The King. Colonel-in-Chief.

I regard it as a high privilege to be associated with this book, which has been written by an old officer of the Regiment. I can fully appreciate the magnitude of the task which confronted him when he undertook to examine innumerable documents relating to hundreds of thousands of men and covering a period of several years, and select therefrom all that particularly concerned the Regiment.

I often think that an officer who finds himself in command of a battalion of Grenadiers on active service must be nicely poised between the weight of responsibility and the upholding power of tradition. At first the former seems to be overwhelming, but in time the feeling of confidence and trust in all ranks of the Regiment is so great that the idea of failure can be eliminated.

I think this history will make my meaning clear. As Time marches on with its many inventions, it does not become easier to uphold the traditions so nobly set by our forbears. Gas and high explosives take heavier toll of brave men than the weapons of old, and yet it is still the solid determination of the man that wins the fight, whether offensive or defensive. Although the tale of our great Dead is a long viiione, and thousands have been maimed in the struggle, the Regiment has borne its part in a manner worthy of it, and in accordance with the parting words of trust of our Sovereign and Colonel-in-Chief.

CAVAN,

Lieut.-General.

This account of the part taken by the Grenadier Guards in the European War is, substantially, the work of the officers of the Regiment themselves. Letters and diaries full of interesting detail have been sent to me, and a vast amount of information collected by Colonel Sir H. Streatfeild at the Regimental Orderly Room has been placed at my disposal.

The military historian who writes of past centuries has in some ways an easier task than one who attempts to put contemporary events into their historical perspective. In the first place, with every desire to be accurate, the latter finds that the accounts of eye-witnesses differ so much that he is forced to form his own conclusions, and to adopt what, according to his judgment, is the most probable version. In the second place, after reading a private letter giving a graphic account of a particular part of a battle, he may easily derive a totally false impression of the whole. Moreover, he writes in the constant presence of the criticism of eye-witnesses.

A special difficulty also arises from the unequal quality of the material placed at his disposal. There is sometimes a wealth of information on unimportant incidents and no material for the xhistory of important or dramatic events, in which the principal actors were almost invariably killed. Even the Battalion diaries, which were kept with meticulous accuracy during the early days of the war, contain less and less material as the fighting became more and more serious.

With a war of such astounding magnitude, when millions of men are fighting on a front of hundreds of miles, any attempt to give an intelligible picture of what is going on in a modern battle becomes practically impossible. Even if such a course were desirable in a regimental history, the material supplied, which consists for the most part of letters and diaries of regimental officers, would be totally inadequate, since regimental officers know little of what is going on except in their immediate neighbourhood. A tactical study was out of the question, since a battalion plays such a small part in modern battles, and to describe the movements of corps and armies appeared to be beyond the scope of a regimental history.

I therefore decided to depart from tradition, and to write a narrative giving, as far as I was able, details about companies, and even platoons. It seemed to me that this was what the officers themselves would prefer.

The absence of information concerning the German Army necessarily takes some of the life and colour out of such a record as this. In all military histories the account of the enemy's movements adds enormously to the interest of the narrative; but at present, beyond a few accounts from neutral journalists inspired by the Germans, xithere is no authentic information as to the movements of the German Army, and the motives which actuated the German General Staff can only be inferred.

Time will of course rectify this, and after the war detailed accounts of the German Army will be available, though it will inevitably be some years before anything worth reading about the enemy can be published. It has therefore been suggested that it might be best to defer the publication of this history for some years. But it is doubtful whether with the lapse of time any valuable additions could be made to a regimental history, though for a national history some knowledge of the enemy's plans will be essential.

The long periods of monotonous trench life, in which practically the same incidents recur daily, have been particularly difficult to deal with; and, although the greatest care has been taken to chronicle every event of importance, I am conscious that many acts of bravery and devotion to duty which have been omitted in the letters and diaries must go unrecorded.

The terrible list of casualties has made it impossible to do more than simply record the deaths of the officers of the Regiment who fell during the war. Had more space been available, fuller accounts of the circumstances under which they met their deaths and some personal appreciation of each officer would have been possible, but in a history which has necessarily to be restricted to three volumes, all this was out of the question.

The Regiment is indebted to Colonel Sir H. xiiStreatfeild, not only for the scrupulous care with which he gathered together information from every possible source, but also for his foresight in realising in the early stages of the war the importance of all documents connected with the movements of the different battalions.

The maps are the work of Mr. Emery Walker, who has succeeded in producing not only artistic pictures in the style that was prevalent among cartographers of the seventeenth century, but also perfectly clear and accurate maps. To Sergeant West I am indebted for the military detail.

To many officers I am indebted for suggestions, especially to Lieut.-General the Earl of Cavan and Major-General Jeffreys, who found time, during their few days' leave, to make many interesting additions to this history; and to Major H. L. Aubrey-Fletcher, whose knowledge and experience both as a staff and regimental officer have been invaluable.

In conclusion, I wish to take this opportunity of thanking Captain G. R. Westmacott, Lieutenant M. H. Macmillan, Lieutenant B. Samuelson, Lieutenant L. R. Abel-Smith, and Lieutenant A. C. Knollys for the excellent work they did in preparing accurate diaries for each battalion, with extracts from the officers' letters. Without their aid I should never have had the time or the energy to complete this book.

F. E. G. PONSONBY.

CHAPTER I

The Situation before the War 1

CHAPTER II

Arrival of the 2nd Battalion in France 9

CHAPTER III

The Retreat from Mons (2nd Battalion) 23

CHAPTER IV

The Battle of the Marne (2nd Battalion) 42

CHAPTER V

The Passage of the Aisne (2nd Battalion) 54

CHAPTER VI

The First Battle of Ypres (1st Battalion) 83

xivCHAPTER VII

The First Battle of Ypres (2nd Battalion) 143

CHAPTER VIII

November 1914 to March 1915 (1st Battalion) 187

CHAPTER IX

November 1914 to March 1915 (2nd Battalion) 201

CHAPTER X

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (1st Battalion) 224

CHAPTER XI

The Battle of Festubert (1st and 2nd Battalions) 247

CHAPTER XII

May to September 1915 (1st Battalion) 264

CHAPTER XIII

May to September 1915 (2nd Battalion) 272

CHAPTER XIV

Formation of the Guards Division 283

xvCHAPTER XV

The Battle of Loos (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Battalions) 290

CHAPTER XVI

October to December 1915 (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Battalions) 322

CHAPTER XVII

January 1 to September 1, 1916 (1st and 2nd Batts.) 352

The King, Colonel-in-Chief Frontispiece

Lieutenant-Colonel W. R. A. Smith, C.M.G., Commanding 2nd Battalion 144

Lieutenant-Colonel L. R. Fisher-Rowe, Commanding 1st Battalion 198

Officers of the Second Battalion Grenadier Guards 276

Colonel Sir Henry Streatfeild, K.C.V.O., Commanding the Regiment 288

Route of the Second Battalion, 1914, and the Mons Area, 1914 16

Route taken by the Second Battalion Grenadier Guards during the Retreat from Mons, and subsequent advance to the Marne and the Aisne, 1914 24

Sketch plan of Landrecies, August 25, 1914 28

Engagement at Villers-Cotterêts, September 1, 1914 34

Battle of the Marne—Position of the British Army on September 8, 1914 46

The Passage of the Aisne, September 14, 1914 58

Ypres and the neighbouring country where the First Battle of Ypres was fought, October and November 1914 84

xviiiRoute taken by the First Battalion Grenadier Guards through Belgium in October 1914 90

