“HAVE I A WOTE FOR GRINNAGE?”

Project Gutenberg's The Works of Thomas Hood; Vol. 02 (of 11), by Thomas Hood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Works of Thomas Hood; Vol. 02 (of 11)

Comic and Serious, in Prose and Verse, With All the Original

Illustrations

Author: Thomas Hood

Editor: Tom Hood

Frances Freeling Broderip (née Hood)

Release Date: February 2, 2020 [EBook #61301]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WORKS OF THOMAS HOOD ***

Produced by Jane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on the print version of The Works of Thomas Hood, Vol. II, published in 1882. Inconsistent and uncommon spelling and hyphenation have been retained; punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Footnotes have been moved to the end of the sections in which their respective footnote anchors are situated.

HOOD’S OWN.

COMIC AND SERIOUS, IN PROSE AND VERSE, WITH ALL THE ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS.

EDITED, WITH NOTES,

BY HIS SON AND DAUGHTER.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

WARD, LOCK, & CO., WARWICK HOUSE,

SALISBURY SQUARE, E.C.

NEW YORK: 10 BOND STREET.

[1] A word caught from some American Trader in passing.

“DO you see that ’ere gentleman in the buggy, with the clipt un?” enquired Ned Stocker, as he pointed with his whip at a chaise, some fifty yards in advance. “Well, for all he’s driving there so easy like, and comfortable, he once had a gig-shaft, and that’s a fact, driv right through his body!”

“Rather him than me,” drawled a passenger on the box, without removing his cigar from his mouth.

“It’s true for all that,” returned Ned, with a nod of his head equal to an affidavit.[Pg 5] “The shaft run in under one armpit, right up to the tug, and out again at t’other besides pinning him to the wall of the stable—and that’s a thing such as don’t happen every day.”

“Lucky it don’t,” said the smoker, between two puffs of his cigar.

“It an’t likely to come often,” resumed Ned, “let alone the getting over it afterwards, which is the wonderfullest part of it all. To see him bowling along there, he don’t look like a man pinned to a stable-wall with the rod through him, right up to the tug—do he?”

“Can’t say he does,” said the smoker.

“For my part,” said Ned, “or indeed any man’s part, most people in such a case would have said, it’s all up with me, and good reason why, as I said afore, with a shaft clean through your inside, right up to the tug—and two inches besides into the stable wall, by way of a benefit. But somehow he always stuck to it—not the wall, you know—but his own opinion, that he should get over it—he was as firm as flints about that—and sure enough the event came off exactly.”

“The better for him,” said the smoker.

“I don’t know the rights on it,” said Ned, “for I warn’t there—but they do say when he was dextricated from the rod, there was a regular tunnel through him, and in course the greatest danger was of his ketching cold in the lungs from the thorough draught.”

“Nothing more likely,” said the fumigator.

“Howsomever,” continued Ned,[Pg 6] “he was cured by Dr. Maiden of Stratford, who give him lots of physic to provoke his stomach, and make him eat hearty; and by taking his feeds well,—warm mashes at first, and then hard meat, in course of time he filled up. Nobody hardly believed it, though, when they see him about on his legs again—myself for one—but he always said he would overcome it, and he was as good as his word. If that an’t game, I don’t know what is.”

“No more do I,” said the man with the Havannah.

“I don’t know the philosophy on it,” resumed Ned, “but it’s a remark of mine about recovering, if a man says he will, he will,—and if he says he won’t, he won’t—you may book that for certain. Mayhap a good pluck helps the wounds in healing kindly,—but so it is, for I’ve observed it. You’ll see one man with hardly a scratch on his face, and says he, I’m done for—and he turns out quite correct—while another as is cut to ribbons will say—never mind,—I’m good for another round, and so he proves, particularly if he’s one of your small farmers. I’ll give you a reason why.”

“Now then,” said the smoker.

“My reason is,” replied Ned, “that they’re all as hard as nails—regular pebbles for game. They take more thrashing than their own corn, and that’s saying something. They’re all fortitude, and nothing else. Talk about punishment! nothing comes amiss to ’em, from butt-ends of whips and brickbats down to bludgeons loaded with lead. You can’t hurt their feelings. They’re jist like badgers, the more you welt ’em the more they grin, and when it’s over, maybe a turn-up at a cattle fair, or a stop by footpads, they’ll go home to their missises all over blood and wounds as cool and comfortable as cowcumbers, with holes in their heads enough to scarify a whole hospital of army surgeons.”

“The very thing Scott has characterised,” I ventured to observe, “in the person of honest Dandie.”

“Begging your pardon, Sir,” said Ned,[Pg 7] “I know Farmer Scott very well, and he’s anything but a dandy. I was just a going to bring forward, as one of the trumps, a regular out-and-outer. We become friends through an axident. It was a darkish night, you see, and him a little lushy or so, making a bit of a swerve in his going towards the middle of the road, before you could cry Snacks! I was over him with the old Regulator.”

“Good God!” exclaimed my left-hand companion on the roof. “Was not the poor fellow hurt?”

“Why, not much for HIM,” answered Ned, with a very decided emphasis on the pronoun. “Though it would have been a quietus for nine men out of ten, and, as the Jews say, Take your pick of the basket. But he looked queer at first, and shook himself, and made a wryish face, like a man that hadn’t got the exact bit of the joint he preferred.”

“Looked queer!” ejaculated the compassionate passenger, “he must have looked dreadful! I remember the Regulator, one of the oldest and heaviest vehicles on the road. But of course you picked him up, and got him inside, and——”

“Quite the reverse,” answered Ned, quietly, “and far from it; he picked himself up, quite independent, and wouldn’t even accept a lift on the box. He only felt about his head a bit, and then his back, and his arms, and his thighs, and his lines, and after that he guv a nod, and says he, ‘all right,’ and away he toddled.”

“I can’t credit it,” exclaimed the man on the roof.

“That’s jist what his wife said,” replied Ned, with considerable composure, in spite of the slur on his veracity. “Let alone two black eyes, and his collar bone, and the broke rib, he’d a hole in his head, with a flint sticking in it bigger than any one you can find since Macadaming. But he made so light on it all, and not being very clear besides in his notions, I’m blest if he didn’t tell her he’d only been knockt down by a man with a truck!”

“Not a bad story,” said the smoker on the box.

I confess I made internally a parallel remark. Naturally robust as my faith is, I could not, as Hamlet says, let “Belief lay hold of me,” with the coachman’s narrative in his hand, like a copy of a writ. I am no stranger, indeed, to the peculiar[Pg 8] hardihood of our native yeomanry; but Ned, in his zeal for their credit, had certainly overdrawn the truth. As to his doctrine of presentiments, it had never been one of the subjects of my speculations; but on a superficial view, it appeared to me improbable that life or death, in cases of casualty, could be predetermined with such certainty as he had averred; and particularly as I happen to know a certain lady, who has been accepting the Bills of Mortality at two months’ date, for many years past—but has never honoured them when due. It was fated, however, that honest Ned was to be confirmed in his theories and corroborated in his facts.

We had scarcely trotted half a mile in meditative silence, when we overtook a sturdy pedestrian, who was pacing the breadth as well as the length of the road, rather more like a land surveyor than a mere traveller. He evidently belonged to the agricultural class, which Ned had distinguished by the title of Small Farmers. Like Scott’s Liddesdale yeoman, he wore a shaggy dreadnought, below which you saw two well-fatted calves, penned in a pair of huge top-boots—the tops and the boots being of such different shades of brown as you may observe in two arable fields of various soil, a rich loam and a clay. In his hand he carried a formidable knotted club-stick, and a member of the Heralds’ College would have set him down at once a tenant of the Earl of Leicester, he looked so like a bear with a ragged staff.

I observed that Ned seemed anxious. One of his leaders was a bolter, and his wheelers were far from steady; and the man ahead walked not quite so straightly as if he had been ploughing a furrow. We were almost upon him—Ned gave a sharp halloo—the man looked back, and wavered. A minute decided the matter. He escaped Scylla, but Charybdis yawned for him—in plain prose, he cleared the Rocket, but contrived to get under the broad wheel of a Warwickshire waggon, which was passing[Pg 9] in the opposite direction. There was still a chance,—even a fly-waggon may be stopped without much notice—but the waggoner was inside, sweethearting with three maids that were going to Coventry. Every voice cried out Woh! but the right one. The horses plodded on—the wheels rumbled—the bells jingled—we all thought a knell.

