SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM ART HANDBOOKS.

Edited by WILLIAM MASKELL.

No. 2.—IVORIES ANCIENT AND MEDIÆVAL.

These Handbooks are reprints of the dissertations prefixed to the large catalogues of the chief divisions of works of art in the Museum at South Kensington; arranged and so far abridged as to bring each into a portable shape. The Lords of the Committee of Council on Education having determined on the publication of them, the editor trusts that they will meet the purpose intended; namely, to be useful, not alone for the collections at South Kensington, but for other collectors by enabling the public at a trifling cost to understand something of the history and character of the subjects treated of.

The authorities referred to in each book are given in the large catalogues; where will also be found detailed descriptions of the very numerous examples in the South Kensington Museum.

August, 1875.

BY

WILLIAM MASKELL.

WITH NUMEROUS WOODCUTS.

Published for the Committee of Council on Education

BY

CHAPMAN AND HALL, 193, PICCADILLY. [Pg vi]

FIFTY COPIES ON LARGE PAPER,

WITH ADDITIONAL ILLUSTRATIONS.

| FOLLOWING PAGE |

|

| PASTORAL STAFF CARVED IVORY WITH FIGURES. | Frontispiece |

| IVORY CARVING. ONE LEAF OF THE DIPTYCHON MELERETENSE. | 34 |

| IVORY CARVING. CIRCULAR MIRROR COVER. DATE 1300-1330. | 74 |

| IVORY CARVING, HEAD OF A TAU OR T SHAPED STAFF, IN WALRUS | |

| TUSK, THE COMPARTMENTS CONTAINING THE SIGNS OF THE ZODIAC. | 85 |

| CROSIER IN CARVED IVORY AND GILT METAL. | 86 |

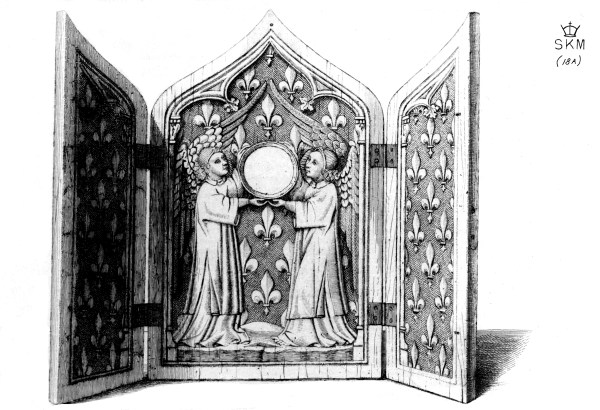

| TRIPTYCH, SERVING AS A RELIQUARY IN CARVED IVORY ABOUT 1480. | 96 |

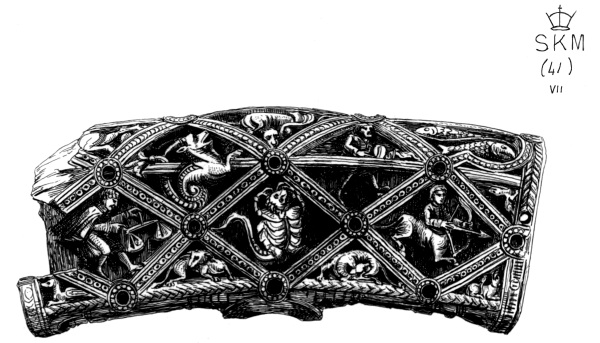

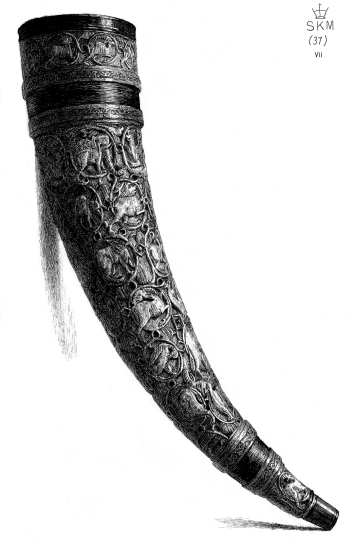

| HORN OR OLIPHANT. IVORY. BYZANTINE. 11TH CENT. | 114 |

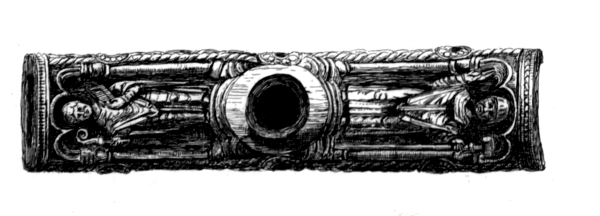

| PLAQUES OR PANELS OF A CASKET, ONE A FRAGMENT, IVORY, FRENCH. | 116 |

