From Woodcut in 1774 (3rd) Edition of ‘History of the Rebellion.’

Frontispiece to Vol. I.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

This book was limited to a printing of 250 copies; this etext is derived from copy #187 (the number in the book is handwritten).

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

The four battle-plan illustrations have each been moved to the end of the Chapter in which they appear.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some other minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

Impression strictly limited to 250 copies, of

which this copy is No. 187

Types taken down.

Frontispiece to Vol. I.

THE

COLLECTED WRITINGS

OF

Dougal Graham

‘Skellat’ Bellman of Glasgow

EDITED WITH NOTES

Together with a Biographical and Bibliographical Introduction, and a Sketch

of the Chap Literature of Scotland

BY

GEORGE MAC GREGOR

Author of ‘The History of Glasgow’ and Member of the Glasgow

Archæological Society

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I.

For Subscribers and Private Circulation

GLASGOW: THOMAS D. MORISON

MDCCCLXXXIII

Sir Walter Scott and William Motherwell, it has been recorded, both intended to do something towards the preservation of the works and fame of the literary pedlar and bellman of Glasgow: the former by reprinting the first edition of The History of the Rebellion, and the latter by a history of the Chap Literature of Scotland, in which, of course, Dougal Graham should have been a prominent figure. Neither of these eminent Scotsmen, however, found fitting opportunity to carry their intentions into effect. This is all the more to be regretted when it is considered that few men were better able to undertake the task they had proposed for themselves. In the fifty years that have elapsed since Scott and Motherwell made the world acquainted with their abandoned projects, no serious attempt has been made to preserve the writings of Dougal Graham. These works have been floating about the country in unconsidered fragments, and, notwithstanding the efforts of a few gentlemen of the past and present generations, have ever been in danger of utter destruction.

The Editor of these volumes has endeavoured to combine the intentions of Scott and Motherwell. After long and careful search, he has been able to bring together extremely rare and unique editions of Graham’s chap-books. Many of these works are rich in illustration of the manners and customs of the people during the period of their first publication; and the Editor, by foot-notes, and otherwise, has tried to explain obscurities, or trace the origin and development of peculiar customs. He has also noted many passages containing valuable contributions to the folk-lore literature of Scotland. The various editions that have come under his notice have been[6] carefully collated; and while the oldest editions are here given, any important differences between them and subsequent issues have been marked. The Editor considered it no part of his duty to ‘improve’ his author, for he believed that to the extent he sought to effect such so-called ‘improvements,’ the work would cease to be that of Graham. Every production has been given, as far as could be found, in the condition in which it proceeded from his pen; and by doing this the Editor thought he would best perform his duty to his author and to the public. A glossary of obsolete, or imperfectly understood, words, has been given at the end of the second volume.

In the prosecution of his labours, the Editor laid himself under obligation to George Gray, Esq., Clerk of the Peace, Glasgow, whose unequalled collection of the popular literature of Scotland (many of the most valuable specimens having once been in the possession of the late Dr. David Laing) has been laid under heavy contribution; to Alex. Macdonald, Esq., Lynedoch Street; Matthew Shields, Esq., Secretary of the Stock Exchange, Glasgow; John Wordie, Esq., Buckingham Terrace; Prof. George Stephens, LL.D., F.S.A., Copenhagen; Thomas Gray, Esq., Ashton Terrace; and John Alexander, Esq., West Regent Street. His thanks are also due to J. Whiteford Mackenzie, Esq., W. S., Edinburgh; J. T. Clark, Esq., Advocates’ Library, Edinburgh; Bailie William Wilson, Glasgow; George W. Clark, Esq., Dumbreck; and James Richardson, Esq., Queen Street, Glasgow.

Glasgow, June, 1883.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | 5 |

| Editorial Introduction: | |

| I.—Biography of Dougal Graham | 9 |

| II.—The Writings of Dougal Graham | 28 |

| III.—The Chap-Literature of Scotland | 68 |

| History of the Rebellion: | |

| Preface | 83 |

| Chapter I.—Introduction and Origin of the War, Charles’ landing in Scotland and march to Tranent | 85 |

| Chapter II.—Battle of Preston pans—Rebels’ return to Edinburgh, and behaviour there | 97 |

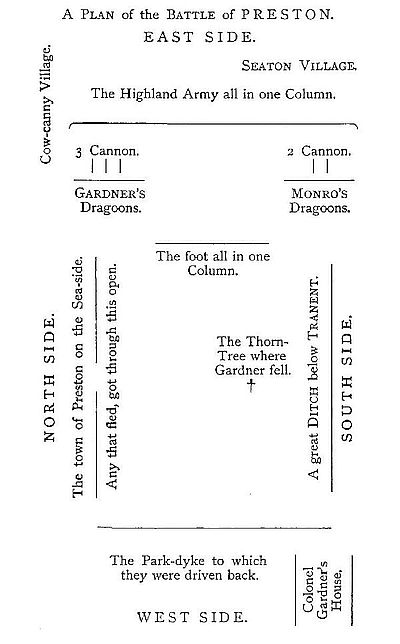

| Plan of the Battle of Preston | 100 |

| Chapter III.—Their March into England—Taking of Carlisle—Rout through England and retreat back | 106 |

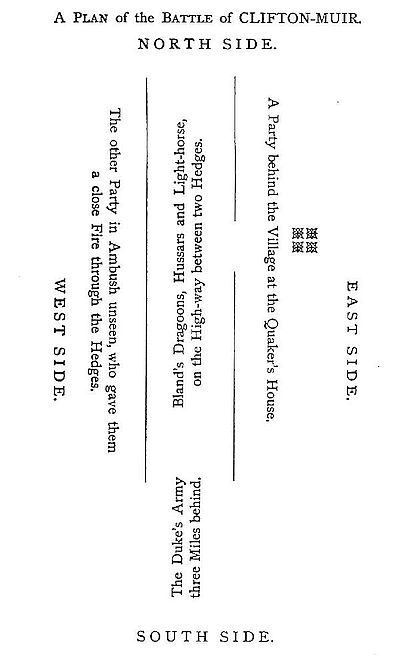

| Plan of the Battle of Clifton-Muir | 112 |

| Chapter IV.—Retaking of Carlisle by Cumberland—His return to London—Battle of Inverurie—The Rebels March from Dumfries by Glasgow to Stirling | 118 |

| Chapter V.—Siege of Stirling Castle—Battle of Falkirk | 126 |

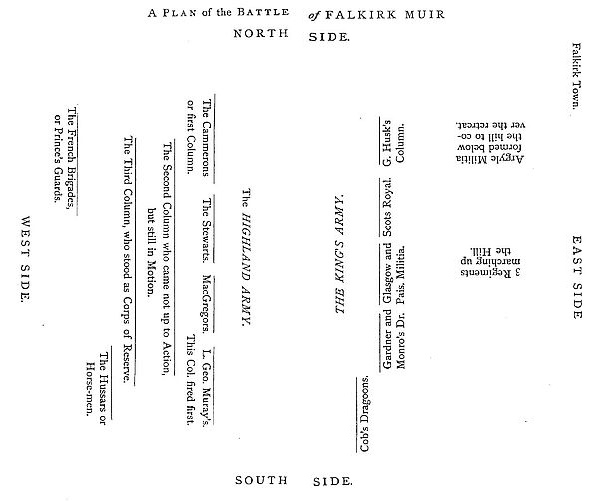

| Plan of the Battle of Falkirk | 130 |

| Chapter VI.—The Duke’s return—His Speech to the Army—March to Stirling—Explosion of St. Ninian’s Church | 140 |

| Chapter VII.—The Duke’s arrival at Stirling—The Rebels’ Retreat, and the Rout both Armies took to the North | 145 |

| Chapter VIII.—Blowing up the Castle of Cargarf by Earl of Ancram—Skirmishes at Keith and Inverness &c. | 148 |

| [8] Chapter IX.—Kings Army pass the Spey—Battle of Culloden—Defeat of Rebels &c. | 157 |

