The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

Chapter I. Thrilling Voyage in a Sea-plane.

Chapter III. Farewell to the Factory.

Chapter IV. Dragged by a Zeppelin.

Chapter V. Ran Away With an Automobile.

Chapter VI. Death Ride of an Aviator.

Chapter VII. Alone on a Strange Coast.

Chapter VIII. One Dark Night in Ypres.

Chapter IX. Testing Billy’s Nerve.

Chapter X. On the Road to Roulers.

Chapter XI. They Meet a General.

Chapter XII. With the British Army.

Chapter XIII. The Boys Under Fire.

Chapter XIV. In an Armored Motor Car.

Chapter XV. Farewell to Francois.

Chapter XVI. The Valley of the Meuse.

Chapter XVII. The Point of Rocks.

Chapter XVIII. At the Mouth of the Tunnel.

Chapter XIX. Through the Secret Passage.

Chapter XX. Behind Château Panels.

Chapter XXI. Henri Finds the Key.

Chapter XXII. The Fortune of the Trouvilles.

Chapter XXIII. Trailed by a Chasseur.

Chapter XXIV. A Race for Life.

Chapter XXV. The Sergeant to the Rescue.

Chapter XXVII. The Boys Go Gun Hunting.

Chapter XXVIII. Good News from Dover.

Chapter XXX. Setting Out for the Sea.

Chapter XXXI. Like a Miracle of Old.

Chapter XXXII. Like a Dream of Good Luck.

Chapter XXXIII. The Sealed Packet.

Chapter XXXIV. At the Front Door of Paris.

Chapter XXXV. The Flight Up the Seine.

Chapter XXXVI. The Way That Went Wrong.

Chapter XXXVII. Out of a Spider’s Web.

Chapter XXXVIII. The Fortune Delivered.

Chapter XXXIX. The Call of the Air.

Chapter XL. Captured by the Germans.

Chapter XLI. The Boys Put on the Gray.

Chapter XLII. Fought to the Finish.

Chapter XLIII. Setting of a Death Trap.

Chapter XLIV. A Life in the Balance.

Chapter XLV. The Ways of the Secret Service.

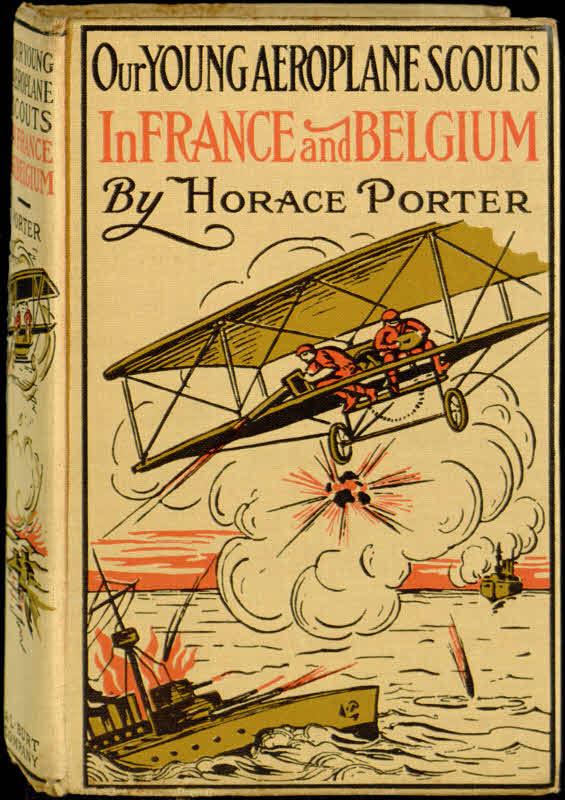

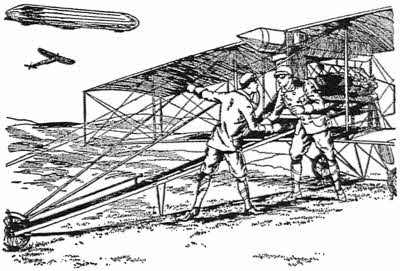

FREEMAN GAVE A WARNING SHOUT: “DOWN WITH YOU,

SHE’S TRAILING HER ANCHOR!” Page 15.

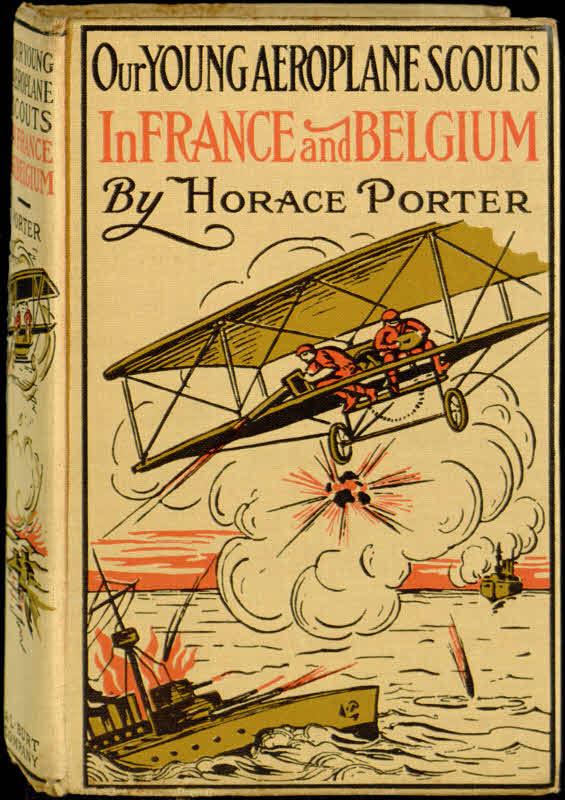

The Aeroplane Scouts In France and Belgium.

By HORACE PORTER

AUTHOR OF

“Our Young Aeroplane Scouts In Germany.” “Our Young

Aeroplane Scouts In Russia.” “Our Young

Aeroplane Scouts In Turkey.”

A.L. BURT COMPANY

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1915

By A. L. Burt Company

OUR YOUNG AEROPLANE SCOUTS IN FRANCE

AND BELGIUM

OUR YOUNG AEROPLANE SCOUTS

IN FRANCE AND BELGIUM.

It was a muggy night in Dover—not an unusual thing in Dover—but nevertheless the wind had an extra whip in it and was lashing the outside Channel into a state of wild waves. An acetylene flare revealed several muffled figures flitting here and there on the harbor brink. There was a glint from polished surface, a flash-like, downward rush of a long, tapering hull, and a splash in the dark waters below. A sea-plane had been deftly launched. Motors hummed, a wide wake streamed away to the rear of the wonder craft, which, suddenly, as if by magic drawn upward from the tide, joined the winds that sported aloft.

Captain Leonidas Johnson, noted as an airman in the four quarters of the globe, sat tight behind the rudder wheel, and back in the band-box engine room was Josiah Freeman, one time of Boston, U. S. A.

Two aboard were not of the regular crew. Behind[4] the wind-screen were Billy Barry and Henri Trouville, our Aviator Boys, bound for the coast of France, and bound to get there.

Ever higher and higher, the intrepid navigators sailed into a clearing atmosphere, where the clouds were being gathered into a moonlight bath. The 120’s were forcing a speed of something like a mile to the minute, and doing it at 2000 feet above the sea level.

Through Dover Straits the swift trend of the great mechanical bird was toward the North Sea, the blurring high lights of Dover fading in the distance rearward and Calais showing a glimmer on the distant right.

Captain Johnson switched on the ghost light to get his bearings from the facing dials, and speaking to the shadowy figures in the observation seat indulged in a bit of humor by asking:

“You young daredevils, how does this strike you?”

An answering high note from Billy:

“You’re doing bully, Captain, but mind your eye and don’t knock a hole in Dunkirk by flying too low.”

“Well, of all the nerve,” chuckled the veteran wheelman, “‘flying too low,’ and the sky almost close enough to touch.”

A pressure forward on the elevating lever shot the sea-plane downward, and the turn again to level[5] keel was made a scant five hundred feet above the choppy surface of the Channel.

“We’ll take to boating again at Dunkirk,” observed the captain, but the observation was heard only by himself, for now the wind and the waves and the motors and the straining of the aircraft combined to drown even a voice like the captain’s.

There was destined to be no landing that night at Dunkirk. An offshore gale, not to be denied, suddenly swept the Channel with howling force. Rising, dipping, twisting, the sea-plane dashed on in uncertain course, and when at last it had outridden the storm, Ostend was in sight—the Atlantic City of the Belgians.

The stanch aircraft, with engines silenced, rocked now upon the heaving tide. Its tanks were empty. Not a drop of petrol in them. Retreat was impossible, and in the broad light of the new day there was no place of concealment.