| CARVED IVORY BOX, WITH ARABIC INSCRIPTION. HISPANO-MORESCO. | 118 |

| PAGE | |

| Prehistoric carving | 9 |

| Esquimaux carving | 9 |

| Prehistoric carving in relief | 10 |

| ”” in outline | 11 |

| ”” of the Mammoth | 11 |

| Angel; end of fourth century | 36 |

| Vase; end of sixth century | 46 |

| Book cover; Carlovingian | 49 |

| Panel of an English casket; eighth century | 53 |

| Another panel of the same | 54 |

| St. Peter’s chair | 56 |

| Spanish Moresque panel | 57 |

| Coffer painted with medallions | 59 |

| Open-work; two small panels | 64 |

| Italian marriage coffer | 64 |

| Part of a Predella, in bone | 66 |

| Cover of a box, with Morris Dancers | 68 |

| English comb; eleventh century | 70 |

| Italian comb; sixteenth century | 71 |

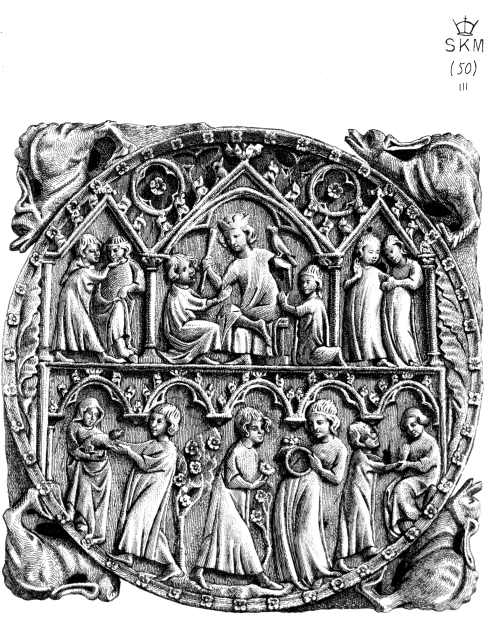

| Mirror case; fourteenth century | 74 [Pg viii] |

| Another”” | 75 |

| Chessman; twelfth century | 80 |

| ” thirteenth century | 81 |

| Arm of a chair; eleventh century | 82 |

| Two groups of chessmen, found in the island of Lewis | 83 |

| The volute of a pastoral staff; thirteenth century | 87 |

| ””” English; twelfth century | 90 |

| One leaf of a diptych in very high relief; fourteenth century | 100 |

| Group, a Pietà; late fourteenth century | 103 |

| Painter at work on a statuette | 105 |

| Chaplet and beads; and girdle, with ivory clasps | 112 |

| Horn; fifteenth century | 113 |

| Two panels in open-work; fourteenth century | 115 |

| Panel in minute open-work | 115 |

| Leaf of diptych, executed for bishop Grandison; fourteenth century | 117 |

IVORIES

ANCIENT AND MEDIÆVAL.

Every description or account of Carvings in Ivory ought to include similar carvings in bone, of which last many remarkable examples are to be found in the South Kensington and other museums. The rarity and value of ivory frequently obliged workmen to use the commoner and less costly material.

