Changes that have been made are listed at the end of the book.

Parishes in Shetland: 1 Unst 2 Fetlar 3 Yell 4 Northmavine 5 Delting 6 Walls 7 Sandsting 8 Nesting 9 Tingwall 10 Lerwick 11 Bressay 12 Dunrossness

Parishes in Orkney: 1 Papa Westray 1b. Westray & Papa Westray 2 Cross & Burness 3 Lady 4 Stronsay 5 Rowsay & Egilshay 6 Evie & Rendall 7 Harray & Birsay 8 Sandwick 9 Stromness 10 Firth 11 Orphir 12 Kirkwall & St. Ola 13 Shapinshay 14 Deerness & St. Andrews 15 Holm 16 Hoy & Graemsay 17 Walls & Flotta 18 South Ronaldshay 19 Stenness 20 Eday & Pharay

The Cambridge University Press

Copyright. George Philip & Son Ltd.

CAMBRIDGE COUNTY GEOGRAPHIES

SCOTLAND

General Editor: W. Murison, M.A.

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.4

C. F. CLAY, Manager

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

Toronto: J. M. DENT & SONS, Ltd.

Tokyo: MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

Cambridge County Geographies

ORKNEY

AND

SHETLAND

by

J. G. F. MOODIE HEDDLE

and

T. MAINLAND, F.E.I.S.

Headmaster, Bressay Public School

With Maps, Diagrams, and Illustrations

CAMBRIDGE

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

1920

Printed in Great Britain

by Turnbull & Spears, Edinburgh

ORKNEY

| PAGE | |||

| 1. | County and Shire | 1 | |

| 2. | General Characteristics and Natural Conditions | 2 | |

| 3. | Size. Situation. Boundaries | 5 | |

| 4. | Streams and Lakes | 8 | |

| 5. | Geology and Soil | 10 | |

| 6. | Natural History | 14 | |

| 7. | The Coast | 26 | |

| 8. | Weather and Climate | 30 | |

| 9. | The People—Race, Language, Population | 35 | |

| 10. | Agriculture | 37 | |

| 11. | Industries and Manufactures | 39 | |

| 12. | Fisheries and Fishing Station | 41 | |

| 13. | History of the County | 43 | |

| 14. | Antiquities | 59 | |

| 15. | Architecture—(a) Ecclesiastical | 68 | |

| 16. | Architecture—(b) Castellated | 74 | [vi] |

| 17. | Architecture—(c) Municipal and Domestic | 79 | |

| 18. | Communications, Past and Present | 83 | |

| 19. | Administration and Divisions | 85 | |

| 20. | The Roll of Honour | 86 | |

| 21. | The Chief Towns and Villages of Orkney | 96 | |

ORKNEY

| PAGE | |

| Rackwick, Hoy | 3 |

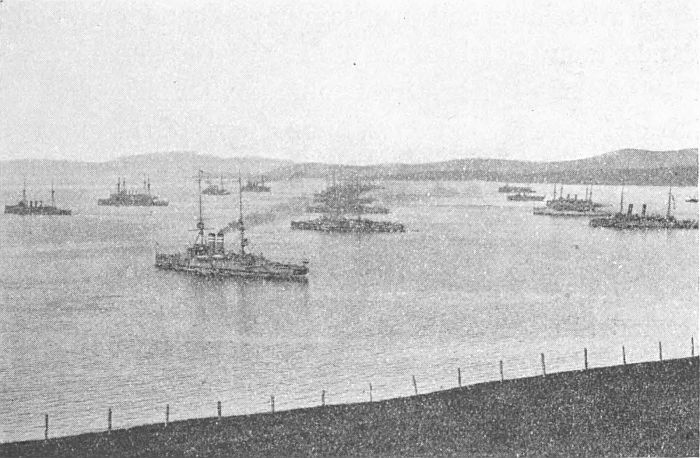

| The Home Fleet in Scapa Flow | 7 |

| Loch of Kirbuster, in Orphir | 9 |

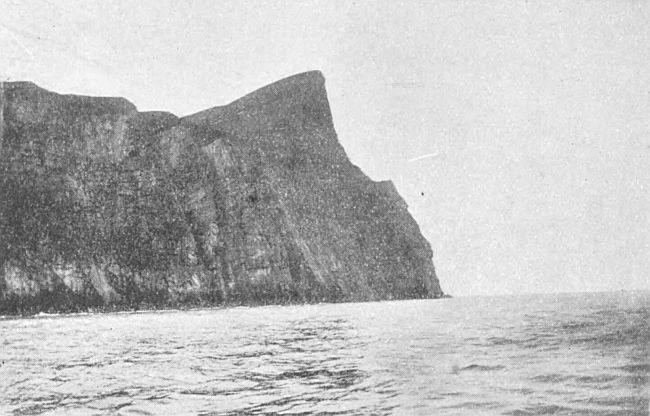

| Berry Head, Hoy | 12 |

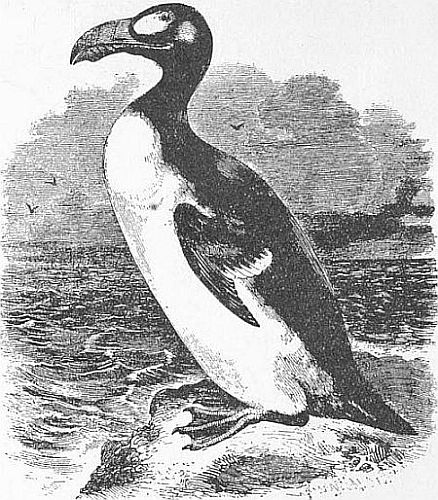

| The Great Auk | 18 |

| Crannie in which last Great Auk lived | 19 |

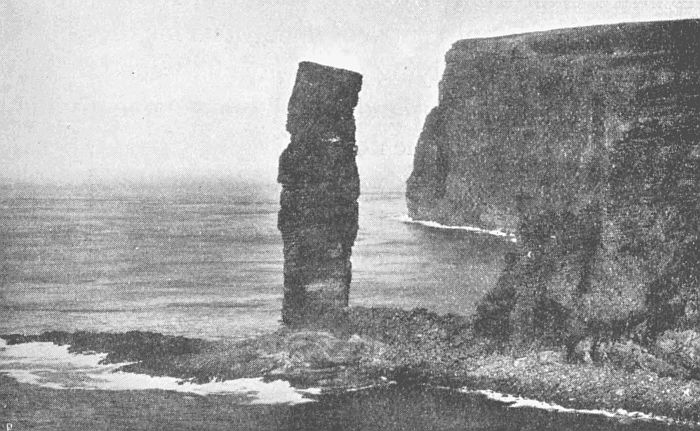

| The Old Man of Hoy | 27 |

| Old Melsetter House, in Walls | 32 |

| Harvesting at Stenness | 38 |

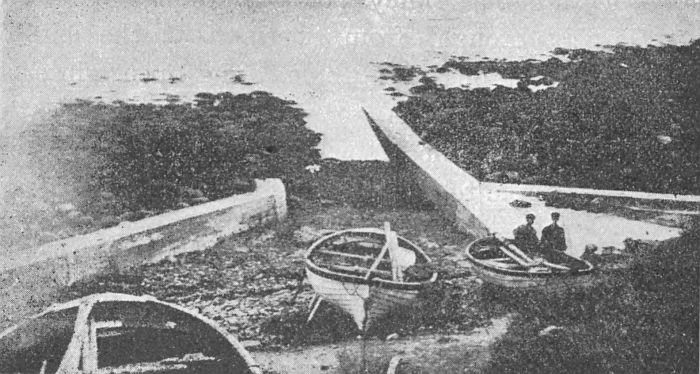

