TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

These lectures each had a set of associated slides, a complete list of which can be found on pages 143–152 at the end of the book. These slide sets were sold separately and are not part of the book. Some of the slides (those highlighted in bold in the slide list) were inserted as illustrations in the original book, and these are reproduced in this etext.

The numbers in the right margin of the etext are the numbers of the associated slides. Several of these margin slide numbers are in parentheses ( ) to indicate that this particular slide is being shown for a second time at this point in the lecture. These margin slide numbers, like the page numbers, are only displayed on browsers; they are not displayed on handheld ereader devices.

If the window viewing size is made very wide, some slide numbers might be overlaid on the next one; keeping the text width less than 120 characters should avoid this.

The original book showed all the slide numbers as sidenotes in the outer margin of the text. These are not displayed on ereaders, but can be viewed in the .htm and .txt versions of the etext.

There are no Footnotes in this book.

The original cover image has been slightly modified. It had damage in the top left corner. This section of the cover image has been overlaid with a rotated version of the top right corner section. This modified cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

EIGHT LECTURES

Prepared for

The Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office

by

A. J. SARGENT, M.A.

LONDON

GEORGE PHILIP & SON, Ltd., 32, Fleet Street

Liverpool: PHILIP, SON & NEPHEW, Ltd., South Castle Street

1913

(All rights reserved)

THE VISUAL INSTRUCTION

COMMITTEE

APPOINTED BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE COLONIES

The Right Honourable the Earl of Meath, K.P., Chairman.

The Right Honourable Sir Cecil Clementi Smith, G.C.M.G.

Sir John Struthers, K.C.B., LL.D., Secretary to the Scotch Education Department.

Sir Charles Holroyd, Director of the National Gallery.

Sir Philip Hutchins, K.C.S.I., late Member of the Council of the Secretary of State for India.

Sir Everard im Thurn, K.C.M.G., C.B., late Governor of Fiji and High Commissioner for the Western Pacific.

Sir Charles Lucas, K.C.B., K.C.M.G.

Dr. H. Frank Heath, C.B., of the Board of Education.

A. Berriedale Keith, D.C.L., of the Colonial Office.

H. J. Mackinder, M.P., lately Director of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

W. H. Mercer, C.M.G., Crown Agent for the Colonies.

Professor Michael E. Sadler, C.B., LL.D., Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds.

A set of Lantern Slides has been prepared in connection with this book, and is sold on behalf of the Committee by Messrs. Newton & Co., 37, King Street, Covent Garden, W.C. (late of 3, Fleet Street, E.C.), from whom copies of this book can be obtained. The complete set of 489 Slides may be had for £39. The Slides to accompany the several Lectures will be sold at the following prices: First Lecture, £4 3s.; Second Lecture, £5 5s.; Third Lecture, £4 12s.; Fourth Lecture, £5 9s.; Fifth Lecture, £4 13s. 6d.; Sixth Lecture, £5 12s. 6d.; Seventh Lecture, £5 5s.; Eighth Lecture, £5 4s. The Slides will also be sold in sets in which the maps alone will be coloured. The prices in this case will be—for the complete set of 489 Slides, £25 10s.; First Lecture, £2 17s.; Second Lecture, £3 6s. 6d.; Third Lecture, £3 5s.; Fourth Lecture, £3 10s.; Fifth Lecture, £3 7s. 6d.; Sixth Lecture, £3 7s. 6d.; Seventh Lecture, £3 7s. 6d.; Eighth Lecture, £3 5s. The Slides sold on behalf of the Committee may now be purchased separately in batches of not less than two dozen.

The Slides in this Series are Copyright.

PREFACE

These Lectures, like the last series, have been written for the Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office by Mr. A. J. Sargent, and have been revised at the offices of the High Commissioners for the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand. The lecture on the Pacific has been revised by Sir Everard im Thurn. The slides are derived from pictures painted and photographs taken by Mr. A. Hugh Fisher on behalf of the Committee, supplemented by photographs supplied from various sources. The Committee wish to acknowledge the great help which they have received from the High Commissioners and Agents-General and their staffs in the matter of slides, and in addition their acknowledgments are due to, among others, the Honourable Victor Nelson Hood, the Agricultural Departments of Queensland and Western Australia, the Secretary to the Commissioner for Queensland Railways, and the Government Geologist of Western Australia.

Meath.

November, 1912.

PUBLICATIONS OF THE VISUAL

INSTRUCTION COMMITTEE

A. Seven Lectures on the United Kingdom.

By Mr. H. J. Mackinder.

In the following Editions issued on behalf of the Committee by Messrs. Waterlow & Sons, Ltd.:—

In use in Ceylon, the Straits Settlements, and Hong Kong.

2. Mauritius Edition, June, 1906.In use in Mauritius.

3. West African Edition, Sept., 1906.In use in Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, and Southern Nigeria.

4. West India Edition, Sept., 1906.In use in Trinidad, British Guiana, and Jamaica.

5. Indian Edition, March, 1907.In use in the following Provinces:—Madras, Bombay, Bengal, the United Provinces, the Punjab, Burma, Eastern Bengal and Assam, the Central Provinces, the North West Province, and British Baluchistan.

6. Indian Edition, for use in the United Kingdom, Jan., 1909.B. Eight Lectures on India.

By Mr. H. J. Mackinder.

Published by Messrs. George Philip & Son, Ltd., 32, Fleet Street, London, E.C., price 8d. net in paper covers, or 1s. net in cloth.

[A Lecturer’s Edition has also been issued, price in cloth, 1s. net, and may be had of Messrs. Newton & Co., 3, Fleet Street, E.C.]

Six Lectures on the Sea Road to the East.

By Mr. A. J. Sargent.

Eight Lectures on Australasia.

By Mr. A. J. Sargent.

Published by Messrs. George Philip & Son, Ltd., price 8d. net in paper covers, 1s. net in cloth.

[In these two books the ordinary edition and the lecturer’s edition are combined.]

| LECTURE I | |

| PAGE | |

| Australasia | 1 |

| LECTURE II | |

| New South Wales, with Papua | 17 |

| LECTURE III | |

| Queensland | 36 |

| LECTURE IV | |

| Victoria and Tasmania | 51 |

| LECTURE V | |

| South Australia and Western Australia | 67 |

| LECTURE VI | |

| New Zealand—South Island | 84 |

| LECTURE VII | |

| New Zealand—North Island | 103 |

| LECTURE VIII | |

| Fiji and the Western Pacific | 122 |

NOTE.—The reader is asked to bear in mind the fact that these lectures are illustrated with lantern slides. The numbers in the margin of the text are the numbers of the slides, of which a complete list will be found on pp. 143–152.

For nearly two thousand years the existence of a great Southland, in the ocean of the southern hemisphere, corresponding to the land mass of the Old World in the northern, was a matter of doubt and dispute among geographers. In the sixteenth century, this land begins to appear vaguely on globes and charts; possibly the information was due to the Malays and Arabs, who were skilful sailors and made long voyages in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. It has been thought that the Portuguese, approaching the Malay region from the west, while the Spaniards came from the east, may have been acquainted with the northern coast of the new continent; since they certainly had some knowledge of the northern coast of New Guinea early in the sixteenth century. But our first definite information may be said to date from the beginning of the seventeenth century, when a Spanish exploring expedition, under de Quiros and de Torres, sailed across the Pacific and discovered the New Hebrides group. One of the islands they named la Australia del Espiritu Santo, under the idea that it formed part of the great southern mainland. De Quiros then sailed back to Mexico, but Torres continued his voyage northwestward through the straits which still bear his name, and so to the Spanish Possessions in the Philippines.

But the day of Spain as a sea power was passing away, and it was to the Dutch traders that the western world owed its first real acquaintance with Australia.[2] The early discoveries were often accidental and did not lead to settlement or regular intercourse with the natives. This was due partly to the backward state of the science of navigation, partly to the fact that the voyagers on long expeditions usually lost from half to three-quarters of their crews from disease. The Dutch had the advantage of a local base, as they were already firmly established in the East Indian Islands; so that Australia was really discovered from the Indies.

Trade, not exploration, was the main motive of the Dutch. So, in the early part of the seventeenth century, trading ships were dispatched from Batavia by the Dutch East-India Company to explore the north and west coasts of Australia.

We find all along these coasts the names of the ships still surviving, as in Arnhem Land and Cape Leuwin; those of the captains, as in Dirk Hartog Island, Houtmans Abrolhos, Edels Land and Nuyts Land; while the Gulf of Carpentaria is a memorial to Peter Carpenter, the then Governor of the great trading company.

The most important voyage of all was that of Abel 1 Tasman, in 1642. He started from Mauritius, to discover a passage south of the Australian continent; and after landing in Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania, he sailed across the Tasman Sea and up the west coast of New Zealand, and so back to Batavia by way of Tonga and the Fiji islands and the north coast of New Guinea. He left behind him another name, New Holland, for the whole continent.

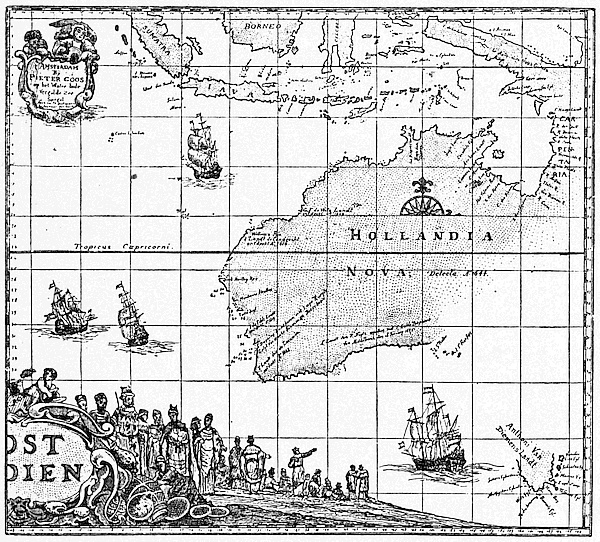

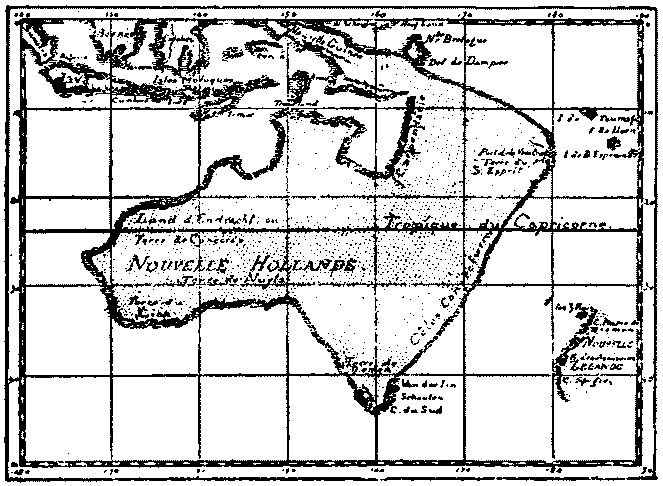

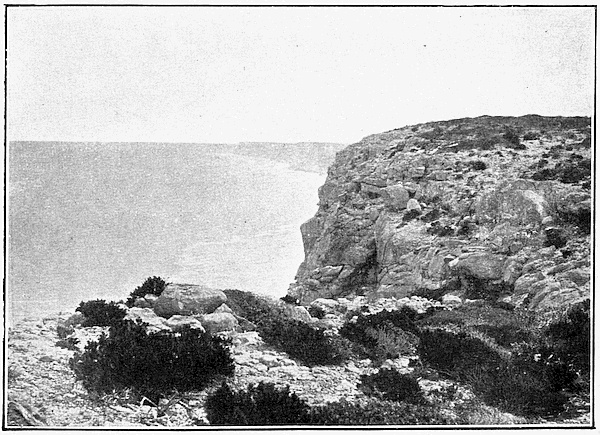

These names throughout Australasia bear witness to the skill and energy of the Dutch navigators; but they came only as traders, and the west coast of Australia, which they knew best, had little to attract them to permanent settlement. Sand and grass, hostile natives, and dangerous reefs marked by a series of shipwrecks sum up their impression of the new land. Here are [3] 2,3 two views of the coast; it does not seem attractive for sailors. We can quite understand why they made no effort to open up a trade like that of the East Indies, especially as they missed the east coast, the most promising region for European settlement. Here are two charts showing our knowledge of Australia, the first soon after Tasman’s voyage, the second nearly a century later. 4,5

The discovery of the east coast was to come more than a century later; it was made by an Englishman, at a time when England was looking for new outlets, both for trade and settlement, as an offset to her losses in the continent of North America. It is true that Dampier visited the west coast towards the end of the seventeenth century, and wrote an account of the animals, natives, and plants; but he does not seem to have been much[4] more favourably impressed than the Dutch, and nothing came of his visit.

