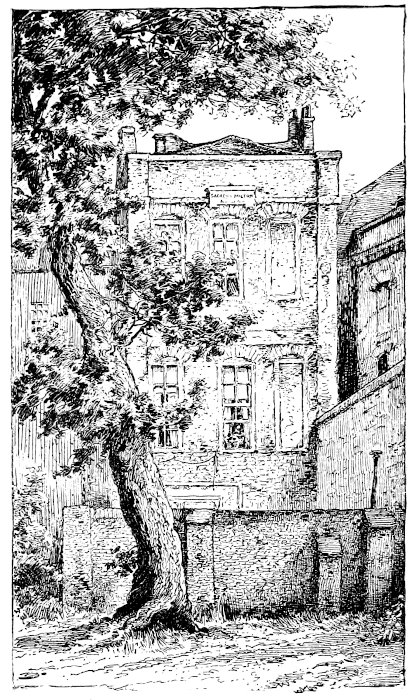

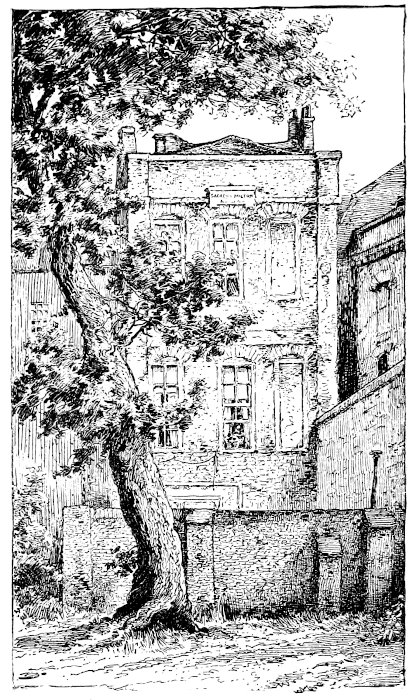

Milton’s house No. 19, York Street, Westminster, occupied by Hazlitt 1812–1819.

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Milton’s house No. 19, York Street, Westminster, occupied by Hazlitt 1812–1819.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| FREE THOUGHTS ON PUBLIC AFFAIRS | 1 |

| POLITICAL ESSAYS | 25 |

| ADVERTISEMENT, ETC., FROM THE ELOQUENCE OF THE BRITISH SENATE | 387 |

| NOTES | 427 |

This pamphlet of 46 8vo pages was published by the author himself in 1806. The title-page was ‘Free Thoughts on Public Affairs, or Advice to a Patriot; in a Letter addressed to a Member of the Old Opposition. London, Printed by Taylor & Co., Shoe Lane, and sold by J. Budd, Crown & Mitre, Pall Mall, 1806.’ Mr. W. C. Hazlitt reprinted the pamphlet from the author’s own copy in 1885 (Bohn’s Library, The Spirit of the Age, etc.), and that reprint forms the text of the present edition. The pamphlet is exceedingly rare. Mr. Alexander Ireland knew of only one copy, that which belonged to Mr. W. C. Hazlitt. This he caused to be transcribed; but it has not been possible to collate the present text with either the original or Mr. Ireland’s transcription.

Sir, If the opposition of character between the individuals of different nations is that which attaches every one the most strongly to his own country; if the love of liberty instilled from our very cradle is any security for the hatred of oppression; if a spirit of independence, and a constitutional stubbornness of temper are not forward to crouch under the yoke of unjust ambition; if to look up with heartfelt admiration to the great names, whether heroes or sages, which England has produced, and to be unwilling that the country which gave birth to Shakespear and Milton should ever be enslaved by a mean and servile foe; if to love its glory—that virtue, that integrity, that genius, which have distinguished it from all others, and in which its true greatness consists,—is to love one’s country, there are few persons who have a better right than myself (on the score of sincerity) to offer that kind of advice which is the subject of the following letter, however weak or defective it may be found.

To love one’s country is to wish well to it; to prefer its interests to our own; to oppose every measure inconsistent with its welfare; and to be ready to sacrifice ease, health, and life itself in its defence. But there is a false kind of patriotism, loud and noisy, and ever ready to usurp that name from others, as an honourable covering either for selfish designs or blind zeal, to which I shall make no pretensions. It has been called patriotism, to flatter those in power at the expense of the people; to sail with the stream; to make a popular prejudice the stalking-horse of ambition, to mislead first and then betray; to enrich yourself out of the public treasure; to strengthen your influence by pursuing such measures as give to the richest members of the community an opportunity of becoming richer, and to laugh at the waste of blood and the general misery which they occasion; to defend every act of a party, and to treat all those as enemies of their country who do not think the pride of a minister and the avarice of a few of 2his creatures of more consequence than the safety and happiness of a free, brave, industrious, and honest people; to strike at the liberty of other countries, and through them at your own; to change the maxims of a state, to degrade its spirit, to insult its feelings, and tear from it its well-earned and proudest distinctions; to soothe the follies of the multitude, to lull them in their sleep, to goad them on in their madness, and, under the terror of imaginary evils, to cheat them of their best privileges; to blow the blast of war for a livelihood in journals and pamphlets, and by spreading abroad incessantly a spirit of defiance, animosity, suspicion, distrust, and the most galling contempt, to make it impossible that we should ever remain at peace or in safety, while insults and general obloquy have a tendency to provoke those passions in others which they are intended to excite.

Being then of opinion, that to flatter is not always the duty of a friend; that it is no part of the love of one’s country to be blind to her errors, or to wish her to persist in them; I may take the liberty of stating freely such observations as have occurred to an unprejudiced but not indifferent spectator on the present state of things: and there is at least this advantage in reflections which are not the echo of the popular cry, that something may be found in them, however unsupported or frivolous in general, which may be turned to good account by persons of sounder judgment and more extensive means of information. It has been said that ‘there is wisdom in a multitude of counsellors;’ but if they only raise a clamour by repeating all of them the same thing, I do not see how this advantage can be obtained.

What I would chiefly remark upon is,—How far the principles and views acted upon by the late administrations are such as to afford us the safest and most honourable ground for prosecuting a war which is said to be carried on for the existence of the empire.

