Frontispiece.

Pelham Pinx.

LADY JULIANA PENN.

Madam,

I have ever deemed it one of the most favourable circumstances of my life, that your Ladyship condescended to honour my early youth with your kind countenance and protection. Your amiable character, and exemplary virtues, have always thrown such a lustre around you, as could not but enlighten and improve those, who came within their influence. This testimony from me, is no more than the just tribute of a grateful heart.

I am, therefore, happy, in having your Ladyship's permission to inscribe to you the following discourses. You are no stranger to the sentiments they contain: you love and honour the doctrines they inculcate.

The author intreats to be indulged with a continuance of that regard, which your Ladyship hath hitherto shewn him; and which he hath always held more desirable, in proportion as he hath been better qualified to judge of what is truly honourable and estimable in the intercourses of social life.

With this sentiment deeply impressed upon his mind, he cannot but rejoice in the opportunity your Ladyship hath granted him, of thus publickly subscribing himself,

Madam,

Your Ladyship's

Most obliged and

Most faithful Servant,

J. DUCHÉ.

The following discourses were preached in the united Churches of Christ Church and St. Peter, in the City of Philadelphia, of which the author was appointed assistant minister in the year 1759, and to the rectorship of which he was elected in the year 1775.

The reader will find in them no display of genius or of erudition. To the former, the author hath no claim: of the latter, he contents himself with as much as is competent to the discharge of his pastoral duty. His divinity, he trusts, is that of the Bible: to no other Standard of Truth can he venture to appeal. Sensible, however, of his own fallibility, he wishes not to obtrude his peculiar sentiments; nor to have them received any further, than they carry with them that only fair title to reception, a conviction of their truth and usefulness. From his own Heart he hath written to the Hearts of others; and if any of his readers find not THERE the Ground of his doctrines, they are, surely, at liberty to pass them by, if they do it with Christian Candour, and to leave it to time and their own reflections, to discover that Ground or not.

Universal Benevolence he considers as the Sublime of religion; the true Taste for which, can only be derived from the Fountain of Infinite Love, by inward and spiritual communications. The mind, that is possessed of this true Taste, whatever its peculiarity of opinion may be, cannot be very "far from the Kingdom of God."—"God is Love; and he that dwelleth in Love, dwelleth in God, and God in him." One transgression of the great Law of Love, even in the minutest instance, must appear more heinous in the Sight of the God of Love, than a thousand errors in matters of doctrine or opinion.

If the reader peruses these volumes under the influence of such sentiments, it is not likely, that he will be offended with any singularities of diction, or any inelegant and colloquial expressions he may now and then meet with. Much less will his censure be incurred by the constant use of Scriptural Ideas, and Scriptural Language, in preference to what are called Moral and Philosophical. Deviations from the Simplicity of Evangelical Truth, have too often been occasioned by deviations from the Simplicity of Evangelical Language. A Christian ought never to be "ashamed of the Gospel of Christ which is the Power of God unto Salvation," but should always speak of Christian Truths by Christian Names.

The revisal and correction of these discourses have relieved the author's mind from much of that anxiety and dejection, which a long absence from his family and his churches had occasioned. And he is now happy in the thought, that these volumes will ere long reach his native country, and revive the memory of his labours of love among a people, with whom he enjoyed a reciprocation of kindness and affection, which for eighteen years had known no abatement or interruption.

He most gratefully acknowledges the kind and honourable reception he hath met with since his arrival in England; the chearfulness and generosity with which persons of all ranks have honoured his publication; and the affectionate zeal of his friends, relations, and connexions, in undertaking and completing his subscription, without giving him the trouble of soliciting a single name.

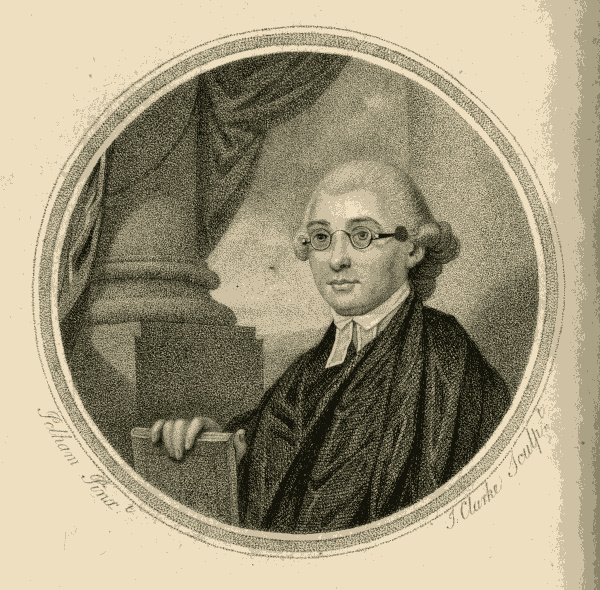

To his most ingenious and worthy Friend and Countryman, Benjamin West, Esq. History Painter to his Majesty, he is happy to acknowledge himself indebted for the elegant designs, taken from two of his most capital paintings, which are placed as frontispieces to these volumes.

To his dear and valuable friend, the Author of the late accurate and elegant Translation of Thomas à Kempis, he is sincerely thankful for his kind and chearful advice and assistance, in conducting the whole publication, to which the author's inexperience in printing, as well as his frequent and necessary absence from the press, would have rendered him altogether unequal.

He hath only to add, that the revisal and publishing of these discourses was undertaken at the instance of some of the most respectable names in the list of his subscribers to the first edition, under whose kind patronage, and in hopes of every indulgence from the candour of the publick, he hath ventured to send them abroad.

Hampstead, 1st March, 1780.

The Character of Wisdom's Children.

St. Luke, Chap. vii. Ver. 35.

"But Wisdom is justified of all her Children."

Evangelical Righteousness.

Jerem. Chap. xxiii. Part of Ver. 6.

"And this is his Name, whereby he shall be called, The Lord our Righteousness."

The Religion of Jesus, the only Source of Happiness.

St. John, Chap. vi. Ver. 66, 67, 68.

"From that Time many of his Disciples went back, and walked no more with him. Then said Jesus unto the Twelve, Will ye also go away? Then Simon Peter answered, Lord, to whom shall we go? Thou hast the Words of Eternal Life."

True Religion, a costly and continual Sacrifice.

2 Samuel, Chap. xxiv. Ver. 24.

"And the King said unto Araunah, Nay, but I will surely buy it of thee at a Price: neither will I offer Burnt-Offerings unto the Lord my God, of that which doth cost me nothing."

Truth, the only Friend of Man.

Galatians, Chap. iv. Ver. 16.

"Am I therefore become your Enemy, because I tell you the Truth?"

The Strength and Victory of Faith.

1 John, Chap. v. Ver. 4.

"Whatsoever is born of God overcometh the World: and this is the Victory that overcometh the World, even our Faith."

Faith Triumphant over the Powers of Darkness.

St. Mark, Chap. ix. Part of Ver. 24.

"Lord, I believe: Help thou mine Unbelief!"

The flourishing State of the Righteous.

Psalm i. Ver. 3.

"He shall be like a Tree planted by the Rivers of Water, that bringeth forth his Fruit in his Season: His Leaf also shall not wither, and whatsoever he doth shall prosper."

The Cause and Cure of the Disorders of Human Nature.

St. Mark, Chap. vii. Ver. 34.

"And looking up to Heaven, he sighed; and saith unto him, Ephphatha! that is, Be opened."

The Riches, Privileges, and Honours of the Christian.

1 Cor. Chap. iii. Ver. 21, 22, 23.

"Therefore let no Man glory in Men: for all Things are yours; whether Paul, or Apollos, or Cephas, or the World, or Life, or Death, or Things present, or Things to come; all are yours: and ye are Christ's, and Christ is God's."

Christ, known or unknown, the Universal Saviour.

St. John, Chap. xiv. Part of Ver. 9.

"Have I been so long Time with you, and yet hast thou not known me, Philip?"

Human Life, a Pilgrimage.

Psalm xxxix. Part of Ver. 12.

