The ship went out safely, came back

safely. The pilot was unaware of anything

wrong. Somewhere in the depths of his brain

was locked the secret that made him

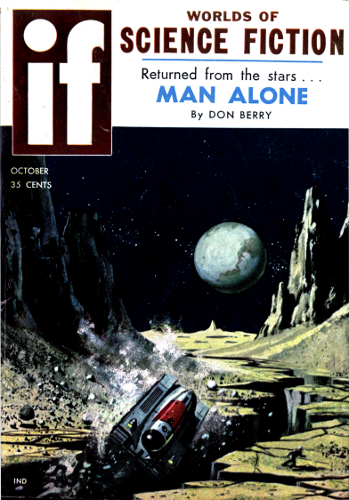

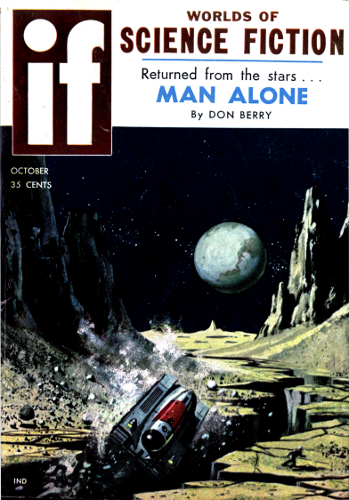

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Phoenix I belled out smoothly in the region of a G-type star. There was a bright flare as a few random hydrogen atoms were destroyed by the ship's sudden appearance. One moment space had been empty except for the few drifting atoms, and the next—the ship was there, squat and ugly.

Inside, a bell chimed sweetly, signalling the return to a universe of mass and gravitation and a limiting velocity called C. Colonel Richard Harkins glanced briefly out his forward port, and saw no more than he had expected to see.

At this distance the G-type star was no brighter or yellower than many another he had seen. For a man it might have been hard to tell which star it was. But the ship knew.

Within one of the ungainly bulges that sprouted along the length of Phoenix I, a score of instruments mindlessly swung to focus their receptors on the nearest body of star-mass.

Harkins leaned contentedly back in the padded control seat and watched while the needles gradually found their final position on dials. A few scattered lights bloomed on the console ahead of him. He grunted once with satisfaction as the thermoneedle steadied at 6,000° C. After that he was silent.

He leaned forward and flipped up two switches, and a faint sound of a woodpecker came into the control room as the spectrograph punched its data on a tape. The end of the tape began to come out of a slot. Harkins tore it off when the spectrograph was finished with it, threaded it on the feeder spool of the ship's calculator, and inserted the free end in the input slot.

The calculator blinked once at him, as if surprised, and spat out a little card with the single word SOL neatly printed in the center.

Harkins whistled softly to himself, happily. I had a true wife but I left her, he whistled. Old song. Old when he first heard it. Had a true....

He wondered vaguely what a "wife" was, but decided it probably didn't matter. Had a true wife but I left her, he whistled.

He was glad to be home.

The direction finder gave him a fix on Earth and he tried to isolate the unimportant star from the others in the same general direction, but he couldn't do it, visually. The ship would do it, though, he wasn't worried about that. He wished he could use the Skipdrive to get a little closer. It would take a long time to get in close on the atomic rockets. Several days, maybe.

Well, he had to do it. The Skipdrive wasn't dependable in mass-space. You couldn't tell what it was going to do when you got it too close to a large mass. He'd have to go in on the chemical.

Mass-space, he thought. Molasses-space, I call it.

Too slow, everything too slow, that was the trouble.

Reluctantly he switched off the Skipdrive's complacent purr. The sudden lack of noise in the cabin made him squint his eyes, and he thought he was going to get a headache for some reason. Abruptly, all the cabin furniture seemed very harsh and angular, distorted in some strange way so as to be distinctly irritating to him. He brushed his foot across the deck and the sound of his boot was rasping and annoying.

He didn't like this space much. It wasn't soft, it wasn't restful, it was all full of clutter and junk. He grimaced with distaste at the suddenly ugly console.

He looked down at the floor, frowning, pinching his nose between thumb and forefinger, flirting with the idea of turning the drive back on.

But for some reason he couldn't quite think of at the moment, he couldn't do that. He frowned more severely, but it didn't help; he still couldn't think of the reason he couldn't do it. That headache was coming on strong, now. He'd have to take something for it.

Well, well, he thought resignedly. Home again, home again.

He was sure he was glad to be home.

Home is the hunter, home from something something....

He couldn't remember any of the rest. What the hell was a hunter, anyway? They irritated him, these nonsense songs. He didn't know why he kept thinking about them. Hunters and wifes. Nonsense. Babble.

He keyed the directional instruments into the course-control and armed the starting charge for the chemical motors. When he had checked everything carefully, as he had been taught, he strapped himself into the control chair with his hand on the arm-rest over the firing button. He knew it was going to hurt him.

He fired, and it did hurt him, the sense of explosive pressure, the abrupt thundering vibration. It was not the same as the soft, enfolding purr of the Skipdrive, comforting, assuring, loving....

What's that? Loving?

A wife is a Martha, he thought. A Martha is a wife.

It seemed to mean something, but he didn't have time to decipher it before he passed out.

When he came to he immediately switched off the chemical drive. It had given him a good shove in the right direction, and that was all that was necessary. He would coast in now, and he had to save his fuel for maneuvering in atmosphere.

After that, he rested, trying to accustom himself to the harshness of things in mass-space.

His time-to-destination indicator gave him ten hours, when he began to feel uneasy. He couldn't pin-point the source of unease at first. He was fidgety, impatient. Or something that resembled those feelings. It was like when he couldn't remember why he wasn't supposed to turn the Skipdrive back on. It occurred to him that he wasn't thinking clearly, somehow.

He noticed to his surprise he had switched on his transmitter. Probably while he was drumming his fingers or something. He switched it off.

Thirty minutes later he found himself toying with the same switch. He had turned it on again. This was getting ridiculous. He shouldn't be so nervous.

He grinned wryly to himself. The transmitter switch, indeed. If ever a useless piece of junk had been put in Phoenix I, that was it. Transmitter switch!

He laughed aloud. And left the switch open.

He found himself staring with fascination at the microphone. It was pretty interesting, he had to admit that. It was mounted on the back of the control chair, on swivel arms. It could easily be pulled into position right in front of his face. Just as if it had been meant to. He fiddled with it interestedly, swinging it back and forth, seeing how it moved on the swivel arms.

He was interested in the way it moved so smoothly, that was all. By coincidence, when he let go of it, it was directly in front of him.

There was something picking at him, something was nagging at the back of his mind. He whistled under his breath and knuckled his eyes. He scrubbed at the top of his head with his right hand, as if he could rub the annoying thought. Suddenly he heard his own voice saying:

"Earth Control, this is Phoenix I. Come in please."

He looked up, startled. Now why would he say a thing like that?

And then, in the midst of his surprise, he repeated it!

"Earth Control, this is Phoenix I. Come in please."

