You too can cause earthquakes, munch

high-tension power lines and travel faster

than light—all you have to do is become an

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, March 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

First man to reach the speed of light, I was. But you'll find the good Albert only hinted at the effects, in a delta-theta 2.3 pi-squared way. E=mc2, he said. And for fifty years before they built my rocket, the Lighttrick, slim, tapering, sleek and gy-perpowered, everyone concentrated on turning matter into energy at a light-squared power. Big, bright bangs, and congratulations.

It's a pity no one asked what happens to energy divided by the speed of light. I happen to be the answer to the equation, and by interfering with the motor of this electric typescripter I can give you my thoughts on the matter.

The Lighttrick hit full velocity out there between Van Allen and the asteroids. I'd guess the whole beautiful ship, including me, converted into energy and, slowing down, reconverted on the wrong side, so to speak. And there I was, floating without a ship and surrounded by little round beings, shimmering in a blue haze.

"Good afternoon," I said.

But no sound came out of my mouth. I had a mouth, in a way, but not for talking; and not at all the sort of mouth I used to have. In fact, the shimmering blue haze was me. I could find no other parts of me. And when the little round things touched me on the periphery, there was an intelligent vibration.

"Frequency and tone?" said the vibration. "Please identify."

"You must take me as you find me," I thought.

"Unidentified frequencies and discordant tones requested not to wander in spaceways," vibrated the little round things.

"I'm a man," I vibrated back. "We don't have frequencies. We use frequencies in radio, television, radar and so on."

"Not intelligible."

"Where's my ship?"

"Ship?"

I tried to picture the Lighttrick and the long thin gleam on her hull, the fury of her rockets and the calm ordered keyboard of the control panels.

"Most interesting," vibrated the round things. "Poetic. Very creative. Speculative philosopher, yes?"

They seemed to be grasping the general idea, so I concentrated on an image of myself, square and bearded, staring sternly into space through the ports, in a pioneer manner, observing hitherto unknown planets.

"Most ingenious," my audience vibrated back. "But unlikely."

Then they started vibrating among themselves.

"Senior e minus says...."

"Mush is mush, that's what I say."

"Now, theoretically...."

"I don't vibrate why not. There are more things in positive and negative, Horatio, than...."

"Excuse me," I vibrated.

There was a brief pause.

"Perhaps we should illuminate."

"Please do," I vibrated politely.

They gathered round the edges of my haze and explained. It seemed a very senior e had suggested once that there might, just might, theoretically be side-effects of mush. The little round things were e beings. And "mush" was the accepted term for the static and orbital tracks of electrons in fixed patterns, such as one found here and there in space. But the very senior e, apparently, had speculated that in a certain narrow band of light frequencies mush might possibly give an appearance of "matter"—to coin a word—a kind of condensed or crystalline energy.

"But no one," they vibrated, "ever suggested there might be forms of life based on such 'material' structures. We admire your imagination. Hail bright e! All hail."

A rapid circuit of my haze failed to show anyone else that they might be vibrating to.

"Do you mean me?" I inquired.

"Naturally. Hail, bright e!"

"I'm an e?"

"What else?"

"Very well," I thought. "Perhaps you'll tell me what an e is."

"An e? We are all e beings."

"So you mentioned earlier. But what is an e being?"

"Ah, you are too deep for us. Highly original philosopher, yes. But please get off the spaceway. There is a food flood due."

And they edged me firmly down, and down, to a vast doughnut with a hole in the center.

I ate a piece out of habit. It was insipid and tasteless. But then, a doughnut several thousand miles across must have some drawbacks.

"The pasture is better inside," they vibrated.

So I sank down into the enormous piece of pastry and came out of a couple of inner layers to see a big ball of mush. There was no mistaking it. A vast, tangled, interconnecting mass of tiny points of light. Mush was a good name for it. But here and there on its surface were great rivers of liquor and mounds of food in delectable variety.

I stuffed myself for days, browsing here and there across the surface of the globe of mush.

In fact, I was chewing quietly on an apparently endless streaming ribbon of—well—trout, steak, caviar, you-name-your-favorite food; that's what it was to me. And I happened to bite too deeply. There was a core of this mush stuff inside and, when I bit it, the whole food supply stopped. The stream of entrancing food just disappeared.

And there I was, hovering on a plain of bare mush.

I was brooding on this and belching contentedly with a sort of cracking noise, when the skeleton came driving over the surface of the mush ball. It was in a framework of mush shaped like a jeep but squirting delicious little fountains of liquor in the front, where the engine of a real jeep would have been. I moved over and tasted them. And the whole framework stopped.