"For I am a Stranger with thee, and a Sojourner, as all my Fathers were."

The true Knowledge of God internal and practical.

Job, Chap. xlii. Ver. 5, 6.

"I have heard of thee by the Hearing of the Ear; but now hath mine Eye seen thee: therefore I abhor myself, and repent in Dust and Ashes."

On the Nativity of Christ.

St. Luke, Chap. ii. from Ver. 6, to 20.

"And so it was, that while they were there, the Days were accomplished, that she should be delivered," &c.

St. Luke, Chap. vii, Ver. 35.

"But Wisdom is justified of all her Children."

If we take an impartial view of the sentiments and conduct of mankind with respect to religion, we shall find, that their errors in speculation, as well as in practice, originate, for the most part, in the will; that their understandings are blinded by their passions, and that their ignorance of truth too often proceeds from their aversion to goodness.

To combat this prevailing depravity of human nature, and to strike at that root of evil which we bring with us into the world, was the grand and principal design of all those different dispensations, by which Heaven hath condescended, from time to time, to speak to the sons of men. Instead, however, of yielding a grateful attention to this benevolent purpose, they have, in some instances, wholly rejected, and, in others, perversly misconstrued, the dispensations themselves. Whether "God spake at sundry times, and in divers manners, in times past, unto the fathers by the prophets;" or, whether he spake, as in these latter days, to the children, by his own Incarnate Son; the generality of men have either been deaf to the salutary message, or have availed themselves of some idle pretexts to elude a compliance with its most serious and solemn contents. Hence arose the inattention and opposition of ancient unbelievers, to the missions of patriarchs and prophets; and hence it is, that infidels of later ages have called in question the truth and authority of that most full and complete Revelation of the Divine Will, with which mankind have been favoured by the ministration of the Blessed Jesus. Far, however, from resenting their obstinacy, or indignantly with-holding from them any further communications of Divine Light, the great God and Father of Spirits hath still persevered in carrying on the purposes of his Love; and, "whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear," still seeks, by a variety of dispensations, to gain possession of the hearts of his creatures. Notwithstanding, therefore, the general indifference and obstinacy that have prevailed, there have not been wanting, in every age and nation, some docile virtuous minds, who have listened to the Heavenly Voice, and received with gratitude the instructions of that "Wisdom which is from above;" and who, as her true children, have vindicated her ways to man, and admired and justified the different methods by which she manifests herself to different souls.

The truth of these observations we find remarkably exemplified in that conduct and behaviour of the Jews, and particularly of the sect of the Pharisees, which is mentioned in the verses preceding my text, and which indeed gave rise to the pertinent and beautiful maxim there expressed.

Ignorant of the spirit of that dispensation under which they lived, and perversely attached to those externals of their religion, that most gratified their pride and selfishness, they seem to have been equally offended with the doctrines and manners of John the Baptist, and those of the Blessed Jesus. And though the grand object of the Master and his Forerunner was one and the same, even the reformation of the heart and life; and though the outward means, however inconsistent they might appear, were but different parts of the same spiritual and redeeming process; yet these degenerate Israelites sought to stifle the power of conviction in their breasts, by childishly objecting to the abstracted, severe, and rigorous life of the Baptist on the one hand, and the easy, open, and condescending behaviour of Jesus on the other; insinuating, that the former was only the effect of a gloomy, dark, and diabolical spirit; and that the latter shewed a familiarity and levity, unworthy the character of a prophet sent from God.

Our Blessed Lord exposes the weakness and inconsistency of these objections, by the following apt and lively similitude: "Whereunto shall I liken the men of this generation, and to what are they like? They are like unto children sitting in the market-place, and calling one to another, and saying, We have piped unto you, and ye have not danced; we have mourned unto you, and ye have not wept." That is to say: We have taken every method we could devise to engage your attention, and to prevail upon you to bear a part in our recreations; but you have unkindly and sullenly refused to come. We have endeavoured to adapt our little sports and exercises to what we conceived might be your particular taste and humour; but still we have failed of success.

In application of this allusion, our Lord proceeds—"For John the Baptist came neither eating bread, nor drinking wine; and ye say, He hath a devil." The austerity of the Baptist's life, which was meant to inculcate a lesson of self-denial, and abstraction from the follies and vanities of a worldly life, as well as a solemn preparation for the happiness of an heavenly one, ye maliciously declare to have proceeded from the melancholy suggestion of some dark and evil spirit, that hurried him into the desart, and secluded him from all affectionate intercourse with men. On the other hand, because "the Son of man is come eating and drinking, ye say, Behold a gluttonous man, and a wine-bibber, a friend of publicans and sinners!" To answer the great purposes of Divine Love, I have, with condescending freedom, mingled with all ranks of people; put myself in the way of the giddy and the profligate, and even accepted the invitations of publicans and sinners. For this, without knowing the motives of my conduct, you have vilified me with the opprobrious names of glutton and drunkard; and insinuated, that the friendly attention I shewed to men of their character, proceeded not from a regard to their souls, but from a fondness for their vices. But notwithstanding your blindness and obduracy, notwithstanding your weak and wicked misconstructions, be assured, there are those, who can do justice to these dispensations of Heaven, whose minds, illuminated from above, can discern the beauty, propriety, and uniformity of design, which Wisdom manifests in these various methods of addressing herself to the sons of men. Such children of Wisdom are abundantly convinced, that the self-denying life of the Baptist was necessarily preparative to that meek, gentle, condescending Life of Love, which I have inculcated in my precepts, and recommended and enforced by my example; and that both these are the happy effects of that Redeeming Power, which I manifest in the hearts of those, who, with simplicity and self-abasement, receive and gratefully acknowledge my spiritual salutary visits. "But Wisdom is justified of all her children."

The truth was this: the Pharisees considered the severe exercises of John, his contempt of the world, and total disregard of the pleasures and honours of life, as a personal censure of their hypocritical pretensions to religion, by which, under the appearance of great zeal for the external and ceremonial parts of the law, they "sought the praises of men, more than the praises of God." In like manner, the humility and condescension of Christ, his free and affectionate intercourse with all ranks of people, even with those, whom (on account of their ignorance of some minute traditionary precepts of their Rabbins) they held accursed, were a perpetual impeachment of their intolerable pride and arrogance, and most effectually tended to lessen their credit and reputation with those whom they wished and earnestly sought to engage for their pupils and admirers. No wonder, then, that whilst they continued thus attached to favourite passions and prejudices, they should wilfully misconstrue the purest intentions, and vilify the fairest actions of those, who attempted to combat and expose them. Their objections to the person and doctrines of Christ, as well as to those of his illustrious Harbinger, came rather from their wills than their understandings: nor would they ever have called in question the Divine authority of their missions, had not the design and spirit of them militated against their own evil tempers and dispositions: "Light was come unto them; but they chose darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil."

In every age of the world, and under every dispensation of religion, human nature, in itself, has always been the same. The serpentine subtilty of human reason, when engaged in the service, and acting under the influence of vice and error, will never be at a loss for arguments to support their cause against the voice of truth and virtue. Hence the specious objections, which modern infidelity hath thrown out against the necessity of Divine Revelation; and hence the weak and idle censures, which libertinism on the one hand, and false enthusiasm on the other, so illiberally denounce against the sincere, honest, and cordial votaries of true Christianity.

Sincerely to be pitied is the poor unbeliever, whose short-sighted reason, incapable of seeing further than the externals of Christianity, furnishes him with some plausible objections, that seem to weaken its outward evidence, but cannot reach the spirit and power by which it is animated and supported. "Christianity was instituted for the common salvation of all men: its essential truths, therefore, are plain and obvious, level to every capacity, and stand in no need of learned labour to inculcate and explain them; they are rather matter of feeling, than of reasoning.

"Whatever is within, whatever is without us, calls aloud for a Saviour. Change, corruption, distemperature and death, have, by the sin of fallen angels, and of fallen man, been unhappily introduced into this system of things which we inhabit. The whole creation groaneth; and animals and vegetables, and even the Immortal Image of God himself in man, are all in bondage to their malign influences; so that every thing cries out, with the apostle Paul, "Who shall deliver me from this body of death?" so that every thing cries out, with the apostle Peter, "Lord, save me, or I perish!"

