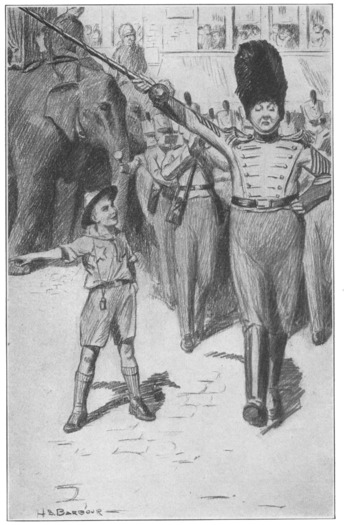

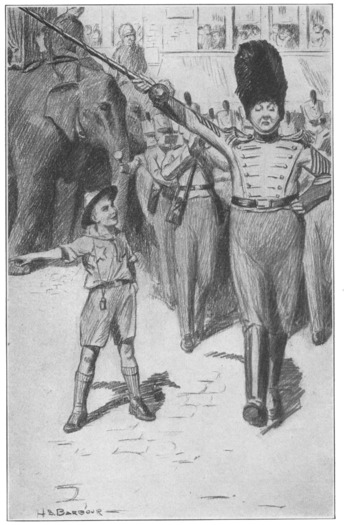

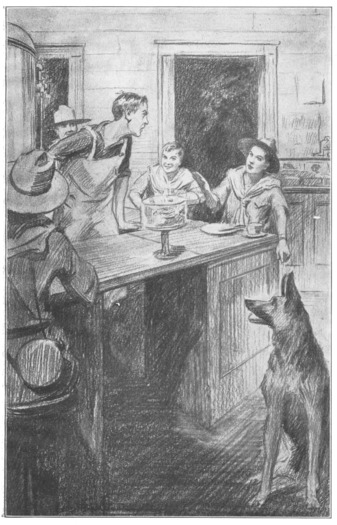

“GO UP THAT SIDE STREET!” ORDERED PEE-WEE.

“GO UP THAT SIDE STREET!” ORDERED PEE-WEE.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | He Appears |

| II | Mug |

| III | The Solemn Vow |

| IV | The Noon Hour |

| V | Queen Tut |

| VI | The Safety Patrol |

| VII | I Am the Law |

| VIII | The Protector |

| IX | The Parade |

| X | The Fixer |

| XI | Pee-wee’s Promise |

| XII | Culture Triumphant |

| XIII | Missionary Work |

| XIV | Seeing New York |

| XV | In for It |

| XVI | The Real Emerson |

| XVII | Alone |

| XVIII | Deduction |

| XIX | In the Dead of Night |

| XX | The Depths |

| XXI | Darkness |

| XXII | Arabella |

| XXIII | In the Woods |

| XXIV | Robin Hood |

| XXV | A New Member |

| XXVI | A Fresh Start |

| XXVII | Action |

| XXVIII | Not a Scout |

| XXIX | Voices |

| XXX | When Greek Meets Greek |

| XXXI | Bob, Scoutmaker |

| XXXII | The New Scout |

| XXXIII | Over the Radio |

| XXXIV | The Short Cut |

| XXXV | “Danger” |

| XXXVI | Pee-wee Triumphant |

Pee-wee Harris, or rather the left leg of Pee-wee Harris, emerged from an upper side window of his home, and was presently followed by the rest of Pee-wee, clad in his scout suit. He crept cautiously along an ornamental shingled projection till he reached the safety of the porch roof, where he stood pulling up his stocking and critically surveying the shady street below him.

The roof of the front porch was approachable by a less venturesome route than that of the ornamental coping. This was via the apartment of Pee-wee’s sister Elsie, and out through one of her prettily curtained front windows.

But he had been baffled in his attempt to violate this neutral territory by finding the door to her sanctum locked. He had demanded admittance and had thereupon heard whispering voices within. A hurried consultation between Elsie and her mother had resulted in a policy fatal to Pee-wee’s plans. Not only that, but worse; his honor as a scout had been impugned.

“Don’t let him in, I locked the door on purpose.” This from Elsie.

“I think he just wants to get to the porch roof,” Mrs. Harris had said, to the accompaniment of a sewing machine.

“I don’t care, I’m not going to have him going through here; if he sees my costume every boy in town will know about it and they’ve all got sisters. Everybody who’s invited to the masquerade will know exactly what I’m going to wear. I might just as well not go in costume. You know how he is, he simply couldn’t keep his mouth shut. What on earth does he want to do on the porch roof anyway? If he’s not well enough to go to school, I shouldn’t think he’d be climbing out on the front porch.”

“I suppose it’s something about his radio,” Mrs. Harris replied in her usual tone of gentle tolerance. “He’s going back to school on Monday.”

“Thank goodness for that,” was Elsie’s comment.

“That shows how much you know about scouts!” the baffled hero had roared. “It’s girls that can’t keep secrets! If you think anybody’d ever find out anything from me about what you’re going to wear——”

“Do go away from the door, Walter,” Mrs. Harris had pled. “You know that Elsie is very, very busy, and I am helping her. She has only till Wednesday to get her costume ready.”

Conscious of his prowess and resource, Pee-wee had not condescended to discuss a matter involving his manly honor. He would discourse upon that theme later when no barrier intervened.

He had returned to his own room and immediately become involved in a formidable system of rigging which lay spread out upon the bed and on the adjacent floor. The component parts of this were a rake-handle, two broomsticks lashed together, a couple of pulleys, several large screw-hooks, and endless miles of wire and cord.

This sprawling apparatus was Pee-wee’s aerial, intended to catch the wandering voices of the night and transmit them to Pee-wee’s ear. In the present instance, however, it caught Pee-wee’s foot instead, the section of rigging which was spread upon the bed was drawn into the entanglement, and our hero, after a brief and frantic struggle, was broadcasted upon the floor.

This was the first dramatic episode connected with Pee-wee’s radio. It was directly after he had extricated himself from the baffling meshes of his own handiwork that he had emerged from the window of his room, left foot foremost; which conclusively disproves the oft-repeated assertion of Roy Blakeley that Pee-wee always went head first.

Simultaneously with Pee-wee’s appearance on the roof of the front porch the chintz curtains in his sister’s window were cautiously drawn together so as to confound any attempt to look within. Pee-wee was too preoccupied to take note of this insult.

His eyes and thoughts were fixed upon a large elm tree which grew close to the sidewalk some yards distant across the lawn. The tree was stately, as only an elm knows how to be, its tall, thick trunk being free of branches to a point almost level with the roof of the house. At that height great limbs spread out over the sidewalk and shaded a large area of the Harris lawn. Pee-wee studied this tree with the critical eyes of an engineer.

He next drew out of the depths of one of his trousers pockets a ball of fishing-line, and out of the depths of the opposite pocket the detachable handle of a flat-iron. This he tied to the cord which he proceeded to unwind until he had released enough for his purpose. He frowned upon the distant elm tree as if he intended to annihilate it. Meanwhile, the muffled hum of the sewing machine could be heard through his sister’s window.

Pee-wee now replaced the ball of cord in his pocket and threw the flat-iron handle into the branches of the tree. It fell to the ground with the attached cord dangling after it. He pulled it up and cast it again. Twice, thrice, it failed to find lodgment in the branches. If it had been a kite or a beanbag or one of those twirling, ascending toys, it would have stayed in the tree upon the first cast, out of pure perversity. But the flat-iron handle had not the fugitive instinct, it would not stay.

Not only that, but a new complication presented itself. Mug, the puppy who resided with the Harris family, made a dramatic appearance on the lawn below just in time to catch the flat-iron handle as Pee-wee was about to lift it.

“You let go of that!” Pee-wee shouted. “You drop that, Mug, do you hear?”

But Mug, more interested in adventure than in science, did not drop it. Pee-wee tried to pull it away but Mug rolled over on his back in the full spirit of this tug of war, and was presently so much involved with the cord that obedience to Pee-wee’s thunderous commands was out of the question. For a few moments it seemed as if Mug might be hauled up bodily and made an integral part of the aerial.

Pee-wee endeavored by lassoing maneuvers and jump-rope tactics to release the enmeshed pup, using the entire porch roof for his stage of action. He loosed the cord, imparted long wavy motions to it, jerked it, pulled it to the right, pulled it to left, but all to no avail.

At last the puppy extricated himself, and with no regard at all for his harrowing experience, immediately made a dash for the departing flat-iron handle, caught it, shook it, ran half-way across the lawn with it, shook it again, and darted around a bush with it.

The bush was not a participant in this world war. Pee-wee pulled with all his might and main, part of the bush came away, the puppy pounced upon the fleeing fragment, it dropped from the cord, and the puppy with refreshed energy caught the flat-iron handle again, bracing his forelegs for the tussle, his tail wagging frantically. Thus has every great scientist encountered hardships and obstacles.

“You get away from that now, do you hear what I tell you!” Pee-wee roared.

