UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Stewart L. Udall, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conrad L. Wirth, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER THIRTY-THREE

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D.C. Price 25 cents.

by Joseph P. Cullen

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES NO. 33

Washington, D.C., 1961

The National Park System, of which Richmond National Battlefield Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people.

Richmond, 1858. From a contemporary sketch.

The American Civil War was unique in many respects. One of the great turning points in American history, it was a national tragedy of international significance. Simultaneously, it was the last of the old wars and the first of the new. Although it began in a blaze of glamor, romance, and chivalry, it ended in the ashes of misery, destruction, and death. It was, as Walt Whitman said, “a strange, sad war.”

Richmond National Battlefield Park preserves the scenes of some of the great battles that took place in the vicinity of the Confederate Capital. When we visit these now quiet, peaceful woods and fields, we feel an association with our past that is impossible to achieve with the written or spoken word. Here we are not reminded of the Blue or the Gray as such, only of the heroic struggle of men—men with two different beliefs and philosophies, welded together by the blood of battle, to give us our America of today.

In session at Montgomery, Ala., in May 1861, the Confederate Congress voted to remove the Capital of the Confederate States to Richmond, Va. This decision, in effect, made Richmond a beleaguered city for 4 years. Essentially, the move was dictated by political and military considerations. The prestige of Virginia, richest and most populous State in the South, was considered necessary for the success of the Confederacy. For political reasons it was believed that the Capital should be near the border States and the heavy fighting expected there.

Second only to New Orleans, Richmond was the largest city in the Confederacy, having a population of about 38,000. It was also the center of iron manufacturing in the South. The Tredegar Iron 2 Works, main source of cannon supply for the Southern armies, influenced the choice of Richmond as the Confederate Capital and demanded its defense. During the course of the war, Tredegar made over 1,100 cannon, in addition to mines, torpedoes, propeller shafts, and other war machinery. It expanded to include rolling mills, forges, sawmills, and machine shops. The Richmond Laboratory made over 72 million cartridges, along with grenades, gun carriages, field artillery, and canteens, while the Richmond Armory had a capacity for manufacturing 5,000 small arms a month.

Tredegar Iron Works. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Thus Richmond became the political, military, and manufacturing center of the South, and the symbol of secession to the North.

Situated near the head of the navigable waters of the James River, and within 110 miles of the National Capital at Washington, Richmond was the key to the military planning of both sides. For 4 years the city remained the primary military objective of the Union armies in the east. As one southern newspaper stated: “To lose Richmond is to lose Virginia, and to lose Virginia is to lose the key to the Southern Confederacy.”

In July 1861 the untrained Union Army of the Potomac suffered disaster at Manassas (Bull Run) in the first attempt to drive into Virginia and capture Richmond. President Abraham Lincoln then appointed Gen. George B. McClellan the new commander of the 3 demoralized army. McClellan reported: “I found no army to command * * * just a mere collection of regiments cowering on the banks of the Potomac.”

To this chaotic situation he brought order and discipline. During the long winter months, the raw recruits were marshalled and drilled into an efficient fighting machine of over 100,000 men—the largest army ever commanded by one man in the history of the western hemisphere. By the spring of 1862 this army was ready for the supreme test—the goal was Richmond.

Instead of marching overland, McClellan decided to take advantage of Union control of the inland waters and transport his army, with its vast supplies and materiel, down the Potomac River and across Chesapeake Bay to the tip of the peninsula between the York and James Rivers. Then with his supply ships steaming up the York, he planned to march northwestward up the peninsula, join another force under Gen. Irvin McDowell marching overland from Washington, and together, converge on Richmond.

McClellan’s plan of attack. Painting by Sidney King.

To accomplish this, McClellan undertook the largest amphibious operation ever attempted in the western world. Over 400 steam vessels, brigs, schooners, sloops, ferry boats, and barges assembled on the Potomac River. In March 1862 these vessels ferried the Army of the Potomac, with its 3,600 wagons, 700 ambulances, 300 pieces of artillery, 2,500 head of cattle, and over 25,000 horses and mules, to the southeast coast of Virginia. As Q. M. Gen. Rufus Ingalls reported: “Operations so extensive and important as the rapid and successful embarkation of such an army, with all its vast equipment, its transfer to the peninsula, and its supply while there, had scarcely any parallel in history.”

After landing at Fortress Monroe the Federal troops pushed aside the thinly held Confederate defenses at Yorktown and Williamsburg and proceeded up the peninsula according to plan. But progress was slow. Every day 500 tons of forage and subsistence were required to keep the army in the field. Early in May it rained and kept raining, day after dreary day. Federal soldiers had a saying: “Virginia used to be in the Union—now it’s in the mud.” Dirt roads turned into bottomless muck—creeks and gullies became swift flowing streams—fields were swamps. Roads and bridges had to be built and rebuilt, and still the thousands of wagons, horses, and mules continually stuck in the mud.

Sumner’s troops crossing Grapevine Bridge to reinforce Coach at Seven Pines. From a contemporary sketch.

Realizing that an effective overland pursuit of the retreating Confederate forces under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston was out of the question because of the weather and the condition of the roads, McClellan on May 6 sent Gen. William B. Franklin’s division up the York River by transport to West Point, terminus of the Richmond and York River Railroad, in an attempt to cut off the Confederate wagon train. Johnston anticipated the move, however, and on May 7 ordered Gen. W. H. C. Whiting’s troops to attack Franklin in the battle of West Point, or Eltham’s Landing.

The attack was repulsed, but, even so, the wagon train managed to continue safely to Richmond. McClellan, however, had cleared the way to his next objective—the landing at White House on the Pamunkey River, a tributary of the York. Here the railroad crossed the Pamunkey on its way to West Point. This would be the Union base of supply for the contemplated attack on Richmond. This battle also cleared the way for the right wing of the Union army, which would have to stay north and east of Richmond in order to hook up with McDowell’s anticipated overland march from Washington.

General Johnston, falling back steadily in front of McClellan’s slow advance, was the target of severe criticism from Richmond newspapers for not making a determined stand. But he wrote to Gen. Robert E. Lee: “We are engaged in a species of warfare at which we can never win. It is plain that Gen. McClellan will adhere to the system adopted by him last summer, and depend for success upon artillery and engineering. We can compete with him in neither.”

After the fall of Norfolk on May 10 to the Union forces under Gen. John Wool, the crew of the Virginia (Merrimack) scuttled their ship. River pilots had advised that the iron-clad vessel could not navigate the treacherous channel up the James River to Richmond. Loss of the Virginia opened the river to Federal gunboats, and McClellan immediately telegraphed the War Department: “I would now most earnestly urge that our gunboats and the iron-clad boats be sent as far as possible up the James river without delay. Instructions have been given so that the Navy will receive prompt support wherever and whenever required.”

Five Union gunboats, including the famous Monitor, started up the James under Comdr. John Rogers in the Galena. By May 15 they reached Drewry’s Bluff, just 7 miles below Richmond. Here, at a sharp bend, the Confederates had effectively obstructed the river and erected powerful batteries on a 90-foot bluff.

Battle of Drewry’s Bluff. Diorama, Richmond National Battlefield Park Visitor Center.

