This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Mexico and Her People of To-day

An Account of the Customs, Characteristics, Amusements, History and Advancement of the Mexicans, and the Development and Resources of Their Country

Author: Nevin O. (Nevin Otto) Winter

Release Date: August 21, 2019 [eBook #60135]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MEXICO AND HER PEOPLE OF TO-DAY***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/mexicoherpeopleo02wint |

MEXICO AND HER PEOPLE OF TO-DAY

Uniform with This Volume

| Panama and the Canal | $3.00 |

| By Forbes Lindsay | |

| Cuba and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Forbes Lindsay | |

| Brazil and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Guatemala and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Mexico and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Argentina and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Bohemia and the Čechs | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| In Viking Land. Norway: Its Peoples, Its Fjords and Its Fjelds | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| Turkey and the Turks | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| Sicily, the Garden of the Mediterranean | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| In Wildest Africa | 3.00 |

| By Peter MacQueen |

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

53 Beacon Street, Boston, Mass.

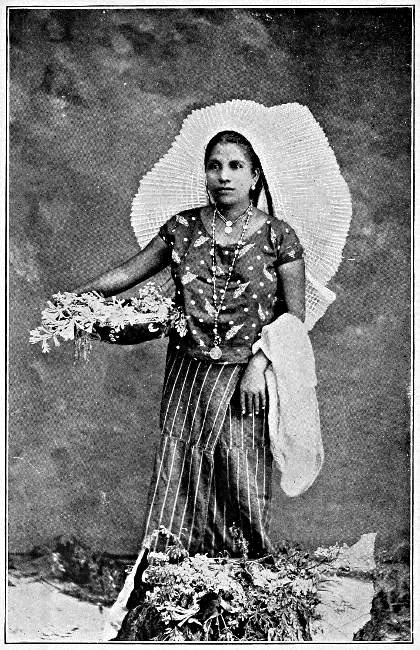

A BELLE OF TEHUANTEPEC (See page 180)

MEXICO AND

HER PEOPLE

OF TO-DAY

AN ACCOUNT OF THE

CUSTOMS, CHARACTERISTICS, AMUSEMENTS,

HISTORY AND ADVANCEMENT

OF THE MEXICANS, AND THE DEVELOPMENT

AND RESOURCES OF THEIR

COUNTRY

BY

NEVIN O. WINTER

ILLUSTRATED FROM ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS

BY THE

AUTHOR and C. R. BIRT

New Revised Edition

BOSTON

L. C. PAGE AND COMPANY

MDCCCCXII

Copyright, 1907,

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

Copyright, 1912,

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

All rights reserved

Second Impression, May, 1908

Third Impression, June, 1910

New Revised Edition, January, 1912

Electrotyped and Printed by

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

TO

My Mother

AND THE MEMORY OF

My Father

Since the first publication of “Mexico and Her People of To-day,” Mexico has seen stirring times, and there has been a radical change in the government. Revolution again broke forth, and the long dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz has ended. These conditions have made advisable a completely revised edition of this work, which the public and the press have stamped with their approval to a degree that has been most pleasing. To both public and press the author desires to return his most sincere thanks, and he has in this revision endeavoured to be as accurate and painstaking as in the original preparation. Furthermore, another trip to that most interesting country has enabled the author to give a description of a section but briefly treated in the previous edition. New appendices have been added, consisting of a bibliography and a few suggestions for those contemplating a trip to Mexico.

Nevin O. Winter.

Toledo, Ohio, January, 1912.

Many books have been written about Mexico, but several of the best works were written a quarter of a century ago and are now out of print. This fact and the developments of the past few years leads the author to believe that there is a field for another book on that most interesting country; a book that should present in readable form reliable information concerning the customs and characteristics of the people of Mexico, as well as the great natural resources of the country and their present state of development, or lack of development.

It has been the aim of the author to make a complete and accurate presentation of the subject rather than to advance radical views concerning and harsh criticism of our next-door neighbours. With this idea in mind he has read nearly every prominent work on Mexico and Mexican history, as well as other current periodical literature concerning that country[vi] during the two years devoted to the preparation of this volume. It is hoped that the wide range of subjects, covering the customs, habits, amusements, history, antiquities, and resources will render the volume of value to any one interested in Mexico and her progress.

If this volume shall aid in any way to a better understanding of Mexico by Americans, or in furthering the present progressive movement in that country, then the author will feel amply repaid for the months of labour devoted to its preparation.

The author wishes to make special acknowledgment of obligation to his friend Mr. C. R. Birt, his companion during the greater part of his travels through Mexico, and to whose artistic sense in selection and grouping the excellence of many of the photographs herewith reproduced is due.

Toledo, Ohio, September, 1907.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Aztec Land | 1 |