The Grenadier Guards at Ypres 142

Battle of Neuve Chapelle, March 11, 1915 226

Neuve Chapelle, March 12, 1915 235

Neuve Chapelle, March 13, 1915 241

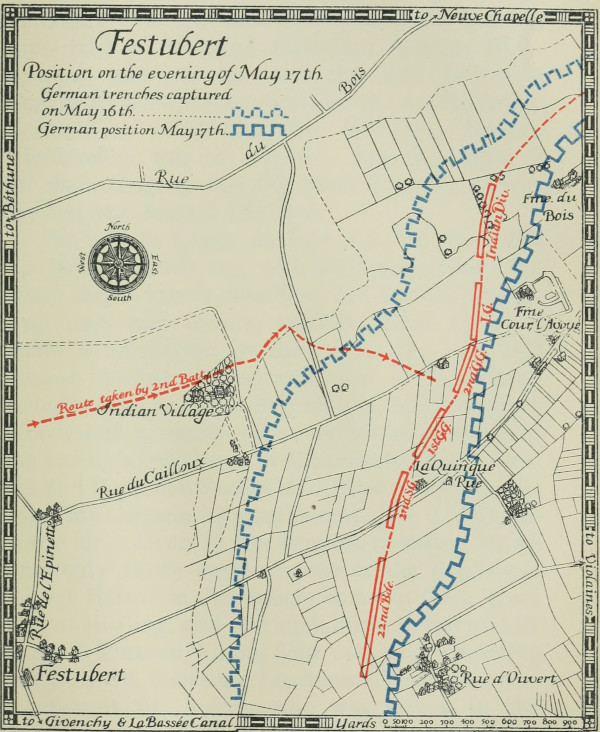

Festubert—Position on the evening of May 17, 1915 248

Battle of Loos, September 26, 1915 298

When the Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated at Sarajevo in Serbia on June 28, 1914, it never for a moment occurred to any one in this country that the crime could in any way affect the destinies of the First or Grenadier Regiment of Footguards. No one dreamed that, before another year had passed, not only would the three Battalions be fighting in a European war, but there would even be a 4th Battalion at the front, in addition to a 5th Reserve Battalion of almost unwieldy proportions.

Even when Austria began to show her teeth, it still seemed an "incident" quite beyond our horizon. If Austria and Serbia did come to blows, Great Britain was not even indirectly involved, and the British Army, therefore, remained unmoved. The Balkan peoples were constantly in a state of warlike commotion, but their troubles hardly affected the great British Empire. The war clouds, that from time to time darkened the European sky, had hitherto always been dispersed. More than once of late years the German Emperor had rattled his sword 2in the scabbard, and talked or telegraphed to the very limits of indiscretion, but nothing had ever come of it, nor did it seem at all probable that the assassination of an Austrian Archduke could be made the pretext for a European conflagration.

There were, however, certain elements of danger in the European situation at this particular juncture. The creation of the Triple Alliance—Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy—had made necessary some counter-move by the other European Powers. And the entente between England and France, initiated by King Edward, and originally intended merely for the settlement of outstanding differences between the two countries, became eventually the basis of a second grouping of nations. This entente was followed by one between England and Russia; and although in neither was there anything in the nature of a defensive alliance, it was well known that there was in existence—though the exact terms of it had never been made public—a far stronger agreement between France and Russia.

Meanwhile it was generally known that, all the time these several ententes were being formed, Germany had been steadily preparing for war. For forty years, with characteristic thoroughness of method, the Germans had been diligently organising their forces to this end. Not only had the Army been perfected into a first-class fighting machine, but the civil population had all been assigned the parts they were to play in the coming campaign. Trade problems had been 3handled, not so much with a view to commercial prosperity pure and simple, as to ensure to Germany a sufficient supply of the commodities which would be needed in a great war. Gigantic preparations had been made for a limitless output of shells and ammunition, and plans carefully elaborated for the conversion of factories of all kinds into workshops for war material. The whole State Railway system was controlled in such a way that, on the declaration of war, troops could be instantly concentrated at any selected spot with the utmost speed.

While many civilians saw and deprecated the arrogance and madness of such a policy, the military element, supported by the Emperor, was anxiously pressing for an opportunity of proving to the world the efficiency of the organisation it had created. It was only to be expected that the generals, who knew how vastly superior the German Army was to any other continental army, should hanker for an opportunity of showing off their perfect war-machine.

The attitude of the bankers and merchants towards the war was not clear. Originally, without doubt, they had favoured the insinuating methods of peaceful penetration, which had been so successful in the past, and by which they intended to dominate Europe, but just before the war they appear to have been allured by the prospect of large indemnities from France and Russia and to have withdrawn their opposition. They were persuaded by the military party that by war, and by war alone, could the domination of the world by Germany be 4achieved, and that now was the time to realise their dream. Young officers of both services made no secret of their wish for war, and constantly drank "to the Day" when they met at mess. The more intelligent portion of the German population quieted what conscience they had with the comfortable reflection that all military and naval preparations were merely ordinary precautions for defence. Indeed this theory, cunningly instilled into the German people by the military party, was so generally accepted that even after the war was declared the majority was under the delusion that it was fighting only for the defence of the Fatherland.

Although the attitude of Germany towards England did not play any prominent part in the events which led up to the war, there undoubtedly existed in Germany a deep hatred of this country. Commercial rivalry and the desire of the Germans to found a Colonial Empire on the same lines as ours would hardly account for this feeling, which permeated every class, and it is to the Flotte Verein or Navy League that we must look if we wish to find the reason. Originally instituted to instil into the youth of Germany a desire for sea power, this organisation, by means of propaganda, speeches, and pamphlets, succeeded in convincing the rising generation that we were their natural enemies. The arguments were invariably pointed by reference to the British Fleet, which, it was said, could dominate Germany's world policy, and so young Germans grew up with a feeling of terror for the British Fleet and hatred for the British nation.

5In spite of everything, England slumbered on, hypnotised by politicians who had convinced themselves by a process of mental gymnastics that war was an impossibility. The contingency of a British Army being sent to France was never even discussed by the House of Commons, and the logical outcome of our European policy appears never to have occurred to either House of Parliament.

While Germany was studiously preparing for war, we were engaged in academic discussions on disarmament, and although members of the Imperial Defence Committee and a limited number of Cabinet Ministers may have known of the possibility of our having to send an expeditionary force to France, the man in the street, and even the majority of members of Parliament, were completely in the dark as to the true significance of the position of affairs in Europe.

The whole situation was singularly favourable to the Germans. Never before had they been so strong, and probably never again would they have such a powerful Fleet and Army. For some years it had been growing clear to them that if ever they were to strike, they must strike soon. The Socialists were becoming stronger every day, and there were constant grumblings, which ever-increasing prosperity failed to stifle, at the enormous expenditure on armaments. The nation might weaken as the years went on, and there was every probability that the Government would find it impossible to maintain indefinitely a huge Army and a huge Fleet. If they failed to take advantage of this opportunity 6they might never again be in a position to dominate Europe.

Though Austria had long been tied to the wheels of the German chariot, there was always the danger of the Hungarians and Bohemians refusing to support Germany, should the quarrel be purely German. It was therefore necessary to make the casus belli essentially Austrian. What better opportunity could ever offer itself than the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne? Moreover, the new heir, perhaps soon to be the new Emperor, might not be willing to endorse all his predecessor's pledges, and Austria might conceivably drift apart from her ally. Clearly, therefore, if Germany, with Austria's help, was to strike a blow at Russia and France, she must do so forthwith.

The war party held that together Germany and Austria were more than a match for France and Russia. Italy was a member of the Triple Alliance, and would either come in on their side or remain neutral. Great Britain, it imagined, would be unable to take any part owing to her internal troubles. It appears to have taken it for granted that the Dominions and Colonies would in any case seize the occasion for declaring their independence, and that there would certainly be a second mutiny in India. There was therefore no need to consider the British Empire in calculating the chances of success. A parade march to Paris would settle France in a short time, and then the whole forces of the two Empires would be turned on Russia. A glorious and victorious peace would be signed before the end of the year.

