NARRATIVE.

Drawn by C. H. Greenhill. Engraved by W. Lee.

OF A RECENT

IMPRISONMENT IN CHINA

AFTER THE

WRECK OF THE KITE.

BY JOHN LEE SCOTT.

Second Edition.

LONDON:

W. H. DALTON, COCKSPUR STREET

1842.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY G. J. PALMER, SAVOY STREET, STRAND.

TO THE

RIGHT HON. SIR JOHN PIRIE, BART.,

LORD MAYOR OF LONDON,

THIS NARRATIVE

IS,

WITH HIS LORDSHIP'S PERMISSION,

RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED

BY

HIS OBEDIENT HUMBLE SERVANT,

JOHN LEE SCOTT.

TO THE FIRST EDITION.

My only apology for launching this unvarnished narrative upon the world is, that, after my return to England, I wrote for the amusement, and at the request of my friends, a short account of my shipwreck and subsequent imprisonment in the Celestial Empire; and considering that my sufferings and adventures would, at this time, create an interest with the public at large, they have strongly urged me to publish this narrative. This I have ventured to do, hoping that the faults may be overlooked, and all indulgence shown to a young merchant sailor.

London, Nov. 16, 1841.

| CHAPTER I. |

| Leave Shields—Madras—Hired by government—Arrive at Chusan—Junks—Sickness—Number of Crew—Yeang-tze-keang—Boat breaks adrift—Wreck—Mr. Noble and child drowned—Mrs. Noble—Lieut. Douglas—Vessel rights—Jolly-boat returns—Chinese—Leave the wreck. |

| Page 1-16 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| Get ashore—Village—Appearance of country—Made prisoners—Syrang—Bound—Chinese gentleman—Old women—Meet some of the crew—Kindness of one Chinese—Put into irons—Insults—Interrogated by mandarin—Death of marines |

| 17-32 |

| [Pg x] |

| CHAPTER III. |

| Temple—Cages—Women—Dinner—Hot water—Taken down a river—City—Guns—Hall of Ancestors—Twizell and the missing party—English prisoner—Corporal of marines—Jail—Other Lascars—Watch |

| 33-49 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| Captain Anstruther—Kindness to marines—Mandarin's questions—Chinese music—Jolly-boat party arrive—Privations—Medical treatment—Removed—Sedans—Town—Joshouse—Apartment—Guard-room |

| 50-66 |

| CHAPTER V. |

| Physician—Visitors—Day's employment—Taken before the mandarin—Letters and clothing from Chusan—Chinese clothes—Irons taken off—Return home—Salamanders—Amusements |

| 67-81 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| Language—Marine dies—Canton interpreter—Lieut. Douglas—Secret letters—Soap—Money—Christmas—Court-martial—Fires—Chinese dinner—Ladies' apartments |

| 82-98 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| Jos ceremonies—Chinese New Year's day—New Testament—Epsom salts—Grief of our jailer—Kites—Procession—Leave Ningpo—Chinhae—Huge idols—Chinese camp—Mandarin's message |

| 99-109 |

| [Pg xi] |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| Sampan—Description of junk—Preserved eggs—Reception from the English—H. M. S. Blonde—Mrs. Noble—Leave Chusan—Narrow escape—H. M. S. Samarang—Leave Macao—Arrive at Spithead |

| 110-126 |

NARRATIVE.

Leave Shields—Madras—Hired by government—Arrive at Chusan—Junks—Sickness—Number of Crew—Yeang-tze-keang—Boat breaks adrift—Wreck—Mr. Noble and child drowned—Mrs. Noble—Lieut. Douglas—Vessel rights—Jolly-boat returns—Chinese—Leave the wreck.

On Monday the 8th July, 1839, I left Shields for Bordeaux in the Kite, a beautiful brig of 281 tons, commanded by Mr. James Noble; built by, and belonging to, Messrs. T. and W. Smith of Newcastle. We arrived at Bordeaux after a three weeks passage, and lay there for two months. Sailed from thence on the 16th October for the Mauritius, with a cargo of wines, and arrived there after a[Pg 2] passage of ninety-three days. Here we remained a month, and having landed the wines, sailed from thence to Madras in ballast; where the vessel was taken up by government, to carry stores to the British fleet destined for China: we then sailed for Trincomalee, at which place we took in some more stores, and then sailed for Singapore; where, on our arrival, we found the fleet had sailed several days before for Macao.

Whilst we lay at Singapore, the Melville 72, Blonde 42, and Pylades 18, arrived, and we received orders to sail for Macao immediately, at which place we arrived after a short passage, but were still behind the fleet, it having sailed some days before for Chusan. We received orders to follow it to Buffalo Island, where there was to be a man of war cruising to give us farther directions; but when we arrived at this island we found no vessel of any kind; and as we had had a very quick passage, Mr. Noble was afraid to proceed any further, as perhaps we might have passed the fleet, and arrived before it. We[Pg 3] therefore brought the ship to an anchor, and lay there till the next afternoon, when the Melville and a transport arrived, upon which we got under weigh, and followed the Melville up to Chusan, where we arrived the day following, and anchored in the outer roads. We found the town in the possession of our own troops, who had taken it the day previous to our arrival: so that if we had not stopped at Buffalo Island, we should have been present at the attack; we heard the firing, and saw the blaze of the burning town whilst on our passage up.

The men-of-war junks which had fired on the Wellesley presented a most wretched appearance, being deserted—some sunk, and others with their masts shot away; and where a shot had struck the hull, it had not only passed completely through the vessel, but also through one or two houses ashore. There were not many Chinese to be seen, and the few that were still in the town, appeared of the very lowest grade. The town and harbour presented, nevertheless, rather a lively[Pg 4] spectacle, as boats were constantly passing between the ships and the shore, disembarking troops of varied dress and nations. Two camps were very soon formed, one overlooking the town, and the other on a hill commanding the entrance into the harbour. Sickness soon began to make its appearance amongst the troops, particularly the Company's native regiments, brought on, I think, by inactivity, and by the dreadful smells of the town, as well as the effluvia arising from the imperfectly buried dead of the Chinese; whilst those who were on board ship, constantly at work, and yet drinking the same bad water, were not affected in nearly so serious a manner.

We lay at Chusan for about a month; during which time Admiral Elliot and Commodore Bremer were several times on board of the Kite; and approving of her, all the stores were taken out, and four 32 pounders were put in the hold, as many Chinese guns as we could obtain, seven two-tun tanks, and between 30 and 40 water-casks, [Pg 5]all for ballast. After this we received six 12 pound carronades, seven marines, five first-class boys, from the Melville; and Lieut. Douglas, R. N. came and took the command. Our crew at this time consisted of the master, Mr. Noble; the mate, Mr. Witts; and us four apprentices, viz.—Henry Twizell (acting as second mate), Pellew Webb, Wm. Wombwell, and myself; one Englishman; an Italian; and a Manilla man; ten Lascars; and our cook, who was a native of Calcutta, but not a Lascar; Lieut. Douglas, with the seven marines, and five boys, from the Melville, making in all thirty-three. Mrs. Noble and her child, a boy of about five months old, were also on board.

A short time after Lieut. Douglas hoisted his pennant, we sailed with despatches for the Conway 28, which with the Algerine 10 gun brig, and a small schooner called the Hebe, was surveying the Yeang-tze-keang river, and the adjacent sea. In sailing up this river, we found the charts very incorrect, and at last got on a bank, where we[Pg 6] remained for several days until the Conway and the other vessels arrived. We had passed these vessels whilst they were lying at anchor, in one of the numerous creeks at the entrance of the river. The schooner drawing the least water came and assisted us off; and as the Kite drew ten feet water, she was of little use in surveying; we were therefore sent back on Saturday, the 12th of September, 1840, with despatches for Chusan. One marine and a boy died of dysentery whilst we were on the bank.

