INITIAL FROM THE GREAT CHARTER OF THE UNIVERSITY, 1635/6

Granted by Charles I to confirm and settle printing privileges which had been first granted in 1632. See p. 112

Transcriber’s Note: Illustrations have been moved, where necessary, to the nearest paragraph break in the text. Images with a blue border can be clicked for a larger version, if the device you’re reading this on supports that.

INITIAL FROM THE GREAT CHARTER OF THE UNIVERSITY, 1635/6

Granted by Charles I to confirm and settle printing privileges which had been first granted in 1632. See p. 112

SOME ACCOUNT

OF THE

OXFORD

University Press

1468-1921

OXFORD

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

M CM XXII

Oxford University Press

London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen

New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town

Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai

Humphrey Milford Publisher to the University

The author desires to express his grateful thanks to all those members of the Staffs of the Press and its Branches who have helped him in the compilation of this sketch, or have contributed to its typographical or pictorial embellishment; and especially to Mr. Falconer Madan, from whose Brief Account of the University Press at Oxford (1908) the historical details here mentioned are derived.

Oxford, December 1921.

| I. | HISTORICAL SKETCH | 9 |

| II. | THE PRESS TO-DAY | |

| The Press at Oxford | 23 | |

| The Press in the War | 33 | |

| Wolvercote Paper Mill | 36 | |

| The Press in London | 38 | |

| Administration | 40 | |

| Finance | 42 | |

| Oxford Imprints | 45 | |

| Catalogues and Advertisement | 49 | |

| The Press and its Authors | 54 | |

| Bibles and Prayer Books | 58 | |

| Clarendon Press Books | 61 | |

| [7]III. | THE PRESS ABROAD | |

| India | 63 | |

| Canada | 67 | |

| Australasia | 68 | |

| South Africa | 69 | |

| China | 69 | |

| Scandinavia | 69 | |

| The United States | 70 | |

| IV. | OXFORD BOOKS | |

| Oxford Series | 73 | |

| Oxford Books on the Empire | 81 | |

| The Oxford Standard | 83 | |

| Illustrated Books | 90 | |

| Official Publications | 92 | |

| The Oxford English Dictionary | 95 | |

| The Dictionary of National Biography | 103 | |

| The Oxford Medical Publications | 106 | |

| Oxford Books for Boys and Girls | 109 | |

| List of Illustrations | 110 | |

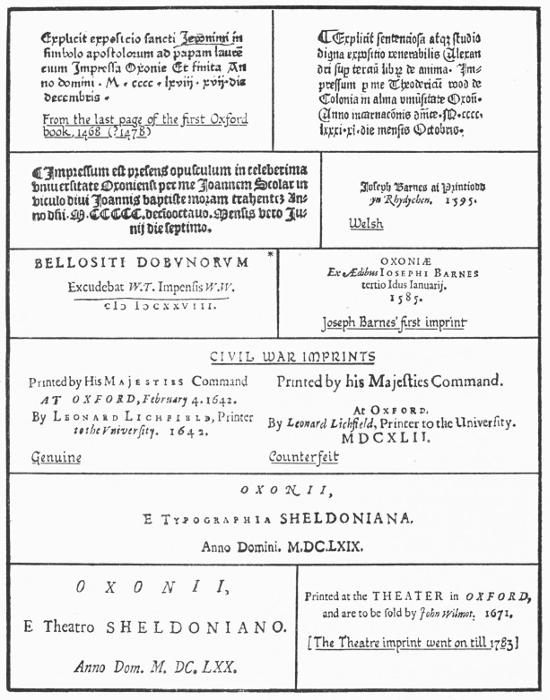

The first book printed at Oxford is the very rare Commentary on the Apostles’ Creed attributed to St. Jerome, the colophon of which is dated 17 December, Anno domini Mcccclxviij. It is improbable that a book was printed at Oxford so early as 1468; and the bibliographers are on various grounds agreed that an x has been omitted. If so, Oxford must be content to date the beginning of its Press from the year 1478; while Westminster, its only English precursor, produced its first book from Caxton’s press in 1477.

The first printer was Theodoric Rood, who came to England from Cologne, and looked after the Press until about 1485; soon after which date the first Press came to an end. The second Press lasted from 1517 until 1520,[10] and was near Merton College. Some twenty-three books are known to have issued from these Presses; they are for the most part classical or theological works in Latin. There is no doubt that this early Press was really the University Press; for many of the books have the imprint in Alma Universitate Oxoniae or the like, some bear the University Arms, and some are issued with the express privilege of the Chancellor of the University.

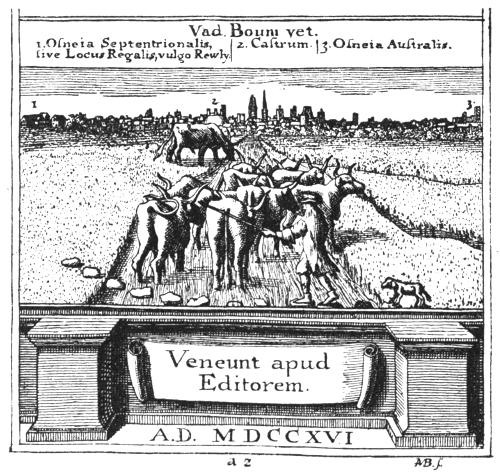

Device used on the back of the title of Sphæra Civitatis

Oxford 1588

After 1520 there is a gap in the history, which begins again in 1585. The Chancellor of that time was Queen Elizabeth’s favourite, the Earl of Leicester, who in the first issue of the new Press is celebrated as its founder. Convocation in 1584 had appointed a committee De Libris imprimendis, and in 1586 the University lent £100 to an Oxford bookseller, Joseph Barnes, to carry on a press. In the next year an ordinance of the Star Chamber allowed one press at Oxford, and one apprentice in addition to the master printer. Barnes managed the Press until 1617, and printed many books now prized by collectors, among them the first book printed at Oxford in Greek (the Chrysostom of 1586), the first book with Hebrew type (1596), Richard de Bury’s Philobiblon, and Captain John Smith’s Map of Virginia.

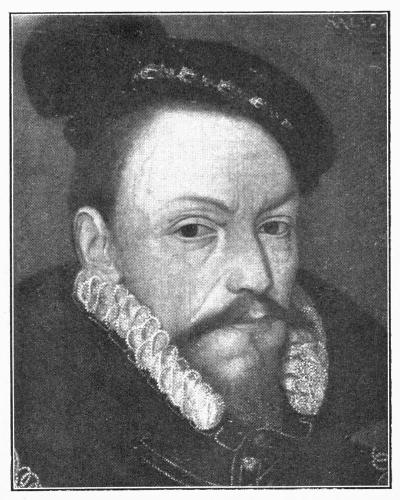

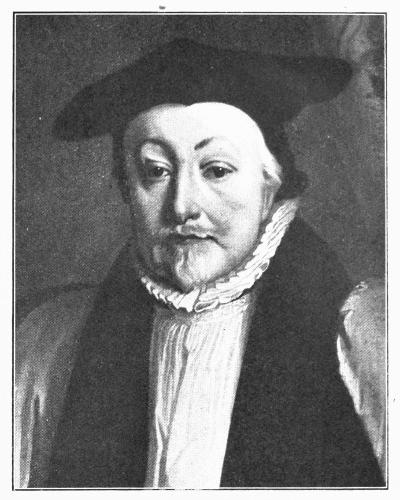

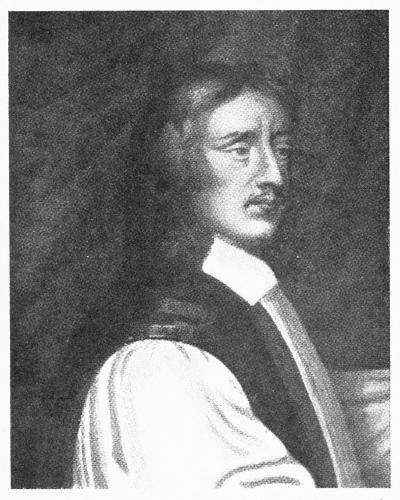

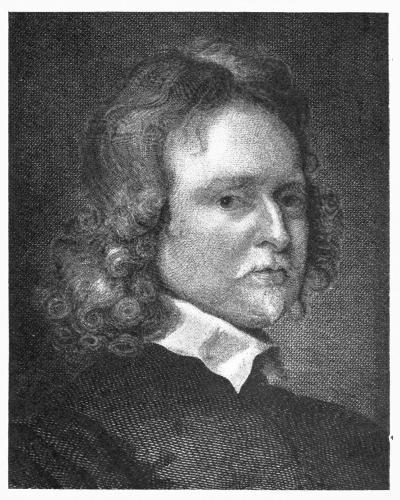

FOUR FOUNDERS OF THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Archbishop Laud

Dr. John Fell

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon

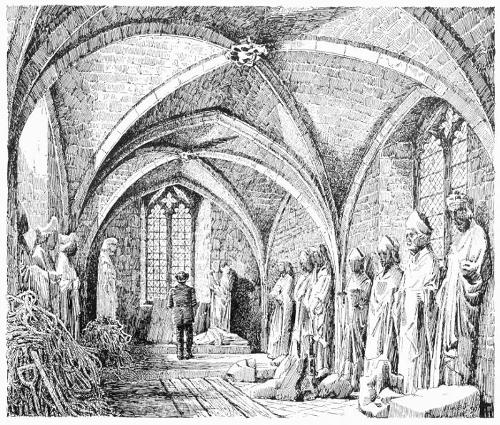

THE INTERIOR OF THE OLD CONGREGATION HOUSE

The first printing-house owned by the University; used for storing Oriental type and printing-furniture, 1652.

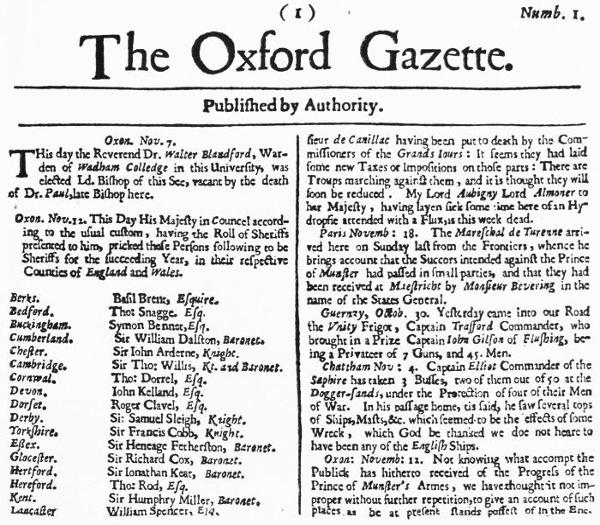

Upper part of the first page of the Oxford (now London) Gazette, 1665. The oldest newspaper still existing in England

The first notable promoter of the Oxford Press was Archbishop Laud, whose statutes contemplate the appointment of an Architypographus, and who secured for the University in 1632 Letters Patent authorizing three printers (each with two presses and two apprentices), and in 1636 a Royal Charter entitling the University to print ‘all manner of books’. The privilege of printing the Bible was not exercised at this date; but in 1636 Almanacks were produced, and this seems to have alarmed the Stationers’ Company, who then enjoyed a virtual monopoly of Bibles, Grammars, and Almanacks; for we find that in 1637 the University surrendered the privilege to the Stationers for an annual payment of £200, twice the amount of Joseph Barnes’s working capital. The most famous books belonging to what may be called the Laudian period were five editions of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy and one of Bacon’s Advancement of Learning in English.

