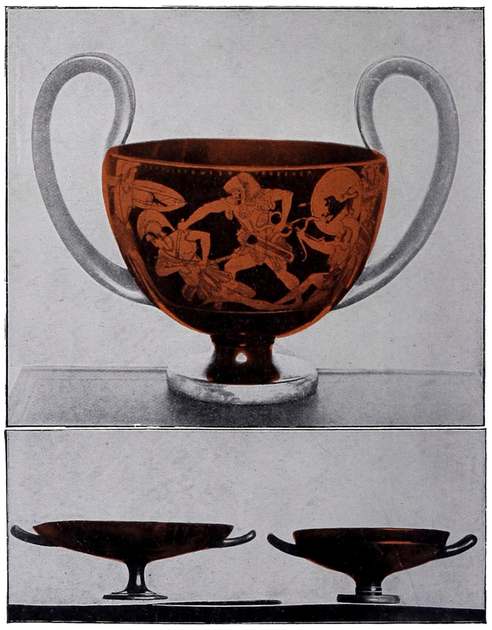

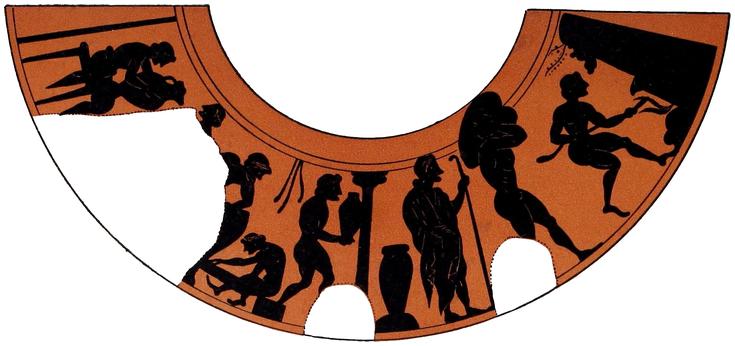

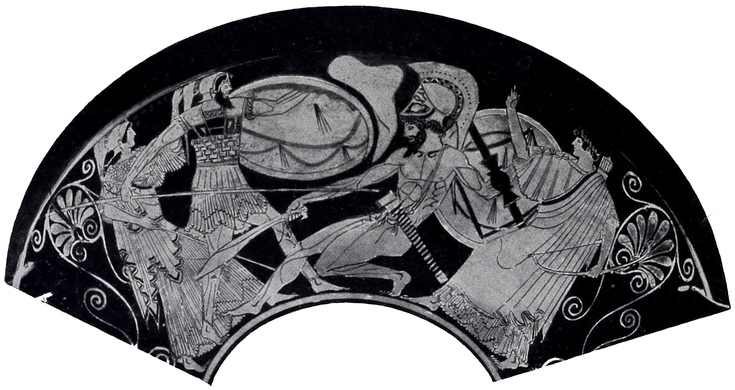

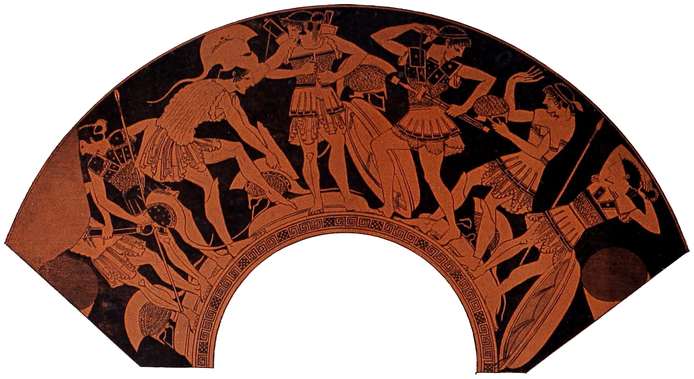

Fig. 1. KANTHAROS AND KYLIX (Cup).

By Douris. Brussels and Louvre Museums.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Douris and the Painters of Greek Vases

Author: Edmond Pottier

Release Date: December 27, 2019 [eBook #61034]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DOURIS AND THE PAINTERS OF GREEK VASES***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/dourispaintersof00pott |

Fig. 1. KANTHAROS AND KYLIX (Cup).

By Douris. Brussels and Louvre Museums.

DOURIS

AND THE PAINTERS

OF GREEK VASES

BY EDMOND POTTIER

MEMBRE DE L’INSTITUT

TRANSLATED BY

BETTINA KAHNWEILER

WITH A PREFACE BY

JANE ELLEN HARRISON

HON.D.LITT.DURHAM, HON.LL.D.ABERDEEN

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1909

DEDICATED

IN LOVE AND GRATITUDE TO

AUGUST LEWIS

The translator of M. Pottier’s monograph on Douris has kindly asked me to write, by way of preface, a few words on the relation of Greek vase-painting to Greek literature and to Greek mythology. I do this with the more pleasure because this relation has, I think, been somewhat seriously misunderstood, and M. Pottier’s delightful monograph which, thanks to Miss Kahnweiler, is now given to us in English form, should do much to clear away misconception and to set the matter before us in a light at once juster and more vivid.

First let us consider for a moment the relation between Greek art and Greek literature.

In classical matters we are all of us, scholars and students alike, bred up in a tradition that is literary. Our earliest contact with the Greek mind is through Greek poets, historians, philosophers. This is well, for these remain—all said—the supreme revelation. But this priority of literary contact begets, almost inevitably, avi certain confusion of thought. Bred as we are in a literary tradition, we come later to be confronted with other utterances of the Greek mind, for example graphic art—vase-painting. This we naturally seek to relate to our earlier and purely literary conceptions. What has come to us second we instinctively make subordinate, ancillary. Greek art, and especially what we call a “minor art,” such as vase-painting, is the “hand-maid” of Greek poetry, or, to drop metaphor, the function of Greek art, is, we think, to illustrate Greek literature. Public and publisher alike demand nowadays that books on Greek literature, on Greek mythology, even editions of Greek plays, should be “illustrated” from Greek art.

By illustration is meant translation, the transference with the minimum of alteration of an idea expressed in one art into the medium of another. Were it possible in a work of art to separate the idea expressed from the form in which it is expressed, such transference might be an eligible and even elegant pastime. But every one knows that such separation of idea and form is in art impossible. Translation of poetry from one language to another is precarious, a thing only to be attempted by a poet; translation from one art to another is a task sovii inherently barren that the Greek, till his decadence, left it, instinctively, unattempted.

Against the poison of this “illustration” theory M. Pottier’s monograph is the best antidote, and all students of the Greek mind will be grateful to Miss Kahnweiler for making his monograph more easily accessible. M. Pottier focuses our attention on the personal artist, a man not intent on “illustrating” another man’s work, but on producing works of art of his own. Douris uses sometimes the same material as Homer or Arktinos, but he shapes it to his own decorative ends; he draws his inspiration naturally and necessarily rather from graphic than from literary tradition.

Beneath the “illustration” fallacy there lurks, as regards mythology, another and a subtler misconception.

Until quite recent years mythology has been again to scholars and students alike, a thing of “mythological allusions,” a matter to be “looked up” with a view to the elucidation of obscure passages in Pindar or dramatic choruses. Even nowadays mythology remains, to many a well-furnished scholar, a sort of by-product, an elegant outgrowth of the Greek mind, a thing merely “poetical,” by which he meansviii having no touch with reality. Or, at best, if the scholar be himself a poet, he loves mythology without analysing it, he feels it as a dream that haunts, a thing that attends and allures him through the waste places of scholarship, more real and more abiding than any realism, a thing to him so intimate that he does not ask the why of it.

Thanks to the impact of another study, anthropology, we are awake now and look at mythology with other eyes. We know that mythology is not a last, lovely, literary flower, but a thing primitive, deep-seated, long antedating anything that can be called literature, not a separate “subject” at all, but rather a mode of thinking common at an early stage to all subjects. Mythology is not the outcome of an idle, vagrant fancy, but a necessary step in the evolution of human thought; a strenuous step taken by man towards knowledge, towards the fashioning and ordering of the world of mental conceptions. Mythology is the mother-earth out of which for the Greeks grow those stately, fruit-bearing trees, literature, art, history, philosophy. A Greek vase-painter does not “illustrate” mythology, he utters it in line and colour as the poet utters it in words and rhythm.

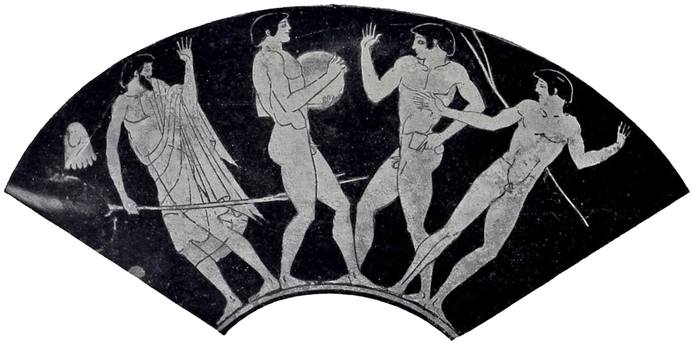

ix Take a simple instance from the work of Douris, the kylix in the Louvre, in the centre of which is painted Eos carrying the body of Memnon.

The mythologist, that is man in his early days of thinking, cannot conceive or name the abstract, empty “dawn.” The glow of morning is to him the print of unearthly yet human fingers. He images “dawn” as “Dawn,” in terms of humanity, that is of the one and only thing he inwardly felt and knew—himself. The dawn is for him a beautiful woman, and to complete her humanity, she is a mother. Literature, which is at first but story-telling, took up the tale, and knew that Eos the Dawn who rose in the East had a child of the East for her son, and mourned for him in his death, and carried him away for his burial.