"What kind of a Saviour then is it, for whom all nature thus cries aloud, through all her works? Not a dry moralist, a legislator of bare external precepts, such as some would represent Christ to be: no, the existence and influence of the Redeemer of Nature, must, at least, be as extensive as Nature herself. Things are defiled and corrupted throughout; they are distempered and devoted to death, from the inmost essence of their being; and none, but He alone, "in whom they live, and move, and have their being," can possibly redeem and restore them."

These are inevitable truths, which all men, at some time or other, must feel, and feel deeply too, whether they attend to them now or not. The redemption and restoration of every sinner can be accomplished in no other way, than by Christ's spiritual entrance into his heart, awakening in him an abhorrence of evil, and a love of goodness.

This is the spirit of the Gospel of Jesus; this the grand purpose of Heaven, under every dispensation of Revealed Truth, from Adam down to this day. The modes of communication, the outward forms of worship and of doctrine, may vary; but the same spirit runs through the whole, and the enlightened eye of "Wisdom's children" can see and adore her radiant footsteps, in paths that appear dark and dreary to the eyes of others. However her outward garb may change; whatever different appearances she may put on, under the patriarchal, legal, and evangelical dispensations; her real features, her whole person and employment, have ever been invariably the same. These different appearances were only adapted to the different circumstances of men, and calculated to direct their attention to the one great and principal object she has always had in view, even the Redemption of immortal spirits from the tyranny of earth and hell, and the full restoration of them to their primeval innocence and bliss.

Turn then, ye advocates of infidelity! O turn back from those delusive dangerous paths, into which the false light of fallen reason hath led your wayward steps. Wisdom herself, and all her true and Heaven-born children, lift up their sweet and instructive voices, and press you to return; to recognize your illustrious origin; to spurn the transitory and polluting joys of earth, and to aspire after the pure and permanent pleasures of Heaven! From the Throne of the Most-High, the center of her enlightened kingdom, she speaks, she illuminates, she warms every intelligent being that turns to her benignant ray: the darkness of nature kindles, at her approach, into the Light and Life of Heaven; every evil principle, every evil passion, shrinks from before her, and retires to its native hell; whilst the spirits of her redeemed children issue forth from their long captivity, and triumphantly re-enter the realms of purity and peace.

Who would not wish, then, to become a votary, a pupil, a child of Wisdom? But how is this privilege to be obtained? what path must we pursue, that will lead us to her delightful mansion? what conduct must we observe, that will entitle us to be members of her illustrious household? Must we put on the raiment of camel's hair, and the leathern girdle; follow the mortified Baptist into the desert, and feed upon locusts and wild honey? Or must we not rather adopt the gentler manners of the Holy Jesus, mix with the world as he did, and chearfully employ ourselves in acts of kindness and brotherly love?

It is evident from the whole passage of Scripture, of which my text is part, that our Lord blames the Jews no less for their disregard of the ministry of John, than for the contempt with which they treated himself; and plainly intimates, that, by the Children of Wisdom, we are to understand all those who see the Baptist's ministry in its true point of view, viz. as introductory and preparatory to his own; and in consequence of this are fully convinced, that the chearfulness of Faith, and the sweetness and condescension of Love, must naturally be preceded by the severity of Repentance, and the salutary bitterness of sorrow and contrition.

"Repent ye, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand," said the Harbinger of the Son of God: "The Kingdom of God is come; he that believeth shall be saved;" said the Son of God himself. "Repentance, therefore, and Faith working by Love," are the sure characteristics of Wisdom's Children.

It is not, therefore, any distinguishing peculiarity of the Baptist's character, the outward garb, or the outward deportment, that we are to assume, but an inward temper and frame of mind corresponding to both. A deep sensibility of the evils and infirmities of our fallen nature, an heart-felt conviction of the guilt and misery of sin, and a penitential sorrow for our own numberless lapses and deviations from the path of virtue, are the true Harbingers of Christ in our hearts. When, under their powerful ministration, we find ourselves called, not perhaps to a life of outward solitude and mortification, but of inward retirement and abstraction from the world; in the language of Scripture, "we repent, we are converted:" we turn our backs upon every gay and glittering scene, which worldly honour, wealth, or pleasure, can exhibit; we find nothing in any of them, that can give a moment's real peace or rest to our "weary heavy laden" souls; we are humbled to the dust; we feel ourselves, as "worms, and not men," as "less than the least of God's mercies."

In this mortified, penitent, and afflicted state, which is mercifully intended to bring us to a proper sense of our helplessness by nature, and of the indispensable necessity of Divine Supernatural assistance, we must remain, till the happy effect is produced, and till God is graciously pleased to call us out of the wilderness. The Harbinger then hath fulfilled his office; "The Lamb of God" appears "to take away the sins of the world;" "The kingdom of heaven is come" into our hearts. To sorrow and disquietude, succeed sweet peace and heavenly composure of mind: the understanding is enlightened; the will receives a new and happy direction; a new principle animates our whole frame, a new conduct appears in our whole life and conversation: the Spirit of Love breathes and acts in every duty we are called to perform, in every little office, which common civility and politeness requires us to do, even to those, who have yet no taste or desire for the sublime comforts of religion.

Thus it is, that Wisdom is justified of all her Children; and thus it appears, that the Religion of the Gospel, which is the only True Wisdom, is a Religion of Love. A Life of Love, therefore, is the best, the only evidence, which its disciples can give, of the sincerity of their profession; and the surest method they can take of recommending it to others. "Let your light, then, so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in Heaven."

Jeremiah, Chap. xxiii. Verse 6.

"And this is his Name, whereby he shall be called, the Lord our Righteousness."

The great and essential distinction betwixt the legal and evangelical dispensation, is accurately pointed out by the Apostle, where he tells us, that "the law is but the shadow of good things to come, and not the very image of the things." Its types, ceremonies, and outward ordinances, are taken from the objects of temporal nature, which are, at best, but shadowy representations of Eternal Truth. "The comers thereunto could never be perfected," by the most minute observation of its external rites. The pious, spiritual Jews, therefore, must have looked further than these, and considered every outward purification, as figuratively expressive of an inward cleansing to be performed in their hearts.

Moses, their inspired Legislator, and the prophets that succeeded him, did not fail to acquaint them with the immediate and necessary reference of these temporal symbols to Spiritual and Eternal Truths. Nevertheless, it appears but too evident, from the whole Jewish history, that the generality rested their hopes of salvation, merely upon their outward law: "They went about to establish a righteousness of their own," founded upon a strict observance of the Levitical ceremonies, which were only adapted to their present circumstances, without paying the least attention to that Inward Law of Righteousness, to which these ceremonies referred.

Hence it was, that their prophets were directed by the Most High, to express, in the strongest terms, his disapprobation of those very ordinances, which he himself had originally instituted for their good; and to tell them, that "he had no pleasure in their burnt-offerings and sacrifices, that their oblations were vain, and that incense was an abomination in his sight." His displeasure was not with the ordinances themselves; for, if considered and observed with proper views and dispositions, they would have been subservient to the most glorious purposes: but he was offended with the gross and flagrant abuses of them, which the people were daily committing.

Hence also it was, that the same inspired prophets, when the hand of the Highest drew aside the curtain of futurity, and exhibited to their astonished view the successive displays of Gospel Light and Truth, with all that variety of heavenly scenery, which his Incarnate Son was to open upon our benighted world; hence it was, I say, that the same inspired prophets were particularly careful to distinguish the new dispensation, by every figure and mode of expression, that might lead the most dark and ignorant Jew to consider it as internal and spiritual.

The righteousness of the new covenant is widely different from what the carnal Israelite apprehended to be the righteousness of the old. With respect to their essence, their foundation, their motives and ends, both covenants are the same, differing only in the external mode of revelation; the old being "the shadow," the new "the image of good things to come;" the old, pointing to Christ; the new, revealing him in all his fulness to the faithful.