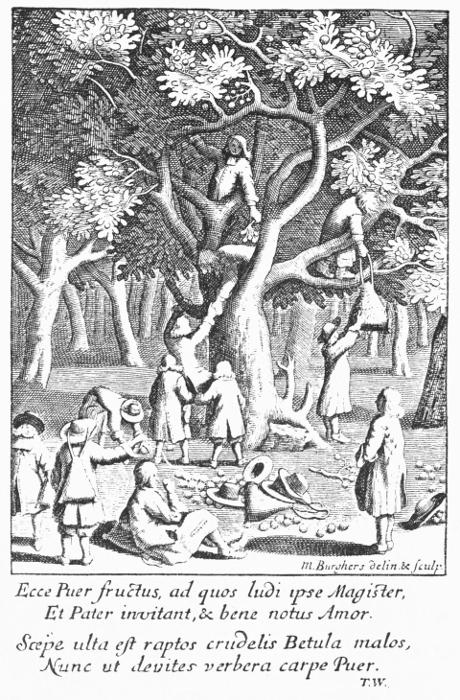

From The History of Lapland by John Shefferus, 1674, the first anthropological book published by the Press

The work of the Press during the Civil War is of interest to historians and bibliographers on account of the great number of Royalist Pamphlets and Proclamations issued while the Court of Charles I was at Oxford; a number swollen in appearance by those printed in London with counterfeit Oxford imprints. But this period is not important in the history of the Learned[15] Press; and after 1649 it suffered a partial eclipse which did not pass until the Restoration.

From W. Maundrell’s Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem, Oxford, 1703, engraved by M. Burghers

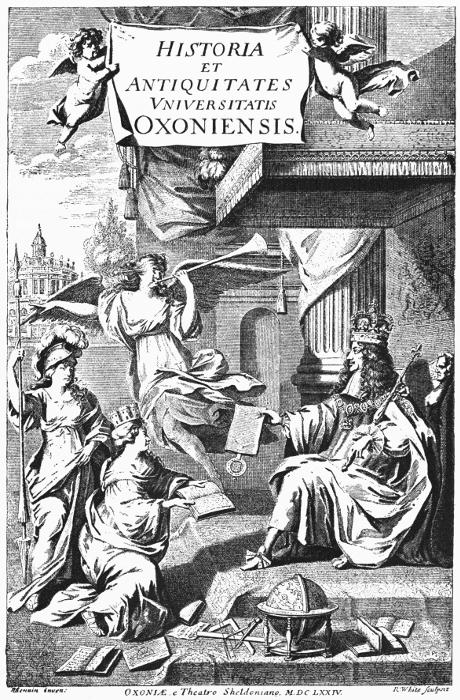

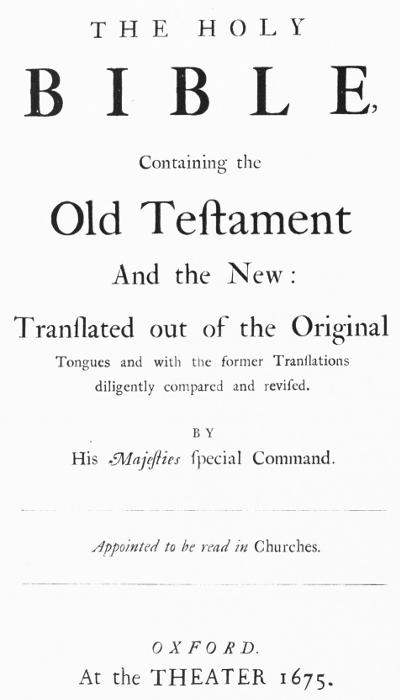

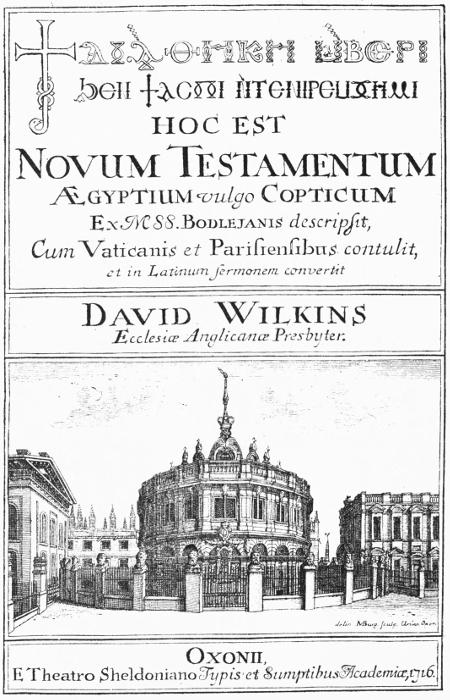

The history of the Press in the latter part of the seventeenth century will always be connected with the name of the second of its great patrons, Dr. John Fell, Dean of Christ Church and Bishop of Oxford. Fell made the great collection of type-punches and matrices from which the beautiful types known by his name are still cast at Oxford; he promoted the setting up of a paper mill at Wolvercote, where Oxford paper is still[16] made; he conducted the long, and ultimately successful, struggle with the Stationers and the King’s Printers, from which the history of Oxford Bibles and Prayer Books begins (1675). In 1671 he and three others took over the management of the Press, paying the University £200 a year and spending themselves a large sum upon its development. Lastly, it seems that he suggested to Archbishop Sheldon the provision, due to his munificence, of the new and spacious printing house and Theatre which still bears his name. The Press was installed there in 1669, and began to issue the long series of books which bear the imprint Oxoniae e Theatro Sheldoniano, or in the vulgar tongue Oxford at the Theater. These imprints, indeed, were still used, at times, long after the Press had been moved from the Sheldonian to its next home in the Clarendon Building. Many learned folios were printed at this time, including pioneer work by Oxford students of Oriental languages; the book best remembered to-day is no doubt Anthony Wood’s Historia et Antiquitates Universitatis Oxoniensis published in 1674.

To this period belongs also the first exercise of the privilege to print Bibles and Prayer Books, which was recognized, as we have seen, at least as early as 1637, when the Stationers’ Company paid the University to refrain from printing Bibles. This agreement lasted until 1642, and, by renewal at intervals, until 1672, when it was at length denounced; and in 1675 a quarto English Bible was printed at the Theater, and a beginning made of what has become an extensive and highly technical process of manufacture and distribution.

Early in the eighteenth century the Press acquired, with a new habitation, a name still in very general use. The University was granted the perpetual copyright of Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion (a possession in which it was confirmed by the Copyright Act of 1911); and the Clarendon Building was built chiefly from the profits accruing from the sales of that book. Many editions were printed in folio at various dates; and the Press Catalogue still offers the fine edition of 1849, with the notes of Bishop Warburton, in seven volumes octavo, and that of the Life in two volumes, 1857; the whole comprising over 5,000 pages and sold for £4 10s. Still cheaper is the one-volume edition of 1843, in 1,366 pages royal octavo, the price of which is 21s. More recently the demands of piety have been still further satisfied by the issue of a new edition based on fresh collations made from the manuscript by the late Dr. Macray. Though the Clarendon Building long since ceased to be a printing house, one of its rooms is still The Delegates’ Room; and there the Delegates of the Press hold their stated meetings.

In the eighteenth century the Bible Press grew in strength with the co-operation of London booksellers and finally with the establishment (in 1770, if not earlier) of its own Bible Warehouse in Paternoster Row. The Learned Press, on the other hand, though some important books were produced, suffered from the general apathy which then pervaded the University. Sir William Blackstone, having been appointed a Delegate, found that his colleagues did not meet, or met only to do nothing; and addressed to the Vice-Chancellor a vigorous pamphlet, in which he described the Press as ‘languishing in a lazy obscurity, and barely reminding us of its existence, by now and then slowly bringing forth a Program, a Sermon printed by request, or at best a Bodleian Catalogue’. The great lawyer’s polemic gradually battered down the ramparts of ignorant negligence, and the Press began to revive under the new statute which he promoted. Dr. Johnson in 1767 was able to assure his sovereign that the authorities at Oxford ‘had put their press under better regulation, and were at that time printing Polybius’.

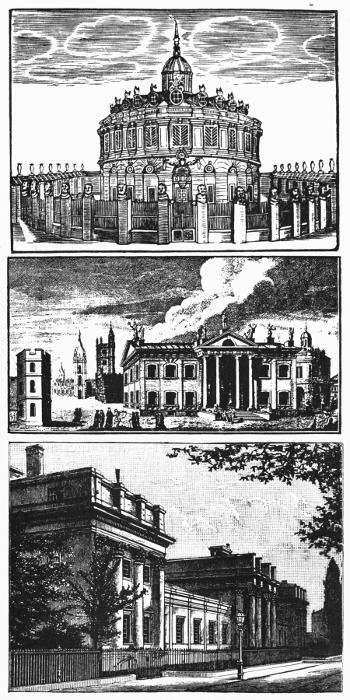

The Three University Presses

The Clarendon Building is not large, and the Press very soon outgrowing it was partly housed in various adjacent buildings, until in 1826-30 the present Press in Walton Street was erected. It is remarkable that though the building is more like a college than a factory—it is of the quadrangular plan regular in Oxford—and was built when printing was still mainly a handicraft, it has been found possible to adapt its solid fabric and spacious rooms to modern processes with very little structural alteration. Extensive additions, however, have been and are even now being made.

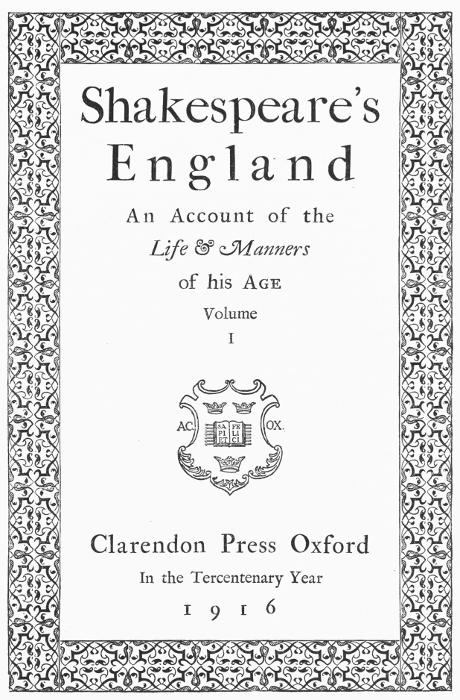

The activities of the nineteenth century are too various to detail; but a few outstanding facts claim mention. The Bible business continued to prosper, and gained immensely in variety by the introduction of Oxford India paper and by the publication, in conjunction with Cambridge, of the Revised Version of the Old and New Testaments. Earlier in the century there was a period of great activity in the production of editions of the Classics, in which Gaisford played a great part and to which many foreign scholars like Wyttenbach and Dindorf gave their support. Later, in the Secretaryships of Kitchin (for many years afterwards Dean of Durham) and of Bartholomew Price, new ground was broken with the famous Clarendon Press Series of school books by such scholars as Aldis Wright, whose editions of Shakespeare have long served as a quarry for successive editors. The New English Dictionary began to be published in 1884. Meanwhile the manufacturing powers of the Press at Oxford and the selling powers of the publishing house in London were very widely extended by the energies of Mr. Horace Hart and Mr. Henry Frowde, and the foundations were laid of the great and multifarious enterprises which belong to the history of the last twenty years.