7With such calculations as these, it is hardly to be wondered at that the rulers of Germany decided on war at once. To their dismay, however, Serbia submitted to the terms dictated by Austria, and it seemed at one moment that the whole incident would be closed. Acting on Russia's advice, Serbia agreed to all the points in the Austrian memorandum but two. These practically threatened her independence, but there was nothing that could not be satisfactorily settled by an impartial tribunal. But, as despatches and telegrams were exchanged between the European Powers, it gradually became clear that the original dispute between Austria and Serbia had now nothing to do with the matter. Sir Edward Grey made a final attempt to avert war by proposing a conference, but this proposal came to naught, and the determination on the part of Germany to force a war appeared to be stronger than ever. However sincere the Emperor's wish for peace may have been, he was powerless in the hands of a military autocracy which he himself had created. Ever since he had ascended the throne, he had set the military over the civilian element, and now, finding himself powerless to resist the demands of the war party, he determined to place himself at their head.

On July 31 Germany despatched an ultimatum to Russia demanding immediate demobilisation. This was tantamount to a declaration of war, but war was not actually declared till the next day. The declaration of war with France followed as a natural sequence.

Such was the situation at the beginning of 8August. With disinterested detachment the British Empire watched the preliminary negotiations, and even when war was declared between the two groups of Powers, public opinion was divided as to which course we should adopt. When, however, Germany violated the neutrality of Belgium, all doubt was removed, and we declared war on August 4. The whole Empire was stirred to the depths, and in London huge crowds paraded the streets and assembled outside Buckingham Palace to cheer the King and the Queen. The wildest rumours were circulated and believed. Fantastic tales were told to every one in confidence by well-informed men in the street, and eagerly swallowed by excited dupes.

Then the curtain was pulled down, and the British public was allowed to know nothing. What troops were going, where they were going, when they were going, all became matters of conjecture.

Meanwhile, silently and surely, the British Expeditionary Force found its way over to France.

To any neutral not completely blinded by German sympathies it must have been only too palpable that the last thing we were prepared for was a European war, for not only had we no men to speak of, but there appeared to be no competent organisation for dealing with a levée en masse. Relying on the warlike instinct of our race, we had clung tenaciously to the voluntary system, under the impression that it was best suited to our needs. Even if conscription had been politically possible, it was out of the question, since we had neither rifles, clothing, nor barrack accommodation. The Territorial Associations, which were expected to cope with the masses of men who at once began to flock to the colours, were found so inadequate that Lord Kitchener decided to improvise an entirely new organisation.

In the inevitable confusion which occurred after the declaration of war, there were, however, two factors which stood the test successfully, and which may be said to have saved the country from disaster in the initial stages of the war. The first was the equipment and despatch of 10the Expeditionary Force, which was perfect in every detail, and the second was the assembly of the Territorial Forces, originally designed to repel invasion, but now utilised to garrison India and the Colonies.

When war was declared, the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards was at Wellington Barracks, the rest of the Expeditionary Force being mostly at Aldershot. The speed with which the Battalion was mobilised reflected the greatest credit on all concerned. Its equipment was all ready; reservists arrived from all parts of the country with a promptitude that was truly remarkable. It was on August 4 that mobilisation orders were received, and the Battalion was soon ready to start on active service.

Meantime, while the preparations were still in progress, there occurred an unrehearsed little incident, typical in its way of the unspectacular, practical side of modern war. As the 2nd Battalion was returning to Wellington Barracks from a route march, the King and Queen came down to the gates of Buckingham Palace, quite informally, to see the troops pass by. There was neither pageantry nor gorgeous uniforms, but those who were privileged to be present on the occasion will not easily forget the business-like body of men of splendid physique, clad in dull khaki, who marched past in fours, and saluted the King, their Colonel-in-Chief, as they returned to barracks.

The start for France was made on August 12. The First Army Corps, under the command of General Sir Douglas Haig, consisted of:

The Second Army Corps, under General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, consisted of the Third 12Division, under Major-General Hamilton, and the Fifth Division under Major-General Sir Charles Fergusson, Bart. (an old Grenadier).

The Roll of Officers, 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards, embarked for active service on the 12th of August

Lord Loch was appointed to the Staff after the Battalion landed in France, and Major Jeffreys took his place as senior Major on August 18.

Queen Alexandra came to see the Battalion off and wish it God-speed when it paraded at Chelsea Barracks that afternoon. With Her Majesty, to whom all the officers were presented, were Princess Victoria and Princess Beatrice. Headed by the band of the regiment, the Battalion then marched to Nine Elms and entrained for Southampton Docks, where it embarked on the Cawdor Castle, and finally sailed at 8 o'clock for France.

Strictest secrecy had been observed about its destination, and the captain of the ship himself did not know where he was bound for until she was actually under way. It was lucky that it was a lovely night and the sea quite calm, for the vessel was crowded to its utmost capacity. The following message from Lord Kitchener had been handed to each man when the Battalion embarked:

You are ordered abroad as a soldier of the King to help our French comrades against the invasion of a common enemy. You have to perform a task which will need your courage, your energy, your patience.

Remember that the conduct of the British Army depends on your individual conduct. It will be your duty, not only to set an example of discipline and 14perfect steadiness under fire, but also to maintain the most friendly relations with those whom you are helping in the struggle. The operations in which you are engaged will, for the most part, take place in a friendly country, and you can do your own country no better service than in showing yourself in France and Belgium in the true character of a British soldier.

Be invariably courteous, considerate, and kind. Never do anything likely to injure or destroy property, and always look upon looting as a disgraceful act. You are sure to meet with a welcome and to be trusted; your conduct must justify that welcome and that trust. Your duty cannot be done unless your health is sound. So keep constantly on your guard against any excesses. In this new experience you may find temptations in wine and women. You must entirely resist both temptations, and while treating women with perfect courtesy you should avoid any intimacy.

Do your duty bravely.

Fear God.

Honour the King.

Kitchener, Field-Marshal.

Next morning the ship was found to be nearing Havre, and the men were full of curiosity to see what manner of land France was. Meanwhile, from French fishing-boats and trawlers came loud cheers at the welcome sight of the arrival of the forces of Great Britain. A still more enthusiastic greeting awaited the Battalion when it landed, and marched through the numerous docks on the outskirts of the town to a camp about five miles away. The inhabitants crowded round the men, and threw flowers at them as they marched by, while from all sides came welcoming shouts of "Vive les Anglais," "Vive l'Angleterre," and "Eep-eep-ooray."

15When the 2nd Battalion arrived in France, the German Army had already overrun Belgium. For nearly ten days the Belgian Army had held up the Germans, but Liége had fallen, and there was nothing now to prevent the enemy from pouring into France. The French Army, as soon as it was mobilised, had begun a general offensive towards Alsace and Lorraine, but after some small successes had been checked at Morhange. A complete alteration in the French plan of campaign was rendered necessary by the advance of the German Army through Belgium, and troops were now being hurried up towards the North from every part of France.

The original disposition of the British Expeditionary Force was as follows: The Headquarters of the First Corps (the First and Second Divisions) under Sir Douglas Haig, at Wassigny; the Headquarters of the Second Corps (the Third and Fifth Divisions), under Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, at Nouvion; while the Cavalry Division, under General Allenby, was sent to Maubeuge.

It was a scorching, airless day, and the march to camp was a very trying one. But after a good sleep and a bathe in the sea the men were thoroughly refreshed and fit. Then, after the usual inspections, they were formed up on parade, and the King's message was read out to them:

Message from the King to the Troops of the Expeditionary Force

You are leaving home to fight for the safety and honour of my empire.

Belgium, whose Country we are pledged to defend, 16has been attacked and France is about to be invaded by the same powerful foe.

I have implicit confidence in you, my soldiers. Duty is your watchword, and I know your duty will be nobly done.

I shall follow your every movement with deepest interest and mark with eager satisfaction your daily progress, indeed your welfare will never be absent from my thoughts.

I pray God to bless you and guard you and bring you back victorious.

George R.I.

The whole population of Havre seemed to have come out to see the Battalion when it marched the same evening to the entraining point. The crowd cheered and shouted, and the men responded with "The Marseillaise." When they reached the siding the disappointing news met them that the train would not start for another four hours. It began to rain heavily, but fortunately there were large hangars available, into which the men crowded for shelter.

