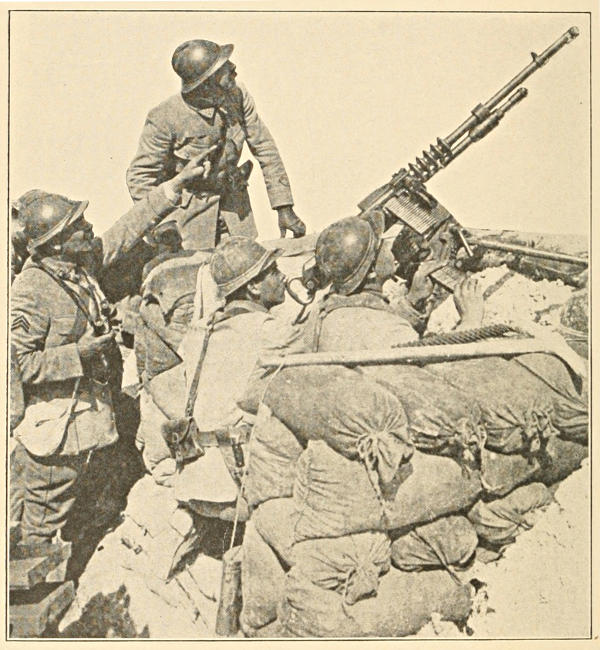

“He’s Hit,” Sergeant Lace Cries suddenly. And indeed He Is Hit. See page 101

COVERED WITH MUD AND GLORY

“He’s Hit,” Sergeant Lace Cries suddenly. And indeed He Is Hit. See page 101

COVERED WITH MUD

AND GLORY

A Machine Gun Company in Action

(“Ma Mitrailleuse”)

BY

GEORGES LAFOND

Sergeant-Major, Territorial Hussars, French Army; Intelligence

Officer, Machine Gun Sections, French Colonial Infantry

With a Preface by Maurice Barrès

of the French Academy

Translated by Edwin Gile Rich

INCLUDING

“A Tribute to the Soldiers of France”

BY

GEORGES CLEMENCEAU

BOSTON

SMALL, MAYNARD & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1918

By Small, Maynard & Company

(INCORPORATED)

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

To the Memory of

My Comrades of the second company of machine guns of the ... first Colonials

who fell at the battle of the Somme in July, 1916, and of the Aisne in April, 1917;

To

Lieutenants Maisonnave and Dupouy

in remembrance of the hours of fine, sincere comradeship we lived together;

To

Denys Maurin

the quartermaster-sergeant, wounded heroically before Soissons, in testimony of a sincere friendship which was born under shell-fire, which grew amid the horrors of grim madness, and which was firmly fixed through sharing common hopes and common joys;

I dedicate these simple pages

which are only a modest contribution to

the monumental narrative which these

anonymous epics of every day would make

By Georges Clemenceau

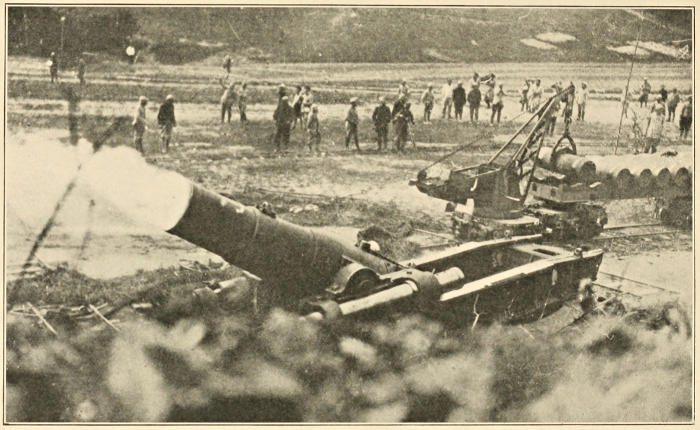

I watch our blue-uniformed men at war, as they pass with a friendly and serious look, generously covered with mud. This is the artillery—slow marching—which is moving its cannon under a fantastic camouflage, a mockery of reality. A glistening slope of soaked earth is set in a frame of shattered trees, twisted into indescribable convulsions of anguish with the gaping wounds inflicted by the storm of iron. On their horses, already covered with winter shag, the poilus, slouched in all sorts of positions, having no suggestion of the rigid form of the manœuvre, are going from one battlefield to another without any other thought except that of just keeping on going.

In colorless and shapeless uniforms, indescribably rigged out, and in poses of the most pleasurable leisure, the soldiers of France picturesquely[viii] slip from glory to glory, less aware, it seems, of historic grandeur than of serene gladness in implacable duty. They are picturesque because nature will have it so, but without any romanticism or sense of posing—officers hardly to be distinguished from privates by vague, soiled stripes—all the men enveloped in a halo of splendor above anything known to ordinary humanity.

The pugnacious pipe or the sportive cigarette hinders their expression of any personal reflection. Only their eyes are animate, and these express things which cannot be told in words lest they be profaned. The line of their lip is youthful under a silky moustache or firm with age under gray brush. But the fire of their look, framed in their dark helmets, leaps out with quiet intensity to meet the tragic unknown that no longer can bring surprise. They are our soldiers of the year II who are following the Biblical column of fire. They see something. They go to it. Ashamed of my humility, I should like to find words to say to them. But, were I a poet, they would have no need of hearkening to me, since the greatest beauty of man lies in them, and since, unwitting[ix] of utterance, which at best seems inept, these men live on the summits of life.

And the “old classes” who prosaically break stone at the side of the road or work with the shovel, the pickaxe, the broom, making the toilette of the road of triumph, what an injustice if I did not mention them! How does it happen that the noblest soldier is always the one I chance upon? That is the miracle of these men; and when I tell you that on the battlefield of the Aisne the “old classes,” not granting that it was necessary to wait to the end of the battle before beginning to clear and rebuild, went off into the hottest of the action to fill up craters, to break stones, to place tree-trunks and beams during heavy fire, without vouchsafing the Boche a single hasty gesture, so that they might the more quickly open the way for revictualling and for the bringing up of artillery—when I tell you this, you will admit that they do not deserve a lesser greeting than their “young ones.”

And the infantryman—could I commit the supreme injustice of forgetting him? That is impossible when one has gone over the battleground where he has taken possession of the burrows[x] of the Boches, among heaps of munition material, cases of supplies, an indescribable débris, abandoned with their dead and wounded in the haste of a desperate fight. What we cannot understand is that our little poilu can pass so quickly from the apathy of the trench to the extreme fury of the attack, and then from the violence of the offensive to the calm smile of a victory of which his modesty seems to say: “It was as easy as all that.”

I did not hear a single boast, or see a disagreeable act, or hear a word that sounded false. Like a good-hearted proprietor returning home, they took possession of the shelters of the Boche so hurriedly abandoned. Here can be found the comforts of war, if these two words can be spoken together. The men talk in groups at the openings of the underground passages, camouflaged by the enemy himself. The indifference of their attitudes, the ease of their familiar conversation, in which there mingle no bragging (though this is the place for it), are more characteristic of the situation of some simple bourgeois who have happened to meet on Sunday in the street. A major begs my pardon for wearing a collared shirt,[xi] which is not perfectly “regular” at an official review. Messengers pass, throwing out a word or making a simple sign. Officers step up for brief explanations. A half-salute, a nodding of the head—it is over. Not far away, on the road cut into the rock, where the stupid Boche, after our passings, sends his impotent shells, our always young “old classes” hang on to the slopes in order to see the projectile fall, and make uncomplimentary remarks about the gunner. Then work is resumed till the next warning whistles in the air.

It is after twelve and we have not yet dined. A big devil of a Moroccan colonel, with a Don Quixotic face under an extraordinary headpiece, invites us to his P. C. (post of command), where the Boche has left useful bits of installation. A black hole is two steps away from us. We go down into the ground, over abrupt descents, and there we are protected from the “marmites” in a dark corridor lit by candles stuck into the mouths of German gas masks. We sit down on anything handy (I even have the favor of a chair), before a board which also serves as the colonel’s bed, while arms whose body remains[xii] invisible serve us with dishes not to be disdained by a gourmand. How did they get there? I cannot undertake to explain that. The walk in the open air, the tragic nature of the place, the joy in land reconquered, no doubt all lend particular spice to the comradeship of these men who forget that they have done great deeds as soon as they have done them. Pictures and illustrated pages tremble in the fluttering candle-lights, among them a Victorious France, drawn by the pencil of the colonel. A telephonist measures out mouthfuls of conversation to a military post that sends in observations and receives ours. Long time or short time, for here hours and minutes are alike, here is a magic that ends too soon. We must go.

The colonel would have been perfect if he had not made it a point of honor to avoid all danger for his civilian visitor. In the morning he had tried to forbid me a flying visit to the marvellous castle of Pinion, but he finally understood that even a soldier has to be born a civilian and that he should not therefore scorn his own origin. The trip was accomplished without the shadow of an incident, but the colonel, who insists more[xiii] than ever on the rights and privileges of the uniform, will not permit me to return until the Boche cannon favors us with a little respite. The Boche can hardly make up his mind to such a favor; hence, several false departures and changings of direction. Finally, the colonel lets us go under the guard of a robust sergeant-major, who even yesterday magnificently led his stretcher-bearers to the aid of the wounded under the hottest fire. Although he is not of the youngest class, he has refused to be retired from the front. He is spoken of only with respect, I might say admiration. “He goes everywhere.” He is fine, genial company. After many necessary little zigzags, a walk that is not very strenuous and very soon over, I left the brave sergeant, whom I shall always remember.