In the strictest sense, no substance except the tusk of the elephant presents the characteristic of true ivory, which, “now, according to the best anatomists and physiologists, is restricted to that modification of dentine or tooth substance which, in transverse sections or fractures, shows lines of different colours or striæ proceeding in the arc of a circle, and forming by their decussations minute curvilinear lozenge-shaped spaces.” Upon this subject the reader should consult a valuable paper, read by professor Owen, before the Society of Arts, in 1856, and printed in their journal.

But, besides the elephant, other animals furnish what may also be not [Pg 2] improperly called ivory. Such as the walrus, the narwhal, and the hippopotamus. The employment of walrus ivory has ceased among southern European nations for a long time; and carvings in the tusks of that animal are chiefly to be found among remains of the mediæval and Carlovingian periods. In those ages it was largely used by nations of Scandinavian origin and in England and Germany. The people of the north were then unable to obtain and may not even have heard of the existence of true elephant ivory. In quality and beauty of appearance walrus ivory scarcely yields to that of the elephant.

Sir Frederick Madden tells us, in a communication published in the Archæologia, that “in the reign of Alfred, about a.d. 890, Ohtere, the Norwegian, visited England, and gave an account to the king of his voyage in pursuit of these animals, chiefly on account of their teeth. The author of the Kongs-Skugg-sio, or Speculum Regale (composed in the 12th century), takes particular notice of the walrus and of its teeth. Olaus Magnus, in the 15th century, tells us that sword-handles were made from them; and, somewhat later, Olaus Wormius writes, ‘the Icelanders are accustomed, during the long nights of winter, to cut out various articles from these teeth. This is more particularly the case in regard to chessmen.’” Olaus Wormius speaks in another place of rings against the cramp, handles of swords, javelins, and knives.

There is still another kind of real ivory—the fossil ivory—which is now extensively used in many countries, although it may be difficult to decide whether it was known to the ancients or to mediæval carvers. In prehistoric ages a true elephant, says professor Owen, “roamed in countless herds over the temperate and northern parts of Europe, Asia, and America.” This was the mammoth, the extinct Elephas primigenius. The tusks of these animals are found in great quantities in the frozen soil of Siberia, along the banks of the larger rivers. Almost the whole of the ivory turner’s work in Russia is from Siberian fossil ivory, and [Pg 3] the story of the entire mammoth discovered about half a century ago embedded in ice is well known to every one. Although commonly called fossil, this ivory has not undergone the change usually understood in connection with the term fossil, for their substance is as well adapted for use as the ivory procured from living species.

With regard to the tusks of elephants, African and Asiatic ivory must be distinguished. The first, “when recently cut, is of a mellow, warm, transparent tint, with scarcely any appearance of grain, in which state it is called transparent or green ivory; but, as the oil dries up by exposure to the air, it becomes lighter in colour. Asiatic ivory, when newly cut, appears more like the African, which has been long exposed to the air, and tends to become yellow by exposure. The African variety has usually a closer texture, works harder, and takes a better polish than the Asiatic.” It would be mere guessing to attempt to decide the original nature of ancient or mediæval ivories. Time has equally hardened and changed the colour of both kinds, whether African or Asiatic.