But in the eighteenth century England and France were the great rivals in colonisation, and voyages of discovery and plans of annexation became the order of the day. It was a revival, in a less forcible though more scientific form, of the old rivalry with Spain and Portugal in the sixteenth century. State influence was behind the explorers, as it had been in the days of Drake and his freebooters. Captain Cook sailed in a ship belonging to the Royal Navy, and not in a trader. In our own country his memory is still kept green in the little port of Whitby where he served his apprenticeship to the sea, and where the ships were built in which he made his great voyages of discovery; in the Antipodes it is for ever associated with the beginnings of a great and growing Empire. Here we 6,7 see his statue in Sydney, and here is a picture of his ship, the Endeavour, approaching New Zealand.

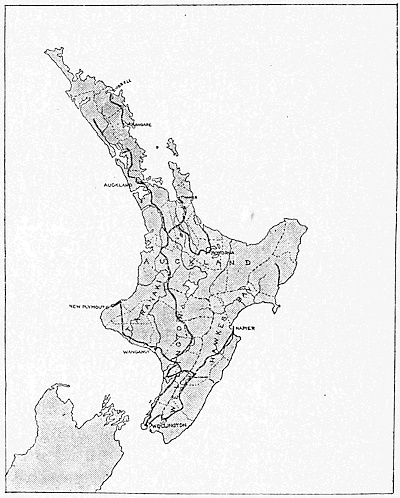

Cook came westward, across the Pacific, with an expedition in 1769, to observe the Transit of Venus at Tahiti, and then sailed south-west to New Zealand. [5] 8 He sighted land at Poverty Bay and sailed south as far as Cape Turnagain; then he went right round the North Island and through Cook Strait, until the Cape was again sighted, scattering English names and charting the coast as he passed. Next he circumnavigated the South Island, steering outside Stewart Island, which he imagined to be a peninsula; and so to Cape Farewell, in the north-west corner of South Island. He had obtained a fairly accurate idea of the nature of the coast, and had proved that New Zealand was not connected with the supposed Antarctic continent.

From Cape Farewell he struck westward, and sighted the mainland of Australia at Point Hicks, on April 19th, 1770, but failed to discover Bass Strait. From Point Hicks Cook sailed along the whole of the east coast to Cape York, giving to the bays and capes as he passed them the names of his crew, of British admirals, officials and politicians of all kinds at home. At various landing places he came into collision with the aborigines, and at Endeavour River he stayed for two months to repair his vessel which had been damaged through striking on the rocks. Finally, before sailing westward through Torres Strait, he landed on Possession Island and formally claimed the whole region discovered for the British Crown.

When, in 1798, Flinders and Bass proved that Van Diemen’s Land was an island, the rough work of discovery was complete. Australia, New Zealand and many of the smaller islands were known and charted, and the discoveries of the Spaniards and Dutch were linked up, by the aid of a great deal of miscellaneous exploration carried out by the French navigators who followed us in the South of Australia, in New Zealand, and in the islands of the Pacific.

The navigators, French and English, were in the habit of formally annexing the country wherever they landed; but annexation of this kind was of little value[6] without effective occupation. This was to come later, during the course of the next half century. From 1800 onwards, we may say that the different parts of this vast region begin to have a separate and individual history and development, though behind all are the conditions common to most of the area, conditions which distinguish it sharply from the rest of the world even to-day, in spite of minor differences between its separate parts. There is ample room for variation, since the continent of Australia is about three-quarters the size of Europe, or seven times the area of Germany and France together; and it includes nearly every type of temperate and tropical climate.

Whether we look at the animals, plants, or aborigines of Australia, we are at once struck with the fact that they belong to an entirely different order of life from that which we find in the other great continents. The whole region seems, from a very early age, to have been cut off effectively from the rest of the world, and to have developed along lines peculiar to itself; though since the advent of the white man we have the artificial introduction of European and other plants and animals, which bid fair in many cases to oust the native products, just as the white man has displaced the original inhabitants.

The first animal which we naturally think of in connexion with Australia is the kangaroo. His family 9 is large and varied, from the giant standing six feet high, and dangerous to attack, to the dwarf measured 10 by a few inches. He is a creature of the wide open plains, living on grass, though in Queensland and New Guinea are to be found some which climb the tall gum trees and feed on their shoots. An ancestor of the present kangaroo, whose remains have been discovered, was a formidable monster standing twelve feet high.

The kangaroo is merely the best known representative[7] of a very large group, the marsupials or pouched animals. Closely allied to the kangaroo is the wombat, a clumsy badger-like animal which feeds on leaves and burrows in the ground; he is quite harmless, though, like the kangaroo, he had a huge ancestor who seems to have been as large as a rhinoceros. The bandicoots, ratlike burrowing animals, are his cousins many times removed.

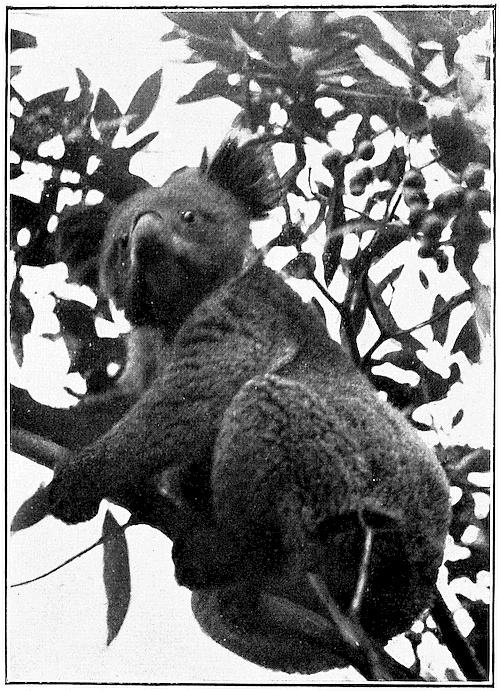

Next we have a group which looks very different but is really closely allied to the kangaroo: the phalangers, or opossums, as they are commonly called. The 11 name is adopted from America but is applied in Australia to the wrong group, as we shall see later. Nothing is more misleading than the names given by white settlers, ignorant of botany or biology, to native plants or animals, generally on the ground of some fancied and superficial resemblance. The so-called opossums are found all over Australia and New Guinea and in many of the islands of the Pacific; but owing to the value of their fur they are becoming scarce in many districts. They live in trees, and some of the family have their legs connected by a membrane, so that they can glide from one branch to another. Hence the name flying squirrel; though they do not fly and have no connexion with the squirrel which we know. Here is another of the same group, the koala, or native bear; though he again has nothing to do with bears. He is a sleepy-looking 12 animal, with no tail, and is not given to leaping or gliding; though his claws are useful for 13 climbing the gum trees in which he lives. He is quite harmless, and a child can play with him, as we see here.

Other members of the same great family are far from harmless: among them are the dasyures, or native cats, with dark bodies mostly spotted with white. Some smaller members of this family are called weasels and mice. To this family belongs also the Tasmanian Devil,[8] 14 whose portrait we have here; he is very fierce though small. A larger animal, the size of a retriever, is the so-called Tasmanian wolf; he is carnivorous, while most 15 of the marsupials are vegetarian. It is rather doubtful whether he should be classed with the rest or go by himself.

The only existing allies of the marsupials of Australia are to be found in the opossums and some other less known animals of South America; but the opossum of South America resembles less his Australian namesake than the other group, the dasyures. In Europe and Asia the marsupials existed, but only in very remote geological ages, as their remains prove. It has been argued from the existence of the opossum family in America that at some time there must have been a land connexion between Australia and South America, either by way of the islands of the Pacific or by an Antarctic continent. But the isolation of Australia must have been very ancient, since it has given time for the development of the enormous differences which we have seen among the individuals of the same family.

Even these strange animals, old as they are, are not the most primitive to be found in Australia. The ornithorhynchus or duck-billed platypus lives in a 16 burrow by the river; it has teeth when young, but seems to lose these as it grows up. It is said to lay eggs like a reptile, though it is a true mammal. We are not surprised to learn that when the first stuffed specimen of this strange beast reached Europe it was thought to be a fraud, put together to deceive the ignorant and unwary. Another of these egg-laying animals is the echidna, or spiny ant-eater, which has a kind of beak for burrowing and a long sticky tongue to capture its prey. It has sharp spines and rolls itself into a ball like a hedgehog when attacked. In addition to these curious animals there are rats and mice[9] and the dingo, or native dog, of a type more familiar 17 to us. It is thought possible by some that the dingo, being so different from the other native animals, was introduced by man at some very early date.

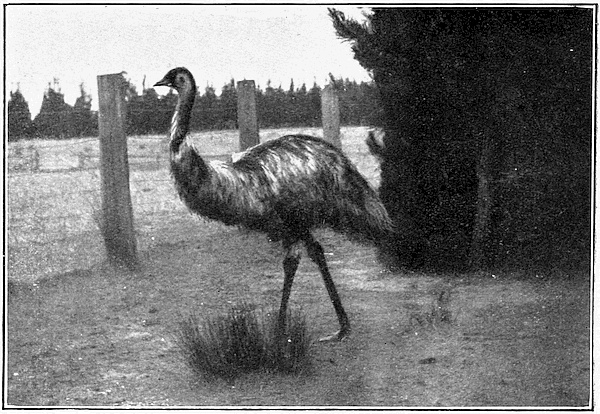

The typical Australian animals disappear as we travel away through the islands to the north, and the boundary line between Australia and Asia is usually drawn through the strait between Bali and Lombok, and then on between Celebes and Borneo; though it is much disputed whether Celebes belongs to the one region or the other. The division is only a narrow water strait, and we can understand that Asiatic birds would have no difficulty in crossing. On the other hand, as there is no great land mass to the south, there are no crowds of seasonal migrants from cooler regions, such as we find in the warmer countries of the northern hemisphere; so that the existing Australian birds are for the most part allied to the bright-coloured 18 inhabitants of the tropics to the north. Some are peculiar to the region, such as the lyre birds with their 19 wonderful tails, the emu, and the brush birds which bury their eggs in a mound of earth, leaving them to be hatched by the heat of the sun. Other birds, as the honey-eaters, though common in Australia, are found also in the neighbouring islands of the Pacific. Unfortunately, not content with the flowers of the 20 gum trees, these birds now attack the fruit in the orchards and are becoming a nuisance in some districts. Finally we have the kukuburra or laughing-jackass, 21 one of the most popular and best known of all Australian birds. It belongs to the kingfisher tribe and is said to be a great destroyer of small snakes. Nor must 22 we forget the black swan, one of the most striking and beautiful of all, and still to be found in large numbers in the lakes of Gippsland and in West Australia.

Then we have lizards, snakes, and strange fish of all kinds, some peculiar to Australia, others, like the[10] animals, allied to species found in Asia or South America. All the evidence afforded by the animal life of the continent points to a very remote connexion with the other continents, followed by a very long period of isolation during which the families of animals developed wide differences among themselves, together with special peculiarities suited to the conditions in which they lived.