While four shivering shapes shifted cramped positions and gratefully welcomed the warming sun-rays, they were under survey of powerful field-glasses in the hands of a gray-garbed sentry.

After following Billy and Henri in their perilous and thrilling night ride, it has occurred that they should have first been properly introduced and their mission in the great war zone duly explained. Only a few weeks preceding their first adventure, as described in the initial chapter, they were giving flying exhibitions in Texas, U. S. A.

“That’s a pair for you!” proudly remarked Colonel McCready to a little group of soldiers and civilians intently looking skyward, marking the swift and graceful approach through the sunlit air of a wide-winged biplane, the very queen of the Flying Squadron.

With whirring motor stilled, the great bird for a moment hovered over the parade ground, then glided to the earth, ran for a short distance along the ground and stopped a few feet from the admiring circle.

“That’s a pair for you!” repeated Colonel McCready, as he reached for the shoulders of the youth whose master hand had set the planes for the exquisitely exact landing and gave a kindly nod to the young companion of the pilot.

“I’ll wager,” continued the colonel delightedly,[7] “that it was a painless cutting of Texas air, this flight; too fast to stick anywhere. Fifty-five miles in sixty minutes, or better, I think, and just a couple of kids—size them up, gentlemen—Mr. William Thomas Barry and Mr. Henri Armond Trouville.”

Billy Barry adroitly climbed out of the little cockpit behind the rudder wheel and patiently submitted to the colonel’s hearty slaps on the back. Billy never suffered from nerves—he never had any nerves, only “nerve,” as his Uncle Jacob up in the land where the spruce comes from used to say. Billy’s uncle furnished the seasoned wood for aëroplane building, and Billy’s brother Joe was boss of the factory where the flyers are made. Billy knew the business from the ground up, and down, too, it might be added.

And let it be known that Henri Trouville is also a boy of some parts in the game of flying. He loved mechanics, trained right in the shops, and even aspired to radiotelegraphy, map making aloft, and other fine arts of the flying profession. Henri has nerves and also nerve. He weighs fifty pounds less than Billy, but could put the latter to his best scuffle in a wrestling match. Both of them hustled every waking minute—the only difference being that pay days meant more to Billy than they did to Henri.

No brothers were ever more firmly knit than they—this[8] hardy knot of spruce from Maine, U. S. A., and this good young sprout from the lilies of France.

There’s a pair for you!

“Say, Colonel,” said Billy, with a fine attempt at salute, “if I didn’t know the timber in those paddles I wouldn’t have felt so gay when we hit the cross-currents back yonder. I——”

“Yes, yes,” laughed the colonel, “you are always ready to offer a trade argument when I want to show you off. Now you come out of your shell, Henri, and tell us what you think of the new engine.”

“There is sure some high power in that make, sir,” replied Henri. “Never stops, either, until you make it.”

“All you boys need,” broke in Major Packard, “is a polishing bit of instruction in military reconnaissance, and you would be a handy aid for the service.”

“While I am only factory broke, Major,” modestly asserted Billy, “Henri there can draw a pretty good map on the wing, if that counts for anything, and do the radio reporting as good as the next. What a fellow he is, too, with an engine; he can tell by the cough in three seconds just where the trouble is. If I was going into the scout business,[9] believe me, I might be able to make a hit by dropping information slips through the card chute.”

The dark-eyed, slender Henri shook a finger at his talkative comrade.

“Spare me, old boy, if you please,” he pleaded. “Gentlemen,” turning to the others, who were watching the housing of the aëroplane, “this bluffer wouldn’t even speak to me when the altitude meter, a little while ago, registered 3,000 feet. Then he had a wheel in his hands; down here he has it in his head!”

“Bully for you, comrade,” cried Billy. “I couldn’t have come back that neatly if I tried. But then, you know, I have to work to live, and you only live to work.”

With this happy exchange the boys moved double quick in the direction of quarters and the mess table.

Colonel McCready, with the others proceeding to leisurely follow the eager food seekers, in his own peculiar style went on to say:

“There’s a couple of youngsters who have been riding a buckboard through some fifty miles of space, several thousand feet from nowhere, at a clip that would razzle-dazzle an eagle, and, by my soul, they act like they had just returned from a croquet tournament!”

Our Aviator Boys had grown fearless as air riders. They had learned just what to do in cases of emergency, in fact were trained to the hour in[10] cross-country flying. Rare opportunity, however, was soon to present itself to give them a supreme test of courage and skill.

Little they reckoned, this June evening down by the Alamo, what the near future held in store for them.

An archduke had been killed on Servian soil, and war had raised its dreadful shadow over stricken Liège. The gray legions of the Kaiser were worrying the throat of France. From the far-off valley of the Meuse came a call of distress for Henri Trouville.

Billy Barry was very busy that day with the work of constructing hollow wooden beams and struts, and had just completed an inspection of a brand-new monoplane which the factory had sold to a rich young fellow who had taken a fancy to the flying sport. Coming out of the factory, he met his chum and flying partner. Henri did not wear his usual smile. With downcast head and his hands clasped behind him he was a picture of gloom.

“Hello, Henri, what’s hurting you?” was Billy’s anxious question.

“Billy boy,” Henri sadly replied, “it’s good night[11] to you and the factory for me. I’m going home.”

“Say, Buddy,” cried Billy, holding up his arm as though to ward off a shock, “where did you get your fever? Must have been overwarm in your shop to-day.”

“It’s straight goods,” persisted Henri. “The world has fallen down on Trouville and I’ve got to go back and find what is under it.”

Billy with a sob in his voice: “Old pal, if it’s you—then it’s you and me for it. I don’t care whether it’s mahogany, ash, spruce, lance-wood, black walnut or hickory in the frame, we’ll ride it together.”

“Oh, Billy!” tearfully argued Henri; “it’s a flame into which you’d jump—and—and—it wouldn’t do at all. So, be a good fellow and say good-by right here and get it over.”

“You can’t shake me.” Billy was very positive in this. “We made ’em look up at Atlantic City. We can just as well cause an eye-strain at Ostend or any other old point over the water. The long way to Tipperary or the near watch on the Rhine—it’s all one to me. I’m going, going with you, Buddy. Here’s a hand on it!”

The boys passed together through the factory gate, looking neither to the right nor to the left, nor backward—on their way to great endeavor and to perils they knew not of.

Out to sea in a mighty Cunarder, the “flying[12] kids,” as everybody aboard called them, chiefly interested themselves in the ship’s collection of maps. As they did not intend to become soldiers they were too shrewd to go hunting ’round war zone cities asking questions as to how to get to this place or that. They had no desire to be taken for spies.

“Right here, Billy,” said Henri, indicating with pencil point, “is where we would be to-night if I could borrow the wings of a gull.”

Billy, leaning over the map, remarked that a crow’s wings would suit him better, adding:

“For we would certainly have to do some tall dodging in that part of the country just now.”

“Do you know,” questioned Henri earnestly, “that I haven’t told you yet of the big driving reason for this dangerous journey?”

“Well,” admitted Billy, “you didn’t exactly furnish a diagram, but that didn’t make much difference. The main point to me was that you tried to say good-by to your twin.”

“Billy,” continued Henri, drawing closer, and in voice only reaching the ear at his lips, “behind a panel in the Château Trouville are gold and jewels to the value of over a million francs. It is all that remains of a once far greater fortune. My mother, when all hope of turning back the invading armies had gone, fled to Paris in such haste that she took with her little more of worth than the rings on her hands. She may be in want even now—and she[13] never wanted before in her life. I am her free man—my brothers are in the trenches with the Allies somewhere, I don’t know where. It’s up to me to save her fortune and pour it into her lap.”

“It’s the finest thing I know,” said Billy. “Show me the panel!”

Planning their first movement abroad, the boys that night decided to make for Dover after landing. It was a most convenient point from which to proceed to the French coast, and there they expected to find two tried and true friends, airmen, too, Captain Leonidas Johnson and Josiah Freeman, formerly employed as experts in the factory at home, and both of whom owed much to Billy’s uncle in the way of personal as well as business favors.

What happened at Dover has already been told, and now to return to them, stranded in the water off the Belgian coast.

For hours Billy had been stationed as lookout on the stranded hydroplane. He was taking cat-naps, for it had been quite a while since he last enjoyed a bed. While an expected round-shot from the[14] shore did not come to disturb the tired airmen, something else happened just about as startling. In a waking moment Billy happened to look up, and there he saw a great dirigible circling above the harbor. The boy’s eyes were wide open now.

“Henri,” he loudly whispered, prodding his sleeping chum with a ready foot. “Look alive, boy! They’re coming after us from the top side!”

Henri, alive in a jiffy, passed a friendly kick to Captain Johnson, and he in turn bestowed a rib jab upon Freeman. Then all eyes were glued on the hovering Zeppelin.