We cannot easily suggest any way in which the very large slabs or plaques of ivory used by the early and mediæval artists were obtained. The leaves of a diptych of the seventh century, in the public library at Paris, are fifteen inches in length by nearly six inches wide. In the British museum is a single piece which measures in length sixteen inches and a quarter by more than five inches and a half in width, and in depth more than half an inch. By some it is thought that the ancients knew a method, which has been lost, of bending, softening, and flattening solid pieces of ivory; others suppose that they were then able to procure larger tusks than can be got from the degenerate animal of our own day. Mr. McCulloch, in his dictionary of commerce, tells us that 60 lbs. is the average weight of an elephant’s tusk; but Holtzapffel, a practical authority, declares this to be far too high, and that 15 or 16 lbs. would be nearer the average. Be this as it may, pieces of the size above mentioned (and larger specimens probably exist) [Pg 4] could not be cut from the biggest of the tusks preserved in the South Kensington museum; although it weighs 90 lbs., is eight feet eleven inches long, and sixteen inches and a half in circumference at the centre. This tusk is the largest of five which were presented to the Queen by the king of Shoa about the year 1856, and given by Her Majesty to the museum. The other four weigh, respectively, 76 lbs., 86 lbs., 72 lbs., and 52 lbs. They are all, probably, male tusks. An enormous pair of tusks, weighing together 325 lbs., was shown in the Great Exhibition of 1851; but these, heavy as they were, measured only eight feet six inches in length, and did not exceed twenty-two inches in circumference at the base.

An ingenious mode of explaining how the great chryselephantine statues of Phidias and other Greek sculptors were made, is proposed and fully explained in detail by Quatremère De Quincy in his work on the art of antique sculpture. He gives several plates in illustration, more particularly Plate XXIX.; but none of them meet the difficulty of the large flat plaques. The natural form of a tusk would adapt itself easily, so far as regards the application of pieces of very considerable size, to the round parts of the human figure.

Mr. Hendrie, in his notes to the third book of the “Schedula diversarum artium” of Theophilus, says that the ancients had a method of softening and bending ivory by immersion in different solutions of salts in acid. “Eraclius has a chapter on this. Take sulphate of potass, fossil salt, and vitriol; these are ground with very sharp vinegar in a brass mortar. Into this mixture the ivory is placed for three days and nights. This being done, you will hollow out a piece of wood as you please. The ivory being thus placed in the hollow you direct it, and will bend it to your will.” The same writer gives another recipe from the Sloane manuscript (of 15th century), no. 416. This directs that the ingredients above mentioned “are to be distilled in equal parts, which would yield muriatic acid, with the presence of water. Infused in this [Pg 5] water half a day, ivory can be made so soft that it can be cut like wax. And when you wish it hardened, place it in white vinegar and it becomes hard.”

Sir Digby Wyatt, in a lecture read before the Arundel society, quotes these methods from Mr. Hendrie and adds another from an English manuscript of the 12th century: “Place the ivory in the following mixture. Take two parts of quick lime, one part of pounded tile, one part of oil, and one part of torn tow. Mix up all these with a lye made of elm bark.” These various recipes have been tried in modern days, and the experiments, hitherto, have completely failed.

Considerable variety of colour will be observed in the various pieces of any large collection, and much difference in the condition of them. Some, far from being the most ancient, are greatly discoloured and brittle in appearance; others retain their colour almost in its original purity and their perfect firmness of texture, seemingly unaffected by the long lapse of time. The innumerable possible accidents to which carved ivories may have been exposed from age to age will account for this great difference, and a happy forgetfulness, perhaps owing to a contemptuous neglect at first of their value and importance, may have been the cause of the comparatively excellent state and condition of many. Laid aside in treasuries of churches and monasteries, or put away in the chests and cupboards of great houses, the memory even of their existence may have passed away for century after century.

It does not appear that any good method is known by which a discoloured ivory can be bleached. All rough usage of course merely injures the piece itself, and removes the external surface. Exposure to the light keeps the original whiteness longer, and in a few instances may to some extent restore it. It need hardly be observed that any other attempt to alter the existing condition, whatever it may be, as regards the colour of an antique or mediæval ivory is to be condemned.

It is quite a different matter to endeavour to preserve works in ivory [Pg 6] which have suffered partial decomposition, and which can be kept from utter destruction only by some kind of artificial treatment. Almost all the fragments sent to England by Mr. Layard from Nineveh were in this state of extreme fragility and decay. Professor Owen suggested that they should be boiled in a solution of gelatine. The experiment was tried and found to be sufficiently effectual; and it is to be hoped that the present success will prove to be lasting. “Since the fragments have been in England,” says Mr. Layard, “they have been admirably restored and cleaned. The glutinous matter, by which the particles forming the ivory are kept together, had, from the decay of centuries, been completely exhausted. By an ingenious process it has been restored, and the ornaments, which on their discovery fell to pieces almost upon mere exposure to the air, have regained the appearance and consistency of recent ivory, and may be handled without risk of injury.”