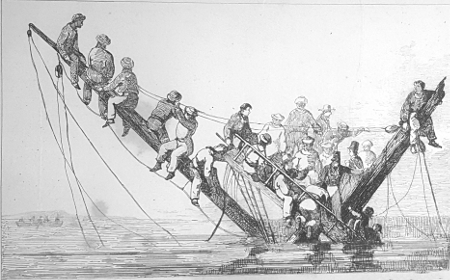

We brought up that night, and got under weigh next afternoon; anchored again at dusk, and very unfortunately, just before daybreak, our jolly-boat broke adrift, and was carried away by the tide. The gig was manned, and sent after her, and we followed in the vessel, as soon as we could get our anchor: we picked up both boats, but not without a great deal of trouble; the gig we hoisted up on the starboard quarter, and the jolly-boat was towed astern. We anchored[Pg 7] again at night, and next morning started with a fine fair wind, expecting to be at Chusan in a day or two. At this time all the marines but one, two of the first-class boys, and Webb and Wombwell, were ill of the dysentery, leaving very few hands to work the ship.

At nine o'clock on Tuesday morning, the 15th of September, I was relieved from the wheel, and went below to look after Webb and Wombwell, and to get my breakfast. About half past eleven, whilst attending on the sick, I heard the master order the anchor to be let go. I immediately jumped on deck, ran forward, and let go the stopper; the vessel was now striking heavily aft, all the chain on deck (about sixty fathoms) ran out with so much velocity that the windlass caught fire. The vessel being by the stem, and catching the ground there, the anchor holding her forward, she could not get end on to the tide, and was consequently broadside on, and as it was running like a sluice, she was capsized in a[Pg 8] moment. When the anchor was let go, Twizell and I ran aft, let go the main top-gallant and top-sail haulyards, and were clewing the yards down with the larboard clewlines, when I felt the ship going over. I directly seized hold of the main topmast backstay, and swung myself on to her side, as she was falling: Twizell caught hold of one of the shrouds of the main rigging, and did the same. At this moment I suppose Mr. Noble to have been thrown overboard—I heard him call out to his wife, "Hold on Anne," but did not see him, and the tide must have carried him away, and of course he was drowned.[1]

My first thought now was for the sick people down below, who I feared must all be drowned, as the vessel was completely on her side, and her tops resting on the sand. On looking aft, I saw a person struggling in the water, and apparently entangled amongst the sails and rigging; I got the bight of the mainbrace and threw to him, and with some difficulty hauled[Pg 9] him on board; but he was only saved then to die a lingering death at a later period at Ningpo. On looking round, I was rejoiced to see the sick people (who I had concluded were all drowned) crawling up the fore and main-hatchways, and immediately assisted them to get on the vessel's side; the greater part were nearly naked, having been lying in their hammocks at the moment she capsized, and out of which some were thrown. I now saw Lieutenant Douglas and the mate dragging Mrs. Noble into the jolly-boat, which had dropped alongside; the two Lascar cabin-boys,[2] who were in the boat, were casting her adrift; she was full of water, and likely to capsize every moment. I threw my knife to them to cut the towlines, and they, having [Pg 10]effected this, were swept away, Lieut. Douglas calling to us to cut away the long-boat, which was still on deck. The time between the first going over of the ship, and the drifting away of the jolly-boat, was only three or four minutes, though by this account it may seem to have been much longer.

Drawn by C. H. Greenhill. Engraved by W. Lee.

The gig, being hoisted up on the starboard quarter, was lost to us when the ship fell over, and we could not cut away the long-boat from the manner in which the guns were hanging: we, however, contrived to cut the foremast lashing, and made her painter fast to the main rigging, hoping she would fall off, and that it would hold her. The tide was now rushing down the hatchways: in a short time the boat fell out of the chocks, but the strength of the tide was so great that the line, or painter, snapped, and she was carried away. The weight of water in the sails carried away the maintopmast, (just above the cap,) the foremast, and the bowsprit; the part of the foremast[Pg 11] below the deck afterwards shot right up, and floated away, leaving only the mainmast standing, and from the weight of wreck hanging to it, we expected that to go also.

We had now nothing but death to look forward to, as the tide was rising fast, and would inevitably in a short time sweep us off her side, where we were all collected to the number of twenty-six, and only myself and one or two more free from dysentery. I expected so soon to be swept away, that I threw off my trousers and prepared for a swim, as I could see the land just on the horizon, and at any rate it was better to die endeavouring to save myself, than to be drowned without making any exertion. Most providentially, the brig righted gradually, until the mast lay in an angle of about forty-five degrees, and enabled us to get, some in the maintop, (where we found a little dog belonging to the mate,) and others on the mainyard. As soon as we got aloft, we began cutting the sails away,[Pg 12] as they held an immense quantity of water, and would most likely on that account, cause the loss of the mast; we cut away the mainsail, trysail, and maintopsail, leaving only the masts and yards to hang on the mainmast, as with these we intended to make a raft.

The tide continued rising upon us, until half the top was under water, and hope was almost dead within us, when to our inexpressible joy, we found the tide ceased to flow; no time was however to be lost, as in these places there is very little slack water, so we that could swim, immediately set to work, and collected all the spars and booms, masts and yards, we could, (for the rigging still held the topmast, &c.,) intending, when the tide had ebbed enough, to get on the wreck, which we expected would be almost dry at low water, and make a stout raft. We could see some fishing-boats in the distance; but these, though they must have seen our disastrous situation, appeared to make no attempt to come to our assistance.

From so many being sick, and from the Lascars refusing to assist us, we had very few left to work, and before we had collected many spars, the ebb tide began to run so strong, that we were obliged to leave off, and take to the maintop again; the spars we did get, we secured together, and made fast in such a manner that the tide could not carry them away. We now sat down again on the top, with hearts most thankful that we had still a little hope left. This was about four in the afternoon, and in half an hour or so afterwards, the jolly-boat came in sight;[3] they had cleared her of water, and they let go the grapnel just abreast of us. Mrs. Noble waved her handkerchief, but the tide was so strong that they were driven past, completely out of our sight, without being able to render us the least assistance, or even being near enough to speak to us. This was a most cruel disappointment; but we had still our raft to look forward to, and knowing that Mrs.[Pg 14] Noble and Lieut. Douglas were still alive was some consolation to us; so we cheered one another in the best manner we could, relying upon Him who was able to save us from this apparently certain destruction.

By the time we could begin our work again, it was very dark, but we knew we should soon have a bright moon; so we set to work cheerfully, and had succeeded in collecting and lashing together a good many spars as a raft, when, to our great surprise, we found ourselves surrounded by Chinese boats, two of them large ones, and full of soldiers.

We all saw that resistance, if they attacked us, would be perfectly useless, and thought it would be better to trust to them than to the waves, so as they all seemed more intent upon plunder than upon us, Twizell and I, two or three of the marines, two of the first-class boys, and the greater part of the Lascars, jumped into one boat, and the rest, with Webb and Wombwell, got into another. The Chinese wished us[Pg 15] very much to get out again, but this we would not think of doing, as stopping by the vessel for another tide was quite impossible.

Finding that we were determined not to remain by the wreck, the Chinese gave in, and shoved off. To our great surprise, we had not gone a few yards when our junk was aground. The other boat made sail, and stood away. The men in our junk made signs for us to get out, when we again refused, fearing, if we did, they would leave us there; and not liking the idea of remaining on a sand, which we knew the flood tide would cover. To have stopped by the wreck would have been preferable to this.

We continued sitting in the boat, until one of the Chinese jumped out, and, taking his lantern, made signs to us to follow him; this we consented to do, and taking care not to let our guide get away from us, we went across the sand for about two miles, with the water sometimes above our knees, and[Pg 16] sometimes only a little above our ankles. At last we arrived at another large boat, which was aground and apparently waiting for the tide to float her. Our guide made signs for us to get into this boat, and that we should be taken ashore in her. This we did, and lay down to take a little rest, grateful that we had been enabled to save our lives, at least for the present.

We hoped that by some means or other we might reach Ningpo, where two English ships were cruising, and we knew that, if we could only once reach them, we were perfectly safe; but we had a very vague idea where we were, though we half suspected we were on the island of Ningpo; we afterwards found our suppositions to be correct.

It was now midnight, and when we left the wreck we could walk on her side, it being only six or eight inches below the surface.

