The Project Gutenberg EBook of Companionable Books, by Henry van Dyke This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Companionable Books Author: Henry van Dyke Release Date: February 8, 2020 [EBook #61345] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COMPANIONABLE BOOKS *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

BY HENRY VAN DYKE

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

JOHN KEATS.

Painted by Joseph Severn.

From a photograph, copyright by Hollyer, London.

COMPANIONABLE

BOOKS

BY

HENRY VAN DYKE

“What is this reading, which I must learn,” asked Adam, “and what is it like?”

“It is something beyond gardening,” answered Raphael, “and at times you will find it a heavy task. But at its best it will be like listening through your eyes; and you shall hear the flowers laugh, the trees talk, and the stars sing.”

Solomon Singlewitz—The Life of Adam

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1922

Copyright, 1922, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Copyright, 1920, by HARPER BROTHERS

Printed in the United States of America

Published October, 1922

To

MAXWELL STRUTHERS BURT

AUTHOR AND RANCHMAN

ONCE MY SCHOLAR

ALWAYS MY FRIEND

Many books are dry and dusty, there is no juice in them; and many are soon exhausted, you would no more go back to them than to a squeezed orange; but some have in them an unfailing sap, both from the tree of knowledge and from the tree of life.

By companionable books I mean those that are worth taking with you on a journey, where the weight of luggage counts, or keeping beside your bed, near the night-lamp; books that will bear reading often, and the more slowly you read them the better you enjoy them; books that not only tell you how things look and how people behave, but also interpret nature and life to you, in language of beauty and power touched with the personality of the author, so that they have a real voice audible to your spirit in the silence.

Here I have written about a few of these books which have borne me good company, in one way or another,—and about their authors, who have[viii] put the best of themselves into their work. Such criticism as the volume contains is therefore mainly in the form of appreciation with reasons for it. The other kind of criticism you will find chiefly in the omissions.

So (changing the figure to suit this cabin by the sea) I send forth my new ship, hoping only that it may carry something desirable from each of the ports where it has taken on cargo, and that it may not be sunk by the enemy before it touches at a few friendly harbours.

Henry van Dyke.

Sylvanora, Seal Harbour, Me., August 19, 1922.

| I. | The Book of Books | 1 |

| II. | Poetry in the Psalms | 33 |

| III. | The Good Enchantment of Dickens | 63 |

| IV. | Thackeray and Real Men | 103 |

| V. | George Eliot and Real Women | 131 |

| VI. | The Poet of Immortal Youth (Keats) | 165 |

| VII. | The Recovery of Joy (Wordsworth) | 189 |

| VIII. | “The Glory of the Imperfect” (Browning) | 233 |

| IX. | A Quaint Comrade by Quiet Streams (Walton) | 289 |

| X. | A Sturdy Believer (Samuel Johnson) | 307 |

| XI. | A Puritan Plus Poetry (Emerson) | 333 |

| XII. | An Adventurer in a Velvet Jacket (Stevenson) | 357 |

| John Keats | Frontispiece |

| Facing page |

|

| Charles Dickens as Captain Bobadil in “Every Man in His Humour” | 82 |

| William Makepeace Thackeray | 120 |

| William Wordsworth | 200 |

| Robert Browning | 246 |

| Samuel Johnson | 314 |

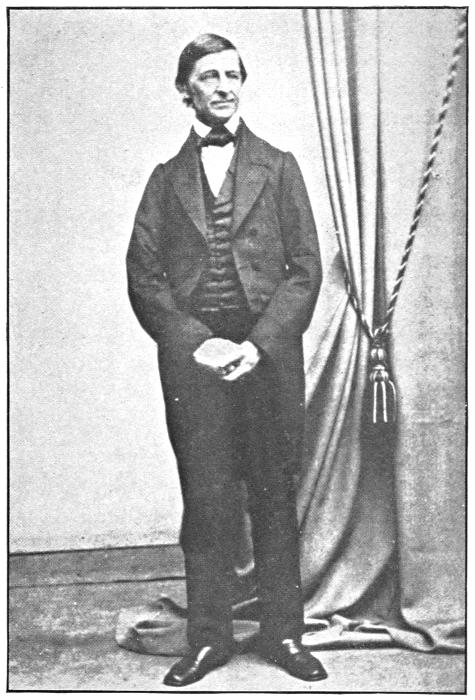

| Ralph Waldo Emerson | 340 |

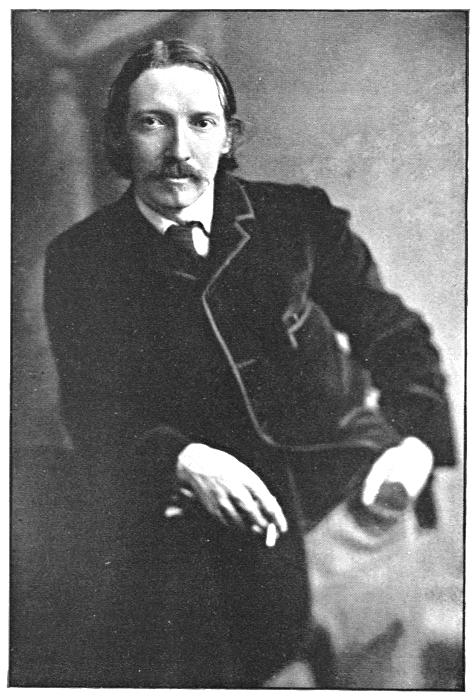

| Robert Louis Stevenson | 360 |

In the cover design by Margaret Armstrong the books and authors are represented by the following symbolic flowers: Bible—grapes; Psalms—wheat; Dickens—English holly; Thackeray—English rose; George Eliot—ivy; Keats—bleeding-heart; Wordsworth—daffodil; Browning—pomegranate; Izaak Walton—strawberry; Johnson—oak; Stevenson—Scottish bluebell.

There was once an Eastern prince who was much enamoured of the art of gardening. He wished that all flowers delightful to the eye, and all fruits pleasant to the taste and good for food, should grow in his dominion, and that in growing the flowers should become more fair, the fruits more savoury and nourishing. With this thought in his mind and this desire in his heart, he found his way to the Ancient One, the Worker of Wonders who dwells in a secret place, and made known his request.

“For the care of your gardens and your orchards,” said the Ancient One, “I can do nothing, since that charge has been given to you and to your people. Nor will I send blossoming plants and fruiting trees of every kind to make your kingdom rich and beautiful as by magic, lest the honour of labour should be diminished, and the slow reward of patience despised, and even the living gifts bestowed upon you[4] without toil should wither and die away. But this will I do: a single tree shall be brought to you from a far country by the hands of my servants, and you shall plant it in the midst of your land. In the body of that tree is the sap of life that was from the beginning; the leaves of it are full of healing; its flowers never fail, and its fruitage is the joy of every season. The roots of the tree shall go down to the springs of deep waters; and wherever its pollen is drifted by the wind or borne by the bees, the gardens shall put on new beauty; and wherever its seed is carried by the fowls of the air, the orchards shall yield a richer harvest. But the tree itself you shall guard and cherish and keep as I give it you, neither cutting anything away from it, nor grafting anything upon it; for the life of the tree is in all the branches, and the other trees shall be glad because of it.”

As the Ancient One had spoken, so it came to pass. The land of that prince had great renown of fine flowers and delicious fruits, ever unfolding in new colours and sweeter flavours the life that was shed among them by the tree of trees.

Something like the marvel of this tale may be read in the history of the Bible. No other book in the world has had such a strange vitality, such an outgoing power of influence and inspiration. Not only has it brought to the countries in whose heart it has been set new ideals of civilization, new models of character, new conceptions of virtue and hopes of happiness; but it has also given new impulse and form to the shaping imagination of man, and begotten beauty in literature and the other arts.

Suppose, for example, that it were possible to dissolve away all the works of art which clearly owe their being to thoughts, emotions, or visions derived from the Bible,—all sculpture like Donatello’s “David” and Michelangelo’s “Moses”; all painting like Raphael’s “Sistine Madonna” and Murillo’s “Holy Family”; all music like Bach’s “Passion” and Handel’s “Messiah”; all poetry like Dante’s “Divine Comedy” and Milton’s “Paradise Lost,”—how it would impoverish the world!