At 7 that morning the Federal gunboats opened fire on Fort Darling. The battle raged for 4 hours while the fate of Richmond hung in the balance, and near panic spread through the city. However, the accurate fire of the heavy guns on the bluff, combined with effective sharpshooting along the riverbanks, finally proved too much for the gunboats, and the Federal fleet retreated down the river. One Confederate officer observed: “* * * had Commander Rogers been supported by a few brigades, landed at City Point or above on the south side, Richmond would have been evacuated.”

Although the Secretary of the Navy requested “a cooperating land force” to help the gunboats pass Fort Darling and take Richmond, McClellan, despite his earlier promise of cooperation, wired the War Department: “Am not yet ready to cooperate with them.” He neglected to say when he would be ready. Richmond was never again seriously threatened by water.

Slowed by the heavy rains and the bad condition of the roads, where “teams cannot haul over half a load, and often empty wagons are stalled,” McClellan finally established his base of supply at White House on May 15. Five days later his advance crossed the Chickahominy River at Bottoms Bridge. By the 24th the five Federal corps were established on a front partly encircling Richmond on the north and east, and less than 6 miles away. Three corps lined the 7 north bank of the Chickahominy, while the two corps under Generals E. D. Keyes and Samuel P. Heintzelman were south of the river, astride the York River Railroad and the roads down the peninsula.

Gen. George B. McClellan. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

With his army thus split by the Chickahominy, McClellan realized his position was precarious, but his orders were explicit: “General McDowell has been ordered to march upon Richmond by the shortest route. He is ordered * * * so to operate as to place his left wing in communication with your right wing, and you are instructed to cooperate, by extending your right wing to the north of Richmond * * *.”

Then, because of Gen. Thomas J. (“Stonewall”) Jackson’s brilliant operations in the Shenandoah Valley threatening Washington, Lincoln telegraphed McClellan on May 24: “I have been compelled to suspend McDowell’s movements to join you.” McDowell wrote disgustedly: “If the enemy can succeed so readily in disconcerting all our plans by alarming us first at one point then at another, he will paralyze a large force with a very small one.” That is exactly what Jackson succeeded in doing. This fear for the safety of Washington—the skeleton that haunted Lincoln’s closet—was the dominating factor in the military planning in the east throughout the war.

Lincoln’s order only suspended McDowell’s instructions to join McClellan; it did not revoke them. McClellan was still obliged to keep his right wing across the swollen Chickahominy.

Learning of McDowell’s withdrawal, Johnston decided to attack the two Federal corps south of the river, drive them back and destroy the Richmond and York River Railroad to White House. Early in the morning on May 31, after a violent rainstorm that threatened to wash all the Federal bridges into the river, Johnston fell upon Keyes and Heintzelman with 23 of his 27 brigades at Seven Pines.

The initial attack was sudden and vicious. Confederate Gen. James Longstreet threw Gen. D. H. Hill’s troops against Gen. Silas Casey’s division of Keyes’ corps, stationed about three-quarters of a mile west of Seven Pines. Longstreet overwhelmed the Federal division, forcing Casey to retreat a mile east of Seven Pines. Keyes then put Gen. D. N. Couch’s division on a line from Seven Pines to Fair Oaks, with Gen. Philip Kearney’s division on his left flank. Not until 4 that afternoon, however, did Confederate Gen. G. W. Smith send Whiting’s division against Couch’s right flank at Fair Oaks. The delay was fatal. Although Couch was forced back slowly, he drew up a new line of battle facing south towards Fair Oaks, with his back to the Chickahominy River. Here he held until Gen. Edwin V. Sumner, by heroic effort, succeeded in getting Gen. John Sedgwick’s division and part of Gen. I. B. Richardson’s across the tottering Grapevine Bridge to support him. Led by Sumner himself, Sedgwick’s troops repulsed Smith’s attack and drove the Confederates back with heavy losses.

The battle plan had been sound, but the attack was badly bungled. Directed by vague, verbal orders instead of explicit, written ones, whole brigades got lost, took the wrong roads, and generally got in each other’s way. Nine of the 23 attacking brigades never actually got into the fight at all. Towards nightfall Johnston was severely wounded in the chest and borne from the field. The command then fell to G. W. Smith. Fighting ceased with darkness.

Early next morning, June 1, Smith renewed the attack. His plan called for Whiting on the left flank to hold defensively, while Longstreet on the right swung counterclockwise in a pivot movement to hit Richardson’s division, which was facing south with its right near Fair Oaks. The Federal troops repulsed the assault, however, and when Heintzelman sent Gen. Joseph Hooker’s division on the Federal left on the offensive, the Confederates withdrew and the battle was over before noon.

That afternoon President Jefferson Davis appointed his chief military advisor, Gen. Robert E. Lee, as commander of the Southern forces. Lee promptly named his new command the Army of Northern Virginia—a name destined for fame in the annals of the Civil War.

McClellan’s troops repairing Grapevine Bridge. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Although the battle itself was indecisive, the casualties were heavy on both sides. The Confederates lost 6,184 in killed, wounded, and missing; the Federals, 5,031. Undoubtedly the most important result of the fight was the wounding of Johnston and the resultant appointment of Lee as field commander.

Lee immediately began to reorganize the demoralized Southern forces, and put them to work digging the elaborate system of entrenchments that would eventually encircle Richmond completely. For this the troops derisively named him the “King of Spades.” But Lee was planning more than a static defense. When the time came these fortifications could be held by a relatively small number of troops, while he massed the bulk of his forces for a counteroffensive. He was familiar with and believed in Napoleon’s maxim: “* * * to manoeuver incessantly, without submitting to be driven back on the capital which it is meant to defend * * *.”

On June 12 Lee sent his cavalry commander, Gen. J. E. B. (“Jeb”) Stuart, with 1,200 men, to reconnoiter McClellan’s right flank north 10 of the Chickahominy, and to learn the strength of his line of communication and supply to White House. Stuart obtained the information, but instead of retiring from White House the way he had gone, he rode around the Union army and returned to Richmond on June 15 by way of the James River, losing only one man in the process.

Gen. Robert E. Lee. Courtesy, National Archives.

Lee’s fortifications east of Mechanicsville Turnpike. From a contemporary sketch.

Chickahominy swamps. Courtesy, National Archives.

It was a bold feat, and Stuart assured his chief that there was nothing to prevent his turning the Federal right flank. But the daring ride probably helped McClellan more than Lee. Alerted to the exposed position of his right flank and base of supply, McClellan withdrew his whole army south of the Chickahominy, with the exception of Gen. Fitz-John Porter’s corps, which stretched from Grapevine Bridge to the Meadow Bridge west of Mechanicsville. On June 18 he started the transfer of his enormous accumulation of supplies with the shipment of 800,000 rations from White House to Harrison’s Landing on the James River. After Jackson’s success in the Shenandoah Valley at Cross Keys and Port Republic, it was becoming apparent even to McClellan that McDowell probably never would join him, in which case he wanted his base of operations to be the James rather than the York River.

Meanwhile, pressure from Washington for an offensive movement against Richmond was mounting. But because of the wettest June in anyone’s memory, McClellan was having trouble bringing up his heavy siege guns, corduroying roads, and throwing bridges across the flooded Chickahominy swamps. As one bedraggled soldier wrote: “It would have pleased us much to have seen those ‘On-to-Richmond’ people put over a 5 mile course in the Virginia mud, loaded with a 40-pound knapsack, 60 rounds of cartridges, and haversacks filled with 4 days rations.”