A mile seaward, from the armored side of a gunboat, burst a red flash wreathed by smoke; then a dull boom. The Zeppelin majestically swerved to southwest course, all the time signaling to masked batteries along the shore.

“There is bigger game around here than us,” said Captain Johnson. “If only those tanks were chockfull of petrol again we’d show them all a clean pair of heels.”

“If we don’t move somehow and soon,” gloomily put in Freeman, “we’ll be dead wood between two fires.”

The Zeppelin was now pushing skyward, buzzing like a million bees. Just then a Taube aëroplane, armored, swooped toward the gunboat, evidently British, which had endeavored to pot the Zeppelin. The scout-ship below turned its anti-aircraft cannon[15] and rifles against the latest invader, cutting its wings so close that the Taube hunted a higher and safer level. The Zeppelin had again lowered its huge hulk for the evident purpose of dropping on the gunboat some of the bombs stored in its special armored compartment.

Another sputtering jet of flame from the gunboat and one of the forward propellers of the airship collapsed and a second shot planted a gash in her side. Sagging and wabbling, the dirigible headed for the Belgian coast. When the black mass loomed directly above the stranded sea-plane, Freeman gave a warning shout:

“Down with you! She’s trailing her anchor!”

By quick thought, in that thrilling, fleeting moment, Billy grabbed the swinging anchor as it was dragged along near to him and deftly hooked one of its prongs under the gun carriage at the sea-plane’s bow.

With jerks that made every strut and wire crackle under the strain, the hydroplane, on its polished floats, skipped over the waves, pulled this way and that, now with elevated nose, now half under water, but holding firmly to the trailing cable.

Henri, with head over the wind-screen, keenly watched the shore for a likely landing-place. The men in the cars of the disabled Zeppelin did not seem to notice the extra weight on the anchor—they[16] had troubles of their own in getting the damaged dirigible to safe landing.

Billy crouched in the bow-seat, his eyes fixed on the straining cable. In his right hand he clutched a keen-edged hatchet, passed forward by Freeman. Half drowned by the spray tossed in his face he awaited the word from Henri.

“Say when, old pard,” he cried, slightly turning his head.

“If she pulls straight up and down,” remarked Captain Johnson in Freeman’s ear, “it’s good night.”

The coast line seemed rushing toward the incoming sea-plane, bouncing about in the wide wash.

Henri sighted a friendly looking cove, and excitedly sang out the word for which his chum was waiting:

“Now!”

With the signal Billy laid the hatchet with sounding blows upon the cable—and none too soon the tough strands parted.

The sea-plane with the final snap of the hacked cable dashed into the drift and plowed half its length in the sandy soil. The Zeppelin bobbed away into the gathering dusk.

Following the bump, Captain Johnson set the first foot on the sand. Stretching himself, he fixed a glance of concern on the sea-plane.

“I wonder if there is a joint in that craft that[17] isn’t loose?” he questioned. “But,” he added, with a note of sorrow, “it’s not likely she will ever see her station again, and so what’s the difference?”

“It was some voyage, though,” suggested Freeman in the way of comfort.

“It was bully,” maintained Billy. “If we had traveled any other way, Henri there would no doubt by this time have been wearing red trousers and serving the big guns around Paris, and I might have been starving while trying to get change for a ten-dollar bill in that big town.”

“Do you think you will like it better,” asked Freeman, “to stand up before a firing squad with a handkerchief tied ’round your eyes?”

“I should worry,” laughed Billy.

“There’s no scare in you, boy,” said Captain Johnson, giving Billy an affectionate tap on the back. “Now,” he continued seriously, “it’s hard to tell just what sort of reception we are going to get hereabouts. Old Zip and I” (turning to Freeman) “certainly made the people on the paved ‘boardwalk’ stare with some of our flying stunts. But that was last year.”

“That reminds me,” broke in Billy, “that I have given the high ride to several of the big ‘noises’ on all sides of the war, and they one and all promised me the glad hand if I ever came to see them.”

“That, too,” said Freeman, with a grin, “was a year or more ago.”

[18]

“Speaking of time,” put in Henri, “it also seems to me a matter of a year or two since I had anything to eat. I’m as hungry as a wolf.”

“I’m with you on the eat proposition,” Billy promptly cast his vote. “Where’s the turkey hid, Captain?”

“It’s a lot of turkey you’ll get this night,” grimly replied the captain. “There’s a little snack of sandwiches in the hold, cold roast, I believe, but that’s all. We didn’t equip for a sail like this.”

Billy and Henri lost no time rummaging for the sandwiches, and while the meat and bread were being consumed to the last crumb by the hungry four, Billy furnished an idea in place of dessert:

“We don’t want to lose ten thousand dollars’ worth of flying machine on this barren shore. Henri and I are going to do a bit of scouting while the soldier crowd are busy among themselves up the coast. If there is any petrol to be had we are going to have it.”

Fitting action to the words, the two boys moved with stealthy tread, Indian fashion, toward the ridge that shadowed and concealed the temporary camp of the airmen. Captain Johnson did not wholly approve of this venture on the part of the boys, but they did not give him time to argue against it, and were soon beyond recall.

Night had come and in front of one of the handsome hotels that had escaped splintering when Ostend, the famous seaside resort, under fire of big guns, was swept by shot and shell, Gun-Lieutenant Mertz had just stepped out of a big gray automobile that looked like a high speeder—the kind that has plenty of power. The driver of the car did not wait for a second order to leave the lieutenant and speed away in the direction of the mess quarters, where he knew that there was a fragrant stew being prepared for duty men coming in late.

The fighting of the day had mostly taken place far up the coast, and the chance had arrived for a loosening of belts in Ostend.

With a final chug the big gray car came to a standstill in a quiet corner off the main street, while the hungry chauffeur joined his comrades in what they called pot-luck. The movements of this man had been watched with a large amount of interest by a pair of visitors, who had chosen the darkest places they could find while approaching the dining hall of the soldiers.

“Gee!” whispered one of the watchers to the other. “I can almost feel a bullet in my back.”

[20]

From the companion shadow: “Take your foot out of my face, can’t you?”

Two heads uplifted at the sight of the rear lights of the car.

Again an excited whisper:

“Now for it, Billy!”

The soldiers were laughing and talking loudly in the dining hall.

The boys crawled along, carefully avoiding the light that streamed from the windows of the hall. A moment later they nimbly climbed into the car. Henri took the wheel and gently eased the big machine away into the shadowy background. Then he stopped the car and intently listened for any sound of alarm. The soldiers were singing some war song in the dining hall, keeping time with knives and forks.

It was a good time for the boys to make a start in earnest, and they started with no intention of stopping this side of the ridge, behind which their friends were anxiously watching and waiting for them.

Henri drove cautiously until he felt sure that they were out of the principal avenues of travel, and then he made things hum. He guided straight toward a clump of trees showing black against the moon just appearing above the crest of the hill. The riding grew rough, but the speed never slackened.[21] At last the goal was reached. The car bumped and bounced up, and bounced and bumped down the hill.

Leaping from the machine, Billy fairly rolled to the feet of the startled crew of the sea-plane.

“So help me,” exclaimed Captain Johnson, “if I didn’t think it was a section of the Fourth Corps after our scalps!”

“Hurry!” gasped Billy. “Get anything that will hold oil, and get it quick!”

For the moment confused, Johnson and Freeman seemed tied fast to the ground.

Henri rolled into the circle and added his gasp:

“We’ve a touring car up there and its tanks are loaded!”

Then the boss mechanic, Freeman, came to the front. From the depths of the engine room in the motor end of the sea-plane he pulled a heavy coil of rubber tubing and in a few minutes made attachments that tapped the automobile’s plentiful supply of petrol and sent it gurgling into the empty tanks of the sea-plane.

Across the sandy plain came the sound, faintly, of shouting. Maybe somebody had discovered that the officer’s car was missing.

As Billy suggested with a laugh:

“Perhaps they think some joy riders took it.”

“I’m not going to stay to find out what they[22] think,” very promptly asserted Captain Johnson. “Heave her out, boys!”

The sea-plane took the water like a duck. Obedient to Johnson’s touch it leaped upward, the motors were humming, and with a cheery cackle Freeman announced:

“We’re off again.”

“And they are showing us the way,” cried Billy, as a great searchlight inland sent a silver shaft directly overhead.

Bang! Bang! Bang! Riflemen on the ridge were popping at the sea-plane.

“There’s a salute for good measure,” observed Henri.

“Lucky we’re out of range of those snipers, but I’m thinking the batteries might attempt to take a whack at us.”

With these words Captain Johnson set the planes for another jump skyward.

