Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, MARCH 16, 1897. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 907. | two dollars a year. |

Some boys, like some men, have greatness thrust upon them. Bruce Marvel became one of these boys one day to his own great surprise.

Bruce was a good shot with either rifle or shot-gun; he could pitch, catch, or strike a ball as well as any other boy of his age, and he could handle a horse better than some men who travel with circuses. Still, he had spent most of his life in an inland village where the largest body of water was a brook about six feet wide. It stands to reason, therefore, as boys are very like men in longing most for what is[Pg 474] farthest from their reach, that Bruce's consuming desire, in the line of sport, was for a sail-boat and for water in which to sail it. He studied pictures of sailing-craft, which he found in a pictorial dictionary, until he could redraw any of them from memory; he learned the names of all the sails of a full-rigged ship, and he delighted in sea stories of all kinds, while he longed for the day in which he could see broad water and such boats as were moved by wind, and when he could sit in a boat and manage the sails and rudder.

Fortune finally seemed to favor him, for in his fifteenth year he was invited to spend a month at the sea-shore with an aunt of his mother's. As the aunt's family contained no men, it had no boats, so Bruce was sadly disappointed. But he was not of the kind that gives up when disappointment comes; he spent most of his waking hours in walking the beach of the little bay about which the town was built, looking at the boats, and scraping acquaintance with boys whose fathers owned boats; he kept up his spirits by hoping that in the course of time some one would invite him out sailing, and perhaps to take part in the management of a craft of some sort, Bruce cared not what, so that it had sails.

But sailing was anything but sport to the boys whom Bruce came to know, for most of these boys were fishermen's sons, to whom sailing meant hard, every-day work, of which they did not care to do more than was absolutely necessary for business purposes.

Yet Bruce learned some things about sailing, thanks to sharp eyes. He observed the fishing-boats and other small craft until he learned that almost anything that sailed would "go over" very far without capsizing. He thought he learned a lot about steering, too, although it puzzled him greatly that different vessels would sail in different directions while the wind blew from but one point of the compass. He determined to clear this mystery for himself, for nothing comes harder to a spirited boy than the displaying of ignorance by asking questions about matters which every one else seems to understand.

One day he climbed into a fishing-boat which a receding tide had left lying upon the sand. The little three-cornered sail in front of the mast, which Bruce knew was called a jib, had been left loosely flapping, as if to dry, while the owner sought refreshment and company near by. As many another man has done before him, the owner remained longer than he had intended; meanwhile the tide came up until it floated the vessel, so Bruce had rare fun at "trimming in" the jib-sheets, first on one side and then on the other, and in seeing the boat strain at her anchor, which was a big stone with a long rope attached.

Suddenly the wind began to come from the shore in hard puffs. Bruce trimmed in the jib very close, upon which the boat tugged furiously at her anchor; but she did the same when the sail was hauled close on the other side, so the make-believe sailor eased the sheet until the wind was directly abaft. Still the boat continued to strain; the anchor rope was old, so finally the friction caused by rubbing against the rail made the strands part suddenly; then the boat started for sea "on the wings of the wind," as Bruce afterward said.

The boy sprang to the rudder. At last he was really sailing! It was through no fault of his, either, as he carefully explained to himself, for how could he have known of the rottenness of that rope? He had some misgivings, for he was sure that he did not know how to turn the boat and sail back again against the wind; still, he was resolved to have a little fun before asking assistance from some passing boat. He had been in the village and along the shore long enough to know that the offing was usually alive with fisher-craft coming in or going out, and he had frequently seen boats towed by others; so he had no doubt that he would be helped back safely to the beach again.

Within a few moments he learned several facts about sailing; one was that by "easing" sheets freely while sailing under a jib alone, the sail will dispose itself at almost a right angle to the wind, so there need be but little work at the rudder. As to the larger sail, he did not trouble his mind about it, for not only was he in doubt as to how to use it, but his craft was going quite fast enough with such canvas as she was already carrying.

The farther he got from shore the stronger the wind seemed to blow—a condition which did not impress him favorably, for he was soon out of the bay and upon the ocean, and although the water was not rough, the sea appeared to be very large, and the few boats in sight were far from him; and when he tried to steer toward some of them, his own boat behaved quite provokingly, as any boat will when asked to change her course much while the only sail she carries is a jib.

Still, the experience as a whole was great fun, and whenever Bruce felt a little scare creeping through him, he rallied himself by singing a selection from "A Life on the Ocean Wave," beginning,

We shoot through the ocean foam

Like an ocean bird set free.

But the wind continued to increase in strength, and to come in hard puffs, which Bruce had heard were dangerous. How was the boy to get back to shore? He began to recall some sea stories, which did not now seem as interesting as when he first read them—stories of boys who had drifted out to sea and never been heard of afterward. It does not require many such memories to make a wind-driven boy fearful of what is to come; a man would feel quite as uncomfortable in similar circumstances—being driven out to sea, in the latter part of the afternoon, with no sign of rescue in sight, and he in a boat which he did not know how to manage.

After some hard sailing Bruce determined to let down the jib if it would consent to fall, turn the boat's head toward shore with an oar that lay in the bottom, and then paddle back to the bay; fortunately he had learned paddling on the brook in his native village. Whether he could force the boat against such a wind he did not know, but he had strong arms; besides, the tide certainly would help him, for it was setting shoreward, otherwise it would not have lifted the boat from the beach an hour or two before. He succeeded in getting down the jib, although it hung loosely and caught much wind. He found paddling, in the circumstances, much harder than propelling a narrow raft on the still water of a brook; although the sea was not exactly rough, the deck was a very unsteady platform for his feet, and the wind caused the craft to wildly change direction from time to time; once the rail bore so heavily upon the oar that Bruce had to choose between letting go or going overboard, so of course he let go, and a moment later the boat was again hurrying seaward.

"This," said Bruce, as he went gloomily aft and took the tiller, "must be what the stories mean when they tell about scudding under bare poles. There can't be any doubt about it, although I greatly wish there could."

Up to this time the wind had been freshening Bruce's appetite, but now the boy would have promised to fast a week for the certainty of getting ashore. The sun was steadily declining; not a sail was in sight on the course over which he was drifting. Steamers and other vessels occasionally went up and down the shore, in plain sight of the bay, but what chance was there of his sighting one of them before dark; and what pitiful stories he had read of shipwrecked men whose signals had been unseen or disregarded.

Suddenly he saw, a mile or two out to sea, and in the course he was sailing, something which appeared to be a row-boat containing men who were waving hats and handkerchiefs.

"Hurrah!" shouted Bruce. "They want to get back without rowing. Perhaps some of them will know how to manage this contrary craft. I hope they will have sense enough to row towards me, for if I steer a bit wrong nothing can keep me from running out to sea and missing them."

He quickly got the jib up, so as to sail faster; he knew he could get it down again should he find himself in danger of passing the other boat. Under canvas, Bruce got over the water rapidly, but to his surprise and consternation the[Pg 475] men did not attempt to row toward him. Suddenly he exclaimed.

"That isn't a row-boat! It is bigger, and of a different shape. It's a sail-boat, and on its side, and the men are sitting on the edge of the hull.' They're wrecked! I wonder why their boat doesn't go over entirely? Oh, I see!—the mast and sail are lying on the water, and keeping it on its edge. Oh, if I were a good sailor! See the poor fellows signalling to me! I suppose they're wild with excitement and fear, although they can't be more so than I."

In the next few moments Bruce steered very carefully; he also did some earnest thinking. How should he stop his own boat entirely when he came abreast of the wreck? He knew of no way but that of letting down the jib, which had not worked very successfully when already tried, for the mast and hull had caught the wind with alarming success. Should he shout to the men, explain his ignorance, and ask what he should do? If one of the men would swim out to him when he neared them, and take charge of his boat, Bruce did not doubt that all would go well; so he assured himself that no false pride should prevent him confessing that he knew nothing about sailing, should he fail to lay his craft alongside of the wreck.

Meanwhile his boat kept exactly the proper course. The shipwrecked men began to shout, but the wind was against them, so Bruce could not distinguish a word. He hoped that they were hailing him as their deliverer; he also hoped that they would be able to deliver him from the worst trouble in which he had ever found himself. The shouting continued, but Bruce was now too near to pay attention to anything but the tiller, which had seemed to become a thing of life and intelligence. When he got within about a hundred feet of the wreck he heard:

"Isn't it time to drop your jib? And throw us a line, if you please."

Bruce quickly let go the jib-halyard, but in his excitement he forgot to ease the sheet, so the sail declined to fall; the wind kept it in place. A few seconds later the young amateur was thrown from his feet by the shock of his boat striking and breaking the mast of the capsized boat. The force of the collision tumbled the three shipwrecked men into the water; but they quickly scrambled out, and one of them shouted,

"Hurrah! Now throw us a line, before we drift apart."

