s impatient spirit chafed for want of action. “By the Holy Mass, father Olmedo,” he cried, “this silence beats that which made us hold our breaths on the night when we marched out of Mexico, thinking we were stealing away unseen from those red devils, when tens of thousands of their impish eyes were glaring upon us, awaiting the signal to drag us to their damnable temples. Well must you remember it, and how sad a night they made of it to us, after the silence was once broken by[43] their infernal yells, as they dragged away so many of our companions to have their hearts torn from their living bodies, as offerings to their hideous war-god. Jesu Maria! I like not this awful stillness. Give me rather a hundred foes and my own trusty horse, that I might dash among them with our old battle-cry;”—and in the excitement of the moment, he sprang forward, waved his sword and shouted at the top of his voice, “At them, cavaliers; Santiago for Spain.”

“Ah! I have started you at last,” he exultingly exclaimed. “Hark! By the Holy Virgin, they reply in our blessed language. A dozen wax candles for our Lady’s shrine for this, as soon as I can get them,—we are among friends, Beatriz.”

“You mistake, Juan,” replied Beatriz. “The words you hear are only your own sent back from the hills.”

Juan, distrusting her more acute senses, again shouted, and convinced himself that it was only the rocks that mockingly echoed the shout. It was the first time since their creation, that they had given back a sound foreign to their own shores, and it seemed to linger long among them as if they relished its notes. Then the silence brooded over the scene more ominously than before, as no foes appeared, and no human voice sent back the defiance. Tolta’s eyes, however, glared furiously on Juan at his ill-timed allusion to “La Noche Triste,” but it was only for a moment. Beatriz had observed the look, and in a low whisper said to Juan, “Nay, brother, forbear, that night was a sad one to[44] many besides ourselves. Why provoke Tolta to revengeful thoughts? He has done us both faithful service. For my sake respect his feelings.”

Chafed as he was at the mysterious silence, which only angered him, while it awed, not through fear, but from the depths of its repose, the hearts of Olmedo and Beatriz, who found something in it kindred to their own position, Juan’s hasty impulse would have been to have vented his irritation upon the Mexican, but a second look from his sister restored his better nature, and he frankly held out his hand to him, exclaiming, “Pardon my hastiness, Tolta, I meant not to vex you.”

The Mexican’s features resumed their usual apathy, and no one would have supposed from them, that an emotion had ever touched his heart. Yet among them all, no eye or ear was keener than his, no nature more sensitive, none so quick in its perceptions when touched in its own interests or passions, and none more patient, outwardly forbearing, and inwardly revengeful, for he was faithful to self-immolation in his friendship, and equally so in his enmity.

In him love to the individual and hate to the Spanish race were so interwoven, that it would have been impossible for himself to foresee how he should act on any occasion which might afford scope for either passion. He was an Aztec by birth, of the race of the priesthood, young, accustomed to arms, and learned in the lore of his race; at heart a worshipper of their idols, though a forced baptism, and the necessities of a captive, made him nominally a Christian. Manuel was the name bestowed[45] in baptism, but I prefer to retain that of his birth. In him lay dormant all those qualities which marked the downfall of his nation. He was both subtle and open, gentle and fierce; in his domestic relations inclined to love and peace, refined and courteous; in his faith believing in one God of “perfection and purity,” yet delighting in smearing the altars of terrible deities with human gore; a tiger in rage, and a lamb in sentiment; in short, combining in his own breast the instincts of brute and man, with no harmonizing principle to keep him in permanent peaceful relations with himself or his kind. He believed in peace and purity, and delighted in war and cruelty, displaying to his enemies either open and irreconcilable hatred, or concealing revenge under the mask of courtesy and kindness, nay, almost servility, at the same time recognizing no principles of humanity or religion which interfered with his desires. As a conqueror, he was imperious; as a captive, abject. But the native pride and fierceness of his race, so long dominant among servile tribes, ill adapted him to his present anomalous state, in which, while feeling himself partly treated as a friend, he could not forget the events so recent in the history of his race which had made him in reality a slave. Although he brooded much over his own altered destinies and his country’s fall, yet, while with Beatriz, the gentle principle in his nature became active, and he felt soothed and grateful.