I cannot finish this inconsequent account without speaking of the touching ceremony which I witnessed at Soissons, the terribly bombarded. Since the victory of Malmaison the city has been out of range. But when you have seen the building of the sub-prefect tottering with shell-holes, a building that neither the sub-prefect nor his wife has left, the shortest walk will tell you a long tale.

The general, who is a good fellow—I take pleasure in saying that—had proposed to show me something, and so here I am in a public square having the imposing silhouette of the cathedral as a background. From the height of the great towers, with their wide wounds, history, attentive, looks down. Everywhere there is a formidable display of cannon taken from the enemy. There are piles of them, heaps of them. There are too many to count, together with a bewildering mass of trench instruments of all sorts. Can you believe it? They do not hold the eye. How is that possible? Because on the sidewalk opposite, in splendid alignment, is the gorgeous gathering of soldiers with medals and decorations who have captured these things. Ah! They hold the eye! There they are, with all sorts of faces and from all branches of the service, with the flag which they have followed into battle and which now must be present at their honor.

To be quite honest, the group is not so æsthetic as a picture of Versailles. These men are too great for much ceremony. With a jerky step the general advances; his brusque movements reveal the homage of his emotion before the[xv] bravest of the brave. Slowly he passes along the line, while the adjutant reads in a stirring voice the high deeds in the citations. And the military medal quivers on each noble breast at the recollection of the tremendous drama lived through. And the general utters a comrade’s congratulation, shakes a friendly hand, expresses a good wish. Then the flag salutes, while the drums rumble in these hearts drunk with love of country. At the greeting of the flag of the glorious Chasseurs, a rag torn by machine guns, something gets hold of our throats, which the trumpets hurt with their sublime peal. If there are more beautiful spectacles, I do not know them. One minute here is worth years.

And I have said nothing of the people about, silent, all in mourning, their souls full of tears, which finally brim over. Men, hats off, motionless as statues, proud of becoming great through their children. Mothers, with seared faces, superbly stoic under the eye of the greater maternity of the great country. The children in the ecstasy of feeling about them something greater than they can understand, but already certain that they will understand some day this immortal hour.[xvi] And not a cry, not a word sounds in the air, nothing but the great silence of the courage of all of them. Then everyone goes away, firm and erect, to a glorious destiny. In every heart La France has passed.

Note.—A few days before M. Clemenceau, premier of France, was called to power, he returned from a visit to the Aisne front and published his impressions in his paper, L’Homme Enchainé, now L’Homme Libre. When he became premier, L’Illustration republished this “Tribute to the Soldiers of France,” and it has since been widely reproduced and admired throughout France. The present English translation by Harry Kurz was printed in the New York Tribune, to the editors of which grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint here.

Sergeant-Major Georges Lafond, of the Territorial Hussars, the author of this book, was in South America at the time of mobilization. He returned to France as soon as possible and joined his corps, but asked to be assigned as intelligence officer to the machine-gun sections of the ... first regiment of Colonial Infantry.

With this picked corps, which has been decimated several times, he took part in the engagements in Champagne, on the Somme, at Lihons, Dompierre, Herbécourt, and notably in the days from the first to the fifth of July, where the regiment earned its second citation and received the fourragère.

Lafond was discharged after the battles of Maisonnette, and wrote this book of recollections in the hospital at Abbeville, and afterwards at Montpellier, where he had to undergo a severe operation.

Sergeant-Major Lafond’s narrative makes no claim to literary pretension, but it is simply a collection of actual occurrences. It is a series of short narratives which give the life of a company of machine gunners from the day of its formation to the hour when it was so decimated that it had to be reorganized with men from other corps.

What pictures the following titles call to mind: “A Reconnaissance in the Fog,” “The Aeroplane,” “Our First Engagement,” “‘We Have Taken a Picket Post,’” “The Attack,” “The Echelon,” “A Water Patrol”! No man who has lived at the front and has taken part in an attack will fail to recognize the accuracy of these narratives and to experience, as well, emotion, enthusiasm, and pride in having been among “those who were there.”

This record of adventure was very successful when it appeared in the Petit Parisien, and I feel sure that it will be successful in book form. I beg Sergeant-Major Georges Lafond to accept my hearty congratulations on his fine talent and his bravery.

Maurice Barrès,

of the French Academy.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | The Search for My Company | 1 |

| II | The Quartermaster’s Billets | 11 |

| III | The Echelon | 21 |

| IV | The Song of the Machine Gun | 31 |

| V | A Reconnaissance in the Fog | 47 |

| VI | Our First Engagement | 58 |

| VII | Easter Eggs | 71 |

| VIII | The Aeroplane | 89 |

| IX | Days in Cantonment | 103 |

| X | An Ordinary Fatigue Party | 122 |

| XI | With Music | 135 |

| XII | “We Have Taken a Picket Post” | 148 |

| XIII | A Night Convoy | 164 |

| XIV | The Songs of the Homeland | 175 |

| XV | A Water Patrol | 188 |

| XVI | A Commander | 199 |

| XVII | The Attack | 217 |

| XVIII | With Orders | 232 |

| XIX | A Wreath | 250 |

| XX | Discharged | 261 |

| PAGE | |

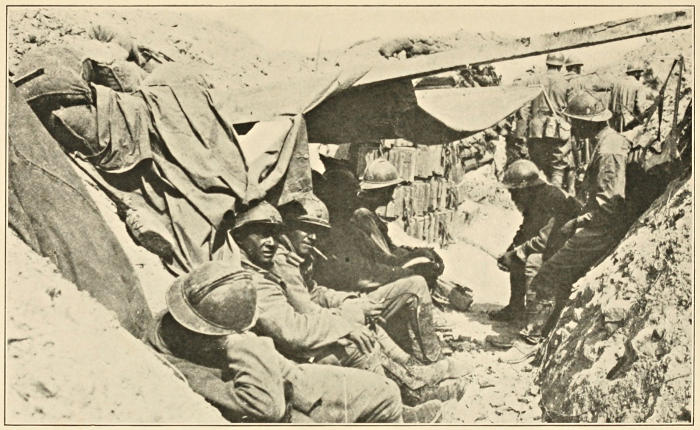

| “He’s Hit,” Sergeant Lace Cries Suddenly. And Indeed He is Hit | Frontispiece |

