THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN THE FAR EAST. Five Volumes. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00 each. The volumes sold separately. Each volume complete in itself.

| I. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Japan and China. |

| II. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Siam and Java. With Descriptions or Cochin-China, Cambodia, Sumatra, and the Malay Archipelago. |

| III. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Ceylon and India. With Descriptions of Borneo, the Philippine Islands, and Burmah. |

| IV. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey to Egypt and Palestine. |

| V. | Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey through Africa. |

THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN SOUTH AMERICA. Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey through Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Argentine Republic, and Chili; with Descriptions of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, and Voyages upon the Amazon and La Plata Rivers. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00.

THE BOY TRAVELLERS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey in European and Asiatic Russia, with Accounts of a Tour across Siberia, Voyages on the Amoor, Volga, and other Rivers, a Visit to Central Asia, Travels Among the Exiles, and a Historical Sketch of the Empire from its Foundation to the Present Time. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.00.

THE VOYAGE OF THE "VIVIAN" TO THE NORTH POLE AND BEYOND. Adventures of Two Youths in the Open Polar Sea. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $2.50.

HUNTING ADVENTURES ON LAND AND SEA. Two Volumes. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $2.50 each. The volumes sold separately. Each volume complete in itself.

| I. | The Young Nimrods in North America. |

| II. | The Young Nimrods Around the World. |

☞ Any of the above volumes sent by mail, postage prepaid, to any part of the United States or Canada, on receipt of the price.

Copyright, 1886, by Harper & Brothers.—All rights reserved.

In preparing this volume for the press, the author has followed very closely the plan adopted for "The Boy Travellers in the Far East," and also for his more recent work, "The Boy Travellers in South America." Accompanied by their versatile and accomplished mentor, Dr. Bronson, our young friends, Frank Bassett and Fred Bronson, journeyed from Vienna to Warsaw and St. Petersburg, and after an interesting sojourn in the latter city, proceeded to Moscow, the ancient capital of the Czars. From Moscow they went to Nijni Novgorod, to attend the great fair for which that city is famous, and thence descended the Volga to the Caspian Sea. On their way down the great river they visited the principal towns and cities along its banks, saw many strange people, and listened to numerous tales and legends concerning the races which make up the population of the great Muscovite Empire.

They visited the recently developed petroleum fields of the Caspian, and, after crossing that inland sea, made a journey in Central Asia to study certain phases of the "Eastern Question," and learn something about the difficulties that have arisen between England and Russia. Afterwards they travelled in the Caucasus, visited the Crimea, and bade farewell to the Empire as they steamed away from Odessa. Concerning the parts of Russia that they were unable to visit they gathered much information, and altogether their notes, letters, and memoranda would make a portly volume.

The author has been three times in the Russian Empire, and much of the country described by "The Boy Travellers" was seen and traversed by him. In his first journey he entered the Czar's dominions at Petropavlovsk in Kamtchatka, ascended the Amoor River through its entire navigable length, traversed Siberia from the Pacific Ocean to the Ural Mountains, and continuing thence to Kazan, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Warsaw, left the protection of the Russian flag eleven thousand miles from where he first went beneath it. His second visit included the Crimea[Pg 6] and other regions bordering the Black Sea, and his third was confined to Finland and other Baltic provinces.

In addition to his personal observations in Russia, the author has drawn upon the works of others. Many books of Russian travel and history have been examined; some of them have been mentioned in the text of the narrative, but it has not been practicable to refer to all. Indebtedness is hereby acknowledged to the following books: "Free Russia," by Hepworth Dixon; "Turkestan" and "Life of Peter the Great," by Hon. Eugene Schuyler; "A Ride to Khiva," by Col. Fred Burnaby; "Campaigning on the Oxus, and the Fall of Khiva," by J. A. Macgahan; "Life of Peter the Great" and "Life of Genghis Khan," by Jacob Abbott; "The Siberian Overland Route," by Alexander Michie; "Tent-life in Siberia," by George Kennan; "Reindeer, Dogs, and Snow-shoes," by Richard J. Bush; "The Invasion of the Crimea," by A. W. Kinglake; "Fred Markham in Russia," by W. H. G. Kingston; "The Knout and the Russians," by G. De Lagny; "The Russians at the Gates of Herat" and "The Region of the Eternal Fire," by Charles Marvin; "Travels in the Regions of the Upper and Lower Amoor" and "Oriental and Western Siberia," by Thomas W. Atkinson; and "The Russians at Home," by Sutherland Edwards. The author has also drawn upon several articles in Harper's Magazine, including his own series describing his journey through Siberia.

The publishers have kindly permitted the use of illustrations from their previous publications on the Russian Empire, in addition to those specially prepared for this book. As a result of their courtesy, the author has been able to present a "copiously illustrated" book, which is always a delight to the youthful eye.

T.W.K.

| CHAPTER I. | Departure from Vienna.—Frank's Letter.—A Farewell Promenade.—From Vienna to Cracow.—The Great Salt-mine of Wieliczka, and what was seen there.—Churches and Palaces Underground.—Voyage on a Subterranean Lake. |

| CHAPTER II. | Leaving Cracow.—The Russian Frontier.—The Police and the Custom-house.—Russian Censorship of Books and Papers.—Catching a Smuggler.—From the Frontier to Warsaw.—Sights and Incidents in the Capital of Poland.—From Warsaw to St. Petersburg. |

| CHAPTER III. | In the Streets of St. Petersburg.—Isvoshchiks and Droskies.—Counting in Russian.—Passports and their Uses.—On the Nevski Prospect.—Visiting the Church of Kazan.—The Russo-Greek Religion.—Unfavorable Position of St. Petersburg.—Danger of Destruction.—Great Inundation of 1824.—Statue of Peter the Great.—Admiralty Square.—The Sailors and the Statue. |

| CHAPTER IV. | Dinner in a Russian Restaurant.—Cabbage Soup, Fish Pies, and other odd Dishes.—The "Samovar" and its Uses.—Russian Tea-drinkers.—"Joltai Chai."—Alexander's Column.—Fortress of Sts. Peter and Paul.—Imperial Assassinations.—Sketches of the People.—Russian Police and their Ways. |

| CHAPTER V. | Number and Character of the Russian People.—Pan-Slavic Union.—St. Isaac's Church: its History and Description.—The Winter Palace and the Hermitage.—Sights in the Palace.—Catherine's Rules for her Receptions.—John Paul Jones in Russia.—The Crown Jewels and the Orloff Diamond.—Anecdotes of the Emperor Nicholas.—Relics of Peter the Great.—From Palace to Prison.—Tombs of Russia's Emperors.—A Monument and an Anecdote. |

| CHAPTER VI. | The Gostinna Dvor: its Extent and Character.—Peculiarity of Russian Shopping.—Curious Customs.—Old-clothes Market.—Hay-market.—Pigeons in Russian Cities.—Frozen Animals.—Church and Monastery of St. Alexander Nevski.—A Persian Train.—A Coffin of Solid Silver.—The Summer Garden.—Speaking to the Emperor.—Kriloff and his Fables.—Visit to a Russian Theatre.—"A Life for the Czar."—A Russian Comedy. |

