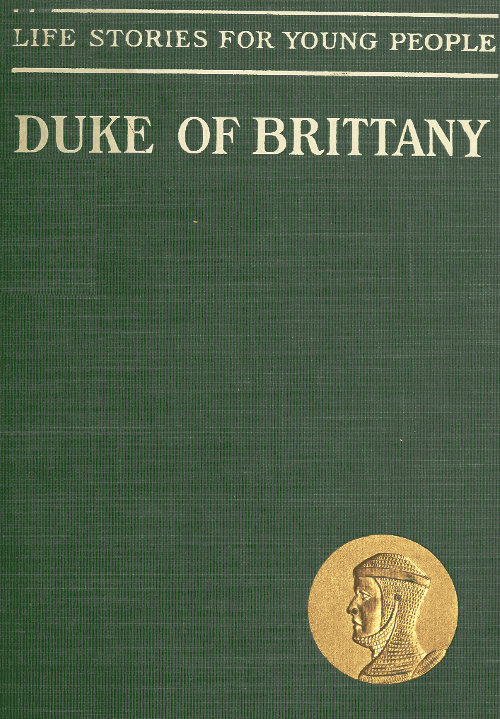

Arthur’s rescue of the Jew (Page 51)

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Henriette Jeanrenaud

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” etc.

WITH TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1908

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1908

Published August 22, 1908

The University Press, Cambridge, U. S. A.

“The Duke of Brittany” is the story of the brief but eventful career of Arthur, son of Geoffrey Plantagenet and Constance of Brittany. Geoffrey was the fourth son of Henry the Second of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Guienne. Upon the death of his brother Henry, Richard, surnamed the Lion-hearted, became the heir apparent and succeeded to the throne after the death of his father in 1189. Richard shortly afterward became one of the leaders of the Third Crusade, which ended disastrously. After being taken prisoner in Austria by Duke Leopold he was ransomed and returned to England, where he suppressed the rebellion of his brother John. He then invaded France to punish Philip the Second, John’s ally, but was mortally wounded while besieging the fortress of Chalus, near Limoges. On Richard’s death, John, surnamed Lackland, ascended the throne, ignoring the rightful claim of Duke Arthur, Geoffrey’s son. Almost his first act was the murder of Arthur, who, with the encouragement of Philip Augustus of France, was prepared to defend his claim as the son of an elder brother. By John’s foul deed England lost its French fiefs.

The story turns upon the events in Arthur’s short life, his young days in Brittany, the violent death of his father, the relations of his mother to Philip of France, the boy’s love for his uncle Richard, his service in the field with Philip, his espousal to Marie of France, the war with John, his capture and assassination by the latter. The incidental characters are the Jew Abraham of Paris, Earl Salisbury, the valiant knight Höel of Mordant and his son Alan, between whom and Arthur existed a beautiful friendship. Many of the scenes are of thrilling dramatic interest, particularly the one in which the crafty and malicious Queen Eleanor refrained from blinding Arthur only because of his resemblance to his father, her favorite son; the assassination on shipboard; and the accusation of King John by Alan. Some of the historical data in the story are not accurate in minor details, but in general the tale follows the versions of the historical authorities. It is a fascinating picture of two lovable, high-minded, chivalrous youths, worthy the study of the youths of to-day.

G. P. U.

Chicago, 1908.

Near the close of the twelfth century a hunting-castle stood in the northern part of Brittany, in the midst of dense forests. It belonged to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Duke of Brittany[1], and his banner was flying from one of its towers, for the master had come for a great hunt. His wife Constance and her ladies accompanied him, though he was very reluctant to have her come into that wild region; but Constance would not be separated from her husband, and feared neither the solitude of the gloomy forest nor the fierce storms which occasionally swept over them from the adjacent shores. Brittany was her home. Her father, the last of the independent dukes, ruled the eastern part of it, and she brought it as her heritage to her husband, son of King Henry the Second of England[2]. West Brittany, which was English, had come into Geoffrey’s possession, before this time, from his father, and the two divisions were consolidated by him into one dukedom. Constance loved the country, and gladly visited this remote hunting-castle.

On the second evening after her arrival, Constance found herself alone with her attendants, for the Duke and the nobles, who were taking part in the chase, had ridden to the forest at early morning light with their retinues.

There were but few guests, for many an old house had lost its brave master, and many a strong castle stood empty. Many of the stoutest vassals had been drafted into the service of the English king, and others had fallen in the French wars. The country was impoverished and well-nigh deserted; the Duke was no longer powerful enough to protect it from marauding hordes and the ravages of wild animals. He had come at this time not only to indulge in the pleasures of the chase, but to restrain these pillagers as far as possible.

The Duchess and her ladies impatiently paced the high stone terrace of the castle, stopping now and then to scan the forest, in whose gloom the road by which the hunters entered was soon lost. As the sun disappeared behind the dense mass of trees the Duchess eagerly listened for the first peal of the horns announcing the return. But as the sun sank still lower and the darkness grew more intense, no peal sounded from the forest. The wind rustled the banner above her, then suddenly ceased, and an ominous silence followed. After a few minutes the neigh of a horse was heard in the distance.

“Do you hear that?” joyfully exclaimed the Duchess to her ladies. “It is thus my husband’s faithful steed always announces its approach to the castle. We shall soon hear the signal of the horn, summoning us to make ready for them. Come, let us go to meet the Duke in the hall.”

Followed by her ladies, who cast parting and anxious glances at the forest, the Duchess hastened inside, ascended the steep, winding stairs, and entered the large reception hall, brilliantly illuminated by torches, where the remaining inmates of the castle assembled, among them the chaplain in his black vestments. Uttering the greeting, “Peace be with you,” he took his place near the Duchess, the others arranging themselves in a circle around the walls. The warder, with his heavy bunch of keys in his leathern girdle, went out to the courtyard, prepared to open the outer gate, which was protected by the drawbridge, when the hunting-party arrived.

At that instant the horn signal was sounded; but what a mournful tone they heard! All were astonished, and anxiously looked at the Duchess, who advanced toward the door with pallid face. Once again the horn sounded a piercingly mournful call, and through the outer gate, which the warder had opened, they saw the party advancing.

A squire was in the advance, leading the Duke’s horse by the bridle. When she saw the horse was riderless, the Duchess pressed her hand to her heart but retained her composure; for, if her husband was injured and needed her care, she must be courageous. The next to enter the courtyard were the Duke’s followers. With slow and measured step they carried a covered bier, and silently placed it in the entrance to the hall. Behind them pressed knights and hunters, on foot and horse, and much confusion prevailed.

Constance seemed to pay no heed to them. She went to the bier and lifted the covering. There she saw Geoffrey, her husband—dead![3]

The handsome, noble features in their setting of luxuriant blond hair, so lately lit up with life and animation, were now rigid in the chill of death. Long Constance stood immovable, with the edge of the covering in her uplifted hand, and gazed with horror-stricken eyes, as if transformed to stone.

The chaplain tenderly approached her. “Gracious Princess, permit us to conduct you to your apartments.”

His words broke the silence. She uttered an exclamation of despair and with a shriek fell fainting into the arms of her ladies. The chaplain had her quickly removed to her chamber and cared for, and then returned to the hall. The knights had given over their weapons and horses to their servants, and were assembled there. A low murmur of hushed voices, mingled with sounds of mourning, filled the great room.

“Speak, Sir Knight,” the chaplain implored of Höel of Mordant, Geoffrey’s oldest vassal and friend, who stood by the bier with bowed head, leaning upon his sword. “I know not yet how this dreadful tragedy occurred. I only realize that the Duke, whom we saw but a few hours ago in the flower of his health and strength, is dead.”

Several voices were raised to relate the circumstances. The hunters had had an enjoyable time until noon, and had slain many stags and boars, but one huge boar, which the Duke discovered at the very outset, managed for a long time to elude his spear. The hounds kept upon its track, and, guided by their baying, he at last overtook it and hurled his spear. He only wounded it slightly, whereupon the infuriated beast turned upon the Duke’s horse and attacked it with its tusks. At this instant several knights came up, and saw the Duke draw his hunting-knife, intending to stab the boar in the neck; but at that moment his horse, overcome by pain and fear, reared and fell, and in the fall the knife pierced the Duke’s side. He lay weltering in his blood as his friends gathered around him, and only once he opened his eyes. They rested upon Knight Höel, who knelt by his side. The sorrowful glance of appeal in Geoffrey’s dimming eyes deeply affected the knight. Raising his head he thus spoke: “Whatever it may be, my Prince and brother-in-arms, that thou would’st ask, trust me it shall be done. I will devote my loyal service to the end of my life to thy memory, and hold it as a sacred trust.” The Duke closed his eyes. A sigh escaped him, and his face was illuminated with joyous satisfaction. Then they carried his body home.