He flipped the Receive switch without volition. His hands had suddenly developed a life of their own. He began to breathe more rapidly, and his forehead felt cool. He swallowed twice, quickly.

There was no answer on the receiver.

No what? Answer? What is "answer"?

"Estimate arrival four hundred seventy-two minutes," he said loudly, looking at the time-to-destination indicator.

There was a sudden flood of relief, washing away the irritation that had been picking away at the back of his mind. He felt at ease again. He turned off both transmitter and receiver and stood out of the control chair. He felt better now, but he was a little worried about what had happened.

He couldn't understand it. Suddenly he had lost control of himself, of his voice and his hands. He was doing meaningless things, saying things, making motions stupidly. Every movement he made, every act, was without pattern or sense.

He had a sudden thought, and it made his whole body grow cold and prickly, and he almost choked.

Maybe I'm going Nova.

He was near the edge of panic for a minute. Nova Nova Nova Nova.

Brightly flaring, burning out, lighting space around for billions of light years....

That was how it started, he knew. Unpredictability, variation without explanation.... He sat back down in the control chair, feeling shaky and weak and frightened.

By the time he had regained his balance, time-to-destination told him 453 minutes.

He guided Phoenix I into an orbit around Earth. He circled three times, braking steadily with his forward rockets until he entered atmosphere.

On his fifth pass he spotted his landing place. How he knew, he didn't quite understand, but he knew it when he saw it. There was a sense of satisfaction somewhere in him that told him, "That's it. That's the right place."

Each succeeding pass was lower and slower, until finally he was maneuvering the ungainly bulk of the ship like a plane, wholly in atmosphere.

Like a what?

But he was too busy to worry about it. Fighting the Phoenix I down in atmosphere required all his attention. Absently he noted the amazingly regular formations of rock surrounding his landing place.

His hands flew over the console automatically, a skilled performer playing a well-learned fugue without conscious attention to detail. The overall pattern was clear in his mind, and he knew with absolute confidence he could depend on his hands to take care of the necessary small motions that went to make up the large pattern.

He did not think: Upper left button third from end right bank rockets three-quarters correct deviation.

He thought: Straight. And his hand darted out.

The ground was near below him, now. He could see parts of the landscape through the port, wavering uncertainly in the heat waves from his landing blast.

Slower ... slower ... slower.... The roar was reflected loud off the flat below....

Touch.

Perfect, he thought happily. Perfect perfect perfect.

He leaned contentedly back in the control chair and watched the needles of the console gauges fall lifeless back to the pins.

He whistled a little tune under his breath and smiled.

Now what?

Get out.

He couldn't think of the reason for it, but he would do it. While he waited for the hull to cool, he dropped the exit ladder, listened to the whine of the servomotors.

He opened the port and stood at the edge, looking out. His headache had come back again, worse than ever, and he grimaced at the sudden pain.

Before him stretched the flat black plane of the landing pad, ending abruptly in the regular formations he had noted before. They were mostly white, and contrasted strongly with the black of the pad. They weren't, he realized, rock formations at all, they were—

They were—buildings, they—

His mind shied away from the thought.

It was silent. His headache seemed to be affecting his vision, somehow. Either that or the landing pad wasn't cool yet. When he looked toward the—toward the white formations at the edge of the pad, they seemed to waver slightly near the ground. Heat waves still, he decided.

Nimbly, and with a pleasant sense of being home again, he scrambled down the ladder and stood on the ground, tiny beneath the clumsy shape of Phoenix I.

About halfway between the edge of the pad and his ship stood a tiny cluster of thin, upright poles. From their bases he could see black, snakelike cables twisting off toward the edge, shifting in his uncertain vision. He walked toward them.

The silence was so complete it was unnatural. It was almost as if his ears were plugged, rather than the simple absence of sound. Well, he supposed that was natural, after all. He had lived with the buzzing purr of the Skipdrive and the thunder of the rockets so long, any silence would seem abnormal.

As he drew closer to the upright rods, he saw each one was topped with a bulge, a vaguely familiar....

They were microphones! They were just like the microphone in Phoenix I, the one he had fooled with.

He was sincerely puzzled. All that transmit-receive gadgetry in the ship had been foolish, but what was he to think of finding it here on his landing pad? It didn't make any sense. He was getting the uneasy sense of confusion again. The headache was becoming almost unbearable.

He walked over to the cluster of microphones. That was probably the place to start. He took the neck of one in his hand and pulled it, but it didn't move smoothly, as the one on his control chair had. It simply tipped awkwardly toward him.

Suddenly he felt something on his shoulder, and looked around quickly, but could see nothing. The pressure on his shoulder remained, and he vaguely brushed at it with his hand. It went away.

He set the microphone back upright and looked back at his ship. There was another pressure on his opposite shoulder, sudden and harder than the first had been. He slapped at it, and stepped back, uncertainly.

One of the microphones tipped toward him, but he hadn't touched it. He took another step backwards, and felt something close tightly around his left arm. He snapped his head to the left, but there was nothing there.

He twisted sharply away to the right, and the motion freed him, but his shoulder hit something solid. He gasped, and his throat tightened again. He raised his hand to his head. The headache was getting worse all the time.

Something touched him on the back.

He spun, crouching.

Nothing.

He stood straight again, his eyes wide, panting from the fear that was beginning to choke him. His fists clenched and unclenched as he tried to puzzle out what was happening to him.

The air closed abruptly around both arms simultaneously, gripping so tightly it hurt.

He shouted and twisted loose and started to run back toward the ship. He stumbled against an invisible something, fell against another, but it kept him upright and prevented his falling. Several times as he ran, things he could not see brushed him, touched him on the shoulders and back.

By the time he scrambled up the ladder, his breath was short, and coming in little whimpers. The headache was the greatest pain he thought he could ever have known, and he wondered if he were dying.

He had to kick at invisible things that clutched at his feet on the ladder, and when he reached the edge of the port he stood kicking and flailing at nothing until he was certain none of the—creatures, things were there.

He shut the port swiftly and ran breathlessly up to the control room. He threw himself into the padded chair.

Finally he lowered his head into his hands and began to weep.

2.

Night.

The land turned gray and silver and white under the chill light of the rising moon. The buildings of Gila Lake Base IV were sharp and distinct, glowing faintly in the moonlight as if lit somehow inside the concrete walls.

On the landing pad, Phoenix I squatted darkly, clumsily. The moon washed its bulbous flanks with cascading light that flowed down the long surfaces of the hull and disappeared into the absorbent blackness without trace. Tiny prickling reflections of stars glinted from the once-polished metal.

At the edges of the Base, where wire meshes stretched up out of the desert dividing the things of the desert from the things of men, nervous patrols paced forlornly in the night.

One of the blockhouses at the inner edge of the landing area presented two yellow rectangles of windows to the night. Inside the blockhouse were two men, talking.

One of the men was in uniform, and his collar held the discreet star-and-comet of a staff officer, SpaServ. He was young for his rank, perhaps in his early forties, with gray eyes that now were harried. He sat on the edge of his desk regarding the other man.