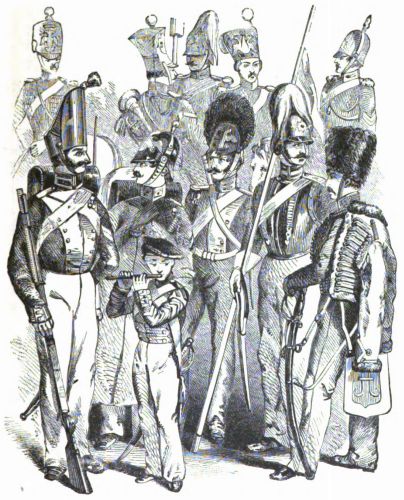

| CHAPTER VII. | Newspapers in Russia: their Number, Character, and Influence.—Difficulties of Editorial Life.—The Censorship.—An Excursion to Peterhof, Oranienbaum, and Cronstadt.—Sights in the Summer Palace.—Cronstadt and the Naval Station.—The Russian Navy.—The Russian Army: its Composition and Numbers.—The Cossacks.—Anecdotes of Russian Military Life. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | Visiting the University of St. Petersburg.—Education in Russia.—Primary and other Schools.—The System of Instruction.—Recent Progress in Educational Matters.—Universities in the Empire: their Number and Location.—Religious Liberty.—Treatment of the Jews.—The Islands of the Neva, and what was seen there.—In a "Traktir."—Bribery among Russian Officials. |

| CHAPTER IX. | Studies of St. Petersburg.—Mujiks.—"The Imperial Nosegay."—A Short History of Russian Serfdom: its Origin, Growth, and Abuses.—Emancipation of the Serfs.—Present Condition of the Peasant Class.—Seeing the Emperor.—How the Czar appears in Public.—Public and Secret Police: their Extraordinary Powers.—Anecdotes of Police Severity.—Russian Courts of Law. |

| CHAPTER X. | Winter in Russia.—Fashionable and other Furs.—Sleighs and Sledges.—No Sleigh-bells in Russian Cities.—Official Opening of the Neva.—Russian Ice-hills.—"Butter-week."—Kissing at Easter.—An Active Kissing-time.—Russian Stoves and Baths.—Effects of Severe Cold.—The Story of the Frozen Nose.—How Men are Frozen to Death. |

| CHAPTER XI. | Leaving St. Petersburg.—Novgorod the Great: its History and Traditions.—Rurik and his Successors.—Barbarities of John the Terrible.—Early History of Russia.—An Imperial Bear-hunt.—Origin of the House of Romanoff.—"A Life for the Czar."—Railways in Russia from Novgorod to Moscow. |

| CHAPTER XII. | First Impressions of Moscow.—Undulations of the Ground.—Irregularity of the Buildings, and the Cause thereof.—Napoleon's Campaign in Russia.—Disaster and Retreat.—The Burning of Moscow.—The Kremlin: its Churches, Treasures, and Historical Associations.—Anecdotes of Russian Life.—The Church of St. Basil. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | The Great Theatre of Moscow.—Operatic Performances.—The Kitai Gorod and Gostinna Dvor.—Romanoff House and the Romanoff Family.—Sketch of the Rulers of Russia.—Anecdotes of Peter the Great and others.—Church of the Saviour.—Mosques and Pagodas.—The Museum.—Riding-school.—Suhareff Tower.—Traktirs.—Old Believers.—The Sparrow Hills and the Simonoff Monastery. |

| CHAPTER XIV. | A Visit to the Troitska Monastery, and what was seen there.—Curious Legends.—Monks at Dinner.—European Fairs.—The Great Fair at Nijni Novgorod.—Sights and Scenes.—Minin's Tomb and Tower.—Down the Volga by Steamboat.—Steam Navigation on the great River.—Kazan, and what was seen there.—The Route to Siberia. |

| CHAPTER XV. | Avatcha Bay, in Kamtchatka.—Attack upon Petropavlovsk by the Allied Fleet.—Dogs and Dog-driving.—Rapid Travelling with a Dog-team.—Population and Resources of Kamtchatka.—Reindeer and their Uses.—The Amoor River.—Native Tribes and Curious Customs.—Tigers in Siberia.—Navigation of the Amoor.—Overland Travelling in Siberia.—Riding in a Tarantasse.—A Rough Road.—An Amusing Mistake.—From Stratensk to Nertchinsk.—Gold-mining in Siberia. |

| CHAPTER XVI. | The Exiles of Siberia.—The Decembrists and their Experience.—Social Position of Exiles.—Different Classes of Exiles and their Sentences.—Criminals and Politicals.—Degrees of Punishment.—Perpetual Colonists.—How Exiles Travel.—Lodging-houses and Prisons.—Convoys.—Thrilling Story of an Escape from Siberia.—Secret Roads.—How Peasants Treat the Exiles.—Prisoners in Chains. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | Character of the Siberian Population.—Absence of Serfdom, and its Effect.—A Russian Fête.—Amusements of the Peasantry.—Courtship and Marriage.—Curious Customs.—Whipping a Wife.—Overland through Siberia again.—Chetah and the Bouriats.—In a Bouriat Village.—Verckne Udinsk.—Siberian Robbers.—Tea-trains and Tea-trade.—Kiachta.—Lodged by the Police.—Trade between Russia and China. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | General Aspects of Mai-mai-chin.—Dinner with a Chinese Governor.—A Theatrical Performance.—Lake Baikal: its Remarkable Features.—A Wonderful Ride.—Irkutsk: its Population, Size, and Peculiarities.—Social Gayeties.—Preparations for a long Sleigh-ride.—List of Garments.—Varieties of Sleighs.—Farewell to Irkutsk.—Sleighing Incidents.—Food on the Road.—Siberian Mails.—Advantages of Winter Travelling.—Sleighing on bare Ground.—A Snowless Region.—Krasnoyarsk. |

| CHAPTER XIX. | Position and Character of Krasnoyarsk.—A Lesson in Russian Pronunciation.—Market Scene.—Siberian Trees.—The "Oukhaba."—A New Sensation.—Road-fever and its Cause.—An Exciting Adventure with Wolves.—How Wolves are Hunted.—From Krasnoyarsk to Tomsk.—Steam Navigation in Siberia.—Barnaool.—Mines of the Altai.—Tigers and Tiger Stories.—the "Bouran."—Across the Baraba Steppe.—Tumen and Ekaterineburg.—From Europe to Asia.—Perm, Kazan, and Nijni Novgorod.—End of the Sleigh-ride. |

| CHAPTER XX. | Down the Volga again.—Russian Reception Ceremony.—Simbirsk, Samara, and Saratov.—German Settlers on the Volga.—Don Cossacks.—Astrachan.—Curious Population.—Voyage on the Caspian Sea.—The Caspian Petroleum Region.—Tank-steamers.—Interesting Facts and Figures of the New Petrolia.—Present Product of the Baku Oil-fields.—Excursion to Balakhani, and Visit to the Oil-wells.—Temples of the Fire-worshippers.—Antiquity of the Caspian Petroleum Region.—Marco Polo and other Authorities. |

| CHAPTER XXI. | A Glance at Central Asia.—Russian Conquest in Turkestan.—War and Diplomacy among the Kirghese Tribes.—Russian Taxes and their Collection.—Turcoman and Kirghese Raids.—Prisoners sold into Slavery.—Fortified Villages and Towers of Refuge.—Commerce in Turkestan.—Jealousy of Foreigners.—Travels of Vámbéry and Others.—Vámbéry's Narrow Escape.—Turcoman Character.—Payments for Human Heads.—Marriage Customs among the Turcomans.—Extent and Population of Central Asia. |

| CHAPTER XXII. | Frank and Fred in the Turcoman Country.—The Trans-Caspian Railway.—Skobeleff's Campaign, and the Capture of Geok Tepé.—English Jealousy of Russian Advances.—Rivers of Central Asia.—The Oxus and Jaxartes.—Agriculture by Irrigation.—Khiva, Samarcand, and Bokhara.—A Ride on the Trans-Caspian Railway.—Statistics of the Line.—Kizil Arvat, Askabad, and Sarakhs.—Route to Herat and India.—Turcoman Devastation.—The Afghan Boundary Question.—How Merv was Captured.—O'Donovan and MacGahan: their Remarkable Journeys.—Railway Route from England to India.—Return to Baku. |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | Baku to Tiflis.—The Capital of the Caucasus.—Mountain Travelling.—Crossing the Range.—Petroleum Locomotives.—Batoum and its Importance.—Trebizond and Erzeroom.—Sebastopol and the Crimea.—Short History of the Crimean War.—Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.—Battles in the Crimea and Siege of Sebastopol.—Visiting the Malakoff and Redan Forts.—View of the Battle-fields.—Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava.—Present Condition of Sebastopol.—Odessa.—Arrival at Constantinople.—Frank's Dream.—The End. |

"Here are the passports at last."

"Are you sure they are quite in order for our journey?"

"Yes, entirely so," was the reply; "the Secretary of Legation examined them carefully, and said we should have no trouble at the frontier."