Christ Jesus, therefore, is and must be, "the end of the law to those that believe;" that is, he is and must be, in himself, that very Righteousness to which the law pointed, but which it could not attain. "As a school-master," it served to instruct its ignorant, dark, and fallen pupils, in the outward rudiments of Divine Truth; but could never communicate to them the Light, Life, and Spirit of that real Evangelical Righteousness, which is only to be found in the Incarnate Word of God.

It is for this reason, that the prophet, speaking of the approaching kingdom of the Messiah, in whom all the law and the prophets were to center, represents him as "a righteous branch springing forth from the root of David; as a king, reigning, prospering, and executing judgment and justice on the earth;" in consequence of whose mild and equitable administration, "Judah should be saved, and Israel should dwell safely:" and, as the most characteristical designation of his nature and office, tells us, that "This is his Name, whereby he shall be called, The Lord our Righteousness."

Let us then enquire, in the first place, why our Blessed Redeemer has the name of Righteousness ascribed to him by the prophet; and secondly, what we are to understand by his being called "our Righteousness."

I. A name in Scripture is generally put to express the intrinsic nature and qualities of the object named. When, therefore, the name of the Messiah is here said to be "Righteousness," we must necessarily conclude, that Righteousness is his very nature, his essence, the substance of all his attributes and perfections. He is not called righteous, but Righteousness itself; the source and fountain, from whence all that is really and truly righteous, throughout the universe, perpetually proceeds.

Jesus Christ is "the Brightness of the Father's Glory, and the Express Image of his Person." All the beauties, excellencies, powers, and virtues, which are essentially hidden in the invisible Godhead, are substantially, vitally, inwardly, as well as outwardly, opened, revealed, and illustriously displayed, in the person of the Incarnate Jesus. "All things were made by him, and without him was not any thing made, that was made:" all the "thrones, dominions, principalities and powers," possessed by angels, archangels, cherubim and seraphim, are derived from him; for, "in, and through him, did the Father create all things." The highest degree of Righteousness which the highest Seraph can attain, is but a beam or efflux from this Eternal Sun. With glory undiminished he perpetually imparts spiritual life and vigour to all those countless myriads of intelligences, which inhabit the whole compass of universal nature. He is himself the living law, the eternal rule of order and rectitude. God the Father hath "set this his King of Righteousness on his holy hill of Sion." Every outward institute, revealed and written, which God hath "at sundry times and in divers manners," delivered to the sons of men, was but a transcript of that original law, which lives for ever in the heart of Christ. "I am the way, the truth, and the life;" "no man cometh unto the Father, but by me; ye will not come unto me, that ye may have life; without me, ye can do nothing—" are his own blessed words.

Nature, without this Christ of God, is impurity, emptiness, poverty, want, and wretchedness extreme: nature illuminated, enriched, refreshed, glorified by him, is holy, righteous, lovely, supremely happy. Known or unknown to our fallen race, it is He alone, who inspires every good thought, every righteous deed, every sentiment and action that is amiable and endearing.

In the acts of the apostles we read of an altar with this inscription, "To the unknown God!" St. Paul, taking occasion from this circumstance, tells the Athenians, "Him whom ye ignorantly worship, preach I unto you." In the whole frame of nature, says a truly sublime writer, every heart, every creature, every affection, every action, is an altar with the same kind of inscription, "To the unknown Beauty!—To the unknown Righteousness!—To the unknown Jesus!" This is the eternal standard of truth, order, righteousness and perfection, to which every being in nature ignorantly moveth; this is that which all understandings, all hearts, cannot but admire and adore. But blessed above all beings are those, whose hearts are spiritual altars, with the righteous person of Christ engraven upon them by the finger of God, flaming with the fire of Heavenly Love, and bearing this radiant inscription, "To the known and experienced Beauty and Righteousness of that Jesus, whom we know; that Word of Life, which our eyes have seen, our ears have heard, our hands have handled, and spiritually embraced!" And this leads me, in the second place, to inquire what we are to understand by Christ's being called "Our Righteousness."

II. Under my first head, I observed to you from Scripture, that God created all things "in and by Jesus Christ;" and that "without him, was not any thing made that was made." Man, in particular, was "created in the Image of God:" Christ is "the Brightness of the Father's Glory, and the Express Image of his Person:" and, therefore, man was created in Christ.

Man in himself, in his outward nature, was but an empty vessel, till the Christ of God became his fulness and perfection. His outward form was from the dust of the earth; but his inward spirit was the breath of the Most High. The Image of God, even Christ himself, was his first, his sole Righteousness and perfection; the infallible instructor and enlightener of his understanding, the unerring guide and director of his will. The Name by which the Son of God was known to him, was "The Lord his Righteousness." Angels themselves know no other Righteousness, than the Righteousness of God in Christ.

The fall of man, or "Original sin," (as our church article with great truth and propriety expresses it) "is the fault and corruption of the nature of every man, that naturally is engendered of the offspring of Adam; whereby man is very far gone from original righteousness, and is of his own nature inclined to evil." We have already seen what this original righteousness was, which man possessed in a state of innocence, viz. that it was Christ, "the Lord his Righteousness," in him. This is what Adam lost—This is what Christ alone can restore.

Man in his present fallen state, without Christ, must be naturally inclined to evil; he has no righteousness of his own. And he can no more be saved by any exertion of his own natural powers, than he can see by the utmost stretch of his organs of sight, without the light of the sun.

Here then a serious and inquiring mind may be ready to ask—How is this Blessed Redeemer to become my Righteousness? I feel the force of these Scripture truths you have mentioned, and experience in my soul the dreadful consequences of an original apostasy—But I know not, whether Christ is my Righteousness, or not. I know not, whether I have the least traces of his Righteous Image in my soul.

"Hath Christ, then, been so long time with thee, and yet hast thou not known him?" Every little rebuke of conscience; every emotion of kindness, tenderness, and love; every sympathetic feeling of the prosperity or distress of thy neighbour; every sensibility of admiration, esteem, and joy, from contemplating a truly wise and virtuous character; every fervent desire of imitating what is good and excellent in others; every weak aspiration after holiness and perfection; nay, every little feeling of the restless cravings of thine own nature, every little longing after happiness unpossessed; all, all is Christ, speaking within thee, and waiting and watching to reveal himself in Righteousness to thy soul. Nothing, therefore, is wanting, on thy part, but a calm and quiet resignation of thyself, and all that is within thee, to his sovereign disposal, to redeem, purify, and restore, to do every thing that is necessary to be done, and which he alone can do, for thy salvation.

Thus have I endeavoured to give the plain and obvious meaning of the text. Distinctions upon distinctions have been multiplied; books upon books have been published, to tell us that we are to be justified by the Personal Righteousness of Christ outwardly imputed, and sanctified by the inherent graces of the Holy Spirit; that one must necessarily precede the other; and that we must be perfect in Christ by Justification, before we can have the least spark of Holiness by Sanctification. This is, indeed, travelling in the broad and popular road; and such kind of preaching might be to the "praise of men." Let systems be written upon systems, and comments upon comments; let preachers oppose preachers, and hearers wander after this or that form of godliness; but may Heaven in mercy preserve us from taking up our rest, or placing our dependence upon any thing less than an intimate and experimental knowledge of "The Lord our Righteousness" revealing himself, with all his holy heavenly tempers, virtues, and dispositions, in our hearts! May we never rest satisfied with a nominal profession of Christianity, a nominal acquaintance with Christ, or a nominal remission of sins; for, surely, we are not warranted, by Scripture, to look upon ourselves as redeemed by Christ, and born again of him, till by a total purification, a complete deliverance from all the evil tempers and passions of our fallen life, he hath obtained a full and peaceable possession of our whole nature, erected his Throne of Righteousness in our hearts, and by the effectual working of his Holy Spirit brought us to the "measure of the stature of that Fulness, which is in Himself."

St. John, Chap. vi. Ver. 66, 67, 68.

