IRON STORE-FRONTS, No. V.

By Wm. J. Fryer, Jr., with

Messrs. J. J. Jackson & Bros., New York.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Architectural Review and American Builders' Journal, Aug. 1869, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Architectural Review and American Builders' Journal, Aug. 1869 Author: Various Editor: Samuel Sloan Release Date: December 22, 2019 [EBook #60997] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ARCHTECTURAL REVIEW, AUGUST 1869 *** Produced by Paul Marshall and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber, and is placed in the public domain.

Vol. II.—Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by Samuel Sloan, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States, in and for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

In a tolerantly critical notice of the Review recently published in the Builder, we find an effort to substantiate a charge formerly made by it, and replied to by us, on the subject of “trickery” in the construction of the exteriors of American buildings. The Builder reiterates the charge and points to Grace Church, New York, in proof of the truth of it. That marble edifice, he avers, has a wooden spire, crocketted, etc., painted in imitation of the material of which the body of the church is constructed. Alas, we must acknowledge the wood. And we will make a clean breast of it, and still farther acknowledge that at the time that Grace Church was built, our land of wooden nutmegs, and other notions, had not an architectural idea beyond the wooden spire, and that our city and country churches, that aspired at all, were forced to do so in the national material of the day. That said sundry spires of wood were of necessity, painted, is most true; and furthermore, white-lead being a great favorite with the people generally, [when our manners, customs, and tastes were more immaculate than in these degenerate days of many colors,] that pigment was the ruling fashion. That the color of the marble, of which Grace Church’s body is constructed, should be similar to that with which said ecclesiastical edifice’s spire was coated, is unfortunate; but, that the resemblance goes to prove any attempt at a cheat, we most strenuously deny. Grace Church is of a by-gone taste,—an architectural era which we now look back to in order to see, by contrast, how far we have advanced in architectural construction. Trinity Church, New York, was the first great effort at a stone spire which our Architects ventured to rear. And although hundreds have followed its lead, none in this soaring republic have gone so near to heaven as that yet. But the thing once effected is sure to be improved upon.

We are not at all abashed then, to own to the wooden spire painted to imitate stone, which crowns the steeple of old Grace Church, New York. And the less annoyance should it give our most sensitive feelings, when [Pg 66] we reflect that the dome of the great St. Paul’s, London, is no less a delusion and a cheat, it being of wood, coated with lead and painted on the outside, having a false dome on the inside, considerably smaller than the external diameter would naturally lead the confiding observer to expect. The body of St. Paul’s is of stone. Why, according to the requirements of the Builder, is not the dome, like that of the Pantheon at Rome, likewise of stone?

Do we suppose, for an instant, that Sir Christopher Wren was guilty of a deliberate cheat in so constructing it? Certainly not. He used the material which he considered best suited to his purpose and his means. And so we should, in charity, suppose did the Architect of Grace Church, New York.

The Builder, like too many of our English cousins, who do us the honor of a visit, falls into error in supposing that wood is generally used for ornamentation of exteriors. In none of our larger cities is this the case. And when that critical and usually correct authority says, “Even the Fifth avenue itself is a sham as to much of its seeming stone-work,” it displays a melancholy absence of its uniform discernment, judgment, and sense.

The only other constructive material to be found on the fronts of the Fifth Avenue, New York, besides marble, brown stone, or pressed (Philadelphia) brick, is in the gutter, which is either of zinc or galvanized iron, and forms the upper portion of the cornice.

Porches and Hall-door frontisces, of every style, are of marble or stone, and never of wood. Pediments and all trimmings around windows are invariably of stone. In fact we are not a little surprised at the apparent want of information on this subject by so well posted an observer as the Builder is acknowledged to be. Some twenty years ago the taunt might lie most truthfully applied to our efforts at architectural construction, but to-day the “trick” of painted and sanded wood would be hissed down by our citizens who claim to live in residences the majority of which are greatly superior to residences of the same class in London, as far at least as material is concerned. No, no—criticism to be useful must be just; and to be just must be founded strictly on truth unbiassed by prejudice.

We do not desire in these remarks to throw the slightest doubt on the good intentions of the London Builder in its monitorial check, but our wish is to correct the erroneous information which it has received, and which has led to the mistake under which it evidently labors.

We as utterly despise any falsehood in construction as our honestly outspoken contemporary, and will at every opportunity disclose and denounce its adoption in this country in all cases where there is any pretension to architectural design. For a new country like this, it is at least creditable that, even in a small class of dwellings, the architect is, as a general thing, called on to design and frequently to superintend—every thing is not left to the builder as in London. Yet there is and always will be in this as in all other countries a large class of private buildings outside the pale of legitimate taste; creations ungoverned and ungovernable by rule. But such should never be taken as examples of the existing state of the constructive art of the day; they should rather prove the unfortunate exceptions to the fact of its position. Even these it will be our duty to watch over and try to set right; for we are ardent believers in the influential power of information, and look with assurance to the education of our people generally on this subject of judgment and taste in building as the infallible means of turning to good account the remarkable progress in that constructive art of the American nation, which the observant London Builder notices with the generous well-wishing of a kindly professional brother. [Pg 67]

Of all the intellectual qualifications which man is gifted with, there is not one as sensitive as that which enables him to discern between what is intrinsically good, and what is bad or indifferent to his eye. Yet are there none of all man’s mental attributes so frequently and so grossly outraged as is this to which we now allude, called Taste.

Custom has much to say in the question of arbitrary rule which taste so imperatively claims. Persistence in any thing will, of necessity, make itself felt and recognized, no matter how odious at first may be the object put before the public eye, and ultimately that object becomes what is commonly called “fashionable.” This apparent unity of the public on one object is variable and will soon change to another, which in its turn will seem to reign by unanimous consent and so on ad infinitum.

In Architecture this fickle goddess, Fashion, seems to reign as imperatively and as coquettishly as in any or all the affairs of this world of humanity. That which was at first esteemed grotesque and ridiculous, becomes in time tolerable and at last admirable. But the apathy which sameness begets cannot long be borne by the novelty worshippers, and accordingly new forms and shapes remodel the idea of the day, until it ceases to bear a vestige of its first appearance and becomes quite another thing.

Of all the prominent features of architecture that which has been least changeable until late years is the “roof.” The outline of that covering has been limited to a very few ideas, some of which resolved themselves into arbitrary rules of government from which the hardiest adventurer was loath to attempt escape.

Deviating from the very general style of roof which on the section presents a triangle, sometimes of one pitch, sometimes of another, but almost universally of a fourth of the span, the truncated form was to be found, but so exceedingly sombre was this peculiar roof that it never obtained to any great extent, and indeed it presented on the exterior a very serious obstacle to its adoption by architects in the difficulty of blending it with any design in which spirit, life, or elegance, was a requisite.

There are occasionally to be found in Europe, and even in America, examples of these truncated roofs, but it is very questionable whether there are to be met with any admirers of their effect.

The principle on which they are constructed has, however, a very great advantage in the acquirement of head-room in the attics, giving an actual story or story and half to the height, without increasing the elevation of the walls. The architects of the middle ages took a hint from this evident advantage, and used the truncated roof on their largest constructions. Its form is that of a pyramid with the upper portion cut off (trunco, to cut off, being its derivation.)

Mansart, or as he is more commonly called Mansard, an erratic but ingenious French architect, in the seventeenth century invented the curb roof, so decided an improvement on the truncated that it became known by his name. This roof adorning the palatial edifices of France soon assumed so much decorative beauty in its curb moulding and base cornice, as well as in the dormers and eyelets with which it was so judiciously pierced, that it became a source of artistic fascination in those days in France; and as Germany was indebted to French architects for her most prominent designs, the Mansard roof found its way there, and into some other parts of Europe.