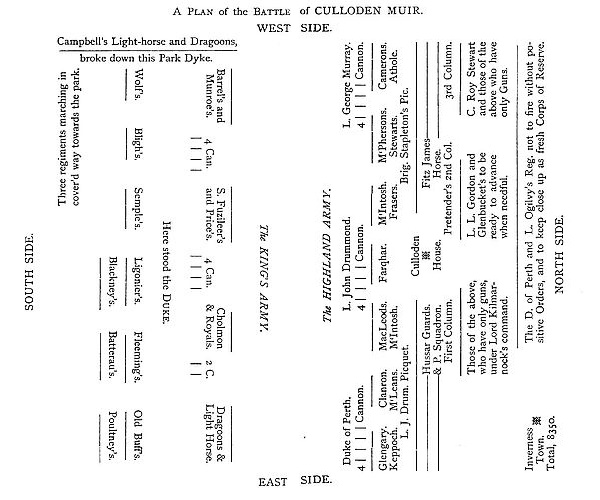

| Plan of the Battle of Culloden Muir | 162 |

| Chapter X.—Charles’ flight—Arrival in the Isles—Hardships, hidings, and narrow escape | 167 |

| Chapter XI.—Procedure of the King’s men against the suspected—Confusion in the Army and severity against the Clans | 182 |

| Chapter XII.—Sundry dangers and hardships on the main shore—Meets with six men who relieve him—Almost starved—Goes to Lochaber—Meets with Lochiel—Gets off from Moidart | 205 |

| Chapter XIII.—Arrives at France—Reception there | 218 |

| Chapter XIV.—Trial and Execution of severals at Kensington, Brampton, and Carlisle—The Lords Kilmarnock, Cromartie, Balmerino, Lovat, and Charles Ratcliff | 221 |

| Chapter XV.—Conclusion—Charles interrupts the Congress—Is seized at the Opera—Carried to the Castle of Vincennes—And forced to leave France | 240 |

| A Quaker’s Address to Prince Charles | 245 |

| Copy of the Rebels’ Orders before the Battle of Culloden | 249 |

| Miss Flora’s Lament: A Song | 250 |

| The Author’s Address to all in general | 251 |

| John Highlandman’s Remarks on Glasgow | 255 |

| Turnimspike | 261 |

| Tugal M‘Tagger | 265 |

| Had awa frae me, Donald | 269 |

The negligence of contemporaries by failing to appreciate the real worth of the great men of their time has often been a subject of remark. No special case need be cited to give point to the recurrence of the proposition here, for many such instances will readily suggest themselves to the mind. The reasons for this fact are many, and of divergent natures. Though it is beyond the scope of the present inquiry to discuss the general question, it may be observed, however, that some of the more potent causes which in the past have led to this unfortunate result are being rapidly removed through the spread of knowledge among the great mass of the people, and through the remarkable activity of the press in its various branches. Personal gossip regarding the hereditarily and individually great is now and then served up to the public, and it is always received with unmistakable relish. Autobiography, also, has become fashionable, and this, within recent years, has often shed light upon opinions and actions about which some doubts had formerly existed. These and other circumstances, in themselves perhaps not unmixed good, will tend to keep the biographers of the great men of this and the last generation from being placed in the awkward position in which almost all who attempt to record the lives of men who have achieved local or universal fame prior to the present century must at times find themselves placed. Insufficient data is the great obstacle in the way of the latter class. Traditions difficult to credit and as difficult to refute; suggestions more or less[10] probable; and many obscurities, all incline to make their work perplexing, and, to a certain extent, unsatisfactory. Yet the task must be undertaken, and the earlier the better, in order that such scraps of information as have come down from the past to the present may be preserved.

Dougal Graham, the literary pedlar and bellman of Glasgow, like many a greater man, has suffered unmerited neglect, and the value of his work was not discovered, or appreciated, until it was almost too late to retrieve the loss involved by the remissness of his contemporaries and immediate successors. Motherwell, lamenting this fact, says very truly, ‘That a man who, in his day and generation, was so famous, should have left no dear recollections behind him; some Boswell to record his life, actions, and conversation, need be subject of admiration to no one who has reflected on the contemptuous neglect with which Time often treats the most illustrious dead.’[1] Graham was first noticed as having done something for the literature of his country by Mr. E. J. Spence, of London, who in 1811 published Sketches of the Manners, Customs, and Scenery of Scotland. Motherwell, in the short-lived Paisley Magazine, next set forth fully Graham’s title to the regard of his compatriots, and rescued a few recollections concerning him which, in the course of a year or two more, would have been lost. M‘Vean, in the appendix to his edition of M‘Ure’s History of Glasgow, issued in 1830, added a few additional particulars. Then Dr. Strang, through the medium of his work on Glasgow and its Clubs, contributed his mite to the small collection of knowledge concerning our author. Graham has provided only one or two details about himself; an advertisement in a Glasgow newspaper fixes the date of one of the most important events of his life; and Dr. Strang has preserved some stanzas of an elegy on his death, written by some unknown poetaster. There, practically, our knowledge ceases. All beyond what is to be gained from these sources is tradition or inference, and not a little of what has[11] thus been put on record has been questioned. A ‘metrical account of the author,’ according to an existing tradition, was prefixed to an early issue of Graham’s History of the Rebellion of 1745–46, but owing to the disappearance of the first and second, and some of the subsequent editions, this account, if it ever existed, can now afford no assistance, nor can the tradition itself be traced to its source. Sir Walter Scott felt interested in Dougal’s work, but unfortunately he has contributed nothing to his biography, though it is believed to have been his intention to have done so. Such being the state of matters, it is only fair at this stage to assume that comparatively few of the events in the life of Dougal Graham have been ascertained beyond doubt, and that much that is related about him might be overturned even by some minute discovery. The probabilities, however, are against such a happy occurrence at so remote a period. His career, in so far as it is known, is not without a touch of romance, and it furnishes the key to a proper acquaintance with his works.

Graham, according to all accounts, was born in the village of Raploch, near Stirling, in or about the year 1724. If, as has been supposed, his History of John Cheap the Chapman is autobiographical, this is his own story of that important event—‘I, John Cheap by chance, at some certain time, doubtless against my will, was born at the Hottom, near Habertehoy Mill. My father was a Scots Highlandman, and my mother a Yorkshire wench, but honest, which causes me to be of a mongrel kind.’ Should this account be accurate, the names of the places seem to be veiled; but the uncertainty as to its application to Graham himself makes it of comparatively little value. Unfortunately, Nature endowed him with a deformed body, and his physical defects developed with his growth. His parents, from their humble position in life, were unable to give him anything beyond the common education of the time, which was of a very scant description, but he seems to have learned more by his native wit than by the instructions of the schoolmaster. Taught no trade, his youth[12] would probably be spent at farm work, or at such odd employment as he could find, it may have been in the weaver’s shop, or in the saw-pit, much the same, in all likelihood, as his father had done before him, and as we may still find men doing in remote country hamlets. Leaving the old home under the shadow of Stirling Castle, Graham went in his early youth as a servant to a small farmer in the neighbourhood of the quaint little village of Campsie. A tradition regarding his residence there lingered about the place for nearly a century, for Spence saw traces of a turf cottage said to be the birth-place and early residence of Dougal Graham.[2] As there are no good grounds for questioning the statement that Graham’s birth-place was Raploch, may it not be considered a feasible idea, in view of Spence’s remark, that our author’s parents removed to Campsie, and that he went with them? How long Dougal remained with the farmer is unknown. Of an unsettled disposition, he, like his creation John Cheap, made himself a chapman when very young, in great hopes of being rich when he became old; and for some years he wandered over the country in the exercise of his craft. The political events of the time, however, effected another and more important change in his career, and rapidly developed in him the mental capabilities with which nature had, by way of compensation, endowed him.

The outbreak of the Jacobite Rebellion in 1745 found Graham ready to follow the Young Chevalier. When the Highland army was on its southward march, he joined it on the 13th of September of that year, at the Ford of Frew, on the Forth. At that time he was probably about twenty-one years of age. The capacity in which he became attached to the Prince’s forces has been matter for conjecture. His physical deformities are assumed to have unfitted him for active service, and everything points to the conclusion that he was not a soldier, but rather a sutler, or camp-follower, blending, probably, his political aspirations with commercial pursuits. In the preface to his History of the Rebellion, he avoids saying[13] he participated actively in the events he records, but plainly states that he had ‘been an eye-witness to most of the movements of the armies, from the rebels first crossing the Ford of Frew to their final defeat at Culloden.’ Throughout the whole course of the seven months’ campaign, Graham accompanied the rebel army, and while he has carefully recorded its movements, he has given no indication of how he himself was occupied, or of any adventures that may have fallen to his share. There can be little doubt that, to a man of his temperament, the march to Derby and the retreat upon Inverness, would be highly educative in its effects, by showing him life in various parts of the country he had in all likelihood never visited before, and by bringing him into contact with men of all ranks. In this short period his knowledge of men and manners would be largely increased, and the experience thus gained would greatly facilitate the production of those graphic and truthful descriptions which sometimes adorn—sometimes, it must also be admitted, tarnish—the literary efforts of his later years.