“There’s the good old moon to bluff the searchlight,” sang out Billy from the lookout seat. “And, see, there’s a row of smokestacks sticking out of the water. Sheer off, Captain; don’t let those cruisers pump a shot at us. They’d wreck this flyer in a minute!”

The sea-plane was taking the back-track at fine speed when valve trouble developed in the engine room. The cylinders were missing fire, and all of Freeman’s expert tinkering failed to prevent the[23] necessity of rapid descent. The hum of the motors died away, and Captain Johnson dived the craft seaward with almost vertical plunge. The sea-plane hit the water with a dipping movement that raised a fountain over the lookout, and it was Billy that cried “Ugh!” when he was drenched from head to foot by the downfall of several gallons of cold water.

The aircraft had alighted only a few rods from land, in a shallow, marshy bay. The place was as silent as the grave, save for the calling of the night birds and the gentle lapping of the waves. Freeman with the aid of an extra propeller fitting, paddled the craft into shore, and was soon busy trying to find out what was the matter with the machinery. Captain Johnson held the acetylene flare over Freeman’s shoulder to enable the engineer to see where repair was needed.

Billy and Henri, out of a job for the time being, concluded that they would do some exploring. After wading through the mud, weeds and matted grass for a hundred yards or so they reached firm footing on higher ground.

The moon was shining brightly, and over the plain that stretched out before them on the left the boys could see quite a distance, but no sign of human life presented itself. On the right, however, a half mile away, was a sharp rise of ground and tall trees. Toward this point they decided to proceed. Then it was that they first realized the experience of standing on a battlefield.

Crossing the field they saw the ravages of artillery projectiles—deep, conical holes, five or six feet in diameter. Here, too, they found shrapnel cases, splinters of shells, skeletons of horses, fragments of bloodstained clothing and cartridge pouches. The moonlight made the path as open as day, and each object reminding of terrible conflict was apparently magnified by the white shine of the moon. The boys walked as in a dream, and were first awakened by the flapping wings of a huge bird, frightened by their approach from its perch on a broken gun-carriage.

“Let’s get out of this,” mumbled Henri; “it gives me shivery shakes; it’s a graveyard, and it seems like ghosts of dead soldiers are tracking us.”

Billy was short on nerves, but if he had been[25] called on for a confession just then he might have pleaded guilty to a tremble or two.

He managed to put on a bold front, however, and was about to give Henri a brace by telling him they would have to get used to the ways of war, when there was a sound like the roll of distant thunder far to the south.

“What’s that?”

Billy’s sudden question drove the ghosts away from Henri’s mind, and both boys ran like deer up the hill to the line of trees.

“There’s no storm over there,” panted Henri. “You can’t see a cloud as big as a man’s hand.”

“That isn’t thunder!” exclaimed Billy. “That’s cannon! They’re shooting at something!”

“There,” cried Henri, “that sounds like fire-crackers now.”

“Rifles,” observed Billy.

“Look!” Billy was pointing to what appeared, at the distance, to be a speck on the face of the moon.

The sound of gunfire increased, report after report—crack, crack, boom, boom, boom.

Across and far above the moonlit plain, arrow-like, sped a winged shadow, growing in size as it swiftly approached.

“An aëroplane!” The boys well knew that kind of a bird. They called its name in one voice.

[26]

“That’s what has been drawing the fire of those guns.”

Billy had found the problem easy to solve when he noted the getaway tactics of the coming airman.

The boys could now hear the whirring of the motor. Fifty yards away the aëroplane began to descend. Gracefully it volplaned to the earth under perfect control. It landed safely, rolled a little way, and stopped.

The boys, without a second thought, raced down the slope to greet the aviator, like one of their own kind should be greeted, but as quickly halted as they drew nearer.

The airman was dead.

He had been fatally wounded at the very start of his last flight, but just before death, at its finish, had set his planes for a descent. With his dead hands gripping the controllers, the craft had sailed to the earth. He wore the yellowish, dirt-colored khaki uniform of a British soldier.

Billy and Henri removed their caps in reverence to valor and to honor the memory of a gallant comrade who had been game to the last.

Releasing the dead aviator from his death grip on the controllers, the boys tenderly lifted the corpse from the driver’s seat in the machine and covered the upturned face and glazed eyes with the muffler the airman had worn about his neck. The[27] body was that of a youth of slight build, but well muscled. In the pockets of his blouse the boys found a pencil, a memorandum book and a photograph, reduced to small size by cutting round the face—a motherly type, dear to all hearts.

The usual mark of identity of soldiers in the field was missing, but on the third finger of the left hand was a magnificent seal ring, on which was engraved an eagle holding a scroll in its beak and clutching a sheaf of arrows in its talons.

Billy took possession of these effects with silent determination to some day deliver them to the pictured mother, if she could be found.

“The ring shows that he came of a noble house,” said Henri, who had some knowledge of heraldry.

“He was a brave lad, for all that, and noble in himself,” remarked Billy, who had the American idea that every man is measured by his own pattern.

So they gave the dead youth the best burial they could, at the foot of one of the giant trees, and sadly turned away to inspect the aëroplane that had been so strangely guided.

It was a beautiful machine, all the fine points visible to their practiced eyes—a full-rigged military biplane, armor plates and all. The tanks of extra capacity were nearly full of petrol.

“It must have been a short journey, as well as a fatal one,” said Billy. “Very likely the launching[28] was from a British ship, not far out at sea, and the purpose was to make a lookover of the German land forces around here.”

“I’d like to take a little jaunt in that machine,” sighed Henri, who could not tear himself away from the superb flyer.

“It may turn out that you will—stranger things have happened.”

Billy proved to be a prophet, but it was not a “little jaunt,” but a long ride that the boys took in that aëroplane.

An unpleasant surprise was in immediate store for them.

They decided that it was about time that they should return to their friends and the sea-plane, and were full of and eager to tell Johnson and Freeman of the results of their scouting.

“Guess the captain won’t wonder at anything we do since we brought that automobile into camp,” declared Billy. “You know he said that he hadn’t any breath to save for our next harum-scarum performance.”

“I can just see Freeman grin when I tell him that we have found a flying-machine that can beat his sea-sailer a mile. That’s my part of the story, you know,” added Henri.

“I can’t help thinking of the poor fellow who rode her last,” was Billy’s sober response.

The boys were nearing the point where the heavy[29] walking began. Otherwise they would have broken into a run, so eager were they to tell about their adventures.

Coming out of the weeds and ooze, they stood looking blankly at the spot where the sea-plane had rested.

The sea-plane and their friends were gone!

When the boys made the startling discovery that the sea-plane had disappeared and that they were alone on the strange coast, they plumped down on the sand without a single idea in the world except that they were utterly tired out and weak from hunger.

They could not account in any way for the mysterious happening that had deprived them of their tried and true friends.

Not for a moment did they imagine that they had been deserted by intent. They knew full well that even in the face of great danger Captain Johnson and Josiah Freeman were not the kind of men who would fly away, without sign or signal, and leave a comrade in distress, let alone these boys for whom either of the men would have spilled his last drop of blood.

[30]

“The coast patrol nabbed them,” was the opinion of Billy.

“They were held up at the point of a bayonet, I’ll bet,” argued Henri, “for there is no sign of a struggle, and we would have heard it if there had been any shooting.”

“However it was,” figured Billy, “they never quit of their own accord; they would never have left us unless they had been hauled away by force. Now it is up to us to skirmish for ourselves, which, anyhow, I expected to do sooner or later. There’s no use staying here, for they will be coming after us next.”

Wearily the boys plodded through the slush, backtracking to the foot of the hill where they had left the aëroplane. The fading moon was lost behind a wall of slowly rising mist, and the dawn was breaking in the east when the boys finally stumbled upon the place that held their prize. Wholly exhausted, they threw themselves full length upon the ground and slept like logs.

The sun was broadly shining when Billy reached out a lazy arm to poke his chum, who was snuggled up in the grass and breathing like a porpoise.

“Get up and hear the birds sing,” yawned Billy.

“I’d a good sight rather hear a kettle or a coffee-pot sing,” yawned Henri.

“Right O,” agreed Billy.

[31]

The boys rolled over alongside of the aëroplane. A twin thought came to them that the late aviator surely must have carried something to eat with him.

It proved a glorious truth. There was a knapsack behind the driver’s seat and a canteen swinging under the upper plane.

“A meat pie!” Billy made the first find.

“Crackers and cheese!” Heard from Henri.

How good these rations tasted—even the lukewarm water in the canteen was like nectar. With new life the boys took up the problem presented by the next move.

Henri climbed into the aëroplane and very carefully inspected the delicate machinery, making free use of the oil can. Billy otherwise attended to the tuning of the craft, and everything was as right as a trivet in less than a half hour.