Ned instantly pulled up, with his team upon their haunches—we all alighted, and in a moment the sixteen the Rocket was licensed to carry were at the fatal spot. In the midst of the circle lay, what we considered a bundle of last linen just come home from the mangle.

“That’s a dead un,” said the smoker, throwing away as he spoke the butt-end of a cigar.

“Poor wretch,” exclaimed the humane man from the roof, “what a shocking spectacle!”

“It’s over his chest,” said I.

“It’s all over,” said the passenger on my right.

“And a happy release,” said a lady on my left; “he must have been a cripple for life.”

“He can’t have a whole rib in his body,” said a man from the dicky.

“Hall to hattums,” said a gentleman from the inside.

“The worst I ever see, and I’ve had the good luck to see many,” said the guard.

“No, he can’t get over that,” said Ned himself.

To our astonishment, however, the human mass still breathed. After a long sigh it opened one eye—the right—then the other—the mouth gasped—the tongue moved—and at last even spoke, though in disjointed syllables.

“We’re nigh—hand—an’t we—the nine—milestun?”

“Yes—yes—close to it,” answered a dozen voices, and one in its bewilderment asked, “Do you live there?” but was set right by the sufferer himself.

“No—a mile fudder.”

“Where is there a surgeon?” asked the humane man, “I will ride off for him on one of the leaders.”

“Better not,” said the phlegmatic smoker, who had lighted a fresh cigar with some German tinder and a lucifer—“not used to saddle—may want a surgeon yourself.”

“Is there never a doctor among the company?” inquired the guard.

“I am a medical man,” replied a squat vulgar-looking personage. “I sell Morison’s pills—but I haven’t any about me.”

“Glad of it,” said the smoker, casting a long puff in the other’s face.

“Poor wretch!” sighed the compassionate man. “He is beyond human aid. Heaven help the widow and the fatherless—he looks like a family man!”

“I were not to blaame,” said the waggoner.[Pg 11] “The woife and childerin can’t coom upon I.”

“Does anyone know who he is?” inquired the coachman, but there was no answer.

“Maybe the gemman has a card or summut,” said the gentleman from the inside.

“Is there no house near?” inquired the lady.

“For to get a shutter off on,” added the gentleman.

“Ought we not to procure a postchaise,” inquired a gentleman’s footman.

“Or a shell, in case,” suggested the man from the dicky.

“Shell be hanged!” said the sufferer, in a tone that made us all jump a yard backward. “Stick me up agin the milestun—there, easy does it—that’s comfortable—and now tell me, and no nonsense,—be I flat?”

“A little pancakey,” said the man with the cigar.

“I say,” repeated the sufferer, with some earnestness, “be I flat—quite flat—as flat like as a sheet of paper? Yes or no?”

“No, no, no,” burst from sixteen voices at once, and the assurance seemed to take as great a load off his mind as had lately passed over his body. By an effort he contrived to get up and sit upon the milestone, from which he waved us a good-bye, accompanied by the following words:—

“Gentlefolk, my best thanks and my sarvice to you, and a pleasant journey. Don’t consarn yourselves about me, for there’s nothing dangerous. I shall do well, I know I shall; and I’ll tell you what I’ll go upon—if I bean’t flat I shall get round.”

“None despise puns but those who cannot make them.”—SWIFT.

To the Editor of the Comic Annual.

SIR,

As I am but an occasional reader in the temporary indulgence of intellectual relaxation, I have but recently become[Pg 12] cognizant of the metropolitan publication of Mr. Murray’s Mr. Croker’s Mr. Boswell’s Dr. Johnson: a circumstance the more to be deprecated, for if I had been simultaneously aware of that amalgamation of miscellaneous memoranda I could have contributed a personal quota of characteristic colloquial anecdotes to the biographical reminiscences of the multitudinous lexicographer, which although founded on the basis of indubitable veracity, has never transpired among the multifarious effusions of that stupendous complication of mechanical ingenuity, which, according to the technicalities in usage in our modern nomenclature, has obtained the universal cognomen of the press. Expediency imperiously dictates that the nominal identity of the hereditary kinsman, from whom I derive my authoritative responsibility, shall be inviolable and umbrageously obscured; but in future variorum editions his voluntary addenda to the already inestimable concatenation of circumstantial particularisation might typographically be discriminated from the literary accumulations of the indefatigable Boswell and the vivacious Piozzi, by the significant classification of Boz, Poz, and Coz.

In posthumously eliciting and philosophically elucidating the phenomena of defunct luminaries, whether in reference to corporeal, physiognomical, or metaphysical attributes, justice demands the strictest scrupulosity, in order that the heterogeneous may not preponderate over the homogeneous in the critical analysis. Metaphorically speaking, I am rationally convinced that the operative point I am about to develop will remove a pertinacious film from the eye of the biographer of the memorable Dr. Johnson; and especially with reference to that reiterated verbal aphorism so preposterously ascribed to his conversational inculcation, namely, that “he who would make a pun would pick a pocket;” however irrelevant such a doctrinarian maxim to the irrefragable fact, that in that colossal monument of etymological erudition erected by the stupendous Doctor himself (of course implying his inestimable Dictionary), the paramount[Pg 13] gist, scope, and tendency of his laborious researches was obviously to give as many meanings as possible to one word. In order, however, to place hypothesis on the immutable foundation of fact, I will, with your periodical permission, adduce a few Johnsonian repartees from my cousin’s anecdotical memorabilia, which will perspicuously evolve the synthetical conclusion, that the inimitable author of Rasselas did not dogmatically predicate such an aggravated degree of moral turpitude in the perpetration of a double entendre.

Apologistically requesting indulgence for the epistolary laxity of an unpremeditated effusion,

I remain, Sir,

Your very humble obedient servant,

SEPTIMUS REARDON.

Lichfield, October 1, 1833.

“Do you really believe, Dr. Johnson,” said a Lichfield lady, “in the dead walking after death?”—“Madam,” said Johnson, “I have no doubt on the subject; I have heard the Dead March in Saul.” “You really believe then, Doctor, in ghosts?”—“Madam,” said Johnson, “I think appearances are in their favour.”

The Doctor was notoriously very superstitious. The same lady once asked him—“if he ever felt any presentiment at a winding-sheet in the candle.”—“Madam,” said Johnson, “if a mould candle, it doubtless indicates death, and that somebody will go out like a snuff; but whether at Hampton Wick or in Greece, must depend upon the graves.”

Dr. Johnson was not comfortable in the Hebrides. “Pray, Doctor, how did you sleep?” inquired a benevolent Scotch hostess, who was so extremely hospitable that some hundreds always occupied the same bed.—“Madam,” said Johnson, “I had not a wink the whole night long; sleep seemed to flee from my eyelids, and to bug from all the rest of my body.”

The Doctor and Boswell once lost themselves in the Isle of[Pg 14] Muck, and the latter said they must “spier their way at the first body they met.” “Sir,” said Dr. Johnson, “you’re a scoundrel: you may spear anybody you like, but I am not going to ‘run a-Muck and tilt at all I meet.’”

“What do you think of whiskey, Dr. Johnson?” hiccupped Boswell after emptying a sixth tumbler of toddy. “Sir,” said the Doctor, “it penetrates my very soul like ‘the small-still voice of conscience,’ and doubtless the worm of the still is the ‘worm that never dies.’” Boswell afterwards inquired the Doctor’s opinion on illicit distillation, and how the great moralist would act in an affray between the smugglers and the Excise. “If I went by the letter of the law, I should assist the Customs, but according to the spirit I should stand by the contrabands.”

The Doctor was always very satirical on the want of timber in the North. “Sir,” he said to the young Laird of Icombally, who was going to join his regiment,[Pg 15] “may Providence preserve you in battle, and especially your nether limbs. You may grow a walking-stick here, but you must import a wooden leg.” At Dunsinane the old prejudice broke out. “Sir,” said he to Boswell, “Macbeth was an idiot; he ought to have known that every wood in Scotland might be carried in a man’s hand. The Scotch, Sir, are like the frogs in the fable: if they had a Log they would make a King of it.”

Boswell one day expatiated at some length on the moral and religious character of his countrymen, and remarked triumphantly that there was a Cathedral at Kirkwall, and the remains of a Bishop’s Palace. “Sir,” said Johnson, “it must have been the poorest of Sees: take your Rum and Egg and Mull altogether, and they won’t provide for a Bishop.”