Eventually when the train arrived at 2 A.M., the men were packed into it, and very crowded they were. Sleep was difficult, as the horse-wagons attached to the train were loosely coupled, and there was a succession of bumps whenever the train stopped or slowed down. The first real stop was at Rouen, where provisions were obtained for the men, and then the train bumped on to Amiens.

Route of the Second Battalion, 1914

Fervent scenes of welcome went on all along the line. Each little wayside station, every bridge and level-crossing held a cheering throng. At Arras the Mayor turned out in state with a 17number of local magnates, and presented three large bouquets, for which Colonel Corry returned thanks on behalf of the officers, in his best French.

A touch of humour was not wanting at the little ceremony—if any one had been in the mood to seize hold of it. For, caught unawares, Colonel Corry, Lord Loch, and Lord Bernard Gordon-Lennox were anything but arrayed for a function, in fact, in a state of decided deshabille. But such was the enthusiasm of the inhabitants that a trifle like this passed unnoticed or unconsidered.

The stationmaster here said he was passing trains through at the rate of one every ten or fifteen minutes, which gives some idea of the great concentration of troops that was going on.

Slowly the train went on through Cambrai, Busigny, and Vaux Andigny to Flavigny, where, in pouring rain, the Battalion detrained and went into billets—surprisingly well arranged; but then Flavigny had plenty of experience in that way, and only a few days before had lodged the French troops.

Next morning parade was at 7 o'clock for the march to Grougis, about seven and a half miles off, where four days were spent in billets, and Colonel Corry took advantage of the breathing space to have his officers and men inoculated against typhoid.

The concentration of the British Force in the Busigny area was now completed, and the advance towards Mons was to begin the next day.

Off again on the 20th, the Battalion marched to Oisy (where it was again billeted), and on 18the following days to Maroilles and La Longueville. Here for the first time it heard the guns, and realised that very soon it would be getting to work.

On the 21st, following the plan concerted with General Joffre, Sir John French took up a defensive position from Condé on the west to Binche to the east—a front of about twenty-five miles. The British Army was thus on the extreme left of the French lines. To the First Corps was assigned the easterly position from Mons to Binche, while the Second Corps lined the canal from Mons to Condé, the whole front being covered by the 5th Cavalry Brigade.

Originally the scheme appears to have been to await the enemy's onslaught on the Charleroi—Mons line, and then to assume the offensive and advance into Belgium.

How far-reaching the German preparations had been was at that time hardly recognised, and neither the French nor the British Commander-in-Chief seems to have had any conception of the overwhelming force which the Germans had been able to concentrate against them.

From La Longueville the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers marched on August 23, during the last stages of its journey, across the field of Malplaquet, where more than 200 years before the regiment had fought with distinction, through Blaregnies and Genly to the outskirts of Mons, where it bivouacked. There it received orders to advance, which were countermanded before they could be carried out, and the Battalion was told to remain where it was. There was nothing to 19do but have breakfast and an hour's sleep by the roadside, with showers falling at intervals. All the time heavy firing could be heard from the direction of Mons, and shells bursting could be observed in the distance.

Orders then came for the Battalion to march back to Quevy le Petit, about five miles off, where the men fondly imagined they would again be comfortably billeted. But hardly had they arrived there when they were sent forward again. As they were marching down a dusty track General Scott-Kerr rode up, and directed the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers and the Irish Guards to move up close behind the ridge east of Spiennes in support of the Irish Rifles. At the same time the two Coldstream battalions were ordered to entrench themselves just east of Harveng, presumably as a precaution in case the Brigade should have to retire. Heavy firing was now going on all round, and the ridge which overlooked St. Symphorien to the north was being vigorously shelled by the Germans, who had got the range to a nicety, and were bursting their shells over it with accuracy. It was about 6 P.M. when the Battalion, advancing through Harveng, proceeded in artillery formation for about one and a half miles to the hill near Spiennes. The men huddled close together under the banks on the reverse slope of the hill just over the railway line, while bullets and shells whistled over their heads. As they were lying there they were amused to see the signalman walk slowly down the line as if nothing in particular was happening. He had to light the lamps, 20and saw no reason why the ordinary routine which he had carried out probably for many years should be interfered with. One of the officers called out to him in French, and explained that the Germans were advancing, but he merely murmured "ça m'est égal," and continued his work, apparently unconscious of the bullets that were striking the line.

Meanwhile, Colonel Corry and Major Jeffreys went up to the position occupied by the Irish Rifles, who were holding their own well under a heavy rifle fire.

When they returned to their men it was getting dark, and at 10.30 a message came from the O.C. Irish Rifles, that his battalion was retiring. It appeared therefore to Colonel Corry that the position was becoming untenable, since the Irish Rifles on his left had already retired, and both flanks of the Battalion were exposed. He consulted Colonel Morris of the Irish Guards, and they both came to the conclusion that the best course would be to retire to Harveng.

The difficulty was to communicate with the Brigadier. The telephone to Brigade Headquarters had been cut by shell-fire, and so Colonel Corry rode back to find General Scott-Kerr. He could not be discovered, and was reported to have gone to Divisional Headquarters. There seemed no prospect whatever of finding him, and it was now past midnight. Thereupon Colonel Corry determined to take upon himself the responsibility of ordering the retirement of the two battalions. His impression was that in a case like this, when local conditions could not be 21known to the Divisional Staff, it was for the man on the spot to make his own decision.

Superior authority, however, afterwards held that while under exceptional circumstances such powers might well be delegated to the man in mediis rebus, in a case like this it could not be admitted that an officer in actual touch with the enemy was the best judge of how long a position should be held. It was felt that there were many considerations in a decision of this sort, of which the officer in the front line could know very little. Colonel Corry was therefore severely blamed for his action, and was a fortnight later relieved of his command.

At 1 o'clock in the morning the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers and the Irish Guards retired, but they had only gone a couple of miles towards Harveng when they were ordered to go back and occupy the ridge they had just left. Back they went, and got as far as the foot of the hill, only to receive another order to retire to Harveng. By this time the men were absolutely tired out. They had started at 3.30 the previous morning, and had been on the move for twenty-four hours, with only occasional halts by the roadside.

It was just at this point in the engagement that Sir John French received what he described in his despatch as a most unexpected message. It came from General Joffre, who informed him that the French Forces had been compelled, by superior numbers, to retire, and that consequently the Fifth French Army, which was immediately on our right, had vacated its line. Two German corps were advancing on the British position, 22while a third corps was engaged in a turning movement in the direction of Tournai. Divisions of French Territorials had been promised in support of the left flank, but, except for a Brigade at Tournai, no French troops arrived from the west. There was therefore no alternative for Sir John French but to retire.

Thus began that historic, terrible, splendid retreat from Mons. Long weary marches were to be the lot of the British Army for many a day, but fortunately no one realised what lay ahead, or the stoutest hearts might well have quailed.

Long before it was over, the men's boots—not Crimean ones of brown paper, but good, sound English leather—had been worn into shreds by those interminable, pitiless paving-stones, that had withstood centuries of traffic. Even the men with the toughest skins suffered badly from their feet. Clouds of dust and the heavy atmosphere arising from men in close formation added to the trials of marching. Constant cries of "Feel your right" (to let cavalry or wagons pass by), the wearisome burden of the pack on the shoulders, which drove many men to throw away their most prized possessions, the frequent futile digging of trenches, abandoned as soon as they were dug, the orders and counter-orders—all made the days that followed a positive nightmare to the Army.

Such continuous retirement had never been practised. It was against all tradition, and the 24men grumbled constantly at the seemingly never-ending retreat. But what other course could the "contemptible little army" have followed in the face of the enemy's overwhelming force?

On the 24th Sir H. Smith-Dorrien started off with the Second Corps, while a demonstration was made by the First Corps in the direction of Binche, and dug a line four miles south of Mons to enable the First Corps to retire. It was evident that the Germans were straining every effort to surround the British Army, and therefore to hold on too long to any line was extremely dangerous. The Fifth French Army was still in full retirement, and the First French Cavalry Corps was so exhausted that General Sordet could promise no assistance. The greater part of the British Cavalry Division, with the exception of the regiments covering the retreat of the two British Corps, was guarding the left flank. The arrival of the Fourth Division at Le Cateau had been a welcome addition, but as it was only too probable that the Germans would make every effort to envelop the left of the whole line of the Allies, it was important to have strong reinforcements on that flank.