But, much as English architects admired, as a whole, any or all of [Pg 68] those superb erections of the Gallic Capital, it was a century and a half before it occurred to them to imitate them even in this most desirable roof.

Our architects having increased with the demand for finer houses and more showy public buildings, and having parted company with their Greek and Roman idols to which their predecessors had been so long and so faithfully wedded, and acknowledging the necessity for novelty, ardently embraced the newly arising fashion and the Mansard roof arose at every corner in all its glory. At first the compositions which were adorned with this crowning were pleasing to the general view, if not altogether amenable to the strict rules of critical taste. But in due time (and alas that time too surely and severely came) the pseudo French style with its perverted Mansard roof palled upon the public taste for the eccentricities its capricious foster-fathers in their innate stultishness compelled it to display.

Some put a Mansard roof upon an Italian building, some on a Norman, and many, oh, how many, on a Romanesque! Some put it on one story erections and made it higher than the walls that held it, in the same proportion that a high crowned hat would hold to a dwarf. Some stuck on towers at the corners of their edifices and terminated them with Mansard domes! Some had them inclined to one angle, some to another; some curved them inward, some outward, whilst others went the straight ticket.

The dormers too came in for a large share of the thickening fancies and assumed every style or no style at all. The chimney shafts were not neglected. Photos of the Thuilleries were freely bought up, and bits and scraps of D’Lorme were hooked in, to make up an original idea worthy of these smoky towers. “Every dog will have his day,” is a fine old sensible remark of some long-headed lover of the canine species, and applies alike to animals, men, and things. That it particularly applies to that much abused thing called the Mansard roof is certain, as the very name is now more appropriately the absurd roof.

Fashion begins to look coldly upon her recent favorite, which in truth “has been made to play such fantastic tricks before high Heaven, as make the angles weep;” and it is doomed.

A few years hence, and we will all look back in amused wonder at the creations of to-day, crowned with the tortured conception of Mansard.

The rapid hardening under water of the cement which from that property derives its name of “Hydraulic Cement,” has been, and indeed is still, a subject of discussion as to the true theory of such action. We find in the June number of the Chemical News a paragraph which must prove very interesting to manufacturers as well as to all who use and take an interest in that most useful of building materials to which the Architect and the Engineer are so deeply indebted.

“In order to test the truth of the different hypotheses made concerning this subject, A. Schulatschenko, seeing the impossibility of separating, from a mixture of silicates, each special combination thereof, repeated Fuch’s experiment, by separating the silica from 100 parts of pure soluble silicate of potassa, and, after mixing it with fifty parts of lime, and placing the mass under water, when it hardened rapidly. A similar mixture was submitted to a very high temperature, and in this case, also, a cement was made. As a third experiment, a similar mixture was heated till it was fused; after having been cooled and pulverized, the fused mass did not harden any more under water. Hence it follows that hardening does take place in cement made by the wet as well as dry process, and that the so-called over-burned cement is inactive, in consequence of its particles having suffered a physical change.”

In the preceding number we have spoken in general terms of this beautiful acquisition to our art materials, and indeed we feel that we cannot esteem this new American discovery too highly; for even in Europe such stone is extremely scarce at the present day, and it is fortunate that the location in which the quarries exist is open to the Old World to freely supply the wants of its artists, as well as our own. The beautiful Lake Champlain affords excellent commercial facilities, the Chambly Canal and Sorel River improvements opening a free navigation both with the great chain of lakes, and the Atlantic Ocean. The Champlain Canal connecting it with the Erie Canal and Hudson River, giving it uninterrupted communication with New York State and its Empire City, from the latter end of March to the middle of December.

The quarry is situated in a great lode projecting up in the bosom or bay of Lake Champlain, forming an island of several acres outcropping on each shore, and giving evidence that the deposit extends and really forms, at this point, the bed of the lake, its supply being thought to be inexhaustible.

The marble occurs in beds and strata varying in thickness from one to six feet, and will split across the bed or grain; blocks of any required size being readily obtained. Its closeness of texture and hardness render it susceptible of a very high polish, and it will resist in a remarkable degree all atmospheric changes. It is hard to deface with acids or scratches, and this one fact should attach to it much additional value. Its variegation in color, as shown by the specimens taken from its outcroppings, give promise of a much richer development as the bed of the quarry is approached; and must equal in beauty and durability the highly prized oriental marble of ancient and modern times.

The facilities, already alluded to, of its transportation to all the markets for such material in the country and to the seaboard, whence it can be shipped to any part of the world, must tend to bring it into general use here and elsewhere, that colored marbles are required for building and ornamental purposes.

We are much indebted to a gentleman of Philadelphia, whose taste and liberal enterprise have so opportunely brought to our knowledge this most remarkable deposit of one of Nature’s most beautiful hidden treasures, which must, at no distant day, add vastly and more cheaply to the art material of our country.

The palace in course of construction at Ismalia, for the reception of the Empress Eugenie during her stay in Egypt, will be 180 feet wide and 120 deep. The estimate cost is 700,000fr. According to the contract it is to be finished by the 1st of October, for every day’s delay the architect will be subject to a fine of 300fr per day, and if finished before he will receive a bonus of 300fr per day. The building will be square; in the centre there is to be a dome covered with Persian blinds. On the ground floor there will be the ball, reception, and refreshment rooms. An idea can be formed of the importance of this structure and of the work necessary to complete it within the required time, as it will contain no less than 17,400 cubic feet of masonry.

To Remove Writing Ink—To remove writing ink from paper, without scratching—apply with a camel’s hair brush pencil a solution of two drachms of muriate of tin in four drachms of water; after the writing has disappeared, pass the paper through the water and dry.

By W. J. Fryer, Jr., New York.

The elevation, shown in the accompanying page illustration, shows an iron front of five stories, having a pedimented centre frontispiece of three stories in alto relievo.

The style, though not in strict accordance with rule, is showy, without being objectionably so, and goes far to prove the capabilities of iron as a desirable material in commercial Architecture, where strength, display, and economy may be very well combined.

Such an elevation as this, now under consideration, could not be executed in cut stone, so as to produce the same appearance, without incurring a much greater expense, and in the event of a continuous block of such fronts, the balance of economy would be wonderfully in favor of the iron, for the moulds could be duplicated and triplicated with ease, whilst the same composition executed to a like extent in stone would not be a cent cheaper in proportion. Every capital and every truss, and every fillet, should be cut in stone independently of each other, no matter how many were called for.

It may be very well to say that stone is the proper material, according to the long-accepted notion of art judgment, and that iron has to be painted to give it even the semblance of that material, being, therefore, but a base imitation at best. All very true. But, nevertheless, iron, even as a painted substitute, possesses advantages over the original material of which it is a copy, rendering it a very acceptable medium in the constructive line, and one which will be sought after by a large class of the community who desire to have this cheap yet practical material, even though it be not that which it represents. As a representative it is in most respects the peer of stone though not it identically.

BY CARL PFEIFFER, ESQ., ARCHITECT, N. Y.

This design is of one of those homes of moderate luxury wherein the prosperous man of business may enjoy in reason the fruits of his energetic toil. There is nothing about it to indicate presumptuous display, but rather the contented elegance of a mind at ease, surrounded with unostentatious comfort.

[Pg 71] On the westerly slope of the Palisades, and two miles to the west of the Hudson, this residence was built by one of New York’s retired merchants.

It is sixteen miles from Jersey City, in a town of but a few years growth, named “Terrafly,” in Bergen county, and stands on a hill commanding some of the most charming pieces of pastoral scenery, occupying about thirty acres laid out in lawns, walks, gardens, etc., and tastefully ornamented with shrubbery, having a fountain on the lawn in front of the house (as shown.)