He might have pulled the cord away from his diminutive antagonist but that it caught in a crack between two shingles at the edge of the porch roof. The cause of science seemed to be baffled at every turn, and on the edge as well. If Mug rolled over on his back again all hope might be lost in new complications.

In desperation, Pee-wee glanced about him for something to throw at Mug by way of diverting his attention to fresh novelties. The puppy was already on his back, the cord wound around one of his forelegs. The roof was clear of all possible missiles. Pee-wee pulled out a loose shingle and hurled it down but Mug saw it not.

Then Pee-wee did something which showed his power of sacrifice. He pulled out of his pocket the sole remaining cocoanut-ball from a purchase of three—for a cent. It was heavy, and sticky, and encased in tissue paper. There was no time to take even a single bite of it.

“Here you go, Mug! Here you go, Mug!” he called.

The new temptation enabled Mug to extricate himself. He did not care for candy but he was a ready adventurer in the matter of sports. His preoccupation with the rolling cocoanut-ball gave Pee-wee the opportunity to crawl cautiously to the edge of the roof and disentangle the cord where it had caught.

He now hurled the flat-iron handle with all his might up into the branches of the distant tree and there it stuck. To make certain of its security he pulled, first gently, then harder. It held fast.

Having successfully accomplished this part of his enterprise, he cast a wistful glance down upon the cocoanut-ball which Mug was pushing about the lawn with his nose.

Just then the window of his sister’s room was flung open.

“Walter, what on earth are you doing out there?” asked his distracted mother.

“I’m putting up my aerial, and if Anna kept Mug in the cellar like you told her to do, this cord wouldn’t have got all tangled up in the roof so I couldn’t pull it away from him and he got all tangled up in it too because Anna didn’t keep him in the cellar like you told her to do, I heard you. And I lost a good cocoanut-ball on account of her.”

“Walter,” said Mrs. Harris. “You shouldn’t be climbing and you shouldn’t be eating cocoanut-balls, when you’re just getting over the grippe.”

“I didn’t eat it, I told you!”

“Well, you come right in here and don’t you climb around on that ledge again.”

“Then I’m going to bring my stuff through here,” Pee-wee warned, as he climbed in through the window. “I’ve got the first part all done now and all I’ve got to do is bring the aerial out and tie it to the cord that’s on the roof of the porch and then all I have to do is to go down and then climb up the tree where the other end of the cord is and that way I can pull one end of the aerial out to the tree and after that all I have to do is to go up and drop a cord with a lot of hooks and things on it down onto the porch roof and get hold of this end of the aerial and pull it up to the attic window and then I’ll have the aerial stretched from the attic window to the tree where it can catch the sound waves, d’you see?”

“Good heavens!” said Elsie. “Talk of sound waves!”

Pee-wee now paused to glance about at the litter which filled his sister’s room. The multi-colored evidences of intensive manufacture were all about, on the bed, on the collapsible cutting-table, on and about the wicker sewing stand, in the jaws of the sewing machine. There was a riot of color, and a kind of atmosphere of cooperative ingenuity which even the masculine invader was conscious of. This was no ordinary task of dressmaking. A queer-looking specimen of headgear with a facsimile snake on the front of it testified to that.

The eyes of the rival manufacturer were attracted to this cotton-stuffed reptile, with projecting tongue made of a bent hairpin. He glanced at a motley costume besprinkled with writhing serpents, and among its other embellishments he recognized one as bearing a resemblance to the sphinx in his school geography.

Pee-wee had never inquired into the processes of dressmaking but here was a specimen of handiwork which caught his eye and set him gaping in wonder. Attached to the costume, which rivaled futuristic wall-paper in its motley originality, was a metal snake with red glass eyes. It was long and flexible. Pee-wee was a scout, a naturalist, a lover of wild life, and he gazed longingly upon this serpentine girdle.

“Walter,” said his mother, “I want you to promise me that you won’t say a word, not a single word, to anybody about the costume Elsie is going to wear at Mary Temple’s masquerade. I want you to promise me that you won’t even say that she has a big surprise. Do you think you can——”

“I don’t see why he can’t stay in the house another two or three days,” said Elsie, who was sitting at the machine. “If dad thinks he ought to stay home till Monday, he certainly won’t lose much by staying home till Wednesday. If he doesn’t go out, why then he can’t talk. I don’t see why you had to let him in.”

“Because I’m not going to have him endangering his life on that coping,” said Mrs. Harris.

“I might just as well send an item to the Evening Bungle,” said Elsie, with an air of exasperated resignation. The Bridgeboro daily paper was named the Bugle, but it was more appropriately spoken of as the Bungle. “Every single guest at the masquerade will know I’m going as Queen Tut long before my costume is ready,” the girl added.

“You shouldn’t have mentioned the name,” said Mrs. Harris.

“Oh, there’s no hope of secrecy now,” said Elsie. “He’s seen it, that’s enough.”

It was at this point that Pee-wee exploded. He spoke, or rather he roared, not for himself alone but for the Boy Scouts of America, which organization he had under his especial care.

“That shows how much you know about scouts,” he thundered. “Even—even if I knew—even if Queen Tut—and she was an Egyptian, you think you’re so smart—even if she was alive and came here—for—for a visit—and it was a secret—I wouldn’t say anything about it. Queen Tut, she’d be the one to give it away herself because she’s a girl—I mean she was—I mean she would be if she wasn’t a mummy, but girls can’t be mummies because they can’t keep still. Do you mean to say——”

“I’m sure we’re not saying a word, Walter,” said his gentle mother.

“Scouts never give away secrets,” Pee-wee continued vociferously. “Don’t you know a scout’s honor is to be trusted? It’s one of the laws. Gee whiz! A scout’s lips are, what d’you call it, they’re sealed!”

“Yours?” laughed his sister.

“Yes, mine. Do you think I can’t keep still?”

“I wish you would then, Walter,” said his mother.

“Well, then you better tell her not to say I’m as bad as the Bugle because, anyway, if anybody asks me not to give away a secret it’s—it’s—just the same as if you locked it up in an iron box and buried it in the ground. That shows how much she knows about scouts! Even—even if you wouldn’t let me bring my aerial through this room so as to get it out on the porch roof—even then I wouldn’t tell anybody what she’s going to wear to Mary Temple’s, I wouldn’t.”

This diplomatic feeler, intended to ascertain his sister’s attitude in regard to crossing her territory, was successful.

“What do you mean, bring your aerial through this room?” she asked.

“Don’t I have to get it out to the porch roof?” he asked. “Do you think I can carry it along the molding outside? Do you think I’m a—a caterpillar?”

“No, you mustn’t do that,” said his mother firmly.

“Well, then,” said Pee-wee conclusively. “Gee whiz, both of you claim to like music and concerts and things. If I get my radio up you can hear those things. Gee whiz, you can hear lectures and songs and all kinds of things. You can hear famous authors and actors and everything. All you have to do is come in my room and listen. Gee whiz,” he added wistfully, “you wouldn’t catch me giving away a secret. No, siree!”

“Walter,” said Elsie, trying to repress a smile. “If I let you bring your things through here will you promise me, word of honor, that you won’t tell Roy Blakeley or Westy Martin or Connie Bennett or any of their sisters or any boys or girls in school or anybody at all what kind of a costume I’m going to wear at Temple’s? The color of it or anything about it—or the snakes or anything? Will you promise? Because it’s going to be a big surprise.”

“Do you know what a solemn vow is?” Pee-wee demanded.

“I’ve heard of them,” Elsie said.

“Well, that’s the kind of a vow I make,” said Pee-wee. “And besides that, I cross my heart. You needn’t worry, Elsie; nobody’ll find it out. Because, anyway, scouts don’t tell. Geeee whiz, you leave it to me. Nobody’ll ever know, that’s sure. You can ask Roy Blakeley if I can’t keep a secret.”

“Well,” said Mrs. Harris, “I think we had better go down and have some lunch and after that you can finish what you’re doing. I do wish you wouldn’t talk so loud, Walter.”

“In about a week, maybe not so long,” Pee-wee said, “I won’t be talking at all, I’ll be listening all the time. I’ll be listening to Chicago and maybe even to Honolulu, maybe.”

“You sound as if you were talking to Honolulu,” laughed Elsie. “You remember what I said now?”

“Absolutely, positively and definitely,” Pee-wee assured her.

The masquerade to be given at Temple’s and the unique costume to be worn by Elsie were the subjects of discussion at luncheon. Pee-wee was too engrossed in his own enterprise to pay much attention to this feminine chat. He gathered that his sister’s costume was considered to be something of an inspiration and a masterpiece in the working out. It was expected to startle the younger set of Bridgeboro and to be the sensation of the evening. Queen Tut, consort of the celebrated King Tut of ancient Egypt. Favorite wife of the renowned mummy.