"Well, then," a cheery voice responded, "we have nothing more to do until the departure of the train. Five minutes will complete the packing of our baggage, and the hotel bill is all settled. I am going for a walk through the Graben, and will be back in an hour."

So saying, our old acquaintance, Doctor Bronson, left his room in the Grand Hotel in Vienna and disappeared down the stairway. He was followed, a few minutes later, by his nephew, Fred Bronson, who had just returned from a promenade, during which he had visited the American Legation to obtain the passports which were the subject of the dialogue just recorded.

At the door of the hotel he was joined by his cousin, Frank Bassett. The latter proposed a farewell visit to the Church of St. Stephen, and[Pg 16] also a short stroll in the Graben, where he wished to make a trifling purchase. Fred assented, and they started at once.

They had not gone far before Fred perceived at a window the face of a girl busily engaged in writing. He paused a moment, and then suggested to Frank that he wished to return to the hotel in time to write a letter to his sister before the closing of the mail. "I really believe," said he, "that I should have neglected Mary this week if I had not been reminded by that girl in the window and her occupation."

Frank laughed as he rejoined that he had never yet known his cousin to forget his duty, and it[Pg 17] would have been pretty sure to occur to him that he owed his sister a letter before it was too late for writing it.

They made a hasty visit to the church, which is by far the finest religious edifice in Vienna, and may be said to stand in the very heart of the city. Fred had previously made a note of the fact that the church is more than seven hundred years old, and has been rebuilt, altered, and enlarged so many times that not much of the original structure remains. On the first day of their stay in Vienna the youths had climbed to the top of the building and ascended the spire, from which they had a magnificent view of the city and the country which surrounds it. The windings of the Danube are visible for many miles, and there are guides ready at hand to point out the battle-fields of Wagram, Lobau, and Essling. Our young friends had a good-natured discussion about the height of the spire of St. Stephen's; Frank claimed that his guide-book gave the distance from the ground to the top of the cross four hundred and fifty-three feet, while Fred contended, on the authority of another guide-book, that it was four hundred and sixty-five feet. Authorities differ considerably as to the[Pg 18] exact height of this famous spire, which does not appear to have received a careful measurement for a good many years.

From the church the youths went to the Graben, the famous street where idlers love to congregate on pleasant afternoons, and then they returned to the hotel. Fred devoted himself to the promised letter to his sister. With his permission we will look over his shoulder as he writes, and from the closing paragraph learn the present destination of our old friends with whom we have travelled in other lands.[1]

"We have been here a week, and like Vienna very much, but are quite willing to leave the city for the interesting tour we have planned. We start this evening by the Northern Railway for a journey to and through Russia; our first stopping-place will be at the nearest point on the railway for reaching the famous salt-mines of Wieliczka. You must pronounce it We-litch-ka, with the accent on the second syllable. I'll write you from there; or, if I don't have time to do so at the mines, will send you a letter from the first city where we stop for more than a single day. We have just had our passports indorsed by the Russian minister for Austria—a very necessary proceeding, as it is impossible to get into Russia without these documents. Until I next write you, good-by."

The travellers arrived at the great Northern Railway station of Vienna in ample season to take their tickets and attend to the registration of their baggage. The train carried them swiftly to Cracow—a city which has had a prominent place in Polish annals. It was the scene of several battles, and was for a long time the capital of the ancient kingdom of Poland. Frank made the following memoranda in his note-book:

"Cracow is a city of about fifty thousand inhabitants, of whom nearly[Pg 19] one-third are Israelites. It stands on the left bank of the Vistula, on a beautiful plain surrounded by hills which rise in the form of an amphitheatre. In the old part of the city the streets are narrow and dark, and cannot be praised for their cleanliness; but the new part, which lies outside the ancient defences, is quite attractive. The palace is on the bank of the river, and was once very pretty. The Austrians have converted it into a military barrack, after stripping it of all its ornaments, so that it is now hardly worth seeing. There are many fine churches in Cracow, but we have only had time to visit one of them—the cathedral.

"In the cathedral we saw the tombs of many of the men whose names are famous in Polish history. Polish kings and queens almost by the dozen are buried here, and there is a fine monument to the memory of St. Stanislaus. His remains are preserved in a silver coffin, and are the object of reverence on the part of those who still dream of the ultimate liberation of Poland, and its restoration to its old place among the kingdoms of the world.

"We drove around the principal streets of Cracow, and then out to the tumulus erected to the memory of the Polish patriot, Kosciusko. You remember the lines in our school reader,

"'Hope for a season bade the world farewell,

And freedom shrieked as Kosciusko fell.'

"We were particularly desirous to see this mound. It was made of earth brought from all the patriotic battle-fields of Poland at an enormous expense, which was largely borne by the people of Cracow. The monument is altogether one hundred and fifty feet high, and is just inside the line of fortifications which have been erected around the city. The Austrians say these fortifications are intended to keep out the Russians; but[Pg 20] it is just as likely that they are intended to keep the Poles from making one of the insurrections for which they have shown so great an inclination during the past two or three centuries.

"As we contemplated the monument to the famous soldier of Poland, we remembered his services during our Revolutionary war. Kosciusko entered the American army in 1776 as an officer of engineers, and remained with General Washington until the close of the war. He planned the fortified camp near Saratoga, and also the works at West Point. When our independence was achieved he returned to Poland, and after fighting for several years in the cause of his country, he made a brief visit to America, where he received much distinction. Then he returned again to Europe, lived for a time in France, and afterwards in Switzerland, where he died in 1817. The monument we have just visited does not cover his grave, as he was buried with much ceremony in the Cathedral of Cracow."

"Why don't you say something about the Jewish quarter of Cracow," said Fred, when Frank read what he had written, and which we have given above.

"I'll leave that for you," was the reply. "You may write the description while I make some sketches."

"I'm agreed," responded Fred. "Let's go over the ground together and pick out what is the most interesting."

Away they went, leaving Doctor Bronson with a gentleman with whom he had formed an acquaintance during their ride from the railway to the hotel. The Doctor was not partial to a walk in the Jews' quarter, and said he was willing to take his knowledge of it at second-hand.

On their way thither the youths stopped a few minutes to look at the Church of St. Mary, which was built in 1276, and is regarded as a fine specimen of Gothic architecture. It is at one side of the market-place, and presents a picturesque appearance as the beholder stands in front of it.

The Jews' quarter is on the opposite side of the river from the principal part of the city, and is reached by a bridge over the Vistula. At every step the youths were beset by beggars. They had taken a guide from the hotel, under the stipulation that he should not permit the beggars to annoy them, but they soon found it would be impossible to secure immunity from attack without a cordon of at least a dozen guides. Frank pronounced the beggars of Cracow the most forlorn he had ever seen, and Fred thought they were more numerous in proportion to the population than in any other city, with the possible exception of Naples. Their ragged and starved condition indicated that their distress was real, and more than once our young friends regretted having brought themselves face to face with so much misery that they were powerless to relieve.

Frank remarked that there was a similarity of dress among the Jews of Cracow, as they all wore long caftans, or robes, reaching nearly to the heels. The wealthy Jews wear robes of silk, with fur caps or turbans, while the poorer ones must content themselves with cheaper material, according to their ability. The guide told the youths that the men of[Pg 22] rank would not surround their waists with girdles as did the humbler Jews, and that sometimes the robes of the rich were lined with sable, at a cost of many hundreds of dollars.

Fred carefully noted the information obtained while Frank made the sketches he had promised to produce. They are by no means unlike the sketches that were made by another American traveller (Mr. J. Ross Browne), who visited Cracow several years before the journey of our friends.

"But there's one thing we can't sketch, and can't describe in writing," said Fred, "and that's the dirt in the streets of this Jews' quarter of Cracow. If Doctor Bronson knew of it I don't wonder he declined to come[Pg 23] with us. No attempt is made to keep the place clean, and it seems a pity that the authorities do not force the people into better ways. It's as bad as any part of Canton or Peking, and that's saying a great deal. I wonder they don't die of cholera, and leave the place without inhabitants."