“And now,” said Höel, “we will execute the last service for our master. Chaplain, remove the body to the chapel and perform the sacred rites.” Then, turning to two of the knights, he said: “And you, my friends, keep the death-watch at the bier. I cannot yet master the sorrow which has overcome me. I must have time for reflection, for my responsibility to the ducal house is great. See that the gates are secure, and station sentinels. In the morning all must assemble in the hall and have their steeds in readiness, for messengers must be sent in all directions. Now, betake yourselves to rest, if you can find it,” he ended with a sigh.

Suddenly cries were heard from above, and some one said, “The Duchess is dying.”

“In the name of all the saints at once,” groaned the knight, “see to it that she has help!”

The chaplain obeyed, but soon returned with the announcement, “Our gracious lady has recovered and does not need me.” Thereupon he motioned to the squires to take the bier into the chapel, and followed it. Through the open door the priest was seen as he advanced to the altar, which was faintly lit by tapers. In a low voice he began the service. The mourners remained kneeling for a time during the sacred ceremony, then gradually withdrew, and only the murmur of prayer was heard. Priest and watchers were alone with the dead.

Armed, and with helmet in hand, Höel entered the hall at early dawn, only to find it deserted. The chapel too was closed, for the chaplain had gone, and only the knights keeping the death-watch remained.

A page brought the knight a warm drink. He drained the cup, and as he turned to hand it back to him he saw the priest descending the stairs which led to the apartments of the Duchess.

“Have you seen our gracious lady? Then arrange for my admission also,” Höel said to him.

“Come outside with me,” replied the chaplain, much agitated, “and hear what I have to say, not here where we are so near the dead, but under God’s sky.”

Overcome with astonishment, Höel followed the chaplain as he strode forward in haste to the courtyard. As they went, a loud trumpet-blast sounded jubilantly from the battlements.

“Is the warder out of his senses? What means this fanfare in the house of the dead?” exclaimed Höel indignantly. “And what does that mean also? The black flag has been lowered on the watch-tower, and the banner with the arms of the Plantagenets floats in its place.”

“It means, noble knight,” replied the chaplain, “that Brittany has a new Duke,—our Lady Constance has a son.”[4]

The knight’s eyes glistened with delight, but it was only for an instant. With a sigh he gently said: “Poor Geoffrey! Unfortunate child!” Then he stood for a time in deep thought. “All the same,” he said at last, recovering himself, “messengers must carry the double news to all the castles and cities. The Council of the dead Duke must send ambassadors to the courts of England and France.”

“As King Henry is engaged in a campaign against Scotland and Queen Eleanor passes away the time among her castles in Guienne, there does not seem to be urgent need of haste,” said the chaplain.

“You are wrong. They must be informed as speedily as possible,” replied the knight. As he was in the act of mounting his steed, which a squire had brought, a page rushed up and summoned him to the Duchess.

The knight followed the messenger to an upper room, where one of the maids promptly met him, and conducted him to a large apartment, against the rear wall of which the Duchess’s bed stood under a gilded canopy. The curtains were partly drawn back, and in the half darkness he saw the face of the Duchess among the silken pillows. Höel knelt and awaited her commands. She motioned him to rise, and said, “Show him the child, Joconde.”

The nurse approached, and lifted the veil from the little white bundle she was carrying, so that he might see the child. As he stooped to look at him, the little one opened its eyes and uttered a faint cry. The plaintive tone pierced Höel’s heart. He laid his hand upon the child’s head and said with deep emotion, “Accept my homage, son of my brave lord and friend.”

The Duchess bade Joconde retire, and then said, “May all, worthy knight, like yourself, pay homage to Duke Arthur of Brittany, for it was this name my husband selected for his first son.” She gave way to her emotions for a moment, and then said with firm voice:

“Take this signet ring of my husband’s, show it to the members of the Council at Rennes,[5] and bid them execute my commands. The citizens of every city shall assemble; and to them and to every country it shall be proclaimed that Duchess Constance of Brittany will maintain the ducal authority, and that during the minority of her son she will rule all the possessions of the deceased Duke Geoffrey Plantagenet, with the help of God and the nobles of Brittany. Send a messenger also to the King of England and inform him of the death of his son and the birth of a grandson. But, above all, send a prudent man with a letter to King Philip Augustus at Paris.[6] Assure the King of our feudal loyalty as a vassal of France, and tell him we shall render him our usual service in time of peace or war, and pay the customary tribute. In consideration of this he is to assist us in case of necessity against any enemy of our country or of the young Duke. Have the letter drawn up in temperate and friendly tone.”

“It shall be done, my lady,” replied Höel; “and what are your wishes as to the funeral of the Duke?”

“He shall be buried in the Cathedral at Rennes, and the chaplain must see that everything necessary is done. Now go, and God preserve you. May you quickly return for our protection.” She leaned back, wearied. The curtains were closed, and the knight left the apartment with a feeling of relief. When he reached the courtyard he summoned his people and the chaplain, who inquired what commissions the Duchess had given him. He answered curtly, “Chaplain, he who says women are weak and timid has never known the Duchess Constance.”

“But, tell me—”

“Only this,” said Höel, with his hand upon his horse’s bridle, “France is the watchword. She said scarcely a word about England.”

Upon his arrival in Rennes, the ancient capital, Höel found the citizens greatly excited over the rumor of the Duke’s death. As his little band rode through the streets, the people came from their houses and workshops, and a great multitude gathered round the castle. They had hardly heard the news of his death before it was followed by joyful intelligence, which turned sorrow into rejoicing. Enthusiastic shouts of “Hail to the new-born Duke! Long live Arthur Plantagenet!” rang out on all sides.

The Council and leading ecclesiastics were assembled when Höel entered the hall. After exhibiting the ring and executing his commission, he described to them the occurrence of the fatal day, but made no reply to their eager questioning as to the future.

“What is to be done, Knight Mordant?” they asked. “Brittany will remain loyal to the Duke; but will King Henry of England protect us? Philip Augustus of France will certainly seek to extend his possessions.”

“Let us do our duty,” replied Höel. “We may accomplish great things if we remain united.”

After a short rest Höel departed, taking a different route to the hunting-castle, in order to visit Castle Mordant and see his wife and little son.

He found them very happy and without any knowledge of what had happened. In a few words he described the condition of the Duchess to his wife. “And now, Bertha,” he added, “prepare yourself and little Alan to ride with me. I shall not feel easy about the Duchess and the child until I know that you are with them.”

Bertha in surprise drew Alan to her side. “Would you take me to the Duchess without knowing whether I shall be welcome? The Lady Constance has not been accustomed to children for years, and may not like youthful mischief.”

“If not for her sake, Bertha, do it for the child’s sake. Suppose a faithless nurse should place him under the control of the grandmother, Queen Eleanor of England, and he should meet with the same fate as her child, the little girl. What happened to her, do you ask? They say she was put in a convent. If Geoffrey’s son were to be placed in a monastery, I believe his father would not rest in his grave.”

“I will go,” assented Bertha. “Let the child be intrusted to me, and I will care for it as if it were my own. His lot, in any event, will be hard enough, for rulers care little for the rights of minors.”

“Oh, that Geoffrey had only been on good terms with his father!” exclaimed Höel. “His participation in the rebellion into which his mother and brothers urged him estranged his father’s heart.”

“But they were reconciled afterwards.”

“Yes, but his father’s confidence was not restored, and the others have been subjected to every kind of injustice. What lies Eleanor told about John, her youngest son! His father does not trust him, and has given him no possessions. To save himself from impoverishment he is casting covetous glances toward Brittany.”[7]

“Her father’s share to half the country cannot be taken away from her,” said Bertha.

