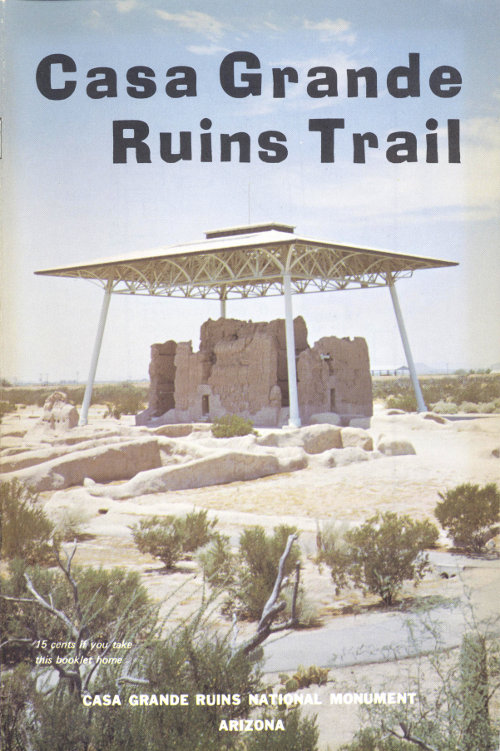

15 cents if you take this booklet home

CASA GRANDE RUINS NATIONAL MONUMENT

ARIZONA

SAFETY

You are in a desert area. Sometimes the desert can be harsh. Cactus spines can hurt. Intense heat can cause varying degrees of discomfort. Poisonous animals, though rare, are here. Know your own limitations, and exercise caution.

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, one of more than 280 areas administered by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, was set aside because of its outstanding archeological values. This area belongs to you and is part of your heritage as an American citizen. The men and women in the uniform of the National Park Service are here to assist you and will welcome the opportunity to make your visit to Casa Grande Ruins more enjoyable.

The National Park Service was created in 1916 to preserve the National Parks and Monuments for your enjoyment and that of future generations. Federal law prohibits activities which would destroy any of the works of nature or man that are preserved here. These include such activities as hunting, woodcutting, collecting—even taking of small pieces such as broken pottery. Please help preserve Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, and remember: A thoughtless act on your part can destroy in a few moments something that has been here for centuries. Please stay on the designated trail.

DON’T FORGET YOUR CAMERA

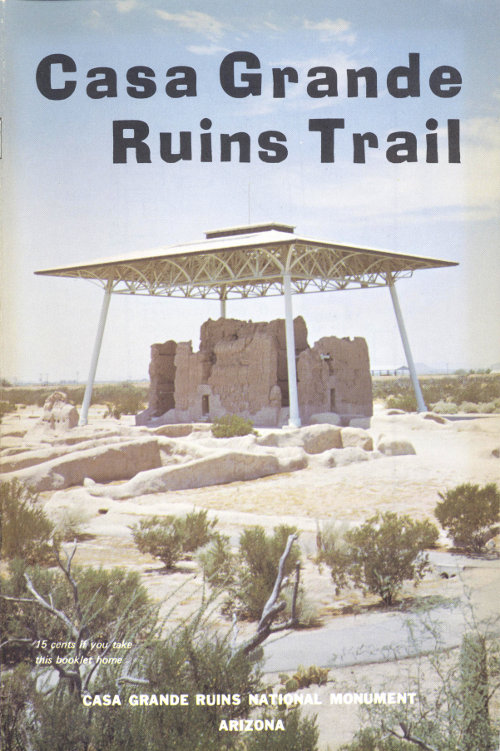

The Casa Grande Trail is about 400 yards long and an easy walk. Numbered stakes along the trail are set at points of interest, and corresponding numbered paragraphs in this booklet explain the features.

You may enter the Casa Grande (Big House) only on a ranger-conducted guided tour.