Had I to engage with an enemy in a struggle of this kind, the ground which I should choose to occupy would be such a one as that he must feel himself to be the aggressor. In a conflict which is to decide the fate of a people, I think the greatest care should be taken to remove all doubtful or frivolous causes of debate, to suffer no sinister motives to divert their minds from the great object in which they are engaged or lessen their steady confidence in the justice of their cause. It is hardly to be expected that the mass of a people should defend the patrimony of independence which they inherit from their ancestors with the reverence, intrepidity, and dauntless zeal required of them, when they see a minister ready to gamble it away for the first idle object that excites his cupidity, or opens a door to the spirit of intrigue. Examining the conduct of those who were the advisers and authors of the late renewal of hostilities according to 3these maxims, which seem to me well founded, it is not easy to imagine any thing more remote from true dignity, magnanimity, or wisdom, than the manner in which we chose to enter upon a war on which we were to stake our all. We chose to rest a dispute, which was to involve every thing near and dear to us, on a diplomatic ambiguity; on a technical question, as to the manner how and to whom we were to give up a barren rock which was of no use to us, and to which we had resigned all pretensions. It was clear that we had refused to fulfil our share of a treaty which had been formally ratified; but the reasons which we gave for doing this were by no means equally clear and satisfactory. They sounded more like the excuses of those seeking a pretence for the continuance of an unsuccessful contest, than the remonstrances of persons sincerely anxious for peace, and opposed by real difficulties. I remember at the time when the design of retaining Malta was first made known, every one’s remark was,—Had we not agreed to give it up? And as to the official reasons for this change of measures, which were afterwards detailed to the public with such pomp and circumstance, viz., that it was to have been given up to the Order that formerly possessed it only on the supposition of that Order’s remaining entire, though no such condition had been expressed, and under the guarantee of another power whose consent had neither been asked or obtained, I believe that no one who was not either indifferent to peace or desirous of war ever thought them of sufficient consequence to justify us in exposing ourselves to unnecessary reproach and odium, and plunging into a sea of unknown troubles. It is certain that by the generality of people they could neither be felt nor understood. On this tottering foundation did Mr. Addington think proper to take his stand. Doubt, perplexity, evasion, a general indifference as to the immediate object of the dispute, and a direct accusation of breach of faith on the part of the enemy were the auspices under which we were to begin a war, which ought (from the tremendous consequences attached to it) to have had no motives but what came home to the bosoms and businesses of men; to every manly, generous, and honest feeling; that might not have been uttered boldly without fear of contradiction in the face of an enemy; that must not have beat in every heart, have strung every arm, and animated every tongue. If the situation of the country was believed to be at all precarious; if there was even a chance that the contest might really lead to the dreadful alternative held out to us, the want either of cautious prudence or of manly wisdom in ministers was at that time inexcusable. It is no part of wisdom to hang the fate of kingdoms in the balance with straws. It is no part of courage to fight, to show that you are not afraid of 4fighting. Calm steady courage does not distrust itself; nor is it afraid that by giving up a trifling or doubtful point, it may afterwards be bullied into dangerous compliances. Firmness and moderation seem to me not only not incompatible with each other, but that the one is a necessary consequence of the other. On the other hand, meanness and pride are nearly allied together. In common life we should think that a readiness to seize the first occasion of quarrel shewed a man to be either a bully or a coward; it would seem as if he was afraid that by deferring his resentment he should either want courage or opportunity for shewing it another time. Yet the great excuse for our going into the war was,—that by yielding any thing to the demands of the enemy, we should soon lose all power of resistance, and crouch in abject submission at his feet. This was not a proud confidence in ourselves, but a mean dread of our own pusillanimity and want of firmness. It was to suppose that we had no security for our firmness, but in the heat of our passions and the infliction of mutual injuries. But it may be said, that whatever was the cause of the war, the consequences were the same. The critical situation in which we stood, and the threats of the enemy made it necessary for us to repel force by force, to call forth every energy of which we were possessed, and to stand forth as one man in defence of the country. But whatever this might prove as to the conduct of the people, it forms no justification of the conduct of ministers. It was not the danger of invasion which produced the taking up arms, but the determination to take up arms which produced the fear of invasion. The threatened invasion was not the cause of the war, but the consequence of it. This reasoning, as applied to the commencement of the war is preposterous. It is the same absurdity as to give yourself an infectious disease in order that you may call in the physician, instead of calling in the physician because you are attacked by the disease. It is ridiculous, I say, to argue that the war was necessary to repel the horrors and ravages of invasion; when, if the war had not taken place, no such evils would have been possible. It was true, that so long as we determined to carry on the war, it was necessary to guard ourselves against the consequences of war; but to suppose (which seemed to be generally the case with the good people of England in the height of their panic) that to doubt for a moment of the necessity of the war was the same thing as wishing that the French might come here and put every one to the sword (when one chief object of peace would be to prevent all such wild alarms), implies such an intricate confusion of ideas as I am not able to unravel. At least I can account for it only in one way; by supposing that this reluctance to distinguish between the necessity of our going to war, 5and the necessity of self-defence, brought upon us by it, arose from a deep consciousness in the human mind of the importance of the motives by which we have been actuated to the success of our undertakings, and a belief that he who lessens your confidence in the grounds of your proceeding, thereby unnerves your resolution, and lessens your safety. I know that immediate danger, however incurred, produces the same necessity for self-defence; but it does not produce the same temper of mind and motives for going through it. It may also produce the same mechanical courage at the moment; but perseverance, superiority to fear or disaster, self-confidence, a cheerful determined submission to the greatest hardships and sufferings from a sense that they were unavoidable, ‘the unconquerable will, and courage never to submit or yield, and what else is not to be overcome;’ all these are not in the gift of fear, or folly, or ignorance, or hatred. It is therefore of the highest consequence to ascertain the true grounds and motives of a war, such as the present, and to know the spirit and sentiments by which it was brought about, and to what part of our character, whether to its strong or its weak side, whether to our vices or our virtues, those motives were addressed which called forth our ardour and readiness to engage in it. It is not from loud boasting, from what we think or say of ourselves, but from what we really are; not from a pretended, but real love of justice, of independence, of honour, and of our country’s welfare, that we can expect the fruits of victory. If we find in those who lead, no higher principle of action than a wish to serve their own interests, or gratify their own passions, and in those who are led, only that zeal which arises from the drunken uproar of an ale-house, the low credulity of ignorance, or the idle vanity of wearing a red coat and shouldering a firelock—I will not say that the situation of the country is desperate indeed, but I think it is not such as to afford the most solid grounds of confidence in our security against a spirit of unbounded ambition; the insolence of almost unexampled success, resentment for supposed injuries, and the most consummate military skill. ‘The still small voice is wanting.’... It is not in the order of nature that an administration acting upon such principles as I have here described should feel, or be capable of inspiring into others, either true patriotism, a sincere and manly spirit of independence, or any particle of that high-souled energy, which is necessary to contend with inordinate ambition, armed with strength and cunning. That administration is no more: I trust that its spirit has not survived it!

It seems almost impertinent at present to turn back to the diplomatic pedantry and legal quibbling by which the retention of Malta was so gravely justified at the time. After the repeated declarations that 6have been made in parliament, and after having witnessed those tragical events, to which, it seems, it was the necessary prelude, there can be little doubt as to the real motives of that measure. From these motives then we are to form our opinion of the conduct of ministers. If it was a wise and necessary measure to plunge Europe again into the calamities of war, to bathe it once more in that ‘fountain of blood,’ then and then only was our refusing to fulfil our engagements a wise and necessary determination; for the now avowed reason of our going to war was, that we might not remain at peace! Here then was a war voluntarily undertaken for its own sake, peace studiously shunned, and all the evils consequent upon such a step incurred, for the sake of making one more desperate effort to reduce the power of France and humble it with the dust. We therefore entered upon this wild Quixotic scheme at our own peril, and the responsibility of the war devolved upon us. We ought therefore to have had strong grounds, either from a confidence in the result or from the justice of the principle, for making such an attempt. But we have seen what has been the result with respect to the other powers of Europe, it remains to be seen how it will terminate with respect to ourselves. As to the justice and generosity of the design, I may perhaps speak of that hereafter.