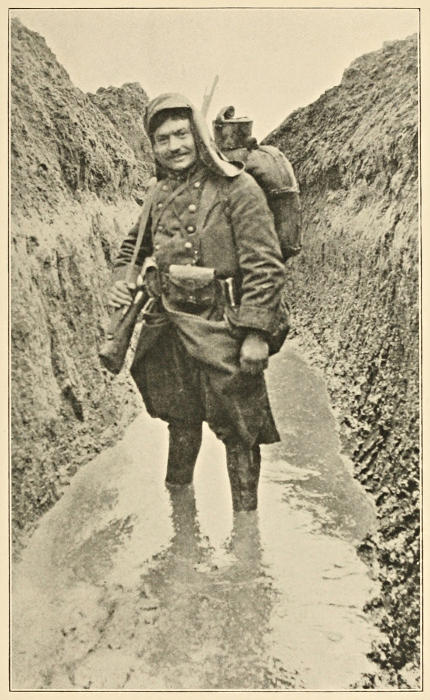

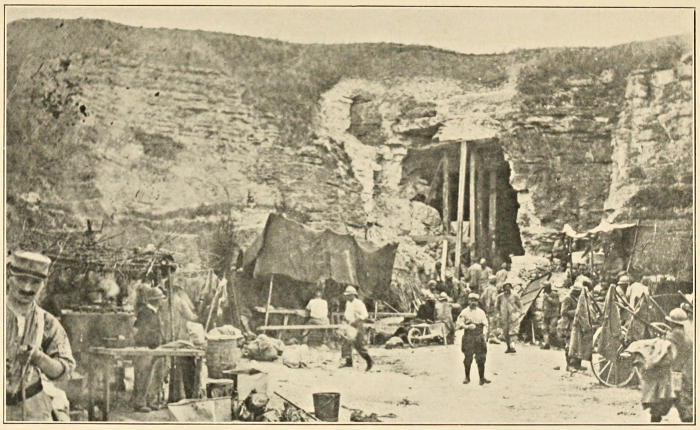

| Remains of Villages near the Lines | 36 |

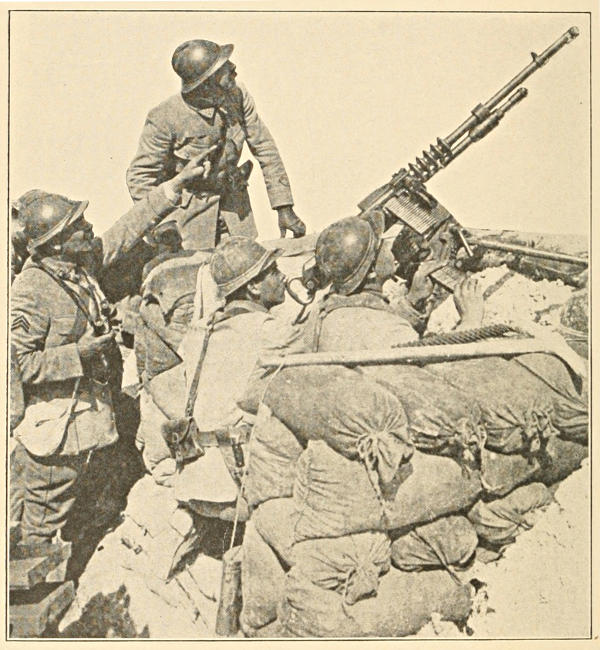

| A Poilu | 56 |

| A Sinister Grumbling Seemed To Shatter The Fog | 110 |

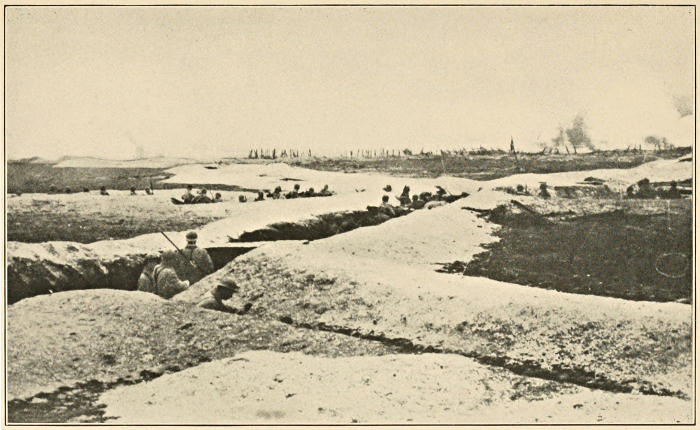

| The Front Line Trench | 154 |

| A Commandant’s Post | 166 |

| The Least Dangerous Passage is the Unprotected Ground | 186 |

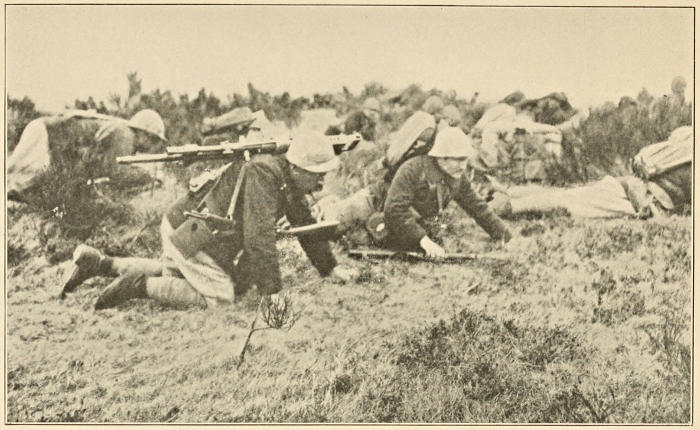

| The Attack | 226 |

Note.—These photographs are all copyrighted by International Film Service, Inc.

I remember the exact date and I have reason to, for on that Monday, February fifteenth, I joined the second company of machine guns of the ... first Colonials at the front. It was snowing and the fields of Picardy were one vast white carpet on which the auto-trucks traced a multitude of black lines to the accompaniment of pyrotechnics of mud.

Two days before I had left my depot in a small garrison town in the center of Provence, which lay smiling in the sun and already bedecked with the first flowers of spring. At Lyons I found rain, at Saint-Just-en-Chaussee, snow, and I got off the train in a sea of mud.

In the dim light of a February dawn, the station at Villers appeared to be encumbered with[2] the supplies of half-a-dozen regiments. My car was high on its wheels and at the end of the train farthest from the unloading platform. At the other end of the platform near the entrance to the station, I found a rolling bridge for unloading animals, but it was useless to ask those busy people to help me push this weighty contrivance to the car.

So I looked at Kiki—Kiki is my horse—who had but recently arrived from Canada and was scarcely broken after his two months’ training at the depot.

“Kiki, mon vieux,” I said, “you must make up your mind to do as I did and jump. Remember that you are a Canadian, and every self-respecting Canadian should know how to jump as soon as he is born.”

I delivered this kind invitation from the ground and I urged him on by pulling on the reins. Kiki was not at all frightened. He came to the edge of the car, snuffed the air, carefully calculated the distance, bent lightly on his hind legs, and jumped to the ground without a flutter.

“The ... first Colonials?” the military commissioner said to me. “I don’t know exactly,[3] but you’ll find it somewhere along twenty or thirty miles to the east at Proyart or Harbonnières, or perhaps at Morcourt. There’s a little of it all about there.”

So Kiki and I, in the morning mist, went slowly along roads covered with snow and grease in search of the second company of machine guns.

Proyart is a small village hidden in a hollow of this plain of Picardy which from a distance resembled a well-stretched, vast white carpet. Here the villages are sheltered in depressions and one only sees them when he reaches the level of their steeples. It was at Proyart that altogether accidentally, thanks to a sign about as large as my hand and already partly rubbed out, I found the staff of the ... first Colonials.

An orderly condescended to move a few steps and point out to me at the end of the street to the right the billets of the quartermaster of the second company of machine guns.

There was a court—a sewer, as a matter of fact—which was completely filled by a pool of filth which left only a narrow passage of a foot or two by each wall. In a corner was a tangle of barrels, farm implements, and broken boxes,[4] and on that a mass of wet straw, manure, snow, and mud.

At the farther end of the court was a small door with glass panels—with a glass panel—for only one remained. The spaces were conveniently filled by thick layers of the Petit Parisien, Matin, Le Journal, Echo de Paris, the great dailies which arrived intermittently at Proyart.

I went in. Kiki wanted to go in, too, but the door was low and he was carrying his complete pack. Inside was a ruined kitchen. The chimney still remained, and there was a large table made of a door stretched on two barrels, which took up the middle of the room. In each corner, against the walls, were improvised beds, straw mattresses, and heaps of clothes under which I surmised there were bodies.

“The door, nom de Dieu!” shouted a voice.

In front of the chimney was a man struggling desperately with a fire. The watersoaked wood refused to burn, and the man flooded it with shoe grease, which, when it melted, threw out jets of yellow flame and filled the room with a pungent odor and smoke.

“The door, the door! What did he tell you!”[5] cried in different tones voices which came from the heaps of covers.

It was true that a breath of cold air and a swirl of snow had rushed into the smoky dark hall when I came in. I shut the door and asked,

“Is this the second company of machine guns?”

“What of it? What do you want of the second machine guns? It’s here. And after that what do you want? Papers, again? Zut! They have no idea of bothering people at this hour. Leave them on the table and come back in half an hour.”

This diatribe emanated from a pile thicker than the rest, in the chimney corner. At this obsession of papers, of lists to be signed, I guessed he was a sergeant or a quartermaster, and I kept on:

“Don’t worry. There are no papers. I am the mounted intelligence officer attached to this company.”

“M ...!” shouted several voices in the four corners of the room, while I watched arms and muffled heads rise up.

“Mince! So we have a mounted officer now! Wonderful! They’re certainly fitting us out in style. What won’t they do next? Then, that’s all right, vieux. Come on in and let us see you. And you have a horse? Where is your horse? Bring him in; make him come. It must be cold out in the court.”

The first burst of curiosity soon passed, the torrent of words exhausted itself, and the forms which had stirred a moment ago quieted down anew. A more peremptory voice now started in shouting invectives at the orderly who was still struggling with the rebellious wood.

“Say, Dedouche. Do you think we’re Boche sausages that you want to smoke us out? Don’t you know anything? We’ll have to wear glasses. That’s no way to light a fire. What did you learn when you were a boy?”

“The grease is full of water and won’t even burn.”

“Use the oil in the lamp, then.”

The first result of the immediate execution of this order was to fill the room with a black stifling cloud which was enough to make one weep. In the middle of this smoke the orderly, Dedouche,[7] coughed, spat, sputtered, while I heard him storm:

“In God’s name, how that stinks! How that stinks!”

The quartermaster, doubtless on account of the smoke and the smell, now deigned to get up. He was a young man, large, light complexioned, and his checks were red and fat. He had just a suspicion of a moustache. His ears were hidden in a cap which had wings that pulled down. One could scarcely see his eyes they were so puffed out with sleep and smoke.

“So you’re the intelligence officer? Sit down. Dedouche, make a cup of coffee. I’ll make a note of your transfer, and then you can try to find a place for yourself until the lieutenant comes. Oh, you’ve time, you know. He never comes before ten o’clock.”

“But, Quartermaster, it’s nearly ten now.”

“No, you’re joking. Ten o’clock. My word, it’s true. Oh, there, get up all of you. It’s ten o’clock. And that salaud of a Dedouche hasn’t lighted the fire. Come, come, hurry up, the lieutenant is coming!”