“Not by right; but might knows no right. Perhaps, however, the jealousy between France and England, whose sovereigns will never permit their beautiful maritime provinces to go to another, may save us.”

“What is the name of the little Duke?” interrupted Alan, who had climbed upon his father’s knee.

“He is called Arthur.”

“Will he play with me?”

“Not yet, but perhaps later.”

After speedy preparations they departed; they reached the hunting-castle at evening, where they found the Duchess doing well. Bertha’s fears proved groundless. She was heartily welcomed by Constance, who was at that moment specially grateful for any expression of sympathy. The Duchess well knew that she could not place her son in better hands, and for the first time she felt free from anxiety when Bertha cradled him in her faithful arms. She cared alike for the two children; and Alan, far from being jealous because his mother shared her love between them, displayed the utmost tenderness to the little Duke.

Höel was now free to devote himself to the sad duty of burying the dead. A great concourse of knights, citizens, and ecclesiastics accompanied the body of the Duke to Rennes in an imposing procession, headed by Höel and the chaplain. All along the road they passed sorrowing people. Serious anxiety for the future filled all hearts, and sincere mourning followed the Duke to his grave.

Shortly thereafter the Duchess and her nearest attendants betook themselves to the capital, and were greeted with loyal homage. She met with no protests or opposition. Her regency was indorsed, and all the rights which Geoffrey had enjoyed in the English provinces were conceded. Höel remained steadfastly by the side of the Duchess and devoted himself exclusively to her service. His example, and his tender consideration for her, worked for her advantage, as it induced many who were wavering at first to join in making the recognition of her authority unanimous.

As the Duchess was obliged to devote the most of her time to affairs of state, the child was tenderly cared for by Bertha. The quiet of the little court was broken by the festivities attending the approaching christening of the Duke. Tournaments and sports were arranged, and the friends and adherents of the Duchess were summoned to Rennes. She had received no tidings from the relatives of her husband, whereas King Philip Augustus of France had promised to be represented by one of his knights, whose arrival was eagerly awaited.

At last the French gentlemen appeared at the gate of the castle in imposing array—knights in glistening armor, squires and servants also armed. Count von Gragny, a famous soldier and well-known to Höel on many a battle-field, came as the King’s representative. The strangers were escorted to their quarters, and after a short rest Count Gragny exchanged his armor for court dress to wait upon the Duchess. With his little retinue he rode through the narrow streets of the city to the castle, where the chamberlain conducted him to her presence.

Constance received upon a dais in the centre of the room, surrounded by her ladies, and bowed a gracious welcome to the Count, who knelt and delivered the greeting of his King.

“I am delighted, noble Count,” Constance began, “that the King has granted my wish and is willing to be the godfather of the Duke.”

“The King has shown you further favor, Lady Duchess, and has intrusted me with a message which is for your private ear,” replied the Count.

The Duchess, surprised, motioned her ladies to withdraw. “Speak,” she eagerly exclaimed, when they were alone.

“The King of France, in consideration of your unprotected situation and the dangers which threaten the heir of Duke Geoffrey—”

“Pardon me,” interrupted Constance, “we do not feel that we are unprotected. Our vassals are faithful, and the people are loyal.”

“Yet as dangers may easily arise, noble lady, when you least expect them, King Philip offers to undertake the guardianship of your son.”

Constance was alarmed, but retained her composure, and asked: “Would not this provoke danger? It is the duty of the nearest paternal relatives, the King of England and his princes, to take the place of father to my son, and they may not yield that right.”

“Are you sure they are willing to exercise it, Lady Duchess? and have you sufficient confidence in them to intrust your child to their care? Will they unqualifiedly recognize him as the Duke? King Henry is far over the frontiers of Scotland and his sons are not on the best of terms with you.”

“Richard is noble and just. He is the eldest, and is under obligation to his dead brother, Geoffrey,” replied Constance.

“Do not depend upon him. He is never in one place long enough to become attached to any one. I advise you to accept the King’s offer.”

“I will consider it, Count,” replied the Duchess, rising. “For the next few days, meanwhile, you are my guest. We will let business rest during the festivities, but will confer with you again on this matter before you return to Paris.”

The Count bowed and left the Duchess, who remained for some time absorbed in thought. At last she called Bertha, who was accustomed to bring the Prince to his mother about that hour, and she at once entered, carrying the child in her arms. The Duchess rushed up to her, took the child, and tenderly kissed him. “I may enjoy my sweet one only a moment to-day, Bertha,” she exclaimed. “Is it not glorious that God has given me such a charming gift of love? Surely fate should be kind to him, but, alas, clouds are gathering on the horizon of his life, and I am left alone to protect him. Now, Bertha, take my darling away, for Knight Höel comes to speak with me.”

Höel was very anxious, for he feared, after the long interview with the Count, that difficulties had arisen. Constance began at once communicating to him what had been proposed, “Can you divine what King Philip Augustus has requested of me?”

“Requested, or demanded?” asked Höel.

“Both, only the demand was concealed. He wishes to take the guardianship of the Duke of Brittany.”

“Ha! crafty as ever! Were his proposal disinterested, it would be well. Still, Philip has the power to protect you.”

“But against whom? We are living in peace, and I must first know what to expect from England.”

“May I know what reply you made to the Count?”

“None, as yet. I asked time for consideration. See to it, therefore, that the French gentlemen have a cordial reception, and at the christening to-morrow the representative of the King shall be honored as far as is in our power.”

With this the Duchess closed the interview, and Höel repaired to his guests to ascertain their wishes and make their visit as pleasant as possible.

The little Duke was christened Arthur, as his father had decided. After the ceremony was concluded and he had been taken back to his chamber and consigned to Bertha’s care, the Duchess summoned all her guests, as well as her knights and ecclesiastics, to a feast in the great hall. Constance was seated at the head of the table, under a canopy. The strangers, with whom she graciously conversed in French, sat near her, while the guests at the lower end of the table spoke in the native Breton dialect. Quiet at first, they gradually grew more animated as great flagons of wine were repeatedly filled and drained. Owing to the confusion in the hall they failed to hear the sound of horses’ hoofs outside the castle, and the blast of a horn was the first announcement they had of the arrival of new guests. The chamberlain entered the hall and whispered to the Duchess, who thereupon rose, and with a wave of her hand ordered silence. “We have unexpectedly been honored by the arrival of a noble visitor,” said she. “It is Queen Eleanor. She is at the castle with her retinue. Let us hasten to receive them with the honors due to her.”

Constance advanced to the entrance of the hall, followed by her nobles, a part of the guests remaining at table. Scarcely had she reached it when the Queen met her at the head of several knights.

With stately dignity Constance courtesied her greeting and spoke: “Welcome, illustrious Queen! and excuse us for not going out to receive you. We are surprised, having received no intimation of this visit, although we sent messengers with invitations.”

The Queen stretched out her hand to Constance and kissed her on the forehead. “We have changed the route of the journey we had planned to greet you, daughter-in-law, and are truly delighted to find you so strong and well. We were ready to sympathize with you in your affliction, but it does not appear to be necessary.”

“Honored mother of my dead husband, I shall never cease to mourn for Geoffrey; but you very well know that princesses have no time to abandon themselves to grief. But come and participate in our feast. You will find worthy guests here, messengers from the King of France.”

“Ha!” exclaimed the astonished Queen, as she recognized Count Gragny, who with the others advanced and bowed low. “Have you settled matters so far as to throw yourself already into the arms of Philip Augustus, even before you have taken the trouble to ascertain the policy of the King of England?”

“Although I have received no answer to my message to England,” said the Duchess, “I doubt not that King Henry will approve my action in securing the good-will of our powerful neighbor and seeking his protection for my son, the Duke of Brittany.”

“Let me see the child,” replied Eleanor. As she noticed Constance looking inquiringly at Höel, she added: “Why do you hesitate? Have you any reason for concealing him from me?”

Höel went at once to notify Bertha, and when the Queen entered the chamber with Count Gragny and several other knights, all gathered about the cradle in which the child was lying. Eleanor gave one glance at the little Duke and then turned again to Constance. “I advise you to give up your game. I shall never recognize this boy as Geoffrey’s heir. Content yourself with your paternal possessions in Brittany, which I shall never enter again.”

“What do you mean, Your Majesty?” exclaimed Constance, with increasing emotion.