Mrs. Harris and Elsie were rather hazy about whether his name had been Tut and whether he had possessed a Queen Tut, but anything goes in a masquerade. There would be masked Charlie Chaplins by the score; colonial maids, gypsy maids, Swiss peasant maids, pirates, and war nurses galore. But only one Queen Tut, leader of fashion in ancient Egypt. The great Egyptian flapper....

Pee-wee hurried through his lunch and upstairs so that he might proceed with his work uninterruptedly, while his mother and sister lingered in discourse about the great event. He was well beforehand with his exterior work, for the radio set was not yet in his possession. It was to be a birthday present deliverable several days hence. But the secret (held by women) had leaked out and Pee-wee had thereupon set about preparing his aerial.

He now gathered this up and dragged it into Elsie’s room. The cross-bars were laid together, the connecting wires loosely wound about them. He struggled under the mass, tripped in its treacherous loops, brought it around endways so it would go through the door, and finally by hook or crook balanced it across the window-sill where he sat for a moment to rest. The operations on which he was embarked seemed complicated and large in conception. By contrast, Pee-wee seemed very small.

It was characteristic of him that his career as a radio-bug should be heralded by preparatory turmoil. For several days he had striven with saw and hammer in the cellar, rolls of discarded chicken-wire had been attacked and left for the cook to trip over, the clothes-line had been abridged, not a wrench or screw-driver or ball of cord was to be found in its place.

Pee-wee’s convalescence from grippe had afforded him the opportunity thus to turn the house and garage upside down in the interest of science. He had even made demand for hairpins, and had mysteriously collected all the package handles he could lay hands on. These wooden handles he had split, releasing the copper wires which ran through them and converting these into miniature grapnels with which he had equipped the end of a stout cord. This cord, not an integral part of his aerial, was nevertheless temporarily attached to it, whether by intention or as the result of tangling, one could not say. It dangled from it, however, like the tail of a kite.

The function of his cord, as Pee-wee had explained, was to elevate one end of the aerial to the attic window after the other end had been elevated to the tree. In that lofty position no voice, not even the voice of Honolulu, could escape it. The world (perhaps even Mars) would talk in Pee-wee’s ear.

The operations (conceived while lying in bed) for elevating this wire eavesdropper into position were even more extraordinary than the aerial itself, and Pee-wee was now prepared to take the next important step in his enterprise. This was to fasten to the aerial the cord which he had lodged in the tree and thereupon to ascend the tree himself and pull the aerial up at that end. Following this, he would make his next public appearance at the attic window from which he would dangle his grappling line, catching the other end of the aerial and pulling it up at that end. It could then be drawn tight, adjusted, and made ready against his birthday.

He was anxious to get the acrobatic part of his enterprise completed before the return of Dr. Harris who might be expected to interpose some objection to the flaunting exhibition of broomsticks and rake-handle above the front lawn; and who assuredly would have been expected to veto the acrobatic feature of the work.

The doctor might be expected to return at one o’clock; every minute after that hour would be fraught with apprehension. It was now past twelve-thirty, as Pee-wee knew from the advance guard of returning pupils bound for the high school on the next block.

Pee-wee shinned up the elm and was soon concealed amid the safety of the spreading branches. He was a monkey at climbing. He handed himself about, looking this way and that in quest of the flat-iron handle. Soon he discovered it caught on a stub of a branch like a quoit on a stake. The branches in its neighborhood were numerous and strong and he had no difficulty in approaching it.

He sat wedged in a comfortable fork of two stout branches, his foot locked in a limb just below him. An upright branch, like a stanchion, afforded the additional precaution of steadying himself with a hand, but that was not necessary. He was as safe and comfortable as if he had been on a merry-go-round with his feet in a pair of stirrups, his hand holding a brass rod.

Pleased with the coziness and safety of his aerial perch, he was moved to celebrate his arrival by eating an apple which he had thoughtfully brought from the dining table. And having finished the apple (and being only human) he was moved to drop the core plunk on the head of Emerson Skybrow, brother of Minerva Skybrow, who, being an exemplary youth and not having much appetite, was always in the advance guard of returning pupils. That studious boy paused, looked up curiously and proceeded on his way.

Pee-wee found it pleasant sitting high up in his leafy bower looking down on the unfortunates who had to go to school. He deferred his labors for a few minutes to enjoy the sight. He refrained from calling for fear of attracting attention from the house; his mother was likely to disapprove his ascent of the tree.

The straggling advance guard became more numerous, pupils came in twos and threes, then in little groups, until there was a steady procession toward the school. There were Marjorie Blakeley and the two Roberts girls going arm in arm—talking of the masquerade, possibly. There was Elsie Benton (big sister of Scout Dorry Benton) strolling along with Harrison Quinby—as usual. There were the Troville trio, so called, three sisters of the flapper type. Along they all sauntered, laughing, chatting....

Pee-wee, suddenly recalled to his duties, shook off his mood of contemplative reverie and reached for the flat-iron handle. Never in all its homely, domestic career had that flat-iron handle been cast for such a sensational role. Pee-wee held the cord which ran to the porch roof. He agitated it, moved it clear of leafy obstructions, pulled it taut, shook it away from a branch which rubbed against it, and began pulling vigorously.

Across the distant window-sill of his sister’s room tumbled the cumbersome aerial and fell on the porch roof. Elated, Pee-wee pulled. Soon he heard laughter below and looked down on the increasing group whence the laughter emanated. He saw Crabby Dennison, teacher of mathematics, standing stark still some yards beyond the tree, looking intently across the Harris lawn.

Directly beneath him the group had increased to the proportions of a crowd. And they were all laughing. Pee-wee gazed down at them, the while pulling hand over hand. Assured of his success, it afforded him pleasure to look down upon the curious multitude who seemed to have forgotten all about school.

It is said that Nero fiddled while Rome was burning. Thus Pee-wee pulled.

Suddenly a chorus of mirth arose beneath him, interspersed with flippant calls, the while the merry loiterers looked up, trying to espy him in the tree.

“Look what’s there!”

“Who’s running the clothes-line?”

“Where is he?”

“Did you ever?”

“What on earth——”

“It’s an oriental ghost.”

“It’s a jumping-jack.”

“It’s just an ad.”

“I never saw anything so——”

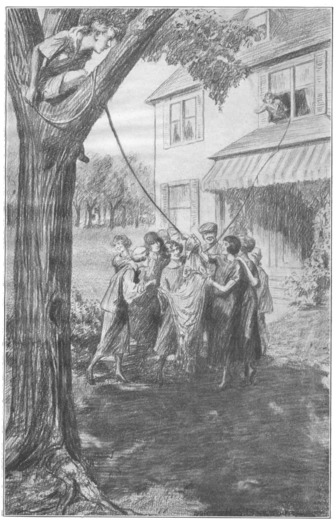

Pee-wee peered through the sheltering foliage toward the house and beheld a horrifying spectacle. Hanging midway between two sagging lengths of cord was his aerial. Depending from this was a motley apparition which he perceived to be his sister’s masquerade costume, revealed in all its fantastic and colorful glory to the gaping multitude. No Bridgeboro girl ever did, or ever would, wear such a costume in the streets; its bizarre design proclaimed its theatrical character.

It depended gracefully, naturally, from the treacherous aerial, as if Queen Tut herself (minus her head) were being hanged. No seductive shopkeeper could have displayed it more effectively in his window. Pee-wee stared dismayed, aghast.

“Oh, I know what it is,” caroled a blithe maid below; “it’s Elsie Harris’ masquerade costume; I just bet it is.”

It was a safe bet.

PEE-WEE BEHELD THE DANGLING COSTUME

Cold with horror, Pee-wee gazed upon this result of the ghastly treachery of his aerial. As far as he was able to think at all he believed that some truant end of wire had caught the royal robe and dragged it forth. There were many truant ends of wire. Perhaps one of the wire grapnels contrived from a package handle had coyly hooked it as the aerial crossed the window-sill. At all events it was hooked. And there it dangled above the Harris lawn in the full glare of the sunlight and in full view of the enthralled multitude.

They did not scruple to advance upon the lawn.

“Isn’t it perfectly gorgeous!” one girl enthused.

“What on earth do you suppose—— There’s one—I bet it’s Walter Harris up in that tree,” said another.

“Did you ever in your life see such a perfectly sumptuous thing?” chirped a third.

“Oh, I think it’s a dear,” said still another.

For a few moments the clamoring people were so preoccupied with the splendor of the dangling robe that they neglected to investigate the machinery which had brought it thus into the public gaze until a thunderous command from up in the tree assailed their ears.

“Don’t you know enough to go to school?” Pee-wee roared. “Gee whiz, didn’t you ever see an aerial of a radio before? Anyway, you’re trespassing on that lawn! Get off that lawn, d’you hear? You can each be fined fifty dollars, maybe a hundred, for trespassing on that lawn. Don’t you know enough to go to school?”