We may think it to be sufficiently strange in tracing the early history of the art of carving or engraving in ivory, that we should be able easily to carry it, upon the evidence of extant examples, to an antiquity long before the Christian era: through the Roman, Greek, Assyrian, and Jewish people, up to an age anterior to the origin of those nations by centuries, the number of which it may be difficult accurately to count. These very ancient examples are of the earliest Egyptian dynasties: yet, between them and the date of the earliest now known specimens of works of art incised or carved in ivory there is a lapse of time so great that it may probably be numbered by thousands of years.

We must go back to prehistoric man for the proof of this; to a period earlier than the age of iron or of bronze; to the first—the drift—period of the stone age. We must go back, as Sir John Lubbock writes, “to a time so remote that the reindeer was abundant in the south of France, and probably even the mammoth had not entirely disappeared.” Lartet and Christy also (in their valuable publication, [Pg 7] the Reliquiæ Aquitanicæ) make a like remark: “It rests with the geologist, by indicating the changes which have occurred in the very land itself, to shadow out the period in the dim distance of that far antiquity when these implements, the undoubted work of human hands, were used and left there by primæval man.”

Within the last few years, in caves at Le Moustier and at La Madelaine in the Dordogne, numerous fragments have been found of tusks of the mammoth and of reindeer’s bone and horn, on some of which are incised drawings of various animals, and upon others similar representations carved in low relief. These objects have been engraved in several works by geologists and writers upon the important questions relating to prehistoric people; and copies of them may be found in Sir John Lubbock’s book, “The origin of Civilization,” already quoted from. Among them are drawings and carvings of fish, of a snake, of an ibex, of a man carrying a spear, of a mammoth, of horses’ heads, and of a group of reindeer.

Sir John Lubbock describes these works as showing “really considerable skill;” as “being very fair drawings;” as the productions of men to whom we must give “full credit for their love of art, such as it was.” But to speak of them in words so cold is less than justice. No one can examine the few fragments which as yet have been discovered without acknowledging their merit, and attributing them to what may very truly be called the hand of an artist. There can be no mistake for a moment as to many of the beasts which are represented.

Again: the sculptor has given us, in a spirited and natural manner, more than one characteristic quality of his subject: and we can recognise the heaviness and sluggishness of the mammoth as easily as the grace and activity of the reindeer. The results of the workman’s labour are not like the elephants and camels and lions of a child’s Noah’s ark—merely bodies with heads and four legs—but they are executed with the right feeling and in an artistic spirit: the animals [Pg 8] are carefully drawn, and often with much vigour. There is nothing conventional about them; they are far beyond and utterly different in style from the ugly attempts of really civilised people, such as the Peruvians or Mexicans, to say nothing of the works of the savages of Africa or New Zealand. They are true to nature.

The aboriginal nations of North and South America must certainly be spoken of as civilised, though it is curious to remember how great authorities seem to differ as to what civilisation means. Macaulay, in his Life of lord Clive, writing with a recklessness of statement not unusual with him when aiming at some picturesque contrast, describes the ancient Mexicans as “savages who had no letters, who were ignorant of the use of metals, who had not broken in a single animal to labour, and who wielded no better weapons than those which could be made out of sticks, flints, and fishbones, and who regarded a horse-soldier as a monster.” But Bernal Diaz, whose report as an eye-witness has stood the test of years of later investigation and dispute, describes the appearance of the great cities from without as like the enchanted castles of romance, and full of great towers and temples. And within, “every kind of eatable, every form of dress, medicines, perfumes, unguents, furniture, lead, copper, gold, and silver ornaments wrought in the form of fruit, adorned the porticoes and allured the passer-by. Paper, that great material of civilisation, was to be obtained in this wonderful emporium; also every kind of earthenware, cotton of all colours in skeins, &c. There were officers who went continually about the market-place, watching what was sold, and the measures which were used.”