The vase-painter is a mythologist too, and he takes a mythological story for his motive, but his art has other ends than that of the poet. He may have heard the story recited at a Panathenaic festival, just as he may have seen it painted on some Stoa or Lesche. But he does not illustrate it, does not translate from an alien art into his own. He takes the myth and lets his own art say what it and only it can say. He has seen in the human bodyx the vision of a heavenly pattern; he gives us the grace of a bending body, the poise of a flying foot, the swiftness of straight lines, the majesty and poignancy of limbs stark in death. That is all, and, surely, enough.

JANE ELLEN HARRISON.

xi

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | HOW DESIGNS ON VASES REPRESENT THE HISTORY OF GREEK PAINTING | 1 |

| II. | THE SOCIAL CONDITION OF A VASE PAINTER AT ATHENS | 9 |

| III. | THE WORKSHOP AND TOOLS OF DOURIS | 23 |

| IV. | HOW DOURIS WORKED | 30 |

| V. | THE WORK OF DOURIS | 43 |

| CONCLUSION | 80 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 87 | |

| INDEX | 89 | |

xiii

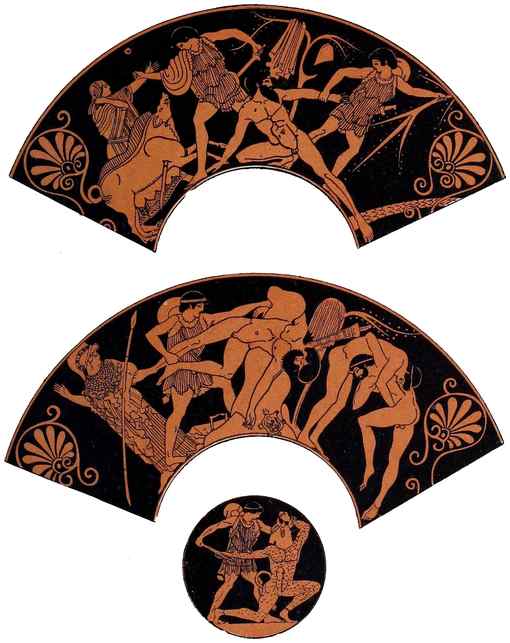

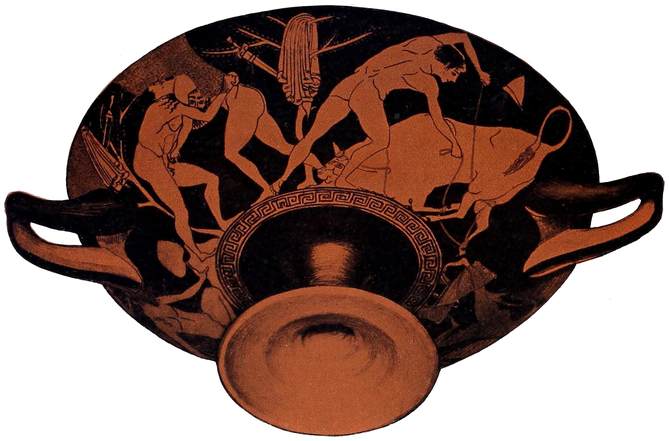

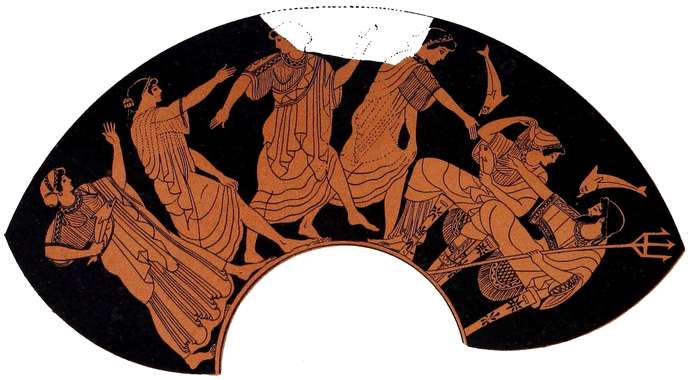

| Fig. | Page | |

| 1. | Kantharos and Kylix (drinking cups) by Douris. Brussels and Louvre Museums. Taken from Photographs | Frontispiece |

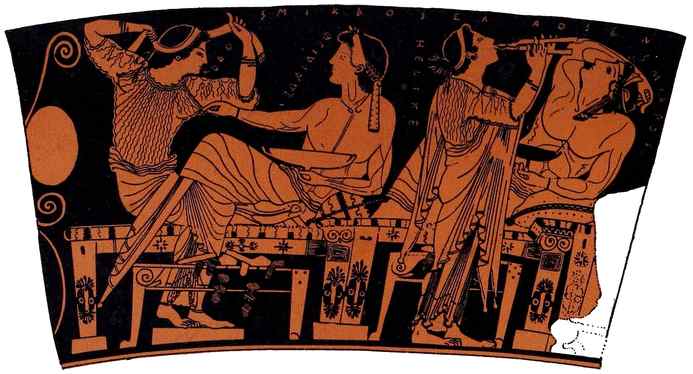

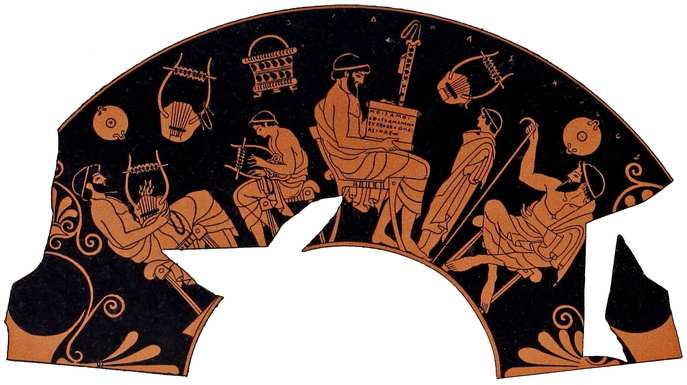

| 2. | Workshop of a Vase Painter (red figured hydria in Caputi Collection at Ruvo), from Blümner. Technologie und Terminolog. der Gewerbe und Künste, ii., p. 85, Fig. 15 | 4 |

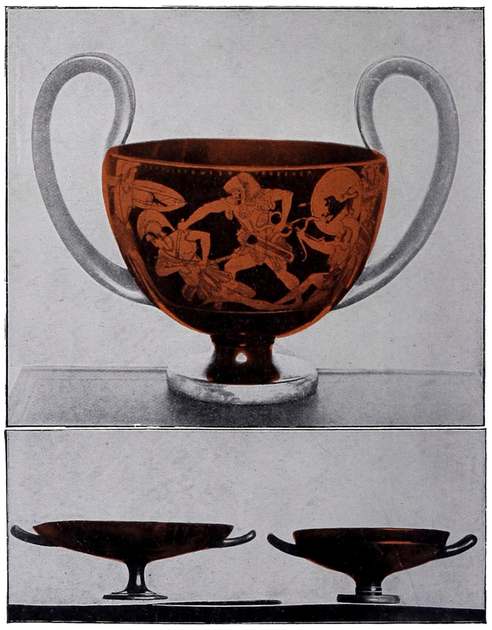

| 3. | The painter Smikros and his companions (red figured krater in the Brussels Museum), from Monuments et Mémoires de la Fondation Piot (article by C. Gaspari, ix., 1902, Pl. 2) | 8 |

| 4. | A Potter’s Workshop; modelling and baking of vases (black-figured hydria, Munich Museum), from Birch, “History of Ancient Pottery,” 1858, p. 249 | 12 |

| 5. | A display of Vases and a purchaser (red figured kylix painted by Phintias, Baltimore Museum). Hartwig’s Meisterschalen, Pl. 17 | 16 |

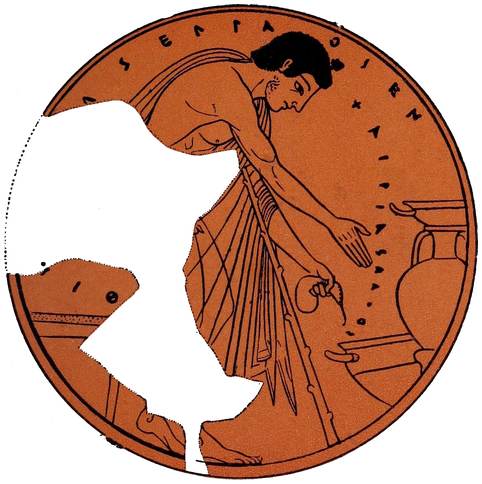

| 6. | Youths exercising in the Palæstra (red figured kylix by Douris, Louvre Museum), from an original Photograph | 20 |

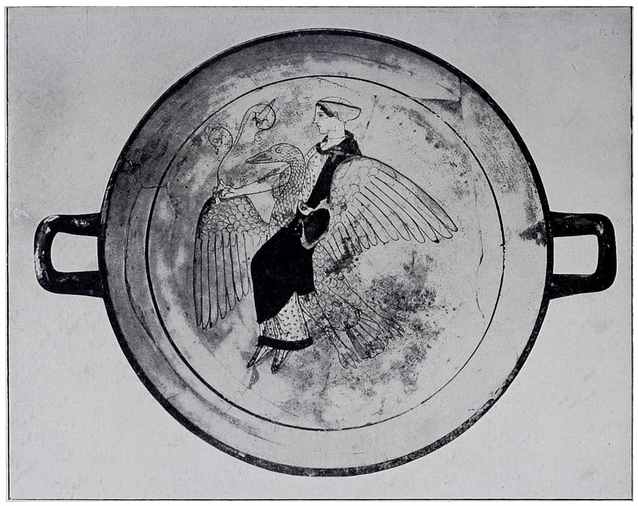

| 7. | Aphrodite upon her Swan (Polychrome on white background, British Museum), from A. Murray and A. Smith, “White Attic Vases,” Pl. 15 | 24 |