He pulled the cord in the hope of lifting the display above the reach of the curious, and immediately discovered the total depravity of his whole tangled apparatus. The cord was now caught somewhere below him in the tree and his frantic pulling only communicated a slight agitation to the dangling garment as if it were dancing a jig for the edification of its gaping audience.

The heavy cords, with the tangled mass of collapsed aerial midway between tree and house, sagged at about the curve of a hammock with the flaunting royal robe almost grazing the lawn. It was easily approachable for critical feminine inspection and as Pee-wee looked down it seemed as if the whole student body of the high school were clustered about it in astonishment and admiration. He could single out many of his sister’s particular friends, Olga Wetherson, Julia Stemson, Marjorie Blakeley.

“Get away from there!” he shouted, baffled by the treacherous cord and having no resource save in his voice. “Go on now, get away from there, do you hear? You leave that dress alone! Don’t you know you’ll be late for school? Don’t you know an accident when you see one? Do you think that dress is there on purpose? Go on, get off that lawn—that—that costume isn’t supposed to be there——”

The face of Elsie Harris appeared in the window, a face gasping in tragic dismay. Her mother’s face presently appeared also. They could not see the hero in the tree but they saw the exhibition and the crowd. And they could hear the hero.

“Tell them to go on away,” he bellowed. “It’s an accident; can’t you see it’s an accident that happened behind my back when I wasn’t looking and how could I help it if it got caught when I wasn’t there and didn’t know anything about it——”

“Oh, I think it’s just gorgeous, Else,” caroled Olga Wetherson. “How did you ever think——”

“Go on to school!” the hero thundered, “and let that alone. Don’t you know accidents can happen to—to—even to the most—the smartest people? Don’t you know that that isn’t supposed to be there on purpose?”

This was shouted for the benefit of his mother and sister and intimated his line of defense. But Elsie heard him not. One horrified glance and she had withdrawn from the window and buried her face in the pillows of the bed, clenching her hands and weeping copiously.

“Walter,” called his mother, “you come in the house at once.”

“Do you blame me for something that happened when I wasn’t there?” he shouted. “Do you say I’m to blame for something that happened behind my back? Gee whiz, do you call that logic? Hey, Billy Wessels, you’re in the senior class, gee whiz, is that logic—what happened behind my back when I wasn’t there to stop it? Can I be in two places at once?”

“Walter, you come down out of that tree and come in the house at once.”

“Do you say I’m to blame?” he roared.

“I say for you to leave whatever you’re doing and come in the house—at once.”

“Gee whiz.”

Mrs. Harris closed the window and turned to her daughter who still clutched the pillow as if it were a life preserver, and shook her head as if she could not look or speak, and sobbed and sobbed and would not be comforted.

Having entombed Queen Tut more effectually than ever the ancient Egyptians did, Pee-wee returned to school the following Monday. A lengthy conference between Elsie and her mother had resulted in the decision that the girl should go to the masquerade as Joan of Arc.

“Perhaps her martial character will protect her from annihilation,” said Mrs. Harris wistfully.

“I feel,” said Elsie, looking through tear-stained eyes, “as if I’d like to go as Bluebeard and kill every one I see—including all the small brothers. I would like to go as Attila the Hun and massacre all the boy scouts in Bridgeboro. Then I would seek out Marconi and assassinate him because he invented the radio—if he did.”

“Poor Queen Tut,” said Mrs. Harris amiably, launched upon the new costume. “Poor Walter.”

Poor Walter needed very little sympathy. He had gone to pastures new where fresh glories awaited him. Having triumphed over the grippe and Queen Tut, he presented himself at grammar school Monday morning. His aerial masterpiece remained where he had left it when peremptorily summoned to the house, festooning the lawn, minus its ornamental appendage.

Upon Pee-wee’s arrival at school, his teacher sent him to Doctor Sharpe, the principal, who wished to confer with him upon important matters.

“Harris,” said he, turning in his swivel chair, “I’m glad to know that you’re feeling better.”

“Yes, sir,” said Pee-wee.

“You had quite a time of it, eh?”

“Yes, sir,” said Pee-wee, with more truth than the principal suspected.

“Walter, I suppose you know of the plan we’ve adopted here of having selected pupils act as traffic officers during the rush hours, as I might call them, when the boys and girls are coming and going in the neighborhood of the school building.”

“Yes, sir,” said Pee-wee, hoisting up one of his stockings.

“The idea is to safeguard the pupils, especially the smaller ones, from careless drivers. The boys appointed to take this responsibility are of course pupils in good standing—intelligent, keen-witted, resourceful. They wear badges and have the cooperation and backing of the police.”

“They have whistles, don’t they?” Pee-wee asked.

Already he saw himself, or rather heard himself, blowing his lungs out in autocratic warning for the traffic to pause. His roving eye caught sight of something on Doctor Sharpe’s desk which gladdened his heart. This was a huge, celluloid disk or button as large as a molasses cookie and equipped with a canvas band to encircle the arm and hold it in place. If it had indeed been a molasses cookie, Pee-wee could hardly have contemplated it with deeper yearning.

“I was an official in the clean-up campaign,” Pee-wee said. “I made ’em clean up Barrel Alley. I cooperated with the police, I did. Once I even got a man arrested for throwing a pie in the street. Gee whiz, that isn’t what pies are for.”

“I should say not,” smiled Doctor Sharpe.

“So I know all about being a public official, kind of,” said Pee-wee.

“Well, that’s just what I thought. And besides you’re a scout, I believe?”

“You said it.”

“And I always lean toward scouts when it comes to a question of responsibility, public duty——”

“That’s where you’re right,” said Pee-wee. “Because scouts, you can always depend on them. If a scout says he’ll keep a—anyway, gee whiz, they’re always on the job, I’ll say that.”

“Well, I’m going to appoint you a traffic officer,” said Doctor Sharpe, “and you’re to wear this badge and act in accordance with these instructions.” He handed Pee-wee a carbon copy of a typewritten sheet. “Read it now and tell me if you think you can assume these duties. I’ve heard of your work in the clean-up campaign and that’s why I thought of you. We need one more officer.”

“Did you hear about me—and the dead rat,” Pee-wee inquired. “I’ll read it,” he said, alluding to the paper, “but anyway, I accept.”

The typewritten sheet read as follows:

Officers of the safety patrol are to be at their designated stations from 8.30 to 9.15 A.M.; and from 12 to 12.15 P.M.; from 12.40 to 1.15 P.M.; and from 3 to 3.30 P.M. Officers of the Safety Patrol are expected to carry their lunches as they will not have sufficient time to go home.

The duties of the officers are to insure the safety of pupils approaching and leaving the school, to warn, and when necessary detain traffic in the interest of safety.

Boys acting as officers of this patrol are to use their whistles and the uplifted hand in controlling traffic while on duty and their authority must be obeyed by drivers of vehicles in the school neighborhood. They shall report to the principal any flagrant disregard of their authority by drivers, taking the license number of the vehicle. They will have the full cooperation of the police officer stationed in the neighborhood.

Officers of the safety patrol will give their especial attention to the smaller children, escorting them when necessary. Theirs is the responsibility of keeping the street and neighboring crossings clear during the approach and departure of pupils, especially those of the lower grades.

Their teachers will permit them to leave the classroom early and no punishment for tardiness shall be incurred by their remaining at their posts, as provided, after the bell rings.

Pee-wee received the badge as if it were a Distinguished Service Cross tendered by Marshal Foch, or the Scout Gold Cross for supreme heroism. It looked not unlike a giant wrist-watch on his small arm. At the same time an authoritative celluloid whistle was handed him. He could not bear to conceal this in his pocket so he hung it around his neck by an emergency shoe-string which he carried.

He saw visions of himself frowning upon the proud drivers of Pierce Arrows and Cadillacs. He saw the baffled chauffeurs of jitney buses jam on their brakes when his authoritative hand said (as Marshal Joffre had said), “They shall not pass.” He saw himself the escort and protector of golden-haired Marion Bates, who had laughed at him and called him “Smarty.”

As he passed out through the principal’s anteroom, he noticed sitting there Emerson Skybrow, the boy on whose head he had let fall an apple core. It was a fine head, filled with the most select culture and knowledge. That was why Pee-wee had dropped the core on it. Emerson was not a favorite in the school, much less with the scouts. He said “cinema” when he meant the movies, he said “luncheon” and “dinner” instead of eats, he took “constitutionals” instead of hikes, he took piano lessons, and he spoke of shows as “entertainments” or “exhibitions.” There is much to be said for such a boy, but he is almost certain to have apple cores dropped on him.

Emerson was not popular, but he was useful. He was not nervy, but he was self-possessed. He talked like a grown person. It is significant that he had not been appointed to the safety patrol. But he was always getting himself appointed monitor. He distributed and gathered up books and pencils in the classroom, he “opened the window a little at the top” with a long implement, he could always be counted on for poetical recitations.