The second of the two was a civilian. He was slumped in an oddly incongruous overstuffed chair, with his legs stretched out straight before him. He held the bowl of an unlit pipe in both hands and sucked morosely on the stem as the SpaServ brigadier talked. He was slightly younger than the other, but his hair was beginning to thin at the temples. He had sharp blue eyes that regarded the tips of his shoes without apparent interest. Colin Meany was his name, and he was a psychiatrist.

Finally General Banning finished his account of the afternoon, raised his hands in a shrug, and said, "That's it. That's all we have."

Colin Meany took his pipe out of his mouth and regarded the tooth-marked bit curiously. He shoved it in his coat pocket and walked over to the window, looking out across the moon-flooded flat to the looming, ominous shape of Phoenix I. He stood with his hands clasped behind him, rocking gently back and forth on his toes.

"Ugly thing," he said casually.

Banning shrugged. The psychiatrist turned away from the window and sat down again. He began to fill his pipe.

"Where is he now?" he asked.

"In the ship," the general told him.

"What's he doing?"

Banning laughed bitterly. "Broadcasting a distress signal."

"Voice?"

"Does it matter?" the general asked.

"I don't know."

"No, it's code. It's an automatic tape. The kind all passenger vessels carry."

Colin considered this for a moment. "And he didn't say anything."

"Absolutely nothing," said General Banning. "He got out of the ship, walked over to the reception committee, slapped a few people and ran back to the ship and locked himself in."

"It doesn't make any sense."

"You're telling me?" After a second the general added almost wistfully, "He knocked Senator Gilroy down."

Colin laughed. "Good for him."

"Yeah," the general agreed. "That bastard fought us tooth and nail all the way down the line, cutting appropriations, taking our best men.... Then when we get a ship back, he's the first in line for the newsreels."

Colin looked up. "You have newsreels?"

"Sure, but I don't think they're processed yet."

"Why didn't you tell me that in the first place? Check them, will you?"

The general made a short phone call. When he hung up he looked embarrassed. "You want to see them?"

"Very much."

"There's a viewing room in Building Three," Banning said. "We can walk."

When the lights had come on again, Colin sat staring at the blank screen for a long time. Finally he sighed, stood and stretched.

"Well," Banning said. "What do you think?"

"I'll want to see it again. But it's pretty clear, I think."

The general looked up in surprise. "Clear? It's just the same thing I told you."

"Oh, no," Colin said. "You left out the most important part."

"What was that?"

"Your boy is blind and deaf."

"Blind and deaf! You're crazy. The ship, he looked at the ship, and the microphone, and...."

"Oh, it's pretty selective blindness," Colin said. He filled his pipe with maddening slowness and lit it before he spoke again.

"People," he said finally. "He doesn't see people. At all."

Harkins fell asleep leaning forward in the control chair with his head on his arms. When he wakened, the sky outside the viewport was turning dark. With a sense of sudden danger, he clamped down the metal shutters over the port. Methodically he climbed down catwalks the length of the ship, making certain all ports were secured both from entry and from sight. He didn't want to see outside.

When he had done this, he felt easier. Walking to the galley, he put a can of soup in the heater, and took it back up to the control room with him.

He sat there, absently eating his soup and staring ahead at the console. He noted he was beginning to get used to the harsh outlines it presented in this space. Suddenly he realized there was a red light on the board. He put the bowl of soup carefully on the deck and went over to the transmitter where a loop of tape was endlessly repeating itself, apparently broadcasting. He could not remember having inserted it. The empty spool lying beside the transmitter read AUTOMATIC DISTRESS CODE.

He understood all the words, all right, but put together they didn't seem to make any sense. AUTOMATIC DISTRESS CODE. What would it be for? Why would such a thing be broadcast? If you were in distress, you surely knew it without transmitting it.

He shook his head. Things were very bad with him. He was profoundly disturbed by his loss of control. Performing all sorts of meaningless actions without volition.... And now, with this tape, he had not even been conscious of the act, could not remember it.

He went back to the control chair and finished his bowl of soup.

Thinking about it, his meaningless activities had all been centered around one thing, this odd transmit-receive apparatus, this radio. He had looked at it before, and he realized it was very carefully constructed, and complicated. The wiring itself confused him. And more than that, he could not determine any possible use such a thing might have.

Thinking about it gave him the same prickly sensation at the back of his neck as when he thought about the nonsense words in the songs he knew. "Wife." Things like that.

He rubbed the back of his neck hard, until it hurt. He realized his headache had almost gone away when he secured the ports, but now it was coming back again.

Another light flashed on the console, and a melodic "beep—beep" began to sound from somewhere behind the panel.

Automatically he reached forward and flipped a switch, and the "beep—beep" stopped. Without surprise, he noticed it was the switch marked Receive.

So. When the light flashed and the "beep—beep" sounded he was supposed to throw that Receive switch. Presumably, then, he should receive something. Was that right?

He looked around the control room, but nothing happened.

Just on the edge of his consciousness there was a faint sussuration, but when he turned his attention to it, it disappeared. There was no sound. But when he thought of something else, it came back again.

It was like an image caught in the corner of his eye. There was nothing there, but sometimes you thought you caught just a flash of something out of the corner of your eye. Like this afternoon....

He shuddered at the recollection.

In all his life, he could not remember anything that had driven him into such pure panic as the loathsome invisible touches he had felt. What kind of creatures were these?

This was Earth. This was his home, it was where he belonged, and he couldn't remember anything about invisible....

Yes! Yes, he did remember! But there was still something wrong because—he couldn't think why.

He remembered walking on a grassy meadow on a spring day. The grass was rich and luxuriant and the sun was hot copper in the sky. He was walking toward the top of a hill. Right at the top there was a single small, green tree. He was going to go up and lie down under that tree and look down in the valley at the meadow. And beside him there was—a presence. He remembered turning to look, and—nothing. There was nothing there.

But the feeling of the presence next to him made him pleased, somehow. It was right. It was not menacing, like this afternoon, it was more—comforting. As the sound the Skipdrive made was comforting. It made him feel fine. But when he turned to look, there was nothing.

He could not remember.

What kind of presence? Like the ship? No, much smaller. Smaller even than himself. Compared to the ship, he was small, quite small. He was infinitely smaller than even planetary mass. And there were things on the ship that were smaller than he.

But he couldn't quite place himself with assurance on the scale of size. He was larger than some things, like the bowl of soup, and he was smaller than other things, like planets. He must be of a sort of medium size. But closer to the bowl of soup than the planet.

A wife is a Martha.

He remembered thinking that just as the rockets had fired. It was in the song.... He whistled a few bars. I had a good wife but I left her, oh, oh, oh, oh.

And it had something to do with the remembered—presence, when he was walking in the meadow.

But what was a Martha? You can't define a nonsense word in terms of another nonsense word. Or perhaps, he thought ruefully, you can't define it any other way.

A wife is a Martha. A wife is a Martha. A Martha is a wife.

Nothing.

But he felt the headache coming on again.

He went down to the galley again, and took the soup bowl with him. He put it in the washer, and rummaged around in the cabinets until he found the little white pills that helped his headaches. He took three of them before he went back up to the control room.