Concord being restored, the little party footed their way towards a cluster of houses of more pretension[46] than the others, built upon a slight eminence, terraced on all sides with stone work, and having a flight of steps to the summit. This was walled in, and gave sufficient area to enclose quite a hamlet. Indeed it might be considered a fortification of no slight strength, where fire-arms were unknown.

They proceeded cautiously up the steps, stimulated by curiosity, and thinking it better to brave openly and promptly any danger that might threaten, as from experience they knew that no demeanor imposes more powerfully upon barbarians than courage. To this course Tolta advised them. He was the least affected by the singularity of their position, and seemed in many things to recognize a similarity in the degree of civilization and manner of cultivation, as well as in the articles themselves, to the habits and productions of tribes on the southern frontiers of his own country, though the entire absence of precious metals, and any altars or edifices which indicated the worship of sanguinary deities, puzzled him not a little.

Immediately within the wall, and bordering the main avenue, leading to a large and commodious house, were many rudely carved wooden images, with round staring eyes and grinning mouths. Before them were the remains of fruit, and about them were hung wreaths of flowers, indicating that they were held in reverence. Passing between them, Juan felt disposed to try the temper of his sword upon their awkwardly shaped legs and arms for practice, and to express his abhorrence of what he[47] termed blasphemy, quite forgetful that in his own land images of the Virgin and saints, some scarcely better executed, were common to every street and by every roadside, and that before them were lamps constantly burning and offerings of flowers placed.

Olmedo’s better judgment checked him. “This indeed may be, my son, as you say, a device of Satan to turn their hearts from the true worship; but let us learn more before we act. These very offerings and idols prove the necessity of worship to the darkened minds of their makers, and from these false symbols we may by persuasion turn them to the holy ones of our religion. Remember the Master’s charge to Peter, when he would have taken the sword. We have had too much of that, and too many of your brothers in arms have already perished by the sword. We have been led hither for some wise purpose. Be peaceful and patient. God will disclose his design in due season. In the meantime, let us respect all that we see, and if the people of this silent valley show themselves, meet them with the cross aloft and open hands. We are too few to contend against a multitude, though not to persuade them by courtesy and our very helplessness to peace and kindness. If none appear, let us use these good gifts, as provided by Him who has led us thither.”

Juan replied: “By my troth, father, I would clip off the heads of a few of these ugly monsters, if for no other motive than to call up a host of the evil spirits that possess them, that I might do them battle. You speak truth, however, and I will be[48] patient. Hurry on, my men, let us explore this sanctuary, and see if we can start out any one to give us the hospitality we so sorely need.”

Beatriz, who feared his hasty mood, stopped him as he was about to enter the large house. “No, Juan, let me go in first. The inmates, if any there be, may slumber; the presence of a maiden,” said she, “will create neither alarm nor fear. I will enter first.”

So saying, she drew aside the heavy cloth which hung at the door and went in. Olmedo not heeding her request to Juan, entered immediately after, but not soon enough to anticipate Tolta, who glided in before him as noiselessly as a shadow. Juan and the others without further question followed after.

They found themselves in a spacious room formed by white posts driven into the ground, with rafters springing from them, making a lofty roof, covered throughout with thatch, fastened on in the neatest manner with neatly braided cord. The floor was spread with white mats. Every part was scrupulously clean. There were raised divans of fine mats variously colored, and as pliable as the coarser cloths of Europe. These invited repose, though the pillows being of wood covered with matting, indicated no effeminacy in the slumbers of their owners. Several of these divans were curtained by gaily painted cloths, differing in texture from anything they had seen before. It was something between paper and the cotton fabrics of Mexico. Garments of the same material, but of softer and finer quality[49] hung about the walls. There were also wooden bowls of beautiful grain, highly polished and indicating no slight degree of mechanical skill; also vessels for water, formed from the gourd plant and prettily ornamented; fans, graceful plumes of crimson and golden feathers, protective armor of net or basket work, war clubs, spears and other weapons. In fine, they found themselves within a house, which afforded all that was necessary to their wants in that climate, and much that showed no inconsiderable degree of refinement and taste, but no one to challenge their intrusion.