Also, McClellan believed erroneously that the Confederates had twice as many available troops as he had. Consequently, his plan of action, as he wrote his wife, was to “make the first battle mainly an artillery combat. As soon as I gain possession of the ‘Old Tavern’ I will push them in upon Richmond and behind their works; then I will bring up my heavy guns, shell the city, and carry it by assault.”

Lee’s plan of attack. Painting by Sidney King.

McClellan’s plan probably would have succeeded had Lee been willing to stand still for it. But the Confederate commander did not intend to let McClellan fight that type of warfare. As he wrote to Jackson: “Unless McClellan can be driven out of his entrenchments he will move by positions under cover of his heavy guns within 13 shelling distance of Richmond.” It was almost as if Lee had read McClellan’s letter to his wife.

Lee’s plan to drive McClellan away from Richmond was bold and daring, and strategically brilliant. He would bring Jackson’s forces down from the valley quickly and secretly to turn McClellan’s right flank at Mechanicsville. At the same time Gen. A. P. Hill’s division would cross the Chickahominy at Meadow Bridge, turn east and clear the Federal forces from Mechanicsville, thereby opening the Mechanicsville Turnpike bridge for D. H. Hill and Longstreet’s troops to cross. Then, in echelon, the four divisions would sweep down the north side of the Chickahominy, annihilate Porter’s corps, capture the supply base at White House, then turn and destroy the rest of the Union army. With Jackson’s forces and other reinforcements from farther south, Lee would have about 90,000 men, the largest army he would ever command in the field.

To protect Richmond, he planned to leave about one-third of his army, under Generals John B. Magruder and Benjamin Huger, in the entrenchments around the city to hold back the main part of McClellan’s force, about 70,000 men, from marching into the Confederate Capital. If this force started to withdraw, then Magruder and Huger would attack.

Lee apparently believed that McClellan would try to retreat to his base at White House, or failing that, would retire back down the peninsula. He assured Jefferson Davis that “any advance of the enemy toward Richmond will be prevented by vigorously following his rear and crippling and arresting his progress.” The strategy was just about perfect, but, unfortunately for Lee, the tactics were not.

On the morning of June 25 the Seven Days began with the advance of Hooker’s division along the Williamsburg road at Oak Grove, preparatory to a general advance McClellan planned for the next day. But Hooker ran into strong opposition from Huger’s troops, and when McClellan received intelligence of Jackson’s approach, Hooker was ordered back. McClellan wired Washington: “I incline to think that Jackson will attack my right and rear.” He had delayed too long—the next day Lee wrested the initiative from him.

According to Lee’s plan, Jackson was to march from Ashland on June 25 and encamp that night just west of the Central Railroad. At 3 a.m. on the 26th he was to advance and envelop Porter’s right flank at Beaver Dam Creek. Then, wrote Lee, “A. P. Hill was to cross the Chickahominy at Meadow Bridge when Jackson’s 14 advance beyond that point should be known and move directly upon Mechanicsville.”

Confederate attack at Beaver Dam Creek. From a contemporary sketch.

But from the beginning, unforeseen circumstances upset the operation and timing of this plan. McClellan suspected Jackson’s approach, so the element of surprise was lacking. And when the action of the Union pickets in destroying bridges and felling trees in Jackson’s path, as well as the fatigue of his weary troops, combined to delay him, the all-important time element was lost.

As the day wore on with no word from Jackson, A. P. Hill became impatient and fearful for the success of Lee’s plan. He decided to attack regardless. At 3 that afternoon he crossed the Chickahominy and swept the Union outposts from Mechanicsville, thus clearing the way for D. H. Hill and Longstreet’s troops to cross. Porter withdrew to a prepared position behind Beaver Dam Creek, a mile east of Mechanicsville. This naturally strong position was further fortified by felled trees and the banks of a millrace. Here, atop the high banks of the stream, he placed Gen. George McCall’s division, extending from near the Chickahominy on the south, across Old Church road (now U.S. 360) on the north. Gen. Truman Seymour’s brigade held the left and Gen. John Reynold’s the right, with Gen. George G. Meade’s brigade in reserve. The only approaches to the position were across open fields, commanded by the Federal artillery, and down the steep banks of the stream, covered by the soldiers’ muskets.

Hill recklessly hurled his brigades forward in a hopeless frontal assault. The gray-clad infantry charged bravely down the steep banks and up to the stream before the murderous fire of artillery and musketry from the surrounding slopes forced a bloody withdrawal. Casualties in killed and wounded were: Confederate 1,485; Union, 258.

Despite the successful defense, when Jackson’s forces finally appeared on his right flank later that night, Porter’s position became untenable and McClellan ordered him to withdraw to a previously prepared position behind Boatswain Swamp, near Gaines’ Mill. At the same time he ordered his quartermaster general at White House to reship all the supplies he possibly could to Harrison’s Landing on the James, and send all the beef cattle to the vicinity of Savage Station. Early next morning, June 27, the herd of 2,500 head of cattle started on its drive from White House.

Battle of Gaines’ Mill. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

McClellan’s change of base. Painting by Sidney King.

The tactical situation was now extremely critical for both Lee and McClellan. Because of the repulse at Beaver Dam, Lee had not yet achieved his first objective, which, according to his battle order, was to “drive the enemy from his position above New Bridge,” about 4 miles east of Mechanicsville. Lee’s whole plan for the defense of Richmond, in the event McClellan should elect to march on the city with his main force south of the Chickahominy, hinged on his ability to cross the river quickly and attack the Federal rear. Lacking control of New Bridge this would be impossible. Although the Union position behind Boatswain Swamp was actually east of New Bridge, the approaches to the bridge could be covered by Porter’s artillery.

The situation was equally serious for McClellan. With Jackson enveloping his right flank and rear, and believing he “had to deal with at least double” his numbers, White House would have to be abandoned. Having made the decision to change his base to the James, he desperately needed time to perfect the arrangements and to get the thousands of wagons and the herd of cattle safely started. His order to Porter was explicit, “hold our position at any cost until night * * *.”

Porter’s corps now occupied a semicircular line of battle along the crest of the partially wooded plateau behind Boatswain Swamp, with both extremes resting on the Chickahominy River. It was another naturally strong position further strengthened by felling trees and digging rifle pits. The approaches to the position were over an open plain and across a sharp ravine. Gen. George Morell’s division held the left and Gen. George Sykes’ right, with McCall’s weary troops in reserve. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke’s cavalry was on Porter’s extreme left, in the lowlands bordering the Chickahominy. During the course of the impending battle of Gaines’ Mill, Porter would be reinforced by Gen. Willard Slocum’s division, giving him a total strength of about 35,000, as opposed to about 60,000 for Lee.

On the Confederate side, Longstreet was on Lee’s right opposite Morell, A. P. Hill in the center, and Jackson and D. H. Hill on the left. Lee was convinced that the greater part of the Federal army was in his front, and he still thought McClellan would try to protect his base and retreat toward White House. On these erroneous assumptions he made his plans.

A. P. Hill would attack the center while Longstreet made a feint on the Union left. Then when Jackson appeared on the Union right, Lee believed Porter would shift part of his troops to meet Jackson’s threat in order to keep him from getting between the Union army and its base at White House. As soon as Porter did this, Longstreet would turn the feint into a full assault, and together with Hill drive the Union forces into Jackson and D. H. Hill, waiting on Lee’s left.