From about 2,000 years ago until about A.D. 1450, people living in this area developed and expanded a stone-age civilization that the archeologists call the Hohokam (Ho-Ho-Kahm) culture. Hohokam means “those who have 2 gone” in the language of the nearby Pima Indians, who are probably descendants of these prehistoric people.

The Hohokam lived in this region for many centuries before building walled villages like this between A.D. 1300 and 1450. Primarily farmers, raising corn, beans, squash, and cotton, they developed extensive irrigation canal systems that took water from the Gila (Hee-la) River. About A.D. 1450, this village and others like it were abandoned. We do not know why. When the Spaniards explored this area, they found Pimas, living in open villages and irrigating their farmlands, several miles to the west.

The wall around this village originally stood 7 to 11 feet high. There were no doorways in it. This wall and building of this village are of caliche, a limy subsoil found 2 to 5 feet below the surface of this region. To get in or out of the village the Indians used ladders to climb over the wall. The foundations, all that remain of the wall, are covered with wire reinforced, tinted-cement stucco to protect them. Stepping or sitting on the walls may damage them. Help us to protect the walls.

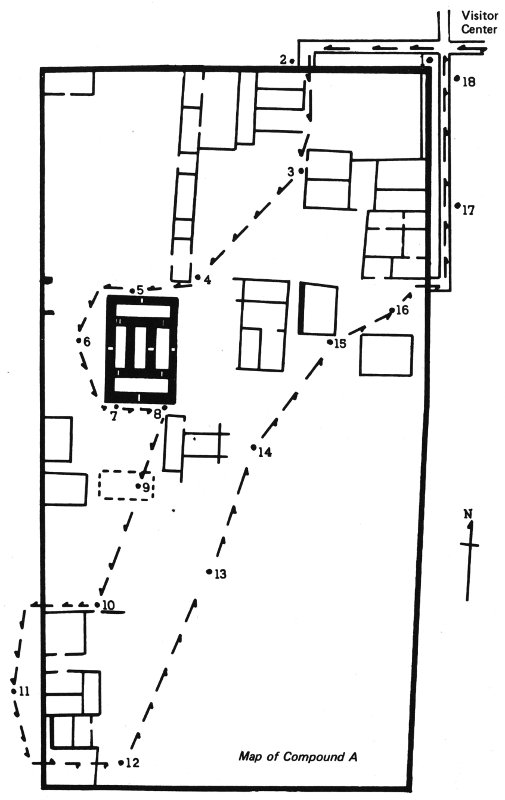

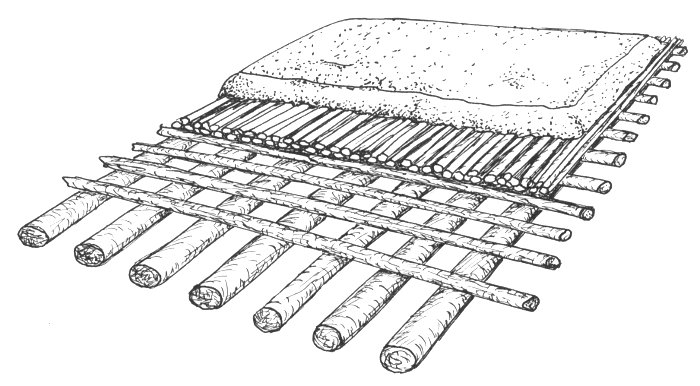

This room is one of approximately 60 rooms inside the compound wall. Walls and floors were made of caliche, and ceilings were layers of poles, saguaro ribs, and reeds capped with a covering of caliche. Some rooms, like this one, had doorways; other rooms had hatchways in the roof centers. A small clay fire pit, about 1 foot in diameter, was in the center of each room. During hot weather, cooking was done out of doors. (See next page).

The Casa Grande was first seen by a European on November 27, 1694, when Father Kino, a Jesuit missionary and explorer, visited the area. He called the building the Casa Grande, or Big House, because it was the biggest structure he had seen in southern Arizona.