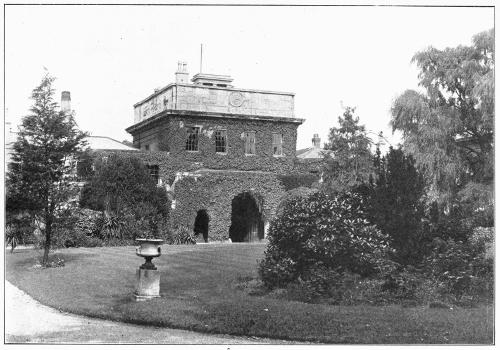

THE QUADRANGLE OF THE UNIVERSITY PRESS AT OXFORD

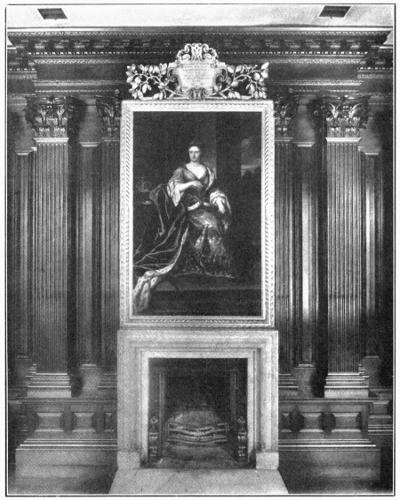

Fire-place in the Delegates’ Room Clarendon Building

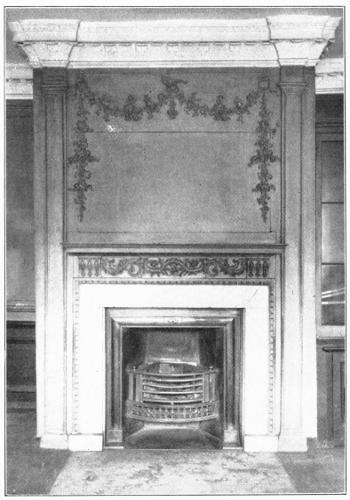

Grinling Gibbons Fire-place in one of the London Offices

The growth of the Press in the first two decades of the present century is due to the co-operation of a large number of individuals: of the members of the University who have acted as Delegates; of their officers, managers, and employees; and of the authors of Oxford books. In so far, however, as this period of its history can be identified with the name of one man, it will be remembered as that in which the late Charles Cannan served the Delegates as Secretary. The Delegates at his death placed on record their judgement that he had made an inestimable contribution to the prosperity and usefulness of the Press. The Times Literary Supplement, in reviewing the last edition of the Oxford University Roll of Service, gave some account of the services performed by the University in the war. One paragraph dealt with the work of the Press:—

‘Probably no European Press did more to propagate historical and ethical truth about the war. The death of its Secretary, Charles Cannan, a year ago, has left an inconsolable regret among all those more fortunate Oxford men, old and young, who had the honour to be acquainted with one of the finest characters and most piercing intelligences of our time. He was a very great man, and is alive to-day in the spirit of the institution which he enriched with his personality and his life.’

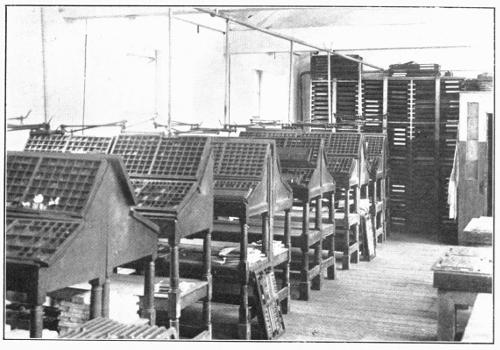

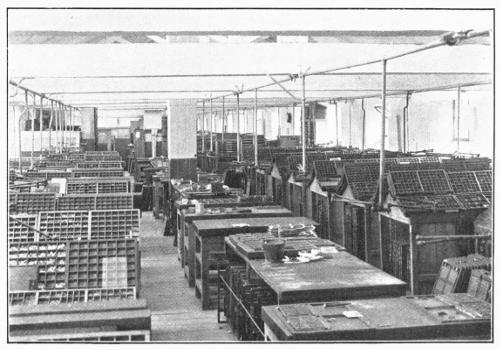

The main building of the Oxford Press, erected 1826-30, consists of three sides of a quadrangle. The two main wings, each of three floors, are still known as the Learned Side and the Bible Side, though their appropriation to Bibles and secular books has long since ceased in fact. On the Learned Side are the hand composing rooms, both the book department and the jobbing department, where some readers and compositors are employed in setting up the official papers of the University, examination papers, and other miscellaneous work, and the more difficult and complicated books produced for the Delegates or other publishers.

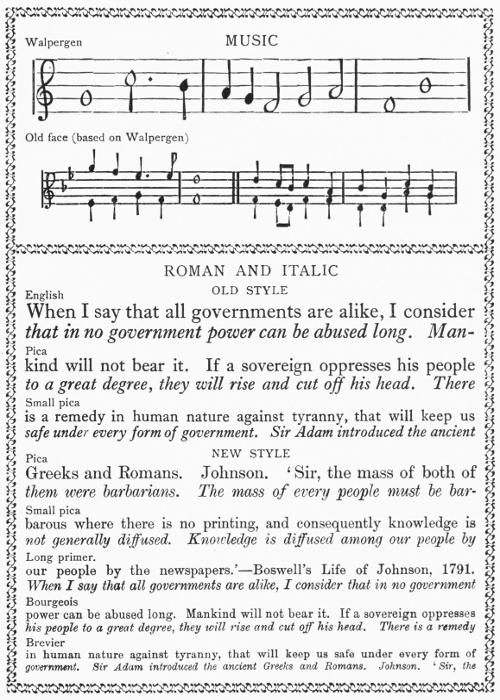

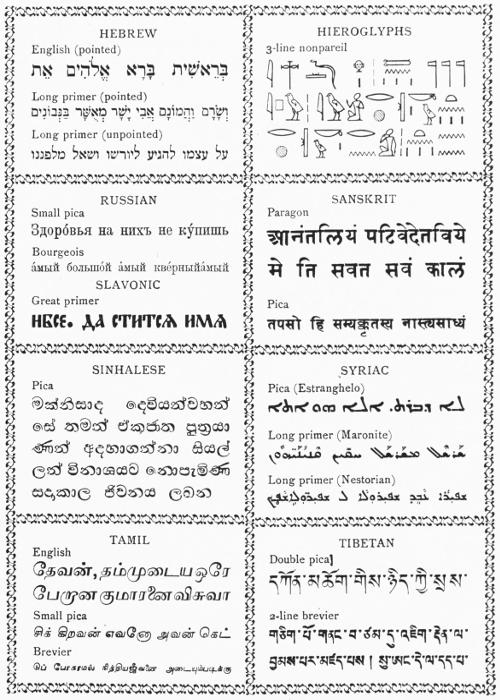

The total quantity of type in the Press is estimated at over one million pounds of metal, and includes some 550 different founts of type in some 150 different characters, ranging from the hieroglyphic and the prehistoric ‘Minoan’ (cast to record Sir Arthur Evans’s discoveries), to the phonetic scripts of Sweet and Passy; and including Sanskrit, Greek, Roman, Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Ethiopic, Amharic, Coptic, Armenian, Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese, Sinhalese, Tamil, Gothic, Cyrillic. Here, too, are the famous Fell types acquired by the University about 1667. These are virtually the same as the founts from which were printed the first edition of The Faerie Queene and the First Folio Shakespeare; and their beauty makes them still the envy of printers all the world over. Here compositors are still daily engaged in setting the Oxford Dictionary (with its twenty-one different sizes or characters of type), which has been slowly growing since 1882. One compositor has a record of thirty-eight years’ continuous work on the Dictionary.

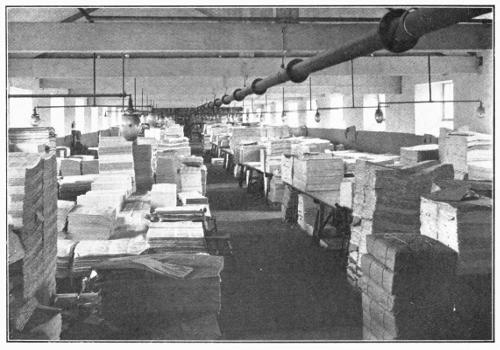

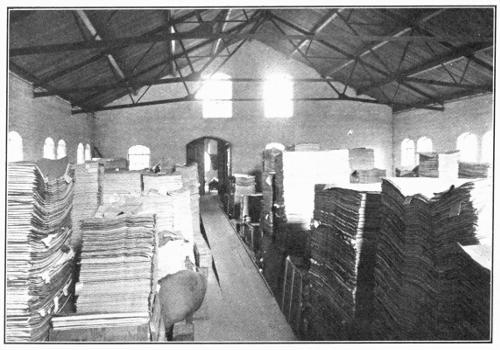

In part of the same wing is the Delegates’ Warehouse. Here, and in a number of annexes, including the old Delegates’ School built about 1840, repose the oldest and most durable of the Delegates’ publications. They are stored for the most part in lofty stacks of unfolded sheets, like the piers of a Norman crypt. From these vaults was drawn into the upper air, in 1907, the last copy of Wilkins’s Coptic New Testament, published in 1716, the paper hardly discoloured and the impression still black and brilliant. It is estimated that these warehouses contain some three and a half million copies of about four thousand five hundred distinct books.

Ancient Oak Frames in one of the Composing Rooms

The Upper Composing Room

Monotype Casters

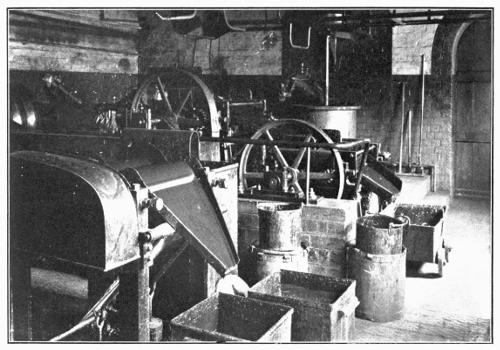

Ink-making

The Old Machine Room

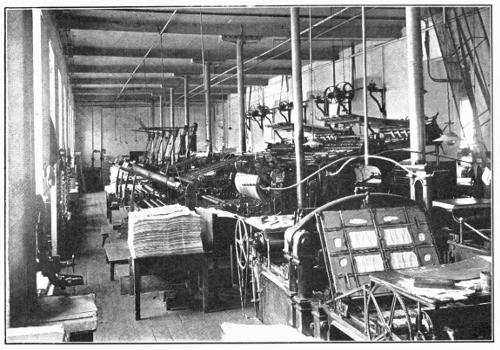

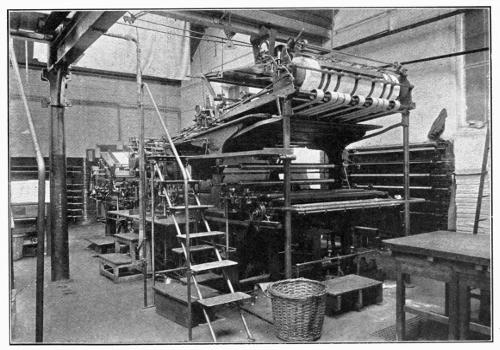

A Perfecting Machine with Self-feeder

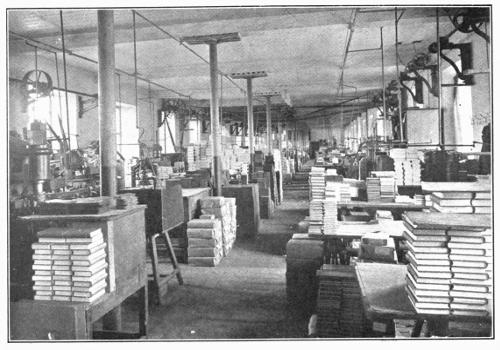

The Old Bindery (now a Warehouse)

One of the Warehouses

Of the Bible Side the ground floor is now the press room or Machine Room, which, with its more recent extensions, holds about fifty machines, from the last survivor of the old flat-impression double Platens to the most modern American double-cylinder ‘perfecting’ presses with their automatic ‘feeders’. All kinds of printing are done here, from the small numbers of an oriental book or a Prayer Book in black and red to the largest impression of a Bible printed in sheets containing 320 pages each. The long experience of printing Bibles on thin paper and especially on Oxford India paper has given the Oxford machine-minder an unrivalled dexterity in the nice adjustment required to produce a fine clean effect on paper which will not stand a heavy impression.

As the sheets come from machine they are sent to the Bindery. This was until recently on the floor above the machine room, but has lately been transferred to a larger and more convenient building erected in the old garden behind the Press. The Oxford Bindery deals with most of the Clarendon Press books in cloth bindings, and prides itself upon the fine finish of the cases and gilding of such beautiful books as the Oxford Book of English Verse, as well as on being able to turn out artistic and attractive cloth and paper bindings for books sold at the lowest prices. It still deals with a part only of the books printed under the same roof; but a large expansion is looked for in the near future.