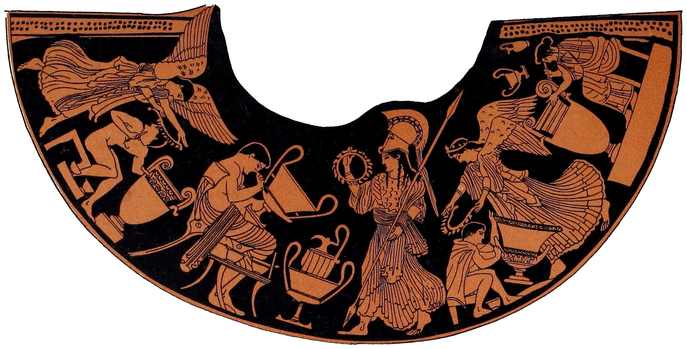

| 8. | Eos carrying Memnon, her dead son (red figured kylix by Douris, Louvre Museum), from an original Photograph | 28 |

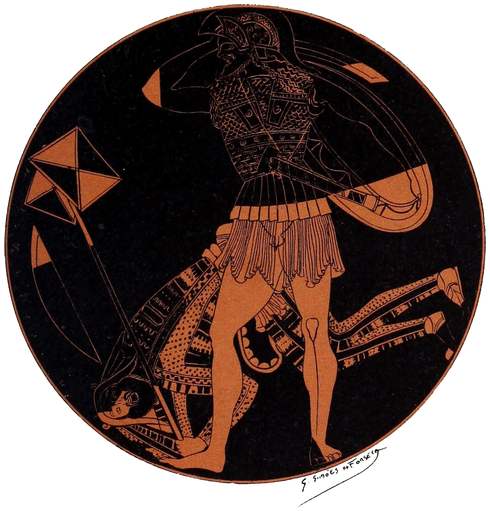

| 9. | Contest of Menelaos and Paris (exterior of preceding one), from an original Photograph | 32 |

| 10. | Contest of Ajax and Hector (exterior of preceding one), from an original Photograph | 36xiv |

| 11. | The Adventures of Theseus (red figured kylix by Douris, British Museum), from E. d’Eichthal et Th. Reinach Poèmes choisis de Bacchylide, p. 48 | 40 |

| 12. | Theseus and Kerkyon; Theseus and the Marathonian bull (reverse of red figured cup by the potter Euphronios, in the Louvre Museum) taken from Furtwängler & Reichhold Griechische Vasenmalerei, Pl. 5 | 44 |

| 13. | Nereids appealing to Nereus and Doris (red figured cup by Douris, Louvre Museum), taken from Wiener Vorlegeblätten, vii., Pl. 2 | 48 |

| 14. | Sileni playing and dancing (red figured vase by Douris, British Museum) Furtwängler & Reichhold Griechische Vasenmalerei, Pl. 48 | 52 |

| 15. | Hera and Iris attacked by Sileni (red figured cup by Brygos, British Museum), Furtwängler & Reichhold Griechische Vasenmalerei, Pl. 17 | 54 |

| 16. | Contest of Ajax and Ulysses; the voting of the Greek Chiefs (red figured cup by Douris, Vienna Museum), Furtwängler & Reichhold Griechische Vasenmalerei, Pl. 54 | 56 |

| 17. | Ulysses restoring the Arms of Achilles to Neoptolemos (interior of preceding one), Furtwängler & Reichhold Griechische Vasenmalerei, Pl. 54 | 60 |

| 18. | Achilles killing Troïlos (red figured cup by Euphronios, Perugia Museum) taken from Rayet et Collignon, Céramique Grecque, Fig. 70 | 64 |

| 19. | Soldiers arming (red figured cup by Douris, Vienna Museum), Furtwängler & Reichhold, Pl. 53 | 68 |

| 20. | Greek Hoplite and Persian Standard-bearer (red figured cup by Douris, Louvre Museum), Wiener Vorlegeblätten, vii., Pl. 3. Great surface indicates restoration | 70 |

| 21. | Seated Youth holding a Hare (red figured kylix by Douris, Louvre Museum), from an original Photograph | 72xv |

| 22. | Interior of a School (red figured kylix by Douris, Berlin Museum), from Monumenti dell’ Inst. Arch., ix., Pl. 54 | 76 |

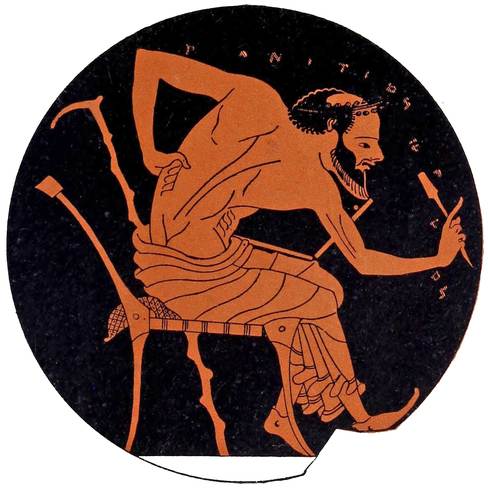

| 23. | A Schoolmaster. Berlin Museum, from Hartwig, Meisterschalen, Pl. 46 | 80 |

| 24. | Zeus carrying off a Woman (attributed to Douris, Louvre Museum), from an original Photograph | 84 |

| 25. | A Painter at Work (fragment, Boston Museum), Jahrbuch des Arch. Instituts, xiv., 1899, Pl. 4, Hartwig | 86 |

1

This book has not been written for the professional archæologist. While speaking of Douris, we propose to give the reading public an idea of the chief characteristics of Greek painting.

It may be asked why the title of this little book is not Polygnotos or Parrhasios. As we are treating of ancient painting, why not choose as a study one of these famous men, whose works give to the art of his time its distinctive character?

The answer is simple. Not a single painting is preserved by the masters who, with the sculptors Phidias, Polykleitos, Praxiteles, and Lysippos, made the ages of Pericles and2 Alexander illustrious. Not a fragment of their paintings nor a piece of their frescoes has escaped destruction. Unfortunate chance has thus kept the most glorious period of Greek painting hidden from our view. Recent discoveries in Mycenæ, Tiryns, Crete, and Melos have revealed astonishing works of the pre-Hellenic age, and they have restored to us frescoes contemporary with Minos and Agamemnon. And for more than a century the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum have made known all the details of the decoration of Roman houses at the time of Augustus and Titus. But between these two periods—separated by fifteen or twenty centuries—all is obscurity,—a dark gap which a few marble panels in the museum of Athens are quite insufficient to cover. These pale remnants of funereal monuments from the Kerameikos, frescoes painted on marble, reproduced the life and likeness of the departed.

Literature still remains. Pausanias, Pliny, Lucian, and others have enumerated and described the celebrated works of ancient painting, and indicated the chief characteristics of the great masters. In certain passages even the technique is mentioned and analysed. With the help of this literature we can, in a general3 way, trace the history of Greek painting, and it is chiefly from these records that such classic books have been written as Brunn’s Geschichte der Künstler and Woltmann’s Geschichte der Malerei. For gaining a thorough knowledge of the data of the subject, the great value of these books is unquestionable.

But there is no doubt that a history compiled from texts becomes excessively dry, even though illustrations are borrowed from Pompeii and Herculaneum. What impression would any one who had never seen a painting by Raphael or Michelangelo receive by merely reading about them?

Furthermore, many ancient authors, far from being accurate or full in their information, are hopelessly brief; often the subject of a painting and the name of its author are mentioned in but three words. Let us suppose that two thousand years hence our descendants should find a guide-book and read, “The Sacred Grove of the Muses, by Puvis de Chavannes.” What conclusions could they draw in regard to the composition of the painting or the talent of its author? Such is our position in regard to many works of antiquity. Even if, as is sometimes the case, the descriptions are full, as in a passage where Pausanias enumerates all the persons in4 the two frescoes of Polygnotos at Delphi, The Visit to Hades and The Capture of Troy, the same darkness still exists as to the placing of the figures, their expression, their attitude, and the technique of the colouring.

Thanks to the study devoted to painted vases, we are now able to get a better idea of and throw a little more light on the style and composition of Greek painting. M. Paul Girard’s book, La Peinture Antique is an instance. Nearly all the illustrations in the chapters devoted to classic Greece are taken from the decoration of vases. To return to a comparison made above. One who knew nothing of Raphael’s work, but who had seen some faïence of Urbino reproducing certain works of the time, would in every way be more capable than those who had not of understanding the master’s composition and his style. He would undoubtedly still lose many things. He never would realise the harmony of his colours or the loftiness and purity of his designs. This is, alas! what we must say, in comparing the painting of a Greek vase with the lost paintings of Polygnotos or Zeuxis. The reflection of a lost art is all that remains to us!

Fig. 2. THE WORKSHOP OF A VASE PAINTER.

Caputi Collection, Ruvo.

We should add, however, that the distinction between Greek manufacturers and their models5 must have been less marked than in later ages. Of this we cannot give material proof, but from certain details we arrive at this conclusion. On the one hand, the Attic craftsman was endowed, as rarely any one has been, with the art of design and the sense of style. On the other hand, the ancient fresco, particularly of the fifth century, was only drawing in flat colours, without shading or modelling. Hence, there did not exist the gulf which in modern times separates a reproduction due to mechanical means from a painting executed with all the fine shades and skilful distinctions of chiaro oscuro. In Greece, a painter of frescoes or a painter of vases was above all things a good draughtsman. Here is a common measure which reduces the distance between them.

In the absence of original paintings we must descend a step and have recourse to the vase industry, and thus discover dimly the nature of pictorial art in the best times of classic Greece.

But here another question arises. In treating of Greek ceramics, is the name of Douris the most important one among the many artists presenting themselves to our mind? He formed one of the Pleïades, who, between the expulsion of the tyrant Hippias (510 B.C.) and the Persian wars (490–479 B.C.), brought the manufacture of6 Athenian pottery to its culminating point. His rivals Euphronios and Brygos have, however, been considered more skilled or more inspired in their work. Why then choose Douris as the most representative type of Greek painting?