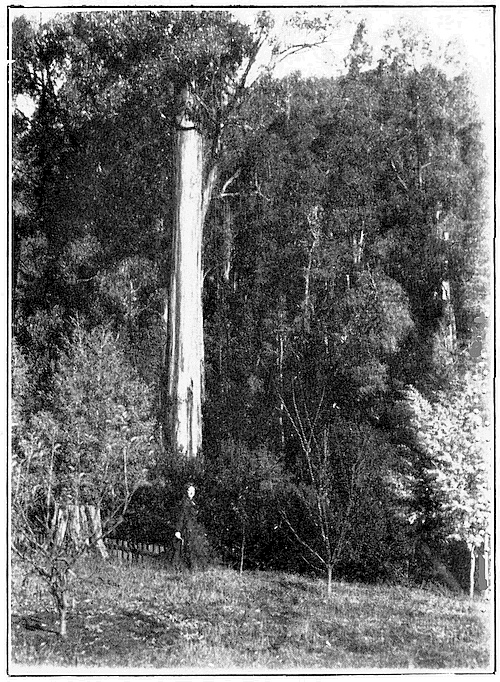

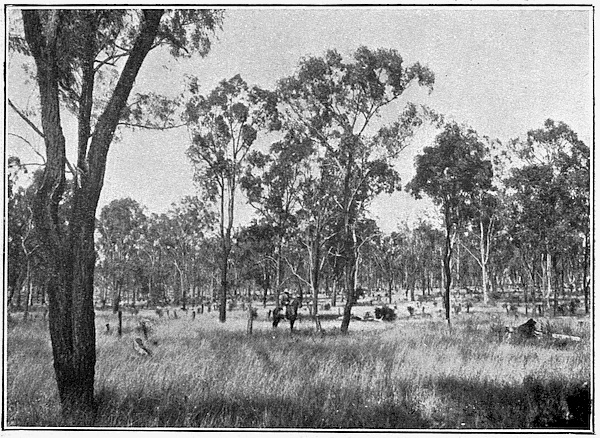

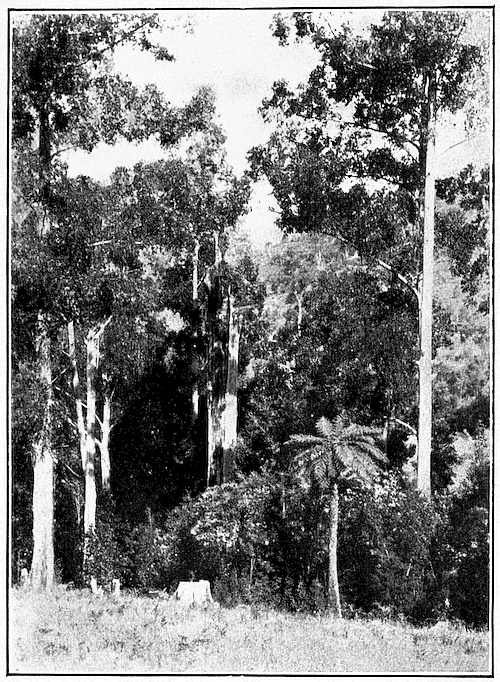

Now let us turn for a moment from the animal to the plant life of Australia. In the tropical parts of Queensland there are many plants which belong to the Malayan region as a whole; this we might expect. We may see palms growing even at Brisbane; while 23 further north they form a dense forest, thoroughly tropical in appearance, with its creepers and undergrowth, as we see in these two pictures. But further 24 south we meet more species peculiar to Australia, in the vegetable no less than in the animal world. 25 The typical Australian plants are those specially adapted to resist hot sunshine with drought, and often sudden changes of temperature. All over the continent the gum trees give a special mark to the landscape 26 of the forest. The leaves hang vertically, so as not to give a large exposure of surface to the hot sun, and are collected in dense clusters for the same purpose of protection; so that we miss much of the spreading shade of our English trees. The leaves, too, are alike on both sides, and the colour is more uniform than in our own trees, nor do they change colour and fall in autumn, but decay gradually on the stalk. The bark of many of the gums hangs in strips, thus spoiling the appearance of the huge trunk, for huge it is, rising to four hundred feet in some species. Owing to the character of the foliage the forests are more open than our own, except in the wetter parts where there is a dense undergrowth of fern and creeper. These districts are always near[11] the coast. As we travel away from the coast the forest thins out, except along the watercourses, and becomes 27 smaller and more stunted. In place of trees with leaves we find thorny scrub of various kinds, such as the 28 mulga, whose leaves are replaced by woody spikes still more resistant to drought. Finally we reach the salt-bush 29 and spinifex and wiry grasses of the desert interior. Often there is little but bare rock as in the 30 pictures before us. The watercourses themselves may dry up in the hot season, leaving a desolate expanse 31 of sand and stones, but the line of trees still marks the presence of moisture below. 32

The huge gum trees are, as a rule, the main feature in the forest landscape, but this is varied by curiosities like the grass tree and the bottle tree; while in the moister regions, as in the forests of Gippsland, we find 33 beautiful tree ferns of every kind. Here are specimens of grass trees and gums. Everywhere we 34 find the acacia and the wattle with its sweet scent, the banksia shooting up into great trees, and the 35 beautiful waratah; everywhere, too, where the rainfall is sufficient, flowers of the same order as those with which we are familiar in Europe grow in great profusion.

So we see that there is great variety of vegetation in Australia, though the only native plants of much use to man are the gum trees, which we value for their dense hard woods. All else that is of value, both among plants and animals, has been introduced by the settlers, and many of the native types seem doomed to extinction.

We may now be able to understand why this country of strange plants and animals had no attraction for the Dutch trader, especially in the drier west; in fact, it could have no trade until it had been settled by Europeans bringing with them European crops and animals. In India and Malaya there was already a[12] basis for trade in some of the natural products of the region; while the natives were sufficiently advanced in civilisation to make commercial intercourse possible. It was far otherwise in Australia. The aborigines, as we found them, were as primitive as the plants and animals. They are not black, but a dark-brown people, and their hair is waved and silky, not curly like that of the negro. They are different also from the negro in the shape and build of the head and face. There are various theories as to their origin, but the nearest correspondence seems to be in some of the ancient hill tribes of India and the Veddas of Ceylon. At any rate they are quite different from the Malays, and equally also from the now extinct Tasmanians. The Tasmanians had woolly hair, and perhaps represented the remnants of an earlier and even less developed race than the invaders from the north.

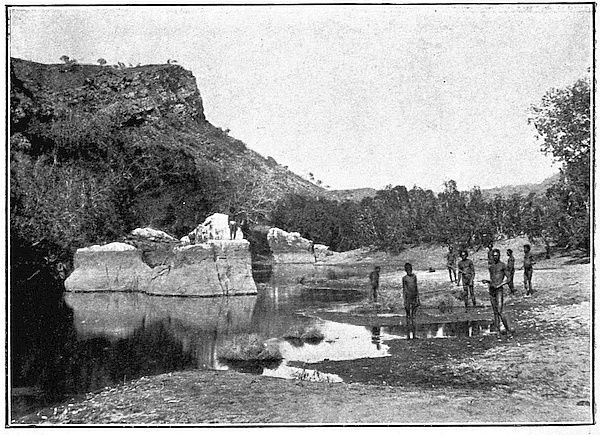

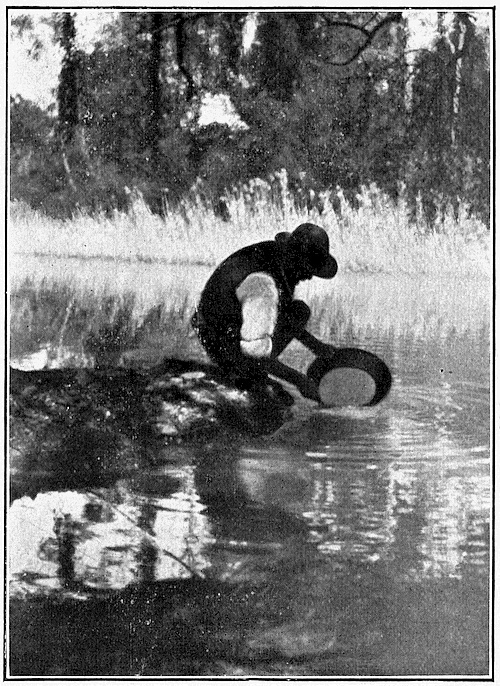

The native Australian, as the first European discoverers found him, was not an attractive being. He was looked on as little better than a wild beast and treated as such. This was partly due to ignorance of his language and customs. His mode of life was fitted by long adaptation to the peculiar conditions of his surroundings. He had developed no agriculture in his new home; not without reason, if we think of the agricultural possibilities of the country in the hands of a rude and backward people. He was equally without any of the useful animals, and had no means of procuring them. So he was reduced to the nomad life and to the utilisation of the wild roots and plants of the country and such small game as he could kill with his rude weapons. He was necessarily a hunter, with a temporary shelter for his home, often an overhanging 36 rock as in this picture; and civilisation does not grow up in such conditions. Here we see some natives 37 fishing, and here again are some armed men scouting in the bush.[13] 38

The hostility of the native to the European colonists often arose from their interference with his natural food supply, or to their careless ignorance of his semi-religious ideas or customs, such as the tabu.

His only possible clothes were the skins of animals, and his weapons and tools all belonged to the Stone Age. The axe, knife, and hammer were in universal use, and long journeys were made to obtain the right kind of stone. This involved a certain amount of intercourse among the tribes. For weapons of offence the native had the club, and the spear tipped with bone or stone; while some tribes used a special spear-thrower. The boomerang was a curved bar of heavy wood, often five or six feet long, which was used for killing or stunning at a short distance. The smaller boomerang, which returns to the thrower, was merely a toy and used in sport; here we see it in use. The stone implements are 39 all similar to those which are dug up in Europe, the relics of the Neolithic Age of man. One of the chief uses of the axe was to cut notches for climbing trees, in search of honey among other things; though they had 40 another method which we see here.

The natives were divided into tribes and sub-tribes, and had some form of tribal government, under headmen. In the south-east of the continent these chiefs had considerable authority and were sometimes treated by us as representing the tribe. Here is one of them, though he does not look imposing in his European dress. 41 They had an elaborate social system and curious marriage customs about which the learned still dispute. They had a strong belief in spirits of various kinds, though it could hardly be called a religion, and a whole series of tales and legends handed down orally, some of them showing considerable power of imagination. 42 They even had the beginnings of some ideas of art and ornament, as we can judge from the crude paintings 43 shown here.

The most interesting of their social customs was the corroboree, a great gathering for feasting and dancing, 44 often combined with some religious or social ceremony. Such meetings represented the only real social intercourse of the people and tribes, except messages by ambassadors who were sacred everywhere.

On the whole, then, they were not so low in the scale of civilisation as the early observers imagined. Even the language, with its many dialects, due to the absence of writing and the nomad life of the people, is elaborate and inflected like those of Europe.

The native life in its original form is decaying, and survives chiefly in the interior and the west. Wherever white occupation has extended, the native is dying out; in fact, in some parts he survives only on the Government 45 Reservations. Here are some of these survivors in Victoria. Here again, in Queensland, we see the 46 native converted to European clothes, though he does not seem very comfortable in them. In this district, 47 as in South and Western Australia, and the Northern Territory, they still exist in considerable number; but it is probable that there are less than 100,000 in all in the Commonwealth. In the census of 1911 an attempt was made to count them, and some 20,000 were found to be living in or near white settlements; only a vague estimate was possible in the case of the tribes of the interior, who still live their nomadic life in the more inaccessible parts of the country. But the area untouched by the white man grows smaller every year, and unless the native can change his character greatly, he is likely to die out in the north and west as in the south-east. In 1911 there were only about two thousand in New South Wales, hardly any in Victoria, and none at all in Tasmania. It was inevitable that the Australian native should be displaced from his hunting grounds. An area about equal to that of the United States could not be left in the sole occupation[15] of a few thousand savages. Now, instead of the savage with his primitive tribal system, we have a white race, purely British in origin, with industry and agriculture of the most advanced type, and an elaborate political constitution of federated States. It is the utilisation, by the white man, of the resources of this vast area which we must study.