The other houses presented a similar sight. They ransacked everywhere to find some one to explain the unaccountable desertion. There had been no haste. The inhabitants had not fled in fear. Everything was in its natural place and condition, just as were the household effects of the Pompeiians, when Vesuvius buried them in lava and ashes. But here the mystery was inexplicable. Evidently the desertion had not been very recent. Some weeks must have passed. Their own appearance, therefore, could not be connected with it. There was not an article that could properly belong to such domestic circles that was wanting, and all in the best condition and ready for use. Everything, however, that had life had been carefully removed. Even the usual tenants of deserted habitations, rats, were missing. The awe that almost mastered them in the silence of the open valley, no longer clung to them in the confined walls of human make. Curiosity was now uppermost. They talked freely and[50] loudly, and busied themselves with conjectures to solve the wonder, but with no other result than to weary their minds without any satisfactory answer.

“At all events,” said Juan, “all but drowned in the morning, with our brave caravel ground to pieces on the rocks, and most of our poor seamen a prey to the fishes, here we are at night well housed, with food at hand, and no greedy innkeeper’s face to suggest a long bill. For my part let’s to sleep. This is much more comfortable than campaigning amid the rocks of Tlascalla, with the prospect of a copper-headed lance finding its way between the ribs before one could sleep out his first nap.”

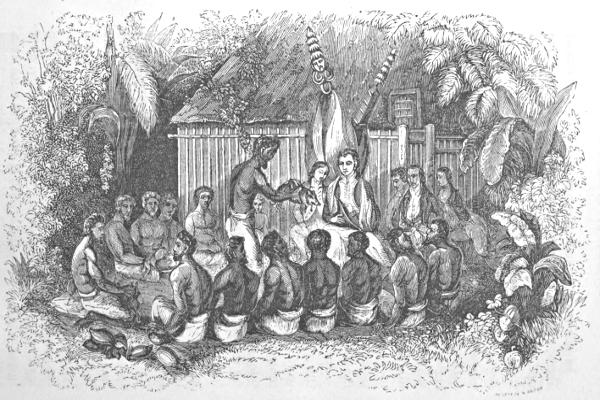

“You counsel rightly,” replied the priest, “but first let us unite in the Ave Maria.” So saying, he motioned to them to come into the open air, and holding up his crucifix he led the chant, while the others knelt and joined in. Then in the silence of the setting sun, there arose, for the first time in that unknown land, the hymn of praise to the mother of Jesus, woman deified and restored to her true nature as the hope and purifier of man, the type of God’s love to his own image. Softly and gently as Beatriz breathed the words “Ave purissima,” they seemed to fill all space, and borne on the air of the fast coming night, stole through the valley, along the waters, up the hill-sides and amid the trees, with a melody which made all Nature listen and repeat in notes still more penetrating, that thrilling symphony of peace and purity. The evening stars looked down gladly upon the little band, and shedding a harmonious radiance around the[51] singers, their hearts grew quiet and strong. Even Tolta felt its influence. As the seamen looked at the hideous idols about them, they fancied they saw them move in the night air as if they too bowed in worship to a spirit mightier than their own. It was indeed mightier; for it was the spirit of Love.

Mauna Kea, the highest mountain of Hawaii, occupies the northern portion of the island. In some places it descends in grassy slopes, sufficiently gentle to form plains, dotted here and there with the many armed pandanus and the thickly leaved kukui trees. From the resinous nuts of the latter the natives obtained their torches, while its rich foliage and grand proportions made it equally valuable for timber or shade.