Between the two wings, and across the quadrangle, are two houses once occupied by the late Horace Hart and by Dr. Henry Bradley, now the senior of the three editors of the Oxford Dictionary. The houses became some years ago unfit for habitation from the encroachment of machinery; but one of them was a welcome refuge during the years of war to the staff of the Oxford Local Examinations, who on the 5th of August 1914 were turned out of their office at an hour’s notice to make room for a Base Hospital.

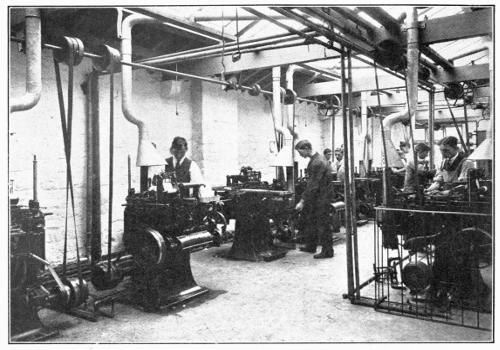

Adjacent to the houses are the fire-proof Plate Room, where some 750 tons of metal are stored, the Stereotype and Electrotype Foundry, and the Monotype Rooms, a department which has lately added to its equipment and bids fair to pass the ancient composing rooms in output. Other departments in and about the old building are the Photographic Room, famous for its collotype printing, the Type Foundry, where Fell type is still cast from the old matrices, and the Ink Factory.

The front of the building on Walton Street consists chiefly of packing rooms, where books are dispatched by rail or road to the City of London and elsewhere, and of offices—those of the Printer to the University on the ground floor and those of the Secretary to the Delegates above. Here are reference libraries of books printed or published by the Press, and records ranging from the oldest Delegates’ minute-book of the seventeenth century to modern type-written correspondence arranged on the ‘vertical’ system of filing.

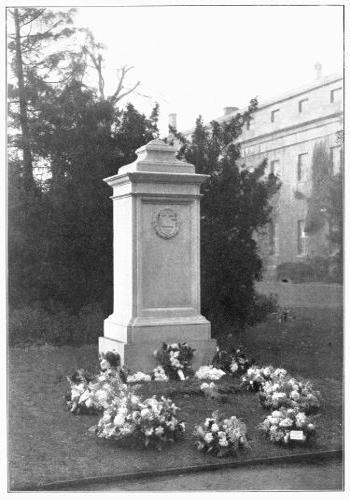

As the visitor enters the main gate the first object which catches his eye is a plain stone monument on the lawn. There are inscribed the names of the forty-four men of the Oxford Press who gave their lives in the War. Beyond the memorial is the quadrangle, made beautiful by grass and old trees; and from upper windows it is still possible to look over the flats of the Thames Valley and see the sun set behind Wytham Woods.

Corporate feeling has always been strong among the workers at the Press, and though the Delegates and their officers have done what they could to promote it, it is essentially a natural growth. Many of the work-people come of families which have been connected with the Press for generations; and they are proud not only of the old traditions of fine and honest work, but also of the usefulness and scholarly excellence of the books on which their labour is spent. The Press is, in all its parts, conscious at once of its unity and of its relation to the University of which it is an integral part.

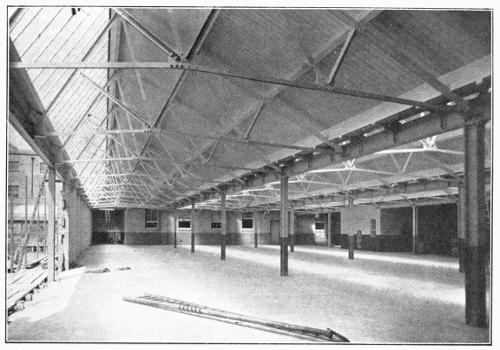

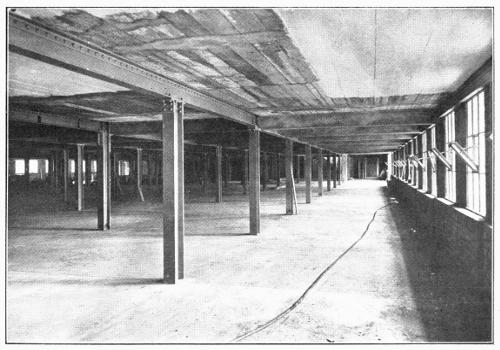

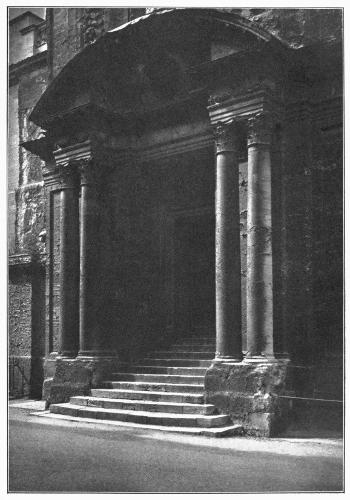

THE NAGEL BUILDING

The New Bindery

The Crypt

THE WAR MEMORIAL

This spirit is well shown by the history of the Press Volunteer Fire Brigade, constituted in 1885. The Brigade now numbers thirty-two officers and men, who by regular drills and competitions have made themselves efficient firemen, and able to assist the Oxford City Brigade in case of need. The Press possesses also a branch of the St. John Ambulance Brigade, and first aid can be given at once if any accident happens.

Various Provident and Benevolent Societies exist at the Press, and the principle of co-operation by the employer was recognized for many years before the passing of the National Health Insurance Act. The Hospitals Fund makes substantial yearly contributions to the Radcliffe Infirmary and the Oxford Eye Hospital, and in view of the pressing needs of these institutions the subscription to the Fund has recently been doubled.

The common life naturally finds expression in the organization of recreation of all kinds. There is a Dramatic Society, the records of which go back to 1860; an Instrumental Society, dating from 1852; a Vocal Society, a Minstrel Society, a Piscatorial Society; Athletic, Cricket, Football, and Bowls Clubs, now amalgamated; and, not the least useful nor the least entertaining, the Gardening Association, formed during the war to meet the demand for more potatoes. Such of the men of the Press as were obliged to content themselves with the defence of the home front, responded with enthusiasm in their own gardens and allotments; and the Food[32] Production Exhibition which crowned their efforts in the summer of 1918 became an annual event. In peace, as in war, there is need for all the food we can produce; and the Gardening Association has very wisely not relaxed its efforts.

The Clarendon Press Institute in Walton Street, close to the Press itself, provides accommodation for lectures, debates, and dramatic and other entertainments, as well as a library, a reading room, and rooms for indoor games. The building was given by the Delegates, who contribute to its maintenance, but its management is completely democratic. The members appoint their own executive and are responsible for their own finances.

The Council have since 1919 issued a quarterly illustrated Magazine, printed ‘in the house’. The Clarendonian publishes valuable and entertaining records of the professional interests and social activities of the employees of the Press, as well as affording some outlet for literary aspirations.

The Press made to the prosecution of the War both a direct and an indirect contribution. In August 1914 about 575 adult males were employed at Oxford; of these sixty-three, being members of the Territorial Force, were mobilized at the outbreak of war; and of the remainder some 293 enlisted in 1914 or later. Considering the number of those who from age or other causes were unfit for service, the proportion of voluntary enlistment was high. The London Office and Wolvercote Mill also gave their quota to the service of the Crown.

Those who were obliged to remain behind were not idle. The Oxford historians at once engaged in the controversy upon the responsibility for the War; and in September 1914 the Press published Why We are at War: Great Britain’s Case, a series of essays closely and dispassionately reasoned, and illustrated by official documents including the German White Book, reproduced exactly from the English translation published in Berlin for neutral consumption and vitiated by clumsy variations from the German original. Why We are at War rapidly went through twelve impressions, and at the instance of Government was translated into six languages. The profits were handed over to the Belgian Relief Fund. At the same time was initiated, under the editorship of Mr. H. W. C. Davis, the series of Oxford Pamphlets on war topics, of which in a short time more than half a million copies were sold all over the world. Later, when the[34] public appetite for pamphlets slackened, and the world had leisure for closer study, the series of Histories of the Belligerents was founded, which is noticed elsewhere.

‘The Clarendon Press,’ writes Sir Walter Raleigh in his Introduction to the Oxford University Roll of Service, ‘though deprived of the services of virtually all its men of military age, was active in the production of books and pamphlets, most of them written by Oxford men, setting forth the causes and issues of the War—a mine of information, and an armoury of apologetics.’

Not the least of the services rendered by the Press was the printing done for the Naval Intelligence Department of the Admiralty directed by Admiral Sir Reginald Hall. Both secrecy and speed were essential to the usefulness of this work, and to secure them the Printer to the University made special arrangements involving a severe strain upon himself and those to whom the work was entrusted. Admiral Hall, when unveiling the Press War Memorial in October 1920, declared that the work done was unique in kind, and that without the help of the Press the operations of his Department could not have been carried out with success.

