TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter. Four digit items such as [1466] are not footnote anchors but refer to a year.

Macrons over e and u are displayed correctly as ē and ū. Some latin abbreviations are shown in the original text with an overline, for example Hiberniæ when abbreviated is displayed in the etext as Hibniæ, similarly to the original text.

Basic fractions are displayed as ½ ¼ ¾; there are no other fractions in this book.

Date ranges are displayed using – for example 1621–8, the same as the original text.

Split-year dates are displayed similarly to the original text, for example 160 0 1 . The dual dates indicate the Julian (1600) and the Gregorian (1601) year designation for dates between January 1st and March 25th. Prior to 1752 dates in documents in British dominions used the Julian calendar, in which the new year did not begin until March 25th.

On a handheld device the tables on pages 288 and 289 are best displayed using a small font to avoid truncation of the columns.

Some other minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

TERCENTENARY CELEBRATION

JULY, 1892

PRESENTED

BY THE

PROVOST AND SENIOR FELLOWS

OF

TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN

Virginis os habitumque geris, diuina virago,

Sed supra sexum dotes animumque virilem;

Quod sæpe altarum docuit rerum exitus ingens:

Vnde tibi et Regni populi debere fatentur,

Christiadumque cohors, odijs rumpantur vt hostes,

Quorum Diua tua rabies nil morte lucrata est.

Vasta Semiramiden Babylon super æthera tollat,

Efferat et Didona suam Sidonia tellus,

Gens Esthren Iudæa, Camillam Volsca propago,

Aut Constantini matrem Byzantion ingens,

Atqúe alias aliæ gentes: tete Anglia fortis

Vt quondam fructa est, sic nunc clarescat alumna.

1591

1891

BELFAST

MARCUS WARD & CO., LIMITED, ROYAL ULSTER WORKS

LONDON AND NEW YORK

DUBLIN: HODGES, FIGGIS & CO., LIMITED

1892

The Committee appointed by the Provost and Senior Fellows of Trinity College, Dublin, to make arrangements for the celebration of the Tercentenary of the Foundation of the University of Dublin and of Trinity College, to be held in July, 1892, requested the following to act as a Sub-Committee to superintend the bringing out of a volume in which there should be a record of the chief events of the College for the last three centuries, a description of its buildings, &c.:—

Rev. John W. Stubbs, D.D.

Rev. Thomas K. Abbott, B.D., Litt.D., Librarian.

Rev. John P. Mahaffy, D.D., Mus. Doc.

Edward Dowden, LL.D., Litt.D.

Ulick Ralph Burke, M.A.

William MacNeile Dixon, LL.B., and

E. Perceval Wright, M.A., M.D.;

the last named to be the Convener.

Through illness, Professor E. Dowden was unable to take any active part in the preparation of this volume, the publication of which was undertaken by the firm of Messrs. Marcus Ward & Co., Limited, of Belfast. The time at the disposal of the writers of the following chapters was extremely short, and they tender an apology for the want of completeness, which, on an exact scrutiny of their work, will, they fear, be only too conspicuous; but it is hoped that the volume may be acceptable as a sketch towards a History of the College.

The name of the writer of each chapter is given in the Table of Contents, and each author is to be regarded as accountable only for his own share of the work. The Committee’s grateful thanks are due to Mr. Louis Fagan, of the Department of Prints and Drawings, British Museum, for the help he has given them in having reproductions made from rare engravings of some of the distinguished Graduates of the University.

| PAGE | |||

| Chapter | I.— | From the Foundation to the Caroline Charter, by the Rev. J. P. Mahaffy, D.D., | 1 |

| ” | II.— | From the Caroline Reform to the Settlement of William III., by the Rev. J. P. Mahaffy, D.D., | 29 |

| ” | III.— | The Eighteenth Century up to 1758, by the Rev. J. P. Mahaffy, D.D., | 47 |

| ” | IV.— | From 1758 to the Close of the Century, by the Rev. J. P. Mahaffy, D.D., | 73 |

| ” | V.— | During the Nineteenth Century, by the Rev. J. W. Stubbs, D.D., | 91 |

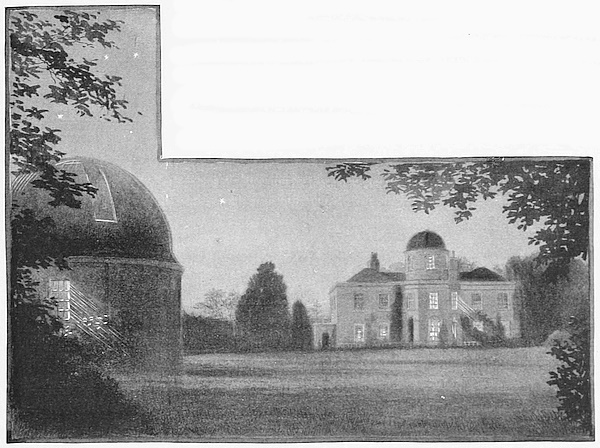

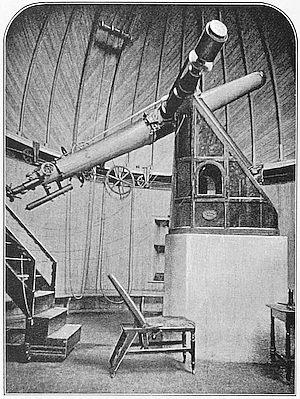

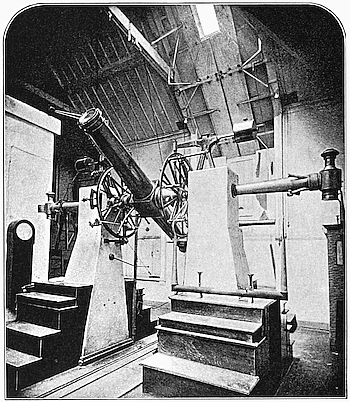

| ” | VI.— | The Observatory, Dunsink, by Sir Robert Ball, LL.D., Astronomer-Royal, | 131 |

| ” | VII.— | The Library, by the Rev. T. K. Abbott, B.D., Litt.D., Librarian, | 147 |

| ” | VIII.— | The Early Buildings, by Ulick R. Burke, M.A., | 183 |

| ” | IX.— | Distinguished Graduates, by William MacNeile Dixon, LL.B., | 235 |

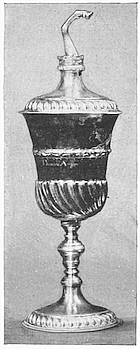

| ” | X.— | The College Plate, by the Rev. J. P. Mahaffy, D.D., | 267 |

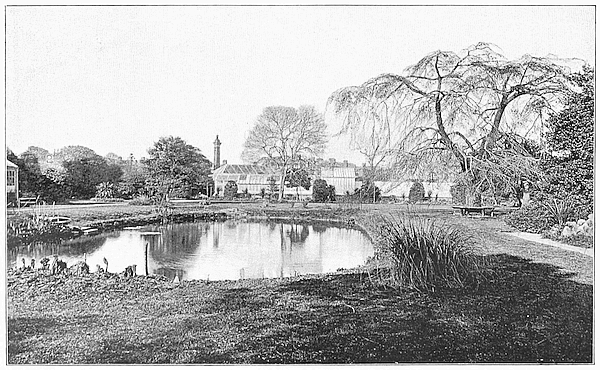

| ” | XI.— | The Botanical Gardens and Herbarium, by E. Perceval Wright, M.A., M.D., | 275 |