He had to make some kind of plans for—for what? Escape? He didn't want to escape. He was home. He wanted to stay here. But he had to deal with the—things, somehow. He wondered if they could be killed. There was no way to tell. If you killed one you couldn't see its body.

And he didn't have any weapons, at any rate. He would simply have to outsmart them. He wondered how smart they were. And how large. That would make a good deal of difference, how large they were.

He went to the viewport and cracked the shutter, just a little. It was dark. He didn't want to go out in the dark, that was too much. It would be too much risk. He would wait until morning.

In spite of the pills, the headache was getting worse, almost to the insane level it had been in the afternoon. He decided he'd better try to sleep.

3.

Colin and General Banning stood at the shoulder of the radio operator in Gila Base IV Central Control. It was just past midnight. Banning's fatigue was evident; Colin, having been involved a shorter time, still looked reasonably fresh.

Monotonously the radio tech droned: "Gila Control to Phoenix I come in please. Gila Control to Phoenix I come in please. Gila Control to Phoenix I come in please." After every third repetition of the chant, he switched to Receive and briefly listened to the buzz and crackle from the overhead speakers.

"Gila Control to Phoenix I...."

"Is he still transmitting the distress code?" Colin asked.

"Yes, sir," the tech said. "But he could still reply if he wanted to. Distress operates from a separate transmitter on a single fixed frequency. The ordinary transmitter isn't tied up."

"Is he receiving?"

"I think so. When we gave him the 'Message coming' impulse, he switched to receive. That was hours ago."

"Maybe he's tuned to the wrong frequency," Banning suggested.

The tech looked up in surprise, then resumed his respectful attitude toward the brass. "No, sir. His rig is a self-tuner. The signal automatically tunes the receiver to the right frequency. He's getting it, all right."

"In other words," Colin said, "your voice is being broadcast on the ship's speakers."

"As far as I can tell."

"Mm."

Colin leaned back against a chart table and pulled on his pipe for a few moments.

"Please go on, sergeant," he said finally. "Keep trying. But change the patter to 'please reply,' would you?"

"What difference does that make?" Banning asked. "That's what 'come in' means, anyway. Same thing."

"Just an idea," Colin said. "Why don't you get some rest? You look beat."

"What kind of an idea?" Banning said, rubbing his forehead.

"Can you get a couple of cots brought to your office?"

"Yes, but what's your idea?"

"Come on along and I'll tell you about it," Colin said.

They left Central Control, with the voice of the sergeant sounding behind them, "Gila Control to Phoenix I please reply. Gila Control...."

Reaching Banning's office, Colin sent one of the ubiquitous armed guards after two cots.

"You can't shoot all your energy at once," he pointed out, when Banning protested he didn't need the sleep. "If we're going to get Harkins out of that ship, we're going to have to stay in pretty good shape ourselves."

"All right," Banning grumbled. He made coffee on the hot plate from the bottom drawer of his desk, grinning at Colin like a small boy caught stealing cookies. "I like a little coffee once in a while," he explained unnecessarily.

When they had settled themselves with the coffee, Banning asked, "All right, now. Why'd you change 'come in please' to 'please reply'?"

"It's less ambiguous," Colin said. "'Come in please' could mean several things."

"So? Anybody with as much radio experience as Harkins knows what 'Come in please' means."

"You're going to have to get used to the idea you're not dealing with Harkins in this. Take the point of view, this is somebody you've never seen before. Somebody you have to figure out from scratch."

"Mm. I suppose so. Okay, why the change?"

"Well—" Colin hesitated. "First of all, this—blindness is purely a functional block of some kind. There's nothing organically wrong with his vision."

"I'm still not sure I go along with your blind-deaf idea," the General said dubiously.

"I'm virtually certain, after seeing the film strip again. Your Colonel Harkins behaves exactly like a man being molested by something he can't see."

"For the sake of argument, then...." Banning nodded.

"All right. Presupposing he does not want to see human beings—for whatever reason—there are several mechanisms he could use."

"He didn't even have to come back," Banning pointed out.

"That's one of the mechanisms. But he did come back. Why? Problem one, for the future. Mechanism two: Catalepsy. Suspension of all sensation and consciousness."

"Obviously not the case."

"Right. Mechanism three," Colin went on, ticking the points off on his fingers, "partial disorientation. Loss of perception of a single class of objects, human beings."

"Even that isn't entirely true," Banning said. "He felt people."

"That's right. And I think this is our opening wedge. Of the possible means of avoidance I named, partial disorientation is the least successful of all. It involves too many contradictions. He was disturbed by the microphones, for example. Why? Because they are meaningful only in a context of human beings. Communication. He would have to do some fancy twisting to avoid the notion of human beings. The same goes for any other human artifact. Somehow, in order to make the world 'reasonable' in his own terms, he has to explain the existence of these things, without admitting the existence of people who made and use them."

"Impossible."

"Very nearly. It means that some facet of his personality must be continually making decisions about what can be recognized and what cannot. His censoring mechanism is in a constant scramble to prevent certain data from reaching his conscious mind. It has to justify and explain away all data which would eventually point to the existence of human beings."

"What the hell does he think he is?" Banning asked angrily.

"I have no idea. Maybe that's problem two for the future. At any rate, as you pointed out, this is an impossible job. It must be infinitely more difficult now that he's on Earth, where there are so many more things to explain away. This is going to set up a terrific strain inside. It may break him."

"What would do that to a man?"

"I don't know that, either," Colin admitted. "Our first problem now is to get him out of the ship. And to do that, we have to contact him."

"This is why you changed to 'please reply'? What good is it going to do if he can't hear it, anyway?"

"That's the point. I think he can hear it. He can't recognize it, but that isn't quite the same thing. His eardrums still vibrate, the data gets in, all right. But it doesn't reach the conscious level. Fortunately, it isn't always necessary to be consciously aware of a stimulus before you can respond to it. Frequently a persistent stimulation just below the threshold of awareness will produce a response in the organism. Sub-threshold stimulation, it's called."

"Yeah," Banning said, "I've heard of it. Used it in advertising, didn't they?"

"For a while. Before Congress passed the Privacy Amendment."

"Okay. Now what?"

"Now we wait and see if it works. I'm going to take a nap. Wake me up if anything happens."

Colin stretched out on one of the cots, put his hands behind his head and soon was breathing deeply in an excellent imitation of sleep.

The clock on Banning's desk said 4:33 when his communicator chimed. Banning was off his cot and at the desk before the first soft echoes faded.

"Banning. Yes ... yes ... all right, right away."

"What is it?" Colin asked.

"They've got something from the Phoenix at Control."

When they reached the radio room again, a different technician was on shift. He was intently watching an oscilloscope face on the board in front of him.

"What happened, did he answer?" the general asked.

"No, sir. But a few minutes ago we started getting a carrier wave on his transmission frequency."

Banning sighed disgustedly. "Is that all? Dammit!"

"What does that mean?" Colin asked.

"Not a damned thing," Banning said angrily. "He just threw the transmission switch, is all."