The literary influence of the Bible appears the[6] more wonderful when we consider that it is the work of a race not otherwise potent or famous in literature. We do not know, of course, what other books may have come from the Jewish nation and vanished with whatever of power or beauty they possessed; but in those that remain there is little of exceptional force or charm for readers outside of the Hebrew race. They have no broad human appeal, no universal significance, not even any signal excellence of form and imagery. Josephus is a fairly good historian, sometimes entertaining, but not comparable to Herodotus or Thucydides or Tacitus or Gibbon. The Talmuds are vast storehouses of things new and old, where a careful searcher may now and then find a legendary gem or a quaint fragment of moral tapestry. In histories of mediæval literature, Ibn Ezra of Toledo and Rashi of Lunel are spoken of with respect. In modern letters, works as far apart as the philosophical treatises of Spinoza and the lyrics of Heinrich Heine have distinction in their kind. No one thinks that the Hebrews are lacking in great and varied talents; but how is it that in world-literature their only contribution[7] that counts is the Bible? And how is it that it counts so immensely?

It is possible to answer by saying that in the Old Testament we have a happily made collection of the best things in the ancient literature of the Jews, and in the New Testament we have another anthology of the finest of the narratives and letters which were produced by certain writers of the same race under a new and exceedingly powerful spiritual impulse. The Bible is excellent because it contains the cream of Hebrew thought. But this answer explains nothing. It only restates the facts in another form. How did the cream rise? How did such a collection come to be made? What gives it unity and coherence underneath all its diversity? How is it that, as a clear critic has well said, “These sixty books, with all their varieties of age, authorship, literary form, are, when properly arranged, felt to draw together with a unity like the connectedness of a dramatic plot?”

There is an answer, which if it be accepted, carries with it a solution of the problem.

Suppose a race chosen by some process of selection[8] (which need not now be discussed or defined) to develop in its strongest and most absolute form that one of man’s faculties which is called the religious sense, to receive most clearly and deeply the impression of the unity, spirituality, and righteousness of a Supreme Being present in the world. Imagine that race moving through a long and varied experience under this powerful impression, now loyal to it, now rebelling against it, now misinterpreting it, now led by the voice of some prophet to understand it more fully and feel it more profoundly, but never wholly losing it for a single generation. Imagine the history of that race, its poetry, the biography of its famous men and women, the messages of its moral reformers, conceived and written in constant relation to that strongest factor of conscious life, the sense of the presence and power of the Eternal.

Suppose, now, in a time of darkness and humiliation, that there rises within that race a prophet who declares that a new era of spiritual light has come, preaches a new revelation of the Eternal, and claims in his own person to fulfil the ancient hopes and[9] promises of a divine deliverer and redeemer. Imagine his followers, few in number, accepting his message slowly and dimly at first, guided by companionship with him into a clearer understanding and a stronger belief, until at last they are convinced that his claims are true, and that he is the saviour not only of the chosen people, but also of the whole world, the revealer of the Eternal to mankind. Imagine these disciples setting out with incredible courage to carry this message to all nations, so deeply impressed with its truth that they are supremely happy to suffer and die for it, so filled with the passion of its meaning that they dare attempt to remodel the life of the world with it. Suppose a human story like this underneath the writing of the books which are gathered in the Bible, and you have an explanation—it seems to me the only reasonable explanation—of their surpassing quality and their strange unity.

This story is not a mere supposition: its general outline, stated in these terms, belongs to the realm of facts which cannot reasonably be questioned. What more is needed to account for the story itself,[10] what potent and irresistible reality is involved in this record of experience, I do not now ask. This is not an estimate of the religious authority of the Bible, nor of its inspiration in the theological sense of that word, but only of something less important, though no less real—its literary influence.

The fountain-head of the power of the Bible in literature lies in its nearness to the very springs and sources of human life—life taken seriously, earnestly, intensely; life in its broadest meaning, including the inward as well as the outward; life interpreted in its relation to universal laws and eternal values. It is this vital quality in the narratives, the poems, the allegories, the meditations, the discourses, the letters, gathered in this book, that gives it first place among the books of the world not only for currency, but also for greatness.

For the currency of literature depends in the long run upon the breadth and vividness of its human appeal. And the greatness of literature depends upon the intensive significance of those portions of[11] life which it depicts and interprets. Now, there is no other book which reflects so many sides and aspects of human experience as the Bible, and this fact alone would suffice to give it a world-wide interest and make it popular. But it mirrors them all, whether they belong to the chronicles of kings and conquerors, or to the obscure records of the lowliest of labourers and sufferers, in the light of a conviction that they are all related to the will and purpose of the Eternal. This illuminates every figure with a divine distinction, and raises every event to the nth power of meaning. It is this fact that gives the Bible its extraordinary force as literature and makes it great.

Born in the East and clothed in Oriental form and imagery, the Bible walks the ways of all the world with familiar feet and enters land after land to find its own everywhere. It has learned to speak in hundreds of languages to the heart of man. It comes into the palace to tell the monarch that he is a servant of the Most High, and into the cottage to assure the peasant that he is a son of God. Children listen to its stories with wonder and delight, and wise men ponder them as[12] parables of life. It has a word of peace for the time of peril, a word of comfort for the day of calamity, a word of light for the hour of darkness. Its oracles are repeated in the assembly of the people, and its counsels whispered in the ear of the lonely. The wicked and the proud tremble at its warning, but to the wounded and the penitent it has a mother’s voice. The wilderness and the solitary place have been made glad by it, and the fire on the hearth has lit the reading of its well-worn page. It has woven itself into our deepest affections and coloured our dearest dreams; so that love and friendship, sympathy and devotion, memory and hope, put on the beautiful garments of its treasured speech, breathing of frankincense and myrrh.

Above the cradle and beside the grave its great words come to us uncalled. They fill our prayers with power larger than we know, and the beauty of them lingers on our ear long after the sermons which they adorned have been forgotten. They return to us swiftly and quietly, like doves flying from far away. They surprise us with new meanings, like springs of water breaking forth from the mountain beside a long-trodden path. They grow richer, as pearls do when they are worn near the heart.

No man is poor or desolate who has this treasure for his own. When the landscape darkens and the trembling pilgrim comes to the Valley named of the Shadow, he is not afraid to enter: he takes the rod and staff of Scripture in his hand; he says to friend and comrade, “Good-by; we shall meet again”; and comforted by that support, he goes toward the lonely pass as one who walks through darkness into light.

It would be strange indeed if a book which has played such a part in human life had not exercised an extraordinary influence upon literature. As a matter of fact, the Bible has called into existence tens of thousands of other books devoted to the exposition of its meaning, the defense and illustration of its doctrine, the application of its teaching, or the record of its history. The learned Fabricius, in the early part of the eighteenth century, published a catalogue raisonné of such books, filling seven hundred quarto pages.[1] Since that time the length of the list has probably more than trebled. In addition, we must reckon the many books of hostile criticism and contrary argument which the Bible has evoked, and which are an evidence of[14] revolt against the might of its influence. All this tangle of Biblical literature has grown up around it like a vast wood full of all manner of trees, great and small, useful and worthless, fruit-trees, timber-trees, berry-bushes, briers, and poison-vines. But all of them, even the most beautiful and tall, look like undergrowth, when we compare them with the mighty oak of Scripture, towering in perennial grandeur, the father of the forest.

Among the patristic writers there were some of great genius like Origen and Chrysostom and Augustine. The mediæval schools of theology produced men of philosophic power, like Anselm and Thomas Aquinas; of spiritual insight, like the author of the Imitatio Christi. The eloquence of France reached its height in the discourses of Bossuet, Bourdaloue, and Massillon. German became one of the potent tongues of literature when Martin Luther used it in his tracts and sermons, and Herder’s Geist der hebräischen Poesie is one of the great books in criticism. In English, to mention such names as Hooker and Fuller and Jeremy Taylor is to recall the dignity, force, and splendour of prose at its best.[15] Yet none of these authors has produced anything to rival the book from which they drew their common inspiration.

In the other camp, though there have been many brilliant assailants, not one has surpassed, or even equalled, in the estimation of the world, the literary excellence of the book which they attacked. The mordant wit of Voltaire, the lucid and melancholy charm of Renan, have not availed to drive or draw the world away from the Bible; and the effect of all assaults has been to leave it more widely read, better understood, and more intelligently admired than ever before.