| ” | XII.— | The University and College Officers, 1892, | 285 |

| Tercentenary Ode, | 291 | ||

| PAGE | |

| Portrait of Queen Elizabeth, | Frontispiece. |

| The Oldest Map of the College, | 7 |

| Fac-simile of Provost Ashe’s Prayer, | 10 |

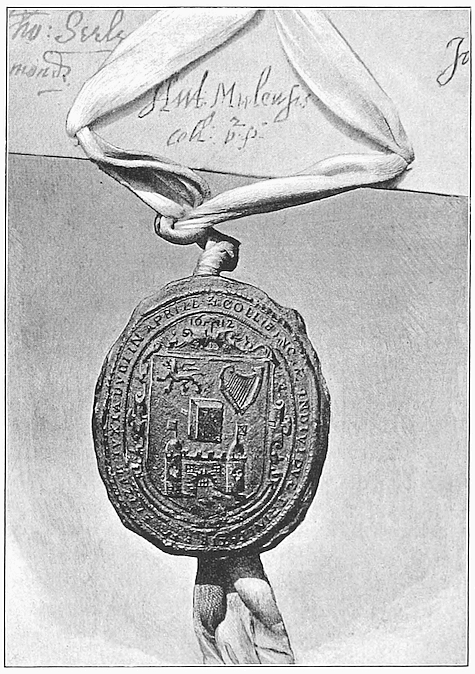

| The Earliest extant College Seal, | 11 |

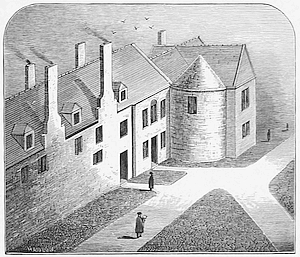

| The South Back of the Elizabethan College, | 25 |

| Fac-simile of Title-page, Archbishop Marsh’s “Logic,” | 37 |

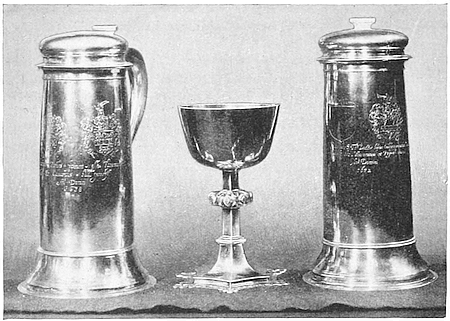

| Chapel Plate (dated 1632 and 1638), | 44 |

| Title-page of the Centenary Sermon, January 9, 169 3 4 , | 52 |

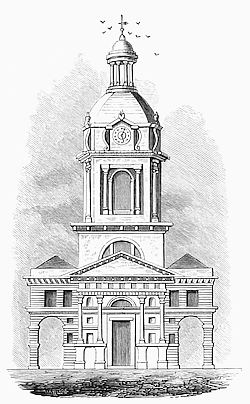

| The old Clock Tower, | 62 |

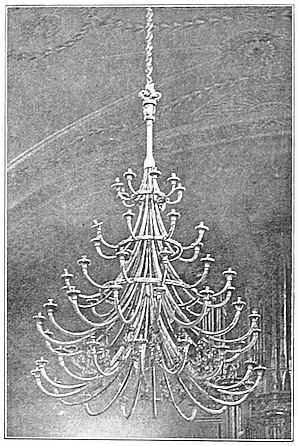

| Candelabrum, Examination Hall, | 130 |

| Dunsink Observatory, | 133 |

| South Equatorial, Dunsink, | 142 |

| Meridian Room, Dunsink, | 144 |

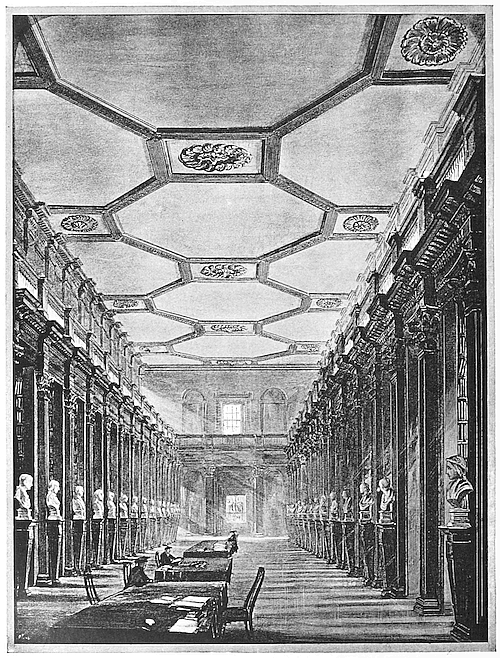

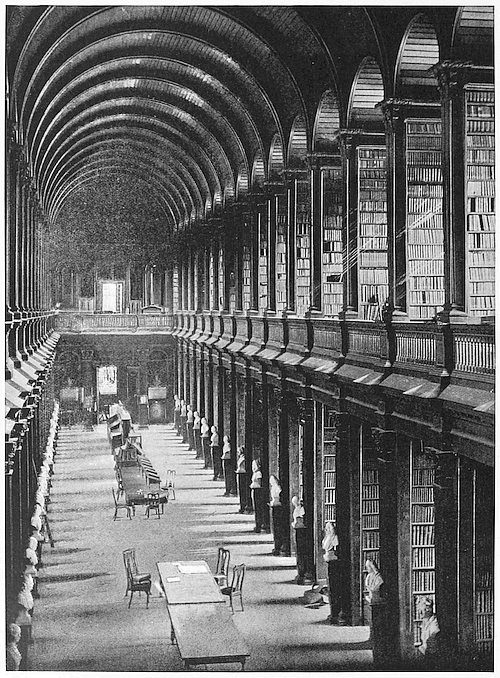

| Old Print of Library, 1753, | 152 |

| Interior of Library, 1858, | 154 |

| A Page from the “Book of Kells,” | 161 |

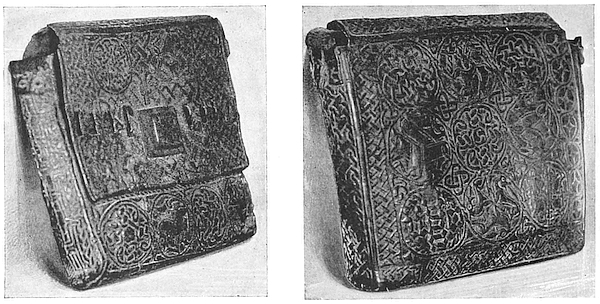

| Satchel of the “Book of Armagh,” | 164 |

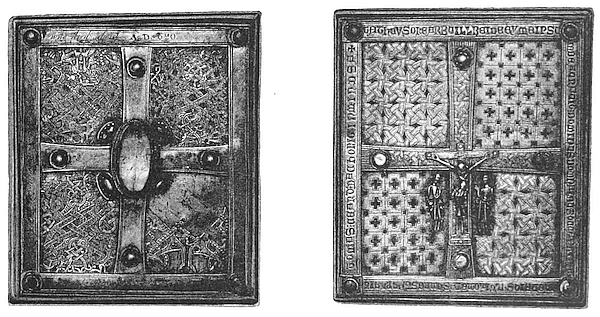

| Shrine of the “Book of Dimma,” | 165 |

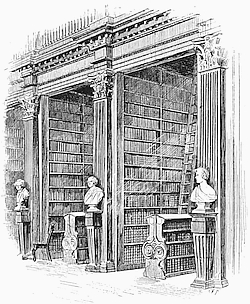

| Book Recesses in Library, | 176 |

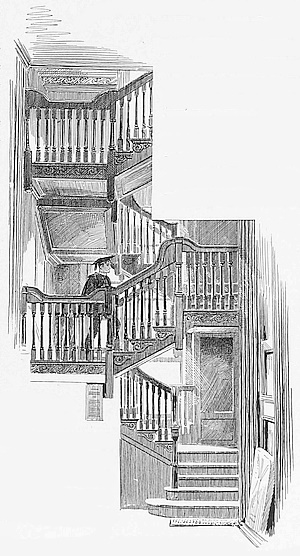

| Inner Staircase in Library, | 177 |

| Interior of Library, 1860, | 178178 |

| The Library, 1891, | 179179 |

| Library Staircase and Entrance to Reading Room, | 180 |

| Royal Arms now placed in Library, | 181 |

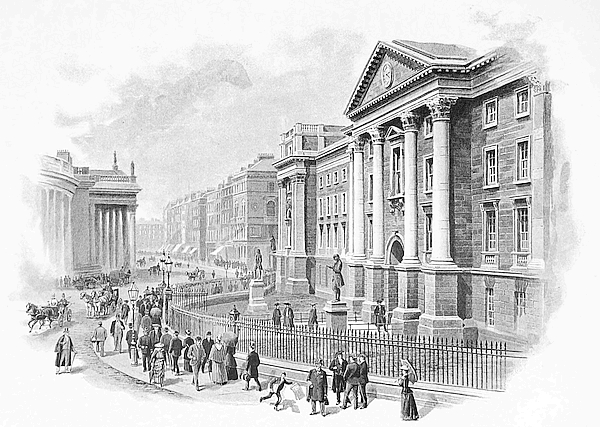

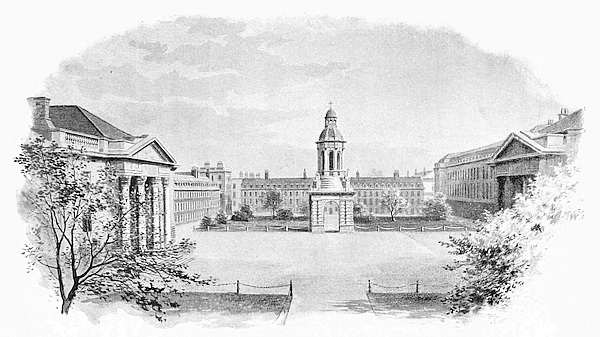

| Front of Trinity College, 1728, | 183 |

| Ground Plan of Trinity College, from Rocque’s Map of Dublin, 1750, | 187 |

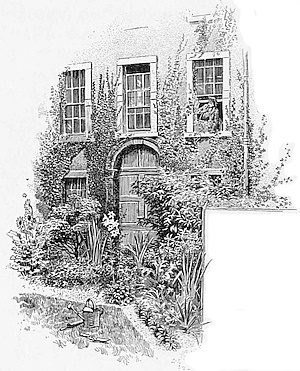

| Ampelopsis veitchii, | 190 |

| Trinity College—West Front, | 191191 |

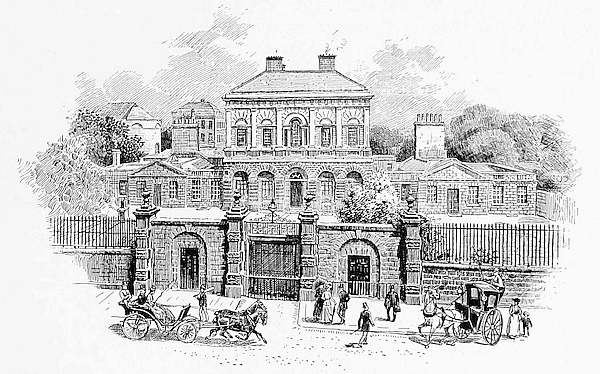

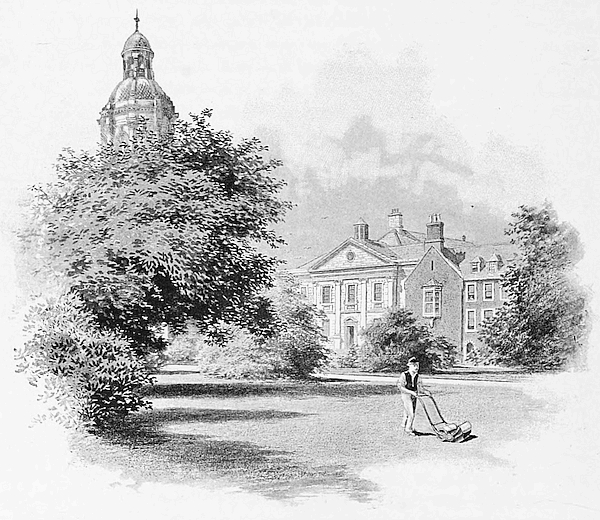

| The Provost’s House, from Grafton Street, | 195 |

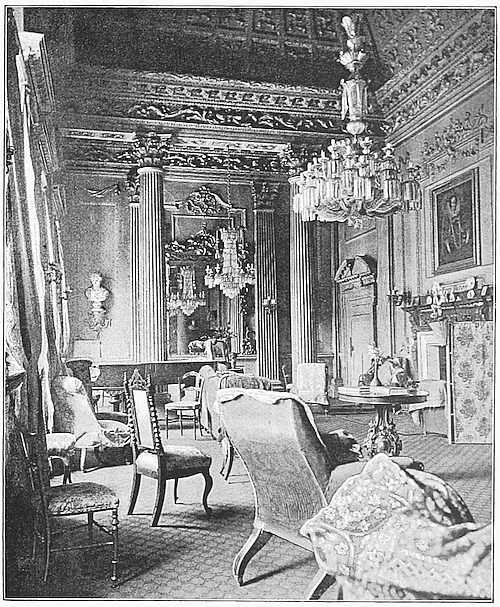

| Drawing Room, Provost’s House, | 197 |

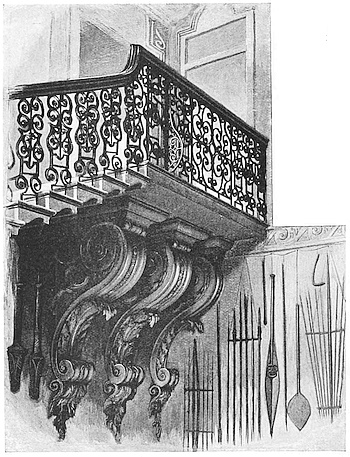

| Top of Staircase, Regent’s Hall, | 200 |

| Parliament and Library Squares, | 201201 |

| Library Square, | 202202 |