This is the reason. We know at present about one hundred names of manufacturers and painters of vases. Those who during the best period have left the greatest number of works are Euphronios, Douris, Hieron, and Brygos. Leaving aside simple fragments, and only counting pieces helpful for serious study, we possess of the first-named ten signed works, of the third twenty, of the fourth eight. Of Douris twenty-eight are known.

The greater number alone would justify our choice. But another and more important consideration may be added to the former. Manufacturers of vases have different trademarks for their ware. They trace their name with a paint-brush on the body of the vase, or else incise it in fine letters on the foot or handle. The mode in which their name occurs varies: “So-and-so made,” or else “So-and-so painted.” There can be no uncertainty as to the latter phrase; it refers to the artist who executed the paintings decorating the vase. But this term is far less frequent than the7 former, which has caused many discussions. “So-and-so made”? Is it a more elliptical way of implying the designer, or is it the potter who speaks in contrast to the painter and designer? Or, again, did the same man make the vase and then paint it? Is it the master, the overseer who directs the entire manufacture, and who, after the different processes of modelling, of decoration, and of baking have been executed under his direction and according to his plans, affixes to the ware of his house a sort of commercial trade-mark? All these opinions have been supported at different times. We cannot say that the subject has been fully elucidated. In consequence we run a great risk of mistake in saying that a painting is a certain potter’s workmanship, when the vase does not explicitly state who painted it.

The inevitable conclusion remains; to argue with certainty about painters of vases we can only trust one expression: “So-and-so painted.” In the most prominent group of potters of the fifth century, it is Douris who best fulfils all these conditions, and relieves us of all uncertainties on this subject. He is a craftsman, and can make a pot or have one made under his direction. The museum at Brussels8 possesses a kantharos which “Douris made” (Fig. 1). But he is above all a draughtsman and executes all his paintings himself, for the twenty-eight examples mentioned, including the kantharos at Brussels, bear the words, “Douris painted.” Even Euphronios, to whom Klein devoted an entire book, making this artist famous—and who to many represents the vase painter par excellence—only signed as draughtsman three or four vases, and as craftsman seven.

As potter and painter, Douris fulfils the necessary qualifications of a master-craftsman; above all as draughtsman and painter, he satisfies most fully our desire of finding in the decoration of painted vases a reflection of the great contemporary art. This is why the choice of his name seemed to us imperative.

Fig. 3. THE PAINTER SMIKROS AND HIS COMPANIONS.

Krater in the Brussels Museum.

9

A biography of Douris must not be expected. No classical writer has honoured one of these potters even so far as to mention his name. Ancient literature has only left some brief allusions to the craft, some inscriptions recalling their dedications in sanctuaries. The vases themselves and the inscriptions traced thereon form the clearest testimony we possess. Here again we must be guided by discretion and not drift into romance. A learned German assumes that Euthymides, a celebrated potter of the fifth century and a contemporary of Douris, must have died young, while his rival Euphronios, after a long career, died at an advanced age. He quite forgets that the number of signed vases to be attributed to any individual artist is liable to be diminished or increased by a chance discovery, and that we are still far from being able to survey at10 a glance the complete production of a manufacturer. Euthymides may have produced far more than Euphronios; we have, however, only recovered seven of his vases. An enquiry into the lives of vase painters must be confined to a consideration of the general conditions of their position. All inference as to special facts is necessarily conjectural and fictitious.

Modern historians have made known to us this important fact: trade in Athens, as in other Greek cities, was chiefly in the hands of those called “Metics,” that is to say, strangers living in the city and given certain political rights regulated by special laws. Athens possessed laws most favourable to the metics, and from the time of Solon, according to Plutarch, strangers crowded into this generous city, which offered such obvious advantages to settlers.

During the time of the Peloponnesian war (431 B.C.) the number of metics had increased to 96,000, as compared with 120,000 citizens—an enormous proportion. It is therefore to be supposed that many manufacturers at the beginning of the fifth century were aliens or descended from foreign families. This hypothesis is confirmed by the potters’ names, many11 of which are foreign: Skythes (the Scythian), Lydos (the Lydian), Amasis (name of an Egyptian Pharaoh of the sixth century), Kolchos (inhabitant of Colchis), Thrax (of Thrace), Sikanos and Sikelos (the Sicilian), Brygos (name of a Macedonian or Illyrian people), etc. Beside these, however, we meet with many purely Greek or Attic names—Klitias, Ergotimos, Nikosthenes, Epiktetos, Pamphaios, Euphronios, Hieron, Megakles, and others. In certain cases, the craftsman’s patronymic follows, as Kleomenes, son of Nikias; Euthymedes, son of Polios. This indicates a freeman and citizen of Athens. Once we even find the deme mentioned: Nikias, son of Hermokles, of the deme Anaphlystos. We here catch a glimpse of a society where the actual citizen associates freely with many naturalised aliens. It is probable that slaves or freedmen were also employed, as one may guess from the following nicknames: Paidikos (beautiful child), Smikros (the little one), Mys (the rat). Douris’ name does not appear to be Attic. It is always written Doris on vases, but we know that in those times the diphthong ou was simply expressed by o. The name Doris does not exist in the catalogue of men’s names which12 has come down to us, while the name Douris is well-known. It may have been of Ionian origin.

To resume, the Kerameikos of Athens formed a district by itself, a little world where all sorts of people belonging to different races and societies jostled one another. The master was the manager of the factory and a craftsman, capable of making a vase as well as painting it, designing the forms, the ornaments, and the subjects. His assistants, who were sometimes allowed the honour of signing, were employed under his direction in the shaping and decorating of pottery; even women took part in this work, as we see on a beautiful vase-painting (Fig. 2) to be described later. Lastly, there were the workmen engaged in working the clay, preparing the glaze and the colours, taking care of the ovens, moving materials, etc. Comparing the arrangements in a modern ceramic factory, one will find about the same conditions and these three grades of workers.

Fig. 4. A POTTER’S WORKSHOP. MODELLING AND BAKING OF VASES.

Hydria. Munich Museum.

We must naturally picture things in Greece on a modest scale: the enterprise conducted at less expense than nowadays, the capital smaller, and the staff reduced to those strictly required. Above all, it is necessary to remember13 that the division of labour was far less marked in ancient times than with us. The same man was capable of different tasks, he was employed according to his ability and intelligence. There was nothing of the mechanical spirit, which nowadays has passed into the man from the machine, and, for the sake of greater speed and precision, isolates a workman in a corner of the factory without teaching him anything else. Undoubtedly a social hierarchy existed and weighed heavily upon the individual; to be citizen, metic, or slave implied profoundly different conditions of life, which raised more formidable barriers between classes than with us. But in the exercise of art or industry the life of the ancients presents itself under a singularly democratic aspect. Their workmen shared their mental work far more than ours do, and were familiar with all the details of the craft. This it is which gives to the industrial art of the Greeks a marked distinction. No matter how modest the work, one feels a living intelligence therein. The history of vases is most suggestive in this respect. We never find the stiffness of mechanical labour, the monotony of copy repeated to satiety. All are not masterpieces—far from it. But not14 one is quite devoid of individuality, and the best proof that can be given is that two painted Greek vases exactly identical do not exist.

Whether Douris was metic or citizen, we may think of him as a craftsman, who by his knowledge and skill had acquired an important position in the town, and directed one of these flourishing establishments in the potters’ quarter, near the Dipylon Gate, and just at the entrance to the Necropolis. His ware helped to carry the fame of Attic taste into distant lands.

We know that the majority of Greek vases have been gathered from Etruscan tombs, where they formed the personal property of the dead after having been used by families at banquets and at religious ceremonies. Similar finds have been made in many other sites of the ancient world: in the islands of Sicily, Rhodes, Melos; on the coast of Africa, in Cyrenaica; in the Thracian Chersonese, even as far as the Crimea. But nowhere have the finds been richer than in Etruria; this was the favourite market for Attic ware during the sixth and the greater part of the fifth century.

After the disastrous war in Sicily, when communication with the Tyrrhenian Sea was severed, they turned to southern Italy, the15 Islands, Africa, and the Scythian colonies. The trade in vases was not limited to the home market, to the customers of Athens and the neighbourhood. The most important and most thriving part of the industry was the export into foreign countries. What we to-day term l’article de Paris scattered over all the world somewhat recalls the favour enjoyed by Attic productions in that age. Great profits must have been realised.

This trade was again combined with other important exports. It would be an error to consider the painted vase as a curio simply made for the pleasure of the eyes of the collector or artist, like the porcelain of China and of Japan to-day. The Greeks had no bric-à-brac. We may even say that there were no art amateurs or collectors. Utility was the only foundation of art: it formed its health and strength. We do not believe a statue was ever made, even in the fifth century, simply for the pleasure of creating a beautiful piece of work. Each art object had a practical purpose, and only existed by virtue of a want: offerings to the gods, consecrations after victories, household utensils, votive offerings at the altar and the tomb. It follows that industrial art was still more intimately16 connected with practical needs. The amphora, which appears as a speciality of Athens in the ceramic industry, contained the famous oil gathered in the plain—to-day still famous for its olive groves—or wine from Parnes. We know positively that the Panathenaic amphoræ given as prizes at the feasts in honour of Athene contained the savoury oil produced by the sacred plants of the goddess. Victors carried these to their homes as trophies. There is no reason to believe that other vases were treated differently. Why should the painted amphoræ, such as are found from the sixth century onwards in great numbers in Etruscan tombs, be sent forth empty from the workshops of Corinth, Chalkis, or Athens? They certainly once contained a product prized by the inhabitants of Caere and Volsinii more than the beauty of the painting on their exterior. In consequence of this beautiful decoration, which was a sort of trade-mark of Greek produce, rich families in Italy ordered entire “table services” from Athens for special use at banquets and religious festivals. They not only comprised receptacles for oil and wine—amphoræ, krateres, lekythoi, decanters for wine as the oinochoai, holders of water as the hydria—but also vases for drinking, such as the kylix, the kantharos, and the17 skyphos, and even plates and platters. From the fifth century onwards Athens had succeeded in destroying all competition. She had become the unique centre of this trade. The character of the art then obtained decisive importance.