About 2:30 p.m. Hill attacked the center of the Federal line, but under a devastating fire of artillery and musketry, “where men fell like leaves in an autumn wind,” his troops were hurled back with heavy losses. Longstreet, realizing a feint now would not help Hill, ordered a full-scale attack, but he too suffered a bloody repulse. Jackson, sensing that “Porter didn’t drive worth two cents,” as he quaintly put it, threw D. H. Hill against Sykes on Porter’s right.

By now A. P. Hill’s division was badly cut up, and on Lee’s request Jackson sent Whiting’s division, consisting of Gen. E. M. Law’s and John B. Hood’s brigades, over to support him. Porter then threw in Slocum’s division of Franklin’s corps, to protect threatened points along the line. The vicious battle waged furiously for 4 hours. “The noise of the musketry,” said one veteran, “was not rattling, as ordinarily, but one intense metallic din.”

Finally, just as darkness covered the bloody field, Hood’s Texas brigade, along with Gen. George Pickett’s brigade on Longstreet’s left, penetrated the right of Morell’s line in a courageous bayonet charge that broke the morale of the Federal troops. They went streaming back across the plateau to the safety of the Chickahominy 18 River. In a last desperate attempt to stem the tide, General Cooke (“Jeb” Stuart’s father-in-law) sent his cavalry in a wild charge against the pressing Confederates. But the retreating Union infantry and artillery obstructed the cavalry and broke its attack. The only result was the loss of several more artillery pieces in the confusion.

With darkness closing in and the Confederate troops disorganized after the breakthrough, Lee did not attempt to pursue the Federals farther. Porter withdrew the remnants of his corps across the river and rejoined the main Union army. Total casualties in this crucial battle, the most costly and vicious of the Seven Days, were: Union, 6,837; Confederate, 8,751.

In a sense, both sides had achieved their immediate objectives. Porter had held until night, so McClellan could get his army safely started for Harrison’s Landing. Lee had cleared the north side of the Chickahominy of all Federal forces, broken their supply line to White House, controlled strategic New Bridge, and had turned back McClellan’s advance on Richmond.

Battle of Savage Station. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

McClellan was now engaged in the most difficult move an army can be called upon to make in the face of an aggressive enemy—a flanking movement to effect a change of base. There was no thought 19 given to any offensive movement. President Lincoln telegraphed: “Save your army at all events.” This was now McClellan’s only objective.

That McClellan had not tried to fall back on White House surprised Lee, as he had believed he was facing the main part of the Federal army at Gaines’ Mill. The next day, June 28, he spent burying the dead, reorganizing for another offensive movement, and attempting to divine McClellan’s plans. Lee reported to Jefferson Davis that “the bridges over the Chickahominy in rear of the enemy were destroyed, and their reconstruction impracticable in the presence of his whole army and powerful batteries. We were therefore compelled to wait until his purpose should be developed.” By nightfall, however, he realized that McClellan was headed for the James River, and made his plans accordingly.

Early next morning, June 29, Longstreet and A. P. Hill were to cross the Chickahominy at New Bridge and take the Darbytown road to where it met the Long Bridge road. Huger and Magruder, already on the south side of the river in front of Richmond, were ordered in pursuit of the Federal forces—Huger by Charles City road and Magruder by the Williamsburg road. In the meantime, Jackson would cross Grapevine Bridge and sweep down the south side of the river to get in McClellan’s rear.

Again, Lee’s strategy was brilliant. The Charles City road met the Long Bridge road at a place called Glendale or Frayser’s Farm. Lee planned to have all his divisions converge there at about the time the middle of McClellan’s long column should be passing. The impact of the expected blow would undoubtedly split the Union army, and with Jackson’s corps in the rear of one half, the other half could be cut off and annihilated. Once again, however, the staff work and tactics were pitiful.

McClellan’s rearguard was posted about Savage Station on the Richmond and York River Railroad, facing west. Richardson’s division, of Sumner’s corps, was in an open field north of the railroad tracks in back of the station. Sedgwick’s division held the center in another open field south of the tracks, with its left resting on the Williamsburg road. Gen. William F. (“Baldy”) Smith’s division, of Franklin’s corps, took position in the woods south of the Williamsburg road.

Magruder reached the vicinity of Savage Station about noon, June 29, but did not attack as he realized his four brigades were badly outnumbered. He halted and waited for Jackson, who was supposed to turn the Federal right flank along the Chickahominy and get in their rear. But Jackson “was delayed by the necessity of reconstructing Grapevine Bridge.” Magruder then mistakenly reported McClellan advancing and sent for two brigades from Huger to support 20 him. Lee cancelled the order when he realized that what Magruder had hit was only the rearguard covering the Federal army’s passage across White Oak swamp. What Lee did not realize, however, was that Jackson was not in position and would not reach Savage Station until 3 the following morning. Finally, about 5 that afternoon, Magruder attacked with his four brigades and two regiments, but it was too late with too little. The Federals withdrew hastily but safely. In their haste they were forced to leave 2,500 sick and wounded men in the field hospital at Savage Station and to abandon or destroy a vast amount of supplies and equipment.

Battle of Savage Station. From a contemporary sketch.

Battle of Glendale. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

Lee now ordered Magruder to follow Longstreet and A. P. Hill down the Darbytown road. The next day, June 30, Longstreet and Hill came upon the Union troops of McCall and Kearney across the Long Bridge road about a mile west of the Charles City road intersection at Glendale. Hooker held the left or south flank, with Slocum on the right guarding the Charles City road approach. Sedgwick was in the rear in reserve. Longstreet and Hill halted and waited for Huger, coming down the Charles City road, and Jackson, supposedly coming on the Federal rear from White Oak Swamp.

Meanwhile, Gen. T. H. Holmes, who had come from the south side of the James River with part of his division and Gen. Henry A. Wise’s brigade, had been sent by Lee down the River, or New Market road in an attempt to get between McClellan and the James River. McClellan anticipated the move, however, and Warren of Sykes’ division stopped Holmes south of Malvern Hill. Lee then 22 ordered Magruder on the Darbytown road to reinforce him, but Magruder’s forces did not get there in time to help.

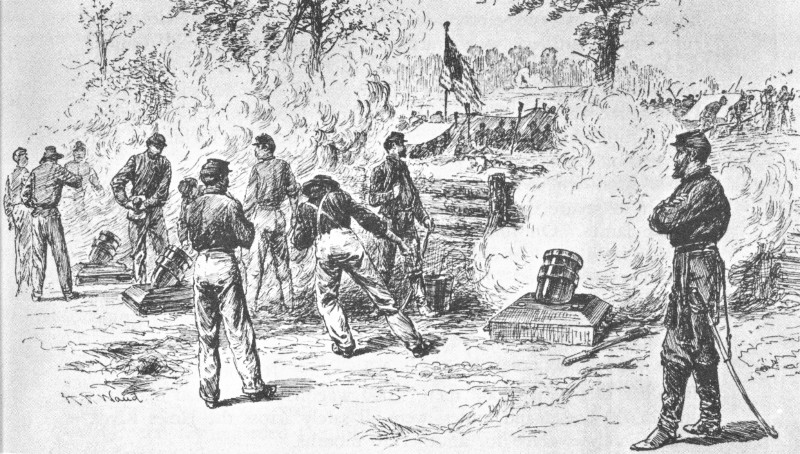

Huger was delayed by obstructions, mostly felled trees, with which the Federals had blocked his path. Instead of going around the obstructions, Huger continually halted to clear the road. Thus it resolved itself into a question of whether Huger could clear the trees as fast as the Union soldiers cut them down. In this so-called “battle of the axes” Huger lost, and did not get to Glendale in time to participate in the engagement.