Now it must be admitted that the same thing is true, at least in some degree, of other books which are held to be sacred or quasi-sacred: they are superior to the distinctively theological literature which has grown up about them. I suppose nothing of the Mussulmans is as great as the “Koran,” nothing of the Hindus as great as the “Vedas”; and though the effect of the Confucian classics, from the literary point of view, may not have been altogether good, their supremacy in the religious library[16] of the Chinese is unquestioned. But the singular and noteworthy thing about the influence of the Bible is the extent to which it has permeated general literature, the mark which it has made in all forms of belles-lettres. To treat this subject adequately one would need to write volumes. In this chapter I can touch but briefly on a few points of the outline as they come out in English literature.

In the Old-English period, the predominant influence of the Scriptures may be seen in the frequency with which the men of letters turned to them for subjects, and in the Biblical colouring and texture of thought and style. Cædmon’s famous “Hymn” and the other poems like “Genesis,” “Exodus,” “Daniel,” and “Judith,” which were once ascribed to him; Cynewulf’s “Crist,” “The Fates of the Apostles,” “The Dream of the Rood”; Ælfric’s “Homilies” and his paraphrases of certain books of Scripture—these early fruits of our literature are all the offspring of the Bible.

In the Middle-English period, that anonymous[17] masterpiece “Pearl” is full of the spirit of Christian mysticism, and the two poems called “Cleanness” and “Patience,” probably written by the same hand, are free and spirited versions of stories from the Bible. “The Vision of Piers the Plowman,” formerly ascribed to William Langland, but now supposed by some scholars to be the work of four or five different authors, was the most popular poem of the latter half of the fourteenth century. It is a vivid picture of the wrongs and sufferings of the labouring man, a passionate satire on the corruptions of the age in church and state, an eloquent appeal for a return to truth and simplicity. The feeling and the imagery of Scripture pervade it with a strange power and charm; in its reverence for poverty and toil it leans closely and confidently upon the example of Jesus; and at the end it makes its ploughman hero appear in some mystic way as a type, first of the crucified Saviour, and then of the church which is the body of Christ.

It was about this time, the end of the fourteenth century, that John Wyclif and his disciples, feeling the need of the support of the Bible in their work[18] as reformers, took up and completed the task of translating it entirely into the English tongue of the common people. This rude but vigourous version was revised and improved by John Purvey. It rested mainly upon the Latin version of St. Jerome. At the beginning of the sixteenth century William Tindale made an independent translation of the New Testament from the original Greek, a virile and enduring piece of work, marked by strength and simplicity, and setting a standard for subsequent English translations. Coverdale’s version of the Scriptures was published in 1535, and was announced as made “out of Douche and Latyn”; that is to say, it was based upon the German of Luther and the Zurich Bible, and upon the Vulgate of St. Jerome; but it owed much to Tindale, to whose manly force it added a certain music of diction and grace of phrase which may still be noted in the Psalms as they are rendered in the Anglican Prayer-Book. Another translation, marked by accurate scholarship, was made by English Puritans at Geneva, and still another, characterized by a richer Latinized style, was made by English Catholics[19] living in exile at Rheims, and was known as “the Douai Version,” from the fact that it was first published in its complete form in that city in 1609-1610.

Meantime, in 1604, a company of scholars had been appointed by King James I in England to make a new translation “out of the original tongues, and with the former translations diligently compared and revised.” These forty-seven men had the advantage of all the work of their predecessors, the benefit of all the discussion over doubtful words and phrases, and the “unearned increment” of riches which had come into the English language since the days of Wyclif. The result of their labours, published in 1611, was the so-called “Authorized Version,” a monument of English prose in its prime: clear, strong, direct, yet full of subtle rhythms and strange colours; now moving as simply as a shepherd’s song, in the Twenty-third Psalm; now marching with majestic harmonies, in the book of Job; now reflecting the lowliest forms of human life, in the Gospel stories; and now flashing with celestial splendours in the visions of the Apocalypse;[20] vivid without effort; picturesque without exaggeration; sinewy without strain; capable alike of the deepest tenderness and the most sublime majesty; using a vocabulary of only six thousand words to build a book which, as Macaulay said, “if everything else in our language should perish, would alone suffice to show the whole extent of its beauty and power.”

The literary excellence of this version, no doubt, did much to increase the influence of the Bible in literature and confirm its place as the central book in the life of those who speak and write the English tongue. Consider a few of the ways in which this influence may be traced.

First of all, it has had a general effect upon English writing, helping to preserve it from the opposite faults of vulgarity and affectation. Coleridge long ago remarked upon the tendency of a close study of the Bible to elevate a writer’s style. There is a certain naturalness, inevitableness, propriety of form to substance, in the language of Scripture[21] which communicates to its readers a feeling for the fitness of words; and this in itself is the first requisite of good writing. Sincerity is the best part of dignity.

The English of our Bible is singularly free from the vice of preciosity: it is not far-sought, overnice, elaborate. Its plainness is a rebuking contrast to all forms of euphuism. It does not encourage a direct imitation of itself; for the comparison between the original and the copy makes the latter look pale and dull. Even in the age which produced the authorized version, its style was distinct and remarkable. As Hallam has observed, it was “not the English of Daniel, of Raleigh, or Bacon.” It was something larger, at once more ancient and more modern, and therefore well fitted to become not an invariable model, but an enduring standard. Its words come to it from all sources; they are not chosen according to the foolish theory that a word of Anglo-Saxon origin is always stronger and simpler than a Latin derivative. Take the beginning of the Forty-sixth Psalm:

“God is our refuge and strength, a very present[22] help in trouble. Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea; though the waters thereof roar and be troubled, though the mountains shake with the swelling thereof.”

Or take this passage from the Epistle to the Romans:

“Be kindly affectioned one to another with brotherly love; in honour preferring one another; not slothful in business; fervent in spirit; serving the Lord; rejoicing in hope; patient in tribulation; continuing instant in prayer; distributing to the necessity of saints; given to hospitality.”

Here is a style that adapts itself by instinct to its subject, and whether it uses Saxon words like “strength” and “help” and “love” and “hope,” or Latin words like “refuge” and “trouble” and “present” and “fervent” and “patient” and “prayer” and “hospitality,” weaves them into a garment worthy of the thought.

The literary influence of a great, popular book written in such a style is both inspiring and conservative. It survives the passing modes of prose[23] in each generation, and keeps the present in touch with the past. It preserves a sense of balance and proportion in a language whose perils lie in its liberties and in the indiscriminate use of its growing wealth. And finally it keeps a medium of communication open between the learned and the simple; for the two places where the effect of the Bible upon the English language may be most clearly felt are in the natural speech of the plain people and in the finest passages of great authors.

Following this line of the influence of the Bible upon language as the medium of literature, we find, in the next place, that it has contributed to our common speech a great number of phrases which are current everywhere. Sometimes these phrases are used in a merely conventional way. They serve as counters in a long extemporaneous prayer, or as padding to a page of dull and pious prose. But at other times they illuminate the sentence with a new radiance; they clarify its meaning with a true symbol; they enhance its value with rich associations;[24] they are “sweeter than honey and the honeycomb.”

Take for example such phrases as these: “a good old age,” “the wife of thy bosom,” “the apple of his eye,” “gathered to his fathers,” “a mother in Israel,” “a land flowing with milk and honey,” “the windows of heaven,” “the fountains of the great deep,” “living fountains of waters,” “the valley of decision,” “cometh up as a flower,” “a garden enclosed,” “one little ewe lamb,” “thou art the man,” “a still, small voice,” “as the sparks fly upward,” “swifter than a weaver’s shuttle,” “miserable comforters,” “the strife of tongues,” “the tents of Kedar,” “the cry of the humble,” “the lofty looks of man,” “the pride of life,” “from strength to strength,” “as a dream when one awaketh,” “the wings of the morning,” “stolen waters,” “a dinner of herbs,” “apples of gold in pictures of silver,” “better than rubies,” “a lion in the way,” “vanity of vanities,” “no discharge in that war,” “the little foxes that spoil the vines,” “terrible as an army with banners,” “precept upon precept, line upon line,” “as a drop of a bucket,” “whose merchants[25] are princes,” “trodden the wine-press alone,” “the rose of Sharon and the lily of the valley,” “the highways and hedges,” “the salt of the earth,” “the burden and heat of the day,” “the signs of the times,” “a pearl of great price,” “what God hath joined together,” “the children of light,” “the powers that be,” “if the trumpet give an uncertain sound,” “the fashion of this world,” “decently and in order,” “a thorn in the flesh,” “labour of love,” “a cloud of witnesses,” “to entertain angels unawares,” “faithful unto death,” “a crown of life.” Consider also those expressions which carry with them distinctly the memory of some ancient story: “the fleshpots of Egypt,” “manna in the wilderness,” “a mess of pottage,” “Joseph’s coat,” “the driving of Jehu,” “the mantle of Elijah,” “the widow’s mite,” “the elder brother,” “the kiss of Judas,” “the house of Martha,” “a friend of publicans and sinners,” “many mansions,” “bearing the cross.” Into such phrases as these, which are familiar to us all, the Bible has poured a wealth of meaning far beyond the measure of the bare words. They call up visions and reveal mysteries.