Until this time, Graham is not known to have made any effort in the direction of literature, though, in view of the magnitude of the task he set before himself on the conclusion of the rebellion, it is not improbable he may have courted the Muses from afar, and indulged in poetical, or rhythmical, fancies for the amusement of his customers and entertainers in his youthful chapman days. However that may be, Dougal, immediately after the disaster at Culloden, rapidly made his way homewards, and set about committing to verse a narrative of the expedition of Prince Charles. The self-imposed duty was great, but he was equal to it. The battle of Culloden was fought on the 16th of April, 1746, and five months later Graham’s work was announced. In the Glasgow Courant, of the 29th September, the following advertisement appeared:—

‘That there is to be sold by James Duncan, Printer in Glasgow, in the Saltmercat, the 2nd Shop below Gibson’s Wynd, a Book intituled A full, particular, and true Account of the late Rebellion in the Year 1745 and 1746, beginning with[14] the Pretender’s Embarking for Scotland, and then an Account of every Battle, Siege, and Skirmish that has happened in either Scotland or England.

‘To which is added, several Addresses and Epistles to the Pope, Pagans, Poets, and the Pretender: all in Metre. Price Four Pence. But any Booksellers or Packmen may have them easier from the said James Duncan, or the Author, D. Grahame.

‘The like has not been done in Scotland since the Days of Sir David Lindsay.’

There is every reason to believe that this work became popular immediately on its publication. Scattered broadcast over Scotland by chapmen and others, while the events of which it treated were still agitating the minds of the people, Graham’s name by it would be brought boldly to the front, and there would be opened up for him the possibilities of a career wider than any he could have contemplated under ordinary circumstances. In every way the work appears to have been a success, and the judgment pronounced upon it by Dr. Robert Chambers has been concurred in by all who have read the production—‘The poetry is, of course, in some cases a little grotesque, but the matter of the work is in many instances valuable. It contains, and in this consists the chief value of all such productions, many minute facts which a work of more pretension would not admit.’[3] Sir Walter Scott’s estimate of it was not less favourable, for, writing to Dr. Strang in 1830, he said—‘It really contained some traits and circumstances of manners worth preserving.’[4]

Although the issue of the History of the Rebellion was probably large, it is remarkable that now, and for many years past, no copy of the first edition has been known to exist. It would be difficult to explain the cause of such a total disappearance. The fact must be regretted both from literary and bibliographical points of view, for a copy of it, besides being of interest in itself, would clear up several obscurities and differences of opinion that have arisen in relation to it and subsequent editions.

Prior to the publication of the History of the Rebellion,[15] Graham was not a resident in Glasgow, though it is probable he would be known to many there, for he must have had frequent occasion to visit the city for the purpose of purchasing his stock-in-trade. These visits would bring him into contact with booksellers, and the numerous tradesmen whose wares would be represented in his miscellaneous pack. The title-page of his work is said to have contained these lines:—

‘Composed by the poet, D. Graham,

In Stirlingshire he lives at hame.’

It would be useless to say whether the wide term ‘Stirlingshire’ bore reference to Raploch, or to Campsie, as has been suggested; but the verse may fairly be considered, by the prefix ‘poet’ to the author’s name, to give countenance to the inference that Graham was not quite a tyro in the art of verse-making, and that previous to the publication of his History he was regarded by his intimate friends, at least, as having qualified for the title. However that may be, Dougal seems now to have made Glasgow his home. Possibly he still continued to ply his calling as a pedlar; but he added to this a profession for which his natural capabilities specially adapted him. In Glasgow, he became the poet of passing events. Little of local importance seemed to have escaped him, and the few metrical pieces now extant, and attributed to him by various authorities, can only be regarded as the representatives of an extensive issue of facetious broadsides and chap-book ballads. Among those believed to be referable to this period of his life, are John Hielandman’s Remarks on Glasgow, and Turnimspike. Although these have never been acknowledged by Graham himself, in the formal way that he has acknowledged the authorship of the History of the Rebellion, there is a consensus of opinion that these two poems are undoubtedly his production. In them the acquaintance he made with Highland modes of thought and expression during the progress of the Jacobite campaign, served him in good stead. M‘Vean attributes a humorous piece, entitled Tugal M‘Tagger, to Graham, but this has been questioned on several grounds, perhaps the most forcible suggestion being, that its style and rhythm are liker[16] the work of Alexander Rodger than of Graham. Personally, we feel inclined to support M‘Vean, and that for a variety of reasons, which may be better explained when dealing with the bibliography of our author’s works; while other metrical compositions of a similar character will also fall to be considered under the same head.

Dougal was now a man of some note, and, in addition, he is believed to have gradually worked himself into a position of comparative freedom from pecuniary troubles. In the time of his poverty he vented his ill nature on his Roman Catholic fellow-subjects in verse far from elegant, charging them with having brought about, for reasons best known to himself, the unsatisfactory state of his exchequer:—

‘You Papists are a cursed race,

And this I tell you to your face;

And your images of gold so fine,

Their curses come on me and mine.

Likewise themselves at any rate,

For money now is ill to get.

I have run my money to an en’,

And have nouther paper nor pen

To write thir lines the way you see me,

And there’s none for to supplie me.’

Like many another man, Graham becomes incoherent when indulging in strong language. But matters did not always remain in this sad state, and when he published the second edition of his History of the Rebellion he was able to call himself ‘Dougal Graham, merchant,’ showing he had advanced a step in his commercial position. There is no reason to suppose he had a place of business, such as a shop or warehouse, but the probability is that he had become one of the better class of chapmen, whose packs contained a large variety of finer goods than were usually hawked through the country.

The second edition of the History of the Rebellion was published in 1752, probably with additions to include the adventures of Prince Charles after the defeat at Culloden. This edition, like the first, has disappeared, and at present no copy is known to exist. The re-issue of his work would assist[17] Graham in his pecuniary affairs, and it is said that he was able to begin a business which, even in these early days, would require some little capital. According to M‘Vean, Graham, after 1752, became a printer, and, like Buchan, the chronicler of Peterhead, he composed his works and set them up at the case without committing them to writing; or, as Strang puts it, he was in the habit of at once spinning thought into typography. Beyond that there is no information as to Dougal’s experience at the printing trade, though it must suggest itself as strange that so many of his chap-books should be issued by other parties, by Mr. Caldwell of Paisley, for instance, who is reported by Motherwell to have said:—‘We were aye fain to get a haud of some new piece frae him.’

Like Sir Walter Scott, who took a great interest in him and his works, Graham after a time appears to have turned his attention more particularly to prose composition, indulging rarely in verse. The period during which most of his prose chap-books were written and issued was probably between 1752 and 1774, the latter being the date of the publication of the third edition of his History of the Rebellion; though one or two are known to have appeared subsequent to that date. These works would greatly add to his credit with the people, and there can be no doubt that they had a most extensive circulation. ‘A’ his works took weel,’ says Mr. Caldwell, Motherwell’s informant, ‘they were level to the meanest capacity, and had plenty o’ coarse jokes to season them. I never kent a history of Dougal’s that stuck in the sale yet.’ Better testimony as to their popularity could scarcely be desired; and that the author was awarded a share of the favour his works received cannot be doubted. It has sometimes been thought that several of his chap-books were to a certain extent autobiographical—such, for instance, as John Cheap the Chapman—but the absolute impossibility of separating fact from fiction makes them of no value in this direction. Whether printed by himself or others the number of his works still known to exist prove him to have been a most prolific writer, and it can be fairly assumed that, in a pecuniary sense,[18] they were successful. None of them appear to have been published under Graham’s own name, but were either issued anonymously or under a cognomen which would probably be well understood in his own time as referring to him, such as ‘The Scots’ Piper,’ ‘John Falkirk,’ and ‘Merry Andrew at Tamtallon.’

An advertisement which appeared in the Glasgow Journal of 14th June, 1764, has raised the question of Graham’s domestic relations. Everything known points to the conclusion that he never entered into the conjugal yoke. The announcement spoken of ran thus:—

‘Notice.—Whereas, Jean Stark, spouse to Dougal Graham, ale-seller, above the Cross, Glasgow, has parted from her husband, he thinks it proper to inform the public that she be inhibit by him from contracting debt in his name, or yet receiving any debt due to him, after this present date.’

It has been usual to assume that this advertisement had no reference to our author, and, even though the names are the same, we see no reason to dissent from the general verdict. There is neither direct information nor obscure indication of Graham having at any time been an ‘ale-seller.’ The incident, however, has given Professor Fraser an opportunity of pointing out a failing of Dougal’s—‘In one sense, he was always a large dealer in spirits, but it is not so certain that he was actually a publican.’[5] Judging from his works, and if the few traditions concerning him are to be accepted as evidence on this point, he was not a teetotaller, but that in itself was no remarkable circumstance in the times in which he lived.