Bruce responded by tossing a coil of the main-sheet, and begging the man who caught it to keep tight hold of it.

"Count upon us for that, young man," was the reply. "We know our last chance when we see it, and we aren't going to let go of it."

In a moment the line was made fast to a cleat just under the rail of the wrecked boat, while Bruce said,

"I'm very sorry that I broke your mast, but my jib wouldn't come down."

"Don't mention it, young man, don't mention it! 'Twas the best thing you could have done for us, next to coming out to our rescue, for otherwise we never could have got our boat righted. Of course we couldn't get the hull on its bottom again without unshipping the mast—a job we've been attempting ever since we went over. Although we've cut all the stays, the mast sticks in its step as if it was fastened there or at the deck. We'd have cut the mast ourselves if we'd had anything to do it with, and risked getting back with the oars, which we've kept lashed."

"Let's clear away now," said another. "It's going to take a lot of time to right the hull, and get the water out, and get the wreckage aboard, so we'll have as little as possible to pay for. We'll have to get our young friend to tow us in, if he will, and 'twill be slow work, beating all the way."

"Let me help you all I can," Bruce replied, "for you will have to help me get my own boat back to the bay."

"I should think so," said one of the men, as he hauled Bruce's boat close and sprang into it. "'Twas right enough to run out under a jib, but of course you can't get back that way, and no one man can handle main-sheet and tiller in a breeze like this. Now, boys, I'll get up sail on our friend's boat, and see if we can't get some help from it in righting our own. It will be troublesome work, for our ballast shifted—the wrong way, of course—as we went over."

"Suppose," Bruce suggested quickly, "that two of you come aboard, if you're used to working together in a boat? I don't know much about righting capsized hulls."

"Eh? Well, probably not. You every-day sailors on the coast here aren't stupid enough to let a boat go over, as we amateurs did when a hard puff came to-day. We pass for pretty good sailors, too, in our yacht club at home. Here, Grayden, come aboard. I'll take the tiller, you take the main-sheet, and if our young friend will 'tend jib—"

"Good!" interrupted Bruce, while a great sense of relief came to him. He felt well acquainted with that jib.

The mainsail, in which there already was a reef, was hoisted, the main-sheet of the wrecked boat was taken aboard as a hawser, and after much shouting and tacking and jerking the capsized hull was righted. Then sail was dropped on Bruce's boat, the wreck was hauled alongside, and the three men bailed out the water with their hats, adjusted the ballast, and dragged the wreckage aboard and stored it. One man was left on the hull to steer, a tow-line was put out, sail was made once more on Bruce's boat, and the party started for the bay. When fairly on the proper course the man who had seemed to take the lead in every thing said to Bruce:

"My young friend, we've been working and worrying so hard that I'm afraid we've forgotten our manners, but I want to assure you that we're the most grateful men in this part of the world to-night, unless three others have been rescued from drowning. Eh, boys?"

"Yes, indeed," replied one. "I think, too, for a chap as young as our friend to dash out to sea in such a breeze to save some men whom he never saw before was a remarkably plucky deed. I'm proud to know you, my friend, and I'd like to do something great to prove it."

"So would I," said another.

"You're very kind," Bruce replied, "and you may begin at once, if you like. You would be doing a great thing for me if you would teach me something about sailing."

"Wha—a—a—at?" drawled one, while the other opened his eyes very wide. "Why—you came out in splendid style."

"I'm glad of it, but, really, I couldn't help it; the wind did it all. I never before was out in a boat with a sail on it; I wouldn't have been out this time if the anchor rope hadn't broken while I sat in the boat playing with the jib."

"Whew! And through that accident you've saved our lives!"

"And you've saved mine. Still, won't you please try and teach me something about sailing—right now, while we're at it?"

Two teachers took the boy in hand at once; they made many short tacks, with Bruce at the tiller, to show how to "put about"; they explained how the force of a sudden puff could be lessened by quickly heading a little toward the wind, taught him much more about the management of the jib than he had yet learned for himself, and had him observe the different ways in which the mainsail was treated on differing courses. The lessons continued until they reached the bay, where a new anchor rope was purchased for the rescuing craft, whose owner, also, had to be reasoned with and otherwise pacified.

The next day two of the party returned to the city from which they had come for a day's fishing, but one remained, hired a smaller boat, and spent half a week afloat with Bruce, doing all in his power to make a confident yet cautious sailor of the boy. In the mean time there came out from the city some newspapers, in each of which was a marked article telling how a brave youth named Bruce Marvel had, at great peril to himself, saved three men from death by drowning. There also came to Bruce a little gold watch, suitably inscribed; and when the boy finally returned to his home, the newspapers and the watch made him the most noted person in his county, and his honest admission that he really knew next to nothing about sailing boats when he ran out to sea increased his fame immensely.

he recent death of Mr. Charles Dickens, the eldest son of the great author, reminds a schoolfellow of the former, who enjoyed for many years the friendship of the family, of a few circumstances connected with the author of the Pickwick Papers that, never having found their way to paper, may not be without interest at this moment.

It was due probably to Dickens's great regard for the actor Macready that he selected Dr. King's preparatory school for his son. Macready, who lived not far from King's, and who had heard of his great success as a teacher of the classics, informed Dickens of his intention to send his two boys to the school, and Dickens at once decided to place Charlie, as his son was always called, at the same institution.

King's was situated near the famous Lords cricket-ground on Maida Hill. When Douglas Jerrold heard of this he was anxious to know what made her ill, and trusted that Charlie would be all right.

What Dickens replied "deponent saith not," but at a later date he remarked that his boy was in pretty royal company.

It was here that the schoolfellow and his fortunate companions first set eyes on Charles Dickens. Charlie, quite unconscious of the flutter that he would create in the breasts of his schoolmates, quietly informed them that his father would visit the school on a certain day. Until that auspicious time the Pickwick Papers became more bethumbed than ever. The writer was on the tiptoe of expectation and not a little nervous. What liberties are taken with the names of the great! "Dickens is coming!" If Jones the lawyer were expected, or Pills the apothecary, it would have been: "Mr. Jones is coming; Mr. Pills will visit his son."

When Dickens did come it was with a rush. He lovingly embraced his boy, shook the hands of the fortunate lads who were introduced as Charlie's particular chums, slipped some money into his son's hand, and was off, without the almost inevitable allusion to the pons asinorum or the hic, haec, hoc, those bêtes noire of a schoolboy's existence.

But it was while he was talking to Dr. King that an opportunity was given to study Dickens from a boy's point of view. He was then considerably under forty, but looked—to the boy, remember—a comparatively old man. What was young in him were his hair and eyes. There were not many wrinkles visible, but lines of thought and care marked features that in repose were deceiving in their sternness. As to his dress, the writer has since thought that, while it might have been quite untidy and loud for a butterman's best, it suited Dickens's rapid motions and easy gait. It would be hard to imagine Dickens in prim attire. Such apparel would have been out of place.

It was while summering at Broadstairs, a quiet watering-place on the Kentish coast, that the writer had perhaps the best opportunity to study Dickens's characteristics—the most notable of which most certainly was his love for children. Apparently adoring his own, he still had room in his great heart for other people's darlings. Had it been more generally known that for several seasons Dickens made Broadstairs his abiding-place, that pretty little sea-side resort would have been crowded with visitors. As it was, several of his intimate friends, among them the artists Stone and Egg, made Broadstairs their summer home.

Those twenty-mile rambles, so frequently alluded to, would alone have made Dickens interesting to younger people, who were continually arranging to meet the author and his frequent companion, Miss Hogarth, on the cliffs or sands between Pegwalt Bay and Margate.

Once Dickens came to the rescue of some children who had been overtaken by the tide. Miss Hogarth and the writer were of the party. Dickens summoned donkey-boys from Margate and sent the youngsters home at a gallop. They arrived just as the tide was washing the white cliffs.

Only once in several years did the writer hear Charles Dickens's voice in angry tones. This was the occasion, and it was indelibly impressed on his memory:

"Mamie" (Miss Mary Dickens) and "Katie" (Catharine, named after her mother, whom Dickens always addressed as Kate) were very pretty and interesting girls; indeed, they were the little belles of Broadstairs. They frequently had juvenile tea parties at "Bleak House," as Dickens's Broadstairs home was called. It was situated on a high bluff, and stood alone—a very picturesque but mournful and deserted-looking building, as peculiar in its style as the author's house in Devonshire Terrace, London. Dickens's library had a seaward and an inland view. He was then writing Dombey and Son, and he had told Miss Hogarth that he must not be disturbed. But notwithstanding this injunction, the tea party, rather formidable in numbers, tired of cake and bread and butter, scoured the house and turned it into a Bedlam, gentle Mamie, however, protesting.