The large steel canopy was erected in 1932 to protect the Casa Grande from rain. This building has not been restored, 3 but to keep it from crumbling further, the ruin was stabilized in 1891. The undercut base of the ruin was filled with bricks and cement, two-by-fours were placed over the doorways, and two steel rods were inserted to brace the south wall.

Living Room

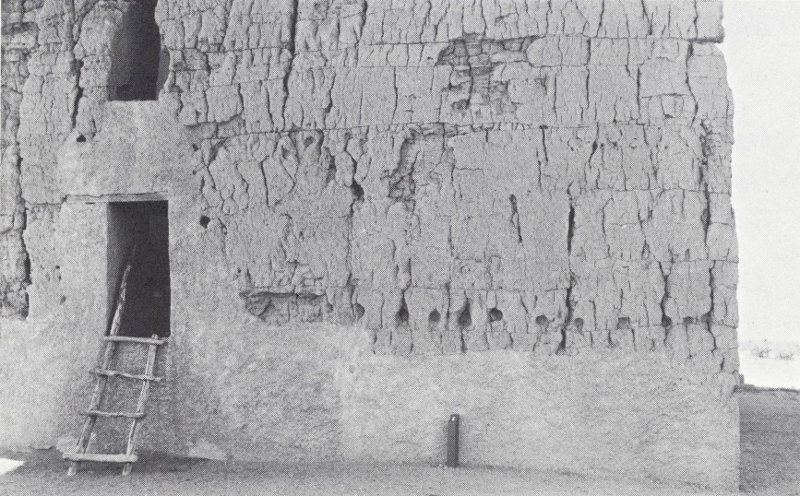

The Casa Grande, Northeast Corner

The wood over the doorway is not original. There is no original wood remaining in the Casa Grande. Father Kino reported it as burned out prior to his 1694 visit.

Though four stories high, only the upper three stories of the Casa Grande were used. The five ground-story rooms were filled with earth to form a platform foundation, and a ladder was used to gain access to the second story through the doorway seen here.

To the right of the doorway and about shoulder high are a line of holes in the wall. These show where a roof, probably for shade, was socketed into the wall.

Notice the series of horizontal cracks along the west wall of the Casa Grande. The cracks show that the walls were built with layers of caliche mud. Each layer was about 26 inches thick. Bricks were not used. The Indians did not make adobe bricks until taught by the Spanish priests centuries later.

Above the enlarged open doorway is a blocked one. The upper doorway was sealed by the Indians, but they left a small opening for ventilation at the bottom of the block. The large hole above the blocked doorway is where the original wooden lintel poles rotted away, causing part of the wall to fall.

Both to left and right of the blocked doorway are small windows in the north and south rooms. The left window is round and the right window is square.