Direct, but not always accurate, quotations from Scripture and allusions to Biblical characters and events are very numerous in English literature. They are found in all sorts of books. Professor Albert T. Cook has recently counted sixty-three in a volume of descriptive sketches of Italy, twelve in a book on wild animals, and eighteen in a novel by Thomas Hardy. A special study of the Biblical references in Tennyson has been made,[2] and more than five hundred of them have been found.

Bishop Charles Wordsworth has written a book on Shakespeare’s Knowledge and Use of the Bible,[3] and shown “how fully and how accurately the general tenor of the facts recorded in the sacred narrative was present to his mind,” and “how Scriptural are the conceptions which Shakespeare had of the being and attributes of God, of His general and particular Providence, of His revelation to man, of[27] our duty toward Him and toward each other, of human life and of human death, of time and of eternity.” It is possible that the bishop benevolently credits the dramatist with a more invariable and complete orthodoxy than he possessed. But certainly Shakespeare knew the Bible well, and felt the dramatic value of allusions and illustrations which were sure to be instantly understood by the plain people. It is his Antonio, in The Merchant of Venice, who remarks that “the Devil can cite Scripture for his purpose,” evidently referring to the Gospel story of the evil one who tried to tempt Jesus with a verse from the Psalms.

The references to the Bible in the poetry of Robert Browning have been very carefully examined by Mrs. Machen in an admirable little book.[4] It is not too much to say that his work is crowded with Scriptural quotations, allusions, and imagery. He follows Antonio’s maxim, and makes his bad characters, like Bishop Blougram and Sludge the Medium, cite from Holy Writ to cloak their hypocrisy or excuse their villainy. In his longest[28] poem, The Ring and the Book, there are said to be more than five hundred Biblical references.

But more remarkable even than the extent to which this material drawn from the Scriptures has been used by English writers, is the striking effect which it produces when it is well used. With what pathos does Sir Walter Scott, in The Heart of Midlothian, make old Davie Deans bow his head when he sees his daughter Effie on trial for her life, and mutter to himself, “Ichabod! my glory is departed!” How magnificently does Ruskin enrich his Sesame and Lilies with that passage from Isaiah in which the fallen kings of Hades start from their thrones to greet the newly fallen with the cry, “Art thou also become weak as we? Art thou become like unto us?” How grandly do the images and thoughts of the last chapters of Deuteronomy roll through Kipling’s Recessional, with its Scriptural refrain, “Lest we forget!”

There are some works of literature in English since the sixteenth century which are altogether Biblical in subject and colouring. Chief among these in prose is The Pilgrim’s Progress of John Bunyan, and[29] in verse, the Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, and Samson Agonistes of John Milton. These are already classics. Some day a place near them will be given to Browning’s Saul and A Death in the Desert; but for that we must wait until their form has stood the test of time.

In general it may be observed—and the remark holds good of the works just mentioned—that a Scriptural story or poem is most likely to succeed when it takes its theme, directly or by suggestion, from the Bible, and carries it into a region of imagination, a border-realm, where the author is free to work without paraphrase or comparison with the sacred writers. It is for this reason that both Samson Agonistes and Paradise Lost are superior to Paradise Regained.

The largest and most important influence of the Bible in literature lies beyond all these visible effects upon language and style and imagery and form. It comes from the strange power of the book to nourish and inspire, to mould and guide, the inner life of[30] man. “It finds me,” said Coleridge; and the word of the philosopher is one that the plain man can understand and repeat.

The hunger for happiness which lies in every human heart can never be satisfied without righteousness; and the reason why the Bible reaches down so deep into the breast of man is because it brings news of a kingdom which is righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit. It brings this news not in the form of a dogma, a definition, a scientific statement, but in the form of literature, a living picture of experience, a perfect ideal embodied in a Character and a Life. And because it does this, it has inspiration for those who write in the service of truth and humanity.

The Bible has been the favourite book of those who were troubled and downtrodden, and of those who bore the great burden of a great task. New light has broken forth from it to lead the upward struggle of mankind from age to age. Men have come back to it because they could not do without it. Nor will its influence wane, its radiance be darkened, unless literature ceases to express the noblest of[31] human longings, the highest of human hopes, and mankind forgets all that is now incarnate in the central figure of the Bible,—the Divine Deliverer.

There are three ways in which we may read the Bible.

We may come to it as the divinely inspired rule of faith and conduct. This is the point of view from which it appears most precious to religion. It gives us the word of God to teach us what to believe and how to live.

We may consider it as a collection of historical books, written under certain conditions, and reflecting, in their contents and in their language, the circumstances in which they were produced. This is the aspect in which criticism regards the Bible; and its intellectual interest, as well as its religious value, is greatly enhanced by a clear vision of the truth about it from this point of view.

We may study it also as literature. We may see in it a noble and impassioned interpretation of nature and life, uttered in language of beauty and sublimity, touched with the vivid colours of human personality, and embodied in forms of enduring literary art.

None of these three ways of studying the Bible is hostile to the others. On the contrary, they are helpful to one another, because each of them gives us knowledge of a real factor in the marvellous influence of the Bible in the world.

The true lover of the Bible has an interest in all the elements of its life as an immortal book. He wishes to discern, and rightly to appreciate, the method of its history, the spirit of its philosophy, the significance of its fiction, the power of its eloquence, and the charm of its poetry. He wishes this all the more because he finds in it something which is not in any other book: a vision of God, a hope for man, and an inspiration to righteousness which seem to him divine. As the worshipper in the Temple would observe the art and structure of the carven beams of cedar and the lily-work on the tops of the pillars the more attentively because they beautified the house of his God, so the man who has a religious faith in the Bible will study more eagerly and carefully the literary forms of the book in which the Holy Spirit speaks forever.

It is in this spirit that I wish to consider the poetical[37] element in the Psalms. The comfort, help, and guidance that they bring to our spiritual life will not be diminished, but increased, by a perception of their exquisite form and finish. If a king sent a golden cup full of cheering cordial to a weary man, he might well admire the two-fold bounty of the royal gift. The beauty of the vessel would make the draught more grateful and refreshing. And if the cup were inexhaustible, if it filled itself anew as often as it touched the lips, then the very shape and adornment of it would become significant and precious. It would be an inestimable possession, a singing goblet, a treasure of life.

John Milton, whose faith in religion was as exalted as his mastery of the art of poetry was perfect, has expressed in a single sentence the spirit in which I would approach the poetic study of the Book of Psalms: “Not in their divine arguments alone, but in the very critical art of composition, the Psalms may be easily made to appear over all kinds of lyric poetry incomparable.”

Let us remember at the outset that a considerable part of the value of the Psalms as poetry will lie beyond our reach. We cannot precisely measure it, nor give it full appreciation, simply because we are dealing with the Psalms only as we have them in our English Bible. This is a real drawback; and it is well to understand clearly the two things that we lose in reading the Psalms in this way.

First, we lose the beauty and the charm of verse. This is a serious loss. Poetry and verse are not the same thing, but they are so intimately related that it is difficult to divide them. Indeed, according to certain definitions of poetry, it would seem almost impossible.

Yet who will deny that the Psalms as we have them in the English Bible are really and truly poetical?