Fig. 5. A DISPLAY OF VASES AND A PURCHASER.

Kylix by Phintias. Baltimore Museum.

The manufacture of the kylix—which was essentially the instrument of joy and gaiety, passing at banquets from hand to hand and admired by every one as it passed—received an impetus until then unknown.

Hence it was in consequence of being in close connection with the export trade and with the two other great industries of wine and oil that the ceramic art of Athens developed so extraordinarily. The manufacturers must frequently have made large fortunes. Historians tell us that the great fortunes in Athens were in the hands of the metics. It is not astonishing to hear of rich offerings being made on the Acropolis by manufacturers, some of whom were potters. On the pedestal of an offering we read the name of the potter Euphronios. A votive stele, in a style of delicate archaism, represents in bas-relief a manufacturer of vases seated, holding two drinking cups in one hand. Unfortunately a great part of the inscription is effaced, but one can still distinguish the end of a name “IOS” which might be Euphronios.18 The style of the sculpture and the accepted date of the ceramist would agree.

The most beautiful archaic statue found on the Acropolis is signed by one of the greatest sculptors of the fourth century, Antenor, and bears a dedication made by a certain Nearchos, who might be a maker of black-figured vases—one of which is preserved. This identification is unfortunately not certain, but is admitted by several archæologists, and implies nothing improbable. If one could definitely prove that the potter Nearchos had ordered, of a famous sculptor, an important work for an offering to the goddess Athene as a tithe of his gains, we should possess most important evidence as to the social and pecuniary condition of craftsmen.

Another curious record of the mode of life led by certain potters is given on a vase in the Museum at Brussels. A painter has painted his own portrait in the features of a young man at a banquet leaning on a couch, feasting in the gay company of friends and hetairai (Fig. 3). He is a contemporary of Douris named Smikros. One day, his purse being well filled in consequence of good orders, he and some companions of the studio indulged in the pleasures the city yielded.

If, by such information we may consider the19 pecuniary position of potters as fairly good, shall we conclude that their education was equal to that of the best Athenian society? Here it may be well to enter a protest against the commonly accepted opinion. Vase painters are usually credited with qualities of originality amounting to positive genius. The merit of the composition and of the choice of subject, the skill in placing the figures, the invention of attitude and movement, are all attributed to them. Hartwig, an author who has closely studied the Greek drinking cups of the fifth century, goes so far in his admiration as to reject as fanciful any connection between the works of this industry and the great works of contemporary art. He grants that vase painters copy one another, and that they borrow mutually subjects for designs and even persons. But he maintains that their province remains indisputedly theirs, and one need not look for copies from celebrated works in their art.

This opinion appears, like many others, to contain a truth and an error. It is quite true, that to look for a commonplace reproduction of great art upon painted vases would be useless. Many subjects are strictly designed for the express purpose of the vase, for the form of its surface, and are drawn from scenes20 of everyday life which were constantly under the draughtsman’s eyes, scenes of the palæstra, of banquets, military armaments, processions of cavalry, etc. Who could imagine a Greek draughtsman not copying Nature?

But, on the other hand, how can one think of an artisan as skilled as an Athenian ceramist, who could remain indifferent to the lessons of the great masters? Would not his eyes and brain be filled with the works of art which made all public buildings and sanctuaries museums in the open air? And in that case, what strange rule would forbid him to borrow many of the subjects and persons from these superior models? These would be abstracts, free compositions, adaptations, but nevertheless a borrowing.

Fig. 6. YOUTHS EXERCISING IN THE PALÆSTRA.

Kylix by Douris. Louvre Museum.

Furthermore, what we have just said of vase manufacturers places them in a popular class whose members did not shine by education. Merchants of free status, metics, freedmen or slaves could not form a society comparable to the one in which lived a Polygnotos or a Phidias. Isocrates says scornfully: “Who would dare compare Phidias to a maker of terracottas, or Zeuxis and Parrhasios to a painter of votive offerings?” He would undoubtedly have said the same of21 vase painters. We affirm, in fact, that many of these workers were quite illiterate; some were content simply to trace sham letters or letters in juxtaposition, without any meaning, in the place of the usual inscription. Many made gross mistakes, or mixed the dialect of their own country with that of Athens. Some did not even know how to spell the name of the potter for whom they were working, but wrote it in three or four different ways. These little facts help to illustrate the inferior condition of this society. To look here for great artists, philosophers or thinkers, rivals of Pindar and Æschylus, of Phidias and Polygnotos, would be contrary to all likelihood. If Euphronios, Douris or Brygos had genius, it was entirely in their province as skilled draughtsmen, guided and influenced by beautiful models, besides being business men and prudent merchants. The idea of raising such men to the height of creators and inventors would certainly have greatly astonished the Athenians.

To sum up, Nature and living truth—the works of great masters and the teachings of the past—these form the double source from which all artists, at all times, have drawn. It would seem difficult to exclude from one22 or the other the painters of Greek vases. On the contrary, in studying them we feel, although their social position is humble, and their private education mediocre, that they are peculiarly great, inasmuch as their artistic sense is always alert, always emulous of competitors or works of art about them, and, finally, great in that dominant quality which the Greek carries within him—a keen sensitiveness to all that is beautiful in life. As artisans, craftsmen, merchants and metics, they move in a lower sphere in their city; but nothing shows more clearly the power of the environment than seeing in Athens, which had become the spiritual centre of Greece, the working man’s world raising itself without effort from its dead level to the intellectual life of the higher classes: a phenomenon all the more remarkable as it occurred in an ancient society, that is to say, in an era when the social barriers were inflexibly rigid. May modern democracies be inspired by this example and understand that the education of the masses comes from the highly-gifted, and the masses will never be high-minded when those whom fortune has placed above them are worthless.

23

We must regard Douris from two points of view: the craftsman and the artist.

Let us first see what his workshop was like. Again, all the documents we possess are the vases themselves, or terracotta tablets which served as votive offerings. We see upon them workmen in the act of turning or painting pots, lighted ovens, pottery exposed for sale, etc. Upon a black-figured hydria at Munich (Fig. 4) we see such an establishment divided into two parts: to the left is the workshop where the turning, shaping and polishing of vases takes place; to the right, under the supervision of an aged man, who apparently is the master, are other workmen carrying finished pots to dry and bake them. In the extreme corner is the high oven decorated with a Silenus mask. Here, a vase from Ruvo (Fig. 2) takes us to a painter’s studio. Three painters, each grasping a brush, are decorating the body and24 neck of two krateres and one kantharos, while other vases on the ground are awaiting their turn. To the right, on a platform, a woman is painting the handle of a larger krater; above her some small pots are leaning against the wall. The composition is ingeniously completed by the appearance of two Victories and Athene armed with helmet and lance, who solemnly crown the workmen bending over their work—a poetic symbol to glorify the fame of Athenian industry.

The act of painting is illustrated upon some vase fragments, where we see the artist working with a very finely-pointed brush (Fig. 25). Lastly, some Corinthian platters show us workmen turning vases and watching the baking, and the kiln filled with piles of pottery. One even represents a merchant ship with a cargo of pottery, oinochoai or small perfume bottles, destined for some land across the sea. We will mention one other kylix by the painter Phintias, upon which are displayed a potter’s wares. A number of vases are placed on the ground, and a youth with a purse in his hand is stooping in the act of choosing his purchase (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7. APHRODITE UPON HER SWAN.

White background. British Museum.

All these scenes are small genre pictures like The Barbers or The Lace Makers of Holland25 and Flanders in the seventeenth century. They teach us the chief characteristics of the ceramic art.

An establishment of this kind implies several buildings. The vase turners or makers would be in a separate room from the painters. One or more ovens would be required in a court, with a shed for the storage of raw materials, and for kneading and refining the clay. Lastly, we must assume that there were some rooms for warehousing and a sale-room adjoining the factory, in addition to rooms for the masters and night-watchmen. No matter how modest the staff, it would amount to fifteen or twenty persons, counting not only those in charge of the factory, but labourers and stokers. Upon the hydria at Munich (Fig. 4), in a painting necessarily restricted, we can count eight persons. Upon the vase from Ruvo (Fig. 2) the studio contains four workers—three men and one woman—all painting. To obtain a correct idea of the staff one must at least treble this number.

Hence a potter like Douris must have superintended a factory representing a commercial enterprise of some importance. We must not think of an artist, who, in his solitary studio, at his leisure and according to his inspiration,26 sketches subjects or forms for vases, and leaves the execution to others. We must not forget it is an industry. This practical purpose must profoundly influence one’s opinions as to the nature of the potter’s studies, his manner of composing, and the profit he expects from his enterprise.

We will not discuss points of technique which demand too detailed an enquiry, and would raise questions not yet solved. Let us think of the materials as gathered in the hands of the craftsman: clay carefully chosen and refined, colours for glazing and retouching, lustres intended to brighten the natural colour of the clay, and the black for the design, wheels and moulds, rules and compass, sharp points for sketching, brushes of all kinds, etc.

The most commonly used and most valuable ingredient is the black glaze, the composition of which is still unknown; its basis is oxide of iron. It is used for drawings on red clay, to trace features, persons, accessories and decorations, and to cover the background. It is to the Greek what Indian ink is to the draughtsman of Japan. In baking, it takes on a warm, velvety tone, sometimes a little olive, sometimes it becomes in the flames a little yellow or red. It is brightened by a27 brilliant lustre which frequently produces the effect of a mirror, but it never has the cold or waxy tone which disfigures modern imitations of antique vases. It is thick and rich, and forms, after drying, a slight prominence perceptible to the finger. Lastly, it is indestructible, even by acids, and does not change with time, unless the surface of the clay beneath it has been touched by damp, in which case it flakes off.