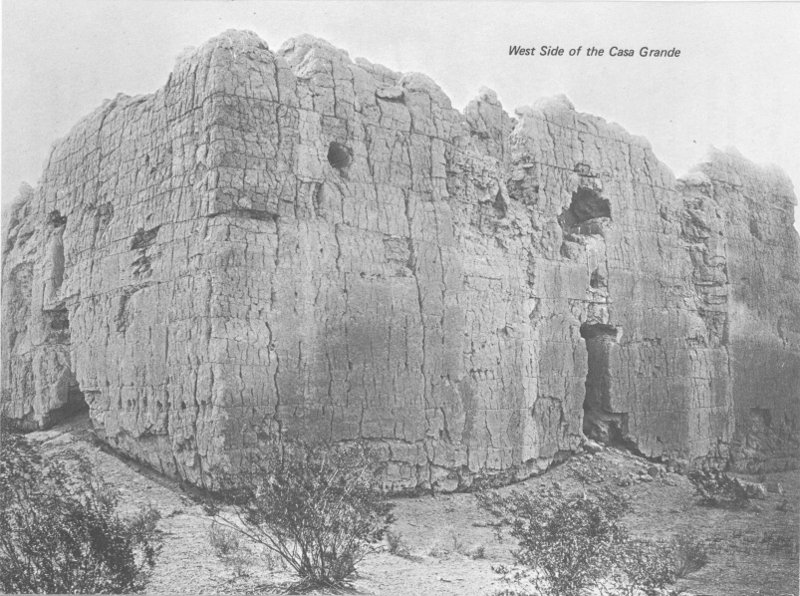

In the 1880’s, Ed Schieffelin, the founder of Tombstone, Arizona, took this photograph of the Casa Grande. The structure has deteriorated little since then.

Here are two more blocked doorways that originally led into the west second and third-story rooms. Doorways made by these Indians are smaller than modern entryways, but this does not mean that the people were small. During bad weather these openings could have been closed off with mats and skins, and the smaller the doorway, the easier it was to block. Moreover, it let in less cold air.

West Side of the Casa Grande

The round holes in a line between the doorways were beam sockets. Poles of pinyon pine and/or juniper formed the ceilings and spanned the width of the room.

Cross-section Drawing of a Roof.

The interior plaster of the west wall was made from caliche, ground fine in a stone mortar and with the gravel sifted out. This plaster is more than 650 years old.

Names cut into the plaster date from the last half of the last century, and were cut into the plaster before the ruin was protected by the Federal government. Because of these names, and the fact that the interior of the Casa Grande may easily be vandalized, visitors are permitted to enter the ruin only on ranger-conducted guided tours.

The walls of the Casa Grande are heavy and massive, ranging in thickness from 4½ to 1¾ feet. To save work and to reduce weight on the foundation, the Indians narrowed the walls as they built them up. 7 The outside surface bows inward as the wall rises. The inside surface, however, is nearly vertical. (See photo).

Southeast Corner of the Casa Grande

If you look closely at the surface of the ground you can see the tops of the walls of some rooms. These rooms are unexcavated. Probably the floor of this room is less than one foot below ground surface, and only the foundations of the walls remain.

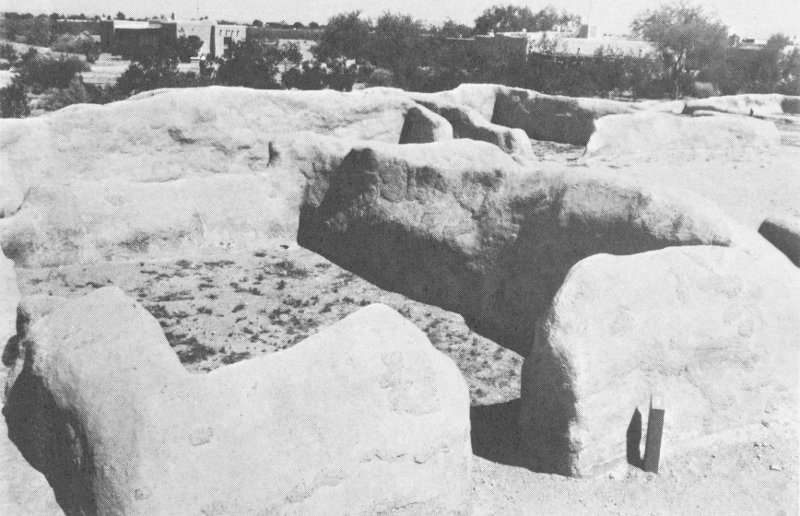

The high walls shown at top of the next page are all that remain of a three-story building that stood in this southwest corner of the walled village. These rooms apparently were living rooms where several families slept, worked, and stored their food, tools, and clothing. One of the large red Hohokam jars in the Visitor Center exhibit room was recovered near here.