I will not pretend to censure the general practice of obtaining a war under false pretences, I leave it to the politicians to settle the rules of honour among themselves: but I cannot help thinking that in a war which is to try the spirit of a people, they ought not to be tricked, or bullied, or unnecessarily forced into it. With respect to the suspension of the war in consequence of the treaty of Amiens, it certainly had this good effect (on the supposition that it was absolutely necessary to go on with the contest), that it gave those who had been enemies of the old war, and had been afterwards disgusted by the conduct of the French, but did not like to relinquish their opinion while the original cause of dispute remained—it gave all persons of this class (of which there were great numbers) an opportunity to quit the ranks of discontent without exposing themselves to the charge of inconsistency. As it was a new war, they thought they had a fair right to have a new opinion about it; and they exercised their freedom of election as eagerly in approving the conduct of ministers in entering upon the present war, as they had done in condemning their continuance of the former one. For myself, I confess I have always looked upon the present war as a continuance of the last, carried on upon the same principles and for the same purposes, only without any hopes of success, and therefore infinitely more wanton and foolish. For as, in the commencement of the last war, it was our intention to 7conquer France, in this we can only hope to defend ourselves. Of the necessity of this defence there can be but one opinion. But to confound this with the necessity of the war itself, or to argue as if the discontinuance of the war would increase the dangers arising from it, is an improvement in political logic, a luminous arrangement of ideas, that must have crept in with the benefits of the Union.

The first plea that was made use of to give a colouring of interest to the renewal of hostilities, before the discovery of that profound train of policy, the explosion of which has left Europe a heap of ruins, was, that after the incautious surrender of Malta, it had been found to be of much greater importance to Great Britain than had been imagined at the time; and that it could not be suffered to fall into the hands of the French, or even become subject to their influence, without endangering one of the chief sources of the wealth and prosperity of this country. It seems Malta was the enchanted island, into which Buonaparte was to convey himself by stealth, and thence passing easily into Egypt was, at another vast stride, to come down souse upon our possessions in India. With these resting-places, and the help of the thousand-league boots which our imagination had lent him, the political magician was to take but a hop, step and a jump, from one hemisphere into the other. Or, in the language of the day, Malta was the key to Egypt, and Egypt was the key to our Eastern conquests. Both the points assumed in this statement were directly denied, and their fallacy exposed at the time by one to whose authority or reasonings on the subject I can add nothing; but I may be permitted to make one general remark with respect to this part of the subject, that if the mere possibility of the loss of an object of national aggrandisement is to be considered as a sufficient ground of war, there never could be such a thing as peace among mankind. If one party is to be kept in a state of perpetual alarm from a distant apprehension of losing the superiority they possess in wealth, or luxury, or power, and the other to be perpetually goaded on by the hope of speculative plunder; if one party is determined to forgo nothing, and the other to grasp at everything; if future causes of contention are to be anticipated, and we are to fight now to defend an object that may never come into dispute hereafter; if we are not to wait till we see and feel our danger, but to create it out of every fantastic occasion; if our selfishness must be of that refined calculating comprehensive kind as to overlook no possibility of danger or advantage however remote or uncertain, and at the same time so inflexibly disinterested as to think no sacrifices too great in pursuit of its favourite object—it is easy to see that the world would soon be dispeopled. It is well for mankind that our passions naturally circumscribe themselves, and contain their 8own antidote within them. The only excuse for our narrow, selfish passions is their short-sightedness: were it not for this, the jealousies of individuals and of nations would never leave them a moment’s interval of rest or quiet. It is well that the headlong passions which make us rush on our own destruction and that of others are only excited by gross, palpable objects; and are therefore transient and limited in their operation. It is well that those motives which owe nothing to reason in their birth should not afterwards receive either nourishment or support from it. If in their present desultory state they produce so many mischiefs, what would be the case if they were to be organized into systems, and under the direction of pure abstract reason? Any object that provoked a momentary resentment or excited our jealousy might plunge us into a war that could only be expiated by seas of blood. But in a war of mere interest or passion, it is surely allowable to sit down and count the cost, and to strive to moderate our pride and resentment instead of inflaming them. Virtue, truth, and patriotism require nothing of us but an inviolable resolution and integrity in the defence of those rights which are the common privilege of humanity; the rest is a calculation of prudence, not a stern command of duty that admits neither of compromise or delay. To defend at the point of the sword, and at the risk of every thing valuable, our title to the possessions that are neither necessary nor durable in their own nature, that are never worth a hundred years’ purchase, that may crumble to pieces of their own accord, or slip out of our hands in various ways before the end of the contest, and which afterwards will be no more secure ‘against infection and the hand of war,’ against the insidious or desperate designs of the enemy, against the breath of accident or unforeseen decay than they were before—is madness and folly. It is to defeat the intended favours of Fortune, by paying for them before-hand a price much greater than they can ever be worth. It is to squander away the whole estate of our present happiness and comfort in purchasing security for that, for which no security ever was or can be given—the continued smiles of fortune. We cannot without a presumption that will involve its own punishment think of placing beyond the reach of chance or fate that which by its own nature and the fluctuation of human affairs is liable to change.

But this must be the case with all distant and maritime possessions: indeed all naval superiority is attended with this necessary disadvantage; that, though actual power, it is not self-dependent, or the source of its own permanence. We cannot secure the possession of the sea in the same manner by taking ships as we can the possession of the land by taking fortresses and countries. The longer a successful 9continental warfare is carried on, the more able is the conqueror to carry it on: every new conquest that he makes furnishes him with the means of making more, and secures to him what he has already gained by striking at the heart of power, by disarming resistance, and by very liberally rewarding the expence and trouble of keeping it—Whereas the advantages that are gained at sea are, like that element itself, infinitely treacherous and uncertain. We may take their ships; but this will not hinder them from building others. We cannot build forts or erect passes on the seas, or dig them into trenches to keep out the enemy. We cannot enter their country and cut down their forests; we cannot enter their ports and destroy their magazines;—all their means and sources of power remain untouched. We cannot prevent their exertions, though we may constantly render them abortive. Thus, while at an enormous expence we maintain our actual superiority, we make no advances to our object—which is security; but are rather further from it. If we ever make peace, which I suppose will happen sooner or later, we shall find that we have not in any one respect lessened the means or palsied the energies of our rivals; and while we remain at war we are teaching them two very dangerous things, resolution and skill. I conceive no power can be long superior to the attacks of another, unless where it has the means of crushing its resistance in embryo. Naval dominion is in this respect what a government would be that should give to insurgents a free communication with each other, full liberty of forming plans and of organizing themselves into regular bodies of troops, and the privilege of never being attacked till they themselves gave the signal for the onset. Military conquests are therefore in their nature to a certain degree secure; because in maintaining them we have to contend with those whom we have bound hand and foot, from whom we have taken all effectual power of resistance; while in maintaining our naval superiority, we strengthen our adversary by struggling with him, since he has the full use of every limb and muscle, has every inducement as well as opportunity to exert himself to the utmost, and is in no danger of receiving any material hurt; at least this must be the consequence where our natural strength and advantages are at all equal. I know nothing but some such reasoning as this on the inefficiency of naval advantages, as a means of reducing the enemy to terms of submission, that could form the least excuse for the late ministers in their desperate attempt to turn the course of the war from a channel in which it was sure to be successful, into one in which it was sure to be disastrous; to throw the game knowingly and wilfully into the enemy’s hands, and ruin us in our allies. They seemed to anticipate with fatal apprehension the most splendid success 10that ever adorned the annals of the British navy, and to be determined by an inverted ambition to match it with a pattern, in their own style, of equal horror, discomfiture, and dismay. They seemed to conspire maliciously with fortune, in depriving Englishmen of the pure, unalloyed triumph of that day.—For the present, the errors of the cabinet have entirely defeated whatever advantages we might have derived from our naval success; and the effect of our mistaken policy has been, that while we remain undisputed masters of the seas, and are grasping at the commerce of the world, we see the ports of Europe about to be shut against us. War on the continent is therefore hopeless; war at sea useless, or worse than useless: for methinks there is neither policy nor wisdom nor humanity ‘in resolving to set no limits to your hostility but with your existence,’ when you have to contend with a great and formidable foe; when you only know that he is safe from your attacks; when you can only distress him, when you gain no advantage yourself in the mean time, and cannot possibly gain any that can be put in competition with such an alternative; when we consider that such a resolution (however heroically it may be formed) cannot be always persisted in (for the desire of peace is natural, and war revolting to the human mind); that the longer it is adhered to, the more mischievous it will become, and the more dangerous in its consequences afterwards, and will render the diminution of that maritime preponderance, which we have held with such a convulsive grasp, more and more an object both of policy and revenge to other powers.