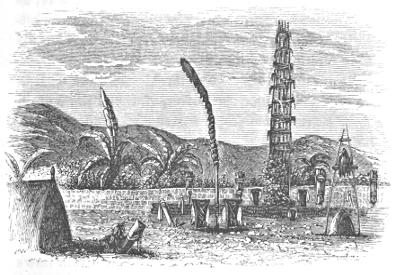

At the distance of some twenty miles from the bay where the caravel was wrecked, there was a level and extensive plain fringed with forests of the above named trees, and backed by the snow-topped mountains. The front afforded a wide-spread view of the ocean, the breezes from which, added to an elevation of several thousand feet, gave it a climate much cooler and more bracing than that of the coast. On this account, and from its natural beauties, it had from time immemorial been used by the Hawaiians as a spot on which to celebrate public games or sacred festivals. Its verdant and carefully irrigated soil afforded food for the numerous priests who belonged to the different[53] “heiaus” or temples to be seen within its limits. These were built of basaltic stones, some of which were of great size, and nicely adjusted together without cement, according to their natural fractures. Within the walls, which were massive and high, were the houses of the priests and the shrines where were deposited the most sacred images. Each chief of importance had his family temple, around which had grown up villages, to accommodate himself and retainers in their periodical visits to this upland region.

For a month previous to the wreck, many thousands of the islanders had been gathered under their chiefs to engage in their annual athletic games. Their principal object was, however, to celebrate the festival of Lono. Now Lono was one of those mythic beings so common in America and Polynesia, who in ages long gone by, after having done many notable things for the benefit of their fellow men, disappear like Moses in some inexplicable manner, leaving behind them a memory always green, and a sort of implied promise to return with greater benefits in store. Indeed, heroes of this character appear amid much traditionary fog, in the youth of almost all nations. In this instance, Lono had killed his wife in a fit of jealousy, instigated by a Hawaiian Iago out of malice equal to the Venetian’s. Love’s reaction and contrition drove him frantic.[54] After founding games in honor of his victim, he put out to sea in an oddly shaped canoe,—so the tradition runs,—promising to return some future day with many good things to enhance his welcome. Whether it was from love to him, or from faith in the expected increase of comforts and riches, that they so venerated his memory, I am at this day unable to say, but certain it is that a more popular god did not exist in Hawaii. His festival was therefore celebrated with peculiar unction.

On this occasion it had been honored with unusual solemnity, on account of the presence of the most powerful and best beloved chief of this island, whose territory embraced the fertile bay where the caravel went ashore.

It was the custom on the most sacred festivals to enforce perfect silence from man and beast during certain rites. While the festival lasted, peace was universal, property respected, and under the solemn influence of the magic “tabu,” human law and police seemed unnecessary; for there was implied in this simple word, if but its spirit were infringed, all the awful judgments, both temporal and supernatural, that the imagination could conceive, and even more, for the very uncertainty of the fate which was to attend its violation, added ten-fold force to its terrors. The simple symbol, therefore, which denoted the application of the tabu to any object, carried with it a power such as no civilized code ever exercised, and which the tortures of the Inquisition failed to establish.

The word tabu, as applied to religious matters,[55] was a ritual in itself. Hence when the high-priest set apart a certain time as tabu to Lono, the entire population knew what ceremonies were to be performed, and what was expected of each of them. During the present holidays it had been specially enjoined that the valley in which Kiana, a descendant of Lono and the supreme chief of more than half of Hawaii, resided, should be tabu from man and all domestic animals. For one month, profound silence was to rest upon it. Consequently, the inhabitants left for the uplands, taking with them every animal and fowl which they owned. It was owing to this tabu that Alvirez, when he explored the valley, met with such complete stillness amid all the outward signs of active life.

The very day, therefore, that Alvirez had so freely taken possession of the chief’s own quarters, Kiana with his people were on their march homeward. This chief, as is the aristocracy in general of Hawaii, was of commanding stature, some six feet six inches in height, finely proportioned, with round elastic limbs, not over muscular or too sinewy, like the North American Indian, but full, with a soft smooth skin and a bright olive complexion, which was not so dark, but that the blood at times deepened the color thereon. His face was strikingly handsome, being, like his body, of that happy medium between womanly softness and the more rugged development of manly strength, which indicates a well harmonized physical structure. In repose, one feared to see him move, lest the beauty of outline would be destroyed; but when in action, with his muscles quivering[56] with a hidden fire, his dark eyes flashing light, the full nostril of his race and rich sensual lip expanded with excitement, there was about him much that recalled the Apollo, particularly in the light step and eager haughty expression. His strength was prodigious. He had been known in battle, having broken his javelin, to seize an enemy by the leg and neck, and break his spine by a blow across his knees. Fierce he undoubtedly was to his foes, but there were in all his actions a pervading manliness and generosity, joined to a winning demeanor, which stamped him as one of nature’s gentlemen. No rival of his tribe disputed his authority, because all felt safer and better under his rule. By moral influence, rather than by force, all the other chiefs of this portion of Hawaii looked to him as their leader and umpire; so that without any of the dubious treaties and forms of a confederated government, they had all the advantages of one, while each remained free within his own territorial confines.