| Orkney Yawl Boats | 40 |

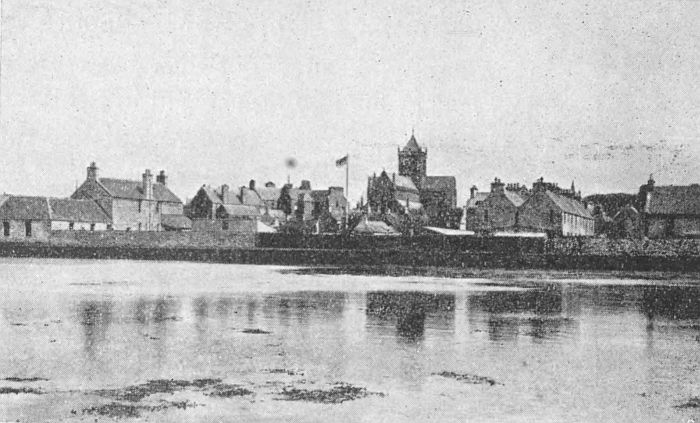

| Kirkwall | 46 |

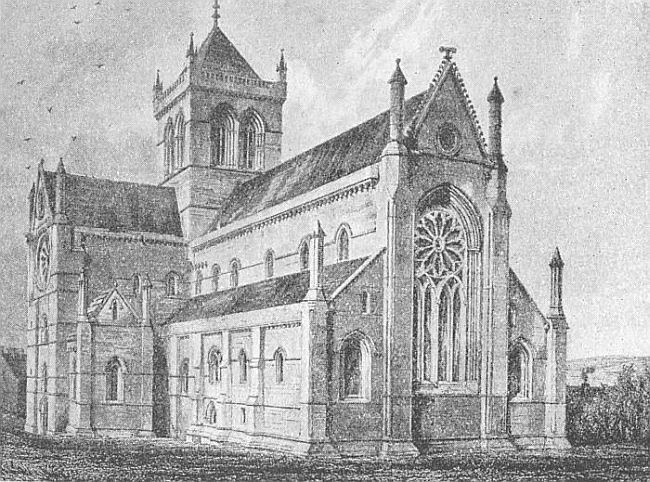

| St Magnus’s Cathedral, Kirkwall, from South-East | 51 |

| Tankerness House and St Magnus’s Cathedral | 54 |

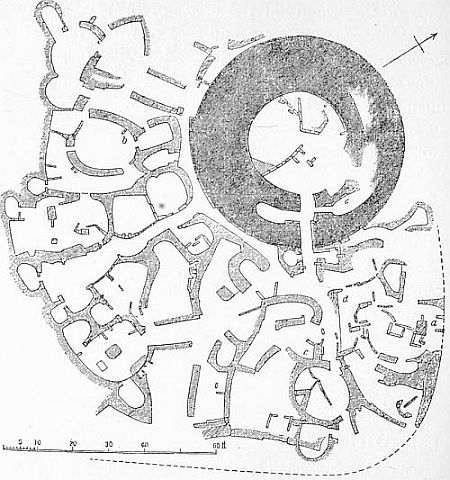

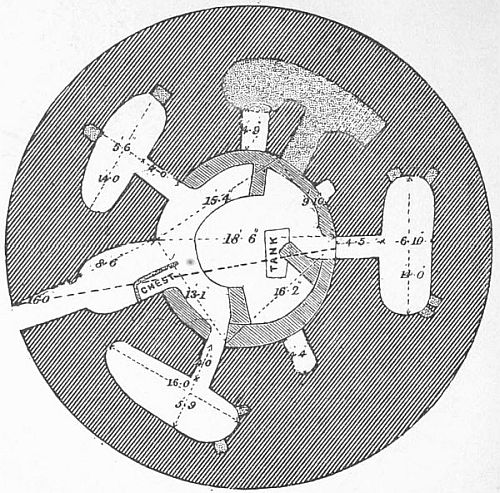

| Ground Plan of Broch of Lingrow, near Kirkwall | 60 |

| Stone Circle of Stenness | 62 |

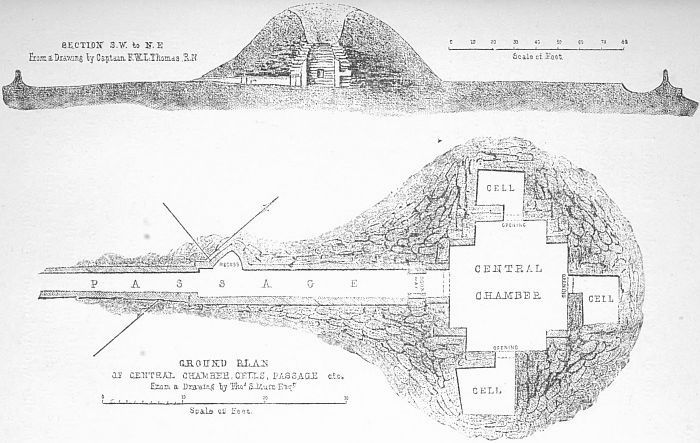

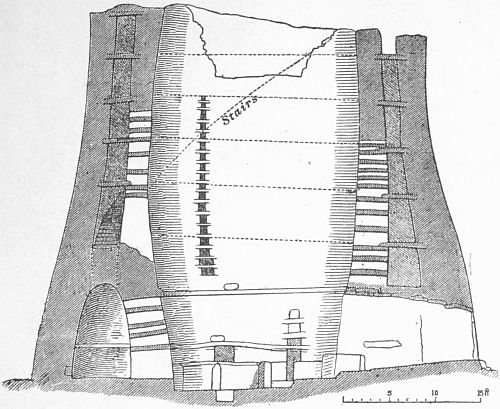

| Maeshowe, Section and Ground Plan | 63 |

| Incised Dragon, from Maeshowe | 66 |

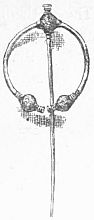

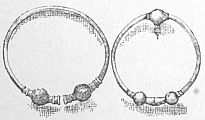

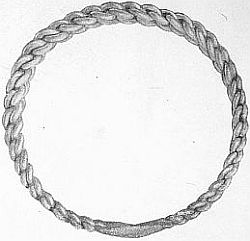

| Norse Brooch, found in Sandwick | 67 |

| Silver Ornaments, found in Sandwick | 67 |

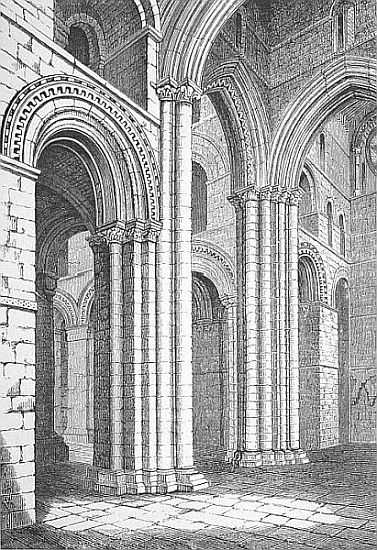

| St Magnus’s Cathedral, view from N. Transept looking towards Choir | 69 |

| [viii] | |

| St Magnus’s Church, Egilsay | 71 |

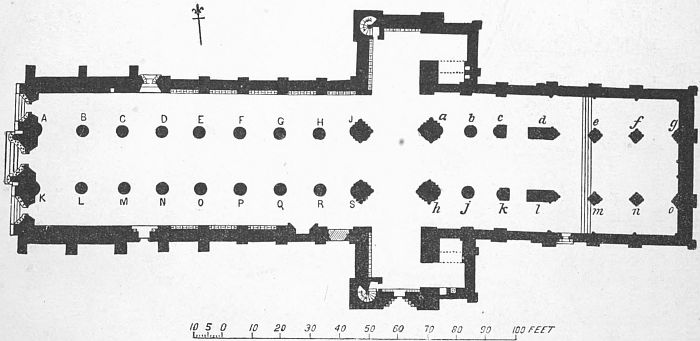

| Ground Plan of St Magnus’s Cathedral, Kirkwall | 72 |

| Apse of ancient Round Church, in Orphir | 73 |

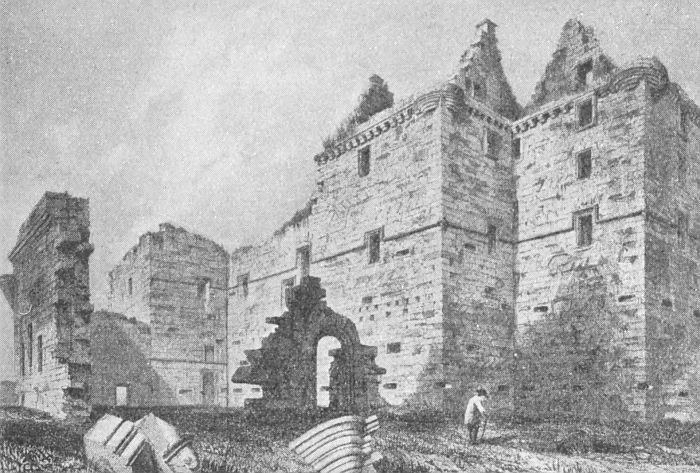

| Noltland Castle, Westray (15th century) | 75 |

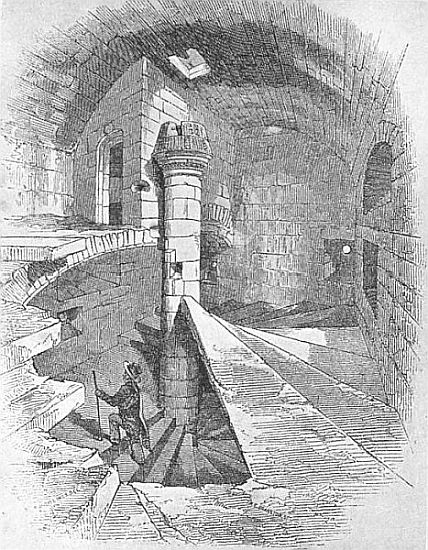

| The Staircase, Noltland Castle | 76 |

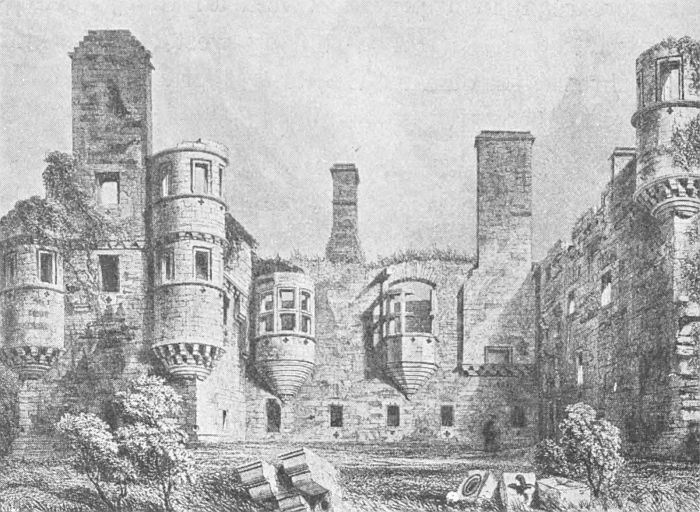

| The Earl’s Palace at Kirkwall (c. A.D. 1600) | 78 |

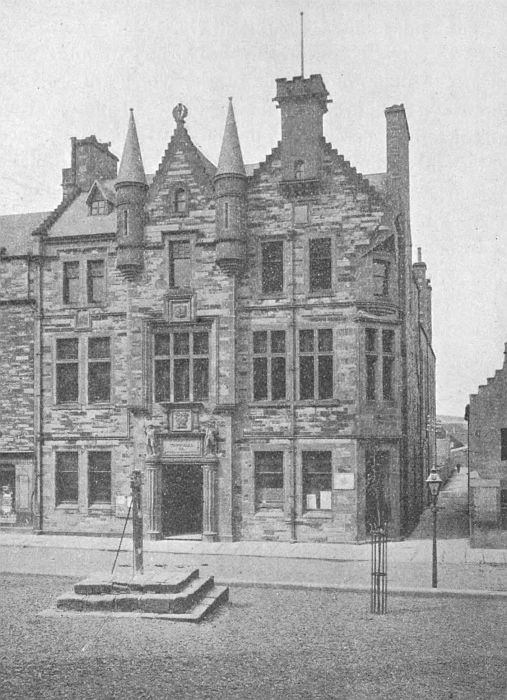

| Town Hall, Kirkwall | 80 |

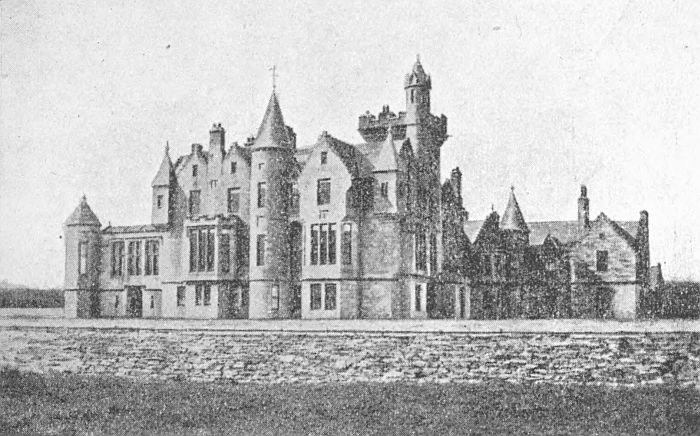

| Balfour Castle, Shapinsay | 81 |

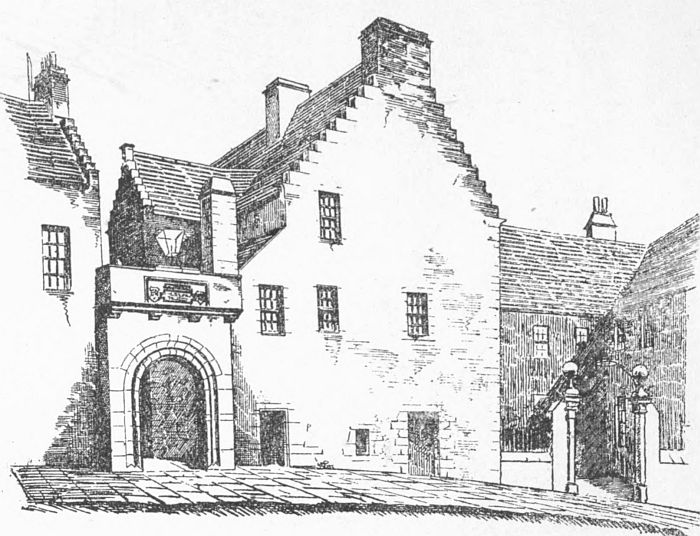

| Tankerness House, Kirkwall | 82 |

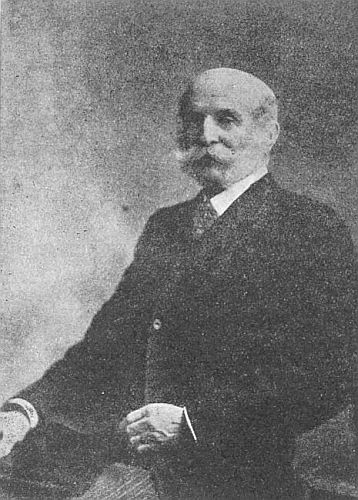

| John Rae | 88 |

| David Vedder | 89 |

| Sir Robert Strange, the Engraver | 92 |

| Malcolm Laing | 94 |

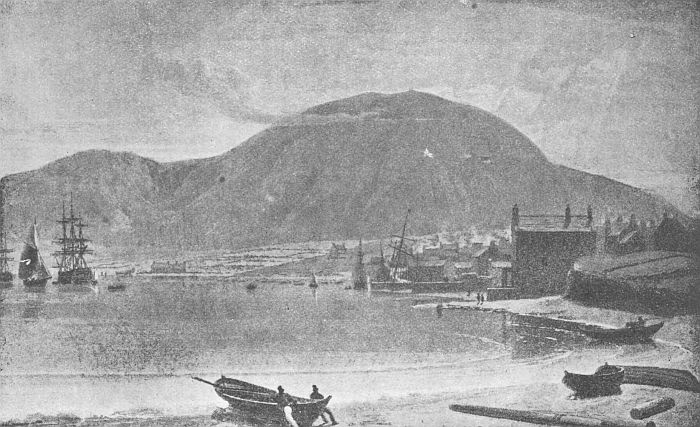

| Stromness, Orkney, about the year 1825 | 97 |

| Orographical Maps of Orkney and Shetland | Front Cover |

| Geological Maps of Orkney and Shetland | Back Cover |

The illustrations on pp. 3, 7, 9, 12, 27, 38, 46, 54, 62, 80, 81 are reproduced from photographs by Mr T. Kent, Kirkwall; that on p. 32 from a photograph by the Author; that on p. 40 by permission of Messrs J. Spence & Son, St Margaret’s Hope; those on pp. 60 and 72 are from Tudor’s Orkney and Shetland, by permission of Edward Stanford, Ltd., that on p. 69 by kind permission of Messrs William Peace & Son, Kirkwall; that on p. 71 from a photograph by Valentine & Sons, Ltd., that on p. 82 by kind permission of Dr Thomas Ross; and that on p. 88 by arrangement with Elliott & Fry, Ltd.

SHETLAND

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | County and Shire. Name and Administration of Shetland | 103 |