And as though this were the magic word, the[8] lieutenant came in, leaving the door wide open behind him. It was time; they were almost suffocated.

The lieutenant was a large man, thin and well set up. His bearing indicated resolution. His brown hair was cut very short, according to the regulations. A close-cropped black moustache streaked his sunburned face. The general effect of his personality was that of a man cool and headstrong.

“Oh, he has the coolness of a Colonial,” the machine gunners repeated ad nauseam.

“Isn’t there any way to get you up?” exclaimed the lieutenant. “You ought to be ashamed of yourselves. It’s after ten o’clock.”

Then he saw me through the cloud of smoke and questioned me with a glance. The quartermaster broke in before I could reply,

“It’s the mounted intelligence officer, Lieutenant.”

“Oh, good!... Good morning.... Welcome.”

He extended a large, vigorous hand which confirmed the first impression of his personality—frankness and will.

“Have you found a place for your horse?” he asked.

“Not yet, Lieutenant. I’ve just come.”

I pointed out Kiki through the door to the courtyard where he waited, stoically and calmly, under the snow. Perhaps he remembered the times not long ago that he waited for hours at the doors of the ranch under more wintry winds. Perhaps he imagined that he was still waiting for the rough Canadian pioneer who tarried for long discussions about business, warming himself the while with whiskey. At any rate Kiki waited stoically and quietly. He scarcely condescended to welcome us by a glance when I presented him to the lieutenant, who stroked his head.

“This is Kiki, Lieutenant. I don’t know his real name, for his record bore only his number, but that fits him and he seems to like it. He is a Canadian, seven years old, thin but strong, very gentle and a good jumper.”

“He’s pretty. Come along. We’ll put him in with mine. They’ll get along all right together.”

So I took Kiki by the bridle and the lieutenant and I went along talking, until we reached an[10] improvised stable where the officer’s horse and his groom were quartered.

Zèbre was a great brown horse, with a huge, calm face. Everything here certainly gives an impression of calmness.

I took leave of the officer for the time being and returned to the quartermaster’s, where a steaming soup and scalding coffee were waiting for me. It was nearly noon and I had eaten nothing hot for the last forty-eight hours. It was four above zero and it was time.

I was seated under a shed of loose boards in the courtyard of Cantonment No. 77, and just tasting some excellent macaroni which the cook had warmed up for me, when Dedouche, the orderly, came to find me.

“Say, Sergeant,” he asked, “are you the intelligence officer?”

The title of “sergeant” sounds strange in the ears of a cavalryman, and I felt a little hurt in my esprit de corps; but I at once answered Dedouche’s summons, for the orderly, in spite of being at the beck and call of everyone, enjoys a certain prestige. He has a real importance, small though it be, but an importance which carries weight when he gives his opinion in the discussions of the “little staff” of the company.

This staff is the household of the quartermaster’s billets. With some slight differences it is in general composed of the quartermaster-sergeant,[12] lacking a sergeant-major which companies of machine guns rarely have, a quartermaster-corporal, an adjutant and a mess corporal. I was admitted to the honor of taking part in the discussions of the staff on account of the detached and unusual character of my duties.

But Dedouche was summoning me. I turned and observed him leisurely. Dedouche is an excellent fellow. Without even knowing him one would guess it at first glance. He is good-natured, never in a hurry, no matter how urgent his errand, and indifferent alike to blows and invectives. He smiles under torrents of abuse and threats of the most terrible punishments, and does his duty as man of all work silently. In a word, he possesses all the qualities inherent in his duty. He is tall and spare; his face is beardless and sanctimonious; his eyes smile, but they look far away under his great round glasses with their large rims. All in all Dedouche looks like a lay brother. To complete the illusion, when he talks he has a habit of thrusting his hands into the large sleeves of his jacket and lowering his head to look over his spectacles. In civil life Dedouche was an assistant in a pharmacy in one[13] of the large provincial cities. He knows the art of making up learned formulae. His long slim fingers manage the most fragile things with skill, and his grave voice is accustomed to the mezzotints of the laboratory.

“Yes,” I answered at last, “it is I.”

“The lieutenant wants you.”

I gulped down my plate of macaroni in two mouthfuls, swallowed the coffee which the cook, already attentive to my wants, held out to me, and followed Dedouche the two hundred yards which separated us from the billets.

Two hundred yards is nothing, and yet it is a world. In less time than it takes to tell it I learned a mass of things from Dedouche.

First, what part of the country we are from. The ... first Colonials was organized in the South. So, in the hope of finding in each newcomer another “countryman,” Dedouche asked the new arrival at once,

“What part of the country are you from?”

He had some doubt about my reply. A Hussar of a regiment with an unknown number, who had given little opportunity to study his accent, might be a man from the North or the East. “One[14] never knows with these cavalrymen,” he seemed to say, “they’re so uncertain.” So he changed the form and varied his traditional question somewhat,

“You’re not from the South, by chance, Sergeant?”

At this repetition of his offense about my title, I thought that I ought to slip in a discreet observation, so I said,

“In the cavalry, my friend, the sergeant is called ‘maréchal des logis.’” And then having satisfied my slightly offended esprit de corps, I replied, “Yes, mon vieux, I am from the South, in fact from the Mediterranean, from L’Herault.”

“How things happen!” exclaimed Dedouche. “I’m from Le Clapas.”

Le Clapas is the nickname given to Montpellier in the territory. And at that there came all at once a bewildering flow of words. Dedouche began to tell me, mixing it all up in an incredible confusion, about his birthplace, his adventures, his former regular occupation, in the depths of a pharmacy in a small street under the shadow of the University, his transfer from the auxiliary to active service, his wound in Champagne. All[15] this was interspersed with frequent exclamations and repetitions, “Say, tell me, Maréchal, will this war ever be over?” and then regrets for his home land, “Say, tell me, Logis, wouldn’t it be better down there in the good sun?”

In these different attempts to get nearer to the term “maréchal de logis,” I observed Dedouche’s obvious good will, but what interested me most was a little advance knowledge about the company.

So Dedouche sketched in a few words a picture of it, which was absolutely accurate, as I was able to appreciate later.

“The lieutenant is a very chic type. No one would think to look at him that he is from the South, too. He appears cold and hard, like that, but it’s not natural; he puts it on. He’s good-hearted at bottom. He’s a Basque and isn’t afraid of anything. You ought to have seen him in Champagne at Massiges. Oh, and then we have besides his fellow countryman, Sub-Lieutenant Delpos, a blond. He’s not here now; he’s down at Morcourt with the echelon. He’s a type too, not stuck-up, but he’s agreeable and good-humored.

“Oh, those in the billets,” Dedouche sketched with a vague wave of the hand, as if to say something like this: “They’re of no importance; they’re brothers, friends, and not worth talking about.” Perhaps his gesture meant something else, but that’s what I thought it meant.

And as if he were responding to my implied question, he went on:

“—there is only the drummer who’s from the South, too; he’s what they call the ‘quartermaster corporal,’ I don’t know why. He’s a good fellow, but he does not talk. At least he only talks rarely, and he’s from Marseilles, too; no one would think it to see him. He makes me mad most of the time.

“Oh, the rest! The corporal of infantry is from Paris. I don’t know him. He only came five or six days ago. He hasn’t told us anything yet; he only sings. And what songs! Good God, they’re enough to make one blush!

“The juteux—the adjutant,” interrupted Dedouche, for he rarely used slang. With the exception of “pinard” and “tacot,” which have become hallowed and have taken an official place even in the most refined language of the armies,[17] Dedouche rarely used a vulgar or misplaced word in his conversation. This was not because he was opposed to it nor from false modesty, but because his occupation as a “scientist” had given him the habit of using good language.

“The adjutant,” went on Dedouche, “he’s not an adjutant. He’s a brother, a father, a friend, a man, what! Never a word of anger, never a punishment, always agreeable and kind. And in spite of that he’s had a career. He’s been in Morocco, China, and Madagascar, and no one knows where else. He’s been in the service eleven years, but you wouldn’t think it to look at him.”

This running biography brought us to the open door which framed the lieutenant’s tall figure.

“Say, Margis” (the lieutenant knew his military terminology and this abbreviation was not without zest), “are you rested from your journey?”

“I wasn’t tired, Lieutenant.”

“How about your horse?”

“No more than I was. Do you think that after three days stretched out on the straw in his car, without moving ...?”

“Then, if you are willing, we’ll both go to the echelon.”

“All right, Lieutenant.”

A question must have framed itself on my face, for he added almost at once:

“Yes, the echelon, the fighting train, the cavalry. You’ll be more at home there. We left it below at Morcourt, seven or eight miles away, on account of the shells that fall here sometimes. Horses, you know, cost more than men, so we have to economize them. It is understood, then? We’ll go about noon. Saddle both horses. Meet me here.”

Then he strode off and joined a group of officers who were coming up the main street of the village to the church.

Dedouche was already full of attention for me—just think of a man from home on the “little staff”—and he now burst forth eagerly:

“Don’t trouble yourself, Logis. I’ll tell the groom to saddle the horses and bring them here.”