By nature humane, Kiana had infused into their general policy and domestic life a more liberal spirit towards inferiors, and a less servile feeling towards the priesthood. He held the latter, in general, in small esteem, perceiving how much they were disposed to corrupt the simplest power of nature into a hideous mythology, based upon fear and superstition, to the intent to enrich themselves at the expense of the people. As he also inherited the office of high-priest, his influence was the more effective, inasmuch as he set the example of neglecting all the requirements of their pagan ritual which[57] were cruel or oppressive, while the games and festivals, which tended to develop their physical powers and give them amusements, or to lighten their general labors, were sedulously cared for. His people were therefore happy and prosperous, and, at the date of this tale, exhibited an agreeable picture of a race blessed with a salubrious climate, a soil ample for all their simple wants, living almost patriarchally under a beloved chief, whose more intelligent mind, by example rather than argument, had influenced them to a form of idolatry which in its offerings of only fruits of the earth, to its symbolized phenomena or the images of departed men once venerated for their moral worth, in some degree connected their souls through refining influences with the Great Maker.

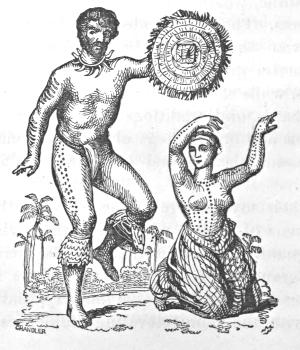

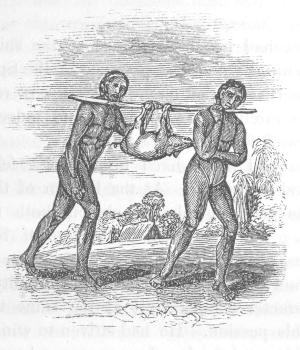

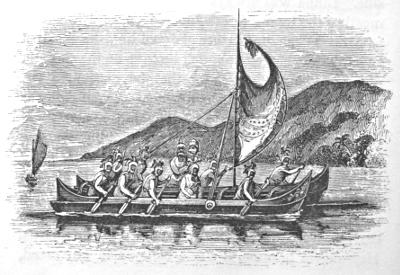

In closing the festival, the procession was formed with great state and solemnity, preparatory to its final departure from the sacred plain. First came a thousand men in regular files, armed with swords of sharks’ teeth and slings. Each had a laurel wreath on his head, and a tapa mantle of bright red thrown loosely over his shoulders. This corps led the way to the noise of rude drums and other barbarous music. Behind them marched a more numerous body in detached companies, armed with javelins and spears, and a species of wooden mace, which, dexterously used, becomes a formidable weapon. In addition, each man carried a dagger of the same material, from sixteen inches to two feet long. All wore helmets of wicker work, shaped like the Grecian casque and covered with[58] various colored feathers. These helmets in connection with their bright war cloaks, gave to the whole array a classical look not unworthy of the heroic days of Greece. The appearance of the men was martial, and their step firm and regular.