| II. | Across the Plateaus | 22 |

| III. | The Capital | 46 |

| IV. | The Valley of Anahuac | 74 |

| V. | The Tropics | 90 |

| VI. | A Glimpse of the Oriental in the Occident | 111 |

| VII. | The Isthmus of Tehuantepec | 128 |

| VIII. | In the Footsteps of the Ancients | 144 |

| IX. | Woman and Her Sphere | 162 |

| X. | The Peon | 183 |

| XI. | Customs and Characteristics | 201 |

| XII. | Holidays and Holy-days | 225 |

| XIII. | A Transplanted Sport | 243 |

| XIV. | Education and the Arts | 257 |

| XV. | Mines and Mining | 274 |

| XVI. | Railways and Their Influence | 290 |

| XVII. | Religious Forces | 308 |

| XVIII. | Passing of the Lawless | 328 |

| XIX. | The Story of the Republic | 343 |

| XX. | The Guiding Hand | 369 |

| XXI. | The Revolution of 1910 | 396 |

| XXII. | The Sierras and Beyond | 415 |

| XXIII. | The Ruined Cities of Yucatan | 438 |

| XXIV. | The Present and the Future | 456 |

| Appendices | 479 | |

| Index | 485 |

| PAGE | |

| A Belle of Tehuantepec (See page 180) | Frontispiece |

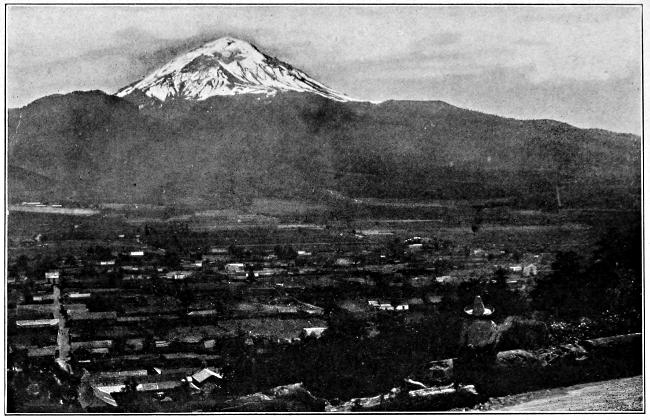

| Snow-capped Popocatapetl | 4 |

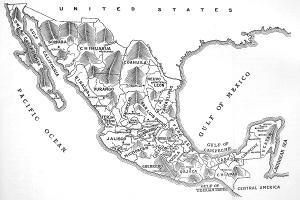

| General Map of Mexico | 6 |

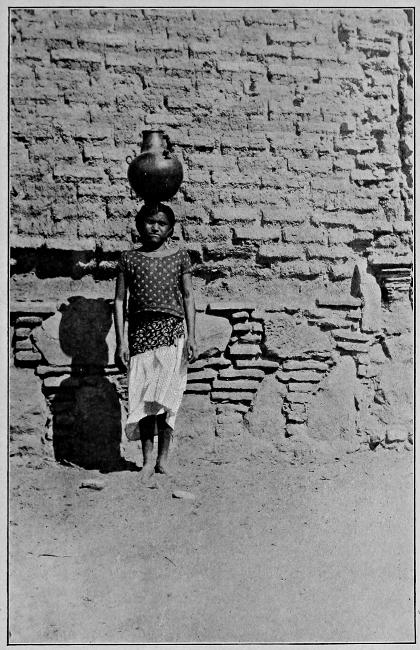

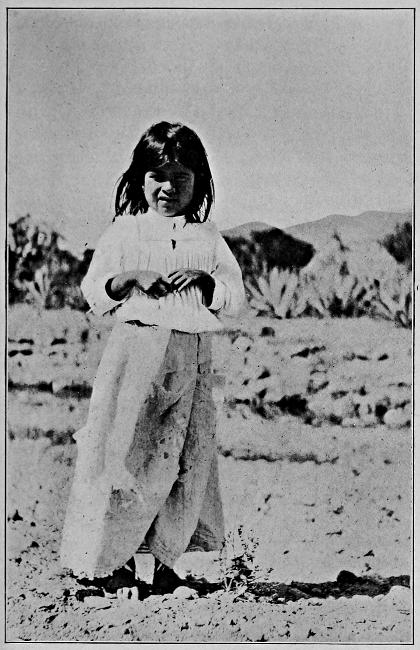

| An Indian Maiden | 10 |

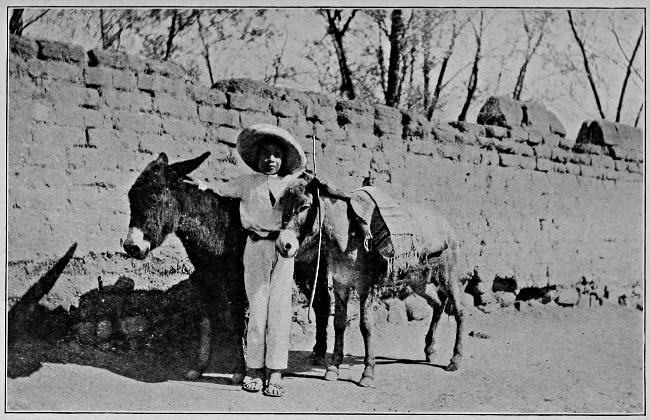

| “The Land of Burros and Sombreros” | 22 |

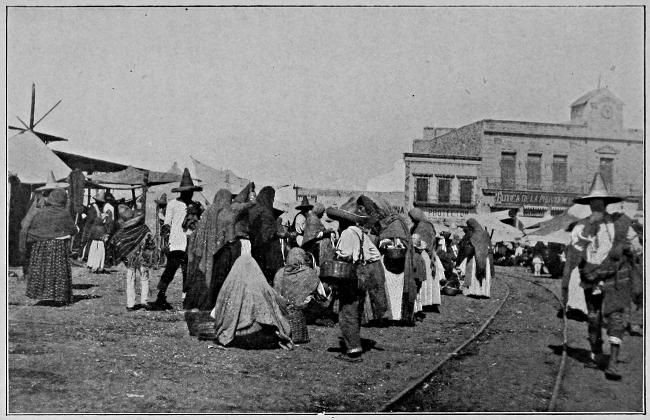

| Market Scene in San Luis Potosi | 30 |

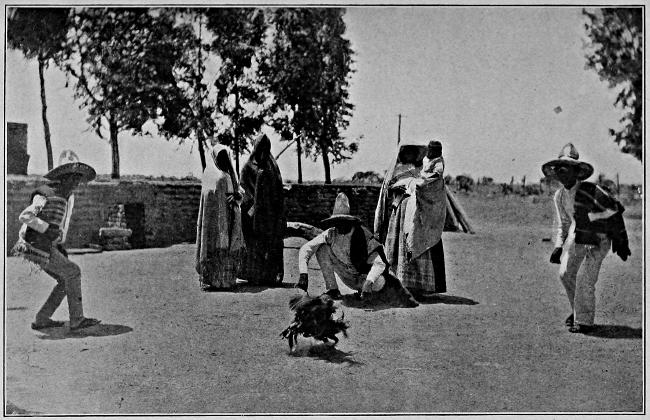

| Cock-fighting in Mexico | 33 |

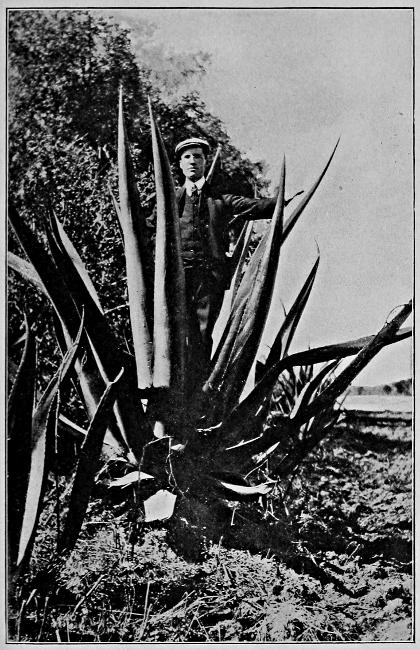

| The Maguey | 41 |

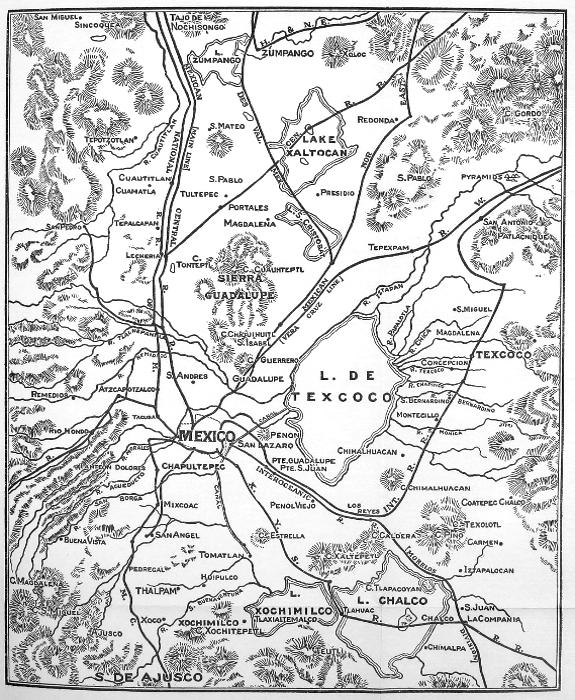

| Map of the Valley of Mexico | 46 |

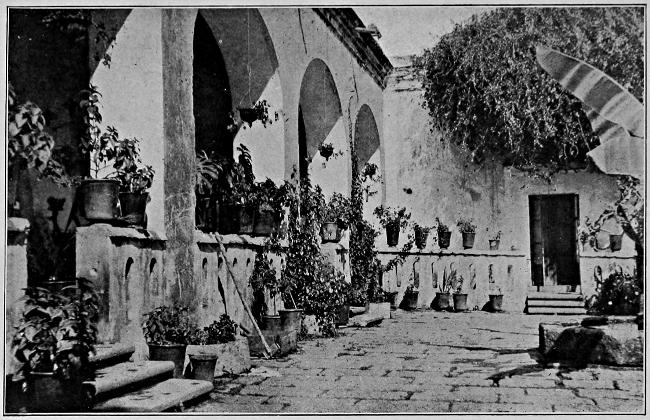

| The Patio of an Old Residence | 48 |

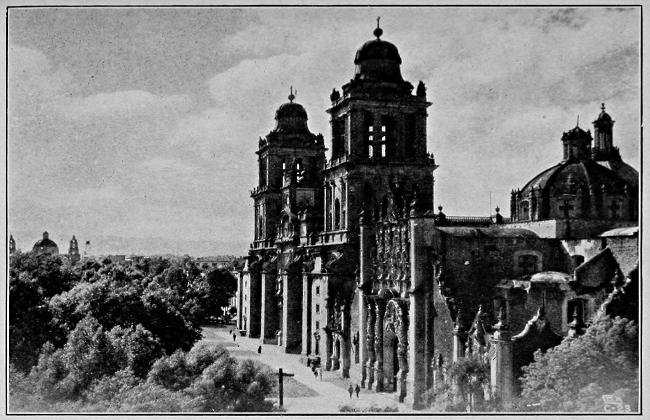

| The Cathedral | 60 |

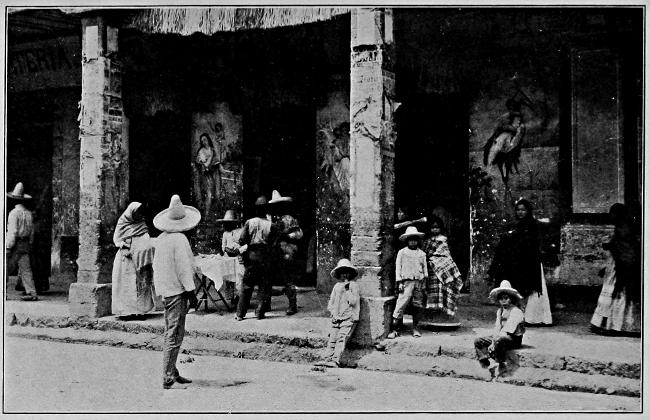

| A Picturesque Pulque Shop | 66 |

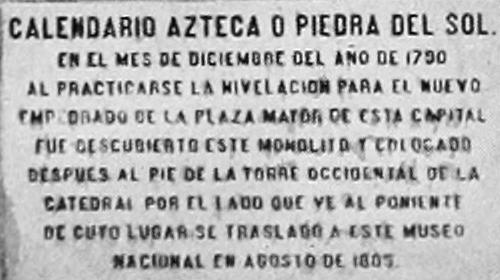

| The Calendar Stone | 77 |

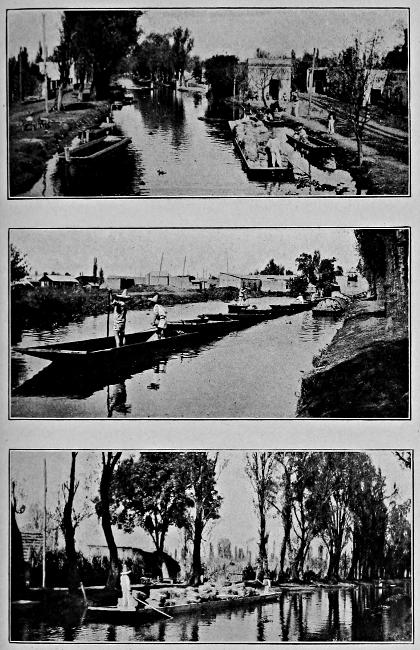

| Scenes on the Viga Canal | 82 |

| Castle of Chapultepec | 86 |

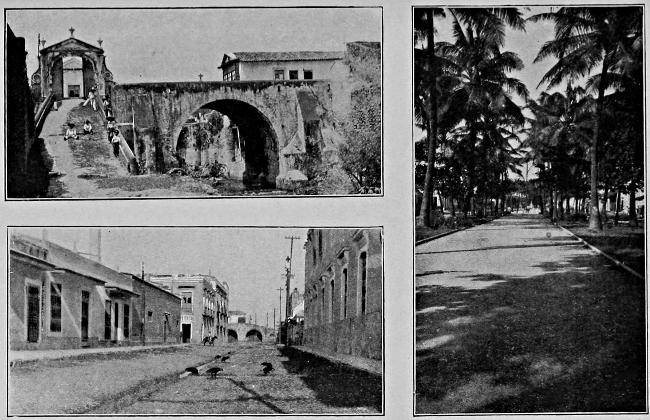

| Bridge at Orizaba.—The Buzzards of Vera Cruz.—Avenue of Palms, Vera Cruz | 98 |

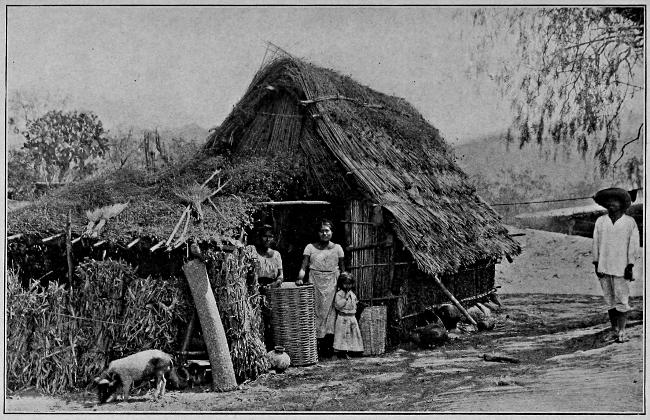

| An Indian Home in the Hot Country | 104 |

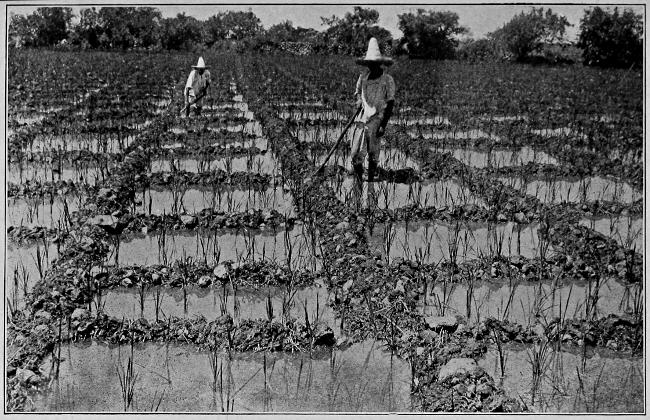

| Rice Culture | 109 |

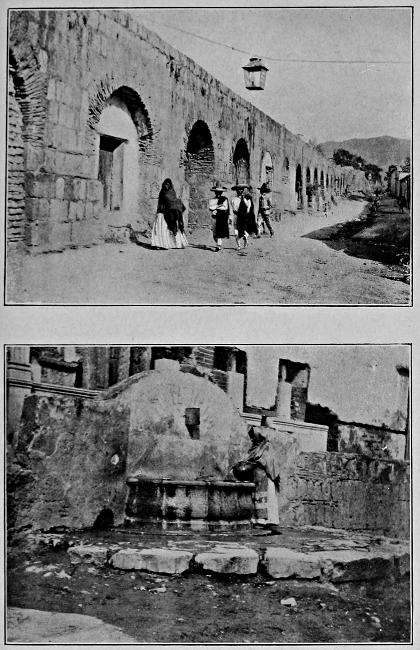

| The Aqueduct, Oaxaca.—A Fountain in Oaxaca | 116 |

| The Market-women of Oaxaca.—The Pottery-market, Oaxaca | 118 |

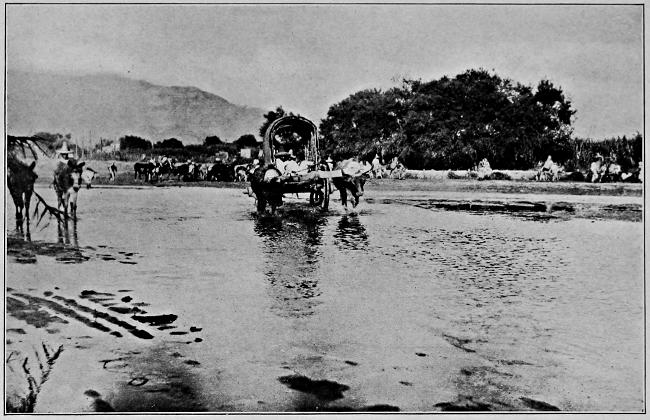

| Crossing the River on Market-day | 121 |

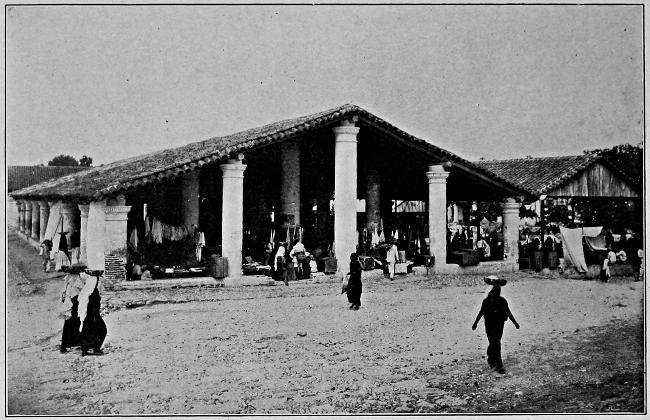

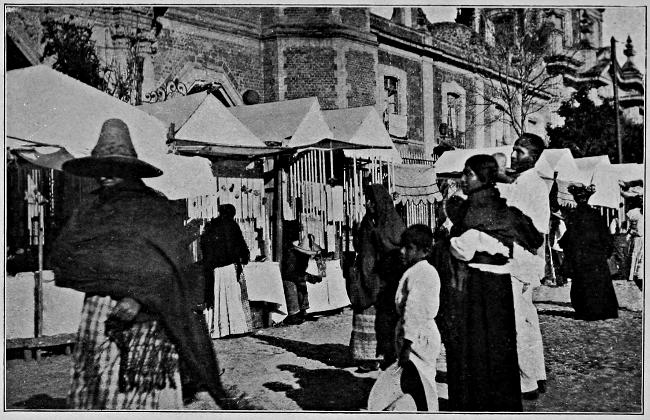

| [viii]The Market, Tehuantepec | 132 |

| Entrance to the Underground Chamber, Mitla.—North Temple, Mitla.—Hall of the Monoliths, Mitla | 157 |