The invention of this black was one of the most beautiful discoveries in ancient industry. If we could only discover its formula it would still be of the greatest importance. It was in use from the time of the Mycenæan age, that is to say, more than a thousand years before our era; eventually potters brought it to perfection, increasing its delicacy, thickness and brilliancy. About the time of Douris it had reached its perfection and retained its excellence until the end of the fifth century. After the capture of Athens and the ruin of the potters’ workshops, the recipe was lost or the manufacture of it became neglected, for vases of the fourth century, found in Bœotia and in Southern Italy, show a great deterioration in this respect.

Next to the black, his brush is of the28 greatest importance to the Athenian artist. Its nature has been much discussed. In some of the illustrations cited, we see it in the hands of workmen while drawing (Figs. 2 and 25). It consists of a thin handle, doubtless of wood, to which is joined a long and thin point. Some suppose it to be the barbule of a bird’s feather; the feathers of the woodcock are particularly suitable for very delicate lines. In the opinion of others it is merely a hog’s bristle. The brushes vary in thickness according to the number and stoutness of the bristles employed.

The Greeks must have been able to paint with one single bristle, a method requiring great patience and special skill in loading the brush with paint and guiding it on the clay; but in this manner particularly delicate lines of even strength from end to end can be obtained. Experiments have been made with ordinary paint, proving this conclusively. Of course the painter must have had thicker brushes at his disposal with which to trace heavier outlines. The background had to be put in with heavy and broad brushes. But the fine brush is the tool above all others with which the Greek draughtsman accomplished wonderful feats, placing lines of extraordinary delicacy side by29 side, or throwing out a line at a single stroke, the impeccable straightness of which delights and surprises the eye. We have reason to believe that it was not a tool for craftsmen only. Painters of frescoes and large paintings had the same difficulties to contend with, if we are to give credence to an anecdote by Pliny: for Apelles and Protogenes competed who should draw the most perfect and finest line.

30

Fig. 8. EOS CARRYING MEMNON, HER DEAD SON.

Kylix by Douris. Louvre Museum.

Let us now watch the craftsman at work. We have said that Douris was a potter, but that usually he left to others the care of making vases according to well-known models, and reserved to himself the task of decoration. In what then does his character of painter consist?

First he must decide on the subject. The Greeks tried, as much as possible, to adapt the design to the purpose of the vase. An amphora or a krater would not usually have the same design as a kylix. There were no rules on the subject, and the utmost liberty was given the artist. Nevertheless, we notice that grave subjects and personages in attitudes of repose are given the preference on large vases, which had stable bases and were rarely moved, as harmonizing best with their broad surface and vertical lines. Animated or everyday subjects are better adapted to the horizontal31 sides of a kylix, which circulated freely in the hands of guests.

For the same reason, we may say that the painting of large vases remained essentially conservative, more attached to ancient methods and subjects, while the painting of the kylix constantly called forth new ideas: hence its great importance in the fifth century.

Certain archæologists claim to have discovered two distinct branches in the industry—but that is an error. The same distinguished artists produced the large krater and the kylix, as for example Euphronios. But it would be more correct to distinguish two schools side by side, and those artists who by preference decorated the kylix were more “progressive.” Douris is of this number, if not in style, at least in the choice of his subjects. He tries to create new designs; he draws from daily life, banquet scenes, dancing scenes, scenes from the palæstra (Fig. 6), amorous scenes—well adapted for a drinking cup. On the other hand, if he approaches heroic or mythical compositions, he makes use of the opportunity to draw beautiful bodies in motion, rape or battle episodes: The Nereids flying from Peleus (Fig. 13); Theseus killing the Minotaur and Attic robbers (Fig. 11); or the battles of32 heroes in Homer, as those of Menelaos and Paris or Ajax and Hector (Figs. 9 and 10). At other times, we find allusions to recent glorious events which had taken place in Greece, a Greek soldier striking down a Persian (Fig. 20), Hoplites and Asiatic archers at close quarters. He belonged to that group of artists who are always looking for action, for the new and the modern.

After what originals did the painter compose? We are quite ignorant here, and cannot specify without falling into fiction and hypothesis. Were there sketch books, representing the individual observations of the artist, taken from Nature or from great contemporary works? Or did πίνακες, tablets of wood or panels of terracotta, serve for preliminary sketches? Did a painter, as it were, design a “model” which he transferred to clay or gave to his workmen as a theme to work upon? All these questions remain unanswered. One is forced to surmise that the master signed only works on which he himself had worked, those which he designed and circulated as his latest productions, the editio princeps, so to speak, inscribed with his signature. But when a subject once composed was repeated in the workshop, copied with slight variations by33 workmen, the pottery, no matter what its commercial value, was no longer entitled to this personal certificate.

Fig. 9. CONTEST OF MENELAOS AND PARIS.

Exterior of preceding Cup.

Subjects thus composed with free repetition must be very numerous, for there is, as it were, a strong family likeness among many of them: battle scenes, banquets, gatherings of youths, games in the palæstra. Another important fact, must be stated, no obstacle was placed against plagiarism in ancient times; on the contrary, it was the spirit and essence of industrial art. We have proof of this in the terracottas as well as in the vases. Every one copies or imitates his neighbour. There is no copyright or patent for artistic property, an idea which has become the subject of legislation only in modern times. Considering the communistic way in which these Greek craftsmen lived, at a time when production was so intense, and the personal reputation of a potter might prove so great a factor in his fortune, we can readily understand how any man may have been led to protect himself against plagiarism by means of a signature which authenticated a production. A krater by Euphronios, a kylix by Douris or Brygos, might be particularly sought after by certain customers in Greece and Etruria. Why should they not be assured34 that they had in their hands an original work of a great master, and not a copy made by workmen or competitors? Have we not clocks signed by Boulle, and chests of drawers by Riesener, which are thus distinguished from similar objects, sometimes very beautiful, but which, without a trade-mark, do not represent original work?

Such then is the sense in which we should understand the signature of a vase by Douris. He sought, devised and composed the design. And even more, his own hands carried out the painting.

Let us now reflect upon the material side of the painter’s trade.

The artist begins with a simple sketch made by means of a hard point, it may simply be the sharpened end of a bit of wood, which scratches the unbaked clay, leaving decided traces after the final painting, baking and glazing. There is hardly a beautiful vase of this period, signed or not, which does not show these traces. This sketch sufficiently proves the absolute independence of the worker in regard to his model, and contradicts the opinion of those who maintain that the transfer was made with compasses. On the contrary, one feels how free the work is, and that the arrangement35 was invented entirely to suit the object decorated. And what enables us to follow the method of sketching still more closely, is the fact that the stroke of the brush, coming after, has not always exactly followed its lines. There have been alterations at the last moment, a lowered arm has been raised, a foot advanced, etc. It is impossible to doubt the spontaneous character, in some respects the improvisation of the design. It is, besides, rare to outline completely every person in a sketch. Frequently the outlines of one or two, with their chief characteristics, are drawn, and these determine the rest.

When the sketch is finished, the painter begins to put in his colour. He first takes a broad brush and rapidly indicates in black the outlines of the figures which compose his picture: this broad stroke of the brush charged with more colour and forming a projection round the figures can be easily distinguished. Next come the fine brushes, composed of only one bristle, giving in accurate and precise strokes the chief lines of the bodies and the folds of the garments; others, a little heavier, are used to indicate the hair, the beard, ornaments on the garments, etc. The black may be used in a variety of tones. By diluting it a more fluid36 matter was obtained, rather grey, which was frequently used for the under sides of objects, for rendering muscular details, the wavy folds in drapery, locks of hair, etc. Usually this diluted black would turn yellow in the baking. An unobtrusive polychrome is the result which the painters used with ingenuity; they were thus able to produce blonde hair or slightly golden folds of garments.

We have already stated that, in order to carry out these very fine lines, the artist probably held his brush firmly, not only with the tips of his fingers, but with closed hand as the Japanese painters still do (Figs. 2 and 25). He must move slowly and firmly in tracing these fine lines. Constantly obliged to take fresh colour, he sometimes had to break a line two or three times; but these joinings are only visible with a magnifying glass. It is said that it was impossible to make any correction of the stroke, and that the faultless execution of the lines proves the wonderful skill of the Greeks. We believe this to be an error. A wet sponge probably sufficed to remove any drawings or parts of them from the clay, and when it was dry the artist could begin work again. It was a question of patience and skill. It is because correction37 was so easy, that the results attained are usually perfect.

Fig. 10. CONTEST OF AJAX AND HECTOR.

Exterior of preceding Cup.

The painting finished, the pot was handed over to a workman to fill in the background between the figures with black as well as the foot and the edges of the handles.

After the black had dried, the pot was returned to the artist’s hands to be retouched with colour. In the sixth century, in the black-figured style, many colours were used, as violet-red and white. At the time of Douris, the red figured vases displayed very few complementary colours. Great simplicity characterized the taste of the times. A few red lines sufficed to indicate fillets tied in the hair, belts holding swords, the reins of horses, etc. Red was likewise used to trace inscriptions or the signature of the artist (Fig. 8). Others preferred to inscribe it in black on the foot of handle (Fig. 15). Others again incised it with a style in the thick colour. White only returns again to favour after the Persian wars. About the time of Douris, in the workshop of one of his rivals—Brygos—who may have been a little younger, attempts were made to heighten the effect of the red figures by a little gilding cautiously placed on the outlines of the armour, helmets and vases38 for libations. It is a return to the rich polychromy, which later continues to develop, and ends in those pretty little gilt vases devoted to scenes of child life, beloved by Attic customers towards the end of the fifth century. As far as we know, Douris does not seem to have taken part in the manufacture of the beautiful drinking cups with a white background and fresco tones of brown, red and violet, with which the workshops of Euphronios and his successors were busy (Fig. 7). He adheres to the classical method of figures left in the red clay, and only retouched by a few wine-coloured lines. It may be said that he is not a colourist. To his eyes, as to those of Ingres, drawing is the very foundation of the art.