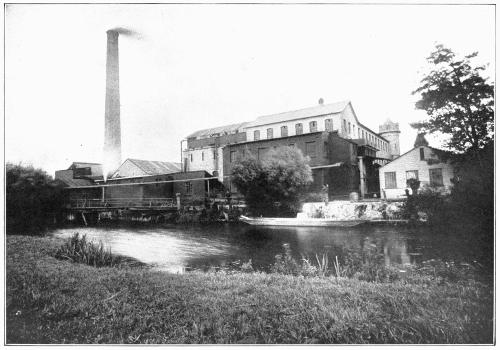

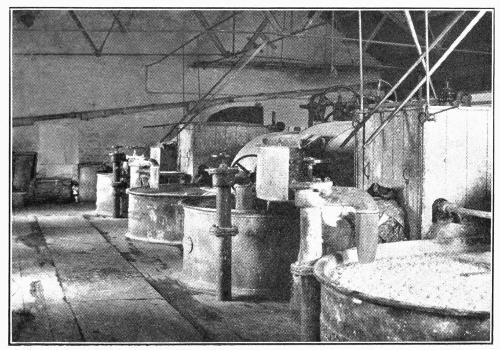

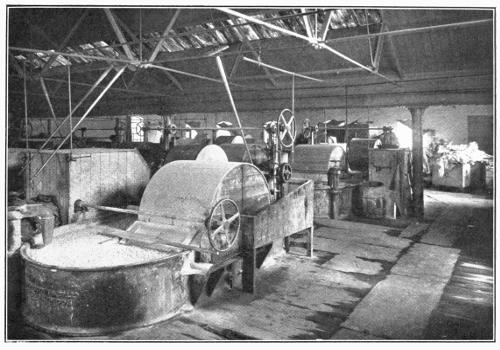

WOLVERCOTE PAPER MILL

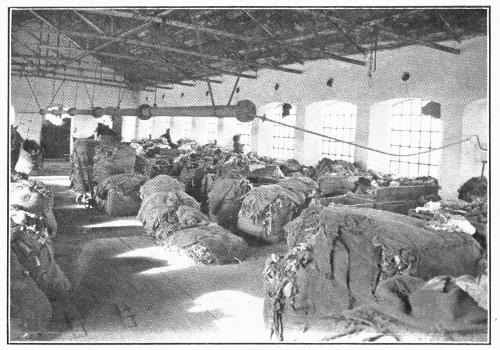

Rag Sorting

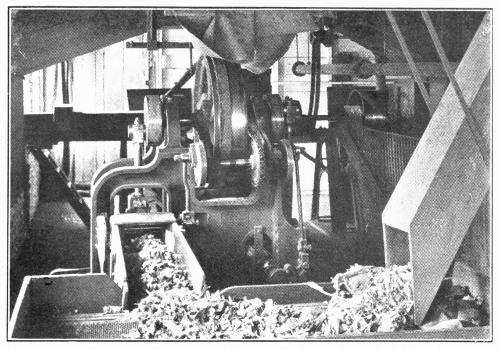

Rag Cutting

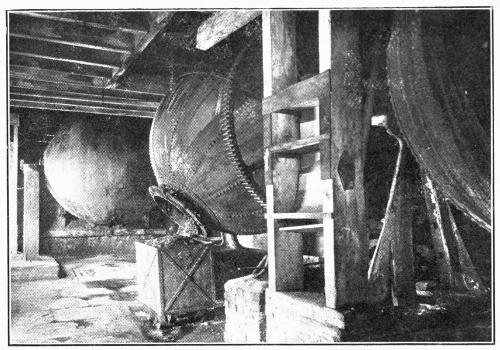

Rag Boiling

Rag Breaking

As the War dragged on, the numbers employed at the Press steadily declined; the demands of Government as steadily increased; the shortage of materials of all kinds became more and more acute. None the less the Bible Press met an unprecedented demand for the New Testament by supplying within three years four and a half million of copies for use in the field. The Learned Press, too, continued to produce, though the volume of production became less and less. The machinery of the Dictionary, though its movement was retarded, never came to a standstill. The scientific journals continued to appear, and not a few learned books were published. A greater number, however, were placed in the Delegates’ safes, in expectation of the increased facilities which the end of the War has hardly brought. The manufacturing powers of the Press, indeed, have virtually reached their pre-war level; but the ever-rising cost of labour and materials has made it as yet impossible to restore to its old volume the output of books which could at no time have been remunerative. It may be added that the Delegates, like other publishers, have had to consider that the purchasing power of the public on which they rely has not kept pace with the rise in costs. The price of books has of course risen very greatly; but the ratio of increase has been substantially lower than that of commodities in general.

The first mention of paper-making in or near Oxford is a story of one Edwards, who about 1670 planned to erect a mill at Wolvercote and was encouraged by Fell. In 1718 Hearne the antiquary wrote that ‘some of the best paper in England is made at Wolvercote Mill’. It was bought by the Press in 1870.

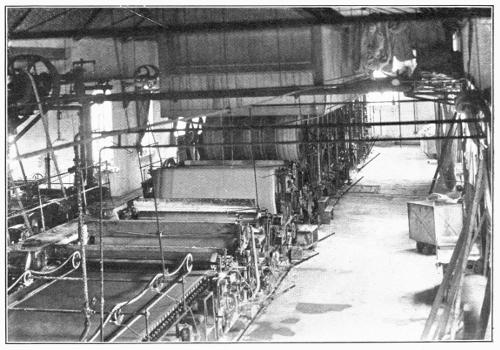

The Mill stands on a branch of the Thames, on the edge of the quiet village of Wolvercote, and near the ruins of Godstow Nunnery. The water-wheel has long ceased to play more than a very minor part in the driving of the mill, which now has two modern paper-making machines, 72 and 80 inches wide respectively. The power used is partly steam, but a large part of the plant has quite recently been electrified.

Beater Room

Machine Room

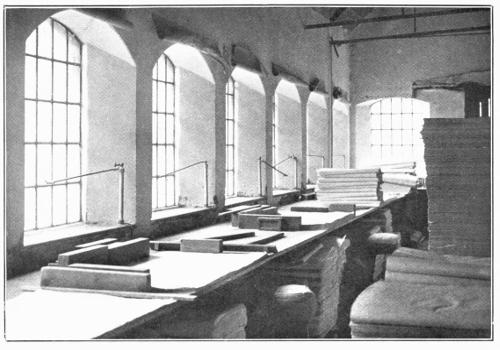

Paper Sorting

Paper Stock Warehouse

Most varieties of high-class printing paper are made at Wolvercote, which besides feeding the Press does a considerable trade with other printers. The paper made for the Oxford Dictionary and some other books is of the finest rag and is probably as durable as the best hand-made paper of former times. But the Mill is best known for its ‘Bible’ papers, exceptionally thin, tough, and opaque, with a fine printing surface. Paper of this kind reaches its acme in the famous Oxford India Paper, the invention of which made revolutionary changes in the printing of Bibles. A great many Oxford books are now printed in two editions, an ordinary and an India paper. If the saving of space is an important consideration, the convenience of the thinner editions of such books as the Concise Oxford Dictionary, the Concise Dictionary of National Biography, or the Oxford Survey of the British Empire is obvious; and many people like to read the Poets and the Classics in thin and light volumes. The Oxford Homer will go into a pocket, though it has 1,374 pages; and the India paper Shakespeare and Oxford Book of English Verse are delightfully easy to carry and handle.

The Controller of the Mill is Mr. Douglas Clapperton (a name well known in the paper trade), who succeeded Mr. Joseph Castle in 1916.

The association of the Oxford Press with London booksellers—the publishers of former days—goes back to early times. Apart from the negative agreement with the Stationers’ Company, not to print Bibles and Almanacks, we find, at the end of the seventeenth century, Oxford Bibles bearing the imprint of various London booksellers. In 1776 Dr. Johnson wrote to the Master of University College a letter, printed by Boswell, in which he sets forth with knowledge and perspicacity the philosophy of bookselling; the moral of the discourse is that the University must offer more attractive discounts to the book trade—a doctrine which has been adopted in modern times, though in 1776 it perhaps fell upon deaf ears.

Not later than 1770 a Bible Warehouse was established in Paternoster Row. But it was not until a century later that the Press undertook the distribution in London of its secular books. In 1884 these books, formerly sold by Messrs. Macmillan, were taken over by the Manager of the Bible Warehouse, Mr. Henry Frowde, who thus became sole publisher to the University; an office which he continued to hold with great skill, devotion, and success until on his retirement in 1913 he was succeeded by Mr. Humphrey Milford.

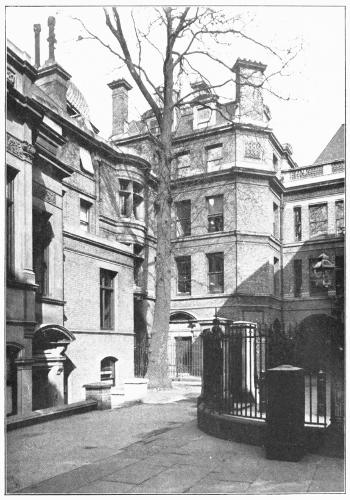

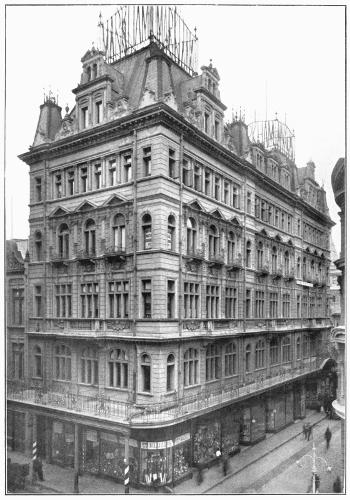

AMEN CORNER LONDON

To-day the activities of the Press in or near Amen Corner, London, E.C. 4, are multifarious. From his bound stocks Mr. Milford is ready at short notice to supply to the booksellers or booksellers’ agents any Clarendon Press book, any Bible or Prayer Book, any of the books published by himself as publisher to the University, such as Oxford Poets, World’s Classics, Oxford Elementary Books, or by himself and Messrs. Hodder and Stoughton—the Oxford Medical Publications—or for the numerous learned bodies and American Universities for whom he is agent whether in the United Kingdom or universally.

In the premises at Amen Corner alone it is estimated that upwards of three quarters of a million books are at any one time in stock. Packing and distribution is carried on in the basement and also at Falcon Square, where the large export department operates. Mr. Milford also maintains at Old Street a ‘quire’ department from which books in sheets are given out to his own or other binderies, and in Aldersgate Street a bindery from which many of the finest Bibles and other leather books are turned out.

The offices at Amen Corner are the centre of the selling activities of the Press; from them is directed the policy of the branches of the business at home and abroad. An institution so far-flung naturally causes some confusion in the public mind. Inquiries from India have sometimes been addressed to New York, and Mr. Horace Hart treasured an envelope addressed to The Controller of the Universe. In general, however, it is now widely understood that inquiries for books should be addressed (by booksellers, or by the public, if the usual trade channels fail) to Oxford University Press in London or at the nearest Branch (New York, Toronto, Melbourne, Cape Town, Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Shanghai, Copenhagen); questions about printing to Controller, Clarendon Press, Oxford, and proposals for publication either to the nearest Branch or direct to the Secretary, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

All the activities of the Press may be described as a function of the corporation known as the Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Oxford, acting through the Delegates of the Press. The constitution of this Delegacy is in some respects peculiar. So long ago as 1757 the statute promoted by Sir William Blackstone for the better management of the Press established the principles of continuity and of expert knowledge by the constitution of Perpetual Delegates; and these principles have been maintained.

The Delegacy is now composed of the Vice-Chancellor and Proctors for the time being ex officio, and (normally) of ten others, of whom five are Perpetual. Delegates are appointed for a term of years by the Vice-Chancellor and Proctors, by whom they may be re-elected; but when a vacancy occurs among the perpetual Delegates, the Delegates as a whole are enjoined by statute to ‘subrogate’ one of the junior Delegates to be perpetual, ad supplendum perpetuo numerum quinque Perpetuorum Delegatorum.

The roll of the Delegates contains the names of many famous scholars. Among those of recent times may be mentioned William Stubbs, Ingram Bywater, Frederick York Powell. Within the last few years the Press has sustained very heavy losses in the death of some of the most experienced of its Delegates. William Sanday, Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity, took an active part in the many works of profound learning upon New Testament criticism, by which Oxford has maintained its fame for the prosecution of Biblical learning. Henry Tresawna Gerrans, Fellow of Worcester College, was active in financial administration and in the organization of[41] educational publications. David Henry Nagel, Fellow of Trinity College, gave invaluable advice on scientific books and on technical processes of manufacture. He was chiefly responsible for the plan of the new Bindery, recently completed, which bears his name. The services of Sir William Osler, Regius Professor of Medicine, and of Charles Cannan, of Trinity College, for over twenty years Secretary to the Delegates, are noticed elsewhere in these pages.

The composition of the board on 1 December 1921 was as follows:

The Vice-Chancellor (Dr. L. R. Farnell, Rector of Exeter College) and the Proctors; T. B. Strong, Bishop of Ripon and formerly Dean of Christ Church (extra numerum, by Decree of Convocation); C. R. L. Fletcher, Magdalen College; P. E. Matheson, Fellow of New College; D. G. Hogarth, Fellow of Magdalen College and Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum; N. Whatley, Fellow of Hertford College; Sir Walter Raleigh, Fellow of Merton College and Professor of English Literature—all perpetual Delegates: H. J. White, Dean of Christ Church; Sir Archibald Garrod, Student of Christ Church and Regius Professor of Medicine; Cyril Bailey, Fellow of Balliol College; H. E. D. Blakiston, President of Trinity; and N. V. Sidgwick, Fellow of Lincoln.

The principal officers are: in Oxford, R. W. Chapman, Oriel College, Secretary; J. de M. Johnson, Exeter College, Assistant Secretary; F. J. Hall, Printer to the University; in London, Humphrey Milford, New College, Publisher to the University; in New York, W. W. McIntosh, Vice-President of the American Branch; in Toronto, S. B. Gundy, Manager of the Canadian Branch; in Bombay, G. F. J. Cumberlege, Worcester College, Manager of the Indian Branch; in Melbourne, E. R. Bartholomew, Manager of the Australian Branch.