| A Zapoteco Woman | 161 |

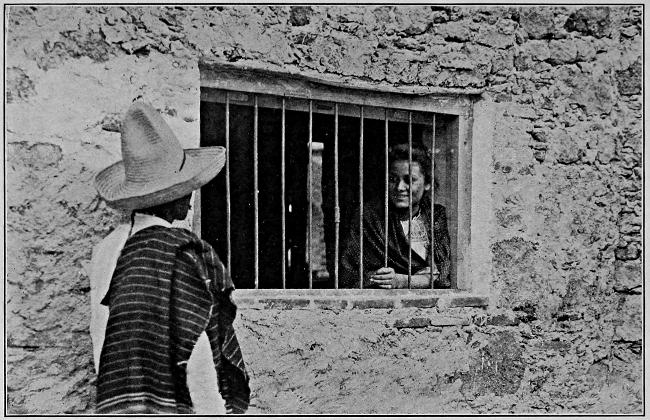

| “Playing the Bear” | 170 |

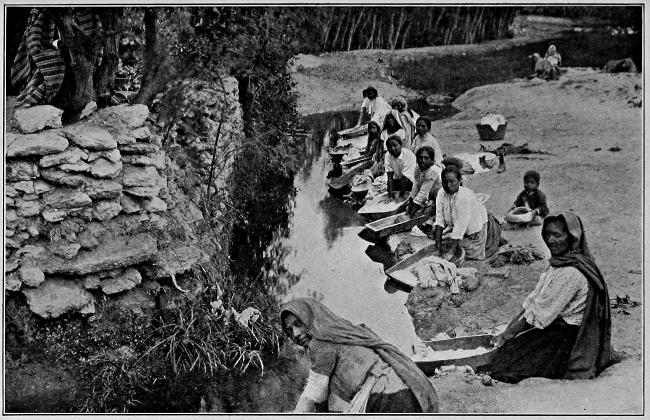

| Washing on the Banks of a Stream | 177 |

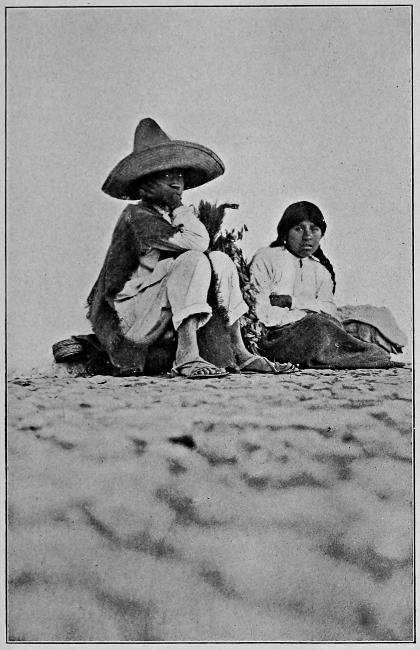

| A Peon and His Wife | 184 |

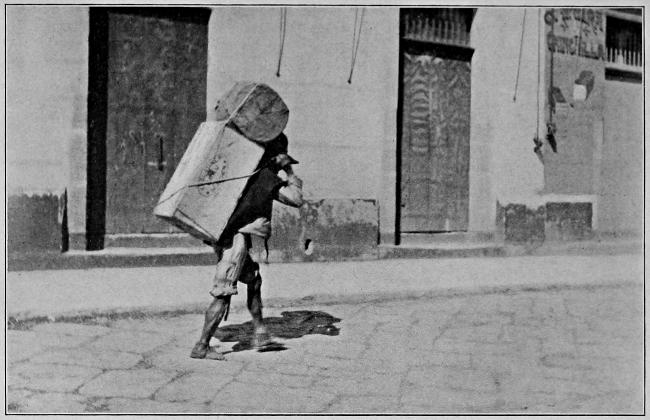

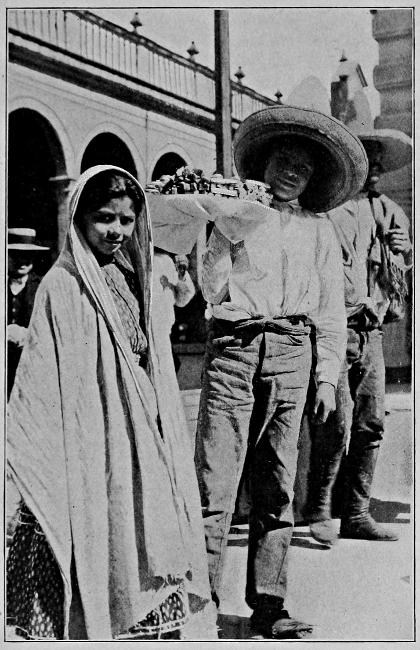

| A Cargador | 198 |

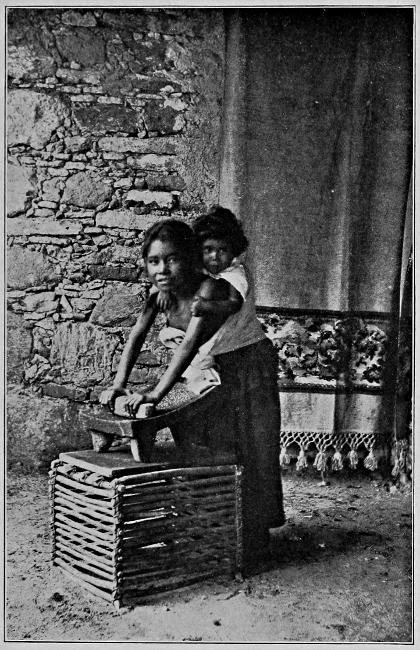

| Making Tortillas | 215 |

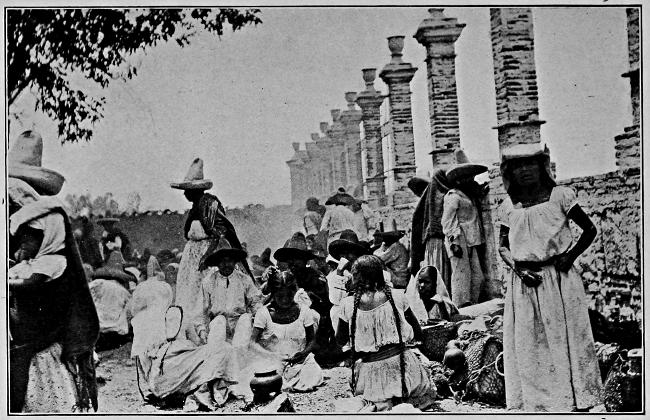

| A Mexican Market | 218 |

| Candy Boy and Girl | 220 |

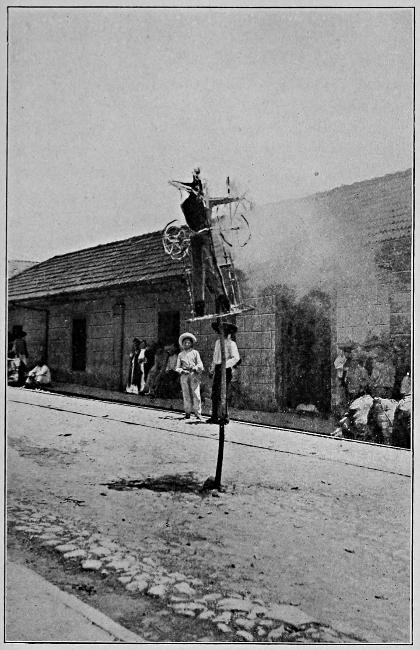

| Burning an Effigy of Judas at Easter-time | 233 |

| Candle Booths in Guadalupe | 240 |

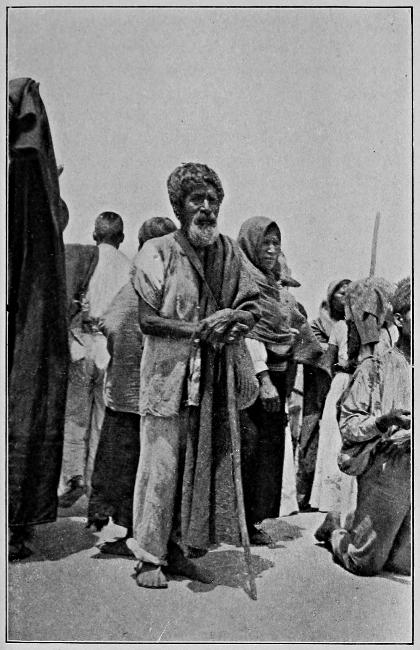

| Beggars of the City of Mexico | 242 |

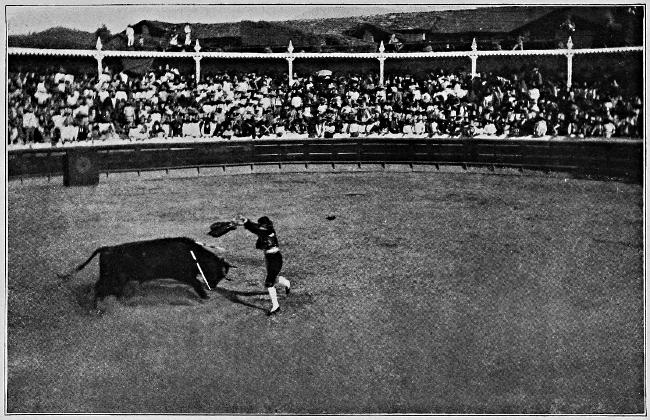

| Planting the Banderillas | 250 |

| An Aztec Schoolgirl | 266 |

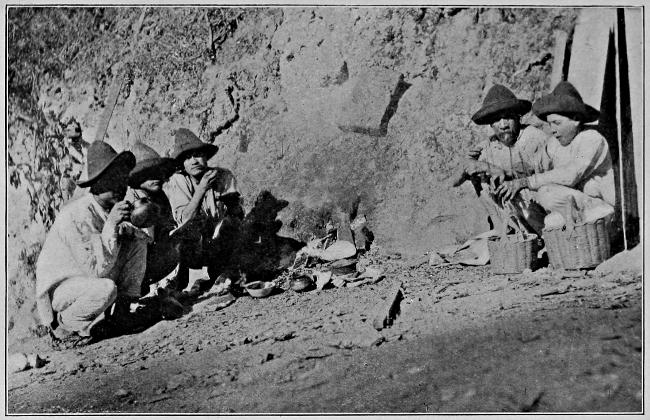

| Peon Miners at Lunch | 280 |

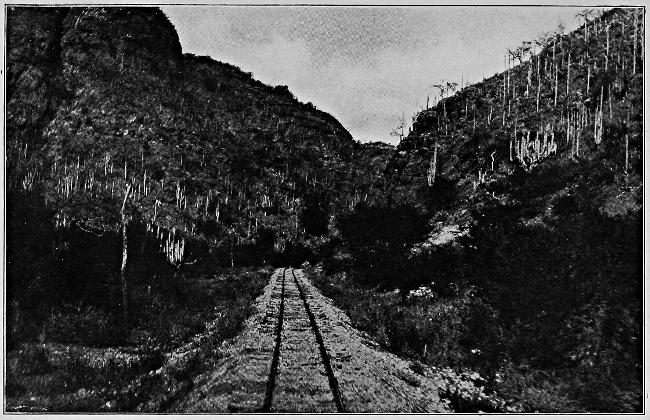

| Along the Mexican Southern Railway | 300 |

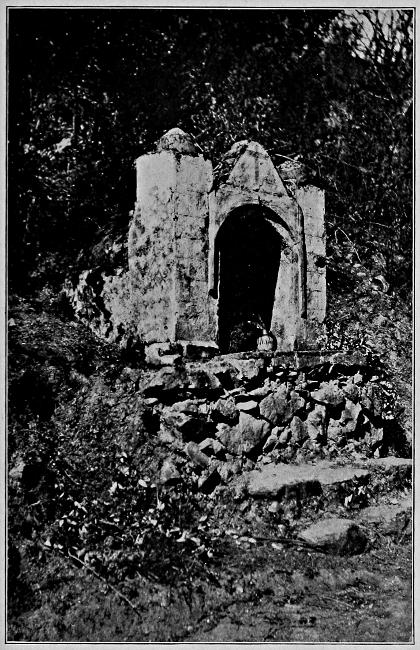

| Wayside Shrine with an Offering of Flowers | 312 |

| A Rurale | 332 |

| Army Headquarters, City of Mexico | 336 |

| A Village Church | 364 |

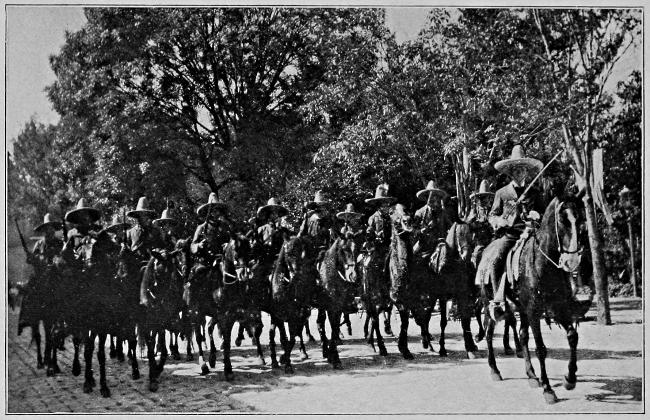

| A Company of Rurales | 370 |

| Sr. Don Francisco I. Madero | 411 |

| A Group of Peons | 419 |

| Tarahumari Indians | 421 |

| Crumbling Ruins of the Ancient Mexican Civilization | 441 |

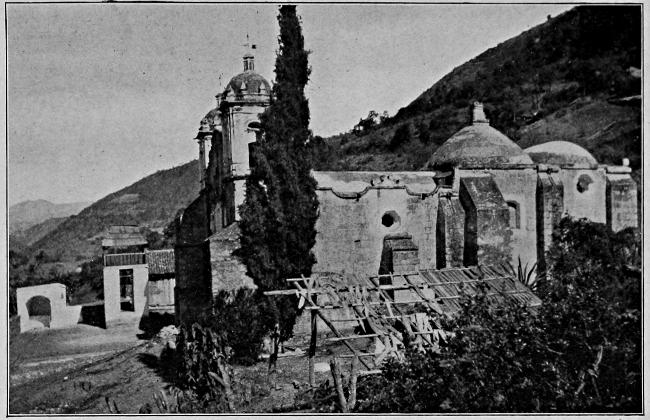

| An Old Church | 451 |

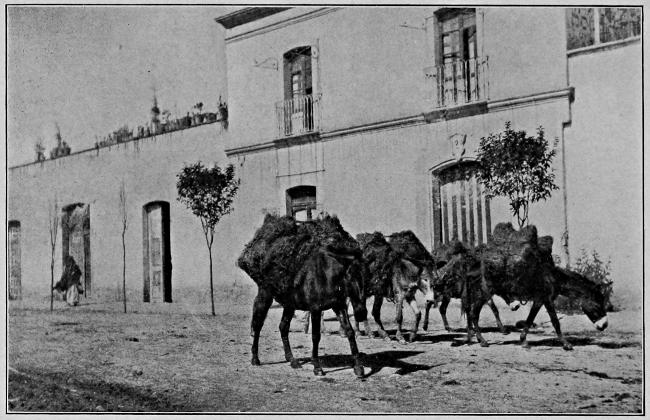

| Primitive Transportation | 457 |

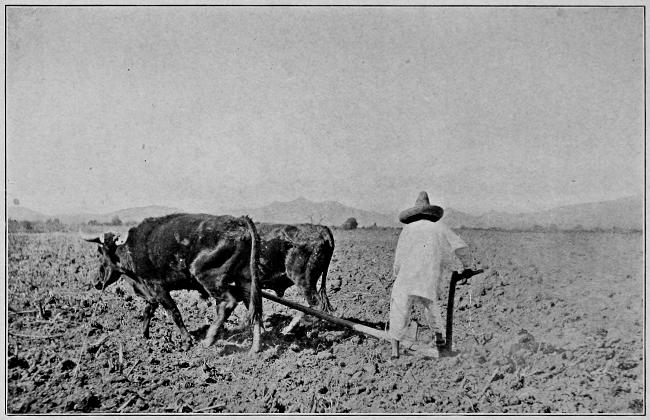

| Primitive Ploughing near Oaxaca | 465 |

Prescott says: “Of all that extensive empire which once acknowledged the authority of Spain in the New World, no portion for interest and importance, can be compared with Mexico;—and this equally, whether we consider the variety of its soil and climate; the inexhaustible stores of its mineral wealth; its scenery, grand and picturesque beyond example; the character of its ancient inhabitants, not only far surpassing in intelligence that of the other North American races, but reminding us, by their monuments, of the primitive civilization of Egypt and Hindoostan; or, lastly, the peculiar circumstances of its conquest, adventurous and romantic as any legend devised by Norman or Italian bard of chivalry.”

Mexico is a country in which the old predominates. The American visitor will bring back more distinct recollections of the Egyptian carts and plows, the primitive manners and customs, than he will of the evidences of modern civilization. An educated Mexican whom I met, chided the Americans for this tendency, for, said he, “all that is written of Mexico is descriptive of the Indians and their habits, while progressive Mexico is ignored.” This is to a great extent true, for it is the unique and ancient that attracts and holds the attention of the traveller. For this reason tourists go to Egypt to see the pyramids, sphinx and tombs of the Pharaohs.

It is not necessary for the traveller to venture out upon perilous seas to see mute evidences of a life older than printed record. In this land of ancient civilization and primitive customs, there are cities which stand out like oriental pearls transplanted to the Occident from the shores of the Red Sea. Here in Mexico can be found pyramids which are no mean rivals to those great piles on the Egyptian deserts; crumbling ruins of tombs, and palaces, and temples, ornamented in arabesque and grecque designs, not unlike the structures along the banks of the mighty Nile; and the[3] same primitive implements of husbandry which we have viewed so often in the pages of the large family Bible. Then, as an additional attraction, there is the actual presence of the aborigines, Aztec, Zapotec, and Chichimec, speaking the same language, observing the same ceremonies, and following the same customs which were old when the foreigners came.

There is no history to enlighten us as to the age of these monuments, and there are few hieroglyphics to be deciphered upon which a Rosetta Stone might shed light. The student is led to wonder whether the Egyptian civilization antedated the Mexican, or whether the former is simply the Mexican learning and skill transplanted to the Orient and there modified and improved. It is quite possible, that, while our own ancestors were still barbarians, and little better than savages, swarming over northern Europe, the early races in Mexico had developed a civilization advanced and progressive. They knew how to build monuments which in masonry and carving teach us lessons to-day. They made beautiful pottery and artistic vessels, and they used gold for money and ornaments.