“Let me see”—Billy was thumbing a well-worn notebook—“as we fixed it on the steamer, Dunkirk was the starting place. But that storm entirely changed the route—a longer way round, I guess. No more Ostend for me, though I do wish I knew for sure whether or not they had Captain Johnson and Freeman locked up there. Let’s try for Bruges; that’s only a short distance from here, and we can follow the line of the canal so we won’t get lost.”

“And we can fly high,” suggested Henri, “high enough to keep from getting plugged.”

[32]

“I am not bothering so much about the ‘high’ part of it as I am about where we’ll land,” said Billy. “We may fall into a hornet’s nest.”

“Let’s make it Bruges, for luck,” suggested Henri.

“Here goes, then,” exclaimed Billy, getting into steering position, Henri playing passenger.

Off they skimmed on the second stage of their journey to the valley of the Meuse, in France.

They had entered the zone where five nations were at each other’s throats.

So swift was their travel that our Aviator Boys very soon looked down upon the famous old belfry of Bruges, the old gabled houses, with bright red tiled roofs, mirrored in the broad canal crossed by many stone bridges. That is what Bruges means, “bridges.” To the young airmen, what the town meant just now was a good dinner, if they did not have to trade their lives or their liberty for a chance to get it.

“Nothing doing here,” lamented Henri, who did the looking down while Billy looked ahead. “I see that there are too many gray-coats visiting in West Flanders. And I heard that the Belgians have not been giving ‘days at home’ since the army came. Now I see that it is true.”

“Having fun with yourself?” queried Billy, in the sharp tone necessary to make himself heard in a buzzing aircraft.

[33]

Henri ignored the question, snapping: “The book says it’s thirty-five miles from here to Ypres, straight; keep your eyes on the waterways, and you can’t miss it.”

“Another thing the book says,” snapped Billy, in response, “is that that old town is in a district as flat as a floor, and, if nothing else, we are sure of a landing.”

“I wish we were as sure of a dinner.” Henri never lost sight of the dinner question.

The flight was continued in silence. It was a strain to keep up conversation, and the boys quit talking to rest their throats. Besides, there was not a drop of water left in the canteen.

It was late afternoon when the boys saw Ypres beneath them. It was just about the time that the Allies were advancing in the region between Ypres and Roulers, the town where the best Flemish lace comes from. But the Allies had not yet reached Ypres.

Henri glimpsed the remains of some ancient fortifications, and urged Billy to make a landing right there.

“A good place to hide in case of emergency,” he advised.

Billy agreed, set the planes for a drop, and came down neatly in the open.

“We ought to be able to get a change of linen here, for that’s the big business in this town.” Henri[34] was pretty well posted, for in his cradle he had slept on Ypres linen.

There was no work going on in the fertile fields around the town. The Belgian peasants thereabouts were either under arms or under cover.

“When King Louis set up these old ramparts he probably did not look forward to the day when they would provide a hangar for a flying-machine.” This from Billy, who was pushing the aëroplane to the shelter of a crumbling fortalice.

“If we had dropped in on the fourteenth century, as we did to-day,” observed Henri, “I’ll warrant that we would have scared everybody out of Flanders.”

“It doesn’t appear, as it is, that there is a person around here bold enough to approach us.”

Billy seemed surprised that they had not run into trouble at the very start.

“‘Never trouble trouble till trouble troubles you,’” quoted Henri. “It goes something like that, I think.”

“Listen!” Billy raised a hand to warn Henri not to move nor speak aloud. The sound that had put Billy on the alert was a long, low whistle. It was repeated, now and again. Curious, and also impressed that the whistler was trying to attract their attention, they began a search among the ruins. Over the top of a huge slab of stone suddenly popped a red cap, covering a regular Tom Thumb[35] among Belgians—about four feet from tow head to short boots.

Henri said “Howdy” to him in French, at the same time extending a friendly hand. The youngster, evidently about fifteen, shyly gave Henri two fingers in greeting. He bobbed his head to Billy. Then he removed his red cap and took out of it a soiled and crumpled slip of paper. On the slip, apparently torn from a notebook, was scribbled:

“This boy saw you fly in, told us how you looked, and, if it is you, this will let you know that the Germans brought us here for safe-keeping yesterday. Cap.”

“Glory be!” Billy could hardly contain himself, and the little Belgian took his first lesson in tangoing from an American instructor. “As soon as it is dark we will move on the outer works,” was his joyous declaration.

“Say, my young friend,” he added, “do you know where we can get a bite to eat while we’re waiting?” Henri translated, and the little Belgian was off like a shot. About dusk he returned with some bread and bologna, looped up in a fancy colored handkerchief. And there was plenty of water in the Yperlee river.

Along about 11 o’clock that night Leon, the little Belgian, whispered, “Venez” (Come).

The sky had turned dark over Ypres, rain had commenced to fall in streets so remarkably clean that they really did not need this bath from above. It was just the kind of a night, though, for the risky venture undertaken by our Aviator Boys. They were going to see their old friends, and nothing but a broken leg would check their willing steps on the way to the prison house that contained Captain Johnson and Josiah Freeman.

Leon knew the best way to get there. The darkest ways were light to him, and he was not afraid that rain would spoil his clothes. To guide these wonderful flying boys was the happiest thing that had happened to him in all his days, and, too, he had a strong dislike for the Germans who had invaded the homeland. His father was even now fighting in the ranks of the Allies at Nieuport, and his mother was wearing her heart out in the fields as the only breadwinner for her little brood.

There were comparatively few of the gray troops then in the town. The main columns were moving north to the Dixmude region, where the horizon was red with burning homes. To guard prisoners, garrison the town and care for the wounded not[37] many soldiers were then needed in Ypres, and non-commissioned officers mostly were in command.

The streets were empty and silent, and lights only occasionally seen. At midnight Billy, Henri and Leon paused in the deep shadow of a tall elm, the branches of which swept the front of the dingy red brick dwelling, two stories in height and heavily hung with vines. Leon knew the place like a book, for he had been serving as an errand boy for the guards quartered there.

He whispered to Henri that the men who had sent the note were in the front room on the second floor.

Behind the brick wall at the side of the house was a garden. Billy and Henri, on Leon’s advice, decided to try the deep-set door in the garden wall as the only way to get in without stirring up the sentry in the front hall. With the first push on the door the rusty hinges creaked loudly.

The front door of the house was thrown open, and a shaft of light pierced the darkness. The boys backed up against the wall, scarcely daring to breathe. The soldier looked up at the clouds, knocked the ashes out of his pipe, muttered something to himself, turned back and slammed the door with a bang. At this the boys gave a backward heave, and were through the door and into the garden.

This interior was blacker than the mouth of an[38] inkwell. Billy cautiously forced the door back in place.

“Got any matches?” Billy had failed to find any in his own pockets.

Henri was better supplied. In the military aëroplane he had not only found matches, but also a box of tapers, and he had taken the precaution of putting them in his pockets when they left the machine.

With a little flame, carefully shaded, the boys discovered a shaky-looking ladder in a grape-arbor at the back of the garden.

By degrees, foot by foot, they edged the ladder alongside of the house, and gently hoisted it to the window of the upper room, which Leon had assured them was the right one.

“Let’s shy some pebbles against the window to let them know we are here,” was the whispered suggestion of Henri.

“Nothing doing.” Billy was going to have a look in first. He was already crawling up the ladder. Henri laid hold of the lower rungs, to keep the rickety frame steady, and Leon stationed himself at the garden door, ready and alert to give warning whistle if anything happened in front.

Billy tapped softly on the window pane. The sash was silently raised, and Billy crept in.

Not a word had been spoken, and no signal from the room above.

[39]

Standing in the dark and the rain in the dismal garden, Henri was of half a mind to follow his comrade without further delay. It was an anxious moment.

A bird-like trill from Leon. With this call Henri left the ladder and tiptoed to the garden door to join the little Belgian and find out what was the matter.

From far up the silent street, coming with measured tread, a regiment was marching. The watchers at the door of the garden now plainly heard gruff commands and the other usual sounds of military movement.

“I must let Billy know; the soldiers are headed this way and might be coming to move the prisoners somewhere else.”

Henri had started back toward the house, when suddenly the window was thrown up, and, with a sound like the tearing of oil-cloth, Billy came down the ladder and landed with a bump on the graveled walk.

Henri and Leon, in the space of a second, rushed to the side of their fallen comrade.

In the street outside there was a crash that shook the silence as though the silence was solid. A regiment had grounded arms directly in front of the house.

Billy, who for a moment had been stunned by the force of his bump into the walk, at the end of[40] a twenty-foot slide, jumped to his feet, and in a breath urged his companions to run.

“Let’s get out of this; over the wall with you!”

The boys bolted for the back wall of the garden, dragging the ladder, and speedily mingled on all fours on the coping, the top of which was strewn with broken glass.