On the present occasion Emerson had been sent as a delegation of one, representing the entire student body, to prefer a particular request of the principal. It had been shrewdly considered that any request made by Emerson must be regarded as eminently proper and respectable. Emerson was never late to school and seldom absent. Therefore, a request involving an interruption of school routine in the interest of mere entertainment would command attention in high places if made by Emerson.

That is why he had been delegated to approach Doctor Sharpe and request that lessons he suspended for half an hour on the following morning in order that the pupils might beguile themselves with something altogether unorthodox in the humdrum daily life at school.

That was why Emerson was waiting in the anteroom.

The two outstanding features of Tuesday were the observance of Pee-wee’s birthday and the appearance of the circus in town. The circus gave two “stupendous performances.” Pee-wee gave one memorable performance.

The early morning of that festive spring day found him harassed with perplexity. His troubles were financial. He awoke early and lay for a little while allowing his mind to dwell on the radio set which he knew his father intended to give him. He had extracted that much information from his father, but he had not been able to extract the gift. Doctor Harris had old-fashioned ideas about birthdays.

Pee-wee’s mother had been won over and had given him her personal gift of a dollar, most of which already had found its way into circulation via Bennett’s Fresh Confectionery on Main Street. As for his sister Elsie, Pee-wee felt it would be rash to expect anything from her in the way of a present!

He had exactly fifty-two cents. Purchases necessary to install his radio set would require forty-seven of this, leaving five cents which would be of no use, except to enable him to drink his own health in an orange phosphate at Bennett’s. Or he might wish himself many happy returns of the day with an ice cream cone.

In any case he could not go to the circus, unless he postponed the installation of his radio till such time as his circumstances improved. He considered this alternative and decided that the radio must be installed for immediate operation, circus or no circus.

The faint hope which he had dared to indulge that Elsie might forget the episode involving a scout’s lack of secrecy in the glow of the birthday morn proved entirely unjustified. She did not even come down to breakfast. Having carefully laid his precious gift on the table in his room, and feasted his eyes upon it as long as his official duties would permit, he emerged with his school books, the while whistling audibly in the forlorn hope that the new Joan of Arc might hear him and relent. After this all hope was abandoned.

Renouncing his lingering dream of an evening at the circus and consoling himself with thoughts of his radio, he hurried to school with the more immediate joy of his official position uppermost in his mind. He reached the scene of his public duties promptly at eight-thirty and immediately put on his costume, consisting of his celluloid badge and his dangling whistle.

The public school was on Terrace Avenue and filled the entire block from West Street to Allerton Street. Pee-wee’s stand was at the intersection of Allerton Street and Terrace Avenue. Here, for half an hour, he raised his hand, blew his whistle, beckoned reassuringly to the small children who paused uncertainly at the curbs. Occasionally he honored some little girl by personally conducting her across the street.

“Stop, d’you hear?” he thundered at a bus driver who had declined to take him seriously. “D’you see this badge? If you don’t stop, you see, I’ll have you fined—maybe as much as—as—ten dollars, maybe.”

And upon the cynical bus driver’s pausing, the autocrat leisurely escorted little Willie Hobertson, whose leg was held in a nickel frame, across to the school.

He stopped Mr. Runner Snagg, the auto inspector, who was speeding in his official car. Here authority clashed with authority, but Officer Harris won the day by boldly planting himself in front of the inspector’s roadster the while he beckoned to a group of pupils.

“You thought you’d get away with it, didn’t you?” he shouted. “Just because you’re an inspector you needn’t think you don’t have to obey the law—geeeeee whiz!”

Lacking the size and dignity of a regular policeman, he made up for it by abandoning himself to approaching traffic, standing immovable before vehicles, sometimes until the very bumpers and headlights touched him. They stopped because he would not budge.

Perhaps he erred a trifle on the side of dictatorship that first morning, but the pupils all reached school in safety, and without confusion or delay. He stopped everything except the flippant comments of older boys who were guilty of lèse majesté. But even these he “handled,” to use his own favorite word.

“Look who’s holding up the traffic!”

“Hey, mister, don’t run over that kid, you’ll get a puncture.”

“Look at that badge with a kid tied to it.”

“Look out, kid, you’ll blow yourself away with that whistle.”

Pee-wee’s cheeks bulged as he blew a frantic blast to warn Mr. Temple’s chauffeur, who was taking little Janet Temple to school in the big Temple Pierce Arrow. Fords and Pierce Arrows, they were all the same to Pee-wee. He would have stopped the fire engines themselves.

“Hey, mister, look out, there’s a boy behind that badge,” a mirthful onlooker called.

“Cheese it, kid, here comes President Harding.”

“Here comes the ambulance, Pee-wee. Don’t blow your whistle, you’ll wake up the patient.”

“Hey, kid, here comes a wop with a donkey, blow your whistle. Hold up your hand for the donkey.”

“Hold up your own hand!” Pee-wee shouted. “He belongs to your family.”

“Hey, Pee-wee, tell that sparrow to get off the street or he’ll run into a car and bust it.”

“Stand on your head, kid, that’s what I’d do!”

“You haven’t got any head to stand on!” Pee-wee shouted.

By nine o’clock all the pupils were in school except a few tardy stragglers. For ten minutes more these kept coming. Pee-wee held his post.

It was about nine fifteen and he could hear the singing within, when he reluctantly decided that it was time for him to relinquish his enjoyable occupation. The boy up at the next street intersection had already disappeared.

But one thing, or, to be more exact, two things, detained Pee-wee at the neighborhood of the post which he had graced with such efficiency. One was the sound of distant music. The other was the approach of a dilapidated motor truck, heavily laden with bales of rags and papers. It was this truck, rather than the faint music in the air, which attracted our young hero.

The truck came lumbering along Terrace Avenue, its huge load shaking like some Dixie mammy of vast dimensions. The piled-up bales and burlap sacks were agitated by each small hubble in the road; the vast, overhanging pile tilted to an alarming angle. In a kind of cave or alcove in this surrounding mass sat the driver, almost completely enclosed by the load.

Pee-wee had no intention of interrupting the progress of this outlandish, bulging, tipsy caravan. The responsibility for what shortly happened is traceable to little Irene Flynn, who was hurrying to school in frantic haste, being already twenty minutes late. When Pee-wee’s eyes were diverted from the advancing load to her spectacular approach, she was almost at the curb, panting audibly, for she had run all the way from Barrel Alley.

In the full glory of his authority, he planted himself immovably in the middle of the cross street and raised his autocratic hand, at the same time beckoning to little Irene to proceed across Terrace Avenue. With cynical assurance of his power, the truck driver disregarded Pee-wee, and was presently struck with consternation to find himself within fifteen feet of the little official, and the official still immovable. Other drivers, finding Pee-wee a statue, had driven around him and gone upon their way, to his chagrin.

But the driver of the truck could not do that, for in deference to his top-heavy load, he must keep a straight course. He therefore jammed on both his brakes with skilful promptness; the load shook as if stricken with palsy, a bale of rags rolled merrily off like a great boulder from a mountain, then the whole vast edifice swayed, collapsed, and was precipitated to the ground. A jungle of bales, sacks and huge bundles of loosely tied papers and rags decorated the middle of Terrace Avenue. It seemed inconceivable that any single truck could have contained so much. The street was transformed into a rubbish dump.

It is said that music has charms to soothe the savage beast, but the swelling strains of an approaching band, which could now be distinctly heard, did not soothe the driver of the truck. Pee-wee had entertained no idea that he was as many things as the driver called him. The number and character seemed also to astonish little Irene Flynn, who stood beside her protector in the middle of the street.

“Yer see wotcher done?” bawled the man. “All on account o’ that there blamed kid! I’d oughter ran over yer, that’s wot I’d oughter done, yer little——”

“Just the same you didn’t,” said Pee-wee. “Why didn’t you stop when I first raised my hand? Gee whiz, can’t you see I’m a—I’m in the official patrol? Maybe you think I didn’t mean what I said when I motioned. Now, you see, you’ve got only yourself to blame. Gee whiz, that shows what you get for defying the law—geeee whiz!”

“It serves him right,” little Irene whispered to Pee-wee, as if she were afraid to advertise her loyalty. “It serves him a good lesson.”

Pee-wee would have withdrawn from this scene of devastation, escorting Irene, except that the approaching music grew louder and louder, and he and his little charge paused to ascertain the occasion of such a festive serenade. He was not long kept in doubt. Around the corner of Broad Avenue, which was the first cross street beyond Allerton, where Pee-wee was stationed, appeared a proud figure in a towering hat, swinging a fantastic rod equipped with a sumptuous brazen sphere.

“Oh, look at the soldier man, he’s got a barrel on his head, like,” gasped little Irene in awestruck admiration.

“It’s a drum-major,” said Pee-wee, staring. “Gee whiz, the circus is coming!”