In spite of all sorts of oppression, the Jews of Cracow preserve their distinctiveness, and there are no more devout religionists in the world than this people. The greater part of the commerce of the city is in their hands, and they are said to have a vast amount of wealth in their possession. That they have a large share of business was noticed by Fred, who said that from the moment they alighted from the train at the railway-station they were pestered by peddlers, guides, money-changers, runners for shops, beggars, and all sorts of importunate people from the quarter of the city over the Vistula. An hour in the Jews' quarter gratified their curiosity, and they returned to the hotel.

There is a line of railway to the salt-mines, but our friends preferred to go in a carriage, as it would afford a better view of the country, and enable them to arrange the time to suit themselves. The distance is about nine miles, and the road is well kept, so that they reached the mines in little more than an hour from the time of leaving the hotel. The road is through an undulating country, which is prettily dotted with farms, together with the summer residences of some of the wealthier inhabitants of Cracow.

On reaching the mines they went immediately to the offices, where it was necessary to obtain permission to descend into the earth. These offices are in an old castle formerly belonging to one of the native princes, but long ago turned into its present practical uses. Our friends were accompanied by a commissioner from the hotel where they were lodged in Cracow; he was a dignified individual, who claimed descent from one of the noble families of Poland, and the solemnity of his visage was increased[Pg 24] by a huge pair of spectacles that spanned his nose. Frank remarked that spectacles were in fashion at Wieliczka, as at least half the officials connected with the management of the salt-mines were ornamented with these aids to vision.

A spectacled clerk entered the names of the visitors in a register kept for the purpose, and issued the tickets permitting them to enter the mines. Armed with their tickets, they were conducted to a building close to the entrance of one of the mines, and ushered into the presence of the inspector-general of the works. He was also a wearer of spectacles, and the rotundity of his figure indicated that the air and food of the place had not injured him.

"The inspector-general received us politely—in fact everybody about the place was polite enough for the most fastidious taste," said Frank in his note-book—"and after a short conversation he called our attention to the robes which had been worn by imperial and royal visitors to the mines. The robes are richly embroidered, and every one bears a label telling when and by whom it was worn. The inspector-general treated the garments with almost as much reverence as he would have shown to the personages named on the labels. We realized that it was proper to regard them with respect, if we wished to have the good-will of this important official, and therefore we appeared to be dumb with amazement as he went through the list. When the examination was ended we were provided with garments for the descent. Evidently we were not regarded with the same awe as were the kings and emperors that had preceded us, as our robes were of a very common sort. They were like dressing-gowns, and reached nearly to our heels, and our heads were covered with small woollen caps. I do not believe they were labelled with our names and kept in glass cases after our departure.

"I made a sketch of our guide after he was arrayed in his underground[Pg 25] costume and ready to start. Fred sketched the inspector-general while the latter was talking to the Doctor. The portrait isn't a bad one, but I think he has exaggerated somewhat the rotund figure of the affable official.

"From the office we went to the entrance of one of the shafts. It is in a large building, which contains the hoisting apparatus, and is also used as a storehouse. Sacks and barrels of salt were piled there awaiting transportation to market, and in front of the building there were half a dozen wagons receiving the loads which they were to take to the railway-station. The hoisting apparatus is an enormous wheel turned by horse-power; the horses walk around in a circle, as in the old-fashioned cider-mill of the Northern States, or the primitive cotton-gin of the South. Our guide said there were more than twenty of these shafts, and there was also a stairway, cut in the solid earth and salt, extending to the bottom of the mine. We had proposed to descend by the stairway, but the commissioner strenuously advised against our doing so. He said the way was dark and the steps were slippery, as they were wet in many places from the water trickling through the earth. His arguments appeared reasonable, and so we went by the shaft.

"The rope winds around a drum on the shaft supporting the wheel, and then passes through a pulley directly over the place where we were to descend. The rope is fully two inches in diameter, and was said to be capable of bearing ten times the weight that can ever be placed upon it in ordinary use. It is examined every morning, and at least once a week it is tested with a load of at least four times that which it ordinarily carries. When it shows any sign of wear it is renewed; and judging from all we could see, the managers take every precaution against accidents.

"Smaller ropes attached to the main one have seats at the ends. There are two clusters of these ropes, about twenty feet apart, the lower one being intended for the guides and lamp-bearers, and the upper for visitors and officials. Six of us were seated in the upper group. It included our party of four and two subordinate officials, who accompanied us on our journey and received fees on our return; but I suppose they would scorn to be called guides.

"There is a heavy trap-door over the mouth of the shaft, and the rope plays freely through it. The guides and lamp-bearers took their places at the end of the rope; then the door was opened and they were lowered down, and the door closed above them. This brought the upper cluster of ropes in position for us to take our places, which we did under[Pg 26] the direction of the officials who accompanied us. When all was ready the signal was given, the trap-door was opened once more, and we began our downward journey into the earth.

"As the trap-door closed above us, I confess to a rather uncanny feeling. Below us gleamed the lights in the hands of the lamp-bearers, but above there was a darkness that seemed as though it might be felt, or sliced off with a knife. Nobody spoke, and the attention of all seemed to be directed to hanging on to the rope. Of course the uppermost question in everybody's mind was, 'What if the rope should break?' It doesn't take long to answer it; the individuals hanging in that cluster below the gloomy trap-door would be of very little consequence in a terrestrial way after the snapping of the rope.

"We compared notes afterwards, and found that our sensations were pretty much alike. The general feeling was one of uncertainty, and each one asked himself several times whether he was asleep or awake. Fred said a part of the journey was like a nightmare, and the Doctor said he had the same idea, especially after the noise of the machinery was lost in the distance and everything was in utter silence. For the first few moments we could hear the whirring of the wheel and the jar of the machinery; but very soon these sounds disappeared, and[Pg 27] we glided gently downward, without the least sensation of being in motion. It seemed to me not that we were descending, but that the walls of the shaft were rising around us, while our position was stationary.

"Contrary to expectation, we found the air quite agreeable. The official who accompanied us said it was peculiarly conducive to health; and many of the employés of the mines had been at work there forty or fifty years, and had never lost a day from illness. We had supposed it would be damp and cold, but, on the contrary, found it dry and of an agreeable temperature, which remains nearly the same all through the year. No doubt the salt has much to do with this healthy condition. Occasionally[Pg 28] hydrogen gas collects in some of the shafts which are not properly ventilated, and there have been explosions of fire-damp which destroyed a good many lives. These accidents were the result of carelessness either of the miners or their superintendents, and since their occurrence a more rigid system of inspection has been established.

"We stopped at the bottom of the shaft, which is about three hundred feet deep; there we were released from our fastenings and allowed to use our feet again. Then we were guided through a perfect labyrinth of passages, up and down ladders, along narrow paths, into halls spacious enough for the reception of an emperor, and again into little nooks where men[Pg 29] were occupied in excavating the salt. For several hours we wandered there, losing all knowledge of the points of compass, and if we had been left to ourselves our chances of emerging again into daylight would have been utterly hopeless.

"And here let me give you a few figures about the salt-mines of Wieliczka. I cannot promise that they are entirely accurate, but they are drawn from the best sources within our reach. Some were obtained from the under-officials of the mines who accompanied us, and others are taken from the work of previous writers on this subject.

"The salt-mine may be fairly regarded as a city under the surface of the earth, as it shelters about a thousand workmen, and contains chapels, churches, railways, stables, and other appurtenances of a place where men dwell. In fact it is a series of cities, one above the other, as there are four tiers of excavations, the first being about two hundred feet below the surface, and the lowest nearly two thousand. The subterranean passages and halls are named after various kings and emperors who have visited them, or who were famous at the time the passages were opened, and altogether they cover an area of several square miles. In a general way the salt-mines of Wieliczka may be said to be nearly two miles square; but the ends of some of the passages are more than two miles from the entrance of the nearest shaft. The entire town of Wieliczka lies above the mines which give occupation to its inhabitants.

"There is probably more timber beneath the surface at Wieliczka than above it, as the roofs of the numerous passages are supported by heavy beams; and the same is the case with the smaller halls. In the larger halls such support would be insufficient, and immense columns of salt are left in position. In several instances these pillars of salt have been replaced by columns of brick or stone, as they would be[Pg 30] liable to be melted away during any accidental flooding of the mine, and allow the entire upper strata to tumble in. This has actually happened on one occasion, when a part of the mine was flooded and serious damage resulted.