“I mean that the heir came very suddenly, and when he was greatly needed,” said Eleanor. “Who knows in what hut he was born and found?”

“This is monstrous!” interrupted Constance. “How dare you impute such a disgraceful thing to me, and insult me in my most sacred relations? Go! Only one who can invent such a story is capable of such action. You have a wicked heart!”

“Enough,” said the Queen. “See to it that you and your child do not come in my way, otherwise woe to him and to you.” As she said this she made a threatening gesture with her hand at the child.

Little Alan, who had been standing by his mother’s side, darted forward and, seizing the Queen’s arm, cried out in his shrill childish voice, “Don’t you touch the Duke!”

The Queen regarded Alan with astonishment, and said with a sneer: “So! You have taught young and old to call him Duke without regard to the policy of others!”

“The united dukedom belongs to us as rightfully as does Guienne, which you inherited from your father, to you,” said Constance haughtily. “But now, Your Majesty, let us have peace. Remember, you are our guest, and as such we shall treat you with due honor.” The Duchess stepped to the door, and stood there until Eleanor had passed, then followed with her knights.

“What a woman!” whispered Count Gragny to Höel, who quietly shrugged his shoulders. He kept his eyes bent upon the Queen, as he suspected she might have communication with those near the Duchess, for he feared her wiles. Eleanor took very little part in the banquet, and shortly retired with her attendants, after a brief leave-taking.

Those remaining in the hall regarded each other in silence, but Count Gragny could not long endure the situation. He spoke out: “The Queen came like the bad fairy who always appears unexpectedly at christenings. Fortunately, she left no evil gift behind.”

“Yet, noble Count,” replied Höel, “she has left us anxiety.”

“Let us drown all thoughts of troublesome questions with mirth and wine,” exclaimed the Count, raising his glass. “Your Ladyship, I drink to the health of Duke Arthur.”

Constance gracefully thanked him for the honor, and raised her glass to her lips. After that she announced the close of the feast and dismissed the guests.

She hastened at once to her child. She knelt down by his cradle and looked for a long time at the handsome little one lying in quiet slumber, watched his gentle breathing, and admired his rosy cheeks. Alan stood at the head of the cradle and kept watch over his Duke. With a sad smile Constance rose, took Bertha’s hand, and left the chamber.

Later in the evening the Duchess, Höel, and her counsellors prepared a reply to King Philip’s proposals. It had already been demonstrated by the Queen’s conduct how little they could expect from her husband’s family; for although as wife and mother Eleanor neither loved nor respected King Henry and his sons, she understood how to gain her own ends and embitter the feelings of others. Could affection for the child be expected of them when even his own grandmother would not acknowledge him? After due consideration it was decided to accept the guardianship offered by Philip Augustus on condition that the King of England, on his return from the wars, agreed to it.

On the following day Constance gave her reply to Count Gragny, who expressed his delight, for he knew that the King would be pleased with the prompt and successful manner in which he had executed the commission.

“My King ordered me,” he said, “to make arrangements for your safety at once. He will send you all the troops you need.”

“We are not at war,” replied Constance, “and consequently do not need help.”

“Now that Eleanor has been here, Princess, do not expect that peace will be lasting. The help offered to-day may be too far away in time of danger to rescue your son.”

Constance was deeply impressed by his importunity, and turned to Höel, saying: “You know best our means of defence. Do you think them sufficient?”

“The militia will not hesitate to take the field for you,” replied the knight, “but only so long as war may last. Paid troops will remain all the time in your service, but of course they will be a burden upon the country.”

“Only a small number will be sent,” said the Count. “That is the King’s own stipulation.”

Constance was forced to accept, but with a sad heart, and dismissed the Count, who at once started for home with his attendants. The merrymaking arranged by the Count continued in Rennes, and the Duchess took part in it with apparent pleasure. But, as often as she could, she visited the room where Arthur played upon Bertha’s lap and crowed and laughed in play with Alan. She pressed her darling to her heart and sighed, “It is all for you, my son, all for you.”

Not long after these events Philip’s troops marched into Brittany, where they met with a quiet reception; but when they attempted to establish themselves in Normandy, they encountered violent resistance. The powerful barons there had made a complete surrender to the English government. They had accepted Geoffrey as its representative and had submitted to him, but they would not recognize Constance, for before her departure to England Eleanor had won them over to her side. Their followers were well armed, and stoutly resisted the French troops. In the numerous encounters which occurred the interests of the Duke of Brittany were no longer considered. The stake was the mastery of England or of France, and one or the other side alternately gained the upper hand.

It was still quiet in Brittany, and in Constance’s vicinity Höel and his men kept good watch. Longingly and often the Duchess gazed at the child in her arms and wished that he could soon be a man to fight with sword in hand for her and her rights. Thus they were living in apparent security at the castle in Rennes, but really in continual fear of approaching dangers. The times were troublous, and the world was full of disquiet, but Arthur passed his days pleasantly, in an atmosphere of love. Life was all smiles for him. Under Bertha’s care and Höel’s devotion he became both gentle and courageous, and as he grew stronger nothing delighted him more than rivalry with Alan in all knightly practices. The latter, older and stronger, was not only attached to the young Duke by friendship, but by duty and devotion, and thus became both his companion and protector. They were inseparable, and shared everything in common. They roamed the woods and fields together with all the joyous enthusiasm of youth, but their greatest longing was to perform heroic feats. They were much more delighted to listen to Höel as he told them of his adventures and exploits at arms than to the chaplain, who was their instructor. With rapt attention they heard the story of how Höel and Duke Geoffrey rode together to Normandy and other provinces, overcame the haughty barons, stormed their strong castles, and sent them to England to pay fresh homage to the King. Arthur longed to be such a hero, and his dearest wish was to assist his mother in the restoration of the ancient authority. Combining boldness and gentleness, he was specially fitted to rule, and it was his greatest pride that he was entitled to the position of ruler by birth.

Arthur was in his tenth year when the report reached them that King Henry’s sons, incited by Eleanor, had conspired to prevent his return from Scotland. Unexpectedly, however, he suddenly appeared in England and frustrated their plot. The news disquieted Constance so greatly that she sent Höel for information. He had been absent several days, and his return was now eagerly awaited.

One evening the Duchess was looking from her window, which commanded an extended view of the city and its vicinity. Fatigued with riding and hunting, Arthur had sought his mother, and was resting his head upon her shoulder. She turned to him and stroked his heated brow. Bertha and Alan were also present, and the room was very quiet. Suddenly Bertha stepped to the window and exclaimed, “There comes my husband with a stranger.” The two rapidly drew near, and dismounted in the castle-yard, whence, seeing the ladies at the window, Höel came to their apartment. Bertha and the boys met him in the anteroom, at the door of which stood the Duchess. “What news do you bring?” she asked.

“Bad news,” replied Höel. “King Henry is dead.”[8]

The Duchess silently motioned to the knight to enter, and seated herself. After Bertha had taken the boys away, Höel began: “The King died of a broken heart, so the people say. He could not endure the thought that the Queen had plotted his overthrow.”

“Horrible!—and the Princes?”

“Richard threw himself at his father’s feet and begged forgiveness. Prince John, on the other hand, hypocritically sought to clear himself of guilt. But the King knew only too well. ‘All three sons,’[9] he groaned, and fell unconscious.”

Constance started, and Höel was silent. Yes, the third one was Geoffrey.

“And did he die at once? Did he leave no instructions concerning the kingdom? Had he no thought for Geoffrey’s son?” asked the Duchess.

“They say he longed for his grandson and mourned because he had not been able to see him. He drew up his will and placed it in the keeping of the Lord High Chancellor. Then he turned his thoughts to divine things, took the sacrament, and passed away.”

Constance was silent for some time, then asked, “And does any one know the contents of the will?”

“It is sealed up in the royal exchequer and can be opened only in case the Prince—no, King Richard—shall die childless. Only the confidential witnesses know its contents,” said Höel.

“King Richard!” replied Constance. “God be thanked it is Richard who has come to the throne. He is noble and high-minded, and will protect us.”

“God grant it! Would that he could soon come to France and restore order.”

“Whence came the rider who brought the news?”

“From Rouen. English vessels have landed there, and brought Norman knights who were in the Scottish campaign. They will guard the country until he can come himself and take possession.”