The smoke still persisted in the dark, littered confusion of the room, but combined with it now was an odor of burnt grease mixed with the moldy smell of a ragout with onions and strong[19] cheese. In addition, spread out on the table, were the remnants of a meal, which had just been finished, the rolls, the account books and reports.

The quartermaster-corporal, the silent fellow from Marseilles, immersed in reading Le Soleil du Midi, did not even condescend to look up. In response to my friendly good-by, he let a scarcely perceptible “adieu” slip through his lips.

The quartermaster was stretched out on a dirty mattress thrown on the ground, and juggling two packages of English cigarettes, while he sang at the top of his lungs—and what a voice he had!—the latest song:

This intellectual refrain must have given him extreme pleasure, for he began it again and again without any interruption.

“Well,” I said, “judging from the looks of things, you aren’t often disturbed here?”

At this the drummer cast me a searching look, cold, disdainful and commiserating, as much as to say to me,

“One can see that you’ve just come!”

As for the quartermaster, he replied to everything in the repertoire of the Eldorado. Without stopping his juggling, he shouted at me in his amazing voice:

He was going on when the infernal noise of some aerial trolley tore through space.

“Attention!” he cried, without moving from his mattress. “There’s the Metro!”

Almost at the same moment, a great shell, a “310” at least, burst in the court of the house opposite, demolished the roof, and crushed a dozen horses.

The adjutant was just crossing the street and he stopped at the door to estimate the damage.

“They missed the steeple again,” he said, with a disdainful shrug for the Boche artillery.

And Morin, the drummer, by way of commentary, without interrupting his reading:

“Close the door. If they send any more shells, that will make a draft.”

From Proyart to Morcourt is five miles by a crossroad which in its many curves and windings cuts across trenches, communication trenches and barbed wire.

The snow had stopped, but it still covered the ground, the trees and the farms with its regular white covering. The communication trenches showed black on this vast screen.

The crows circled in innumerable flights and sought in vain for the carrion which had been so abundant for months and which, to-day, was buried.

We went along, boot to boot, slowly, for the roads were slippery. Kiki wanted to dance about, for the keen air made him lively. But Zèbre’s sedateness dismayed him, and Kiki wisely ranged alongside and regulated the pace by his.

The lieutenant talked but little—a few detached words, chopped phrases, about the company,[22] an observation on the weather, a reflection on the horses.

The road was almost deserted save for a few Territorials, muffled in their sheepskins, who dragged along their heavy wooden shoes which were made even higher by a thick sole of snow. From time to time a company wagon, driven like an express train, grazed us with its wheels and splashed us with mud.

Then, abruptly, without having had to climb the slightest hill, we saw Morcourt, as one sees suddenly from the top of a cliff the sea at his feet, in the midst of the thousand windings of the Somme, of the canal and the turf-pits. Morcourt is a village scarcely as large as Proyart, and like it hidden in a gully sheltered from the winds on all sides, and also like it, hidden under the snow.

A blacksmith had set up his forge in the open air against the walls of a tottering tile-kiln. All around the snow had melted in great black puddles where the waiting horses had pawed the ground. The smoke from his fire rose red-tinted and dark in the heavy air which seemed to muffle the ring of the hammers on the anvil.

We come to a stop before a house nearly in[23] ruins, whose tottering remains are a constant menace. A corporal rushes out—nimble, short and thick-set, a small Basque cap binding his sunburned forehead—and then some men come from the neighboring stables.

The houses in the country which were invaded for a short time and in which troops have had their cantonments for long weary months all look alike. Their doors and windows are gone, but these are replaced by tent canvas.

The drivers of the echelon and the war train in the machine-gun companies are nearly always sailors, the older classes of the Territorials, who after many changes have been assigned to the Colonial regiments. No one knows why, but it is probably because the bureaucratic, stay-at-home mental worker finds some relationship between the Colonials and the sea. And so they make these men, accustomed to the management of ships, infantrymen, or drivers, or even cavalrymen. But with the unfailing readiness and the ingenuity of their kind they make up so much for all that, that far from appearing unready and badly placed, one would say that they were veterans already broken to all the tricks of the trade.

Their long ship voyages and the necessities of critical hours have taught them to replace with the means at hand most things in material existence. From an old preserve box and a branch of a tree, squared and split with a hatchet, they make a strong and convenient table. With a scantling and a bit of wire lattice taken from a fence, they make an elastic mattress which, covered with straw and canvas, becomes a very comfortable bed.

The sailor is carpenter: the hatchet in his hand takes the place of the most ingenious tools of the joiner; painter: he has painted and refitted his boat from its tarry keel to the scroll work of the bulwarks and the figures and the beloved words they put on the stern; mender: he mends his sails and nets artistically; cook: during the long days at sea on his frail craft with its limited accommodations, he makes the most savory dishes from the fruits of his fishing and a few simple spices. His qualities and his knowledge are numerous and wide: astronomer and healer, and, as well, singer of beautiful songs which cradle his thought at the will of the rhythms, as the sea rocks his boat at the will of the waves.

But in this multiplicity of talents he lacks that of a driver, and what is more, a driver of a machine gun. That is a job which combines the heavy and the mountain artillery. A machine-gun driver should be able to drive in the saddle the leading team of horses and put the heavy caisson of ammunition through the most difficult evolutions. Again, he should be able to drive on foot the mule loaded with his pack-saddle and through the most impossible and sometimes the most dangerous paths.

We had scarcely begun to swallow a cup of thick, smoking, regulation coffee in a room of the cantonment, furnished with special skill, when Sub-Lieutenant Delpos—smart, carefree, smiling, a cap on the back of his head and a song on his lips—arrived.

Dedouche’s description seemed to me to be exact. He was indeed a very young man, very quick, very blond and very gay. He was already an officer when others of his age had scarcely left college; he was already a hero counting in his active service a thousand feats of prowess when his rather sceptical contemporaries were content to read about them in books. Open merriment[26] shone in his eyes. He had gained his promotion in the field far from the stifling atmosphere of study halls. Yesterday he was still a sergeant in Madagascar, Senegal, and Morocco; to-day he is an officer who has fought since the beginning of the Great War; to-morrow he will be a trainer of men. He knows them all; many are his old bedfellows or companions of the column. His remarks are keen and unrhetorical and they please the men. They love him and fear him; they are free with him and respect him. They know that he understands his trade perfectly and that they can deceive him in nothing.

Our introduction was short and unceremonious. A man brought on the table a bottle of very sweet Moselle wine, which is christened at the front “Champagne.” It was one of those wines which make up for their qualities by such pompous appellations and well-intentioned labels as “Champagne de la Victory,” “Champagne de la Revenge,” “of the Allies,” “of the Poilu,” “of Glory.” They are all equally bad, but they make a loud noise when the cork is drawn and most of the wine flows away in sparkling foam.

We drained our cups to the common health,[27] and to the success and certain glory of the company.

Then the lieutenant, who has memories of the drama, said in a voice which recalled the tones of the already classic Carbon de Casteljaloux, his neighbor,

“Since my company has, I believe, reached its full number, shall we not show it to the logis, if you please?”

Under the rays of an anemic sun which had waited until the hour of sunset before it deigned to appear, we made a brief visit to the echelon.

First the roll; five corporal muleteers or drivers: Raynal, the owner of a vineyard in Gironde; Liniers, a salesman of wines and spirits and a great elector in the Twelfth Arrondissement; Glanais, Bonecase, Glorieu, carpenter, vine-grower, and farmer—and none of them had ever managed a horse in his life.

And the men—one in fifty is a cavalryman—but that one is perfect. He was trained at the cavalry school at Saumur; trained horses and bred them, so they at once turned him over to the echelon, where he had to lead a mule by the bridle. That, of course, was a reproach to his old trade,[28] so in default of any other satisfaction it taught him the philosophy of resignation and peaceful blessedness.

The cavalry!

“Oh, the cavalry, that’s been posing five minutes,” said Sub-Lieutenant Delpos—he was extremely fond of that expression.

There were horses and mules varying in age from five to seventeen. They were all sensible, settled down, their legs somewhat worn out, and more accustomed to the hearse than to a caisson, and more familiar with the song of the worker than with the roar of cannon. They were all gentle, only demanding oats and straw; some with their bones sticking out of their hides, while others were still sleek and shiny from their warm stables and fresh straw; all unconscious of what awaited them on the morrow.

One of the mules was a veteran, an enormous, cunning animal. His hair was short and rough, and in places there were great patches where the hide showed. His skin was hung on a projecting framework of bones, and, although he was well fed, he was very thin—with a thinness so unyielding to rations that it was impossible to[29] get him fat. His head was that of an epicurean philosopher with deep mocking eyes. This was Chocolate.

Chocolate is beyond the time when he has an age. The oldest soldiers in the regiment have always known him, even at Marrakech and Rabbat in Morocco.

Chocolate has made many campaigns during his active service and he has received several wounds as well.