[2] These two boys told me, when in prison at Ningpo, that when the brig upset, everything in the cabin fell to the starboard side, where the child was sleeping; that they could not get out at the door, but got out at the skylight, leaving the poor baby to its fate, and got into the boat, which was then on the starboard quarter.

Get ashore—Village—Appearance of country—Made prisoners—Syrang—Bound—Chinese gentleman—Old women—Meet some of the crew—Kindness of one Chinese—Put into irons—Insults—Interrogated by mandarin—Death of marines.

We reached the shore about three in the morning, and the Chinese made signs to us, that if we would follow them, they would give us something to eat; we accordingly walked after them until we arrived at a small village, which consisted of a few miserable mud huts, with but one respectable brick house; but from these few huts a swarm of men, women, and children poured out on our approach. We were taken into an outhouse, one half of which was occupied by an immense[Pg 18] buffalo, and in the other half was a cane bed with musquito curtains; in one corner was a ladder, leading to a loft containing another couch. They now brought us some hot rice, and a kind of preserved vegetable; we contented ourselves with the rice and a basin of tea, the preserve being so exceedingly nasty we could none of us eat it. Whilst in this place, a Chinese, who seemed the superior of the village, and doubtless was the owner of the one brick house, brought a piece of paper written upon in Chinese characters, and made signs for one of us to write upon it; intimating at the same time, that he had written some account of us on this paper, and that he wanted an account in our writing, which I accordingly gave him, stating the time and cause of our shipwreck, and also our present situation; hoping that he would take it to the mandarin of the district, and that from him it might be forwarded to the authorities at Chusan, who might thus learn where we were, and take some steps for our return to the fleet.

When it was broad daylight we mentioned the name of Ningpo, and they made signs that if we would go with them they would show us the way there, so we started, as we imagined, for Ningpo.

Having no trousers, and my only clothing being a flannel shirt, and a black silk handkerchief round my head, which Twizell had given me when in the maintop, they gave me a piece of matting, but this proving rather an encumbrance than of any service, I soon threw it off, and walked on sans culottes.

We passed in this style through a highly cultivated country; on every side large plantations of cotton and rice, and various kinds of vegetables, but all unknown to me. Having gone six or seven miles, seeing very few houses, but crowds of people turning out of each as we passed, we at length arrived at a cross-road. Here another party of Chinese appeared, who absolutely forbade our proceeding any further: but as our guides went on, and beckoned us to follow, we pushed through our opponents and walked on; but[Pg 20] they, having collected more men, headed us, and we were obliged to come to a stand-still. In this case we found the want of a perfect understanding amongst ourselves, for the Lascars were so frightened at their situation, that they fell on their knees before the Chinamen, which of course encouraged the latter, and before we could look around us, men rose up as it were from the ground, separated us, and made us all prisoners at once, with the exception of four, who ran off, though without any idea whither they should run, or what they should do. Here the[4] Syrang made a foolish attempt to cut his throat with a rusty old knife he had about him, but he only succeeded in tearing his flesh a little, for he was soon disarmed and pinioned. If, perhaps, we had all stood together, and put a bold face on the matter, though without any kind of arms, we might have gone quietly to the mandarin's, and then have been treated properly, but the conduct of the Lascars emboldened our enemies, and we were seized, bound, and dragged off,[Pg 21] almost before we knew where we were. As to those who ran away, they were obliged to give themselves up after a short run, and got a very severe beating, besides several wounds from the spears the Chinese were armed with.

From this time my narrative becomes almost personal, as I can seldom give an account of more than what befel myself.

When we were seized in the manner I have related, a man threw his arms round me, and though I could easily have shaken him off, I saw five or six others gathering round me, and I thought it would be useless to struggle. It was better for me that I made no resistance, as the others were bound and dragged away, with ropes round their necks; whereas the man who first seized me, still held me, and walked me off, without binding me at all. Twizell was amongst those that ran, and I did not see him again till I got to Ningpo. As I was walking along with my keeper, we were met by two soldiers, who immediately[Pg 22] stopped, and one, armed with a spear, prepared to make a lunge at me; but my old man stepped between us, and spoke to him, upon which he dropped his spear, and allowed us to pass.

At length we arrived at a large village, and here my first keeper left me, much to my regret, as, after he was gone, my hands, hitherto free, were made fast behind my back, and the cord being drawn as tight as possible, the flesh soon swelled and caused me great pain; another rope was put round my neck, by which they led me about.

At times I gave myself up for lost, but still I could not fancy the Chinese to be so cruel a people, as to murder us in cold blood, particularly after the manner in which we had fallen into their hands. I hardly knew what to think.

My new keeper led me into the courtyard of a house, and made me fast to one of several pillars that supported a rude kind of verandah, dragging the rope as tight as he could however, he brought me some water[Pg 23] to drink, when I made signs for it. I had not been here long, when one of the Melville's people was brought in, and made fast to an opposite pillar; but we could not speak to, and could hardly see each other, as the yard was crowded with people anxious to get a peep at us.

After standing here some time, a man came and took me away to another house, where, in the yard, was a quantity of cotton, and in one corner, looking out of a window, a Chinese gentleman and lady, before whom my guide led me, and prostrated himself, wishing me to do the same; but I contented myself with bowing, upon which the gentleman waved his hand, and I was led to the back-yard, where my guide brought me some rice and vegetables. I did not feel so grateful for my dinner as I perhaps ought, as I imagined this person had bought me for a slave.

When I had finished my repast, I was led back, and, being made fast to a tree, was left exposed to the mercy of the mob, [Pg 24]without a guard. The people amused themselves with making signs; some, that my head would be cut off, others that I should not lose my head, but my eyes, tongue, and nose, and all those little necessaries, and then be sent away—a most unenviable state to be reduced to. I was kept here some time, surrounded by a number of ugly old women, who seemed to take a delight in teasing me; but the most active of my tormentors was neither old nor ugly, being a tall and well-made person; her feet were not so mishapen as the generality of her countrywomen's; in fact, she was the handsomest woman I saw in China. At last a man came, loosed me from the tree, and led me off to a little distance; and while one man brought a stone block, another was sent away, as I imagined, for an axe or some such instrument; before this block I was desired to kneel, but this I refused to do, determined not to give up my life in so quiet a manner as they seemed to propose. The messenger returned shortly, the block[Pg 25] was taken away, and I was led out of the village.

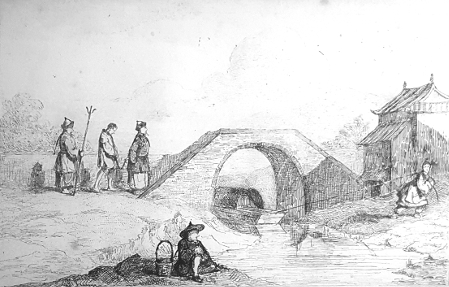

Drawn by C. H. Greenhill. Engraved by W. Lee.

Being now guarded by a dozen armed men, I was led along the banks of a canal until I came to a bridge, where I saw some of my companions in misfortune; I could only exchange a hurried word or two as they dragged me past, as I supposed, to the place of execution. I went on thus, with two more of the prisoners at some distance before me, stopping now and then, and imagining every stoppage to be the last, and that I should here be made an end of; but they still led me on, until we came to another village, or rather town, and I was taken to what appeared to me to be the hall of justice. I was led to the back yard, and placed in a room half filled with a heap of wood ashes. Here I found three more of the crew, in the same miserable condition as myself; but still, even here, we found some to feel for and relieve us a little, for, on making signs that my hands were bound too tight, one of the Chinese loosened the[Pg 26] bonds, and afterwards went out: returning shortly with a lapful of cakes, he distributed them amongst us, and then procured us some water, of which we stood in great need, as we had had a long march under a broiling sun.

We had scarcely finished our cakes, when some of the soldiers came in, and took one of my fellow prisoners just outside the door; as I could observe almost all that passed, it was with feelings of the most unpleasant nature that I saw him made to kneel, and directly surrounded by the soldiers; one of whom came in, and took away a basket full of the ashes. I now supposed that we had in reality come to the last gasp; I fancied my companion's head was off, and that the ashes were taken to serve in the place of sawdust, to soak up his blood. I was not long kept in suspense, for the door opened, and some soldiers entered, who forced me to get up, and go out into the yard. I now took it for granted that my hour was really come; but, to my great relief, they had only[Pg 27] brought me out to fetter me. They put irons on my hands and feet, those on my ankles being connected by a chain of five or six links, and an iron collar round my neck, with a stick fast to it, which was also made fast by a padlock to my handcuffs. I hardly knew whether to rejoice or not at this prolongation of my life, as I might be kept in this condition a short time, only to suffer a more lingering death in the end. When my irons were on, and rivetted, I was led into the outer yard, now crowded with people, and again tied up to a post. On looking around me, I saw my companion, who had been led out before me, fastened in a similar manner to the post opposite; and in a short time they brought the other two, and made them fast to the corresponding corner pillars. We remained a short time exposed to the insults of the lower orders, who amused themselves with pulling our hair, striking us with their pipes, spitting in our faces, and annoying us in all the petty ways they could think of. At last[Pg 28] our guards came, and led us to a small room by the side of the gate, where we again had some rice.

Here I saw a Chinaman prisoner, ironed in exactly the same way as we were.

When we had finished our rice, we were led through the town, down to the side of a canal, where boats were waiting for us. Into one of these they put me and a Lascar, the other two prisoners in another boat, each boat having a guard of several soldiers. We were towed, by one man, so quickly down the canal, that I had little time to notice the country, even had I been in a state of mind to pay much attention. I could see, however, that other canals branched from ours in every direction, and on the banks were an immense number of wheels and machines of various descriptions, for raising the water from the canals, and irrigating the rice-fields; some worked by men as at a tread-mill, and others by buffaloes, which walked round and round in a circle, as we occasionally see horses in our[Pg 29] mills. By dusk, we arrived at a large town, where we had to change our boat; rather an awkward piece of business, as the guard would render us but little assistance, and, fettered as I was, I found it very difficult to crawl from one boat to the other. At last I managed it, and then lay down in the bottom of my new conveyance, the soldier taking the precaution of making my neck-rope fast, so that I could not escape.

About ten in the evening we arrived at another town, but, being late, everything here was perfectly quiet. I was now landed, and led through the town to the mandarin's house; on the way there, I tripped and fell, breaking the rivet of my fetters, and cutting my knee at the same time. The soldier who was leading me by the rope round my neck, said nothing, but waited very quietly till I had picked myself up again, and we proceeded on, till we came to the head mandarin's house.

Here, to my great joy, I found the greater part of those who had come ashore[Pg 30] in the junk with me; but still those who had got into the other boat, on leaving the wreck, and those who had run away, were missing; and we could hardly hope ever to see them again. I sat down on one of the steps, an officer brought me some cakes, and on seeing my knee, which had rather a deep cut, brought a small bottle, from which he sprinkled some kind of powder on the wound: this immediately stopped the bleeding, and in a day or two the part was healed.

I sat here a short time, without being allowed to speak to the others; till suddenly we were made to stand up and place ourselves in two rows, and the mandarin and two of his officers made their appearance. They walked down the rows, stopping at each person, and by signs asked if we had had guns or opium on board our vessel. We only shook our heads in answer to their questions, and as we were not able to understand the other signs, they very soon retired.

When they were gone, the soldiers led us across one or two yards, into a joshouse. By the light from the torches, I could distinguish, in a place railed off from the rest of the building, some people lying apparently asleep. At first I imagined them to be Chinese; but to my amazement and great joy, I soon discovered this party to consist of Webb and Wombwell, and those who had left the wreck in the other junk, and of whose fate we had hitherto been in ignorance. In consequence of some misunderstanding, they had been most severely beaten by the Chinese, and from the effects of this beating, two of the marines had died, on their way from the coast to this town. Though dead when they arrived, the Chinese had, nevertheless, put irons on the bodies. The corporal of marines had been so ill treated, that he could not move without assistance; and in fact they had all experienced worse treatment than our party.

There were now missing, only the four who had run off when the Chinese stopped[Pg 32] us at the cross-way. Of Mrs. Noble, and those in the jolly-boat, we, of course, knew nothing; but hoped that they might have escaped the Chinese, and managed to reach Chusan.

Haying related our different stories, and consoled each other in the best way we could, we lay down on some loose straw for the night, and, notwithstanding our miserable condition, we slept soundly.

Temple—Cages—Women—Dinner—Hot water—Taken down a river—City—Guns—Hall of Ancestors—Twizell and the missing party—English prisoner—Corporal of marines—Jail—Other Lascars—Watch.

In the morning, when I awoke, I found I was in a temple; outside the railing was a large hall; on each side, rows of seats were ranged, with a broad space in the centre; the sides of the building were quite plain, and so also was the roof. Inside the railing was a green silk canopy, under which were several images, handsomely dressed in different coloured silks. Standing against the walls were four more figures the size of life, one painted entirely black, another red, and the other two variegated; and all armed with some extraordinary instruments[Pg 34] of warfare. These I suppose represented their gods, and were tolerably well done, but not to be compared to others I afterwards saw. The whole building was so destitute of any ornaments, that, had it not been for the images, the idea of it being a jos-house would not have struck me.

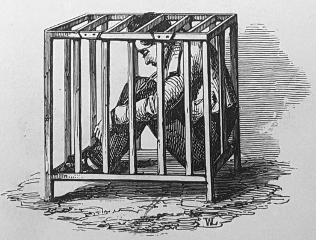

Breakfast was brought in early, consisting of sweet cakes and tea. When we had finished, two wooden cages were brought; the Chinese lifted one of our men into each, and carried them outside the gate, to be looked at by the common people; whilst the gentlemen, and better class, with their families, were admitted about two dozen at a time, to look at us who remained inside: sometimes we were visited by a party consisting entirely of women; they were a remarkably plain set, their pretensions to beauty, in their own eyes, appearing to lie in having the face painted red and white, and the feet distorted into a hoof-like shape. After keeping those in the cages, outside for about two hours, they were brought in, and[Pg 35] two fresh ones were taken out. Those who came in, told us that the bodies of our two poor fellows, who had been killed the day before, were lying outside on the grass, with the fetters still on. Fortunately it soon began to rain heavily, when the other two were brought in, and the crowd gradually dispersed.

About noon we had our dinner; one basin full of rice and vegetables, and cakes and tea, as before; our jailers would never give us plain water, but whenever we asked for anything to drink, brought us weak tea. For supper we had cakes and tea again, and, after this last meal, lay down on our straw for the night.

The next day was passed in a similar manner; towards evening there was a great mustering of cages in the hall; little did I think for what purpose they were intended. After the Chinese had ranged these horrible things in the open space in the centre, they made us all get into them, one into each. I forgot to say that before we were put into our cages, our jailers gave us each[Pg 36] a loose jacket and a pair of trousers, besides as many cakes as we could carry. In these wooden contrivances—which were not much unlike what I imagine Cardinal Balue's machines to have been, only ours were wooden and portable—we had neither room to stand, sit, nor lie, so that we were obliged to place ourselves in a dreadfully cramped position. Some few of the cages had a hole cut in the lid, large enough to allow the top of the head to pass out: into one of these I was fortunate enough to get; but those who were not so lucky, had the misery of sitting with their heads on one side, to add to their other discomforts. Afterwards I was put into one without a hole, and miserable was my position.

When we were all stowed in our separate cages, we were carried down to the side of the canal, and placed in boats, two cages in each boat, attended by a mandarin officer and several soldiers. My companion was a marine, one who had come ashore in the junk with Webb and Wombwell, and was[Pg 37] still suffering from the effects of his beating, besides being almost dead with dysentery. We lay alongside the quay till nearly midnight, the soldiers and other people constantly running backwards and forwards on shore, with torches and gongs, shouting and making a great noise. About midnight we shoved off, and started down the canal; but as the junk was covered over, and it was very dark, I could see nothing of the country.