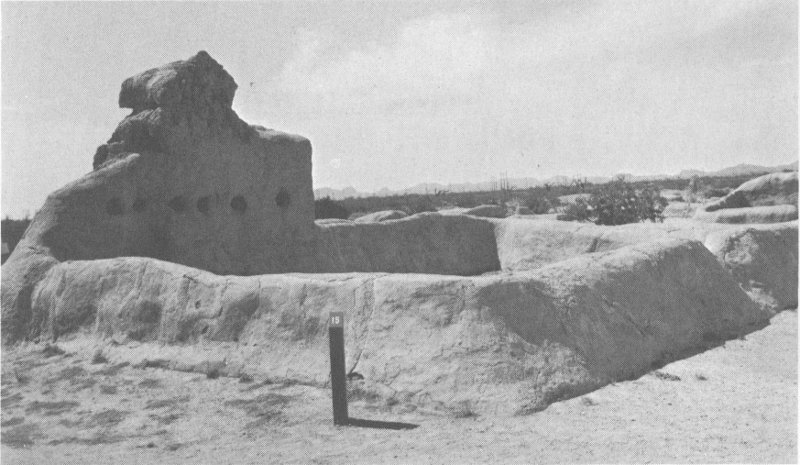

This is another part of the village wall. To save labor, the west side of the three-story building was built against the wall. During the winter of 1906-07, Dr. J. W. Fewkes conducted 8 excavations in this ruin for the Smithsonian Institution. He found debris along the outside of the wall indicating that it once stood 7 to 11 feet high. (Bottom, left).

Southwest Building

Outer Wall

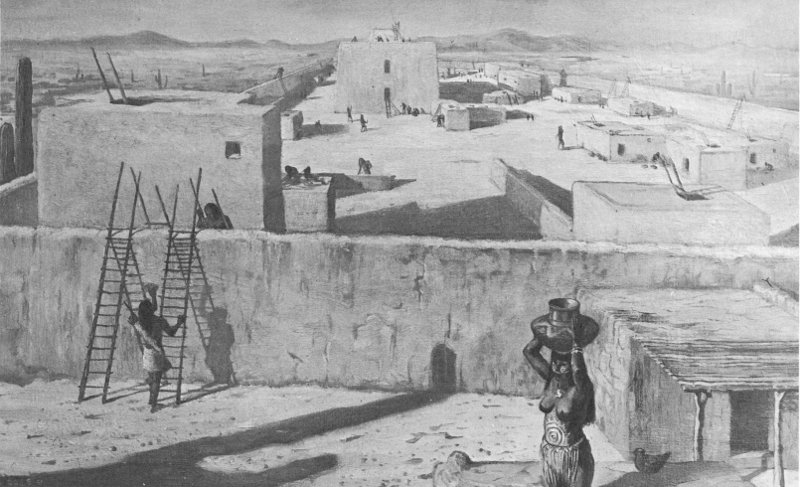

From this vantage point you can view the whole compound. The walls enclosed an area of 2⅛ acres. Most of the dwellings in the village were one story high.

In 1951, Paul Coze, an Arizona artist, painted a restoration of the Ruin. This painting, on page 10, may help you visualize what the village looked like 650 years ago. The high standing walls to your left are remains of the tall building in the lower left-hand corner of the painting.

The prehistoric Indian canal used to irrigate farmlands in this area lay north of the Monument but curved to the south and passed near the farm shed visible one-half mile to the west. The high bank to the south and west is the line of the modern canal. The Indians cultivated the land to the west beyond the modern canal, walking from one-half to one mile to reach their fields.

The vacant area to your right once had houses on it, but they were of rather flimsy upright-pole-and-mud construction and little remains of them but floors and wall post holes. The open places in the village were used for children’s play, work areas, outdoor cooking, and other purposes.

Again we come back to the Casa Grande. This is a unique structure in this region and its major purpose or function is not known. It does not have the appearance of a normal dwelling. Theories that the structure might have been a fort-like watchtower fail to explain what people the Casa Grande folk might have been watching. (There is no real evidence of warfare or strife.) Recent investigations have suggested that certain openings in the upper walls may have been utilized for astronomical observations, but whether the entire structure was built for this purpose is mere speculation.