When the drawings were finished, his chief task was done; but his position as manufacturer did not permit him to remain indifferent to the rest. He had to carry his painted pottery to the drying place, and, after the required time, to have it baked. This is a very delicate part of the manufacture of vases, on which its success greatly depends. Ancient ovens were probably very imperfect. There are many examples of oxidization by contact with the flame, which improperly reddens the side of39 a vase or turns half a figure orange. The supports on which vases were placed, while drying, sometimes left round marks. In one known instance, in consequence of two freshly painted vases touching one another, the hoofs of a horse have become impressed upon the face of a youth.

Defects in the material were more liable then than now to expose the ceramist to breakage and various accidents, which at all times have been the despair of the manufacturer, and which an Homeric singer already ascribed to special demons, “Syntrips, Smaragos, Asbetos, Sabaktes, Omodamos, gods fatal to the furnace.” We have already described a kiln adorned with a head of Silenus, a prophylactic fetish, destined to cast out evil influences (Fig. 4).

At last the pottery is taken out of the oven. The master can contemplate his work, test the delicacy of its sides, examine the fusion of the colours, study the change of tone in the baking. Other workmen come to immerse the vases in a prepared bath, which will glaze the entire visible surface, brighten the red of the clay, the background and all the black lines, but will leave the retouching dull. We are quite ignorant of the ingredients of the bath which so thoroughly accomplished all this40 and gave the pottery its splendour. We only know that a red precipitate was formed, traces of which are frequently visible under the foot and upon the clay which had remained uncovered. Among vases of the decline, this red overruns the entire drawing and gives an unpleasant appearance to the whole; in this case, as with the black, either the recipe of the glaze had been lost, or else the work was badly executed. Possibly a dry rubbing with leather or some other substance added finish to the glaze.

We must not even yet regard the potter’s work as finished. He had to superintend the sale, attract customers, confer with shipowners in regard to the export. Nor was advertising unknown to the ancients. It adopted many devices. Some potters contrived to paint on the vase subjects or inscriptions alluding to the products therein. There are scenes of wine and oil sales, with sentences, praising the merchandise or the honesty of the merchant. There are incentives to the pleasure of drinking, friendly greetings and wishes of good health to him who will use the kylix or kantharos. Even the details of the potter’s trade have served as matter for representation, to recall to the customer the fame of Attic41 workshops. The prettiest allegory is the one we mentioned above, where we saw Athene accompanied by two little Victories entering a workshop of painters and placing crowns on the heads of the workmen (Fig. 2).

Fig. 11. THE ADVENTURES OF THESEUS.

By Douris. British Museum.

But the means most frequently adopted to attract buyers was to inscribe on the body of a vase the name of some young man of distinguished family in Athens, known either for his beauty or his fortune, and in this way to gain the good-will of a rich customer, who would bring the patronage of all his family and friends. We have a large number of such inscriptions wherein the manufacturer invokes “the handsome Leagros,” “the handsome Glaukon,” or “the handsome Megakles,” etc., and we recognize in these names well-known members of the Athenian aristocracy (Figs. 5, 7, 8).

It will be remembered that the Italian potters of the sixteenth century put into circulation coppe amatorie, bearing portraits of beautiful women, surrounded by inscriptions celebrating Lucrezia diva or “the fair Camilla.” This is a similar idea.

Lastly, we have one example of a personal advertisement in rather an aggressive form, coming from Euthymides, a contemporary and42 rival of Euphronios. Upon an amphora in the Museum at Munich, the boastful craftsman has written this defiant apostrophe: “Euphronios has never done so well!”

These minute details enable us to penetrate into the material life of the workshop. We catch a glimpse of the greedy struggles for gain, the ambitions and rivalries involved in all commercial enterprise. It is the seamy side of this beautiful art, which to-day appears to us so pure and free from all material considerations. As in all human efforts, there were undoubtedly in reality many competing interests, many cruel cares, much deceit and hatred. But time has done its work; has thrown a veil over the mean and petty things in life, and only allowed those to survive which are truly sane and useful. Let us rejoice in not knowing whether Douris was a successful business man, whether he honestly made a fortune, or whether he died miserably in debt. That which remains of his work is the spiritual, the true and fruitful part of his life. His drawings teach us what he was, not as an individual, but as an artist, as a member of the great Athenian family, and this it is which interests us above all.

43

We will only consider here the works signed by Douris, and leave aside a considerable number of anonymous vases attributed to him. We only wish to argue from indisputable records. The number consists of twenty-six drinking cups, one kantharos, and one vase for cooling wine, forming in all about eighty paintings, which can be divided into three distinct groups:

1. Mythical and heroic subjects, adventures of gods and heroes.

2. Martial subjects, scenes of arming and battle.

3. Subjects of everyday life, banquets, conversations and exercises in the palæstra.

It would, no doubt, be interesting to study these subjects chronologically, and to follow step by step the career of the artist; but we could not place much confidence in a detailed enumeration of dates. We will select the first group as most clear and precise. This will not44 prevent our examining the numerous and diverse styles through which the talent of Douris passed. On the whole, we may say there were two chief periods in his style: the one, while he adhered to ancient traditions, and his drawings remained stiff and archaic; the other, when his brush became flexible to a remarkable degree, and when he began to create. It is the story of many artists, both ancient and modern.

The kylix of Eos and Memnon (Figs. 8, 9, 10), well known to visitors of the Louvre, is not only the oldest but the one which best illustrates the first period of Douris, and deserves the closest attention from lovers of art. It is a masterpiece of Greek ceramic art, at a time when the painting of red figures, while still retaining the stiff, archaic forms, finds means to move the feelings by purity of line and a deep sense of life. The vase, by the potter Kalliades, in itself reveals an old shape (Fig. 1 right) with the foot short and squat, the sides heavy, a deep bowl and short handles, following the models of Nikosthenes and Pamphaios of the sixth century. Later Douris made a kylix of far more graceful outline, with a shallower45 bowl, a higher stem made slender in the middle, and lighter handles, such as one sees in the workshops of Euphronios, Hieron and Brygos (Fig. 1 left). On this kylix there are a great number of inscriptions: nearly every person is designated by name. Besides the signatures of the potter and painter we can read the name of the handsome Hermogenes (Fig. 8), and with it a fragment of a phrase, the meaning of which remains doubtful. Seventeen or eighteen words in all are scattered in fine red letters over the inner surface and the reverse of the cup. This profusion of writing is in itself archaic; men were communicative in early times, and delighted in labelling their figures like our old illuminators of the Middle Ages. More recent works of Douris have lost this useless mode of expression. Painting is its own interpreter, and has no further need of this awkward assistance.

Fig. 12. THESEUS AND KERKYON,

AND

THE STRUGGLE WITH THE MARATHONIAN BULL.

Kylix by Euphronios. Louvre Museum.

The composition is synthetic. It contains three events in the Trojan war. On the reverse are the combats of Menelaos and Paris, Ajax and Hector; on the inner side the Ethiopian King Memnon lies dead in the arms of his mother, the goddess Eos (the Dawn). Some archæologists who have studied these paintings have tried to find here a strong and learned unity, a kind of drama in three acts, even at46 the expense of the inscriptions. Brunn even maintained that the latter were faulty, as he conceived therein an Achilleid, celebrating three different feats of the great hero. Others have refused to see any reference to the Epics, and have noted the differences which distinguished the text of Homer from these paintings. For instance, Douris has placed behind Menelaos the goddess Aphrodite, protectress of Troy, which seems inconsistent; behind Paris we see Artemis carrying her bow; behind Ajax is the goddess Athene. These divinities do not figure in the Homeric account. As regards the death of Memnon, it appears to belong to an epic by another cyclic poet, Arktinos of Miletos. It is the imagination of the poet that collected at random, as it were, these scattered subjects, and united them according to his fancy.

The opinion we hold amid these conflicting views will be more easily understood by reference to the chapters on the social and mental conditions of the Athenian potters. To suppose them to have conceived themes of deep meaning, elaborated like an ode of Pindar or a chorus of Sophocles with strophe, antistrophe and epode, seems most unlikely; and if, in order to gain good results, the inscriptions must be changed, we do not hesitate to reject47 such a procedure as contrary to all scientific method. Who can believe that these profound thinkers were so stupid as not to write correct inscriptions? On the other hand, we know enough of the art of the period, of the advance made in design, to expect a certain unity in the whole. It is the spirit of the entire school to unite the different parts of the vase by subjects closely connected, or at least related. In the present case we believe the Trojan war to be the great theme uniting the three paintings. This was the most cherished subject, even with the people. We must remember that a painter of vases had nothing in common with a modern designer who has a text to illustrate before his eyes. It is hardly likely that manuscripts of Homer or Arktinos were found on the work-benches of the Kerameikos. For these craftsmen, memory or the remembrance of some recitation at the Panathenaic festivals had to take the place of the book.

In consequence, the chief episode must have made a decided impression on the mind, without involving accuracy in minor details. In re-reading the Iliad, Book III. (Menelaos and Paris), and Book VII. (Ajax and Hector), we gain the impression that the artist, whoever he was (for the craftsman may have48 copied a known work), has here reproduced the essential elements of the drama. In adding persons, as Athene behind Paris, or Aphrodite behind Menelaos, the artist simply adhered to the conditions of the composition of a painting, which at this period scrupulously obeyed the rules of symmetry. Aphrodite is placed there to restrain the arm of Menelaos, as the gesture of her right hand indicates. Artemis, as a companion figure on the other side, represents the protecting gods of Troy (Fig. 9); two goddesses were not too much to watch over the handsome Paris.