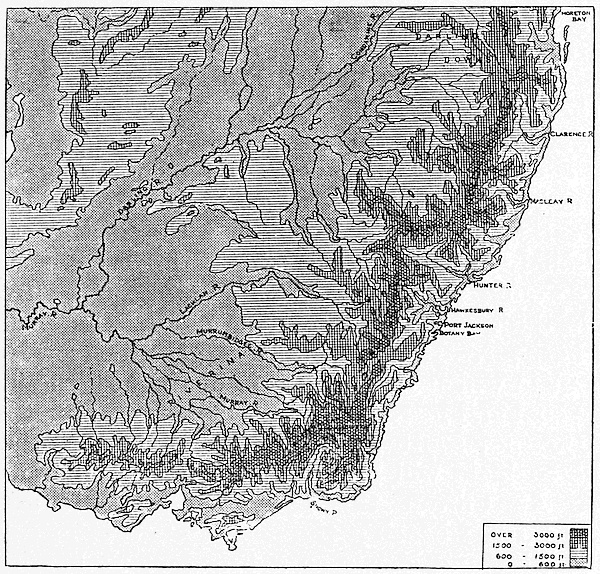

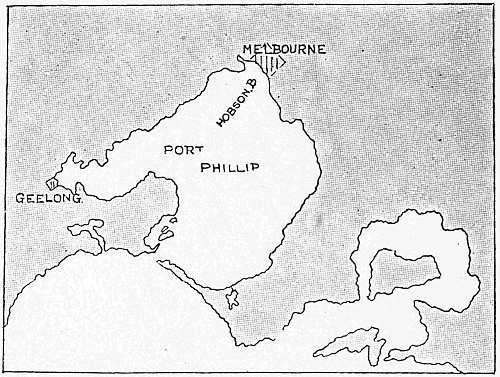

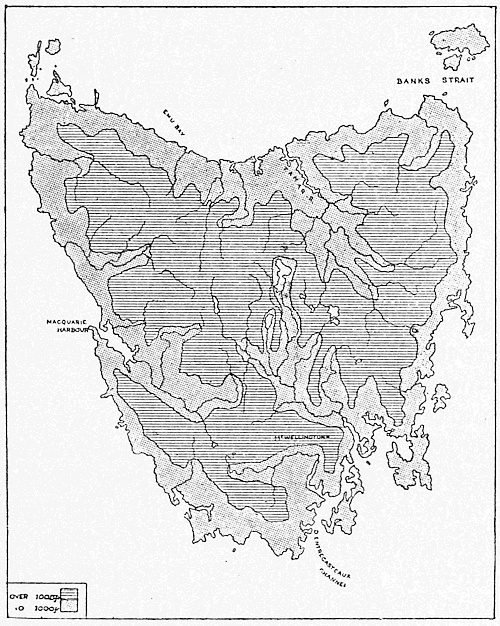

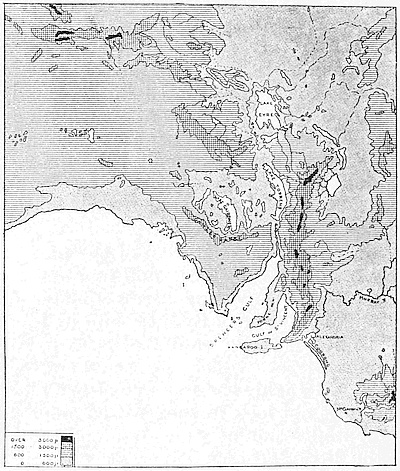

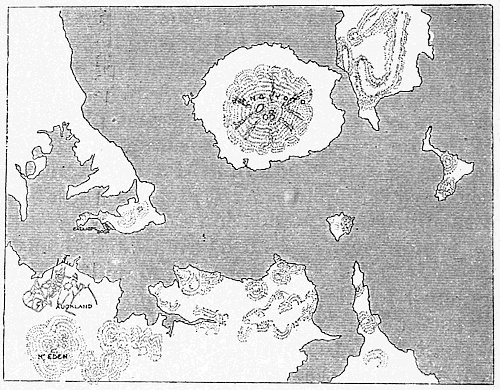

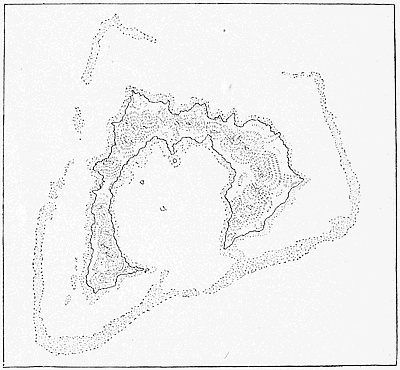

We have seen something of the coast of this area; let us now try for a moment to picture it as a whole. The map shows us an oblong block, which lies east and 48 west, on either side of the Tropic of Capricorn. On the north, two peninsulas, Arnhem Land and Cape York, project towards the Equator; between them is the Gulf of Carpentaria, the only deep indentation in the whole continent. On the south, Victoria, continued by Tasmania, stretches into the cool waters of the Southern Ocean. A coastal plain, broad in the north, narrow elsewhere, fringes a plateau which occupies the greater part of the oblong. The plain is narrowest in the east, and the plateau edge most marked, so that it resembles a series of mountain ranges. Rivers, short for the most part, plunge down the seaward edge of the plateau. The only large area of lowland is in the south-east, drained by a group of long rivers and shared by four of the Australian States. Some of these rivers lose themselves in the salt lakes and marshes of the inland basin of Lake Eyre; the rest, gathered up by the Murray, reach the sea at the one point where the plateau rim disappears. The tropical lowlands, the temperate coast-plains, the plateau and the long inward slopes of the Murray system are the main features which we shall find recurring in the geography of the various States.

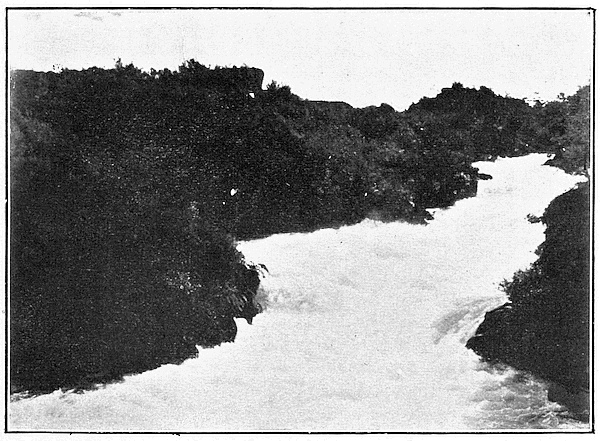

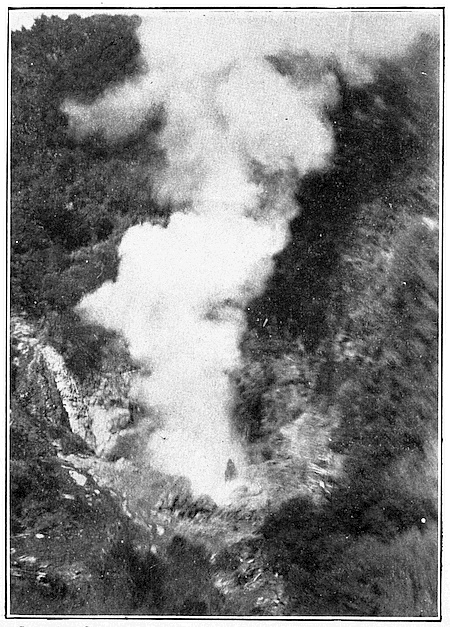

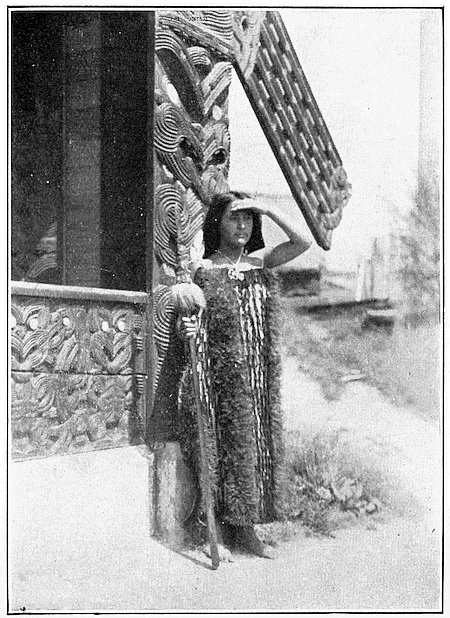

So far we have dealt only with Australia. New Zealand shows to some extent the peculiarities which mark Australia off from the rest of the world, but on[16] the whole the differences between these two sections of Australasia are more noticeable than the likeness. We might anticipate this, since the dominant fact in the development of the peculiar plant life of Australia is drought; in the case of New Zealand it is moisture. 49 Again, New Zealand has no snakes, and lacks the peculiar animals which we have seen in Australia. In fact, its only native animals are a bat and a rat, the latter perhaps introduced by the Maoris. To compensate for this it has a large group of birds peculiar to itself, including the wingless birds, which may have lost their wings since they had no need for flight from enemies on the ground. The best known of these birds is the kiwi; here we see him in his natural haunts. 50 Again, there is the takahe, which was at one time thought to be extinct; but one or two specimens have been found, and there may be others still existing. Here is one of these stuffed. Finally there is the 51 gigantic moa, which probably existed at the time of Captain Cook’s voyage. Now we can only see its skeleton, 52 but naturalists have attempted to re-construct the whole bird, as we see here. One link New Zealand 53 possesses with a very remote geological past; this is the curious tuatara or three-eyed lizard. He belongs 54 to an extinct group of reptiles which lived in Europe many ages ago and is now only represented in the fossils which we dig up. So we see that in its animal life New Zealand differs from Australia and from the rest of the world; we shall find also a strong contrast between the native races of the two countries in their character and origin, their relations with the white settlers, and their influence on the history and development of the land which they possessed before our arrival.

When, in 1770, Captain Cook dropped anchor in Botany Bay, he just missed discovering the finest harbour in the world. Voyaging northwards he sighted Port Jackson in the distance but did not examine it more closely, and the discovery was left to the first party of colonists, a few years later. The harbour which we are going to explore was the scene of the first real settlement, and is still the vital centre for the whole of New South Wales.

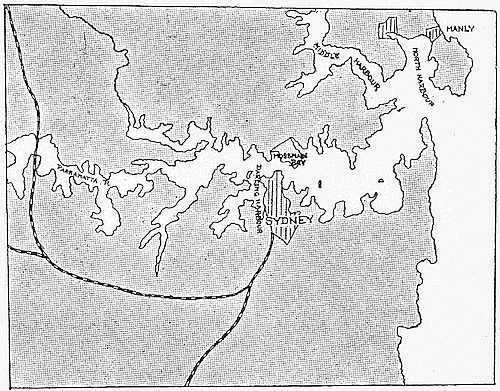

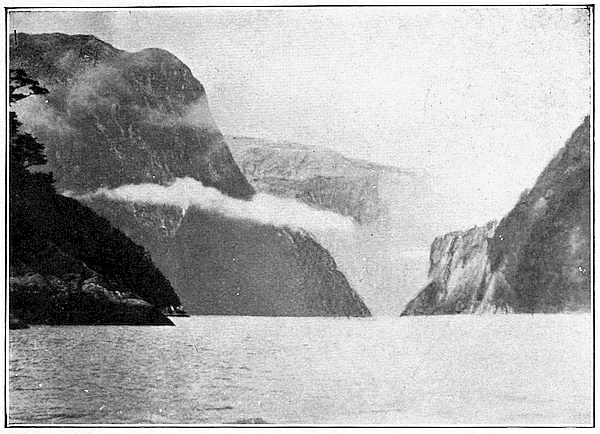

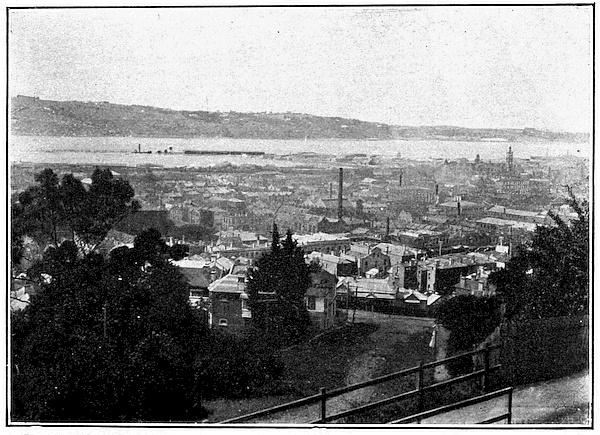

We steam through a broad channel, nearly a mile wide between the rugged points which guard it. There is no lack of room here for ships to pass one 1 another, and our large vessel seems quite insignificant beside the towering cliffs. On our right is a broad bay, the North Harbour, with the village of Manly at its head; on the other side of Manly, across a narrow isthmus, is the open ocean, with its long rollers thundering always in surf upon the beach. But inside the Heads the water is calm as a lake. In front of us, and beyond the North Harbour, is a narrow, winding inlet, running for miles into the hills; this is Middle 2 Harbour. There is plenty of good anchorage here, but it is mainly given up to pleasure boats; we are a long way yet from the commercial harbour. To reach this our vessel turns sharply southwards, behind the South Head with its lighthouses, and steams on 3 for about five miles up the Main Harbour. All along, on either hand, are jutting headlands, and in the bays between, especially on the south side, are seaside villages.[18] But we shall not see swarms of bathers on the beaches as in our own country, for there are sharks in Sydney Harbour; the only safe bathing is in the surf outside. As we approach our landing-place the houses are more closely packed together, and islands are dotted here and there in the channel. We may be reminded to some degree of parts of the Clyde, or of one of the larger inlets on the west coast of Scotland; though here we find not only the most beautiful scenery but a great seaport and busy city in the very midst of it.