"Our guide said the length of the passages, galleries, and halls was nearly four hundred English miles, and the greatest depth reached was two thousand four hundred feet. If we should visit all the galleries and passages, and examine every object of interest in the mines, we should be detained there at least three weeks. Not a single one of all the workmen had been in every part of all the galleries of the mine, and he doubted if there was any officer attached to the concern who would not be liable to be lost if left to himself.

"Nobody knows when these mines were discovered; they were worked in the eleventh century, when they belonged to the kingdom of Poland, and an important revenue was derived from them. In the fourteenth century Casimir the Great established elaborate regulations for working the mines, and his regulations are the basis of those which are still in force, in spite of numerous changes. In 1656 they were pledged to Austria, but were redeemed by John Sobieski in 1683. When the first partition of Poland took place, in 1772, they were handed over to Austria, which has had possession of them ever since, with the exception of the short period from 1809 to 1815.

"While the mines belonged to Poland the kings of that country obtained a large revenue from them. For two or three centuries this revenue was sufficiently large to serve for the endowment of convents and the dowries of the members of the royal family. The Austrian Government has obtained a considerable revenue from these mines, but owing to the modern competition with salt from other sources, it does not equal the profit of the Polish kings.

"Except when reduced by accidents or other causes, the annual production of salt in these mines is about two hundred millions of pounds, or one hundred thousand tons. The deposit is known to extend a long distance, and the Government might, if it wished, increase the production to any desired amount. But it does not consider it judicious to do so, and is content to keep the figures about where they have been since the beginning of the century. The salt supplies a considerable area of country; a large amount, usually of the lower grades, is sent into Russia, and the finer qualities are shipped to various parts of the Austrian Empire.

"We asked if the workmen lived in the mines, as was currently reported, and were told they did not. 'They would not be allowed to do[Pg 31] so, even if they wished it,' said our guide. 'By the rules of the direction the men are divided into gangs, working eight hours each, and all are required to go to the surface when not on duty. In ancient times it was doubtless the case that men lived here with their families. At one time the mines were worked by prisoners, who did not see daylight for months together, but nothing of the kind has occurred for more than a century at least.'

"Several times in our walk we came upon little groups of men working in the galleries; and certainly they were not to be envied. Sometimes they were cutting with picks against perpendicular walls, and at others they were lying flat on their backs, digging away at the roof not[Pg 32] more than a foot or two above their heads. The shaggy lamp-bearers—generally old men unable to perform heavy work—stood close at hand, and the glare of the light falling upon the flashing crystals of salt that flew in the air, and covered the half-naked bodies of the perspiring workmen, made a picture which I cannot adequately describe. I do not know that I ever looked upon a spectacle more weird than this.

"We had expected to see the men in large gangs, but found that they were nearly always divided into little groups. One would think they would prefer any other kind of occupation than this, but our guide told us that the laborers were perfectly free to leave at any time, just as though they were in the employ of a private establishment. There were plenty of men who would gladly fill their places, and frequently they had applications for years in advance. As prices go in Austria, the pay is very good, the men averaging from twenty to fifty cents a day. As far as possible they are paid by the piece, and not by time—the same as in the great majority of mines all over the world.

"But the horses which draw the cars on the subterranean railways are[Pg 33] not regarded with the same care as the men. They never return to the light of day after once being lowered into the mine. In a few weeks after arriving there a cataract covers their eyes and the sight disappears. By some this result is attributed to the perpetual darkness, and by others to the effect of the salt. It is probably due to the former, as the workmen do not appear to suffer in the same way. Whether they would become blind if continually kept there is not known, and it is to be hoped that no cruel overseer will endeavor to ascertain by a practical trial.

"Every time we came upon a group of workmen they paused in their labors and begged for money. We had provided ourselves with an abundance of copper coins before descending into the mine, and it was well we did so, as they generally became clamorous until obtaining what they wanted. Fortunately they were satisfied with a small coin, and did not annoy us after once being paid.

"I cannot begin to give the names of all the halls, galleries, and passages we went through, and if I did, it would be tedious. We wandered up and down, down and up, forward and backward, until it seemed as if there was no end to the journey. And to think we might have been there three weeks without once repeating our steps! I will mention at random some of the most interesting of the things we saw. To tell the whole story and give a full description of this most wonderful salt-mine in the world would require a volume.

"The chamber of Michelwic was the first of the large halls that we entered, and was reached after a long journey through winding passages and along foot-paths that sometimes overhung places where it was impossible for the eye, aided only by the light of the lamps, to ascertain the[Pg 34] depth of the openings below. In some of the dangerous places there was a rail to prevent one from falling over; but this was not always the case, and you may be sure we kept on the safe side and close to the wall.

"In the hall we were treated to a song by one of the mining over-seers, an old soldier who had lost an arm in some way that was not explained to us. He had an excellent voice that ought to have secured him a good place in the chorus of an opera troupe. He sang a mining song in quite a melodramatic style; and as he did so the notes echoed and re-echoed through the hall till it seemed they would never cease. In the centre of the hall is a chandelier cut from the solid salt, and on grand occasions this chandelier is lighted and a band of music is stationed at one end of the vast space. Its effect is said to be something beyond description, and, judging from the effect of the overseer's voice, I can well believe it.

"From this hall we went through a series of chambers and galleries named after the royal and imperial families of Poland and Austria, passing chapels, shrines, altars, and other things indicating the religious character of the people employed in the mines or controlling them, together[Pg 35] with many niches containing statues of kings, saints, and martyrs, all hewn from the solid salt. Some of the statues are rudely made, but the most of them are well designed and executed. In some of the chapels worshippers were kneeling before the altars, and it was difficult to realize that we were hundreds of feet below the surface of the earth.

"By-and-by our guide said we were coming to the Infernal Lake. The lamp-bearers held their lights high in the air, and we could see the reflection from a sheet of water, but how great might be its extent was impossible to guess. As we approached the edge of the water a boat emerged from the gloom and came towards us. It was a sort of rope ferry, and we immediately thought of the ferry-boat which the ancients believed was employed to carry departed spirits across the river Styx. Certainly the darkness all around was Stygian, and the men on the boat might have been Charon's attendants.

"We passed down a few steps, entered the boat, and were pulled away from shore. In less than a minute nothing but the little circle of water around us was visible; the sides of the cavern echoed our voices and every other sound that came from our boat. In the middle of the lake we paused to observe the effect of the sound caused by the waves created by the rocking of the boat. It reverberated through the cavern and away into the galleries, and seemed as though it would last forever. When this sensation was exhausted we moved on again. Doctor Bronson asked the guide how far it was to the other end of the lake, but before the answer was spoken we had a fresh surprise.

"There was a flash of light from a point high above us, and almost at the same instant another, a little distance ahead. The latter assumed the form of an arch in red fire, displaying the greeting 'Glück-auf!' or 'Good-luck!' though this is not the literal translation. We passed under this[Pg 36] arch of red fire, and as we did so the words 'Glück-auf! Glück-auf!' were shouted from all around, and at the same time flashes of fire burst from a dozen places above the lake. We shouted 'Glück-auf!' in reply, and then the voices from the mysterious recesses seemed to be quadrupled in number and volume. The air was filled with flashes of light, and was everywhere resonant with the words of the miners' welcome.

"At the other end of the lake there was a considerable party waiting to receive us, and of course there was a liberal distribution of coin to everybody. I ought to have said at the outset that we arranged to pay for[Pg 37] the illumination of the lake and also of certain specified halls, in addition to the compensation of the guides. The illuminations are entirely proportioned to the amount that the visitors are willing to give for them. It is a good plan to unite with other visitors, and then the individual cost will not be heavy. Twenty dollars will pay for a very good illumination, and fifty dollars will secure something worthy of a prince, though not a first-class one.