“As soon as King Richard comes to Rouen, we will seek him there.”

“Meanwhile,” said Höel, “I will make ample preparations to insure your safety.”

“Is it not shameful,” said Constance indignantly, “that the Duchess of Brittany should be insecure in her own country?”

Höel was awaited in the hall by the two boys, who plied him with questions. The death of King Henry made a deep impression upon Arthur, who already realized that his fate had rested in his grandfather’s hands. For the first time also he realized the insecurity of human greatness, and when suddenly the bells tolled in the city’s church towers, and the castle chapel bell added its solemn peals, he was greatly overcome, and held fast to Alan’s hand.

It was a beautiful summer morning, and the hills and valleys of Brittany were flooded with sunlight. All Nature seemed exultant, and all living things were sharing her transports. The beauty of the fields and green woods concealed alike all traces of the last winter’s storms and the ravages so often occasioned by men when they sow the earth with fire and blood.

As if still more to enhance the beauty of the scene, a cavalcade was seen approaching from the adjacent wooded heights. The riders followed the winding road, now in groups, now singly, and sometimes were entirely hidden from view. Clear, ringing voices, joyous laughter, and now and then deep manly voices mingled with the neighing of horses. The travellers were the Duchess of Brittany, her son, and attendants. The seneschal rode in advance with two heralds, followed by Constance in a riding-habit of green silk, mounted upon a beautiful palfrey. Höel rode by her side, his fiery bay taking the lead whenever the road narrowed, to make room for the Duchess’s horse. Then came Duke Arthur and Alan on prancing black steeds. Arthur sat jauntily yet securely in his saddle, his slight figure being a trifling burden for the noble animal, which seemed to take pride in carrying him. He looked boyish yet distinguished. His unusual beauty was a sufficient mark of his high birth even if his costume had not proclaimed it. He wore a cloak of brown silk embroidered with gold, and over it a short, dark satin mantle tipped with ermine. From his cap waved a heron plume, fastened with jewels. He was a figure of beauty as he rode through the charming world about him, engaged in earnest talk with Alan. Behind the youths followed the squires and troopers, next the Duchess’s ladies, and in the rear the servants with the sumpter horses. It was an imposing though not a warlike train.

Their destination was Rouen, where King Richard had arrived, not, as Constance had hoped, to settle her affairs, but to consult with Philip Augustus about the Crusade.[10] It was all the more urgent, therefore, for the Duchess to seek an interview with him and ascertain his plans before he entered upon such a long and dangerous journey. The King had been notified of her visit and had arranged for her safe passage through Normandy, whose frontier she was now approaching. As they emerged from the woods Höel heard a cry and the sound of a struggle in a thicket close at hand, and ordered a halt. Before he began an investigation, the disturbers of the peace appeared. Two men were dragging another along, answering his appeals with blows and abusive epithets. The victim was an old man, and the sight aroused Arthur’s indignation. He rode up at once, and ordered the men to give an account of their conduct, and in the meantime to release the old man. The latter fell upon his knees and looked up to Arthur with tearful eyes. Höel and Alan came forward and heard the indignant protest of the two men. They declared they were bailiffs in the service of the King of France. “This man,” they said, pointing to the kneeling victim, “is a Jew. The last day of grace King Philip allowed the Jews has expired.”

“Is this true?” asked Arthur.

The old man looked up and said: “Listen, most gracious Prince, for, although I know you not, I can see the reflection of the crown upon your brow. Yes, it is true. The great King Philip Augustus, although he has long allowed our race to live in his kingdom, has now set his face against us. He has said, ‘Take the staff and leave the country; any one of you found in France after the day which I set shall die.’ The King’s servants have hounded us. They have plundered our homes; they have driven off our poor and wretched people. I was on my way to Holland, where our people have freedom to live, but I was so overcome by grief and hunger that I had to stay in the city until to-day—and now they have caught me.”

“It looks bad for you, Jew,” said Höel, shrugging his shoulders.

The bailiffs were again about to seize their prisoner, but Arthur cried: “Stop! Let him go free. It is my wish that he shall accompany us.”

“We are the King’s servants,” demurred the bailiffs, “and must obey his orders.”

“I am in command here, not King Philip,” said Arthur boldly and proudly. “I am the Duke of Brittany. Take yourselves off, or my men shall bind you.”

The bailiffs, astonished at the delicate boy, who spoke with such dignity, lost no time in getting away.

The Jew, when he realized that he was free, bowed to the earth before Arthur and kissed his feet. The old man was so tattered, befouled, and ill-favored that Arthur had some scruples about addressing him, but at last he said, “If I protect you as far as Rouen will you then take ship to Holland?”

The old man consented, saying, “God will help me on.”

Arthur gave him one of the packhorses, whose load was distributed among the other animals, and ordered the servants to let him ride with them. More quickly than might have been expected of one so weak, the Jew swung himself into the saddle and joined the little band, which once more resumed its march.

Constance took no part in the occurrence, and when Arthur rode up and entreated her approval of his act she said to him with some anxiety, “When the bailiffs complain to Philip he may be angry with you, my son.”

Arthur became thoughtful as Höel added, “The life of this Jew is of little consequence to Philip, for whatever he has of value the King will be sure to get.”

“How is that?” asked Arthur.

“The dispersal of the Jews was ordered to please the Pope,” said Höel, “and out of their wealth King Philip will raise the means for arming the Crusaders.”

“That is not kingly,” said Arthur indignantly.

“All the same they are Jews, and their treasures will be taken for the King’s service. How can it harm them anyway? They exude gold as these pines do pitch.”

Arthur reflected upon Höel’s words with considerable surprise and almost regretted his display of sympathy. But when he looked back and saw the bent figure of the Jew following the others, who shunned him, he thought to himself, “Still, I could not let him perish.”

That evening the Duchess and her most distinguished companions stopped at one of the stately abbeys of that region, and Arthur arranged that the Jew should spend the night with the servants who looked after the horses outside. They had soon become accustomed to their silent fellow-traveller, who served them for a laughing-stock.

After the fourth day the travellers at last approached their destination. They met crowds along the country road—haughty knights, warriors, and pilgrims intending to take part in the expedition to Palestine, besides ecclesiastics and monks, traders and shopkeepers. It was a good-natured crowd, but it often obstructed our travellers, and at times they were separated from each other. Arthur and Alan were frequently delayed by a group going in the opposite direction; then, laughing and shouting, they rejoined their party. But toward evening Höel decided to ride faster, so that they might reach the city before the gates closed. The party got more closely together, and Höel rode along the line, urging on both people and horses. While thus engaged he discovered that the Jew was no longer with them, and that the horse he had been riding was quietly following the others. Höel caught it by the bridle and looked about him to see if he were not mistaken. As he was doing so he noticed a piece of paper tied to the saddle, with a ring attached to it. He untied it and hastened to the Duke.

“Your ward has flown,” began Höel.

“So? Then he is both false and ungrateful,” said the Duke, in some confusion.

“Not this time,” replied Höel. “He has left the horse and this—see here.” He handed his find to Arthur, who took the ring from the paper with much surprise. Upon the billet was written in Latin:

“To the Duke of Brittany, in gratitude for saving his life.—Abraham of Paris.”

The ring was a heavy gold one with a magnificent emerald set in it. Arthur twirled it about, delighted with its brilliancy, then put it on his finger and placed the paper in his cloak.

“Abraham of Paris,” repeated the Duchess thoughtfully. “I well remember that name. He is called the richest of the Paris Jews. The King often bade him come to the court, and purchased jewels of him, and when he needed money Abraham furnished it; but I wish nothing to be said about our meeting him.”

After brief delay at the gate, the travellers were admitted and escorted to the place selected for them. As Constance was anxious to meet the King at once, she sent word to the seneschal and followed him to the castle, accompanied by Arthur, Höel, and Alan. A marshal met them near the entrance and called a servant to aid them in dismounting. There was in the courtyard such a crowd of knights, pages, and court people of various ranks that they made slow progress. Arthur paid little attention to the brilliant rooms through which they passed or to the persons who occupied them. His thoughts were fixed upon one object—to see Richard, his uncle.