About 4 that afternoon, however, Longstreet heard artillery firing from Huger’s direction which “was supposed to indicate his approach,” and expecting Jackson’s appearance momentarily, he opened with one of his batteries and thus brought on the battle. Jackson never did show up, being held north of White Oak Swamp by the artillery of Richardson and Smith, and did not get to Glendale until the next day. The fight was particularly vicious with many pockets of hand-to-hand combat, but, without the expected support of Huger and Jackson, Longstreet could not break the Union lines in time to inflict any serious damage or to interrupt the withdrawal. Lee stated in his report: “Could the other commands have cooperated in the action the result would have proved most disastrous to the enemy.” Gone was Lee’s last chance to cut McClellan’s army in two.

McClellan had already selected another naturally strong position, this time on Malvern Hill, for the last stand before reaching the James River. On the morning of July 1, Morell and Sykes’ divisions of Porter’s corps were drawn up on the crest of the hill west of the Quaker road. East of the road Couch’s division of Keyes’ corps held the front, with Kearney and Hooker of Heintzelman’s corps flanked to the right and rear. Sumner’s troops were in the rear in reserve. The position was flanked on either side by creeks in deep ravines less than a mile apart, and across this narrow front, Porter placed his batteries with the guns almost hub to hub. In front, the ground was open, sloping down to woods, marshes, and swamps, through which the Confederate forces had to form for attack within range of the Federal artillery.

Lee had Jackson on his left facing Kearney, Hooker, and Couch’s right. D. H. Hill was in the center opposite Couch’s left and Morell’s right. Lee then ordered Magruder to the right of Hill, but Magruder was delayed by taking the wrong road; so instead two brigades of Huger’s were placed on Hill’s right. Longstreet and A. P. Hill, their ranks decimated from the actions at Gaines’ Mill and Glendale, were held in reserve. The terrain rendered it almost impossible for effective use of Confederate artillery, and the few batteries that did get into position were quickly cut to pieces by the massed Union guns.

Battle of Malvern Hill. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

“Owing to ignorance of the country, the dense forests impeding necessary communications, and the extreme difficulty of the ground,” Lee reported, “the whole line was not formed until a late hour in the afternoon.” The first real assault did not take place until after 5, and then it was uncoordinated and confused. The signal for the attack was to be a yell from one of Huger’s brigades, after the Confederate artillery had blasted a hole in the Union lines. This put the responsibility of where and when to begin the attack on a mere brigade commander.

The artillery was unable to put concentrated fire in any one spot, but Huger attacked regardless and was beaten back with heavy losses. Then D. H. Hill attacked, only to suffer the same fate. Magruder finally sent his troops in a gallant charge across the open fields right up to the cannons’ muzzles, only to be mowed down like wheat at harvest time. Late in the battle Jackson sent his own division to Magruder’s and Hill’s support, but in the heavily wooded and swampy ground they got lost and did not arrive in time to help. Darkness finally put an end to these hopeless attacks. As D. H. Hill declared bitterly, “It was not war—it was murder.”

McClellan’s withdrawal. From a contemporary sketch.

During the night McClellan continued his withdrawal, and the next day found the Army of the Potomac safe at Harrison’s Landing 25 under the protection of the Federal gunboats on the James. The Seven Days were over. Total casualties: Army of Northern Virginia, 20,614; Army of the Potomac, 15,849.

Army of the Potomac at Harrison’s Landing. From a contemporary sketch.

In his official report of the campaign Lee stated: “Under ordinary circumstances the Federal Army should have been destroyed. Its escape was due to * * * the want of correct and timely information. This fact, attributable chiefly to the character of the country, enabled Gen. McClellan skillfully to conceal his retreat and to add much to the obstructions with which nature had beset the way of our pursuing columns * * *.” But his other objective had been achieved—Richmond was safe, at least for the time being.

While McClellan had successfully changed his base of operations from the York to the James River and saved his army in the process, he had failed in his first objective of capturing Richmond and possibly ending the war. The decision to remove the army from the peninsula, rather than reinforce it for another attempt on Richmond, was made in Washington over McClellan’s strong objections. He wrote to Gen. Henry W. Halleck: “It is here on the banks of the James, that the fate of the Union should be decided.”

McClellan’s cartographers. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Although McClellan wisely realized the advantages of another assault on Richmond on the line of the James, it was his own mistaken view of Lee’s strength that was the major reason for the withdrawal. As Halleck explained to him:

You and your officers at one interview estimated the enemy’s forces in and around Richmond at 200,000 men. Since then you and others report that they have received and are receiving large re-enforcements from the South. General Pope’s army covering Washington is only about 40,000. Your effective force is only about 90,000. You are 30 miles from Richmond, and General Pope 80 or 90, with the enemy directly between you, ready to fall with his superior numbers upon one or the other, as he may elect. Neither can re-enforce the other in case of such an attack. If General Pope’s army be diminished to re-enforce you, Washington, Maryland, and Pennsylvania would be left uncovered and exposed. If your force be reduced to strengthen Pope, you would be too weak to even hold the position you now occupy should the enemy turn around and attack you in full force. In other words, the old Army of the Potomac is split into two parts * * * and I wish to unite them.

In August the Army of the Potomac was transported by water back to Washington to support Pope’s campaign in Northern Virginia. McClellan’s failure to capture the Confederate Capital, combined with Lee’s failure to destroy the Union Army, assured the nation a long, bitter war that became one of the great turning points in American history.

Richmond, summer of 1862. From a contemporary sketch.

In August 1862 Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis: “If we are able to change the theater of the war from the James River to the north of the Rappahannock we shall be able to consume provisions and forage now being used in supporting the enemy.” So Lee moved into Northern Virginia to meet Pope’s threatened overland campaign against Richmond. At Second Manassas (Bull Run) the Union army was defeated again and withdrew into the fortifications around Washington.

Lee took advantage of this opportunity and made his first invasion north into Maryland, only to be defeated by McClellan at Antietam (Sharpsburg) in September. Lee then withdrew into Virginia, and at Fredericksburg in December he severely repulsed Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s move on Richmond. In the spring of 1863 the Union army, now under Hooker, attempted to flank Lee’s left and rear to cut him off from Richmond, but it was decisively defeated at Chancellorsville and driven back across the Rapidan. Lee then made his second thrust north, penetrating into Pennsylvania, but was beaten back by Meade at Gettysburg in the summer of 1863 and, once again, retired into Virginia.

These gallant armies fought each other across the fields of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia before they clashed again in the outskirts of Richmond 2 years later.

In March 1864 President Lincoln appointed Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as commanding general of all the Union armies. Said Grant: “In the east the opposing forces stood in substantially the same relations toward each other as three years before, or when the war began; they were both between the Federal and Confederate Capitals. Battles had been fought of as great severity as had ever been known in war * * * from the James River to Gettysburg, with indecisive results.” He hoped to change this situation by putting pressure on all Confederate armies at the same time, something that had never been done before.