"From that time, many of his Disciples went back, and walked no more with him. Then said Jesus unto the Twelve, Will ye also go away? Then Simon Peter answered him, Lord! to whom shall we go? Thou hast the Words of Eternal Life."

Happiness is the great end and aim of all those restless pursuits in which mankind are perpetually engaged. The laborious peasant, and the contemplative philosopher; the man that wisheth for wealth, and the man that possesseth it; the gay votary of worldly pleasure, and the gloomy tenant of the solitary cell, are alike industrious in exploring this hidden treasure. Their imaginations are ever upon the stretch after this something yet unknown. Their ideas of happiness indeed, as well as the means which they make use of to attain it, are as different as their prevailing tempers and inclinations. Whatever objects coincide with their present conceptions, those they esteem, and those they pursue, with all the eagerness of newly awakened desire. Deluded, however, by specious appearances, mistaken again and again in their choice of objects, loathing to-day what they pursued yesterday with ardour, chearful and confident in prospect, disappointed and melancholy in possession, they fondly rove from one scene of imaginary bliss to another, unable to rest on any with permanent satisfaction. They never once consider, that no finite objects can fill up the immense void of an immortal soul, no temporal enjoyments satisfy its boundless desires; and that nothing less than "life eternal" can afford an happiness commensurate to its eternal nature.

This is not mere theory, or empty speculation. There is not one in this assembly, but could bear witness from experience to the melancholy fact. Was each of us to be asked, in a serious and solemn manner, Are you really happy? very few, I am afraid, if they would speak ingenuously, could answer in the affirmative. And yet, perhaps, most of us have attained, from time to time, what we once deemed the height of our wishes; and what we were then sure, if attained, would make us completely happy.

The child wishes for the employments and pleasures of youth; the youth longs to arrive at what he calls the freedom and independence of manhood; the man anxiously schemes and plots, and contrives, and labours and toils, and then wishes to see the success of his schemes, the accomplishment of his labours. His schemes turn out to his satisfaction; the end is obtained; the object is enjoyed: his bliss is consummate, to be sure; he cannot be happier—No such thing—New wants succeed; new schemes are formed; new pursuits, new labours, new anxieties and wishes, tread close upon each other's heels. But where is his happiness all the while? Why he loses sight, at last, of the grand and principal object, in the pursuit of which he had set out: failing of success in this, he foolishly adopts the means for the end; and perpetual care, toil, and vexation, are the wretched effects of his mistaken choice.

Thus, for instance, the covetous man grasps, and saves, and fills his coffers—for what? Not to make himself, his family, or his poor neighbours round him, happy with the fruits of his penurious efforts. No—he not only turns a deaf ear to the piercing cries of indigence, but grudges even his family the common necessaries of life, and never parts with a farthing, without uttering some ridiculous complaint of the hardness of the times, and their want of economy. He saves therefore for the sake of saving; his heart is shut up in his chest with his beloved mammon, both alike inaccessible to the mild and soft approaches of kindness and liberality.

We cannot but shrink back with horror, from a character so odious and detestable as this. But the observation with which I set out, will hold equally true, when applied to any of those false paths, which men pursue in quest of happiness.

Pleasure and ambition will deceive them, as surely as avarice. Enjoyment in every instance may pall, but cannot satisfy the restless desire. Nor will it ever be satisfied, till the soul gets sight of the only true beatifying object in the universe, to which she can rise, and upon which she can rest, with the whole strength and energy of her immortal nature.

The light of another world, however, must open and irradiate her spiritual senses, before she can have the least glimpse of this supreme source of bliss. The vanity and deception of all creaturely happiness must in some measure be unfolded to her view, before she can stretch one feeble thought towards Heaven; and she must be intimately convinced of the bondage of her fallen life, and the misery of her condition in this fallen world, before she can feel the force, or discern the spiritual depth of these expressions of St. Peter, "Lord! to whom shall we go? Thou hast the words of eternal life."

There are many people, indeed, who though they are walking on in those very paths of error and delusion which I have just mentioned, would fain have their conduct hallowed by some religious appearances. They begin with deceiving themselves, and then go on to deceive others. But, do what they will, they cannot wholly divest themselves of the feelings of truth and virtue. For they have within them a Spiritual Nature, that is continually striving, under the influences of its native Heaven, to get disengaged from the servitude of its corrupt companion. Call it by what name we please, conscience, the light of nature, common sense, common or preventing grace; or, as the Scripture denominates it, "the Light that lighteth every man that cometh into the world, Christ in us the hope of glory, the Incorruptible Seed of the Word of God," (for, as Christians, I think we ought to prefer scriptural to philosophical terms;) I say, call it by which ever of these names we like best, certain it is, that every man at times feels this Divine Power stirring within him, and endeavouring to awaken, reprove, inform, illuminate, and govern his life and actions.

Now it always happens, that the counsels of this Heavenly Monitor clash with and oppose the dictates of corrupt nature. At this contradiction, the passions are alarmed; they demand immediate gratification, and the trembling mortal dares not at once yield to their solicitations. A strong sensibility of the falsehood of their claim, is felt in his breast. Something must first be done, to stifle or quiet this uneasy sensation.

Avarice, he will say to himself, is criminal, it is true; but a well-timed parsimony is virtuous and commendable; and a good and prudent man will think himself in duty bound to provide for the future support of his children.

Sensual pleasure, vain mirth, and jovial company, are not quite consistent with the precepts of the Gospel of Christ: but a few innocent amusements can do no harm; and it is but in character for a Christian to be chearful.

The pursuits of ambition are diametrically opposite to that meekness and humility, which should characterize the disciple of the lowly Jesus: but posts of honour, and exalted stations, may enable a man to be of considerable service to his neighbours, and enlarge his sphere of usefulness.

Thus, every evil temper and inclination, wrath, hatred, revenge, envy, jealousy, &c. may cloath themselves in the garb of virtue. Men may first deceive themselves, by endeavouring to reconcile their criminal pursuits with the dictates of conscience; and then employ the same infernal arts, to deceive and impose upon others. It is with such masks as these, that hypocrites, pharisees, and all pretenders to true religion, step forth upon the stage of life, dare to enlist themselves under the standard of virtue, and even sometimes assume the rank and authority of commanders. But when they are summoned to the field of battle; when they are called upon, from within, or from without, to exert themselves against their spiritual adversaries, to assert the rights of Heaven, as well in themselves as in the world around them, to subdue the evil lusts and passions that tyrannize in their own breasts, or to engage with that bitter and malevolent spirit, who opposes the advancement of their Master's kingdom in the life and conduct of others; then it is, that the traitors drop their masks; they meanly desert the banner of the cross, openly disavow their pretensions to religion, and "deny the Lord that bought them." They shrink from the combat, honourable as it would have been for them to engage, and happy as they would have found themselves in the issue; and meanly barter away their salvation for a false peace, short in its continuance, and ending in woe and misery extreme. Like the cowardly disciples mentioned in my text, "they go back, and walk no more with their Master."

Doubtless these timid Israelites were alarmed at that heavenly discourse of the Blessed Jesus, which we read in the preceding part of this chapter. The mysteries of his kingdom there delivered, were too refined for their gross conception. The nature, nourishment, and growth of the Inward and Spiritual Man, which is there indispensably required, militated too powerfully against their favourite passions and prejudices. Their high-blown hopes of future preferment in a temporal kingdom, were, by this spiritual address, entirely dissipated; and they were taught to seek and expect nothing from their Master, but what was opposite to the life, and spirit, and maxims of this world.

Alas, how many apostates from the religion of Jesus, have imitated the conduct of these unworthy disciples! Past, as well as present times, afford too many melancholy examples of this kind. A temporizing spirit hath prevailed in almost all ages; and ecclesiastical history abounds with examples of its venomous influence upon the minds of men. The temporal prosperity of the church, hath, in many instances, proved its ruin; and accessions of wealth and power have only served to increase its corruptions. Under the profession of a religion, which breathes nothing but purity, meekness, and benevolence, men have been actuated by all the diabolical passions that ever inflamed the breasts of the most ignorant and unenlightened Pagans.