If we are to take the judgment of Lord Macaulay as our guide in determining what may be true civilisation, we must set down the Greeks in the reign of Alexander, or the Italians in the days of Leo the tenth, as “savages,” because they were ignorant of the electric telegraph; or ourselves now, because we cannot guide balloons through the air.

The sculptures and works of art in the ruined cities of Yucatan are also [Pg 9] to be thought of. Many engravings of them are given in Stephens’s central America.

Nor is it enough to say that the prehistoric carvings are merely true to nature. Their merit is clearly seen when compared with the plates of Indian drawings and picture writings in Schoolcraft’s history of the Indian tribes of the United States: or again, of a different character altogether, the illuminations in Indian and Persian manuscripts. In some respects these last are of the highest quality as regards execution, but the animals are generally drawn in a manner purely conventional, with scant feeling of truth or beauty, and little power of expressing it.

In short, the prehistoric carvings are from the hands of men who were neither beginners nor blunderers in their art. The practised skill of a modern wood engraver would scarcely exceed in firmness and decision, nor in evident rapidity of execution, the outline of the animals in the example which is here engraved.

Other illustrations are given in order that the reader may compare [Pg 10] them, and more especially those also just referred to above, with a woodcut (on preceding page) of drawings incised upon bone by Esquimaux of our own days. This has been chosen because there seems to be a general disposition, in the way of theory, to compare the dwellers in the caves of Dordogne and the men of the stone age with the Esquimaux, and to limit, as it were, the unknown amount of civilisation in the one by what we have learnt from our own experience of the latter. Yet, so far as the drawings and the sculptures are concerned, there is scarcely room for comparison. The work of the stone age is that of a people with whom, if they were in all other respects savages, we have no modern parallel. The work of the Esquimaux is that of men who imitate with the hand of a child, and the success or power of whose imitation ranges exactly with their advance and culture (if culture it may be called) in other arts.

The first of these illustrations is perhaps the best, as it is certainly the most delicate and graceful of all the fragments yet discovered. It represents the profile of the head and shoulder of an ibex, carved in low relief upon a piece of the palm of a reindeer’s antler. So exact and well characterised is the sculpture, that naturalists have no hesitation in deciding the animal to be an ibex of the Alps, and not of the Pyrenees.

The next is a group of reindeer drawn upon a piece of slate. [Pg 11]

And lower down the page, incised upon a piece of mammoth ivory, are outlines of the mammoth itself. The original, rather more than nine inches in length, is at Paris in the museum of the Jardin des plantes.

There is no discovery with respect to primæval man—his powers and [Pg 12] capabilities, his possible enjoyments and appreciation of the beautiful, his certain infinite elevation as a reasonable being above the beasts of the field, in the most distant age and period to which his existence has been traced,—so full of interest, so full as yet of unfathomed mystery, as these wonderful works in ivory and bone. It can scarcely be supposed that, by a happy accident, we have lighted on the only specimens which were ever executed of such great merit; or that there were some two or three men only who for a brief time in the stone age, by a sort of miracle, were able to produce work so excellent. Further researches and a few more fortunate “finds” may enable us to learn much more than we now know of other habits, and the state of (what we call) the barbarism of those ancient races in other respects. Nor must we forget that for numberless generations after these men had passed away their descendants lost all the old power and skill. “Dark ages” came, similar (although incomparably longer in duration) to those which followed Greek or Roman civilisation and science from the sixth to the ninth and tenth centuries after Christ. Again quoting Sir John Lubbock, we know that “no representation, however rude, of any animal has yet been found in any of the Danish shell mounds. Even on objects of the bronze age they are so rare that it is doubtful whether a single well-authenticated instance could be produced.” “Even curved lines” upon the rude and coarse pieces of pottery of later ages “are rare.” Once more: “Very few indeed of the British sepulchral urns, belonging to ante-Roman times, have upon them any curved lines. Representations of animals are also almost entirely wanting.”