| 2. | General Characteristics | 104 |

| 3. | Size. Position. Boundaries | 106 |

| 4. | Surface and General Features | 107 |

| 5. | Geology and Soil | 109 |

| 6. | Natural History | 111 |

| 7. | Round the Coast—(a) Along the East from Fair Isle to Unst |

116 |

| 8. | Round the Coast—(b) Along the West from Fethaland to Fitful Head |

124 |

| 9. | Climate | 127 |

| 10. | People—Race, Language, Population | 133 |

| 11. | Agriculture and other Industries | 134 |

| 12. | Fishing | 139 |

| [x] | ||

| 13. | Shipping and Trade | 143 |

| 14. | History | 145 |

| 15. | Antiquities | 147 |

| 16. | Architecture | 153 |

| 17. | Communications | 156 |

| 18. | Roll of Honour | 157 |

| 19. | The Chief Towns and Villages of Shetland | 161 |

SHETLAND

| PAGE | |

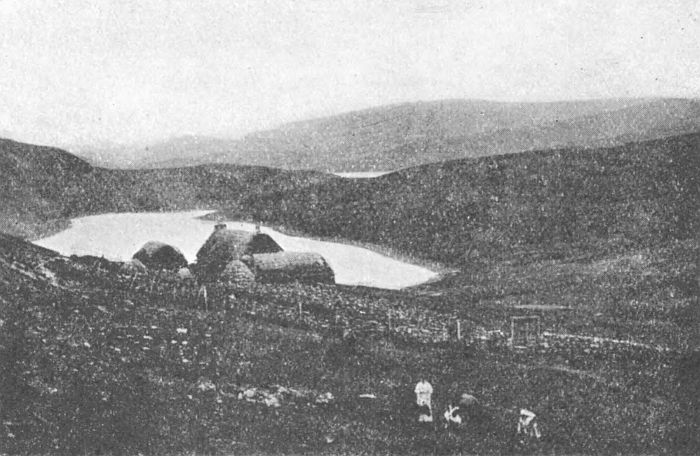

| Crofter’s Cottage | 104 |

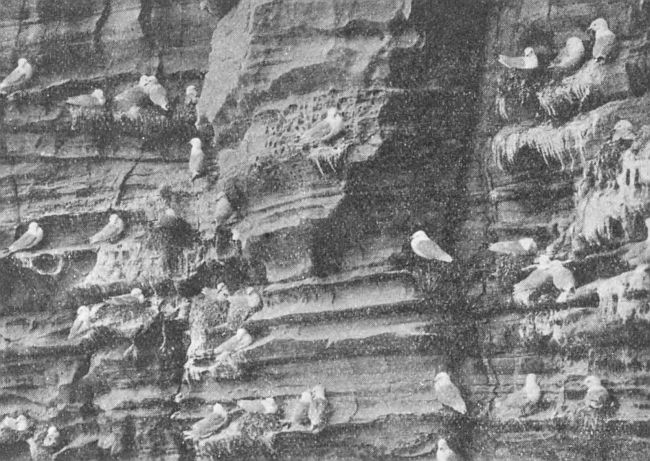

| Kittiwakes. Noss Isle | 112 |

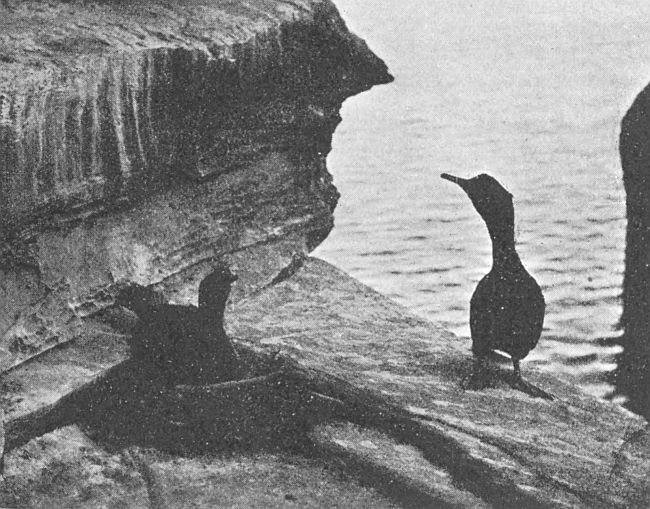

| Shag on Nest. Noss Isle | 113 |

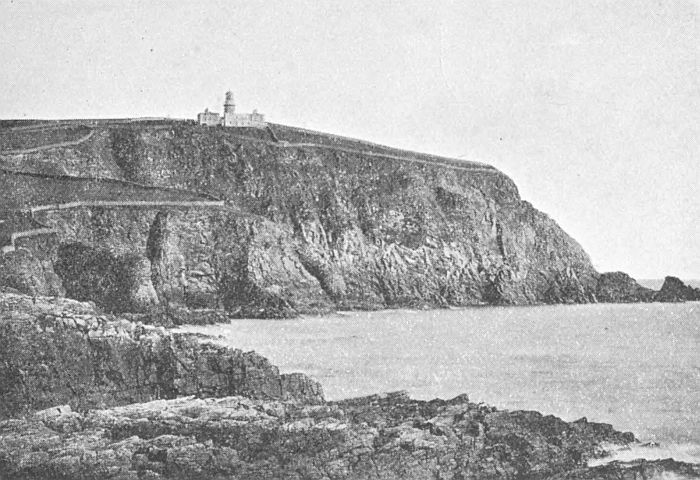

| Sumburgh Head and Lighthouse | 117 |

| Bressay Lighthouse and Foghorn | 118 |

| Cliff Scenery, Noss. Bressay | 119 |

| Mavis Grind, looking south | 121 |

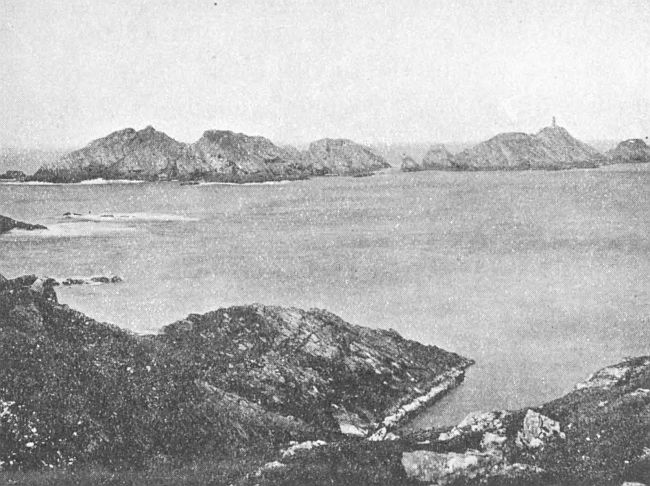

| Muckle Flugga Lighthouse | 123 |

| The Kame, Foula | 126 |

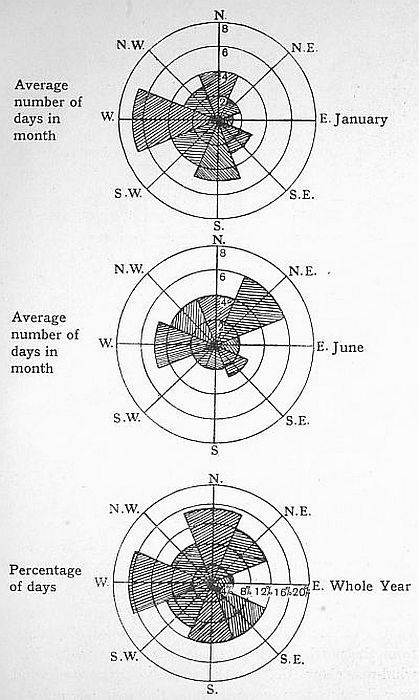

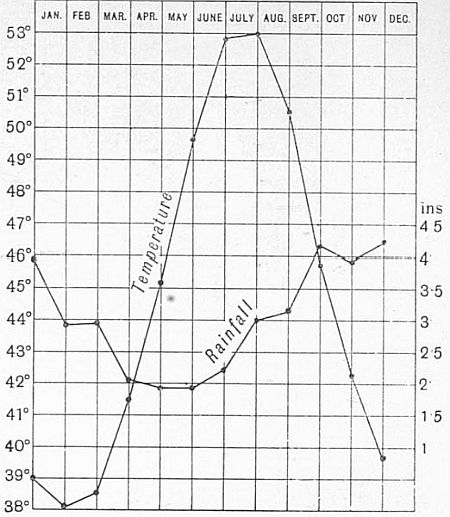

| Wind Roses, showing the prevailing winds at Sumburgh Head | 129 |

| Graph showing average Rainfall and Temperature | 130 |

| Sunrise at Midsummer, 2.30 a.m. | 132 |

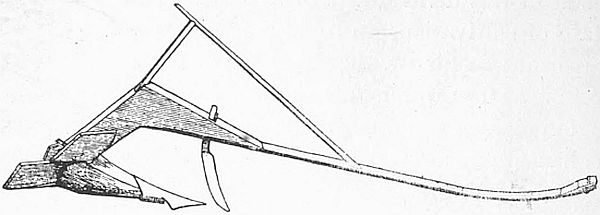

| Single-Stilted Shetland Plough | 136 |

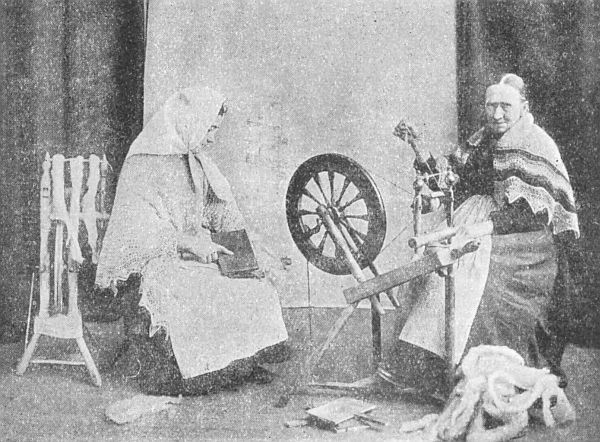

| Carding and Spinning | 137 |

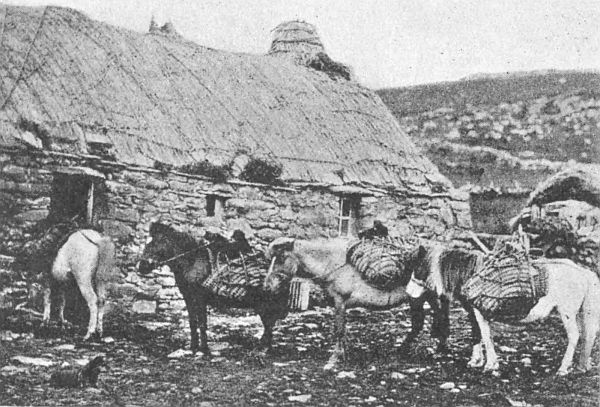

| “Leading” Home the Peats | 138 |

| Dutch Fishing Fleet in Lerwick Harbour | 140 |

| Steam Drifters and Fish Market, Lerwick | 141 |

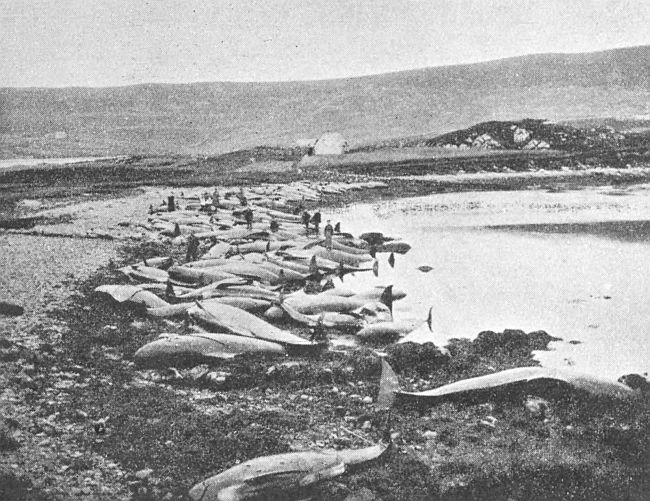

| Shoal of Whales | 143 |

| [xii] | |

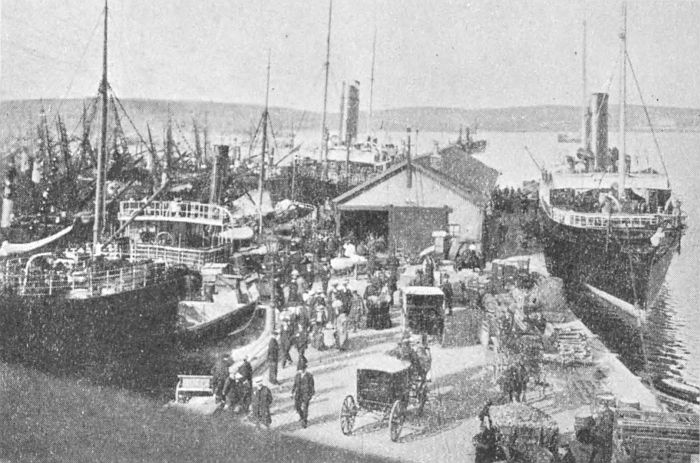

| A Busy Day at Victoria Pier, Lerwick | 144 |

| Broch of Mousa | 147 |

| Ground Plan, Broch of Mousa | 148 |

| Sectional Elevation, Broch of Mousa | 149 |

| Gold Armlet (Norse) from Isle of Oxna | 150 |

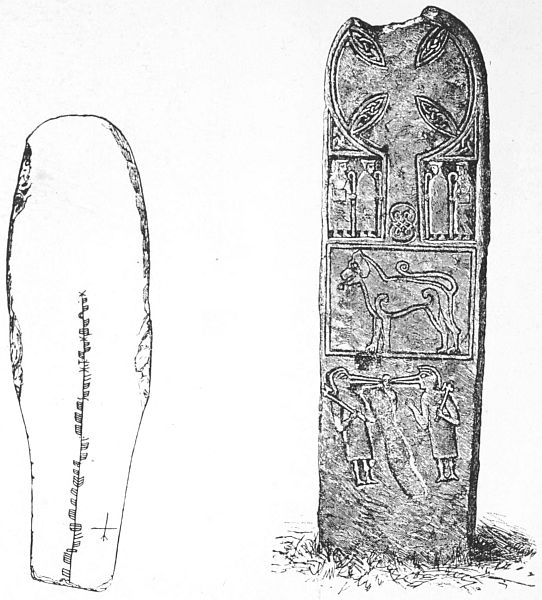

| Bressay Stone. Obverse and Reverse | 151 |

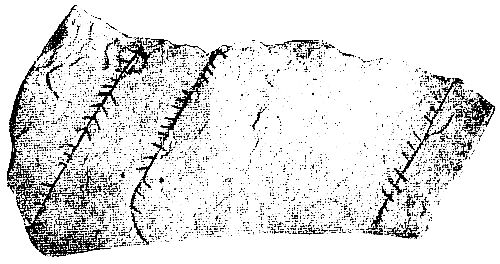

| Sandstone Slab with Ogham Inscription from Cunningsburgh | 151 |

| Lunnasting Stone | 152 |

| Burra Stone | 152 |

| Scalloway Castle | 153 |

| Muness Castle, Unst | 154 |

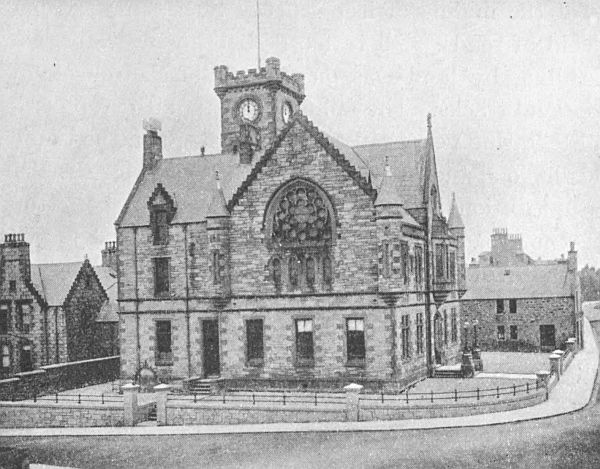

| Town Hall, Lerwick (Midnight, June) | 155 |

| Arthur Anderson | 158 |

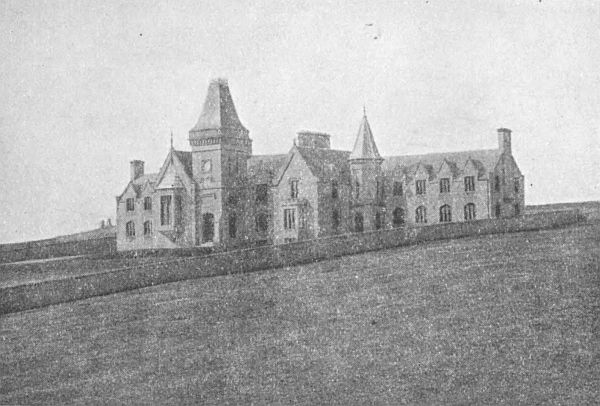

| Anderson Institute, Lerwick | 159 |

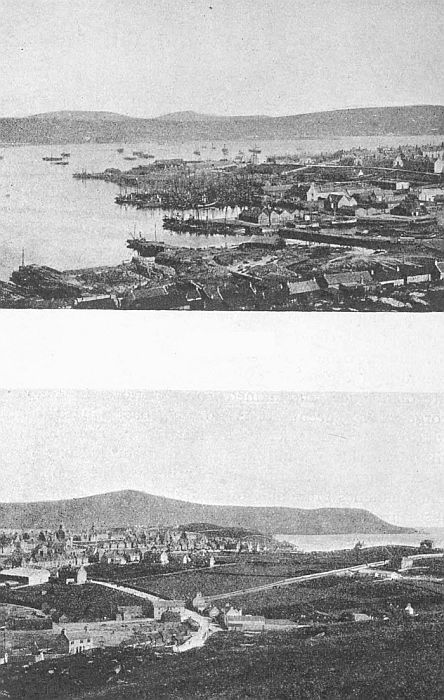

| Lerwick, North and South | 162 |

| Scalloway | 163 |

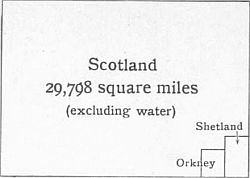

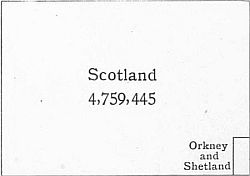

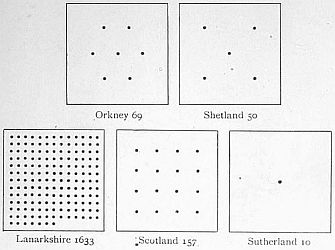

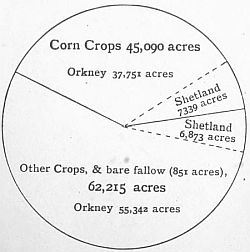

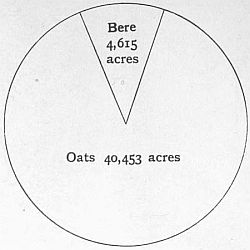

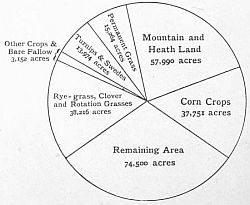

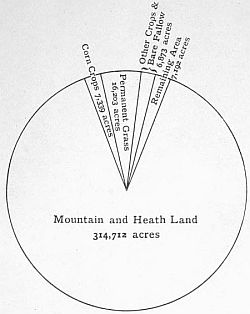

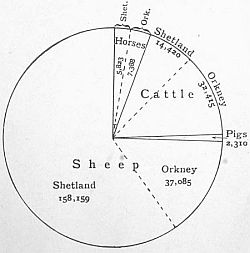

| Diagrams | 164 |

The illustrations on pp. 104, 112, 113, 118, 119, 162, are from photographs by Mr J. D. Ratter, Lerwick; those on pp. 117, 121, 123, 126, 132, 138, 140, 141, 143, 144, 147, 153, 154, 155, 159, 163, by Mr R. H. Ramsay, Lerwick; that on p. 137 by Valentine & Sons, Ltd., those on pp. 148, 149, 152, are from Tudor’s Orkney and Shetland by permission of Edward Stanford, Ltd., and that on p. 158 by permission of Mr J. Nicolson of Glenmount, Lerwick.

By J. G. F. MOODIE HEDDLE

I wish to thank Captain Malcolm Laing of Crook for the photograph from Sir Henry Raeburn’s portrait of Malcolm Laing, the historian; Andrew Wylie, Esquire, Provost of Stromness, for the portraits of Dr Rae and David Vedder; and J. A. Harvie-Brown, Esquire, Dunipace House, Stirlingshire, for the photograph of the Great Auk’s resting-place.

J. G. F. M. H.

The word shire is of Old English origin, and meant charge, administration. The Norman Conquest introduced an alternative designation, the word county—through Old French from Latin comitatus, which in mediaeval documents stands for shire. County denotes the district under a count, the king’s comes, the equivalent of the older English term earl. This system of local administration entered Scotland as part of the Anglo-Norman influence that strongly affected our country after 1100.

The exceptional character of the historical nexus between the Orkney Islands and Scotland, makes it somewhat difficult to fix definitely the date at which Orkney can be fairly said to have first constituted a Scottish county. For a period of about one hundred and fifty years after the conditional and, to all intent, temporary cession of the Islands to Scotland in the year 1468, Scottish and Norse law overlapped each other to a large extent in Orkney. And although during that period the Scottish Crown both invested earls, and appointed sheriffs of Orkney, yet so long as Norse law subsisted in the Islands, as it did largely in practice and absolutely in theory until the year 1612, it is hardly possible to consider Orkney a Scottish county. The [2]relation of the Islands towards Scotland during this confused period of fiscal evolution bears more resemblance to that of the Isle of Man towards England at the present day. When, however, in the year 1612 an Act of the Scottish Privy Council applied the general law of Scotland to the Islands, although the proceeding was in defiance of the conditions of their cession, Orkney may be held to have at last entered into the full comity of Scottish civil life, and may thenceforth, without impropriety or cavil, be considered and spoken of as the County or Shire of Orkney.

The Latin name Orcades implies the islands adjacent to Cape Orcas, a promontory first mentioned by Diodorus Siculus about 57 b.c. as one of the northern extremities of Britain, and commonly held to be Dunnet Head.

The Norse name was Orkneyar, of which our Orkney is a curtailment. The name orc appears to have been applied by both Celtic and Teutonic races to some half-mythical sea-monster, which according to Ariosto, in Orlando Furioso, devoured men and women; but the suggested connection between this animal and the name of the county appears a little far-fetched, although the large number of whales in the surrounding waters is quoted to support it.