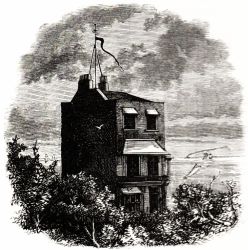

BLEAK HOUSE, BROADSTAIRS.

BLEAK HOUSE, BROADSTAIRS.At a moment when Dickens was evidently very much engrossed, the children, with a wild rush, broke in on his quietude. The writer, wittingly, or perhaps impelled by force of numbers, found himself within a few feet of the desk where Dickens was writing, and was very much alarmed as Dickens looked angrily on the crowd. But he loved children too well to be angry with them long. Rising from his seat, the frown melting into the smile that always endeared him to young people, he spread his arms and simply shooed us from the room, like the geese that we were, and bade us seek Miss Hogarth, who never seemed to tire of entertaining her niece's guests. But on this occasion the abashed marauders, deeming "discretion" to be "the better part of valor," crept into the garden, where Charlie was engaged in the innocent though perhaps dangerous pastime of gathering some very dubious-looking plums from a tree that had seen better days. Miss Hogarth, having doubtless been interviewed by Dickens, led the young people to understand, later in the day, that strangers would not be admitted to Bleak House until further notice, thus practically breaking up the tea parties. We subsequently learned that Dickens had frequently been disturbed, and[Pg 477] it was necessary that silence should reign for a season.

Very little has been written, if indeed anything, of this interesting summer home of the noted author—Bleak House. It was surrounded by high and gloomy brick walls that gave the old place a dreary and forbidding appearance. Its very quaintness moved Dickens to make it his temporary abiding-place. It may have been interesting, but it seemed to the good people of Broadstairs, as they looked on the most exposed spot in all the little place, that only courageous hearts could live at Bleak House. And during a frightful storm, that sunk fishing-smacks and damaged the coast, devastating the esplanade and destroying not a few farm-houses, the frightened residents at morning's dawn looked with pale faces in the direction of Bleak House, almost expecting to find it in ruins. But in spite of its exposed position, the house bravely withstood the gale, although chimney-pots and trees were blown down. The family was naturally alarmed, and betook themselves to apartments adjoining the library on the esplanade. The library and assembly-rooms were the public resort of Broadstairs's quality. But Dickens was rarely if ever seen at the gatherings.

Dickens remarked a few days later to the writer's father that the gale had been an alarming and thrilling experience.

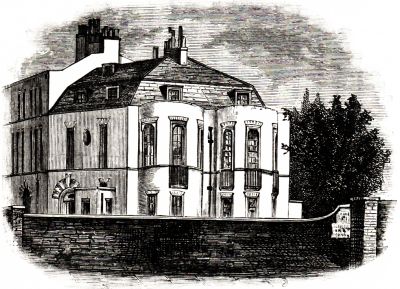

DICKENS'S HOUSE IN DEVONSHIRE TERRACE, LONDON.

DICKENS'S HOUSE IN DEVONSHIRE TERRACE, LONDON.Soon after the meeting at Dr. King's school Charlie's schoolfellow visited the family in Devonshire Terrace, just off the New Road. David Copperfield was then the book of the hour, and because it had been suggested that the author had his own boyhood in mind while writing the novel, Dickens was more of a lion than ever to the juvenile mind. Charlie devoured the pages of the book with avidity. Indeed, all the novelist's children were charmingly appreciative of their father's writings—a flattering incentive to Dickens, no doubt.

At the moment of this visit, his own little darlings, as well as some others, were crawling all over him, reminding one of Gulliver in the toils. But he at once turned to the somewhat bashful visitor, and, in renewing the acquaintance, with delightful tact made the schoolboy feel that he was not de trop.

It was at the juvenile birthday parties that Dickens seemed in all his glory. At the supper table, in helping some little miss to "trifle," he would assure her with all possible gravity that it was no trifle at all. When the writer, urged to make a little speech on the occasion of Charlie's birthday, came to a full stop at the words "I am sure," Dickens at once came to his assistance, and enabled him to retire from the platform, however ungracefully, with the remark, among others, "Always be sure, my dear boy, and you'll get along all right."

At the little theatrical entertainments Dickens was the alpha and the omega of the proceedings. He was sometimes author, adapter, condenser, musical director, manager, prompter, and even stage carpenter. He overflowed with energy.

Dickens, doubtless remembering his own acute sensitiveness as a child, could not wittingly wound a child's feelings. He made fun with, not of us. No party ever came off at Dickens's without "Sir Roger de Coverley" being introduced. Dickens shouted with laughter as some novice got badly mixed up in "all hands down the middle." Off he darted after the lost sheep—generally an awkward boy—and turned his blushes to smiles by saying, "What a dancer this boy will make when he's tackled a little more roast beef!" or, "Isn't Tommy a nice young man for a small party?"

There was nothing of the pedagogue about him. No vulgar attempt to pose as the brilliant "Boz." He was simply a big boy, and he came down the ladder of his fame to meet his fellows on their ordinary platform—to be one of them in their own simple way for a time.

had found a little box, that had just room enough for a bunk and a narrow cupboard, at the foot of the forecastle ladder, and this I took possession of, as, of course, it would not do for me to mess or bunk in with the crew. There was a fine ten-knot breeze blowing when I was awakened the next morning, and the little cutter was dipping into the waves gracefully like a Mother Cary's chicken. Every one was in high spirits. All idea of my being a Jonah had faded from the minds of the crew. Yet I was filled with a huge disappointment. A bitter, miserable sensation had firm hold of me. I saw what an injudicious and, mayhap, an unkind thing I had done, and regretted that I had not been more strenuous in my efforts to keep Mr. Middleton from carrying out his intentions of leaving the Cæsar; but I believe that if I should have urged strongly against it, the cruise of the Bat would have ended there and then.

At eight bells in the morning watch I saw Mr. Middleton come on deck. I noted that he held his wig on with one hand as he approached. I lifted my hat and bowed politely.

"A word with you," began the old gentleman. "It is evident that you never had any intention of touching at Dublin."

"That, sir," I returned, "is the truth; I never had. Would you suppose it possible for an American crew to sail[Pg 478] into a hostile harbor in a captured vessel and get out again?"

"You played the joke well on the Englishmen," he said.

"Yes; but they were Englishmen," I answered. "The Irish might be quicker-witted."

I knew that he was an Irishman, for he had a genteel touch of the brogue.

"Look here, my young sir," he rejoined; "I am a wealthy man, and my word is as good as a written and sworn-to bond. If you will land me on the coast of Ireland, anywhere, I will give you a thousand pounds."

"No money could tempt me," I replied, "to place the freedom of my crew in jeopardy; but this I have determined; if I meet a vessel bound for Europe, and can do so without risk, I intend to place you and your granddaughter Mistress Tanner on board of her. More than this it is beyond my power to do."

"You just spoke Miss Tanner's name," said the old man, looking at me fiercely; "and when we came on board, your forwardness in speaking was most noticeable. I pray you, do you claim acquaintance?"

"Sir," I returned, "it is as the lady says."

"She says you are a stranger to her," answered the old man, grimly.

"So be it," I replied, and turned upon my heel.

I did not see anything of Mary that day, but late in the evening she and her grandfather came on deck, and, arm in arm, walked up and down the weather side of the quarter-deck, I giving over to them, and pacing up and down the opposite side of the mainsail; but my heart was big to bursting, and I was tempted again and again to step around the mast, and standing there face to face with the girl that had given me the rose, demand an explanation. Oh, woman! who can account for your strange actions or analyze the motives of your inconsistencies?

As they went below, I happened to be standing so close that my presence could not be ignored, nor could I, without seeming rudeness, avoid speaking.

"I hope you and the young lady are quite comfortable, Mr. Middleton," I said, bowing. "If there is anything in my power I can do to add to your comfort, I pray you to command me."

Purposely I avoided looking at Mary as I spoke, and yet I was conscious that her eyes were full upon my face. She stood a little apart from her grandfather, and her little foot was tapping the deck impatiently. Mr. Middleton acknowledged my salutation, and replied with a certain peevishness that is shared by the very old or the very young.

"The only thing that you can do is to redeem your promise, and set us on some vessel bound for Great Britain," he returned.

"I shall endeavor thus to redeem myself," I said. And then the two went below, leaving me leaning back against the boom with a leaden heart.