An event of the first importance in Graham’s life was his appointment to the post of skellat bellman of the city of Glasgow. One would naturally have thought that in this matter at least there would have been no room for any dubiety concerning the various circumstances of the appointment, especially as it was to a post of some credit under one of the most ancient municipal corporations in Scotland, but that is[19] not so. The ‘skellat’ bell, it may be explained, was the one used for ordinary announcements by the town-crier, as the ‘mort’ bell was in use on the intimation of death. In former times the crier, on obtaining possession of the two bells, had, according to the Burgh Records, ‘to cum bund for the soume of thrie scoir pundis’ Scots, or £5 sterling; and in addition to the importance of the office, it was always regarded as being of some pecuniary value. As the appointment was in the gift of the magistrates, it is surprising that no notice is taken in the Town Council Records of Graham’s incumbency. Motherwell put himself to some trouble in this matter, and wrote to Dr. Cleland, author of the Annals of Glasgow, then Superintendent of Public Works in the city, requesting information. In October, 1828, he received this reply—‘With regard to Dougal Graham, I may safely say there is nothing in the Records concerning him. This, from my own knowledge, corroborated by Mr. Thomson, one of our Town-clerks, who lately made an index of everything in the books for 150 years back.’ In order to satisfy himself on this point, the editor of these volumes took advantage of the opportunity kindly afforded him of going over the Burgh Records in the Town Clerk’s Office, and a careful search over the Council Minutes for a period of fully forty years was unproductive of any result other than that recorded by Dr. Cleland. As to the date of the appointment, therefore, some doubt exists. Turner, a town officer of fully eighty years, told Cleland that when he was a boy of about ten years of age, he remembered Graham as bellman, and Motherwell infers from this statement that our author was enjoying the whole emoluments of office about 1750. M‘Vean, however, is of a different opinion, and says Graham could not have been bellman earlier than 1770, ‘as an old gentleman remembers other four bellmen, who held office before Dougal, and after the year 1764.’ Possibly Turner’s memory may have been failing him in his old age, and he may not have been accurate by ten or fifteen years. M‘Vean was certainly in as good a position as any one to ascertain the true version, and there seems no reason why his[20] statement should not be accepted in preference to the haphazard guess by Motherwell.

Tradition has it that Graham did not obtain the office of bellman without some little difficulty, because of his connection with the Jacobite movement. Here is the story as given by Mr. Caldwell, the Paisley publisher:—‘In his youth he was in the Pretender’s service, and on that account had a sair faught to get the place o’ bellman, for the Glasgow bailies had an illbrew o’ the Hielanders, and were just doun-richt wicked against onybody that had melled wi’ the rebels; but Dougie was a pawkey chield, and managed to wyse them ower to his ain interests, pretending that he was a staunch King’s man, and pressed into the Prince’s service sair against his will, and when he was naithing mair than a hafflins callant, that scarcely kent his left hand frae his richt, or a B frae a bull’s fit.’ In addition to this subtle reasoning with the magistrates, Dougal is said by some writers to have effected very material alterations on the third edition of his History of the Rebellion, published in 1774, in order to please the Whig patrons of the office to which he aspired. Here is a difficulty not easily overcome. Caldwell’s information was likely to be correct, and it is further supported by the knowledge that during the Jacobite risings the Glasgow bailies, and the citizens generally, were staunch supporters of the House of Hanover. The first thought that must suggest itself to the mind is, that it was not at all likely that Graham would seek to publish in Glasgow a Jacobite history of the Rebellion, at a time when the city authorities were applying to Parliament for an indemnification for the money and supplies levied on them by the Prince and his army. But assuming that Graham did publish a history of this complexion, we have M‘Vean’s statement, to all appearance founded upon a personal knowledge of the second edition—though he seems to regard it as the first—in these words:—‘In 1752 Dougal talks of the rebels with a great deal of virulence; in 1774 he softens his tone, and occasionally introduces apologies for their conduct.’ Possibly no one of the present generation, or of the one[21] immediately preceding it, has ever seen a copy of this second edition; and in the absence of other and more conclusive evidence, the ipse dixit of M‘Vean must be accepted, and it goes directly against the assumption that Graham changed the political colouring of the third edition of his history to please the Glasgow bailies. If his appointment as bellman took place in 1750, as Motherwell, on what have been considered too slender grounds, has suggested, there might be some reason for entertaining the idea; but taking the date given by M‘Vean as approximately accurate it seems altogether out of the question. Caldwell, with his admitted knowledge of the incident, does not even hint at such an action on Graham’s part, but only supplies a very feasible account of the explanation afforded to the magistrates. Then, again, it could not be the case surely, if the bailies were ‘wicked against onybody that had melled wi’ the rebels,’ that the best way to appease them would be to introduce into the History of the Rebellion apologies for the conduct of those whom they regarded with such detestation. Dr. David Laing, writing, apparently, with a personal acquaintance of the second edition, says:—‘The second edition, 1752, bears, “Printed for and sold by Dougal Graham, merchant in Glasgow.” In the third edition, 1774, the work was entirely re-written, and not improved.... The first edition is so extremely rare, that only one copy is known to be preserved, and, as a literary curiosity, it might be worth reprinting; although it demolishes the fine story of the author’s difficulty in obtaining the bellman’s place from the Glasgow bailies, on account of his being a Jacobite, and having joined the Pretender’s army.’[6] But more than that, there are in the third edition itself some lines which go against the notion of alterations in respect of the colouring of the events recorded. In ‘The Author’s Address to all in General’ there is this verse:—

‘Now, gentle readers, I have let ye ken,

My very thoughts, from heart and pen,

’Tis needless now for to conten’,

Or yet controule,

For there’s not a word o’t I can men’,

So ye must thole.’

He then proceeds to describe barbarities on both sides, of which he had been witness. In the preface also he says:—‘I have no dread of any Body’s finding Fault with me for telling the Truth, because Charles has no Sway here; Duke William, once the Idol of the loyal British, is gone to the House of Silence, and, I believe, if I should take the Liberty to tell the Truth of him, no Body could blame me.’ The contention here is not that Graham was not sufficiently worldly to stoop to trimming, but rather that the undoubted alterations made on the third edition were not of the character many have imagined them to be. M‘Vean says that many ‘curious passages’ in the 1752 edition were suppressed in the one of 1774, but he makes that statement with reference to the toning down of the virulence against the rebels. Of course the disappearance of the first and second editions precludes the final and decided settlement of this not unimportant question, but the arguments and citations now brought forward can only lead to the impression that Graham made no alterations on the political tone of the third edition of his history in order to win the Glasgow bailies over to his cause. There were alterations and amendments, but these, it may be surmised, would be more of a literary than political character. The suggestion that they were of a different nature appears to have arisen from a mistaken notion of M‘Vean’s statement, which notion, by some means or other, became connected with the difficulty Graham had in obtaining the office of bellman. The two together make a most probable story, but it is a story which seems to be founded upon insufficient premises. It is curious that a somewhat similar misunderstanding arose with regard to Chambers’s History of the Rebellion of 1745–6, and that in order to put the public right, the author had to pen such words as these, as a preface to his seventh[23] edition:—‘It has been customary to call it [this history] a Jacobite history. To this let me demur. Of the whole attempt of 1745 I disapprove as most men do.... But, on the other hand, those who followed Charles Edward in his hazardous enterprise, acted according to their lights, with heroic self-devotion.... Knowing how these men did all in honour, I deem it but just that their adventures should be detailed with impartiality, and their unavoidable misfortunes be spoken of with humane feeling. There is no other Jacobitism in the book that I am aware of.’

But leaving the region of debate, it will be refreshing to turn to a humorous story on record, as to the competition Graham had to face before he became bellman. There were many applicants for the situation, and the magistrates decided that the merits of each should be put to a practical test. Accordingly all the candidates were instructed to be present on a certain day in the back-yard of the old Town’s Hospital, then situated in what is now known as Great Clyde Street. The magistrates were present as judges, and there were with them, no doubt, many of the leading citizens to witness the interesting spectacle. All the other competitors having shown their skill with the bell, and demonstrated the quality of their vocal powers, Dougal’s turn came. He entered into the spirit of the contest, and his physical peculiarities would greatly assist him. He rang the bell in a surprising manner, and called out in stentorian tones—

‘Caller herring at the Broomielaw,

Three a penny, three a penny!’

adding, pawkily—

‘Indeed, my friends,

But it’s a’ a blewflum,

For the herring’s no catch’d,

And the boat’s no come.’