"Look, sir." The radioman pointed to the oscilloscope. The smooth sine of the carrier was slightly modulated now, uneven dips and jogs appearing rhythmically. "There's something coming through, but it's awfully damned faint, Sir."

"Run your sensitivity up," Banning ordered.

The radioman slowly twisted a knob, and the hiss-and-crackle coming through the speakers increased in volume until each snap was like a gunshot in the radio room. Colin winced at the noise.

"Maximum, sir."

"Increase your gain, then."

The technician did. The speakers were roaring now, filling the room. Very faintly behind the torrent of sound another sound could be heard, more regular. The rhythm corresponded with the jogging of the oscilloscope.

"That's it," Banning said. "But what the hell is it?"

"I don't—wait a minute," said Colin. "He's whistling! It's a tune."

"You recognize it?"

"No—no, it's vaguely familiar, but—"

"I know it, sir," the radioman said. "It's an old folksong, The Quaker's Wooing."

"Why is it so faint?" asked Colin.

"He must be a hell of a ways off-mike," said the tech. "Clear at the other end of the control room, I'd say."

"Turn down that damned noise," said Banning. The radioman twisted his controls back to medium range, and the thunderous hissing roar of the speakers died away.

"Well," said Banning, "nothing. We shoulda stood in bed."

"I'm not so sure," Colin answered. "After all, he did start to transmit, and that's more than we've had since he landed. I think we'd better keep it up."

"All right. Keep at it, sergeant."

"Yes, sir."

As Colin and Banning turned away, the psychiatrist heard the sergeant begin to sing softly to himself. Suddenly Colin stopped and turned back to the man.

"What'd you say?" he demanded.

"Nothing, sir."

"What you were singing, that song."

"Oh, it was the one the colonel was whistling, sir. It gets to running around in your head. I'm sorry, it won't happen again."

"No, I want to know what the words are. What you just said."

"Well, it goes, I mean it starts out, I can't remember the whole—"

"Come on, man! Sing it!"

In an uncertain voice the radioman began to sing:

"That's enough, sergeant," Colin said, relaxing. He turned to Banning. "Well, General, that's it. The wedge goes in a little deeper."

"What do you mean?"

"Is Harkins married?"

"Yes, yes, I think so. She lives in the officer's quarters on base."

"Get her," Colin said.

"Now? My God man, it isn't even five—"

"Get her," Colin repeated. "Harkins has her on his mind. Maybe we can get to him through her."

Martha Harkins was a small brunette, too plain ever to be called pretty. Almost mousy, Colin thought. But intelligent, and quick to understand the situation, in spite of her nervousness. She sat on the opposite side of Banning's desk, her hands folded quietly in her lap, fingers twined, while Colin explained what they wanted her to do. Her still-sleepy eyes were fixed on her fingers while the psychiatrist talked.

"I—I think I see," she said hesitantly. "What it comes down to is that you want me to try to talk Dick out of Phoenix I."

Colin nodded. "It may not be easy. I've told you as much as we know about the condition of his mind. He will not consciously hear you, in all likelihood. We hope to appeal to deep-seated emotions below the conscious level. Are you willing to try?"

"Of course," she said with real surprise, looking up at him for the first time.

"Good," Colin said warmly. He stood from behind the desk. "We'll take you over to radio, now."

Banning was waiting for them in Central Control.

"Any change?" Colin asked.

"No. Same thing. Sometimes he comes closer to the mike. We can hear his footsteps. He seems to be wandering around the control room pretty aimlessly. Or maybe he's just carrying on the in-flight routine, we can't tell."

"This is Mrs. Harkins," Colin said. "General Banning."

"Thank you for coming, Mrs. Harkins," the general said. "I hope this isn't too difficult for you." He took her small hand in his own.

Martha Harkins smiled faintly. "A service wife gets used to just about everything, general."

"Unfortunately true. If you'll come with me, I'll introduce you to your technician. Has Dr. Meany explained what we want you to do?"

"Yes, I think so."

"Good."

"Just one thing, Mrs. Harkins," Colin put in. "This may take some time. It may be we'll want you to cut a tape with a request to leave the ship, if we can't get any response from live voice. Repetition is the important thing, and the sound of your voice."

"All right. I'll do whatever you say." She turned away briefly, but not before Colin saw the beginnings of tears in her eyes.

Banning led her over to the radio console, saw her seated and instructed in the use of the equipment, and returned to Colin.

"What do you think?" he said.

"She'll do."

"Will it work?"

"How the hell do I know?" the psychiatrist answered roughly.

They were silent for a moment, watching the small figure of the woman leaning forward tensely over the microphone, as if by her nearness she might make her husband hear.

"You know," Banning said musingly, "I get the feeling this is all the fault of SpaServ, somehow. Some little thing we overlooked. A little more training, maybe."

The woman's soft voice droned on, not quite carrying distinctly to the two men, though the warmth and urgency of it was evident in her tone.

"I think you did all right with your training," Colin said finally. "He came back, didn't he?"

4.

Harkins slept only lightly, turning restlessly in the large control chair. Finally the pain of his headache increased to the point he could no longer sleep at all, even lightly. Just before he wakened, he thought he heard a sound at once intolerably loud and somehow soothing. Which was impossible, of course.

Opening the viewport shutter a crack, he found the land outside lit ambiguously by the false dawn that was beginning to spread against the eastern hills.

He took several more of the white pills for his headache. Briefly he considered eating something, but abandoned the idea. The pain was so intense, he didn't think he could keep anything down.

He found the illusion he had noted yesterday—the whispering sound he could not hear when he tried—was still there. It was even worse now.

All about him was the flickering shadow of a sound, demanding his attention, requesting. And still—when he tried to hear it, it was gone.

He pressed his knuckles against his forehead and clenched his eyes tightly shut.

If only he had something to do to take his mind off the headache and the elusive sound.... But there was nothing to do. With neither the Skipdrive nor the atomics operating, he had not even the routine powerchecks to keep him occupied.

Then why am I here?

His function was to operate the ship. That much he knew without doubt. And he was well suited to operate it. His hands were properly shaped to manipulate the controls, and he could do it automatically, without thinking about it. He was Ship-Operator.

But the ship was not operating....

What was his function then, when the ship was not operating?

The other control devices, when not controlling, automatically shut off. Perhaps something had gone wrong in his shut-off relay.

That was not it, either. He was not the same as the other controlling mechanisms. He was different. Different materials, different potential functions in his structure, all kinds of differences.

But even if it were true that he was not intended to switch off when not functioning as Ship-Operator, what was he to do?

Think it out. Think this thing out very carefully.

Pain was a signal of improper functioning. All right. He was not functioning properly, then, and he knew it because of the level of pain in his head. If he could get rid of the headache, he would at the same time be finding his proper function.

Step one, then: Get rid of the headache. And he had to do that anyway, because he was unable to think clearly while he had it.

The headache had alleviated several times, then come back again. That meant he had performed properly, then drifted away into—into—Wrong was the word that came to his mind. Wrong. He had drifted into improper functioning, and the word for that was Wrong, and his headache had come back as a result.