We were carrying a great square topsail, and kicking up a great smother forward that showed that we were travelling well. The man at the tiller was humming softly to himself, the crew were lolling forward, when I saw my First Lieutenant approach. I noticed from his expression that he wished to speak to me.

"Well, Mr. Chips," said I, "and what is it?"

"I beg your pardon, sir," he returned, "but hadn't you better take a squint at the sun and see where we are? It's near high noon."

I was in a quandary, for, as I have stated previously, I knew nothing of navigation—that is, the science of it.

"Well, Mr. Chips," I said, "do you suppose I don't know where I am?"

"The sextant is in the cabin, sir. But there is another thing," he added, touching his cap. "Would you mind calling me by my real name?"

"Why, isn't it Chips?" I exclaimed in surprise, not knowing that this was the nickname applied to every carpenter afloat.

"My name is Philemon Cutterwaite," he answered, quietly.

As of course I had no intention to hurt his feelings, I repressed a smile, merely saying, "Very good, Mr. Cutterwaite; I shall endeavor to remember it."

"Thank you, sir," was the reply. "Shall I get the instruments and take the time?"

As he spoke he stepped to the head of the companion-ladder and knocked. I could think of no excuse for the moment for detaining him, and taking my silence for consent, he obeyed the answer from below to enter, and disappeared. But in an instant he came on deck.

"Captain Hurdiss," he said, "the chronometer has stopped. We must have forgotten to wind it, sir—bad fortune!"

"Then there is no sight for to-day," I said, much relieved.

"I suppose not," was the grumbling answer. And then the good fellow went below.

I messed alone, either on deck or in my box of a cabin; and I had just finished my evening meal when one of the crew who had been aloft came down to the forecastle and reported that there was a sail in sight to the westward. When I came on deck I could just make out a faint spot against the sunset sky, but what course the vessel was holding I could not make out even with the aid of a glass. It was dead calm, and the Bat rolled lazily about, fetching up with a jerk of her heavy boom that would send an echolike sound rolling up the great mainsail.

In my absence Mr. Cutterwaite, as I shall call him hereafter, had given some orders, and I saw that some of the crew were making ready to get rolling tackle on her, as a preventive of the danger of carrying anything away by the slapping and romping of the vessel. The sea that was running must have been the aftermath, so to speak, of a heavy blow, for it rolled from the southward, smooth and round, with not a ripple on the crest or a dimple to be seen on the sides of the waves.

The sun was going down behind a streaky line of clouds that crossed the western sky in such a peculiar manner that, as they caught the red sunset color, the whole west resembled nothing so much as a great American flag. Even the stars were there, shining in the blue field. I was standing looking at it in admiration, when I turned suddenly and saw that Mary Tanner had come on deck, and was regarding the sight with wide-open eyes. Probably she had not seen me, but I determined to speak to her, and so came closer.

"It is our flag yonder," I said, pointing.

She gave a little frown, as if I had interrupted some pleasant thought.

"I see it," she answered, turning her head half away; and with this she descended to the cabin again.

Such a starlit night as this was I can never recollect seeing. The calm continued, and as it was warm I brought up a blanket to lie on, and determined to pass the night on deck. As I lay there watching the topmast sway to and fro against the besprinkled heavens, I fell into wondering what was going to become of me—what should I do when I returned to America. I could not imagine; and it seemed to me that it was impossible that Mary Tanner, whom I had grown to think of as the one person in the world who might be interested in my life (ah, the beloved picture of her waiting for me!) was here within sound of my voice; here in my keeping, as it were; and yet affairs were sadly different from what I had hoped or supposed they would be.

I was lying with my head almost on the edge of the hatch combing, when I thought I heard the sound of something like a sigh or a long-drawn breath. I raised myself on my elbow, and there she was standing not three feet from me. I could have placed my hand over hers if I had so chosen.

"Mary," I said, softly. She gave a little gasp and turned.

"Pray do not go until you have heard a few words that I wish to say," I went on, leaning forward. "If my speaking to you is disagreeable, I shall not repeat the offence a second time. Listen! I had not thought to carry you away, but I had hoped some day to find you. In prison I thought of this, and as a free man the hope has been before[Pg 479] my eyes. Now there is nothing left. I have naught to offer you, but some day there may come a time when I can do so." I was urged to speak thus by I know not what. "You think that I am but a common sailor. I am—"

"Oh, pray do not explain further, Monsieur le Marquis," she interrupted. "I suppose that you were going on to speak of your estates and titles."

I started.

"What do you mean?" I said. "What do you know, anyhow?"

"Only what Gaston informed every one in Stonington," she said. "Poor loon! they would have put him in the mad-house. But you were going on to say, you are—"

"A plain American seaman," I returned, "who would give his life to serve you."

I had risen to my feet and stood there looking at her. I thought for a moment that her look had softened as I spoke, but just then Mr. Middleton's voice interrupted us from the cabin.

"Mary, child," he called, "where are you?"

"I am here," she answered, and she jumped below, almost into the frightened old man's arms. I clinched my teeth, and there was no sleep for me that night.

In the early morning hours it clouded a little, and an intermittent breeze blew up from the south. At daybreak we discovered the sail that had been sighted the evening before, about three miles distant, bearing a few points off our weather bow. She was a small ship, and at the first glance at her Mr. Cutterwaite pronounced her English. We changed our course, and at the same moment the vessel did hers also, and when about a mile distant she broke out her flag.

"A Portuguese, by David!" exclaimed Dugan.

"We'd better try the British Jack, sir," suggested the carpenter.

I acquiesced, and soon the Bat's natural colors were flying over us. Instantly down went the Portuguese emblem, and up went that of England. The ship had come up into the wind, and was waiting for us with her maintop-sail aback and her foresheets fluttering. Suddenly I noticed that she had dropped four ports, and through the glass I noticed one of the guns run in and the toss of a sponge handle. Instantly the risk we were running crossed my mind.

"Stand by to cast loose and provide those guns," I said, holding the Bat up a few points so as to lessen our speed. "Arm all hands," I added.

We were a fair bit less than one-third the size of the vessel we were nearing, and I saw that the men cast rather furtive glances at her as they set about obeying orders.

"Men," I said, "we do not intend to fight that vessel. I just wish to speak to her; but be ready."

"If fight we must, why, fight we will," said Dugan, with a grin.

I called down into the cabin.

"Mr. Middleton," I said, "you can get your baggage, sir. I judge we will soon part company."

In ten minutes we were almost within hailing distance, and the old gentleman came on deck, followed immediately by Mary. Her eyes were red, as if she had been weeping. It required all the strength of will I had to keep my lip from quivering as I raised my hat and wished her a polite good-morning. There was a strange wistful glance that I could not fathom that she threw at me, and then she turned her head aside. I had donned the uniform of my unknown namesake, and leaning against the lee shrouds, I raised my voice and hallooed,

"What ship is that?"

"The Lord Lennox, from Quebec to Liverpool. What cutter is that?"

"His Majesty's sloop Bat, from Dublin to Quebec," I answered.

"What do you want of us?" was the inquiry of a short thick-set man in a beaver hat, who had mounted the rail.

"Can you take two passengers back with you to England?" I replied.

The man on the rail turned as if he were speaking to some one behind him, and giving no answer to this, jumped down out of sight.

"Look out for treachery," cried the carpenter, suddenly. And no sooner had he spoken than the forward gun, an 18-pound carronade, roared out, and the shot plumped through our mainsail.

"Below with you," I cried, dodging under the boom, and hastening Mr. Middleton toward the cabin with a push. "Below for your dear life," I cried to Mary as she followed him.

Without orders one of my men had fired the forward 6-pounder into the hull of the ship, and seeing that our only hope was to get so close that they could not depress their guns enough to hit us, I jammed down the tiller, and we shot up close under the vessel's side. Her three other guns were discharged over our heads, and away went our topmast, and the tip of our gaff with the colors on it. So close were we that a burning wad fell on our deck. The other 6-pounder was discharged, and ripped a great hole in the ship but a few feet above the water-line. And now we were in for it! With a slight jar we grazed along the ship's side, and the wounded gaff tangled, in her fore-shrouds.

"There's nothing for it but to board," I cried.

"Boarders away for the spar-deck!" roared Dugan, as he sprang for the chains, followed by all hands in a wild scramble.

Perhaps the cheer that we gave sounded as if there were many more of us. I saw Dugan's pistol flash as he threw his leg over the bulwark overhead. It was answered by a volley, and the poor fellow with a cry fell back into the arms of the next man below him. By almost pushing those ahead of me out of the way, I had managed to be among the foremost. Somebody gave me a leg up from behind, and I shot over the ship's rail on to the forecastle. But I was not alone. To a man the crew of the Bat were with me, and there before us, gathered in the waist, were a score or more of seamen who were scrambling forward to meet our onslaught. They outnumbered us, but we were better armed, and (if I say it, who should not) we were better fighters. I had felt a sharp twinge of pain go through my left shoulder when I had fallen forward, but, getting to my feet, I was soon in the midst of the cutting, shouting, and firing.