We soon appeared to be in a wider stream, as they made sail on the boat, and we went along at a rapid rate. In the morning I found that we had got out of the canal, and were in a river, going down with wind and tide. At any other time I should have enjoyed myself very much, but at present my future prospects were too far from agreeable, to allow of anything approaching to enjoyment.

The banks of the river appeared to be well cultivated; here and there some military stations might be seen, distinguished from the other houses by their flag-staffs. Many[Pg 38] junks were moored alongside the bank, some very large, one in particular, whose long streamers flew gaily out in the breeze.

We stopped at a town on the left bank, where the soldiers got some firewood, and immediately set to work to prepare breakfast; rice, and some compounds of I know not what, for themselves, and sweet cakes and tea for me and my companion; but he was too ill to eat, and was constantly craving for water, which was never denied him. On our arrival at this town, the people crowded into our boat, nearly capsizing her; and to my surprise our guards made no attempt to keep them out, but on the contrary rather encouraged them. They had not long to satisfy their curiosity, for as soon as the soldiers had procured all they wanted, the boat was shoved off, and they hoisted the sail again. We continued our way down the stream till we arrived at another large town on the left bank. Here we stopped again, and I could soon see we were to be disembarked. The people[Pg 39] crowded to see us as usual, but one of the soldiers, throwing part of the sail over the tops of our cages, kept watch over us, and would allow no one to molest us.

On the sail being removed, that we might be taken out of the boat, the first thing that met my eye was one of our guns, with the carriage belonging to it; soon after I saw another gun and its carriage. To enable the Chinese to get these guns, the tide must have fallen considerably after we left the wreck. The sight of these guns, as may be imagined, caused me anything but pleasurable sensations, as they proved beyond a doubt to our captors, that we had come to their coast with warlike intentions; and though they would perhaps be ashamed to kill a few shipwrecked merchant sailors, they might not hesitate to do so, if they could be certain that we had been concerned in the recent warfare, and these guns were strong evidence against us.

On being taken out of the boat, a long bamboo was passed between the bars of my cage,[Pg 40] and two men, placing the ends on their shoulders, lifted it off the ground; and in this manner I was carried through an immense crowd, the bearers sometimes stopping to rest, and placing my cage on the ground, upon which the people gathered round and began to torment me, as they had done in former cases. At length, after passing through a great many streets, some of them very gay, we arrived at an open space, at the end of which were large folding gates; through these I passed, and after going up one or two passages, I found myself in a large hall. It was a large plain room, with a balustrade running down each side, behind which were several rough horses, saddled and bridled. At the end opposite the door was a large red silk canopy, under which was a small table, covered with a green cloth, and on it several metal plates and vases, dedicated to the manes of the ancestors of the person to whom the house belonged.[5] Many of the prisoners in their cages had[Pg 41] arrived before me, and the rest followed in due time. The Chinese ranged us in our cages in two lines, one on each side of the hall; and at the end of each line they placed one of the guns, with its muzzle towards us. When we were thus arranged, like beasts in a show, many well and richly-dressed people came to look at us; and none but the better sort seemed to be admitted, for, with the exception of the soldiers, there were no ragged people in the place. Our visitors were mostly dressed in fine light silks, beautifully worked with flowers and figures of different descriptions. All of them had fans, some of them prettily painted, and others plain. One or two of the men had enamelled watches, which they wore hanging to their girdles by a gold chain. We were treated pretty well by them, as they gave us fruit and cakes, and sent water to those who asked for it.

We did not remain long in this hall, for our bearers again made their appearance, and mine, shouldering the cage, marched off,[Pg 42] and I was once more exposed to the mercies of the mob; the soldiers, our guard, never making the slightest attempt to keep the people off. Fortunately for me I had had my hair cut close only a few days before we were wrecked, so that there was little or nothing to lay hold of; for the people on one side would pull my hair to make me look their way, and those on the other side would instantly pull again, to make me look round at them; and I, being ironed, hands, feet, and neck, could not offer the least resistance, but was obliged to sit very patiently, or, in other words, to grin and bear it.

Heartily glad was I, when again taken up and walked off with. After passing through many streets, I arrived at a mandarin's house, and was placed with the other prisoners in a small court. Some empty cages were standing about, larger than the one I was in, and with small yellow flags flying on their tops.

In a short time some officers came in, and opening the lid of my cage, lifted me out,[Pg 43] and led me out of this court into a larger one. To my great delight I here saw Twizell, and the three of the crew that had been missing, sitting in one corner, under a tree. I could not stop and speak to them, my guides hurrying me on. We scarcely recognized one another, so much were we altered.

I walked on for a short time, meditating on the past events, and wondering what my fate would be, when, raising my eyes from the ground, to my astonishment I perceived a man walking before me, heavily ironed, and whom I had never seen before. He was evidently an Englishman, and seemed almost in a worse condition than myself. When he heard me clanking after him, he turned round and spoke a few words, expressing his sorrow at seeing any one else in such a situation. I asked him who he was, and how he came there; but before he had time to answer, he was led down one passage, and I along another; so I could neither learn who he was, nor where or how he had been taken.

On emerging from the passage, I found myself in a small paved court, and in the presence of several mandarins. In the centre of this court an old Chinaman was kneeling, fettered as I was; there was no guard over him, and nobody seemed to take the least notice of him, at least not whilst I was there.

To my surprise, one of the mandarins addressed me in English; there was also an interpreter present, a native of Macao, and a prisoner like myself, having his legs in irons.[6] After they had asked me several questions concerning the Kite, where we had been, whither we were going, and how we were lost, I was sent away, and the other prisoners were brought up and interrogated in the same manner. They asked all of us our names and ages, wrote our names on a strip of cotton, and sewed it to the backs of our jackets. We were then all sent away: the Chinese had brought all the cages from the outer to the inner yard, round which they had ranged them.

I now had an opportunity of speaking to Twizell and the others who had run away, and was sorry to hear that two of them (marines) had received several spear wounds, and that all four had been severely bambooed when taken. They had travelled by land all the way from the coast, in the cages, having been put into them the day after we were all captured, and had been two days sooner in their cages than our party.

The corporal of marines, who was seriously ill of the dysentery, was lying on his back in the bottom of his cage, whilst his legs were raised up in the air, and his heels resting on the upper ledge, the lid being thrown back. He had entirely lost his senses, and was evidently dying fast; the maggots were crawling about him, and the smell that came from him was dreadful. Fettered as we were, we could afford him no assistance, and the Chinese merely looked at him, and then walked off, holding their noses.

The strange Englishman at this moment came by, and seeing his horrible situation, spoke to the interpreter who was with him, and he to the Chinese; upon which two of them, though with great reluctance, lifted the marine into a clean cage, and placed him in an easier posture. The stranger now told us that he was an artillery officer, and had been taken some days before at Chusan; but he was hurried away before we could learn his name, or anything more from him.

It was now late in the afternoon, and dusk coming on, we were again put into our cages, and carried through the town, till we arrived at the jail. We were taken across a yard into a long room, which was divided into four parts, by gratings run across. In this miserable place we found eight more prisoners, (Lascars,) some of whom had been for two months in the same sort of cages that we were in.[7] We were placed in the small divisions, the coops being ranged round three sides of[Pg 47] each compartment, the fourth side being the entrance. A chain was passed through each cage, and between our legs, over the chain of our irons; the two ends being padlocked together, we were thus all fastened one to another, and also to our cages. In this most uncomfortable manner we passed the night.

During the night the corporal I have mentioned died. He never recovered the use of his senses.

In the morning the jailer came in, an old man, with a loud voice, cross look, and a piece of thyme, or some other herb, always stuck on his upper lip. He opened the lids of the cages of the eight Lascars, and took the irons off their wrists, thus enabling them to stand upright, and shake themselves; we had no such indulgence, but were kept fast. At eight o'clock our breakfast was brought in; it was jail allowance, two small basins full of rice, and one of vegetables: the cages were opened, and the irons taken off our hands, whilst we ate our scanty[Pg 48] meal, which we had no sooner finished than we were fastened down again. We remained in this state all day, and after our evening allowance, were again secured for the night.