East India company is the worst of all company. A Lady fresh from Calcutta once endeavoured to curry Johnson’s favour by talking of nothing but howdahs, doolies, and bungalows, till the Doctor took, as usual, to tiffin. “Madam,” said he, in a tone that would have scared a tiger out of a jungle, “India’s very well for a rubber or for a bandana, or for a cake of ink, but what with its Bhurtpore, Pahlumpore, Barrackpore, Hyderapore, Singapore, and Nagpore, its Hyderabad, Astrabad, Bundlebad, Sindbad, and Guzzaratbadbad, it’s a poor and bad country altogether.”

Master M., after plaguing Miss Seward and Dr. Darwin, and a large tea party at Lichfield, said to his mother that he would be good if she would give him an apple. “My dear child,” said the parent, feeling herself in the presence of a great moralist, “you ought not to be good on any consideration of gain, for ‘virtue is its own reward.’ You ought to be good disinterestedly, and without thinking what you are to get for it.” “Madam,” said Dr. Johnson, “you are a fool; would you have the boy good for nothing?”

The same lady once consulted the Doctor on the degree of turpitude to be attached to her son’s robbing an orchard.[Pg 16] “Madam,” said Johnson, “it all depends upon the weight of the boy. I remember my schoolfellow Davy Garrick, who was always a little fellow, robbing a dozen of orchards with impunity, but the very first time I climbed up an apple tree, for I was always a heavy boy, the bough broke with me, and it was called a judgment. I suppose that’s why Justice is represented with a pair of scales.”

Caleb Whitefoord, the famous punster, once inquired seriously of Dr. Johnson whether he really considered that a man ought to be transported, like Barrington, the pickpocket, for being guilty of a double meaning. “Sir,” said Johnson, “if a man means well, the more he means the better.”

“Do you never deviate?”—JOHN BULL.

IT was on the evening of the 7th of November, 18—, that I went by invitation to sup with my friend P., at his house in Highstreet, Mary-le-bone. The only other person present was a Portuguese, by name Senor Mendez, P.’s mercantile agent at Lisbon, a person of remarkably retentive memory, and most wonderful power of description. The conversation somehow turned upon the memorable great earthquake at Lisbon, in the year of our Lord——, and Senor Mendez, who was residing at that time in the Portuguese capital, gave us a very lively picture—if lively it may be called—of the horrors of that awful convulsion of nature. The picture was dreadful; the Senor’s own house, a substantial stone mansion, was rent from attic to cellar: and the steeple of his parish church left impending over it at an angle surpassing that of the famous Leaning Tower of Bologna!

The Portuguese had a wonderfully expressive countenance, with a style of narration indescribably vivid; and as I listened with the most intense interest, every dismal circumstance of the calamity became awfully distinct to my apprehension. I could hear the dreary ringing of the bells, self-tolled from the rocking of the churches; the swaying to and fro of the steeples themselves, and the unnatural heavings and swellings of the Tagus, were vividly before me. As the agitations increased, the voice of the Senor became awfully tremulous, and his seat seemed literally to rock under him. I seemed palsied, and could see from P.’s looks that he was similarly affected. To conceal his disorder, he kept swallowing large gulps from his rummer, and I followed his example.

This was only the first shock;—the second soon followed, and, to use a popular expression, it made us both[Pg 18] “shake in our shoes.” Terrific, however, as it was, the third was more tremendous; the order of nature seemed reversed; the ships in the Tagus sank to the bottom, and their ponderous anchors rose to the surface; volcanic fire burst forth from the water, and water from dry ground; the air, no longer elastic, seemed to become a stupendous solid; swaying to and fro, and irresistibly battering down the fabrics of ages; hollow rumblings and moanings as from the very centre of the world, gave warning of deafening explosions, which soon followed, and seemed to shake the very stars out of the sky. All this time the powerful features of the Senor kept working, in frightful imitation of the convulsion he was describing, and the effect was horrible; I saw P. quiver like an aspen—there seemed no such thing as terra firma. Our chairs rocked under us; the floor tossed and heaved; the candles wavered, the windows clattered, and the teaspoons rang again, as our tumblers vibrated in our hands.

Senor Mendez at length concluded his narrative, and shortly took leave; I staid but a few minutes after him, just to make a remark on the appalling character of the story, and then departed myself,—little thinking, that any part of the late description was to be so speedily realised by my own experience!

The hour being late, and the servants in bed, P. himself accompanied me to the door. I ought to remark here that the day had been uncommonly serene—not a breath stirring, as was noticed on the morning of the great catastrophe at Lisbon; however, P. had barely closed the door, when a sudden and violent motion of the earth threw me from the step on which I was standing, to the middle of the pavement; I had got partly up when a second shock, as smart as the first, threw me again on the ground. With some difficulty I recovered my legs a second time, the earth in the mean time heaving about under me like the deck of a ship at sea. The street lamps, too, seemed violently agitated, and the houses nodded over me as if they[Pg 19] would fall every instant. I attempted to run, but it was impossible; I could barely keep on my feet. At one step I was dashed forcibly against the wall; at the next I was thrown into the road; as the motion became more violent I clung to a lamp-post, but it swayed with me like a rush. A great mist came suddenly on, but I could perceive people hurrying about, all staggering like drunken men; some of them addressing me, but so confusedly as to be quite unintelligible; one—a lady—passed close to me in evident alarm: seizing her hand, I besought her to fly with me from the falling houses, into the open fields; what answer she made I know not, for at that instant, a fresh shock threw me on my face with such violence as to render me quite insensible. Providentially, in this state I attracted the notice of some of the night police, who humanely deposited me, for safety, in St. Anne’s watch-house, till the following morning; when being sufficiently recovered to give a collected account of that eventful evening, the ingenious Mr. W., of the Morning Herald, was so much interested by my narrative that he kindly did me the favour of drawing it up for publication in the following form.

Police Intelligence.—Bow Street.

“This morning a stout country gentleman, in a new suit of[Pg 20] mud, evidently town made, was charged with having walked Waverly over-night till he got his Kennelworth in a gutter in Mary-le-bone. The Jack-o’-lanthorn who picked him up could make nothing out of him, but that he was some sort of a Quaker, and declared that the whole country was in a shocking state. He acknowledged having taken rather too much Lisbon; but according to Mr. Daly, he sniffed of whiskey ‘as strong as natur.’ The defendant attempted with a sotto voce (Anglice, a tipsy voice), to make some excuse, but was stopped and fined in the usual sum, by Sir Richard. He found his way out of the office, muttering that he thought it very hard to have to pay five hogs for being only as drunk as one.”

“The rain it raineth every day.”

“To keep without a reef in a gale of wind like that—Jock was the only boatman on the Firth of Tay to do it!”—

“He had sail enough to blow him over Dundee Law.”—

“She’s emptied her ballast and come up again,—with her sails all standing—every sheet was belayed with a double turn.”

I give the sense rather than the sound of the foregoing speeches, for the speakers were all Dundee ferry-boatmen, and broad Scotchmen, using the extra-wide dialect of Angus-shire and Fife.

At the other end of the low-roofed room, under a coarse white sheet, sprinkled with sprigs of rue and rosemary, dimly lighted by a small candle at the head, and another at the feet, lay the[Pg 25] object of their comments—a corpse of startling magnitude. In life, poor Jock was of unusual stature, but stretching a little, perhaps, as is usual in death, and advantaged by the narrow limits of the room, the dimensions seemed absolutely supernatural. During the warfare of the Allies against Napoleon, Jock, a fellow of some native humour, had distinguished himself by singing about the streets of Dundee, ballads, I believe his own, against old Boney. The nick-name of Ballad-Jock was not his only reward; the loyal burgesses subscribed among themselves, and made him that fatal gift, a ferry-boat, the management of which we have just heard so seriously reviewed. The catastrophe took place one stormy Sunday, a furious gale blowing against the tide, down the river—and the Tay is anything but what the Irish call “weak tay,” at such seasons. In fact, the devoted Nelson, with all sails set,—fair-weather fashion,—caught aback in a sudden gust,—after a convulsive whirl capsized, and went down in forty fathoms, taking with her two-and-twenty persons, the greater part of whom were on their way to hear the celebrated Dr. Chalmers,—even at that time highly popular,—though preaching in a small church at some obscure village, I forget the name, in Fife. After all the rest had sunk in the waters, the huge figure of Jock was observed clinging to an oar, barely afloat,—when some sufferer probably catching hold of his feet, he suddenly disappeared, still grasping the oar, which afterwards springing upright into the air, as it rose again to the surface, showed the fearful depth to which it had been carried. The body of Jock was the last found; about the fifth day, it was strangely enough deposited by the tide almost at the threshold of his own dwelling, at the Craig, a small pier or jetty, frequented by the ferry-boats. It had been hastily caught up, and in its clothes laid out in the manner just described, lying as it were in state, and the public, myself one, being freely admitted, as far as the room would hold, it was crowded by[Pg 26] fish-wives, mariners, and other shore-haunters, except a few feet next the corpse, which a natural awe towards the dead kept always vacant. The narrow death’s door was crammed with eager listening and looking heads, and by the buzzing without, there was a large surplus crowd in waiting before the dwelling for their turn to enter it.