"Triple purple hell," said a voice. "The damned thing's broken down again. Wait till I get my hands on that idiot mechanic!"

"Hey," I vibrated. "Where are you?"

"Now I'll have to walk all the way back, I suppose," the voice added.

The skeleton got out of the mush jeep, walked through me and lifted the hood.

"Battery flat," the voice said disgustedly. "Not a drop of juice in it."

I began to feel guilty.

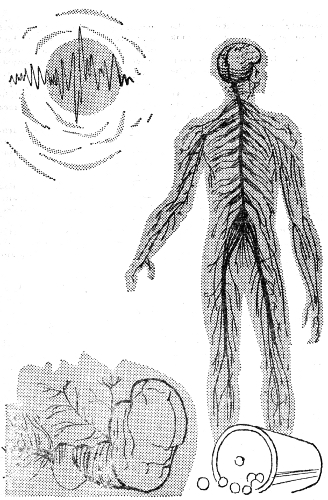

There was a slight blue haze round the skeleton's head. When I examined it more closely, it looked less like a skeleton of bare bones and more like a physician's chart of the human nervous system, traced out in thin lines of mush ... little close-packed lines of energy, fixed in relation to each other but flexible as a whole.

It occurred to me I was looking at a human being, in terms of energy.

And I had just drunk his jeep's ignition!

So thought was a form of energy, after all. For some of the things he was thinking about the mechanic responsible for maintaining the jeep were strictly subliminal and Freudian. If he spoke, I doubted if I would hear him. His voice would just be a very faint wave of mush traveling indistinctly out.

"And the next time that spark-spark foreman sends me out on an emergency power-line repair," continued the skeleton, "he can spark-spark well give me a vehicle that works!"

The skeleton's name was Joe, I think. And I watched Joe sway over to the ribbon of mush I had bitten through.

"Fused," Joe muttered in his head. "Now, what on Earth did that?"

And it struck me for the first time where I was. Back on Earth! As an e being! A being based, it seemed, on energy and not on matter. Converted accidentally by the marvels of modern science and the supreme technological achievement of traveling at the speed of light.

I spat disgustedly at the thought.

"Summer lightning?" Joe bent his mush head back and looked up. He exposed a rather interesting tidbit in the region of his throat plexus and his cardiac nerves were, I regret to say, for an instant very appetizing. But I controlled myself.

After all, in a technological society as free with energy as ours ... as yours ... there were bound to be ample food and drink flowing about.

I swear I had come to that ethical conclusion. It wasn't my fault that I was unfamiliar with my own reactions as an e being. I didn't know I was so fast. I ate Joe by mistake. I just drained off the energy of his system before I knew it. Truly.

Well, naturally I was sorry about it. In fact, I was just standing there, looking at the huddled pile of mush, when the other repair crew arrived. From their scrambled thoughts of death and radio and Main Office, I gathered they were sending for a doctor. Sure enough, he arrived in an autojet with delicious after-burners.

So then they had to send for a team of towing tractors. I just couldn't help thinking about the ignition systems of their vehicles; and to think is to eat, with an e. Or rather, if you have the speed of light—as an e being has—it takes some time before you learn to control your reactions quickly enough.

"Well, I don't know what's going on around here," said a voice which I located as the doctor thinking to himself. "But I remember Professor Bigglesby's advice. When you don't know, nod thoughtfully."

I could see his mush head and its blue haze wobbling solemnly at the other mush-men. I beg your pardon—at the other humans.

"Nervous collapse," the doctor continued in his head. "Something to do with electricity, I suppose. Powerline failure. Broken cable. Dead repair man. Don't know much about electricity. Who does? Hello, hello, what's this?"

I saw him bend his nervous skeleton over Joe's body and straighten up with a string of little silver beads sticking to his hand.

"Makes a noise. Quite musical. Adheres to skin. Light. What is it?"

"There's some more of that stuff in the jeep engine," one of the repair crew noticed.

"And on the doc's jets...."

"And in our truck...."

I watched and gathered I was leaving some form of conversion product around the place. I didn't like that thought. If an e being eats energy as food and drink, what does an e being's conversion product make? The answer might be important ... considering I had just eaten someone.

I decided to follow along. The doctor was wiping the silver beads off his hands into something shaped like a glass jar and screwing on a lid. I thought I had better be around when it was examined.

So I rolled after the towing tractors and carefully refrained from even thinking of their refreshing little spark-plugs and tasty exhaust.