The marshal bade Höel and Alan wait in the great hall, where two halberdiers kept guard, and then beckoned to a page and ordered him to wait upon the Duchess. The page disappeared behind a door, which he almost immediately reopened. Stepping back into an anteroom, he left the guests free to enter. With rapidly beating heart Arthur crossed the threshold, following his mother, and found himself in a spacious apartment, at the upper end of which King Richard rose from a carven arm-chair and advanced to meet the Duchess.[11] Arthur almost cried out when he saw the figure of the King before him, just as he had always imagined him to look, only more stately. The grandeur about him affected him but little, for his gaze was riveted upon the face of the King, which revealed dignity joined with strength and goodness, and upon those eyes which beamed so mildly upon his friends and flashed so terribly upon his enemies.

He greeted the Duchess cordially, took her hand, and said: “It is long, dear sister-in-law, since we met, and we have passed through great sorrows. But you have had one consolation,” he added, placing his hand upon Arthur’s shoulder. Arthur took the King’s other hand and kissed it. King Richard invited his guests to be seated and took his place between them. Then he looked at Arthur again, murmuring to himself, “Geoffrey! Geoffrey!” Tears filled the Duchess’s eyes as Richard continued: “We loved each other dearly. Geoffrey was less impulsive, and restrained me from committing many a rash act, but he stood by me to the last. Do you know, Lady Constance, when I was engaged in that unfortunate revolt against my father, how I came to you alone in the darkness of night, pursued by his soldiers? They demanded me as their prisoner, but Geoffrey would not surrender me, and we beat our assailants back from the walls. Geoffrey surely saved his brother, but in doing so he was in rebellion against his father.”

During this conversation Arthur was lost in contemplation of his uncle. Even without armor Richard was the ideal of a hero. He was the incomparable knight who in every tournament dashed horse and rider into the dust; for whom no foe was too strong, no fortress too secure, and who, after his victories, sang in competition with the troubadours.

A smile lit up Richard’s face as he noticed the boy’s rapt gaze, and, turning suddenly, he asked, “What are you thinking about, Arthur?”

“I was thinking,” replied Arthur with a start—“oh, I was thinking that my father could not help standing by you. As brother and as knight he could not have done otherwise.”

“And yet,” said Richard, looking at the red cross fastened upon his left shoulder, “the Church now demands that I shall go to the Holy Land and make expiation for my resistance to my father’s authority. I have promised to go, and shall keep my word, though it is hard to leave my kingdom, which is not yet quieted. Oh, Arthur, if you were only a man and could fight by my side! There is glory still to be acquired in the morning-land for him who is victor under the banner of Godfrey of Bouillon,[12] and the celestial crown of the martyr for him who falls.”

Greatly excited by Richard’s words, Arthur fell upon his knees, exclaiming, “I will go with you, my uncle and my king: I will be your page, your servant!”

Constance stretched out her hand as if to restrain him, but Richard said with a quiet smile: “No, Arthur; wait until you have come to a man’s strength. There will be great deeds for you to perform later.”

Arthur and the Duchess rose to take leave of the King, who embraced her, saying: “As you may be in need of rest, I will not detain you longer, but I will receive you again to-morrow as my guest.”

The King struck a shield hanging upon the wall, whereupon two pages and the marshal entered, and under their respectful escort the Duchess and Duke left the castle after they had been rejoined by Höel and Alan.

On the following day Arthur saw Richard in the midst of his brilliant and warlike retinue. The Duchess sat at the table next to the King, with Arthur by her side. Famous men, knights, statesmen, and ecclesiastics had seats below the Duke, who was quite elated because his rank placed him next the King. Their greetings reminded him that he must prove himself worthy of them by his own merit and heroic deeds, and a new world was revealed to him as he listened to the words of these men of wide experience, though he but half understood them. Many a one noticed the enthusiasm of the boy, and his high-bred mien, and was charmed by him. When King Richard raised his glass to drink the health of his sister-in-law, the Duchess Constance, the guests joyously responded, and added, “Long live Duke Arthur of Brittany!”

Greatly excited, Arthur rose to thank them, and, turning to Richard, exclaimed, “I will prove myself, my royal uncle, worthy of the honor paid me by these brave men.”

His admirers gathered about him enthusiastically, spoke of his great and brilliant future, and praised him as a true scion of the Plantagenets.

“Did you hear, Alan?” he said to his devoted friend, when at last they were alone in their room; “I am destined to achieve fame and greatness. I shall no longer be content to lead a quiet, unknown life.”

All who came to know the Prince held him in the highest esteem, and were surprised that so noble a youth had developed in comparative obscurity. Many thought that King Richard might be childless, and that he was going to a distant war which would be full of danger. In that case the next heir to the English throne was Arthur.

Hardly a word passed about Constance’s affairs and Höel’s solicitude. Richard referred her to King Philip as soon as he should arrive; and when Constance, greatly embarrassed, asked, “Are you angry because we accepted his protection in a time of need?” Richard replied, “I do not blame you; you had to have him for a friend, for England left you in the lurch. My mother—” Here the King broke off abruptly, and then closed by saying, “I think everything will be arranged by Philip. Arthur, of course, will keep Geoffrey’s possessions, not only because of respect for the dead, but also for our love of his son.”

After a week, which to Arthur passed like a pleasant hour, King Philip arrived in Rouen. His principal counsellors and several high ecclesiastics were in his retinue, but not so many soldiers as in that of Richard.

Arthur was present at the first meeting of the two sovereigns, and Philip’s searching glance discovered him even before Richard introduced them. At the words, “My cousin and ward,” Philip stooped and kissed his forehead. When Arthur, greatly moved by his cordiality of manner, greeted him as the protector of his childhood, Philip’s serious face was illuminated with a gracious smile, revealing the favorable impression the Duke had made upon him. He had always sought the control of the Duke of Brittany to hold England in check, but now he so unexpectedly found Arthur such an engaging personality that he determined not to lose sight of him. He called upon Constance and renewed his assurances of friendship. When she expressed some anxiety lest, in the absence of the two kings, she might be troubled by Eleanor, who was to remain in England as regent, Philip invited her to go to his court. “You and your son,” he said, “shall be under my feudal protection; and should you have any fear for your personal safety, you can be sure of an honorable reception in Paris.”

Constance expressed her thanks in Richard’s presence, hoping he would make a still closer claim to Arthur; but the Crusade monopolized all his thoughts. He had already recognized Brittany as the hereditary fief which would belong to Arthur when he came of age, and with this assurance Constance had to be content.

The departure of King Richard well-nigh broke Arthur’s heart, and Richard embraced him with deep emotion. Philip admonished them again to go to Paris whenever it seemed best.

“That will yet happen,” said Höel to Alan on their way back. “Philip well knows that fate will force Arthur into his arms. Had Richard thought more of the future, we should not have been going home thus.”

The friendly reception which the young Duke everywhere met as he reëntered Brittany made the home-coming very dear to him. The situation had changed, as he now realized, and the people had great expectations of his future. When he came to the gates of cities, the people went out to meet him with welcomes and good wishes. Arthur showed interest and kindness for all, and the Duchess gave him precedence everywhere and rejoiced at the enthusiasm manifested for him, both by high and by low.

Upon their arrival at Rennes they received sad news. Bertha was no more. She had died after a brief illness. It was the first real sorrow in Arthur’s life, and his grief was hardly less than that of Höel and Alan, who felt as if their happiness were forever lost. It separated Arthur’s present life from his past life, and served to concentrate his thoughts upon the future. All the news from the great world, into which he had had a brief glance, now became of interest to him, especially everything concerning the Crusade. As time passed, wandering pilgrims and minstrels came and told of events in the morning-land,—of Richard’s exploits before Acre and Ascalon,[13] and of his heroic conduct in times of danger, which had won for him the name of “Lion-hearted.” Then news ceased to come for a long time; but suddenly the report spread that Philip Augustus had returned to France with only a remnant of his army. It seemed incredible at first, but they soon found that it was true, for the Duchess received a letter from Paris in which Philip urgently requested her to come there with Arthur. She hesitated, however, for her safety in Brittany was not imperilled. The King’s letter surprised them all, particularly Arthur, who had a presentiment that it foreshadowed a turning-point in his life.

One evening a pilgrim appeared at the castle gate and desired to speak with the Duke. The latter had just returned from the chase and was standing in the anteroom as the stranger entered.