Rackwick, Hoy

Orkney occupies the somewhat anomalous position of being a wholly insular shire whose economic interests [3]are overwhelmingly agricultural. Most of the islands are flat or low; and in several, such as Shapinsay, Stronsay, Sanday, and South Ronaldshay, the proportion of cultivated land exceeds 70 per cent. of their total areas. In the Mainland, however, there are large stretches of hill and moorland, while in Hoy and Walls the natural conditions of by far the greater portion of the island closely approximate to those of the Scottish Highlands. Rousay is the only other island which is to a large extent hilly; but Westray and Eday have some hills, and Burray, Flotta, and several other islands considerable stretches of low-lying moor. The general rise of the land is from N.E. to S.W. A height of 334 feet is attained at the Ward Hill at the south end of Eday, [4]880 feet at the Ward Hill of Orphir, in the S.W. of the Mainland, 1420 at Cuilags, 1564 at Ward Hill, and 1309 at Knap of Trowieglen, the three highest points in Hoy and in the whole group. Exceptionally fine views are obtained from Wideford Hill (741 feet), near Kirkwall, and from the Ward Hill in Hoy, the varied panoramas of islands, sounds, and lakes perhaps gaining in grace of outline more than they lose in richness of detail from the woodless character of the country.

Taken in detail, and viewed from the low ground, however, the general aspect of much of the country is bleak, and only redeemed from baldness by the widely-spread evidence of a vigorous cultivation. Yet for reasons of a somewhat complex texture, involving meteorological conditions, historical and archaeological considerations, and a touch of all-round individuality, the Islands rarely fail to cast a spell upon the visitor. One might quote many distinguished writers to vouch for this fact, but an Orcadian poet has depicted the telling features of his native land, both physical and psychic, with unerring accuracy and skill.

If we allow a little for the softer side of the picture, a side perhaps best typified by the fine old buildings of the little island capital, and the spell of the lightful midsummer night, which is no night, the lines of Vedder form a fair compendium of the natural conditions and general characteristics of the Islands to-day, although much of the “bleak and treeless moor” of the poet’s youth has long since been converted into smiling fields of corn.

The Orkney Islands extend between the parallels 58° 41´ and 59° 24´ of north latitude, and 2° 22´ and [6]3° 26´ of west longitude. They measure 56 miles from north-east to south-west, and 29 miles from east to west, and cover 240,476 acres or 375.5 square miles, exclusive of fresh water lochs. The group is bounded by the North Sea and the Pentland Firth on the south, the Atlantic on the west, Sumburgh Roost on the north, and the North Sea on the east. Our measurements take no account of the distant Sule Skerry, an islet of 35 acres lying 32½ miles north-west of Hoy Head, and inhabited only by lightkeepers and innumerable birds. The archipelago is naturally divided into three sections: the Mainland in the centre, the South Isles including all islands to the south, and the North Isles all to the north, of the Mainland. The Mainland—the Norse Meginland, or Hrossey, i.e. Horse Island—covers 190 square miles, and is 25 miles long from north-west to south-east, and 15 miles broad from east to west. It is divided into two unequal portions, the East Mainland and the West Mainland, by an isthmus less than two miles across, which connects Kirkwall Bay on its north sea-board with Scapa Flow, a large and picturesque inland sea, now well known as a naval base, which lies between its south coasts and the encircling South Isles. The name Pomona, stamped on the Mainland by George Buchanan’s misapprehension of a Latin text, is never applied to the island by Orcadians; and here be it also said that Hoy and Walls, the largest of the South Isles and the second in size of the whole group (13½ miles long by about 5½ miles broad, and covering 36,674 acres), although one island geographically, is colloquially [7]two. The principal of the other South Isles are South Ronaldshay, 13,080 acres; Burray, 2682 acres; Flotta, 2661 acres; Graemsay, 1151 acres; and Fara, 840 acres. Scapa Flow is connected with the Pentland Firth to the south by Hoxa Sound, with the Atlantic to the west by Hoy Sound, and with the North Sea to the east by Holm Sound. The largest of the North Isles are Sanday, 16,498 acres; Westray, 13,096 acres; Rousay, 11,937 acres; Stronsay, 9839 acres; Eday, 7371 acres; Shapinsay, 7171 acres; Papa Westray, 2403 acres; North Ronaldshay, 2386 acres; and Egilsay, 1636 acres. This section of the archipelago is itself divided into two portions by the waterway formed by the Stronsay and Westray Firths, which runs from [8]south-east to north-west through the islands, and offers an alternative to the Pentland Firth or Sumburgh Roost passages for vessels passing between the North Sea and the Atlantic.

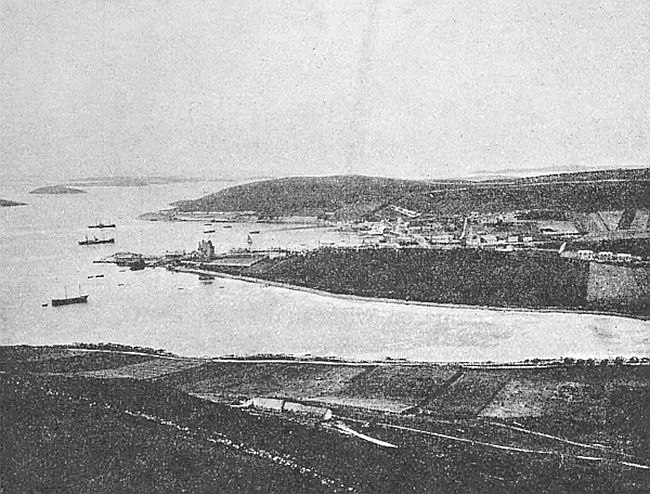

The Home Fleet in Scapa Flow

The whole archipelago includes some 67 islands, besides a score or more of islets, but only 30 are inhabited, and four or five of these are occupied solely by lighthouse attendants and their families. Small uninhabited islands, many of which are used as pasturage, are known as “holms.” The largest uninhabited island is the Calf of Eday, of 590 acres, but some 10 of the inhabited islands are of less area than this.

The streams of Orkney are, of course, mere burns of a few miles in length, draining the high ground, and save for the cheap motive power which they offer to farmers and millers, of interest only to anglers. Nowhere in Orkney are trees so much missed as along the burnsides, and for that reason the Burn of Berriedale, a branch of the larger Rackwick Burn, in Hoy, whose steep banks are covered with poplar, birch, hazel, and mountain ash, is a sort of Mecca to the aesthetic Orcadian. The broad estuary of the Loch of Stenness, which disembogues into the Bay of Ireland, though of trifling length, is the nearest approach to a river that the Islands can present. It is known as the Bush.