On a sudden, at a startling exclamation from one of those nearest the bed, all eyes were directed towards that quarter. One of the candles was guttering and sputtering near the socket,—the other just twinkling out, and sending up a stream of rank smoke,—but by the light, dim as it was, a slight motion of the sheet was perceptible just at that part where the hand of the dead mariner might be supposed to be lying at his side! A scream and shout of horror burst from all within, echoed, though ignorant of the cause, by another from the crowd without. A general rush was made towards the door, but egress was impossible. Nevertheless horror and dread squeezed up the company in the room to half their former compass: and left a far wider blank between the living and the dead! I confess at first I mistrusted my sight; it seemed that some twitching of the nerves of the eye, or the flickering of the shadows, thrown by the unsteady flame of the candle, might have caused some optical delusion; but after several minutes of sepulchral silence and watching, the motion became more awfully manifest, now proceeding slowly upwards, as if the hand of the deceased, still beneath the sheet, was struggling up feebly towards his head. It is possible to conceive, but not to describe, the popular consternation,—the shrieks of women,—the shouts of men—the struggles to gain the only outlet, choked up and rendered impassable by the very efforts of desperation and fear!—Clinging to each other, and with ghastly faces that dared not turn from the object of dread, the whole assembly backed with united force against the opposite wall, with a convulsive energy that[Pg 27] threatened to force out the very side of the dwelling—when, startled before by silent motion, but now by sound,—with a smart rattle something fell from the bed to the floor, and disentangling itself from the death drapery, displayed—a large pound Crab!—The creature, with some design, perhaps sinister, had been secreted in the ample clothes of the drowned seaman, but even the comparative insignificance of this apparition gave but little alleviation to the superstitious horrors of the spectators, who appeared to believe firmly, that it was only the Evil One himself, transfigured.—Wherever the crab straddled sidelong, infirm beldame and sturdy boatman equally shrank and retreated before it,—aye, even as it changed place, to crowding closely round the corpse itself, rather than endure its diabolical contact. The crowd outside, warned by cries from within, of the presence of Mahound, had by this time retired to a respectful distance, and the crab, doing what herculean sinews had failed to effect, cleared itself a free passage through the door in a twinkling, and with natural instinct began crawling as fast as he could clapperclaw, down the little jetty before mentioned that led into his native sea. The Satanic Spirit, however disguised, seemed everywhere distinctly recognised. Many at the lower end of the Craig lept into their craft; one or two even into the water, whilst others crept as close to the verge of the pier as they could, leaving a thoroughfare—wide as “the broad path of honour,”—to the Infernal Cancer. To do him justice, he straddled along with a very unaffected unconsciousness of his own evil importance. He seemed to have no aim higher than salt water and sand, and had accomplished half the distance towards them, when a little decrepit poor old sea-roamer, generally known as “Creel Katie,” made a dexterous snatch at a hind claw, and before the Crab-Devil was aware, deposited him in her patchwork apron, with an “Hech, Sirs, what for are ye gaun to let gang siccan a braw partane?” In vain a hundred voices shouted[Pg 28] out, “Let him bide, Katie,—he’s no cannie;” fish or fiend, the resolute old dame kept a fast clutch of her prize, promising him, moreover, a comfortable simmer in the mickle pat, for the benefit of herself and that “puir silly body the gudeman:” and she kept her word. Before night the poor Devil was dressed in his shell, to the infinite horror of all her neighbours. Some even said that a black figure, with horns, and wings, and hoofs, and forky tail, in fact old Clooty himself, had been seen to fly out of the chimney. Others said that unwholesome and unearthly smells, as of pitch and brimstone, had reeked forth from the abominable thing, through door and window. Creel Kate, however, persisted, aye, even to her dying day and on her deathbed, that the Crab was as sweet a Crab as ever was supped on; and that it recovered her old husband out of a very poor low way,—adding, “And that was a thing, ye ken, the Deil a Deil in the Dub of Darkness wad hae dune for siccan a gude man, and kirk-going Christian body, as my ain douce Davie.”

Is a Blackamoor turned outside in. His skin is fair, but his lining is utter dark; his eyes are like shotten stars,—mere jellies; or like mock-painted windows since the tax upon daylight: what his mind’s eye can be, is yet a mystery with the learned, or if he hath a mental capacity at all—for, “out of sight is out of mind.”

Wherever he stands, he is antipodean, with his midnight to your noon. The brightest sunshine serves only to make him the gloomier object; like a dark house at a general illumination. When he stirs, it is like a Venetian blind, being pulled up and down by a string; he is a human kettle tied to a dog’s tail, and with much of the same tin twang in his tone. With botanists he is a species of solanum, or night-shade, whereof the berries[Pg 29] are in his eyes;—amongst painters he is only contemned, for his ignorance of clare-obscure; but by musicians marvelled at for playing, ante-sight, on an invisible fiddle. He stands against a wall with his two blank orbs, like a figure in high relief, howbeit but seldom relieved; and though he is fond of getting pence, yet he is confessedly blind to his own interest.

In his religion he is a materialist, putting no faith but in things palpable. In politics, no visionary; in his learning a smatterer, his knowledge of all being superficial; in his age a child, being yet in leading-strings; in his life immortal, for death may lengthen his night, but can put no end to his days; in his courage, heroic, for he winks at no danger; in his pretensions humble, confessing that he is nothing, even in his own eyes; in his malady hopeless, for eyes of looking-glass would not[Pg 30] help him to see. To conclude—he is pitied by the rich, relieved by the poor, oppressed by the beadle, and horse-whipped by the fox-hunter, for not giving the view holloa!

A PATHETIC BALLAD.

“Twine ye, twine ye.”—SIR W. SCOTT.

IT was my good fortune once, at Charing Cross, to witness the feeding of the Boa Constrictor; rather a rare occurrence, and difficult of observation, the reptile not being remarkable for[Pg 34] the regularity of its dinner-hour; and a very considerable interval intervenes, as the world knows, between Gorge the First, and Gorge the Second, Gorge the Third, and Gorge the Fourth. I was not in time to see the serpent’s first dart at the prey; she had already twisted herself round her victim,—a living White Rabbit—who with a large dark eye gazed piteously through one of the folds, and looked most eloquently that line in Hamlet—

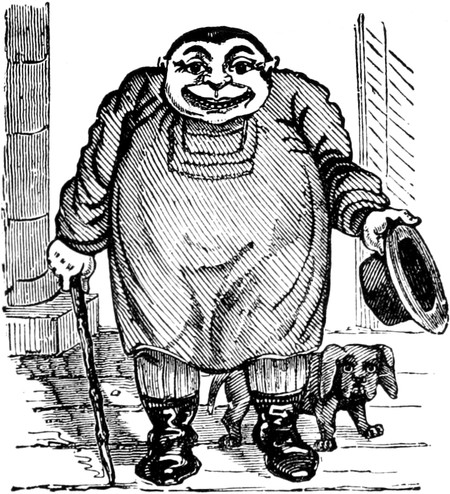

The Snake evidently only embraced him in a kill-him-when-I-want-him manner, just firmly enough to prevent an escape—but her lips were glued on his, in a close “Judas’ kiss.” So long a time elapsed, in this position, both as marble-still as poor old Laocoon with his leaches on, that I really began to doubt the tale of the Boa’s ability in swallowing; and to associate the hoax before me, with that of the Bottle Conjuror. The head of the snake, in fact, might have gone without difficulty into a wine-glass, and the throat, down which the rabbit was to pro[Pg 35]ceed whole, seemed not at all thicker than my thumb. In short, I thought the reported cram was nothing but stuff, and the only other visitor declared himself of my opinion: “If that ’ere little wiper swallows up the rabbit, I’ll bolt um both!” and he seemed capable of the feat. He looked like a personification of what Political Economists call the Public Consumer; or, Geoffrey Crayon’s Stout Gentleman, seen through Carpenter’s Solar Microscope; a genuine Edax Rerum; one of your devourers of legs of mutton and trimmings, for wagers: the delight of eating-houses, and the dread of ordinaries. The contrast was whimsical, between his mountain of mummy, and the slim Macaroni figure of the Snake, the reputed Glutton. However, the Boa began at last to prepare for the meal, by lubricating the muzzle of the Rabbit with her slimy tongue, and then commenced in earnest,