Notwithstanding the fact that for a thousand[4] miles the republics of Mexico and the United States join, the average American knows less concerning Mexico than he does of many European countries; and it is much misunderstood as well as misrepresented. Mexico possesses the strongest possible attractions for the tourist. Its scenic wonders are unsurpassed in any other part of the globe in natural picturesqueness; and no country in Europe presents an aspect more unfamiliar and strange to American eyes, or exceeds it in historic interest.

Vast mountains including snow-capped Popocatapetl and Ixtaccihuatl, the loftiest peaks on the American continent, are seen here amid scenes of tropical beauty and luxuriance. Great cities are found with their customs and characteristics almost unchanged since they were built by the Spaniards; and there are still more ancient cities and temples which were built by prehistoric races.

SNOW-CAPPED POPOCATAPETL

It is a land of tradition and romance, and of picturesque contrasts. At almost every turn there is something new, unique, interesting, and even startling. It has all the climates from the torrid zone to regions of perpetual snow on the summits of the lofty volcanic peaks, and is capable of producing nearly every fruit found[5] between the equator and the Arctic circle. The softness and sweetness of the air; the broken and ever-varying line of rugged hills against a matchless sky; the beautiful views between the mountain ranges; the care-free life which is omnipresent each add their charm to the composite picture. Dirt is everywhere and poverty abounds, but even these are removed from the commonplace by the brilliant colour on every hand.

F. Hopkinson Smith in “A White Umbrella in Mexico” epitomizes this marvellously attractive country as follows: “A land of white sunshine, redolent with flowers; a land of gay costumes, crumbling churches, and old convents; a land of kindly greetings, of extreme courtesy, of open, broad hospitality. It was more than enough to revel in an Italian sun, lighting up a semi-tropical land; to look up to white-capped peaks, towering into blue; to look down upon wind-swept plains, encircled by ragged chains of mountains; to catch the sparkle of miniature cities, jewelled here and there in oases of olive and orange; and to realize that to-day, in its varied scenery, costumes, architecture, street life, canals crowded with flower-laden boats, market plazas thronged with gaily-dressed natives, faded church interiors,[6] and abandoned convents, Mexico is the most marvellously picturesque country under the sun. A tropical Venice! A semi-barbarous Spain! A new Holy Land.”

Mexico contains a greater area than is generally understood. It is shaped very much like a cornucopia with an extreme length of nineteen hundred miles, a breadth of seven hundred and fifty miles, and an area of nearly eight hundred thousand square miles. At its narrowest point, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, it is only one hundred and twenty-five miles across from ocean to ocean. There is a double range of mountains, one near the Pacific coast and the other near the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, between which lie the great table lands, or plateaus, which constitute a large part of the surface.

Transcriber’s Note: The map is clickable for a larger version, if the device you’re reading this on supports that.

Three distinct climates are found in Mexico determined by altitude. Those regions six thousand feet or more above sea level are called the tierras frias, or cold lands. This is only a relative term, for the cold does not correspond with that of our own northern states. Though termed “cold,” the mean temperature is not lower than that of Central Italy. Those lands lying at an altitude of six thousand feet, down to three thousand feet, above sea level[7] are termed the tierras templadas, or temperate lands. This is a region of perpetual humidity and is semi-tropical in its vegetation and temperature. An altitude from four thousand to six thousand feet in Mexico gives a most delightful climate.

Along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts there is a more or less broad tract called the tierra caliente, or hot land, which is a truly tropical region. Forests of dense growth cover the soil, so thick that it is impossible to penetrate them without blazing your way as you go, and in the midst of which tower trees of magnificent size, such as are to be seen only in the tropics. Here it is that nature is over-prodigal in her gifts; and here it is that the vomito, as yellow fever is called, lurks with fatal effect. The winds from the sea generally mitigate the fierce heat, especially if one can remain out of the sun during the middle of the day. Sometimes these winds on the Atlantic coast acquire great velocity, and burst forth upon the unprotected shores with terrific fury as the so-called “northers.” There is no true winter here, but there is a rainy season from June to October, and a dry season from November to May, the former being the colder.