All right. When had the headache alleviated?

He tried to think back. The first time, the first time was when he had found himself speaking the meaningless words into the microphone, announcing his estimated time-to-destination. And then, when he had closed the viewports. And throwing that Receive switch....

What did these actions have in common? What factor did they share?

Only one thing. Two, really. First, they had some connection with the transmit-receive apparatus. Or two of the three did, at any rate. The other factor, shared by all three acts, was that they were done almost without his conscious will.

This, then, might be the critical factor. That he act without volition.

Relax. Completely. Allow yourself to act.

He leaned back in the control chair and tried to blank his mind, tried not to give his body any commands.

Without volition, without willing.

He closed his eyes.

For a long while there was nothing. Then he heard the whir of servomotors. He opened his eyes, delicately probed with his mind ... and the headache had lessened.

He glanced up at the console, to see what he had done. A red bulb glowed over the label AIRLOCK. He had thrown the airlock switch, then. And it had been the "proper function" for him, because the headache had lessened. But the out-of-range whispering had not diminished.

The airlock? He shook his head in puzzlement. But the technique seemed to be working. What now?

He closed his eyes again, and this time the delay was shorter. He knew before he looked what had happened. He had lowered the landing ladder.

Well, this began to be obvious. He was to leave the ship.

And yet, the headache had been worst when he had left the ship. What did that mean? It seemed to mean leaving the ship was a Wrong function. But it was certainly indicated this time, from his opening of the airlock and lowering the ladder.

Well, what was Wrong function at one time might well be Right function another time. That could happen.

Leave the ship....

There was an edge of pleasantness and warmth to that thought, and the headache diminished.

"Please leave the ship, Dick...." It was almost as if he could hear a warmth in the air saying that to him.

Try the alternative. Deliberately he thought: Stay in the ship.

A flash of pain soared up the back of his head and across the top to settle swirling and agonizingly in his temples.

Leave the ship, he thought quickly, and the pain abated.

Clear enough.

He got to his feet and carefully made his way out of the control room down the catwalk toward the airlock that stood open and waiting to let him out of Phoenix I....

An excited non-com slammed open the door to the radio room and shouted, "The airlock's opening!"

Banning and Colin dashed to the broad window and stared out at the bulky shape of Phoenix I, resting monolithic on the landing pad. Banning took the proffered binoculars from the non-com, focussed them on the broad flank of the ship.

"It's open, all right," he said. "Here." He handed the binoculars to Colin.

After a long delay, the landing ladder slid down the side of the ship.

"I think he's going to come out."

"There he is."

"What's he doing?"

"Standing in the airlock, looking around. Now he's starting to come down. Now he's at the bottom of the ladder, looking around again.... Now he's walking this way."

"Give me the glasses," Banning said. He looked for a long moment, making sure the colonel's direction did not change. "Still coming this way," he said, putting the glasses carefully on the table by the window. He turned to look at the psychiatrist. "What now?"

Colin shrugged. "Get him."

"Sergeant!" Banning called. "Sergeant, take five men...."

The room in which they put him was comfortable and secure. Very secure. The bed was firmly welded to the wall, the table bolted to the floor. There was nothing movable or detachable in the room.

The three microphones picked up little but the shuffle of feet; cameras dutifully imprinted on film the image of a man pacing restlessly back and forth, examining the fixtures of the room without apparent anxiety or curiosity.

"No trouble at all," Banning answered Colin's question. "He didn't even see the patrol. Spray shot of Somnol in the arm and that was it."

"He doesn't seem particularly upset," Colin mused, watching the screen on which the lean figure of Colonel Harkins paced.

"Nervous," Banning said.

"Not as badly as the situation would warrant. I don't think it's getting through to him. He's apathetic."

"How did he react to seeing his wife?" Banning asked.

"Bewildered him. Gave him a hell of a headache."

"That all?"

"That's all."

"What now?"

Colin sighed. "Get through to him some way." He tamped tobacco in his pipe, his eyes still on the spyscreen. Harkins was now sitting on the bed, his hands immobile on his knees, staring straight ahead.

"How do you intend to do that?"

Colin reached for a pad of paper and began scribbling, talking as he wrote. "How are you feeding him?"

"Double door compartment. Put the food in, close the outside door, open the inside."

"Put this on his tray next time, will you?" Colin handed the general a slip of paper. On it was written a single sentence: Richard Harkins, I want to talk to you.

"All right," Banning said, reading it. "He's due for lunch in about an hour."

On the screen, Colin could see the light come on over the food compartment, and the microphones picked up the sound of a bell. Harkins, who had not moved from the bed since his initial examination of the cubicle, looked up. The inner door of the compartment opened, revealing a tray with several steaming dishes, a pitcher of milk and a pot of coffee on a self-warm pad.

Harkins stood up. He looked at the food, walked over to the tiny open door and picked up the tray. Calmly he carried it over to the table, sat down, unfolded the napkin and put it in his lap.

"My God," Banning whispered, "you'd think he'd eaten this way all his life."

"Apathetic," Colin said shortly. "He refuses to admit anything unusual."

"How the hell could he rationalize losing consciousness and waking up in a windowless room?"

Colin shrugged. "Brain's a funny thing," was his only comment. His eyes were fixed intently on the screen. Suddenly Harkins noticed the slip of paper tucked under the corner of one of the dishes.

Colin leaned forward, took his pipe out of his mouth.

Harkins withdrew the paper and looked at it. Even on the screen, Colin could see the writing, almost make out the words.

Harkins stared briefly at the paper, turned it over and looked at the other side in puzzlement. He rubbed the back of his neck and frowned.

Finally he gave a little shrug, put the message back on the tray and resumed eating.

Colin sat heavily back in his chair. He sighed.

"He didn't even see it," Banning said disgustedly.

"He saw the paper, not the message."

"Why?"

"Personal communication. It implies the existence of another communicating—entity. He won't admit it." Colin re-lit his pipe.

"Ah, hell!"

"I guess we'll have to take the direct approach," Colin said thoughtfully.

He lay relaxed on the bed in the little room, his eyes closed, his face calm and quiet. Pulse normal, temperature normal. Above and in the walls recorders and cameras purred almost silently with the bland indifference of omniscience.

Harkins.

Yes.

Can you hear me?

... no ... The strain of the question twisted the man's face into a grimace of pain.

Pause. Then:

You are Richard Harkins.

Yes.

Colonel....

Yes.

Can you hear me?

I.... No. Anxious contortion. All right. It's all right.

The man's face returned to relaxation.

How old are you?

Thirty-two.

Have you always been thirty-two?

...

Have you always been thirty-two?

... no ... Hesitantly.

You were once younger.

Yes.

You were once a child and grew to be a young man and grew to be thirty-two.

... yes ...

Why do you hesitate?

I don't understand all the words you say.

What words don't you understand?

Well—Man. The expression of pain and anxiety flitted across his relaxed features.

I will explain the words later. Don't worry about them now.

All right.

Richard Harkins, we are going to move back to a time when you were nineteen. You are nineteen years old. You are nineteen.

How old are you?

Nineteen.