Loch of Kirbuster, in Orphir

From a spectacular point of view the many lakes of Orkney go far to compensate the county for the absence [9]of rivers. So many are they that it is hardly possible to get out of sight of salt or fresh water in the Islands. The great twin lochs of Harray and Stenness, at once joined and separated by the Bridge of Brogar, give a strong dash of picturesqueness to the whole central part of the West Mainland; and still more beautiful are the secluded and hill-surrounded Heldale Water and Hoglinns Water in Walls. Other lochs are Boardhouse, Swannay, Hundland, Isbister, Skaill, Banks, Sabiston, Clumly and Bosquoy in the West Mainland; Kirbuster in Orphir, Tankerness in the East Mainland; Muckle Water, Peerie (i.e. little) Water, and Wasbister in Rousay; St Tredwell Loch in Papa Westray; Saintear and Swartmill in Westray; Muckle Water in [10]Stronsay; and Bea, Longmay, and North Loch in Sanday. The total area of Orkney lakes is about 20,000 acres. In most of them fishing is free, in others permission to fish is readily obtainable. The Loch Stenness trout is, according to Gunther, a distinct species, but this is a vexed question among the learned in such matters. Heldale Water contains Norwegian char in addition to trout.

The geological formation of the Orkney Islands is, in its main features, of a very simple nature. If we except a comparatively small strip of land running northwestward from Stromness to Inganess in the West Mainland, and a still smaller patch in the neighbouring island of Graemsay, practically the whole county is underlain by the Old Red Sandstone formation. The two small areas above-mentioned—practically one, save for the intervening sea—are occupied by older crystalline rocks, consisting of fine-grained granite, and micaceous schist at times running into foliated granite, the whole traversed by veins of pink felsite. These formations are flanked on either side by a narrow band of conglomerate of the Middle Old Red Sandstone period, composed of the rounded pebbles of the underlying schist and granite. Of the Old Red Sandstone two divisions are found in the Islands—the Middle or Orcadian, and the Upper Old Red Sandstone. There are also in various parts but especially in Hoy and [11]Deerness, local outcrops of volcanic material. Orkney thus constitutes practically a continuation of the north-eastern Highlands of Scotland, and, as in Caithness, flagstone is by far the most widely distributed rock.

The Orcadian or Middle Old Red Sandstone is known to be a fresh water deposit, laid down by a large system of lakes which once extended over the north-eastern Highlands as far south as Inverness and Banff, and the same species of fossil fishes are found in the grey and black flagstones near Stromness as in the red sandstones on the south coasts of the Moray Firth. Leaving out of account the small area of crystalline rocks near Stromness, which are of age long anterior to any of the Old Red Sandstone deposits, the West Mainland parishes of Stromness, Sandwick, and Birsay contain the oldest rocks within the county, the Stromness flagstones with the fishes embedded in them being coeval with the Achanarras beds of Caithness. Next in point of age, come the flagstones of the East Mainland and the North Isles, corresponding in date and fossil remains to what are known to geologists as the Thurso Beds of Caithness. Following these in order of antiquity come the yellow and red sandstones and the dark red clays or marls which occur in the northern part of South Ronaldshay, and in Deerness, Shapinsay, and Eday. These are known as the John O’ Groats Beds, from their occurrence in that part of Caithness also, where indeed they were first exhaustively investigated. These three members of the Middle or Orcadian Old Red Sandstone are supposed to have a combined thickness of not less [12]than 7000 feet, though this pile of sediment represents only the upper half of the formation, the lower beds of Caithness apparently not being represented north of the Pentland Firth.

Berry Head, Hoy

After the Middle Old Red Sandstone had stood for many ages as dry land, the eroding action of the atmosphere, rain, and streams gradually eliminated all inequalities and produced a nearly level surface, upon which by degrees a new lake was formed, occupying a large part of Orkney and Caithness. In this lake sand accumulated, which now forms the highest hills of Orkney. The yellow sandstones of the Hoy and Walls hills are deposits of this lake, and belong to the Upper Old Red Sandstone, which is not represented in the [13]other islands of the archipelago, but reappears at Dunnet Head on the south side of the Pentland Firth.

Flagstone is a material that yields readily to the influence of the weather, and the subsoil formed is a rubble consisting of loose fragments of rock embedded in a brown clay formed by the softer and more weathered portion of the underlying rock. This gives a well-drained soil, and as the flagstones always contain lime, potash, and phosphates, and are frequently mixed with sand, the resultant soil may be generally described as a clayey loam of moderate fertility. Soil of this character covers a large part of the flagstone formation of Orkney, especially where the land is of moderate elevation, and surface accumulations of boulder-clay, or alluvium are at a minimum. At higher elevations on the other hand the character of the flagstone soils is frequently modified by the presence of peat. The soils of the sandstone formation, which occur in parts of South Ronaldshay and Hoy, and to a larger extent in Burray and Eday, are of inferior fertility, partly on account of their more porous nature. In Burray and Eday a large portion of the sandstone districts are in consequence left uncultivated, and utilised only as rough pasture. The same is true of the soils of the Upper Old Red Sandstone formation, which covers by far the larger portion of the parishes of Hoy and Walls, but most of this land is, in any case, above the altitude to which cultivation is usually carried in Orkney.

Of “drifts,” or loose surface deposits, the boulder-clay is the only one that materially affects the agricultural [14]quality of the soils of the Islands as a whole. The boulder-clay of Orkney, which on account of the particular direction—northwestwards over the Islands from the North Sea—taken by the ice at the period when the archipelago was subjected to glaciation, contains a considerable additional quantity of lime in the form of shells scraped up from the bed of the ocean, overlies the rock formations in the lower grounds over a large portion of the county. This deposit, which varies in thickness from less than a foot up to forty feet or more, has been calculated to occupy at least one-third of the area of the Islands, and it provides the most fertile soil that the county contains, particularly where the land has been improved by long cultivation and artificial drainage.

The outstanding features of Orcadian zoology are naturally the very restricted number of land mammals as compared with that of the neighbouring mainland of Scotland, the relatively large number of cetaceans in the surrounding waters, and, above all, the richness of the avifauna, particularly in sea-birds, and autumn and winter visitants from more northerly climes.

Although the bones and antlers of the red deer have been found among the matter excavated from the sites of brochs and Picts’ houses, and their shed horns at times turn up among the peat-mosses of the Mainland, that king of British Cervidæ was unknown to Orkney [15]during historic times until about the year 1860, when two young hinds and a young stag were introduced into Walls. There they throve perfectly, and had increased to thirteen or fourteen by 1870-72, when the proprietor of the island found it necessary to kill them off, on account of the damage which they were doing to crops. Tusks of the wild boar have been found at Skaill in the West Mainland, but the wolf, fox, badger, and in fact practically all of the larger land mammals known to Britain during historic times, or still found there to-day, have been totally unknown in Orkney during the same period. The otter is a notable exception, as it is very abundant in most of the islands, the great extent of sea-board giving it special facilities for concealment and avoidance of capture. An Orcadian proprietor who died a few years ago has recorded that in his young days he often had as many as thirty otter skins in his possession at one time.

The common hare appears to have been introduced into Orkney by a Mr Moodie of Melsetter, early in the eighteenth century, but both that attempt at acclimatisation and one by Malcolm Laing, the historian, in 1818, proved comparative failures. Better success, however, attended the efforts of Mr Samuel Laing and Mr Baikie of Tankerness about 1830, and at the present day, hares are found in the Mainland, Rousay, Eday, Shapinsay, Hoy, and South Ronaldshay. The white hare occurred in Hoy at an early date, as recorded by Jo Ben, a resident in Orkney, in his Descriptio Insularum Orchadiarum, in 1529:—“Albi lepores hic sunt, et capiuntur canibus.” [16]It died out, however, and has only recently been reintroduced. The rabbit is common throughout the Islands. Of other and less desirable rodents, the black rat was once general in South Ronaldshay, and probably still occurs there. The brown rats, common in most parts of Orkney, have been known at times to forsake certain islands altogether, taking to the sea in a body in search of a new home. The field mouse, and the house mouse are universal. The common field vole is plentiful in most of the islands, and there is a doubtful record of the water vole from Hoy. Microtus orcadensis, or the Orkney vole discovered in 1904, is a highly interesting species peculiar to Orkney and certain parts of Shetland. The common shrew has been found in Walls and Orphir, and the water shrew in Walls. Bats are rare in Orkney, but occurrences of vesperugo pipistrellus have been recorded from Walls, Sanday, and Kirkwall, of vespertilio murinus from Walls; while there is an interesting but doubtful record of a specimen of vesperugo noctula having been captured in South Ronaldshay.

Appearances of the walrus in Orkney waters have been recorded from Eday, Hoy Sound, and Walls at various dates from 1825 to 1864; and Orkney seals include phoca vitulina, which breeds on several islands and skerries, phoca groenlandica, and the grey seal. The occurrence of the hooded seal is doubtful. Among Cetacea, the Greenland and sperm whales are rare visitors, the hump-backed whale, still rarer; but the common rorquall, Sibbald’s rorquall, the lesser [17]rorquall, the beaked whale, the grampus, the common porpoise, and the white-sided dolphin are all fairly common. The bottlenose is, however, the Orkney whale, occurring at times in schools of 500 in number. The bottlenosed dolphin and the white-beaked dolphin are also on record.

The ornithology of Orkney comprises about 235 species, and owing to the special physical characteristics of the Islands bird-life forms a more conspicuous feature of landscape and sea than it does perhaps anywhere else in the British Islands. In a district where travel is more usual on sea than on land, and where the lakes, the fields, the hills, and the moors are unshrouded by woods, not only are aquatic birds a more constant object of the view than in districts otherwise conditioned, but the commoner land birds also are more frequently and readily observed.

The Great Auk

(Alea Impennis)

Crannie in which last Great Auk lived

Of the Falconidæ 17 species have been killed or observed in the Islands, being practically all of this family known to Britain, except the orange-legged falcon and the bee hawk. The golden eagle and the white-tailed eagle, however, both of which formerly bred in Hoy, are now only occasional visitants. The peregrine falcon is still fairly common, and in old days the King’s falconer procured them from the Islands for sporting purposes. Of the Strigidæ, the long-eared owl, the short-eared owl, the snowy owl, the tawny owl, Tengmalm’s owl, and the eagle owl have all been observed; but recorded occurrences of the barn owl and the little owl are of doubtful authenticity. Of the [18]order Anseres, of which some 32 species have been observed in the Islands, the rarest locally are perhaps the greylag goose, the pink-footed goose, the Canada goose, the gadwall, the shoveller, the Garganey teal, the king eider, the harlequin duck, the common scoter, the surf scoter, Bewick’s swan, and the goosander. The common eider duck is plentiful. Regular winter visitants, but not unknown at other seasons, are the [19]long-tailed duck, the velvet scoter, and the smew. Other visitants are the bernacle goose, the brent goose, the white-fronted goose, and the hooper, the last two in particular being common frequenters of the larger [20]lochs, such as Stenness, Harray, and Boardhouse at this season. Of some 18 species of the Laridæ found in Orkney, the rarest are perhaps the Iceland gull, the glaucous gull, the common skua, the pomatorhine skua, and Richardson’s skua, the last-named, however, breeding in Walls. Of the Colymbidæ, the red-throated diver breeds in Walls, while the black-throated and great northern divers are winter visitants, both suspected to have occasionally stayed to breed. Of the Alcidae, the razor-bill, common guillemot, black guillemot, puffin, and little auk are usual. In the crevice of a cliff in Papa Westray lived the last Orkney great auk, alca impennis, shot in 1813, and now in the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, an interesting specimen of a bird probably now everywhere extinct. Of the Scolopacidae about 22 species are on record. Yarrell is perhaps in error when he mentions the avocet as having been found in the Islands, but the red-necked phalarope was first recorded as a British species from Stronsay in 1769. The gray phalarope is rare. The woodcock comes in winter, and has bred in Rousay. The common snipe is plentiful, and the jack snipe and double snipe come in autumn. The little stint, purple sandpiper, sanderling, knot, ruff, bartailed godwit, black-tailed godwit, spotted redshank, and the greenshank are all found, but some of these are rare. Of the Charadriidae, the golden, grey, and ringed plovers, the lapwing, dotterel, and turnstone are common, while the eastern golden plover has been found. Of the order Tubinares, the stormy petrel and the Manx [21]shearwater breed, and the fulmar petrel has become a common visitant of recent years. The Rallidae are represented by the land-rail, water-rail, spotted crake, moor-hen, and common coot, and the Gruidae by the common and demoiselle cranes. The common heron alone is usual among the Herodii, although the bittern, little bittern, white stork, spoonbill, and glossy ibis have all been found. Of the Podicipitidae, the Sclavonian, great-crested, eared, and little grebes are known, the last-named, however, being the only nester. Of the Pelicanidae, the solan goose breeds on the distant Stack, near Sule Skerry, and the shag and cormorant are common. Of the Columbidae the rock-dove is common, the ring-dove occasionally breeds in plantations, and the stock-dove and turtle-dove are seen at times. Of the order Passeres, the usual nesters include the song-thrush, blackbird, redbreast, wren, pied wagtail, rock pipit, linnet, twite, greenfinch, yellow bunting, skylark, and common starling, the last a bird perhaps more frequent in the Islands than anywhere else. Scarcer breeders are the missel-thrush, stonechat, ring-ouzel, golden-crested wren, sedge warbler, grey wagtail, yellow wagtail, hedge-sparrow, meadow pipit, pied flycatcher, swallow, sand-martin, chaffinch, lesser redpole, and reed bunting. Common winter visitants are the redwing, fieldfare, and snow bunting, while rarer or only occasional comers are the dipper, redstart, blackcap, chiffchaff, fire-crested wren, willow wren, great titmouse, blue titmouse, common creeper, grey-headed wagtail, tree pipit, great grey shrike, red-backed shrike. [22]waxwing, spotted flycatcher, rose pastor, goldfinch, brambling, mealy redpole, common bullfinch, common crossbill, and wood lark. Orkney Corvidae include the grey crow, the rook, the jackdaw (South Ronaldshay only), and the raven as breeding species, while the magpie and nutcracker are rare visitants. Of the Picidae, the great spotted woodpecker is an irregular autumn and winter visitant, while the lesser spotted woodpecker, the green woodpecker, and the wryneck are seen at times. Of the order Coccyges, the cuckoo is fairly common, while the roller, hoopoe, and common kingfisher have been found. Of the order Macrochires the common swift and the common nightjar are occasionally seen.