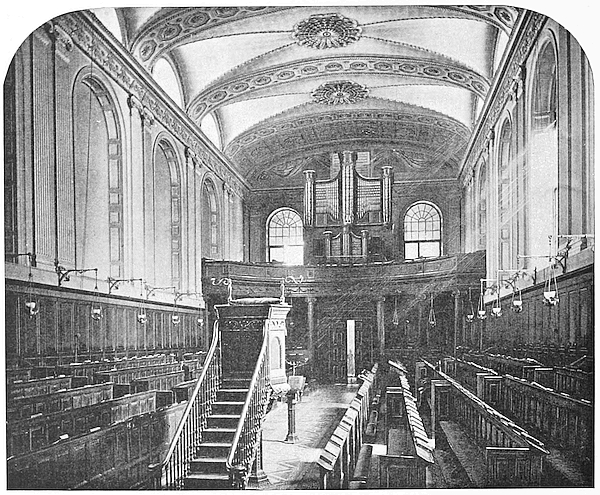

| The Chapel, | 204 |

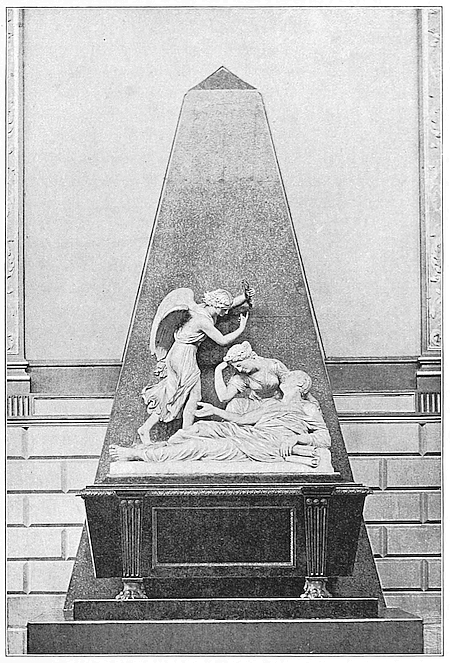

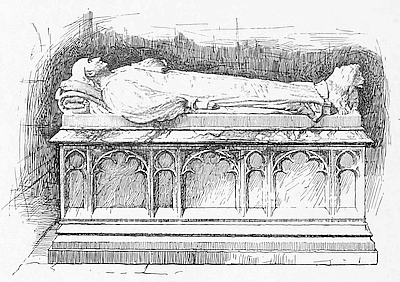

| Baldwin’s Monument, | 211 |

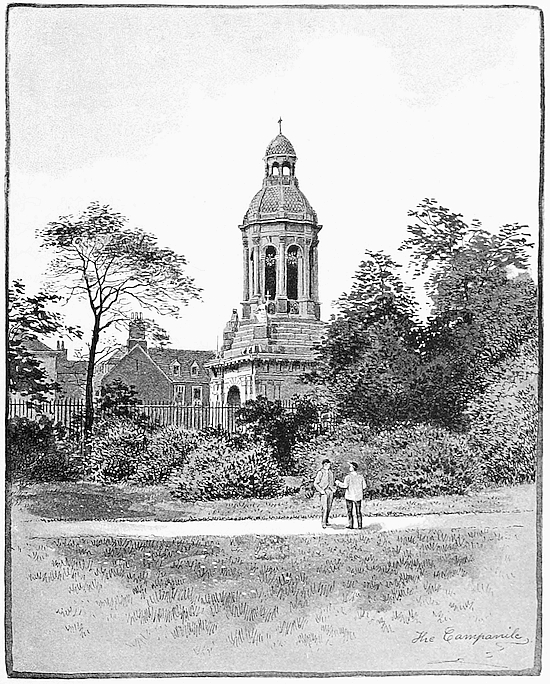

| The Bell Tower, from the Provost’s Garden, | 215 |

| The Dining Hall, viewed from Library Square, | 218 |

| Interior of Dining Hall, | 219 |

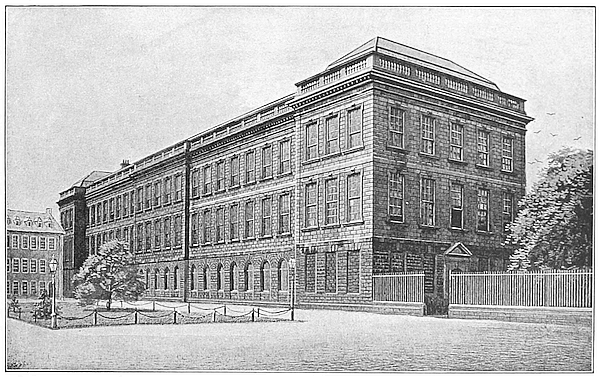

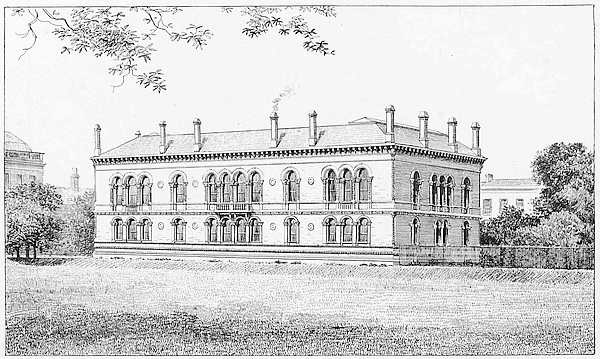

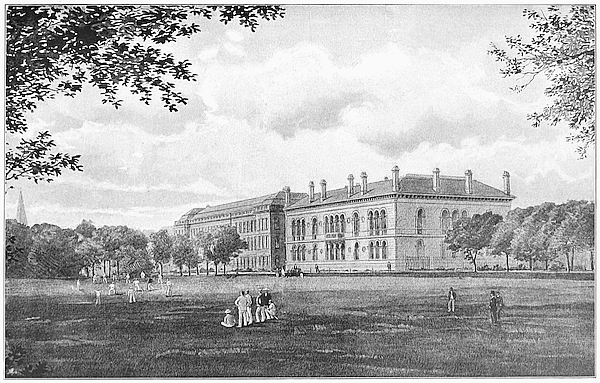

| The Engineering School, from College Park, | 220 |

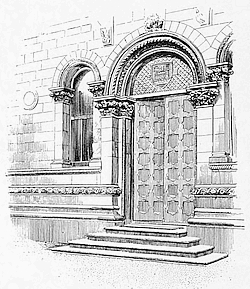

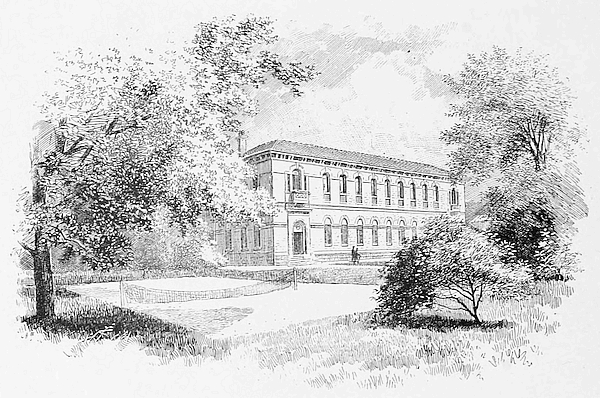

| Entrance to Engineering School, | 222 |

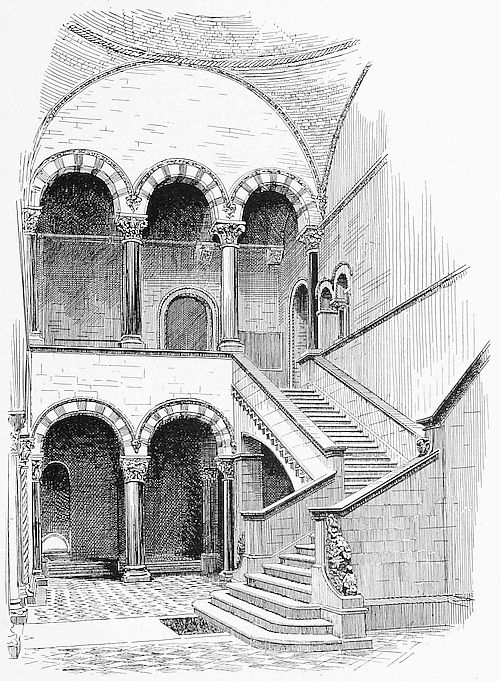

| Hall and Staircase, Engineering School, | 223 |

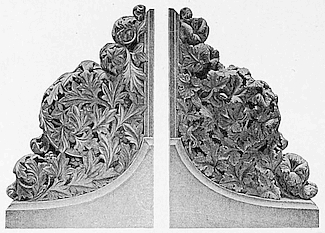

| Carvings at Base of Staircase, | 224 |

| The Printing Office, from New Square, | 225 |

| View in the College Park—Library—Engineering School, | 228 |

| The Medical School, | 229229 |

| The Museum (Tennis Court), | 230 |

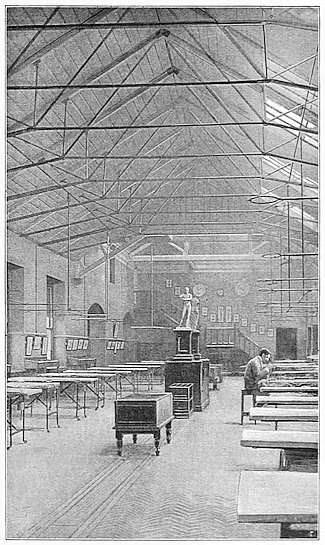

| The Dissecting Room, | 231 |

| The Printing Office, | 233 |

| Pulpit in Dining Hall, | 234 |

| Portrait of Archbishop Ussher, | 238 |

| Portrait of William King, D.D., | 241 |

| Bust of Dr. Delany, | 243 |

| Portrait of William Molyneux, | 244 |

| Bust of Dean Swift, | 244 |

| Portrait of Thomas Southerne, | 245 |

| Portrait of William Congreve, | 247 |

| Portrait of Bishop Berkeley, | 249 |

| Portrait of Earl of Clare, | 256 |

| Portrait of Lord Plunket, | 258 |

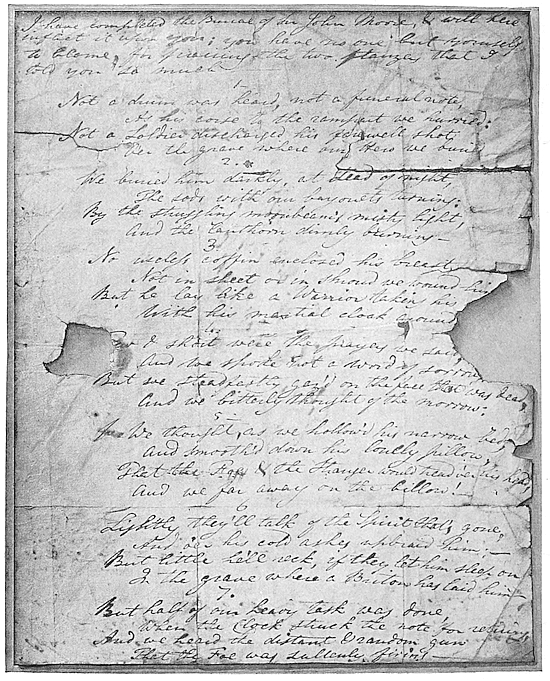

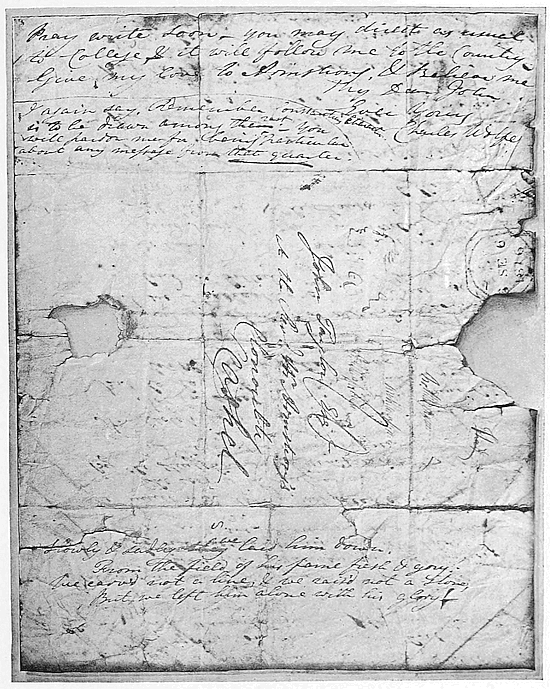

| Fac-simile of Original MS. of “The Burial of Sir John Moore,” | 260, 261 |

| Bust of James MacCullagh, | 263 |

| Portrait of Charles Lever, | 263 |

| Tomb of Bishop Berkeley, | 264 |

| Communion Cups—Meade, 1760; Garret Wesley, 1751; Caufield, 1690, | 267 |

| Salver—Gilbert, 1734, | 268 |

| The College Mace, | 271 |

| Punch Bowls—Plunket, 1702; Meade, 1708, | 272 |

| Duncombe Cup, 1680; Palliser Cup, 1709, | 273 |

| Epergne (Reign of George II.), | 274 |

| Botanical Gardens—The Pond. Winter, | 281 |

Laudamus te, benignissime Pater, pro serenissimis,

Regina Elizabetha hujus Collegii conditrice,

Jacobo ejusdem munificentissimo auctore,

Carolo conservatore,

Ceterisque benefactoribus nostris.