"They showed us next through more winding passages, and came at length to the Grand Saloon of Entertainment; which is of immense extent, and has no less than six large chandeliers hanging from the roof. It is lighted on the occasion of the visit of a king or emperor (of course he[Pg 38] has to pay the bill), and the effect is said to be wonderful. There is an alcove at one end, with a throne of green and ruby-colored salt, whereon the emperor is seated. A blaze of light all through the hall is reflected from the myriad crystals of salt which form the roof and sides; the floor is strewn with sparkling salt; the columns are decorated with evergreens; festoons of flags abound through the place; and a band of music plays the airs appropriate to the hall and the guest.

"The workmen and their families assemble in their holiday dress, and when the music begins the whole party indulges in the Polish national dance. It is a strange spectacle, this scene of revelry five hundred feet below the surface of the earth, and probably among the sights that do not come often before the Imperial eyes. These spectacles must be arranged to order, and for weeks before an Imperial or Royal visit a great many hands are engaged in making the necessary preparations. From all I heard of these festivals, I would willingly travel many hundred miles to see one of them.

"By means of the illuminating materials that we brought with us, we were able to get an approximate idea of the character of one of these gala spectacles. After our last Bengal-light had been burned, we continued our journey, descending to the third story by many devious ways, and finally halting in a chamber whose roof was not less than a hundred feet above us.

"'Do you know where you are?' said our guide.

"Of course we answered that we did not.

"'Well,' said he, 'you are directly beneath the lake which we sailed over in a boat a little while ago. If it should break through we should all be drowned, dead.'

"We shuddered to think what might be our fate if the lake should[Pg 39] spring a leak. It did break out at one time and flooded many of the galleries, and for a long while work in all the lower part of the mine was suspended. There have been several fires, some of them causing the loss of many lives; but, on the whole, considering the long time the mine has been opened and the extent of the works, the accidents have been few.

"The deepest excavation in the mine is nearly seven hundred feet below the level of the sea. We did not go there, in fact we did not go below the third story, as we had seen quite enough for our purposes, and besides we had only a limited time to stay in the mine. As we came up again to daylight, hoisted in the same sort of chairs as those by which we descended, we made a final inspection of the salt which comes from the mine.

"'There are three kinds of salt,' said the guide. 'One that is called green salt contains five or six per cent. of clay, and has no transparency; it is cut into blocks and sent to Russia exactly as it comes from the mine. The second quality is called spiza, and is crystalline and mixed with sand; and the third is in large masses, perfectly transparent, having no earthy matter mingled with it. The salt is found in compact tertiary clays that contain a good many fossils; the finest salt is at the lowest levels, and the poorest at the higher ones.'

"Well, here we are at the top of the shaft, tired and hungry, and excited with the wonderful things we have seen. The visit to the salt-mines of Wieliczka is something to be long remembered."

Since the visit herein described, the manner of working the salt-mines of Wieliczka has undergone a decided change. Owing to the influx of a stream the lower levels of the mines were flooded, and for some time remained full of water. In order to free them it was necessary to introduce powerful pumping machinery of the latest designs, and also to replace the old hoisting apparatus with new. Horse-power was abandoned in favor of steam, both for hoisting and pumping; new precautions were taken against fire; all improved systems of mine-working were tested, and those which proved useful were adopted; and to-day the mines of Wieliczka may be considered, in every respect, the foremost salt-mines in the world.

The sun was setting as our friends reached Cracow, on their return from Wieliczka. The walls of the city were gilded by the rays of light that streamed over the hills which formed the western horizon. In all its features the scene was well calculated to impress the youthful travellers. Frank wished to make a sketch of the gate-way through which they passed on their entrance within the walls, but the hour was late and[Pg 41] delay inadvisable. The commissioner said he would bring them a photograph of the spot, and with this consolation the young man dismissed from his mind the idea of the sketch.

All retired early, as they intended taking the morning train for the Russian frontier, and thence to Warsaw. They were up in good season, and at the appointed time the train carried them out of the ancient capital of Poland.

At Granitsa, the frontier station, they had a halt of nearly two hours. Their passports were carefully examined by the Russian officials, while their trunks underwent a vigorous overhauling. The passports proved to be entirely in order, and there was no trouble with them. The officials were particularly polite to the American trio, and said they were always pleased to welcome Americans to the Empire. They were less courteous to an Englishman who arrived by the same train, and the Doctor said it was evident that the Crimean war had not been entirely forgotten. Several passengers had neglected the precautions which our friends observed at Vienna, in securing the proper indorsement to their passports, and were told that they could not pass the frontier. They were compelled to wait until the passports could be sent to Cracow for approval by the Russian consul at that point, or else to Vienna. A commissioner attached to the railway-station offered to attend to the matter for all who required his aid; formerly it was necessary for the careless traveller to return in person to the point designated, but of late years this has not been required.

"This passport business is an outrageous humbug," said the Englishman with whom our friends had fallen into conversation while they were waiting in the anteroom of the passport office. "Its object is to keep improper persons out of Russia; but it does nothing of the kind. Any Nihilist, Revolutionist, or other objectionable individual can always obtain[Pg 42] a passport under a fictitious name, and secure the necessary approval of consuls or ambassadors. Ivan Carlovitch, for whom the police are on the watch, comes here with a passport in the name of Joseph Cassini, a native of Malta, and subject of Great Britain. His English passport is obtained easily enough by a little false swearing; it is approved by the Russian minister at Vienna, and the fellow enters Russia with perfect ease. The honest traveller who has neglected the formality through ignorance is detained, while the Revolutionist goes on his way contented. The Revolutionist always knows the technicalities of the law, and is careful to observe them; and it is safe to say that the passport system never prevented any political offender from getting into Russia when he wanted to go there.

"I have been in Russia before," he continued, "and know what I am saying. The first time I went there was from Berlin, and on reaching the frontier I was stopped because my passport was not properly indorsed. I supposed I would have to go back to Berlin, but the station-master said I need not take that trouble; I could stop at the hotel, and he would arrange the whole matter, so that I might proceed exactly twenty-four hours later. I did as he told me, and it was all right."

"How was it accomplished?"

"Why, he took my passport and a dozen others whose owners were in the same fix as myself, and sent them by the conductor of the train to Kœnigsburg, where there is a Russian consul. For a fee of two English shillings (fifty cents of your money) the consul approved each passport; another fee of fifty cents paid the conductor for his trouble, and he brought back the passports on his return run to the frontier. Then the station-master wanted four shillings (one dollar) for his share of the work, and we were all en regle to enter the Russian Empire. We got our baggage ready, and were at the station when the train arrived; the station-master delivered our passports, and collected his fee along with the fees of the conductor and consul, and that ended the whole business. The consul knew nothing about any of the persons named in the passports, and we might have been conspirators or anything else that was objectionable, and nobody would have been the wiser. Russia is the only country[Pg 43] in Europe that keeps up the passport system with any severity, and it only results in putting honest people to trouble and expense, and never stops those whom it is intended to reach. There, they've opened the door, and we can now go before the representatives of the autocrat of all the Russias."

One by one they approached the desk, with the result already stated. At the examination of the baggage in the custom-house the clothing and personal effects of our friends were passed without question, but there was some difficulty over a few books which the boys had bought before leaving Vienna. One volume, pronounced objectionable, was seized as contraband, but the others were not taken. Every book written by a foreigner[Pg 44] about Russia is carefully examined by the official censor as soon as it is published, and upon his decision depends the question of its circulation being allowed in the Empire. Anything calculated to throw disrespect upon the Imperial family, or upon the Government in general, is prohibited, as well as everything which can be considered to have a revolutionary tendency.

"They are not so rigid as they used to be," growled the Englishman, as he closed and locked his trunk after the examination was completed. "In the time of the Emperor Nicholas they would not allow anything that indicated there was any other government in the world which amounted to anything, and they were particularly severe upon all kinds of school-books. Now they rarely object to school-books, unless they contain too many teachings of liberty; and they are getting over their squeamishness about criticisms, even if they are abusive and untruthful. The worst case I ever heard of was of an inspector at one of the frontier stations, who seized a book on astronomy because it contained a chapter on 'The Revolutions of the Earth.' He said nothing revolutionary could be allowed to enter the Empire, and confiscated the volume in spite of its owner's explanations.

"Under Nicholas," continued the Englishman, "Macaulay's 'History of England' was prohibited, though it could be bought without much trouble. After Alexander II. ascended the throne the rigors of the censorship were greatly reduced, and papers and books were freely admitted into Russia which were prohibited in France under Louis Napoleon. All the Tauchnitz editions of English works were permitted, even including Carlyle's 'French Revolution.' It is possible that the last-named book had escaped notice, as you would hardly expect it to be allowed free circulation in Russia. Books and newspapers addressed to the professors of the universities, to officers above the rank of colonel, and to the legations of foreign countries are not subjected to the censorship, or at least they were not so examined a few years ago. Since the rise of Nihilism the authorities have become more rigid again, and books and papers are stopped which would not have been suppressed at all before the death of Alexander II.

"If you want to know the exact functions of the censor," said the gentleman, turning to Frank and Fred, "here is an extract from his instructions."

With these words he gave to one of the youths a printed slip which stated that it was the censor's duty to prohibit and suppress "all works written in a spirit hostile to the orthodox Greek Church, or containing[Pg 45] anything that is contrary to the truths of the Christian religion, or subversive of good manners or morality; all publications tending to assail the inviolability of autocratical monarchical power and the fundamental laws of the Empire, or to diminish the respect due to the Imperial family; all productions containing attacks on the honor or reputation of any one, by improper expressions, by the publication of circumstances relating to domestic life, or by calumny of any kind whatever."

The boys thanked the gentleman for the information he had given them on a subject about which they were curious; and as the examination of the custom-house was completed, they proceeded to the restaurant, which was in a large hall at the end of the station.

Near the door of the restaurant was the office of a money-changer, its character being indicated by signs in at least half a dozen languages. Passengers were exchanging their Austrian money for Russian, and the office seemed to be doing an active business.

"That fellow has about as good a trade as one could wish," said the Englishman, as he nodded in the direction of the man at the little window. "Two trains arrive here daily each way; for people going north he changes Austrian into Russian money, and for those going south he[Pg 46] changes Russian into Austrian. He receives one per cent. commission on each transaction, which amounts to four per cent. daily, as he handles the money four times. I have often envied these frontier bankers, who run no risk whatever, provided they are not swindled with counterfeits, and can make twelve hundred per cent. annually on their capital. But perhaps they have to pay so dearly for the privilege that they are unable to get rich by their business. By-the-way," said he, changing the subject abruptly, "did you observe the stout lady that stood near us in the anteroom of the passport office?"

"Yes," answered the Doctor, "and she seemed quite uneasy, as though she feared trouble."

"Doubtless she did," was the reply, "but it was not on account of her passport. She was probably laden with goods which she intended smuggling into Russia, and feared detection. I noticed that she was called aside by the custom-house officials, and ushered into the room devoted to suspected persons. She isn't here yet, and perhaps they'll keep her till the train has gone. Ah! here she comes."

Frank and Fred looked in the direction indicated, but could not see any stout lady; neither could the Doctor, but he thought he recognized a face he had seen before. It belonged to a woman who was comparatively slight in figure, and who took her seat very demurely at one of the tables near the door.

"That is the stout lady of the anteroom," said the Englishman, "and her form has been reduced more rapidly than any advocate of the Banting or any other anti-fat system ever dreamed of. She was probably detected by her uneasy manner, and consequently was subjected to an examination at the hands of the female searchers. They've removed dry goods enough from her to set up a small shop, and she won't undertake smuggling again in a hurry. Import duties are high in Russia, and the temptation to smuggle is great. She was an inexperienced smuggler, or she would[Pg 47] not have been caught so easily. Probably she is of some other nationality than Russian, or they would not have liberated her after confiscating her contraband goods."

The incident led to a conversation upon the Russian tariff system, which is based upon the most emphatic ideas in favor of protection to home industries. As it is no part of our intention to discuss the tariff in this volume, we will omit what was said upon the subject, particularly as no notes were taken by either Frank or Fred.

In due time the train on the Russian side of the station was ready to receive the travellers, and they took their places in one of the carriages. It needed only a glance to show they had crossed the frontier. The Austrian uniform disappeared, and the Russian took its place; the Russian language was spoken instead of German; the carriages were lettered in Russian; posts painted in alternate stripes of white and black (the invention of the Emperor Paul about the beginning of the present century), denoted the sovereignty of the Czar; and the dress of many of the passengers indicated a change of nationality.

The train rolled away from Granitsa in the direction of Warsaw, which was the next point of destination of our friends. The country through which they travelled was not particularly interesting; it was fairly though not thickly settled, and contained no important towns on the line of the railway, or any other object of especial interest. Their English acquaintance said there were mines of coal, iron, and zinc in the neighborhood of Zombkowitse, where the railway from Austria unites with that from eastern Germany. It is about one hundred and eighty miles from Warsaw; about forty miles farther on there was a town with an unpronounceable name, with about ten thousand inhabitants, and a convent, which is an object of pilgrimage to many pious Catholics of Poland and Silesia. A hundred miles from Warsaw they[Pg 48] passed Petrikau, which was the seat of the ancient tribunals of Poland; and then, if the truth must be told, they slept for the greater part of the way till the train stopped at the station in the Praga suburb of Warsaw, on the opposite bank of the Vistula.

As they neared the station they had a good view of Warsaw, on the heights above the river, and commanded by a fortress which occupies the centre of the city itself. Alighting from the train, they surrendered their passports to an official, who said the documents would be returned to them at the Hôtel de l'Europe, where they proposed to stop during their sojourn within the gates of Warsaw. Tickets permitting them to go into the city were given in exchange for the passports, and then they entered a rickety omnibus and were driven to the hotel.

It was late in the afternoon when they climbed the sloping road leading into Warsaw, and looked down upon the Vistula and the stretch of low land on the Praga side. Fred repeated the lines of the old verse from which we have already quoted, and observed how well the scene is described in a single couplet:

"Warsaw's last champion from her heights surveyed,

Wide o'er the fields a waste of ruin laid."

Laid desolate by many wars and subjected to despotic rule, the country around Warsaw bears little evidence of prosperity. Many houses are[Pg 49] without tenants, and many farms are either half tilled or wholly without cultivation. The spirit of revolution springs eternal in the Polish breast, and the spirit of suppression must be equally enduring in the breast of the Russian. It is only by the severest measures that the Russians can maintain their control of Poland. A Polish writer has well described the situation when he says, "Under a cruel government, it is Poland's duty to rebel against oppression; under a liberal government, it is her duty to rebel because she has the opportunity."

After dinner at the hotel our friends started for a walk through the principal streets; but they did not go very far. The streets were poorly lighted, few people were about, and altogether the stroll was not particularly interesting. They returned to the hotel, and devoted an hour or so to a chat about Poland and her sad history.

"Walls are said to have ears," the Doctor remarked, "but we have little cause to be disturbed about them, as we are only discussing among ourselves the known facts of history. Poland and Russia were at war for centuries, and at one time Poland had the best of the fight. How many of those who sympathize so deeply with the wrongs of Poland are aware of the fact that in 1610 the Poles held Moscow as the Russians now hold Warsaw, and that the Russian Czar was taken prisoner, and died the next year in a Polish prison? Moscow was burned by the Poles in 1611, and thousands of its inhabitants were slaughtered; in 1612 the Poles were[Pg 50] driven out, and from that time to the present their wars with Russia have not been successful."

"I didn't know that," said Frank, "until I read it to-day in one of our books."

"Nor did I," echoed Fred; "and probably not one person in a hundred is aware of it."

"Understand," said the Doctor, with emphasis—"understand that I do not say this to justify in any way the wrongs that Russia may have visited on Poland, but simply to show that all the wrong has not been on one side. Russia and Poland have been hostile to each other for centuries; they are antagonistic in everything—language, religion, customs, and national ambitions—and there could be no permanent peace between[Pg 51] them until one had completely absorbed the other. Twice in this century (in 1830 and 1863) the Poles have rebelled against Russia, because they had the opportunity in consequence of the leniency of the Government. From present appearances they are not likely to have the opportunity again for a long time, if ever."

One of the youths asked how the revolution of 1830 was brought about.