We turn at last into Sydney Cove, on the south side of the harbour, and here we are moored at Circular 4 Quay in the very heart of the city. Further on to the west, just round the next point, we see Darling Harbour, 5 crowded with shipping, and its busy wharves piled with merchandise. The waterway extends some miles further inland, but here in Sydney Cove is the centre of commercial activity and the landing-place of the original settlers in 1788.

Before we land let us look at a chart which shows us the long passage by which we have entered, the [19] 6 windings of the harbour and the city spreading over the surrounding hills. This will give us our bearings and help us to understand the views.

We will now land, climb the hill, and look down on (4) the Cove. There, on the further side, is our vessel, lying close to the tall warehouses. Beyond it are the trees of Government Domain, with the tower and roof of Government House showing above them. The little bay on our left is Farm Cove, where the warships lie 7 at anchor; and beyond it again, on the next point, we see the trees of the Botanical Gardens. Then we have Woolloomooloo Bay, running up to a new and crowded suburb, and in the distance many more points and bays, as we look along the south side of the harbour back towards the sea. Or let us climb up behind our vessel, in another direction, to the library, and look down over Farm Cove. Below us, on the little island, is 8 Fort Denison; and across the water on the north side is Mossman Bay, where a new Sydney is growing up. It is all very different from the crowded ugliness of most of our own commercial cities.

To see something of the inside of the city we walk up George Street from the quayside. On our right is old Sydney, irregular and picturesque, built on the rocky peninsula between Sydney Cove and Darling Harbour. Here is a view of one of the old streets. 9 George Street itself is very modern in appearance, with its broad roadway, electric cars, and handsome stone 10 buildings. Here is the Post Office at one of the corners; it is built of sandstone and granite which are to be 11 found in abundance in the local rocks. Across George Street runs Bridge Street, one of the oldest in the city. It takes its name from the old bridge across the little Tank stream, which has now been absorbed into the underground drainage of the city, like so many of our old streams in London. There are many Government buildings in this older part as we might expect,[20] and at the top is the entrance to Government House.

On the west side of Darling Harbour is the suburb of Pyrmont, on another peninsula; and at the base of these peninsulas Sydney is spreading and broadening out beyond the railway station. But even here, in the new suburb, are many parks and open spaces reserved for public use; while nothing can destroy the beauty of the older portion of the city, divided up by inlets, and with glimpses down many of its sloping streets of the blue water and the hills beyond. It is not surprising that the early settlers found this spot far more attractive than the open beach of Botany Bay.

As we look down on the Cove and its neighbourhood, we must remember that we have in front of us only a small part of the great expanse of landlocked anchorage available in the harbour; there is still room for unlimited growth, though Sydney has already over a third of the total population of New South Wales collected in and around it.

We must now look beyond the actual harbour, and try to place ourselves in the position of the early settlers. We have great distances to cover, since New South Wales is just half as large again as France; we must therefore keep fairly closely to the railway; but we shall not lose much by this as the railway will carry us through all the important districts of the State.

We may travel north, south, or west, and the map can give us some idea of the character of the country 12 through which we shall pass. Sydney lies near the middle of a long strip of coastland, shut in on its western side by the steep edge of a great plateau. In the neighbourhood of Sydney this edge goes by the name of the Blue Mountains. Here the barrier is about forty miles inland; further north, in the valleys of the Hunter and Hawkesbury rivers, the lowland widens out to nearly a hundred miles; while in some[21] parts of the south the highlands come right down to the sea. This narrow strip was the original New South Wales.

We can travel now by railway along the coast strip 13 to Newcastle, then up the valley of the Hunter, and finally climb the Liverpool Range on to the plateau beyond. But the journey was far from easy for the early settlers. In fact, until 1820, when a stock route was discovered from Sydney to Newcastle, the only intercourse with the north was by sea, and Newcastle grew up almost as a separate colony in consequence. The valleys of the Hunter and other rivers gave a natural direction to early settlement, since in their lower courses they flow through wide alluvial flats which are[22] very fertile and easy to cultivate. But they are subject sometimes to devastating floods, as the settlers found to their cost, while the heavy summer rainfall is not well suited to certain of our crops, such as wheat. So in the early days the colony was often in difficulty as to its main food supply.

The name Newcastle at once suggests coal; and coal is everywhere in this district. The surface of the country round Sydney is largely a barren sandstone; but underlying the whole of the area, from Newcastle on the north to Bulli on the south, and extending westward to the other side of the plateau edge, is a vast coalfield. Its chief development at present is around Newcastle. Here is a view of Hetton colliery, 14 Newcastle; both the name and the picture remind us strongly of the North of England. We see the coal being wound up from the shaft as in our own mines, and in the distance vessels lying at the wharves in the fine harbour. Here again is a general view of the 15 harbour in which we can clearly distinguish the loading of the coal and merchandise.

A journey southward from Sydney to the other end of the coalfield will bring us to a less familiar type of mine. At Clifton the early explorers found coal strewn on the beach; the actual seam is in the face of the cliff, and shows as a broad black band, while 16 the coal is mined by means of adits, and then run on to the little pier to be shipped. The coal is found under Sydney itself, and mining is now in progress on the south side of the harbour; but the shafts are much deeper here than at Newcastle, since the coal measures lie in the shape of a saucer, and Sydney is near the middle. We may notice here that the southern railway line ends at Nowra on the Shoalhaven river, and beyond are only a few small coast towns; so we need not at present explore further in this direction.

We will now leave the coast district for a time[23] and climb the plateau edge to survey the country beyond. First let us consider the nature of the obstacle by which the early settlers were faced. The Blue Mountains are merely a part of the eastern rim of a great tilted tableland of sandstone, with a steep face towards the sea and a long and more gentle slope towards the west. Down this face a series of comparatively short streams come tumbling to the sea; while on the other side of the ridge, almost within sight of the sea, are the sources of the slow westward-flowing rivers, whose courses are measured by thousands of miles.

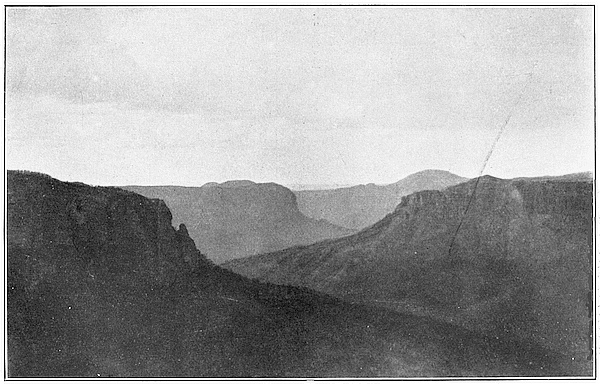

In this sandstone block the torrents have carved out deep gorges, which often widen out up-stream into broad valleys; but these valleys are deceptive and do not provide a road to the interior, since they 17 end in steep cliffs over which the streams plunge in waterfalls. Here is a view of the country at Govett’s 18 Leap; we may notice the flat tops of the ridges, all about the same level, which suggest the old surface of a plateau. It was a long time before the early settlers found a path over this edge, and the available roads are still very few all along its length, as we may see by tracing them on the map; our train must twist and tunnel up one of the ridges between two of the valleys by a most difficult route, with steep inclines, instead of following the bank of the stream below. We realise that climbing a plateau is a far more serious matter for the engineer than piercing through a narrow ridge of mountains.

At Victoria, on our way up, we leave the train for a coach drive, to Jenolan. Here the scenery changes; the rock is no longer sandstone, but limestone, and the streams have burrowed out many curious gorges and underground channels as in our own Derbyshire. Here we have one of these in the form of a huge rock 19 archway through which we catch a glimpse of the[24] country beyond; while far down below us flows the stream which bored out the arch. A little further on we find the stream running at the bottom of a lofty 20 cavern, and out into a deep and narrow gorge. Here again is a view of the interior of one of these caverns, with its huge pillars hanging from the roof and rising up from the floor. These limestone tunnels and 21 gorges, and the sandstone valleys with their steep surrounding cliffs and narrow outlets, are a fine subject for the artist and tourist in search of beauty, but do not suggest opportunities for settlement or farming; at the same time they are evidently a serious obstacle to movement. The bare surface of the plateau is little better; in fact, the highlands in this district are still among the most thinly populated areas in New South Wales, in spite of their nearness to the capital and the oldest settlements. So we pass through quickly, and coming out by a 22 long tunnel drop down to Lithgow, where we enter an entirely different kind of country. Lithgow is a manufacturing town, with coal mines, ironworks, smoke and dirt. It really belongs to the coast region, and is here, on the inside of the ridge, only because a small piece of the Newcastle coalfield, which underlies all the country which we have been crossing, crops out in this district from under the sandstone. On our journey inland we shall not meet with any other town of the same type, as we are now entering the great wheat-belt of Eastern Australia.

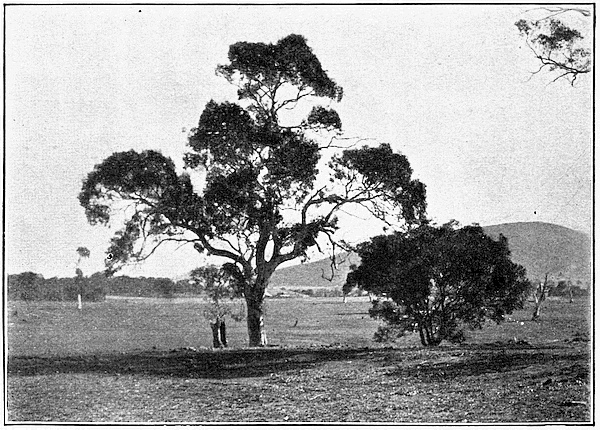

Here is a typical farm on the eastern edge of the 23 wheat-belt. Beyond the hills, which we see in the background, is the steep descent to the Hunter valley and the coastal plain. The hills are wooded, but the trees thin out and the ground becomes more open as we go westward down the long slope. We must not forget that here at the back of the plateau edge, though we are on the “Plains,” yet we are still more than a[25] thousand feet above the level of the sea. We shall realise the importance of this height later. Our next picture shows a wide expanse of level ground, under 24 grain, with the reapers at work. We are at Tamworth on the Liverpool Plains, not far from the northern end of the wheat-belt; but this belt can be traced from Queensland right round to South Australia, and from end to end the scenery is the same. There are the same open sunny plains, dotted with homesteads and small agricultural towns, and covered with the waving grain. Everywhere is the hum of machinery, reaping, binding, and threshing; for labour here is costly and as little as possible is done by hand. We may find it hard to tell, from the appearance of the country, where we are within a thousand miles, and we may be struck by the monotony of the view as we rush through it. None the less this great field of grain is impressive in its own fashion, if we use our imagination and follow the heavily loaded waggons to the station, and on to Sydney, and so across the ocean to London or Liverpool, until the grain appears as bread in the baker’s shop. We are watching here the beginning of the process by which the crowded millions of Industrial Europe are fed; and the wide spaces under crop may give us some idea of the greatness of the business; for we have in the wheat-belt of Australia, in spite of its great extent, only a small fraction of the wheatfields of the world.