The Caroline Grace.

The origin of the University of Dublin is not shrouded in darkness, as are the origins of the Universities of Bologna and Oxford. The details of the foundation are well known, in the clear light of Elizabethan times; the names of the promoters and benefactors are on record; and yet when we come to examine the dates current in the histories of the University and the relative merits of the promoters, there arise many perplexities. The grant of the Charter is in the name of Queen Elizabeth, and we record every day in the College our gratitude for her benefaction; but it is no secret that she was urged to this step by a series of advisers, of whom the most important and persuasive remained in the background.

The project of founding a University in Ireland had long been contemplated, and the current histories record various attempts, as old as 1311, to accomplish this end—attempts which all failed promptly, and produced no effect upon the country, unless it were to afford to the Roman Catholic prelates, who petitioned James II. to hand over Trinity College to their control, some colour for their astonishing preamble.[2] It is not the province of these chapters to narrate or discuss these earlier schemes. One feature they certainly possessed—the very feature denied them in the petition just named. Most of them were essentially ecclesiastical, and closely attached to the Cathedral corporations. There seems never to have been a secular teacher appointed in any of them—not to speak of mere frameworks, like that of the University of Drogheda. Another feature also they all present: they are without any reasonable endowment, the only serious offer being that of Sir John Perrott in 1585, who proposed the still current method of exhibiting English benevolence towards Ireland by robbing one Irish body to endow another. In this case, S. Patrick’s Cathedral, “because it was held in superstitious reverence by the people,” was to be plundered of its revenues to set up two Colleges—one in Armagh and one in Limerick. This plan was thwarted, not only by the downfall of its originator (Perrott), but by the active opposition of an eminent Churchman—Adam Loftus, the Archbishop of Dublin. The violent mutual hostility of these two men may have stimulated each to promote a public object disadvantageous to the other. Perrott urged the disendowment of S. Patrick’s because he knew that the Archbishop had retained a large pecuniary interest in it. Perhaps Loftus promoted a rival plan because he feared some future revival of Perrott’s scheme. Both attest their bitter feelings: for in his defence upon his trial Perrott calls the Archbishop his deadly enemy; and Loftus, in the Latin speech made in Trinity College when he resigned the Provostship, takes special credit for having resisted the overbearing fury of Perrott, and having gained for Leinster the College which the other sought to establish either in Armagh or Limerick, exposed to the dangers of rebellion and devastation.[3] But before this audience, who knew the circumstances, he does not[3] make any claim to have been the original promoter of the foundation. Even in his defence of S. Patrick’s, he had a supporter perhaps more persuasive, because he was more respected. It is mentioned in praise of Henry Ussher, “he so lucidly and with such strength of arguments defended the rights of S. Patrick’s Church, which Perrott meant to turn into a College, that he averted that dire omen.”[4] Nevertheless, the Archbishop is generally credited with being the real founder of Trinity College, and indeed his speeches to the citizens of Dublin, of which two are still extant, might lead to that conclusion. But other and more potent influences were at work.

Some years before, Case, in the preface to his Speculum Moralium Quæstionum (1585), had addressed the Chancellors of Cambridge and Oxford conjointly on the crying want of a proper University, to subdue the turbulence and barbarism of the Irish. This appeal was not original, or isolated, or out of sympathy with the age. Such laymen as Spencer, and as Bryskett, Spencer’s host near Dublin, must have long urged similar arguments. In 1547, Archbishop George Browne had forwarded to Sir William Cecil a scheme for establishing a College with the revenues of the then recently suppressed S. Patrick’s.[5] Another scheme is extant, endorsed by Cecil, dated October, 1563, with salaries named, but not the source of the endowment. In 1571, John Ussher, in applying for the rights of staple at the port of Dublin, says in his petition that he intends to leave his fortune to found a College in Dublin. In 1584, the Rev. R. Draper petitions Burghley to have the University founded at Trim, in the centre of the Pale, as this site possessed a waterway to Drogheda, and was furnished with great ancient buildings, then deserted, and falling into decay.

But in addition to these appeals of sentiment, there were practical men at work. Two successive Deputies, Sir Henry Sidney and Sir John Perrott, had urged the necessity of some such foundation (1565, 1585), and the former had even offered pecuniary aid. The Queen, long urged in this direction, had ultimately been persuaded, as appears[4] from her Warrant, that the City of Dublin was prepared to grant a site, and help in building the proposed College; and the City, no doubt, had been equally persuaded that the Queen would endow the site. The practical workers in this diplomacy have been set down in history as Cambridge men. This is one of those true statements which disguise the truth. The real agitators in the matter were Luke Challoner and Henry Ussher. A glance at Mr. Gilbert’s Assembly Rolls of the City of Dublin the reign of Elizabeth will show how both family names occur perpetually in the Corporation as mayors, aldermen, etc.[6] The very site of the future College had been let upon lease to a Challoner and to the uncle of an Ussher.[7] These were the influential City families which swayed the Corporation. Henry Ussher,[8] who had become Archdeacon of Dublin, went as emissary to Court; Challoner[9] superintended the gathering of funds and the laying out of the site, which his family had rented years before. It was therefore by Dublin men—by citizens whose sons had merely been educated at Cambridge, and had learned there to appreciate University culture—that Trinity College was really founded. They had learned to compare Cambridge and Oxford, with Dublin, life, and when they came home to their paternal city, they felt the wide difference.

Queen Elizabeth, in her Warrant, puts the case quite differently. She does not, indeed, make the smallest mention of Loftus, but of the prayer of the City of Dublin, preferred by Henry Ussher, thus:

December 29, 1592.

Elizabeth, R.

Trustee and right well beloved we greet you well, where[as] by your Lrēs, and the rest of our Councell joyned with you, directed to our Councell here, wee perceive that the Major and the Cittizens of Dublin are very well disposed to grant the scite of the Abbey of Allhallows belonging to the said Citty to the yearly value of Twenty pounds to serve for a Colledge for learning, whereby knowledge and Civility might be increased by the instruction of our people there, whereof many have usually heretofore used to travaile into[5] ffrance Italy and Spaine to gett learning in such forreigne universities, whereby they have been infected with poperie and other ill qualities, and soe became evill subjects, &c.[10]

The Usshers and the Challoners had no inclination to go to Spain or France, nor is it likely that they ever thought they would prevent the Irish Catholic priesthood from favouring this foreign education. They desired to ennoble their city by giving it a College similar to those of Oxford and Cambridge, and they succeeded.

The extant speech of Adam Loftus, to which I have already referred, makes no allusion to these things. His argument is homely enough. Guarding himself from preaching the doctrine of good works, which would have a Papistical complexion, he urges the Mayor and Corporation to consider how the trades had suffered by the abolition of the monasteries, under the previous Sovereign; how the city of Oxford and town of Cambridge have flourished owing to their Colleges; how the prosperity of Dublin, now depending on the presence of the Lord Deputy and his retinue and the Inns of Court, will be increased by a College, which would bring strangers, and with them money, to the citizens. Thus it will be a means of civilising the nation and enriching the city, and will enable many of their children to work their own advancement, “and in order thereto ye will be pleased to call a Common Council and deliberate thereon, having first informed the several Masters of every Company of the pregnant likelihood of advantage,” etc. Again, “it is my hearty desire that you would express your and the City’s thankfulness to Her Majesty,” etc.

This harangue, in which “our good Lord the Archbushopp” gives himself the whole credit of the transaction, is said to have been delivered “soon after the Quarter Sessions of St. John the Baptist”—viz., about July, but in what year I cannot discover. Mr. Gilbert says, “after Easter, in the year 1590.” In Loftus’ Latin speech occurs—“As soon as I had proposed it to the Mayor and Sheriffs, without any delay they assembled in full conclave and voted the whole site of the monastery.” But in the meetings of the Dublin Council there is no allusion whatever to this speech, no thanks to the Queen, no resolution on the matter whatever, till under the date “Fourth Friday after December, 1590” (33 Elizabeth), we find the following modest business entry:—“Forasmoch as there is in this Assembly by certayne well-disposed persons petition[6] preferred,[11] declaring many good and effectual persuacions to move our furtherance for setting upp and erecting a Collage for the bringing upp of yeouth to learning, whereof we, having a good lyking, do, so farr as in us lyeth, herby agree and order that the scite of Alhallowes and the parkes thereof shalbe wholly gyven for the erection of a Collage there; and withall we require that we may have conference with the preferrers of the said peticion to conclude how the same shalbe fynished.”[12] The Queen’s Warrant is signed the 29th December, 1592 (34 Elizabeth).[13] It is hard to find any logical place for the Archbishop’s speech, either before, between, or after these dates and documents.

At all events, the Queen gave a Warrant and Charter, some small Crown rents on various estates in the South and West of Ireland, and presently, upon further petition, a yearly gift of nearly £400 from the Concordatum Fund, which latter the College enjoyed till the present century, when it was resumed by the Government. From the Elizabethan Crown rents the College now derives about £5 per annum. The Charter was surrendered for that of Charles I.

Thus the benevolences of Elizabeth, like the buildings of her foundation, have dwindled away and disappeared.

The Archbishop’s sounding words have had their weight in benefiting his own memory, as has been shown, beyond his merits in this matter.

The modest gift of the Corporation of Dublin, consisting of 28 acres of derelict land[7] partly invaded by the sea, has become a splendid property, in money value not less than £10,000 a-year, in convenience and in dignity to the College perfectly inestimable.

The necessary sum for repairing the decayed Abbey of All Hallowes, and for what new buildings the College required, was raised by an appeal of the Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam (dated March 11, 1591) to the owners of landed property all over Ireland. The list of these contributions is very curious, and also very liberal, if we consider that the following sums represent perhaps eight times as much in modern days:—

| £ | s. | d. | £ | s. | d. | ||

| “The Lord Deputy, | 200 | 0 | 0 | Advanced by his means in the Province of Munster, | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Archbishop Adam Loftus, | 100 | 0 | 0 | Sir Francis Shane, | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Sir Thomas Norreys, Vice-President of Munster, | 100 | 0 | 0 | ” ” a-year for his life, | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| [8] Sir Warham St. Leger, | 50 | 0 | 0 | Sir Henry Harrington, | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Sir Richard Dyer, | 100 | 0 | 0 | Thomas Jones, Bishop of Meath, | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Sir Henry Bagnall, | 100 | 0 | 0 | The gentlemen of the Barony of Lecale, | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| Sir Richard Bingham, | 20 | 0 | 0 | Sir Hugh M‘Ginnis, with other gentlemen of his county [Down], | 140 | 0 | 0 |

| The Province of Connaught by same, | 100 | 0 | 0 | The clergy of Meath, | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| The County of Galway by same, | 100 | 0 | 0 | Thomas Molyneux, Chancellor of the Exchequer, | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| The town of Drogheda, | 40 | 0 | 0 | Luke Chaloner, D.D., | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| The city of Dublin, | 27 | 0 | 0 | Edward Brabazon, | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| A Concordatum from the Privy Council, | 200 | 0 | 0 | Sir George Bourchier, | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| Alderman John Foster (for the Iron-work), | 30 | 0 | 0 | Christopher Chartell, | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Lord Chief Justice Gardiner, | 20 | 0 | 0 | Sir Turlough O’Neill, | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Lord Primate of Ireland [Garvey], | 76 | 0 | 0 |

“These sums amount to over £2,000, and they must have been considerably supplemented, for we have a return made by Piers Nugent with respect to one of the baronies in the County of Westmeath, in which he gives the names of eleven gentlemen in that barony who are prepared to contribute according to their freeholds, proportionally to other freeholders of Westmeath.