Even the irate driver of the truck paused in the midst of the chaos he had wrought to gaze at the imposing spectacle which emerged around the corner and advanced down the wide thoroughfare of Terrace Avenue. Behind the red-coated band Pee-wee beheld three pedestrians walking abreast, and he knew that they would not be obedient to his raised arm. These were huge elephants, complacent, serene, contemptuous of the law.

“Oh, look—look!” gasped little Irene. “They’re efilants, they’re real efilants! Will they eat you?”

Pee-wee was too absorbed with the motley spectacle to answer. Behind the elephants came rolling cages, and amid the strains of martial music he could hear a mighty intermittent roaring—savage, terrible. Little Irene grasped his arm.

“Don’t you be scared,” he said. “I won’t let them hurt you.”

Pee-wee was a true circus fan, but he was first of all a traffic officer. He knew that the parade could not easily pass this litter. Zigzagging his way through the chaos of crates and bales and bundles, he headed off the imposing procession before it reached the corner. He seemed a very small rudder to such a large ship, but he pointed up the side street, displaying his badge ostentatiously, and shouting at the top of his voice.

“You can’t pass here, you’ll have to turn up that street! Go on, turn into that street and you can come back into Terrace Avenue, the next block below. Hey, go up that side street!”

Without appearing to pay the slightest attention to him the drum-major, swinging his stick and looking straight before him, inscribed a wide, graceful turn into Allerton Street, and was mechanically followed by his red-coated band. They were blowing so prodigiously on their instruments that they seemed neither to know nor care which way they went and were steered as easily as a racing shell.

It is true that one of the elephants seemed sufficiently interested to pick up a bale of rags, which had rolled somewhat beyond the center of disorder, and hurl it onto the sidewalk, but he swung around with his companions.

Following the elephants came the camels and they too swung around; it was all the same to them. Followed an uproarious steam calliope which made the turn with a clamor to wake the dead. Then came the rolling cages with their ferocious tenants. And all these turned into Allerton Street following the calliope which followed the camels which followed the elephants which followed the band which followed the drum-major who followed the direction authoritatively indicated by Pee-wee Harris.

“Come on, anyway, I’m not going into school yet, because I’m going to see it,” Pee-wee said to Irene.

“I’ll get the blame on me ’cause I got late,” little Irene protested, as she followed him to a point of vantage on Allerton Street.

“You got a right to see the parade, gee whiz,” Pee-wee said. “You know Emerson Skybrow? He never does anything wrong and he got ninety-seven in arithmetic, and even he’s going to see it, I heard him say so. So if he’s late on purpose, I guess you can be. Anyway, I’m an official.”

This last reminder was what proved conclusive to little Irene; in the protection of the law, she could not do wrong. She had seen her valiant escort deflect a whole circus parade; surely he could handle Principal Sharpe. She clung to him with divine faith and they turned the corner into Allerton Street which was now thronging with people. They were mostly either too old or too young to go to school; there was a noticeable absence of children.

Pee-wee led the way to the hospitable porch of the Ashleys, where Mrs. Ashley and her married daughter had hurriedly emerged, lured by the thrilling music. The married daughter held her baby in uplifted arms saying, “See the pretty animals.” Neighbors presently availed themselves of the spacious Ashley porch which became a sort of grandstand for the neighborhood.

People who had not thought enough about the parade to wait on Terrace Avenue were ready enough to step out or to throw open their windows, now that the motley procession was passing their very doors. In less than half a minute the quiet side street was seething with excitement. Women hurried, babies cried, lions roared, the steam calliope drowned the stirring music of the band, a gorgeous float bearing a fat woman and a skeleton lumbered around the corner.

Little Irene Flynn was somewhat timid about the proximity of wild beasts, but this feeling was nothing to her excitement at finding herself upon the porch of the sumptuous Ashley residence. But apparently her hero was not in the least abashed at finding himself in such a distinguished company. He and Irene sat side by side on a lower step, watching the parade with spellbound gaze.

“I’m the one that fixed it so you could all sit here and see it,” Pee-wee announced for the benefit of the company. “I made it turn the corner.”

“Really?” asked Mrs. Ashley.

“Absolutely, positively,” said Pee-wee; “you can ask her,” alluding to Irene.

“Yes, ma’am, he did,” Irene ventured tremulously.

“I’m on the school traffic patrol,” Pee-wee explained, “and I have charge of the traffic up on the corner. I stopped a truck so she could get across the street and it served the man right because he wasn’t going to stop, but anyway he had to stop because I got authority, so then his whole load fell over and it served him right.”

“It just did,” said a lady.

“So then I told the—did you see that man with the big, high hat leading the band? I motioned to him to come down this way and turn through the street in back of the school and do you know how it reminds me of the Mississippi River?”

“I can’t imagine.”

“Because all of a sudden it changes its course, did you know that? And you wake up some fine morning and it’s not near your house any more. Maybe it’s a mile off.”

“Isn’t that extraordinary!”

“That’s nothing,” said Pee-wee. “Islands change too; once North America wasn’t here, but anyway I’m glad it’s here now because, gee whiz, I have a lot of fun on it, but anyway if it hadn’t been for me you wouldn’t all be sitting here watching the parade go by, that’s one sure thing.”

“We ought to give you a vote of thanks,” some one observed.

“It’s what you kind of call a good turn that happens by accident,” Pee-wee said. “You know scouts have to do good turns, don’t you? They have to do one every day. Anyway, gee whiz, I’m glad that truck broke down. If a circus parade turns, that’s a good turn, isn’t it—for the people that live on the street where it turns?”

“Oh, absolutely, positively,” laughed an amused lady.

“There goes a leopard,” Pee-wee said. “I know a way you can catch a leopard with fly-paper, only you got to have a lot of it. Leopards have five toes, do you know that? I can make a call like a leopard, want to hear me? Scouts have to know how to imitate animals so as to fool ’em.”

“Can you imitate a cataclysm—a vocal cataclysm?” asked a young woman.

“Is it an animal?”

“No, it’s something like a volcanic eruption combined with an earthquake.”

“Suuure, I can imitate it.”

“Well, don’t, you’ll only drown the music.”

“Shall I keep still so you can hear the tigers roar?” he asked.

“No,” she said, “we don’t care if the tigers don’t.”

“Gee whiz, they should worry,” said Pee-wee.

They seemed not to worry as they paced their narrow cages. Following them came gorgeous chariots drawn by spirited horses, resplendent in gold harness and driven by men resembling Julius Caesar. Came a clown driving a donkey, then more floats, then two giants, then some midgets in a miniature automobile.

Little Irene watched, spellbound. Pee-wee divided his attention between the pageant and the company, which seemed to enjoy him quite as much as it did the spectacular procession. He seemed to have appropriated the parade as his own private exhibition.

“I suppose you’d have arrested the whole parade, elephants and all, if they hadn’t turned into this street,” a lady said.

“They got a right to do what he says,” said the admiring Irene.

“Do you see my badge?” Pee-wee asked, displaying it. “I got a whistle, too.”

The parade moved but one block along Allerton Street then turned into Carlton Place which paralleled Terrace Avenue, then to the next cross street, and so into the thoroughfare of Terrace Avenue again, where restless and increasing throngs awaited its coming.

Inside the school, also, an excited, expectant throng waited. Special permission had been given to the whole student body to view the parade and every one of the many windows facing on Terrace Avenue was filled with faces. Teachers (who are universally referred to as old by their pupils) were young again in those slow, expectant, listening moments. “Old” Cartright, “Old” Johnson, “Grouchy” Gerry, “Keep-in” Keeler were all there, with their clustering, elbowing charges about them, waiting to see the parade.

The large windows of the gymnasium were packed. So were the windows of the big assembly room. “Old” Granger, the music teacher, seemed almost human for once, as he actually elbowed his way to a front place where Doctor Sharpe smilingly awaited the coming of the great show.

The weather was too brisk for open windows, but the several hundred waiters heard the muffled strains of music, three blocks, two blocks, one block off, and in the renewed excitement and suspense many noses grew flat in an instant, pressed eagerly against the glass.

One block away. Half a block away. The great bass drum sounded like thunder. They could hear the complaining roar of a monarch lion. The frightful but rousing din of the calliope (eternal voice of the circus) smote their ears. Louder, louder, louder sounded the music. In a minute, half a minute, the motley heralds of the fantastic, gorgeous, roaring spectacle would show themselves.

Then the music seemed a trifle less stentorian and, presently becoming more and more subdued, was muffled again by distance. The lion was either losing his pep or retreating. His roar seemed less tremendous—at last he seemed to speak in a kind of aggrieved whisper.

Even the terrible calliope modified its shrieking and discordant tones. It seemed to be receding. Could the Evening Bungle have committed the greatest bungle of all its bungling career and misstated the line of march? Impossible, perish the thought! Where but down the fine, broad thoroughfare of Terrace Avenue would a circus parade make its ostentatious way? The pupils waited, patient, confident, all suspense. The procession had paused....