The story goes that one day in Morocco Chocolate got loose from the bivouac, and started browsing on the grass and wild oats in an ambuscade—between two fires. Absolutely indifferent to the crackling of bullets which he had known from infancy, he continued to lop off the plants until the pernicious bullets began to graze his skin. Then he stretched out at full length in a hollow in the sand and browsed on the grass within reach of his teeth, while he waited the end of the adventure. Then he went back to the bivouac in search of a pail of water and a bag of oats.

Now Chocolate is the file leader. He indicates by his example to the horses whom the pack-saddle[30] galls that the best way of carrying it is to avoid romping to the right and the left, shifting about, and trotting, in fact, all movements which misplace the saddle or wrinkle the skin beneath. The secret is to work soberly, slowly and at an even pace.

Chocolate belongs to a family of mules which ranks high in history. The broad, rounded backs of his ancestors have borne debonnair sovereigns, preacher monks, magnificent Sultans and Sancho Panzas, baskets of vegetables and cans of milk. To-day Chocolate, their descendant, carries an infernal instrument—a machine gun. But what matters that to him? The road rolls on before him and he follows it. There are oats at the end, to-night or to-morrow, what difference does it make?

“He is cool,” the drivers say. Coolness is the great secret of the Colonials.

Coolness, indifference to danger, bad weather, adversity, obstacles, death—no nervousness, no useless bursts of anger, no dangerous hurrying, no false starts. It is necessary to go—they will go—they arrive. That is all.

Dedouche brings me a note to sign for on the report book. It reads:

“The non-commissioned officers will assemble their sections in the courtyard of Cantonment No. 77 at 2.30. Each gun captain will present his gun. Service marching order, with masks and arms.”

I sign mechanically to please Dedouche, who thinks he is showing me a special favor by offering me the first reading of all orders and reports. But this one interests me but little, for I have neither arms nor guns to present. So it is as a spectator that I am present at the lieutenant’s inspection. This time I shall see the complete company.

I find myself at the appointed hour at Cantonment 77.

One must have lived in these remains of villages, which persist in standing, near the lines[32] to have an exact idea of what they are. In these villages furious combats have taken place in the streets, from house to house, and for two years they have been occupied and overpopulated—a hamlet of one hundred and fifty inhabitants often serves as a cantonment for ten thousand men—by men of all arms of the service, from all regions, of all colors.

It is not ruin in all its tragic horror and majesty. It is worse.

It is something which appears to want to live, but which a latent leprosy eats away. Often there are traces of shells, the splatter of bullets, the marks of fire; the roofs may have fallen in from the recent shelling, but even yet the general effect is that the houses on the streets are still standing.

The fronts of these houses, made of straw and mud, with only a large door swinging on its hinges, are whole. Of course the mud has often been scratched in long, leprous wounds, and the straw tumbles out leaving the bare skeleton of worm-eaten wood; and, besides, the windows are without the glass, which has been broken to bits by the explosion of shells, and which is replaced by[33] bits of paper or by calendars. But the real ruin is inside.

Here is the work of the carelessness and negligence of the wandering multitudes who pass that way, who arrive at evening, tired, muddy, wet, who fall asleep on damp straw, cut to pieces and crawling with vermin, and who go on the next day, or three days later, leaving as a mark of their passing a greater stench and a greater dilapidation.

The ruin is inside. It is not the beautiful ending of destruction by fire, but the slow death by cancer which eats away, by gangrene which mounts from the cattle sheds to the stable, from the stable to the barn, and from the barn to the hearth. And at last a day comes when the front alone is standing on the ruin of the annihilated house, and then men who are passing by, seeing that it is tottering and dangerous, cut it down with blows of the axe and chop the wood into bits for their little needs.

And so these houses die: houses which under their humble appearance had great souls palpitating with life, where lives were born and passed their years; where joys and griefs exclaimed and[34] wept, where the peasant, the son of the soil, drew from this soil, the generatrix of strong races, the re-vivifying harvests which he stored away in the barn which to-day is dead.

Whole villages and great villages agonize in this way through months of wearing away, and their end is no less terrible, no less majestic, no less pitiful than of those villages with glorious names which the wrath of shells beats into dust.

Cantonment 77 is made up of those houses which waste away. Between the fragile walls, notched by an empty barn and a fallen shed, opens a courtyard. Filth spreads out in a vast pool on which float among the refuse a pile of garbage, boxes, the waste of cooking and greasy papers.

In the corner of a recess open to every wind, on piles of bricks held together by iron bars pulled from the window sills, the cook has set his pots and bowls in line. His fire of wood so green that the sap oozes out licks the already blackened walls with its long flames.

All that offers even a precarious shelter—a roof—is occupied by the men who crowd in there on old, filthy straw, and on the meager rations of fresh straw, often too fresh. And as the tiles[35] and thatch let the rain filter through, they stretch above them strips of tent canvas.

Oh, blessed canvas! To what uses is it not put! It serves as a roof against bad weather, the rain and snow; a protection against dampness, mud and vermin; planted on two stakes, stretched to a door casing, it protects the fires for cooking from draughts; in the more comfortable cantonments in the rear, where the straw is clean and abundant, where the men are at last able to take off their shoes, and their muddy leggings and their trousers heavy with dampness, it serves as the bed clothes; and, finally, at the last hour it is in the tent canvas that they collect the bodies with their torn and shattered limbs. It serves as shroud and coffin. And, faithful to its rôle, it is the last shelter.

The men began to arrive by groups almost in order, at any rate as much so as the littered ground in the courtyard would permit. They assembled by sections in a half circle around the pool of filth. It was certainly a picturesque sight when, at the command “Attention,” these men mounted a faultless guard around this fetid pool, where, among papers, tossed about and dirty, and[36] box covers, there floated, bloated and fetid, all kinds of carrion, the rats of the last hecatomb.

Near the doorway on the largest and cleanest part of the courtyard the eight machine guns were drawn up in line.

Eight machine guns, the armament of the company.

Eight guns, so small, so fine, and such bits of workmanship, that one would think to see them that they were a child’s playthings.

The machine guns appeared very coquettish and pretty as they rested on their bluish-gray tripod, with their steel barrels well burnished even to the mouth of their muzzles. They hardly appeared at all threatening with the polished leather of the breech, where the bronzed fist of the gun layer stood out in graceful designs, and the attenuated round and svelte circles of the radiator.

Remains of Villages near the Lines See page 36

And the machine gun is a coquette, too. Under its appearance of delicacy and grace it conceals a terrible power of domination and strength. Yet it hurls pitiless death without noise, with a rapidity as furtive as a shout of laughter, with a tac-tac which is scarcely perceptible and which is no more[37] menacing than the familiar tac-tac of the sewing-machine or the typewriter.

And the machine gun is a coquette, too! Fashioned like a work of art, the brilliancy of its polished steel and the voluptuous roundness of the brass invite caresses. Its shots come from they know not where, since they can see nothing—a bush is sufficient to conceal it; light, it is here one minute and there another; it is not visible until one is almost upon it, yet its shots are fatal at some miles.

It is delicate and costly, needing a hundred things for its adornment, skilled care for its toilet and a hundred men to serve. Is not the machine gun a coquette?

As the Company Casanova is of recent formation it received an entirely new armament of the latest model. The guns are built on the Hotchkiss system—the last word of perfection in war. They are light, scarcely fifty pounds, and they are easy to manipulate skilfully. The rapidity of their fire is extreme, more than five hundred shots a minute, and their adjustment is such that they can fire on the most varied objects. First, there is blockade fire, which concentrates all the shots[38] on a narrow point; then the sweeping fire, which sweeps the whole of an extended field; and finally, indirect fire, which hits its designated target with mathematical precision, at the same time concealing the source.

The machine gun is the little queen of battles. One may smile to look at her, but one shudders when he thinks of her ravages.

And the men are proud of their guns.

I observe them while the lieutenant speaks to them and their eyes look alternately at the lieutenant and at their respective guns. They know their gun; they love her; possess her. They have confidence in her, and it is she who defends them.

To-day there are about one hundred and fifty men grouped in the same specialty, from all regions, all regiments, all arms, who have come after more or less lengthy stays in the instruction camps at Nice, Clermont, and La Valbonne.

Their specialty has created among them a certain sort of affinity, a family characteristic. Machine gunners are an element apart, a sort of élite. In their ranks there is a certain homogeneity which comes from the practice of the same competency which is nearly a science. They feel[39] somewhat superior to, at least different from, the ordinary companies.

They appreciate the worth of their distinction and scarcely ever associate with other troops. The companies of infantry are swamped in a battalion, while the companies of machine guns are isolated, autonomous, directly dependent on the commanding officer, and they enjoy an absolute initiative in a battle. Finally, they are not anonymous or numbered; they are not called the fifth, seventh, or the twelfth, but the “Company Casanova,” as they once said Royal-Piémont or Prince Condé.

Then, too, there is their insignia. The insignia is the bauble, the jewel, of the soldier. It is a real satisfaction to have something on the uniform which distinguishes one from his neighbor. To such a point do they carry this that many cannot resist putting on insignia to which they haven’t the slightest right. And none of the insignia arouses greater envy than the two small intersecting cannons of the machine guns.