“Money, however, came in very slowly, specially from the South of Ireland; Sir Thomas Norreys informed Dr. Chaloner that the County of Limerick agreed to give 3s. 4d. out of every Plough-land, and he promised to do his best to draw other counties to some contribution, but he adds, ‘I do find devotion so cold as that I shall hereafter think it a very hard thing to compass so great a work upon so bare a foundation.’

“Dr. Luke Chaloner seems to have been the active agent in corresponding with the several contributors, and to have been most diligent in collecting subscriptions.”[14]

The coldness of Limerick—perhaps disappointed at the failure of Perrott’s scheme—contrasted with the zeal of Dublin. Dr. Stubbs quotes from Fuller, the Church historian, a statement which the latter had heard from credible persons then resident in Dublin, that during the building of the College—that is to say, for over a year—it never rained, except at night. This historically incredible statement is of real value in showing the feelings of the people who were persuaded of it. The great interest and keen hopes of the city in the founding of the College are expressed in this legendary way.

Thus by the earnestness and activity of some leading citizens of Dublin, supported by[9] the voice of educated opinion in Cambridge, the eloquence of the Archbishop, and the sound policy of Queen Elizabeth’s advisers, Trinity College was founded. The foundation-stone was laid by the Mayor of Dublin, Thomas Smith, and for at least 150 years the liberality of the Corporation of Dublin was commemorated in our prayers.

“We give Thee thanks for the Most Serene Princess Elizabeth, our most illustrious Foundress; for King James and King Charles, our most munificent Benefactors, and for our present Sovereign, our Most Gracious Conservator and Benefactor; for the Right Honourable the Lord Mayor, together with his brethren, the Aldermen, and the whole assembly of the citizens of Dublin, and all our other benefactors, through whose Bounty we are here maintained for the exercise of Piety and the increase of Learning,” etc.[15]

Let thy merciful Ears, O Lord, be open to the Prayers of thy Humble Servants, and grant that thy Holy Spirit may direct and guide us in all our ways, and be more especially assistant to us in the Holy Actions of this day, in enabling us with grateful Hearts and zealous Endeavors to celebrate this Pious Commemoration, and to answer to our Studies and Improvements all the great and useful ends of our Munificent Founders and Benefactors. We render thee humble Praise and Thanks, O Lord, for the Most Serene Princess Queen Elizabeth, our Illustrious Foundress; for King James the First, our most Liberal Benefactor; King Charles the First and Second, our Gratious and Munificent Conservators; for the protection and bounty we have received from their present Majesties, our most Indulgent Patrons and Restorers; for the Favour of our present Governours, the Right Honorable the Lords-Justices; for the Lord Mayor and Goverment of this City, our Generous Benefactors; for the Nobility, Clergy, and Gentry of this Kingdom; thrô whose Bounty and Charitable Generosity we are here Educated and Established; for the Improvement of Piety and Religion, the advancement of Learning, and to supply the growing necessities of Church and State; beseeching thee to bless them all, their Posterity, Successors, Relations, and Dependants, with both Temporal and Eternal blessings, and to give us Grace to live worthy of these thy Mercies, and that as we grow in Years so we may grow in Wisdom, and Knowledg, and Vertue, and all that is praiseworthy thrô Jesus Christ our Lord

Such being the true history of the foundation of Trinity College, as the mother of an University, to be a Corporation with a common seal, it was natural that upon that seal the Corporation should assume a device implying its connection with Dublin. Accordingly, though there is no formal record of the granting of arms to the College, the present arms, showing it to be a place of learning, Royal and Irish, add the Castle of the Seal of the Corporation of Dublin. Dr. Stubbs quotes (note, p. 320) a description of it in Latin elegiacs, of which the arx ignita—towers fired proper—are a modification of the Dublin arms,[16] which I have found on illuminated rolls of the age of Charles I. preserved by the City. But this description is undated, and although he ascribes it to the early years of the 17th century, it will be hard to prove it older than the seal extant in clear impressions, which bears the date 1612 above the shield, and upon it the towers, not fired, but domed and flagged. This date may even imply that the arms were then granted, and that it is the original form.[17] The[11] recurrence of the domes and flags upon some of our earliest plate (dated 1666) gives additional authority for this feature, nor have we any distinct or dated evidence for the fired towers, adopted in the 17th century by the City also, earlier than the time of Charles II., when they are given in a Heraldic MS. preserved in the Bermingham Tower. I have digressed into this antiquarian matter in proof of my opening assertion that the details of the foundation are often obscure, while the main facts are perfectly clear.

Let us now turn from our new-founded College to cast a glance at the City of Dublin of that day, as it is described to us by Elizabethan eye-witnesses, and as we can gather its features from the early records of the City and the College. Mr. Gilbert has quoted from Stanihurst’s account of Dublin, published in 1577, a curious picture of the wealth and hospitality displayed by the several Mayors and great citizens of his acquaintance; and that the Mayoralty was indeed a heavy tax upon the citizen who held it, appears from the numerous applications of Mayors, recorded in the City registers, for assistance, and the frequent voting of subsidies of £100, though care is taken to warn the citizens that this is to establish no precedent. The City is described as very pleasant to live in, placed in an exceptionally beautiful valley, with sea, rivers, and mountains around. Wealthy and civilised as it was, it would have been much more so, but that the port was open, and the river full of shoals, and that by the management of the citizen merchants a great mart of foreign traders, which used to assemble outside the gates and undersell them, had been abolished. The somewhat highly-coloured picture drawn by Stanihurst is severely criticised by Barnabe Rich,[18] who gives a very different account, telling us that the architecture was mean, and the whole City one mass of taverns, wherein was retailed at an enormous price, ale, which was brewed by the richer citizens’ wives. The moral character of the retailers is described as infamous. This liquor traffic, and the extortion of the bakers, are, to Rich, the main features in Dublin. The Corporation records show orders concerning the keeping of the pavements, the preserving of the purity of the water-supply, which came from Tallaght, and the cleansing of the streets from filth and refuse thrown out of the houses. These orders alternate with regulations to control the beggars and the swine which swarmed in the streets. Furthermore, says Stanihurst—“There are so manie other extraordinarie beggars that dailie swarme there, so charitablie succored, as that they make the whole civitie in effect their hospitall.” There was a special officer, the City beadle, entitled “master” or “warden” of the beggars, and “custos” or “overseer” of the swine, whose duty it was to banish strange beggars from the City, and keep the swine from running about the streets.[19]

In one of the orders relating to this subject, dated the 4th Friday after 25th December, 1601, we find the following:—“Wher[as] peticion is exhibitid by the commons, complaineing that the auncient lawes made, debarring of swyne coming in or goeing in the streetes of this[13] cittie, is not put in execution, by reyson whearof great danger groweth therby, as well for infection, as also the poore infantes lieing under stales and in the streetes subject to swyne, being a cattell much given to ravening, as well of creatures as of other thinges, and alsoe the cittie and government therof hardlie spoken of by the State, wherin they requirid a reformacion: it is therfore orderid and establyshid, by the aucthoritie of this assemblie, that yf eny sowe, hogge, or pigge shalbe found or sene, ether by daie or nyght, in the streetes within the cittie walles, it shalbe lawfull for everye man to kill the same sowe, hogge, or pigge, and after to dispose the same at his or their disposition, without making recompence to such as owneth the same.”

Thus this present characteristic of the country parts of Ireland then infected the capital. I have quoted the text of the order for reasons which will presently appear.

The City walls, with their many towers, and protected by a fosse, enclosed but a small area of what we consider Old Dublin. S. Patrick’s and its Liberty, under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop, who lived in the old Palace (S. Sepulchre’s) beside that Cathedral, was still outside the walls, which excluded even most of Patrick Street, and was apparently defended by ramparts of its own. Thomas Street was still a suburb, and lined with thatched houses, for we find an order (1610) that henceforth, owing to the danger of fire[20] in the suburbs, in S. Thomas Street, S. Francis Street, in Oxmantown, or in S. Patrick Street, “noe house which shall from hensforth be built shalbe covered with thach, but either with slate, tyle, shingle, or boord, upon paine of x.li. current money of England.” We may therefore imagine these suburbs as somewhat similar to those of Galway in the present day, where long streets of thatched cabins lead up to the town. Such I take to have been the row of houses outside Dame’s Gate, the eastern gate of the city, which is marked on the map of 1610. They only occupy the north side of the way, and for a short distance. There had long been a public way to Hogging or Hoggen Green, one of the three commons of the City, and the condition of this exit from Dublin may be inferred from an order made in 1571, which the reader will find below.[21]

The reader will not object to have some more details about the state of this College[14] Green, now the very heart of the City, in the days when the College was founded. In 1576 the great garden and gate of the deserted Monastery of All Hallowes was ordered to be allotted for the reception of the infected, and the outer gate of All Hallowes to be repaired and locked. In the next year (and again in 1603), it is ordered that none but citizens shall pasture their cattle on this and the other greens. It is ordered in 1585 that no unringed swine shall be allowed to feed upon the Green, being noisome and hurtful, and “coming on the strand greatly hinder thincrease of the fyshe;” the tenant of All Hallowes, one Peppard, shall impound or kill them, and allow no flax to be put into the ditches, “for avoyding the hurte to thincrease of fyshe.” In the same year the use and keeping of the Green is leased for seven years to Mr. Nicholas Fitzsymons, to the end the walking places may be kept clean, and no swyne or forren cattle allowed to injure them. In 1602 Sir George Carye is granted a part of the Green to build a Hospital, and presently Dr. Challoner and others are granted another to build a Bridewell; and this is marked on the map of 1610, near the site of the present S. Andrew’s Church.[22]

This is our evidence concerning the ground between the College and the City—an interval which might well make the founders speak of the former as juxta Dublin. It was a place unoccupied between the present Castle and College gates, with the exception of a row of cottages, probably thatched, forming a short row at the west end and north side of Dame Street, and under that name; opposite to this was the ruined church of S. Andrew. On the Green were pigs and cattle grazing; refuse of various kinds was cast out in front of the houses of Dame Street, despite the Corporation order; a little stream crossed this space close to the present College gate, and the only two buildings close at hand, when the student looked out of his window or over the wall, were a hospital for the infected, by the river, and a bridewell on his way to the City.

Further off, the view was interesting enough. The walled City, with its gates, crowned the hill of Christ Church, and the four towers of the Castle were plainly visible. A gate, over a fosse, led into the City, where first of all there lay on the left hand the Castle entrance, with the ghastly heads of great rebels still exposed on high poles. Here the Lord Deputy and his men-at-arms kept their state, and hither the loyal gentry from the country came to express their devotion and obtain favours from the Crown. In the far distance to the south lay the Dublin and Wicklow mountains, not as they now are, a[15] delightful excursion for the student on his holiday, but the home of those wild Irish whose raids up to the City walls were commemorated by the feast of Black Monday at Cullenswood, whither the citizens went well guarded, and caroused, to assert themselves against the natives who had once surprised and massacred 500 of them close to that wood. The river, the sea, and the Hill of Howth, held by the Baron of Howth in his Castle, closed the view to the east. The upland slopes to the north were near no wild country, and therefore Oxmantown and S. Mary’s Abbey were already settled on the other bank of the river.