Take nothing but pictures—

Leave nothing but footprints

This building stood two stories high. Socket holes for the first-story ceiling can still be seen on the east side of the high wall. The room is called Font’s Room for Father Font, a Spanish Franciscan priest who visited here in 1775.

Paul Coze Painting. Restoration of the Casa Grande

The Casa Grande

Font’s Room

Look over the village wall and to the east, between the residences and the Visitor Center. About 150 feet away is the low mound that was one of the trash dumps for this village. This is where the Hohokam for over a century threw their broken pottery, tools, shell jewelry, garbage, and other refuse. From this mound came much of our information about the material remains of these ancient people. In order to protect archeological values, visitors are not allowed on the mound.

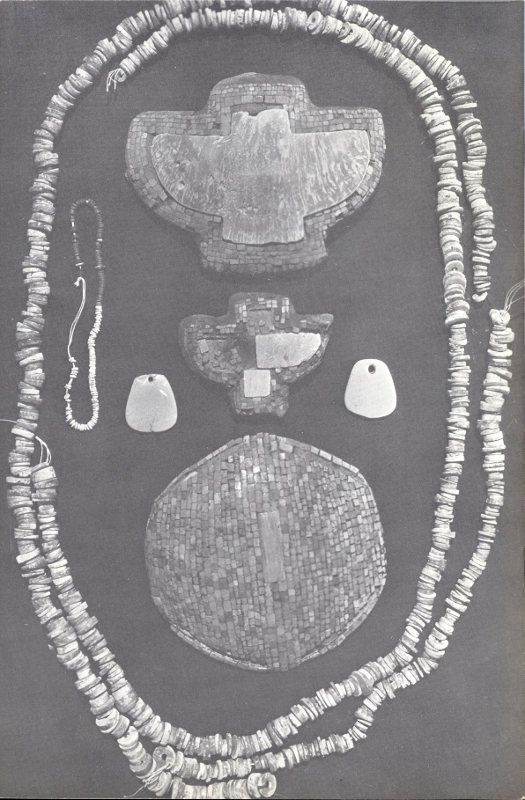

The turquoise and shell mosaic emblems in the Visitor Center jewelry exhibit were found in 1926 in the west end of this room during excavations to stabilize the walls. They are exceptionally fine examples of prehistoric mosaic handicraft. (See photo on back cover).

To return to the Visitor Center take the path to the right.

We hope you have enjoyed your trip along the Casa Grande trail. The National Park Service rangers are here to 13 assist you in any way they can and will do their best to answer your questions.

America’s growing need for outdoor recreation areas was recognized by Congress with the passage of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965. This law authorizes entrance and users’ fees at Federal Recreation Areas and dedicates the money from those fees, plus revenue from the sale of surplus Federal real estate and the Federal tax on fuel used in pleasure boats, to the purchase and development of public recreation lands and waters.

Roughly 40 percent of your entrance fee goes to buy additional Federal Recreation Areas—a share in the California Redwoods, a bit of Fire Island, a view from Spruce Knob, a safe haven for the vanishing whooping crane, or the purchase of Hubbell Trading Post in northeastern Arizona. The other 60 percent goes to the states and through them to towns and counties to buy and develop “near to home” recreation areas such as Picacho State Park, Arizona. These grants are matched with an equal amount from state and local sources.

The $10 annual permit which is valid for some 7,000 Federal areas administered by the National Park Service, Forest Service, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, Tennessee Valley Authority and Corps of Engineers may be purchased at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. For additional information about the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 ask a ranger.

This booklet is published in cooperation with the National Park Service by the

Southwest Parks and Monuments Association

A non-profit publishing and distributing organization supporting historical, scientific and educational activities of the National Park Service.

5th Ed. 1-73-20M

Turquoise and shell mosaic emblems