The process was tedious—“one swallow makes a summer”—but it gradually became apparent, from the fate of the head, that the whole body might eventually be “lost in the Serpentine.” The Reptile, indeed, made ready for the rest of the interment by an operation rather horrible. On a sudden, the living cable was observed, as a sailor would say, to haul in her slack, and with a squeeze evincing tremendous muscular power, she reduced the whole body into a compass that would follow the head with perfect ease. It was like a regular smash in business:—the poor rabbit was completely broken—and the wily winder-up of his affairs recommenced paying herself in full. It was a sorry sight and sickening. As for the Stout Gentleman, he could not control his agitation. His eyes rolled and watered; his jaws constantly yawned like a panther’s; and his hands with a convulsive movement were clasped every now and then on his stomach;—but when the whole rabbit was smothered in snake, he could[Pg 36] restrain himself no longer, and rushed out of the menagerie as if he really expected to be called upon to fulfil his rash engagement. Anxious to ascertain the true nature of the impulse, I hurried in pursuit of him, and after a short but sharp chase, I saw him dash into the British Hotel, and overheard his familiar voice—the same that had promised to swallow both Snake and Snack—bellowing out, guttural with hunger—“Here!—waiter!—Quick!—Rabbits in onions for two!”

“THE Nelson,” I repeated to myself, as I read that illustrious name on the dicky of the vehicle—“the Nelson.” My fancy instantly converted the coach into a first-rate, the leaders and wheelers into sea-horses, the driver into Neptunus, brandishing a trident, and the guard into a Triton blowing his wreathed shell. There was room for one on the box, so I climbed up, and took my seat beside the coachman. “Now, clap on all sail,” said I, audibly, “I am proud to be one of the crew of the great Nelson, the hero of Aboukir.”

“Begging your pardon, Sir,” said the coachman, “the Hero ain’t a booker at Mrs. Nelson’s: it goes from some other yard.” Gracious powers! what a tumble down stairs for an idea! As for mine, it pitched on its head, as stunned and stupefied as if it had rolled down the whole flight at the Monument. “I have made a Bull, indeed,” I exclaimed, as the noted inn at Aldgate occurred to my memory; “but we are the slaves of association,” I continued, addressing the coachman, “and the name of Nelson identified itself with the Union Jack.”

“I really can’t say,” replied the coachman, very civilly, “whether the name of Mrs. Nelson is down to the Slave Associations or not: but as for Jack, if you mean Jack Bunce, he’s been off the Union these six months. Too fond of the Bar, Sir” (here he tipped me the most significant of winks),[Pg 49] “to keep his seat on the Bench.”

“I alluded, my good fellow, to Nelson, the wonder of the maritime world—the dauntless leader when yard was opposed to yard, and seas teemed with blood.”

“We’re all right—as right as a trivet,” said the coachman, after a pause of perplexity; “I thought our notions were getting rather wide apart, and that one of us wanted putting straight; but I see what you mean, and quite go along with your opinion, step for step. To be sure, Mrs. Nelson has done the world and all for coaching; and the Wonder is the crack of all the drags in London, and so is the Dauntless, let yard turn out agin yard, as you say, any day you like. And as for leaders, and teams full of blood, there’s as pretty a sprinkling of blood in the tits I’m now tooling of—”

“The vehicles of the proprietress, and the appearance of the animals, with their corresponding caparisons,” said I, “have often gratified my visual organs and elicited my mental plaudits.”

“That’s exactly what I says,” replied the coachman, very briskly, “there’s no humbug nor no nonsense about Mrs. Nelson. You never see her a standing a-foaming and fretting in front o’ the Bank, with a regular mob round her, and looking as if she’d bolt with the Quicksilver. And you never see her painted all over her body, wherever there’s room for ’em, with Saracen Heads, and Blue Boars, and Brown Bears, from her roller bolts to her dicky and hind boot. She’s plain and neat, and nothin’ else—and is fondest of having her body of a claret colour, pick’d out with white, and won’t suffer the Bull, no where, except on the back-gammon board.”

I know not how much further the whimsical description might have gone, if a strapping, capless, curly-headed lass, running with all her might and main, had not addressed a screaming retainer to the coachman. With some difficulty he pulled up, for he had been tacitly giving me a proof that the craft of his Nelson was a first-rate, with regard to its rate of travelling.

“If you please, Mr. Stevens,” said the panting damsel, holding up something towards the box—“if you please, Mr. Stevens, mother’s gone to Lonnon—in the light cart—and will you be so kind as to give her—her linchpin.”

Mr. Stevens took the article with a smile, and I fancied with a sly squeeze of the hand that delivered it.

“If such a go had been anyone’s but your mother’s, Fanny,” he slyly remarked, “I should have said it was somebody in love.” The Dispatch was too strictly timed to allow of further parley; the horses broke, or were rather broken, into a gallop, in pursuit of the mother of Fanny, the Flower of Waltham; and the pin secretly acting as a spur, we did the next five mile in something like twenty minutes.

In spite, however, of this unusual speed, we never overtook Mrs. Merryweather and her cart till we arrived at the Basing-House, where we found her chirping over a cup of ale; as safe and sound as if linchpins had never been invented; in fact, she made as light of the article, when it was handed to her, as if it had been only a pin out of her gown!

“Well, I must say one thing for Mrs. Nelson,” said our coachman, as he resumed his seat on the box,[Pg 51] “and that’s this. There’s no pinning at the Bull. She sets her face against everything but the patent boxes. She may come to a runaway with a bolter—or drop the ribbons—or make a mistake in clearing a gate, by being a little lushy—but you’ll never see Mrs. Nelson lying flat on her side in the middle of the road, with her insides gone to smash, and her outsides well distributed, because she’s been let go out of the yard without one of her pins.”

GENTLE READERS,

For the present month, there must be what Dr. Johnson called a solution of continuity in my “Literary Reminiscences.” Confined to my chamber by what ought to be termed roomatism—then attacked by my old livery complaint—and finally, by a minor, but troublesome malady, the Present has too much prevailed over the Past, to let me indulge in any retrospective reviews. In such cases, on the stage, when a Performer is unable to support his character, a substitute is usually found to read the part; but, unfortunately, in the present case there is no part written, and consequently it cannot be read. But apropos of theatricals—there is an anecdote on point.

In the Olympic days of the great Elliston, there was one evening a tremendous tumult at his Theatre, in consequence of the absence of a favourite performer. One man in the pit—a Butcher—was especially vociferous in his cry for “Carl! Carl! Carl!” Others called for the Manager, who duly made his appearance, and black as the weather looked, he was the very sort of pilot to weather the storm. With one of his princely bows[Pg 53] he proceeded to address the House. “Ladies and Gentlemen—but by your leave I will address myself to a single individual. I will ask that gentleman (pointing to the vociferous Butcher) what right he has to demand the appearance of Mr. Carl?”

“’Cos,” said the Butcher, “’cos he’s down in the Bill.” Such an undeniable answer would have staggered any other Manager than Elliston, but he was not easily to be disconcerted. “Because he is down in the bill!” he echoed, in a tone of the loftiest indignation: “Ladies and Gentlemen, the Mr. Carl, so unseasonably, so vociferously and so unfeelingly called for, is at this very moment labouring under severe illness—he is in bed. And let me ask, is a man, a fellow-creature, a human being, to be torn from his couch, from his home, on a cold night, from the affectionate attentions of his wife and family, at the risk of his valuable life perhaps, to go through a fatiguing part because he happens to be DOWN IN THE BILL?” [Cries of “Shame, shame!” from all parts of the house.] “And yet, ladies and gentlemen, there stands a man—if I may call him so—a Butcher, that for his own selfish gratification—the amusement of a few short hours—would risk the very existence of a deserving member of society, a good husband, father, friend, and one of your favourite actors, and all, forsooth, because he is DOWN IN THE BILL!” [Universal hooting, with cries of “Turn him out.”] “By all means,” acquiesced the Manager, with one of his best bows—and the indignant pittites actually hooted and kicked their own champion out of the theatre, as something more than a Butcher, and less than a Christian.