It takes one hundred and fifty men, two officers, ten non-commissioned officers, and sixty horses to serve, supply and transport the eight small guns,[40] one hundred and fifty men trained and inured to hardship. There is none here who has not been in several battles and received several wounds in his active service. There is none here who has not a good record. When said of one that means little, but when said of all it is worth telling.

There are artillerymen, cavalrymen, and sailors who have become foot soldiers through their different changes; and not only are all arms represented, but all professions, all classes and all temperaments. Jacquet, a poet and musician, a dreamer with an exquisite soul, is an accurate gun layer. Finger drives milk wagons in Paris, but with his gigantic hands he manipulates with delicacy the wheelwork of his Hotchkiss. Millazo, who behind his counter at Hanoï showed gracefully the jewels of Indo-Chinese art and learned at Lure the meticulous art of watchmaking, now manages a “sweeping” fire as calmly and accurately as he used to mount a spiral spring on its microscopic pivot. Corporal Vial, who used to verify accounts in the luxurious banks on the Riviera and handle tinkling gold and checks, here shows that he knows the science of fire and his machine and leads his squad with authority.[41] Charlet drove the heavy locomotives on the railways of the North; Gamie regulated the powerful looms in the textile factories, and they both owe to their knowledge of mechanics their duties as range takers. Imbert was a fisherman and, as he knows how to cook a savory bouillabaisse, he is assigned to the difficult rôle of cook and acquits himself conscientiously and well. However, Chevalier, an expert in geometry, who for twenty years grew pale in profound studies of logarithms and co-ordinates, here assumes the duties of mess corporal, and discusses with asperity the supplies and remarks pitilessly on the regulation cup of wine and the mathematical pounds and ounces of mutton, lard and beans.

In spite of what one might think, this odd collection of men is as homogeneous as could be imagined. This comes from the fact that above all this different knowledge is a uniform purpose, because all these multiple alliances tend toward a common end which is incarnated in their chief, a man from the South, who is expansive and impetuous, but who curbs his temperament under the rigid calm of a man from the North, one of the common people, a son of the soil, who has[42] risen to the rank of officer, and a commanding officer at that, solely through persistency and courage.

When the lieutenant had finished his rapid but close inspection, and had examined with the eye of a connoisseur the condition and repair of the guns, he took in the whole company with a look, for it is his work which he commands with firmness and which he loves. He is already going, after addressing a few remarks to the adjutant and the classic, “All right. Break ranks,” when a man steps out of the ranks and comes towards him.

“Lieutenant, the company is now completely equipped and armed, but there is, however, still something lacking.”

“Indeed,” replied the lieutenant, “and what’s that?”

“Its marching song.”

“Its marching song! Have you chosen one?”

“Chosen one! Oh, no! We have an unpublished one, as new as the company itself, composed for us and created by us. Will you do us the honor of listening to it?”

“Will I? The devil. I ask it; I demand it. I want to learn it, too. Go on. Start it!” he exclaimed.

And then Gaix turned towards his comrades and began to sing in his great deep baritone voice our marching song, “Ma Mitrailleuse,” which each section had learned secretly and which they sang together for the first time to-day.

On a rhythm taken from some war march, some one had composed simple words, which were nevertheless image-provoking and vibrant, where the alternating motet “Ma Mitrailleuse,” sung in chorus, sounds like a bugle call.

This marching song is one of those which engrave themselves at once on the memory and in the heart, which are never forgotten, for in their accents are rooted the strongest impressions of the hours lived in the simple brotherhood of arms, the memory of dangers encountered together, the pride of victories, and the pious homage to those who sang it with us and whose manly voices were silenced forever in the night of battles.

And I find in writing it the same deep stirring emotion that I experienced when I first heard it.

MA MITRAILLEUSE

When the last accents, sung by the men at the top of their lungs, died away, there was silence and I looked at the lieutenant.

He was seated on a staircase, with his head leaning on his clenched fists. He had listened to the whole song, and now he remained for a moment as if waiting. And when he stood up his eyes were slightly red and his lips concealed under a smile the impress of intense emotion.

“It is good,” he said, “very beautiful, my friends, and I congratulate you all. Your song is admirable, it will go with us everywhere, and we will lead it to victory. But who is the author? There must be an author. The devil, there must be an author!”

There was a moment of silence as if each one hesitated to reply, but a big sergeant cried out in a stentorian voice:

“A ban for the author, Lieutenant Delpos, and a couplet for him besides.”

Then the men broke all alignment, pressed[46] around their young sub-lieutenant, joyous, proud and blushing with pleasure, weeping with joy, and burst out at the top of their lungs, with indescribable feeling, which showed all their strength, their will for victory and their unbreakable confidence:

Then, amidst the applause and the “vivats,” the lieutenant embraced his young friend vigorously and said:

“Nom de Dieu! You didn’t tell me that you were a poet. I congratulate you.”

And taking him by the arm, he went off joyous, skipping like a gamin, taking up again the inspiring refrain:

One evening the lieutenant said to me a little after dinner:

“To-morrow, at four o’clock, we’re going to the first line trenches to find positions for the machine guns. The section leaders are coming, and if you want to come, you’ll find it interesting.”

The selection of a machine gun emplacement is essentially a delicate task. The Germans are past masters in this art. So, in the days of attack when our artillery had made a thorough preparation and they were convinced that there was nothing left in front and we could advance without trouble, exactly as though taking a walk in a square, we found ourselves abruptly right in the fire of a Boche machine gun which had not been spotted and which was so skilfully camouflaged that it had resisted the most terrible bombardment.

It is necessary above all to find a place which commands a wide field of fire and one easy to[48] play on. It must also be easy to conceal the gun in some way, for, if it is once spotted, a shell will soon send the gun and its crew pirouetting in the air, unless they are forewarned by a shot too long or too short, but whose destination is unmistakable, and so have time to move.

It was scarcely daylight when we assembled in front of the lieutenant’s quarters.

A fog that could be cut with a knife limited our view to a few yards. It was cold.

Sergeant Lace is there already walking back and forth in the fog. He is always exactly punctual, anyway. He is equipped as if for an assault with his revolver, mask, and field glasses. His chest is covered with numerous colonial decorations, his military medal and his war cross with three palms.

Lace is a section leader emeritus. He is rough and harsh in appearance; he never smiles, or rarely; he is tanned from his long stay in the colonies, but he does his duty with unfailing exactness. During an attack in Champagne he found himself under the command of his brother, a lieutenant, who was mortally wounded at his side. He embraced him reverently, took the papers,[49] pocketbook and letters from the pockets of his jacket, removed his decorations, which were now relics, and resumed his place in the ranks. He fought all day, attacked a fortified position, assisted in the dangerous task of clearing a wood, and when night came, by the light of star shells under a hellish bombardment and a storm of shrapnel, he went back and brought out his brother’s body and gave it proper burial. Lace is a soldier and a conscientious one.

Other silhouettes approach and come out of the darkness like ghosts. One is Poirier, a very young man, who laughs in the midst of the worst dangers, which he absolutely ignores. Then there is big Roullé, whom ten years in the tropics did not succeed in making thin, and whose breadth of shoulder is ill-adapted to the narrowness of the communication trenches. Then Pierron comes on the run, singing a Neapolitan song. He is from Saigon and is homesick for the Asiatic nights, whose charms he is forever describing.

As the hour strikes the lieutenant appears.

We follow the main road through the fog. This leads to Lehons, a ruined village which is situated in the lines and cuts the trenches.

One can hardly distinguish the trees in the fields either to the right or the left. The dawn is silent. Nature wants light for her awakening, but this morning the lights persist in staying dim.

We hear occasionally a cannon shot, as sharp as the crack of a whip. It comes from a battery of “75’s” concealed in a wood at our side, which fires at stated intervals for tactical reasons. The shell shatters the air over our heads and all becomes quiet again.

So we walk along for nearly an hour, some grouped together while others dream away by themselves. The fog now begins to lighten and we are able to see the adjoining fields. They are torn with shell holes, the rare trees are shattered and slashed, and their branches hang down like broken limbs. In the ditches, full of muddy water, are piles of material—rolls of barbed wire, eaten by rust, chevaux de frise broken to pieces, and crossbars and round logs already covered with moss.

Suddenly, there in front of us, at two paces, splitting the fog is—the village. There are houses—remains of houses—and parts of walls[51] which through some prodigious feat of balance persist in remaining upright.

The first house on the right was apparently of some importance. The two master walls still remain in spite of the roof having fallen. Between them is a pile of stones, burnt girders, and in the middle of the heap of rubbish still stands, intact and rigid, pointing straight toward yawning heaven, the iron balustrade of a winding staircase. A great signboard of black wood runs from one wall to the other, apparently holding them together, and one might believe that they only remain upright, thanks to it. It is riddled with bullets and the flames have licked it as they passed, but one can still read the long yellow letters of the inscription:

Lodgings

Famous Cuisine Comfortable Rooms

None of us risk an ironical reflection or a mocking smile, for to-day we have become accustomed to so many strange inscriptions which in disaster are the living lie of their emptiness.

Opposite, on the other side of the road, the military cemetery shows its multitude of crosses.[52] Their number has exceeded the capacity of the site provided for it, and they have already become masters of the surrounding fields. These graves are all immutably alike, and they are built and maintained with a fraternal affection by companies of Territorials who hold the cantonments in the neighborhood.