Route taken by the Second Batt. Grenadier Guards during the Retreat from Mons, and subsequent advance to the Marne and the Aisne. 1914.

Two hours' sleep was all the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers was allowed on that fateful 24th of August, weary as it was after its twenty-four hours on end of marching and fighting. At daybreak it marched to Quevy le Grand, where the men were ordered to dig themselves in. They were quite in the dark about what was going on round them. What force was opposed to them or why they were retiring, no one knew. The 25greatest secrecy prevailed. Although it was cold and foggy early, it soon became scorching hot and the men were tired, but when the word went round that this was not a rearguard action, but a determined stand, the digging became a serious matter, and they set to with a will. The Germans advanced very slowly and cautiously, gradually pushing back our Cavalry Patrols, who could be seen retiring. They shelled the Mons—Maubeuge Road and also Quevy le Grand, but as the line of the road was not held, our position being some hundreds of yards in rear of it, little damage was done, although a few men were hit in the village.

But at 2 P.M. another order came to evacuate the trenches and concentrate on the left. "Concentration" proved to be a euphemism for further retirement, and after a long and dusty march the Battalion bivouacked south of La Longueville.

Next morning at 5 o'clock it started on another hot and lengthy march through Pont sur Sambre, Leval, and Noyelles to Landrecies, which was reached at 4 P.M. It went into billets and settled down to rest. But soon afterwards a trooper from the cavalry patrols rode into the town with the news that the Germans were coming; the alarm was given, and the men stood to arms. Nothing further happened, however, and they returned to their billets. The 3rd Battalion Coldstream provided the outposts, and the rest of the brigade were just settling down once more in the hope of a restful night when a second alarm 26sounded. This time it was a real one. The Germans were advancing in force on Maroilles and Landrecies.

Though the night was very dark there was no confusion, as the men poured hurriedly out from their billets to fall in. Some were at once detailed to build emergency barricades in the streets, and as the tool limbers were taken for this purpose the Battalion never had any heavy tools for the rest of the retreat. The houses on the front of the town were rapidly put in a state of defence; loopholes were made, and the furniture, or anything handy, was pushed up to make the walls bullet-proof.

As it turned out, the enterprise of a small patrol of Uhlans, who rode unopposed into the town during the afternoon, had proved a very fortunate thing for the defenders. For it seems to have been assumed at first that the town was covered by troops from other brigades, and when the 3rd Battalion Coldstream was ordered to furnish outposts it had been considered a quite unnecessary precaution. After the Uhlan incursion, even the most optimistic could hardly have needed convincing.

When all the dispositions had been made the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers was distributed as follows: Nos. 2 and 3 Companies, under the command of Major Lord Bernard Lennox and Captain Stephen, held the level-crossing over the railway, and watched the right and left flanks of the road leading over the Sambre. No. 1 Company, under Major Hamilton, held the two sides on the left, while No. 4 Company, 27under Captain Colston, in reserve, was posted on the bridge over the Sambre.

The first warning that the enemy was at hand was given at 8 P.M. by the firing of the picquets. When the alarm went there was still sufficient light for the men to get into their positions, but soon after it became pitch dark, and the rain began to fall. Suddenly shadowy forms were observed by the outposts moving in the darkness. Evidently they realised that they had been seen, for a voice was heard calling out, "Don't shoot. We are the French." The trick at that time was new to us. Our men naturally hesitated at first to fire, and this gave the Germans their opportunity for a forward rush.

Very critical moments followed. The two forces were only a short distance apart, and in the darkness a retreat would have been fatal, but the splendid discipline of the Guards saved the situation. Everywhere the attacking Germans found themselves beating up against a wall of stubborn resistance. They brought up a couple of guns and poured shells into the town at almost point-blank range; they even fired case-shot down the road. Again and again they charged, only to be met and mowed down by a withering fire. The machine-guns of the Grenadiers were moved up to help the Coldstream, and came into action at a very critical moment. They were largely instrumental in repelling the enemy's attack, and were well handled by Lieutenant the Hon. W. Cecil, who was slightly wounded. Private Rule particularly distinguished himself by sticking to his gun and 28continuing to fight it, although he had been blown off his feet by the blast of a H.E. shell. The brunt of the attack was borne at the start by the 3rd Battalion Coldstream, which lost heavily in this fight; but in the Grenadiers the casualties were not great.

Soon burning houses were lighting up the battlefield, and it began to be possible to distinguish friend from foe. During one of the bursts of firing Lieutenant Vereker was hit, and fell shot through the head. After the first heavy attacks had been repulsed, the enemy tried to get round the left of the Coldstream in the direction of the railway-station, but there was met by a steady fire from No. 2 Company, under Major Lord Bernard Lennox, and could make no headway. Splendid work was done by a field howitzer, which had been manhandled up to the level-crossing, and which succeeded in silencing the enemy's guns.

Sketch plan of Landrecies.

Finally, about midnight, the enemy evidently realised the futility of going on with the attack, and retreated once more into the darkness. But spasmodic firing continued for some time, and it was not until nearly 2 A.M. that the night became still, and the men were able to strengthen their position. It was afterwards learnt that the Germans who took part in the attack had been pushed up to Landrecies in two hundred motor lorries. How severely they had been handled may be surmised from the fact that they allowed the Grenadiers and 3rd Battalion Coldstream to retire unmolested over a single bridge across the Sambre. Writing of this engagement 29in his despatch of September 7, Sir John French said:

The 4th Guards Brigade in Landrecies was heavily attacked by troops of the Ninth German Army Corps, who were coming through the forest on the north of the town. This brigade fought most gallantly and caused the enemy to suffer tremendous loss in issuing from the forest into the narrow streets of the town. This loss has been estimated from reliable sources at from 700 to 1000.

In the meantime the Second Corps was between Le Cateau and Caudry with the 19th Brigade, which had been brought up from the lines of communication on the left and the Fourth Division south of Cambrai. The German First Army launched a serious attack along the whole of this line, and Sir H. Smith-Dorrien, finding himself outnumbered and out-gunned, had the greatest difficulty in breaking off the engagement and continuing the retirement.

At daybreak the 4th Brigade again got orders to retire, and marched unmolested to Etreux. Unfortunately many of the men had no time to retrieve their kits, which they had left at their billets, and all these were left behind. The troops were dead beat, having again had practically no sleep after a long day's marching and fighting. Every time a halt was made the whole Battalion fell fast asleep, and when the march had to be resumed it was very hard to rouse the men. It might seem hardly worth while to sleep during a brief halt of only a few minutes, with the prospect of a painful reawakening to the realities of the situation as the 30inevitable sequel. But most of the men were so thoroughly worn out that they eagerly welcomed even the doubtful blessing of such a respite. In the distance heavy firing could be heard in the direction of Le Cateau, and at one time it seemed probable the 4th Brigade might be sent off to support the hard-pressed Second Corps.

Etreux was reached at last, and the Battalion proceeded to dig itself in. During the afternoon a German aeroplane flew very low over the bivouac, and dropped a bomb, which, however, did no damage. Every one who had a rifle handy had a shot at the unwelcome visitor; eventually it was forced down a mile away, where it was picked up by the cavalry. In it were found three officers, two dead and one wounded.

Another long dusty march lay before the Brigade on the following day. Continuing the retirement, it passed through Vénérolles, Tupigny, Vadencourt, and Hauteville to Mont d'Origny. A report was brought in that a large force of the enemy had been seen near St. Quentin, but this proved to be inaccurate. That night the First Corps was in a most critical position. The Germans had nearly surrounded them, and urgent orders to entrench the high ground north and east of Mont d'Origny were received; but although the weary troops dug on till midnight, nothing occurred, and at 3.30 A.M. the Battalion started off again.