Of game and other sport-yielding birds, the red grouse breeds in the Mainland, Rousay, Eday, Hoy, Walls, Flotta and Fara. Grouse disease is unknown in Orkney, and the birds of Walls and Rousay are the heaviest in Scotland. Various attempts to acclimatise the black grouse, partridge, red-legged partridge, and pheasant have all practically failed. The ptarmigan bred in Hoy until 1831. Pallas’s sand grouse at times visit the Islands in considerable numbers, and are surmised to have bred in several islands. The quail comes in much the same way, if in fewer numbers, and has nested, though rarely.

The plant-life of the Islands, however interesting to the scientifically-equipped botanist, presents no such happy hunting-ground to the unsophisticated lover of wild nature as does their bird-life. The practical [23]non-existence of woods conspires with the cool summer and high winds of the country to restrict both the number and the distribution of its flora. Ferns in particular are of circumscribed distribution, a loss to the beauty of the country-side only less conspicuous than that caused by the absence of woods; while several other popular and showy plants, such as the wild rose, the foxglove, gorse, and broom are of only too limited a range. Some 20 species or varieties of ferns are known or reported, of which ophioglossum vulgatum, var. ambiguum, was for years unknown out of the Islands. Zannichellia polycarpa, a pond-weed, was for some time known as a British plant only from the Loch of Kirbuster in Orphir; and Carex fulva, a sedge, was at one period peculiar to the same parish. More interesting, however, is the recent discovery by Mr Magnus Spence, who has lately published the first complete Flora orcadensis, of a plant which Mr C. E. Moss, D. Sc., of Cambridge, considers to be either a new variety of the dainty Primula scotica, or Primula stricta, a species hitherto unknown to the flora of the British Isles. The common variety of Primula scotica is fairly abundant in many of the islands. Hoy is the most interesting of the islands from a botanical point of view, as it contains a variety of plants unknown to the others. Perhaps the most interesting of these is Loiseleuria procumbens, the trailing azalea, which makes a beautiful show in its season on several spots among the higher hills. This island also contains in several of its more sheltered glens practically the only [24]indigenous trees that Orkney can boast of, consisting of somewhat stunted specimens of hazel, birch, mountain ash, quaking poplar, and honeysuckle. Before the days of the Baltic timber trade the dying Orcadian must have been gravely concerned over the disposition of the family porridge-stick, or “pot-tree,” as it was locally styled. Even to-day, with some plantations around certain mansion-houses, it is doubtful whether all the trees in the county, indigenous and introduced, would cover a sixty-acre field. We subjoin a list of a few of the rarer Orkney plants, with some of their localities.

| Thalictrum Alpinum | Hills of Hoy, Orphir, Rousay. |

| Thalictrum Dunense | Links, in Walls, Deerness, Sanday. |

| Ranunculus Sceleratus | Stromness. |

| Nasturtium Palustre | North Ronaldshay. |

| Sisymbrium Thalianum | Kirkwall, Hoy. |

| Sisymbrium Officinale | Hoy. |

| Draba Incana | Hoy Hill; Fitty Hill, Westray. |

| Silene Acaulis | Hoy Hill; Fitty Hill, Westray. |

| Spergularia Marginata | The Ayre, Walls; Vaval, Westray. |

| Geranium Robertianum | Carness, St Ola. |

| Fragaria Vesca | Rousay. |

| Rubus Fissus | Hoy. |

| Dryas Ocopetala | Hoy Hill; Kame of Hoy. |

| Rosa Glauca, var. crepiniana | Stromness. |

| Circæa Alpina | Hoy, Orphir, Evie. |

| Sedum Acre | Links, Hoxa, S. Ronaldshay. |

| Saxifraga Oppositifolia | Hoy Hills. |

| Saxifraga Stellaris | Rackwick, Hoy; Kame of Hoy. |

| Pimpinella Saxifraga | St Ola. |

| Sium Erectum | Holm, Sanday. |

| Hedera Helix | Berriedale, Hoy; Berstane, St Ola. |

| Cornus Suecica | Kame of Hoy. |

| Gallium Mollugo, var. Bakeri | Deerness, Westray. |

| Hieracium Orcadense | Cliffs in Hoy. |

| Hieracium Scoticum | Cliffs in Orphir. |

| Hieracium Strictum | Pegal Bay, Walls. |

| Hieracium Auratum | Cliffs, Pegal Bay, etc. |

| Lobellia Dortmanna | Walls, Rousay. |

| Jasione Montana | Eday, N. Ronaldshay. |

| Arctostophylos Uva-Ursi | Hills, Hoy and Walls. |

| Pyrola Rotundifolia | Hoy, Rousay. |

| Vaccinium Vitis-Idæa | Walls, Hoy, Orphir, Rousay. |

| Vaccinium Uliginosum | Walls, Hoy, Birsay. |

| Gentiana Baltica | North Ronaldshay, Birsay. |

| Ajuga Pyramidalis | Berriedale and Rackwick, Hoy. |

| Myosotis Palustris | Orphir, St Andrews. |

| Oxyria Reniformis | Hoy. |

| Myrica Gale | Birsay. |

| Salix Nigricans | Orphir. |

| Juniperus Nana | Hoy. |

| Typha Latifolia | Loch of Aikerness, Evie. |

| Sparganium Affine | Mainland, Hoy, Rousay. |

| Ruppia Spiralis | Loch of Stenness. |

| Ruppia Rostellata, var. Nana | Oyce of Firth. |

| Goodyera Repens | Stromness, Harray. |

| Scirpus Tabernæmontani | St Ola, Holm. |

| Blysmus Rufus | Orphir, St Andrews, Westray. |

| Carex Muricata | Firth. |

The total number of plants found in the Islands, not counting varieties, is about 560, a number slightly in excess of that of Shetland and slightly fewer than that of Caithness, to the floras of which counties that of Orkney closely assimilates.

In a district where, despite the general existence of good roads, the shortest cut to church, post office, smithy, or mill is often by crossing a sound or skirting the shore in a yawl, the coastline spells something more than a mere alternation of cliffs and sandy beaches, diversified by the occasional appearance of a lighthouse or a harbour. Such things of course the shores of Orkney exhibit in no common measure, but to show how far they are from exhausting the coastal features of Orcadian life and scenery, it is only necessary to say that of twenty-one civil parishes in the county all but one (Harray) possess miles of sea-board, and that of the centres of population, only some two or three hamlets are inland. No spot in the Mainland is above five miles from the coast, no point in any other island more than three miles.

The general configuration of the coasts may be best studied on the map, but as not every inlet of the sea forms a good natural anchorage, we here indicate some that do so. Others, and some of these the most important, are mentioned in the final section. Widewall Bay on the W. side of South Ronaldshay, Panhope in Flotta, and Echnaloch on the N.W. of Burray are, after the far-famed Longhope in Walls, the best anchorages in the South Isles. The Bay of Ireland, known to mariners as Cairston Roads, is on the south coast of Mainland, a little to the eastward of Stromness. In[27]ganess Bay and Deer Sound are in the N.E. of Mainland; Veantrow Bay on the N. side of Shapinsay; St Catherine’s Bay, Mill Bay, and Holland Bay in Stronsay; and Otterswick in Sanday. There are deepwater piers—as indispensable adjuncts of traffic in Orkney as railway stations are elsewhere—at Longhope, St Margaret’s Hope, and Burray in the South Isles; at Stromness, Swanbister Bay, Scapa Bay, and Holm on the S. coast of Mainland; at Kirkwall and Finstown on the N. coast of Mainland; and in Shapinsay, Stronsay, Eday, Rousay, Sanday Westray, Egilsay, and North Ronaldshay in the North Isles.

The Old Man of Hoy

(The tallest “Stack” in British Isles, 450 ft. high)

Lying as they do athwart a main trade route from the ports of northern and western Europe to America and the western ports of Britain, the rock-girded and wind-swept shores of Orkney are especially well lighted. Indeed it is probable that from the summit of the Ward Hill of Hoy on a clear night more lighthouses can be discerned than from any other point in Britain. Stromness is an important centre of operations for the Scottish Lighthouse Board, lying half-way between the east and west coasts of Scotland, and having the many lighthouses of Shetland to the north.

The coasts and sounds of Orkney are studded with innumerable skerries and sunken reefs. Few of these call for any special notice, but the reader should know that in a few cases—Auskerry, the larger Pentland Skerry, Sule Skerry—the name skerry is locally applied to soil-covered islets of considerable area. There are no raised beaches in Orkney, all oceanological and geological data going to show that the islands were once united, and the coastline in consequence at a lower level than it occupies to-day. Traces of submerged forests are to be found at Widewall Bay, in South Ronaldshay, and a few other localities. Coast erosion in the Islands is too slight a factor to have any practical significance.

Apart from the fine natural harbours, the outstanding physical feature of the Orkney coasts is the gigantic cliff scenery of the Atlantic sea-board, particularly that of Hoy and Walls, which both for loftiness and splendour of colouring stands unrivalled in Britain.

For a distance of about two miles from the Kaim of Hoy southwards to the Sow the average height of the cliffs is above 1000 feet, the huge rampant culminating about midway between these two points in St John’s Head, also called Braeborough, which attains a height of 1140 feet. About a mile southward of the Sow stands the famous Old Man of Hoy (450 feet), tallest of British “stacks”—

Of many other fine cliffs in this island we have space to mention only the Berry, in Walls, a sheer precipice of 600 feet in height, which forms, so to speak, one of the jaws of the Pentland Firth, the other jaw being Dunnet Head on the Caithness side. For beauty of colouring and indeed of outline, the Berry excels any cliff in this wonderful coastline, which the late Dr Guthrie described as, after Niagara and the Alps, the most sublime sight in the world. There is much fine rock scenery elsewhere in the Islands, particularly in the West Mainland, Rousay, Eday, and South Ronaldshay.

The tideways in many of the sounds which separate the various islands are remarkable for their turbulence and velocity, a speed of 8 knots an hour being reached in Hoy Sound, and 12 knots in the Pentland Firth. In the Pentland Firth also are two whirlpools, the Wells of Swona and the Swelkie of Stroma, the latter as famous in fable as the by no means more formidable [30]Maelström. The total coastline of the Islands extends to between 500 and 600 miles.

Insular climates are almost invariably milder than those of continents, or even those of the inland regions of large islands, in the same latitudes, and the climate of Orkney is no exception to this rule. Like so many other things Orcadian, the climate is conditioned by the proximity of the sea, and in this case by a sea whose waters are considerably warmer than their latitude might lead one to suspect. The warm surface drift of the North Atlantic is of itself sufficient to explain the relatively mild winter of Orkney, and the presence of the widest portion of the North Sea on the eastern side of the Islands has also a modifying influence. It must also be borne in mind that in cool climates rain brings heat. Our westerly and south-westerly winds, passing over sun-bathed seas, collect in their courses the vapour of warmer climates, and when this vapour, coming into contact with the cooler air of more northerly latitudes, is again condensed into water, a certain amount of the heat thus collected is set free, and raises the temperature of the air, of the rain itself, and of the land on which it falls.

Tabular Statement of Orkney Weather.

| Mean Temperature. | Mean Hours Sunshine. | Mean Rainfall. | ||

| Years 1871-1905. | 1880-1907. | 1841-1907. | ||

| January | 39.0° | 29.7 | 3.72´´ | |

| February | 38.5 | 55.5 | 3.05 | |

| March | 39.3 | 101.1 | 2.82 | |

| April | 42.4 | 154.1 | 1.99 | |

| May | 46.4 | 178.5 | 1.81 | |

| June | 51.3 | 160.9 | 1.97 | |

| July | 54.2 | 141.3 | 2.57 | |

| August | 54.0 | 121.8 | 3.01 | |

| September | 51.5 | 108.8 | 3.09 | |

| October | 46.4 | 75.5 | 4.43 | |

| November | 42.4 | 36.5 | 3.97 | |

| December | 39.9 | 20.8 | 4.21 | |

| —— | —— | —— | ||

| Mean | 45.4 | Total 1184.5 | Total 36.65 | |

It will thus be seen that the mean annual temperature of Orkney is 45.4°, which compares with 46.3° at Aberdeen and at Alnwick in Northumberland, and with 49.4° at Kew Observatory. The total range of temperature is only about 16°, as against 20° at Thurso, just across the Pentland Firth, 22° at Leith, and 25° at London. In this respect the Islands resemble the S.W. coast of England and the W. coast of Ireland. The lowest temperature recorded in Orkney in the eighty-seven years during which meteorological observations have [32]been made was 8°, which occurred on 18th January 1881, the highest was 76°, on 16th July 1876. The temperature of the ocean varies only about 13° during the year, from 41.6° in February, to 54.5° in August. The mean annual rainfall of about 37 inches compares with over 80 inches in many parts of the West Highlands, and with 23 inches at Cromarty, the driest station in Scotland. The wettest months are October, November, and December, during which the Islands receive from one-third to one-half of their annual rainfall, the driest months are April, May, and June, which together receive only one-eighth of the total fall. Thus Orkney is practically never troubled [33]with excessive rainfall, and serious droughts are equally unknown. The mean annual sunshine of 1185 hours compares favourably with 1164 hours at Edinburgh. London enjoys 1260 hours, Hastings 1780. Orkney’s brightest month is May, with an average of 178 hours of sunshine, the gloomiest is December with 20.6 hours.