Yes, they are all immutably alike. There is always the white wooden cross with the name of the deceased, the number of his regiment, his company and the date of his death in simple black letters. The grave is a small square, bordered by bits of tile or bricks, sometimes by planks or the bottoms of bottles. And on this humble burial place someone has planted primroses.

A bottle stuck in the ground by the neck holds a bit of paper on which is written all supplementary information as to identity which will guide the pious pilgrim of to-morrow.

Sometimes a perforated helmet or a tattered cap placed on the cross by a comrade who respects his memory tells us that the soldier was wounded in the head. One shudders at some of these helmets, they are rent so grievously.

We pass rapidly but religiously through the narrow paths between the graves. It is a sort of duty rather than curiosity which leads us to look over all these cemeteries in search of some known name, a friend’s name, so that we may pay our last respects.

But time passes. It would not be prudent to stop longer, for already above the neighboring hedge we can hear the sinister “ta-co” of the German bullets. Branches of an apple tree, lopped off by the shells, fall at our feet.

So we enter the village through what was once a street. Here for fifty yards are barricades of bricks and dirt interlaced with farm instruments and carts.

Barbed-wire entanglements which only leave a narrow, difficult, zigzag passage between them are evidences of the bitter fights which took place here.

We reach the church which is the beginning of the communication trench which leads to the front lines.

The church! There is absolutely nothing left of it. One might think that the savagery of the[54] German cannon raged with a special hate on the buildings created for rest, meditation and prayer.

The church has fallen down and the naves are now only a mass of stones on which the briers are already beginning to grow. A sort of arched door still stands at the entrance, without a scratch. It is nearly new and its brilliant ironwork seems a challenge in the midst of this destruction.

The communication trench starts on the spot where the high altar used to stand. We follow it under the ruins, through the orchards which it furrows, adjusting our steps to each other, and keeping our eyes on the man ahead.

Above our heads nature awakes; the sky appears clear now; and branches of trees with their buds and blossoms hang over the parapets.

It is five o’clock and broad daylight when we reach the proposed emplacement. It is on a knoll in the middle of an orchard which is bordered some hundred yards away by hawthorn and privet hedges. Behind the hedges are the Boche lines.

The engineer in charge of laying out the works is on the ground. He tries to profit by the only salient which permits firing on a sufficiently wide[55] sweep of ground. On the right it commands the entrance to the village by a road. We see its white windings where it unrolls through the gardens, and then it plunges into a small wood and loses itself. Opposite us the emplacement commands an entire sector.

They will scoop out the place underneath, and they will keep the green shell of grass and bushes which make the most fortunate and natural sort of camouflage. A communication trench grafted on the main trench from the church will give access to it.

Orders are given rapidly, measurements are taken, and the tasks laid out. It is hardly expedient for us to delay in this corner, for our movements would betray our intentions, and already bullets, which are by no means spent bullets, cross above our heads singing their unappreciated buzz.

We make our way back through the trench.

In the village the men belonging to the supporting columns have left their lairs and are attending to their usual occupations. Some of them are washing their clothes in the watering-trough in the square and singing as they wash. The company barber is installed near the fountain and[56] the men form a circle about him as they wait their turn. On a butcher’s stall of white stone a cook is cutting up a quarter of beef into equal rations. Only two hundred yards from the enemy the village has taken up almost its usual existence again. These men are not afraid. At the sound of the first shell they jump into their cellars, which are amply protected by earth and boards. But they already have their customs. Shells only come at the hour when the supplies are brought up, and not always then, for the shelling doesn’t occur regularly every day. The enemy doesn’t waste munitions on a village he knows is so well destroyed.

The fresh air and the long road have set our teeth on edge and given us an appetite. We halt to break a crust. Some have brought canteens of wine or coffee; bottles of preserves appear, and the improvident—I am one—pay homage to those who pass a full flask.

The sun is already high when we start back along the road.

A Poilu See page 56

The lieutenant loves a quick pace and a marching song. So at the top of his lungs he begins one of his lively songs full of expressions that[57] would have startled a growler of the Empire through their shamelessness, but which do not disturb the modesty of a Colonial at all, supposing that a Colonial ever had any.

And the section leaders take up the refrain in chorus.

Some steps behind, Sub-Lieutenant Delpos stops to light his fine Egyptian cigarette. In spite of the early hour and the uncertain weather, and with no thought of the disagreeable march through the sticky mud of the communication trench, he is dressed with the greatest care. His bright tan leggings are elegantly curved; his furred gloves are of the finest quality, and the pocket of his jacket, cut in the latest English style, shows a fine cambric handkerchief, subtly scented. And arm in arm we follow the quick pace of our comrades, while he continues the interrupted story of his latest exploit.

“Yes, mon cher, picture to yourself an exquisite blonde. I met her on the Rue des Saints-Pères....”

Yesterday evening at five o’clock we received an order to take our positions in the front line to support the attack which the second battalion would make at nine-thirty.

It was raining. It has rained all the time for some months, and we have become accustomed to the mud and dampness.

We left the cantonment at Morcourt at nightfall. We went along the towpath of the canal, across the bridge at Froissy, through the ruins of Éclusier and entered the communication trench which we knew as the “120 long.”

The silent march is accomplished with little difficulty. There is no sound of cannon. Everything is quiet. We reach our positions about midnight—four dugouts camouflaged for the guns of two sections which are to play on the sector; the two other sections remain in the “Servian” trench in reserve at the disposal of the commander.

The lieutenant examines the post established for him. Farther ahead is a communication trench which has been completely overturned and destroyed, now nothing but a great hole. Below is a big tangle of barbed wire, fascines and ripped open sandbags. We can see very well through this jumble and we are installed there.

We can make out the details of the Boche lines through the glass.

“Come. I think it will be all right. But it will be hard. Fortunately, it can’t last long.”

Then we return to the positions for a final inspection.

The emplacements which our guns occupy are round excavations about three yards across and two deep. In the middle nearly on a level with the surrounding ground is a sort of pedestal for the machine gun. The barrel scarcely reaches beyond the hole and it is absolutely invisible at a short distance. The men have proceeded to make a camouflage which resembles the character of the terrain with wickerwork covered by dirt and grass. The many inventions with which they have increased the weight of the machine guns—the shield, sights and periscope—are in their[60] places. The men disdain these additions a little and even neglect to use them unless forced to do so.

“They would only have to add a little more,” they say, “to make a ‘75’ instead of a machine gun.”

“The periscope may be of use for something. You have to try half an hour before you can see anything. I like my eyes better.”

The ammunition wagons are installed and opened; the belts are ready; the gun layer, the loader, and the crew are at their stations.

The lieutenant makes the rounds of each section, inspecting the guns, testing the mechanism, trying the weight of the munitions, taking account of everything and looking each man in the face.

“We are the last company organized,” he says. “You know that the machine gunners should be the flower of the army; don’t forget it. It is our first engagement. Try to show that we’re there a little.”

This short unpretentious harangue produces its effect on the men, who smile as they listen to it. They are not nervous now, but only slightly curious. They are not sorry to put their toys to the[61] test at last, and to shoot their projectiles at something besides the moving figures in the training camps.

When the inspection is over and the final instructions have been given, we return to the commandant’s station, and stretch out to sleep on the reserve caissons which protect us from the mud. Rifts in the clouds reveal the stars. It will be fine to-morrow. But waiting is cold, very cold, and it is impossible to sleep under such a wind. We talk.

“You’re going to hear a concert. They haven’t massed more than three hundred guns in all, from the ‘75’ to the heavy artillery, on our fifteen hundred yard front for nothing. Have you seen the ‘150’ mortars? They have some muzzles.”

Dawn appears. A light fog rises from the ground and seems thickest at the side of the canal where the German positions are. It is the coldest hour of the day and the earth of our dugout is as hard as iron; it is frozen. Instinctively I let down the ear-flaps of my cap which until now I have kept under my helmet.

“Are you cold?”

“I’m not warm.”

“A drop of brandy?”

“Sure.”

The lieutenant passes his canteen to me and as I drink the thin stream from its mouth I feel a wave of warmth.

Light comes, but it is very pale. Around us we hear the tread of feet on the hard ground and the slapping of arms across the chest.

We wait nervously. Presently we receive an order not to fire until the blast of the whistle.

Eight o’clock! Behind us, in the limpid azure, the red disk of the sun rises.

A shell cuts through the air; then another; then still another. Our artillery is firing on the Boche lines.

“Attention.” The response is instantaneous. We can still see no movement in the ranks of the infantry to our right whose rush we are to support. What are they waiting for? The men are nervous and they start to grumble.

Boom! comes the Boche’s reply.

A great mass of earth, grass and crumbled stones shoots up a hundred yards ahead of us!

Too short!

Boom! still another. Still short!

A large shell heads for us. It thunders. Where is it going to burst? The devil! It falls near our first section, to the left; then, almost at once, another, a little to the right. Are we spotted? We haven’t fired a cartridge yet, and there isn’t an aeroplane or sausage in the air.