It reached Deuillet near La Fère, where it had the only day's halt during the retreat. On the way the Scots Greys and 12th Lancers 31charged a large force of German cavalry and utterly routed them, making many prisoners, but otherwise nothing was seen of the enemy.

On arrival at Deuillet, the usual procedure was gone through, and a position in defence was entrenched, the men working at it all day.

In the evening an electrifying report, which cheered every one up, went round that there was to be a general advance. But when the order came it was the usual one to retire, and another hot march of twenty-eight miles followed. The weary, wearing ordeal of long day marches and but little sleep had commenced again. As soon as it was decided to continue the retreat, and the whole British Force had crossed over the Oise, the bridges were blown up. The heat was intense. There was practically no wind, and the dust was stifling; a very large number of men were suffering from sore feet, and there was a good deal of grumbling in the ranks at the endless marching in the wrong direction. But there was no prospect of a long rest, and those battalions which were unlucky enough to leave men behind never saw them again. Not a man from the 2nd Grenadiers, however, fell out.

The two corps which had been dangerously separated were now once more united, but the pursuing Germans were very near, and the situation still gave rise to much anxiety. Information was received to the effect that five or six German corps were pursuing the Fifth French Army, while at least two corps were advancing on the British Army. The situation on the left of the 32British Army was obscure, but it was reported that the enemy had three or four more corps endeavouring to creep round that flank. In response to Sir John French's representations, General Joffre ordered the Fifth French Army to attack the enemy on the Somme with the object of relieving the pressure on the British Army.

The Battalion reached Soissons about midday on the 30th, and was ordered to occupy the ridge near Pasly, about two miles north of the town. Next day it tramped on to Soucy, a very hard march in great heat, finishing up with a steep climb. Here it bivouacked as usual, and snatched what rest it could. But a full night's sleep was always out of the question, and soon after midnight the whole Brigade was directed to form a rearguard, to cover the retirement of the Second Division.

Accordingly trenches were dug in the high ground above Soucy, No. 4 Company Grenadiers being detached to guard the right flank in a position leading across a deep ravine to the high ground above Montgobert. It was to rejoin the Battalion when it retired to the forest of Villers-Cotterêts. Soon after the Germans came in sight, and retirement from the first position was successfully effected. The 2nd Battalion Grenadiers and 3rd Battalion Coldstream made their way into the wood, the edges of which were held by the Irish Guards and 2nd Battalion Coldstream, and took up a fresh position along the line of the main road running east and west through Rond de la Reine.

33Thick mist hung over the country, and the dense undergrowth made the passage of the wood difficult. The Germans, it was assumed, would not attempt to penetrate the wood, but would be content to use the roads and drives. The assumption proved to be wrong—fortunately for us. As it happened, they came through the very thickest part, and in so doing lost cohesion and direction. Probably, in fact, it was their doing this, and the confusion into which they were consequently thrown, that enabled the 4th Brigade to break off the action later in the evening and retire unmolested.

The 2nd Battalion Grenadiers held the right of the line. From a strategic point of view, the position it occupied could not well have been worse. But in a rearguard action there is often no choice. It was absolutely necessary to retard the advance of the enemy through the wood, so that the rest of the Division should get away.

During the time of waiting for the oncoming Germans, the Scots Greys and 12th Lancers suddenly appeared, coming down the ride on the right. They had been attracted by the firing, and came to see what was going on. They dismounted, and, finding many friends among the Grenadiers, started "coffee-housing" for a while. But the firing in the outskirts of the wood began to sound serious, and they rode off along the road to the left, with the idea of operating against the enemy's right.

A few minutes later the Germans appeared, and a fight at close quarters began. The firing became very hot, as in some places the opposing 34forces were hardly seventy yards apart. Good work was done by the machine-guns of the Grenadiers and Irish Guards, which accounted for a large number of Germans, while the men charged repeatedly with the bayonet and drove the enemy back. Gallantly, stolidly, the 4th Brigade held on until the order came to retire.

Even with highly-disciplined troops, a rear-guard action in a wood is one of the most difficult manoeuvres to carry out well. It is quite impossible for the commanding officer to keep a firm grip of his battalion when it is scattered about in different rides; orders passed along often do not reach all the platoons, and men of different companies, and even regiments, are wont to get hopelessly mixed. Fortunately in the Brigade of Guards the men are all trained on the same system, and, except for some small characteristic differences, a man belonging to one regiment will be quite at home in any of the others.

At Villers-Cotterêts the men of the 4th Brigade became very much mixed, and officers took command of the men who happened to be near them. The wood, too, was so thick that at fifty yards' distance parties were practically out of sight of each other. One result of this difficulty of keeping in touch was that two platoons of No. 4 Company never got the order to retire.

Engagement at Villers-Cotterêts. September 1. 1914.

These two platoons, under the command of Lieutenant the Hon. F. E. Needham and Lieutenant the Hon. J. N. Manners, were at the Cross Roads at Rond de la Reine. As the Germans 35came on, Brigadier-General Scott-Kerr, finding that they were creeping round his left flank, ordered these two platoons down a ride to the left, to enfilade them. Making the best dispositions they could, these two officers continued to fight, when they suddenly realised that they were cut off and the Germans were on all sides of them. True to the traditions of the Regiment, they stuck to their posts, and fought on till all were killed or wounded.

Lieutenant the Hon. J. N. Manners was killed while directing the fire of his platoon, and Lieutenant the Hon. F. Needham, badly wounded, was taken prisoner. Lieutenant G. E. Cecil, another officer belonging to these platoons, seeing the Germans streaming across a ride to his left, dashed off with some men to stop them. He had not gone far before he was shot through the hand; stumbling forward, he recovered his feet, and, drawing his sword, he called on the men to charge when a bullet struck him in the head. And there were other casualties among the officers. Earlier in the day the Adjutant of the Battalion, Lieutenant I. MacDougall, was shot dead while carrying orders to the firing-line. His place was taken by Captain E. J. L. Pike. The Brigadier-General, Scott-Kerr, who rode up to give some orders, was badly wounded in the thigh, and the command of the Brigade passed to Colonel Corry, while Major Jeffreys took over the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers. Field-Marshal Sir John French, on hearing of this, sent the following telegram to Brigadier-General Scott-Kerr, care of Communications:

36My warm congratulations on gallantry of your Brigade A A A am deeply grieved to hear you are wounded A A A I shall miss your valuable help very much A A A my best wishes for your recovery.

French.

Captain W. T. Payne-Gallwey, M.V.O., who was in charge of the machine-guns in the First Brigade, was reported missing.

Orders were given to retire, and the Battalion quietly withdrew in single file of half-platoons, covered by a rear party from No. 2 Company. The enemy, as already stated, had been thrown into hopeless confusion in the wood, and, in spite of a prodigious amount of shouting and blowing of horns, could not get forward. Some three hours later a second engagement was fought on the other side of Villers-Cotterêts. The 4th Brigade retired through the 6th Brigade, which with the field artillery had taken up a position at the edge of another wood. The enemy's first shells came over as the 4th Brigade moved into the wood. The British guns succeeded in keeping the Germans at bay, but were only got away with the utmost difficulty and some loss.

Having borne the brunt of the fighting, the 4th Brigade had necessarily suffered heavy casualties.

The 2nd Battalion Grenadiers lost 4 officers and 160 men, while the Irish Guards lost 4 officers and the Coldstream 7, as well as a large number of men. Two exceptionally good officers in the Irish Guards were killed—Colonel the Hon. G. Morris and Major H. F. Crichton. The latter served in the Grenadiers for some years before exchanging into the Irish Guards.[1]

37On emerging once more into open country, the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers was sent off to march to Boursonne, which it reached about 4 P.M. Two companies of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream were ordered back to support the 6th Brigade, which was now protecting the retreat of the guns; but they were not wanted after all, and were sent back to Boursonne after a fruitless journey. Then General Monro rode up, and ordered the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers to take up a rear-guard position about Boursonne, to cover the retirement of the 6th Brigade. Meanwhile, the Brigade Headquarters, the Irish Guards, and the 3rd Battalion Coldstream went on to Betz.