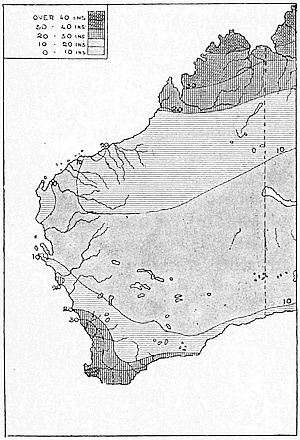

A rainfall map is the best aid to the understanding of the position and extent of the wheat area. The 25 map is arranged in a series of parallel zones, which show the annual fall decreasing rapidly on the west side of the Divide, as we move further away from the coast. We are crossing one of these zones where the fall is from twenty to twenty-five inches, or not far removed from that of the eastern counties of England. This is the wheat-belt of Eastern Australia, which[26] follows the rainfall right round the inner slope of the plateau as far as South Australia.

This zone gradually shades off into another rather broader where the rainfall is much lower; from ten to twenty inches at most. So the scenery changes as we travel westward until we are lost in the country of the western plains: a great dry lowland not far above sea-level, and drained by slow-moving rivers, the Lachlan, Darling, Murray and their tributaries. The railway runs north-westward, through interminable miles of grass and scrub, until it ends at Bourke, the head of navigation on the Darling. It is the land of the sheep and nothing else. We may gain some idea of the enormous extent of land in this part of Australia, available for pasture or agriculture in some form, by placing upon it for comparison the eastern part of the United States, as in the map which we see here. 26

New South Wales possesses nearly as many sheep as the rest of Australia together, and most of these are to be found on the inland slope of the plateau and far out into the plains, more especially in the Riverina district, between the Murray and the Murrumbidgee. We have left behind us the wheatfield and the reapers; the loaded waggons which we pass, drawn by long teams 27 of horses, are carrying great bales of wool to the railway. We may follow the wool back to the shearing sheds 28 where again all the work is done by machinery; then we go on to the sorting shed, and so to the railway and the showrooms at Sydney, where thousands of samples 29 are displayed for the benefit of the buyers for the markets of Europe. We can see the great flocks of sheep before and after the shearing at the homestead 30 or follow them as they are driven to pasture; and everywhere in this great river plain we find the same thing repeated. The rainfall is not sufficient for agriculture; but in ordinary years it will provide good grass for the sheep; and there is also the drought-resisting[27] salt-bush to eke it out. Sometimes the rain fails, and then there is neither food on the ground nor water in the creeks and pools, and millions of sheep die, as in the great drought of 1901–2. The dry climate gives the best wool in the world, but it is not without its drawbacks; though the large profits made by the farmer in ordinary years more than compensate for an occasional period of drought.

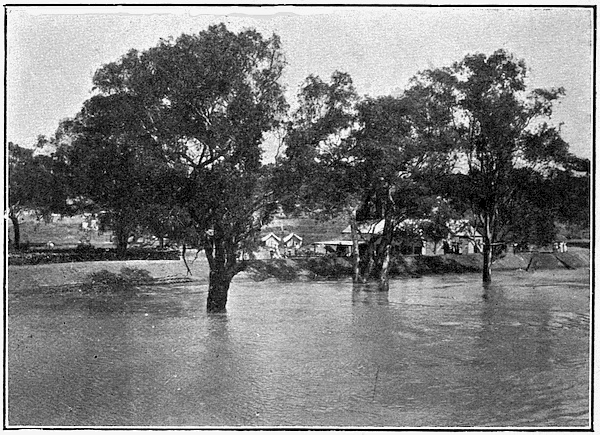

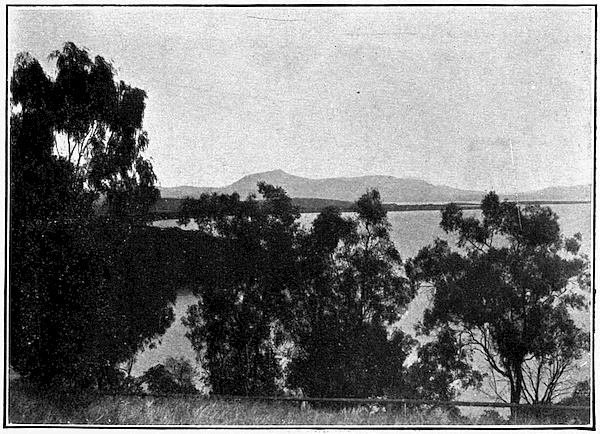

The uncertainty of the rainfall shows itself in another way, in the peculiarities of the rivers. Of all the great rivers in this basin, the Murray alone, fed by the melting snows of the Australian Alps, has a good supply of water at all seasons; the rest are variable. The Darling, Lachlan and Murrumbidgee are navigable for long distances in favourable seasons, and sometimes are flooded and overflow their banks, turning the surrounding country into a huge shallow lake; but at other times they become, in places, little more than 31 strings of detached pools. Here is a lagoon on the Murrumbidgee, and here is the Murray evidently in 32 flood, to judge from the trees growing out of the water; another view shows us the river in its ordinary 33 state. By way of contrast here is a small creek in the Riverina district; the road crosses it by 34 a ford, so that it is evidently not very deep, and would soon dry up. But after heavy rains, further up-country, the creek may become for a short time a roaring torrent. Settlers new to the country have often made the mistake of camping in the evening on the near side of a creek of this kind, only to find in the morning that the ford has vanished and that they must stay where they are until the water subsides. One of the most remarkable features in Australian weather is this sudden change from drought to flood, which not only transforms the rivers but in a few days gives a covering of rich green pasture where before was a parched desert supporting only the hardy salt-bush.

When the rivers are full we can see the shallow draught steamers collecting wool and other products; but the 35 want of water is not the only drawback. The rivers wind greatly in their courses over the level plain, so much so that at one place it is said that the steamer takes a whole day to pass a particular house, owing to the river bending right back upon itself. The river banks are marked by lines of gum trees, by which the eye can trace them for many miles across the level. Except for this, the whole area crossed by these rivers in their lower courses is one vast treeless plain, covered with grass and scrub in the rains, but at other times dry, dusty, and monotonous. It extends into Queensland and Victoria, but its greatest development is in New South Wales: for though the other colonies have large flocks of sheep, it is here that sheep-raising is the one industry above all others; in fact, under ordinary conditions, no others are profitable or even possible. In this country, next to the sheep, water is the most valuable commodity.

The greater part of the Murray-Darling basin is filled up by recent rock sediment and river alluvium; but the narrow belt of country with a moderate rainfall, lying between the plateau edge and the western plains, has not depended for its development solely on agriculture. All along it the older rocks crop out, and in the older rocks we find the valuable minerals in which Australia abounds.

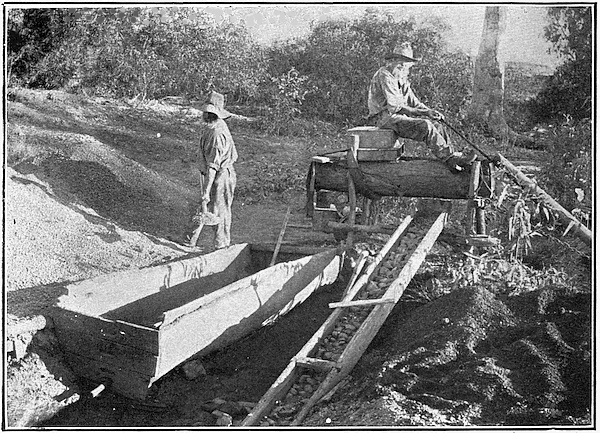

Gold, in its alluvial form, occurs all along the agricultural belt; and since the time of the first discovery near Bathurst, in 1851, the search for gold has often caused an inrush of people who have abandoned mining for the more secure and pleasant business of growing wheat or rearing sheep. Though much gold is still produced, New South Wales is not by any means the chief of the States to-day in this respect; but gold has been woven deeply into her history. One of[29] the most usual methods of obtaining gold is still by dredging alluvium; but in place of the shovel and washing-pan we have the ugly machine dredger scooping out the creeks and flats where the gold is to be found. We must look elsewhere for gold-mining from the rock on a large scale; though this is increasing in New South Wales in connexion with the development of mining for other minerals, especially copper.

Well out in the plains, and south of Bourke, at the end of a branch line of railway, is the town of Cobar; it stands just where the old rocks are disappearing underneath the recent deposits. Here is one of the chief centres of copper mining; and, once the work was started, mining for other ores naturally followed. It is a desolate country, rendered more so by the nature of the industry. The furnaces for the rough smelting of the ores need fuel, but coal is far away; so that the country round has been stripped of its small supply of timber, and has nothing left to relieve its ugly monotony. The ore, partly worked, is sent by rail all the way to Lithgow, on the coalfield, to undergo the further process of refining. The importance of these mining fields to the State lies not so much in the money value of the products as in the fact that they give rise to railways and traffic and so to a further spread of the settled agricultural population. The minerals, and especially gold, have played a great part in the settlement of the less accessible or less attractive regions of Australia.

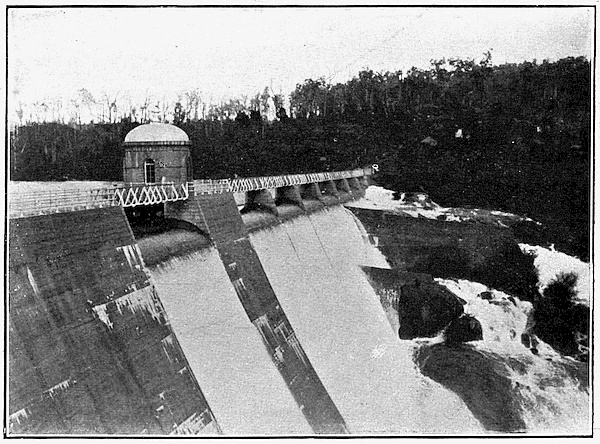

The old rocks, which disappear at Cobar, under the alluvium of the Murray basin, crop out again at the surface in the far west, and give us one of the chief silver-producing areas of the Continent. The natural outlet of the district is by Spencer Gulf, as Sydney is more than twice as far away; and the development of these mines has been largely due to the people and capital of South Australia. Here is one of the most famous mines [30] 36 at Broken Hill; and here we have the camel team, the only means of transport away from the railway. We 37 are in the semi-desert area, and the existence of the mining population is only made possible by collecting the water from the neighbouring hills in great reservoirs, 38 such as we see in the picture before us.

We have still to see the south-east corner of the State, where we shall find some of the most picturesque scenery and a country rather different from that which we have so far visited. We take a line running south from Sydney, not along the coast, but following the river valleys and so up again on to the plateau at Goulburn. Here we branch off from the main line southwards through the Monaro Plains; this is a high pasture land, thinly populated, though there is a growing agricultural industry in some of the more favoured spots. To the east of the plain are the Coast Ranges, to the west the Snowy Mountains; both extending over the border into Victoria. Cooma, the terminus of the railway, about fifty miles from the State boundary, lies nearly three thousand feet above sea-level. North-west of Cooma is the town of Kiandra, in the Alps, where we find snow and winter sports as in Switzerland. South-west of Cooma is Mount Kosciusko, rising over seven thousand feet, the highest mountain in 39 Australia; here the snow lies even in summer. We reach it by a road following the valley of the Snowy 40 River, and can ride or even motor up the track almost to the summit. Here are two views of the river and 41 its tributaries. Kosciusko is not an imposing peak as we see from these pictures, but merely a flattened ridge 42 lying on the top of a great tableland, so perhaps we may be somewhat disappointed in the outcome of our visit. 43

From Goulburn we begin the long descent to the level of the Murray. We are again crossing the agricultural belt, and forty miles west of Goulburn we break our journey at Yass. Here, on the banks of a[31] small stream, the site has been fixed for the ideal city, the future capital of Federal Australia. Notice that we can have here no great industrial and commercial centre, but merely a town like Bathurst, a centre of farming and country life. Perhaps in this it will be more representative of the real Australia than are the larger cities. In position Yass is nearer Sydney than Melbourne; but it is roughly halfway between Brisbane and Adelaide; so that it is fairly central for the long belt which contains most of the population of Eastern Australia. The city is not to be allowed 44 to grow haphazard; here we see the surveyors’ camp and the surveyors at work, mapping out the ground. 45 In the distance is Black Mountain. The whole scene is quiet and rural, but it will be very different in a few 46 years’ time. This deliberate choosing of a site for a new city is common in Australian history; we may contrast with this the way in which centres of population have grown up in the course of ages in old countries almost of their own accord.