I followed the doctor until we reached a place where the mush grew up in blocks on either side, square and close-meshed, with streams, rivers and trickling lines of energy tumbling through their structures. I gathered we had reached a city of some sort.

The doctor-skeleton got out of the tractor and went into one of the tall blocks of mush through a hole. I followed, nibbling a light bulb or two as we passed down the long corridor inside. The doctor, still carrying the jar shape, stopped once or twice and looked back, then he shot in through a doorway on the left.

"Dr. McPherson," thought a thin skeleton by the window.

"I don't want to say it," said the doctor's mush head, "but this jar of muck seems to have put the corridor lights out."

He held out the jar and I saw a faint wave of mush spreading from his mouth toward the thin skeleton. When the mush wave reached him, the thin man jerked in plain disbelief.

"If I heard that straight, either Doc McPherson is drunk or he's got something very interesting. I wonder which."

The thin man wandered casually over to the jar the doctor was holding and took it.

"Not drunk," he considered, holding the jar up in the air. "But...."

And then his thoughts ran riot in a stream of edibles. He was thinking of electronics, protons, ions, electrons, gamma, delta and alpha particles, and I couldn't resist it. I'm sorry. I just had to eat him, his thoughts were so delicious.

Doctor McPherson stared down at the thin body on the floor and walked out of the room. He left the jar where it had rolled on the floor of mush.

I was quite happy. It must have been a laboratory of some sort. There were refreshing sources all over the room.

I was still tasting and testing here and there when the doctor returned with another pair of mush-men—humans, I mean—and they had a long conversation in their heads about the late scientist and the contents of the jar. Finally, they picked up the jar with a long rod of static energy—some metal, I suppose. They took it away.

Unfortunately, this time it seems I had eaten a physicist working for the government. More and more mush shapes of humans clustered round Doctor McPherson, and one came hurrying up from another laboratory.

"Raw ozone," he thought as he came. "This fellow needs watching. Couldn't get ozone like that except in space. And now he happens to be around when we lose our top physicist. And that's the second accident of the day. Yes, sir, this McPherson needs watching! You can never tell where sabotage will break out."

He grasped the doctor's arm and said something in a faint wave of mush that I could not see clearly enough to understand.

"Me? Ridiculous! I was just...." thought McPherson. But he shrugged and turned away.

Well, I couldn't leave him in a mess like that, so I followed Doctor McPherson home.

I had to explain. But how?

And there was the problem. How can a being based on energy, like me, communicate with a being based on matter, like him?

Obviously, I had to signal in some way, give some signs of life that would be intelligible to him.

He was sitting in a chair-shape of strand energy interwoven together, and he was thinking gloomy thoughts. He flicked on the televiewer. And there was the answer.

I found the input flow, followed it into the cathode tube and ate the pictures off the screen in a discriminating manner.

They were too small and scattered to make a mouthful, but that wasn't the point. I was able to signal to him! I ate pieces of the picture coming through and left regular black holes on the tube face, dot, dash, dash-dash-dot.

Doctor McPherson stood up, approached the set, reached in his pocket for a bottle and took two pills. And then he switched off the set and went to bed.

"Now my eyes are playing up. Liver," his thoughts trailed away.

After awhile, I saw a better answer. One man would be scared to do anything even if I did get in touch with him. What I needed was a larger scale. If several dozen mush ... several dozen people started speculating about me, they would lend each other moral support and they would start looking for my signs. Then I could tell them all about the little error of appetite.

So I went back down the main power line from Doctor McPherson's home—high grade, pure liquor in that line!—and tracked it upstream to the city power house. But when I took a deep bite, all the generators stopped and an auxiliary circuit from somewhere else started up.

I ate a piece of main coil in disgust.

Well, that was no use. And then I remembered the little e beings' comments on a food flood due in the spaceway. A sunburst, no doubt. A magnetic storm on the sun would certainly send a harvest out through space for e beings. But it would louse up the planetary radio system.

And there I had an answer. All I had to do was remove the radio interference in a planned way and every receiver on half the world would receive my signals. How easy it was!

So I went back up to the first layer of the doughnut round the Earth where there was a field of fresh energy. As the food came flooding in from the sun I gobbled it up. Mouthful. Pause. Mouthful, mouthful. Pause. Mouthful, mouthful, mouthful. Pause.

I worked up and down the numbers in progression, swallowing every lump of solar radiation within reach.

But I guess I was carried away by the enjoyable eating. A lot more time passed than I had intended; and when I came down again to read a few thoughts, the world was freezing in parts, and the sea was boiling in others, and the mush lay flat as a desert in wide patches.