When the 6th Brigade had passed through, the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers and 2nd Battalion Coldstream retired to Thury. Unfortunately no orders had been given them to go to Betz, and through following the 6th Brigade these two battalions missed the guide whom Battalion Headquarters had sent to meet them. Once more the men were absolutely dead beat. They had had nothing to eat since tea the day before, but when the matter of food was inquired into 38it was found that all the supplies had gone on to Betz. This was at 11 o'clock at night, and it looked as if the men would have to bivouac foodless by the roadside.

Heroic measures were called for, and Major Jeffreys decided to brush aside the ordinary procedure and shortcircuit the usual channels of communication by going straight to the Divisional Commander, General Monro. He was instantly successful. On learning of the sad plight of the Battalion, General Monro undertook to supply it with food. He ordered his D.A.Q.M.G. to take the Battalion to his supply depot, and Major Jeffreys went back and fell in his weary men.

With the promise of a meal ahead they responded gamely, and marched off to La Villeneuve, the place indicated by the General, where rations of bully-beef, bread, and cheese were soon distributed.

Then the men were allowed two hours' sleep by way of a night's rest after one of the longest and most strenuous days they had ever had. They were more fortunate, though, than the men of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards, who did not even manage to get any food that night, and who had to snatch what sleep they could lying down in the streets of Thury.

At 2 A.M. the Battalion marched off again—still retiring—through Antilly to Betz, where it was joined by No. 1 Company and 45 men of No. 4 under Lieutenant Stocks. Thence by Montrolle to Reez, where a halt was made for water, and on to Puisieux. Here the men 39had a late breakfast, and then, in stifling heat, continued their march, with constant halts, through La Chaussée and Barcy to Meaux. They reached this village at 4 P.M., and, their long day's journey ended, they were refreshed by a bathe in the Ourcq Canal. This march was almost the hardest of the whole retreat, but, in spite of everything, the Battalion marched on, with scarcely a man out of the ranks, although the number of men who fell out in other regiments was by no means small.

Undoubtedly the men were by now beginning to feel the strain of this interminable retirement. However footsore and weary they may be, British troops will always respond when called upon to advance. But to ask them to make a special effort when retreating is quite another thing, even with the most highly disciplined. Besides, they were quite unable to see the necessity of it all. There had been no pitched battle, no defeat—in fact, whenever they had had a chance they had inflicted enormous losses on the enemy and driven him back. Of course they had seen no newspapers, and had no way of picking up any real idea of what was going on in France.

Next morning at 7 o'clock the march was resumed eastwards, and the Division crossed the Marne at Trilport, blowing the bridges up after them. This new direction was the result of the Germans moving along the north bank of the Marne, which they crossed near Sammeron. Then the Battalion moved southward again, through Montceaux and Forêt du Mans to Pierre Levée, where it bivouacked.

40The men had expected a rest on September 4, but the order soon arrived for the Brigade to continue the retirement. No. 3 Company of the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers under Captain Gosselin, and No. 4 Company under Captain Symes-Thompson, were sent out on outpost duty.

In the morning the Brigade marched to Les Laquais, where trenches were dug, joining up with the 5th and 6th Brigades on the right. At 5 P.M. the enemy shelled the right of the line, and at dusk the Brigade withdrew. It picked up No. 3 Company at Grande Loge Farm, and marched through Maisoncelles and Rouilly le Fay to Le Bertrand, where it bivouacked for the night.

Meanwhile Major Lord Bernard Lennox was despatched to Coulommiers to find the first draft that had been sent out from home—90 men under Captain Ridley. They arrived about midday after a train journey of thirty-six hours—they had been all round the country, constantly receiving fresh orders to go to different places. Lord Bernard Lennox had been instructed to remain at Coulommiers, but when he found the First Division retiring through the town all the afternoon, he decided to strike off westward with the new draft in search of the Battalion. This plan succeeded, and he found it about midnight.

It was a sadly tattered, unshaven, footsore body of men that marched at 3 o'clock next morning through La Celle and Malmaison Farm to Fontenay, where they went into billets. No Londoner seeing them would have guessed that these were the same smart Grenadiers whom he 41had often admired on the King's Guard. But if their looks were gone, their spirit was indomitable as ever.

The Germans seem to have been genuinely under the delusion that by this time the long retreat had reduced the British Army, always "contemptible," to a mere spiritless mob, which it was no longer necessary to take into calculation in developing their plan of campaign. They little knew the British soldier. So far the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers had had no chance of showing its quality; it had just been marched off its feet from the start—in the wrong direction. But, in spite of all the men had gone through, they were ready at any moment to turn and fight like lions when they were allowed to.

And now at last the moment was close at hand. To their joyful surprise the officers of the Battalion found, on the morning of September 6, that the direction had been changed, and that an advance was to be made eastward against the German flank. At first it was thought that this meant the beginning of an offensive-defensive, the German attack having failed; but in reality, of course, the change was a much bigger one even than this. The French reserves were now available, and the Germans' greatest asset, superior numbers, was lost to them. And so a new phase of the campaign began to develop.

On the 6th Lieut.-Colonel Corry resumed the command of the Battalion, and Lieut.-Colonel G. Feilding took command of the Brigade.

The German General Staff at this juncture realised that a retreating army is not necessarily a beaten one. For the last ten days, with their maps spread before them, they had had the satisfaction of moving the pins and flags representing their forces continually and rapidly nearer and nearer Paris. But if the French Army—the British Army, they thought, could be safely ignored—were to succeed in escaping south, it would remain a constant menace. It might even interfere with the Emperor's spectacular entry into Paris, every detail of which had been sketched out beforehand by the officials, whose business it was to stage-manage all the theatrical pageantry of their Imperial master's movements.

So a big coup was wanted—a smashing blow at the French. If the centre of the French line could be pierced by the combined efforts of Von Hausen's, the Duke of Würtemberg's, and the Crown Prince's armies, and if simultaneously Von Kluck's army, which had reached Senlis, and was only twenty-five miles from Paris, could execute a swift movement to the south-east, the Fifth French Army would be caught in a vice. 43This strategic plan really menaced the whole of the interior of France, and had it succeeded might have resulted in her downfall. In all these calculations of the German Staff it appears to have been assumed that the British Army was practically out of action, and that whatever remained of it had in all probability been sent to reinforce the weak spot at Bar-le-Duc.

To accomplish his decisive stroke, Von Kluck had to execute that most dangerous of all manoeuvres, a flank march with the object of rolling up the left of the French line. The German General Staff assumed that the left of the Fifth French Army was the left of the whole French line, and that nothing beyond a few cavalry patrols had to be reckoned with. Von Kluck was accordingly given orders to march his army to the left and attack the Fifth French Army under General Franchet d'Esperey. They knew nothing of the Sixth Army under General Maunoury, which had arrived with such dramatic suddenness in taxi-cabs from Paris.

The unknown and the despised elements proved Von Kluck's undoing. Before he had gone very far he found the completely ignored British Army on top of him, and the totally unexpected Sixth French Army on his right flank. Quickly realising his peril, he decided to retire. In the meantime, on the French side, General Foch, who was about in the centre of the French line, saw an opportunity, which he promptly seized, of driving a wedge between the armies of Von Hausen and Von Bülow. The situation was now entirely changed. The lately 44triumphant German forces were no longer even moderately secure, and decided on a general retirement all along the line.

It was on September 5 that Sir John French and General Joffre conferred together and decided to take the offensive. To the British Army was assigned the space between the Fifth and Sixth French Armies. This meant a change of front, and hence that welcome order to the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers to move due east instead of south.

That evening Field-Marshal Sir John French issued the following orders:

(1) The enemy has apparently abandoned the idea of advancing on Paris and is contracting his front and moving south-east.

(2) The Army will advance eastward with a view to attacking. Its left will be covered by the French Sixth Army also marching east, and its right will be linked to the French Fifth Army marching north.

(3) In pursuance of the above the following moves will take place, the Army facing east on completion of the movement.