The only way out of this difficulty that I can see is to distinguish between verse as the formal element and imaginative emotion as the essential element in poetry. In the original production of a[39] poem, it seems to me, it is just to say that the embodiment in metrical language is a law of art which must be observed. But in the translation of a poem (which is a kind of reflection of it in a mirror) the verse may be lost without altogether losing the spirit of the poem.

Take an illustration from another art. A statue has the symmetry of solid form. You can look at it from all sides, and from every side you can see the balance and rhythm of the parts. In a photograph this solidity of form disappears. You see only a flat surface. But you still recognize it as the reflection of a statue.

The Psalms were undoubtedly written, in the original Hebrew, according to a system of versification, and perhaps to some extent with forms of rhyme.

The older scholars, like Lowth and Herder, held that such a system existed, but could not be recovered. Later scholars, like Ewald, evolved a system of their own. Modern scholarship, represented by such authors as Professors Cheyne and Briggs, is reconstructing and explaining more accurately the[40] Hebrew versification. But, for the present at least, the only thing that is clear is that this system must remain obscure to us. It cannot be reproduced in English. The metrical versions of the Psalms are the least satisfactory. The poet Cowley said of them, “They are so far from doing justice to David that methinks they revile him worse than Shimei.”[5] We must learn to appreciate the poetry in the Psalms without the aid of those symmetries of form and sound in which they first appeared. This is a serious loss. Poetry without verse is like a bride without a bridal garment.

The second thing that we lose in reading the Psalms in English is something even more important. It is the heavy tax on the wealth of its meaning, which all poetry must pay when it is imported from one country to another, through the medium of translation.

The most subtle charm of poetry is its suggestiveness; and much of this comes from the magical power which words acquire over memory and imagination, from their associations. This intimate and[41] personal charm must be left behind when a poem passes from one language to another. The accompaniment, the harmony of things remembered and beloved, which the very words of the song once awakened, is silent now. Nothing remains but the naked melody of thought. If this is pure and strong, it will gather new associations; as, indeed, the Psalms have already done in English, so that their familiar expressions have become charged with musical potency. And yet I suppose such phrases as “a tree planted by the rivers of water,” “a fruitful vine in the innermost parts of the house,” “the mountains round about Jerusalem,” can never bring to us the full sense of beauty, the enlargement of heart, that they gave to the ancient Hebrews. But, in spite of this double loss, in the passage from verse to prose and from Hebrew to English, the poetry in the Psalms is so real and vital and imperishable that every reader feels its beauty and power.

It retains one valuable element of poetic form. This is that balancing of the parts of a sentence, one against another, to which Bishop Lowth first gave the familiar name of “parallelism.”[6] The effect of[42] this simple artifice, learned from Nature herself, is singularly pleasant and powerful. It is the rise and fall of the fountain, the ebb and flow of the tide, the tone and overtone of the chiming bell. The two-fold utterance seems to bear the thought onward like the wings of a bird. A German writer compares it very exquisitely to “the heaving and sinking of the troubled heart.”

It is this “parallelism” which gives such a familiar charm to the language of the Psalms. Unconsciously, and without recognizing the nature of the attraction, we grow used to the double cadence, the sound and the echo, and learn to look for its recurrence with delight.

If we should want a plain English name for this method of composition we might call it thought-rhyme. It is easy to find varied illustrations of its beauty and of its power to emphasize large and simple ideas.

Take for instance that very perfect psalm with which the book begins—a poem so complete, so compact, so delicately wrought that it seems like a sonnet. The subject is The Two Paths.

The first part describes the way of the good man. It has three divisions.

The first verse gives a description of his conduct by negatives—telling us what he does not do. There is a triple thought-rhyme here.

The second verse describes his character positively, with a double thought-rhyme.

The third verse tells us the result of this character and conduct, in a fourfold thought-rhyme.

The second part of the psalm describes the way of the evil man. In the fourth verse there is a double thought-rhyme.

In the fifth verse the consequences of this worthless, fruitless, unrooted life are shown, again with a double cadence of thought, the first referring to the judgment of God, the second to the judgment of men.

The third part of the psalm is a terse, powerful couplet, giving the reason for the different ending of the two paths.

The thought-rhyme here is one of contrast.

A poem of very different character from this brief, serious, impersonal sonnet is found in the Forty-sixth Psalm, which might be called a National[45] Anthem. Here again the poem is divided into three parts.

The first part (verses first to third) expresses a sense of joyful confidence in the Eternal, amid the tempests and confusions of earth. The thought-rhymes are in couplets; and the second phrase, in each case, emphasizes and enlarges the idea of the first phrase.

The second part (verses fourth to seventh) describes the peace and security of the city of God, surrounded by furious enemies, but rejoicing in the Eternal Presence. The parallel phrases here follow the same rule as in the first part. The concluding phrase is the stronger, the more emphatic. The seventh verse gives the refrain or chorus of the anthem.

The last part (verses eighth to tenth) describes in a very vivid and concrete way the deliverance of the people that have trusted in the Eternal. It begins with a couplet, like those which have gone[46] before. Then follow two stanzas of triple thought-rhymes, in which the thought is stated and intensified with each repetition.

The anthem ends with a repetition of the refrain.

A careful study of the Psalms, even in English, will enable the thoughtful reader to derive new pleasure from them, by tracing the many modes and manners in which this poetic form of thought-rhyme is used to bind the composition together, and to give balance and harmony to the poem.

Another element of poetic form can be discerned in the Psalms, not directly, in the English version, but by its effects. I mean the curious artifice of alphabetic arrangement. It was a favourite practice among Hebrew poets to begin their verses with the successive letters of the alphabet, or sometimes[47] to vary the device by making every verse in a strophe begin with one letter, and every verse in the next strophe with the following letter, and so on to the end. The Twenty-fifth and the Thirty-seventh Psalms were written by the first of these rules; the One Hundred and Nineteenth Psalm follows the second plan.

Of course the alphabetic artifice disappears entirely in the English translation. But its effects remain. The Psalms written in this manner usually have but a single theme, which is repeated over and over again, in different words and with new illustrations. They are kaleidoscopic. The material does not change, but it is turned this way and that way, and shows itself in new shapes and arrangements. These alphabetic psalms are characterized by poverty of action and richness of expression.

Milton has already reminded us that the Psalms belong to the second of the three orders into which the Greeks, with clear discernment, divided all[48] poetry: the epic, the lyric, and the dramatic. The Psalms are rightly called lyrics because they are chiefly concerned with the immediate and imaginative expression of real feeling. It is the personal and emotional note that predominates. They are inward, confessional, intense; outpourings of the quickened spirit; self-revelations of the heart. It is for this reason that we should never separate them in our thought from the actual human life out of which they sprung. We must feel the warm pulse of humanity in them in order to comprehend their meaning and immortal worth. So far as we can connect them with the actual experience of men, this will help us to appreciate their reality and power. The effort to do this will make plain to us some other things which it is important to remember.

We shall see at once that the book does not come from a single writer, but from many authors and ages. It represents the heart of man in communion with God through a thousand years of history, from Moses to Nehemiah, perhaps even to the time of the Maccabean revival. It is, therefore, something[49] very much larger and better than an individual book.

It is the golden treasury of lyrics gathered from the life of the Hebrew people, the hymn-book of the Jews. And this gives to it a singular and precious quality of brotherhood. The fault, or at least the danger, of modern lyrical poetry is that it is too solitary and separate in its tone. It tends towards exclusiveness, over-refinement, morbid sentiment. Many Christian hymns suffer from this defect. But the Psalms breathe a spirit of human fellowship even when they are most intensely personal. The poet rejoices or mourns in solitude, it may be, but he is not alone in spirit. He is one of the people. He is conscious always of the ties that bind him to his brother men. Compare the intense selfishness of the modern hymn:

with the generous penitence of the Fifty-first Psalm:

It is important to observe that there are several different kinds of lyrics among the Psalms. Some of them are simple and natural outpourings of a single feeling, like A Shepherd’s Song about His Shepherd, the incomparable Twenty-third Psalm.

This little poem is a perfect melody. It would be impossible to express a pure, unmixed emotion—the feeling of joy in the Divine Goodness—more simply, with a more penetrating lyrical charm. The “valley of the death-shadow,” the “enemies” in whose presence the table is spread, are but dimly suggested in the background. The atmosphere of the psalm is clear and bright. The singing shepherd walks in light. The whole world is the House of the Lord, and life is altogether gladness.