Grant’s plan called for Gen. Benjamin F. Butler to march up the south side of the James and attack Petersburg or Richmond or both; Gen. Franz Sigel to push down the Shenandoah Valley driving Gen. Jubal Early before him, thereby protecting Washington; Gen. Nathaniel Banks in New Orleans to march on Mobile; Gen. William T. Sherman to cut across Georgia driving Johnston before him, take Atlanta, and if necessary swing north to Richmond; Meade’s Army of the Potomac, with Grant in command, to push Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and capture Richmond. As Grant stated: “Lee, with the Capital of the Confederacy, was the main end to which all were working.”

Lee’s objective now was to stop Grant and protect Richmond. Said Lee: “We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.”

The campaign started in the spring of 1864 when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and the Army of Northern Virginia blocked its path at the Wilderness. After a particularly vicious and costly battle, Grant instead of retreating to lick his wounds as other Federal commanders had done, executed a left flank movement, still heading south and trying to get between Lee and Richmond. A few days later the two armies clashed again at Spotsylvania in a series of grim battles, but still indecisive as far as major objectives were concerned. Although Grant’s losses were staggering, he was slowly but methodically destroying Lee’s ability to wage offensive war.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. From a contemporary sketch.

Again Grant executed a left flank movement to get around Lee, and then by a series of flanking marches, which the Confederate soldiers called the “sidling movement,” and the Union soldiers the “jug-handle” movement, Grant gradually worked his way down to Cold Harbor.

Where and what was Cold Harbor? Cold Harbor was a seedy-looking tavern, squatting by a dusty crossroads 8 miles from Richmond, on the flat, featureless plain, intersected by hundreds of small 30 creeks, gullies, and swamps, that is characteristic of the land between the Pamunkey and the Chickahominy Rivers. There wasn’t a harbor for miles and it was anything but cold. It was the only Cold Harbor in the United States, although there were many Cold Harbors on the stagecoach routes along the Thames River in England. The name indicated a place to get a bed for the night and something cold to drink, but not hot meals.

Cold Harbor Tavern. From a photograph taken in 1885 as it appears in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

But these dusty crossroads were strategically important if Grant was to attack Richmond, and both Lee and Grant realized it. Also, it was Grant’s last chance to continue his strategy of trying to get between Lee and Richmond—any more flanking movements and Lee would be in the entrenchments around the Confederate Capital where Grant did not want to fight him. As Grant stated: “Richmond was fortified and entrenched so perfectly that one man inside to defend was more than equal to five outside besieging or assaulting.”

It is significant that Lee also did not want to fight in the entrenchments around Richmond. There he would be on the defensive, and in such a position could not possibly destroy Grant’s army. So both commanders were willing for the test.

And what of the lowly foot-soldier, the unsung hero in the ranks, the poor bloody infantryman? Was he ready for the awful test?

Confederate camp. From a contemporary sketch.

To the average soldier, this whole campaign was fast becoming just a series of hazy, indistinct recollections, like the fragments of a half-forgotten dream: Long columns of sweat-soaked soldiers marching over hills and rivers and swamps, across ploughed fields and corn fields, down endless dusty roads through dark, lonely woods; 30 days of marching by night and fighting by day, until it must have seemed to them that the only things left in life were stupefying fatigue, merciless heat, choking dust, smoke and noise, mud and blood.

In the Union ranks many of the men began to find out for the first time what hunger really was. They had moved so fast and so often the ration wagons were left far behind. Hardtack was selling for a dollar apiece—if you could find a seller. And here at Cold Harbor the soldiers wrote their names and regiments on pieces of paper and pinned or sewed them to the inside of their dirty blouses, with the forlorn hope that if and when they were killed someone might take the time to find out who they were.

To Lee’s barefoot, ragged veterans, hunger had been a constant companion for a long time, but at Cold Harbor they approached starvation. A Confederate sergeant recorded in his diary: “When we reached Cold Harbor the command to which I belonged had 32 been marching almost continuously day and night for more than fifty hours without food, and for the first time we knew what actual starvation was.” When scurvy appeared among the men, owing primarily to a lack of fresh vegetables, Lee advised them to eat the roots of the sassafras and wild grape, if they could find any.

In the race for initial possession of the crossroads at Cold Harbor, Lee’s cavalry won by a few hours. But in the afternoon of May 31 Gen. Philip Sheridan’s cavalry drove them out and held the crossroads until relieved by the Federal VI Corps under Gen. Horatio Wright. Most of Sheridan’s troopers were armed with the new Spencer repeating carbine, which made dismounted cavalrymen effective infantry.

The next morning, June 1, Lee threw Gen. Richard Anderson’s corps (Longstreet’s old corps—Longstreet having been wounded in the Wilderness) against the Federal VI Corps in a bold attempt to seize the crossroads and roll up Grant’s left flank before he could reinforce it, but Anderson was repulsed. Grant then moved the XVIII Corps under “Baldy” Smith, which he had borrowed from Butler’s army bottled up on the south side of the James, over to the right of the VI Corps. That afternoon they attacked Anderson, now supported by Gen. Robert Hoke’s division.

The assault failed to break the Confederate line, but it did bend it back in several places. Grant believed that with a greater concentration a breakthrough could be achieved. Consequently, he ordered the II Corps under Gen. Winfield Hancock over to the left of the VI Corps, between it and the Chickahominy River, and planned an all out attack by the three corps for the morning of June 2.

Anticipating the move, Lee put A. P. Hill, supported by Gen. John Breckinridge’s division, over to his right between Anderson and the Chickahominy and waited.

The expected attack failed to materialize, however. Hancock got lost in the woods and swamps moving to his assigned position, and after an all-night forced march the men were too exhausted to mount an attack. Any chance the assault might have had for success was now gone. The delay was fortunate for Lee because Breckinridge also got lost and was not in position to support Hill on the morning of June 2. The attack was then ordered for that afternoon but again postponed until 4:30 the morning of June 5. And each corps commander received a telegram from Grant’s headquarters that read: “Corps Commanders will employ the interim in making examinations of the ground in their front and perfecting arrangements for the assault.”

Lee’s veterans took advantage of this fatal 24-hour delay to entrench themselves quickly and effectively, using every creek, gully, ravine, 33 and swamp in such fashion that all approaches to their positions could be covered with a murderous fire. A newspaper reporter present at Cold Harbor wrote a vivid description of those entrenchments. “They are intricate, zig-zagged lines within lines, lines protecting flanks of lines, lines built to enfilade opposing lines * * * works within works and works outside works, each laid out with some definite design.”

Lee needed this strong position; he would fight at Cold Harbor without a reserve. He wrote to Jefferson Davis: “If I shorten my lines to provide a reserve, he will turn me; if I weaken my lines to provide a reserve, he will break them.”

Grant’s battle plan was relatively uncomplicated. It was, essentially, a simple, frontal assault. Hancock’s II Corps and Wright’s VI Corps, between the Chickahominy and the Cold Harbor road (now State Route 156), together with Smith’s XVIII Corps north of the road, were to attack all out and break the Confederate lines. Gen. Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps, north of the XVIII, was to be held in reserve, while Burnside’s IX Corps, on Grant’s extreme right, was not to enter the fight unless Lee weakened his line in that sector, then it would attack, supported by the V Corps. Lee did not weaken any part of his line, so these two corps were not engaged to any appreciable extent. Thus the battle actually took place on approximately a 2½-mile front, although the armies stretched for 6 miles from south to north, with the Union army facing west. Grant’s total strength was over 100,000 men, but less than 50,000 were actually engaged in the struggle.