The approach is from the public road, by a drive through a grove of about ten acres of stately trees, passing by the side of a pretty pond formed by the contributions of several streams and making a considerable sheet of water. About the middle of this pond the sides approach so near to each other as to be spanned by an artistic little stone arched bridge which leads to the garden.

From the house one looks on a lovely panorama of inland scenery. The Palisades towards the east, the Ramapo mountains to the northwest; and looking in a southerly direction the numerous suburban villages and elegant villas near New York may be seen.

The house is constructed of best Philadelphia pressed brick with water-table, quoins, and general trimmings of native brown stone neatly cut. It stands high on a basement of native quarry building stone and has for its foundation a permanent bed of concrete which likewise forms the basement floors, as well as a durable bedding for the blue flagging of Kitchen and Laundry hearths.

[Pg 72] The arrangement of plan is admirably calculated to conduce to the comfort of the family. It is as follows:

Fig. 1 shows the plan of the basement. A, steps and passage leading from Yard. B, Servant’s Dining Room. C, C, C, Coal Cellar and Passages. D, Kitchen. E, Pantry. F. Laundry. G, G, Cellars. H, Water Closet. I, Wash tubs in Laundry. J, Dumb waiter. K, Wash-tray. L, Sink. M, Back stairs.

Fig. 2 shows the plan of the principal story. A, Dining Room. B, Drawing Room. C, and D, Parlors connected by sliding doors with the Drawing Room through the hall. E, Principal staircase. F, Back Hall. G, Butler’s Pantry with dumb waiter, plate closet, wash-trays, etc. H, Back stairs. J, Conservatory. K, Steps leading down to Yard. L, L, L, Verandahs. M, M, Piscinæ.

Fig. 3 shows the arrangement of the Chamber floor, or second story. A, the Hall. B, C, D, and E, Chambers. F. Boudoir. G, Closet. H, Passage to Boudoir. I, Half landing connected with rear addition. J, Back passage. K, Bath Room. L, M, N, Servant’s Bed Rooms. O, O, O, Clothes Closets. P, Water Closet, o, o, o, o, o, o, Wardrobes in the several Chambers. These occupy the angle enclosed by the slope of the Mansard, thus leaving the walls of the chambers plumb.

The roof is flat, and is embellished at the curb with a rich traceried iron balustrade, making a safe and desirable promenade platform. All the accessories that go to make a comfortable home are provided, and the whole forms a model retreat from busy life to Nature and her charms.

We here give a perspective view of a capacious suburban residence, showing the marked effects of light and shade produced by means of Gothic gables on a building of a square plan. A hipped roof on such a plain form would make a most uninteresting mass of heaviness. The judicious addition of bay windows is always desirable in such compositions; and the hooded gables give a pleasing quaintness to the whole. We present, on next page the principal floor plan, which is somewhat unusual in arrangement, but comfortable, as such form of house is always sure to be.

A, The Porch, pierced on each side with open lights. B, the Hall, in the form of an L, and receiving light from the roof. C, the Drawing Room, with its capacious bay window. D, a Parlor. E, Library and Study. F, Side Hall, with door, under stairs, communicating with passage leading to study; (or, there may be a door opening directly into the study from the side hall.) G, Private Stairs. H, Principal Stairs, under which is a door communicating with the passage to study. I, the Kitchen. J, Pantry. K, the Dining Room, with glass door leading out into the Conservatory L.

[Pg 73] Few arrangements of plan can be more complete. Chimnies all in the inner walls retain the whole of the heating within the house in winter. And so thorough is the natural ventilation, by doors and windows, that coolness is secured in the summer time.

Executed in stone, either hammered or rough rubble, with cut-stone trimmings, this house would present a pleasing appearance. In pressed brick, with stone trimmings, though not so consonant to surrounds of shrubbery as in stone, it would yet be a neat object and tend much to the embellishment of the outskirts of a city or village.

There is a great want of suitable designs calculated to meet the tastes and necessities of those communities whose funds are too limited to admit of anything approaching to architectural display. Our object, therefore, in presenting the two which illustrate our remarks, is to show the way to others to do likewise.

Churches of large dimension and assuming appearance call forth professional skill, because the expenditure will be commensurate with the expansive ideas of the wealthy for whose benefit such edifices are constructed. But a plainer class of erections, as much wanted, should draw out the efforts of our brethren, if only for the good they may do.

There are few architects who are not subject to the often occurring claims on their donative services in behalf of poor congregations, and, [Pg 74] we say it with pride, that we have yet to hear of the first instance of those claims not being promptly attended to by even the busiest of our brethren. Although it too frequently happens that their liberality is severely and most thoughtlessly taxed; for there generally is in every community some spirit too restless to cease troubling even those whose time is very limited. In a serial like the Architectural Review there is an opportunity presented to give, from time to time, sketches and instructions, by which the wants of the bodies we allude to may be met. The pastor in the backwoods, and the minister on the prairie, as well as the servant of God who teaches the poor in our crowded cities, and skill are freely given, not to them personally, but to the sacred cause they are supposed to have an interest in. But let that pass.

The illustrated works on Ecclesiastical Architecture, which come from the press, usually treat of a class of edifices altogether beyond the reach of the congregations whose means are limited—will each and all be benefitted by the information given, and a truly good work will thus be done. The two small churches here presented are now in course of construction in this city.

The one on the upper part of the page is a Chapel of Ease to the Calvary Presbyterian Church, now building on Locust street, west of Fifteenth street.

[Pg 75] Its dimensions are fifty-seven feet front by ninety feet deep, outside measurement. It will be two stories high, with gallery.

The first story will be sixteen feet from floor to floor. This is to be the Lecture Room. The second story will be twenty-five feet at the walls, and thirty-nine feet to the apex of the ceiling in the centre. The Gallery will be six feet wide along the sides, circular on front, and the ends curved at the rear. Its floor will be level.

Besides the Lecture Room, the first floor will contain two class rooms and the ladies’ parlor. Immediately over the Lecture Room, and of the same size, will be the Sunday-school Rooms. And over the ladies’ parlor there will be the Infant School.

On the gallery are three class rooms on the front, two of which are over the Infant School Room, and one over the eastern stairway. There are two class rooms in the rear. The walls will be of rubble masonry. As high as the level of the first floor, and projecting two inches, with a wash, the exterior will be hammer-dressed. Above that, the superstructure will be all laid broken range, pointed off, except the rear wall, which will be rubble with rock face. The whole will be faced with Trenton Brown Stone.

All the dressings of the doors, windows, buttress, caps, cornices, [Pg 76] pinnacle caps, etc., will be distinguished by a finer class of work.

The roof and its dormers will be covered with best Blue Mountain slate, of medium size, varied with green and red color.

The interior as well as exterior finish will be Gothic in style, inexpensive yet expressive.

Fig. 1. The plan of the Lecture Room is here shown: A, A, the entrances, with stairs in each, leading to School Rooms and continuing to Gallery. B, Ladies’ Parlor. C, the Lecture Room. D, Platform and desk. E, E, Class-Rooms. F, F, Water-Closets.

Fig. 2. This is the arrangement of the Second story, which contains: G, the Infant School Room. H, the School Room. J, J, Class Rooms. K, K, Water Closets.

Fig. 3. L, L, L, the Gallery. M, M, M, Class Rooms in front. M, M, Class Rooms in rear. It will be seen that, by means of sliding glass partitions, each floor can be considerably enlarged in accommodation. There are nine class-rooms, and school room for over six hundred children. The galleries will hold two hundred and fifty.

The illustration below that of Calvary, is the design of the Trinity Reformed Church, now being erected on the east side of Seventh street, south of Oxford street, in this city.

It is also Gothic in style, and although smaller than that just described, will, nevertheless, be a very convenient and tasteful church, and well suited to the wants of its growing congregation.

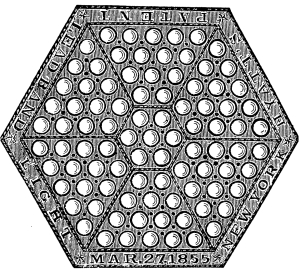

Few patents have conferred a greater blessing on society than that of which the accompanying cut is an illustration. The misery which was closely akin to area gratings, as used in “our grandfather’s day,” may yet be remembered by some not very old readers. Then light had to be admitted from the sidewalk without trespassing on the right of way by encroachment, and the manner in which that object was attained was by the use, invariably, of open iron gratings, which, whilst they admitted the light in bar sinister, as our heraldric authorities would say, did not offer any opposition to the falling dirt of the street which resolved itself alternately into dust or mud, according to the relative condition of the weather. The very palpable consequence of such a state of things was, that all areas under sidewalks were an accumulative nuisance which had to be borne if day-light was desirable in underground places.

Let us pause for a moment to mentally look back on those days of dirt-clad cellar windows, if it were only to enhance the value to our mind of the present state of things.

Hyatt’s Patent Vault, and Side-walk lights, are so well known and so universally appreciated North, South, East, and West, now-a-days, that it is doubtful whether we are enlightening a single reader of the Review in thus alluding to them. But, unfortunately there are people so listlessly unobservant in this world of ours, as to walk over them, aye, and walk under them, without perceiving the benefit enjoyed from them. Such people look on all improvements without wonder or admiration, and calmly set them down as matters of course—things that were to be, improvements—the growth of necessity. The inventive mind that gave them birth is neither thanked nor thought of. But all men are not so stolid. Many will take an interest in the benefaction and the benefactor, and to such the present notice will recall a duty—the grateful acknowledgment of a benefit bestowed.

The sidewalk lights are powerfully strong as well as perfectly weather-proof and they can be turned out in any required form in single plates to a maximum size of six and a half feet long by two and a half feet wide, or in continuous platforms. They are likewise made to answer an excellent purpose as steps and risers, or even as entire flights of stairs of any desired length. They are three quarter inch thick, hexagonal shaped glass, well secured and presenting a really handsome appearance.

In our preceding number we made some observations on a more fitting system of awnings than that now in use. [Pg 78]

We think there can be very little doubt but this very invention could be well made available for such a purpose, and we sincerely hope that the hint will not be lost sight of.

Brown Brothers of Chicago have for the last ten years been active in the manufacture and sale of the patent sidewalk lights, and there is scarcely a city of any pretensions in the Great West that has not awaked up to the use and value of this most beneficial invention, [Pg 79] and the pleasing consequence is that the Messrs. B. are now doing an immense business in the manufacture of them, at 226 and 228 Monroe street, Chicago, where the orders of our friends the Architects and Builders who propagate improvements in the growing cities of the irrepressible West, will be attended to, with that promptitude which has hitherto made the name of the firm of Brown Brothers so well known, and their excellent manufacture so fully appreciated.

The manufacture of this important and useful pigment has been very successfully prosecuted within the past year, by a new process, the invention of Dr. H. Hannen of this city, and is destined to supersede the old method, both as regards economy in preparation and purity of material. The old or Dutch process, requiring some six to eight months for its completion, fit for painter’s use; while by the Hannen patent it can be produced in from ten to fifteen days. The quality of the article is said to be fully equal, if not superior, to that of the lead made by the old method. The process of manufacture, as far as we can learn, is as follows:

The best Spanish pig lead is melted in a large iron kettle, holding from fifteen to eighteen hundred weight, and then drawn off by a suitable valve, and allowed to run over a cast-iron wheel or drum, about six inches on the face and three feet in diameter, running at a high speed, and kept cool by a stream of cold water constantly playing on it. The lead, in passing over this wheel, is cast into ribbons about the thickness of paper, it is then taken and placed on lattice shelving in rooms some eight to ten feet square, made almost airtight by a double thickness of boards, and capable of holding some three tons of the metallic lead as it comes from the casting machine in ribbon form, the temperature of the room is then raised by injecting steam to about one hundred degrees, and then sprinkled several times a day with diluted acetic acid, converting it into sub-acetate or sugar of lead. While this operation is going on, carbonic acid gas is forced into the room by means of a blower or pump, which decomposes the acetate and forms a carbonate of lead; this operation of forming an acetate, and then a carbonate, requires from five to six days, until a complete corrosion of the lead is effected; the room is now allowed to cool and the lead to dry, after which it is taken out and sifted through fine wire sieves, which separates all undecomposed lead or other impurities. It is then ready for washing and drying. The finely powdered lead is mixed with water into a thick pasty form and ground in a mill of similar construction to an ordinary flour mill, from which it is allowed to run into large tubs filled with water, and thoroughly washed and allowed to settle. The last or finishing operation is to place it in large copper pans, heated by steam, when it is dried; from thence taken to the color grinder, where it is mixed in oil ready for the painter’s use.

There is a presumptuous feeling in the breasts of those who, par excellence, assume the style and title of “Artists,” both in the Old and the New World, which it would be well to look into were it not that valuable time might thus be wasted on an exceedingly contemptible subject. We allude to the arrogation of eminence by those autocrats of the easel, who, not content with the undue position conceded to them by the vain and the frivolous who stilt themselves on their recognition of “high art,” and affect to govern the very laws of taste itself, go farther in the fulness of their ambition, and seek to ignore Architecture as an art. This outrage on common sense is not confined to America, it has been continuously practised, if not boldly promulgated, for over a century in London, by an institution bearing the absurd title of The Royal Academy, originally intended to foster and advance the interests of Architecture, Painting, and Sculpture, yet in forty elections, or rather selections, of Associates, that is, of those ordained to emblazon their names with the R. A., but four were Architects!

And, notwithstanding the studious efforts made by our profession to elevate our position and draw at least our share of public attention, we find that this Royal Academy and the rest of the aristocratic Dundrearifications, positively prohibit the appearance of architectural designs upon the walls of their National Galleries by crowding every available foot of wall space with easel-work, (we beg pardon—“paintings,”) ephemeral, unnatural, mannerized exudations of the “modern school,” that barely patronizes Nature as a stupid fact, which to be got round must be obliterated in gaudy coloring. But, shall Architects make bold to criticize these “Artists?” No, Painting is a sublime gift, by the magic touch of which the coarse inelegant canvas is made to put forth emanations of the etherial mind, which it were a pity to limit to the paltry boundary of a gilded frame!

Where would the art of Painting find a shelter, were it not for Architecture?

Do the gentlemen of the brush and palette ever look around and above at the walls, the ceilings, or even at the tessellated floor of the rooms where their small framed efforts are on exhibition, and suffer their overweaning vanity to acknowledge that Architecture is really something?

How many painters can properly depict it? How many?

The ignorance which urges the pre-eminence of Painting at the expense of Architecture is more to be pitied than contemned. And the public patronage lavished on the one and withheld from the other, is superinduced by the ease with which any one can assume to be a critical admirer of an art whose governing rules are imaginary rather than real or substantial.

Some see beauty in the fidelity which a painting bears to Nature. Others consider that very fidelity as slavish imitation. And a very general notion obtains amongst painters of “assisting Nature.” Now, Architecture stands upon the solid base of Truth. Without imitating, it borrows applicable ideas from Nature to be used in carrying out its designs. Nor is it merely the imaginations, limnings, as in the case of Paintings; those designs have to be executed. Construction then comes in as the solid, tangible, work of art, which shall defy the elements and render Architecture the protectress of Painting, without whose solid enduring defence the more fragile art would speedily decay and become unknown. [Pg 81]

But, are not the professors and admirers of Architecture themselves to blame for the degraded position it holds to-day as an art, here and in Europe? Why is there not more practical enthusiasm, and altogether less contemptible jealousy, and ill-natured feeling, amongst all who claim to have an interest in this the grandest and most over-shadowing of the Arts?

If Painting must needs hold an exclusive position as regards the public exhibitions of what is most erroneously called the “Fine Arts,” why cannot Architecture and Sculpture assert their dignity, and give the public a chance to patronize them independently? The truth is that Architecture and Painting do not at all agree in sentiment; the one is a mere luxury, and no more; the other is a necessary art, adorned or unadorned. The one can be glanced at and instantly understood; the other demands the effort of the mind to study and to comprehend. In Painting, the eye is the arbiter; in Architecture, the eye and the mind must form the judgment. It is not what a merely pretty picture is displayed; it is—how would that design look in execution?

Most of people who go to a “Fine Art Exhibition” are superficial observers. They glance at pictures by the hundred. Such are not the persons from whose judgment Architecture can expect even a recognition. They have been bedazzled with the sheen of the gilded frames, and the well laid-on varnish which bedizens the bright pigments of the gaudy glare of Art, which they have just left, and are, of course, impatient of the more staid and methodical elevations or perspectives, now presented in a narrow crowded section to their view. They have not time nor inclination to pause and consider them. They cannot bear to lose the impressions made by the “sweet shaded alley,” the “dancing streamlet,” or the “green reflective lake,” with that charming sky that looks so much more like heaven than nature. No, it will not do to exhibit Architecture and Painting together, and it is time to acknowledge this so often proven fact. The two must be distinct. Let Architects put forth their powers, and show the community what their Art really is, and what it is capable of. People will go expressly to view an exhibition of Architectural designs, combined with Sculpture, and take much pleasure in the visit, because their mind is prepared for the occasion, and will not be distracted by a rival exhibition of quite another effect. To say that the public generally will find no pleasure in the consideration of Architecture is to assert that which is disproved by fact. When the Commissioners, appointed to choose a fitting design for the new Post Office at New York, threw open to a limited number of visitors the inspection of the collection of designs, the rooms were crowded each day of the exhibition, and innumerable applications were made for tickets of admission. Had all the public been allowed the privilege, no doubt it would have been universally accepted. Yet that was but a very uninteresting display compared to one in which the subjects would be manifold, and the scales various. Not to speak of the freedom of display in color, which on the occasion adverted to was necessarily confined to an extreme limit.

Why cannot our Architects have an independent exhibition? There is nothing to be gained, but on the contrary every thing to be lost by clinging to the skirts of the painters. An effort in this direction could not fail to meet with the warmest support from our monied citizens, who are constantly proving substantially their regard for the progressive welfare of Architecture, by expending vast sums in buildings. And we have no doubt, but that State Legislatures would promptly and liberally aid any such effort to educate the general public in an art so intimately connected with the history of civilization. [Pg 82]

The anniversary of this great nation’s independence never was more fittingly honored than on the Fourth of July last, when, in this city, and in the front of the glorious old Independence Hall, Philadelphia inaugurated her statue of him who was First in Peace, First in War and First in the Hearts of his Countrymen. There is not in the United States a single spot more sacred to the cause of Freedom than that on which stands Independence Hall, where our great fathers of the Revolution so nobly pledged to the cause of mankind their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, and where the truly noble Washington was heard and seen, when the hopes of an embryo nation rested on his integrity.

Although the thought well suggests itself that an honor such as that just now paid the great patriot’s memory should long ere this have been credited to Philadelphia, yet it is never too late to do our name justice before the world; and it is appropriate that the rising generation of a closing century should thus mark the establishment of a free government for which he fought and conquered.

Thanks to the school children whose contributions thus have given to Philadelphia, what their sires so long neglected, a testimonial worthy of our grateful recollection of the foremost of Americans.

On the 13th of December, 1867, a contract was made with our eminent citizen artist, Mr. J. A. Bailey, and on the 2d of July, 1869, the material for the granite base was delivered on the ground. The following day the statue was duly erected, where it now stands in front of the entrance of that venerated Hall.

In the centre of the foundation is placed a box containing the names of children and teachers, Directors and Board of Controllers, Mayor and City Councils, heads of departments, records of the Association, etc., and a copy of the Holy Bible. The base of the statue is of Virginia granite, from the Richmond quarries, and is in four pieces, weighing about twenty tons. The statue is of white marble, 8 feet 6 inches high. The left hand of Washington rests on the hilt of his sword, sheathed in peace; his right hand rests on the Bible, the Bible on the Constitution and American flag which drapes the supporting column on the right of the figure. The weight of the figure is about six tons. The whole height of base and statue is 18 feet 6 inches. On the north front the base will bear the name—Washington; on the south, this inscription:

ERECTED

BY THE

WASHINGTON MONUMENT ASSOCIATION

OF THE

FIRST SCHOOL DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA.

The total cost, including a railing, will be about $6,500.

The ceremony of the unveiling was a most impressive one, the children being in the act of singing “Hail, Columbia,” when, at a given, signal, the flag covering the noble statue was raised, and from its folds came forth innumerable small flags which flew among the people and were eagerly caught.

As the marble image of Washington came into view the cheers of the assembled thousands were only outvied by the cannon in the square, and the national hymn was for the time drowned in the enthusiasm of the event.

The President of the Washington Monument Association Mr. George F. Gordon, in an appropriate address to the Mayor and Select and Common Councils, presented the beautiful monument to the city. It was received by the Mayor, Hon. Daniel M. Fox, in a suitable [Pg 83] reply, and the benediction being pronounced, this most interesting event became part of the brightest of Philadelphia’s chronicles.

The munificence of our fellow-townsman, W. W. Corcoran, Esq., has been handsomely acknowledged by the National Academy of Design, at New York, which has transmitted to him congratulatory resolutions with reference to his recent foundation of a gallery of art in this city.—Washington Chronicle.

Our latest files are to April 21st, inclusive. Sydney was at that time in high spirits over the recent visit of the Prince Captain of H. M. S. Gallatea. The most noteworthy action of whom was the laying of the corner-stone of the testimonial to the hardy navigator and discoverer, Captain Cook. We extract the remarks of the leading journal of Sydney.

“The Captain Cook Memorial.—A monument to the memory of Captain Cook will be rather an expression of our admiration for his character and services than an enhancement of his fame. The last generation was filled with wonder at the narrative of his discoveries. The first quartos that record them display in most striking forms the scenes and objects he made known to the world. He visited many islands of the Southern seas, whose voluptuous and animated social life attracted as to a new-found Paradise. Subsequent experience scattered the illusions of fancy, but brought out more clearly the value of his labors. New South Wales presented to his view a land of savages, lowest in the scale of civilization, but it also offered a noble field for British colonization, perhaps less appreciated while America was still a dependency of England, but brought into notice a few years after that country ceased to belong to the Crown.

“Cook first landed at Botany Bay, on the 19th of April, and on the 23d of August, he took possession of the entire country in the name of the Sovereign of England. The precise spot where he anchored is marked in the charts by a nautical symbol, and can thus be identified. On reaching the shore he found a spring of water ample for the wants of the ship, and tradition has reported that he bent his knees in adoration of the Supreme Being.

“The character of Cook as a navigator occupies the first rank in nautical sciences. It is to his high honor, that modern times, though they have added to his discoveries, have been rarely able to dispute them. Nothing is superfluous—nothing is obscure. The modern investigator starts from the observations made by Cook as undoubted facts. Every year displays more strikingly, not only the results of his discoveries and their value, but the almost prophetic foresight which presided over them.

“The history of Captain Cook is an example of the lofty position which may be taken by the humblest ranks when attended with high intelligence and superior moral qualities. The first step of his naval career was as a cabin boy. He rose to the command of an expedition which was suggested by scientific men, and their warmest hopes were more than fulfilled. They had seen with regret the blanks in the map of the world, and the ignorance which prevailed in reference to the true character and capabilities of countries partially known. The men of science who accompanied him on his voyage acquired for a time a scarcely inferior fame. Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander are names familiar to the readers of Cook’s Voyages, but the magnificence of his achievements leaves in the shade every inferior merit. He stands forth as the founder of a new era in nautical discovery, and as the revealer of a new world.

“Could Captain Cook have seen the spot on which it is proposed to erect his monument, and from thence, with superhuman knowledge, anticipated the events of this day, he would have been overwhelmed with awe.

“Edmund Burke delineated, while the struggle with America was [Pg 84] still transpiring, the emotions of astonishment with which he supposes Lord Bathurst, then an aged statesman, might in the days of his youth have looked forward, under the guidance of some celestial instructor, to the events which had raised American colonization from insignificance to greatness. But what emotions would have stirred the heart of Cook, if, standing on this spot, he had foreseen the progress of colonization, the painful labors included in the first fifty years, and the immense prosperity of the last.

“Had such heavenly anointing enabled him to foresee all this, his grateful spirit would have been filled—with—what sacred joy! Still further extending his intellectual prospect, he might have foreseen the arrival of a vessel furnished with the results of science then unattained, advancing like some being, instinct with intelligence, from port to port, through billows over which he was tossed, and independent of winds for which he had to wait, arrived at a fixed hour at the haven of its destination. And still farther, he might have seen the great grandson of that monarch whose name he proclaimed as the lord of this territory—the son of a royal woman who has inherited all the virtues of her race, without its faults; and he might have seen that son, surrounded with a multitude of her subjects, standing over the first stone of an edifice to do honor to his memory.”—Sydney Morning Herald, March 27.

“The New Post Office, Sydney.—The keystone of the central arch of the new Post Office, George street, was laid by His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh, on the 1st instant, in the presence of a vast concourse of spectators. A large platform was erected behind the arch, and on a level with the stone, access to which was obtained by carpeted stairs, springing from the northern side of the building.

“The stone laid by the Prince forms the keystone, archivolts and two spandrils of the central archway of the George street front. Upon the face are to be carved the Royal arms, and upon the coffered soffits the arms of the Duke. The dimensions of the stone are:—Length 13 feet 6 inches, width 4 feet 6 inches, and height 6 feet 6 inches—the whole being equal to 394 cubic feet. The weight is twenty-six tons. This stone is doubtless the largest yet laid by his Royal Highness, and it is probably the largest block of sandstone he will ever lay, for it would be difficult, if not indeed impossible, to get sound blocks of sandstone of equal size from any quarry in England, or elsewhere. Few cities are so favorably situated for sandstone as Sydney, for in almost every direction blocks of this description of freestone may be obtained of almost unlimited dimensions, and without a flaw. The most casual observer of the new Post Office cannot fail to notice the massiveness of the stones used in the building, and the solidity of the structure is unequalled by any other erection in the city. The contractor has placed very powerful cranes in his quarries at Pyrmont, whence these immense blocks of stone are obtained, and great credit is due to Mr. C. Saunders for the workmanlike manner in which these blocks—far exceeding in size anything previously attempted in the colony—have been quarried. The difficulty of removing these heavy blocks of stone must be very considerable; and the stone laid by the Duke of Edinburgh was equal to the force of twenty-one horses, calculating a horse to draw about twenty-five cwt. Ordinary wagons or trucks usually carry weight not exceeding 5, or, at most, 6 tons; and as there are in this building many blocks of granite and freestone of 10 to 20 tons, the difficulty of carriage can easily be seen. In hoisting and fixing these large stones ‘travellers’ are used, which can move longitudinally and crossways; and as the lift is directly over the stone to be fixed, there is less liability of accident than by the use of cranes or other contrivances.

“The building progresses as rapidly as the elaborate nature of such work will admit. It is now to the height of the first story, twenty-five feet from the floor line, which is three feet above the causeway in George street. The works are being carried on under the superintendence of the Colonial Architect, Mr. James Barnet. The contractor has fixed all the polished granite columns on the work front facing the street, which is to be taken through from George street to Pitt street. They are exceedingly beautiful, and are resplendent with a lustre brighter than that of marble. The polish has been brought out by an elaborate process, and is, we believe, ineffaceable by atmospheric [Pg 85] influences. Each column is polished by machinery—incessant friction continued for a fortnight being requisite to bring out the lustre. There are to be twenty-seven columns in the George street front, which the Government have also decided shall be of polished granite, material which for beauty and durability cannot be surpassed even in Europe. The building, when completed, will compare favorably with any structure erected for a similar purpose elsewhere.

“The blue granite used in the edifice is obtained by Mr. Young from his quarries at Moruya, about one hundred and sixty miles to the south of Sydney. The quarries are opened in the side of the hill—a mountain of granite in fact—and about half a mile of railway constructed across the swamp carries it to a granite jetty, which has been built in the river, into water deep enough to admit of vessels drawing fifteen feet of water loading alongside. The granite is sound—sufficiently so, indeed, to admit of two hundred feet lengths being quarried. A block has been got out for the front columns of the Post Office, which weighs nearly three hundred tons, and the dimensions of which are:—Length, 22 feet; breadth, 22 feet; thickness, 8 feet; total contents being 3,520 feet.”

It is something to be wondered at, the slowness with which the advantages of concrete, as a building material, have been developed and accepted by practical men. As a foundation it is beyond all doubt the firmest, simplest, and most economical. But, its merit is not confined to underground operations; for, as has been repeatedly maintained during the last twenty years, it is capable of making walls of unsurpassing strength and durability, giving comforts which no other material will. It is true that certain parties have sought to astonish the world with securely patented inventions, by which Nature’s humble efforts at making granite were at once surpassed, and the old fogy way of the consolidation, by the tedious action of time, of grains of mica, quartz, and feldspar, set aside by the use of this invaluable mode of making as good an article with one man power at a rate fully equal to supplying the demands of all who want stone houses erected rapidly from the raw material!

All this is arrant folly, and should not be listened to, much less patronized. The making or undertaking to make stone in blocks is a step, aye, a long stride backwards.

The object of cementing together blocks, whether of brick or stone, is simply to produce one solid mass. And it is because we cannot conveniently carve out in a monolith or mass together in one tumulus the desired dwelling or temple, that we are forced either to break blocks of stone into fragments, or mould and burn earth into bricks. Now the idea of forming artificial stone into blocks still leaves the expensive necessity for cementing them together; and therefore instead of improving our condition, actually leaves us worse off, by giving us, as a substitute for Nature’s well-tested material, a most unreliable article, which has already too clearly proved its utter worthlessness. However, this should not cause the friends of progress to give up all idea of simplifying and economizing the mode of wall structure. On the contrary it should stimulate them to make that exertion in the right way, which has hitherto been so persistently and blindly made in the wrong.

In Europe they are taking this subject into serious consideration. In England, under the name of Concrete; in France, under the title of Béton. In the latter country, much has been done lately, and all arising out of the excellent work on cements given to [Pg 86] the world by M. Vicat, whose name should be enshrined forever in the Temple of Fame, for the amount of good, present and prospective, which his earnest labors have done the Art of Building.

One of the most indefatigable and successful of experimenters in béton is M. Coiquét, who has proved beyond all cavil the excellence of that composition when applied to the sustaining of weight or resistance of pressure.

In London we find Messrs. Drake, Brothers and Reed, under Her Majesty’s Letters-Patent, undertakers of Building in Concrete.

It is the machinery they use that is patented, we believe, and not the material; for there are many others in this branch of business. Mr. Joseph Tall, of London, has also a patent for a peculiar method of building in concrete, and has executed some contracts in Paris, where, in 1867, he took a prize at the Exposition.

It is evident, then, that concrete is forcing its way, and that it is not an unworthy subject for the inventive minds of our astute countrymen.

What we particularly need in order to give an impetus to construction in concrete is a well-systematized apparatus, movable and always available, and that men should be drilled to work to the greatest possible advantage; for it is the want of these requisites that makes concrete to-day a material so little known and so seldom used.

Let an active company, with sufficient capital, start the business in any of our large cities, and concrete will soon assert its excellence as a building material, and an investment will be secured, giving profit to its holders and satisfaction to a very large section of our population, to whom economy must prove the key to comfortable independence.

The quarry companies in Connecticut were never doing a heavier business than this season. Three quarries now employ over one thousand laborers, seventy-five horses and one hundred yoke of cattle.

How few there are who pause for one instant from their plodding after the deified “Dollar,” to reflect that this present year, 1869, is the most remarkably commemorative of any yet on the Book of Time.

It is now one hundred years since Humboldt, Cuvier, the first Brunell, James Watt, Jr., and Sir Thomas Lawrence, among the most eminent of the world’s civilians—and Napoleon the First, Wellington, Soult and Ney, among the most advanced rank of mighty military chiefs, had birth.

It is one hundred years since the elder Watt’s condensing steam engine was invented, and that invention which brought poverty with its production has, in these hundred years, revolutionized the globe, and made not alone individuals, but whole nations wealthy and powerful.

No nation on the globe owes more to Watt’s steam engine than does this of ours. Where now would Civilization be coiled up? Where now would Science be secluded comparatively unnoticed and unknown—were it not for that one invention?

The peoples of the world have been growing and multiplying, and where would have been the room, or the employment for the teeming millions, were it not for that happy thought which in 1769 became a palpable fact?

A wise Providence was over all, and the brain that worked out the idea of the condensing steam engine was but doing its special part in the great work of civilization and progress.

This Centenary is one which should not be allowed to pass unheeded, especially now that we have just drawn the extremes of the earth nearer, not alone to the ear, but to the eye itself.

“How fast they build houses now!” said H.; “they began that building last week, and now they are putting in the lights.” “Yes,” answered his friend, “and next week they will put in the liver.”

An important discovery connected with the raising of water is claimed to have been made by Dr. Bouron, a physician of some reputation, residing at Heverville, Seine Inférieure. It appears that by a very simple piece of mechanism he can raise a continuous stream of water to almost any altitude, without labor of any kind, and without expense, beyond that necessary for the first cost of the machine, and this is by no means large, considering the amount of useful work which it yields. Dr. Bouron states that the power of the machine is based upon a natural and immutable mechanical principle, and that by it there may be created a continuous current of water at the surface of the soil, wherever there exists, no matter at what depth it may be, a spring of water. The machine is intended to supersede all existing pumps, its construction not being more expensive, whilst it has the additional advantage that no expense is incurred for keeping it constantly and usefully at work, although other pumps, especially when the water is raised a great height, necessitates enormous expenses compared with the useful effect produced, and that, too, during the whole time they are at work. It must not be forgotten, however, that it is a stream and not a jet of water which the new machine produces, so that, although it would be well adapted to supply water to fire engines, for example, it could not replace them. It is claimed that the machine will yield the same quantity of water as that being produced by the spring to which it is adapted, (less, of course, the loss inseparable from the working of all mechanical apparatus), and at any height, whether it be one thousand metres, two thousand metres, or more. Dr. Bouron also observes that, however paradoxical it may appear, he has found “the greater the height to which the water has to be raised the greater is the power of the machine.” But the relative proportion of the power to the speed is quite in conformity with the principles of mechanics. The greater the height to which the water has to be raised, the greater the power and the speed that can be brought to bear upon it; but the greater the horizontal section of the column of water to be lifted, the more will the speed diminish.

The first masonic funeral that ever occurred in California took place in the year 1849, and was performed over the body of a brother found drowned in the Bay of San Francisco. An account of the ceremonies states that on the body of the deceased was found a silver mark of a Mason, upon which were engraved the initials of his name. A little further investigation revealed to the beholder the most singular exhibition of Masonic emblems that was ever drawn by the ingenuity of man upon the human skin. There is nothing in the history or traditions of Freemasonry equal to it. Beautifully dotted on his left arm in red or blue ink, which time could not efface, appeared all the emblems of the entered apprentice. There were the Holy Bible, the square and the compass, the 24-inch gauge and the common gavil. There were also the mosaic pavement representing the ground floor of King Solomon’s Temple, the intended tessle which surrounds it and the blazing star in the centre. On his right arm, and artistically executed in the same indelible liquid, were the emblems pertaining to the fellow craft degree, viz.: the square, the level, and the plumb. There were also the five columns representing the five orders of architecture—the Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Composite.

In removing the garments from his body, the Trowel presented itself, with all the other tools of operative Masonry. Over his heart was the [Pg 88] Pot of Incense. On the other parts of his body were the Bee Hive, the Book of Constitutions, guarded by the Tyler’s Sword, the sword pointing to a naked heart; the All-seeing eye; the Anchor and Ark, the Hour Glass, the Scythe, the forty-seventh problem of Euclid; the Sun, Moon, Stars, and Comets; the three steps emblematical of Youth, Manhood, and Age. Admirably executed was the weeping Virgin, reclining on a broken column, upon which lay the Book of Constitutions. In her left hand she held the Pot of Incense, the Masonic emblem of a pure heat, and in her uplifted hand a Sprig of Acacia, the emblem of the immortality of the soul. Immediately beneath her stood winged Time, with his scythe by his side, which cuts the brittle thread of life, and the Hour Glass at his feet which is ever reminding us that our lives are withering away. The withered and attenuated fingers of the Destroyer were placed amid the long and gracefully flowing ringlets of the disconsolate mourner. Thus were the striking emblems of mortality and immortality beautifully blended in one pictorial representation. It was a spectacle such as Masons never saw before, and, in all probability, such as the fraternity will never witness again. The brother’s name was never known.

Those of our citizens who were “to the manor born,” and never left their native land, cannot form any idea of the comfort they enjoy as compared with the misery endured from birth to death by thousands of kindred humanity in the other parts of the world. Even in highly cultivated and brilliant England and her dependencies, we find enough to shock the feelings and make us ask ourselves “can such things be?”

In a pamphlet recently given to the world, Dr. Morgan, a Master of Arts, and a prominent member of the British Medical Association, repeats in print a paper which he read before that learned body at Oxford, in August last; and but for which publication we would have been in ignorance of the actual depth of misery to which so many good and faithful subjects of that proud and wealthy monarchy are condemned uncared for and unthought of.

“The author remarks that the housing of the poor, while beset with great difficulties, is most intimately connected with the future prosperity of the great mass of the people. In all our great cities, there are unhealthy quarters, where the death rate is exceptionally high, and the reason of this, after careful inspection of many such places, Dr. Morgan believes is to be found in this statement. Bad air, or too little of it, kills the people.

“Men will grow robust and vigorous, the author remarks, on very poor food, in very dirty cabins, and in very sorry attire, provided they enjoy a pure and bracing atmosphere, and the great physical development of the nations of the Hebrides and the western highlands of Scotland is cited as an example. In striking contrast to this, we find that in the Isle of St. Kilda, a small island, numbering about eighty inhabitants, three out of every five infants born alive are carried off a few days after birth by a convulsive affection allied to tetanus, the difference being apparently due to the huts having no smoke-hole in the thatch, and being rendered impervious to air by double walls filled in with peat and sods, the object of which is to prevent the escape of smoke, and in due time the soot is collected and used as manure.”

Drinking Fountains—This philanthropic movement which offers the grateful cup of Nature’s refreshing beverage to the parched lip of the passenger, is one that takes a high place indeed in the church universal, at whose shrine all bend in unison, and know no discordant thought, but love one another for the love of God.

PRACTICAL GEOMETRY.

We will not commence our instructions with the hackneyed “definitions,” but give our readers full credit for the knowledge of what is a point, a right or straight line, a curved line, parallel lines—and so forth, and proceed at once to practice.

There are some persons who think that with a drawing-board and square, they can, without fail, make all sorts of horizontal, perpendicular, or parallel lines, and that therefore any geometrical rules for such purpose are to them unnecessary. But, suppose the drawing-board, or the square is absent, or that neither can be had. In such an emergency the want of the following items of knowledge would be severely felt, and, therefore, the acquirement and retention of them is something desirable, and even highly necessary.

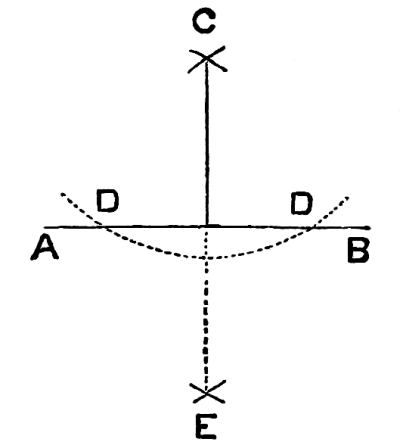

Problem I. To erect a perpendicular on a given right line.

Fig. 1

A, B, is the given right line. From the point C, with a radius longer than the perpendicular distance describe the arc, or part of a circle, D, D. And from the points of intersection with the right line A, B, describe arcs cutting each other at C and E. Join C and E, and the perpendicular is obtained on either side of the right line A, B.

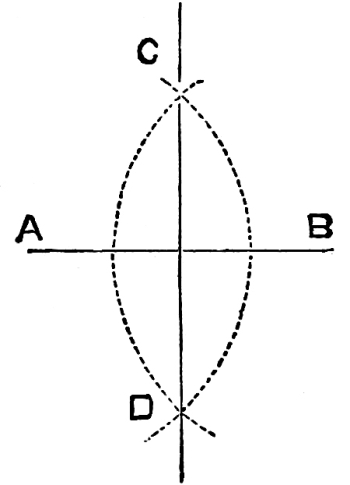

Problem II. To erect a perpendicular at the middle of a right line.

From the extreme points of the right line A, B, with radii less than the length of the line describe two arcs intersecting each other at C and D, and through the points of their intersection draw the line, which will be perpendicular to the given right line at the middle.

Fig. 2

In this way, too, may any line be divided into too equal parts with facility and exactness.

Problem III. To erect a perpendicular at or near the end of a given right line.

Fig. 3

Take any point, D, on the given right line A, B, as a centre, and to the required point C, as a radius, and describe an arc C, E, F. Take a portion of this arc, say E, and make from C, E, equal to E, F. Join F and C. Now with E, C, for a radius, describe the arc G, E, H, and make from E to H equal to from E to G. Then through H from C draw the perpendicular required.

There are other methods of accomplishing this, but we will not introduce them here, as the one now given is sufficient.

We will now proceed to the formation of geometrical figures which enclose space.

That which is bounded by one line is called a circle; and a right [Pg 90] line dividing it into two equal parts is called its diameter; from the centre of which to either end is called the radius: and the boundary line is termed the circumference from the Latin words circum, around, and fero to carry. That is: a line carried around. Thus we see an area or space is enclosed by one line. An area may be enclosed by two lines; but one, or both of them, must be curved; as two right lines cannot enclose a space. But three can; and the figure is called a triangle.

Problem IV. In a given circle to construct a Triangle.

Fig. 4

Take the radius of the circle, and with it mark off six points on the circumference. Take two of these lengths of the radius and join their extreme points A and B, which will be the base. Now take this base as a radius and describe alternately two arcs cutting each other at C. Join A, C, and B, C, and a triangle is formed, whose sides being equal is termed an equilateral triangle.

In order to ensure its being upright, erect a perpendicular at the centre, and let the two sides A, C, and B, C, meet that perpendicular where it intersects the circumferences. Or, begin the triangle at this point, and mark off two lengths of the radius, joining the extreme points as before; and do this at each side of the perpendicular; finally connecting the distant extremities of the two sides for a base.

Problem V. To construct an upright square in a given circle.

Let fall a perpendicular, I, E, from the centre to the circumference, and with that as a radius and E as a centre, cut the circumference at A, B, C, and D, and join the points. The four-sided figure called a square is thus formed.

Problem VI. On a given right line, A, B, to construct a pentagon, or five-sided figure.

Draw B, F, perpendicular and equal to the half of A, B. Produce A, F, to G, making F, G, equal to F, B. From the points A and B, with the radius B, G, describe arcs cutting each other at I. From I, with the radius I, B, describe a circle. Inscribe the successive chords A, E; E, D; D, C; C, B, which with the base A, B, completes the pentagon.

If the circle be given, and a pentagon to be inscribed in it, the following is as simple as it is practical. From the centre erect a perpendicular, which shall meet the circumference at D. At each side of this point divide the circumference into five equal parts, and connect every two of them from D to E, from E to A, and from D to C, C to B. Now connect A and B and the pentagon is formed.

Problem VII. On a given line A, B, to construct a hexagon, or six-sided figure.

[Pg 91] Take the length of the radius I, G, and lay it off from F to A, A to B, B to C, C to D, D to E, and E to F.

Problem VIII. To form an octagon, or eight-sided figure.

Refer back to Fig. 5. Draw the radius I, E, till it meets the circumference at E. Join the points E, A, and E, B. Repeat this at each of the four sides, and the octagon is formed.

Problem IX. To form a decagon, or ten-sided figure.

Refer to Fig. 6, and proceed as in the preceding problem.

Problem X. To construct a duo-decagon, or twelve-sided figure.

Refer to Fig. 7, and duplicate the chords, as already shown.

We do not present 7, 9, or 11 sided figures, because they seldom or ever come into practice. Our object being to give what is useful and not overburden the memory unnecessarily.

The learner should go over and work out each of the foregoing problems several times. In fact, until they are soundly secured in his memory, so that on any emergency he can apply them to a required practice. They are the simplest rudiments, but as practically useful as they are simple. The Architect, the builder, as well as the several trades of carpenter, joiner, carver, stone-cutter, mason, and in fact, all in any way concerned in the practice of construction will at some time or other wish to recall one of these useful problems. Therefore do we dwell on the necessity for committing them, understandingly, to memory, and likewise the advantage required in being able to draw them neatly and perfectly on paper. In order to do this with satisfaction to one’s self, it is desirable that a fine point be constantly maintained on the pencil, and that uniform nicety be preserved with the curved lines, as well as the right or straight lines. For nothing looks worse than undue thickness in the one or the other. All should be alike.

In theoretical geometry a line, whether right or curved, is but imaginary, not having any thickness whatever, and therefore no palpable existence. In practical geometry the line must be visible, but ought to be so uniformly fine as to occupy scarcely any perceptible thickness. And herein lies the greatest beauty in geometrical draughting. By strict attention to this apparently trifling matter, its advantages will show wherever minute angles occur. They will be clear and distinct, and always satisfactory.

The learner should keep his first attempts, however coarse, for they will by comparison hereafter, show the advance he has made. Nor should he be content to “let well enough alone.” There is no “well enough” in drawing. It is a progressive science, and the true artist never believes he has done his best. Go as near to perfection as you can, and do not turn aside from, or step over obstacles to reach the end you have in view. Whatever you have neglected in early study will surely haunt you through after years, and trouble you when you can least bear the annoyance.

We now conclude this primary lesson, hoping that our learners may profit by the hints we have thrown out, and will thoroughly prepare themselves for the advance in our next.

The first brick house in Iowa was built by Judge Rerer, of Burlington, in 1839.

THE GROUND NUT VINE.