Before me stood a thick-set middle-aged man, who hurled a smoking pistol full at me. It grazed my head as I dodged, and my cutlass rang against the weapon he carried in his right hand, an old Scottish claymore with a basket hilt, and a blade some three inches longer than my own. With an oath he made a slash at me that would have brought me to my knees had I not turned it. At the same time, with a sidewise stroke I reached him beneath the armpit, and almost lifted the limb from his body. He fell backward with a howl. I had but noticed this when from the side some one caught me a clip over the head that severed my cocked hat like a pumpkin and sent my senses flying. I stumbled, for I could not for the life of me keep my feet, and down I went.

When I came to I was first conscious of a tremendous throbbing in my temples, and opening my eyes I saw that I was below in the little cabin with the miniatures on the bulkheads. It was but a glimpse of consciousness I had, but in that glimpse I felt a soothing touch laid on my brow. Raising my eyes my heart leaped, for it was Mary bathing my head with a cold wet cloth. The joy of it may have sent me off again, for I remembered no more until I was awakened by the sound of whispering. Looking up, I saw that Cutterwaite and Mr. Middleton were standing alongside.

"Well," I said, faintly, "how fares it?"

"Another prize, Captain Hurdiss, and a good one," said Chips, bending over me. "We took the ship, sir and she's in our wake. We're not five hundred miles off Cape Cod. The wind's fair, and all's a-taunt-o."

Oh, I could have cried for the joy of it, but at this instant[Pg 480] the curtain that had partitioned off the cabin was drawn aside, and I heard a soft voice ask,

"Is he speaking?"

"Mary!" I said, tremulously.

Mr. Middleton and the carpenter stepped to the other side of the curtain, and the one whom I had always dreamed of as waiting for me came near.

There was no pride or anger in her face, and her voice shook as she said, softly,

"Sh-h-h—you must not speak!"

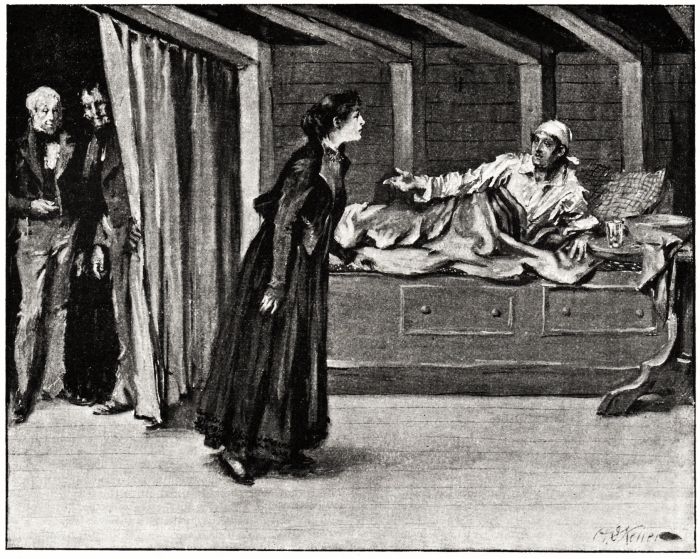

I PUT OUT MY HAND AND SHE TOOK IT.

I PUT OUT MY HAND AND SHE TOOK IT.

I put out my hand. She took it and sank down at the side of the bunk.

"John dear, forgive me," was all she said; and then—and then— Well, what is the use of telling more? Women are strange creatures. But suffice it. I had, of a truth, taken the fairest prize in all the world. How she had won the old gentleman to her way of thinking I do not pretend to tell. I have never asked, nor did he inform me. But some women have a way with them against which there is no gainsaying. Mr. Middleton is a wise man, and this may account for it. But I was not the only one under Mary's care. Dugan and three others were wounded lying in the forecastle; but I am glad to here record, so far as I know, they are at this moment well and hearty. On the fourth day I was on deck when land was sighted. It was my own country that lay off to the westward. I, the happiest man in all the world, was home again.

Thus ended my adventures. Since then I have made many cruises in my own vessels, always knowing that there was waiting for me when I returned the dearest little woman in the world, and were I a nobleman with vast estates I could be no wit happier, nor could I be so happy as I am at this very moment. Of that I am sure.

There is just a half-page left of this old ledger. As my story is done, I can but go over it again; and in looking back, what a strange record I have made here, for I began as a child without a name and without a country, who chose both for himself. I had been a mysterious waif in a Connecticut village, an instructor in small-arms on board a privateer, an English prisoner of war, a French nobleman among the refugees in England, a lieutenant of a fine schooner, and the commander of two vessels, all inside of a week; yes, and had I not been a robber also? For I robbed an English officer and a scare-crow of their clothes, and an old man of his granddaughter. (Of the last I am prouder than I can tell in calm words.) And now I am a prosperous ship-owner, with nothing in this wide world to wish for, except that I were a better scribe. Oh, I might set down that I learned, of course, of the death of my uncle, and found out that Gaston had disappeared with the belongings of Belair; no one knew whither. I was sorry for this, for there was much that I would like to have possessed. As for any other title than that of an American citizen, I care not so much as the snap of my finger; nor would my sons, I am sure, even if they had but to extend their hands to grasp it. They may read in this a great deal that their father has not told them, but it could make no difference, I am sure, in our relations toward one another.

One thing more—I returned all the personal effects found in the Bat's cabin to my namesake who lives in Sussex, England.

Author of "Rick Dale," "The Fur-Seal's Tooth," "Snow-Shoes and Sledges," "The Mate Series," etc.

hile poor Todd was striving to scale the rocky ladder from which he had just fallen, another lad of about his own age had bounded up the steep pathway behind him with the speed and ease of a mountain-goat. He was tall and slender, straight as the lance shaft that he bore in one hand, and finely proportioned. The bronze of his skin and his long hair, black and glossy as the wing of a crow, showed him to be an Indian, though his clear-cut features expressed a lively intelligence, and exhibited none of the hopeless apathy so common to the moderns of his race. His body was naked to the waist, below which it was covered by a pair of fringed buckskin breeches, while his feet were encased in unornamented but serviceable moccasins having soles of goat-skin.

This new-comer was so startled by the unexpected sight of a stranger that he uttered the shout of amazement which had caused Todd to lose his hold. Bitterly regretting his impulsive outcry, and distressed at its result, the young Indian knelt beside the unconscious stranger, and gently lifting his head from the rocks against which it had struck, gazed eagerly into the face of the first white boy he had ever seen.

While he was thus occupied a second figure appeared toiling up the rugged path. It was that of a white man, venerable in aspect, but still sturdy of limb, and clad from head to foot in buckskin. He was a large man, and his massive head was covered with silvery hair, still thick and clustering in curls about his temples. He wore a flowing white beard, and his kindly face was as serenely placid as though the cares of life had touched him but slightly. At the present moment it was flushed from the exertion of climbing, and filled with an anxious curiosity at the astounding sight of a stranger in that place, and one who was at the same time in so sad a plight.

A few words from the Indian lad told all that he knew of what had just happened, and while he spoke the old man examined a slight wound in Todd's head, from which a stream of blood was trickling.

"It does not appear serious," he said at length, "and I believe that with care he will speedily recover. Remain thou here with him while I continue on to the castle and notify mother of what has happened. From her I will obtain a few things that be needful, and will quickly return. Then must we try and carry him down to the hut, for in his present condition I doubt if it would be possible for us to get him up to the castle."

The old man climbed the rock ladder with marvellous agility, and so hastened his movements that in less than five minutes he had returned, bringing a flask of water, some strips of cotton cloth, and a healing salve. The water did so much toward restoring Todd to consciousness that after a little he was able, with help, to regain his feet. Then, with many encouraging words, his new-found friends half carried, half led him back down the steep trail he had so recently climbed, and along the woodland pathway to[Pg 482] the very hut in which he had already spent so much of that eventful day. Here they laid him on the couch of skins, and while the old man looked after his comfort, the Indian lad, taking a flint, steel, and bit of tinder from a recess of the chimney quickly started a fire with which to light the little apartment. Then he disappeared, while his companion tenderly bathed and dressed the wound in Todd's head. He uttered a pitying exclamation on discovering that his patient's hand was also injured, and bound it up with a soothing dressing. While doing these things he talked constantly; but when Todd, still dazed and feeling helplessly weak, made an effort to speak, the other bade him lie perfectly quiet and not attempt to talk until he should be stronger.