I have promised to say something of the justice of the war in its principle, not as a war of defence but as a war of interference; though I think the less is said on this subject the better; it can only open ‘another Iliad of woes.’ It must lead to a train of recollections that can be of no use to us at present; or revive sentiments and a spirit that should be recalled only (if it were possible) to be disclaimed. The less we retain of a spirit of offence, and the sooner we forget ourselves in the character of aggressors, in however just a cause, the better shall we be qualified for our present posture of defence: for there is no ground of resistance so sure as a determined belief, for the time at least, that all aggression must be wrong. I am far from thinking that the arbitrary conduct of a government, even where it does not affect ourselves, is not a just ground of war, or that the conduct of the French government was not marked by a spirit of violent and unjust ambition. Of course if that spirit can be resisted with effect, there is no injustice, and there is a great deal of policy in doing it. But before we can plead generous indignation and an uncontrolable love of justice in excuse for our rashness and imprudence, 11it must be clear that pride, revenge, and the lust of dominion have had no share in producing this ardent concern for the rights and liberties of mankind. It is not the nature or justice of the occasion, but the use intended to be made of it; the principles and views on which we act, and the character of those with whom we are associated in a common cause, that gives us a right to arrogate to ourselves the title of assertors of the liberties of mankind. If, however, our motives are not such as to be above all suspicion, it is not enough that we are able to hide them from ourselves, unless we can at the same time impose upon those who have not the same interest in being deceived by the thin disguise that covers them. Instead then of enquiring into the abstract justice of the war (a sort of enquiry now very nearly exploded, and which would be of little use in guiding our practical conclusions), let us examine in what manner our remonstrances would be likely to be received by the government to whom they were addressed, and how far the common feelings of humanity would compel them ‘to bow their crested pride’ at the feet of their accusers. Would they forget then that the undue and dangerous influence in the affairs of Europe, which was so loudly complained of, had been the consequence of the combined efforts of all Europe to accomplish their destruction, and was so far from being the cause of the hostility of other states, that it was their only security against it? That their unjust and tyrannical encroachments on the independence of the neighbouring states had been made in defending their own independence from the aggressions of which they were made the instruments? They would say, that to think of restoring the independence of those countries would be putting into the hands of a mortal enemy, whom you have just disarmed, the weapons with which he may most surely effect your destruction; that whatever advantages they had gained had been bought with their blood, shed for their country; that if there had been any instance of unjust aggression, or inordinate ambition, it might at least be accounted for from that natural jealousy of others, and that fierce impatience of control, that must become habitual to those who had had every kind of difficulty to encounter, and who had triumphed over all opposition. The gigantic strength and towering greatness of France had arisen from her convulsive struggles for existence, and in the cause of that liberty which was denied her. They, who had insulted her weakness and blasted her hopes, had no right to complain of her strength or her despair. Those who had not been able to make their country free and happy, would be instigated by a just revenge to make her great and formidable to her enemies. They might say, ‘You left us no choice between the highest point of glory, and the most abject 12submission; we must either be conquerors or slaves. If you gained an advantage, you pursued it; if you were defeated, you returned to the charge; neither success nor misfortune inclined you to listen to terms of accommodation: we saw that we could never hope for peace, but either by giving to France such an ascendancy as would overawe the rest of Europe, or by throwing ourselves at last on the mercy of our unrelenting foe. We had not forgotten the partition of Poland, the massacres of Ismael and Warsaw; and we could not satisfy ourselves but that those who had had the chief concern in these events, or had witnessed them without dismay, might have other objects in view in entering France, besides the tranquillity of the people, the restoration of order, or a disinterested regard for the safety of thrones, and the independence of Europe. We could not conceive that an implacable enmity to France was a full atonement for all other crimes, or a security for every virtue. Pursued, hunted down, driven to madness, we turned upon our pursuers, and trampled them under our feet; and in the career of our fury, and the plenitude of our triumph, you charge us with excesses, from which we ourselves were the greatest sufferers; and with not having observed those rules of justice and moderation, which reason required of us. We were to have no indemnity, no security: we were to give back every conquest, as soon as made; to fight every battle over again; to rely solely on the faith or generosity of our adversaries, as a pledge that no advantage would be taken of our confidence; or, if it were ten times betrayed, we were not to complain, as we had no right to advantages obtained by unjust violence, in a cause that exposed us to the enmity and detestation of the human race: we were to plead guilty to our own condemnation; to set the seal on our own infamy, and to receive as a mark of favour and lenity, whatever implied our admission into the common rank and privileges of mankind; and, after endless sacrifices and exertions, we were only to prepare for new struggles and insults, without ever hoping to end them. But from whom were we to learn this extreme moderation, or that respect for the rights of justice or the ties of humanity, which could be no defence to us? Why were we not to pursue the objects of our ambition, with the same obstinacy as those with whom we had to contend pursued the objects of their revenge? It could hardly be expected that all the concessions were to be made by those who were intoxicated with the pride of victory, in favour of those who had reaped nothing but disappointment, and who were only urged on by a sullen despair. In this manner was the war protracted, year after year, by open hostility, by civil dissentions, and pretended treaties; lingered out under various pretexts, which 13were artfully substituted for each other as occasion required, so as to make it impossible ever to arrive at any decisive issue to the contest. When defeated, the continuance of the war was necessary to their own defence and safety; when flushed with victory for a time, then nothing less than full indemnity for the past, as well as security for the future would satisfy them; and then their favourite object, the subjugation of France, and destruction of the republic, was resumed with fresh ardour, and tempted them on till their hopes again ended in defeat and ruin: thus adapting every aspect of affairs to their own purposes, they constantly returned in the same circle to the point from which they set out, and war was always necessary, peace always unattainable. Or if at any time the fainting resolution and exhausted strength of our adversaries seemed to promise us that repose which was so necessary to us, we saw the dying embers of war again eagerly rekindled by a country that, standing aloof from the contagion, shouted from her rocky shores to see the flames that consumed the vitals of Europe. The bitterest enmity that our early struggles in the cause of liberty had drawn down upon us was to be shewn by a people “that had long insulted the slavery of Europe, by the loudness of its boasts of freedom.” English solicitation and English gold were always ready to defeat that object, which was to be the reward of so many triumphs, and of so many years of suffering, of havoc, uncertainty, and dismay. A reluctant peace was at length extorted from her: but her jealousy, avarice, and pride made her choose to risk every thing rather than remain in a state so unnatural to her. Delicate in her moral sentiments, disinterested in all her proceedings, she was shocked at some violences of ours, which permitted her no longer to remain an indifferent spectator of the calamities of other nations, and she sought the first opportunity of evading the treaty that had been concluded, by alarming the fears of her merchants for the safety of their Eastern possessions. She lost no time in rousing to her aid her former confederates in wrong. By her incantations, the hydra-headed monster, which we thought we had finally subdued, again feels new life and vigour restored to it, unites its severed folds, and with its triple crown moves onward to its prey, and France must submit or perish, that England may preserve her commerce.’ In some such manner as this would a Frenchman repel the charges brought against his countrymen; and, if we allow for the strength of national prejudices, there appears to be some appearance of reason in what he says.[1] If the present quarrel had been so managed as to 14have been completely disentangled from the former one, we should have been better able to answer their reproaches, and I think to resist their menaces. Had not Austria been precipitated unwisely into that quarrel in the manner she was, she could not have fallen to the ground without a struggle.

In what further remarks I have to make, I shall consider whether the system of internal policy pursued by the late minister was in its general tendency likely to increase the spirit of independence, and consequently the security of the country. It seems to me a desirable object to refer as much as possible of our proceedings both at home and abroad to the influence of that minister’s character on the national feelings, and to the blind confidence generally placed in his talents and integrity. The errors that we have been led into by a confidence of this sort will be sooner retrieved than if they proceeded from a change in our own habits and dispositions. It is well if we can save the credit of our national character, a little at the expence of our understandings; for I cannot think that our confidence in that minister was well bestowed. I know it is a general maxim, that we are not to war with the dead. We ought not, indeed, to trample on their bodies; but with their minds we may and must make war, unless we would be governed by them after they are dead. They who wish their sentiments to survive them in the memories of men, must also expect to live in their censures.

The character of Mr. Pitt was, perhaps, one of the most singular that ever existed. With few talents, and fewer virtues, he acquired and preserved in one of the most trying situations, and in spite of all opposition, the highest reputation for the possession of every moral excellence, and as having carried the attainments of eloquence and wisdom as far as human abilities could go. This he did (strange as it appears) by a negation (together with the common virtues) of the common vices of human nature, and by the complete negation of every other talent that might interfere with the only one which he possessed in a supreme degree, and which indeed may be made to include the appearance of all others—an artful use of words, and a certain dexterity of logical arrangement. In these alone his power consisted; and the defect of all other qualities, which usually constitute greatness, contributed to the more complete success of these. Having no strong feelings, no distinct perceptions, his mind having no link, as it were, to connect it with the world of external nature, every subject presented to him nothing more than a tabula rasa, on which he was at liberty to lay whatever colouring of language he pleased; having no general principles, no comprehensive views of things, no moral habits of thinking, no system of action, there was 15nothing to hinder him from pursuing any particular purpose by any means that offered; having never any plan, he could not be convicted of inconsistency, and his own pride and obstinacy were the only rules of his conduct. Having no insight into human nature, no sympathy with the passions of men, or apprehension of their real designs, he seemed perfectly insensible to the consequences of things, and would believe nothing till it actually happened. The fog and haze in which he saw every thing communicated itself to others, and the total indistinctness and uncertainty of his own ideas tended to confound the perceptions of his hearers more effectually than the most ingenious misrepresentation could have done. Indeed, in defending his conduct he never seemed to consider himself as at all responsible for the success of his measures, or that future events were in our own power; but that as the best laid schemes might fail, and there was no providing against all possible contingencies, this was a sufficient excuse for our plunging at once into any dangerous or absurd enterprise without the least regard to consequences. His reserved logic confined itself solely to the possible and the impossible, and he appeared to regard the probable and improbable, the only foundation of moral prudence or political wisdom, as beneath the notice of a profound statesman; as if the pride of the human intellect were concerned in never entrusting itself with subjects, where it may be compelled to acknowledge its weakness.[2] From his manner of reasoning, he 16seemed not to have believed that the truth of his statements depended on the reality of the facts, but that the things depended on the order in which he arranged them in words: you would not suppose him to be agitating a serious question, which had real grounds to go upon, but to be declaiming upon an imaginary thesis, proposed as an exercise in the schools. He never set himself to examine the force of the objections that were brought against his measures, or attempted to establish them upon clear, solid grounds of his own; but constantly contented himself with first gravely stating the logical form, or dilemma to which the question reduced itself, and then, after having declared his opinion, proceeded to amuse his hearers by a series of rhetorical common-places, connected together in grave, sonorous, and elaborately constructed periods, without ever shewing their real application to the subject in dispute. Thus if any member of the opposition disapproved of any measure, and enforced his objections by pointing out the many evils with which it is fraught, or the difficulties attending its execution, his only answer was, ‘that it was true there might be inconveniences attending the measure proposed, but we were to remember, that every expedient that could be devised might be said to be nothing more than a choice of difficulties, and that all that human prudence could do was to consider on which side the advantages lay; that for his part he conceived that the present measure was attended with more advantages and fewer disadvantages than any other that could be adopted; that if we were diverted from our object by every appearance of difficulty, the wheels of government would be clogged by endless delays and imaginary grievances; that most of the objections made to the measure appeared to him trivial, others of them unfounded and improbable; or that if a scheme free from all these objections could be proposed, it might after all prove inefficient; while, in the mean time, a material object remained unprovided for, or the opportunity of action was lost.’ This mode of reasoning is admirably described by Hobbes, in speaking of the writings of some of the Schoolmen, of whom he says, that ‘they had learned the trick of imposing what they list upon their readers, and declining the force of true reason by verbal forks, that is distinctions which signify nothing, but serve only to astonish the multitude of ignorant men.’ That what I have here stated comprehends the whole force of his mind, which consisted solely in this evasive dexterity and perplexing formality, assisted by a copiousness of words and common-place topics, will, I think, be evident to any one who carefully looks over his speeches, undazzled by the reputation or personal influence of the speaker. It will be in vain to look in them for any of the common proofs of human genius or wisdom. He has 17not left behind him a single memorable saying—not one profound maxim—one solid observation—one forcible description—one beautiful thought—one humourous picture—one affecting sentiment. He has made no addition whatever to the stock of human knowledge. He did not possess any one of those faculties which contribute to the instruction and delight of mankind—depth of understanding, imagination, sensibility, wit, vivacity, clear and solid judgment. But it may be asked, If these qualities are not to be found in him, where are we to look for them? And I may be required to point out instances of them. I shall answer then, that he had none of the profound, legislative wisdom, piercing sagacity, or rich, impetuous, high-wrought imagination of Burke; the manly eloquence, strong sense, exact knowledge, vehemence and natural simplicity of Fox; the ease, brilliancy, and acuteness of Sheridan. It is not merely that he had not all these qualities in the degree that they were severally possessed by his rivals, but he had not any of them in any degree. His reasoning is a technical arrangement of unmeaning common-places, his eloquence merely rhetorical, his style monotonous and artificial. If he could pretend to any one excellence in an eminent degree, it was to taste in composition. There is certainly nothing low, nothing puerile, nothing far-fetched or abrupt in his speeches; there is a kind of faultless regularity pervading them throughout; but in the confined, mechanical, passive mode of eloquence which he adopted, it seemed rather more difficult to commit errors than to avoid them. A man who is determined never to move out of the beaten road cannot lose his way. However, habit, joined to the peculiar mechanical memory which he possessed, carried his correctness to a degree which, in an extemporaneous speaker, was almost miraculous; he perhaps hardly ever uttered a sentence that was not perfectly regular and connected. In this respect, he not only had the advantage over his own contemporaries, but perhaps no one that ever lived equalled him in this singular faculty. But for this, he would always have passed for a common man; and to this the constant sameness, and, if I may say so, vulgarity of his ideas must have contributed not a little, as there was nothing to distract his mind from this one object of his unintermitted attention; and as even in his choice of words he never aimed at anything more than a certain general propriety and stately uniformity of style. His talents were exactly fitted for the situation in which he was placed; where it was his business not to overcome others, but to avoid being overcome. He was able to baffle opposition, not from strength or firmness, but from the evasive ambiguity and impalpable nature of his resistance, which gave no hold to the rude grasp of his opponents: no force could bind the loose phantom, and 18his mind (though ‘not matchless, and his pride humbled by such rebuke,’) soon rose from defeat unhurt,

By this lucky combination of strength and weakness, he succeeded in maintaining an undiminished influence over the opinions of his own country for a number of years, in wielding her energies as he pleased, and guiding the counsels of almost all Europe. With respect to his influence on the continent, that is an illusion that is past, and not worth inquiring about; but it may still be of some use to inquire by what means he strengthened his influence at home, as this may more immediately concern our future conduct. This I think he effected in two ways: by lessening the free spirit of the country as much as he could, and by giving every possible encouragement to its commercial spirit. I shall not here examine how far both these designs were wise and salutary at the time; but I conceive that neither a spirit of dependence nor an unbounded and universal spirit of trade will be the best security for our safety at present. An indifference to liberty is not likely to increase the love of independence; nor is an exclusive regard to private gain likely to produce a disinterested concern for the public welfare. Mr. Pitt, in making war, always considered peace as an object perfectly indifferent in itself; and, in securing the prerogative of the crown, seemed to think that the privileges of the people did not deserve a moment’s attention. I do not in this mean to condemn his conduct: perhaps we may suppose that the restrictions which he introduced on the liberty of the subject, and the spirit of passive obedience and non-resistance which was 19every where industriously diffused, the contempt and obloquy which were poured on the very name of liberty, might be required by the circumstances of the time, and necessary to prevent the contagion of a dangerous example, and the mischiefs of civil anarchy and confusion. The public were perhaps justly surfeited with metaphysical treatises overturning the foundation of all civil rights, and the very notion of liberty, with historical disquisitions proving that the popular spirit of political institutions was the bane of all internal quiet and happiness, the source of endless violence and bloodshed, and the final cause of their dissolution; that human happiness could never reach its utmost point of perfection but under the mild and tranquil reign of universal despotism; that the forms of all governments were alike indifferent, provided they secured the same servile obedience and death-like apathy in the state. Perhaps it was then necessary that we should be told, ex cathedrâ, that the people had nothing to do with the laws but to obey them: perhaps it was right that we should be amused with apologies for the corrupt influence of the crown; that integrity, honour, the love of justice, public spirit, or a zeal for the interests of the community should be laughed at as absurd chimeras, and that an ardent love of liberty, or determined resistance to powerful oppression should be treated as madness and folly. But however wise or necessary a temporary fashion of this kind might be to counteract the poison of other views and sentiments, I am sure it can neither be wise nor safe to continue it at present. We ought to do every thing in our power to get rid of the effects of so dangerous a habit as soon as possible. The fewer curbs there are on the spirit of the people, the more vigorous and determined will it shew itself; the greater the encouragement that is given to the principles of liberty, and the greater confidence that is placed in the general disposition of the country, the greater and more irresistible will be their habitual attachment to liberty and independence. You give a manifest advantage to an enemy if you in any way lessen the sources of enthusiasm, or in any way check the ardour, confine the energy, degrade the sentiments, or discountenance the erect, manly, independent spirit of your country. It is dangerous to let any thing fall into disrepute or contempt which may serve as a watchword to startle the dull ear, or rouse the frozen blood; but to this purpose it is not enough that the name is retained, if the habitual feeling is destroyed. A tame acquiescence in every encroachment of power or exertion of undue influence, a disposition to assert our own rights or those of others no further than fear or interest permit, a habit of looking on the welfare of our country or the rights of mankind as secondary considerations, no further to be regarded than as they are 20connected with our own danger or convenience, these are not the symptoms of the durable greatness and independence of a people. The causes of the ruin of states have been almost always laid in the relaxation of their moral habits and political prejudices. No kingdom can be secure in its independence against a greater power that is not free in its spirit, as well as in its institutions. I shall be happy if I have been mistaken in thinking these observations at all applicable to our own country: but the observations themselves are serious, and worth attending to. They are such as have been recognised in all nations and ages, except those indeed where their having been so would have rendered them suspected.

On the other hand, a commercial spirit is a very weak as well as dangerous substitute for a spirit of freedom: a sense of self-interest, of mere mercenary advantage, can but ill supply the place of principle. The love of gain, however active or persevering this principle may be in accomplishing its own particular ends, can never be safely trusted to as an ally in a cause where there are other objects to be attended to. Men who are actuated by this sole principle will very obstinately, no doubt, defend their wealth, while they can retain it; but when that is no longer the case, they will think nothing else worth retaining, and meanly compromise their independence for their safety. That common birthright which they receive from nature, in which every Englishman has an equal interest as such, appears of little value in their eyes. Liberty is in their eyes a coarse homely figure, but for the jewels that sparkle in her hair, and the rings on her fingers. It is inconceivable to them how a man can have any attachment to a simple shed, or can take any pride in his title to that respect, which is due to him only because he feels himself to be free. They will defend England as connected with her colonies, with her proud canopies of Eastern state, her distant spicy groves and the rich spoils of her Western isles; but will they defend her as she is England, as their country? Strip her of her conquests, her slaves, and her plantations, her bales of goods, her gold and silver, and leave her only herself, what would there be in all the rest worth the labour of a struggle? Her barren acres, her brave, simple, generous, honest-hearted, hardy race of men, her liberty, her fame, her integrity they look upon with the most sovereign contempt and indifference, and would be ready to sacrifice them all for the purchase of some new golden settlement, ‘some happier island in the watery waste—

21They would defend their country not as her children, but as her masters; as a property, not as a state. There may be the same pride and luxury in other classes of men, but they are accompanied with other feelings, and drawn from other sources. It has been a customary compliment to consider those as best entitled to come forward conspicuously in defence of their country who had what is called the greatest stake in it. This is perhaps true of the real, old hereditary nobility and gentry, of those who find their names enrolled high in the annals of their country, whose affections have grown to her soil as it were in a long course of centuries, who have an interest in looking forward to posterity, and a pride in looking back upon their ancestors, who have not only present possessions and advantages to defend, but feelings of inveterate prejudice and inbred honour to defend them. The loss of respect, or of their former privileges, is a change which to them appears like something out of the course of nature, to which no force or accidental circumstances can ever reconcile them. They are also men of liberal education; and this is a great point gained. There is certainly this advantage in a classical education, if not counteracted by other causes, that it gives men long views; it accustoms the mind to take an interest in things foreign to itself, to love virtue for its own sake, to prefer fame to life, and glory to riches, and to fix our thoughts on the great and permanent instead of narrow and selfish objects. It teaches us to believe that there is something really great and excellent in the world, surviving all the shocks of accident and fluctuations of opinion, and to feel respect for that which is made venerable by its nature and antiquity instead of that low and servile dread which bows only to present power and upstart authority. It is hard to find in minds otherwise formed either a delicate sense of honour, or an inflexible regard to truth and justice. But the spirit of trade is the very reverse of all this. It is the principle of this set of men to cry ‘Long life to the conqueror,’ to feel a contempt for all obligations that are not founded in self-interest, and to consider all generous pursuits and the hope of unfading renown as romance and folly. ‘Virtue is not their habit, they are out of themselves in any course of conduct recommended only by conscience and glory.’ They would not give a hundred hogsheads of sugar or a half-year’s income for all the posthumous fame that was ever acquired in the world. If things should unhappily ever come to extremities, they are not the people who will retrieve them, either by their exertions or example. They have neither grand and elevated views, nor the warm, genuine feelings of nature. They have no principles of action. Irresolute, temporizing, every thing is with them made a subject of selfish calculation. Their friendships as well as their 22enmities are the creatures of the occasion. Confident, insolent in the day of success, and while their cause is triumphant, they are as soon dejected and driven to despair, when they find the tide turned against them. Fortune is with them the first of goddesses: success the only title to authority and respect; and possession the truest right. Accustomed to all the fluctuations of hope and fear, they consider nothing stable in human affairs; thrown into the possession of power and affluence by accidents which they know not how to account for, it can hardly seem strange to them that they should again be stripped of them. They do not ‘lay the fault upon themselves but on their stars, that they are underlings.’ If I hear a man say that we are to give up our public principles whenever circumstances render it necessary, that we are to inquire upon all occasions not what is right, but what is prudent to be done, that those feelings, which lead us to adhere to the cause of truth and justice if at all unpopular, or to incur any personal risk or inconvenience in defending what is right, are weak and vulgar prejudices, I know that that man will be first to truckle to an enemy, and the last voluntarily to risk his life in defence of his independence.

The courage of the soldier and the citizen are essentially different. The one is momentary and involuntary; the other permanent and voluntary. It is one thing to do all in your power to repel danger when it is unavoidable, and another to expose yourself to it when you may avoid going into it. Fear, or rashness, or necessity may be supposed to kindle all the fury of battle: but principle alone can make us willing to return to the charge after defeat. It is for this re-action that we ought to be chiefly prepared. For this nothing can prepare us but a true love of our country, not taken up as a fashion, but felt as a duty; a spirit of resistance not measured by our convenience, but by the strength of our attachment and the real value of the object; but steady enthusiasm; but a determination never to submit while hope or life remained, and an indifference to every thing else but that one great object.

What resistance has Holland ever made to the power of France from the first moment? Commerce had spread its sordid mantle completely over her. Wrapped closely up in this, she fell without resistance and without a groan: she was not of a temper to fall in love with danger, to court disasters. Since that time she has not made a struggle or breathed a sigh for her release, but lies supine, secure, unmoved, and torpid,

Two hundred years of commerce and riches, which had gone over 23her, since, in that noble struggle for thirty years together, she had defied the whole power and the utmost vengeance of Spain, had prepared her for this striking change. But England is not yet quite commercial: the spirit of trade has not spread its poison through the whole mass of our blood and vital juices! As I do not wish that England (with all her high hopes, and called to a far different destiny) may ever share the fate of Holland, I do not wish that she may ever resemble her in herself; that every other feeling should give way to that of interest alone, but that she may tremble at ever realizing the warning picture of the poet,

Though a state cannot look to its commerce for its security, it may be involved in endless difficulty and danger by the views of commercial aggrandizement. The views of men wholly engrossed in such pursuits are altogether low and mechanical. If they see far, it is always in a straight line before them; their sagacity is confined to what immediately concerns their own interest. They are so intent upon that one object that they overlook every thing else; and their eagerness to accumulate is such, that they would rather hazard all than relinquish a pursuit which promises them some new acquisition. While they are successful, it is impossible to persuade them that they ever can be otherwise, or to restrain their rashness by any considerations of prudence or humanity. Actuated only by gross, palpable objects, and full of themselves, they laugh at all distant danger. All general reasonings on the principles of human nature, or the operation of causes by which they do not find themselves influenced, appear to them perfectly futile and visionary. ‘They think there is nothing real but that which they can handle; which they can measure with a two-foot rule, which they can tell upon ten fingers.’ As they believe money to be the only substantial good, they are also persuaded that it is the only instrument of power. With this they think themselves invulnerable, and that the more of it they have, the more secure they are. As long as their credit remains unimpaired, and their remittances are regularly made, they consider the fate of battles and the intrigues of cabinets as of very little comparative importance. They look up with more awe and admiration to a stock-jobbing broker surrounded with his clerks than they do to a victorious general at the 24head of his army. The rise and fall of stocks, and the demand for our manufactures abroad, are in their opinion the only criterions of national prosperity. On the other hand, whatever affects their own interest, the loss of an island, or the stopping up of a port, is found immediately to threaten the ruin of the country. Their fears are as rash and groundless as their confidence. Every thing in which they themselves are concerned is viewed through a magnifying medium, and demands all our vigilance and attention, while every thing else dwindles into insignificance. I therefore think there ought to be as little connection as possible between the measures of government and the maxims of the Exchange, and that the interests of a great empire ought not to be managed by a company of factors.

I have thus expressed the sentiments which occurred to me on the present situation of our affairs, and some of the steps which led to it. I have done this as freely and unreservedly as I could, because if they are wrong, it is not likely that they will be much attended to; but if they are right, they may be of some use. And I conceive that even they who may think the view I have taken of the measures of the last administration, and the application of particular observations to our own conduct altogether unfounded, will not deny the truth of the general principles on which they are built. Or that the sentiments of justice, of honour, of reason and liberty, by which I think our views and conduct ought to have been regulated, can be too deeply impressed on our minds.

This work was published in 1819 with the following title-page:—‘Political Essays, with Sketches of Public Characters. By William Hazlitt. “Come, draw the curtain, shew the picture.” London: Printed for William Hone, 45, Ludgate Hill. 1819.’ A ‘Second edition,’ with the same title and motto, ‘published by John Templeman, 39, Tottenham-Court-Road; and Simpkin and Marshall, Stationers’-court,’ appeared in 1822, but was probably a mere re-issue. The text of the 1819 edition is here reprinted.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Dedication | 29 |

| Preface | 31 |

| The Marquis Wellesley | 47 |

| Mr. Southey, Poet Laureat | 48 |

| Mr. Southey’s New Year’s Ode | 49 |

| Dottrel-catching | 51 |

| The Bourbons and Buonaparte | 52 |

| Vetus | 57 |

| On the Courier and Times Newspapers | 58 |

| Illustrations of Vetus | 63 |

| On the late War | 96 |

| Prince Maurice’s Parrot | 101 |

| Whether the Friends of Freedom can entertain any sanguine hopes of the Favorable Results of the ensuing Congress | 103 |

| The Lay of the Laureate | 109 |

| Mr. Owen’s ‘New View of Society,’ &c. | 121 |

| Speeches of Charles C. Western, Esq. M.P. and Henry Brougham, Esq. M.P. | 127 |

| Mr. Coleridge’s Lay Sermon | 138 |

| —— —— Statesman’s Manual | 143 |

| —— —— Lay Sermon | 152 |

| Buonaparte and Muller | 154 |

| Illustrations of the Times Newspaper | 155 |

| Mr. Macirone’s ‘Interesting Facts relating to the Fall and Death of Joachim Murat, King of Naples’ | 177 |

| Wat Tyler and the Quarterly Review | 192 |

| The Courier and Wat Tyler | 200 |

| Mr. Southey’s Letter to William Smith, Esq. | 210 |

| 28On the Spy-System | 232 |

| On the same subject | 234 |

| On the Treatment of the State Prisoners | 238 |

| The Opposition and the Courier | 240 |

| England in 1798, by S. T. Coleridge | 241 |

| On the Effects of War and Taxes | 243 |

| Character of Mr. Burke | 250 |

| On Court Influence | 254 |

| On the Clerical Character | 266 |

| What is the People? | 283 |

| On the Regal Character | 305 |

| ‘The Fudge Family in Paris’ | 311 |

| Character of Lord Chatham | 321 |

| —— of Mr. Burke | 325 |

| —— of Mr. Fox | 337 |

| —— of Mr. Pitt | 346 |

| ‘Pitt and Buonaparte’ | 350 |

| An Examination of Mr. Malthus’s Doctrines | 356 |

| On the Originality of Mr. Malthus’s Essay | 361 |

| On the Principles of Population as affecting the Schemes of Utopian Improvement | 367 |

| On the Application of Mr. Malthus’s Principle to the Poor Laws | 374 |

| Queries relating to the Essay on Population | 381 |

The tried, steady, zealous, and conscientious advocate of the liberty of his country, and the rights of mankind;—

One of those few persons who are what they would be thought to be; sincere without offence, firm but temperate; uniting private worth to public principle; a friend in need, a patriot without an eye to himself; who never betrayed an individual or a cause he pretended to serve—in short, that rare character, a man of common sense and common honesty,

I am no politician, and still less can I be said to be a party-man: but I have a hatred of tyranny, and a contempt for its tools; and this feeling I have expressed as often and as strongly as I could. I cannot sit quietly down under the claims of barefaced power, and I have tried to expose the little arts of sophistry by which they are defended. I have no mind to have my person made a property of, nor my understanding made a dupe of. I deny that liberty and slavery are convertible terms, that right and wrong, truth and falsehood, plenty and famine, the comforts or wretchedness of a people, are matters of perfect indifference. That is all I know of the matter; but on these points I am likely to remain incorrigible, in spite of any arguments that I have seen used to the contrary. It needs no sagacity to discover that two and two make four; but to persist in maintaining this obvious position, if all the fashion, authority, hypocrisy, and venality of mankind were arrayed against it, would require a considerable effort of personal courage, and would soon leave a man in a very formidable minority. Again, I am no believer in the doctrine of divine right, either as it regards the Stuarts or the Bourbons; nor can I bring myself to approve of the enormous waste of blood and treasure wilfully incurred by a family that supplanted the one in this country to restore the others in France. It is to my mind a piece of sheer impudence. The question between natural liberty and hereditary slavery, whether men are born free or slaves, whether kings are the servants of the people, or the people the property of kings (whatever we may think of it in the abstract, or debate about it in the schools)—in this country, in Old England, and under the succession of the House of Hanover, is not a question of theory, but has been long since decided by certain facts and feelings, to call which in question would be equally inconsistent with proper respect to the people, or common decency towards the throne. An English subject cannot call this principle in question without renouncing his country; an English prince cannot call it in question without disclaiming his title to the crown, which was placed by our ancestors on the head of his ancestors, on no other ground and for no other possible purpose than to vindicate this sacred 32principle in their own persons, and to hold it out as an example to posterity and to the world. An Elector of Hanover, called over here to be made king of England, in contempt and to the exclusion of the claims of the old, hereditary possessors and pretenders to the throne, on any other plea except that of his being the chosen representative and appointed guardian of the rights and liberties of the people (the consequent pledge and guarantee of the rights and liberties of other nations) would indeed be a solecism more absurd and contemptible than any to be found in history. What! Send for a petty Elector of a petty foreign state to reign over us from respect to his right to the throne of these realms, in defiance of the legitimate heir to the crown, and ‘in contempt of the choice of the people!’ Oh monstrous fiction! Miss Flora Mac Ivor would not have heard of such a thing: the author of Waverley has well answered Mr. Burke’s ‘Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs.’[4] Let not our respect for our ancestors, who fought and bled for their own freedom, and to aid (not to stifle) the cause of freedom in other nations, suffer us to believe this poor ideot calumny of them. Let not our shame at having been inveigled into crusades and Holy Alliances against the freedom of mankind, suffer us to be made the dupes of it ourselves, in thought, in word, or deed. The question of genuine liberty or of naked slavery, if put in words, should be answered by Englishmen with scorn: if put in any other shape than 33words, it must be answered in a different way, unless they would lose the name of Englishmen! An Englishman has no distinguishing virtue but honesty: he has and can have no privilege or advantage over other nations but liberty. If he is not free, he is the worst of slaves, for he is nothing else. If he feels that he has wrongs and dare not say so, he is the meanest of hypocrites; for it is certain that he cannot be contented under them.—This was once a free, a proud, and happy country, when under a constitutional monarchy and a Whig king, it had just broken the chains of tyranny that were prepared for it, and successfully set at defiance the menaces of an hereditary pretender; when the monarch still felt what he owed to himself and the people, and in the opposite claims which were set up to it, saw the real tenure on which he held his crown; when civil and religious liberty were the watch-words by which good men and true subjects were known to one another, not by the cant of legitimacy; when the reigning sovereign stood between you and the polluted touch of a bigot and a despot who stood ready to seize upon you and yours as his lawful prey; when liberty and loyalty went hand in hand, and the Tory principles of passive obedience and non-resistance were more unfashionable at court than in the country; when to uphold the authority of the throne, it was not thought necessary to undermine the privileges or break the spirit of the nation; when an Englishman felt that his name was another name for independence, ‘the envy of less happier lands,’ when it was his pride to be born, and his wish that other nations might become free; before a sophist and an apostate had dared to tell him that he had no share, no merit, no free agency, in the glorious Revolution of 1688, and that he was bound to lend a helping hand to crush all others, that implied a right in the people to chuse their own form of government; before he was become sworn brother to the Pope, familiar to the Holy Inquisition, an encourager of the massacres of his Protestant brethren, a patron of the Bourbons, and jailor to the liberties of mankind! Ah, John Bull! John Bull! thou art not what thou wert in the days of thy friend, Arbuthnot! Thou wert an honest fellow then: now thou art turned bully and coward.