For some two centuries from the time of Fell the Press was partly controlled by private partners; since the last of these was bought out by the efforts of Bartholomew Price, the University has been completely master of all its printing and publishing business. The Press to-day has no shareholders or debenture-holders, and subserves no private interest. On the other hand it possesses virtually no endowment. The whole of its great business has been gradually built up by the thrifty utilization of profits made by the sale of its books or in a minor degree from work done for outside customers. The maintenance of the Learned Press, with its output of scholarly and educational books, many of which are in their nature unremunerative, depends and has always depended upon the profitable management of the publications of the Press as a whole. In the last century the revenue devoted to learning was supplied mainly from the sale of Bibles and Prayer Books; but changing conditions led the managers of the Press to the conclusion that if the promotion of education and research were to keep pace with the growing volume and range of the demand, it would be necessary to expand the general activities of the business in many directions.

In prudent pursuance of a far-sighted policy, the overseas Branches of the Press were established to increase the sale of Oxford books; new departments of the publishing[43] business were created, such as the very extensive series of cheap editions of the English Classics, and, more recently, the Oxford Elementary Books and the Oxford Medical Publications; and in the course of years the publications of the Learned Press itself have gradually become more popular in character and addressed to a wider audience. In the event, the Press to-day possesses a business of such magnitude and variety as will, it may be hoped, enable it to surmount the formidable obstacles which the increased cost of manufacture opposes to the production of all works of learning.

The demands made upon the Press for the organization and publication of research are now at least as great as ever. It has again and again been pointed out by the friends of research, that organization and encouragement are idle unless the publication of valuable results is guaranteed; and in the past scholars in this country, and not in this country only, have looked to the Presses of Oxford and Cambridge to do the work which in Germany was carried out by Academies subsidized by Government for this purpose. But the fulfilment of such expectations is far more onerous than formerly. The tenth and last volume of the great English Dictionary, now more than half printed, will when it is complete have cost at least £50,000. The revised edition of Liddell and Scott’s Greek Lexicon, upon which the Delegates embarked some years before the war, is now estimated to cost £20,000. These are enterprises in the successful conclusion of which the honour of the University is concerned; and they will be concluded; but the date of completion, and therefore the initiation of other projects of learning, have inevitably been retarded by the events of the last seven years.

The endowment of research is a difficult subject, and nobody is more conscious than are the Delegates of the Press, that results of lasting value are not achieved by the mere expenditure of money. Yet they cannot but be aware that by the possession of the machinery and traditions of such works as the English Dictionary, and by their intimate association with experts in many fields, they are in a position to promote research and co-operative enterprise in the most effective and economical way. The support given to the Press in the past, whether by individuals or by other institutions devoted to learning, has been trifling in consideration of the work which it has produced. The need of such support is now far more urgent; and the record of the Press is proof that financial support would be turned to good account.

The imprints used by the Press as printers and as publishers are various, and their import is not always understood. Oxford at the Clarendon Press is historically and strictly a printer’s imprint, and it is confined to books printed at Oxford; but it has come to mean more than this, and to be appropriated to such books as are not only printed at Oxford, but are also published auctoritate Universitatis, their contents as well as their form being certified by the University, acting through the Delegates of the Press. A book with this imprint may in general be assumed to be published at the expense of the Delegates; but the ‘Clarendon Press imprint’ has come to be so prized as carrying the Oxford ‘hall-mark’ that its use has occasionally been solicited and accorded for works of learning produced under the patronage of government or of learned societies within the Empire and the United States of America.

The Press publishes also, in the ordinary course of business, large numbers of books for which the Delegates assume a less particular responsibility; these are issued with the London imprint of the Publisher to the University (Oxford University Press: London, Humphrey Milford) or those of its branches abroad (Oxford University Press American Branch, Oxford University Press Indian Branch and so on), or on behalf of the numerous universities, learned societies, or private publishers for whom the University Press publishes either universally or in certain parts of the world. Among the bodies for whom the Press acts as publisher are the British Museum, the British Academy, the Early English Text Society, the Chaucer Society, and the Philological Society; the Egypt Exploration Society, Society of Antiquaries, the Pali Text Society, the Church Music Society, and the Royal Society of Literature; the Universities of St. Andrews, Bombay, and Madras; the University Presses of Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Princeton; the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, the American Historical Association, and the American Scandinavian Foundation. The Oxford Medical Publications and some other books are issued with the joint imprint of Henry Frowde (Mr. Humphrey Milford’s predecessor as Publisher to the University) and Hodder and Stoughton. The Press is publisher in Australia to many English houses.

Until recent years the Press has relied on its trade catalogues and special lists, and on the skilled assistance of the bookseller, to make known to the public the great number and variety of its issues of the Bible, the New Testament, Prayer Books, Hymn Books, and kindred works, as well as of its general publications—reprints, medical books, elementary books and so on; while the Clarendon Press Catalogue of learned and educational books was a relatively modest affair of under 200 pages. The need of a single general catalogue for the information of librarians and book-lovers had long been felt, but pressure of business delayed its preparation until the late Mr. Charles Cannan addressed himself to the task, and with the devoted co-operation of his daughters (who had replaced the members of the office staff gone forth to war) and the advice of many scholars, produced in 1916 the first edition of the General Catalogue, comprising over 500 pages of close print and including under one comprehensive classification all the secular books sold by the Press, wheresoever printed, and whether published by the University on its own account or on behalf of other University Presses or learned bodies; together with a representative list of Bibles, &c. (useful to the inquirer though not intended as any substitute for the elaborate trade catalogues or for the indispensable guidance of the expert bookseller), and a very full alphabetical index.

The General Catalogue has in the second edition been brought up to January 1920, and a third edition is in preparation. Supplements are also from time to time issued comprehending the books published since the current edition of the Catalogue. The Supplement now current comprises all books published in 1920.

For the convenience of specialists the Catalogue is also issued in sections—History, Literature, the Classics, Natural Science, Cheap Reprints—and special lists have recently been made of books on such subjects as the British Empire, International Law and Politics, India, Modern Philosophy. Schoolmasters and University teachers are asked to apply for the Select Educational Catalogue issued at frequent intervals, which by omission of the larger and more elaborate books allows of illustrative information for which there is no room in the general catalogue.

The General Catalogue has been computed to contain over 8,000 distinct books or editions of books. These vary from such works as the New English Dictionary and the Dictionary of National Biography, with their 15,000 and 30,000 pages, to the smallest and cheapest pamphlets and school-books. The total may be guessed to comprise something like two and a half millions of printed pages of which no two are identical.

The issue of the Catalogue has secured a wide and increasing recognition of the comprehensive character of Oxford publications. ‘There are publishers and publishers, but there is only one Oxford University Press’, exclaims a writer in the Athenaeum; and many reviewers have noted with sympathetic admiration the value of the Catalogue, not as a mere price list but as a work of reference and as a book to read. Though it[51] necessarily requires revision as new publications accrue, it is hoped that the Catalogue will not be treated as ‘throw-away literature’. It is a well-printed and solidly bound book, and the cost of supplying free copies to book-buyers all over the world is not inconsiderable.

The Press produces two periodicals descriptive of its publications: the official Bulletin distributed to booksellers, librarians, and other professional buyers, and the unofficial Periodical addressed to amateurs. Number 1 of the Bulletin (4 April 1912) consisted of a single page; but the desire for more information was widely expressed, and a recent number contains in eight pages a classified list of books published during four weeks, with bibliographical and other particulars, a statement of the various catalogues obtainable on application, extracts from reviews, and a list of books which have gone out of print since the current issue of the catalogue. This list is designed to protect booksellers and the public against the assumption, too frequently made, that any and every book is ‘out of print’ which cannot be produced at a moment’s notice. The public are asked not to believe too easily that books are unobtainable. A provincial bookseller (in a University town) recently declared himself ‘unable to trace’ an Oxford book, published in 1920, reviewed at length by the leading literary papers, and advertised nearly every other week in the Times Literary Supplement. Many books no doubt (though not many Oxford books) have been and still are out of print; and in the absence of an up-to-date index of current books, the difficulties of the bookseller have been great. Now, however, when the 1920 edition of the trade Reference Catalogue is available, with its single alphabetical index (of 1,075 pages in double column), the[52] ascertainment of the facts is not difficult except in so far as the catalogues indexed have themselves become obsolete. All information about Oxford books that is not in the 1920 Reference Catalogue may be found in the Supplement of Books published in 1920, or in the cumulative list of Price Changes, or in the Bulletin; all of which every bookseller has, or may have for the asking.

With the Bulletin is issued from time to time a supplement calling the attention of librarians and others to Oxford books in some special field. The circulation of the Bulletin is about 2,000.

The Periodical is a ‘house magazine’, perhaps the first of its kind. It was first published in December 1896, and now appears five times a year. Its contents include extracts, of sufficient length to be readable, from new Oxford books, specimen illustrations, quotations from reviews and other newspaper comment on the productions of the Press, obituaries and other honorific notices of authors (on appointment, decoration, or the like), and a certain amount of quasi-literary gossip; for even authors have their foibles. The original editor, who has compiled every number for a quarter of a century, is still at his post, and the popularity of the little paper increases. The demand comes from all over the world—the United States takes nearly half the total and the number of copies distributed gratis of each issue now exceeds ten thousand.

Oxford Bibles and Prayer Books can be inspected in mass at many booksellers’, as well as in the Depository at 116 High Street, Oxford, and in the showrooms at Amen Corner, in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and in the Branches overseas. Lack of space has everywhere made it impossible to exhibit the far greater number of Clarendon[53] Press and other secular books on the same scale, but the books may be seen on application at any of the Press offices, and the popular series, gift books, &c., are always displayed. It is hoped before long to increase the space available for this purpose in the Oxford Depository, and to exhibit there all Clarendon Press books, arranged by subjects as in the Catalogue, so that members of the University and visitors may be able to inspect at one time and place all the books offered in any subject that may concern them. It is hoped to find room for separate exhibits of school-books, maps, and ‘juvenile’ books, so that the busy schoolmaster, with half an hour to spare in Oxford, may make a rapid survey of the contents of the Educational catalogue.

The Index to the General Catalogue contains the names of some three thousand living authors and editors. With almost all of these the Press deals direct, and not through agents, and their friendly co-operation is of immense service to the Delegates and their officers both in planning books and in securing for them the widest publicity.

Many of the books accepted by the Press are such as in the ordinary way of business would not secure a publisher except under subvention from the author or some favourer of learning; and of these the remuneration (or at least the direct remuneration; for the publication of solid books, like the knowledge of Greek in former times, ‘not infrequently leads to positions of emolument’) is recognized as being nominal, and necessarily inadequate to the labour and skill lavished upon the work. But for books commanding a remunerative sale, if they are of a suitable kind, the Press is prepared to pay the full market value; and it is believed that not many of its authors are dissatisfied with the bargains they have made.

‘It is an immense advantage to an author to be printed by a famous Press’, is the opinion of a veteran of letters, whose name appears in many publishers’ catalogues. It is the aim of the Oxford Press to place at its authors’ service its capacity for accurate and beautiful printing and binding, the goodwill attached to the University[55] imprint, and the selling power enjoyed by its very large organization in the United Kingdom and throughout the world. Publication by the Press gives to an author the further security that his book will not be remaindered, pulped, or allowed to go out of print on the mere ground that it does not enjoy a rapid sale.

It is still sometimes said that ‘the Press does not advertise’. It is believed that Oxford books, in an exceptional degree, advertise themselves and each other—‘the Oxford book’, says an American advertisement, ‘is half sold already’; but the magnitude and variety of its business enable the Press to maintain an elaborate organization of ‘publicity’, which directs its efforts both to the booksellers and to the public at large. It relies largely upon the distribution, in many thousands of copies annually, of its catalogues and bulletins, on the direct dispatch of prospectuses to a large yet carefully selected constituency of buyers in various fields, and on the incalculable factor of public and private discussion. The value of judicious newspaper advertisement is not overlooked, as readers of the Times Literary Supplement well know.