I worked it out, eventually. No energy means no evaporation, thus no clouds and no rain for vegetation. And that means no carbon dioxide layer to protect the planet, in turn leading to excessive radiation when I stopped eating, hence deserts and a boiling ocean and parts of the land frozen solid.

Not a very good message.

Well, I cleaned up as best I could, but it was drudgery sipping up the dull, flat-tasting thermal energy of the oceans. Tidal forces and magnetic flows are stodgy, uninteresting diets. You might as well eat straight mush.

I decided not to try that again. It had too many repercussions. What I wanted was a nice simple signal.

A volcano would do excellently, I thought—Indian smoke signals on a vast scale.

So I hunted over the mush until I came to a reasonably active fountain, probably Vesuvius but I'm not sure; one blob of mush looks like another. And I drank the whole internal fire in bursts. Anyone with any sense could have seen the Morse-coded eruptions that I let go through.

But they didn't.

They missed my signals altogether. Chiefly because I had disturbed the balance of stresses down at the foot of the volcano, deep in the mush, and when I came out it was dancing about in ripples and shakes. I don't suppose many people would stop in the middle of an earthquake to note the signals coming out of the local volcano. Anyway, no one did.

As you know, the damage was quite widespread. So I went round to the other side of the mush, where they were less distracted. What I needed was a test-piece. Something which was already the focus of serious scientific interest. Something being carefully observed already.

The nuclear power plant in the nearest city mush-blocks seemed a reasonable choice. And good eating it made, too. Pure unadulterated flavor, strong and pulsing with vitality. I've never had a better meal.

But when I came out of the reactor and let it continue its food ... its energy production, all the humans had vanished. They hadn't seen a thing. I found them miles away under the surface of the mush-level expecting to be blown up. They assumed that when the pile ceased its output it was building up internally, so they broadcast an emergency and took to their bunkers. And then they were busy for weeks correcting the false alarm and dealing with complaints from freezer companies and householders and utility commissions. So I left the area to sort itself out.

Very well, I thought. This time, I'll choose a nuclear device that is expected to explode and eat it before it does, while everyone is watching.

It wasn't difficult to find. There was a long smear of food in the air all round the world, as if a lot of clumsy e eaters had dribbled. The main source was easy to locate.

I found a long stalk thing of mush and a mush shed on top and sat there waiting. Eventually, a team of mushes hoisted up a device with delicate little tidbit cores, and hurried away. So this was a fusion bomb, was it? I waited until it was triggered off, took a strong hold and ate the lot at the moment of burst.

For the record, swallowing a nuclear explosion is not very comfortable. I had indigestion for weeks. But I made it.

It was a waste of time.

As usual, I had overlooked something. The conversion was as massive as the energy I ate, and I found out what the silver beads Doctor McPherson had put in the jar were. Energy eaten by e beings converts into sound and ozone. And the conversion of the nuclear explosion sent great balls of sound rolling over the country, deafening the people, flattening structures by vibration, and releasing flows of raw ozone, which promptly started fires; and that in turn disturbed the cloud masses and produced unprecedented floods.

I was munching quietly on a power line, overlooking the great stretch of level mush of water up to and over the horizon, when Doctor McPherson found me.

A repair man drove him up, let him off the mush vehicle and drove off fast.

"You nutty old coot, you wanted to see the next breakdown and here it is," the repair man's thoughts shot away.

"I may be nuts," Doctor McPherson said to himself, standing underneath me, "but I have an odd idea there's intelligent mischief behind all this."

He sat on a rock-shaped mound of mush nearby.

"So here I am, following a idiotic hunch," he thought, and held out a large jar with a most entrancing tidbit of radioactivity, cobalt flavor, in the bottom.

Naturally, I went down happily and gobbled it up.

And Doctor McPherson put the lid on. A lid of thick-meshed mush, leaden and inedible. It took me some time of fruitless revolving to discover I was locked in a Leyden jar with a complicated series of non-conducting layers.

I'm starving.

Oh, he feeds me now and then, and the other day he put in a one-way circuit so that I could operate this electric typescripter.

But he says I can't come out until war is declared and the Pentagon signals him on emergency. Then he'll take the lid off and I can eat the nearest rocket heading this way. He's promised me that.

He needn't worry. I'm so hungry I'll eat the lot. But who wants to be a secret air defense weapon locked in a Leyden jar?

Fellow e, keep away from this mush and these mush-men! They are dangerous.

What's more, they have no finer feelings!