Hanging by their hands on the outer side of the wall they chanced the long drop. As luck would have it, they landed in soft places—on a pile of ashes and garbage.

Lights sprang up in the windows of the house behind them. It was evident that a change of base was to be made.

“Did you see our fellows?” was Henri’s first eager question, as he shook off his coat of ashes.

“You bet I did,” coughed Billy, whose face had plowed a furrow in the ash heap. “A bunch of the gray men in a motor boat pounced on them while they were tinkering with the sea-plane and took them and the plane in tow to Ostend. They were brought down here so that General So and So, I don’t remember who, could look them over, but the general and his brigade have gone off somewhere to the north to try and stop the advance of the Allies. The captain and Freeman both say they are in no special danger and are very kindly treated. They have their papers as American citizens and agents abroad for our factory. Then there is the[41] storm story as their reason for being blown into the war zone without fighting clothes.

“How did I come to quit that house yonder like a skyrocket? Well, just as the captain and I had finished exchanging experiences, and old Josh Freeman had nearly broken my ribs with a bear hug, one of the rounders in the house concluded to pay a visit to the room where we were. We didn’t hear him until he reached the top of the stairs, where he stopped to sneeze. With that sneeze I did my leaping act. That soldier never saw me; I’ll wager on that.”

“What’ll we do now?” That was more what Henri wanted to know.

“Get back to the machine before daylight.” Billy’s main idea was that the safest place was a couple of thousand feet in the air.

Daylight was not far away. Henri and Leon held a committee meeting to determine the best route back to the fortifications. The little Belgian was sure of his ground, and before sunrise, by countless twists and turns, the trio were back to the stone hangar where the aëroplane rested.

The first faint streaks of dawn gave light enough for Billy to do his tuning work about the machine. Henri was bending over, in the act of testing the fuel supply, when there was a thud of horses’ hoofs on all sides of the enclosure, followed by a shrill cry from Leon:

[42]

“Sauvez vous! Vite! Vite!” (Save yourself! Quick! Quick!)

With that the little Belgian frantically tugged at the aëroplane, and not until our Aviator Boys had swung the machine into the open and leaped to their places in the frame did the brave youngster quit his post. Then he ran like a rabbit, waving quick farewell, and disappeared in the wilderness of stone.

Lickety clip the aëroplane moved over the ground. Then up and away!

A pistol shot rang out. A cavalryman nearest to the point of flight was behind the weapon.

Barely a hundred feet in the air and Henri leaned heavily against Billy.

“I’m hit!” he gasped, “but don’t let go. Keep her going!”

It was indeed a severe test of Billy Barry’s nerve that was put upon him in this trying moment. To let go of the controllers of the aëroplane would mean the finish; to neglect for an instant his comrade, whom he believed to be bleeding to death, was agony. Almost blindly he set the planes for a nearly vertical descent from a dizzy height of three thousand feet which the machine had attained before[43] Billy had fully realized that he was holding across his knees the inert body of his beloved chum. Like a plummet the aircraft dropped eastward. With rare presence of mind Billy shifted for a rise when close to the ground, and managed to land without wrecking the machine. A scant ten feet, though, to the right, and the aëroplane would have crashed into a cow-shed and all would have been over.

An old woman, digging potatoes nearby, was so frightened when this winged bolt came down from the sky that she gave a squawk and fell backward into the big basket behind her.

When Billy had tenderly lifted out and laid Henri upon the turf, he ran to the well in front of the neat farmhouse, filled his leather cap with water, and hastened back to bathe the deathly pale face and throbbing temples of his wounded chum. With the cooling application Henri opened his eyes and smiled at the wild-eyed lad working with all his soul to win him back to life.

“I am not done for yet, old scout,” he faintly murmured.

Billy gulped down a sob.

“You’re coming around all right, Buddy, cried Billy, holding a wet and loving hand upon Henri’s forehead.

“The pain is in my right shoulder,” advised[44] Henri; “I have just begun to feel it. Guess that is where the bullet went in.”

“Let me see it.” Billy assumed a severe professional manner. The attempt, however, to remove the jacket sleeve from the injured arm brought forth such a cry of pain from Henri that Billy drew back in alarm.

“Ask the woman for a pair of shears,” suggested Henri, “and cut away the sleeve.”

“Hi, there!” called Billy to the old woman, who had risen from the basket seat, but still all of a tremble.

“Get her here,” urged Henri. “I can make her understand.”

Billy, bowing and beckoning, induced the woman to approach.

Henri, politely:

“Madame, j’ai ete blesse. Est-ce que nous restons ici?” (Madam, I have been wounded. Can we rest here?)

“Je n’ecoute pas bien. J’appelerai, Marie.” (I do not hear good. I will call Marie.)

With that the old woman hobbled away, and quickly reappeared with “Marie,” a kindly-eyed, fine type of a girl, of quite superior manner.

Henri questioned: “Vous parlez le Français?” (You speak French?)

[45]

“Oui, monsieur; j’ai demeure en le sud-est.” (Yes, monsieur; I have lived in the southeast.)

The girl quickly added, with a smiling display of a fine row of teeth: “And I speak the English, too. I have nursed the sick in London.”

“Glory be!” Billy using his favorite expression. “Get busy!”

Marie “got busy” with little pocket scissors, cut the jacket and shirt free of the wound, washed away the clotted blood and soon brightly announced:

“No bullet here; it went right through the flesh, high up; much blood, but no harm to last.”

Cutting up a linen hand-towel, Marie skillfully bandaged the wound, and, later, as neatly mended the slashes she had made in Henri’s jacket and shirt.

For ten days the boys rested at the farmhouse, Henri rapidly recovering strength.

They learned much about Belgium from Marie. She laughingly told Henri that his French talk was good to carry him anywhere among the Walloons in the southeastern half of Belgium, but in the northwestern half he would not meet many of the Flemings who could understand him. “You would have one hard time to speak Flemish,” she assured him.

Henri confided to Marie that they were bound for the valley of the Meuse.

“La la,” cried the girl, “but you are taking the[46] long way. Yet,” she continued, “you missed some fighting by coming the way you did from Bruges.”

On the eleventh morning Henri told Billy at breakfast that he (Henri) was again as “fit as a fiddle.” “Let’s be moving,” he urged.

“All right.” Billy himself was getting restless. They had been absolutely without adventure for ten long days.

But, when Henri returned from a visit to the aëroplane, he wore a long face.

“There’s no more ‘ammunition’ in the tanks,” he wailed. “There isn’t as much as two miles left.”

“That means some hiking on the ground.” With this remark Billy made a critical survey of his shoes. “Guess they’ll hold out if the walking is good.” Henri, however, was not in a humor to be amused.

“I say, Billy, what’s the matter with making a try for Roulers? Trouble or no trouble, we’ll not be standing around like we were hitched. It would be mighty easy if we could take the air. No use crying, though, about spilt milk.”

Marie, who had been an attentive listener, putting on an air of mystery, called the attention of the boys to a certain spot on the cleanly scrubbed floor, over which was laid a small rug of home weaving. The girl pushed aside the rug and underneath was shown the lines of a trap-door, into which Marie inserted a chisel point. The opening below disclosed[47] a short flight of steps leading down to an underground room, where candle light further revealed, among other household treasures, such as a collection of antique silver and the like, two modern bicycles.

“The boys who rode those,” said Marie, pointing to the cycles, “may never use them again. They were at Liège when it fell, and never a word from them since. On good roads and in a flat country you can travel far on these wheels. Take them, and welcome, if you have to go.”

In an hour the boys were on the road. They left two gold-pieces under the tablecloth and a first-class aëroplane as evidence of good faith.

Our Aviator Boys had not for a long time been accustomed to use their legs as vigorously and so continuously as required to make an endurance record on a bicycle. They had no great use for legs when flying. But they were light-hearted, and had been well fed, had enough in their knapsacks to stave off hunger for several days, and, barring the fact that Henri was still nursing a sore shoulder, ready to meet the best or the worst. Billy carried[48] a compass, also a mind full of directions from Marie, and firmly believed that he could not miss the good old town in the fertile meadow on the little river Mander. At least Henri and himself could live or die trying.

They had already observed indications that, even with the strenuous call to the colors of the Belgian men, the little kingdom was thickly populated, and about every square inch of farm land was under close cultivation.

“Suppose people lived this close together in Texas,” remarked Billy, as they pedaled along; “why, a man as tall across the front as Colonel McCready wouldn’t have room enough to turn around.”

“Yes, and from what we have heard of the war crowd working this way we’ll have to have more room than this to keep from running into them.” Henri was not in the same mood that he was when he found the aëroplane tanks empty.

“Nothing like a scare-mark so far,” was Billy’s comment. “I have seen only women in the fields.”

“Even the dogs have work to do here.”