"Poland had been, as you know, divided at three different times, by Russia, Austria, and Prussia," said the Doctor, "the third partition taking place in 1795. At the great settlement among the Powers of Europe, in 1815, after the end of the Napoleonic wars, the Emperor of Russia proposed to form ancient Poland into a constitutional monarchy under the Russian crown. His plan was adopted, with some modifications, and from 1815 to 1830 the country had its national Diet or Parliament, its national administration, and its national army of thirty thousand men. The Russian Emperor was the King of Poland, and this the Poles resented; they rebelled, and were defeated. After the defeat the constitution was withdrawn and the national army abolished; the Polish universities were[Pg 52] closed, the Polish language was proscribed in the public offices, and every attempt was made to Russianize the country. It was harshly punished for its rebellion until Alexander II. ascended the throne.

"Alexander tried to conciliate the people by granting concessions. The schools and universities were reopened; the language was restored; Poles were appointed to nearly all official positions; elective district and municipal councils were formed, and also a Polish Council of State. But nothing short of independence would satisfy the inhabitants, and then came the revolution of 1863. It was suppressed, like its predecessor, and from that time the Russians have maintained such an iron rule in Poland that a revolt of any importance is next to impossible. All the oppression of which Russia is capable cannot destroy the spirit of independence among the Poles. They are as patriotic as the Irish, and will continue to hope for liberty as long as their blood flows in human veins."

A knock on the door brought the Doctor's discourse to an abrupt end. It was made by the commissioner, who came to arrange for their excursion on the following day.

We will see in due course where they went and what they saw. It is now their bedtime, and they are retiring for the night.

The next morning they secured a carriage, and drove through the principal streets and squares, visiting the Royal Palace and other buildings of importance, and also the parks and gardens outside the city limits. Concerning their excursion in Warsaw the youths made the following notes:

"We went first to the Royal Castle, which we were not permitted to enter, as it is occupied by the Viceroy of Poland, or 'the Emperor's Lieutenant,' as he is more commonly called. It is a very old building, which has been several times altered and restored. There were many pictures and other objects of art in the castle until 1831, when they were removed to St. Petersburg. In the square in front of the castle is a statue of one of the kings of Poland, and we were told that the square was the scene of some of the uprisings of the Poles against their Russian masters.

"From the castle we went to the cathedral, which was built in the thirteenth century, and contains monuments to the memory of several of the kings and other great men of the country. It is proper to say here[Pg 53] that the Catholic is the prevailing religion of Poland, and no doubt much of the hatred of Russians and Poles for each other is in consequence of their religious differences. By the latest figures of the population that we have at hand, Russian Poland contains about 3,800,000 Catholics, 300,000 Protestants, 700,000 Jews, and 250,000 members of the Greek Church and adherents of other religions, or a little more than 5,000,000 of inhabitants in all. Like all people who have been oppressed, the Catholics and Jews are exceedingly devout, and adhere unflinchingly to their religious faith. Churches and synagogues are numerous in Warsaw, as in the other Polish cities. In our ride through Warsaw we passed many[Pg 54] shrines, and at nearly all of them the faithful were kneeling to repeat the prayers prescribed by their religious teachers.

"From the cathedral we went to the citadel, which is on a hill in the centre of the city, and was built after the revolution of 1830. The expense of its construction was placed upon the people as a punishment for the revolution, and for the purpose of bombarding the city in case of another rebellion. From the walls of the citadel there is a fine view of considerable extent; but there is nothing in the place of special interest. The fort is constantly occupied by a garrison of Russian soldiers. It contains a prison for political offenders and a military court-house, where they are tried for their alleged offences.

"There are ten or twelve squares, or open places, in Warsaw, of which the finest is said to be the Saxon Square. It contains a handsome monument to the Poles who adhered to the Russian cause in the revolution of 1830. Some writers say it was all a mistake, and that the Poles whose memory is here preserved were really on their way to join the regiments which had declared in favor of the insurrection.

"There are several handsome streets and avenues; and as for the public palaces and fine residences which once belonged to noble families of Poland, but are now mostly in Government hands, the list alone would be long and tedious. One of the finest palaces is in the Lazienki Park, and was built by King Stanislaus Poniatowski. It is the residence of the Emperor of Russia when he comes to Warsaw; but as his visits are rare, it is almost always accessible to travellers. We stopped a few minutes in front of the statue of King John Sobieski. There is an anecdote about this statue which the students of Russian and Polish history will appreciate. During a visit in 1850 the Emperor Nicholas paused in front of the statue, and remarked to those around him, 'The two kings of Poland who committed the greatest errors were John Sobieski and myself, for we both saved the Austrian monarchy.'

"Inside the palace there are many fine paintings and other works of art. There are portraits of Polish kings and queens, and other rare pictures, but not as many as in the Castle of Villanov, which we afterwards visited. In the latter, which was the residence of John Sobieski, and now belongs to Count Potocki, there are paintings by Rubens and other celebrated masters, and there is a fine collection of armor, including the suit which was presented to Sobieski by the Pope, after the former had driven the Turks away from Vienna. It is beautifully inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl, and covered with arabesques of astonishing delicacy. We could have spent hours in studying it, and you may be sure we left it with great reluctance.

"Warsaw has a population of nearly three hundred thousand, and there are a good many factories for the manufacture of carriages, pianos, cloth, carpets, and machines of various kinds. The city is the centre of a[Pg 56] large trade in grain, cattle, horses, and wool, and altogether it may be considered prosperous. Much of the business is in the hands of the Jews, who have managed to have and hold a great deal of wealth in spite of the oppression they have undergone by both Poles and Russians.

"The women of Warsaw are famous for their beauty, and we are all agreed that we have seen more pretty faces here than in any other city of Europe in the same time. The Jews of Warsaw are nearly all blonds; the men have red beards, and the hair of the women is of the shade that used to be the fashion among American and English actresses, and is not yet entirely forgotten. We bought some photographs in one of the shops, and are sure they will be excellent adornments for our albums at home.

"In the evening we went to the opera in the hope of seeing the national costumes of the Poles, but in this we were disappointed. The operas are sung in Italian; the principal singers are French, Italian, English, or any other nationality, like those of opera companies elsewhere, and only the members of the chorus and ballet are Poles. Russian uniforms are in the boxes and elsewhere in the house, and every officer is required to wear his sword, and be ready at any moment to be summoned to fight. The men not in uniform are in evening dress, and the ladies are like those[Pg 57] of an audience in Vienna or Naples, so far as their dress is concerned. The opera closed at half-past eleven; our guide met us outside the door, and when we proposed a stroll he said we must be at the hotel by midnight, under penalty of being arrested. Any one out-of-doors between midnight and daylight will be taken in by the police and locked up, unless he has a pass from the authorities. In troubled times the city is declared in a state of siege, and then everybody on the streets after dusk must carry a lantern.

"As we had no fancy for passing the night in a Russian station-house, we returned straight to the hotel. Probably we would have been there by midnight in any event, as we were tired enough to make a long walk objectionable."

The next day our friends visited some of the battle-fields near Warsaw, and on the third took the train for St. Petersburg, six hundred and twenty-five miles away. There was little of interest along the line of railway, as the country is almost entirely a plain, and one mile is so much like another that the difference is scarcely perceptible. The principal towns or cities through which they passed were Bialystok and Grodno, the latter famous for having been the residence of several Polish kings, and containing the royal castle where they lived. At Wilna, four hundred and forty-one miles from St. Petersburg, the railway unites with that from Berlin. The change of train and transfer of baggage detained the party half an hour or more, but not long enough to allow them to inspect this ancient capital of the independent duchy of Lithuania. At Pskof they had another halt, but only sufficient for patronizing the restaurant. The town is two miles from the station, and contains an old castle and several other buildings of note; it has a prominent place in Poland's war history, but is not often visited by travellers.

At Gatchina, famous for its trout and containing an Imperial palace, an official collected the passports of the travellers, which were afterwards returned to them on arriving at the St. Petersburg station. As they approached the Imperial city the first object to catch the eye was a great ball of gold outlined against the sky. Frank said it must be the dome of St. Isaac's Church, and the Doctor nodded assent to the suggestion. The dome of St. Isaac's is to the capital of Russia what the dome of St. Peter's is to Rome—the first object on which the gaze of the approaching traveller is fixed.