What are you doing?

I—I'm a cadet, I—

What kind of cadet?

... SpaServ ...

All right, now we'll move ahead two years. You are twenty-one years old. Twenty-one. How old are you?

Gradually Colin brought Harkins forward in time, carefully, feeling his way gingerly along the dark corridors of his mind. He brought him through cadets, graduation, his marriage to Martha (touchy: gently, gently)—his service in the planetary fleet.

Then: a mysterious phrase; rumors—Phoenix Project.

—nobody seems to know. Something secret, but no telling. Everything's secret this year. Testing officers right and left and up and down. But nobody knows what for....

... card waiting for me at breakfast ...

Months of testing. Still nobody knows, but the rumors are running fast and heavy. Whole base preoccupied with the misty Phoenix Project. Secret construction hangar, security precautions to the point of absurdity....

... I'm it! ...

... it's faster-than-light drive, that's what Phoenix Project is. Faster-than-light. The big dream, the dream of the stars ...

Training. Slower through the two years of intensive training. This may be a critical phase. Two years, endless repetitive drill, drill practice drill drill drill.... Colin's forehead feels cool as he sits beside the bed. Perspiration. A glance at his watch shows him two hours since they began.

How did you take to this intensive training?

All right. It was all right. Dull, you know, but it was all right generally. After the first year it was pretty automatic. Conditioned response, I didn't have to think. If and when such and such happens, press this button, throw that switch. Automatic.

Automatic, Colin thought. That's why he came back then. Without volition, responding to given signals according to training.

... walking toward the ship. She's big and bulky, but we're friends by now. Now I'm climbing the ladder up to the lock ...

... listening to the count down ... two ... one ... fire! ...

Harkins grunted as the re-lived acceleration slammed him back in the control chair with a relentless and unabating pressure. He was silent for thirty seconds.

... blacked out, not long. Report in to Gila Base, launching successful. They acknowledge, give me course. I'm moving "up", at right angles to the plane of the ecliptic. Fastest way to get away from large mass bodies ...

Time then on atomic rockets, almost a full day. Colin brushed over this phase, which was routine. As far as he could tell, Harkins' duties had been designed principally to keep him from getting bored before it was time to cut in the Skipdrive, and this corresponded with what General Banning had told him.

As he approached the time of the Skip, he moved more slowly, taking in detail.

... three minute bell. The bell is a pretty sound. I am checking the controls again. Everything is fine. I am sitting down in the control chair with my hands relaxed over the ends of the arms. When my fingers brush against the buttons, they tingle, or seem to. We're all ready. There's the two minute bell ...

Pause.

One minute bell ...

Suddenly Harkins sat stiffly upright on the bed. His eyes snapped open, staring with fear and disbelief at something Colin could not see.

Oh, my God, he whispered.

What is it?

But there was no direct answer. Harkins repeated:

Oh, my God, my God, my God ...

What do you see? What is there?

Oh Jesus the stars the stars the stars God in heaven I can't Jesus make them go make them go make them go ...

His voice had risen almost to a scream, his eyes open wide and staring, his body rigid.

With a whimper, he clenched his eyes shut and fell back on the bed. He drew his knees slowly and jerkily up to his chest, as if resisting the movement, clasped his arms around his legs tightly.

He began to rock back and forth, gently, gently, as if immersed in water, his breath making an involuntary whining sound as it passed his constricted throat.

Move forward in time. Move ahead. You are coming out of the Skip. You are coming out of the Skip. You are returning to normal space.

Colin's voice was steady and calm over the high-pitched whines coming from the throat of the man on the bed. Suddenly his face relaxed. The eyes remained closed, but closed as if in sleep, rather than anguish. His arms and shoulder released their clenched grip around his knees.

Evenly, smoothly, his legs straightened on the bed, his feet digging into the covers and pushing them into a roll at the bottom. He finally lay as he had begun, stretched straight with his hands beside his thighs and his face relaxed. When he spoke, it was in a normal, almost conversational tone.

... belled out. I like the sound of that bell, it is relaxing. It's a good signal and I'm glad it happens that way. I stand up from the control chair and stretch. I have the strong notion something very pleasant has happened.

How do you feel? Do you feel strange?

No, I feel fine. Everything is fine. I check the instruments, and they show that a Skip has been completed. That's good. I don't—I don't—somehow I can't remember why I wanted to ...

His voice broke off, puzzled. Colin waited, and in a minute Harkins began to speak again.

... hear the sound of the Skipdrive. It comforts me. Funny, I don't remember ever hearing it before ...

Go back before. Go back. You hear the one minute bell. You can hear the one minute bell and you are ready to make your Skip. You are getting ready to make your Skip.

Harkins snapped upright again and repeated his actions. He shouted and screamed, his body was forced into the foetal position jerkily....

OH GOD THE STARS THE STARS THE STARS

Whimpering.

Go forward. You are returning to normal space....

I feel fine, everything is fine. I check the instruments ...

Go back....

There was no lessening.

Colin's shirt was slick on his body with sweat, his face looked old, older, his breath came in almost imperceptible quaverings, but his voice remained calm and assured, in violent and distinct contrast to the strain that showed plainly as age in his face—

Move ahead....

Move back....

Twenty-three minutes later, Colin closed his eyes and said:

In ten minutes from this time you will waken feeling refreshed and relaxed, as after a good sleep. You will be alert and fresh when you waken. You will feel as if you have just had a pleasant nap. You will remember nothing of what has happened while you were asleep, but you will feel fresh and relaxed when you waken ten minutes from this time.

He finished the waking-formula mechanically and left the little room. He walked slowly and deliberately to his quarters on the base, as though holding himself rigidly in control. He did not answer Banning's excited questions except to say, "I can't talk about it now."

Reaching his room he fell full length on the bed and was asleep nearly before the swaying of the bed had quieted.

5.

Several hours later he was again in General Banning's office.

"Look," Banning said, "I'm sorry to press this, and I know you took a hell of a beating in there. But we've got to know."

Colin nodded morosely. "I know. I'm sorry about the delay."

"You looked more dead than alive when you came out."

"I'm afraid I'm too long on empathy and too short on objectivity to fool with that kind of thing. One of the reasons I don't often trigger these big discharges in my own practice. I get—inside, I guess, somehow. No detachment, or not enough."

"What was there? Inside, if that's the way you want to put it."

Colin sighed, absently pulled his pipe from his jacket pocket. "Specifically, I don't think I can tell you. He saw—or experienced as seeing—something when he went into the Skip. It was something so damned big it stripped him of his orientation as a human being."

"The films show him assuming a foetal position. That what you mean?"

"Well—basically this kind of regression is a denial of responsibility. 'I'm not a man,' he says. 'I'm just an unborn child. Take care of me.' The individual wants no part of the problems and responsibilities of adulthood. Harkins came out of that, or he never could have got the ship back. But he couldn't face being a man. The only way he could carry out his responsibilities, and survive, was to abolish the category, man."

Colin leaned back and sighed. "You know," he said thoughtfully, "Harkins must be the loneliest human being that ever lived. God!"