We must remember also, as regards the civilisation of Dublin, that though the streets swarmed not only with beggars and swine, but with rude strangers from the far country, yet the wealthy citizens were not only rich and hospitable, but advanced enough to send their sons to Cambridge. This is proved by the Usshers and Challoners, and we may be sure these were not solitary cases. As regards education, there are free schools and grammar schools constantly mentioned in the records of the time. It is well known that one Fullerton, a very competent Scotchman, was sent over by James VI. of Scotland to promote that King’s interests, and that he had a Hamilton for his assistant, who afterwards got great grants of land for himself, as Lord Clandeboye, and also obtained for the College those Crown rents which resulted in producing its great wealth. Fullerton, a learned man, was ultimately placed in the King’s household. Both were early nominated lay Fellows of the College. These were people of education who understood how to teach.

But most probably the great want in Dublin was the want of books. There must have been a very widespread complaint of this, when it occurred to the army which had defeated the Spaniards at Kinsale (in 1601) to give a large sum from their spoil for books to endow the new College.[23] This sent the famous James Ussher to search for books in England, and laid the foundation for that splendid collection of which the Archbishop’s own books formed the next great increase, obtained by the new military donation of Cromwell’s soldiers in 1654. There is probably no other so great library in the world endowed by the repeated liberality of soldiers. Still we hear that, even after the founding of the collection, James Ussher thought it necessary to go every third year to England, and to spend in reading a month at Oxford, a month at Cambridge, and a month in London, for the purpose of adding to that mass of his learning which most of us would think already excessive. Yet it is a pity[16] that smaller men, in more recent days, did not follow his example, and so save the College from that provincialism with which it was infected even in our own recollection.

Let us now turn to the internal history of the College. The great crises in the first century of its existence were the Rebellion under Charles I. and the civil war under James II., ending with the Settlements by which Charles II. and William III. secured the future greatness of the Institution. This brief sketch cannot enter into details, especially into the tedious internal quarrels of the Provost and Fellows; we are only concerned with the general character of the place, its religion, its morals, and its intellectual tendencies. Upon all these questions we have hitherto rather been put off with details than with a philosophical survey of what the College accomplished.

It has been well insisted on by Mr. Heron, the Roman Catholic historian of Trinity College, that the Charter of Elizabeth is neither exclusive nor bigoted as regards creed. Religion, civility, and learning are the objects to be promoted, and it is notorious that the great Queen’s policy, as regards the first, was to insist upon outward conformity with the State religion without further inquisition. A considerable number of the Corporation which endowed the new College were Roman Catholics, and we know that even the Usshers had near relations of that creed. There was no insistence that the Fellows should take orders—we know that Provost Temple, and Fullerton and Hamilton, among the earliest Fellows, were laymen,—and though in very early days the degree of Doctor conferred was apparently always that in Theology, the Charter provides for all the Faculties, and it was soon felt that Theology and the training of clergy were becoming too exclusively the work of the place. The constant advices from Chancellors and from other advisers to give special advantages to the natives, and the repeated attempts to teach the Irish language, and through its medium to educate the Irish, show plainly that they understood Elizabeth’s foundation as intended for the whole country, and more especially for those of doubtful loyalty in their creed, who were tempted to go abroad for their education.

“A certain illustrious Baron,” says Father Fitz-Simons, writing in 1603, “whose lady, my principal benefactress, sent his son to Trinity College. Notwithstanding my obligations to them for my support, I, with the utmost freedom, earnestness, and severity, informed and taught them, that it was a most impious thing, and a detestable scandal, to expose their child to such education. The boy was taken away at once, and so were others, after that good example. The College authorities are greatly enraged at this, as they had never before attracted any [Roman Catholic] pupil of respectability, and do not now hope to get any for[17] the future. Hence I must be prepared for all the persecution which their impiety and hatred can bring down upon me.”[24]

On the other hand, the early Provosts imported from Cambridge, Travers, Alvey, Temple, were men who were baulked in their English promotion by their acknowledged Puritanism—a school created or promoted by that desperate bigot Cartwright, who preached the most violent Genevan doctrines from his Chair of Divinity in Cambridge. But these men, who certainly were second to none in the intolerance of their principles, were themselves in danger of persecution from the Episcopal party in England. Complaints were urged against Temple for neglecting to wear a surplice in Chapel—a great stumbling-block in those days; the Puritanism of the College was openly assailed, so that its Governors were rather occupied in defending themselves than in attacking the creed of others. Any sect which is in danger of persecution is compelled so far to advocate toleration; we may be sure that the Irish Fellows who lived among Catholics in a Catholic nation curbed any excessive zeal on the part of the Puritan Provosts; and so we find that they did not scruple to admit natives whom they suspected, or even knew, to be Papists. Moreover, the Fellows and their Provost were very busy in constitution-mongering. They had the power by Charter of making and altering statutes—a source of perpetual dispute; and, besides, the Plantation of Ulster by James I. in 1610 gave them their first large estates, which were secured to them by the influence of Fullerton and Hamilton, already mentioned as Scottish agents of the King. Provost Temple spent most of his time either in framing statutes or in quarrelling about leases with his Fellows.

A review of the various documents still extant concerning these quarrels shows that the first of the lay Provosts was not inferior in importance to his two successors in the eighteenth century, and that in his day all the main problems which have since agitated the Corporation were raised and discussed.

In the first place we may name the distinction between University and College, one often attempted by theorists, and which may any day become of serious importance if a new College were founded under the University, but one which has practically had no influence in the history of Trinity College. We even find such hybrid titles as Fellow of the University, and Professor of the College, used by people who ought to have known the impropriety.[25] Temple, with the[18] consent of his Fellows, sought to obtain a separate Charter for a University, and drew up, for this and the College, Statutes which Dr. Stubbs has quoted.

The second point in Temple’s policy was an innovation which took root, and transformed the whole history of the College. It was the distinction of Senior and junior Fellows, not merely into separate classes as regards salary and duties, but into Governors and subjects. It was rightly felt that, after some years’ constant lecturing, the Fellows who still adhered to the College should have leisure for their studies, and for literary work, as well as a better income, in reward of their services. But when Temple made a College Statute that the Seniors should govern not only the scholars and ordinary students, but also the Junior Fellows and Probationers (which last correspond somewhat to our present Non-Tutor Fellows), he soon came into conflict with the Charter, which gave many privileges—the election, for example, of the Provost—to all the Fellows without distinction; and on this question arose a great dispute immediately on Temple’s death, there being actually two Provosts elected—one (Mede) by the Seniors, the other (R. Ussher) by the Juniors. Bedell was only elected by a compromise between the two parties, with distinct protests on the part of the Juniors.[26] The Caroline Statutes finally decided the matter, and gave the whole control to the Seniors.

Whether this great change, introduced by Temple, and certainly promoted by Ussher, has been a benefit or an injury to the College, is a question not easy to answer. There is no doubt that a small body, such as the Governing Board of Provost and Senior Fellows, is far more likely to carry out a consistent policy, and even to decide promptly, where discussion and divergence of opinion among a larger number cause delay and paralyse action. But, on the other hand, the concentration of power into the hands of a small and irremovable body sets temptations before its members to look after their own interests unduly, and cumulate upon themselves offices and emoluments to the damage of the Corporation.

The reservation of a large number of offices to the Senior Fellows, and the consequent appointment, occasionally, of incompetent persons to discharge important duties, were the necessary result of such an arrangement, and might be of great injury to the Corporation. It might even result in the trafficking in offices, or in acts of distinct injustice towards the other members of the Corporation, which could not have been committed had the acts of[19] the Governing Body been subject to the public criticism and control of the whole body of Fellows.

On the other hand, as some working Committee must be selected to administer the affairs of the College, nothing was more obvious to Temple or to Ussher than that those who had been Fellows for eight or ten years should be preferred to those who had just entered the Corporation. In a body, however, of celibates, with many good livings and other promotions around them, it never occurred to the framers of the Statute that new circumstances would arise which made a Fellowship practically a life office, and thus placed the government in the hands of a group of men, of whom many were disabled by age, and, moreover, distracted by family cares. We should not stare with more wonder at a Vice-Provost of 40, than would Ussher have stared at a Junior Fellow of 40 years’ standing. Had such things been even dimly foreseen, it would have been easy to avoid the danger of accumulating emolument and office upon incompetent persons by making the Governing Body elective from the whole Corporation.

The third question which arose in Provost Temple’s day was the proper leasing of the College estates. The tendency to take present profit at the expense of our successors, or to postpone the interests of the abstract Corporation to the claims of private friendship, is nowhere more conspicuous than in the document Dr. Stubbs has printed (p. 32), in which the Provost, and two Senior Fellows, the greatest names at the foundation, and the most attached friends of the College, James Ussher and Luke Challoner, actually consent to lease for ever all the Ulster estates to Sir James Hamilton, their old personal friend and colleague, who had helped the College to obtain these lands from the King. Had the earnest endeavours of these two excellent Senior Fellows been carried out, the College would not have owned nearly so many hundreds, as it now owns thousands, in Ulster. This calamity was only averted by the active interference of the Junior Fellows, who obtained an order from the State forbidding the Board to give perpetual leases. Nevertheless, so long as the Senior Fellows divided the renewal fines, there was constant danger of the rents of the College being cut down, and the incomes of the lessors being increased: it redounds to the credit of this “Venetian Council” that, after such vast opportunities of plundering public property, only some few cases of breach of public trust can be asserted against them. One of the most manifest attempts has been just noticed. Another was partly carried through by Temple. He obtained a lease, and appointed his son Seneschal of the Manor of Slutmulrooney—a delightful title, but also a solid estate, which he evidently coveted for a family property.[27]

We turn with satisfaction from such things to the two great names in the College and the Irish Church which mark that period—Bedell and James Ussher.

It was by rare good fortune that the nascent College secured such a student as James Ussher. He must have made a name in any case; yet the world is so apt to judge any system not by the average outcome, but by the best and worst, that one such name was at that moment of the last importance. He was the first great home growth, and, though he refused the Provostship, he was so closely connected with the College as Fellow, Lecturer in Divinity, as Vice-Provost and as Vice-Chancellor, that no one has ever thought of denying him and his fame to the College. His works and character will be discussed in another chapter. What I am concerned with is his attitude in the great ecclesiastical quarrels of the day. It was no easy course to steer the Church of Ireland between the “Scylla of Puritanism” and the “Charybdis of Popery.” Ussher well knew that both were dangerous enemies. In his youth, owing to his daily contact with Roman Catholic relatives, with Jesuit controversialists, with the temporising policy of King James, who offered further stages of toleration in return for subsidies of money from the Irish Catholics, he was strong against the danger on that side, and protested with prophetic wisdom that such concessions would lead to rebellion and ruin in Ireland. In his old age, when living constantly, either from his public importance or his persecutions, in England, when witnessing and suffering from the outrages of the English Revolution, he said in a conversation with Evelyn, “that the Church would be destroyed by sectaries who would in all likelihood bring in Popery.” The personal complexion of his religion, his constant preaching, his great liberality and good feeling towards pious Dissenting ministers, show that he was a strong Protestant, and he always showed the strongest apprehension of the ambitious policy of the Romish priesthood, which he feared as a pressing danger; but, nevertheless, he was so loyal a Churchman, that he was content to overlook many abuses in the system which he administered.