How different is the tone, the quality, of the One Hundred and Nineteenth Psalm! This is not a melody, but a harmony; not a song, but an ode. The ode has been defined as “a strain of exalted and enthusiastic lyrical verse, directed to a fixed purpose and dealing progressively with one dignified theme.”[7] This definition precisely fits the One Hundred and Nineteenth Psalm.

Its theme is The Eternal Word. Every verse in the poem, except one, contains some name or description of the law, commandments, testimonies, precepts, statutes, or judgments of Jehovah. Its enthusiasm for the Divine Righteousness never fails from beginning to end. Its fixed purpose is to kindle in other hearts the flame of devotion to the one Holy Law. It closes with a touch of magnificent pathos—a confession of personal failure and an assertion of spiritual loyalty:

The Fifteenth Psalm I should call a short didactic lyric. Its title is The Good Citizen. It begins with a question:

This question is answered by the description of a man whose character corresponds to the law of God. First there is a positive sketch in three broad lines:

Then comes a negative characterization in a finely touched triplet:

This is followed by a couplet containing a strong contrast:

Then the description goes back to the negative style again and three more touches are added to the picture:

The poem closes with a single vigourous line, summing up the character of the good citizen and answering the question of the first verse with a new emphasis of security and permanence:

The Seventy-eighth, One Hundred and Fifth, and One Hundred and Sixth Psalms are lyrical[53] ballads. They tell the story of Israel in Egypt, and in the Wilderness, and in Canaan, with swift, stirring phrases, and with splendid flashes of imagery. Take this passage from the Seventy-eighth Psalm as an example:

The Forty-fifth Psalm is a Marriage Ode: the Hebrew title calls it a Love Song. It bears all the marks of having been composed for some royal wedding-feast in Jerusalem.

There are many nature lyrics among the Psalms. The Twenty-ninth is notable for its rugged realism. It is a Song of Thunder.

The One Hundred and Fourth, on the contrary, is full of calm sublimity and meditative grandeur.

The Nineteenth is famous for its splendid comparison between “the starry heavens and the moral law.”

I think that we may find also some dramatic lyrics among the Psalms—poems composed to express the feelings of an historic person, like David or Solomon, in certain well-known and striking experiences of his life. That a later writer should thus embody and express the truth dramatically through the personality of some great hero of the past, involves no falsehood. It is a mode of utterance which has been common to the literature of[56] all lands and of all ages. Such a method of composition would certainly be no hindrance to the spirit of inspiration. The Thirty-first Psalm, for instance, is ascribed by the title to David. But there is strong reason, in the phraseology and in the spirit of the poem, to believe that it was written by the Prophet Jeremiah.

It is not to be supposed that our reverence for the Psalms in their moral and religious aspects will make us put them all on the same level poetically. There is a difference among the books of the New Testament in regard to the purity and dignity of the Greek in which they are written. There is a difference among St. Paul’s Epistles in regard to the clearness and force of their style. There is a difference even among the chapters of the same epistle in regard to the beauty of thought and language. In the First Epistle to the Corinthians, the thirteenth chapter is poetic, and the fourteenth is prosaic. Why should there not be a difference in poetic quality among the Psalms?

There is a difference. The honest reader will recognize it. It will be no harm to him if he should have his favourites among the poems which have been gathered from many centuries into this great collection.

There are some, like the Twenty-seventh, the Forty-second, the Forty-sixth, the Fifty-first, the Sixty-third, the Ninety-first, the Ninety-sixth, the One Hundred and Third, the One Hundred and Seventh, the One Hundred and Thirty-ninth, which rank with the noblest poetic literature of the world. Others move on a lower level, and show the traces of effort and constraint. There are also manifest alterations and interpolations, which are not always improvements. Dr. Perowne, who is one of the wisest and most conservative of modern commentators, says, “Many of the Psalms have not come down to us in their original form,”[8] and refers to the alterations which the Seventieth makes in the Fortieth, and the Fifty-third in the Fourteenth. The last two verses of the Fifty-first were evidently added by a later hand. The whole book, in its present[58] form, shows the marks of its compilation and use as the Hymn-Book of the Jewish people. Not only in the titles, but also in the text, we can discern the work of the compiler, critic, and adapter, sometimes wise, but occasionally otherwise.

The most essential thing in the appreciation of the poetry in the Psalms is the recognition of the three great spiritual qualities which distinguish them.

The first of these is the deep and genuine love of nature. The psalmists delight in the vision of the world, and their joy quickens their senses to read both the larger hieroglyphs of glory written in the stars and the delicate tracings of transient beauty on leaf and flower; to hear both the mighty roaring of the sea and the soft sweet laughter of the rustling corn-fields. But in all these they see the handwriting and hear the voice of God. It is His presence that makes the world sublime and beautiful. The direct, piercing, elevating sense of this presence simplifies, enlarges, and enables their style, and[59] makes it different from other nature-poetry. They never lose themselves, as Theocritus and Wordsworth and Shelley and Tennyson sometimes do, in the contemplation and description of natural beauty. They see it, but they always see beyond it. Compare, for example, a modern versified translation with the psalm itself:

Addison’s descriptive epithets betray a conscious effort to make a splendid picture. But the psalmist felt no need of this; a larger impulse lifted him at once into “the grand style:”

The second quality of the poetry in the Psalms is their passionate sense of the beauty of holiness. Keats was undoubtedly right in his suggestion that the poet must always see truth in the form of beauty. Otherwise he may be a philosopher, or a critic, or a[60] moralist, but he is not a true poet. But we must go on from this standpoint to the Platonic doctrine that the highest form of beauty is spiritual and ethical. The poet must also see beauty in the light of truth. It is the harmony of the soul with the eternal music of the Good. And the highest poets are those who, like the psalmists, are most ardently enamoured of righteousness. This fills their songs with sweetness and fire incomparable and immortal:

The third quality of the poetry of the Psalms is their intense joy in God. No lover ever poured out the longings of his heart toward his mistress more eagerly than the Psalmist voices his desire and thirst for God. No conqueror ever sang of victory more exultantly than the Psalmist rejoices in the Lord, who is his light and his salvation, the strength of his life and his portion forever.

After all, the true mission of poetry is to increase[61] joy. It must, indeed, be sensitive to sorrow and acquainted with grief. But it has wings given to it in order that it may bear us up into the air of gladness.

There is no perfect joy without love. Therefore love-poetry is the best. But the highest of all love-poetry is that which celebrates, with the Psalms,

There are four kinds of novels.

First, those that are easy to read and hard to remember: the well-told tales of no consequence, the cream-puffs of perishable fiction.

Second, those that are hard to read and hard to remember: the purpose-novels which are tedious sermons in disguise, and the love-tales in which there is no one with whom it is possible to fall in love.

Third, those that are hard to read and easy to remember: the books with a crust of perverse style or faulty construction through which the reader must break in order to get at the rich and vital meaning.

Fourth, those that are easy to read and easy to remember: the novels in which stories worth telling are well-told, and characters worth observing are vividly painted, and life is interpreted to the imagination[66] in enduring forms of literary art. These are the best-sellers which do not go out of print—everybody’s books.

In this fourth class healthy-minded people and unprejudiced critics put the novels of Charles Dickens. For millions of readers they have fulfilled what Dr. Johnson called the purpose of good books, to teach us to enjoy life or help us to endure it. They have awakened laughter and tears. They have enlarged and enriched existence by revealing the hidden veins of humour and pathos beneath the surface of the every-day world, and by giving “the freedom of the city” to those poor prisoners who had thought of it only as the dwelling-place of so many hundred thousand inhabitants and no real persons.

What a city it was that Dickens opened to us! London, of course, in outward form and semblance,—the London of the early Victorian epoch, with its reeking Seven Dials close to its perfumed Piccadilly, with its grimy river-front and its musty Inns of Court and its mildly rural suburbs, with its rollicking taverns and its deadly solemn residential squares and its gloomy debtors’ prisons and its gaily insanitary[67] markets, with all its consecrated conventions and unsuspected hilarities,—vast, portentous, formal, merry, childish, inexplicable, a wilderness of human homes and haunts, ever thrilling with sincerest passion, mirth, and pain,—London it was, as the eye saw it in those days, and as the curious traveller may still retrace some of its vanishing landmarks and fading features.