A little before dark, the watch was set, and a large gong, at a short distance, was struck once; upon which a number of smaller gongs struck up, and when they had finished, a boy outside the room began to strike a piece of bamboo with a stick, which noise was continued without intermission the whole night. This horrid noise most effectually prevented my sleeping. The large gong was only struck when the time changed, striking first one, then two, and so on, till it struck five; thus regulating the watches of the night, which, in China, I imagine, is divided into five; at any rate I always found it so.

The following morning the jailer unlocked the lids of our cages, and took the irons off our hands; so that we were at liberty to stand upright, and stretch our limbs; which,[Pg 49] from our cramped position, much needed this relaxation. The large place we were in, was, as I have said before, divided into four smaller apartments, three of which were occupied by us in our cages; whilst in the fourth were some Chinese prisoners, who lived in it by day, but slept in another part of the jail. Outside was a covered passage, in which were several stoves; and here the greater part of the Chinese prisoners cooked their rice and other victuals. They had all chains on their legs, but were otherwise free; and they gave us to understand that they were imprisoned for smuggling opium, or for using it. Some were of the better class, being well dressed, and eating their meals with the mandarin of the place.

Two of the commoner sort had lost their tails,[8] and one was minus his nose, which gave anything but a prepossessing appearance to his countenance.

Captain Anstruther—Kindness to marines—Mandarin's questions—Chinese music—Jolly-boat party arrive—Privations—Medical treatment—Removed—Sedans—Town—Joshouse—Apartment—Guard-room.

Towards the middle of the day, there was a commotion in the yard, and soon afterwards, the jailers and some other people came in, and I and two more, a marine and a boy, were carried out; after waiting a short time in the yard, our cages were again shouldered, and we were conveyed through the town to the residence of a mandarin, but not the same house we had been at two days before. We were taken into the entrance-hall, which had the[Pg 51] usual canopy at the farther end; being, I suppose, the "Hall of Ancestors." I was released from my cage directly it was set down, and found myself with the English prisoner I had previously seen. He told me he was Captain Anstruther, and had been kidnapped at Chusan; that our heads were in comparative security, but that perhaps we should have a long imprisonment, as the Chinese would only consent to give us up, if the English would evacuate Chusan; but to this condition we could not hope the commander-in-chief would accede. However, he was, at the desire of the mandarins, going to write to Chusan to this effect, and by this means our countrymen would know where we were, and perhaps be enabled to procure our release. Whilst I was walking with him, I saw one of the marines, who had been brought to the mandarins with me, lying behind a sedan on a grass-plot, and knowing that he had the dysentery, I feared the poor fellow was dead; but Captain Anstruther said he had[Pg 52] desired him to be placed there, that he might have the benefit of the sun; he had given him some cakes, and afterwards procured him a pair of trowsers; he also caused a doctor to be sent for him; in fact, he did everything that lay in his power to ameliorate our condition.

In a short time I was summoned before the mandarin, and found the same party assembled as before, with the interpreter in waiting. I expected to be questioned concerning the strength of the fleet and army at Chusan; but, on the contrary, the mandarins contented themselves with asking me the most frivolous questions about myself, whether I was married, how old I was, if I had a father or mother, and such like inquiries. When this examination was over, Captain Anstruther was brought in, and as he was a "great captain," was allowed to sit on the floor of the room, whilst we sat outside on the stones. A plate of cakes and a cup of tea were also handed to him. The mandarins could not be made[Pg 53] to understand how Captain Anstruther and our party, both having come from Chusan, should not know each other; nor indeed would they believe me, when I said I had never seen him until the day before. They questioned and cross-questioned me, but to no purpose, as I had never seen or even heard of such a person till then. They could not comprehend the meaning of marines, till Captain Anstruther explained it by calling them "sea soldiers," by which name the marines ever afterwards went.

They made many inquiries about Captain Noble, his wife and child, and showed that they knew much concerning our vessel, from the numerous spies they had at Chusan. After a few more such questions, I was dismissed; and, being lifted into my cage, was carried back to the jail, where I had my supper, and was then locked up for the night. At dark the usual serenade commenced, which noise, with my uncomfortable position, drove all expectation of sleep, at least by night, out of my head.

Soon after we had finished our breakfast the next morning, some of the Chinese prisoners began to play on musical instruments, in different parts of the yard, and independent of each other. One of these instruments was something like a mandoline, and played in the same way; but it was a most monotonous affair, with trifling variety in the notes; and the song was as bad, a kind of sing-song noise, with very little pretensions to the name of music. Another was a kind of small violin, played with a bow; the player could only produce a wretched noise. One man had a small fife; he was not a whit superior to his fellows, though they seemed lost in rapture at their own performance, and remained strumming and blowing all day long, barely allowing themselves time for their meals.

The next morning, Wednesday, two more of our party were taken to the mandarins, and on their return reported the arrival of Mrs. Noble, Lieut. Douglas, Mr. Witts our chief mate, and the two Lascar boys, who[Pg 55] had escaped in the jolly-boat. They told us that Mrs. Noble was in the same kind of cage that we were in. I could scarcely believe them, till the two Lascar boys were brought in, and they confirmed the statement They had not only put her in a cage, but had also put irons on her, treating her in the same manner as they did the male prisoners; and, indeed, in some instances even worse. The mandarins had not the humanity to order her to be taken out of the cage, but let her remain there.

Soon after the boys had come in, Lieut. Douglas and Mr. Witts were brought into the jail, not to our place, but to the rooms on the other side of the yard; and though we could see them, we had no opportunity of speaking. They had been drifting about in the boat for three days, in great misery, not having had any food, except a little dry rice, and some water, out of a junk which they boarded; till at last, being obliged to go on shore, they were made prisoners. I had hoped they might[Pg 56] have reached Chusan, and given an account of the loss of the Kite, and the probability of our being prisoners.

Next day, Saturday, Lieut. Douglas and Mr. Witts, who were kept on the opposite side to us, were taken out of their cages in the daytime, and allowed to walk about the yard; and as they were not prevented coming over to us, they heard our tale, and related theirs in return. Captain Anstruther and Mrs. Noble were kept in separate rooms in another yard; they also were allowed their liberty by day, but when night came, all were locked down in their cages. Through Captain Anstruther's entreaties (who had many opportunities of seeing the mandarins, besides having the advantage of the captured interpreter's company) a doctor came to see some of the prisoners, two of whom had the dysentery very badly, besides several who had spear wounds, and others whose flesh the irons had galled and worked into sores; to the latter he applied plasters, with a pink[Pg 57] powder, which healed them in a short time; but as for those who had the dysentery, he merely felt the pulse, looked at them, and went away, leaving orders that the lids of their cages should always be left open, and the irons taken off their hands.

On Monday morning, Lieut. Douglas came over, and told us we were all going to be removed to a more comfortable place; he and Mr. Witts very soon after were taken away. We had an early supper, and as soon as we had finished, some mandarin officers arrived, one carrying a small board, with some Chinese characters upon it. Their arrival caused a great bustle, and the jailer came in, unlocked the long chain that went through all the cages, and took five of the prisoners away with him. They walked out of the yard, and soon after he returned and took five more, and so on till it came to my turn; I was then lifted out of the cage, and walked out of our yard into a smaller one, where the ring was[Pg 58] taken off my neck, and the irons off my hands, my legs still remaining chained. I was here motioned to sit down on a small form, and on looking round I perceived Mrs. Noble standing at a gate in one corner. I had not seen her since the wreck, so wishing to speak to her, I got up, and was going towards her, but my keepers immediately stopped me, and one, to my surprise, said, "Must not, must not." I turned to him directly, and said, "Do you speak English?" he replied, "Yes, sare;" though on my asking him some other questions, he either would not or could not answer me. On my again attempting to go to Mrs. Noble, he repeated his former expression, and put his hand on my shoulder to prevent my rising. I was obliged, therefore, to content myself with exchanging a few signs with her.

I did not remain long in this place, for I was soon walked out into the open space before the prison, where I found some sedans, into one of which I stepped. They[Pg 59] were open in front, and the ends of the bamboos were fastened together by a crosspiece of the same material, which the bearers, by stopping, placed on their shoulders, and raising the sedan from the ground, trotted off with us at a great rate; several soldiers going before to clear the way.