The victory was his, and the other competitors were out of the reckoning. He had shown himself every way suited for the office—to be endowed with that ready wit which has always been a characteristic of the true Scottish bellman—and he was[24] accordingly invested with the official garments, and with the magisterial authority to exercise his new calling. In the year 1774, probably two or three years after the events just related, the third edition of Graham’s History of the Rebellion, with amendments, was published. This edition, like its predecessors, was successful, and it is understood to be the last edition issued during the author’s lifetime. Dougal, as an official of the Corporation of Glasgow, had now become a personage of no little importance in the community. These were not the days of cheap advertisements, reaching half-a-million readers in a few hours, or of posters and handbills apprising the lieges of meetings and sales, or of the lost, stolen, and strayed. All this Graham, with the aid of his bell, had to intimate to the public. The ‘trial scene’ affords a specimen of the kind of work he had to perform. He had also, to a certain extent, to act as attendant on the magistracy. The story goes that Dougal was on one occasion passing along the Gallowgate, making some intimation or another. Several officers of the 42nd Highlanders, then returned from the American War of Independence, where their regiment had been severely handled by the colonists, were dining in the Saracen’s Head Inn, situated at the foot of the Dovehill. They knew Dougal of old, and they thought to have a joke at his expense. One of them put his head out of the window, and called to the bellman—‘What’s that you’ve got on your back, Dougal?’ This was rather a personal reference, for Dougal had the misfortune to be ‘humphie backit.’ But he was not put out by the question, for he at once silenced his interrogator by answering—‘It’s Bunker’s Hill; do you choose to mount?’ The good stories about Graham are said to have been legion, but they have, unfortunately, been allowed to die out; otherwise, a collection of his jokes and bons mots might have been a formidable rival to the now classical Joe Miller.

But death put an end to Dougal’s happy-go-lucky existence while he was still in the prime of life. He died on the 20th of July, 1779, at the age of fifty-five or fifty-six, in what circumstances, or of what trouble, cannot now be discovered.[25] These were not the days of newspaper obituaries, or he would certainly have been awarded a half-column notice. This, of itself, is unfortunate, for then many biographical details could have been obtained, and subsequent writers of Graham’s life would have been able to produce a record of his career more satisfactory to themselves and their readers. That Dougal did not die unregretted, is witnessed by an elegy of twelve stanzas, written at the time of his death by some unknown poetaster. This lament has, unfortunately, only come down to the present generation in a fragmentary form, Dr. Strang[7] having preserved seven of the verses:—

‘Ye mothers fond! O be not blate

To mourn poor Dougal’s hapless fate,

Ofttimes you know he did you get

Your wander’d weans;

To find them out, both soon and late,

He spared no pains.

‘Our footmen now sad tune may sing,

For none like him the streets made ring,

Nor quick intelligence could bring

Of caller fish,

Of salmon, herring, cod, or ling,

Just to their wish.

‘The Bull Inn and the Saracen,

Were both well served with him at e’en,

As ofttimes we have heard and seen

Him call retour,

For Edinburgh, Greenock, and Irvine,

At any hour.

‘The honest wives he pleased right well,

When he did cry braw new cheap meal,

Cheap butter, barley, cheese, and veal

Was selling fast.

They often call’d him “lucky chiel,”

As he went past.

‘Had any rambler in the night,

Broken a lamp and then ta’en flight,

[26]Dougal would bring the same to light

’Gainst the next day,

Which made the drunk, mischievous wight

Right dearly pay.

‘It is well known unto his praise,

He well deserved the poet’s bays,

So sweet was his harmonious lays;

Loud-sounding fame

Alone can tell, how all his days

He bore that name.

‘Of witty jokes he had such store,

Johnson could not have pleased you more;

Or with loud laughter made you roar

As he could do:

He had still something ne’er before

Exposed to view.’

In concluding this biographical notice of Dougal Graham, it will be appropriate to make one or two quotations which will give a full and just idea of his personality. Our author seems to have taken a portrait of himself—and through his modesty it is not too flattering—when he thus delineates John Cheap, the Chapman:—‘John Cheap the chapman, was a very comical short thick fellow, with a broad face and a long nose; both lame and lazy, and something leacherous among the lasses; he chused rather to sit idle than work at any time, as he was a hater of hard labour. No man needed to offer him cheese and bread after he cursed he would not have it; for he would blush at bread and milk, when hungry, as a beggar doth at a bawbee. He got the name of John Cheap the chapman, by his selling twenty needles for a penny, and twa leather laces for a farthing.’ Mr. Caldwell, of Paisley, told Motherwell that ‘Dougald was an unco glib body at the pen, and could screed aff a bit penny history in less than nae time. A’ his warks took weel—they were level to the meanest capacity, and had plenty o’ coarse jokes to season them. I never kent a history of Dougald’s that stack in the sale yet, and we were aye fain to get a haud of some new piece frae him.’ Dr. Cleland, on the information of[27] Turner, an old Glasgow town-officer, was able to supply Motherwell with this notice:—‘When Turner was a boy of about ten years of age, Dougald was bellman, and being very poetical, he collected a crowd of boys round him at every corner where he rang the bell. Turner says that Dougald was “a bit wee gash bodie under five feet.”’ ‘John Falkirk’ is believed to have been a nickname assumed by, or applied to, Graham upon various occasions, and this description of him is prefixed to one of the editions of John Falkirk’s Cariches, published soon after his death:—‘John Falkirk, commonly called the Scots Piper, was a curious little witty fellow, with a round face and a broad nose. None of his companions could answer the many witty questions he proposed to them, therefore he became the wonder of the age in which he lived.... In a word, he was

‘“The wittiest fellow in his time,

Either for Prose or making Rhyme.”’

M‘Vean says:—‘Dougal was lame of one leg, and had a large hunch on his back, and another protuberance on his breast.’ Strang, referring to the portrait prefixed to the third edition of the History of the Rebellion, and reproduced in this volume, thus pictures Graham: ‘Only fancy a little man scarcely five feet in height, with a Punch-like nose, with a hump on his back, a protuberance on his breast, and a halt in his gait, donned in a long scarlet coat nearly reaching the ground, blue breeches, white stockings, shoes with large buckles, and a cocked hat perched on his head, and you have before you the comic author, the witty bellman, the Rabelais of Scottish ploughmen, herds, and handicraftsmen!’ But here is an even more graphic pen and ink portrait, some of the details, no doubt, filled in from imagination, but with the tout ensemble admirably preserved, and true to life:—‘It must have been a goodly sight to see Dougal in his official robes, the cynosure of every eye in the busy Trongate, or the life and soul of the company in Mrs. M‘Larty’s “wee bit public,” where he and his cronies were wont to quench their native thirst. He must, indeed, have been a grotesque figure. “A wee bit gash body[28] under five feet high;” with a round, broad, red and much-seamed face; a prominent nose, truncated à la Punch; an Æsopian hump on one shoulder, and a large protuberance on one breast; legs of unequal length and peculiar shape; a long scarlet coat hanging down from the shoulders to the ground; blue breeches set off by white stockings, and large brilliantly buckled shoes: with an imposing cocked hat perched fiercely on one side of the massive head.’[8]

These word paintings, together with the two portraits given in this work, will afford the reader a most vivid conception of the appearance of the king of Scottish chapmen.

It must be manifest, from all that has been stated in the preceding pages, that anything like a complete bibliography of the works of Dougal Graham is now impossible. This is the case for many reasons, kindred in their nature to those that have rendered an absolutely satisfactory biography unattainable; but more especially because, with the exception of the History of the Rebellion, Graham did not formally, on title-pages or elsewhere, acknowledge the authorship of the ballads and prose chap-books attributed to him on more or less trustworthy authority. Another important point is that he did not seem to have interfered in any way with their re-issue after their first publication, for there is evidence that in his life-time editions were published in various places, other than Glasgow and Paisley, to all appearance independent of the author.

Motherwell, in this as in other matters relating to Graham, acting under the inspiration of information given him by Mr. George Caldwell, the Paisley publisher, ascribes the following works to Dougal, adding the dates of the earliest editions he had in his possession when he wrote his article for the Paisley Magazine:—

The Whole Proceedings of Jockey and Maggy. In five parts. Carefully corrected and revised by the Author. Glasgow: printed for, and sold by, the Booksellers in Town and Country. 1783.

The Comical Sayings of Pady from Cork, with his Coat button’d behind. In all its parts. Carefully corrected by the Author. Glasgow: printed for George Caldwell, Bookseller in Paisley. 1784.

The History and Comical Transactions of Lothian Tom. In six parts. Glasgow: printed by J. & M. Robertson. 1793.

The History of John Cheap the Chapman. In three parts. Glasgow: printed and sold by J. & M. Robertson. 1786.