Henri went on to explain that the small farmers, as a rule, cannot afford to keep horses, and just now could not keep them if they had them.

The boys had been fortunate in their first day’s travel as cyclists, in that they had not even fallen in with the stragglers of the contending armies reported[49] in terrible conflict inside the Dixmude-Nieuport line.

In the afternoon of the second day, however, they took the wrong road, one leading to Bixchoote.

In the distance they heard heavy and continuous artillery fire, and decided to turn back. “Out of the frying-pan into what next?” as Billy put it, when they found the woods north of Ypres were aflame with bursting shells. Fighting in front and fighting in the rear.

“The sides are still open,” declared Henri, “even if both ends are plugged.”

“But which side shall it be?” asked Billy.

The situation was one of great peril to the boys.

To get a better idea of the lay of the land, they rolled their bicycles into the woods alongside the road and climbed into the low hanging branches of a huge tree, then ascended to the very top of this monarch of the forest.

From their lofty perch they could see quite a distance in all directions, but they had no eyes for any part of the panorama after the first glance to the south. The firing line stretched out before their vision, presenting an awe-inspiring scene.

The shell fire from the German batteries was so terrific that Belgian soldiers and French marines were continually being blown out of their dugouts and sent scattering to cover. The distant town was[50] invisible except for flames and smoke clouds rising above it.

The tide of battle streamed nearer to the wood where the boys had taken shelter. From their high point of vantage they were soon forced to witness one of the most horrible sights imaginable.

A heavy howitzer shell fell and burst in the midst of a Belgian battery, which was making its way to the front, causing awful destruction—mangled men and horses going down in heaps.

Henri was in a chill of horror, and Billy so shaken that it was with difficulty that they resisted a wild desire to jump into space—anything to shut out the appalling picture.

The next instant they were staring down upon a hand-to-hand conflict in the woods, within two hundred yards of the tree in which they were perched. British and Germans were engaged in a bayonet duel, in which the former force triumphed, leaving the ground literally covered with German wounded and dead, hardly a man in gray escaping the massacre.

“I can see nothing but red!” Henri was shaking like a leaf.

Billy gave his chum a sharp tap on the cheek with the palm of his hand, hoping thus to divert Henri’s mind and restore his courage.

Billy himself had about all he could do to keep[51] his teeth together, but, by the unselfish devotion he gave to his comrade, he overcame his fear.

“Come, Buddy,” he pleaded; “take a brace! Easy, now; there’s a way to get out of this, I know there is. Put your foot here; your hand there; steady; we’ll be off in a minute.”

By the time the boys had descended to the lower branches of the tree, Henri was once more on “even keel,” in the language of the aviator.

A long limb of the tree extended out over the road. On this the boys wormed their way to the very tip, intending to drop into the highway, recover their bicycles, and make a dash for safety across the country to the west, following the well defined trail worn smooth by the passage of ammunition wagons.

As they clung to the limb, intently listening and alert for any movement that would indicate a returning tide of battle in the immediate neighborhood, a riderless horse, a magnificent coal-black animal, carrying full cavalry equipment, came galloping down the road, urged to ever increasing speed by the whipping against its flanks of swinging holsters.

“Here’s the one chance in the world!”

Billy swung himself around and leaned forward like a trapeze performer in a circus, preparing for a high dive into a net.

The horse’s high-flung head just grazed the[52] leaves of the big branch, bent down under the weight of the boys.

Billy dropped astride of the racing charger, saved from a heavy fall in the road by getting a quick neck hold, seized the loose bridle reins with convulsive grip and brought the foam-flecked animal to a standstill within fifty yards. This boy had tamed more than one frisky broncho down in Texas, U. S. A., and for a horse wearing the kind of a curb bit in his mouth that this one did, Billy had a sure brake-setting pull.

Henri made a cat-fall into the dusty road and right speedily got the hand-up from his mounted comrade.

Off they went on the trail to the open west, with clatter of hoofs, and the wind blowing free in the set, white faces of the gallant riders.

“I don’t know where we are going, but we’re on the way,” sang Billy, whose spirits now ranged to a high pitch. “This beats anything we’ve rung up yet in our target practice over here,” he gloated. “Isn’t he a jolly old roadster?” Billy had checked the horse to a slow canter, after a run of two miles.

[53]

“Let’s have a bit of a rest.” Henri’s sore shoulder was troubling him. He still had his knapsack with some jumbled food in it. Billy had lost his food supply when he made his leap on the horse.

While the animal was cropping the short grass along the trail the riders took their ease by lounging on the turf and feeding on their crumbled lunch.

“This is a thirsty picnic,” asserted Billy. “My throat is as dry as powder. Let’s see if there isn’t a spring ’round here.”

Hooking the bridle reins over his arm, Billy led the way on a search for water. At the bottom of a wooded hill the boys found themselves in a marsh, and though bitter and brackish the water was a grateful relief to their parched tongues. The horse acted as though he had not had a drink for a week.

A little further on, in a meadow, the boys made a singular discovery. They were amazed to see an important looking personage in a gorgeous uniform, covered with decorations, wandering about the meadow like a strayed sheep.

“What the dickens is that?” exclaimed Henri.

“Give it up.” Billy couldn’t even make a guess. “He shows gay but harmless. I think I’ll look him over.”

On approaching the richly attired wanderer the boys with wonder noticed that he carried a gold-tipped[54] baton and from a shiny knapsack on his shoulders rolls of music protruded.

The strange being kept proclaiming that he was going to direct the German military music on a triumphal parade through the streets of Paris. Henri could understand that much of the disconnected talk, and also that the speaker was the head musician of the German army in Belgium. He had been cut off from his command and become possessed by a fit of melancholy from which the boys found it impossible to rouse him. They divided with him what remained of the contents of Henri’s knapsack, but could not induce him to proceed with them.

“It’s a pity that a man like that should lose his reason. But this dreadful war strikes in most any kind of way, and if it isn’t one way it’s another.”

Henri was still thinking of the horrible happening when the Belgian battery was literally blown to pieces under his very eyes.

“There’s a peaceful sleeper here, anyhow,” said Billy, pausing, as they trudged along, leading the horse toward the trail. He pointed to a little mound above which had been set a rude wooden cross. It was the grave of a French soldier, for on the cross had been placed his cap, showing the name of his regiment. On the mound, too, had been scattered a few wild flowers.

[55]

“Somebody who had a heart for the cause or the fighter must have passed this way,” observed Henri. “The burial of a soldier near the battle lines hasn’t much ceremony, I am told, and surely doesn’t include flowers.”

The boys slept that night in the open, with the saddle for a pillow. They were awakened just before dawn by the restless antics of Bon Ami (“Good Friend”)—for so Henri had named the horse. The animal snorted and tugged at the tether as if scenting some invisible approach through the woods, at the edge of which the three had been passing the night.

Billy and Henri were on their feet in an instant, rubbing their eyes and trying to locate by sight or sound among the trees or elsewhere in the shadowy landscape the cause of Bon Ami’s disturbed action.

Even if the boys had suddenly made up their minds to run to cover, they would not have had time to go very far, for in the instant a scout troop rode out of the woods and straight at them.

The cavalrymen spread in fan shape, and in a moment Billy, Henri and Bon Ami were completely surrounded.

In good but gruff English the ranking officer of the troop commanded: “Come here and give an account of yourselves.”

Billy and Henri made haste to obey, and looking[56] up at the officer on horseback offered their smartest imitation of a military salute. Peering down at them the cavalryman exclaimed:

“So help me, they’re mere boys. Who let you out, my fine kiddies, at this top of the morning? Here, Ned,” calling to one of the nearest troopers, “bring the hot milk and the porridge.”

Billy was becoming slightly nettled at this banter. He had no desire to be taken seriously, but yet not quite so lightly.

“I am an American citizen, sir, traveling, with my friend, on personal business.”

“Will you listen at that now?” laughed the cavalryman whom the first officer had called “Ned.”

“Do you know or have you thought that ‘personal business’ is just now rather a drug on the market in these parts?”

The chief was again addressing the boys, or, rather, Billy, who had elected himself spokesman.

“It does appear that the soldiers have the right of way here,” admitted Billy, “but we came in such a hurry that we couldn’t stop to inquire in particular about the rules.”

“That’s a pretty good horse you have.” It was light enough now for the officer to take in the fine points of Bon Ami. “Where did you get him?”

Billy explained the circumstances.

“Well, you are plucky ones,” commented the officer. “Now,” he continued, assuming again the[57] tone of command, “saddle your steed and fall in.”

The troop wheeled back toward the north and the boys rode stirrup to stirrup with the bluff captain.

At the noon hour the riders reached the field working quarters of the British commander. A small headquarters guard lounged on the grass around the farmhouse that sheltered the general and his staff, a dozen automobiles and motorcycles were at hand and grooms were leading about the chargers of the officers.