“In the course of a few hours,” says Prescott,[8] “the traveller may experience every gradation of climate, embracing torrid heat and glacial cold, and pass through different zones of vegetation including wheat and the sugar-cane, the ash and the palm, apples, olives, and guavas.” The dwellings vary also. In the hot lands the habitations are constructed of bamboo and light poles open to sun and wind, for the only shelter needed is protection from the elements; in the temperate region the huts are made of heavier poles, and are somewhat more durable; in the higher lands they are built of adobe or stone. Sugar cane and coffee, and even the banana, will grow up to four thousand feet. Wheat grows best at six thousand feet and pines commence here too. At seven thousand feet cactus appears, and the maguey, ushering in an entirely different zone. Mexico is a country of extremes of heat and cold, poverty and riches, filth and cleanliness, education and extreme ignorance.

Every schoolboy knows of Loch Katrine and Loch Lomond in bonnie Scotland, and most people are familiar with the location of Lago di Como, in Italy. And yet I should not be surprised if fair-sized towns could be found in the United States where no one could tell whether such a body of water as Lake Chapala[9] existed or not. As a matter of fact it is ten times as large as all the lakes of Northern Italy combined; and it embraces islands larger than the entire surface of Loch Lomond. Its steely blue waters and rugged shores need only the magic pen of the novelist or poet to tell of its beauties and invest each nook and glen with romance, and the charming villas of Como to make Chapala as picturesque and fascinating as those better known lakes. It is almost a hundred miles long and thirty-three miles wide at the widest point, and covers fourteen hundred square miles. Patzcuaro and Cuitzeo are also lakes of considerable size near Chapala, and all of them are six thousand feet or more above sea level. They only await development and advertising to become popular resorts.

The vast majority of the inhabitants of Mexico are descendants of Indian races who were found there by the Spanish conquerors, and mixtures of those natives with European settlers. Of the fourteen millions of inhabitants only about nineteen per cent. are white; of the remainder, forty-three per cent. are Indians and thirty-eight per cent. mixed. There is a greater resemblance of the Mexican Indians to the Malay races of Asia than to the American Indians.[10] Their intensely black hair and eyes, brown complexion, small stature, and even a slight obliquity of the eyes bear a strong resemblance to the Japanese. I have seen it stated that, if a Japanese is dressed in Mexican costume, and a Mexican in Japanese dress, it is difficult to tell which is the Jap and which the Mexican. Students of languages say that there is a strong similarity between the Mexican tongues and oriental languages. The different tribes do not mingle much and seldom intermarry, and this fact may contribute to their physical deterioration.

AN INDIAN MAIDEN

Whence came this people? No one can answer. It is generally supposed that the Aztecs came from what are now the south-western states of the Union, and wandered into the Valley of Mexico. They were defeated by the tribes then dwelling there, and sought refuge on the shores of Lake Texcoco. There they beheld a golden eagle of great size and beauty resting on a prickly cactus and devouring a serpent which it held in its talons, and with its wings outstretched toward the rising sun. This was the sign for which they had been looking, and there they proceeded to erect their capital. They first built houses of rushes and reeds in the shallow water and lived upon fish, and constructed[11] floating gardens. As the waters receded somewhat they built more durable structures, including great palaces and temples. They extended their sway over neighbouring races beyond the Valley and conquered tribe after tribe, although never claiming dominion over more than a small portion of the present confines of Mexico. The legend of the eagle and the cactus is still preserved in the coat-of-arms of the present republic.

Of the Aztecs and their history prior to the conquest little is known, except that the country was called Anahuac. Prescott has made his “Conquest of Mexico” as fascinating as a novel, but he has shown the romantic side based upon knowledge of the most fragmentary character. The writings which pass for history were either written by bigoted priests who could not see anything good in an idolatrous people, and who, to please the leaders, painted the Aztecs in blackest colours to justify the cruel measures taken, or they were written by Spaniards who never visited the country of which they presumed to write. As it has been said, “a most gorgeous superstructure of fancy has been raised upon a very meagre foundation of fact.” Their civilization was in many respects marvellous and far ahead of that of any[12] other race on the western hemisphere. Under the Montezumas they had grown into a powerful nation, and their rule was one of barbaric splendour and luxury.

The Aztecs succeeded an older race called the Toltecs who were also far advanced in civilization. They were nature worshippers and not only did not indulge in human sacrifices, but were averse to war and detested falsehood and treachery. A Toltec noble is said to have instructed his son after the following manner before sending him away from home: “Never tell a falsehood, because a lie is a grievous sin! Speak ill of nobody. Be not dissolute, for thereby thou wilt incense the gods, and they will cover thee with infamy. Steal not, nor give thyself up to gaming; otherwise thou wilt be a disgrace to thy parents, whom thou oughtest rather to honour, for the education they have given thee. If thou wilt be virtuous, thy example will put the wicked to shame.”

Both of these races were also great builders and sculptors and had cultivated the art of picture-writing. They were well housed, decently clothed, made cloth, enjoyed vapour baths, maintained schools, and had a large assortment of household gods. They mined some,[13] and in agriculture, at least, were far ahead of the Mexicans of to-day.

The vandalism of the Spaniards in destroying the writings and other records of the early races is rebuked by Prescott as follows: “We contemplate with indignation the cruelties inflicted by the early conquerors. But indignation is qualified with contempt when we see them thus ruthlessly trampling out the sparks of knowledge, the common boon and property of mankind. We may well doubt which has the strongest claim to civilization, the victor or the vanquished.”

The Mexico of to-day cannot be understood without looking for a moment at its settlement and the manner of the conquest. The Spanish conquistadores who flocked to these shores with Cortez were a different race from those early settlers, who, persecuted and denied liberty of conscience in the land of their birth, sought a new home on our own hospitable shores. With the union of the crowns of Castille and Aragon by the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella, and the discovery of the New World, Spain had suddenly leaped to the front, and become, for a time at least, the greatest nation of the day. Ships were constructed in great numbers and[14] sent out, filled with voyagers, “towards that part of the horizon where the sun set.”

In the sixteenth century she had practically become the mistress of the seas and the most powerful nation in the world. Her soldiers were brave and the acknowledged leaders of chivalry, but the curse of the Spaniards was their thirst for gold, and her decay was rapid. When Cortez and his band of adventurers came to the court of Montezuma, and saw the lavish display of vessels and ornaments made of the precious metal, they thought they had discovered the land of gold for which they were searching. Attracted by the glowing reports of untold wealth, thousands of Spaniards soon followed the first bands of conquistadores, and they rapidly spread over the entire country occupied by the Aztecs, ever searching for the mines from whence this golden harvest came. While the leaders were imprisoning and torturing the Aztec chieftains to force them to give up the hiding places of their treasures, the priests, who everywhere accompanied the soldiers, were baptizing thousands into the new faith and using the confessional for the same end. Thus religious bigotry and the mania for worldly riches went side by side, and ever ringing[15] in the ears of both priest and warrior was the refrain:

Shortly after the conquest all the desirable lands were parcelled out among the invaders and the few Indian caciques who had helped, with their powerful influence, in their subjugation. The Spaniards rapidly pacified the country, for the Aztec masses, however warlike they may have been before the coming of the Spaniards, were subdued by one blow. They were soon convinced that opposition to the power of Spain was useless. The priests, also, through their quickly acquired influence, taught submission to those whom God, in His infinite wisdom, had placed over them. Chiefs who would not yield otherwise were bribed to use their power over their vassals in favour of the Spaniards. Thus by force, bribery, intrigue, diplomacy, treachery, and even religion, the Indians were reconciled and the spirit of opposition to the Spaniards broken. The result was a new and upstart nobility who ruled the country with an iron hand in the course of a few decades; and the natives, with the exception[16] of the chiefs, were made vassals of these newly made nobles.

An era of building followed, in which great palaces after the grandiose ideas of Spain were constructed by Indian workmen. Churches were built with lavish hand, for these nobles thought to atone for their many misdeeds by constructing and dedicating places of worship to Almighty God, who, according to the teaching of the priest, was the God of the poor, oppressed Indian as well as the God of the haughty Spaniard who had enslaved him. As one writer has said: “When John Smith and his followers were looking for gold mines in Virginia and the Pilgrims were planting corn in Massachusetts, an empire had been founded and built up on the same continent by the Spaniards, and the most stupendous system of plunder the world ever saw was then and there in vigorous operation.” Cortez was searching for “a people who had much gold” of which he had heard. It was not God but gold that drew him in his campaign over Mexico. He did not aim to Christianize the natives so much as enrich himself and acquire empire for his sovereign, and religion was a subterfuge plausible and popular in that age.

“I die,” said the patriot Hidalgo, when about[17] to be executed in 1811, “but the seeds of liberty will be watered by my blood. The cause will not die; that still lives and will surely triumph.” His prediction came true, and freedom from the Spanish yoke of three centuries was secured ten years later after the shedding of much blood. Peace did not follow at once, however, for in the fifty years succeeding the declaration of independence the form of government changed ten times, and there were fifty-four different rulers, including two emperors and a number of dictatorships. Special privileges are difficult to eradicate when established by long usage, and those enjoying them yield only to force. The Church, which had imposed on the people such a vast number of priests, friars, and nuns, and had acquired the most of the wealth of the country, clung with the grip of death to its privileges and property. The changes came gradually, but it has been a half-century since the Church and State were formally separated by constitutional amendment. The bigoted and despotic Romanism, which was allied with the Spanish aristocracy, has at last been subdued. A more tolerant spirit is springing up towards other forms of religious faith through the efforts of a powerful and liberal government. Education is also freeing the people[18] from the superstitious ignorance which has hitherto prevailed in most parts of Mexico. There are occasional outbursts of fanaticism, but they are quickly suppressed, and the government is making an honest effort to preserve freedom of worship to all faiths.

The United States of Mexico is a federation composed of twenty-seven states, three territories, and the federal district in which the capital is located. The states are sovereign within themselves and are held together under a federal constitution very much like our own. This constitution was adopted on the 5th of February, 1857, and its semi-centennial was recently celebrated with a few of the original signers present. There is a congress composed of two bodies, the Senate and Chamber of Deputies which meets twice each year. Each state is represented in the former by two senators and in the latter by one representative for each forty thousand of population. The right of suffrage is restricted so that only a small proportion of the population can exercise that privilege. They have not really reached popular government, and politics, as we know them in the United States, do not exist. A presidential election scarcely caused a ripple on the surface. President Diaz was no doubt the popular[19] choice, but comparatively few votes were cast at his last election. The rule of the Diaz government although decidedly autocratic was beneficient, and has redounded to the good of the country. Though practically an absolute ruler, President Diaz always acted through the regularly organized channels of a complete form of republican government, and outwardly, at least, there was no semblance of a dictatorship.

Mexico is a country of great natural resources and possibilities which have been only partially developed. Its soil is remarkably fertile and could support five times, and, if water could be found on the plateaus, ten times the present population. And I say this notwithstanding the fact that one man has said that Mexico is the poorest country south of Greenland, and north of the south pole. The flora of the country, among which are many useful and medicinal plants, is exceedingly rich and varied. More species of fibre plants are found there than in any other country, and the commercial utility of these plants is not yet fully appreciated. In no country has there been greater waste of natural resources than the Spanish conquerors caused in Mexico. It is as a mining country that Mexico has been best known and the Mexican silver mines have been[20] famous ever since the discovery of the New World, and they are still the greatest single source of wealth. Some of them which have been worked for centuries are still yielding small fortunes in the white metal each year.