Wherever the external profession of Christianity hath been attended with any outward emoluments, its disciples have increased, and an outward shew of zeal for its advancement, hath not been wanting. This outward shew gives them but little trouble; and the hypocrite's garb, though cumbersome at first, is not only made light and convenient by custom, but even desirable for the profits and advantages it brings.

Whilst the Blessed Jesus is distributing his bounty, and loaves and fishes multiply under his creating hand, he will never be without crouds of followers to partake of his royal munificence. Whilst he is riding in triumph through the streets of Jerusalem, nothing is heard from every quarter, but "Hosannahs to the Son of David;" every one is ambitious of joining his train, and of being in the number of his adherents. But when the powers of this world confederate against him; when Herod and Pontius Pilate, and the whole nation of the Jews, rise up in arms, seize upon the innocent victim, and drag him to condemnation, torture and death; then, indeed, his false friends appear in their proper colours; and, O melancholy truth! even his disciples "go back, and walk no more with him;" some of them deny him, and all fly and forsake him.

Let us not deceive ourselves, my brethren. It is not an outward profession of Christianity, or an outward zeal against its adversaries, that will stand us in any stead: all this may well enough consist with inward impurity, a worldly spirit, and an heart devoted to the service of sin. The great trial of our faith, the sure proof of the sincerity of our conversion, must be sought for in deeper exercises than these.

When storms arise, when dangers threaten, when inward and outward enemies attack our peace; when we cannot maintain our discipleship without the sacrifice of some darling passion of almost irresistible power; when we can walk no longer with our Master, without the loss of some considerable temporal advantages; when we are summoned by him to fly from the soft allurements of pleasure, to burst the bonds of avarice or ambition, to disclaim all dependence upon the world, ourselves, or any created being; in a word, "to forsake all, take up our cross, and follow him;" then, indeed, is our hour of trial! then the sincerity of our attachment to Christ, will be made manifest to ourselves, and to the world; and we shall learn to know assuredly, whether we are, or are not, of the number of those disciples, "who go back, and walk no more with him."

Therefore, O Christian, thy Beloved is then only thine, and thou art then only his, when thou canst abide with him in the darkness of the vale, as well as in the splendors of the mount; when thou canst walk with him in the wilderness, as well as on the plain; and when "neither tribulation, nor distress, nor trial, nor persecution, can separate thee from the Love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord."

St. John, Chap. vi. Ver. 66, 67, 68.

"From that time many of Disciples went back, and walked no more with him. Then said Jesus unto the Twelve, Will ye also go away? Then Simon Peter answered him, Lord! to whom shall we go? Thou hast the Words of Eternal Life."

The motives which induced many of our Lord's first followers to withdraw themselves from his person, and wholly relinquish the connection they had formed with him and his disciples, I have explained in the preceding discourse. The erroneous conduct of mankind in general, their mistaken notions of happiness, the false and dangerous paths in which they pursue it, their delusive hopes and real disappointments; the palliative arts they make use of to reconcile their duty with their passions, and the various methods by which they deceive themselves as well as others; their hypocritical pretensions to religion, and the ways in which their deceptions are discovered, and their pharisaical professions unveiled; in a word, the genuine sources of that error and apostasy, into which the unworthy disciples mentioned in the text, as well as others who have since imitated their example, have sadly degenerated; all these particulars were suggested to my mind, from the consideration of these words of the Evangelist, "From that time many of his disciples went back, and walked no more with him."

The tender and pathetic expostulation which this ungenerous conduct produced from the blessed lips of the common Friend and Saviour of Man, breathes such a spirit of love, kindness, and compassion, towards the souls of those whom he came to redeem, as cannot but claim our most serious and grateful attention. The deep concern he must have felt for such an instance of apostasy, added to his apprehensions of the fatal influence it might have upon his beloved Apostles, awakened in him all those innocent and delicate sensibilities, which, even in his human nature, were the genuine offspring of that Eternal Love to which he was essentially united.

Friendship, true friendship, is the Heaven-born Offspring of Divine Charity. Heaven is her native country. In that pure and gentle element she lives and moves without constraint, free, chearful, delighting and delighted. If ever she deigns to associate with the sons of men, it is among the truly virtuous alone she can be found. She visits none but those, whose "conversation is in heaven," who have within them a birth congenial with her own, whose hearts and affections are governed by the Spirit of Love, and can only be wooed and won by correspondent tempers and characters. Her sacred name, indeed, is often prostituted to venal, base, and corrupt purposes. Her fair and beauteous garb is often worn by the votaries of avarice, pleasure, and ambition. Her sweet aspect, her mild and winning graces, her obliging and disinterested disposition, yea, even her peculiar warmth of affection, and glowing sensibility of heart, are all profanely counterfeited by the selfish and sensual, the vain and the aspiring.

Take it for granted, however, that man, whether gay, dissolute, covetous, or ambitious, is incapable of real friendship: all his designs and prospects center in himself, and every seeming act of kindness, every splendid appearance of courtesy and generosity, is calculated to promote some selfish purpose, to procure some temporal emolument.

Far different is the friendship of those who are "born of God;" who, from a vital union with the Source of Love, derive such pure and unadulterated streams of Charity into their breasts, as manifest themselves in a life of general beneficence towards all men, and a warm, affectionate, spiritual attachment towards "those especially, who are of the houshold of faith." Such, but in the purest highest degree, were those heavenly feelings of true friendship, with which the heart of Jesus glowed, when he uttered this sweet and endearing expostulation, "Will ye also go away?"

The words are few, but the sentiments are manifold, gracious, and animating; and they cannot but appear so to those, who attend, with nice discernment, to the common feelings of human nature. It is to these common feelings that our Lord makes his appeal, in all his heavenly discourses.

Though, from the general corruption, it is a case that has but seldom occurred in the page of history, yet let us suppose a good and virtuous man, associated with a set of good and virtuous companions, bound to him by the strong and endearing ties of private friendship, in the defence of some good and virtuous cause. Novelty, the love of fame, a desire of appearing to the world in some conspicuous point of view, the prospect of some great temporal advantages, and a variety of other motives of a selfish nature, might suddenly prompt a considerable number of persons to join these champions of virtue, and follow them in the glorious enterprize. Enemies appear, dangers threaten; yea, death, perhaps, in all its horrors, presents itself to their view. Personal security is to be preferred before the general interest of virtue; and where virtue cannot be supported without personal losses, her cause must be abandoned. Upon these principles, the weak and timid multitude forsake their gallant leader. Attached to him by no bonds, but those of interest or ambition, when these fail, they think themselves at liberty to abandon his person and his cause. The noble chieftain, not so much affected with the prospect of danger to himself and his cause, as with a real concern for the baseness of his followers, and an apprehension, that their flight might perhaps intimidate those, whom he knew to be attached, from principle, to virtue and himself; the noble chieftain, I say, might with great propriety, and without the least tincture of fear or despondency, but rather as a trial of their fidelity, and a most powerful incentive to new and more vigorous efforts, address himself in such words to the chosen few, as those, which the great Captain of our Salvation delivered upon this occasion: "Will ye, also go away?" In this address, there is not implied the least unkind suspicion of their integrity. It is no more than an affectionate appeal to the warm and tender sensations of true and genuine friendship.

O, my beloved Apostles! ye see the weakness, timidity, and worldly-mindedness, of those pretended friends, who have hitherto associated with us. So violent hath been their attachment to earthly pursuits, that they would not suffer truths of the highest importance to interfere with them for a moment. My last spiritual address was too deep and powerful a stroke at their corruptions. Could they have continued in fellowship with us upon their own terms, and made their connexion subservient to their own views of temporal interest, they would not have so suddenly forsaken us. But shall their conduct have the least influence upon yours? Will ye be intimidated by their flight? Will ye suffer your fidelity and perseverance to be shaken by their evil example? Will ye unkindly abandon a Master, into whose service ye entered upon the most disinterested principles, and who knows and feels you to be attached to him by the heavenly ties of religion and love? After having seen so many indubitable testimonies of that almighty power wherewith he is invested, will ye doubt his ability to protect and deliver you? After so many kind and instructive conversations, in the course of which he hath gradually, and as he found you "could bear them," opened to you the great truths of his spiritual kingdom; will ye be such enemies to yourselves, and your real happiness, as to forsake your best of friends, your kindest and most powerful protector? "Will ye also go away?"