Old Melsetter House, in Walls

(In a specially mild winter climate)

Apart from the fact that Orkney enjoys the mildest winter of any Scottish county, the chief difference between the weather of the archipelago and that of Scotland in general is perhaps the greater prevalence of high winds in the Islands, which owing to the general lowness of the land receive the full force of the North Atlantic gales, and which moreover lie in the most common track of the Atlantic cyclones, a circumstance which leads to great variability of wind and weather. Orkney has record of only one hurricane, on 17th November, 1893, with a velocity of 96 miles. Several winter gales of over 80 miles have been recorded, and one summer gale of 75 miles in the year 1890. During the fifteen years 1890-1904, 300 gales were recorded in Orkney, practically the same as at Fleetwood in Lancashire, while Alnwick experienced only 157, and Valentia on the west coast of Ireland only 130. Atlantic cyclones are the dominating factor in Orkney weather during the greater portion of the year, producing gales of greater or smaller magnitude, and being almost invariably accompanied by rain, with sudden changes both in the direction and the force of the wind. In the spring season, however, anticyclones frequently cause [34]spells of dry, cold weather, with fairly steady winds from the eastward or northward.

Winter in Orkney is in general a steady series of high winds, heavy rains, and ever varying storms, with much less frequent falls of snow, and fewer severe or continuous frosts than elsewhere in Scotland. Under the shelter of garden walls we have seen strawberry plants in blossom at Christmas and roses in January, while chance primroses may be found in sheltered nooks in any month of the year. The spring is cold and late, but the prevailing winds from N.W., N.E., or E. have not the piercing coldness so often felt in the spring winds along the east coast of Scotland. The summer is short, but remarkable for rapidity of growth. Fogs are fairly common during summer and early autumn, and come on and disperse with exceptional suddenness. Thunder in Orkney occurs mostly in winter, during high winds and continuous falls of rain or snow. The heaviest rains and the most prevalent and strongest winds are from the S.W. and S.E.

Means of Observation in Orkney For Thirty-three Years—1873-1905

| Rainy | Snowy | Days on | Thunder | Clear | |||

| days. | days. | which | storms. | sky. | Overcast. | Gales. | |

| Hail fell. | |||||||

| 219 | 31 | 14 | 6 | 31 | 156 | 79 |

It is unsafe to dogmatise on the early races of Orkney; but from the undoubted community in blood, speech, and culture with other northern counties of Scotland during the Celtic period, we may fairly conjecture that the Islands must have similarly shared in whatever pre-Celtic population—Iberian or other—these regions as a whole possessed.

Into the vexed question whether any remnant of Celtic population survived the Norse settlement of the Islands in the ninth century we cannot enter here. It is certain that for centuries after that era Norse speech, law, and custom were as universal and supreme in Orkney as ever Anglo-Saxon speech and institutions were in Kent or Norfolk. The place-names of the Islands are, save for a late Scottish and English element, entirely Norse.

The Scottish immigration into Orkney, which commenced about 1230, came for centuries almost exclusively from the Lowlands—the Lothians, Fife, Forfarshire, and those parts of Stirlingshire, Perthshire, Aberdeenshire, Banffshire, and Moray which lie outside the “Highland Line,” being the chief areas drawn from. A later and much slighter strain of immigration from Caithness, Sutherland, and Ross, which affected the South Isles more especially, was itself quite as much of Norse as of Celtic ancestry. The people of Orkney [36]must therefore be put down as in the main an amalgam of Norse and Lowland Scots.

There never was any very rigid line of division between these two races in the Islands. So much is it the case that, while the Norse were being Scotticised in speech and custom, the incomers were at the same time being Orcadianised in sentiment, that the opprobrious epithet of “Ferry-loupers,” hurled by native Orcadians at successive generations of Scots intruders, is itself of Scottish origin. The genius loci was a very potent spirit, and the Scoto-Orcadian was often prouder of being an Orcadian than of being a Scot.

The humblest Orcadians have for centuries past spoken English more correctly and naturally than was at all common among the Scottish lower orders before the advent of board school education, a circumstance largely due to the fact that a great portion of the population exchanged Norse speech for Scots about the period—the later sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries—when educated Scots were themselves adopting English. Add to this the constant presence of passing English vessels and the presence of Cromwell’s soldiers. At the same time a modified Scots dialect is commonly spoken by the less educated classes, but even in this the admixture of pure English is pronounced. A few Norse words, mostly nouns, survive imbedded in the local speech, whether English or Scots. Norse speech lingered in Harray until about 1750.

The population of Orkney, which numbered 24,445 in the year 1801, increased almost uninterruptedly to [37]a maximum of 32,395 in 1861. Every subsequent census, except that of 1881, has shown a decrease, and the 9.8 per cent. rate of intercensal decline recorded in 1911 was the heaviest revealed by the census of that year for any Scottish county. The population in that year was 25,897, being 69 to the square mile.

Under modern conditions Orkneymen have resumed the roving instincts of their Norse ancestors, and the variety of capacities under which the sons and daughters of the Islands live in the far corners of the earth is astonishing. The ostensible local causes of this movement are in reality of secondary importance. The real causes are improved education, improved communications, and the grit to take advantage of them. Can any Scottish or English county show the equivalent of The Orkney and Shetland American, a little newspaper published for years in Chicago? “A Shields Shetlander,” too, is a current descriptive tag which might well be supplemented by “A Leith Orcadian.”

Farming is the very life of Orkney, giving full or partial employment to no less than 6400 of the population. The great era of agriculture in the Islands followed, and was partly the consequence of the failure of the local kelp industry in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The area under crop and permanent pasture rose from about 30,000 acres in 1855 to 86,949 acres in 1870. It is now 107,941 acres, while in addition [38]at least 52,941 acres of heath and mountain land are utilised for grazing. The chief crops are oats, 33,153 acres; turnips, 13,877 acres; and hay, 9425 acres. Stock rearing is the cornerstone of Orcadian farming.

Harvesting at Stenness

Short-horns and polled Angus are the favoured breeds of cattle, and many thousand head from the Islands pass through the Aberdeen auction marts every year. The finest of the beef—and prime Orkney beef is second to none—finally reaches Smithfield. Cheviots and Cheviot-Leicester crosses are the common sheep, the small native breed, of Norwegian origin, being now confined to North Ronaldshay. The old Orkney horse, itself probably a hybrid of half Norwegian and half Scottish extraction, has for several generations past [39]been crossed with Clydesdale blood, and the resultant is a small-sized but very sturdy and serviceable animal. Oxen are still used to a small extent as draught animals. The export of eggs and poultry is a great and growing Orcadian industry, the annual output from the Islands being at least £60,000 in value, a larger figure be it noted than the purely agricultural rental of the county. The fattening of geese for the Christmas market is a special feature of Orkney poultry-farming, the birds being largely brought from Shetland at the end of harvest and put on the stubble. The open winter is a valuable consideration to poultry-keepers in the Islands, increasing the amount of natural food which the birds are able to pick up, and extending the period of laying.

Large quantities of sea-weed are available as manure in practically every part of the Islands, and marl in some localities. The chief disadvantages under which agriculture labours in Orkney are distance from the markets, and occasional damage to grain crops from sea-gust. Agricultural co-operative societies, however, which have obtained a firm footing in the Islands, are doing a great deal to counter-act the effects of the first-mentioned drawback.

The manufacture of kelp was introduced into the Islands in 1722, and by 1826 the annual export amounted to 3500 tons, valued at £24,500. The abolition of the [40]duty on barilla, which is largely used in the manufacture of glass, destroyed this industry for a time; but since about 1880 there has been a considerable revival in the North Isles, the yearly export having again reached about 1500 tons. Orkney kelp is considered of the finest quality.

Orkney Yawl Boats

The making of linen yarn and cloth, introduced in 1747, was successfully carried on for many years, and flax was locally grown. This industry received a severe check during the Great War (1793-1815), and gradually disappeared.

The manufacture of straw-plait for bonnets and hats was begun about 1800, and fifteen years later the yearly export was valued at £20,000, from 6000 to 7000 women being employed in the industry. The material used was at first split ripened wheat straw; later, however, [41]unripened, unsplit, boiled and bleached rye-straw was substituted. The reduction of the import duty on straw-plait finally destroyed this interesting home industry, of which Kirkwall and Stromness were the chief centres.

The present-day industries of Orkney are unimportant. No minerals are worked in the county, although flagstone is quarried at Clestrain in Orphir, and red sandstone of fine quality at Fersness in Eday. The numerous sailing boats used in the Islands are mostly of home construction, the broad-beamed, shallow-draught, and comparatively light Orkney yawl being a type specially designed to suit local conditions of weather and tide. The making of the well-known Orkney straw-backed chairs is restricted by a very limited demand, and the specimens made for sale are somewhat more elaborate than those used in the cottages. A small quantity of home-spun tweed is made in the Islands, and a certain amount of rough knitting—stockings, mittens, and other articles used by the seafaring classes—is done in some districts. Fish-curing is carried on at Kirkwall, and to a small extent, as a home industry, in country districts. There are distilleries at Stromness, Scapa, and Highland Park, near Kirkwall, the output at the last-named being large, and in high esteem among whisky-blenders.

Of recent years Whitehall in Stronsay has become one of the great centres of the summer herring fishing, [42]with an annual catch of from 80,000 to 90,000 crans, a total exceeded in Scotland only at the ports of Lerwick, Fraserburgh and Peterhead. As at many other places where this great industry is carried on, however, the boats, the capital, and the personnel come almost entirely from outside. There are smaller stations of this fishery at Kirkwall, Sanday, Stromness, Holm, and Burray, at the last-named of which alone the boats and crews are local.

The white fishing is carried on in a desultory fashion in Orkney waters by some 350 fishermen, who use small locally-made yawls, but the annual catch is not important compared with that of other fishery districts. Haddocks, cod, and saithe are the commonest fish. Saithe simply swarm, but are caught chiefly for household consumption. Some 250 other men who style themselves “crofter-fishermen” in the census returns, are in reality small farmers who do an occasional day’s fishing, mainly for the pot. Lobster fishing is the one branch of the industry which the “crofter-fishermen” do follow with any persistence, and lobsters and other shell-fish, mainly whelks, to the value of from £6000 to £7000, are exported from the Islands annually. The whelks are gathered mainly by women. There are 338 fishing boats in Orkney, of an aggregate burden of 2154 tons, and of a value, including fishing gear, of £16,095.

Sea-trout are plentiful along much of the Orkney coast, especially near estuaries; but although surreptitious netting is intermittently done by unauthorised [43]persons, this fishing is not, as with proper care it might be, on any sound commercial footing. Sea-trout run to a large size in the Islands, fish of from 8 to 10 lbs. being not uncommon. Walls, Hoy, the Bay of Ireland, Holm, and Rousay are the best localities. The net season is from 24th February to 10th September, the rod season from the same opening date to 31st October.

Longhope and the Bay of Firth were of old famous for oysters, and at the latter place a praiseworthy effort was recently made to restore the fishery.

Our knowledge of the Orkney Islands before the Norse settlement in the latter part of the ninth century is of a slight and fragmentary character. In particular, what Latin writers say gives no sure information, the references in poets like Juvenal and Claudian being manifestly for literary ornament.

The earliest writer of British race to throw any light on the Islands is Adamnan, who mentions that in the sixth century Cormac, a cleric of Iona, with certain companions, visited the Orkneys, and adds that the contemporary Pictish ruler of the Islands was a hostage in the hands of Brude Mac Meilcon, King of the Northern Picts. Whatever degree of power this Pictish king may have exercised over the Islands, we learn from the Annals of Ulster that in the year 580 they were invaded by Aidan, King of the Dalriadic Scots, and as the next mention of the Orkneys in the native chronicles is the [44]record of their devastation by the Pictish King Brude Mac Bile in the year 682, it is perhaps a fair inference that Dalriadic influence had predominated there during the intervening century. That the Islands were christianised about this period by clerics of the Columban or Irish Church, is a point too firmly established by archaeological, topographical, and other data to require any insistence on here. Many pre-Norse church dedications to St Columba, St Ninian, and other Celtic saints, tell their own story.

Little is known of the state of the Islands during two centuries preceding the date of the Norse settlement c. 872 A.D., but from that era until the year 1222 Orkney possesses in the Orkneyinga Saga a record of the highest value. The Saga states that the Islands were settled by the Norsemen in the days of Harald the Fair-haired (Harfagri), but had previously been a base for Vikings. Harald Harfagri had about the year 870 made himself sole King of Norway, and in so doing had incurred the odium of a large section of the Odallers, or landowners, many of whom in consequence emigrated to Iceland, Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, and the coasts of Ireland. The settlers in Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Islands took to piracy, and so inflicted the coasts of old Norway, that in 872 Harald followed up the fugitives, conquered all the islands of the Scottish seas, and placed his partisan Rognvald, Earl of Moeri, as hereditary Jarl over Orkney and Shetland. This nobleman, however, preferring to live in Norway, gifted his western jarldom to his brother Sigurd, who is com[45]monly considered the first, as he proved one of the greatest, of the long line of Orcadian Jarls. Sigurd speedily spread his power over northern Scotland as far south as Moray, and from his time until the close of the thirteenth century the Orkney Jarls had the controlling hand in Caithness, Sutherland, and Easter Ross. Jarl Sigurd died in 875, and was ultimately succeeded by the scarcely less strenuous Torf-Einar, a son of Jarl Rognvald, and a half-brother of Hrolf (Rollo), the conqueror of Normandy. Einar got his sobriquet of “Torf” from the fact of his having learned in Scotland, and taught the islanders, the practice of cutting turf for fuel. He was succeeded by three sons, of whom the two elder, Arnkell and Erlend, fell in the battle of Stanesmoor in England, in 950. The third, Thorfinn Hausacliuf (Skull-Splitter), proved as good as his name, and well maintained the doughty reputation of a family which later, in a collateral line, produced William the Conqueror.