Lee now had A. P. Hill, supported by Breckinridge, on his south flank next to the Chickahominy opposite Hancock and Wright. Hoke’s division straddled the Cold Harbor road with Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s division just north of Hoke, then Anderson and Gen. Richard Ewell’s corps. Lee’s total strength consisted of less than 60,000 men, but only about half were involved in the action of June 3.

It rained all night the night of June 2. Toward morning the heavy rain died to a soft, sticky mist that held the area in clammy fingers. The first gray streaks of dawn warned of the approach of a scorching sun that would turn the rain-soaked plain, with its myriad streams and swamps, into a steaming cauldron. Promptly at 4:30 the three corps jumped off to the attack, knowing nothing of the strength of the Confederate positions they would have to face. The corps commanders had ignored Grant’s telegraphed order of the previous afternoon and no proper reconnaissance was made.

The average soldier saw little in any battle in the Civil War, and even less at Cold Harbor because of the terrain. But as the first yellow rays of the sun shifted the gray mists, most of the Union 34 soldiers could see the main line of Confederate entrenchments across the open spaces in front of them—a tracing of raw earth that had been turned up like a huge furrow, along a line of uneven ridges, looking empty but strangely ominous. Here and there bright regimental colors perched insolently on the dirt hills.

Suddenly, it seemed, the line was dotted with black slouch hats and glistening bayonets. Yellow sheets of flame flashed from end to end, then disappeared in a heavy cloud of smoke. Regiment after regiment exploded into action with a metallic roar. Gigantic crashes of artillery split the air. Shells screamed overhead like a pack of banshees, exploding in clouds of earth, horses, and men. The noise roared to a crescendo with a volume of sound that left the men dazed and confused. One veteran said it was more like a volcanic blast than a battle.

It was over in less than 30 minutes, but 7,000 killed and wounded Union soldiers were left lying in the sun between the trenches. Said one general sadly: “In that little period more men fell bleeding as they advanced than in any other like period of time throughout the war.”

Those not already killed or wounded threw themselves on the ground and desperately heaved up little mounds of earth in front of them with bayonets, spoons, cups, and broken canteens. They could neither advance nor retreat—nothing standing could live long in that hail of lead and iron. They just dug in and stayed there.

A peculiar thing about the battle came to light afterwards. The three corps commanders sent identical telegrams to Grant’s headquarters, each accusing the other of not supporting him in the attack. Later it was discovered what had actually happened. Hancock, on the left, had veered to his left because of the heavy fire from there and the peculiarities of the terrain. Wright, in the center, had gone straight ahead. And Smith, on the right, bore off to his right because of swamps and ravines. So the farther they advanced the more separated they became and the more their flanks were left open to a deadly crossfire.

No other major assault was attempted by either army, although the troops stayed in the hot, filthy trenches until June 12, with constant, nerve-wracking sharpshooting and skirmishing. From June 1 to 12 the Union losses totaled 12,700; Confederate losses are estimated at between 1,500 and 2,000.

Cold Harbor proved to be Lee’s last major victory in the field, and although it was a military zero so far as Grant was concerned, it turned out to be one of the most important and significant battles fought during the Civil War. The results of this battle changed the course of the war in the east from a war of maneuver to a war of siege. It also influenced the strategy and tactics of future wars by showing that well-selected, well-manned entrenchments, adequately supported by artillery, were practically impregnable to frontal assaults.

Federal trenches at Cold Harbor. From a contemporary sketch.

Federal coehorn mortars at Cold Harbor. From a contemporary sketch.

Looking for a friend at Cold Harbor. From a contemporary sketch.

On June 5, Grant decided to bypass Richmond, cross the James and attack Petersburg, an important railway center 25 miles south of the Confederate Capital. This would still keep Lee’s army pinned down, and if successful would cut communications between Richmond and the rest of the Confederacy.

On June 6 he withdrew Warren’s V Corps from the lines and used it to secure the passages across the Chickahominy and down to the James. On June 7 he sent Sheridan, with two divisions of cavalry, back into the Shenandoah Valley against Early. To counter this, Lee was forced to send Gen. Wade Hampton’s cavalry after Sheridan, which in effect left Lee without adequate cavalry. During the night of June 12 Grant secretly moved all the troops out of the trenches at Cold Harbor, without Lee’s being aware of the move until the following morning, and by June 16 the Army of the Potomac of over 100,000 men, 5,000 wagons, 2,800 head of cattle, and 25,000 horses and mules, were all safely across the James River. Richmond was saved for another 10 months.

Pontoon bridge across the James. Courtesy, National Archives.

In the pre-dawn darkness of September 29, Grant quietly slipped Gen. David Birney’s X Corps and Gen. Edward Ord’s XVIII Corps back across the James in a surprise move against the outer defenses of Richmond. The primary purpose was to prevent Lee from re-enforcing Early in the Shenandoah Valley. If, however, any weakness was discovered it could be exploited fully, and it might force Lee to weaken some part of the Petersburg line.

Shortly after daybreak Gen. George Stannard’s division of the XVIII Corps successfully stormed heavily armed but badly undermanned Fort Harrison on the Varina road. Gen. Hiram Burnham, commanding the leading brigade, was killed in the assault and the Union forces renamed the captured fort for him. A mile and a half farther north, Gen. Adelbert Ames’ division of the X Corps was repulsed in a similar attack on another fortification, Fort Gilmer, on the New Market road.

Area of the Richmond battlefields. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

General Lee regarded the loss of Fort Harrison as serious enough to demand his personal attention. The next day, with re-enforcements rushed from Petersburg, he directed several vigorous assaults against the fort. However, the Union forces had closed in the rear and strengthened it, and, armed with new repeating rifles, successfully beat back the attacks and inflected heavy losses on the Confederates.

Members of the 1st Connecticut Artillery at Fort Brady, 1864. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

The fall of Fort Harrison forced Lee to draw back that part of his outer line and to build new entrenchments to compensate for the loss. It also forced him to extend his line north of the James, thus weakening his already dangerously undermanned defenses in front of Petersburg. The Union forces, to protect their position further and to neutralize Confederate gunboats, constructed Fort Brady a few miles south of Fort Burnham (Harrison) on a high bluff overlooking the James River.

No further serious efforts were made to enter Richmond from the north side of the James, and the two armies faced each other in these respective positions until Grant finally broke Lee’s lines at Petersburg on April 1, 1865, forcing the Confederates to abandon Richmond.

Spring came gently to Richmond that year of 1865. The winter had been long and hard. After a cold, wet March, Sunday, April 2, dawned mild and pleasant. The green buds on the trees and the bright new grass put the breath of seedtime in the air; sap flowed warm in the lilac and the magnolia. Under a rich blue sky the people strolled leisurely to church amid the cheerful music of the bells and the soft murmur of the James River falls.

In St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, at the corner of Ninth and Grace streets, Jefferson Davis sat in the family pew listening to the sermon. The sexton walked up the aisle and handed him a message from General Lee.

“I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight.”

Davis arose quietly and left the church, walked a block down Ninth street to his office in the War Department and gave the necessary orders for evacuation.