In the centre of their array there was a selected corps of one hundred young chiefs, armed with still better weapons. Their costume was also much richer than that of the common men. They wore scarlet feather cloaks and helmets. Conspicuous amid them, borne upon a litter hung about with crimson drapery, sat Kiana. His helmet was surmounted by a graceful crest from which lightly floated a plume taken from the long and beautiful feathers of the tropic bird. Both the helmet and his war cloak were made of brilliant yellow feathers, so small and delicate as to appear like scales of gold. These two articles were the richest treasures in the regalia of Hawaii. The birds from which the feathers are obtained,—one only from under each wing,—are found solely in the most inaccessible parts of the mountains and ensnared with great difficulty. Nearly one hundred and fifty years, or nine generations of Kiana’s ancestors had been occupied in collecting a sufficient number to make this truly regal helmet and cloak. This was the first occasion he had had to display them. He bore himself in consequence even more royally than ever before; for savage though he was, the pride of ancestry and the trappings of power warmed his blood as fully as if he had been a civilized ruler.

Immediately behind him was borne a colossal[59] image of Lono. It was carved with greater skill than common, and surrounded by a company of white-robed priests, chanting the “mele” or hymn, which had been composed upon his disappearance. At particular parts the whole people joined with a melancholy refrain, that gave a living interest to the story, and showed how forcible was the hold it had upon their imaginations. On either side of Kiana, were twelve men of immense size and strength, naked to their waist-cloths, two by two, bearing the “kahilis,” as were called the insignia of his rank. These were formed of scarlet feathers, thickly set, in the shape of a plume, of eighteen inches diameter, about ten feet high, and tipped to the depth of a foot with yellow feathers. With the handles, which were encircled with alternate rings of ivory or tortoise-shell, their entire height was twenty feet. As they towered and waved above the multitude, they conveyed an idea of state and grandeur inferior to nothing of the kind that has ever graced the ceremonies of the white man.

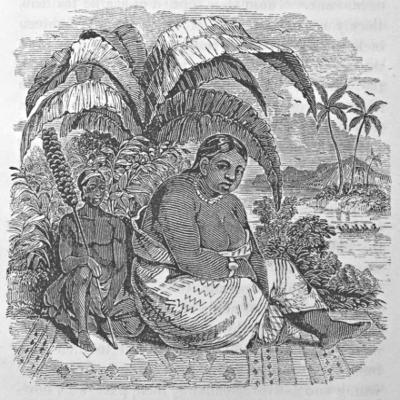

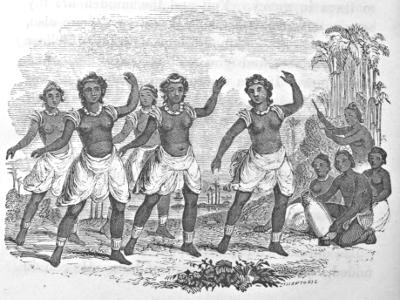

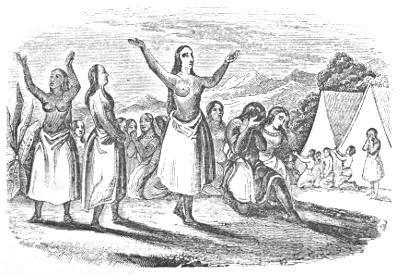

The women of his household followed close to the chief. Their aristocratic birth and breeding were manifest in their corpulency and haughty bearing. To exaggerate their size,—which was partly a criterion of noble blood—they had swelled their waists with voluminous folds of gaudy cloths, under the pressure of which, added to their own bulk, they waddled rather than walked. Helped by young and active attendants, their pace was, however, equal to the slow progress of the procession.[60] A numerous retinue of their own sex, bearing their tokens of rank, fans, fly-brushes, spittoons, sunscreens, and lighter articles of clothing, waited upon them. Some of these young women were gracefully formed, fair and voluptuous, with pleasant features, without any excess of flesh. In contrast with their mistresses, they might have been considered as beauties, as, indeed, they were the belles of Hawaii. Small, soft hands, delicate and tapering fingers, satin-like in their touch and gentle and pleasant to the shake, were common among all.

The women in general were a laughing, merry[61] set, prone to affection, finery, and sensuous enjoyment. But the lower orders were workers in the fullest sense, the men being their task-masters, treating them as an inferior caste by imposing upon their sex arbitrary distinctions in their food, domestic privileges, duties, and even religious rites, so that their social condition was wantonly degraded. Yet females were admitted to power and often held the highest rank.