The Comical and Witty Jokes of John Falkirk the Merry Piper. Glasgow: printed in the year 1779.

The Scots Piper’s Queries, or John Falkirk’s Cariches for the trial of Dull Wits. (n.d.)

Janet Clinker’s Orations on the Virtues of Old Women and the Pride of the Young. (n.d.)

Leper the Tailor. Two parts. Glasgow, 1779.

The Comical History of Simple John and his Twelve Misfortunes.

Motherwell adds that ‘John Falkirk’s Jokes and Cariches’ and ‘Janet Clinker’s Orations’ were frequently found printed together, and that the last named was sometimes issued as a separate publication, with the title—‘Grannie M‘Nab’s Lecture in the Society of Clashing Wives, Glasgow, on Witless Mithers and Dandy Daughters, who bring them up to hoodwink the men, and deceive them with their braw dresses, when they can neither wash a sark, mak’ parritch, or gang to the well.’ In addition to the works already enumerated, Motherwell mentions the following, regarding which he says that though he had no authority for ascribing them to Graham he would not be surprised to find that he was the author of them:—

This concludes Motherwell’s testimony; and here is that given by Mr. M‘Vean, the antiquarian bookseller, whose authority can be scarcely less valid than that of the Paisley Poet. Dr. Strang says:—‘In a manuscript of the late Mr. M‘Vean, the antiquarian bibliopole of the High Street, we find the following list of the Opera Dugaldi, so far as he had met with them, keeping out of view his lyrical productions,[30] which were very numerous. Perhaps no man ever devoted more time to ferret out bibliographical curiosities connected with Scotland than Mr. M‘Vean....’:—

1. George Buchanan, six parts.

2. Paddy from Cork, three parts.

3. Leper the Tailor, two parts.

4. John Falkirk the Merry Piper.

5. Janet Clinker’s Oration on the Virtues of the Old, and the Pride of Young, Women.

6. John Falkirk’s Curiosities [Cariches], five parts.

7. John Cheap the Chapman, three parts.

8. Lothian Tom, six parts.

9. The History of Buckhaven, with cuts.

10. Jocky and Maggy’s Courtship, five parts.

11. The Follower [Follies] of Witless Women; or, the History of Haveral Wives.

12. The Young Creelman’s [Coalman’s] Courtship to a Creelwife’s Daughter, two parts.

13. Simple John and his Twelve Misfortunes.

14. The Grand Solemnity of the Tailor’s Funeral, who lay nine days in state on his own Shop-board; together with his last Will.

15. The Remarkable Life and Transactions of Alexander Hamwinkle, Heckler, Dancing-master, and Ale-seller in Glasgow, now banished for Coining.

16. The Dying Groans of Sir John Barleycorn, being his grievous Complaint against the Brewers of bad Ale; to which is added, Donald Drouth’s Reply, with a large Description of his Drunken Wife.

17. A Warning to the Methodist Preachers.

18. A Second Warning to the Methodist Preachers.

Strang himself, who, in some respects, must be regarded as an authority upon matters relating to Graham, does not condescend upon bibliographical details; and the lists now given consequently include the testimony of the only two writers whose opinions or suggestions bear with anything like direct authority on the subject.

Two poems entitled John Hielandman’s Remarks on Glasgow and Turnimspike have been unhesitatingly attributed to Graham by all authorities; Tugal M‘Tagger, another metrical production, was believed by M‘Vean to be his composition, though there has been some subsequent questioning in the matter; while the following have been claimed or suggested as his work by M‘Vean, in a note to his edition of M‘Ure’s History of Glasgow:—Verses on the Pride of Women, a[31] poem on the Popular Superstitions of Scotland, a Dialogue between the Pope and the Prince of Darkness, and an epitaph on the Third Command. Professor Fraser, in his list, inserts Proverbs on the Pride of Women, in addition to the verses on the same subject; but he gives no authority for the addition.

Having thus traced the results of the labours of those who have already written concerning Graham’s miscellaneous works, something must now be said about his History of the Rebellion. The total disappearance of the first and second editions of that curious publication renders, as has already been hinted, any statements or opinions regarding them of doubtful value, with the exception, of course, of the date of their issue to the public. The advertisement announcing the intended issue of the first edition in 1746, has been quoted, and is undeniably authentic; but whether the work was published immediately after, or some time later, is a moot point. That it was published in that year is indicated by what follows, which is believed to be the contents of the title-page of the editio princeps:—

‘A full, particular, and true Account of the Rebellion, in the years 1745–6.

Composed by the Poet D. Graham,

In Stirlingshire he lives at hame.

To the Tune of The Gallant Grahams. To which is added, Several other Poems by the same Author. Glasgow, Printed and Sold by James Duncan, &c., 1746. Price fourpence halfpenny.’

This edition was a duodecimo consisting of 84 pp. Probably the matter it contained, assuming no alterations of this portion, would end with the ninth chapter of later issues, the last lines of which form an appropriate conclusion to the fatal adventure of Prince Charles:—

‘This was a day of lamentation,

Made many brave men leave their nation.

Their eyes were open’d, all was vain,

Now grief and sorrow was their gain.’

It may be interesting to note that the published price of this edition, was, if the title-page quoted is authentic, a halfpenny more than that at which it was announced; but that is a[32] trivial affair compared with what is suggested by the words—‘To the Tune of The Gallant Grahams.’ This may be taken as indicating that the matter of the first edition was not altogether got up in the purely historical method, but that it was to a certain extent what might be called either an historic drama, or a dramatic history. This idea may not be accurate, but the apparent impossibility of referring to the first edition itself precludes any definite knowledge on the subject. Fraser, speaking of the disappearance of this edition, remarks:—‘Yet, at least a few copies of the original history must be hidden somewhere. So late as 1830, the author of “Waverley” had one in his possession, a fac-simile of which he intended to publish, with the view of presenting it to the Maitland Club, but sickness intervened to derange his plans, and two years later, death stepped in and snatched the pen from the great magician.’[9] Again, Dr. David Laing says:—‘The first edition is so extremely rare that only one copy is known to be preserved, and, as a literary curiosity, it might be worth reprinting.’[10] It is to be regretted that Dr. Laing’s statement was not more explicit. As for the assumption made by Professor Fraser, it is only natural to imagine that the whole edition cannot have altogether disappeared, and that a copy or two should still be in existence. But he takes for granted regarding Sir Walter Scott’s intentions, and his preparedness to carry them into effect, rather more than the words of Dr. Strang, on which he seems to have founded, will legitimately bear. This is what Strang says:—‘So late as the year 1830, Sir Walter Scott even “entertained the idea of printing a correct copy of the original edition,” with the view of presenting it to the Maitland Club as his contribution, stating, as he did in a letter addressed to the writer, that he thought “it really contained some traits and circumstances of manners worth preserving.”’[11] Scott’s intention is here evident, but it in no way bears that he was in possession of a first edition. In point of fact,[33] he had no copy of it at the time of his death, two years after this letter was written, as a reference to the catalogue of the Abbotsford Library will show. That catalogue contains this reference to Graham’s History:—‘Graham’s (Dougal, Bellman of Glasgow) Impartial History of the Rise, Progress, and Extinction of the late Rebellion, &c. (in doggrel verse). 3rd edit. 18mo. Glasgow: 1774.’ So far for the first edition.

As for the second edition of the History of the Rebellion, published in 1752, it has also disappeared. There is no reason to believe that, beyond a slight enlargement and some few alterations, there was any material change in the work. Its tone is indicated by the remark made by M‘Vean:—‘The History of the Rebellion, published by Dougal in 1752, differs very much from the third edition, published in 1774. This last appears to have been greatly altered and enlarged, and many curious passages in the early edition are suppressed in this. In 1752 Dougal talks of the rebels with a great deal of virulence, in 1774 he softens his tone, and occasionally introduces apologies for their conduct. In 1752 Dougal styles himself “merchant in Glasgow;” a rhyming merchant could not be expected to be rich, and he says—

“You Papists are a cursed race,”’ &c.

The lines, of which the one quoted is the first, have already been given in the biography, and there is no need for their repetition here. But it is worthy of note that M‘Vean states, to a certain extent indirectly, that they formed part of the matter in the second edition, and if that is the case they, it must be admitted, fully confirm his statement as to that edition containing passages in which Graham talked of the rebels with a great deal of virulence; and, possibly, they may be taken as specimens of many others of a like nature. Some writers have suggested that Graham may have learned the printing trade while this edition was passing through the press, and it has been suspected that he may have had something to do with the printing of it himself. That is not likely, or M‘Vean, who appears to have had a somewhat intimate acquaintance with the work, would have mentioned it.