"Thy looks are those of one who has suffered much and is even now wellnigh starved," he said, "but very shortly thy hunger shall be relieved, and then will I commend thee to sleep, the restorer."

As he spoke the Indian lad returned, bringing a basket of food. Among its contents was a bowl of broth, which, after it had been warmed at the fire, was given to Todd, who eagerly drained it to the last drop. Then he sank wearily but contentedly back on his couch, and in another minute was fast asleep.

For some time the white man and the young Indian watched him in silence. Then the former said, in a low tone:

"The poor lad has evidently undergone a terrible experience, however it has happened; but now he is doing well, and will pull through beyond a doubt. Whence he came, by what means he was led to this place, and how he discovered the locality of Cliff Castle, are questions that I would gladly ask him, for in all the years that we have dwelt in this valley he is our first visitor. But on no account must he be disturbed until he wakes of his own accord, since complete rest is what he needs above all else."

"Is he in reality a white boy, such as thee has so often described to me?" asked the young Indian. "And will he tarry with us, to be unto me a companion and to thee another son?"

"Truly he is a white lad of about thy own age, and that he will tarry with us is beyond question, for from this place there is but slight chance of escape. For this night I shall leave him in thy charge, while I return to mother, who is doubtless impatient to learn of the happenings of the past hour. Watch closely for his waking, and give him both food and drink if he shall call for them."

In obedience to this command the Indian lad watched his charge all night, studying his face closely in the flickering fire-light, and speculating concerning trim. Occasionally he dropped asleep, but Todd's slightest movement found him wide-awake, for he was too greatly excited over this most wonderful happening of his life for much sleep, even though he had not been charged with a duty. So the night passed, and it was broad daylight when he roused from a slight doze to find the stranger lying with wide-open eyes curiously regarding him.

"Do you speak English?" asked Todd, as the young Indian started to his feet.

"I speak with the tongue of the Professor," answered the lad, shyly, "though I know not if that is what thee means."

"Of course it is, if what you have just said is a sample. At any rate, it is good enough English for you to tell me what place this is, and who you are. I mean, what is your name? Mine is Todd Chalmers. Is there anything to eat that you could let me have, for I'm as hungry as a bear. I suppose you know what that is?"

"Oh, yes!" answered the other, brightly. "Bears are the big rabbits, bigger even than goats or deer, that ate up the children who mocked at Elisha. And here is piki for thee to eat. Also, thee is in the Valley of Peace, and thy servant is named Nanahe, though he is also sometimes called Ishmael, the son of Hagar, who fled into the wilderness."

"Are your parents Quakers?" asked Todd, greatly puzzled by the other's form of speech.

"My father was a Navajo, and my mother was of the Hopi people," answered the other, proudly.

"Oh, I see!" responded Todd, vaguely, though still wondering what sort of a lad this might be, who was so evidently an Indian, and yet spoke English without an accent, though in the manner affected by the Society of Friends. "But I say, old man, you won't mind if I call you 'Nana,' will you? Nanahe is too long for common use, and 'Nan' would sound too much like a girl's name, you know."

"Thee may call me what thee pleases, and I will answer. But has thee really seen girls and known them?" asked the other, eagerly.

"Well, I should rather say I had," laughed Todd. "Why, haven't you?"

"No, but I have wanted to so much. Tell me of them, and what they look like. Do they resemble mother?"

"Not having seen the lady, I can't say; but if she is the Professor's wife, I should think probably not. Girls, you know, are very young, and they look like—why, like nothing in the world but girls. As for describing them, you just can't, because no two of them are the same, and because there is nothing else that I know of to compare them with. But, Nana, how about that breakfast you mentioned some time since? Aren't you afraid we are letting it get cold?"

"It is ready and waiting for thee," said a pleasant voice behind them; and turning quickly, our lad beheld for the first time by daylight the white man who had treated him with so much kindness the evening before.

"Oh, sir," cried Todd, "I am indeed grateful to you for all your kindness to me!"

"And I," replied the old gentleman, "am more than pleased to see thee so evidently restored to health. At the same time I sincerely welcome thee to the Valley of Peace, which, with all it contains, is at thy service. May I introduce myself as Rufus Plant, at one time professor of ethnology in Calvert College, but now and for many years resident of this valley?"

"Calvert College, did you say, sir? Why, that is the college where my brother Mortimer Chalmers is professor of geology, and the one that I am to enter next fall. It seems to me, too, that I have heard your name before. Wasn't there something strange about your dis— I mean, I thought you were killed by Indians."

"Doubtless that was the report, and it might well be credited," replied the Professor. "But tell me, lad, is thy name Chalmers?"

"Yes, sir—Todd Chalmers, of Baltimore."

"Can it be that thee is a relative of my old friend Carey Chalmers?"

"He was my father."

"The Lord be praised for all His mercies!" exclaimed the other. "Why, lad, if thee was a messenger from Heaven thy presence could not be more welcome to an old man cut off these many years from intercourse with his fellows. But thee must be sorely in need of refreshment, and it would be wrong to keep thee longer from her who waits anxiously to welcome thee. Therefore let us hasten to the castle, if indeed thee is strong enough for so arduous a climb."

Todd quickly proved that he was now fully equal to the task that he had so nearly accomplished the evening before, and a few minutes later, filled with an eager curiosity, he stood with his new friends on a broad shelf of rock a hundred feet above the valley. It was bordered along its outer edge by a low parapet, and was partially overhung by the cliff that still rose above it. At its inner end was a veritable house of stone, having a door and windows, just outside of which stood one of the dearest of old ladies, clad in Quaker costume.

The boy knew at a glance that she who welcomed him must be the one whom his new acquaintances spoke of so lovingly as "mother"; but more than ever did he wonder at the strangeness of her surroundings, and long for an explanation of the many things that were puzzling him. A thousand questions were at his tongue's end; but he could[Pg 483] not ask them then, for the dear old lady at once led the way into the house, saying:

"Not another moment shall thee be kept from thy breakfast, Todd Chalmers; for starvation is one of the things not permitted in Cliff Castle, and hunger is written on thy face."

Never had Todd entered so queer an abode, nor one so filled with curious objects, as when he passed the doorway of that little dwelling. Its low roof was not more than two feet above his head, and its interior walls of white clay were covered with rude drawings in color that strongly suggested the work of ancient Egyptians. The stone floor was covered with rugs of goat and deer skins; several articles of rude furniture, besides blocks of jasper and agate used as seats, were conveniently placed, while great earthen-ware jars, quaint in shape and beautifully decorated in colors, stood on all sides. In one corner was a rude fireplace, which was evidently used only to furnish warmth, as Todd had already noticed another, provided with appliances for cooking, on the outer platform.

Best of all, in our hungry lad's estimation, was a table covered with a snowy cloth and laden with food. Nearly all its furnishing—including bowls, platters, jugs, and small dishes—was of earthen-ware quaintly devised and ornamented. There were also several steel knives and forks, half a dozen silver spoons, three white china cups, and as many saucers.

Served on these queer dishes was a breakfast of broiled chicken, oatmeal, corn-bread, and another bread made from grass-seeds, eggs, and stewed peaches, besides small white cheeses, and a jug of goat's milk, all of which combined to make a meal that seemed to Todd better than any he had ever before tasted. It made him pity himself to recall how, only the day before, he had been very nearly starved actually within sight and reach of all this abundance.

When his hunger was at length satisfied, the boy related his adventures of the past few days, describing his wanderings on the desert, his efforts to reach the blue peaks that ever beckoned him forward, his finding of the valley, his perplexity at discerning signs of human occupancy but no inhabitants, his joy at seeing the smoke from Cliff Castle, his fruitless attempt to reach the place from which it ascended, and his doubts as to the kind of reception he might meet from its occupants.

To all this the lad's hearers listened with deepest interest, frequently interrupting him with questions and exclamations. When he had finished he turned to the Professor, saying:

"Now, sir, that you have learned how I happen to be in this place, will you not tell me of your own experience in reaching it, and your reason for remaining here all these years?"

"Gladly will I gratify thy most natural curiosity," replied the old man, "but I must ask thee to wait until evening; for the narrative is of such length that it cannot be told until our affairs are ordered for the day. Therefore, let us first return thanks to our Heavenly Father for His abounding mercies, and then attend to the duties awaiting us."

With this the old man led the way to the outer platform, to which Nanahe fetched a small Bible, that was the only book the Indian lad had ever seen, and from which he read aloud, without hesitation, the exquisite Twenty-third Psalm. While he read, Todd gazed over the underlying valley, and wondered that its every feature should appear so familiar to him. Suddenly he recalled the mirage that three days before had first turned his steps in this direction, and knew that the picture then presented was an image of the one upon which he now looked.