The Mexican has his own view of the United States and does not call our boasted progress and much-vaunted civilization, with its hurry, brusque ways and the blotting out of the finer courtesies, an improvement. He appreciates our mechanical contrivances and electrical inventions, but prefers to enjoy life after his own fashion and in the way he thinks that God intended in order to keep men happy. The civilization received by Mexico in the sixteenth century was looked upon as equal to the best in existence, and to this was added an ancient civilization found in the country. From these sources a manner of living has been evolved which bears evidences of culture and refinement. This system has flowed on through the intervening centuries, undisturbed by the march of progress, until the last quarter of a century. Things cannot be changed to Anglo-Saxon standards in a year, or two years, or even a generation. To Americanize Mexico will be a difficult if not impossible undertaking, and there are no signs of such a transition.[21] Americans who live there fall into Mexican ways and moral standards more frequently than Mexicans are converted to the American point of view. The influence of traditions, customs, and climate, and the centuries-old habit of letting the morrow take care of itself is too great to be overcome.

The traveller going to Mexico by rail will discover that that country begins long before the border is reached. While travelling over the great state of Texas, where the dialect of the natives is as broad as the rolling prairie round about, he is reminded of our southern neighbour by the soft accents of the Spanish language, or by the entrance into the coach of a Mexican cowboy with his great hat and picturesque suit. Leaving beautiful San Antonio, which is a Spanish city modernized, it is but a few hours until the train crosses the muddy Rio Grande at Laredo and, after passing an imaginary line in the centre of the stream, enters the land of burros and sombreros, a land of mysterious origin and vast antiquity.

“THE LAND OF BURROS AND SOMBREROS”

The custom officials are very polite and soon affix the necessary label “despachado” to the baggage. “Vamonos” (we go) replaces the[23] familiar “all aboard,” and the train moves out over a country as flat and dreary as a desert. By whichever route the traveller enters Mexico, the journey is very uninteresting for the first half day. There is nothing to relieve the monotony except the telephone and telegraph poles, with their picturesque cross-arms standing out on the desert waste like giant sentinels. There is no vegetation except the prickly pear, cactus, and feather duster palms, for frequently no rain falls for years at a time. It seems almost impossible that anything can get moisture from the parched air of these plains. But nature has strange ways of adapting life to conditions. A good illustration of this is seen in the ixtle, a species of cactus whose leaves look as if they could not absorb any moisture because of a hard varnish-like coat. Whenever any water in the form of dew or rain appears, however, this glaze softens and the plant absorbs all the moisture available and then glazes over again as soon as the sun comes out.

There is very little life here. Sometimes at the stations a few adobe huts are seen where dwell the section hands, and a few goats are visible which, no doubt, find the prickly pear and cactus with an occasional railroad spike[24] thrown in for variety, much more satisfying than an unchanging diet of tin cans such as falls to the lot of the city goat. The mountain ranges then appear, and never is the traveller out of sight of them in Mexico. On either side, toward the east and toward the west, is a range with an ever varying outline, sometimes near, then far,—advancing and retreating. At a distance in this clear atmosphere their rough features are mellowed by a soft haze into amethyst and purple; nearer they sometimes rise like a camp of giants and are the most fantastic mountains that earthquakes ever made in sport, looking as if nature had laughed herself into the convulsions in which they were formed.

The Mexican National Railway follows a broad road that was formerly an Indian trail, and the track crosses and recrosses this highway many times. By this same route it is probable that early Mexican races entered that country and marched down toward the Valley of Mexico. It was by this way that General Taylor invaded the country during the Mexican War and several engagements took place along the line of this railroad.

The first town of any size is Monterey, capital of the state of Nuevo Leon, the oldest and one of the most important cities in Northern[25] Mexico. It lies in a lovely valley with high hills on every side. It is at a lower altitude than the cities farther south on this line and enjoys a salubrious climate. Monterey is a very much Americanized town and has great smelters, factories, and breweries, but it also boasts of beautiful gardens and some old churches. The Topo Chico hot springs only a few miles away have a great reputation for healing. Here it was, in 1846, that General Taylor overcame a much superior force of the enemy under General Ampudia in a desperate and stubbornly disputed battle lasting several days, the contest being hotly fought from street to street. The Mexican troops entered the houses and shot at the American soldiers from the windows and roofs. It is now a city of more than fifty thousand people.

Leaving Monterey, the road soon begins a gradual ascent to the higher plateaus and reaches the zone called tierra fria, or cold country. This name would seem a misnomer to one who hails from the land of snow and ice, for the mean temperature of this “cold land” is that of a perpetual spring such as is enjoyed north of Mason and Dixon’s line. It is properly applied to all that part of Mexico which is six thousand feet or more above the[26] level of the sea and the greater part of the immense central plateaus comes within this designation. These plains which comprise about two-thirds of the entire country, are formed by the great Andes range of mountains which separates into two great cordillerias near Oaxaca and gradually grow farther and farther apart as they approach the Rio Grande. The western branch crowds the shore of the Pacific and the eastern follows the coast line of the Gulf of Mexico, but the latter keeps at a greater distance from the sea, thus giving a wider expanse of the hotlands. They are not level tablelands, these mesas, as they always slope in some direction. The arid condition follows as a natural course, for the lofty ranges cause the rain to be precipitated on the coast lands except during certain seasons in the year when the winds change. When the rains do come, a miracle is wrought, and the sombre landscape blossoms into a lively green dotted with flowers. It is rare to find such great plains at so high an altitude. Although now almost barren of trees it is probable that in early times these tablelands were covered with a forest growth principally of oak and cypress. This is evidenced by the few groves that yet remain, in which many of the trees are of[27] extraordinary dimensions. The Spaniards completed the spoliation that had been begun by the earlier races.

Saltillo, the next important town, is the capital of the State of Coahuila. It is interesting to Americans, as just a few miles from here and near the railway took place the battle of Buena Vista, at the village of that name. Here the Americans under General Taylor sent double their number of Mexicans under the notorious Santa Anna, flying on February 23rd, 1847.

Still climbing, the road continues toward the capital, passes through a rich mining district, and after the Tropic of Cancer is crossed the traveller is in the Torrid Zone, the spot being marked by a pyramid. Plains, seemingly endless, where for a hundred miles the long stretch of track is without a curve, are traversed, and so dry that wells and water-tanks are objects of interest. It is mostly given up to vast haciendas. Some of these estates still remain in the hands of the original families as granted at the time of the conquest.

It was on these vast, seemingly barren plateaus that the hacienda reached its highest development. One does not go far south of the Rio Grande before the significance of this[28] institution in Mexican life becomes apparent. Sometimes when the train stops at a little adobe station with a long name, the traveller wonders what is the need of a station; for there is no town and only a few native huts clustered around the depot. However a glance around the horizon will reveal the towers and spire of a hacienda nestling at the foot of the hills perhaps several miles away. In the olden times they took the place of the feudal castles of the middle ages in Europe and in these sparsely settled regions they were especially necessary. Within the high walls which often surround them for protection were centralized the residence of the owner and all of his employees and the necessary buildings to store the products of the soil. The hacendado’s home was a large, roomy building, for, since there were no inns, the traveller must be entertained and hospitality was of the open-handed sort. The travel-worn wayfarer was welcomed and no questions asked. His wants were supplied and at his departure the benediction “Go, and God be with you,” followed him. Even yet at some of these great haciendas, where the old-time customs prevail, the bell is rung at mealtime and any one who hears it is welcomed at the table.

The term hacienda has a double meaning, for it is applied both to the great estates and to the buildings. It is a patriarchal existence that is led by these landed proprietors. A thousand peons and more are frequently attached to the estate. Near the station of Villa Reyes is a great hacienda which once controlled twenty thousand peons. These must be provided with homes, but a room fifteen feet square is considered sufficient for a family, no matter how large. Little furniture is needed, for they live out of doors mostly, and mats, which can be removed during the day, take the place of cumbersome beds. The administrador, who may be an Indian also, and other heads, live better and are housed in larger quarters. A church is always a part of the estate and a priest must be kept to furnish spiritual solace, as well as a doctor to administer to those whose bodies are infirm. Schools are also maintained by most of the proprietors to-day. The peon must be provided with his provisions each week and a little patch of ground for his own use. Around the buildings lie the cultivated fields, and from early morn until the shades of night have fallen, lines of burros are constantly passing in and out laden with wood, corn, vegetables, poultry,[30] boxes of freight, and all the other items of traffic which are a part of the life of this great household.

After piercing another of the mountain ranges which intersect the country from east to west, and traversing miles of fertile fields and gardens bearing semi-tropical fruits and vegetables, the road enters a valley and the city of San Luis Potosi is reached. Every country has its Saint Louis, but only one has a Saint Louis of the Treasure, and that is San Luis Potosi, the capital of the state of that name. It lies in a spreading plain of great fertility—made so by irrigation—whose gardens extend to the encircling hills that are rich in the mineral treasures which give the city its name. The San Pedro mines near here alone produce an annual output of several millions. These mines were revealed to Spaniards by an Indian who had become converted to Christianity. There is a mint here that coins several millions of dollars each year.

MARKET SCENE IN SAN LUIS POTOSI

San Luis Potosi is not a new city nor has its growth been of the mushroom variety. Founded in the middle of the sixteenth century, it preserves to-day in wood and stone the spirit of old Spain transplanted by the conquerors to the new world. Drawn hither by the reports[31] of gold, the Spanish cavalier stalked through the streets of this town in complete mail before the Mayflower landed on the shores of Massachusetts. The priests were chanting the solemn service of the church here long before the English landed at Jamestown. Dust had gathered on the municipal library, which now contains a hundred thousand volumes, centuries before the building of the first little red school house in the United States. Before New York had been thought of, the drama of life was being enacted here daily after Castillian models.

It is a cleanly city and the bright attractive look of its houses is refreshing. A city ordinance compels the citizens to keep up the appearance of their houses, and the colours remind one of Seville. It is pleasant to walk along these streets and through the plazas with their trees and flowers and fountains.

I will never forget my arrival in this city. We reached there about midnight, having been delayed by a wreck; and a number of mozos pounced upon the party of Americans who had been dropped by the belated train, each one eager to carry some of the baggage. We were marched through the Alameda, which, for a wonder, adjoins the station, on walks shaded[32] by broad-leaved, tropical plants, down narrow streets and around several corners to the hotel. Arrived here it was only after several minutes of vigorous knocking that a sleepy-looking porter opened the door, and we entered the hotel and walked down the hall through a line of sleeping servants. The room finally assigned to my friend and myself was thirty-four feet long, sixteen feet wide and about twenty-five feet high, and there were four great windows extending nearly from ceiling to floor and protected by heavy iron bars which made them look like the windows of a prison. It had doubtless been some church property at one time, but whether monastery or convent I did not learn.

COCK-FIGHTING IN MEXICO

Not all this city is pretty however, for distance often lends enchantment, and a closer scrutiny takes away much of this charm. I saw filth on the streets here that can only be duplicated in old Spain itself. There are numerous churches and several of them are quite pretentious and contain some fine paintings. On the façade of one church there is a clock presented by the king of Spain in return for the largest piece of gold ever found in America. San Luis is a thrifty city as Mexican towns go and has numerous manufacturing establishments,[33] including a large smelting works, the Compania Metallurgica, and is an important railroad centre. It is distant from the City of Mexico three hundred and sixty-two miles, and has a population of seventy thousand souls.

This city claims quite a number of American families as residents and many of the storekeepers have been somewhat Americanized, for they actually seem to be on the lookout for business. The state capitol is a very interesting building. While looking through this palace I saw the “line up” of petty offenders who were being sent out to sweep the streets. They were the worst looking lot of pulque-drinkers I ever saw and were clothed in rags. Each one was given a handful of twigs with which he was obliged to sweep the streets and gutters, and they were sent out in gangs, each under a police officer. The vices of these people are generally more evident than their virtues. They are inveterate gamblers. Wherever one goes (not alone in San Luis Potosi) fighting cocks are encountered tied by the leg to a stake with a few feet of string. Or they may be carried in the arms of young would-be sports who brag of their birds to any one who will listen. One day I saw a man with a cock whose head was one bloody-looking mass. He had just cut off[34] the rooster’s comb. When I stopped and looked, the Indian laughed as though it were a great joke and said he was “much sick.” This was done so that in a fight his opponent could not catch hold of the comb. Itinerant cock-fighters who travel across the country carrying their birds in hollow straw tubes are popular fellows.