It was this temper, so common in the Anglo-Irish Protestant, which separates him in his policy from his eminent and amiable contemporary, Bishop Bedell. But the latter was a stranger brought over from England to be Provost, who, with all the generosity and all the kindliness of his noble nature, set himself to instruct the native Irish, and to work out the regeneration of these barbarians by teaching them religion through the Irish language. So sterling and single-hearted was the Bishop, that even the excited rebels of 1641, amid their rapine and massacre, spared and respected the excellent old man, and at his death honoured him with a great public funeral. But it is plain from Primate Ussher’s dealings with him that this policy of persuading the natives was not to the Primate’s taste. Ussher probably believed that there[21] were serious dangers in the policy of reclaiming the natives through kindness, and their priests through persuasion; and if the historians note it as curious that, of all those who ruled the College, those by far the most anxious to promote Irish studies were two Englishmen,[28] Bedell and Marsh, it will be replied by many in Ireland, that this contrast between the views of the English stranger, and of the English settler who knows the country, is still perpetuated.

Such, then, was the attitude of the early rulers of the College, and such their controversies. All of them that were not complete Puritans felt what Provost Chappel says in his autobiographical (iambic) poem—Ruunt agmine facto in me profana turba Roma Genevaque. But from the very commencement the College was Puritanical enough to save it from Ecclesiasticism. There is therefore nothing strange in the habit of making lay Fellows read short sermons (commonplaces) in the Chapel as part of their duty—a practice only abandoned within the memory of our seniors in this century.[29]

We turn to the few and meagre traditions concerning the moral condition and conduct of the students. It must be remembered that they came up at a very early age—12 to 14 years old are often mentioned—and were only supposed to be partly educated when they took their B.A. degree. There were special exercises and lectures for three years more, and only with the M.A. were they properly qualified. We may, indeed, be sure that the post-graduate studies were far the more important for the serious section of the lads. For they came up very raw and ignorant; they even had a special schoolmaster to teach them the elements of Latin and Greek, and of course the books they could command were both few and imperfect as educational helps. I do not think that from the first the College was at all abandoned to the poor or inferior classes. The very earliest lists of names contain those of the most respectable citizens; there were often favourite pupils of a Provost, or other Don, who came from England, brought over with their teacher. Very soon the Irish nobility began to send their sons. The Court of Wards, established by King James I. in 1617, ordered that the minors of important families in Ireland should be maintained and educated in English habits, and in Trinity College, Dublin; and the first instance of this kind is that of Farrall O’Gara, heir to Moy Gara, County Sligo, who was to remain at the College from his 12th to his 18th year. By this means many youths of quality, or at least of important family, were enrolled among the students. The Earl of Cork sent[22] two sons in 1630; the famous Strafford two in 1637; and we find Radcliffes, Wandesfords, and other aristocratic names. What strikes us in the face of this is the extreme economy—or rather the apparently very small prices mentioned in the various early accounts printed by Dr. Stubbs from the Bursar’s books.[30]

This economy, however, only applies to the scholars supported by the House, especially the natives, who had various privileges. Fellow-Commoners, and Nobles, such as Strafford’s sons, were probably allowed various indulgences. It is interesting to notice that from the first a certain proportion of lads came, as they now do, from the counties of England (especially Cheshire) nearest to Dublin. On the other hand, while natives are carefully distinguished from lads born in Ireland, I cannot find what test was applied to determine a “native.” Even in 1613, 20 out of the 65 students are so denominated. The majority of the natives, says Archbishop Marsh two generations later, had been born of English parents, and were mostly of the meaner sort, but by having learned to speak Irish with their Irish nurses, or fosterers, had acquired some knowledge of the vernacular. But they could not read or write it. The names quoted by Bedell in 1628 suggest that this account of the parentage is true. Conway, Baker, Davis, and Burton are admonished for being absent from Irish prayers. These are not Irish names. It is also added by Marsh that most of these native scholars, bred in the College, turned Papists in James II.’s reign. This proves that they had Irish mothers, and would have afforded James Ussher a strong confirmation for his policy as against Bedell’s.

This society of students was then, as it has ever since been, very various in race, social position, and parentage, and to this not a little of its great intellectual activity may be traced. It should also be added here that one of the strongest natural reasons for the great prominence[23] of the Anglo-Irish, and the extraordinary distinctions they have attained in every great development of the British Empire, is that the English settlers of Elizabethan and Jacobean days were the boldest adventurers, the young men (often of good family) of the greatest energy and courage, to be found among the youth of England. They came to incur great risks, to brave many dangers, but to attain great rewards. The rapidity of promotion among the ecclesiastics, for example, is quite astonishing: Bishops at 30, Archbishops and Chancellors at 40, are not uncommon. And if these daring adventurers were often unscrupulous, at all events they and their quick-witted Irish wives produced a most uncommon offspring.

We do not find that any hereditary turbulence showed itself in disorders among the students. The early quarrels recorded are all among the Fellows, and upon constitutional questions. The main complaints against the boys were very harmless freaks, if we except the constant apprehensions of the Deans concerning ale or tippling houses in the city, which were assumed to be haunts of vice. Stealing apples and cherries from the surrounding orchards was a common offence, coupled, moreover, with climbing over the wall of the College. It shows Ussher’s hand when we find this local feature formally noted in the Caroline Statutes. A few of Bedell’s entries are the following:—

1628. July 16 and 18.—At the examinations each forme was censured, and it was agreed that none shall ascend out of one forme to another, however absent, till he be examined.

August 18.—Examination for Scholars—Apposers, Mr. Thomas and Mr. Fitzgerald.

August 21.—The Bachelors to be hearers of the Hebrew Lecture, unless they that were able to proceed in that tongue by their private industry, and those are to help in the collation of the MSS. of the New Testament in Greek. Twelve Testaments were given by Sir William Ussher for the Irish.

August 24.—A meeting about the accounts. Warning given of town haunting and swearing. The Deans requested to appoint secret monitors for them.

September 13.—The Dean may punish for going in cloaks by the consent of the Provost and greater part. Mr. Temple’s letters to the Provost and Fellows answered—his cause of absence to study in Oxford not gravis much less gravissima.

September 22.—The course for banishing boys, not students, by occasion of Mr. Lowther’s boy striking Johnson consented to, viz. that fire and water, bread and beer and meat be denied them by the butler and cook, under pain of 12d. toties quoties.

September 23.—Deane and Wilson mulcted a month’s Commons for their insolent behaviour, assaulting and striking the butler, which was presently changed into sitting at the lower end of the Scholars’ table for a month, and subjecting them to the rod.

The order for placing the Fellow Commoners by themselves in the Chapel for having more room begins. Service books bought and bound for the natives.

October.—Election of Burgesses for Parliament. The Provost and Mr. Donellan, upon better advice, the Provost resigning, Mr. Fitzgerald was chosen.

December 28.—The Lord Primate dined in the College at the Hall, and the same Dr. James Ware presented the petition for renewing the lands of Kilmacrenny. Jo. Wittar admonished for playing at cards.

January 28.—Tho. Walworth refused to read Chapter, and enjoined to make a confession of his fault upon his knees in the Hall—which he disacknowledging—he had deserved expulsion.

July 23, 1629.—Sir Walworth said to have sold his study to haunt the town. Somers, Deane, and Elliott appointed to sit bare for going out of the Hall before grace, and not performing it, made to stand by the pulpit.

April 2.—The proclamation against Priests and Jesuits came forth.

April 5.—Easter day, at which the forms were used for conveniency about the Communion Table.

April 11.—Mr. Travers, for omitting his Common place the second time appointed, punished 13s. Mr. Tho. for omitting prayers reading, 5s.

May 12.—The Sophisters proposed supper to the Bachelors: prevented by sending for them and forbidding them to attempt it.

July 11.—The Fellow Commoners complain of Mr. Price for forbidding them to play at bowls in the Orchard; they were blamed, and it was shown that by Statute they could not play there.

July 29.—Six natives, Dominus Kerdiffe, Ds. Conway, Ds. Baker, Ds. Davis, Ds. Kerdiffe, jun., and Burton, admonished for being often absent from Irish Prayers.

August 19.—The natives to lose their weekly allowance if they are absent from prayers on the Lord’s Day.

August 29.—Sir Springham said to keep a hawk. Rawley, for drunkenness and knocking Strank’s head against the seat of the Chapel, to have no further maintenance from the house.

Booth, for taking a pig of Sir Samuel Smith’s, and that openly in the day time before many, and causing it to be dressed in town, inviting Mr. Rollon and Sir Conway (who knew not of it) was condemned to be whipped openly in the Hall, and to pay for the pig.

August 6.—Communion. Sermon upon Psalm 71. 16. The Articles of the Church of Ireland read.[31]

The entries of the 29th August (1629) are peculiarly interesting, but have hitherto not been understood in their local connection. There is an entry in Mr. Gilbert’s Assembly Roll (ii., p. 82) awarding a citizen £8 for a goshawk he had purchased for the city, which hawk had died. This is a very large sum—perhaps equal to £70 now, and out of all proportion to the salaries and the prices of necessaries in the College. To keep a hawk was, therefore, somewhat like keeping an expensive hunter now, and a proof of great extravagance. As regards the story of the pig, it was nothing more than a comic carrying out of an order (above, p. 13) frequently issued by the Corporation, whom Booth took at their word. It seems, therefore, that either such proclamations[25] were a sham, or that they only referred to the right of citizens to interfere with the roving swine.

The courts seem to have been in grass, as there is an early item for mowing, and 1s. 4d. for an old scythe. A vegetable garden was kept for the use of the College on the site of the present Botany Bay Square, and the further ground belonging to the precincts is called a firr park, which seems to mean a field of furze, much used for fuel in those days. There was neither room nor permission for the games and sports so vital to modern College life. The old and strict notion of a College life, still preserved in some Roman Catholic Colleges abroad, excluded all recreation as waste of time. The Caroline Statutes formally forbid playing or even loitering in the courts or gardens of the College. Nor was this any isolated severity. In the detailed horarium laid down for a proposed College at Ripon, to be founded by James I.’s Queen (Anne of Denmark) at this very time, every half-hour in the day is fully occupied with study, lectures, or prayers.[32] There was considerable license, however, allowed at Christmas, and it was perhaps from the old Monastery of All Hallowes that the fashion was transmitted of acting plays at that season in the College. The performance seems to have been undertaken by the several years or classes. In 1630 it was ordered that the play should be acted, but not in the College. The Lord Deputy constrained the unwilling Provost Ussher to permit it. Even in the Caroline Statutes, remains of this Christmas license appear in the permission to play cards—at other times strictly forbidden—in the Hall on that day. Every 17th March (S. Patrick’s Day), the town population came in crowds from the city to S. Patrick’s well at the southern limit of the College (now Nassau Street, opposite Dawson Street), there to test the miraculous powers of that holy well, which at that moment of the year worked strange cures of diseases. We can imagine the[26] furze bushes or trees around this well all hung with tattered rags, as may still be seen at wells of similar pretensions in the wild parts of Ireland. If the enclosed S. Stephen’s Green was still remarkable in the last century “for the incredible number of snipes” that frequented it, so the College Park must have contained them in abundance. But it was reserved for our grandfathers to boast that they had shot a snipe in the College precincts.[33]

The intellectual condition of the average 16th century student is even harder to ascertain, and I have sought in vain for adequate materials. It does, indeed, appear that the Irish New Testament and Prayer Book had been printed. Sir H. Sidney’s Irish Articles of Religion were brought out in 1566. John Ussher had promoted Kearney’s Irish Alphabet and Catechism, produced in Dublin from type supplied by the Queen in 1571.[34] William Ussher had produced the New Testament in Francke’s printing, 1602. This printer is probably the man mentioned as the “King’s printer” in 1615 (for proclamations?). But though there is extant a proposed arrangement with the very printer of one of these books (Kearney) to live and work in the College,[35] there is no trace of his having done any real service. Even the Statutes were in MS., copied out by the hand of the Provost or Vice-Provost. The annals of Dublin show, I believe, none but isolated printing till about 1627;[36] it was in 1641, both in Kilkenny and Waterford, as well as in Dublin, that printing began to be used for disseminating political views. But the earliest students must have found it very difficult to obtain books, and there is no trace that any printing press started up to meet this urgent want. I am now speaking only of text-books for students, by which I mean such small and handy editions as the Latin Isagoge of Porphyry, printed at Paris in 1535, of which copies are often found in Dublin, as the work was diligently taught in the 17th century course. Dudley Loftus’ Logic and Introduction, printed in 1657 (Dublin), seem to me the earliest books likely to have been used as text-books in Trinity College. Strange to say, there is no copy of either in our College Library. But[27] the official teaching was strictly oral, and the students were merely required to write out in theses or reproduce in disputations what their tutors had told them. The College course, as laid down by Laud (or Ussher?) in the Caroline Statutes, is plainly not a course in books, but in subjects. Not a single text-book, unless it be the Isagoge of Porphyry, is specified, and this rather for the lecturer than the students. Whatever practical relaxations the course then laid down may have undergone, it was chiefly in the post-graduate studies; for the officers of the College had no power to alter or emend the programme of Laud till the year 1760, when a special King’s Letter gave them authority to do so. This accounts for the great quantity of lecturing which went on, each tutor giving three hours every day, not to speak of the efforts of the College Schoolmaster, who undertook those that were raw in Latin and Greek. Archbishop Loftus, indeed, in his parting address to the College (Armagh Library MS.), exhorts the new Provost (Travers)—“See that the younger sort be well catechised, and that you prescribe to the rest a catalogue of approved books to be read by them as foundations of learning, both human and divine.” But this alludes to post-graduate studies, for which the Library was then established,[37] and not to the daily studies of the undergraduates. Logic was the chief subject, the system of Ramus being brought into fashion by the Cambridge Puritans, and especially by Provost Temple, who had written a book on the subject. Chappel was also a famous Ramist logician. Very little mathematics was taught, but, on the other hand, Hebrew was regarded as of equal importance with Greek; and in every subject we find the student’s knowledge tested, not by reproduction of his reading, but by disputations, which showed that he had so far grasped a subject that he could attack an adversary or defend himself when attacked.

[1] The writer of the first four chapters here acknowledges the generous help received from J. R. Garstin, Esq., B.D., and the Rev. William Reynell, B.D., both in supplying him with facts and in correcting his proofs. This portion of the book was undertaken by him suddenly, in default of a specialist to perform it. Hence the large number of extracts inserted, in which the facts must rest upon the authority of the authors quoted, as there was no time to verify them. Of the three extant histories of the University, those of Taylor and of Dr. Stubbs are very valuable in citing many original documents, the former chiefly Parliamentary, the latter from the archives of the College. Heron’s work was written for a special purpose, which he pleads throughout, after the manner of his profession.

[2] “That before the Reformation it [the Royal College of Dublin] was common to all the natives of this country, ... and the ablest scholars of the nation preferred to be professors and teachers therein, without any distinction of orders, congregations, or politic bodies other than that of true merit,” etc. Cf. Dublin Magazine for August, 1762. This golden age of Irish University education may well be relegated to the other golden ages of mythology.

[3] I quote the text (which has lately been printed), of which I owe my knowledge to the kindness of Mrs. Reeves, who lent me the late Bishop of Down’s MS. copy:—“Nolui enim Magnatum placitis me accomodare qui summo conatu, immo cæco impetu et consutis dolis, operam dederunt ut prope Civitatem Lymericensem vel Armachanam fundaretur, quasi piaculum non fuisset periculis belli incendii turbacionis et ruinæ exponere Academiam noviter fundatam, ... nulla alia forsan ratione quam uberioris proprii quæstus gratia. Quem et objeci viro eorundem præcipuo prænobili arteque militari conspicuo fascibusque tunc potito, non obstante quod nimis subitaneæ iræ impetu sæpius se monstraverat pronum ad furorem et verbera; is enim non semel se rapi sinebat æstuantis animi violentia in proclivitatem vim hujuscemodi inferendi aliis; notum enim est ... quam strenuum et fortem virum, sed tunc podagra laborantem pedibusque captum percussit ipse iræ infirmitate perculsus, etc. Non defui igitur mihi vel Academiæ obstando tanto viro,” etc. In other words, he claims to have incurred great danger of being thrashed by Perrott for opposing him! And he retorts the very charge brought against himself, of having pecuniary interests in the background.

[4] I cite from Mr. Wright’s citation of Thomas Smith’s life of James Ussher, Ussher Memorials, p. 44.

[5] Cf. E. P. Shirley’s Original Letters, &c., London, 1851, for these and other details.

[6] Cf. Gilbert, op. cit. vol. ii., for Usshers, pp. 17, 22, 65, etc.; for Challoners, pp. 45, 64, 88, 259, etc.

[7] Op. cit. pp. 64, 88.

[8] He was uncle to the famous James Ussher, now commonly known as Archbishop Ussher. Henry Ussher, however, was also Archbishop of Armagh. He was educated both at Cambridge and at Oxford, as well as abroad.

[9] On application to Cambridge, I am informed, by the kindness of the Registrar and of Mr. W. A. Wright of Trinity College, that Luke Challoner (spelt Chalenor) matriculated as a pensioner October 13, 1582, took B.A. degree in 1585, and M.A. in 1589. He was never a Fellow, or even a Scholar, of Trinity College, Cambridge, and obtained his D.D. at one of the earliest Commencements in Dublin, probably in 160 0 1 .

[10] Stubbs’ History of the University of Dublin, Appendix iii., p. 354. None of the histories note that there were foreign Colleges founded by Irish priests for the Irish at this very time in Salamanca (opened 1592), Lisbon (1593), Douai (1594). Thus there was an active policy to be counteracted by Elizabeth, and these proposed foundations were probably set before her by Henry Ussher as a pressing danger. Some account of the Constitution of the Salamanca seminary is given in Hogan’s Hibernia Ignatiana, Appendix, p. 238. The students were to be exclusively of Irish parentage.

[11] Who these well-disposed persons were is beyond doubt. The Queen mentions Ussher in the Warrant; the College mentions Challoner on his tomb—

“Conditur hoc tumulo Chaloneri triste cadaver

Cujus ope et precibus conditur ista domus.”

James Ussher, in recommending a subsequent Provost (Robert Ussher), says—“He is the son of that father at whose instance, charge, and trust the Charter of the first foundation was obtained from Queen Elizabeth” (Works, i., 103). On the epitaph of Provost Seele we read—

“Tecta Chalonerus pia condidit; obruta Seelus

Instauravit.”

In the MS. at Armagh, written in praise of Loftus, and reporting his speeches, we have the following (p. 228):—“Among many prudent inducements suitable to polity and reason which moved the Queen to establish this University and College at All Hallowes, the humble peticion of Henry Ussher, Archdeacon of Dublin, in the name of the Citty of Dublin, faithfully and most zealously solicited by Dr. Luke Challoner, and as powerfully recommended and promoted by Adam Loftus, etc., was not held the least of efficacye as to extrinsicall impressions with the Queen in that behalf.” Here, then, in a panegyric of Loftus, Archbishop and Chancellor, his name is postponed to those of the two local men and the City of Dublin. This fact speaks for itself. I quote these various documents to correct the current impression that Loftus was the real founder.

[12] Gilbert: Ancient Records of Dublin, ii., p. 240

[13] The Book of Benefactions (first printed in the College Calendar of 1858) gives the date of the actual grant as July 21, in the 34th year of Elizabeth.

[14] Stubbs, op. cit. pp. 10, 11.

[15] From a Book of Common Prayer printed in Dublin, 1721, where it appears among the “Prayers for the use of Trinity College, near Dublin.” “What authority there was for these prayers has not been ascertained. They certainly were not an integral portion of the book as adopted by the Irish Convocation, and in the Dublin-printed edition of 1700 they first appear interpolated, in the T.C.D. Library copy, between two of the Acts of Parliament which were then printed in some issues of the Church of Ireland Prayer-book.”—J.R.G. The prayer printed at the beginning of Provost Ashe’s secular sermon, of which an illustration is given on p. 10, was possibly the model: it was printed in 169 3 4 .

[16] The old Dublin seal has men-at-arms shooting with cross-bows from the tops of the towers, which are five stories high. The cause of the change is, I believe, known, though I have not learned it.

[17] It occurs to me, as a solution of this difficulty, that in 1612 Temple and his Fellows were occupied in preparing a Charter and Statutes for the University, as distinguished from the College. This scheme, when almost complete, was adjourned sine die. But if the original seal contained any allusion to Trinity College as an University, which is very possible, then this seal, dated 1612, is the first seal of the College as such, and there may have been another seal prepared for the University, which disappeared with the failure of the scheme.

[18] Description of Dublin (1610).

[19] Cf. Gilbert’s Ancient Records, ii., 16, 63, 99, 142, 377, and on Stanihurst, p. 541.

[20] The other constant cause of fire mentioned is the keeping of ricks of furze and of faggots close to the houses.

[21] “It is agreed that no person or persons frome hensforthe shall place any dounge on the pavement betwyxt the Dames Gate and the Hoggen Greane; and that they shall suffer no dounge to remayne upon the saide pavement against ther houses or gardinges in the said streete above xxiv owres, and that they shall make clean before their gardinges of all ramaylie, dounge, or outher fylthe with all convenyent speade; and to place the same and all outher dounge that shalbe caryed to the saide greane, in the greate hole by Allhallowes, and not elsewheare upon the same greane, upon payne of vis viiid, halfe to the spier and finder, and thother halfe to the cyttie worckes.”—Gilbert, ii., p. 66.

[22] On the map of 1610, facsimiled on p. 7 (from Mr. Gilbert), the Hospital and the Bridewell, on the west and north of the College respectively, are interchanged in names or in numbers. The descriptions in the records of each, op. cit. pp. 390, 420, will prove this mistake in the map.

[23] The amount is usually stated at £1,800. Dr. Stubbs reduces it to £700. Even so, it was a very large sum. Dr. Stubbs also proves that there were some books in the College Library before 1600, op. cit. p. 170.

[24] Fitz-Simons’ Life and Letters, translated and edited by E. Hogan, S.J., p. 56. “Non sine Collegiatorum ingenti fremitu, qui hactenus nullum alicujus æstimationis ad se pellicere potuerunt,” evidently refers to Roman Catholic boys, if we are to defend the learned Jesuit’s statement as one of fact.

[25] Thus a window in the College Chapel, set up as a memorial of Bishop Berkeley, calls him a Fellow of this University. I need not point out how this blunder has been exalted into an official title by the Examining Body called the Royal University of Ireland, which has no Professors for its University, and no College for its Fellows.

[26] Cf. op. cit. p. 395. The decision of the Visitors had been for the latter, but reversed by the Chancellor (Archbishop Abbot), whose letter shows that he had not apprehended the important distinction between Statute and Charter; the Statutes, made by the College, being powerless to abrogate what the Charter had ordained.

[27] It is now known as Rosslea Manor, in Fermanagh, and pays the College about £2,000 a-year.

[28] Robert Ussher was the only Irish Provost who adopted the same policy. But he was clearly a sentimental person, as appears from his cousin the Primate’s judgment, that he was quite too soft to manage the College, and also from the Latin letter to the Primate still extant (Ussher Memorials, p. 275), a very florid and tasteless piece of rhetoric.

[29] It also existed at Oxford. Wesley preached in this way as a layman.—J. R. G.