No such doubts, however, exist as to the third edition of the History of the Rebellion, which, though rare, may be seen occasionally. It was published in 1774, and bears on the title-page this lengthy statement of its contents:—‘An Impartial History of the Rise, Progress and Extinction of the late Rebellion in Britain, in the years 1745 and 1746, giving an account of every Battle, Skirmish, and Siege, from the time of the Pretender’s coming out of France, until he landed in France again: with Plans of the Battles of Prestonpans, Clifton, Falkirk, and Culloden, with a real Description of his Dangers and Travels through the Highland Isles, after the Break at Culloden. By D. Graham. The Third Edition, with Amendments. Glasgow: Printed by John Robertson. MDCCLXXIV.’ The narrative in this edition occupies 174 pp. It consists of fifteen chapters, containing in all 5562 lines, and is preceded by a preface of two pages, the title-page, and a full-page woodcut of the author, bearing underneath it this couplet:—

‘From brain and pen, O virtue drope,

Vice fly as Charlie, and John Cope.’

At the conclusion of the narrative are—‘A Quaker’s Address to Prince Charles, shewing what was the Cause and Ground of his Misfortunes,’ of 146 lines; a copy of ‘The Rebels’ Orders before the Battle of Culloden’; ‘Miss Flora’s Lament—A Song,’ of ten four-line stanzas; ‘The Author’s Address to all in general,’ of fourteen six-line stanzas; and two pages of contents—making a total of 192 pages. The text of the third edition has been used in the reprinting of the History of the Rebellion for this volume.

The subsequent editions, so far as they have been discovered, need only be mentioned. No trace has been found of the fourth edition, though it must have been published soon after Graham’s death. The fifth edition received this notice from a writer of last century:—‘In 1787, “An impartial history of the rebellion in Britain, in the years 1745 and 1746, by Douglas Graham” (the fifth edition), was printed at Glasgow by J. & M. Robertson. This history is in Hudibrastic[35] metre. This is a sorry performance.’[12] The seventh edition was published in Glasgow by J. & M. Robertson, Saltmarket, in 1803; the eighth by the same firm in 1808; the ninth in Falkirk, by T. Johnston, 1812; while the last, what its number it would be difficult to say, was published in Aberdeen, in 1850, conjointly by Alexander Watson and Alexander Murdoch. The Aberdeen edition does not bear Graham’s name on the title-page, and instead of the author’s preface, it contains a ‘Genealogical and Historical Introduction,’ taken from the introduction to Chambers’s History of the Rebellion. It is remarkable that the Advocates’ Library, Edinburgh, should only possess an eighth edition.

Something must now be said about the miscellaneous poetical works of Dougal Graham. The best known of these may be said to be John Hielandman’s Remarks on Glasgow, a humorous sketch of considerable power, valuable also, because of the information it affords regarding the leading features of the City of St. Mungo in the middle of last century. M‘Vean has put it on record that this poem had long been popular, although it was not generally known that it was by Graham that Glasgow had been ‘married to immortal verse.’[13] The date of its first publication is unknown, but it has been generally supposed to have been written in the decade subsequent to Dougal’s settlement in Glasgow in 1746. The earliest copy that has been seen by any writer was in one of the early penny broadsides issued by J. & M. Robertson, of the Saltmarket, Glasgow, who long occupied a prominent position as publishers of popular literature. As a literary production John Hielandman has not attracted so much notice as might have been expected from writers on Scottish literature, but even a casual glance will show that it is a composition of great merit, abounding in graphic touches and humorous situations. It must be admitted, however, that the interest attaching to it has been almost entirely local, and to that circumstance may be attributed the fact that its merits have been frequently overlooked.

Turnimspike has received more attention than any other of Graham’s poems, with the exception, perhaps, of his History of the Rebellion; and it has obtained the unqualified approval of all the literary antiquaries who have had occasion to speak of it. Sir Walter Scott said the Turnimspike alone was sufficient to entitle Graham to immortality.[14] Dr. Charles Mackay has taken advantage of a note upon it, to tell a story which has considerable bearing upon the state of feeling exhibited in the poem itself. ‘Turnimspike, or Turnpike,’ he says, ‘is ludicrously descriptive of the agonies of a real Highlander at the introduction of toll gates, and other paraphernalia of modern civilisation, into the remote mountain fastnesses of his native land. Long after the suppression of the Rebellion, great consternation was excited in Ross-shire, by the fact that a sheriff’s officer had actually served a writ in Tain. “Lord, preserve us!” said an Highlandman to his neighbour, “What’ll come next? The law has reached Tain.”’[15] Burns, in his Strictures on Scottish Song, expressed admiration for Turnimspike, on account of its local humour, but he did not seem to have known the author; though Motherwell, in his edition of the works of the Ayrshire bard, supplies a few notes concerning Graham, to whom he attributes the poem. Stenhouse, in his illustrative notes to Johnson’s Museum, says—‘This truly comic ballad, beginning Hersell be Highland Shentleman, by an anonymous author, does not appear either in the Tea-Table Miscellany, or the Orpheus Caledonius. It is preserved, however, in Herd’s Collection of 1769.... From its excellent broad humour, and the ludicrous specimen of a Highlander’s broken English, it has long been a popular favourite in the lower districts of Scotland. It is adapted to the ancient air of “Clout the Caldron”.’ No writer has yet ventured to fix the date of the publication of this poem. It may, however, be pointed out that the first General Turnpike Act for Scotland was 7 Geo. III., c. 42 (1766–7), and it is not improbable the passing of this Act may have been the occasion[37] of the verses which, it has been seen, obtained a place in Herd’s Collection in 1769. They were, in all likelihood, issued in broadside or chap-book form previous to that date.

The two songs already discussed, are now without quibble regarded as the work of Dougal Graham; but there are two others probably from his pen, which bear the mark of his genius, were published in his time, but which have not yet been generally regarded as his by literary antiquaries. The first of these is Tugal M‘Tagger, unhesitatingly ascribed to Dougal by the venerable M‘Vean. It has been suggested that this work has traces of Alexander Rodger, on the ground that the rhythm has a flow similar to that characteristic of Rodger’s poems; but this reason of itself cannot be taken as evidence in favour of the suggestion, in view of the fact that Graham’s style was itself very uneven, and, probably on account of carelessness, some of his pieces are as bad as others are good. M‘Vean’s statement, also, must be allowed to go a considerable length in a matter of this kind. The song is in Dougal’s best vein, and may be regarded as a worthy counterpart to Turnimspike. The following extract, by pointing to the occasion and probable date of the composition, helps towards the conclusion that it was the work of Graham:—‘The Court of Session, in 1754, made an Act of Sederunt, establishing an equality of ranking among all arrestors and poinders within a certain period of bankruptcy. But this was a mere experiment; and upon the expiration of the Act, which was in force for only four years, it was not renewed. The law fell back into its old state of imperfection; priority gave preference, and, on the slightest alarm, creditors poured in with diligence against the unhappy debtor, and the most unjust preferences took place among the creditors. In this position it continued until 1772, when the first Sequestration Act, 12 Geo. III., c. 72, was passed. It enacted that, on a debtor’s bankruptcy, and upon a petition to the Court of Session by any creditor, a sequestration of his personal estate should be awarded, which should have the effect of equalising all arrestments and poindings used within thirty days of the[38] date of petition; that the estate should be vested in a factor proposed by the creditors, and be distributed by him according to the directions of Court; or, if it should seem more eligible to the creditors, extrajudicially by a trustee elected by them, as under a private trust deed. When, in 1783, this statute came to be renewed, the alarm occasioned by the novelty of the arrangements had given way to a conviction that bankruptcies were much more beneficially administered under the new system, imperfect as it was, than under the Common Law.’[16] Such a radical alteration on the law would afford excellent opportunity for a popular ballad, and as there is no good reason for doubting M‘Vean’s statement that Graham was the author of Tugal M‘Tagger, it must in the meantime be accepted as his production. The Act being passed in 1772, the ballad would probably be published in the same year. That it retained its popularity for a long time, is attested by a note written upon it in 1869:—‘Tugal M‘Tagger was a very popular song in Glasgow about forty years ago. It used to be sung by Mr. Livingstone at the Theatre Royal there.’[17] Even yet, it is not unknown to the people, and may be found in some penny collections.