But it was more than London, after Dickens touched it. It was an enchanted city, where the streets seemed to murmur of joy or fear, where the dark faces of the dens of crime scowled or leered at you, and the decrepit houses doddered in senility, and the new mansions stared you down with stolid pride. Everything spoke or made a sign to you. From red-curtained windows jollity beckoned. From prison-doors lean hands stretched toward you. Under bridges and among slimy piers the river gurgled, and chuckled, and muttered unholy secrets. Across trim front-yards little cottages smiled and almost nodded their good-will. There were no dead spots, no deaf and dumb regions. All was alive and significant. Even the real estate[68] became personal. One felt that it needed but a word, a wave of the wand, to bring the buildings leaping, roistering, creeping, tottering, stalking from their places.

It was an enchanted city, and the folk who filled it and almost, but never quite, crowded it to suffocation, were so intensely and supernaturally human, so blackly bad, so brightly good, so touchingly pathetic, so supremely funny, that they also were creatures of enchantment and seemed to come from fairy-land.

For what is fairy-land, after all? It is not an invisible region, an impossible place. It is only the realm of the hitherto unobserved, the not yet realized, where the things we have seen but never noticed, and the persons we have met but never known, are suddenly “translated,” like Bottom the Weaver, and sent forth upon strange adventures.

That is what happens to the Dickens people. Good or bad they surpass themselves when they get into his books. That rotund Brownie, Mr. Pickwick, with his amazing troupe; that gentle compound of Hop-o’-my-Thumb and a Babe in the[69] Wood, Oliver Twist, surrounded by wicked uncles, and hungry ogres, and good fairies in bottle-green coats; that tender and lovely Red Riding-Hood, Little Nell; that impetuous Hans-in-Luck, Nicholas Nickleby; that intimate Cinderella, Little Dorrit; that simple-minded Aladdin, Pip; all these, and a thousand more like them, go rambling through Dickensopolis and behaving naturally in a most extraordinary manner.

Things that have seldom or never happened, occur inevitably. The preposterous becomes the necessary, the wildly improbable is the one thing that must come to pass. Mr. Dombey is converted, Mr. Krook is removed by spontaneous combustion, Mr. Micawber performs amazing feats as an amateur detective, Sam Weller gets married, the immortally absurd epitaphs of Young John Chivery and Mrs. Sapsea are engraved upon monuments more lasting than brass.

The fact is, Dickens himself was bewitched by the spell of his own imagination. His people carried him away, did what they liked with him. He wrote of Little Nell: “You can’t imagine how exhausted[70] I am to-day with yesterday’s labours. I went to bed last night utterly dispirited and done up. All night I have been pursued by the child; and this morning I am unrefreshed and miserable. I don’t know what to do with myself.... I think the close of the story will be great.” Again he says: “As to the way in which these characters have opened out [in Martin Chuzzlewit], that is to me one of the most surprising processes of the mind in this sort of invention. Given what one knows, what one does not know springs up; and I am as absolutely certain of its being true, as I am of the law of gravitation—if such a thing is possible, more so.”

Precisely such a thing (as Dickens very well understood) is not only possible, but unavoidable. For what certainty have we of the law of gravitation? Only by hearsay, by the submissive reception of a process of reasoning conducted for us by Sir Isaac Newton and other vaguely conceived men of science. The fall of an apple is an intense reality (especially if it falls upon your head); but the law which regulates its speed is for you an intellectual[71] abstraction as remote as the idea of a “combination in restraint of trade,” or the definition of “art for art’s sake.” Whereas the irrepressible vivacity of Sam Weller, and the unctuous hypocrisy of Pecksniff, and the moist humility of Uriah Heep, and the sublime conviviality of Dick Swiveller, and the triumphant make-believe of the Marchioness are facts of experience. They have touched you, and you cannot doubt them. The question whether they are actual or imaginary is purely academic.

Another fairy-land feature of Dickens’s world is the way in which minor personages of the drama suddenly take the centre of the stage and hold the attention of the audience. It is always so in fairy-land.

In The Tempest, what are Prospero and Miranda, compared with Caliban and Ariel? In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, who thinks as much of Oberon and Titania, as of Puck, and Bottom the Weaver? Even in an historical drama like Henry IV, we feel that Falstaff is the most historic character.

Dickens’s first lady and first gentleman are often less memorable than his active supernumeraries.[72] A hobgoblin like Quilp, a good old nurse like Peggotty, a bad old nurse like Sairey Gamp, a volatile elf like Miss Mowcher, a shrewd elf and a blunder-headed elf like Susan Nipper and Mr. Toots, a good-natured disreputable sprite like Charley Bates, a malicious gnome like Noah Claypole, a wicked ogre like Wackford Squeers, a pair of fairy-godmothers like the Cheeryble Brothers, a dandy ouphe like Mr. Mantalini, and a mischievous, wooden-legged kobold like Silas Wegg, take stronger hold upon us than the Harry Maylies and Rose Flemings, the John Harmons and Bella Wilfers, for whose ultimate matrimonial felicity the business of the plot is conducted. Even the more notable heroes often pale a little by comparison with their attendants. Who remembers Martin Chuzzlewit as clearly as his servant Mark Tapley? Is Pip, with his Great Expectations, half as delightful as his clumsy dry-nurse Joe Gargery? Has even the great Pickwick a charm to compare with the unique, immortal Sam Weller?

Do not imagine that Dickens was unconscious of this disarrangement of rôles, or that it was an evidence[73] of failure on his part. He knew perfectly well what he was doing. Great authors always do. They cannot help it, and they do not care. Homer makes Agamemnon and Priam the kings of his tale, and Paris the first walking gentleman and Helen the leading lady. But Achilles and Ajax and Hector are the bully boys, and Ulysses is the wise jester, and Thersites the tragic clown. As for Helen,—

her reputed pulchritude means less to us than the splendid womanhood of Andromache, or the wit and worth of the adorable matron Penelope.

Now this unconventionality of art, which disregards ranks and titles, even those of its own making, and finds the beautiful and the absurd, the grotesque and the picturesque, the noble and the base, not according to the programme but according to the fact, is precisely the essence of good enchantment.

Good enchantment goes about discovering the ass in the lion’s skin and the wolf in sheep’s clothing, the princess in the goose-girl and the wise man under[74] the fool’s cap, the pretender in the purple robe and the rightful heir in rags, the devil in the belfry and the Redeemer among the publicans and sinners. It is the spirit of revelation, the spirit of divine sympathy and laughter, the spirit of admiration, hope, and love—or better still, it is simply the spirit of life.

When I call this the essence of good enchantment I do not mean that it is unreal. I mean only that it is unrealistic, which is just the opposite of unreal. It is not in bondage to the beggarly elements of form and ceremony. It is not captive to names and appearances, though it revels in their delightful absurdity. It knows that an idol is nothing, and finds all the more laughter in its pompous pretence of being something. It can afford to be merry because it is in earnest; it is happy because it has not forgotten how to weep; it is content because it is still unsatisfied; it is humble in the sense of unfathomed faults and exalted in the consciousness of inexhaustible power; it calls nothing common or unclean; it values life for its mystery, its surprisingness, and its divine reversals of human prejudice,—just like[75] Beauty and the Beast and the story of the Ugly Duckling.

This, I say, is the essence of good enchantment; and it is also the essence of true religion. “For God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise, and the weak things of the world to confound the mighty, and base things of the world and things which are despised, yea, and things which are not, to bring to naught things which are.”

This is also the essence of real democracy, which is not a theory of government but a state of mind.

No one has ever expressed it better than Charles Dickens did in a speech which he made at Hartford, Connecticut, seventy years ago. “I have faith,” said he, “and I wish to diffuse faith in the existence—yes, of beautiful things, even in those conditions of society which are so degenerate, so degraded and forlorn, that at first sight it would seem as though it could only be described by a strange and terrible reversal of the words of Scripture—God said let there be light, and there was none. I take it that we are born, and that we hold[76] our sympathies, hopes, and energies in trust for the Many and not the Few. That we cannot hold in too strong a light of disgust and contempt, before our own view and that of others, all meanness, falsehood, cruelty, and oppression of every grade and kind. Above all, that nothing is high because it is in a high place; and that nothing is low because it is in a low place. This is the lesson taught us in the great book of Nature. This is the lesson which may be read alike in the bright track of the stars, and in the dusty course of the poorest thing that drags its tiny length upon the ground.”