Kirkwall

Let us pause here, however, to outline the polity and state of society which had now become established in the Islands. The Orkney Jarls were not autocratic rulers. The Odallers, assembled at the Thing, made the laws, on the advice or with the concurrence of the Jarls, but these laws were superimposed on a body of old Norse oral laws which the settlers had brought with them from over-sea. The land law taking no account of primogeniture, the sons of an Odaller succeeded equally to his estate, and a daughter could claim half the share of a son. The eldest son, however, could [46]claim possession of the Bu (English by, as in Whitby), or chief dwelling. An Odaller could not divest himself of his odal heritage, except for debt, or in security for a debt, and in such a case a right of redemption lay for all time, not only with his nearest heir, direct or collateral, but on refusal of nearer heirs to avail themselves of it, with any descendant whatsoever. Under such a system free men without landed interest actual or prospective were few, and the odal-born formed the bulk of the population. Some of the wealthier Odallers, however, possessed a limited number of thralls, and thraldom was hereditary. Land tax, or scat, was paid by the Odallers to the Jarl, and by the Jarl to the King, but in both cases the payment was [47]a fiscal imposition rather than a feudal exaction, the Crown of Norway recognising the obligation of defending the Islands against outside foes in final resort. Apart from this, the overlordship of the mother-country was so slight that in the European diplomacy of the times the Jarls were treated as sovereign princes.

Thorfinn Hausacliuf died c. 963; and the rule of his five sons, Havard, Hlodver, Ljot, Skuli, and Arnfinn is noticeable for the first of those family feuds which form so marked a feature of the history of the Jarls. Skuli took the title of Earl of Caithness from the King of Scots, and fared against Ljot with a host provided by the King and the Scots Earl Macbeth. Ljot defeated him in the Dales of Caithness, Skuli being slain. Earl Macbeth with a second host, was in turn defeated by Ljot at Skidmoor (Skitton) in Caithness, and here Ljot fell. His other brothers having already disappeared in domestic strife, Hlodver was now left sole. He married Edna, an Irish princess, and their only son Sigurd Hlodverson, the Stout, is one of the most famous characters of the Saga. Succeeding his father in 980, Sigurd held Caithness by main force against the Scots. A Scots maormor, Finnleik, the father of the celebrated Macbeth, having challenged him to a pitched battle at Skidmoor by a fixed day, Sigurd took counsel of his mother, for she, as the Saga says, “knew many things,” that is, by witchcraft. Edna made her son a banner “woven with mighty spells,” which would bring victory to those before whom it was borne, but death to the bearer. Armed with this uncanny device, Sigurd [48]defeated his challenger at Skidmoor, with the loss of three standard-bearers. An incident of wider consequence, however, befell Sigurd in the year 995. Olaf Tryggvi’s son, King of Norway, came on the Jarl aboard ship in a small bay in the South Isles. The King had the superior force, and, a recent convert himself, he there and then forced christianity upon the reluctant Jarl, and laid him under an obligation to impose the faith upon the people of Orkney. The Saga adds, “then all the Orkneys became christian,” and so indeed the Islands henceforth remained. Sigurd himself, however, reverted to the old gods, and in the year 1014, he joined the great Norse expedition against Brian, King of Ireland, which led to the battle of Clontarf. In that famous fight the Skidmoor banner again did service, but the spell was broken. “Hrafn the Red,” called out the Jarl after two standard-bearers had fallen, and an Icelander who knew its fatal secret had declined to touch it, “bear thou the banner.” “Bear thine own devil thyself,” rejoined Hrafn. Then the Earl said, “’Tis fittest that the beggar should bear the bag,” at the same time taking the banner from the staff and placing it under his cloak. A little after, the Earl was pierced through with a spear.

Most famous of all the Jarls in the eyes of the Norse was Thorfinn the Great, Sigurd’s son by a second marriage with a daughter of Malcolm II, King of Scots. Sigurd, however, was at first succeeded in Orkney by Brusi, Somerled, and Einar, sons of an earlier marriage, while Thorfinn, a boy of five, who had been fostered [49]by the Scots King, was invested by his grandfather in the Earldom of Caithness and Sutherland. On attaining manhood, however, Thorfinn made good his claim to a share of Orkney also, and after many vicissitudes of fighting and friendship with his half-brothers, and with Jarl Rognvald I, Brusi’s son, was finally left sole ruler there. He extended his power far and wide over northern Scotland, controlled the Hebrides, and ruled certain parts of Ireland. He even invaded England in the absence of King Hardicanute, and, according to the Saga, defeated in two pitched battles the forces that opposed him. In later life Thorfinn visited Rome, and he built a minster, known as Christchurch, in Birsay, the first seat of the Bishopric of Orkney. He died in 1064. Thorfinn’s sons Paul and Erlend succeeded, and two years later shared the defeat of their suzerain King Harald Sigurdson (Hardradi) at Stamford Bridge. Returning home by grace of Harold Godwinson, the Jarls ruled in peace for some years. As their sons grew up, however, Hakon, Paul’s son, quarrelled with his cousins Erling and Magnus (the future saint), Erlend’s sons, and matters grew so unquiet that in 1098 King Magnus Barelegs sent the two Jarls prisoners to Norway, and placed his own son Sigurd over the Jarldom. On the death of King Magnus in 1106, Sigurd returned to Norway to share the vacant throne with his brothers, and the overlords restored Hakon, Paul’s son, and Magnus, Erlend’s son, to the Jarldom. Quarrels were renewed, with the final result that in the year 1116 Magnus was murdered in the island of Egilsey, where the cousins had [50]met to discuss their differences, by the followers of Jarl Hakon, Hakon himself more than consenting. The fame of St Magnus soon spread over the whole Scandinavian world, and at an early date a church was dedicated to him even in London. Jarl Hakon, after the manner of the times, made an expiatory journey to Rome and the Holy Land, and thereafter ruled Orkney with great acceptance until his death in 1126. He was succeeded by his son Paul. While in Orkney in 1098, however, King Magnus Barelegs had married Gunnhilda, a daughter of Jarl Erlend, to a Norwegian gentleman named Kol. To their son Kali, Sigurd King of Norway now granted a half share of the Islands, with the title of Jarl, and from a fancied resemblance to Jarl Rognvald I, insisted on changing his name to Rognvald. The royal grant being strenuously opposed by Jarl Paul, Rognvald vowed that if he succeeded in making good his claim, he would erect a stone minster at Kirkwall, and dedicate it to his sainted uncle, Jarl Magnus. After many vicissitudes by sea and land, Rognvald finally proved successful, and how he fulfilled his vow the Cathedral Church of St Magnus still shows. St Rognvald—for in 1192 he too was canonised—was at once the most genial and the most accomplished of the Jarls, and one of the great characters of the Orkney Saga. He made a famous voyage to Palestine (1152-1155), fighting, love-making, and poetising by the way. Incidental to his great struggle for power with St Rognvald, Jarl Paul had in 1137 been seized by the famous viking Swein Asleifson [51]and carried off to Athole, where he was placed in the hands of Maddad, Earl of Athole, who had married his half-sister Margaret. The whole affair is shrouded by mystery, but Countess Margaret appears to have intrigued both with her brother and with Jarl Rognvald to have her son Harald, a boy of three, conjoined with Rognvald in the Jarldom. In the sequel Jarl Paul mysteriously disappears, murdered, according to one account, at the instigation of the Countess; and in 1139 Jarl Rognvald accepted the young Harald Maddadson as his partner. With occasional intervals of friction this somewhat oddly assorted pair ruled together [52]until 1159, when the checkered career of the genial and many-sided St Rognvald was closed by his assassination in a personal quarrel in Caithness. Thereafter Harald ruled the Islands alone until his death in 1206. A powerful and overbearing man, he quarrelled with John, Bishop of Caithness, blinded the prelate and caused his tongue to be cut out; barbarities which brought King William the Lyon to the borders of Caithness with an army (1202). Harald bought off the King, and on the whole maintained his own in Caithness, although all the circumstances of the times show that a now feudalised Scotland is becoming increasingly able to reassert its authority in these northern parts. Harald got into difficulties with his Norwegian suzerain, King Sverrir, who deprived him of Shetland, which was not again conjoined with Orkney until two centuries later. Harald was succeeded by two sons, David and John, the former of whom died in 1214. Jarl John, like his father, came into conflict with the Church and with Scotland. Adam, Bishop of Caithness, successor to the mutilated Bishop John, having proved too exacting in the collection of Church dues, the laity appealed to the Jarl, who, however, declined to intervene. Whereupon the outraged laymen burnt the Bishop in a house into which they had thrust him. King Alexander II, came with an army, and not only heavily fined the Jarl, but also had the hands and feet hewn off eighty men who had been present at the Bishop’s death. Jarl John was slain in a brawl at Thurso in 1231, and, as he left no son, the line of the Norse Jarls of Orkney ended.

St Magnus’ Cathedral, Kirkwall, from South-East

Tankerness House and St Magnus’ Cathedral

King Alexander II of Scotland granted the Earldom of Caithness, now finally disjoined from Sutherland, to Magnus, second son of Gilbride Earl of Angus, whose wife was a daughter or sister of the late Jarl, and Magnus was also recognised as Earl of Orkney by the King of Norway. The old Jarls had been Norse nobles who held the northern shires of Scotland more or less in defiance of the Scottish Crown, the future Earls of Orkney are great Scottish nobles holding a fief of the Crown of Norway. In consequence, an influx of Scots into the Islands now commenced, which, accelerated by their cession to Scotland in 1468, in the end was the means of transforming the Orcadians into a British community. The history of this Scoto-Norse period is obscure, the Icelandic records largely failing us, but the law of primogeniture being now tacitly applied to the succession, Earl Magnus was followed by two Earls of the name of Gilbride, and the second Gilbride by another Magnus. The latter is mentioned in the Saga of King Hakon Hakonson, of Largs fame, as having accompanied the King on that expedition, after which the monarch came back to Orkney with his storm-shattered fleet, and died in the Bishop’s palace at Kirkwall on 15th December, 1263. By the treaty of Perth in 1266 Hakon’s successor, Magnus the Seventh, ceded to the Scottish Crown all the islands of the Scottish seas, except the Orkneys and Shetland, for an annual payment of 100 merks, to be paid into the hands of the Bishop of Orkney, within the church of St Magnus. Earl Magnus died in 1273, and was suc[54]cessively followed by his sons Magnus and John, the latter of whom, as Earl of Caithness, swore fealty to Edward I of England in 1297. In 1320, however, John’s son and successor Magnus subscribed, as Earl of Caithness and Orkney, the letter to the Pope in which the Scottish nobles asserted the independence of Scotland. This Magnus was the last of the Angus line of Earls, and was succeeded in 1321 by Malise, Earl of Stratherne, who is supposed to have married his daughter. Malise fell at Halidon Hill in 1333, and his son of the same name succeeded to the three Earldoms of Stratherne, Caithness, and Orkney. Malise II died c. 1350, leaving only daughters, and after an unsettled period of [55]conflicting claims to the succession, Hakon King of Norway in 1379 finally invested Henry St. Clair of Roslin, grandson of Earl Malise I, and son-in-law of Malise II, not only in the Earldom of Orkney, but in the Lordship of Shetland also. Earl Henry made himself practically independent of Norway, and built a castle at Kirkwall in defiance of the Norwegian Crown. He was succeeded in 1400 by his son Henry, whose active and interesting career as Lord High Admiral belongs to the history of Scotland. The Earls of the Sinclair family lived with considerable state, styling themselves Princes of Orkney, and their rule was on the whole popular and fortunate; but little of outside interest took place in the Islands at this period. Scottish customs, however, and traces of Scottish feudal law were slowly encroaching on the old Norse system. Earl Henry II’s son William was the last Earl of Orkney under Scandinavian rule. By the Union of Calmar in 1397 the suzerainty of the Islands had already passed, with the crown of Norway, to the Kings of Denmark. In the years 1460-61 a series of raids were—not for the first time—made on Orkney by sea-rovers from the Hebrides, and Christian I, King of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, failing to obtain redress from the Scottish Crown for this and other grievances, demanded the long arrears of the annual tribute payable by Scotland in respect of the Hebrides, in terms of the treaty of 1266. Charles VIII of France having been called in as arbitrator, a somewhat ugly contretemps was happily adjusted by the marriage of Christian’s daughter [56]Margaret to the young King James III of Scotland, and by the terms of the marriage-contract the Danish monarch not only relinquished the quit-rent for the Hebrides, but agreed to pay down a dowry of 60,000 florins. As Christian was able to find only 2000 florins of this money at the time, the Orkneys and Shetland were given in pawn to the Scottish Crown until the balance should be paid, the agreement expressly stipulating for the maintenance of Norse law in the Islands meantime. This happened in 1468, and a few years later King James negotiated the surrender by Earl William St Clair of all his rights in the Islands; whereupon by Act of the Scottish Parliament the Earldom of Orkney and Lordship of Shetland were in 1471 annexed to the Scottish Crown, “nocht to be gevin away in time to cum to na persain or persains excep alenarily to ane of ye Kingis sonis of lauchful bed,” a proviso which went by the board.