They waited five, ten, fifteen minutes, till the calliope had ceased entirely to shock the air with its outlandish clamor and the lion had ceased to roar.

Twenty minutes.

Then, suddenly, a procession appeared indeed before this thronging grandstand of the school. It consisted of two people, little Irene Flynn and Scout Pee-wee Harris. But it was not without music, for he was demonstrating the powers of his official whistle for her especial edification, his cheeks bulging with his official effort.

Straight along the thoroughfare they came, the eyes of the waiting multitude upon them. They ascended the steps of the large central entrance, then disappeared to view and presently reappeared in the main corridor and entered the adjacent office of the principal, which awful sanctum had been invaded by a score of pupils and teachers who still crowded at the windows.

“I had to stay as late as this on account of making the parade turn into Allerton Street,” said the small official, “because I made a truck driver stop on account of his being—maybe—he was going to run over Irene Flynn, but, anyway, I made him stop and his load went over—gee whiz, awful funny—all over—and so then I made the parade turn into Allerton Street and we stayed to watch it and, oh, boy, it was peachy. There were wild animals and chariots with men in kind of white nightgowns in ’em and clowns and elephants and zebras and fat women and skinny men and dwarfs and a kind of a man only not exactly a man that they held by a chain and he was wild and uncivilized like—you know—like scouts, and he growled and looked like a monkey, and, gee whiz, they had two giraffes and a lady with a beard like Smith Brothers’ cough drops, and I sat on Mrs. Ashley’s porch and a boy that sits in a window because he’s sick saw the parade, so that shows how I did a good turn, even Mrs. Ashley said so, and they had snakes in a glass wagon—gee whiz, you ought to have seen all the things they had! Wasn’t it dandy, Irene?”

“You saw the procession?” said “Grouchy” Gerry.

“Oh, boy, did we! Geee whiz, you ought to have seen it. We saw it all from beginning to end, didn’t we, Irene? And, anyway, she has to be excused on account of a parade being something special. Oh, boy, if you had seen it, you’d have said it was something special——”

He paused for breath and in the interval a boy student sank into affected unconsciousness across a table. Another staggered to the wall, leaning limp and helpless against it. A girl buried her head on another girl’s shoulder, silently shaking. Principal Sharpe managed to reach his revolving chair, swung around in it away from the scene of anguish, leaned forward, placed his two hands before his face, and said nothing. Miss Rossiter, proud teacher of our hero’s own class, gave one look at him, an inscrutable look, then glanced at another teacher, turned around and laid her face gently on the top of the Encyclopedia Britannica case in a kind of last abandonment of laughing despair.

“He—he—boasts—he——” she tried to speak but could not. “He c-cl-aims that his sp-ec—specialty is—f-f-fixing—fix—fixing. Oh, dear, I have —a—a—headache!”

“So didn’t I fix it all right?” demanded Pee-wee proudly. “Gee whiz, you can leave it to me to handle traffic out there, because I’m not scared of them. Oh, boy! You should have seen those elephants!”

That afternoon, in composition hour, the pupils did not (as has been planned) write upon the theme of “What impressed me most in the procession.” One waggish boy did, indeed, place that heading at the top of his composition sheet and wrote nothing whatever underneath it, which seemed a truthful enough composition when you come to think of it. But he was kept in after school for essaying the rôle of humorist.

Emerson Skybrow was also detained after school that afternoon, but not for being a humorist; far from it. Life was no jesting matter to Emerson. He remained for the wildly adventurous task of sharpening the lead pencils used in his class. He was a sort of chambermaid in the room which he adorned.

But he did not remain long enough to complete his task for there were important matters on for the evening. Emerson was going to a show, or, as his mother preferred him to say, an “exhibition.” He tried to remember to say this and succeeded very well. In the case of a circus, he could not very well say exhibition. But he could not say show. So he compromised and said circus exhibition. But he ran plunk into a catastrophe on his way home which all but proved fatal to his plans.

Meanwhile Pee-wee, fresh from his latest triumph, proceeded at once to Main Street and to the “five and ten” where he began a purchasing debauch at the hardware counter. Having fifty cents, he bought ten different things, or rather lots, at five cents each. These appeared to represent plans both novel and far-reaching in the field of radio equipment.

He counted out three dozen screws for a nickel; he purchased two brass handles evidently intended for bureau drawers, at the same price. He purchased a roll of tire tape and a half-dozen brass screw eyes. His resources thus diminished to twenty-five cents, he pursued a more conservative policy in his inspection. He finally bought three boxes of copper staples for a nickel and allowed his eyes to dwell fondly on a compartment full of ornate picture hooks, thirty for five cents. He paused to consider how he might use these and having found a place for them in his new field of scientific interest, he counted out thirty; then the salesgirl recounted them and put them in a paper bag.

The remainder of his capital was spent at the counter where radio parts and accessories were sold. He bought six little brass rods. He did not know exactly why, but they looked tempting and had a mysterious suggestion of electrical apparatus about them. In this carnival of temptation, he was strong enough to reserve one lonely nickel for an ice cream cone on the way home. It was, perhaps, the most sensible of all his purchases for at least he knew how he was going to use it.

He started home penniless. No millionaire or United States president could ever, in his struggling days of early youth, have been a poorer boy than Pee-wee.

And now in his state of financial ruin, flamboyant circus posters confronted him on every hand. They called to him from fences and shop windows. He knew that the afternoon performance was already under way. A fitful hope still lingered in his mind that something would happen to enable him to see the evening performance. Warde Hollister (Bridgeboro’s most confirmed radio-bug) was coming the following day to bring order out of chaos in the matter of Pee-wee’s aerial and to hook up the apparatus. Until then he could do nothing.

He paused now and again, gazing wistfully at the seductive posters. One of these showed three elephants playing a game of one-o’-cat with a monkey for umpire. Another showed a pony walking a tight rope. Still another showed the clown’s donkey appropriately cast in the role of traffic cop.

On the way home he resolved upon a policy which from previous experience seemed to hold out some prospect of success. He would prefer no requests but would enthusiastically relate to his mother the unexpected glories of the great show, leaving it to her own conscience what she would do in the matter. But his mother and sister had both gone to the city in the interests of Joan of Arc, leaving the dismal message that they might not be home for supper at the usual time. As for Doctor Harris, he was absent on a case and his return was problematical. So Pee-wee withdrew to his room where he drowned his sorrow by feasting his gaze upon the waiting apparatus.

After a little while he went forth intending to visit the scene of the circus and enjoy such external features of the “great exhibeeeshun” as might be free. On his way through Grantly Place he came upon Emerson Skybrow standing before a vacant store. This had lately been a drug store but had proved ill-advised in that purely residential section. The circus man, however, had filled its dusty windows with flaring posters of “The world’s most stupendous exhibition.”

In the sidewalk before the windows of this store was an iron grating of several yards’ area which opened upon a shaft leading into the cellar. As Pee-wee approached, Emerson was standing upon the grating looking intently down into the shaft below. Something evidently had happened and it seemed likely to have been incidental to his inspection of the posters in the window.

“What’s the matter?” asked Pee-wee.

“It’s plaguy exasperating,” said Emerson.

“What is?”

“This infernal grating; I dropped my tickets down; you can see them down there.”

Pee-wee looked down, and amid the litter of soiled and crumpled papers at the bottom of the shaft saw a small, fresh-looking, white envelope.

“I can’t go to the exhibition without them, I know that,” said Emerson, annoyed. “And I can’t get them, that’s equally certain.”

“What d’you mean you can’t get them?” Pee-wee demanded. Then in a sudden inspiration, he asked, “How many tickets are there?”

“Just two,” said Emerson, preoccupied with his downward gaze.

“You—you going with your mother or your sister?”

“Goodness, no, they’re too busy getting Minerva ready for the Temple’s masquerade.”

“You—you—maybe—I bet you’re going to take a girl. Hey?” Pee-wee’s interest was beginning to liven up. “I—gee, I bet you’re not going alone.”

“It looks as if I were not going at all,” said Emerson.

“Anyway, if you asked me to go, I wouldn’t refuse,” said Pee-wee, casting a wistful eye upon the posters.

“I’m sure you’d be only too welcome,” said Emerson.

“Gee whiz, do you mean it?” Pee-wee gasped.

“It isn’t much of an invitation though,” said Emerson, “with the tickets so near and yet so far——”

“You call that far?” Pee-wee shouted, his hope mounting. “But anyway, I bet you’re only fooling; because—I’m not a pal of yours. Are you fooling? Do you mean it, honest?”

“Even if I had the tickets,” Emerson assured him, “I couldn’t go unless I found a boy to go with me; my mother doesn’t want me to go alone. So it would be a favor on your part.”

“Geeeeeeeeeeee whiz!” said Pee-wee. “Will you promise to take me with you if I get the tickets?”