Now I am myself, gentle readers, in the same predicament with Mr. Carl. Like him I am an invalid—and like him I am unfortunately down in the Bill. It would not become me to set forth my own domestic or social virtues, or to hint what sort of gap my loss would make in society—still less would it consist with modesty to compare myself with a favourite actor—but as[Pg 54] a mere human being I throw myself on your mercy, and ask, in common charity, would you have had me leave my warm bed, to shiver in a printer’s damp sheets, at the risk of my reputation perhaps, and for the mere amusement of some half hour, or more probably for no amusement at all—simply because I was “down in the Bill?”

But there is no such Butcher, or Butcheress, or little Butcherling, amongst you; and by your good leave and patience, the instalment of my Reminiscences that is over due, shall be paid with interest in the NEXT NUMBER.

Dreadful Fire—Destruction of both Houses of Parliament—The Speaker’s House gutted—Reports of Incendiarism.

IT is our unexpected lot to announce that the Houses of Lords and Commons, so often threatened with combustion, are in a state of actual ignition. At this moment, both fabrics are furiously burning. We are writing this paragraph without the aid of lamp or candles; by the mere reflection of the flames. Nothing is known of the origin of the fire, although it is throwing a light upon everything else.—Evening Star.

The devouring element which destroyed Covent Garden and Drury Lane, the Royalty and the Pantheon, has made its appearance on a new stage, equally devoted to declamatory elocution. St. Stephen’s Chapel is in flames! The floor which was trodden by the eloquent legs of a Fox, a Burke, a Pitt, and a Sheridan, is reduced to a heap of ashes; and the benches which sustained the Demosthenic weight of a Wyndham, a Whitbread, and a Wilberforce, are a mere mass of charcoal. The very roof that re-echoed the classicalities of Canning is nodding to its fall. In Parliamentary language, Fire is in possession of the House:[Pg 56] the Destructive spirit is on its legs, and the Conservative principle can offer but a feeble opposition.—Daily Post.

The blow is struck. What we have long foreseen has come to pass. Incendiarism triumphs! The whole British Empire, as represented by the three estates, is in a blaze! The Throne, the Lords, and the Commons, are now burning. The cycle is complete. The spirit of Guy Fawkes revives in 1834!

England seems to have changed places with Italy; London with Naples. We stand hourly on the brink of a crater; every step we take is on a solfaterra—not a land of Sol Fa, as some musical people would translate it; but a frail crust, with a treacherous subsoil of ardent brimstone! At length the eyes of our rulers are opened; but we must ask, could nothing short of such an eruption awaken them to a sense of the perilous state of the country? For weeks, nay, months past, at the risk of being considered alarmists, we have called the attention of the legislature and magistracy to a variety of suspicious symptoms and signs of the times, and in particular to the multiplied chemical inventions, for the purpose of obtaining instantaneous lights. Well are certain matches or fire-boxes called Lucifers, for they may be applied to the most diabolical purposes! The origin of the fire cannot raise the shadow of a doubt in any reasonable mind. Accident is out of the question. Tell us not of tallies. We have just tried our milk-woman’s, and it contained so much water, that nothing could make it ignite.—Britannic Guardian.

The Houses of Parliament are in flames. We shall stop the press to give full particulars. Our reporters are at the spot, and Mons. C——, the celebrated Salamander, is engaged to give a description of the blazing interiors, exclusively for this journal.—Daily Times.

From a Correspondent.

On Thursday evening, towards seven o’clock, I was struck by the singular appearance of the moon silvering the opposite[Pg 57] chimneys with a blood-red light, a lunar phenomenon, which I conceived belonged only to our theatres. It speedily occurred to me that there must be a conflagration in my vicinity, and after a little hunting by scent as well as sight, I found myself in front of the Houses of Lords and Commons, which were burning with a rapidity and brilliancy that I make bold to say did not always characterise their proceedings. By favour of my natural assurance, which seemed to identify me with the firemen, I was allowed to pass through the lines of guards and policemen, who surrounded the blazing pile, and was thus enabled to select a favourable position for overlooking the whole scene. It was an imposing sight. The flames rose from the Peers’ in a volume, as red as the Extraordinary Red Book, and the House of Commons was not at all behind-hand in voting supplies of timber and other combustibles. Westminster Hall reminded me vividly of a London cry, “Hall hot, Hall hot,” that was familiar in our childhood—and the Gothic architecture of the Abbey seemed unusually florid. Instead of dingy stone, the venerable pile appeared to be built of the well-baked brick of the Elizabethan age. Indeed, so red-hot was its aspect, that it led to a ludicrous misapprehension on the part of the populace. A procession, bearing several male and female figures in a state of insensibility, naturally gave rise to the most painful conjectures, inferring loss of human life by the devouring element, but I have reason to believe it was only the Dean and Chapter saving the Wax-Work. As far as my own observation went, the first object carried out certainly bore a strong resemblance to General Monk.

In the meantime a select party had effected an entrance into the Hall, but not without some serious delay, occasioned, I believe, by somebody within bringing the wrong key, that belonged to a tea-caddy. However, at last they entered, and I followed their example. The first person I beheld was the[Pg 58] veteran Higginbottom, so unfairly, but facetiously, put to death by the authors of the Rejected Addresses; for no man is more alive to his duty. But he was sadly hampered. First came one Hon. Gent. said to be Mr. Morrison, and insisted on directing the Hose department; and next arrived a noble Lord from Crockford’s, who wouldn’t sit out, but persisted in taking a hand, and playing, though every body agreed that he played too high. I mention this, because some of the journals have imputed mismanagement to the engines, and have insinuated that the pipes wanted organising; indeed, I myself overheard a noble director of the Academy of Music lamenting that the firemen did not “play in concert.”

The same remark applies with greater force to the House of Commons. Here all was confusion worse confounded, and Higginbottom’s station was enviable, compared with that of[Pg 59] some of the poor fellows in St. Stephen’s Chapel. A considerable number of members had arrived, and without any attention to their usual parliamentary rules, were all making motions at once, which nobody seconded. The most prominent, I was informed, were Mr. Hume, Mr. O’Connell, Mr. Attwood, Mr. Buckingham, Mr. Pease, Sir Andrew, and Mr. Buxton—the latter almost covered with blacks. The clamour was terrific, and I really expected that the poor foremen who held the pipes would be torn in pieces. Every body wanted to command the Coldstream. Nothing but shouts of “Here! here! here!” answered like an Irish echo by cries of “There! there! there!” “Oh, save my savings!”—“My poor, Poor Bill!” “More water—more water for my Drunkenness!” “Work awa, lads, work awa—it’s no the Sabbath, and ye may just play at what ye like!”

In pleasing contrast to this tumult, was the unusual and cordial unanimity of the members of both Houses, in rescuing whatever was portable from the flames. It was a delightful novelty to see the Lords helping the Commons in whatever they moved or carried. No party spirit—no Whig, pulling at one leg of the table, whilst a Tory tugged at another in the opposite direction. They seemed to belong to the Hand-in-Hand. Peers and Commoners were alike seen burthened with loads of papers or furniture. Mr. Calvert, in particular, worked like any porter. Of course, in rescuing the papers and parchments, there was no time for inspecting their contents, and some curious results were the consequence. Every body remembers the pathetic story in the Tatler, of the lover who saved a strange lady from a burning theatre, under the idea that he was preserving the mistress of his affections, and some similar mistakes are currently reported to have occurred at the late conflagration—and equally to the chagrin of the parties. I go by hearsay, and cannot vouch for the facts, but it is said that the unpopular Six Acts,[Pg 60] including what I believe is called the Gagging Act, were actually preserved by Mr. Cobbett. Mr. O’Connell saved the Irish Coercion Bill, whilst the Reform Bill was snatched like “a brand out of the fire,” by a certain noble Duke, who resolutely set his face against it in all its stages! Amongst others, Mr. Ricardo saved an old tattered flag, which he thought was “the standard of value.”

However deficient in general combination, and concentration of energies, individual efforts were beyond all praise. The instances of personal exertion and daring were numerous. Mr. Rice worked amidst the flames till he was nearly baked; and everybody expected that Mr. Pease would be parched. The greatest danger was from the melted metal pouring down from the windows and roof. The heads of some of the Hon. Gentle[Pg 61]men were literally nothing but lead. Great apprehensions were entertained of the falling in of one of the walls, which eventually gave way, but fortunately everybody had retreated on the timely warning of a gentleman, Mr. O’Connell, I believe, who declared that he saw a Rent in it.