We continue our journey down the slope, and crossing the Murrumbidgee at Wagga Wagga reach Albury, the border town. Here, it is necessary to change trains to continue the journey to Melbourne, for unfortunately the different States of Australia did not plan their railways on the same scale. In New South Wales the gauge of the lines is the same as that in England; in Victoria and in part of South Australia there is a broad gauge; while all the other railways in the continent are on a narrow gauge of three feet six inches. This has been adopted as the most economical for opening up a new country; but the differences have led to great inconvenience and loss, where through connexion is made between the main railway systems of the various States. We may remember how, in our own country, the Great Western Railway was forced to abandon the old and comfortable broad gauge, so[32] as to be able to work in connexion with all the other lines which had adopted a narrower gauge; Australia has still to face the problem of unifying her railways in this respect.

We have travelled for many miles over the railways, (13) and now perhaps we may begin to notice certain peculiarities in their arrangement. First there is the main-line system connecting up the capitals. This runs north-east and south-west from Sydney, roughly parallel to the coast. Only a short stretch of this is on the low coastal plain; the rest is inside the plateau edge. The line descends through the Victorian Mountains to the sea at Melbourne; but goes inland again on its way to Adelaide. Branching from this system, or starting independently from the coast, is a whole series of lines running inland, roughly at right-angles to the coast. Some are very short, some very long; and they commonly end at a small town on one of the rivers. We can trace them right round from the line between Normanton and Croydon, in North-West Queensland, to that ending at Oodnadatta in the desert region of South Australia. Except round Bathurst, and in the country at the back of Melbourne, we shall not find many branches or cross connexions. This curious arrangement can only be understood in the light of the resources and historical development of the country; we have already seen something of its meaning in New South Wales.

We noticed that the line from Sydney left the sea at Newcastle to follow the valley of the Hunter and scale the edge of the Liverpool Downs. For two hundred miles north of Newcastle the coast district lacks a railway; but in Clarence county, in the extreme north of the State, there is a detached piece of line running for a hundred miles not far from the coast, and touching it at one or two points. This line has a meaning.

The district is warm, as it is low-lying, and not very[33] far from the tropic; while the south-east winds bring abundant rains. It has been found to be well fitted for dairy cattle, and is displacing to some extent the coast district south of Sydney where the industry first started. Sydney still provides a good local market for the dairy products of this northern region, but there is also a growing trade with more distant places. We can understand now the need of a railway to open up the country and connect it with the sea.

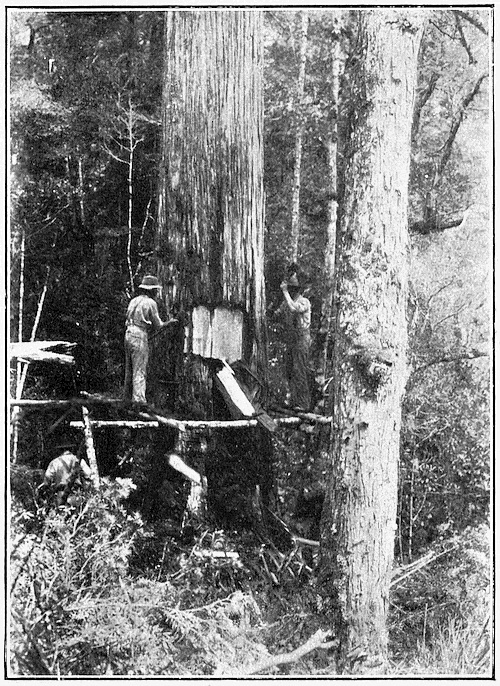

Here is a typical dairy farm with the cattle clustered 47 in the shade on the banks of the creek. We notice the abundance of trees, and the curious dead bare look of some of them. These have been ringbarked, that is, a strip of bark has been cut away right round the trunk; this process kills the tree quickly, and the dead wood can then be burnt off. It is a rough and extravagant method of clearing, and some of the forest, which grows luxuriantly in this rainy district, is put to better use. In the wetter parts are to be found the cedar and other soft ornamental woods; in the drier, are the various hard woods of the eucalyptus family, especially the ironbark and the blackbutt. It was the timber which attracted the first 48 settlers to this district, though the difficulty of transport has prevented them from making much use of it up to the present. Here we see the felled timber lying ready for removal; it must be dragged over rough 49 tracks, often for long distances, by teams of horses and bullocks. We can gain some idea, from these pictures, of the huge size of the trees and the difficulty of forest development. Evidently the forest further inland can only be attacked by the aid of the railway. We shall find similar conditions in Queensland; in fact, we may look on this coast strip as giving us geographically the beginning of the Queensland coast conditions; for round Grafton, at the southern end of the railway, we find the cultivation of the sugar-cane.

We have seen the beginning of the new capital of Federated Australia; we will now, before visiting Queensland, cross Torres Strait, with its innumerable islands and reefs, for a glimpse of Australia’s new tropical colony. British New Guinea, or Papua as it is now officially styled, was annexed in 1888, owing to pressure from the Australian colonies, and more particularly Queensland. From the first, Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria contributed to the cost of administration; and in 1906 the new Commonwealth Government took over the entire control.

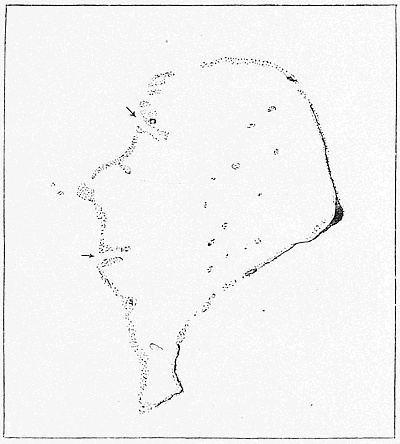

British Papua is a curiously shaped corner, carved 50 out of the eastern end of the great island of New Guinea. The western end of the island is entirely Dutch; the eastern we share with Germany. We may think of British Papua as two separate blocks, as the Gulf of Papua almost divides the territory into two. In the west is a rectangular area, with a low marshy coast, fringed with mangroves and split up by river deltas, especially that of the Fish River. The dividing line in this district between British and Dutch territory is merely a line of longitude. The country is mostly unexplored, except along the Fish and Strickland Rivers, and the natives are still fighters and cannibals. On the north of this block of country, and continuing south-east through a long narrow peninsula, is a high mountain backbone, on the other side of which is German territory. The eastern peninsula is mountainous everywhere; while the whole country is wet, densely forested and difficult to penetrate. The peninsula ends in a string of islands, mostly volcanic.

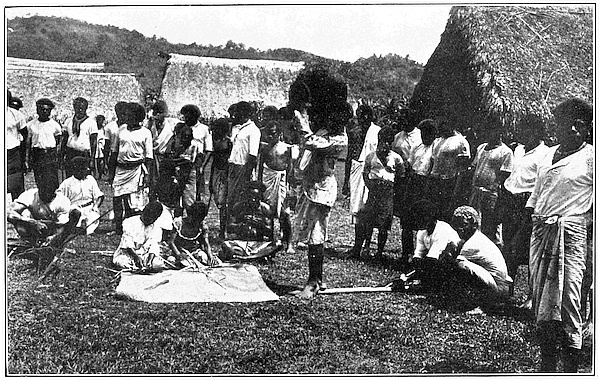

The colony is in the first stage of organisation, when the main problem is to reduce the native to some kind of order. Let us see what he is like and how he lives. 51 Here are two inhabitants of the coast district; they seem very different from the aborigines of Australia. Notice their frizzy hair, standing out in a great mop,[35] and their bracelets and necklaces. The Papuans are fond of personal adornment. Here is a girl from the 52 same district; she wears an elaborate girdle of grass. Behind her we see the end of a curious canoe, with an outrigger. The canoe is important to the Papuan, since he commonly plants his village at the water’s edge. Here is a village, and here is a nearer view of 53 some of the houses; they are merely covered platforms, built on piles. Fighting and headhunting are 54 still the amusements of the tribes which are not yet brought under our control, but conditions are changing rapidly for the better. Here is one of the instruments 55 of the change, the native village constable, who seems quite proud of his office. Behind him, law and order 56 are represented by the visiting magistrate with a small force of armed constabulary. The chief difficulty in opening up the country is that of movement. Everywhere we find forest, mountain, and unbridged streams. 57 Here is the kind of track through which the explorer must force his way, and here we see two methods of 58 crossing a stream. The native bridge hardly seems calculated for heavy traffic. We may realise from 59 these pictures the nature of the task of controlling the natives of the interior, such as the formidable pair in 60 front of us. Even when reduced to order the Papuan is not anxious to develop the country by work on plantation or mine.

Port Moresby, the capital, stands on a fine bay in a relatively dry district. Here a few score white people represent the influence of civilisation. The climate forbids effective settlement. Here we see a 61 European house with its staff of servants, and here is the steamer which links Papua with the mainland. It 62 will be interesting to see how Australia solves the various problems of her new tropical Dependency. In Queensland we shall find similar problems, though in a modified shape.

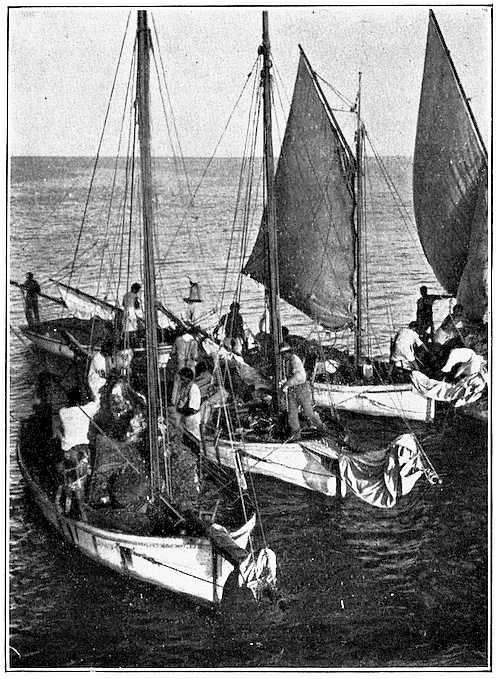

The land route from New South Wales to Queensland does not at present follow the sea-coast. The railway at Newcastle turns up the valley of the Hunter River, climbs the steep edge of the plateau, to run along the eastern rim of the Liverpool Plains and the Darling Downs, and then descends again by a steep pass to the sea-level at Brisbane. At the little frontier station of Wallangarra we must change trains, since the Queensland 1 railways, as we have already noticed, are on a narrower gauge than those of New South Wales. This would be a very serious matter but for the alternative route by sea to Sydney; this is the natural route for heavy goods, since nearly all the important towns of Queensland are on or near the sea-coast. Before the advent of the railway, the sea was the sole means of intercourse for all the towns on the eastern rim of Australia; even in our own country, where the railway system is highly developed, the coasting trade is still of very great importance.

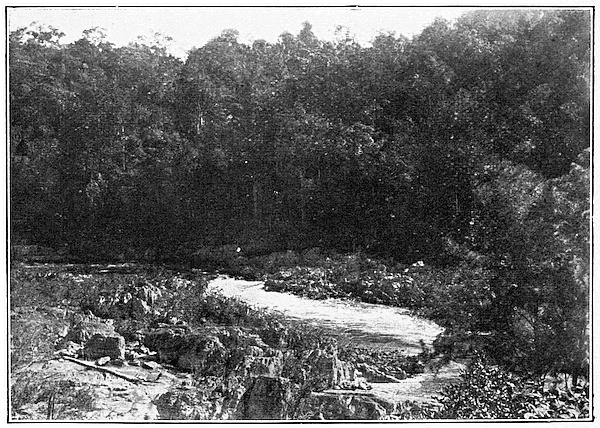

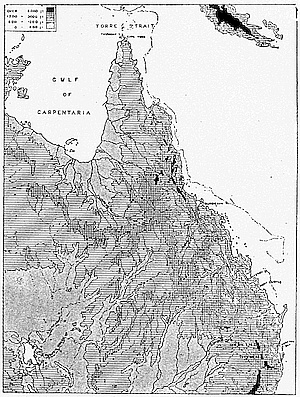

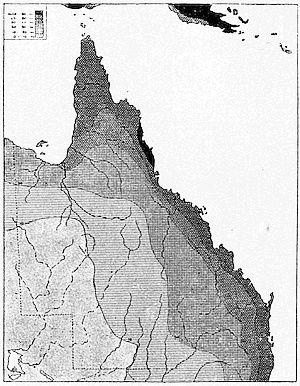

The course of the railway suggests that the structure of the country is not unlike that which we have seen 2 in New South Wales. This is true of the Darling Downs area, but further north the map shows us a somewhat different type of country. The eastern part of the State consists in the main of a broken and irregular highland mass; the west of rolling plains, sloping gently towards the interior or the Gulf of Carpentaria; but we look in vain for a long, well-marked escarpment, such as we find further south. The mountain ridges[37] seem to run in every direction, sometimes, as near Cairns, forming a definite coast-range, at others striking inland or running down in spurs to the sea; so that the country is split up into a number of distinct basins, each with its own group of rivers flowing in the most diverse courses. Thus, from Cairns to Brisbane a great stretch of country, broadest in the middle, narrow at both ends, drains into the Pacific; but the Burdekin and the headwaters of the Fitzroy flow for long distances parallel to the coast, before turning and breaking through the ranges to the sea. Another group in the south joins the Murray-Darling system and belongs physically to New South Wales; the rivers of the north-west and of the Cape York peninsula drain for the most part into the Gulf of Carpentaria, while a large block of country in the west and south-west is occupied by intermittent streams, which in time of flood find their way into the inland basin of Lake Eyre, in South Australia. The country has not that simplicity of relief which we found over the greater part of New South Wales, and, as we might expect, the rainfall does not show such clear and[38] symmetrical divisions. The fall from the south-east winds is more irregular and more widely distributed 3 inland than in New South Wales; while in the north there is an area with tropical rains of a monsoon type.