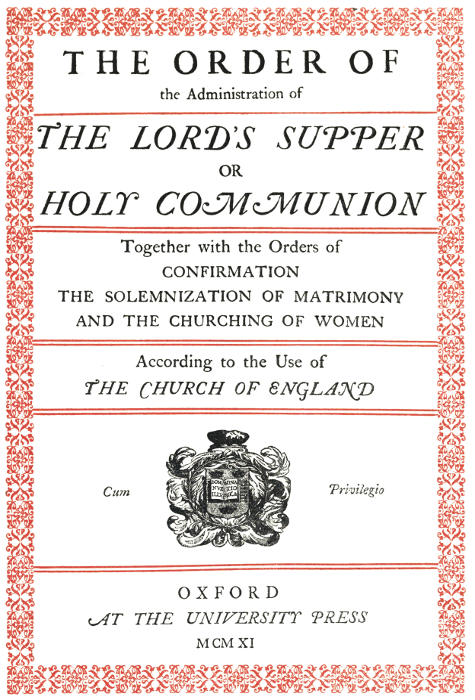

Some account has already been given of the exercise by the University of its privilege of printing ‘the King’s books’ in early times. The modern history of the printing and publishing of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer is a large subject. The University of Oxford, like the other privileged printers, has appreciated the obligations attached to the privilege as well as the opportunities which it affords. Every attention has been paid to accuracy and excellence of printing and binding, to the provision of editions suited to every purpose and every eyesight, and to the efficient and economical distribution of the books all over the world at low prices. In all these respects a standard has been reached which is unknown in any other kind of printing and publishing, and which is only made possible by long experience, continuous production, and intensive specialization. The modern Bible is so convenient to read and to handle[59] that its bulk is not always realized; it is actually more than four times as long as David Copperfield. A reference Bible is, also, a highly complicated piece of printing. Accuracy is secured by the employment of highly-skilled compositors and readers—a new Bible is ‘read’ from beginning to end many times—and by the use of the best material processes; for all Bibles are printed from copper plates on the most modern machines, and the sheets are carefully scrutinized as they come from the press. The Oxford Press offers a guinea for the discovery of a misprint; but very few guineas have been earned.

The bulk and weight of Bibles are kept down by the use of very thin and opaque paper, specially made at the Press Mill at Wolvercote. The use of such paper, and especially of the Oxford India paper, the combination in which of thinness with opacity has never been equalled, may be said to have revolutionized the printing of Bibles, by making possible the use of large clear type in a book of moderate size and weight.

Of the Prayer Book as of the Bible a large number of editions is offered to suit all fashions and purposes, and this in spite of the serious risks arising from the liability to change of the ‘royal’ prayers. A demise of the Crown, or the marriage of a Prince of Wales, makes it necessary to print a large number of cancel sheets, which have to be substituted for the old sheets in all copies held in stock or in the hands of booksellers.

A hundred years ago there were nineteen Oxford Bibles and twenty-one editions of the Book of Common Prayer. There are now more than a hundred of each. The Revised Version of the Bible, the copyright of which belongs to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge jointly, is also published in a large variety of editions.

By Clarendon Press Books are meant the learned, educational, and other ‘Standard’ works produced under the close supervision of the Delegates and their Oxford Secretariate, and printed at Oxford. These books have a long history, and the Catalogue contains very many titles which have been continuously on sale for nearly a century. The Coptic New Testament of Wilkins, published in 1716, is believed to have been continuously on sale at the original price of 12s. 6d. until the last copy was sold in 1907, only a few years short of the second century. The current edition of the General Catalogue mentions as ‘the oldest Oxford book still on sale’ another edition of the Coptic New Testament by Woide, published in 1799 and now sold for two guineas; but it has since been noticed that an injustice had been done, and that pride of place should have been given to the Gothic Gospel, a magnificently printed quarto published in 1750, of which some dozen copies (at 30s.) still remain.

These are extreme examples; they are, however, the result not of oblivion or of indifference, but of a policy which has long been and is still being pursued. The Press produces many works of learning which are so securely based that it is known that the demand, however small, will persist as long as there are copies unsold; and it is the practice of the Press to print from type large editions of such books. Clarendon Press books are[62] neither wasted nor sold as remainders, and when a book goes out of print, some natural tears are shed.

This is one end of the scale; at the other are books commanding a large and rapid sale, books like the Oxford Book of English Verse or the Concise Oxford Dictionary and livres de circonstance like Why We are at War, which was published in September 1914 and in a few months went through twelve impressions and was translated into six foreign languages. Books of this kind are produced in mass, as cheaply as is consistent with a high standard of workmanship, and are sold all over the world in competition with rival publications and by the employment of appropriate methods of advertisement.

Between these two classes lies a great mass of miscellaneous books, too general in character to admit of description here. They are in many languages, ancient and modern, of the East and of the West; of all fields of knowledge, divine, human, and natural; and of all stages of history from the Stone Age to the Great War. It follows necessarily that Clarendon Press books appeal to widely different publics and call for the application of various instruments of distribution and publicity. All, however, benefit by the widely diffused appreciation of the standards of scholarship and of literary form which the Press has set itself to uphold. The public expects much of any Oxford book, and the satisfaction of that expectation is often onerous; but the necessary effort is justified by the results—‘the Oxford book is half sold already’.

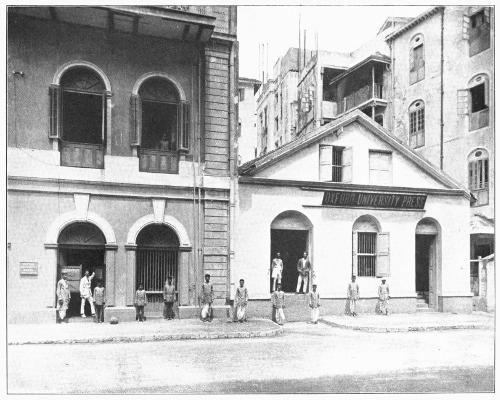

The activities of the Press in India are of relatively recent date. Until 1912, when a branch was opened in Bombay, Oxford books had been accessible only to those who were determined to procure them. The existence of a distributing centre made it possible to reach more directly the educational and the general public. But it early became apparent to the Manager—Mr. E. V. Rieu of Balliol College—that the educational needs of India could only to a small extent be met by direct importation; that it was necessary to adapt existing books to the special requirements of the country, and to create new books similar in kind. In the course of a few[64] years many such books were produced, at first chiefly in England, but later to an increasing degree in India itself. By 1918 at least a dozen native presses were engaged in printing and binding for the Branch. These books range from ‘simplified classics’ to editions of Shakespeare’s plays, from school geographies to handbooks for students of medicine and law. At the same time the sale of more advanced Oxford books was largely increased. A brief description is given elsewhere of the books produced at Oxford upon the history and art of India as well as upon its classical literature and its religions. Books like Mr. Vincent Smith’s Early History of India and his Fine Art in India command a wide sale among the educated natives of India.

Another field of enterprise is in vernacular education. Here the opportunities are vast, but the difficulties are great, for in most provinces many languages are spoken, and no one press is adequately equipped with the numerous founts of type required to deal with the vernaculars of India as a whole. The Branch was therefore fortunate in being, in 1916, invited by the Government of the Central Provinces to produce a series of Readers—in Hindi and Marathi—for use in schools throughout the province. At that time no paper could be imported from England, and the staff of the Branch was depleted by war. Nevertheless, within a year over half a million volumes had been written, printed, and illustrated, and were ready for distribution over a country nearly twice as large as England and Wales.

The activities of the Branch in placing the issues of the War before Indian readers in a true light attracted in 1918 the attention of Government; and the Branch was engaged by the Central Publicity Bureau to produce[65] an illustrated War Magazine and a mass of pamphlets in English and the vernacular tongues.

In spite of these preoccupations the Branch has been able to emulate the activities of the Press at home by co-operating with learned bodies in India to produce books of scientific value. Notable among its publications in this kind are the historical treatises of Mr. Rawlinson, Mr. Kincaid, Mr. Mookerji, and other writers, and the economic studies published on behalf of the Universities of Bombay and Madras.

Mention may also be made here of the Classics of Indian History which are being issued by the Press. In reviewing the latest volume of the series—Meadows Taylor’s Story of My Life—The Times Literary Supplement says: ‘It is one of those books from which history hereafter will be written. The great books—in one sense or other—like Colonel Mark Wilks’s Historical Sketches of Southern India, Grant Duff’s History of the Mahrattas, Tod’s Rajasthan, Broughton’s Letters from a Mahratta Camp, must be supplemented not only by the native records, which are more and more becoming accessible, but by the personal narratives of Englishmen who lived in out-of-the-way places and entered into the lives of the rural inhabitants of India. Beside Colonel Sleeman’s Reminiscences must be put the autobiography of Meadows Taylor, a much superior book.’ Of the books mentioned by The Times, Sleeman’s and Tod’s have already been issued, uniform with Meadows Taylor’s, Dubois’s Hindu Manners, Bernier’s Travels, Mrs. Meer Hassan Ali’s Mussulmanns, and Cunningham’s Sikhs; editions of Grant Duff and Broughton are in preparation.

Mr. Rieu, when in 1919 reasons of health compelled him to retire, had in a few years proved himself a real[66] pioneer. He had immensely increased the volume of business done by the Branch, and had opened up new and promising fields. His successor, Major G. F. J. Cumberlege, D.S.O., of Worcester College, who was accompanied by Mr. N. L. Carrington, of Christ Church, took over a successful and growing business. The original premises in Bombay had already been outgrown, and new offices opened in Elphinstone Circle. The increase of staff has made it possible to open a new branch in Calcutta—a sub-branch in Madras already existed—and it is confidently hoped that in the near future the business done in Oxford books, and adaptations of them, will be increased in volume, and that the service rendered by Oxford to the Indian Empire will be further enhanced by the activities of its Press.

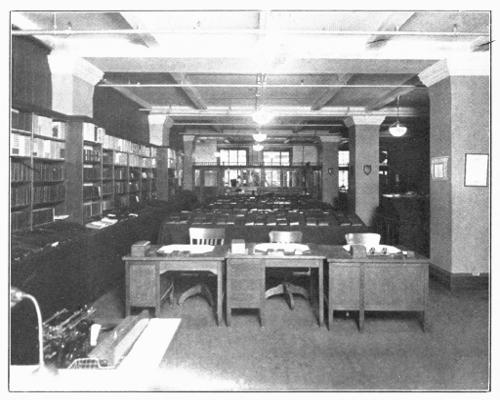

THE BOMBAY BRANCH

THE TORONTO BRANCH

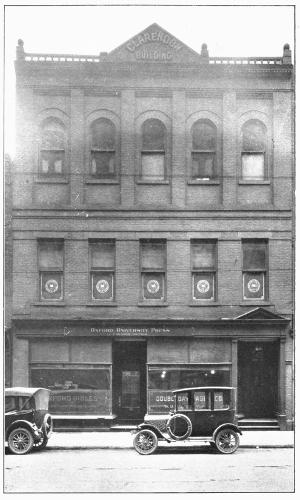

The Oxford University Press Canadian Branch was founded in 1904 at 25 Richmond Street West, Toronto. The manager was Mr. S. B. Gundy, who still presides at the same address; but the building was destroyed by fire in 1905 and completely reconstructed.

Although Canada has still a relatively small population, scattered over an immense area, the volume of business done by the Branch is substantial, and it continues to grow. The sale of Oxford Bibles, Clarendon Press books, Medical and Elementary books is supplemented by the sale of books published in Canada and the United States, for which Mr. Gundy acts as agent. Thus the Branch sells all the publications of the great American house of Doubleday, Page and Company; and through this connexion it has recently become the sole publisher in Canada of the works of Mr. Rudyard Kipling.

Among the more notable Canadian enterprises of the Press are the Church of England Hymn Book (the Book of Common Praise), published in 1909, the large stocks of which caused Mr. Gundy ‘to overflow into a neighbouring barber shop’, and the new edition of the Presbyterian Book of Praise, produced in defiance of submarines and other obstacles in 1917. The editor, the Rev. Alexander Macmillan, carried the manuscript across the Atlantic in small packets sewn into his clothes.