Leaving San Luis Potosi at noontime the traveller catches his last glimpse of this city where

The train soon enters a rich agricultural belt and the country becomes more populous. Giant cacti towering straight and tall to a height of fifteen or twenty feet are a common sight.

Dolores Hidalgo where the patriot-priest first sounded the call to liberty and revolution is passed. Then comes Querétero, which occupies a prominent place in Mexican history and is the last city of any size on the way to the capital. Here the treaty of peace between Mexico and the United States was negotiated. In this city Maximilian played the last act in the[35] tragedy of the empire. He was captured while attempting to escape on June 19th, 1867, and was shot on the Cerro de las Campañas, a little hill just outside the city. With him were shot Generals Miramon and Mejia. Maximilian died with the cry of “Viva Mexico” on his lips. There is a magnificent aqueduct here which, because of the high arches, looks like the old ruined aqueduct seen on approaching Rome. The tallest arch is nearly one hundred feet. The entire length of the aqueduct is about five miles and it is still in use. There are a number of factories for cotton goods. Among them is the great Hercules Mill which employs more than two thousand hands. The grounds are laid out in elaborate and beautiful style.

After climbing the mountain range again until an altitude of nearly ten thousand feet has been reached, the descent begins and the beauty of the Valley of Mexico unfolds. Fleeting glimpses of the scene may be caught through little gaps in the mountains until finally the train enters a pass and the traveller has his first view of the City of Mexico. Beyond the glittering towers and domes of the modern city on the site of the ancient Aztec capital lies the bright expanse of the lakes, and still further in the distance is seen the encircling[36] girdle of mountains like a protecting wall around this enchanted scene.

There are many other cities situated on these vast plateaus, for the tierra fria has always maintained the bulk of the population in spite of the extraordinary richness of the lowlands. They are growing in size as manufacturing establishments become more numerous. A number of them like Chihuahua, Aguas Calientes, Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Durango, and Leon are interesting cities of from thirty to forty thousand inhabitants and all of them are old. Chihuahua (pronounced Che-wa-wa) is the capital of the state of that name which is the largest state in the republic and is twice as large as the state of Ohio. It has a population of less than four hundred thousand. This will serve to give a little idea of the vastness of these great tablelands and the sparseness of population. It is chiefly devoted to great ranches where hundreds of thousands of cattle are grazed.

It may be interesting to note that cattle ranching originated in this state. All the terms used on the range and roundup are of Spanish origin and are the same that have been employed for centuries. One man here is the owner of a cattle ranch covering seventeen million[37] acres. The traveller might journey for days and cross ranges of mountains and not pass beyond his princely domain. There are a number of cattle ranches of from one to two million acres and a few Americans are now entering the field here since the public domain in the United States has dwindled so much.

Two cities, Guadalajara and Puebla, have long disputed for the honour of second city in the republic. Puebla is situated southeast of the capital and is a city of tiles, for tiles are used everywhere from the domes of churches to floors for the devout to kneel upon. It is the capital of the richest state in the republic and has probably seen more of the vicissitudes of war than any other city. It has been captured and occupied successively by Spaniards, Americans and French and by revolutionists times without number. This city was the scene of General Zaragossa’s victory on May 5th, 1862, when he repulsed the French forces just outside the city’s gates. This victory is celebrated each year as the “cinco de Mayo” (Fifth of May) and is the great anti-foreign day. Formerly foreigners did not show themselves on the street on this day, but that antagonistic sentiment has disappeared. In 1906 because of labour disturbances for which American[38] agitators were blamed trouble was feared on this day, but it passed off without an unpleasant incident. This city was founded as early as 1532. Its history is romantic and full of legends recounting the many visits of the angels. Angels appeared one night and staked out the city. Again, while the cathedral was being built, the angels came after nightfall when the city was wrapped in slumber and built a great part of the tower. At another time the angels were marshalled in mighty hosts just over the city. The people can even point out to you the very places where the angelic visitors roosted. The ecclesiastical records vouch for these appearances of the heavenly visitors and the people devoutly believe in them.

Puebla has wide streets—for Mexico—and many beautiful plazas with flowers and fountains. It is also noted for its bull-fights and has two bull-rings. These are in use nearly every Sunday and frequently for the benefit of or in honour of some church feast or departed saint. The public buildings are very creditable and the city contains good schools and hospitals. A goodly number of foreigners live here, especially Germans. I have noticed that the Germans affiliate with the Mexicans[39] much better than Americans generally do. One reason is that they come here to establish their permanent residence, while Americans, like the Chinese, desire to make their fortunes and then return to the land of their birth to spend their later days.

Puebla has become quite a manufacturing city and especially of cotton goods, paper, flour and soaps. Onyx and marble are quarried near here, and a large number of workmen are employed in the quarries and in the establishments preparing these materials for the market. Several railroads now reach this city, and its importance as an industrial centre is increasing each year.

All kinds of grains that are produced in the temperate zones will grow on the tablelands of Mexico wherever there is sufficient rain or water to be obtained by irrigation. A constantly increasing amount of acreage is being made available through the extension of the irrigation system, but its possibilities are only beginning to be realized. Corn, which is such a great article of food with the Mexicans, is by far the most valuable agricultural product and several hundred million bushels are produced each year. Wheat was first introduced in Mexico by a monk who planted a few grains[40] that he had brought with him. This grain is now raised quite extensively in some districts but frequently there is not enough for even local consumption. Cotton is also produced in a number of the states.

THE MAGUEY

Mexico is especially rich in fibre-producing plants and no country in the world has so many different varieties. All of these belong to the great cactus, or agave, family. The value of the cactus has never been fully appreciated but new uses are being found for it constantly, and new kinds with valuable qualities are being discovered in Mexico almost yearly. Perhaps the most valuable plant of this family that is being cultivated in Mexico to-day is that species of the agave that produces the valuable henequen fibre of commerce. This plant very much resembles the maguey and grows on the thin, rocky, limestone soil of Yucatan. From this fibre is made most of the binder twine and much of the rope used in the United States. It has the threefold qualities of strength, pliability and colour. In the past twenty years the cultivation of henequen has grown to enormous proportions, and some of the planters have become millionaires almost rivalling the famous bonanza kings of olden times. The amount of henequen, or sisal, fibre exported to the United[41] States from 1880 to 1905 was nine million, two hundred and nineteen thousand, two hundred and fifteen bales at an estimated value of $300,988,072.66. In 1902 the exports reached a maximum, and amounted to $34,185,275. All of this fibre is exported through the port of Progreso.

Several species of the cactus family are being experimented with, and it is claimed that they will produce an excellent quality of paper pulp. This may help to solve the problem that now bothers paper manufacturers as the forests of spruce disappear before the woodsman’s ax. The graceful maguey, the agave americana, is cultivated almost everywhere on the plateau lands. It also produces a valuable fibre, but this plant is not cultivated primarily for that purpose. The ancient races used the thorns for pins and needles; the leaves furnished a kind of parchment for their writings and thatch for their roofs; and the juice when fermented made a—to them—most delicious drink. On the plains of Apam just east of the Valley of Mexico and north of Puebla the cultivation of the maguey has reached the highest development.

The good housewife in the United States who carefully nourishes the century plant, hoping that at least her descendants will have the[42] pleasure of seeing it blossom at the end of a hundred years, would be surprised to see the immense plantations consisting of thousands of this same plant growing here. The plant, commonly called the maguey, is a native of Mexico and grows to great size. It flourishes best in rocky and sandy soil and is quite imposing in appearance. Its dark green, spiked leaves which lift themselves up and spread out in graceful curves, sometimes reach a length of fifteen feet, and are a foot in breadth and several inches thick. It requires from six to ten years for the maguey to mature on its native heath. When that period arrives a slender stalk springs up from the centre of these great leaves, twenty to thirty feet high, upon which a great mass of small flowers is clustered. This supreme effort exhausts the plant and, its duty to nature having been performed, it withers and dies.

This is not the purpose for which the maguey is raised on the big plantations where the rows of graceful century plants stretch out as far as the eye can reach in unwavering regularity. On these plantations the maguey is not permitted to flower. The Indians know, by infallible signs, almost the very hour at which it is ready to send up the central stalk, and it is[43] then marked by an overseer with a cross. The stalk is now full of the sap which is the object of its culture. Other Indians follow up the overseer and, making an incision at the base of the plant, extract the central portion, leaving only the rind which forms a natural basin. Into this the sap, which is called agua miel, or honey-water, and which is almost as clear as water and as sweet as honey, collects. So quickly does this fluid gather that it is found necessary to remove it two or three times per day. The method of gathering this sap is extremely primitive. The Indian is provided with a long gourd at the lower end of which is a horn. He places the small end, which is open, in the liquid and, applying his lips to an opening in the large end, sucks the sap up into the gourd. The sap is then emptied into a receptacle swung across his back which is made of a whole goat-skin or pig-skin with the hair on the inside. The maguey plant will yield six or more quarts of this “honey-water” in a day and the supply will continue from one to three months. It is then exhausted and withers and decays. However, a new shoot will spring up from the old roots without replanting.

This innocent looking and savoury sap is then taken to a building prepared for the purpose[44] and there poured into vats made of cowhides stretched on a frame. In each vat a little sour liquor called “mother of pulque” has been poured. This causes quick fermentation and in a few hours the pulque of the Mexican is ready for the market. It is at its best after about twenty-four hours fermentation. It then has somewhat the appearance and taste of stale buttermilk and a rancid smell. After more fermentation it has the odour of putrid meat. The skins in which it is carried increase this disagreeable odour. The first taste of pulque to a stranger is repellant. However, it is said that, contrary to the general rule, familiarity breeds a liking. Great virtues are claimed for it in certain ailments and it is said to be wholesome. However this is not the reason why the peons drink pulque in such great quantities. Several special trainloads go in each day to the City of Mexico over one road, besides large amounts over other routes and it is a great revenue producer for the railroads. The daily expenditure for pulque in the City of Mexico alone is said to exceed twenty thousand dollars. Physicians say that the brain is softened, digestion ruined and nerves paralyzed by a too generous use of this liquor. Many employers of labour will not employ labourers from the[45] pulque districts if they can possibly get them from other sources. Tequila and Mescal are two forms of ardent spirits distilled from a juice yielded by the leaves and root of the maguey. They are forms of brandy that it is best for the traveller to leave alone.

The City of Mexico represents progressive Mexico. In it is concentrated the wealth, culture and refinement of the republic. It is the political, the educational, the social and the commercial centre of the whole country. It is to Mexico what Paris is to France. In fact it would be Mexico as Paris would be France. The same glare and glitter of a pleasure-loving metropolis are found here, and within the same boundaries may be seen the deepest poverty and most abject degradation.

MAP OF THE VALLEY OF MEXICO

“Wait until you get to the City of Mexico,” said an educated Mexican to me as we were crossing the sparsely-settled tablelands of northern Mexico, where the only inhabitants are Indians. The Mexicans are proud of their city and are pleased to have it likened to the gay French capital, for their ideals and tastes are fashioned after the Latin standard rather than the American. The French, they say,[47] have the culture and can embrace a la Mexicana, which is done by throwing an arm around a friend whom they meet and patting him heartily on the back. They prefer the easy-going, wait-a-while style of existence to the hurried, strenuous life of an American city. No people love leisure and the pursuit of pleasure more than our neighbours in the Mexican metropolis. They work during the morning hours, take a noon siesta, close up early in the afternoon and are ready for pleasure in the evening until a late hour.

In appearance the capital resembles Madrid more than any other city I have ever seen. The architecture is the Moorish-Spanish style, into which some Aztec modifications have been wrought by the new-world builders. The light, airy appearance of an American city is absent for there are no frame structures anywhere. The square, flat-roofed buildings, with walls thick enough to withstand any earthquake shock, are two or three stories in height and built round a patio, or courtyard, the centre of which is open to the sky. The old architects were not hampered by such paltry considerations as the price of lots, and so they built veritable palaces with wide corridors and rooms lofty and huge. Through many of these rooms[48] you might easily drive a carriage. There are parlours as large as public halls, and throughout all one notes the grandiose ideas of the race. The houses, of stone or brick covered with stucco, are built clear up to the sidewalk so that there is no tinge of green in front. The Mexican is not particular about the exterior of his home, but expends his thought and money on the open court within. The plainness of the outside is relieved only by the large gate, or door, which is also the carriage drive-way, and the neat little, iron-grated balconies on which the windows open from the upper stories.

THE PATIO OF AN OLD RESIDENCE

These balconies afford a convenient place for the women of the household to see what is passing on the street, and also for the señorita, or young lady, to watch the restless pacing to and fro of the love-stricken youth who is “playing bear” in front of the house. The great doorway, which is carefully barred and bolted at night, and strictly guarded by the porter during the day, is the only entrance to the patio, which, in the better class of homes, is adorned with pretty gardens, statuary and fountains. Many of them contain an open plunge bath. Through the wide windows one catches glimpses of fascinating interiors, and through the broad doorways the passer-by on the street gets many a[49] pretty view of the courtyards, and of these miniature gardens. One or two rows of living-apartments extend around and above the court, with broad corridors in front handsomely paved with tile, protected by balustrades and adorned with flowers and vines. Above, the red tiles of the roof add a little additional colour to the scene. There are no cellars nor chimneys. The latter were never introduced because of the mildness of the climate. In the courts protected from the winds, the people keep on the sunny side when it is cool and hide from the same orb when it is hot. Charcoal fires are used for cooking and heat when it becomes necessary. Cellars are made impossible because of the marshy nature of the soil.

It will be recalled that Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, has been called the New World Venice, whose streets were once canals. It must have been a gay and picturesque scene when the fair surface of its waters was resplendent with shining cities and flowering islets. The waters have since receded until Lake Texcoco, at its nearest point, is three miles distant. Mexico is now a more prosaic city of streets and cross-streets which extend from north to south and from east to west. Some of the principal thoroughfares are broad,[50] paved with asphalt and well kept; but many are quite narrow, and especially is this true of the streets called lanes, though devoted to business. There is no exclusive residence section, except in the new additions, and many of the homes of the old families are found sandwiched in between stores. It is a difficult matter to become familiar with the names of the streets, for they are more than nine hundred in number, and a street generally has a different name for each block. If several blocks have the same name, as, for instance, Calle de San Francisco, one of the finest streets, and on or near which are some of the largest hotels, finest stores and richest private dwellings, then it is First San Francisco, Second San Francisco, etc.

A few years ago the streets were re-named. All the streets extending east and west were called avenidas, and the north and south streets calles, each continuous thoroughfare being given but one name. The people, however, in this land of legend and tradition, clung so tenaciously to the former designations that they have practically been restored. Some of the old names of streets commemorated historical events, as, for instance, the Street of the Cinco de Mayo, which is in remembrance of the victory[51] of the Mexicans over the French at Puebla in 1862. Others are named in honour of men noted in the history of Mexico. Many religious terms appear, such as the street of Jesus, Sanctified Virgin, Holy Ghost, Sepulchres of the Holy Sabbath, and the like. Others owe their names to some incident or legend, which is both interesting and mysterious. Of the latter class may be mentioned the Street of the Sad Indian, Lane of Pass if You Can, Street of the Lost Child, Street of the Wood Owls, Lane of the Rat, Bridge of the Raven and Street of the Walking Priest. The Street of the Coffin Makers is now known as the Street of Death. It is a thoroughfare of one block, and is one of the few streets that still preserves its ancient caste, for it is devoted exclusively to the makers of coffins. All of the coffins are made by hand. It is a gloomy street and there are cleaner spots on the face of the earth.

Mexico is a very cosmopolitan city. Its three hundred and seventy-five thousand inhabitants include representatives from nearly every nation of the earth. The Indians are vastly in the majority, and they are the pure and original Mexicans. The Creoles, who are descendants of Europeans, generally Spanish, call themselves the Mexicans and rank second in[52] number. They form the real aristocratic body from whom come the representative Mexicans. They are not all dark, but a blonde is a rare specimen. Most of them have an olive-brown colour, thus showing the mixture of Indian blood, for in early days it was not considered a mesalliance for even a Spanish officer of high rank to marry an Aztec maiden of the better class.

The old families cling tenaciously to the great estates, or haciendas, many of which have remained intact for centuries. Quite a number can even trace their estates back to the original grants from the king of Spain. Many of these hacendados, or landed proprietors, enjoy princely incomes from their lands, and nearly all of them own residences in the capital. They maintain elaborate establishments and keep four times as many servants as would be found in an American house.

The average Mexican does not care for business. Neither is he an inventor or originator, for he is content to live as his ancestors have lived. Nearly all lines of commerce and industry are in the hands of foreigners. The Germans monopolize the hardware trade; the French conduct nearly all the dry goods stores; the Spaniards are the country’s grocers; and[53] the Americans and English control the railroad, electric and mining industries. All these interests centre in the City of Mexico. Railroads are not very numerous until you approach the Valley of Mexico where they converge from all directions. The hum of industry is apparent here as nowhere else in the whole republic. The Mexicans boast of their capital, but they often forget the debt they owe to foreigners, for all the modern improvements have been installed by alien races and outside capital. It is another foreign invasion but with a pacific mission. The American colony alone in that city numbers more than six thousand persons, and the number is constantly increasing. Hatred of the American has almost disappeared, and the incomers are cordially welcomed. There are two flourishing clubs around which the social life of the expatriated Americans centre.

The society of the capital, and indeed of the whole country, is very diverse. What might be said of one class would not apply to another. The differences of dress and customs alone make known the heterogeneousness of the population. They all use the same language and all classes are brought together on a common level in their religion. No other nation has ever[54] made such complete conquests as Spain. She not only subjugated the lands but forced her language, as well as religion, upon the conquered races. The English have succeeded in extending their sway over a large part of the world, but in no instance have they been able to accomplish these two results with the native population. The priests of Spain went hand in hand with the conquistadores, and, within a few generations after the conquest of Mexico by Cortez, the Spanish language was universally used and the Indians were at least nominal Catholics.

The climate of the City of Mexico is delightful. It is neither hot nor cold. It is too far south to be cold and the altitude, seven thousand, four hundred and thirty-four feet above the level of the sea, is too great to be hot. The temperature usually ranges from sixty-five to eighty-five, but sometimes goes as high as ninety, and as low as thirty-five, and frosts occasionally are experienced. The mornings and evenings are cool and at midday it is always hot. There is a great difference in the temperature between the sunny and shady side of the street. Only dogs and Americans take the sunny side, the Mexicans say. The rainy and dry seasons occur with great regularity, the[55] former lasting from May to October. It is the best season in the year although most visitors go there in winter. The rains always occur in the afternoon and usually cease before dark. At this time, too, all nature takes on a beautiful shade of green which replaces the rather dull landscape of the dry season. There is also a brisk, electric condition of the atmosphere that is decidedly exhilarating and a good tonic.

This mildness of climate has greatly influenced the life of the capital. The streets, except during the noon siesta, are full of people at all times. To judge from the crowds, one might think the capital a city of a million people. In the morning the women go to mass garbed in black, generally wearing a black shawl over the head. Occasionally a black lace mantilla is seen half-concealing, half-exposing the olive-brown face, and bright, sparkling eyes of a señorita. Shoppers are out and business is active. The women of the wealthier classes sit in their carriages and have the goods brought out to them, or go to a private room where articles are exhibited by clerks. They think that it is unbecoming to stand at the counters, although the American plan of shopping is becoming quite popular in recent years.

About the middle of the afternoon the crowds[56] again appear, and a little later the streets begin to fill with carriages. Nowhere, not even in Paris, have I observed so many carriages as can be seen here on any pleasant afternoon. They form one continuous, slow-moving line of many miles. The procession moves out San Francisco Street through the Alameda, along the Paseo de la Reforma, and then into the beautiful park surrounding the Castle of Chapultepec which is set with great cypresses, said to antedate the conquest. The cavalcade winds around through the various drives at the base of the rock, along the shores of the lake, past the castle and back to the city. The carriages go out on one side and return on the other, leaving the central portion for riders. It is a sight that never wearies for one to sit on a bench and watch the motley throng of people driving, riding on horseback and promenading. An oriental exclusiveness is observed by ladies of the upper class who always ride in closed carriages. All kinds of vehicles are to be seen, from fine equipages with liveried drivers and footmen, to the poorest cab in the city with its disreputable driver and broken-down horses, fit only for the bull-ring.

There are many horsemen and the Mexicans are always excellent riders. Their horses are[57] Lilliputian in size but fast and enduring. The saddle, bridle and trappings are frequently gorgeous with their silver ornaments and immense stirrups fancifully worked and shaped. The rider is often a picture wonderful to behold from the heavy silver spurs which he wears, to the sombrero of brown or yellow felt with a brim ten to fifteen inches wide and a crown equally as high, the whole covered with heavy gilt cord formed into a sort of rope. Then there is the dude or fop, who is well named in Mexico. He is called a “lajartija” which means a “little lizard.” He used to dress in such close-fitting and stiff costumes that he had not much more freedom of motion than the stiff little lizard. Now he is the dandy who is generally seen standing on a public corner, wearing a French cutaway suit, American patent leather shoes and an English stovepipe hat, with his fingers closed over the indispensable cigarette.

In the evening the populace attend the theatre or some social function. Sunday is the day of all others for recreation, and, with the average inhabitant of Mexico, is one continuous and eternal round of pleasure. After morning service the entire day is devoted to pleasure. Band concerts are always given by the military[58] bands on the Plaza in the morning, in the Alameda early in the afternoon, and at Chapultepec about five o’clock. Then there is the bull-fight which occurs only on Sundays and holidays.

The average crowd in the City of Mexico is a good natured and peaceable one. The city Indian and his country cousin, the peon from the plantation, join the crowd on a feast day with their numerous progeny. They are not the pleasantest neighbours in the world for both have the odour of garlic and pulque and their baths are of the annual variety. That the little brown man is a peon is no fault of his. His uncleanliness is, in a measure, the result of centuries of neglect, and more particularly of a scarcity of water at his home. It is possible that if he had the water his condition would be just the same. Though he is poor and down-trodden, there is nothing of the anarchist about him. He is absolutely devoid of envy or malice; and withal his spirits are gay and he is as generous to his family or friends as his finances permit. The artificial refinements of modern civilization have not yet spoiled him, and there is a pleasant, even if malodorous, naturalness about him.

In no city do ancient and modern customs[59] come into such intimate contrast as in the City of Mexico. Nowhere is a greater mixture of races to be seen than here. There are many tribes of Indians speaking scores of dialects, and there are mestizos of various degrees of mixture with African, American and European blood. Types of four centuries can be seen in any group on one of the plazas. The Plaza Mayor is a great, imposing, central square of fourteen acres in the centre of the city, and on its walks all the types can be seen at their best. Men and women come into the city through the streets lighted by electricity, bearing immense loads on their heads and backs rather than use a wagon. Peddlers carry around jars of water for sale just as in the olden times. Indians, who are almost pure Aztecs, pass along, taking the middle of the street in Indian file. Well dressed men in black broadcloth suits and wearing silk hats go by. The women of the middle class add colour to the scene with the red and blue rebosas, sometimes covering the head, or tied across the chest and holding an infant at the back. Nearly all the passers-by show in their colour that they can claim kinship with the hosts of Montezuma. The general effect is kaleidoscopic but entertaining. The great cathedral on the north side[60] of the Plaza is the one place where all are brought together and class distinction obliterated. Visit the cathedral any day and you may see an Indian with his pack on his back side by side with a young woman who may inherit a dozen titles. There are no select, high-priced, aristocratic pews for rent, but all meet by a common genuflection before the sacred altars. The poor Indian may not understand all the pomp and ceremony, the music of the vested choirs, or the solemn chanting by the priests, but it fills a deep want in his nature and he is satisfied.