After the simple service was ended the Professor and Nanahe descended into the valley, carrying with them the fowls that had been brought to the castle for safety during their two days' absence. The old lady busied herself with domestic duties, and Todd found himself at liberty to explore the quaint little house, which, his hostess informed him, was only one of many, long since abandoned by their builders, that were to be found among the cliffs enclosing the valley.

"Thee must have read of the ancient cliff-dwellers of this region," she said, "and so will understand when I tell thee that this place of abode and most of its contents were made by their hands, and that we are to-day leading the very life of that long-vanished people."

"But what became of them?" asked Todd.

"That is a mystery that many persons have tried in vain to solve. My husband is of the opinion that they were forced to migrate, either by flood or drouth, but expected to return, since they left their most valued possessions behind them, and carefully concealed the only entrance to the valley. Had they been destroyed by an enemy, their possessions would also have been destroyed or removed, whereas nothing had been touched from the day they left, probably hundreds of years ago, until that on which we were led to this place, and it was given to us for a house."

"It was very wonderful," said Todd; "but the strangest part of all is to find you and your husband and a young Indian living here so contentedly and comfortably. I can't understand it all, and wish you would tell me how it came about."

"Have a little patience and it shall be made clear to thee," replied the old lady, with a smile. "It is a tale of strange experiences, and I would gladly relate it, but I know the Professor has set his heart on telling it himself."

So Todd was forced to wait, and passed the morning in an examination of the dwelling and its contents. Later in the day he descended to the valley, where at the hut he found Nanahe cutting into thin strips, for drying, the meat of a deer that he had just brought in.

"How did you kill it?" asked Todd. "I didn't know you had a rifle."

"I have not, nor did I ever see one," replied the Indian lad. "I killed it with my throw-stick."

"Throw-stick?" repeated Todd, with a puzzled air. "What is a throw-stick?"

NANAHE EXHIBITS HIS THROW-STICK.

NANAHE EXHIBITS HIS THROW-STICK.

For answer Nanahe handed him a stick of tough wood two feet long, about as many inches in diameter, and fitted at one end with a handle in which were two finger-holes. The weapon was completed by a slender lance having a barbed head formed from a splinter of obsidian, keen-edged as a razor. Nanahe laid this lance on a flattened side of the throw-stick, with its butt resting against a bit of bone that was embedded in the wood near the upper end of the weapon. The lance was held in position by the thumb and one free finger of the thrower's right hand until the act of throwing was begun. Then it was released and sent whizzing through the air with such force that it fell to the ground more than one hundred yards away.

"Now I understand," cried Todd, "for I have often thrown apples from the end of a stick in just that way. But surely you can't throw the lance with any degree of accuracy."

Without replying, Nanahe smilingly selected half a dozen of the stone-headed shafts, and hurling one after another with inconceivable quickness at a tree some thirty yards from him, set them quivering in its bark so close together that a ring two inches in diameter would have encircled them all.

"Good enough!" cried Todd, enthusiastically. "I give in, and acknowledge that your throw-stick is a wonderfully effective weapon. But where did you pick up the idea?"

"The Professor found some of them in the cliff houses," answered Nanahe. "He says that in very ancient times all hunters used them, and that even now they are common among people called Eskimos who live in a far-away land of ice and snow. He taught me how to use them, and this one I made myself."

"Well," said Todd, "I begin to see how people get along and manage to live comfortably in a place like this; but it certainly takes genius to do it. As for myself, I know I should have starved long before I learned to kill a deer or even a rabbit with any such primitive weapon as a throw-stick. Now let's get back to the castle, for it must be supper-time, and after that I am to hear the Professor's strange story."

t was a crisp morning in late October. All the land was sere and yellow, darkening away into brown shadows. The trees kept their garments of leaves, but these were ragged and sombre, as if the heat of summer had worn and burned them. The grass at the foot of the trees was brown and gray, and the bare branches of the field bushes made naked perches for belated birds. The sky was wan and faint near the rigid horizon, but deeply blue in the zenith; and the sun, far down the southern vault of the heavens, rolled westward in a glory of silver. The sea was of a gorgeous ultramarine color, with a dash of royal purple in its shadows, and a glitter of cold emerald in its transparent crests. A light nor'west wind barely ruffled its surface, yet sufficed to fill the sails of a score of schooners which were ploughing a snowy road to the southward.

Henry and George felt that it was a good day for yarns, and so they hurried out of the house immediately after breakfast and bent their steps toward the pier. There they saw their old friend in his familiar attitude, with his eyes fixed on two steamers which were rapidly approaching each other from opposite directions. He did not turn his head as the boys approached him, but said, in a meditative manner,

"It are not no sort o' kind o' use fur to try to git past without shiftin' yer helm."

Then he relapsed into silence, while the two boys stood wondering what was coming next. Presently the Old Sailor broke out again,

"Do ye see them two steamers?"

"Yes," answered both boys.

"Waal, they are agoin' fur to pass putty close."

At that instant a gush of white steam rose from one of them, and the hoarse cry of her whistle rumbled across the water. The other vessel answered with a single blast.

"An' wot do that mean?" asked the Old Sailor.

"That means," answered Henry, "that they are going to port their helms and keep off to starboard."

"Werry good, too," declared the Old Sailor. "An' ef they didn't, wot'd happen?"

"They would bump into each other," answered George, soberly.

"W'ich the same it'd be a colligion," said the Old Sailor, "an' mebbe it would be like the colligion o' the Lord Kindlin'wood an' the Orange Mary, an' mebbe it wouldn't, 'cos w'y, I don't reckon there ever were no sich colligion afore, an' I don't reckon as how there ever will be agin."

"Will you please tell us about it?" asked Henry.

"In course I will, my son. W'enever I recomembers one o' them picooliar misfortins wot has happened to me at sea, I allus tells ye about it, don't I?"

The Old Sailor fixed his eyes on the two steamers, which were now passing each other very closely, and shook his head.

"It are all werry putty in clear an' calm weather," he said; "but it ain't no good wotever in weather wot are dirty. Waal may I never live to see a ship's cook at the fore-sheet ag'in ef it weren't jess like I'm agoin' fur to tell ye. I were in Liverpool an' didn't have no berth at all, so I were more'n half tickled to death w'en I met old Jonas Pettigrew, the shippin' agent, an' he sez to me, sez he, 'They 'ain't got no mate on the Lord Kindlin'wood yet.' I'd heerd about her. She were bound fur Calcutta an' Hong-kong by way o' the Suez Canal, an' her Cap'n were a Frenchman, 'cos she'd jess been bought by a French company in Canton. So I went down to the dock where she were a-takin' in her cargo, an' I sez to the Cap'n, sez I, 'Here are a mate fur ye.' His name were Zhan Four—anyhow, that's as near as I can come to wot he called hisself. 'Ala bonner,' sez he to me, sez he, w'ich the same it are French fur 'Bully fur you.' We soon come to tarms, an' I turned to.

"Waal, we didn't have no incidents or accidents o' no kind at all on the run down to Alexandry. Then the wind come in from the south'ard an' east'ard an' blowed putty nigh straight up the sea. I don't remember any nastier sea than it kicked up. The Lord Kindlin'wood would stand straight up on her starn-post, an' then take a pitch forrad and go clean into it up to her foremast. We had double lookouts up in the crow-nest, an' they was under water so much o' the time that they hollered fur divin'-suits.

"Waal, it blowed an' it blowed an' it blowed. It blowed so hard on the second day that it cut the tops right off'n the seas, an' sent 'em flyin' along like buckets o' rain, an' blow me fur pickled oysters ef ye could stand with your face up to wind'ard.

"Howsumever, we got used to it arter a while, an' the cook took to singin', so we knowed we was all right. But along about the middle o' the fust dog-watch one o' the lookouts yelled, 'Steamer ho!' I jumped into the fore-riggin' an' seed the wessel dead ahead o' us. She were a steamer about our own size, bound to the north'ard. She were runnin' at full speed ahead o' the gale, an' were drivin' along like the werry tops o' them seas wot I told ye about. Only she were actin' a little different from the Lord Kindlin'wood, 'cos w'y, she were a runnin' with the seas. So w'en one o' them would roll in under her starn she would h'ist her taffrail up into the air, an' plough forrad with her head down for all the world like a mad bull. Then the sea would underrun her an' git under her bow, an' she'd sit up on her starn-post with her bow p'inted away up in the air, an' like the werry tops o' them seas wot I told ye about. That were all right, but wot discomforted me w'en I saw her were that she were a-headin' right dead on end at us. Now we didn't dare fur to shift the Lord Kindlin'wood's helm an inch. We had to keep her head to the seas, 'cos w'y, it were the only way she'd lay to an' behave herself. The other wessel I sort o' reckoned, bein' about our size, would be in danger o' broachin' to ef she shifted her helm. So I were somewhat anxious 'bout how the two on 'em was agoin' fur to git past each other. I sent a man aft to call the Cap'n, an' he came on the bridge an' danced a reg'lar jig. 'Ef she turn not away she will make to the bow a bump!'