This part of the business was first developed by visits regularly made from London by Mr. E. R. Bartholomew, who in 1908 became manager of the Branch then established at Cathedral Buildings, Melbourne. Australia is not only many thousands of miles from the great centres of book-production, but is itself a land of great distances, as yet but sparsely populated; and this creates difficulties for both publishers and booksellers. It is remarkable how far these obstacles have been overcome; and if regard is paid to the number and character of the population, Australia, and New Zealand no less, have a right to be proud of the quantity and quality of the books they buy.

The Branch has paid attention to the special needs of Australian education, and in co-operation with the universities and schools has produced a number of successful text-books.

It acts as agent for some of the leading British publishers, including the houses of Murray, Heinemann, Black, Chapman and Hall, and Mowbray; and for the large publishing business of Messrs. Angus and Robertson of Sydney.

THE MELBOURNE BRANCH

MARKHAM’S BUILDINGS, CAPE TOWN

in which the South African Branch is situated

The South African Office of the Press is at Markham’s Buildings, Adderley Street, Cape Town. Mr. C. R. Mellor, the present Representative, was appointed to that post in March 1915. From his office at Cape Town Mr. Mellor visits the principal booksellers, not only in the Cape Province, but in the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Natal.

The Chinese Agency of the Press is at C 445 Honan Road, Shanghai, of which Mr. T. Leslie is the present Representative. The first agent in China for the Press was the Christian Literature Society of Shanghai, the agency being started in 1913. Mr. Leslie, who had been manager of that Society, took over the Press agency in 1917. Stocks of all Oxford books likely to be in demand in China are held in Shanghai.

For many years before the war a traveller from Amen Corner visited the Continent annually, but business in Scandinavia developed so rapidly after the Armistice that it was found desirable to open a Branch, and premises were accordingly secured in Copenhagen, Mr. H. Bohun Beet, the Continental traveller of the Press, being appointed manager. The Branch was opened in August 1920, at St. Kongensgade 40 H, close to the King’s Palace. The Branch represents also Messrs. Hodder & Stoughton and the Medici Society.

The sale of Oxford books in the United States began long before the foundation of the American Branch. It is recorded that ‘the growth of the business was hindered by the Civil War, but after the restoration of peace it grew rapidly’; and that a landmark in its progress was the publication of editions of the American Book of Common Prayer.

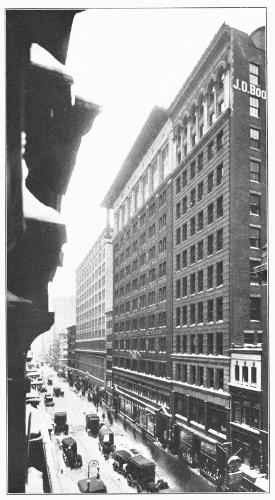

The foundation of the Oxford University Press American Branch, an institution which has made the name of Oxford familiar throughout the Union, was due to the foresight and enterprise of Mr. Henry Frowde. Acting on his advice the Delegates of the Press authorized the formation of a Corporation in the State of New York, and the Branch in 1896 opened premises at 91 Fifth Avenue, under the management of the late Mr. John Armstrong. In the following year Mr. Armstrong added to the Bibles and other books, previously sold by Messrs. Nelson, the Clarendon Press publications, previously sold by the Macmillan Company. The business grew rapidly in Mr. Armstrong’s hands, and in 1908 moved ‘up town’ to the premises it now occupies at 35 West 32nd Street. Mr. Armstrong died in 1915, and was succeeded by Mr. W. W. McIntosh, one of the original members of the staff.

THIRTY-SECOND STREET, NEW YORK

The New York Branch is situated in the Central Building on the right

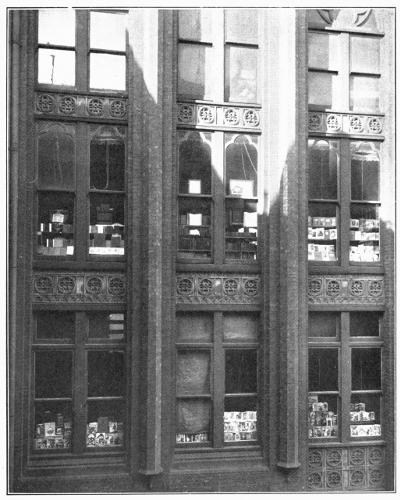

SHOW ROOMS AT THE NEW YORK BRANCH

Bible Show Room

Clarendon Press Show Room

The main function of the Branch has always been that of keeping the American public acquainted with Oxford books, both sacred and secular, and of supplying the books without avoidable delay. To this end it has been necessary to hold large stocks in New York, and to maintain an expert staff which is in touch with the book-stores and with the universities, the schools, and the book-buying public at large. The Branch has its own catalogues and its own advertisements, and it has been able to make Oxford Bibles and Clarendon Press books known and valued throughout the United States. The Branch, however, is not merely an importer; it has long recognized that many Oxford products are capable of useful adaptation to special American requirements, and that such adaptation is consistent with the preservation of what Americans have themselves called ‘the Oxford stamp’. This aspect of the activities of the Press in America is shown by the large number of Bibles which are manufactured (‘made’ is the American idiom) in the United States—among these the now famous Scofield Reference Bible is conspicuous—and also by books written—or at least rewritten—for American requirements. The Branch, in co-operation with American scholars, has produced valuable series of text-books for schools and universities—the Oxford English Series, the Oxford French Series, and the Oxford German Series. Even more important, perhaps, are adaptations of Oxford books of tried merit. Thus the Oxford Loose-Leaf Surgery derives from a (British) Oxford original (one of the Oxford Medical Publications), but has important differences in substance as well as in its novel form. This very successful work is now being followed by the Oxford Loose-Leaf Medicine, edited by Dr. Henry Christian and Sir James Mackenzie with the help of leading physicians on both sides of the Atlantic. To promote co-operation of this kind in medical science was a great part of the[72] life-work of William Osler, who, as Regius Professor at Oxford, and a leading promoter of the Oxford Medical Publications, may be described as the founder of the medical activities of the Oxford Press as they are now carried on in Oxford, in London, in New York, and in Toronto.

Another work of adaptation, now in progress, illustrates further the possibilities of Anglo-American co-operation. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of current English, adapted from the great Oxford Dictionary, has been and is very widely used throughout the British Empire and by students of English in foreign countries. But its spelling, and certain other features, were found to disqualify the book for general use in the United States; and a special American edition is now in preparation, the adapter of which is Mr. G. Van Santvoord, of Oriel College, Oxford, and Yale University.

The Press is publisher, on both sides of the Atlantic, to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, many of whose books have been printed at Oxford. Special mention may be made of the first volumes, printed at the Press and recently published, of the British Section of the great Economic and Social History of the World War undertaken by the Endowment. These volumes are by Professors Keith and Bowley and Mr. J. A. Salter.

At one time Oxford books were produced almost always at the instance of an author; and many Oxford books are still so produced. A scholar having devoted, it may be, many years of his life to a subject which he has made his own, applies to the University Press for publication of his researches; and such a claim is often admitted as irresistible. In modern times, however, the need for organization by the publisher has become increasingly apparent. Many books which if published in isolation would reach only a small public are found capable of a wider usefulness when issued as part of a larger plan; and thus the initiative in publishing passes more and more into the hands of the professional commanding the advice of a body of experts. School-books, reprints[74] of the Classics, text-books of the applied sciences, and books of the nature of Dictionaries and Encyclopaedias are now almost always conducted in this way by co-operative enterprise.

The number of such homogeneous series promoted by the Press during the last twenty years is large, even if all school-books are excluded. The Oxford English Dictionary (which is of earlier origin) bulks so large in the public eye as somewhat to obscure all humbler enterprises; but it does not stand alone. In English literature the Press has built up in a quarter of a century a whole library of uniform series, all of respectable dimensions. The Oxford English Texts are library editions of famous authors edited after exhaustive examination of the materials, in print and in manuscript, and handsomely printed from type; the Tudor and Stuart Library consists of first editions and exact reprints of famous books of that period, printed in the types of the period on paper calculated to last for many centuries more; these books are now finding their way into the second-hand catalogues and the collections of connoisseurs; the Oxford Library of Prose and Poetry is a series of little books for fanciers, offering especially the classics of the Romantic Revival in a form approximating to that of the originals; the Oxford Poets claim to be the last word for accuracy of text, condensed yet fine printing, and the lowest price compatible with these qualities; the Oxford Standard Authors offer the same texts as the Oxford Poets, together with many prose classics, in a cheaper form; the average volume containing nearly 600 pages of close yet legible print. Finally, the World’s Classics furnish a collection of over two hundred of the most famous English books in a very handy form, still maintained in print as far as possible in spite of the costs[75] of production, which make it increasingly difficult to keep any but the most popular books on sale in a cheap series.

None of these series has been created by the simple expedient of taking an existing edition and sending it to the printer—a plan too commonly followed, as is well known to every one who has ever investigated the text of a well-known author, and has found that each edition contains almost all the errors of its predecessors and adds fresh errors of its own. The Oxford texts are the result of the laborious co-operation of editor, publisher, and printer, involving the choice of the most authoritative original—very often the collation of a number of printed originals and sometimes of manuscripts as well—expert attention to the problems both editorial and typographical of which the successful solution produces a well-designed book, and finally scrupulous diligence in the elimination of error. The substantial accuracy of Oxford texts is widely recognized, and is known to be due to the united vigilance of the editors, the publishers (themselves scholars and sometimes editors), and the printers. It is less well known how complex and difficult are the problems which the modern editor has to solve. The scientific editing of English texts is indeed a relatively recent growth, and depends upon the application of principles which in the field of Greek and Latin textual criticism have been elaborated in the course of centuries. It is thus no accident that the work done in English editing in the last five-and-twenty years has been largely in the hands of scholars trained in the Oxford school of Literae Humaniores, and has synchronized with the production of the Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis.

This series, now popularly known as the Oxford Classical Texts, is the only large series of critical texts of Greek[76] and Latin authors produced in recent times outside Germany and able to hold its own in competition with its great German rivals. The texts, which now fill nearly eighty volumes and include the most important writers of the ‘classical’ periods of Greek and Roman literature, have been based upon much fresh examination of the manuscript originals. Some of the editors, indeed, have devoted years to this kind of investigation; the labours of Mr. Allen on the manuscripts of Homer and of Professor Clark and Sir William Peterson on those of Cicero have secured for their authors a permanent place in the long history of classical scholarship.

The aim of the series is to give the best text which the examination of the manuscripts in their relation to each other affords, and to provide in a brief apparatus criticus sufficient information to show the evidence on which the editor has based his decision. Conjectural emendations are mentioned in the notes when they are considered plausible, but are not admitted to the text except where they reach a high degree of probability. This principle, which is mainly due to the authority of the late Ingram Bywater, has commended itself in the course of years even to those who were at first disposed to think it too austere, and has greatly enhanced the permanent value of the series, which before the war was finding its way into Germany itself. A famous German publisher went so far indeed as to address to Oxford (on the eve of the war) a letter of remonstrance on the price of the series, which was described as too low for its value.

The Oxford Library of Translations consists mainly of prose versions of Greek and Latin authors. These have not been made to order or in accordance with any single[77] principle of translation, but have been produced at the instance of scholars unable to deny themselves the satisfaction of translating a favourite author. This, which is perhaps the best guarantee of excellence, accounts for the miscellaneous constitution of the series, which has been enlarged by degrees as a happy conjunction of author and translator chanced to present itself, and from the same cause admits some interesting authors seldom or never included in series of translations made upon a less elastic plan.

Another series of translations is the great collection of the Sacred Books of the East, which was begun many years ago by the late Max Müller and reached its fiftieth and concluding volume in 1910. The value of these translations to Orientalists is shown by the steady sale, which after forty years is still increasing, and by the high prices asked for the few volumes which are now unfortunately out of print.