The other reverse (Fig. 10) similarly conforms to, and diverges from, the Homeric text. As in the poem, Hector struck by a rock thrown by his adversary sinks to his knees and Apollo advances to support him. (The irregularly shaped object above indicates the stone.) In Homer, Athene does not appear, but here, placed as she is behind Ajax, whom she appears to be pushing forward with a gesture, she represents the protecting goddess of the Greeks. The symmetry of the two sides is essential. The decorative tradition requires it, and the painter sets his professional duty before his respect for a poetic text, in which no one saw anything more than a general49 theme for beautiful subjects and attitudes. We are quite convinced that the great painters took exactly the same liberties with the cyclic poems they interpreted. The description of the masterpiece of Polygnotos, The Taking of Troy, bears witness to this. The artist seems to have complied with the general information given in the epic, but not to have illustrated any given text.

Fig. 13. NEREIDS APPEALING TO NEREUS AND DORIS.

By Douris. Louvre Museum.

In spite of the archaic stiffness, the execution of the subjects delights us by the purity of line and the great care in detail. The painting is simply a drawing, hardly retouched with a few red lines. It is like a dry point engraving, in which all the lines are somewhat prominent. The symmetrical and parallel folds of the garments, details of the armour, the imbrications, the chasing of the helmets and cuirasses, the locks and curls of hair, are marvels of patient and conscientious work. The ornaments, as carefully finished as the rest, have the same stiff and rather metallic precision. Lastly, the black glaze, thick and velvety, gives an extraordinary brilliancy to the entire vase.

In considering the painting of the interior (Fig. 8), we move upwards another step. In its small compass, we consider it one of the50 finest paintings handed down to us from ancient times. It consoles us somewhat for the loss of so many masterpieces, and we cannot suppose that a potter, working alone in his workshop, invented this first Mater dolorosa, which is as touching as a Mantegna or a Roger Van der Weyden. Nowhere is a copy from a great painting more forcibly evident. Every one must be impressed by the striking resemblance of this Pagan and Greek creation to the emblem that has moved Christian souls for so many centuries. Eos, standing with outstretched and beating wings, bends toward the dead face of her son Memnon, her strained arms supporting his rigid body. The goddess, who represents the radiant morning and the promises of Nature awakening with the dawn, is here simply a despairing mother imprinting on her mind with one long look the beloved features she will see no more; the contrast is profoundly sad, and a creation worthy of a great poet. The body of the powerful prince of the Ethiopians, the ally of Priam, is entirely nude as it was taken up on the battlefield where his adversary Achilles had robbed him of his armour. The stiff legs are stretched out, the left foot still contracted with pain, the arms swing limply,51 the head drops, while the dishevelled hair, the delicate beard, and the closed eyes arouse an irresistible memory of the dead Christ. We have a true Pietà before our eyes.

What miracle in art, what unexpected chance unites Pagan and Christian art to express the same thought, in the same form? Is it not a proof that across the centuries great artists share the same thoughts, and to express the emotions of life create a universal language? Is it not this again which attracts us in Homer, in those never to be forgotten scenes, expressing so well the deep feelings of all men at all times; the farewell of Hector and Andromache, the return of Ulysses to Ithaca? Art soars above time and space, more than all else it embodies the solidarity of succeeding generations without any knowledge of one another.

A kylix in the British Museum, with The Adventures of Theseus (Fig. 11), of more recent form and style, teaches us still better that behind the vase painter may be concealed other and greater personalities, who are the true creators of the work of art. A famous kylix from the workshop of Euphronios shows us similar scenes glorifying the Athenian hero, forming with the Eos and Memnon, by Douris,52 and The Taking of Troy, by Brygos, a glorious trio of ceramic masterpieces, of which the Louvre is justly proud. In comparing the works of Douris with those coming from the workshops of Euphronios, the idea suggests itself that they either copied one another or borrowed from one common original. Both suppositions are possible. As already mentioned, no law or custom prohibited artistic plagiarism. If Douris knew of the beautiful work executed by his colleague, nothing prevented him from adopting it for his own use. But, on the other hand, the broad style of Euphronios’ production and the peculiar character of the adventure of Theseus recovering the ring of Minos from the bottom of the sea, a subject treated by Mikon, one of the great painters of the fifth century, finally the great number of works of art which at this period celebrated the national hero’s glory, lead us to believe that a potter had no need to look over his neighbour’s shoulder to gain suggestions for a theme of Theseus. He was surrounded by models in painting, sculpture, painted bas-reliefs, models, carved and engraved. The supposition of a common model or several models, from which a craftsman, in a way, chose the desired subject, seems most probable.

Fig. 14. SILENI PLAYING AND DANCING.

Vase by Douris. British Museum.

53 It is only in this sense and with such reservation that these two cups can be compared. In looking at the superb vase in the Louvre, no one will hesitate to give the preference to the workshop of Euphronios. In the interior is The Visit of Amphitrite; in this painting the author has retained all the seriousness of great religious art with a touch of archaism in the drawing and position of the characters, showing thereby that he has copied an ancient fresco; while, on the contrary, on the reverses, the combats of Theseus with the robbers Skiron, Prokrustes and Kerkyon, and the struggle with the Marathonian bull, are treated as in metopes, with bold, vigorous lines, giving rather a feeling of the influence of sculpture (Fig. 12).

The composition of Douris (Fig. 11) is more firmly knit, because it concentrates all the attention on the adventures of the hero against monsters and robbers. In the interior is the fight with the Minotaur, an ancient and classic theme from the sixth century; on the reverses, the defeat of Kerkyon, of Skiron and Sinis, and the hunt of the boar of Krommyon; two women give some variety and animation to the whole, the nymph Phaia who lived at Krommyon, and the goddess Athene who protects her favourite hero at his labours. Here again is a closely-knit54 trilogy; but, we must confess, the execution is far inferior to that of the cup of Euphronios. It is accurate and a little commonplace. There is, however, noticeable a desire to express landscape, a care for external ornament, visible in the palm tree and the small trees placed about, and by a cloak thrown upon a tree trunk. It is a rare mark among Greek painters, and worthy of note.

We will look more rapidly at the paintings of the kantharos at Brussels, the importance of which, as being a vase moulded by Douris himself, we have already mentioned (Fig. 1). The figures represent “Herakles’ contest with the Amazons,” an old type, nearly a century old, but with the added beauty of a clear and accurate style, and an admirably certain execution. Nor are the subjects new which are treated upon another kylix in the Louvre, The Rape of Thetis by Peleus. But Douris deserves the credit of having skilfully revived an old subject known on Corinthian and Attic vases of the sixth century. It is possible to follow in the Louvre the same painting done in turn by a Corinthian, then by an Attic painter of black figures, and lastly by Douris. It is of great interest to follow the development of the composition and of the grouping of the55 figures, of their attitudes, and of the drawing itself. We perceive here the same differences as in comparing a Madonna of Cimabue with one of Lippi. Symmetry of figures, stiff and angular outlines and severe features have given place to life and tender touches of the brush. At the same time, the close connection of these successive works appears most striking—the link with the past has never been severed; the fundamental conception has always remained the same; improvement has come from within, and extends to every little detail.

Fig. 15. HERA AND IRIS ATTACKED BY SILENI.

By Brygos. British Museum.

Douris has extended his composition and united the two reverse sides of the kylix. On one, the hero seizes the goddess, who struggles in his grasp and has summoned to her aid the magic art of transformations. These are given with all the naïveté of primitive art: to tell us that Thetis changes into a lion, and later into a serpent, the artist has drawn on one side a young lion seated on the shoulder of the goddess, and tearing with his teeth the arm of her ravisher; on the other a serpent lifts its twisted coils and darts its threatening jaws at him. The companions of Thetis, the Nereids, frightened by so bold an attack, take flight, and this gives the painter an opportunity of showing us young girls running in many56 graceful attitudes—the arms are tossed in gestures that are still angular; the bare feet and legs escape from the drapery, showing the rather lean suppleness of these young maidens. It is, at the same time, a skilful method of uniting the whole; in fact, on the other reverse we see other nymphs running, who come to tell the god Nereus and his wife Doris of the attempt. Both are seated on ornamented thrones with the Olympian majesty of a Jupiter and a Juno (Fig. 13). All the beauty of the famous group in the Panathenaic Frieze is already visible in their movements and their attitude.

CONTEST OF AJAX AND ULYSSES.

Fig. 16. THE VOTING OF THE GREEK CHIEFS.

By Douris. Vienna Museum.

Unfortunately the interior is defaced and restored, but the artist has shown no less ingenuity in its design. He has taken a theme frequently used by painters of red figures, and thus rendered rather commonplace—the libation; but instead of showing us the well-known scene of a soldier departing on a campaign and receiving the full cup from a woman, he has enlarged the subject, and shows us the god Poseidon seated, receiving a libation cup from the hands of a goddess, probably his wife, Amphitrite. Again a synthetic trilogy prevails in this composition: in the upper part of the vase the god of the sea and his consort57 are throned; in the lower part is enacted a little drama which takes place on the seashore, and has sea-gods as actors. Everywhere we find the intelligent skill of the Greek, and the easy art with which he beautifies all he touches. Was all this the personal work of Douris? or does the model he copies and follows deserve much of the credit? It will always remain an open question. As we possess a kylix by the potter Hieron (it has even been ascribed to Douris), another by the painter Peithinos, and many anonymous vases which repeat in similar form the details of The Rape of Thetis, we again incline towards the second hypothesis. How many sanctuaries in Greece, dedicated to the gods of the sea, must have contained paintings or reliefs of this kind!

It is the variety of models, in a word, which best explains the variety of styles among painters of vases. As we remarked above, no vase painter is of greater interest in this respect than Douris. If any one wishes to estimate at a single glance his often puzzling versatility, he need only look at the mythological painting on a large receptacle for wine in the British Museum (Fig. 14). The choice of the subject, The Bacchic Thiasos, repeated to satiety upon black-figured amphoræ of the58 sixth century, leads us to expect only a commonplace painting, but the artist instead brings us face to face with one of the most spirited sketches Greek art has left to us.