Late in the afternoon the official order was posted—then pandemonium reigned. Trunks, boxes, bundles of every description were piled on the sidewalks and in the streets. Wagons, carts, buggies, anything that had wheels and could move, were loaded and raced through the city to fight their way across Mayo’s Bridge in the mad rush to cross the James and flee south.

A frantic mob trampled each other without mercy and jammed the streets leading to the railroad stations, only to be turned back by soldiers’ bayonets. The few trains that would manage to leave were reserved for government officials, archives, the treasury, and military personnel.

Early in the evening the character of the crowds began to change. From a city of less than 38,000 before the war, Richmond now had over 100,000 people jammed into every available nook and cranny. They had come by the thousands to work for the various government departments and in the munitions factories. Refugees from the many battles fought in Virginia had poured in, as well as the sick and wounded, followed inevitably by deserters, spies, criminals, gamblers, speculators, and derelicts of every kind.

And now the cheap hotels, saloons, and gambling dens began to empty their customers into the streets, many of them half drunk.

All semblance of law and order disappeared. When the guards at the State penitentiary fled, the prisoners broke loose to roam the city at will. The provost guard took the prisoners of war from Libby Prison down the river to be exchanged. This left only the Local Defense Brigade, consisting of government and munitions workers. But most of them were required in government buildings 41 to pack and burn records; some guarded the railroad depots, while others were engaged in destruction assignments. The order had been given to burn all tobacco and cotton that could not be removed by tossing flaming balls of tar into the warehouses along the riverfront.

In the meantime, Mayor Mayo and the city council had appointed a committee in each ward to see that all liquor was destroyed, and shortly after midnight they set to work. Casks and barrels of the finest southern bourbons were rolled to the curbs, the tops smashed open and left to drain.

Like flies around honey, the mobs swarmed and fought their way into the streets where the whiskey flowed like water. Men, women, and children, clawing and screaming, scooped it up with bare hands, or used pails, cups, basins, bottles, anything that would hold the amber liquid. They used rags on sticks dipped in whiskey for torches, and went howling through the city in search of food and plunder like a pack of mad wolves, looting, killing, burning.

The soft night sky became pink, then turned a dull red. The blaze from the Shockhoe Warehouse at Thirteenth and Cary streets, where 10,000 hogsheads of tobacco was put to the torch, flew skyward as if shot from a huge blowtorch. The flames quickly spread to the Franklin Paper Mills and the Gallego Flour Mills, 10 stories high. Higher and higher they soared, and then widened until it seemed a red hot sea of fire would engulf the whole city.

Evacuation of Richmond. From a contemporary engraving

A faint hot breeze began to stir from the southeast, scattering burning embers through the streets and alleys and houses. Powder magazines and arsenals let go with a whooshing boom. Thousands of bullets and shells tore through buildings and ploughed up the streets. Shells exploded high in the smoke cascading a metal spray over the area, followed by the rattle of bursting cartridges in one great metallic roar. Just before daybreak a deafening explosion from the James River signalled the destruction of the Confederate warships and the Navy Yard.

Richmond was now one vast inferno of flame, noise, smoke, and trembling earth. The roaring fire swept northwestward from the riverfront, hungrily devouring the two railroad depots, all the banks, flour and paper mills, and hotels, warehouses, stores, and houses by the hundreds.

About dawn a large crowd gathered in front of the huge government commissary at Fourteenth and Cary streets, on the eastern edge of the fire. The doors were thrown open and the government clerks began an orderly distribution of the supplies. Then the drunken mob joined the crowd.

Barrels of hams, bacon, flour, molasses, sugar, coffee, and tea were rolled into the streets or thrown from windows. Women ran screaming through the flames waving sides of bacon and whole hams. Wheelbarrows were filled and trundled away. When the building finally caught fire from the whiskey torches, the mob swarmed into other sections of the doomed city where the few remaining clothing, jewelry, and furniture stores were ruthlessly looted and burned. A casket factory was broken into, the caskets loaded with plunder and carried through the streets, and the fiendish rabble roared on unchecked.

As the drunken night reeled into morning the few remaining regiments of General Kershaw’s brigade, which had been guarding the lines east of Richmond, galloped into the city on their way south to join Lee in his retreat to Appomattox. They had to fight their way through the howling mob to reach Mayo’s Bridge. As the rearguard clattered over, Gen. M. W. Gary shouted, “All over, good-bye; blow her to hell.”

The barrels of tar placed along the bridge were promptly put to the torch. Soon tall flames shot high into the air, and with the two railroad bridges already burning, the three high-arched structures were like blazing arrows pointing to the very gates of hell.

Then down Osborne Turnpike and into Main Street trotted the Fourth Massachusetts cavalry. When the smoke and heat blocked their path, they turned into Fourteenth Street past fire engines blazing in the street and proceeded up the hill to Capitol Square, where a tragic scene awaited them.

Richmond burns. From a contemporary sketch.

Like a green oasis in a veritable desert of fire and destruction, the sloping lawn around the Capitol was jammed with frightened people seeking safety from the flames. Family groups, trying desperately to stay together, huddled under the linden trees for protection from the burning sparks. Piles of furniture were scattered in every direction—beds, chairs, settees, paintings, silverware, gilt-framed mirrors—the few possessions left, the family heirlooms, the treasures faithfully passed down from generation to generation. In the background the massive white columns of the Capitol, designed by Thomas Jefferson as a replica of the famous Maison Carée at Nimes, stood guard over the huddled masses below.

The soldiers in blue quickly dispersed the mobs at bayonet point. Guards were immediately placed to prevent further looting. The fire was contained by blowing up buildings in its path to create a fire-lane, leaving the main part to burn itself out. By nightfall everything was under control, but most of the business and industrial section of the city was gone.

The stars shone down that night on the smouldering ruins of more than 700 buildings. Gaunt chimneys stood naked against the black velvet sky. A Federal officer, picking his way through thousands of pieces of white granite columns and marble facades that littered the streets to inspect the guard, noted that the silence of death brooded over the city. Occasionally a shell exploded somewhere in the ruins. Then it was quiet again.

A week later Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Va. The war was over.

Richmond after the war. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Richmond National Battlefield Park.

Richmond National Battlefield Park was established on July 14, 1944, as authorized by act of Congress. The property was originally acquired by a group of public-spirited Virginians who donated it to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1932. The park occupies nearly 800 acres of land in 10 widely separated parcels. Included are some 6 acres in Chimborazo Park on East Broad Street, site of Chimborazo Hospital during the Civil War.

A complete tour of the battlefields requires a 57-mile drive which is outlined on the map in this booklet. We suggest that you begin at the main Visitor Center in Chimborazo Park, 3215 East Broad Street, Richmond, where museum exhibits and an audio-visual program are available to enhance your appreciation of this battlefield area.

Markers, maps, and interpretive devices along the tour will help you to understand the military operations. You will see parts of the fields of combat, massive forts, and intricate field fortifications. Two houses on the battlefields have wartime associations—the Watt House (Gen. Fitz-John Porter’s headquarters) and the Garthright House (Union field hospital).

Richmond National Battlefield Park is administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. A superindendent, whose address is 3215 East Broad Street, Richmond, Va., is in immediate charge.

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1961 OF-588588

(PRICE LISTS OF NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PUBLICATIONS MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS, WASHINGTON 25, D.C.)

Roll book of 27th N. Y. Regiment punctured by Confederate bullet