These sentiments, and more than these, are expressed in this pathetic expostulation: and for our comfort, my brethren, may we ever recollect, that, though ascended into the highest heavens, and seated at the right hand of his Father, he continues the same loving conduct towards all his faithful friends and followers, that he observed towards his disciples whilst he was upon earth. The same gentle and affectionate modes of speech, the same tender, but awakening expostulations, to which his Apostles were accustomed, he still applies to the heart of every believer.

If we look back to past experience, we shall be convinced, that this very expostulation of our compassionate Master, hath frequently sounded in our ears. When the infectious influence of evil example, the sudden attack of some powerful temptation, some severe stroke of adversity, or some smiling prospect of temporal felicity; when these, or any of these, have secretly solicited our frail nature, to relinquish our religious pursuits, to surrender ourselves to the dominion of sin, and renounce the favour and protection of our Master; hath he not frequently, and with ineffable tenderness, whispered this gentle reprehension to our hearts, "Will ye also go away?" Happy, indeed, if, with Peter's affectionate warmth, and honest faithful adherence to our Lord, amidst the severest trials, we have been enabled to reply, from a full conviction of our own weakness, and of his all-sufficiency, "Lord! to whom shall we go? Thou hast the words of Eternal Life."

Peter generally spoke in the name of all his brethren. His answer here, therefore, is to be considered as a solemn declaration on the part of the Apostles, of their firm trust and confidence in their Master, founded on the full evidence they had received of his Divinity. As if he had said:

Think not, dearest Master, that thy faithful disciples are actuated by such unworthy motives as have prompted some of their weak and carnal brethren to forsake thee. No—we are intimately convinced of the folly of depending upon any creaturely strength, or seeking for happiness in any sublunary prospect. Thou hast opened upon our wondering souls such scenes of heavenly bliss, thou hast manifested to our outward senses such astonishing displays of thy absolute power over all temporal nature, thou hast revived our hearts with such sweet draughts of those rivers of pleasure that surround thy Father's throne, thou hast enlightened our understandings with such piercing beams of truth, thou hast placed such endearing objects before our will and affections, and hast so enamoured our souls with the beauty and excellency of thy Gospel; that we are perfectly satisfied to remain with thee for ever, implicitly to follow thy blessed footsteps, to accompany thee through all the difficulties and dangers of life, and even to meet death undaunted at thy side. Indeed, "to whom shall we go?" Every creature around us, bears the stamp of its own imperfection. Whatever they possess of beauty or of bliss, it is all from thee, thou Lord of life, and source of all perfection! They are in themselves, as poor and indigent as we are. If we make the experiment, and go to them in quest of happiness, our fond hopes are suddenly overthrown, and vexation succeeds to disappointment. The life we are now in, is fallen, temporal, and transient. The words of this life are as vain as the life itself: for it can only speak what it knows and feels, and the sum and substance of this is want and woe. But as thou hast in thyself the very source of eternal life, by virtue of thy eternal union with the Father; as the powers, sensibilities, virtues, and perfections of this life, are completely opened in thee; as the "fulness of the Godhead dwells bodily" in thee, so thy words must be the "words of eternal life:" for thou "speakest that thou dost know, and testifiest that thou hast seen." Thy outward words are, indeed, but the outward signs of this life eternal; the real participation of it can be nothing less than an inward and vital union of our wills with thine, effectually co-operating, and gradually "transforming us into thine own image, from glory to glory."

Such was the import of the Apostle's reply; and such must be the real heart-felt language of every sinner, that expects peace and pardon at the hands of the Almighty. Pardon of sin, is not, as some vainly imagine, like the cancelling of a bond, the remitting of a debt, or the forgiveness of an injury betwixt man and man. No—It is a "dying unto sin, and a rising again unto righteousness." It is life eternal opening itself in the fallen soul, and extinguishing the life of sin, or at least keeping it in due subjection, till the dissolution of the body puts an end to its connection with this fallen world; it is, according to the Apostle's language, "the law of the spirit of life making us free from the law of sin and death."

That eternal life, which we have, and can have only from Jesus Christ, the second Adam, can alone pardon, remit, atone, cover, extinguish, (for all these are words of the same spiritual import) that earthly life, which we have received from the first Adam. The very first motion of this eternal life within us, is a conviction of the vanity, sin, and folly of our earthly life. "They that are whole need not a physician, but they that are sick." A sensibility of want and weakness must necessarily precede a desire of relief: and the soul must be "weary and heavy laden," oppressed beneath the burden of her fallen nature, and convinced of its inability to yield her a moment's real peace, before she will think of making this solemn inquiry, "what shall I do to be saved? to whom shall I go?" Yea, even after she is come thus far, many a weary step must be taken, many doubts and difficulties must be encountered, before she will be able, from her own experience, to adopt this declaration of the Apostle, "Thou hast the words of eternal life."

Those doubts and difficulties, with which men are frequently embarrassed in their spiritual researches, do in a great measure proceed from that general deviation from the primitive simplicity of Gospel Truth and Gospel Language, which so sadly prevails among the various denominations of Christians; in consequence of which, a multitude of useless and unscriptural distinctions have been introduced into catechisms, systems of divinity, and even books of practical devotion, which serve only to perplex and confound the mind of anxious and well-disposed inquirers.

"To whom shall I go?" cries the poor penitent sinner, whom Christ, by the Power of his Grace, hath brought to a sensibility of his fallen life. Why, go to the priest, says one; confess, and get absolution, and you will come away as innocent as a new-born babe. Go, and study the Augsburg confession, says another, and you will soon have every doubt and difficulty removed. Go, says a third, and read Calvin's system with great attention, and you will soon find your soul at rest. Some advise him to join himself to one sect of Christians, and some to another; each maintaining, in his turn, that the life and power of religion is only to be found among those of his own particular society.

The poor misguided seeker eagerly catches at every thing that looks like spiritual advice; runs from one book to another, from one church and conventicle to another, "seeking rest, but finding none," or at most, a temporary peace, a partial truce from extreme distress; whereas after all, a few plain words of Scripture, properly applied and attended to, will go further towards setting him right in his researches, than all the popes and priests, and Luthers, and Calvins, and sects and denominations, in the world.

What then hath a minister of Christ, or indeed any private Christian, to say or do, when a true penitent under such circumstances applies to him for advice, and asks him with the utmost anxiety, "To whom shall I go?" What can he do, what can he say, that will have a more immediate tendency to fix his attention, and compose his distracted mind, than to answer him in the words of the text? "To whom shouldst thou go, but to Jesus Christ? it is he alone who hath the words of Eternal Life."

I know no other end of preaching but this; and I am sure, that we are warranted by Scripture to declare to every such humbled, penitent, and afflicted sinner, that if he thus seeks Christ, he shall not seek in vain. By faithfully directing his will and affections towards his Redeemer, thus inwardly unfolding his graces and virtues in his heart, he will become more and more acquainted, and more and more comforted, with that "Life Eternal, which is the gift of God in Christ Jesus."

2 Samuel, Chap. xxiv, Verse 24.

"And the King said unto Araunah, Nay, but I will surely buy it of thee at a price; neither will I offer burnt-offerings unto the Lord my God, of that which doth cost me nothing."