The scout troop halted at a respectful distance and dismounted.

“Put on your best manners,” suggested the troop captain as he preceded the boys in quickstep to headquarters.

After a brief conference with an orderly, the boys were ushered into the presence of several officers in fatigue uniform seated at a table littered with papers. At the head of the table was a ruddy-faced man, clean-shaven, with iron-gray hair, to whom all heads bent in deference.

“We have visitors, I see.” The general’s tone and manner were kindly.

The boys stood speechless, their eyes fixed upon the little Maltese badge of honor suspended from the left breast of the general’s coat by a crimson ribbon. It was the Victoria Cross!

“Now, my young men,” said the general, speaking briskly and to the point, “what are you doing here, where are you going, and is there anything else you wish to say?”

As Billy had not as yet opened his mouth, he thought the general was rather ahead of his questions in the last quoted particular.

“Allow me, general, to introduce Mr. Trouville, a native of France, who only lacks the years to vote in America. He has the desire, I assure you. As for myself, I am William Thomas Barry of Maine, United States of America, known as Billy—and together we are known as the Aviator Boys. We are in the flying trade, and with your kind permission we would like to fly now.”

The officers observed the boys with new interest. The London Times had some months ago printed the experiences of a prominent English visitor to America, who had seen these young aërialists in some of their sky-scraping exhibits, and had even taken a short flight with Billy.

“We military fellows are all great for aviation—it’s a big card in this war game”—this observation from the member of staff seated nearest the general—a[59] thoroughbred sort of man who also wore the badge of valor. “And more than that,” he added, “I have a boy of my own in the flying corps of the army.”

It occurred to Billy that this officer might care to hear the sad story of the death flight of the British youth that they had witnessed on the shores of the North Sea.

Billy, in real dramatic style, described the thrilling incident. There was no lack of attention on the part of his listeners; especially did the man who looked like a thoroughbred seem lost to everything else but the tale the boy was so earnestly telling. When Billy produced from the inside pocket of his blouse the photograph and ring that he had taken from the heart pocket and finger of the dead aviator there was strained silence, first broken by the man who had been most intent as a listener.

“It was my boy, my own son!”

This man who had faced shot and shell with never a tremor on many a blackened battlefield, and had won the magic initials “V. C.” after his name, bowed his head in grief and not ashamed of the sob in his throat.

“Some day, God willing,” he softly said to Billy, “you shall guide his mother and me to that resting place.”

A bugle call outside aroused the officers to the[60] grim business of the hour. The roar of another battle would soon be on.

The general turned the boys over to the care of a veteran soldier, a sergeant, with strict orders that they should not be allowed to leave the rear of the brigade about to advance.

Billy and Henri, however, had the opportunity of observing during their first actual army experience, even though of the rear guard, the striking device of a French officer in order to steady his men, in an infantry regiment, called upon for the first time to face the discharge of German shells. For a moment the men hesitated, and even made a slight movement of withdrawal. Instantly the officer seemed to have taken in the situation. The boys heard him shout:

“Halt! Order arms!”

Then, quite coolly, he turned his back upon the enemy—for the first and last time—whipped out his camera, called upon his men not to move, and proceeded to take a leisurely snapshot of his company while shells were falling all around.

The men were astonished, but the officer’s purpose was served. The company was steadied, and the boys, from the top of a supply wagon, watched them go gallantly to work. Sad to relate, the watchers also saw the gallant officer fall soon afterward, struck on the head by a fragment of shell.

“I tell you, General Sherman was right in what[61] he said about war.” Billy was very positive in this expression of opinion.

On that day of fearful fighting the boys saw an entire German regiment perish in the rush of water which swept through the trenches after the Allies had destroyed the dikes; they saw hundreds of men and horses electrocuted on the heavily charged wire entanglements before the trenches.

At nightfall Billy and Henri, heartsick with the horror of it all, crawled under the wagon cover and fought nightmares through the long hours before another day.

It was raining in torrents when the boys peeped through the tear in the wagon shelter early the next morning, and it had turned sharply cold. The roar of the batteries had slackened for the time being, and it was a welcome moment for Billy and Henri, who on the day previous had heard more gunpowder racket than ever they did on all the Fourths of July they had ever known rolled into one.

Stepping out gingerly into the mud, the boys looked around for their friendly guardian, Sergeant Scott. He was nowhere to be seen among the few soldiers in khaki uniforms and woolen caps moving about among the wagons. They soon learned that the sergeant had made a capture during the night of one of the enemy’s secret agents who had penetrated the lines for the purpose of cutting[62] telephone wires. The spy or sniper carried cutters and a rifle. From behind the lines with the rifle he had been shooting at men passing to and fro, but when he ventured inside with the cutters the sergeant nabbed him, though the invader was cleverly disguised in British outfit. Both captor and captive were up-field at an “interview,” from which only the sergeant returned.

When he observed the boys shivering in their tracks, Sergeant Scott called to a teamster to fetch a blanket from one of the wagons. Borrowing a knife from the teamster, the sergeant slashed the big army blanket in two in the middle, doubled each fold and made two slits in the top.

“Jump into these, my Jackies,” he ordered; “shove your arms through. Now you won’t catch a frog in your lungs, and you’re swell enough to make a bet on the races. Come along and tighten your belts with something in the way of rations.”

The boys needed no second bidding, and their belts were very snug when they had finished.

“By the way,” confided the sergeant, “Colonel Bainbridge has taken a heap of interest in you youngsters. His son, I heard, lost his life in one of those flying machines.”

“Yes, we were the ones that told him about it. He’s sure a grand man,” added Billy.

“Well,” continued the sergeant, “there are some of us going to work around toward Lille and the[63] River Lys region to assist in extension of the Allies’ line there. If Colonel Bainbridge commands the movement, between ‘you and I and the gate-post,’ yours truly wants to go ’long.”

“So do we!” The boys spoke as one.

Colonel Bainbridge did command, and Sergeant Scott, Billy Barry and Henri Trouville went along.

“I wish they would let us ride Bon Ami.”

Billy had noted the handsome horse they had captured prancing along carrying a heavyweight cavalryman, while Henri and himself were perched beside a teamster on the front seat of a supply wagon.

“Maybe they were afraid that you would run away,” drawled the teamster. “Sergeant Scott says you’re too skittish to turn loose.”

“The sergeant will be putting handcuffs on us next,” laughed Billy.

The teamster set his teeth in a plug of tobacco, snapped the whiplash over the big bay team and with a twinkle in his eye started the verse of some soldier ditty:

[64]

“That’s just it,” added the teamster, changing from song to the usual drawl, “if the sergeant lets you come to harm the colonel would cut the stripes from his coat. And what’s more the sergeant is kind of struck on you himself. Git-ap,”—to the horses.

It was at the crossing of the Lys at Warneton that the boys had another baptism of fire.

The crossing was strongly held by the Germans with a barricade loopholed at the bottom to enable the men to fire while lying down. The Allies’ cavalry, with the artillery, blew the barricade to pieces and scattered the defenders.

In the square of the town the boys saw the greatest display of fireworks that ever dazzled their young eyes.

One of the buildings appeared to leap skyward. A sheet of flame and a shower of star shells at the same time made the place as light as day.

Out of the surrounding houses the Germans poured a terrific fire from rifles and machine guns.

The Allies’ cavalry got away with a loss of eight or nine men, and Sergeant Scott headed volunteers[65] that went back and carried away wounded comrades from this dreadful place.

Billy and Henri rushed at the sergeant when he returned from this daring performance and joined hands in a sort of war dance around their hero.

“The Victoria Cross for yours, old top!” cried Billy.

“You ought to have it this minute!” echoed Henri.

“Quit your jabber, you chatterboxes,” said the big sergeant playfully, shaking his fist at his admirers, but it could be plainly seen that he was mightily pleased with the demonstration.

“You and I will have to do something to keep up with this man,” remarked Billy to Henri, with a mock bow to the sergeant.

“None of that,” growled the sergeant, “your skylarking doesn’t go on the ground, and not on this ground, anyhow.”

But the boys had grown tired of being just in the picture and not in its making.

“The sergeant doesn’t seem to think that we have ever crossed a danger line the way he coddles us.” Billy was ready for argument on this point.

“Wish we had him up in the air a little while,” said Henri, “he wouldn’t be so quick to dictate.”

It was in this mood, during the advance and on the night of the next day, that the boys eluded[66] the vigilant eye of the sergeant long enough to attempt a look around on their own account.

In the dark they stumbled on the German trenches.

Billy grasped Henri’s arm and they turned and made for the British lines, as fast as their legs could carry them, but the fire directed at them was so heavy that they had to throw themselves on the ground and crawl.