Further discussion and speculation upon this subject would here be out of place. We must leave it, although with great regret. We must pass at one bound to a later period of time which, however long ago it may seem to us looking back upon it, is nevertheless, in comparison with the supposed date of the men who left their ivory and bone carvings in the caves of Aquitaine, positively modern.

Although the narrative of the sacred Scriptures does not, with the exception of the first eleven chapters of Genesis, reach back so far as the known history of the kingdom of Egypt, it may be best to mention, first, some places in the Old Testament in which reference is made to works in ivory.

King Solomon, we are told, “made a great throne of ivory, and overlaid it with the best gold.” “The ivory house which Ahab made,” is particularly mentioned among his memorable acts. The Psalmist speaks of garments brought “out of ivory palaces,” or from what may rather be translated wardrobes. The original text is ﬤﬢﬣיﬤﬥישׁן. In the earlier Hebrew the word ﬣיﬤﬥ meant a small house or palace; in the later,—and the 45th Psalm is not of early date, and was moreover written in a foreign country,—it meant more commonly a wardrobe, or what we now call a vestry or sacristy. The prophets Ezekiel and Amos tell us of “benches of ivory brought out of the isles of Chittim,” of “horns of ivory,” and of “beds of ivory.” There are other evidences in the Bible of the value and high estimation in which ivory was held by the Jews; and its beauty of appearance, its brightness, and smoothness are used as poetical illustrations in the Song of Solomon. From a verse in the fifth chapter of this last book we also learn that the ivory was sometimes inlaid with precious stones.

It is quite evident that in those days works in ivory were regarded in [Pg 14] Judæa as a possession only to be acquired by very great and wealthy persons; nor may it be too much, perhaps, to say that they were looked upon as insignia of royalty. We may entirely agree with De Quincy, in his book upon the statue of Jupiter at Olympia: “L’ivoire constitua les ornaments distinctifs de la dignité royale chez les plus anciens peuples. L’antiquité ne parle que de sceptres et de trônes d’ivoire. Tels étaient selon Denis d’Halicarnasse les attributs de la royauté chez les Étrusques. A leur exemple, Tarquin eut le trône et le sceptre d’ivoire, &c.”

But, as has been already observed, there are specimens and remains of Egyptian works in ivory still existing which date by many centuries from an earlier time than the days of Solomon or Ahab. These must be, of course, of excessive rarity: partly because of their antiquity and fragile nature; partly because of the smallness of their size, owing to which they must have been frequently overlooked or thrown aside. The collection in the British museum includes some examples, a few of which, particularly two daggers inlaid and ornamented with ivory, are of the time of Moses, about 1,800 years before Christ. Several chairs, ornamented in a like manner, may be attributed to the sixteenth century b.c. Some woodcuts are given of chairs and stools ornamented with ivory, in Sir Gardner Wilkinson’s account of the ancient Egyptians.

Among the Egyptian antiquities in the British museum may also be mentioned the handle of a mirror in hippopotamus ivory; an ivory palette of about the same period; two ivory boxes, in the shape of water fowl; and a very remarkable figure or statuette, a woman, of perhaps the eleventh century b.c.; and, again, a very curious casket of considerable size but of much later date; probably of the first century of the Christian æra: Roman work and decoration. This was found at Memphis, and is made of ivory plaques laid upon a framework of wood. The plaques are incised with figures and coloured. The shape is oblong, with a sloping cover; it measures about twelve by ten inches. [Pg 15]

The use of ivory for ornament and the adapting it to works of art must have been known by the Egyptians from a most remote antiquity. There is a small ivory box in the Louvre, which is inscribed with a prænomen attributed to the fifth dynasty. