Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JANUARY 5, 1897. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 897. | two dollars a year. |

It was I who called him the Little Bishop. His name was Phillips Brooks Sanderson, but one seldom heard it at full length, since "Phil" was quite enough for an urchin just in his first trousers, and those assumed somewhat prematurely. He was "Phil," therefore, to the village, but always the dear lovable Little Bishop to me. His home was in Bonnie Eagle; it was only because of his mother's illness that he was spending the summer with his uncle and aunt in Pleasant River. I could see the little brown house from my window. The white road, with strips of tufted green between the wheel tracks, curled dustily up to the very door-step, and inside the wire screen-door was a wonderful drawn-in rug, shaped like half a pie, with "Welcome" in saffron letters on its gray surface. I liked the Bishop's aunt; I liked to see her shake the "Welcome" rug before breakfast, flinging the cheery word out into the summer sunshine like a bright greeting to the new day; I liked to see her go to the screen-door a dozen times a day; open it a crack, and chase an imaginary fly from the sacred precincts within; I liked to see her come[Pg 234] up the cellar steps into the side garden, appearing mysteriously as from the bowels of the earth, carrying a shining pan of milk in both hands, and disappearing through the beds of hollyhocks and sunflowers to the pig-pen or the hen-house.

I had not yet grown fond of the uncle, and neither had Phil, for that matter; in fact Uncle Abner was rather a difficult person to grow fond of, with his fiery red beard, his freckled skin, and his gruff way of speaking—for there were no children in the brown house to smooth the creases from his forehead or the roughness from his voice.

I was sitting under the shade of the great maple one morning early when I first saw the Little Bishop. A tiny figure came down the grass-grown road leading a cow by a rope. If it had been a small boy and a small cow, a middle-sized boy and an ordinary cow, or a grown man and a big cow, I might not have noticed them; but it was the combination of an infinitesimal boy and a huge cow that attracted my attention. I could not guess the child's years; I only knew that he was small for his age, whatever it was. The cow was a dark red beast with a crumpled horn, a white star on her forehead, and a large surprised sort of eye. She had, of course, two eyes, and both were surprised, but the left one had an added hint of amazement in it by virtue of a few white hairs lurking accidentally in the centre of the eyebrow.

The boy had a thin sensitive face and curly brown hair, short trousers patched on both knees, and a ragged straw hat on the back of his head. He pattered along behind the cow, sometimes holding the rope with both hands, and getting over the ground in a jerky way, as the animal left him no time to think of a smooth path for bare feet. The Sanderson pasture was a good half-mile distant, I knew, and the cow seemed in no hurry to reach it; accordingly she forsook the road now and then, and rambled in the hollows, where the grass was sweeter, to her way of thinking. She started on one of these exploring expeditions just as she passed the great maple, and gave me time to call out to the little fellow, "Is that your cow?"

He blushed and smiled, tried to speak modestly, but there was a quiver of pride in his voice as he answered, suggestively, "It's—nearly my cow."

"How is that?" I asked.

"Why, when I drive her twenty-nine more times to pasture 'thout her gettin' her foot over the rope or 'thout my bein' afraid, she's goin' to be my truly cow, Uncle Abner says. Are you 'fraid of cows?"

"Ye-e-es," I confessed, "I am, just a little. You see, I am nothing but a grown-up woman, and boys can't understand how we feel about cows."

"I can! They're awful big things, aren't they?"

"Perfectly enormous! I've always thought a cow coming towards you one of the biggest things in the world."

"Yes; me too. Don't let's think about it. Do they hook people so very often?"

"No, indeed; in fact one scarcely ever hears of such a case."

"If they stepped on your bare foot they'd scrunch it, wouldn't they?"

"Yes, but you are the driver, you mustn't let them do that; you are a free-will boy, and they are nothing but cows."

"I know; but p'r'aps there is free-will cows, and if they just would do it you can't help being scrunched, for you mustn't let go of the rope nor run, Uncle Abner says."

"No, of course that would never do."

"Does all the cows where you live go down into the boggy places when you're drivin' 'em to pasture, or does some stay in the road?"

"There aren't any cows or any pastures where I live; that's what makes me so foolish. Why does yours need a rope?"

"She don't like to go to pasture, Uncle Abner says. Sometimes she'd druther stay to home, and so when she gets part way there she turns round and comes backwards."

"Dear me!" I thought, "what becomes of this boy mite if she has a spell of going backwards? Do you like to drive her?" I asked.

"N—no, not erzackly; but, you see, it'll be my cow if I drive her twenty-nine more times 'thout her gettin' her foot over the rope and 'thout my bein' afraid," and a beaming smile gave a transient brightness to his harassed little face. "Will she feed in the ditch much longer?" he asked. "Shall I say 'Hurrap'? That's what Uncle Abner says—'Hurrap!' like that, and it means to hurry up."

It was rather a feeble warning that he sounded, and the cow fed on, peacefully. The little fellow looked up at me confidingly, and then glanced back at the farm to see if Uncle Abner were watching the progress of events.

"What shall we do next?" he asked.

I delighted in that warm, cozy little "we"; it took me into the firm so pleasantly. I am a weak prop indeed when it comes to cows, but all the manhood in my soul rose to arms when he said, "What shall we do next?" I became alert, courageous, ingenious, on the instant.

"What is her name?" I asked, sitting up straight in the hammock.

"Buttercup; but she don't seem to know it very well."

"Never mind; you must shout 'Buttercup!' at the top of your voice, and twitch the rope hard; then I'll call, 'Hurrap!' with all my might at the same moment."

We did this; it worked to a charm, and I looked affectionately after my Little Bishop as the cow pulled him down Aunt Betty's hill.

The lovely June days wore on. I saw Phil frequently, but the cow was seldom present at our interviews, as he now drove her to the pasture very early in the morning, the journey thither being one of considerable length and her method of reaching the goal being exceedingly round-about. Uncle Abner had pointed out the necessity of getting her into the pasture at least a few minutes before she had to be taken out again, and though I didn't like Uncle Abner, I saw the common-sense of this remark. I sometimes caught a glimpse of them at sundown as they returned from the pasture to the twilight milking, Buttercup chewing her peaceful cud, her soft white bag of milk hanging full, her surprised eye rolling in its accustomed "fine frenzy." The frenzied roll did not mean anything, the Bishop and I used to assure each other; but if it didn't, it was an awful pity she had to do it, the Bishop thought, and I agreed. To have an expression of eye that means murder, and yet to be a perfectly virtuous and well-meaning animal, this is a calamity which, if fully realized, would injure a cow's milk-producing activities seriously, I should think.

I was looking at the sun one evening as it dropped like a ball of red fire into Wilkins's Woods, when the Little Bishop passed.

"It's the twenty-ninth night," he called, joyously.

"I am so glad," I answered, for I had often feared some accident might prevent his claiming the promised reward. "Then to-morrow Buttercup will be your own cow?"

"I guess so. That's what Uncle Abner said. He's off to Bonnie Eagle now, but he'll be home to-night, and mother's going to send my new hat by him. When Buttercup's my own cow I wish I could change her name and call her Red Rover, but p'r'aps her mother wouldn't like it. When she b'longs to me, mebbe I won't be so 'fraid of gettin' hooked and scrunched, because she'll know she's mine, and she'll go better. I haven't let her get snarled up in the rope one single time, and I don't show I'm afraid, do I?"

"I should never suspect it for an instant," I said, encouragingly. "I've often envied you your bold, brave look!"

He appeared distinctly pleased. "I haven't cried, either, when she's dragged me over the pasture bars and peeled my legs. Bill Jones's little brother Charlie says he ain't afraid of anything, not even bears. He says he would walk right up close and cuff 'em if they dared to yip; but I ain't like that!"

I told Aunt Betty that it was the Bishop's twenty-ninth night, and that the big red cow was to be his on the morrow.

"Well, I hope it'll turn out that way," she said. "But I ain't a mite sure that Abner Sanderson will give up that cow when it comes to the point. It won't be the first time[Pg 235] he's tried to crawl out of a bargain with folks a good deal bigger than Phil, for he's close, Abner is! To be sure, Phil's father bought all his stock for him years ago, and set him up on the farm; perhaps that'll make some difference, now he's died, and left nothing to his widder. Abner has hired help in July and August, so he can get the cow to the pasture easy enough without Phil. I wish you'd go up there to-night, and ask Mis' Sanderson if she'll lend me half her yeast-cake, and I'll lend her half of mine a Saturday."

I was used to this errand, for the whole village of Pleasant River would sometimes be rocked to the very centre of its being by simultaneous desire for a yeast-cake. As the nearest repository was a mile and a half distant, as the yeast-cake was valued at two cents and wouldn't keep, as the demand was uncertain, being dependent entirely on a fluctuating desire for "riz bread," the Edgewood store-keeper refused to order more than three yeast-cakes a day at his own risk. Sometimes they remained on his hands a dead loss; sometimes eight or ten persons would "hitch up" and drive from distant farms for the coveted article, only to be met with the flat, "No, I'm all out o' yeast-cake; Mis' Simmons took the last; mebbe you can borry half o' hern, she hain't much of a bread-eater."

So I climbed the hill to Mrs. Sanderson's, knowing my daily bread depended on the successful issue of the call. As I passed by the corner of the barn, I paused behind a great clump of elderberry-bushes, for I heard the timid voice of the Little Bishop and Uncle Abner's gruff tone. I did not wish to interrupt nor overhear a family interview, and I thought they might walk on as they talked; but in a moment I heard Uncle Abner sit down on a stool by the grindstone as he said:

"Well, now, Phillips Brooks, we'll talk about the red cow. You say you've drove her a month, do ye? And the trade between us was that if you could drive her a month without her getting the rope over her foot and without bein' afraid, you was to have her. That's straight, ain't it?" The Bishop's face burned with excitement, his gingham shift rose and fell as if he were breathing hard, but he only nodded assent and said nothing. "Now," continued Uncle Abner, "have you made out to keep the rope from under her feet?"

"She 'ain't got t-t-tangled up one s-single time," said Phil, stuttering in his excitement, but looking up with some courage from his bare toes, with which he was assiduously ploughing the earth.

"So far, so good. Now 'bout bein' afraid. As you seem so certain of gettin' the cow, I suppose you hain't been a mite scared, hev you? Honor bright, now!"

"I—I—not but just a little mite. I—"

"Hold up a minute. Of course you didn't say you was afraid, and didn't show you was afraid, and nobody knew you was afraid, but that ain't the way we fixed it up. You was to call the cow yourn if you could drive her to the pasture for a month without bein' afraid. Own up square now, hev you ben afraid?"

A long pause, then a faint "Yes."

"Where's your manners?"

"I mean yes sir."

"How often? If it hain't ben too many times mebbe I'll let ye off, though you're a reg'lar girl-boy, and'll be runnin' away from the cat bimeby. Has it ben—twice?"

"Yes," and the Little Bishop's voice was very faint now, and had a decided tear in it.

"Yes what?"

"Yes, sir."

"Has it ben four times?"

"Y-es, sir." More heaving of the gingham shirt.

"Well, you air a coward! How many times? Speak up now."

More digging of the bare toes in the earth, and one premonitory tear stealing from under the downcast lids, then:

"A little most every day, and you can keep the cow," wailed the Bishop, as he turned abruptly and fled behind the barn, where he flung himself into the green depths of a tansy bed, and gave himself up to unmanly tears.

I had heard more than I wished, for I had been rooted to the spot, not so much because of my interest in Phil as that I did not like to vex Uncle Abner by making him aware of my unintentional presence. I did not dare seek and comfort my Little Bishop sobbing in the tansy bed, the brand of coward on his forehead, and, what was much worse, the fear in his heart that he deserved it. I hurried home across the fields, quite forgetting my errand, and told Aunt Betty, with tears in my eyes, that I would rather eat buttermilk bread for a week than have one of Uncle Abner's yeast-cakes in the house. I acknowledged that he had been true to his word and had held to his bargain, but I could not forgive his making so hard a bargain with my timid Little Bishop.

Aunt Betty finally heard from Mrs. Sanderson, through whom all information was sure to filter if you gave it time, that Uncle Abner despised a coward, that he considered Phil a regular mother's-apron-string boy, and that he was "learnin'" him to be brave.

Bill Jones, the hired man, now drove Buttercup to pasture, though whenever Uncle Abner went to Moderation of Bonnie Eagle, as he often did, I noticed that Phil took the hired man's place. I often joined him on these anxious expeditions, and a like terror in both our souls, we attempted to train the red cow and give her some idea of obedience.

"If she only wouldn't look at us that way we would get along real nicely with her, wouldn't we?" prattled the dear Bishop, straggling along by my side; "and she is a splendid cow; she gives twenty-one quarts a day, and Uncle Abner says it's more'n half cream."

I assented in all this, thinking that if Buttercup would give up her habit of turning completely round in the road to roll her eyes and elevate her white-tipped eyebrow, she might indeed be an enjoyable companion; but in her present state of development her society would not be agreeable to me even did she give sixty-one quarts of milk a day. Furthermore, when I found that she never did any of these reprehensible things with Bill Jones, I began to believe cows more intelligent creatures than I had supposed them to be, and I was indignant to think Buttercup could count so confidently on our weakness.

One evening, when she was more than usually exasperating, I said to the Bishop, who was bracing himself to keep from being pulled into a way-side brook where she loved to dabble, "Bishop, do you know anything about the superiority of mind over matter?" No, he didn't, though it was not a fair time to ask the question, for he had sat down in the road to get a better purchase on the rope.

"Well, it doesn't signify. What I mean is that we can die but once, and it is a glorious thing to die for a great principle. Give me that rope. I can pull like an ox in my present frame of mind. You run down on the opposite side of the brook, take that big stick, wade right in—you are barefooted—brandish the stick, and, if necessary, do more than brandish. I would go myself, but it is better she should recognize you as a master, and I am in as much danger as you are, anyway. She may try to hook you, of course, but you must keep waving the stick—die brandishing, Bishop, that's the idea! She may turn and run for me, in which case I shall run too; but I shall die running, and Aunt Betty can bury us under our favorite sweet-apple-tree!"

The Bishop's soul was fired by my eloquence. The blood mounted to our brains simultaneously, and we were flushed with a splendid courage in which death looked a mean and paltry thing compared with vanquishing that cow. She had already stepped into the pool, but the Bishop waded in towards her, moving the alder branch menacingly. She looked up with the familiar roll of the eye that had done her such good service all summer, but she quailed beneath the stern justice of the Bishop's gaze.

In that moment she felt ashamed, I know, of the misery she had caused that helpless mite. At any rate, actuated by fear, surprise, or remorse, she turned and walked back into the road without a sign of passion or indignation, leaving us rather disappointed at our easy victory. To be prepared for a violent death and receive not even a scratch makes one fear that one may possibly have overestimated the danger.

Well, we were better friends after that, all three of us, and understood one another better as the summer grew into autumn and the great maple hung a flaming bough of scarlet over the hammock. Uncle Abner found the Bishop very useful at picking up potatoes and gathering apples, but he was going to leave Pleasant River as soon as the harvesting was over.

One warm evening Aunt Betty and I were borrowing half a yeast-cake, and incidentally sitting on Mrs. Sanderson's steps at sunset. Buttercup was being milked on the grassy slope near the shed door. As she walked to the barn, after giving up her twelve quarts of yellow milk, she bent her neck and snatched a hasty bite from a pile of turnips lying temptingly near. In her haste she got more of a mouthful than would be considered good manners even among cows, and as she disappeared in the barn door I could see a forest of green tops hanging from her mouth, while she painfully attempted to grind up the mass of stolen material without allowing a single turnip to escape.

It grew dark soon after, and we went into the house, but as we closed the door I heard the cow coughing, and said to Mrs. Sanderson, "Buttercup was too greedy, and now she has indigestion."

The Bishop always went to bed at sundown, and Uncle Abner had gone to the doctor's to have his hand dressed, for he had hurt it in some way in the threshing-machine. Bill Jones came in presently and asked for him, saying that the cow coughed more and more, and it must be that something was wrong, but he could not get her to open her mouth wide enough for him to see anything.

When Uncle Abner had driven into the yard, he came in for a lantern, and went directly out to the barn. After an hour or more, in which we had forgotten the whole occurrence, he came in again. "I'm blamed if we ain't goin' to lose that cow," he said. "Come out, will ye, Hannah, and hold the lantern? I can't do anything with my right hand in a sling, and Bill is the stupidest critter in the country."

We all went out to the barn except Aunt Betty, who ran down the path to see if her son Moses had come home from Saco, and could come up to take a hand in the exercises.

Buttercup was in a bad way; there was no doubt of it. Something, one of the turnips, presumably, had lodged in her throat, and would move neither way, despite her attempts to dislodge it. Her breathing was labored, and her eyes bloodshot from straining and choking. Once or twice they succeeded in getting her mouth partly open, but before they could fairly discover the cause of trouble she had wrested her head away.

"I can see a little tuft of green sticking straight up in the middle," said Uncle Abner, while Bill Jones and Moses held a lantern on each side of Buttercup's head; "but, land! it's so far down, and such a mite of a thing, I couldn't git it even if I could use my right hand. S'pose you try, Bill."

Bill hemmed and hawed, and confessed he didn't care to try. Buttercup's teeth were of good size and excellent quality, and he had no fancy for leaving his hand within her jaws. He said he was no good at that kind of work, but that he would help Uncle Abner hold the cow's head; that was just as necessary, and considerable safer.

Moses was more inclined to the service of humanity, and did his best, wrapping his wrist in a cloth, and making desperate but ineffectual dabs at the slippery green turnip-tops in the reluctantly opened throat. But the cow tossed her head and stamped her feet and switched her tail and wriggled from under Bill's hands, so that it seemed altogether impossible to reach the seat of the trouble.

Uncle Abner was in despair, fuming and fretting the more because of his own uselessness. "Hitch up, Bill," he said, "and, Hannah, you drive over to Edgewood for the horse-doctor. I know we can get out that turnip if we can hit on the right tools and somebody to manage 'em right; but we've got to be quick about it or the critter'll choke to death, sure! Your hand's so clumsy, Mose, she thinks her time's come when she feels it in her mouth, and your fingers are so big you can't ketch holt o' that green stuff 'thout its slippin'!"

"Mine's little; let me try," said a timid voice, and turning round, we saw the Bishop, his trousers pulled on over his night-shirt, his curly hair ruffled, his eyes big with sleep.

Uncle Abner gave a laugh of good-humored derision. "You—that's afraid to drive a cow to pasture? No, sir; you hain't got sand enough for this job, I guess!"

Buttercup just then gave a worse cough than ever, and her eyes rolled in her head as if she were giving up the ghost.

"I'd rather do it than see her choke to death!" cried the Bishop in despair.

"Then, by ginger, you can try it, sonny!" said Uncle Abner. "Now this time we'll tie her head up. Take it slow, and make a good job of it."

Accordingly they pried poor Buttercup's jaws open to put a wooden gag between them, tied her head up, and kept her as still as they could, while we women held the lanterns.

"Now, sonny, strip up your sleeve and reach as fur down 's you can! Wind your little fingers in among that green stuff stickin' up there that ain't hardly big enough to call green stuff, give it a twist, and pull for all you're worth. Land! what a skinny little pipe stem!"

The Bishop had stripped up his sleeve. It was a slender thing, his arm; but he had driven the red cow all summer, borne her tantrums, protected her from the consequences of her own obstinacy, taking (as he thought) a future owner's pride in her splendid flow of milk—grown to love her, in a word—and now she was choking to death. Love can put a deal of strength into a skinny little pipe-stem at such a time, and it was only a slender arm and hand that could have done the work.

Phil trembled with nervousness, but he made a dexterous and dashing entrance into the awful cavern of Buttercup's mouth; descended upon the tiny clump of green spills or spikes, wound his little fingers in among them as firmly as he could, and then gave a long, steady determined pull with all the strength in his body. That was not so much in itself, to be sure, but he borrowed a good deal more from some reserve quarter, the location of which nobody knows anything about, but upon which everybody draws in time of need.

Such a valiant pull you would never have expected of the Little Bishop. Such a pull that, to his own utter amazement, he suddenly found himself lying flat on his back on the barn floor, with a very slippery something in his hand, and a fair-sized but rather dilapidated turnip on the end of it.

"That's the business!" cried Moses.

"I could 'a' done it as easy as nothin' if my arm had been a leetle mite smaller," said Bill Jones.

"You're a trump, sonny!" exclaimed Uncle Abner as he helped Moses untie Buttercup's head and took the gag out. "You're a trump, and, by ginger, the cow's yourn!"

The welcome air rushed into Buttercup's lungs and cooled her parched, torn throat. She was pretty nearly spent, poor thing! and bent her head gently over the Little Bishop's shoulder as he threw his arms joyfully about her neck, and whispered, "You're my truly cow now, ain't you, Buttercup?"

"Aunt Betty," I said, as we walked home under the harvest moon, "there are all sorts of cowards, aren't there, and I don't think the Little Bishop is the worst kind, do you?"

Did you ever try to see the wind? It is a very pretty experiment, and one easily performed. In the first place choose a windy day, then secure a polished piece of metal. (A hand-saw will be the easiest to get.) Hold the metallic surface at right angles to the direction of the wind. For example, if the wind is in the north, hold the saw east and west inclined about forty-five degrees to the horizon. Now look carefully at the sharp edge, and you will shortly see the wind pouring over it like a waterfall. Do not try the experiment on a rainy or a murky day.

It was a bright winter morning, and the air outside was frosty and still. A young maid sat in her cozy chamber dressing her golden-brown curls, and as she drew her comb through them she heard a sharp crackling sound that caused her to put on her "thinking-cap," as was her habit when anything out of the common occurred, for she liked to reason out matters in her own quiet way. In her studies she had not as yet reached any allusion to that subtile power known as electricity, so she concluded that the sound must have come from the comb, which she thought was possibly made from the shell of a snapping-turtle. Having settled the affair comfortably in her mind, she finished her toilet hastily, that she might lose no time in announcing her discovery to the family at the breakfast table.

It was the fortunate lot of the head of the family to have been wrecked on a coral reef. I say fortunate, because "All's well that ends well," and inside the reef was a small island, on which he, the head of the family, had the rare experience of witnessing the catching of turtles and the removal of their shells by some native fishermen.

Stories of shipwrecked mariners have been so often told that the incidents of mine need not be repeated here. If, as the Irishman said, the tale of the lost could be told, it would be quite new and interesting; but mine was the very ordinary and commonplace.

After the morning meal was over I told the little maid about it, as I briefly tell you here.

I was on my way to Central America, and had almost reached my journey's end when our ship was wrecked. We struck the reef about nine o'clock at night. It was a very dark and thick night, and the waves dashed over us as we huddled together on the quarter-deck while waiting for daylight to determine in which direction lay possible safety. When the sun rose the next morning we saw approaching us a canoe containing four Indians, with whose assistance we got over the dangerous rocks, and were soon on the island, which was about ten miles distant from the mainland.

It was a beautiful morning, and after the Indians had made us some hot coffee and tortillas (an unleavened corn-cake, baked on hot stones), they went off with the Captain and crew to the wreck, to see if anything could be saved from it, while I lay under the cocoanut-trees enjoying the soft tropical air and congratulating myself on my escape.

When the Captain returned, he determined that he had been driven about twenty-five miles out of his course by a strong current that sets up northward along the eastern coast of Yucatan, for which he had not made proper allowance.

Day was the period of rest for the Indians, and as we all needed sleep, we closed our eyes on the lovely yellow light of the Caribbean Sea, and stretched ourselves under the shelter of the thatched hut.

Towards sunset the Indians awakened us, and gave us another meal of coffee and tortillas, with chile—an uncommonly hot little green pepper. The night promised to be fine, and the Indians predicted a good catch of turtles, as the egg-laying season was nearing its close. So, after an hour or two of chatting, we went down to the edge of the beach, and hid ourselves among the tall salt grasses that lined the shore above high-water mark, where we lay quietly watching the moon rising in its mysterious way out of the sea. Not a sound was heard, save the soft murmuring of the waves as they washed over the reef about half a mile away. We were as still as mice, as the Indians had cautioned us against talking, for the turtles were shy, and very quick to take alarm. After a long wait one of the men touched my arm, and pointed to some dark objects that were slowly crawling out of the water, which was as quiet as a mill-pond. Those dark objects were five big turtles that had come ashore to lay their eggs, which are from two to three inches in length, and sometimes as many as two hundred in number.

WATCHING THE TURTLES COMING OUT OF THE WATER.

WATCHING THE TURTLES COMING OUT OF THE WATER.

This turtle has a small squat head covered with plates of shell, and has a jaw like the beak of a hawk. It has four limbs, or flippers—the hindermost being quite long and winglike—which are armed with a couple of strong nails, with which it digs holes in the sand when it comes ashore to lay its eggs, and it is very fierce at such times if disturbed. When the eggs are laid and carefully covered, Mrs. Turtle waddles off to the water, and gives no further thought of her two hundred or more children which she has left behind.

In the course of time the hot sun hatches out the little chelonians, who burst their shells, and digging their way out of the sand, toddle town the beach to the sea to begin their careers.

Their food consists of sea-weed, crabs, and fishes, and[Pg 238] when they grow to be about two hundred pounds in weight, and their shells become valuable, it behooves them to keep their "weather eyes" open for dark-skinned men when their maternal instincts prompt them to ramble on shelving beaches by the light of the moon.

When the turtles were well up on the shore, the natives rushed out with stout poles, and after a sharp tussle succeeded in turning them over on their backs—no easy task, as they were nearly four feet long, and weighed several hundred pounds.

Once on their backs they were helpless, as they were unable to regain their natural position. Long after midnight we added another to our catch, and then went to rest, leaving the turtles on the beach.

In the morning the natives rolled them over, and after fastening their flippers to stakes driven into the beach, built a light fire on their backs, which caused the plates to curl at the edges, under which a knife was passed and the plates removed, leaving underneath a solid body of bony substance, which is the real protecting shield.

The fire seemed to cause the turtles much pain, as they moaned in quite a human way, but the work was soon over, and on being released, the poor things crawled down the beach and disappeared into the sea. The natives are very careful not to fatally injure them, as they are not very numerous in these waters, and would soon be exterminated if indiscriminately slaughtered, and this is the only variety—the hawksbill, Erectmochelys imbricata, the zoologists call them—that yields the tortoise-shell of commerce. I was told that a second shell soon formed, but it grew as one solid mass, and had no commercial value.

There are thirteen of these plates, and the centre one, on a full-grown specimen, is oftentimes fully fifteen inches long, weighing over half a pound, and ranging from an eighth to a quarter of an inch in thickness.

The finest shell comes from the Eastern Archipelago, around the Celebes, and along the coast of New Guinea, and its value depends on its mottled color; that having a warm transparent yellow tone, with rich brown spots, is the most sought after, and brings the highest price. It is a horny substance, much harder, more brittle, and less fibrous than ordinary horn, and it is very tender, and should not be exposed to severe cold.

In preparing the plates for manufacturing purposes, they are first carefully scraped and washed, the rough edges filed off, and then treated to a bath of boiling water, after which they are subjected to pressure to flatten them. Great care must be used to avoid overheating them, as an excess of heat destroys the transparent and translucent portions, and turns them into a muddy, opaque mass, and thus impairs the market value, so only the most skilful workmen are intrusted with the finer grades, as long practice enables them to work the material at a moderately low temperature.

The shell has an extremely peculiar quality, and with the proper degree of heat can be fashioned into any desired form, which it retains on cooling. All the chips, scraps, and filings that come from working the shells are carefully saved, as they can be softened and pressed into moulds of various shapes.

When thickness is desired, two surfaces are roughened by rasping, and the pieces are then plunged into boiling water, which liquefies the superficial film, and transforms it into a sort of gluey paste, and when the two pieces are pressed together—sometimes between hot irons—a solid mass is obtained, without loss of the valuable qualities so much esteemed. Many cheap compositions and a large amount of stained horn are on the market, which are sold to the unwary as real tortoise-shell, but the fraud is easily detected.

The old Romans held the shell in high favor, and used it very freely to veneer furniture, etc.; and the modern French and German craftsmen decorate their buhl cabinets with it in connection with gold, silver, and copper. To-day it is made into many articles of jewelry, chains, sleeve-buttons, lorgnettes, combs, and other toilet articles. To-morrow it may be out of fashion, and be laid away with camel's-hair shawls.

It was just in the holiday season when Bob and Tommie were delighted to receive a visit from their old friend Captain Hawkins from the sea-shore.

"Just thought I'd run up to town for a few minutes," he said, as if it were necessary for him to explain his presence in town. "You see, I've got a few nevews an' several thousand gran'children what likes to hear from me about Christmas-time, so I goes about Bemberton-by-the-Sea, and all I can find in the shops down thereabouts is the same old things they've had for the last forty year."

"My! Captain Hawkins," said Bob. "Forty years? Are your nephews and grandchildren as old as that?"

"Well, pretty nearly," said the Captain, with an uneasy laugh. "Pretty nearly; and when you get to be forty you get kind of tired o' tin pails and wooden spades and little red jumpin'-jacks an' doll babbies and lemon drops. You boys don't understand that, but wait till you get to be forty year old, and see if I ain't tellin' you the solemnest kind o' truth."

"I guess you're right," said Bob. "I gave my daddy a fine old Jack-in-the-box once, and he laughed like everything at first; but he didn't play with it much, and finally it came back to me again. Pop's pretty nearly forty."

"Yes, an' I guess he laughed like sixty when he saw that Bob-in-a-box."

"Jack-in-a-box," said Bob, with a smile.

"All the same," retorted the old Captain. "Jack-in-a-box, Tommie-in-a-box, or Bob-in-a-box! I never could see why they took the trouble to specify, and if I'd ever have had any children o' my own the Jack-in-a-box would ha' been named after 'em."

"But, Captain, you were just speaking of your grandchildren," said Tommie. "How can you have any grandchildren if you haven't had any children?"

"Oh, that's easy," replied the Captain. "I've adopted 'em. Whenever I see boy or a girl that strikes me as being grand I adopt 'em and call 'em my grandchildren. I guess I've got most a million of 'em scattered round."

"And you've come up to get a million Christmas presents for 'em?" cried Bob, in ecstasy.

"Yep—only there ain't more'n ten of 'em," said the Captain, "that expects anything. I'm goin' to spend ten cents apiece on 'em, but first I've got to get the other eight."

Bob looked at Tommie and Tommie looked at Bob. They were really puzzled to think what the Captain could mean.

"The other eight?" asked Bob.

"Yes," said Hawkins. "You boys ain't the only grandchildren I've got. I love you, but you ain't the only ones I love. There's at least eight more. And what do you suppose I'm goin' to give you all for Christmas?"

The boys gave it up.

"Well," said the Captain, in a whisper, "as I was a-comin' up Broadway a-lookin' into the windows, all of a sudden I see a hoss-car goin' along without a hoss, and I says goodness gracious that's funny. A hoss-car without a hoss, an' what was queerest of all, no trolley! Boys, it scaret me. Me who was never scaret before was scaret then. So I says to a policeman, 'Great scott! Mr. Constable, say, what makes that car go so fast?' 'It's the cable,' says he. My goodness thinks I, I'm sorry for the man that has to pull it, but I jumps aboard one of 'em, pays my five cents, and I have the finest sail from Forty-second Street to the Battery you ever see. No wind, no steam, nothin' in sight to move you, but movin' just the same, just as if you was on a sled slidin' down a hill. It was fine. Goin' around by Fourteenth Street you got lurched like as if you was at sea, an' then with a clear track and no squalls we just bounded down past Canal and Wall streets to Bowlin' Green, and back as slick as anything. And I says to myself, Cap'n Hawkins you've struck it. Don't give the boys no pails, no Jims-in-the-boxes, no spades, no nothin', but get the whole ten of 'em together and give 'em a ride on the cable-car whether you're sorry for the feller that pulls the rope or not. So I'm goin' back to Bemberton for the other eight, and when you boys are free I want you to join us for a sail from Central Park down and back, eh?"

In endeavoring to set before the reader an account of volcanoes, I find a difficulty arising from the fact that very few people have had a chance to see these curious features in the machinery of the earth. In the United States, except in the far-away island district of Alaska, there is not one that has been seen by white men in a state of activity. Many, it is true, exist in the Cordilleran district, between the Canadian and Mexican line, but these are for the most part inaccessible, or, if conveniently placed for the tourists' convenience, are not well suited to show the most important facts of these structures. In writing about the sea, rivers, mountains, glaciers, or any other class of natural objects, our country affords admirable means of illustration, which may serve to convey clear impressions; but the story of volcanoes has to be told without this help.

It is otherwise in the Old World. In Europe, Ætna and Vesuvius have had their activity associated with that of the most cultivated people of the world for about twenty-five centuries; and at many points, as in the valley of the Po or in central France, there are groups of volcanoes which are, though no longer active, in a very perfect state of preservation, within sight of the ways which are traversed by all sight-seeing travellers.

Its convenient position, immediately neighboring to the most beautiful scenery and the greatest treasures of antiquity, has made Vesuvius the volcano of all others which people are likely to see. Probably a hundred climb it for one who ascends any other cone. This is true of our own countrymen who travel as well as those of Europe. This choice of Vesuvius as the volcano of pilgrimage is fortunate, for the reason that though by no means a great specimen of its kind, it is perhaps the most useful to the student of all the thousands that have been examined and described by observers of volcanic phenomena. Therefore, as we should begin our inquiry by seeing what occurs in a volcanic outbreak, and the consequences of these explosions, we will make our study on this beautiful cone.

It is characteristic of this most amiable of volcanoes that of late years it has been in many frequent slight eruptions. The greater number of craters lie sleeping for hundreds or perhaps thousands of years, until they break forth with a fury that sends desolation to the country for miles from the point where the discharge takes place. But Vesuvius, which in its early years was given to furious storms, such as that which overwhelmed Herculaneum and Pompeii eighteen centuries ago, has now become so mild-mannered that men till their vineyards in a fearless way on the slopes which lead up to the crater.

It was my good fortune, about fifteen years ago, on one of several visits to Vesuvius, to find it in an excellent state for an inquiry, which showed me more of what goes on in an eruption, and led to a better insight into the nature of the work than has often been seen by the geologist. There was a slight eruption in progress during the night; from the windows of my lodging in Naples I could see the successive puffs of fire from the crater coming regularly, several each minute. On the following morning there was a strong northerly wind blowing, which made me hope it would be possible to approach the edge of the opening without danger from the falling stones.

Climbing the long way which leads from the railway station on the shores of the bay, through the gardens, villages, and vineyards, I came at length to the observatory which has been established on the border of the area which is reasonably safe in times of trouble. Here I learned that the instruments which show the tremblings of the earth, the small earthquakes which are not perceived by our bodies, indicated that the cone was in a state of constant trembling. The observers who watch this apparatus thought it likely that some time during the day the cone would be blown away in a violent eruption, such as now and then sends the upper part of this and many other volcanoes flying into bits before the fierce blast of the escaping vapors.

My way lay across a wide field of lava and cinders to the place where the steep slope of the upper cone rose to the level where the crater was bombarding the sky with the rapidity of a well-served cannon. The climb up this cone, composed of the bits of lava which had been blown into the air and had fallen down again to the earth, was very laborious. The slope was as steep as a house roof. It took three steps to gain each foot in height. Now and then a stronger blast from the crater would shake the heap, so that it was hard to keep the ground that had been gained. It took a long hour to win the height of four or five hundred feet.

"CREEPING TO THE SHARP EDGE OF THE CRATER, I SAW INTO THE

VERY MOUTH OF THE VOLCANO."

"CREEPING TO THE SHARP EDGE OF THE CRATER, I SAW INTO THE

VERY MOUTH OF THE VOLCANO."

Creeping to the sharp edge of the crater, and peering cautiously into the cavity, I saw into the very mouth of the volcano. The cup-shaped depression was about three hundred feet in diameter, and perhaps half that depth; it passed downward into a well-like pipe, perhaps sixty feet across. The lower part of the pit was, even in the bright sunlight, evidently red-hot. The sides of the pipe were white-hot. On this lower part of the pit, which shone like the eye of a furnace, a mass of very fluid lava was lashing up and down, now rising until it filled the bottom of the basin with its fiery tide, again sinking until it was out of sight.

Each time the lava rose up into the basin it swelled quickly in its middle part, and in the twinkling of an eye it was broken by an explosion of such violence that a quantity of the fluid rock was tossed in fragments high into the air. As this sped upward and downward, it had a chance partly to cool, so that as it fell on the edge of the cone opposite to where I was the roar of its striking was very suggestive of what would happen if the wind should die away.

Although the circumstances were such as made it hard to observe closely, I had no difficulty in seeing that the vapor which blew out at each explosion was steam. As it came forth, it was of the steel-blue color which we see just where the steam comes from the safety-valve of a very hot boiler. As it rose in the crater it soon became white, and as it whirled around me it had the well-known odor of steam, mingled with that of sulphur. In a word, it was evident that it was the vapor of water which was the cause of the explosions.

After I had watched this fascinating scene for about half an hour, with much inconvenience from the heat of the earth and from the shaking of the ground on which I lay, the explosions, which were at first at the rate of three or four each minute, became more and more frequent and violent, and the strong wind began to die away, so that a speedy retreat was necessary to escape the bits of lava, which were now falling heavily. Looking back from the base of the cone, I noted that the explosions came faster and faster, so that it sounded as a continuous roar. It was just as when a locomotive starts on its journey. At the outset we can count the puffs; as the cylinders move faster and faster the escape sounds perfectly continuous.

From the base of the cinder cone there flowed out a small lava stream. This lava was evidently full of steam, which poured forth from all parts of the surface. This is seen in all eruptions. Clouds of steam hung over the streams of lava. They are often visible ten miles or more away from the current of molten rock. In a great eruption the steam given forth from the crater often forms, as it condenses, into rains, that fall in fearful torrents about the cone. It is evident, in a word, that the explosions of volcanoes are formed by the escape of the vapor of water. They are, indeed, like the explosions of boilers.

The question now arises as to the way in which this steam gets into the lava. This we can decide by a simple bit of study of the facts. Taking a map which shows the positions of several hundred active volcanoes, we find at once that they are all situated on the sea floor, from which they rise to form islands on its surface; or, when they are on the continents, they are never more than two hundred and fifty miles from the ocean. This shows that the activity of a volcano is, in some way, related to the sea-water. The only way in which we have been able to[Pg 240] reasonably conceive of the sea bringing about volcanic explosions will now be described.

On the sea floor there is a constant laying down of sediments—limestones, sandstones, etc. We know by the parts of the old sea floor that have been uplifted into dry lands that such beds have been formed, to the thickness in all of one or two hundred thousand feet. These beds are made of small bits of rocky matter and fragments of dead animals and plants. These bits do not fit closely together, and the interspaces are filled with sea water, so that as much as one-twelfth of the rock is usually made up of the fluid in which it was formed. As the ages go on, these beds, with the water which they hold, are buried deeper and deeper by the newer rocks which are laid down upon them, until it may be that they are thus brought to lie twenty miles or more below the surface of the solid earth.

Next let us see as to the heat to which these rocks, with their imprisoned water, are exposed. We know, from a great number of studies which have been made in mines that for each mile we go downward in the earth there is an increase in heat, differing a good deal in different places, but on the average amounting to about one hundred degrees. Therefore, at the depth of twenty miles the imprisoned water would have a temperature of about two thousand degrees. In other words, it would be about as hot as the melted iron that comes from the blast-furnace. Thus heated, the water of the tiny cells of the rock would tend to explode with something like the intensity of gun-powder when it was fired; but as it is sealed in by the great thickness of the rock above, it cannot burst into vapor—just as in the steam-boiler the water stays as a fluid even when it is heated twice as hot as it needs be to become steam when it is not confined.

Let us now suppose that a rift, or, as geologists call it, a fault, is formed in the rocks leading from the surface downward to the level where this very explosive water lies. We can readily fancy that at once the fluid would flash into steam; and as this occurred in the myriads of little cavities in the rocks, which were so heated that they tended to become melted, great quantities of the beds would be forced along with the escaping steam in the form of lava. We see also that this would account for the fact that when the lava comes to the surface of the earth it is commonly filled with steam. When it rises quickly to the air, it is blown to fine dust by the expanding vapor; or if it does not fly to pieces, the little bits of water expand into bubbles, forming pumice or lava, so full of little cavities that it will float on the water like cork.

This view as to the origin of volcanoes, although it would not be accepted by all the students of these strange features of the earth, seems most probable, for the reason that it accounts for the fact that all the seats of present volcanic activity are on the floor of the seas or near their borders, and that the extinct volcanoes which we have had a chance to study lost their activity at a time when, by the changes in the shape of the land, the sea was moved away from the region where they were found. We easily perceive that it is only where, as in the sea, beds are being laid down, one on top of another, that the heat is rising in the rocks, and the water in their crevices becoming hotter; beneath the land the rocks are always becoming less heated, so that the water which they contain is constantly cooling down.

I have spoken of the water contained in the very heated rocks as if it remained in the state of fluid. It is likely that, when in its very hot state, it may be changed into its gases, oxygen and hydrogen, of which it is composed, and that these gases would again become the vapor of water as they rose toward the surface and were somewhat cooled. This and other matters of chemical detail which go on in the wonderful laboratory of the under-earth do not hinder our believing that volcanoes are due to the escape of the water which is constantly being buried in the rocks as they are built. So large is the amount of this water which lies thus buried that probably it amounts to somewhere near as much as is held in all the seas. Were it not for the return of the buried fluid through the volcanoes, the oceans would doubtless be much smaller than they are. They might, indeed, have long since disappeared in the crevices of the earth.

Now again we had changed our course, and were going before the wind directly to the westward. The breeze was light, and better for a small vessel than for a heavy, deep-laden man-of-war, and we might have run away in safety if we chose. That something was up, however, that meant adventure no one could help seeing.

Orders were given, without any bawling or shouting, to get down the top-gallant masts on deck. The crew worked like ants. (I loved them for the way they went about it.) The yards were lowered to the deck as quickly as if they were clothes-poles in a drying-yard. I had never seen anything done so neatly and with such despatch. Our headway decreased, of course, as we lost the use of our upper sails.

Mr. Spencer, who was aloft, reported to the deck: "We're hidden now, Captain Temple," he said. "She might pass within a quarter of a mile of us and never see us."

Purposely I had stepped close to him as he spoke to the Captain, and the latter's reply was as astonishing to me as it apparently startled the officer. Temple was eagerness in every line of his face. He struck his right fist into the palm of his left.

"The closer the better," he exclaimed. Then he turned. "What are the soundings?" he inquired of the bow-legged man who had hastened up. (I have forgotten to state that we had been heaving the lead for the last half-hour.)

"Six fathoms, sir, and shoaling; here it is, sir."

"Prepare to lower away the long-boat, Mr. Bullard," the skipper ordered, after a glance at the lead. "Mount the forward swivel in her, pick a crew, take a boat's compass, and make off due west. Mr. Spencer, you will take command of her. A word with you."

Every one looked at the Captain in astonishment, but no one asked a question or put in a word. As I was one of the crew of the long boat, I helped to get her ready and swing her overboard. The swivel was lashed on the forward gratings, and half a dozen muskets were handed down to her, and we shoved off. Mr. Spencer was pale and nervous. As we left the brig's side we saw that her helm had been put hard down, and that she once more was headed north. There was just enough wind to move her slowly through the water. In three minutes she was lost to sight.

We had been resting on our oars, and now Mr. Spencer spoke for the first time.

"Make no noise," he said. "Pull slowly, straight ahead."

We gave way, trying our best to silence the thumping in the row-locks. So light was the breeze that we could have kept apace of a vessel's sailing. For ten minutes we rowed on, and then we stopped again, and Spencer spoke.'

"Load that swivel and get ready with those muskets," he ordered.

I heard him mutter something in which I caught the words "tomfoolery" and "nonsense," and I looked back over my shoulder. A half-dozen perplexed-looking marines were grouped in the bow, and three sailors were ramming home a charge in the swivel.

"Lads," said Mr. Spencer, "it's Captain Temple's orders to fire into that frigate and get away, if we can. It all depends upon yourselves and the way this boat is handled whether we are blown out of the water, or cut to pieces, or escape with whole skins. I want no talking in the boat."

The man beside me on the thwart pulled his shirt over his head, and several others did likewise. They sat there bare from the waist up, and their torsos looked like those of the men in some of the old engravings in the handsome books I had read at Marshwood.

We were pulling slowly ahead now, and for fully a quarter of an hour we rowed without a break. Then Mr. Spencer called for oars, and we drifted a long time.

"Listen!" said one of the men in the bow, suddenly. He was bending over, with his hand making a hollow back of his ear. Half of the crew did likewise. For a minute I could hear nothing. Then I detected a groaning sound and a ripple of the water. It was the noise of a vessel's sailing.

"I can see her, sir," the bowman said in a hoarse whisper. "She's not five cable-lengths away."

The Lieutenant rose to his feet, and I could see that his hand was trembling as he fumbled in the breast of his jacket. He pulled a boatswain's whistle out and put it to his lips. But before he blew he spoke calmly.

"Bring that gun to bear on her," he said.

"Blow her out of water," spoke up the man beside me, with a chuckle.

What utter foolishness it seemed to me even then (and of a truth it probably was that anyhow) to attack a frigate in a long-boat armed with six muskets and a broadside that you could carry in the crown of your hat! But no one seemed to flinch.

"Give way softly," whispered Mr. Spencer, taking the tiller himself from the cockswain. Then, without warning, the silver pipe shrilled out, and he bawled at the top of his voice, as if he were commanding a ship's crew, instead of a handful of mystified seamen in a cockle-shell: "All hands on deck there, and lively! There's a vessel here astern of us! Port your helm!" He answered this order himself with an, "Ay, ay, sir," and leaning forward shouted, "Fire!"

Close to the water a great shape could be seen. The little gun slap-banged, and almost jumped overboard with the recoil. The six muskets rang; and, animated more by the gesture of Mr. Spencer's hand than the word, we laid back on the oars. We took perhaps some forty strokes or more, when the Lieutenant called for us to cease, with a sound of a hiss betwixt his teeth. The huge shape was now astern of us on the port hand close too. We had rowed across her bow! Now so tense was every nerve, and at such a tension was my mind, that I remembered everything I heard and saw so that I can repeat it to a dot.

The shot and volley had been followed by a confused cry and a great to-do from the direction of the frigate. Now we could hear a confused jumble of accents, and above it the cries of a man's voice in agony, "Oh, oh, I'm killed!" it said distinctly. Then a voice commanded silence, and we could make out every word that passed.

"Can you see anything ahead there, you men forward?" asked a voice so close that it appeared to be directed towards us.

"No, sir; not a thing, sir!" was the answer. If anything, it sounded closer than the first.

Then cool and distinct we caught the following orders, as we sat there holding our breaths, and our hearts beating so loudly that we nearly rocked the boat.

"Ready about! Ready! Ready! Put your helm down, quartermaster."

"Helm's alee, sir."

"Haul taut! Mainsail, haul!" (An anxious waiting pause.) "Head braces! Haul well taut! Let go, and haul!"

So firmly were these words impressed upon me that I never had to learn afterwards the orders for tacking ship.

Now followed a rumbling sound and some shouts and orders, and then a crash and an explosion that ripped the fog and cut great gashes of red flame through the gray opaque wall.

"Gee!" said the man next to me, with a shiver, "if that had caught us, eh!"

"Good-by, Mary Ann!" said the man in front, looking back over his shoulder.

Mr. Spencer was leaning forward. "They think we're off there," he whispered, jerking his thumb over his shoulder. "Lads, you did well."

Now all was silence again, and the frigate gathered headway to the north. We staid where we were.

But now, if I shall live to be a hundred, I can never get one sound from my ears. To the eastward, and beyond the English vessel, sounded the shrilling of a fife. The first bars of "Yankee Doodle" was the tune it played. I almost leaped up to my feet, but the music was soon ended, for a rattling swingeing crash followed a burst of blurred red flame. I could smell the smoke from the frigate's broadside that reached us now. But it was not she that spoke the second time.

"Kill-Devil's got the weather-gauge of her, by Moses!" said the sailor next to me, putting his arm about my neck and giving me a hug.

"Silence in the boat there," ordered Mr. Spencer, angrily.

A roaring crash and confusion of explosions followed. The men in the bow began to laugh hysterically, and even Mr. Spencer joined them.

"The Young Eagle's got under her quarter. She'll rip her hide," he laughed. "Hark! did you hear that? It's the long twelve. Don't cheer, you fools!"

It was well he had given this order, for the men were about to burst into a shout. One of them dropped his oar, and was roundly reprimanded for it. But now a multitude of sounds came from the direction of the fighting-vessels. Groans and orders, cries and firing, and above them all the comments from close about me, that in my ignorance I did not exactly understand.

"Old Johnny Bull's missed stays," roared Mr. Spencer, laughing. "It's the sword-fish and the whale. Stab her again, Captain Temple, stab her again!"

A distinct broadside was heard, and then a cheer, followed by a confused roaring, with high treble shrieks, like a countertenor's note in a chorus.

"Bleed, bleed, bleed," muttered the man next to me.

"That was our cheer," gurgled the cockswain, sawing to and fro in his narrow little box; but no sooner had he spoken than a crash louder and brighter colored than any of the rest ripped out.

"The frigate's broadside!" gasped Mr. Spencer.

All was silence now.

"Heaven help us, they've sunk her!" the Lieutenant said, hoarsely.

No sound for full five minutes.

Three or four shots now, and then silence again. It appeared to me that the fog had lessened. A fine drizzle was falling; and we could see the outlines of a vessel not a quarter of a mile away from us.

"Pull for your lives!" cried Mr. Spencer. "Pull for your lives!"

We gave way together, and the heavy boat was soon hitting up a good pace and burying her nose as she rose and fell on the seas. The Lieutenant took a glance at the small compass, and headed us toward the northwest.

"We're close to Long Island," he said. "I can't make out the Young Eagle at all. That ship's the Britisher."

We had rowed but a few minutes longer when, as if by a miracle, the mist cleared away and the sun shone out. Clear and distinct a big vessel lay off to the eastward. The hated emblem of St. George flew at her peak.

"I thought as much," remarked Mr. Spencer to the cockswain. "She's grounded on the sand bank. That's what Temple counted on."

But hurrah! to the windward of the British vessel was a sight that gave us joy. There was the Young Eagle, eating up into the wind, with her jib-boom hanging, and one of her yards aslant. Somehow Temple had found time to get up his top-gallant masts again, for they were both in place. But now those on board the frigate had espied us; that was plain enough. She was not so large a vessel as[Pg 243] she had first seemed, being of the smaller class, carrying probably not over thirty-two guns at the most. She was badly cut up from the effects of her encounter with the brig, however. Her foretopmast was gone, her mainyard was over the side, and all her running-gear in great confusion. If Captain Temple had been an officer of the regular navy he might have deserved cashiering for such a foolhardy bit of business as attacking a powerful vessel when he might have escaped. He was the only one on board the privateer, however, who had reckoned her at less than forty-four guns, and besides this, after his glance at the lead he knew where he was, and could have pricked his position to a certainty on the map. I know that now.

As Mr. Spencer had said, he surely must have counted on the proximity of the sand bar. If the frigate had been taking careful soundings, she would never have got on to it.

The fresh wind that had spoiled the fog was coming from the northward (I can recall no day in my seafaring life when it blew from so many different points as it had in the last ten hours). But I am wandering from the recital of what occurred, and now to pick it up again.

As I have stated, the frigate had seen us, and proof positive was not wanting, for a puff of smoke from one of the guns of her forward division leaped from her side, and the ball came spattering along toward us.

"Oh, shoot the shot!" laughed one of the bowmen. We were missed by fully a cable's length.

But the wind was against us, and with a good light to observe our progress I noticed that we were making slow headway. The long-boat was intended to be rowed by six oars of a side. Now, owing to the extra men that we carried, there was only room for ten men to do the pulling; and by some mistake the oars that we were wielding were not all of the same length, some of the cutter's having been put in by mistake. The weight of the swivel caused us to be well down by the head, moreover, and the cockswain had to mind his eye to keep headed straight. All idea, of course, of our getting back to the brig that day at least was done for, and to save ourselves we were making for the shore of Long Island, distant about three miles. But we were not out of range of the guns on the frigate, and consequently we were yet in danger.

"Come aft here, you men in the bow!" ordered Mr. Spencer. "She'll row better. Here, stir a foot!"

He looked back, and just as he did so there came another puff of smoke. I saw the ball smash into the top of a wave, strike the water again, and then, slightly deflected, it came right for us. I saw this first, and backed water, giving a shout of fear. The men in the bow gave a leap forward and tumbled in among us, sprawling over our heads and shoulders, and bruising shins and elbows.

If the shot had struck four inches lower we would have been sunk then and there. It caught the gunwale forward, just abreast of the grating on which the swivel was lashed. The poor fellow pulling the bow oar on that side gave a shriek and dropped his oar, clasping both hands about his head. I looked back and saw the blood trickling over his shoulders and through his fingers. A splinter had almost scalped him. We yawed about and shipped the top of a sea, and it looked like the end of matters, for we were out away to within eight inches of the water, and the bow badly stove and broken.

"Cast loose that gun and heave it overboard, two of you," roared Mr. Spencer. "The rest all aft. No! Steady! Debrin, you and Jones keep your place, and pull, do ye hear, pull."

I laid back with all my might, and so did the man next to me. The brave lad in the bow had recovered from the shock of his flesh-wound, and with another fellow cast off the lashings of the swivel and dumped it over the side. I can never forget the sight of that gory man working there with his broad naked back red from his head to his waist. As soon as it was finished he tumbled weakly across the thwart. The men in the stern-sheets were baling with their hands, and one was using Mr. Spencer's cocked hat with great effect, while Jones and I were giving way at top strength and keeping with a great effort the seas from broaching us. As the weight was now in the stern, we could ride, bar accidents, in half safety. And the oars were taken up again. The bowman bent over and tied up his wounded comrade's head with his neckerchief, and for this the other thanked him as he might for some slight courtesy. But a new terror threatened us.

Two successive shots that had been fired at us during the confusion went wide, but now we saw that they were lowering away a great barge over the Englishman's side, and that the men were sliding down into her.

"Heigh! Look there! The Young Eagle's coming down to pick us up, lads," cried Mr. Spencer, turning about in response to a touch on his elbow from the cockswain. "Pull now, and get down to it!"

He headed the long-boat more to the westward, and we could see that the Young Eagle had repaired some of her damage, and had tacked in the direction we were going. She would have passed almost within range of the frigate, but all at once the latter vessel gained sternway (her top-sails had been aback for some few minutes), and she worked off the bar. Our hopes of rescue fell. Turning on her heel, she made out to meet our brig. Now we perceived that the frigate's sides were gashed, and two or three of her ports astern had been knocked into one big opening. But the barge was after us! Every man rowing in our boat could count her strokes. There was no use of making light of it! She was gaining at every jump, lifting high above the top of a sea, and now and again almost disappearing.

There were twelve good men behind those long white sweeps, and they rowed a light boat with speed in her. We were making for the shore now, and grunting with the weight we put into every backward swing. Mr. Spencer was talking to us after the fashion of a cockswain to a racing crew, calling out continually:

"Lift her, boys! That's the ticket! Pull altogether," and so forth.

My mouth grew so dry that I could not swallow, and I could feel my head roll backward and forward. Presently I began to row with my eyes shut, for it seemed an effort to keep my lids from falling. One of the men in the stern began to spatter us with water to refresh us, for the sun was blistering hot by this time. The Lieutenant stopped his cackling.

The stroke oars were being helped at their work by two men pushing as the rowers pulled. I caught a dim sight of this, and wished that some one could lay hold of my sweep with me, for my forearms pained, and I felt gone in the pit of my stomach. How long we rowed that way I do not know, but suddenly I was awakened, as it were, by hearing Mr. Spencer say:

"Lads, you have held your own. Keep at it!" Then in a lower tone he added, "Get ready with those muskets."

This speech had called me to my senses, and it was almost with a shock of surprise that I found myself keeping up the stroke. My eyes had been closed so long that the light dazzled me, and at first I could see nothing, but I felt better than I had before I closed them. And now to say something that is of interest. A refreshment often comes to a man whose muscles have apparently expended all their strength, and thus it was with me. I was working on my heart and nerves alone, on the very life of me, as it were, and to keep this up too long means ruin; that is its limitation. When my eyes could focus, what little breath I had almost checked.

There was the English barge not three hundred yards astern! A despairing look behind me, and I saw that the shore was yet a half-mile off. The sea was breaking in little rolls of white on every hand, and we were in shoal water that had a peculiar yellowish look. I noticed Mr. Spencer kicking off his boots.

I closed my eyes again, for the sweat stung them, and I felt a blackness coming over me. But just then the crack of a musket sounded in front of me. It was followed by another, and a little action began, for the English boat was answering. I was wide-awake once more now, but in a dream apparently. The marines would stand up and fire, and then squat down and load again. I could hear the English bullets sing past.

"Ouch!" exclaimed the cockswain, all at once, as if he had dropped something on his toe.

A ball had struck him on the fleshy part of the thigh, and he sat there rubbing it and talking in such a comical way that the man on the thwart next to me laughed outright in a hoarse, jarring fashion.

A BREAKING WAVE CATCHING US UNDER THE QUARTER WE ROLLED

OVER FAIRLY.

A BREAKING WAVE CATCHING US UNDER THE QUARTER WE ROLLED

OVER FAIRLY.

We were in the surf by this time, and the British barge was half-pistol-shot away, when No. 5 on the starboard hand fell over in a faint; the cockswain got another ball, this time in the wrist, that caused him to let go the tiller, and a breaking wave catching us under the quarter, we rolled over fairly end for end with a clatter. When I came up, there was a tremendous seething and bubbling in my ears, and putting out my arm I managed to catch hold of the tiller-hooks of the overturned boat, and hung on with all my might.

"Help me!" cried a voice. I looked about, and saw the wounded seaman weakly swimming alongside. I extended my hand to him, and observed that eight or ten others were holding fast with straining fingers to the long-boat.

The English barge was backing in carefully and with skill. We were not a cable's length from shore, and making for it hand over hand, swimming with the ease of a porpoise, was Mr. Spencer. I knew it was he by the gleam of gold lace on his high collar. But the seaman had grasped me so tightly that I lost my hold, and there came to me the sense that I was drowning, and did not care at all.

"I'm to be a fairy god-mother to-night," were Mabel's words, as, sitting in the large Indian chair, her eyes glistened with anticipation.

"What will you wear?"

"Oh, one of Millie's old costumes. You may remember that three years ago she took part in the fairies' dream!"

"Yes, I remember."

"Well, by a little alteration the same frock and wings will do for me."

"Are you to have anything to say?"

"I'm to have everything to say. And I'm to wear a crown with a big star in the centre," and up went her hand to indicate the place. "And my wings are showered with diamond dust, and my dress—oh-h, it dazzles my eyes under gas-light! You ought to see the silver spangles!"

"What's the entertainment for, Mabel?"

"Oh, just to amuse people. It is to be given in Mrs. R's—— parlor. Lots of folks will be there. It will be simply gorgeous! You know it's the fad now to have a magician or something to entertain one's friends, and I'm to be sacrificed to-night."

And then up the merry girl jumped to practise a violin solo.

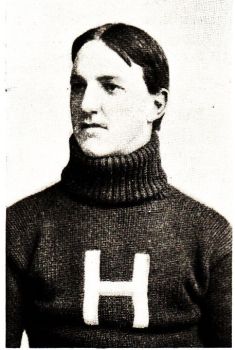

Every reader of Harper's Round Table is familiar with the tales of Hans Andersen and the Brothers Grimm, but it is possible that every one does not appreciate what delightful entertainment they would make. Therefore when Ralph and Margaret wonder what their league could give to replenish the treasury, select an appropriate fairy-tale, and while your committee are making the business arrangements, the persons who are to take part should be busy with rehearsals, so that when the night of entertainment arrives, and the house is packed to overflowing, no one will be covered with shame and confusion of face.

Among many wonderful tales worthy of particular mention is "Little Ida's Flowers," because it is capable of charming representation and necessitates many characters. It may be given at any time of the year.

| Little Ida, a short girl. |

| Student, a tall boy. |

| First Fairy. |

| Second Fairy. |

| Privy Councillor, a boy representing a middle-aged man. |

| The Reader, a girl. |

| Yellow Lily, a girl. |

| Blue Crocus, a boy. |

| Flowers, girls and boys. |

| Butterflies, girls and boys. |

Scene First.—A library, showing a table, lamp, easy-chairs, sofa, one very high chair representing a throne. Ida, costumed as a little girl, walks toward the Student, who is seated on the sofa, and holds towards him a bunch of flowers.

Ida. "My poor flowers are quite dead. They were so pretty yesterday, and now all the leaves are withered. Why do the flowers look so faded to-day?"

Student. "Do you know what's the matter? The flowers have been at a ball last night, and that's why they hang their heads."

Ida. "But flowers cannot dance!"

Student. "Oh yes! When it grows dark and we are asleep they jump about merrily. Almost every night they have a ball."

Ida. "Can children go to this ball?"

Student. "Yes, quite little daisies and lilies-of-the-valley."

Ida. "Where do the beautiful flowers dance?"

Student. "Have you not often been outside of the town gate, by the great castle where the King lives in summer, and where the beautiful garden is with all the flowers? You have seen the swans which swim up to you when you want to give them bread crumbs. There are capital balls there, believe me!"

Ida. "I was out there in the garden yesterday with my[Pg 245] mother, but all the leaves were off the trees, and there was not one flower left. Where are they?"

Student. "They are within the castle. As soon as the King and all the court go to town, the flowers run out of the garden into the castle and are merry. You should see that. The two most beautiful roses seat themselves on the throne, and then they are King and Queen; all the red coxcombs arrange themselves on either side, and stand and bow; they are the chamberlains. Then all the pretty flowers come, and there is a great ball. The blue violets represent little naval cadets; they dance with hyacinths and crocuses, which they call young ladies; the tulips and the great tiger-lilies are old ladies who keep watch that the dancing is well done and everything goes on with propriety."

No sooner is this last word uttered than a sound of music is heard. Enter two Fairies, who stand one on either side of little Ida, and waving their wands over her, sing:

"Oh, listen, listen! your eyes shall glisten

With pleasure and love and jubilee."

First Fairy. "She looks surprised."

Second Fairy. "She has dropped her flowers."

First Fairy. "She would better sit down."

Second Fairy. "Follow me."

Whereupon Ida follows the Second Fairy's lead, who waves her to a seat by the Student's side, and immediately the fairies walk to the opposite end of the room. As they walk gay music is heard louder and yet louder, and in run the Flowers, as the Student has described, the two most beautiful roses seating themselves on the tall chair which represents the throne.

This scene will allow for a large number of girls and boys, and each should be costumed so that no one can make mistake as to what flower they are exhibiting. When all are in the room dancing begins, and continues for half an hour; as the Flowers retire they make obeisance to the King and Queen. And all having now gone but the Fairies, the King asks the First Fairy to dance with him, and the Queen the Second Fairy to dance with her, and after a short dance they also retire, and Ida and the Student are again alone.

Ida. "But is nobody there who hurts the flowers for dancing in the King's castle?"

Student. "There is nobody who really knows about it."

Ida. "Can the flowers out of the botanical garden get there? Can they go a long distance?"

Student. "Yes, certainly. If they like they can fly. Have you not seen the beautiful butterflies—red, yellow, and white? They almost look like flowers, and that is what they have been."

Once again gay music is heard, and in come the fairies dancing, followed by a train of dancing butterflies, costumed in red, yellow, and white. After dancing for ten minutes the butterflies retire, and the fairies wave their wands to Ida and the Student, and sing,

"We be fairies of the wood,

And spend our time, on doing good."

Then they immediately touch their wands to the floor, and the First Fairy draws a ring at the feet of Ida, and the Second Fairy at the feet of the Student, and then they retire.

Ida. "How can one flower talk to another? For you know flowers cannot speak."

Student. "That they cannot, certainly; but then they can make signs. Have you not noticed that when the wind blows a little the flowers nod at one another, and move all their green leaves? They can understand that just as well as we when we speak together."

Ida. "That is funny." And she laughs.

Enter the Privy Councillor, who has come to pay a visit, and sits down on the sofa by the Student's side.

Privy Councillor. "How can any one put such notions into a child's head? They are stupid fancies!"