“Rest yourself, holy man,” said Arthur, “and then tell me your errand.”

“Allow me to speak with you in private,” replied the pilgrim. After Arthur had dismissed those standing about, the pilgrim whispered a few words to him.

Hardly had he done so before Arthur made a loud outcry, and rushed into the terrified Duchess’s apartment, exclaiming, “Richard is a prisoner!” As he knew nothing more about it, the Duchess, after summoning Höel, had the pilgrim brought to her, and asked him for the particulars. As soon as the latter removed his palmer’s hat, Höel recognized him as Count Guntram, one of the Crusaders in Richard’s army. After the first greetings he told, at Arthur’s request, the story of the events which led to the abandonment of Palestine. Forsaken by his allies, whom he had alienated by his haughtiness of manner, Richard realized when it was too late that he could not rescue Jerusalem with his army alone. He withdrew reluctantly from the Holy City, and decided to return. His vessel was separated from the others and wrecked upon the Italian coast. Too impatient to wait for the rest of the fleet, he undertook to retreat with a few companions. As they had to traverse a hostile country, they adopted the garb of pilgrims, but they could not elude the sharp scrutiny of spies. Richard fell into the hands of the Duke of Austria, whom he had greatly offended during the Crusade, and the Duke consigned his distinguished prisoner to Henry the Sixth, Emperor of Germany.[14] His fugitive companions were making their way to their homes.

Arthur, completely absorbed in Richard’s fate, contemplated plans for his deliverance, and had no doubt that all the princes would unite with him to rescue the prisoner. Guntram, however, gloomily shook his head, and said: “Richard is imprisoned in the strong castle of Trifels[15] on the Rhine, and there he will remain until he is released for a heavy ransom. Think rather about yourself and your own affairs, noble Prince. Your Uncle John, hoping that Richard will never return, is preparing to attack Brittany and get you into his power as soon as possible. Make your escape at once, lest all the noble scions of the house of Plantagenet fall, and John remain, to the misfortune of the world.”

Knight Guntram frequently repeated his warning before he left the Duchess’s court, and the impression it made upon his hearers was soon strengthened by indications of its truth.

The country gradually began to grow restless and excited. The coast-dwellers removed into the interior, for English vessels had been seen, and they feared a landing. A letter also was received from Queen Eleanor, in which the Duchess was warned not to make any claims upon England for her son’s rights, as they would not be recognized. In the event of Richard’s death, John, who was now sharing the sovereignty with Eleanor, would certainly succeed to the throne.

In view of the manifest danger to the Duke’s rights it was decided that they must seek the protection and help of Philip Augustus. Accompanied by their nearest and most devoted attendants, Duchess Constance and Arthur once more set out, this time upon an eventful journey. Mourning over the fate of their country and their own fate as well, they left their beloved Brittany. Hardly had they crossed the frontier when John’s troops poured into the country, beat back the mercenaries of Philip Augustus, and placed his banner above the gates of the city. The people mournfully submitted to his yoke, hoping in their secret hearts for the return of their legitimate ruler.

Constance and Arthur were received at the court of Philip Augustus in Paris not after the manner of fugitives. The King gave them royal recognition, and his spouse, the gracious Agnes of Meran, greeted them most cordially. Philip evinced a peculiarly friendly interest in Arthur; but he met his urgent request for assistance with a quiet smile, saying, “I shall do all in my power to help you to retain your possessions and all your rights. In the meantime, as there is a quarrel to be settled between me and the Count of Flanders, will you go with me and win your spurs on my side?”

The King looked sharply at Arthur, who, thirsting for action, acceded to his proposal notwithstanding the Duchess’s disapproval. She was obliged to consent in the end, however, for Höel and Alan, who found idle court life intolerable, gladly agreed to go also, and were eager to participate in the affair.

Arthur was to be admitted to knighthood at once, and chose Alan for his brother-in-arms. During the night which preceded the important ceremony, the youths kept knightly vigil to uplift their souls in prayer. They were escorted by Höel and some of the leading knights to the castle chapel, where they were left alone, after an impressive parting. The barred doors shut them out from the world, and they knelt a long time before the altar, engaged in their devotions. These concluded, they arose, and with drawn swords made a circuit of the chapel walls, pausing at times before the memorials of distinguished princes, whose statues seemed almost ghostly in the uncertain flickerings of the ever-burning lamps. The banners fastened to the columns, which reached to the dome, fluttered, and the trophies gave out a hollow sound as the youths passed them. At last they reached the altar again, and almost involuntarily Arthur began to express his deep emotions. He thought of the cruel fate which had snatched his father from him, and of the sorrowful burden which had overwhelmed his mother. With a firm voice he pictured the future for which he longed so ardently and hopefully. He would earn distinction and fame under Philip’s leadership, and all brave heroes would gladly help him in his struggle for his rights. Then, when Richard had returned to the throne of England, and he had earned Philip’s good-will, how successfully his life would unfold! “And you, Alan, my brother-in-arms,” he said, turning to him, “shall always be nearest my side, however high a station I may reach.”

Glowing with youthful enthusiasm, Alan knelt before Arthur and lowered his sword with the utmost reverence, for he believed in Arthur with all his soul. Joyfully the latter exclaimed: “Oh, that a sign might be given to reveal my future!”

At that instant the moon broke through the clouds and illuminated the lofty stained glass windows. In the sudden crimson glow Arthur and Alan looked as if they were sprinkled with blood. Their faces, hair, and shoulders were tinted a deep red. They gazed upon one another with astonishment, but the red glow soon disappeared, and they were once more in the semi-darkness. Though the effect, which was caused by the light passing through the ruby-red panes, was easily explainable, yet they were deeply impressed by it. They spoke no more, but stood motionless by the altar, awaiting the coming of day.

The morning light had hardly broken when the doors of the chapel were opened and a band of knights came to greet their new brothers. Höel embraced them and smiled at Arthur’s disturbed countenance; but when he saw that Alan too was pale and agitated, he became serious. There was no time to question them, for a multitude quickly poured into the chapel. The entire court was soon assembled. The ecclesiastics gathered about the altar, and at last the King entered with the Queen and the Duchess Constance. At the close of the religious service Philip entered the chancel and bade Arthur kneel. Touching his shoulder with his sword, he dubbed him knight and received his vows. When Alan had likewise been admitted to knighthood, their golden spurs were given them, and shouting “Saint Denis!” and “Saint George!” the knights embraced their new comrades. All present joined in congratulation, and Höel had to tear them away almost by force, so that they might have rest and refreshment and be in readiness for the afternoon’s tournament. When the time came, they were assisted in putting on their armor by knights, but Arthur kept his sash in his hand so that his mother might bind it about him. The gloomy night was forgotten, and as he passed along the spacious corridors of the Louvre[16] every one he met stopped to admire his youthful beauty and to make smiling return for his friendly greeting.

As he approached the Duchess’s apartment he heard delightful strains of music, and hesitated about entering; for Constance, since the great sorrow had come into her life, seldom touched the harp. At last, however, he softly opened the door and glanced into the large room. The Duchess was reclining upon a couch, her head resting upon her hand, and her pale face bedewed with tears. A young lady, who was playing the harp, sat near her on a tabouret. She ceased as Arthur quickly advanced and bowed low to the two ladies. The younger rose in surprise and looked inquiringly at the Duchess, who took her hand and, turning to Arthur, said, “You must know, my son, who has played so beautifully for my consolation. This is the Princess Marie of France,[17] whom Philip has brought from the cloisters to-day. Though it is our first meeting, she well knows my sorrow.”

“Noble lady,” said Marie gently, “I too have known sorrow. My mother is dead.”

“May the blessing of Heaven comfort you, gracious lady, and bring its peace to a heart which knows so well how to comfort others,” exclaimed Arthur. “I shall go to the field contentedly, for I know that an angel will be at my mother’s side.”

Trumpet peals from the courtyard summoned to the tournament. The clank of armor was heard in the anteroom, and knights were in waiting to act as Arthur’s escort.

“It is my first venture with arms, dear mother. Give me your blessing, I beseech you,” implored Arthur; “and you, Princess, shall tie on my sash as a surety of good fortune in the contest.”