The preceding part of this chapter presents us with an awful and instructive example of the fatal consequences which result from an unbelief or distrust of the providential power and goodness of God. Contrary to the express command of the Almighty, contrary to the spirit of that dispensation, which inculcated an absolute and implicit reliance upon Heaven in all dangers and difficulties, yea, contrary to an happy experience of the most signal interpositions of Omnipotence; David had rashly issued a commission to the general and officers of his host, to go through all the tribes of Israel, and take a particular and exact account of the numbers of his people. Such a flagrant instance of unfaithfulness to his God, after so many merciful deliverances received, drew upon him a most severe chastisement. To humble the haughtiness of his spirit, and convince him of the folly of depending upon the arm of flesh, instead of taking the most High God for his shield and defence, a messenger of vengeance was immediately sent forth. From Dan even to Beersheba, he marked his progress with carnage and desolation: seventy thousand men, within the space of a few hours, fell a sacrifice to the devouring pestilence. He soon reached the beloved city, and was preparing to pour his phial of wrath upon the mount of God. The eyes of the unhappy monarch were now opened: he saw the destroying angel, humbled himself in the dust, acknowledged his guilt, and deprecated the further progress of the contagion. "Lo, I have sinned, and I have done wickedly: but these sheep, what have they done?" Omnipotence arrested the Angel in his progress: "It is enough—stay now thine hand." And David was directed by the prophet Gad, to rear an altar unto the Lord, on the very spot where the pestilence had ceased. This spot was the threshing-floor of Araunah the Jebusite.

Deeply sensible of the greatness of his deliverance, the king immediately proceeded to execute the divine command. Araunah discovered him at a distance; and with all the submission of a conquered and tributary prince, hastened to meet him, and "bowed himself before the king on his face to the ground." "And Araunah said, Wherefore is my lord the king come unto his servant?" And David said, "To buy the threshing-floor of thee, to build an altar unto the Lord, that the plague may be stayed from the people." Araunah, as a king, with a princely generosity of spirit, immediately offered him, not only the threshing-floor, but also his oxen for the sacrifice, and his threshing instruments for wood. "And the king said unto Araunah, Nay, but I will surely buy it of thee at a price; neither will I offer burnt-offerings unto the Lord my God, of that which doth cost me nothing." The plain and obvious meaning of which is undoubtedly this:

Hath God favoured me with such an astonishing deliverance? Hath he manifested his goodness and loving-kindness in withdrawing his chastising hand, pardoning my guilt, and sparing me and my people from utter destruction? Surely, then, I will not grudge, the trifling expence of erecting, upon this spot, a monument of his love. Surely I will not accept of the labours of another, or testify my gratitude by burnt-offerings and sacrifices at another's expence. The least I can do is, to make such an acknowledgment, and in such a manner, as will best evidence my sense of the obligation, and the honour that is due to my Almighty Deliverer.

Those who look beyond the letter and the outward history, will readily discern the state of David's mind. They will readily discern this outward action of his, though adapted to the outward dispensation under which he lived, to be highly expressive of that great and fundamental principle, which every dispensation of Truth, from the fall of man down to this very day, hath strongly inculcated, viz. that true religion is an inward life, that cannot rest in external appearances, but manifests itself in an absolute unlimited surrender of the whole man to his Creator. This can never be accomplished without considerable cost and expence on the part of the creature, inasmuch as his will and affections must first be drawn off from all that variety of imaginations, desires and enjoyments, to which his fallen nature strongly allures, and deeply enslaves him.

Hence it is, that our Blessed Lord makes the very first duty of discipleship to consist in "denying ourselves, taking up our cross, and following him:" that is to say, in bearing, with meekness, the necessary evils of our fallen life, resisting and overcoming its sinful suggestions, and humbly waiting for and co-operating with his Spirit revealed in our hearts.

This is the spiritual warfare, the struggle betwixt the "law in the members," and the "law of the mind;" the fighting "not only against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers," in which we are all summoned to engage. The whole burnt-offering and sacrifice, the whole price which this must cost us, is nothing less than the turning our wills, with the whole tide of our affections, from the evil to the good principle within us. And that God through Christ hath given us ability to do this, will appear from the following considerations:

The will of man, as coming forth from the Eternal Will of God, must be eternally and essentially free. The will of the fallen angels in hell, was as free as that of the highest archangel now in heaven:

The whole difference betwixt them consists in this, that the will of those who fell, is freely turned to evil; the will of those who stood, is freely turned to God and Goodness.

Man stands in an intermediate state, betwixt light and darkness, betwixt life and death, betwixt heaven and hell. The whole tenor of Scripture, from beginning to end, represents him in this critical situation; represents his Heavenly Father, as calling to him and inviting him to "eschew evil, and to do good;" to "love light rather than darkness;" to "come to him, that he may have life." All which certainly implies, that God, by his Grace, hath given him a power of choosing, and has made his salvation or destruction to proceed from himself, and not from any predetermining divine decree.

Jesus Christ is always spoken of, as a freely given Saviour; but salvation, as "a treasure to be purchased, as a race to be run, as a battle to be fought, as a work to be accomplished, even with fear and trembling." The power or capacity of being saved, the whole merit of salvation, comes from Christ; the using of this power, the availing ourselves of this merit, from ourselves. "Why WILL YE die, O house of Israel? Turn yourselves, and live ye. Ye WILL NOT come to me, that ye might have life. How often would I have gathered you, as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye WOULD NOT!"

Upon this principle of forsaking sin, and turning our will to Goodness, are founded all those Gospel precepts, which speak of "crucifying the flesh with its affections and lusts, destroying the old man, dying to sin, suffering with Christ, cutting off a right hand, plucking out a right eye, passing through much tribulation;" all which plainly shews, that True Religion is a perpetual sacrifice; and that this sacrifice cannot be "offered to the Lord our God, of that which doth cost us nothing;" that the price will be far more, than "fifty shekels of silver," the purchase of Araunah's threshing-floor and implements; yea, that it will be no less than the "whole body of sin," which we carry about us, with all its affections and lusts; which we must, with meekness and humility, surrender to our Blessed Redeemer, to be burnt up and consumed upon the fire of his altar.

Having thus endeavoured to establish this fundamental principle, that "true religion is a costly and a perpetual sacrifice;" let us now, to prevent any dangerous deception, turn our eyes to those false appearances of it, which we frequently meet with in the world, which are very easily assumed, and which cost nothing.

The man of moral honesty first steps forth, and puts in his claim to the character of religious. He looks upon any Revelation from Heaven to be quite unnecessary; and, with all the forwardness and presumption of his own blind reason, pronounces those books, which Christians believe to be of Divine Authority, to be idle and chimerical. His religion, he will tell you, is, "to do as he would be done by." Poor man! it were well, if he even practised this golden rule; it might lead him to something further: for, by endeavouring to fulfil this, he might be brought to a view and feeling of his own natural inability; of the evil tempers and passions of his soul, which, in innumerable instances, hurry him on to do to others, what he would, by no means, have them to do to him. His religion, therefore, is properly visionary. Every thing to him is just and right, that comes within those bounds of honesty, which have been fixed by the laws of the land. A right life is not, with him, a right principle in the heart; but only a set of outward actions, that in the eyes of the world give him the character of an honest man.

The religion of such a person "costs him nothing." He has nothing to sacrifice, but much to gain by the practice of it; at least, much of worldly happiness; for he can have no idea of any other. Being wholly destitute of all sensibility with respect to the evil of his fallen life, he is not in the least desirous of purchasing a better, at the price it will cost. Before he can form any conception of the necessity of religion, as a real inward change and renewal of heart, he must first be made sensible of his present error and misery: "for they that are whole need not a physician, but they that are sick."

Next comes the nominal Christian, who hath been baptized, and professes to believe the great truths of the Gospel, and joins with some publick assembly of Christians in outward worship. Surely his claim to the religious character, hath a better foundation than the preceding one: he purchases it at an higher price; it costs him more to support it. He neglects no outward duty, either moral or instituted; you never miss him at church, or at the sacrament: he hath been strictly educated from his infancy; he is sober, virtuous, kind, and charitable. In a word, he appears to be, what it were to be wished every man in the world really was. Thus far he is undoubtedly right: a strict observance of all the outward duties of religion, a minute attention to things in themselves indifferent, and a prudent abstaining from every appearance of evil, are doubtless incumbent, even upon those who have made the greatest progress in the Divine Life.