On our railway journey we have crossed from one State to another, but we must notice that, except in the south-east corner, the boundaries of Queensland have no relation to the natural features of the country; they are merely mathematical lines. The reason for this is to be found in the method by which the settlement was carried out. Moreton Bay was one of Cook’s landing-places in 1770; but the Brisbane River, flowing into it, was not discovered until 1823; the first settlement was formed in 1824, and the Province remained part of the mother State until 1859, when after much agitation it became an independent settlement. The interior was not explored at the time, so that the only way of determining a boundary was to follow a line of latitude or longitude. A similar method has been used in more recent times in parcelling out unexplored regions of Africa among the European Powers. The[39] western boundary of the new State was the line of longitude 138° E., and what is now the Northern Territory remained nominally part of New South Wales, which thus consisted for a short time of two areas widely separated.

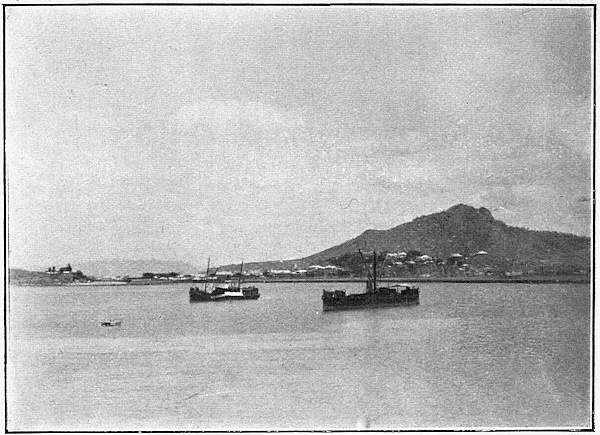

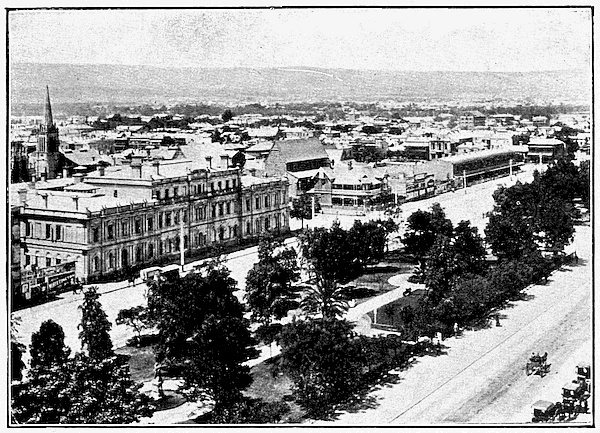

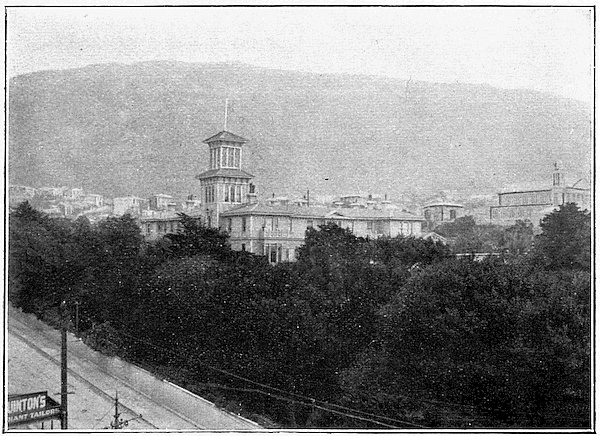

The very name of the city of Brisbane recalls the connexion with the older colony, since Sir Thomas Brisbane was Governor of New South Wales in the years 1821–5, at the time of the first settlement. The city stands, not on the shores of Moreton Bay, as we might expect, but twenty miles up the river, on both 4 banks, which are connected by the Victoria bridge. Here is a view over the bridge from the north bank; 5,6 and here is a wide view of the river beyond the city. There is plenty of space in Brisbane, with its suburbs, for the population of 100,000; there are parks and gardens everywhere, and a large number of fine public buildings. Here are the library and the Executive 7 Buildings in a beautiful garden, with a statue of Queen Victoria; here again the Parliament House, and here one 8 of the main streets of the city. We have nothing like this in any town of the same size in England, but we 9 must remember that Brisbane has been built for the future, and is the capital of a State more than three times the size of France.

Brisbane lies in the extreme corner of Queensland, not, it may seem, a very good position for the capital; but the south has the more temperate climate, while behind Brisbane is some of the most fertile land in the State. Westward a railway runs for nearly five hundred miles, at right-angles to the coast-line, to Charleville on the Warrego; we are about to make a rapid survey of the country from it. Twenty-five miles out, we pass through Ipswich, at the head of the river navigation; it is a busy town with valuable coal mines and the main railway works of the State. Then we climb again the steep plateau edge, which[40] we descended on our journey from Sydney, and come out at Toowoomba, on the Darling Downs, fifteen hundred to two thousand feet above the level of the sea.

The Darling Downs country was reached in 1827, by Allan Cunningham, botanist and explorer, who travelled by way of the Hunter River and the Liverpool Plains; but the journey was difficult, and the first occupation was not until 1840, when Patrick Leslie brought over a few sheep and settled in the neighbourhood of Warwick. Others soon followed; the direct road to the coast was discovered, and the basin of the Condamine River became a great pastoral country where fortunes were made by the early squatters. There is less rain here than on the eastern side of the plateau edge, but it is sufficient for agriculture, and there is plenty of water in the streams. Much of the soil is volcanic in origin, and of great fertility, so that the land is wasted on 10 sheep. Here we see the natural grass in this fertile region, and here is a great sheep run. The rancher’s 11 home, which we have next, suggests comfort and success. At the present time, with the aid of the Government, 12 the great pastoral properties are being broken up gradually, and sold or let to farmers; so that a district which started as a sheep run bids fair to become one of the most important agricultural areas in Australia. Toowoomba, the chief centre of this fertile district, has 13 already the air of a busy and prosperous market town, as we may judge from the picture here.

As we travel further west the country becomes drier and rather less fertile, so that agriculture gives way more and more to sheep. The conditions are not unlike those which we found to the west of Sydney; and we have seen that the Condamine and other rivers of this area all belong to the New South Wales river system. In fact we are crossing the northern end of[41] the long agricultural belt which lies behind the coast ranges. Though we are close to the Tropic, the climate is not very different from that further south, owing to the height of the plateau above the sea. There are even slight frosts in the winter. Further north, we shall find a marked change; wheat disappears and sheep give way more and more to cattle. The cause of this lies in the different conditions of rainfall and temperature. To visit this country to the north we must return to Brisbane and resume our journey along the coast.

Our first port of call is Gladstone, nearly three hundred miles north of Brisbane, on the landlocked inlet of Port Curtis, one of the finest natural harbours on the whole coast. Here is a view of the bay and the 14 jetty. As we see, there is no very great trade at present, no line of wharves and warehouses; the importance of 15 Gladstone is in the future; its chief business at present is the shipment of meat and cattle. A short railway journey takes us to Rockhampton, which lies some 16 distance up a river, the Fitzroy; in this it resembles Brisbane. Near Rockhampton we find a steamer 17 loading frozen meat from the factory. From Rockhampton the central railway runs nearly due west for over four hundred miles, to the Thompson River on the Bowen Downs. There is also a railway along the 18 coast to Brisbane, linking up the various small seaports; but this line is a late construction. The typical railway of Queensland starts from the coast and runs directly inland; and the development of the country follows the same course.

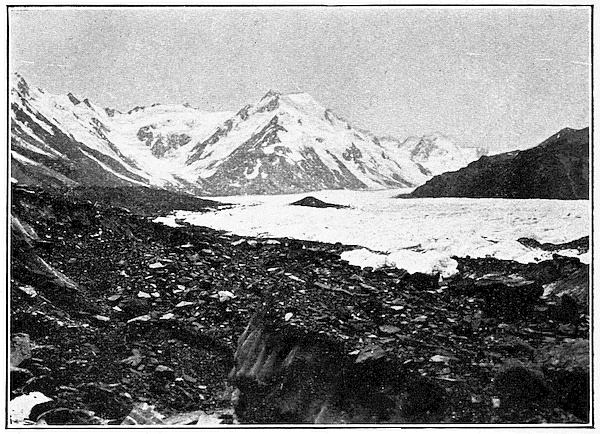

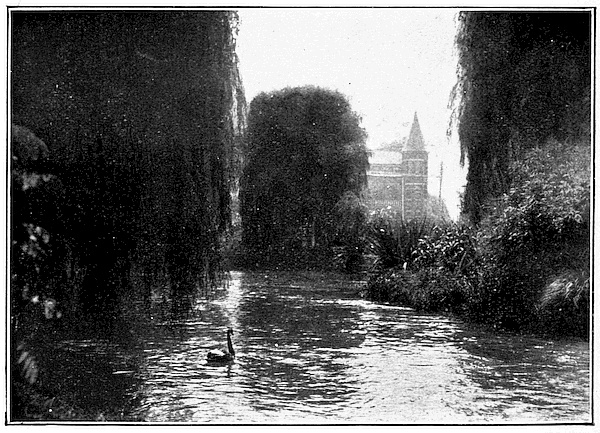

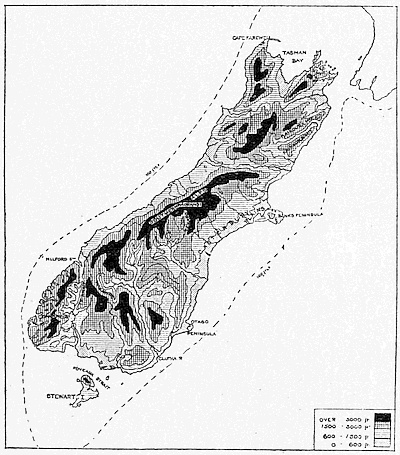

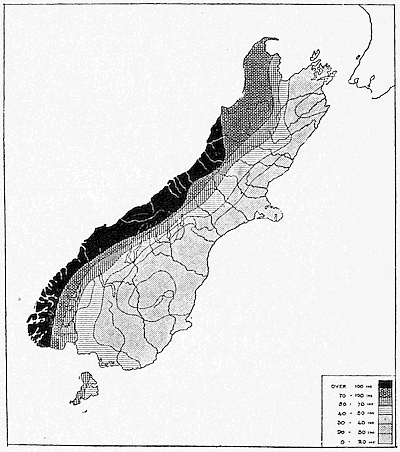

As we follow this inland line, in the wetter districts near the coast we find cattle everywhere. Further west, where the rainfall grows less, there are more sheep; but the area of considerable rainfall is much greater than in the districts further south, owing to the broadening out and irregularity of the eastern[42] highland mass. The whole of this moist area is particularly suited to cattle.