After a moment he looked up. "Ever read any Emerson?"

"The philosopher Emerson? No, not much. Some maybe, when I was in college. Why?"

"Nothing in particular. I was just thinking of an essay of his on Nature."

"No, haven't read it. Well," he continued, standing, "where do we go from here?"

"More of the same, I'm afraid. We have to find out what he saw. What was so—immense, that it could make a man deny the existence of other men."

Night came to Gila Base IV; the second night after the Phoenix I's landing. Darkness climbed out of the eastern hills and spread itself upward into the sky and across the plane of the desert. Phoenix I was still on the landing pad, but its sides were hidden by a webwork of gantries and scaffolding as base technicians clambered over it, testing, checking, examining.

Colin insisted on leaving the base, making the twenty-mile drive into town and his home. Banning was too tired to argue about it. He gave the psychiatrist a security gate-pass and went to bed in his own office.

Colin's car buzzed down the wide concrete toward the little cluster of lights that marked Gila City. He slowed when he reached the outskirts, watching the blue glare of the overhead sodium lamps slide along the hood and up over the windshield.

Reaching his apartment, he flicked on the lights and went in. It was a single room, two walls covered with floor-to-ceiling bookcases; there was a desk, one overstuffed chair. Automatically his eyes swept the room with the questioning glance of a man returning home; they lingered apprehensively on the neat stack of unopened mail the cleaning woman had put on the exact corner of the desk. He sighed. No matter how preoccupied a man got, the rest of the world went on just the same.

He went into the little kitchenette and made himself a cup of instant coffee, returned to the main room stirring it absently. He seated himself heavily in the overstuffed chair.

Struck by a sudden thought, he put the coffee down on the edge of his desk and went over to one book-wall. He scanned the multi-colored spines until he found the thin paperback he was looking for. He took it down and went back to the chair. "Nature," the cover said, "by Ralph Waldo Emerson."

Laying the little pamphlet open in his lap, he pulled pipe and tobacco out of his jacket pocket, tamped the bowl full and lit it. He shifted himself easily in the chair, settling himself.

Our Age is retrospective, the introduction began. It builds the sepulchers of the fathers....

He read on, gliding over the familiar words with a pleasant sense of acquaintanceship, the sense of sharing an idea with a respected friend.

To go into solitude, a man needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society. I am not solitary whilst I read and write, though nobody is with me.

The next line of the essay made him sit up straight in the chair. He read it over twice, then closed the pamphlet and carefully put it back in the bookcase with a vague feeling of having been either betrayed or helped, he couldn't tell which.

As he was turning out the lights to go to bed, his com buzzed. Answering it, he recognized the voice of Banning's secretary.

"Mr. Meany, can you get back to the base right away? Something's happened."

"What is it?" Colin snapped.

"The Colonel has gotten back into Phoenix I."

"... understand exactly how it happened," Banning said. "He seemed to be sleeping peacefully, and one of the men went in the room to take out his garbage, for Christ's sake. When the door opened, he made a dash for it."

The two men stood in the control room before the wide window-wall looking out on the landing pad. Phoenix I, still surrounded by scaffolding, was brightly lit in the glaring beams of a dozen searchlights playing from the Gila Base buildings and trucks on the field.

"Can he take it off?" Colin asked.

"I don't think so," Banning said. "Sergeant, is there fuel in those tanks?"

"Yes, sir," said one of the men in the group that crowded in front of the window. "But the feed valve is off. It can't get into the firing chambers."

"What would happen if he tried?" Colin asked.

"Nothing," Banning said. "It wouldn't fire. Unless—unless he didn't pay any attention to the board, and left his hotpoints on after he saw it wouldn't fire."

"What are hotpoints?"

"The ignition elements. They'd melt down under continuous heating and—well, then we wouldn't have any more problem. The tanks would go."

"You'd better clear the field," Colin said quietly after a minute. "Sergeant," he said to the radioman, "would you give the Phoenix a 'message coming' beep?"

The radioman did, then said to Colin, "Go ahead."

"Is he receiving?"

"Yes, sir."

"Colonel Harkins," Colin said. "Colonel Harkins, can you hear me?"

The loudspeakers buzzed.

"Colonel Harkins, please reply."

The speakers snapped once. The sound of Harkins' whistle came over, loud at first, then drifting away. He was whistling the same tune as before.

"... had a true wife but I left her, oh, oh, oh, oh ..."

"Do you want her back again?" Banning asked, recognizing the melody.

"Colonel Harkins, please reply," Colin said. Switching the mike off, he turned to Banning. "Better get her," he said. "We may have to go through the whole thing again."

It took twelve minutes by the control clock before they heard the door of the room open, and the light tapping of Martha Harkins' feet. Banning and Colin turned away from the window to greet her.

Suddenly their shadows were thrown violently ahead of them, leaping across the floor and up the opposite wall like frightened animals trying to escape.

They swung back to the window, their words of greeting still unspoken. For perhaps a half second they could make out the upper part of Phoenix I, standing above the ugly glare like the nose of a whale thrusting up through a sea of boiling flame. Then it disappeared, and the fire-ball climbed suddenly into the night sky, rolling and twisting in on itself. A gantry tipped and fell out of the flame with ponderous slowness, twisted and melted before it crashed to the pad. Then the unbearable glare died, and the searchlights played on an opaque black column of smoke, redly lit from within, standing where Phoenix I had stood.

The roar that shook the building seemed to come much too late.

Colin slumped disconsolately in the control room, staring blankly out at the clusters of beetle-like trucks clustered around the landing pad, with their feathery antennae caressing the stack of still-burning wreckage. Washed down by the foam trucks, the fire would soon be out. But there would be little advantage to it, except to clear the pad.

"How's Mrs. Harkins?" he asked without turning as he heard footsteps behind him.

"Under sedation," General Banning said. He came to stand beside the psychiatrist, looked with him at the firecrew's activity, so disorganized and insect-like at a distance.

"They'll have it out pretty soon," he said unnecessarily.

"Mm."

Both men were silent. After a while, Colin tamped in fresh tobacco and lit his pipe, sending up cottony puffs of smoke.

"What do we do now?" he said absently.

General Banning sighed.

"See that hangar?" he asked, gesturing to a tall building perhaps a quarter mile away down the edge of the field.

Colin nodded.

"Phoenix II," the General said, and his voice was flat and expressionless.

"Send another man into it, knowing no more than we know?"

"We have to know," Banning said. "Men have died before without as good reason."

"I'm going home. Call me if you need me."

Colin stood, and the general made a silent gesture of helplessness. They wouldn't need him. Not until Phoenix II came home. Then they would need him.

Colin spoke, quietly, as if thinking of something else.

"I didn't hear you," Banning said.

"Quoting Emerson. The essay on Nature I mentioned."

"What did he say?"

"'But if a man would be alone,'" Colin quoted, "'let him look at the stars.' Good night, General."

"Good night."

Colin walked outside into the cold desert air. The night was clear and crisp, and the Milky Way hurled itself like a mass of vapor across the sky.

... if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars ...

He looked up, and was alone in the night.