Marie directed a questioning glance at the Duchess, and when she smiled in return, threw the scarf over Arthur’s shoulder and fastened it. After a word of thanks, Arthur hastened to his waiting associates, and the ladies betook themselves to the Queen, whose guests they were to be at the tournament.

The field was encircled with a dense throng of persons of all ranks. The spectators watched Arthur eagerly as he rode in, followed by Alan and four knights, who drew up in line. Their adversaries confronted them in similar line. At a signal from the King the knights rushed at each other. Höel smilingly watched his protégés, who distinguished themselves by their daring and dexterity. At the first onset Arthur parried the thrust of his enemy, and at the second advanced from the other side with such fury that his opponent was taken off his guard and was dismounted. Arthur was declared victor. The same good fortune attended him in the remaining contests, and at the close he received a wreath from the Queen’s own hands as his prize. Never was handsomer knight seen than Arthur, as with visor raised he lifted his crowned head and saluted the princesses. At the court banquet he was assigned a place between his mother and the Princess Marie, and his heart swelled with joy and pride.

The time for the departure of the expedition drew nigh, and Arthur spent his leisure moments in the company of the Duchess and her young friend. On the last evening the King visited them, and after a brief conversation turned to the Duke. “Take a long farewell,” said he. “Guard yourself in battle, for your reward will be Marie’s hand.”

Arthur and the Princess stood speechless with surprise for some time, but the silence was at last broken by the Duchess: “Yes, Arthur, it is the King’s will to give Marie to you as wife, and to me as daughter, some day, when our lot is a happier one.”

“For that I hope, with God’s help,” answered the King.

Arthur was in the field several months with Philip, and though he had to endure all that powerful warrior’s severe discipline, he fought for him as valiantly as he would have done for himself. All this time the enemy remained unsubdued; but at last the King, having cut off all probable chance of escape, looked for a decisive result. The day for the attack was fixed, and everything was made ready. On the evening before the battle, after issuing his orders, the King retired to his tent to read some letters which a messenger had brought from Paris. The chancellor urgently entreated him to return, for disorder was spreading, and the finances were in such desperate condition that he could procure no more money.

“Ha!” said the King to himself, “how shall we meet the needs of the Empire? There is but one way. The Jews must empty their pockets. The ban shall be raised. We expelled them to please the Pope, who is now secretly plotting with my enemies against me and annoying me in every way.” The King called for his secretary, but instead of that official a knight suddenly entered the tent. Recognizing Arthur, he waited for him to speak.

“Oh, my King,” said Arthur excitedly, “I have had news from my uncle.”

Philip frowned and asked, “What does John want now?”

“My news is not from John; I am speaking of Richard. He is free. He is no longer a prisoner in the castle of Trifels.”

“How,” interrupted the King, “has the ransom been furnished?”

“He is free,” repeated Arthur; “a deserter from the Netherlands brought the tidings. Richard has embarked on the Holland coast. They recognized him, though he went there in disguise.”

“Alone!” said the astonished King. “Oh, the Lion-hearted!”

“Without doubt he has crossed to England,” continued Arthur excitedly, “and now it is time my King, for me to hasten to his assistance.”

“Thoughtless youth!” broke in Philip, “would you forsake me before the end of the campaign and ingloriously leave before we know whether Richard has actually reached his fatherland?”

Arthur grew thoughtful, and retired to consult Höel and Alan. The latter was eager to go, for he was not enthusiastic in his devotion to Philip; he would rather have fought for Richard. But Höel twirled his gray mustache and shook his head. He feared Richard’s rash and unstable disposition, and knew that he could not be relied upon. “Philip is right in this matter,” he said. “Let us first dispose of this Fleming; after that it will be time to think of the other matter.”

The battle was fought the next day, and resulted in the defeat of the Count of Flanders after a stout resistance. The King himself led his warriors, sword in hand, in an attack upon the enemy, who were seeking to hold a bridge. His battle-cry, “Montjoie St. Denis!”[18] spread panic in the ranks of his foes, and “Plantagenet!” “Plantagenet!” resounded where Arthur and his knights were fighting.

The victory was won. The enemy were driven over the bridge, and threw away their arms. The King warmly congratulated Arthur upon his bravery, but did not grant his request for leave of absence. Arthur reluctantly submitted rather than make his appearance before Richard as a fugitive without knights or warriors.

In the meantime Richard reached England; and as soon as he had announced his presence to his friends he ascended the throne amid popular rejoicings, John yielding his claim with seeming willingness. About the same time Philip returned to Paris; Arthur accompanied him, and was so delighted to see his mother and bride once more that he forgot his longing to go to Richard.

Banquets and tournaments were arranged by the court, and Arthur, because of his bravery, was the central figure among all the youthful heroes. So continuous were the feasts and sports that he hardly had time for thought.

One morning Alan, equipped and spurred as for a long ride, came to Arthur’s bedside and woke him, saying, “Richard is in France.”

“Let us hasten to him, then,” said Arthur, springing up.

“You had better not go. It will only occasion needless delay. Let me go to your uncle,” implored Alan. “I can reach him quickly. He is about to attack the Duke of Limoges, and is camped with his little army before the fortress of Chalus. I will tell him all, and if he calls you, you need no longer hesitate. Let me go, my Prince, and keep my mission a secret from the court. They are playing false with you, one and all.”

Alan rushed out, and Arthur looked after him in surprise. Only Höel knew of his son’s undertaking, and he gave out that he had sent him away. Philip, who was well apprised of what was going on, kept quiet, and only sought to attach Arthur to him still more closely.

When the entertainment came to an end, Philip left the Louvre to hold court at Compiègne[19] during the beautiful springtime. How delightful it was to roam about that great forest! Every day the Princess rode on her white palfrey, with her falcon attached to her slender wrist, Duke Arthur riding by her side upon his fiery Arab steed, which had been given him by the King. A band of companions and servants on foot and on horse followed them, and the hills and woods resounded with the baying of hounds and the halloos of hunters. A mystic charm seemed to pervade the greenwood, which protected them from all contact with the outside world and made life a happy dream. The Duchess herself seemed to forget her grief and the insecurity of her affairs, and the King encouraged all these joyous sports without participating in them.

But suddenly these happy revellers were recalled to the realities of life by a fearful occurrence. King Richard the Lion-hearted was dead before Chalus—killed by an arrow. Arthur could not believe the dreadful news until Alan, pale and exhausted by his hard ride, arrived and confirmed it. He came from the spot, was with the King when he received his death wound, and brought his last message of continued faith in Arthur’s loyalty and uprightness, and his wish that he could once more see his nephew. But, alas, it was too late now! The great Lion-hearted was gone, and John mounted the vacant throne.

“Never, so long as I live, will I relinquish my paternal inheritance,” exclaimed Arthur.

In the excitement which King Richard’s death produced in England, Eleanor contrived to secure an appearance of justice in John’s sovereignty. A spurious will of Henry the Second’s was opened by her, by the provisions of which John was given the crown, regardless of the legitimate claims of the son of Geoffrey, his oldest brother. By this means Arthur was also cut off from the succession. The injustice was clear enough; but John, with the aid of a strong following of the nobles, whom he had secured by artifice and promises, kept possession of power. The time was now come for Philip Augustus openly and without delay to maintain Arthur’s rights. Nothing less was at stake than the title to the English crown. John was declared a throne-robber, and was summoned as a feudal tenant before the French tribunal. In case of disobedience war would be declared against him. John had already made his plans to go to France at the head of an army, with the intention, as far as he was able, of permanently wresting the English provinces from the domination of France. He had not a doubt he could easily settle the claims of Constance and Arthur and succeed in his purpose. Determined as Philip Augustus may have been to defend Arthur’s rights, somehow the war preparations were delayed much longer than seemed safe to the Duke, who could scarcely conceal his impatience. He resolved to challenge his uncle to single combat, and reluctantly followed the advice of his mother to act with caution.

“Why does Philip hesitate?” he indignantly exclaimed.

“I believe the King is waiting for money,” replied Höel.

Arthur contemptuously shrugged his shoulders.

“Alas!” sighed Constance, “how can our plans succeed? We are very poor.”

Arthur hastened to the Louvre, and although the chamberlain informed him that the King was holding an important interview, he insisted upon admission. Nothing could be more urgent than his own affairs.