First Corps: right on La-Chapelle-Iger, left on Lumigny, move to be completed 9 A.M.

Second Corps: right on La Houssaye, left in neighbourhood of Villeneuve, move to be completed 10 A.M.

Third Corps: facing east in the neighbourhood of Bailly, move to be completed 10 A.M.

Cavalry Division (less 3rd and 5th Brigades): to guard front and flanks of First Corps on the line Jouy-le-Chatel (connecting the French Fifth Army)—Coulommiers (connecting the 3rd and 5th Brigades). The 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades will cease to be under the orders of the First Corps and will act in concert under instructions issued by Brigadier-General Gough. They 45will cover the Second Corps connecting with the Cavalry Division on the right and with the Sixth French Army on the left.

Sunday, the 6th, was the joyful day when there came this turn of the tide, and that morning Sir John French issued an order to his Army in which he said:

After a most trying series of operations, mostly in retirement, which have been rendered necessary by the general strategic plan of the Allied Armies, the British Forces stand to-day formed in line with their French comrades, ready to attack the enemy. Foiled in their attempt to invest Paris, the Germans have been driven to move in an easterly and south-easterly direction, with the apparent intention of falling in strength on Fifth French Army. In this operation they are exposing their right flank and their line of communication to an attack by the Sixth French Army and the British Forces.

I call upon the British Army in France to show now to the enemy its power and to push on vigorously to the attack beside the Sixth French Army. I am sure I shall not call on them in vain, but that on the contrary by another manifestation of the magnificent spirit which they have shown in the past fortnight they will fall on the enemy's flank with all their strength, and in unison with their Allies drive them back.

At 5.30 the same morning the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers marched to Le Mée, where trenches were dug. The men, for once, had had a good night's rest, and were in great spirits at the prospect of an advance. A sharp artillery attack was being carried on against Villeneuve, and the 1st Brigade was moved out to attack the place, while the 4th Brigade prolonged the line on the left. Being in reserve, the 2nd Battalion 46Grenadiers saw little of the day's fighting. In the event the artillery proved sufficient to shift the enemy, and the Battalion marched without further incident to Touquin, where it bivouacked for the night. That night the British Army occupied a line from Dagny on the right to Villeneuve-le-Comte on the left.

Severe fighting went on all along the line next morning. Maunoury's taxi-cab army had been able to press Von Kluck as he retired, and the British Army had taken Coulommiers and La Ferté-Gaucher. As the German battalions retreated shells were poured on them by our artillery, who were kept well posted with information by the aircraft observers. Marching through Paradis, Mauperthuis, St. Simeon, and Voigny, the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers finally bivouacked at Rebais. Everywhere in the villages were staring evidences of the German occupation and hurried retreat. Shops had been looted, houses despoiled, and the contents—such as could not be carried away—had been wantonly destroyed, evidently under orders, and the fragments scattered to the winds. The advance-guard of the 4th Brigade (the 2nd Battalion Coldstream) was engaged with the German rearguard during this march, and the Grenadiers who were in support came in for a certain amount of firing. The Germans could be plainly seen retiring by Rebais with masses of transport in great confusion.

Battle of the Marne. Position of the British Army on September 8, 1914.

It became clear next day that Von Kluck's Army was in retreat, and Sir John French determined to press him and give him no rest—thus 47completely were the positions reversed. The First Corps advanced, and everything went well at first, but at La Trétoire it was held up by the German rear-guard, which had found a good position, and the 3rd Battalion Coldstream, which formed the advanced guard, was checked for a time by the German machine-guns hidden in the houses round the bridge over the Petit Morin. Meanwhile, a German field battery posted near Boitron shelled the high ground over which the main body of the 4th Brigade had to pass.

The Germans were evidently fighting a delaying action, and were employing their cavalry with great skill to hold the river as long as possible. In front of the British Army, the cavalry covering the retreat of Von Kluck's Army was commanded by General von der Marwitz, who showed no intention of abandoning his position without a struggle.

Thick woods run down to the river for the last half-mile here, but right through them goes one big clearing about eighty yards wide. This was swept by the German machine-guns, and it was a problem how to get the men across. No. 3 Company Grenadiers under Captain Stephen was sent on to support the Coldstream, followed later by No. 4 under Captain Colston. Both companies reached the edge of the wood, but were there stopped by a hail of fire from the machine-guns. Our field-guns could not reach the houses where these had been placed, and the howitzers were unaccountably slow in coming up. It was while he was endeavouring to find some way of advance that Captain Stephen was 48shot through both legs; he was taken to hospital, and died of his wounds four days later.

Urgent messages to push on kept arriving meanwhile from Sir Douglas Haig. Lieut.-Colonel Feilding, who was temporarily in command of the Brigade, sent the 2nd Battalion Coldstream by a circuitous route to try and effect a crossing at La Forge, farther to the right. No. 1 and No. 2 Companies Grenadiers were then ordered to go round by a covered route to avoid the clearing in the wood, and had actually started when Lieut.-Colonel Feilding gave the order for them to turn about. Major Lord Bernard Gordon Lennox, who had raced off at their head, was so far in front that the order did not reach him. He rushed across the clearing, and just managed to get into a ditch on the other side, the shower of machine-gun bullets churning up the ground almost at his heels.

So deafening was the noise of the firing that it was impossible to pass orders simultaneously to the men scattered about in the woods, who at the same time were all on edge to advance. And soon it became very difficult to keep the troops together.

Lieut.-Colonel Corry had already gone off with these two companies, Nos. 1 and 2, to follow the 2nd Battalion Coldstream, when Lieut.-Colonel Feilding thought he saw the Germans retiring, and shouted to Major Jeffreys to turn the Grenadiers about and take them across the clearing straight down to the river, but No. 2 Company had got a good way ahead through the woods, and Major Jeffreys was only able 49to get hold of half of No. 1 Company, which followed him across the clearing. Unfortunately, however, the German guns were still there, and opened a heavy fire on them. By this time the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers was hopelessly split up, different parts of the Battalion having gone in three different directions, and the 3rd Battalion Coldstream was also scattered all over the woods. In the meantime the howitzers came up, and soon drove the Germans out of their position. No. 3 Company had done well in the fighting, having succeeded in capturing one of the enemy's machine-guns and many prisoners.

The various parties then made their way through the wood to the edge of the stream, but as there was no bridge to be seen they worked along the banks to La Trétoire. Without further opposition, a party of the Irish Guards under Major Herbert Stepney, together with half of No. 1 Company under Major Jeffreys and Lieutenant Mackenzie, crossed the bridge, and advanced up the opposite side towards Boitron. In every direction the ground was strewn with dead and wounded Germans, and after advancing 1000 yards the party of Grenadiers reached the position which had been occupied by the German Battery; the guns had all been got away, but dead horses, overturned limbers, and dead gunners showed how this Battery had suffered at the hands of the 41st Brigade R.F.A.

As the enemy retired our guns and howitzers kept up a heavy fire, and inflicted severe losses.

The whole Brigade had by now debouched 50from the woods, and gradually collected behind Boitron, while the Divisional Cavalry went on ahead so as to keep in touch with the retreating enemy. The 2nd Battalion Grenadiers was then ordered to advance in artillery formation over the open country north of Boitron, and met with no resistance.

But there was one incident that might have proved disastrous. In its eagerness to get at the enemy, No. 2 Company got rather ahead of its time, with the result that our own guns planted some shrapnel into it, luckily without doing much damage. On the left the Irish Guards and the 2nd Battalion Coldstream found in a wood a number of Germans with machine-guns, who had apparently got separated from the main body. Our men charged, and immediately up went the white flag; seven machine-guns and a large number of prisoners were taken, mostly men belonging to the Guard Jäger Corps.

Rain had been falling for some time in a steady downpour, and as the light was failing the Battalion assembled to bivouac near Les Peauliers. An extremely wet sainfoin field was chosen for the purpose, and there, in a misty September evening, the men lay down to sleep. Altogether the Grenadiers had lost forty men in the day's fighting, besides Captain Stephen.