Another song, believed to be by Graham, but which has not yet met with general approval, is an old version of Had awa frae me, Donald. Stenhouse has indirectly suggested it as Dougal’s work, by saying that it was probably by the same hand that produced Turnimspike, and he mentions it as appearing in Herd’s Collection in 1769. This song appears also in The Blackbird, a collection of songs, ‘few of which,’ according to the title-page, ‘are to be found in any collection,’ published in Edinburgh in 1764. The likeness which struck Stenhouse must also force upon every reader of the piece the same suspicion; and without being dogmatic upon the point, the editor of these sheets sees no reason why the version of Had[39] awa frae me, Donald, given in this volume, should not be admitted into the list of works ‘probably’ written by Graham.

This includes, so far as can be discovered, the metrical works, still existing, which have been attributed to Graham. There are others, M‘Vean mentions, but none of them appear to have been seen since his time; and in the hope that they may be ultimately discovered, their names, or, perhaps it may be more proper to say, the subjects of which they treat, are here given:—Verses on the Popular Superstitions of Scotland, Rhythmical Dialogue between the Pope and the Prince of Darkness, An Epitaph on the Third Command, and Verses on the Pride of Women. As for the second of these pieces, it may be interesting to note that a twelve-page pamphlet was issued in 1792, bearing a similar title—Dialogue between the Pope and Devil, on the present political state of Europe. This, however, refers to the events immediately preceding the French Revolution, and cannot, therefore, be looked upon as the work of Graham. A passing reference is made by the Devil to the beginnings of the Reform movement in Glasgow, in these words:—

‘In Glasgow freedom sounds in every mouth;

And if I could but deign to tell the truth,

Not since the day I first saw Paradise,

Did earth maintain such a respectful race.’

But the works upon which the fame of Dougal Graham chiefly rests, are his chap-books. On this matter Motherwell said that if Graham had only written the History of the Rebellion, ‘we believe he never would have occupied our thoughts for a moment; but as one who subsequently contributed largely to the amusement of the lower classes of his countrymen, we love to think of the facetious bellman.’[18] It has already been stated that the period during which the most of these chap-books were written and published, was probably between 1752 and 1774, although the first editions of several are known to have appeared subsequent to the latter date. On a subject in[40] which he took so much fruitful interest, no apology is needed for again quoting Motherwell, who says:—‘Of some of Graham’s penny histories we had a fair assortment at one time, principally printed by J. & M. Robertson, Saltmarket, Glasgow, which we believe might well be esteemed first editions, but some unprincipled scoundrel has bereaved us of that treasure. There are a number of infamous creatures, who acquire large libraries of curious things, by borrowing books they never mean to return, and some not unfrequently slide a volume into their pocket, at the very moment you are fool enough to busy yourself in showing them some nice typographic gem, or bibliographic rarity. These dishonest and heartless villains, ought to be cut above the breath whenever they cross the threshold. They deserve no more courtesy than was of old vouchsafed to witches, under bond and indenture to the Devil.’[19] Out of the ‘scanty wreck’ left him, Motherwell was able to furnish the list given in a previous page.[20] This was probably the nearest that any collector ever attained to having a collection of first or very early editions of Graham’s chap-books; but even in 1828 it was hardly possible to state when the first editions were issued. It would be worse than useless to endeavour to trace the chronological order of their publication, or to fix definitely dates for one or all of them. The fact seems to be that the first editions have either all disappeared, or else bear in their title-page the vague, but not uncommon intimation—‘Printed in this present year.’ The danger of attempting such an arrangement may be best shown by a statement made by the late Sheriff Strathern, a learned local antiquary, in a paper on ‘Chapman Literature,’ delivered before the Glasgow Archæological Society, on the 6th April, 1863. Mr. Strathern, in the course of a somewhat exhaustive sketch, says:—‘It is difficult to give them in the order of publication; but I have, at some little trouble, collected a few of the editions, and, as near as I can reach it, this is the order in which the works appeared. His earliest was “The Whole Proceedings[41] of Jockey and Maggy,” in five parts. It was published in 1783.... “The Comical Sayings of Paddy from Cork” followed, and was printed for George Caldwell, Paisley, in 1784,’ etc. Then follows a long list of chaps by Graham, which, according to Sheriff Strathern, were published subsequent to 1784. The learned Sheriff may possibly have been correct in his surmise that the works he had enumerated were published in the order he had given them, but surely not on the understanding that Graham’s ‘earliest’ was issued in 1783? It is not at all likely that Graham left his works for publication after his death. Indeed, there is positive evidence that they were in the market long before 1783, and any edition of that date must be a reprint. This incident of itself shows the danger of attempting to fix dates for Dougal’s ‘penny histories,’ or even the order of their publication, without the absolute evidence of the books themselves, if they bear any, or the testimony of any one who, like Mr. Caldwell, actively took part in their issue to the public. Even Caldwell offers no information on the matter. The only statement in this direction, upon which any reliance can be placed, is one by Motherwell, when he states that the editio princeps of the second part of Leper the Taylor was published in 1779. Sheriff Strathern may have fallen into error by trusting the date, 1787, at which Motherwell fixed Graham’s death. That date, however, was only a surmise; and the true date was supplied by Strang.

It is a matter of some interest to notice that while many of Graham’s most popular chap-books have been issued to the public subsequent to the period to which literature of this class is assumed to belong, these modern editions, if they may be so called, have for the most part been greatly mutilated. Nearly all of them have been cut down, not apparently because of a desire to keep out the indelicate allusions which most of them contain—for comparatively few of these have been taken out—but on account of the exigencies of printing. In some cases a chap-book, originally of twenty-four or thirty-six closely printed pages, has been compressed into twenty-five, sixteen, or even eight pages of much larger print. The consequence[42] is, that most of the modern editions are utterly useless for all practical purposes, and, like most other abridgments, the souls of their originals have been driven from them. The truth of this remark will be indicated in the following pages; but it will be borne out to its fullest extent by a comparison between the early editions the editor has been able to reprint in these volumes, and those now in circulation.

The Whole Proceedings of Jockey and Maggy, admitted by all authorities to have been written by Graham, may be noticed first, as being one of his ablest and most characteristic works. It is written with great dramatic power, and affords many curious insights into manners and customs about the middle of last century. In respect of language, also, it possesses considerable value. Professor Fraser suggests that the first edition was in all likelihood published as early as 1755, but, as has already been seen, it would be inadvisable to fix any date, in the absence of either evidence or reasonable suspicion. In the work itself there is nothing but what might have been written at any time during the whole period of Dougal’s life. The edition, reprinted in this collection, bears the imprint:—‘Glasgow: Printed and Sold by J. & J. Robertson. MDCCLXXIX’—and is the earliest of which any mention has yet been made. It was thus published in the year of Graham’s death, and as the title-page states that it was ‘Carefully Corrected and Revised by the Author,’ it was probably one of the latest works upon which he was engaged. While most certainly not a first edition, it has the advantage of being, to a certain extent, fresh from the author, and on that account possesses a special value and interest. Motherwell’s copy was dated 1783, and also bore to have undergone the author’s revision. These editions both occupy thirty-six pages, and are in five parts; but in 1793 an edition, consisting only of three parts, was published. Since then, the three-part edition has been the one most commonly issued to the public, and it may still be found for sale. In 1823, however, the complete edition was reprinted, and a few copies of it may be seen occasionally. The abridgment, it must be noted, has seriously marred Graham’s production. In it the first two parts are[43] so far almost literal transcripts of the earlier editions, but parts three, four, and five, are omitted, a short and very imperfect summary of part five being inserted for part three. In addition, an epitaph and elegy on Jockey’s mother, whose death and burial are graphically described in the last part, are consistently left out.

Of a somewhat similar character to the chap-book just noticed is The Coalman’s Courtship of the Creelwife’s Daughter, though it is by no means so valuable as an exhibition of manners and superstitions. It contains, nevertheless, many interesting references, and it gives a vigorous description of real life among the lower classes in and around Edinburgh. Motherwell, it has been seen, only hesitatingly ascribed this work to Graham; but M‘Vean inserts it in his bibliography without any reservation, though it is curious that both these writers should make a mistake in naming it The Creelman’s Courtship. There is no good reason to doubt that Graham was the author of it, for the broad treatment of the subject, the animated dialogue, and the graphic descriptions, are all in Dougal’s best style. The edition reproduced in these volumes is the earliest to which any reference has yet been made, having been issued by Messrs. J. & J. Robertson, from their Saltmarket press, in 1782, though it bears on the title-page to be the tenth edition of the work. M‘Vean stated that the chap contained only two parts, but he had fallen into a mistake, for it really consists of three parts. The modern editions, with the exception of a few typographical alterations, are exact reprints of the one of 1782. Among those we have seen are two undated editions, bearing the following imprints—‘Glasgow: Printed for M‘Kenzie & Hutchison, Booksellers, 16, Saltmarket’; ‘Edinburgh: Printed by J. Morren, Cowgate.’