I did not enter the House of Lords, which was now one mass of glowing fire, but directed my attention towards the Speaker’s mansion, which was partially burning. The garden behind was nearly filled with miscellaneous property—and numbers of well-dressed gentlemen were every moment rushing into the house, from which they issued again, laden with spits, sauce-pans, and other culinary implements. I, myself, saw one zealous individual thus encumbered—with a stew-pan on his head, the meat-screen under one arm, the dripping-pan under the other, the frying-pan in his right hand, the grid-iron in his left, and the rolling-pin in his mouth. Indeed, it is said that every article in the kitchen was saved down to the salt-box; and the cook declares that such was the anxiety to save her she was “cotched up in twelve gentlemen’s arms, and never felt her feet till the corner of Abingdon Street.”

The whole of the Foot Guards were in attendance, as well as a great number of the police, but the thieves had mustered in great force, and there was a good deal of plundering, which was however checked temporarily by a gentleman said to be one of the members and magistrates for Essex, who jumped up on a railing and addressed the populace to the following effect, “How do you hall dare!”

The origin of the fire is involved in much mystery; nor is it correctly ascertained by whom it was first discovered. Some say that one of the serjeants, in taking up the insignia, was astonished to find the mace as hot as ginger. Others relate that a Mr. Spell, or Shell, or Snell, whilst viewing the House, although no dancer, began suddenly, and in his boots, to the[Pg 62] utter amazement of his companions and Mrs. Wright, the housekeeper, to jump and caper like a bear upon a hotted floor. This story certainly seems to countenance a report that the mischief originated in the warming apparatus, an opinion that is very current, but, for my own part, I cannot conceive that the Collective Wisdom, which knows how to lay down laws for us all, should not know how to lay down flues. Rumours of Incendiarism are also very generally prevalent, and stories are in circulation of the finding of half-burnt matches and other combustibles. But these facts rest on very frail foundations. The links said to have been found in the Speaker’s garden have turned out to be nothing but German sausages; and another cock-and-a-bull that has got abroad will probably come to no better end. A Mr. Dudley affirms that he smelt the fire before it broke out, at Cooper’s Hill; but such olfactories are too much like manufactories to be believed.

I am, Sir, your most obedient Servant,

X. Y. Z.

Another Account.

The writer of these lines, who resides in Lambeth, was first awakened to a sense of conflagration by a cry of “Fire” from a number of persons who were running in the direction of Westminster Bridge. Owning myself a warm enthusiast on the subject of ignition, and indeed not having missed a fire for the last fifty years, except one, and that was only a chimney, it may be supposed the exclamation in question had an electric effect. We are all the slaves of some physical bias, strange as it may appear to others with opposite tendencies. It is recorded of some great marshal that he disliked music, but testified the liveliest pleasure at a salvo of artillery or a roll of thunder, and the rumble of an engine has the same effect on the author of these lines. To say I am a guebre, or fire-worshipper, is only to confess the truth. I have a sort of observatory erected on[Pg 63] the roof of my house, from which, if there be a break-out within the circuit of the metropolis, it may be discovered, and before going to bed I invariably visit this look-out.

Every man has his hobby-horse, and, figuratively speaking, mine was always kept harnessed and ready to run to a fire with the first engine. Many a time I have arrived before the turncocks, though I perhaps had to traverse half London, and I scarcely remember an instance that I did not appear long before the water. Habit is second nature—I verily believe I could sniff a conflagration by instinct; and if I was not, I ought to have been, the trainer of the firemen’s dog, which at present attracts so much of the public attention, by his eager running along with the Sun, the Globe, the British, and the Hand-in-Hand.

Of course I have seen a great many fires in my time—Rotherhithe, the theatres, the Custom-house, &c. &c. I remember in the days of Thistlewood and Co., when the metropolis was expected to be set on fire, I slept for three weeks in my clothes in order to be ready for the first alarm; for I had the good fortune to witness the great riots of 1780, when no less than eight fires were blazing at once, and a lamentable sight it was.[Pg 64] I say lamentable, because it was impossible to be present at them all at the same time; but my good genius directed me to Langdale’s the Distiller, which made (excuse the vulgar popular phrase) a very satisfactory flare-up.

The Rotherhithe fire, not the recent little job, but some fifteen or twenty years ago, was also on a grand scale, and very lasting. The engine-pipes were wilfully cut; and I remember some of my friends rallying me on my well-known propensity, jocularly accusing me of lending my knife and my assistance. The Custom-house was a disappointment; it certainly cleared itself effectually, but it was done by day-light, and consequently the long-room fell short of my anticipations. Drury-lane and Covent-garden were better: but I have observed generally that theatres burn with more attention to stage effect. They avoid the noon; a dark night to a fire is like the black letters in a benefit-bill, setting off the red ones.

The destruction of the Kent Indiaman I should like to have witnessed, but contrary to the opinion of many experienced amateurs I conceive the Dartford Mills must have been a failure. Powder magazines make very indifferent conflagrations; they are no sooner on fire than they are off,—all is over before you know where you are, and there is no getting under, which quite puts you out. But fires, generally, are not what they used to be. What with gas, and new police, steam, and one cause or other, they have become what one might call slow explosions. A body of flame bursts from all the windows at once, and before B 25 can call fi-er in two syllables, the roof falls in, and all is over. It was not so in my time. First a little smoke would issue from a window-shutter, like the puff of a cigar, and after a long spring of his rattle, the rheumatic watchman had time to knock double and treble knocks, from No. 9 to No. 35, before a spark made its appearance out of the chimney-pot. The Volunteers had time to assemble under arms, and muffle their[Pg 65] drums, and the bell-ringers to collect in the belfry, and pull an alarm peal backwards. The parish engines even, although pulled along by the pursy churchwardens, and the paralytic paupers, contrived to arrive before the fire fairly broke out in the shape of a little squib-like eruption from the garret-window. The affrighted family, fourteen in number, all elaborately drest in their best Sunday clothes, saved themselves by the street-door, according to seniority, the furniture was carefully removed, and after an hour’s pumping, the fire was extinguished without extending beyond the room where it originated, namely a bed-room on the second floor. Such was the progress in my time of a fire, but it is the fashion now to sacrifice everything to pace. Look at our race-horses, and look at our fox-hounds,—and I will add look at our conflagrations. All that is cared for is a burst—no matter how short, if it be but rapid. The devouring element never sits down now to a regular meal—it pitches on a house and bolts it.

But I am wandering from the point. The announcement of both Houses of Parliament being in flames thrilled through every fibre. It seemed to promise what I may call a crowning event to the Conflagrationary Reminiscences of an Octogenarian. I snatched up my hat, and rushed into the street, at eighty years of age, with the alacrity of eighteen, when I ran from Highgate to Horselydown, to be present at the gutting of a ship chandler’s. As the bard says—

and I could almost have supposed myself a fireman belonging to the Phœnix. My first step into the street discouraged me, the moonlight was so brilliant, and in such cases the most splendid blaze is somewhat “shorn of its beams.” But a few steps reassured me. Even at the Surrey side of the river the sparks and burning particles were falling like flakes of snow—I mean of course the red snow formerly discovered by Captain[Pg 66] Ross, and the light was so great that I could have read the small print of the Police Gazette with the greatest ease, only I don’t take it in. I of course made the best of my way towards the scene, but the crowd was already so dense that I could only attain a situation on the Strand opposite Cotton Gardens, up to my knees in mud. Both Houses of Parliament were at this time in a blaze, and no doubt presented as striking objects of conflagration as the metropolis could offer. I say, “no doubt,”—forgetting jammed against a barge with my back towards the fire, I am unable to state anything on my own authority as an eye-witness, excepting that the buildings on the Surreyside exhibited a glowing reflection for some hours. At last the flowing of the tide caused the multitude to retreat, and releasing me from my retrospective position allowed me to gaze upon the ruins. By what I hear, it was a most imposing sight—but in spite of my Lord Althorpe, I cannot help thinking that Westminster Hall, with its long range, would have made up an admirable fire. Neither can I agree with the many that it was an Incendiary Act, that passed through both houses so rapidly. To enjoy the thing, a later hour and a darker night would certainly have been chosen. Fire-light and moon-light do not mix well:—they are best neat.

I am, Sir, Yours, &c.,

SENEX.

Various Accounts.

WE are concerned to state that Sir Jacob Jubb the new member for Shrops was severely burnt, by taking his seat in the House, on a bench that was burning under him. The danger of his situation was several times pointed out to him, but he replied that his seat had cost him ten thousand pounds, and he wouldn’t quit. He was at length removed by force.—Morning Ledger.

A great many foolish anecdotes of the fire are in circulation.[Pg 67] One of our contemporaries gravely asserts that the Marquis of Culpepper was the last person who left the South Turret, a fact we beg leave to question, for the exquisite reason that noble lord alluded to is at present at Constantinople.—The Real Sun.