This was the creed of Dickens; and like every man’s creed, conscious or unconscious, confessed or concealed, it made him what he was.

It has been said that he had no deep philosophy, no calmly reasoned and clearly stated theory of the universe. Perhaps that is true. Yet I believe he hardly missed it. He was too much interested in living to be anxious about a complete theory of life. Perhaps it would have helped him when trouble came, when domestic infelicity broke up his home, if he could have climbed into some philosopher’s[77] ivory tower. Perhaps not. I have observed that even the most learned and philosophic mortals, under these afflictions, sometimes fail to appreciate the consolations of philosophy to any noticeable extent. From their ivory towers they cry aloud, being in pain, even as other men.

But it was certainly not true (even though his biographer wrote it, and it has been quoted a thousand times), that just because Dickens cried aloud, “there was for him no ‘city of the mind’ against outward ills, for inner consolation and shelter.” He was not cast out and left comfortless. Faith, hope, and charity—these three abode with him. His human sympathy, his indomitable imagination, his immense and varied interest in the strange adventures of men and women, his unfaltering intuition of the truer light of God that burns

these were the celestial powers and bright serviceable angels that built and guarded for him a true “city of refuge,” secure, inviolate, ever open to the fugitive in the day of his calamity. Thither he[78] could flee to find safety. There he could ungird his heart and indulge

there he could laugh and sing and weep with the children, the dream-children, which God had given him; there he could enter into his work-shop and shut the door and lose himself in joyous labour which should make the world richer by the gift of good books. And so he did, even until the end came and the pen fell from his fingers, he sitting safe in his city of refuge, learning and unfolding The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

O enchanted city, great asylum in the mind of man, where ideals are embodied, and visions take form and substance to parley with us! Imagination rears thy towers and Fancy populates thy streets; yet art thou a city that hath foundations, a dwelling eternal though unseen. Ever building, changing, never falling, thy walls are open-gated day and night. The fountain of youth is in thy gardens, the treasure of the humble in thy storehouses. Hope is thy doorkeeper, and Faith thy warden, and Love thy Lord. In thee the wanderer may take shelter[79] and find himself by forgetting himself. In thee rest and refreshment are waiting for the weary, and new courage for the despondent, and new strength for the faint. From thy magic casements we have looked upon unknown horizons, and we return from thy gates to our task, our toil, our pilgrimage, with better and braver hearts, knowing more surely that the things which are seen were not made of things which do appear, and that the imperishable jewels of the universe are in the souls of men. O city of good enchantment, for my brethren and companions’ sakes I will now say: Peace be within thee!

Of the outward appearance, or, as Sartor Resartus would have called it, the Time-Vesture and Flesh-Garment of that flaming light-particle which was cast hither from Heaven in the person of Charles Dickens, and of his ways and manners while he hasted jubilantly and stormfully across the astonished Earth, something must be said here.

Charles Dickens was born at Portsea, in 1812, an offspring of what the accurate English call the[80] “lower middle class.” Inheriting something from a father who was decidedly Micawberish, and a mother who resembled Mrs. Nickleby, Charles was not likely to be a humdrum child. But the remarkable thing about him was the intense, aspiring, and gaily sensible spirit with which he entered into the business of developing whatever gifts he had received from his vague and amiable parents.

The fat streak of comfort in his childish years, when his proud father used to stand the tiny lad on a table to sing comic songs for an applauding audience of relatives, could not spoil him. The lean streak of misery, when the improvident family sprawled in poverty, with its head in a debtors’ prison, while the bright, delicate, hungry boy roamed the streets, or drudged in a dirty blacking-factory, could not starve him. The two dry years of school at Wellington House Academy could not fossilize him. The years from fifteen to nineteen, when he was earning his bread as office-boy, lawyers’ clerk, shorthand reporter, could not commercialize him. Through it all he burned his way painfully and joyously.

He was not to be detailed as a perpetual comic songster in upholstered parlors; nor as a prosperous frock-coated citizen with fatty degeneration of the mind; nor as a newspaper politician, a power beneath the footstool. None of these alluring prospects delayed him. He passed them by, observing everything as he went, now hurrying, now sauntering, for all the world like a boy who has been sent somewhere. Where it was, he found out in his twenty-fifth year, when the extraordinary results of his self-education bloomed in the Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist.

Never was a good thing coming out of Nazareth more promptly welcomed. The simple-minded critics of that day had not yet discovered the damning nature of popularity, and they hailed the new genius in spite of the fact that hundreds of thousands of people were reading his books. His success was exhilarating, overwhelming, and at times intoxicating.

Some of them had thorns, which hurt his thin skin horribly, but they never made him despair or doubt[82] the goodness of the universe. Being vexed, he let it off in anger instead of distilling it into pessimism to poison himself. Life was too everlastingly interesting for him to be long unhappy. A draught of his own triumph would restore him, a slice of his own work would reinvigorate him, and he would go on with his industrious dreaming.

No one enjoyed the reading of his books more than he the making of them, though he sometimes suffered keenly in the process. That was a proof of his faith that happiness does not consist in the absence of suffering, but in the presence of joy. Dulness, insincerity, stupid humbug—voilà l’ennemi! So he lived and wrote with a high hand and an outstretched arm. He made men see what he saw, and hate what he hated, and love what he loved. This was his great reward,—more than money, fame, or hosts of friends,—that he saw the children of his brain enter into the common life of the world.

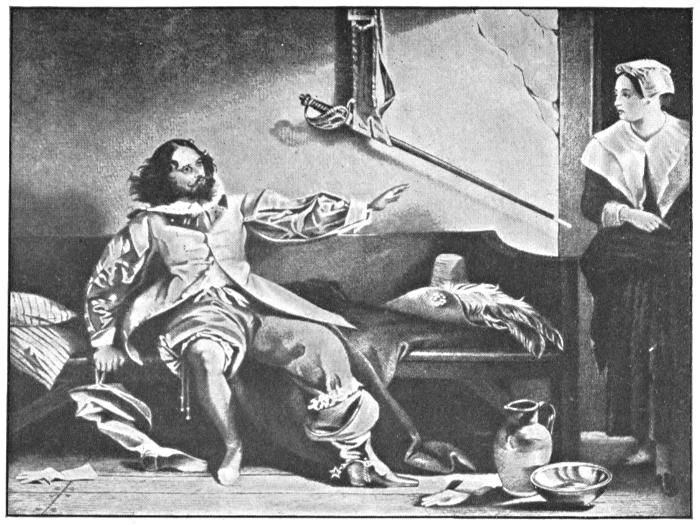

CHARLES DICKENS AS CAPTAIN BOBADIL IN “EVERY MAN IN HIS HUMOUR.”

Painted by C. R. Leslie.

But he was not exempt from the ordinary laws of nature. The conditions of his youth left their marks for good and evil on his maturity. The petting of his babyhood gave him the habit of showing[83] off. We often see him as a grown man, standing on the table and reciting his little piece, or singing his little song, to please an admiring audience. He delighted in playing to the galleries.

His early experience of poverty made him at once tremendously sympathetic and invincibly optimistic—both of which virtues belong to the poor more than to the rich. Dickens understood this and never forgot it. The chief moralities of his poor people are mutual helpfulness and unquenchable hopefulness. From them, also, he caught the tone of material comfort which characterizes his visions of the reward of virtue. Having known cold and hunger, he simply could not resist the desire to make his favourite characters—if they stayed on earth till the end of the book—warm and “comfy,” and to give them plenty to eat and drink. This may not have been artistic, but it was intensely human.

The same personal quality may be noted in his ardour as a reformer. No writer of fiction has ever done more to better the world than Charles Dickens. But he did not do it by setting forth programmes of legislation and theories of government. As a[84] matter of fact, he professed an amusing “contempt for the House of Commons,” having been a Parliamentary reporter; and of Sir Robert Peel, who emancipated the Catholics, enfranchised the Jews, and repealed the Corn Laws, he thought so little that he caricatured him as Mr. Pecksniff.