Some of the streets through which I passed were rather broad, and all were paved with loose flags, not cemented together. The different trades appeared to have their particular streets; the dyers were in one part of the town, the braziers in another, and so on: some of the shops were very well set off, and all quite open to the street. The houses were mostly built of wood, and the names and occupations of the owners were painted up and down the door-posts, in yellow and other bright colours, some being gilded, giving the streets a gay appearance. Here and there was an opening where a joshouse stood; the pillars and other parts of the front gaudily painted and ornamented; and on[Pg 60] the roof were placed several images. I passed several open doors, which led into courtyards belonging to apparently large houses; the courts were thronged with women and children, who all crowded to the entrance as I passed. Neither in this, nor in any other instance did they appear to be deprived of liberty, or to live secluded. The streets had generally a door at each end, in an archway; and this being shut at night, relieves the shopkeepers from the fear of thieves, to whom their open houses would otherwise be very easy of access. The butchers' shops were well fitted up with huge wooden slabs and blocks, and quarters of immensely fat pork hung up for sale; geese, ducks, vegetables, and fish, were all exposed in the broad open streets, as if in a market. I was carried across several bridges, which were built over black, slimy, sewer-looking places, from which, and from the streets themselves, arose even more than the two and seventy several stenches of Cologne.

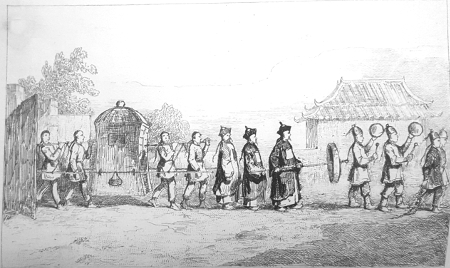

Drawn by C. H. Greenhill. Engraved by W. Lee.

My bearers trotted on through innumerable streets, the soldiers clearing the way before them, not a difficult task, as the curiosity of the inhabitants seemed satisfied, and there was little or no crowd, the people merely coming to their doors and looking at me as I passed. I arrived at length at the end of my journey, the sedan stopped, and I walked out; then turned to my left up a narrow courtyard, and at the end found several mandarins sitting with their officers. I ought to have said before that we knew the mandarins by the balls or buttons on the top of their caps, there being four kinds that I saw—red, blue, white, and crystal; red, I believe, being the highest rank. The officers were distinguished by gilded balls, having one or two tails of fur appending to them, according to their rank. I made a bow on passing, which they all returned; and I was led across a small yard, where I observed large earthen pans for catching water. I walked into a small square room, and again[Pg 62] joined the Englishmen who had preceded me. The floor was covered with mats, and the change from our cages was most agreeable. In a short time some more of the prisoners arrived, and the room was filled with eleven Europeans and four Lascars, making fifteen in all, just as many as the room would hold; nine being on one side, and six on the other, the rest of this side being occupied by a water-bucket, and two small washing-tubs. It being now dark, we began to think of sleep, so we lay down, which there was just room enough to do, each man lying on his back, and the feet of both rows meeting in the centre; so that we had little space to toss about in; however, this was paradise to the cages, and thinking we should not remain here long, we made ourselves as comfortable as circumstances would allow.

The next morning a servant brought us some water to wash ourselves, (the first time we had been allowed this luxury,) fine white[Pg 63] rice boiled in water, and served up in small wooden tubs. We had as much rice as we wished for, and a kind of stew, very much like old rags boiled, in one dish, and salt-fish in another; the dishes were of common earthenware, and shaped like a bowl. There being fifteen of us, we divided ourselves into three messes, five in each, and to each mess was brought a tub full of rice, one dish of stew, and one of very small fish, salted, and served up raw; but I could not make out what they were.

After this meal I began to look about me; the night previous having been too dark for me to notice any of the surrounding objects.

The room I was in, I found, was partitioned off from another, in which was a bed, with two or three chairs, and a small table. In this room lived an old officer, of some rank, I suppose, as all the soldiers, and our jailer, paid him great respect. Two young men came to him every day; whom we used to see, standing up before him, with their hands behind their backs, like schoolboys,[Pg 64] saying their lessons to him. It looked, as ours did, into a small court, in which, also, were some of the same kind of large pans for catching rain water, as those before mentioned. Two sides of the apartment in which I was placed, were of wood, and the other two of white bricks; but they were so thin, and so insecurely placed together, that it would have required little strength to shove them down. The floor was an inch thick in dirt, and the ceiling (which was a great height) covered with cobwebs. It was a place that we might have got out of with very little trouble; but when out, we should not have known which way to turn, if escape had been our object, and our dress and looks would have betrayed us instantly. The consequence of such an attempt might have been fatal; so that they had us as safely confined in this insecure building, as when we were in the cages, fettered and chained to one another.

In front of our room was one appropriated to the use of one of the keepers. An[Pg 65] old man, hasty at times, when rather fou, but who always behaved civilly, and in general very kindly towards us. To the left of his dormitory was a passage that led to the cook-house; and to the right, another that led into a large yard, on each side of which was a spacious apartment, where their jos-ceremonies were performed. Outside our door was a passage, and a staircase that led to the upper story. The passage led down to another large yard, one side of which was walled up, and on the other was a large open room, containing chairs, tables, and sleeping couches, with cane bottoms: this seemed the guard-room, as soldiers were always there, playing with dice and dominoes; and their arms (match-locks, and bows and arrows,) were scattered about. Beyond this room was another passage, which led to the room where the sixteen Lascars were confined; a smaller and far less comfortable place than ours.

What opportunities I had of seeing the building caused me to conclude, that it was[Pg 66] a jos-house, and of spacious dimensions; but I saw no images, nor any religious ceremonies performed.[9]

The day passed on, and supper-time came; this meal was the same as the morning's: after it was over, and the room swept, an officer came in, and distributed rugs amongst us; one rug between two. These were a great improvement upon the mats, being soft to lie upon during the hot weather, and warm to cover us, in case of our remaining there the winter. At dark, the watch was set, the same as down at the jail, only here the noise was not so incessant; and indeed the watchmen very often fell asleep, and left us undisturbed a long time.

Physician—Visitors—Day's employment—Taken before the mandarin—Letters and clothing from Chusan—Chinese clothes—Irons taken off—Return home—Salamanders—Amusements.

The next morning one of the Melville's boys was taken ill of the dysentery; the doctor came to see him, and prescribed some medicine, which came in the shape of a bitter brown mixture; it did him no good, for in a few days he grew so much worse, that he was removed down to the jail again, where, by-the-bye, the two marines who were ill had been left, as they were unable to bear the moving. Poor fellows! they felt very much being separated from their comrades, and left behind; but it was of no use complaining; they were obliged to submit. As[Pg 68] for the boy[10] that was taken from us, (the same that I dragged out of the water when we were wrecked,) he left us, I might almost say, with a determination to die, so entirely did he despair; his forebodings were too true, as he died shortly after in the jail.

The window was besieged all day by well dressed persons, who came to see "the lions;" at first we only looked again, but getting bolder by degrees, we turned beggars, and from every fresh batch that came to the window, we requested something—either money, tobacco, or cakes, not being very particular: if they refused to give anything, we immediately slid the panels to, which most effectually prevented their seeing us, and the soldiers, our guard, very soon turned them out. Our grating was blockaded continually in this manner for more than a week, when the visitors ceased to come, and we were left in quietness.

Being in so crowded a state, and never[Pg 69] allowed to go out of the room, on any pretence whatever, the air soon became very unwholesome; and animals, the natural consequence of such a state of things, began to show themselves, and, in spite of our utmost exertions, increased upon us; so that if the warm weather, which was very favourable to them, should continue, we stood a fair chance of being devoured alive. But our deplorable condition fortunately raised up another nation, which, though living upon the same body, made desperate war upon the other creatures, and by this means they kept each other under. The principal employment in the morning was to overhaul our clothes, and kill all we could catch—a most disgusting way of passing the time, but yet most necessary; the rest of the day was spent either in walking up and down the room, spinning yarns, or sleeping.