We are enabled to state that the individual who displayed so much coolness in the South Turret was Captain Back.—The Public Journal.

It is said that considerable interest was evinced by the members of the House of Commons who were present at the fire, as to the fate of their respective Bills. One honourable gentleman, in particular, was observed anxiously watching the last scintillations of some burnt paper. “Oh, my Sabbath Observances!” he exclaimed, “There’s an end of religion! There go the Parson and Clerk!”—Public Diary.

The Earl of M. had a very narrow escape. His lordship was on the point of kicking a bucket when a labourer rushed forward and snatched it out of the way. The individual’s name is M’Farrel. We understand he is a sober, honest, hard-working man, and has two wives, and a numerous family; the eldest not above a year old.—Daily Chronicle.

The exclamation of a noble lord, high in office, who was very active at the fire, has been very incorrectly given. The words were as follows:—“Blow the Commons! let ’em flare up—but oh,—for a save-all! a save-all.”—Morning News.

The public attention has been greatly excited by the extraordinary statement of a commercial gentleman, that he smelt the fire at the Cock and Bottle, in Coventry. He asserts that he mentioned the fact in the commercial room to a deaf gentleman, and likewise to a dumb waiter, but neither have any recollection of the circumstance. He has been examined before the Common Council, who have elicited that he actually arrived at Coventry on the night in question, by the Tallyho, and the near leader of that coach has been sent for by express.—New Monitor.

We were in error in stating that the Atlas was the first engine at the scene of action. So early as five o’clock Mr. Alderman A. arrived with his own garden engine, and began immediately to play upon the Thames.—British Guardian.

It must have struck everyone who witnessed the operations in the House of Commons, that there was a lamentable want of “order! order! order!” A great many gentlemen succeeded in making pumps of themselves, without producing any check on the flames. The conduct of the military also was far from unexceptionable. On the arrival of the Coldstream at the fire they actually refused to fall in. Many declined to stand at ease on the burning rafters—but what is the public interest to a private?—Public Advertiser.

Monsieur C.’s Account. (Exclusive.)

WHEN I am come first to the fire it was not long burnt up; and I was oblige to walk up and down the floor to keep myself warm. At last, I take my seat on the stove, quite convenient to look about. In the House of Commons there was nobody, and I am all alone. The first thing I observe was a great many rats, ratting about—but they did not known which way to turn. So they were all burnt dead. The flames grew very fast; and I am interested very much with the seats, how they burned, quite different from one another. Some seats made what you call a great splutter, and popped and bounced, and some other seats[Pg 69] made no noise at all. Mr. Bulwer’s place burned of a blue colour; Mr. Buckstone’s turned quite black; and there was one made a flame the colour of a drab. I observe one green flame and one orange, side by side, and they hiss and roar at one another very furious. The gallery cleared itself quite quickly, and the seat of Messieurs the reporters, exploded itself like a cannon of forty-eight pounds. The speaking chair burnt without any sound at all.

When everything is quite done in the Commons I leave them off, and go to the House of Lords, where the fire was all in one sheet, and almost the whole of its inside burnt out. I was able in this room to take off my great coat. I could find nothing to be saved except one great ink-stand, that was red hot, and which I carry away in my two hands. Likewise here, as well as in the Commons, I bottled up several bottles of smoke, to distribute afterwards, at five guineas a-piece, and may be more; for I know the English people admire such things, and are fond after reliques, like a madness almost. I did not make a long stop, for whenever I was visible, the pompiers was so foolish as play water upon me, and I was afraid of a catch-cold. In fact, when I arrive at home, I find myself stuffed in my head, and fast in my chest, and my throat was a little horse. I am going for it into a bath of boiling water, and cannot write any more at full length.

A Letter to a Labouring Man.

BUSHELL,

When you made a holiday last Whitsuntide to see the Sights of London, in your way to the Waxwork and Westminster Abbey, you probably noticed a vast pile of buildings in Palace Yard, and you stood and scratched that shock head of yours, and wondered whose fine houses they were. Seeing you to be a country clodpole, no doubt some well-dressed vagabond, by way of putting a hoax upon the hawbuck, told you that in those[Pg 70] buildings congregated all the talent, all the integrity and public spirit of the country—that beneath those roofs the best and wisest, and the most honest men to be found in three kingdoms, met to deliberate and enact the most wholesome, and just, and judicious laws for the good of the nation. He called them the oracles of our constitution, the guardians of our rights, and the assertors of our liberties. Of course, Bushell, you were told all this; but nobody told you, I dare say, that within those walls your master had lifted up his voice, and delivered the only sound, rational, and wholesome, upright, and able speeches that were ever uttered in St. Stephen’s Chapel. No, nobody told you that. But when I come home, Bushell, I will lend you all my printed speeches, and when you have spelt them, and read them, and studied them, and got them by heart, bumpkin as you are,[Pg 71] Bushell, you will know as much of legislation as all our precious members together.

Well, Bushell, the fine houses you stood gaping at are burnt down, gutted, as the vulgar call it, and nothing is left but the bare walls. You saw Farmer Gubbins’ house, or, at least, the shell of it, after the fire there: well, the Parliament Houses are exactly in the same state. There is news for you! and now, Bushell, how do you feel? Why, if the well-dressed vagabond told you the truth, you feel as if you had had a stroke—for all the British Constitution is affected, and you are a fraction of it, that is to say, a British subject. Your bacon grows rusty in your mouth, and your table-beer turns to vinegar on your palate. You cannot sleep at night, or work by day. You have no heart for anything. You can hardly drag one clouted shoe after another. And how do you look? Why, as pale as a parsnip, and as thin as a hurdle, and your carroty locks stand bolt upright as if you had just met old Lawson’s ghost with his head under his arm. I say thus you must feel and look, Bushell, if what the well-dressed vagabond told you is the truth. But is that the case? No. You drink your small-beer with a sigh and smack of delight; and you bolt your bacon with a relish, as if, as the virtuous Americans say, you could “go the whole hog.” Your clouted shoes clatter about as if you were counting hobnails with the Lord Mayor, and you work like a young horse, or an old ass, and at night you snore like an oratorio of jews’ harps. Your face is as bold and ruddy as the Red Lion’s. Your carroty locks lie sleek upon your poll, and as for poor old Lawson’s ghost, you could lend him flesh and blood enough to set him up again in life. But what, say you, does all this tend to? I will tell you, Bushell. There are a great many well-dressed vagabonds, besides the one you met in Palace Yard, who would persuade a poor man that a House of Lords or Commons is as good to him as his bread, beer, beef, bacon, bed, and breeches; and therefore I[Pg 72] address this to you, Bushell, to set such notions to rights by an appeal to your own back and belly. And now I will tell you what you shall do. You shall go three nights a week to the Red Lion (when your work is done), and you may score up a pint of beer, at my cost, each time. And when the parson, or the exciseman, or the tax-gatherer, or any such gentry, begin to talk of that deplorable great burning, and the national calamity, and such-like trash, you shall pull out my letter and read to them—I say, Bushell, you shall read this letter to them, twice over, loudly and distinctly, and tell them from me, that the burning of twenty Parliament Houses wouldn’t be such a national calamity as a fire at No. 1, Bolt Court.

To Mary Price, Fenny Hall, Lincolnshire.

O Mary,—I am writing in such a quiver, with my art in my mouth, and my tung sticking to it. For too hole hours Ive bean Doin nothink but taking on and going off, I mean into fits, or crying and blessing goodness for my miraclus escape. This day week I wear inwallopped in flams, and thinkin of roth to cum, and fire evverlasting. But thenks to Diving Providings, hear I am, althowgh with loss of wan high brew scotched off, a noo cap and my rite shew. But I hav bean terrifid to deth. Wen I was ate, or it mite be nine, I fell on the stow, and hav had a grate dred of fire evver since. Gudge then how low I felt at the idear of burning along with the Lords and Communer’s. It as bean a Warnin, and never, no, never never never agin will I go to Clandestiny parties behind Mississis backs. I now see my errer, but temtashun prevaled, tho the clovin fut of the Wicked Wan had a hand in it all: Oh Mary, down on yure marrybones, and bless yure stars for sitiating you in a loanly stooped poky place, wear you cant be lead into liteness and gayty, if you was evver so inclind. Fore wipping willies and a[Pg 73] windmill is a dullish luck out, shure enuff, but its better then moor ambishus prospex, and stairing at a grate fire, like a suckin pig, till yure eyes is reddy to drop out of yure hed!