“Would you promise to go?” Emerson asked. “What are you talking about?” Pee-wee vociferated. “Would I promise to go! Oh, boy! You just get a picture of me refusing!”

“You’d have to ask your mother, but anyway I don’t think you can get the tickets.”

“You should worry about my mother,” said Pee-wee excitedly. “You leave her to me; handling mothers is my middle name—fathers too. And sisters and everything. Don’t you worry, I can go and I promise to go absolutely, positively, cross my heart. And I’ll get the tickets too.”

“I’ve already asked three boys and none of them could go,” said Emerson. “Two of them didn’t care to——”

“What?” gasped Pee-wee.

“The other two were not allowed to.”

“I want to and I’m allowed to both,” Pee-wee said with increasing elation. “And I promise absolutely and definitely and positively and double sure to go, so there! Gee whiz, I know how it is with those fellows, they just, you know, kind of——”

“I know I’m not popular,” said Emerson.

“Oh, boy, you’re popular with me,” said Pee-wee.

It was never clearly determined what was the nature of the part Emerson played in this matter. Pee-wee’s scout comrades believed that he used the “fine Italian hand” and effected a masterstroke of quiet diplomacy. His parents and his teacher, however, protested that he was simply preoccupied and absent-minded and that his grand coup was attributable to these poetical and intellectual qualities.

He sat upon the step of the closed-up store watching Pee-wee’s frantic and resourceful activities with a certain detachment. He did not join the little scout nor render him any assistance either of a practical or advisory character. He seemed altogether too well bred to sit upon a door-step. Nor did he seem particularly edified by Pee-wee’s running comment as he made ready to give a demonstration of his scout resourcefulness.

“Gee whiz, you needn’t be afraid I won’t go,” Pee-wee reassured the complacent watcher. “Because scouts they always keep their words; no matter what they say they’ll do, they’ve got to do it. That’s where you make a mistake not being a scout. Because if you were a scout, you’d know just how to get those tickets.”

He had unwound a sufficient length of twine from a ball he had carried in his pocket since his encounter with his aerial, and now he made a mysterious, hurried tour of all the neighboring trees, feeling them and inspecting them critically.

“I bet you wonder what I’m doing,” he said. Emerson did wonder, but he said nothing.

Visions of the “Great Exhibeeeshun” acted like a stimulant on Pee-wee, impelling him to frantic haste in all his movements.

“You’ll get all over-heated,” Emerson observed.

“What do I care!” said Pee-wee.

Having found a tree to his liking, he brought forth his formidable scout jack-knife and scraped some gum from a crevice in the bark and proceeded to smear this upon a small stone which he had fastened to the end of the twine.

“Now do you see what I’m going to do?” he asked proudly. “Maybe you didn’t know that that’s scout glue and it’s better than the kind they have in school.”

It seemed to suit his purpose very well, for he lowered the stone down into the shaft directly above the precious little envelope. But he had aimed amiss and it settled on a faded scrap of brown paper which he hoisted up. On one side of it was written, “Leave two quarts to-day.” Aged, faded missive of some neighboring housewife to an early milkman.

He tried again, lowering the sticky little stone slowly down, straddling the grating directly above the envelope. And this time the gummy weight settled nicely upon the prize.

“I’ll go home and get washed up and have supper,” cried Pee-wee excitedly; “and I’ll be at your house at seven o’clock, hey?”

Detaching the little envelope from the clinging stone, he took the liberty, in his excitement, of opening it for a reassuring glimpse of the precious tickets. Scarcely had he glanced at them when a look of bewilderment appeared upon his face. He scowled, puzzled, and inspected them still more closely. New York academy of design, they read. In a kind of trance, he read what followed: Tuesday evening, April 16th. Admit one. Exhibition of medieval painting and tapestries.

He looked down into the depths of the shaft which had yielded up these admission cards. “I fished up the wrong envelope,” he said.

“No, you didn’t,” said Emerson.

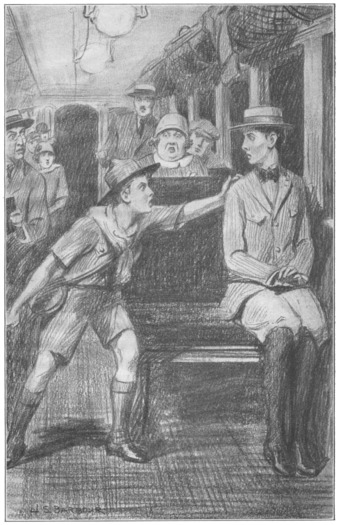

“What d’you mean,” Pee-wee demanded. “Do you know what they’re for?”

“Of course I do,” said Emerson. “They’re for the art exhibition in New York—medieval art.”

“What d’you mean, medieval art?”

“You’ll see when you go.”

“I’ll what?”

“Didn’t you say you’d go? Didn’t you say on your honor? Didn’t you cross your heart?” Emerson asked. “You even said absolutely, positively.”

Pee-wee stood gaping at him. “Didn’t you say they were for the circus? I’ll—I’ll leave it to——” He looked about but there was no one to leave it to.

“I certainly did not,” said Emerson calmly. “I said the exhibition.”

For a moment the entrapped hero paused aghast. “Now I know why you couldn’t get anybody to go with you,” he thundered. “Now I know!”

“You’re not going to back out, are you?” Emerson asked. “You promised to go. Are you going to keep your word?”

“What do I care about medium paintings or whatever you call them?” Pee-wee thundered. “Anyway, besides I have no use for academies or designs or mediums——”

“Medieval,” said Emerson.

“Or that either,” shouted Pee-wee. “Anyway, besides if I made a mistake—you can’t deny you were looking at the posters—let’s hear you deny it because you can’t! I got no use for medium pictures or any other kind. No wonder you couldn’t find a feller. Geeee whiz!”

“Are you going to break your promise?” Emerson inquired with unruffled calm. “You said scouts always do what they promise.”

“If they promise a thing that turns out to be different from the regular thing,” Pee-wee fairly roared, “if they promise—do you mean to tell me medium pictures in an academy are the same as a circus—if they promise do they have to live up to something different just because they weren’t thinking about it when the other feller said—kept back something—can you promise to do a thing that’s kept back when you—geeeeeee whiz!”

“I never said anything about the circus,” said Emerson. “I saw it in Little Valley. I’d like to know whether you’re going to be a—a quitter or not. That’s all.”

“You call me a quitter?” thundered Pee-wee.

“I don’t know what to call you yet, not till I know if you’re going to back down.”

“Well, I’m not going to back down,” said Pee-wee, sullenly.

“Thank you,” said Emerson.

Pee-wee took his way homeward in a mood there is no word terrible enough to describe. His face bore a lowering expression which can only be likened to the awful minutes preceding a thunderstorm. The scowl with which he usually accompanied his famous sallies to his jollying comrades was intensified a hundredfold. He kicked sticks and stones sullenly as he went along. He was in for it and he knew it.

He was to meet the terrible Emerson at the Bridgeboro station for the seven-twenty train into the metropolis unless some just fate dealt a vengeful blow to Emerson in the meanwhile. Emerson had explained that he was to defray all expenses. The only thing which would save Pee-wee now seemed an earthquake or some such kindly interference.

Entering the house, he slammed the front door, stamped upstairs and entered his own room for a few moments’ inspection of his radio before he put on his gray Sunday suit and white collar. He was engaged in this hateful task when the maid called up that Roy Blakeley wanted to see him. And her announcement was promptly followed by the exuberant voice of the leader of the Silver Foxes.

“Hey, kid, come on around to my house to supper. I’m going to blow you to the circus for a birthday present. I’ve got two dandy reserved seats right in front. Come on, Westy’s going, and Warde and Artie and Connie. We’re going to give you a regular birthday party!”

Pee-wee was a good scout, and a good scout is a good loser. He accompanied Emerson to the city and to the exhibit of medieval art. Emerson, having passed his time entirely among his elders, was the kind of boy who enjoyed the things which appeal to grown people. Yet the pictures in the exhibit seemed too much even for him.

“Gee whiz, we might have gone to a movie show,” said Pee-wee, as he followed him dutifully about; “they have dandy ones here in the city.”

“It’s sort of dry, I admit,” said Emerson. “I don’t like it as well as the Metropolitan Museum.”

“Is that where they have skeletons and mummies and things?” Pee-wee asked. “I heard they have mummies of Egyptians there. Did you ever hear of Queen Tut? My sister was going to be Queen Tut at the masquerade only she changed her mind and decided to be—something else. Gee whiz, there’s no pep to this kind of a show. I don’t see anything in those bowls and things.”

“That’s medieval pottery,” said Emerson. “That one looks like a thing the cook baked beans in,” said Pee-wee, alluding to a bulging urn. “Oh, boy, I’m crazy about those, ain’t you? At Temple Camp we have those lots of times.”

“I guess we’ve seen about everything,” said Emerson.