After remaining in this place about a fortnight, we were one evening surprised by the appearance of the compradore, who came to ask if we wished to send to Chusan for[Pg 70] anything, as he was going there. As I knew nobody there, and felt sure that Lieut. Douglas, who was as kind and attentive to us as opportunity allowed, would write, and acquaint the proper persons with our situation and wants, I did not write, neither did any of the others; he therefore went away, saying, that in about three weeks he hoped we should all be free; but he added, "Mandarin big rogue;" however, this was far better news than I expected, and I looked forward to his return with pleasure and anxiety.

Time passed on pretty well after this, and things were going on as usual; those who had been ill of dysentery on board the ship were gradually getting better, fear having worked wonders; when about a fortnight after the compradore's visit, we were roused one evening by a noise in the passage, whilst we were at supper. The board which had before attended us, again made its appearance, and as soon as we had finished our repast, all the white men were walked out[Pg 71] of the room, and, after waiting a short time in the yard, sedans having been collected, we were placed in them, and carried to the chief mandarin's house. After passing through numerous streets, we arrived at a green plot railed in; against the railings were placed several small flags, some yellow and some red, but all having Chinese characters upon them. Passing through a gate, we came to a pair of large folding doors, on each fold of which was painted a gaudy figure, bearing a sword, and very much resembling the king of diamonds in our cards, only not half so good looking. On each side of this huge door was another smaller, through one of which we were taken, and here our sedans stopped, and we alighted. At the end of this new yard was a canopy of red and green silk as usual; we sat under this canopy until we were summoned before the mandarins. We were then led through a large place, which appeared intended for an ornamental garden, several rocks being placed here and[Pg 72] there, round which the path wound; but I saw no flowers, and very few green things of any description.

The room in which the mandarins were assembled, was rather a large chamber, open in front, as it was the hot season; several couches, and glazed arm-chairs, were arranged about the room; four large paper lanterns were suspended from the ceiling, and as the evening drew in, they, and many more placed in other parts of the room, were lighted. One or two more mandarins arriving, there was a great deal of bowing, and salaaming, and tea-drinking, after which they proceeded to business.

The compradore now made his appearance, and produced several letters, which he handed to me to read: on opening them, I found that they came from Chusan, with various articles of clothing, and other comforts for Lieut. Douglas and Captain Anstruther, clothes of all sorts for Mrs. Noble, and a quantity for the child which was drowned; but nothing whatever arrived[Pg 73] for the crew; although Lieut. Douglas had written for necessary clothes for us, as well as for himself. I read the letters over to the compradore, making him understand, as well as I could, the nature of the contents, and he repeated them to the mandarins, whose official took them down in Chinese. When we had finished reading the letters, Mrs. Noble, Lieut. Douglas, Capt. Anstruther, and the mate, were brought in, and their letters given to them; they were also permitted to open their stores. We were now allowed to converse together for a short time. Until now, I had not been able to speak to Mrs. Noble since the wreck. The mandarins soon called us up, and told us, by the interpreter, that all was peace, and that in six days we should be sent down to Chusan; but, after giving us this agreeable intelligence, they inquired if we had any clothes for the cold weather, which would soon come on. I immediately said, "If we are going so soon to Chusan, we shall not require any of your clothes." They sent[Pg 74] out, notwithstanding, and soon after a basket was brought in, containing our future raiment, which the mandarins distributed amongst our party. They gave to each man a large loose coat, and a pair of leggings, made of dungaree, and lined with cotton.

They were very warm and well calculated to keep out the cold, but very clumsy and heavy; still they were not to be refused, and indeed had it not been for this kindness of the mandarins, we should have been exposed, almost naked, to the approaching inclement season. But this anxiety to provide us with clothing for the cold weather, made me doubt very much whether six days, or even six weeks, would find us on our way to Chusan. As it turned out, it was exactly sixteen weeks from that day before we were released.

After another consultation amongst the mandarins, we were all called up again, and the irons taken off our legs, beginning with Mrs. Noble. This was a great relief, as our legs were quite stiff with their long confinement, and in most cases the iron had worked[Pg 75] into our flesh. Whilst they were being taken off, the compradore desired us to tell the Lascars, who had been left behind in the prison, that if they made no "bobberee," their irons would be taken off also.[11]

Being once more unfettered, we were again separated from Lieut. Douglas and his party, and led away to another room, the ceiling of which seemed very much inclined to come down on our heads. There was a table here, and a couch. I had no sooner taken my seat on the latter, than a well-dressed Chinese put writing materials before me, red paper, Indian ink, and a small brush. He made signs for me to write, salaaming low at the same time; I immediately complied with his request, and wrote a few lines for him. I had no sooner done this, and returned his brush, than he produced a[Pg 76] handful of pice, and presented them to me; my finances being very low indeed, this donation was not to be rejected; I therefore accepted them, and found he had given me between fifty and sixty pice, (about four pence in our money,)—very good pay, I thought, for writing half a dozen lines.

In this room refreshments were brought for us; hard-boiled eggs, fowls and pork cut into small pieces, and two sorts of cakes, one being plain, with small seeds on the top; the other very like dumplings, with minced pork inside. In fact, there was as much as we could eat, and all was good of the kind; at any rate, we completely demolished the good things, and then we returned to our sedans, and were carried back to our rooms. Here we found the Lascars anxiously awaiting our return; we told them that the mandarins said we were going to Chusan in six days, which good news raised their spirits very much, and they began to abuse the Chinese, especially the female part of the community,[Pg 77] for having imprisoned them at all. The next day our jailer brought us shoes and stockings of Chinese manufacture, and made signs that the Lascars' clothes were being made, and would very soon be ready.

In the course of the same day, my friend of the previous night came and requested me to write something more for him; I of course consented, and he then produced some plain white fans; I wrote a few lines upon them, and he seemed much pleased with my performance; Wombwell also wrote on one for him. In return, he gave us two a basket full of sweet cakes, which were very acceptable; he came to see us several times afterwards, and never failed to bring some token of his gratitude with him.

Time wore away: the six days went by, and we were not released; some said they were perhaps waiting till the Lascars' jackets were ready, but they were brought, and we were still kept prisoners.

With the new clothes came also some of those horrid creatures by which we had[Pg 78] been tormented; these coming fresh from the tailors' hands, made us observe our guards a little more closely, and we could plainly discern that they were swarming with vermin. We were glad to find that what we had at first set down to our own dirt and unwholesomeness, was more attributable to the dirt and laziness of our jailers and other people. Even the walls had their inhabitants, for they fell down out of the rafters upon us.

Days and weeks passed on, and we gave up all hopes of a speedy release, expecting nothing less than an imprisonment of a year or two; but I cannot say that I was now much troubled with the fear of losing my head. During this time we were sometimes amused with a fight in the yard, between two of the soldiers—a most unpleasant kind of combat, for they seized hold of each other's tails with one hand, and dragging the head down almost to the ground, clawed and scratched with the other hand, till the one with the weakest[Pg 79] tail rolled over and gave in; we always tried to get out and see fair play, but the soldiers mustered too strong at these times. Sometimes, again, a drunken soldier would make his appearance, and coming to the window afford us a little amusement, for, getting hold of his tail, we made it fast to the grating, and then left him to get loose as he could; generally one of his comrades, attracted by his bellowing, came and released him; all this was not very edifying employment, but it served to pass the time, which, having no books or employment, hung very heavily on our hands.

The weather now changed, and the winter set in; we were glad to put on our thick clothes, which we found very comfortable, except that they afforded a great harbour to the vermin: this was, however, by this time only a secondary consideration, as the cold weather had rendered them very torpid, and they did not bite so hard. We had only two meals a day, morning and evening, and these being soon settled, and[Pg 80] not being allowed anything in the middle of the day, we made bags of our old clothes, and at breakfast-time filled them with rice, when the servants were out of the room, and stowed them away for a mid-day meal. The servants discovered it once or twice, but we generally managed to secrete some rice from our breakfast.