"'Wot is the orders, Cap'n?' sez I to he, sez I.

"'Blow the wheestle! Blow the wheestle!' sez he to me, sez he. An' accordin'ly I blowed it once, signifying accordin' to the rules o' the road at sea, that we were puffickly agreeable that both parties should keep to the right. The other ship she blowed hers back at us. O' course we couldn't hear nothin', but we could see the steam, an' we knowed she were agreeable. But she didn't change her course a little bit.

"'Dogs an' cats an' little kittens!' sez Cap'n Zhan Four, in French. 'Ef he change not the course, we are collided.'

"'Shall I order the helm to be shifted, Cap'n?' sez I to he, sez I.

"'Non! non! All the time non!' sez he to me, sez he. 'I turn not out of my path for such rubbeesh! I hit him in the meeddle, the miserable shadow of a dead horse!'

"'Werry good, sir,' sez I to he, sez I.

"An' I sez to the man at the wheel, 'keep 'er steady.' The other wessel, seein' we didn't change our course, blowed her whistle several times, but o' course that didn't 'nay pa riang,' as the Cap'n sez. Waal, to make the story short, this are edzackly wot happened. The Lord Kindlin'wood riz up over one o' them flat-topped seas, an' plunged head fust down the other side. At the werry same instant the stranger were sittin' up on her taffrail gittin' ready to dive down; an' consequentially we 'n the two ships come together precisely an' direckly head on, the stranger's bow overrun ours, an' she came down with her forefoot right on top o' our fo'c's'le deck. There were one grand crash, an' fur half a minute ye couldn't see nothin' 'cept flyin' timbers, iron, egg-shells, an' ham bones. In the middle of it all ye could hear the Cap'n screechin' in French, an' the two whistles a-blowin', an' the mates yellin' to clear away the boat-falls, 'cos w'y, it were not to be expected that both wessels would do anything 'ceptin' go to Davy Jones's locker in about five minutes. But they didn't, an' that are the picooliar part o' this 'ere yarn wot I'm a-tellin' ye, an' also the werry partikler reason w'y I are not a-feedin' Red Sea fish like Pharaoh's army.

"It warn't no sort o' proper behavior fur wessels wot, accordin' to the laws o' colligions, ort to gone to the bottom; but sich as it were, this were the bloomin' ridiklous way on't. The stranger's bow comin' down right on top o' ourn cut through the decks jess like a axe, straight down to the k'elson. An' there it stopped, bein' wedged in jess like the axe in a log, an' a dozen tugs couldn't 'a' pulled her out. An' wot we found out arter a few minutes, w'en we'd all got through bein' crazy, were that she were wedged in so tight that there weren't a leak anywhere at all, an' them two ships was actooally made into one, 'ceptin' that it were a new kind o' wessel with two starns, an' no more bow than a bass-drum. The Cap'n o' the stranger he comes forrad on a run an' a jump, and w'en he got to the place w'ere our cat-heads was alongside o' his he stopped, an' sez he, bawlin' like Feejee Injun in a fit o' cholery:

"'Donner unt blitzen! vot kind o' peezness vas dot? Vere ist der Gept'n?'

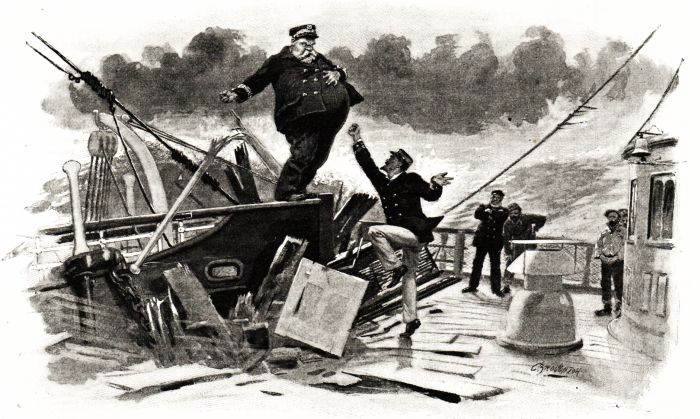

HE JUMPED CLEAN OFF THE BRIDGE AND DANCED ON ONE FOOT.

HE JUMPED CLEAN OFF THE BRIDGE AND DANCED ON ONE FOOT.

"Ye see, we l'arned by his way o' talkin' that he were a bloomin' Garman, an' I looked to see some fun w'en Cap'n Zhan Four an' him got laid yard-arm to yard-arm. But they couldn't edzackly do that, 'cos w'y, 'cos they was laid bow to bow, like a couple o' buckin' billy-goats in a fight. As soon as ever Cap'n Zhan Four heard the Garman Cap'n talk he jumped clean down off'n the bridge to the fo'c's'le deck an' danced on one foot, while he yelled:

"'Singe cornay of a Allemand!'—w'ich means dog-eared monkey of a Garman, an' are not no perlite way fur one gen'leman to address another at sea—'why do you make to knock a hole in my sheep?'

"'Ach, du dummer aysel!' sez the Garman, sez he; 'wot for you ton't ged your sheep out der vay?'

"'My sheep makes not to be in the way,' sez Cap'n Zhan Four, sez he; 'it is your sheep that comes straight at mine an' runs upon her, unessy pa?'

"'Donnerwetter!' sez the Garman, 'how could I dot help? I vas before der seas, unt you vas behint. Das macht nichts aus!'

"'Silonce!' screeched Cap'n Zhan Four. 'Speak not the accursed tongue of Garmany at me!'

"'Sprechen sie nicht dot frog talk at me!' howls the Garman. 'I speak der lankwitch von my vaterland alvays!'

"'Hoist the French flag!' sez Cap'n Four.

"'Up mit der Garman flag!" sez the Garman.

"An' as soon as the flags was run up them two crazy critters commenced fur to dance up an' down their two forrad decks right in each other's faces, one on 'em singin' the 'Marseillaise,' an' the other 'Die Wacht am Rhein,' like they was fit to bu'st theirselves. An' in the mean time, o' course, the two bloomin' ships, jammed together, slewed around broadside on to the sea, an' a big wall o' green water broke aboard an' putty nigh swept the two on 'em overboard. Anyhow, it put a stop to their singin', an' sot 'em a-thinkin' about their 'sheeps,' as they called 'em.

"'Back out you!' yelled Cap'n Zhan Four.

"'Nicht!' shouted the Garman. 'Ich back for no Frenchman alretty yet! Back you!'

"'Jammy! Jammy!' screeched Cap'n Four, an' 'jammy' it were, only that are French fur 'not on yer life!'

"'I go aheat full speet!' sez the Garman.

"'Ay maw,' sez Cap'n Four, w'ich the same that are French fur 'me too.' An' then them two wild men o' the sea orders their engines ahead full speed, an' the two ships commenced a grand pushin' match, fur all the world like one o' them there feet-ball games wot the long-haired collidge fellers plays in the mud every autumn. Now this 'ere shovin' game were a putty even match atwixt them there two ships, 'ceptin' fur one thing, an' that were that the Garman had the wind an' sea with him. So he commenced fur to push the Lord Kindlin'wood back'ards up north'ard toward the canal agin. Waal, boys, I reckon ye've seed a good many mad men, but ye 'ain't never seed none half or quarter as mad as that there French Cap'n Zhan Four. He said more funny things in French than ever I kin recomember, an' he got so red in the face that he putty near busted hisself. Howsumever, it didn't do no good, 'cos w'y, the Garman had the best on't in the matter o' the elements, an' he were steadily a-shovin' of us back to w'ere we come from, w'en the gale broke, an' the sea beginned fur to go down. The barometer riz, an' I looked fur a smart shift o' wind, w'ich the same it come along all right about three bells in the arternoon watch o' the second day. It dropped right around to nor'west, an' in ten minutes were blowin' a brisk breeze.

"'Sacred name of St. Michael!' sez Cap'n Zhan Four, sez he, 'now I push the Garman to the south pole!'

"'I hope ye ain't agoin' az fur as that,' sez I, ''cos I shipped fur Calcutta an' Hong-kong, an' I 'ain't got my seal-skin overcoat along with me,' sez I, jess like that, him bein' a crazy French Cap'n and me a werry partiklarly sane American mate.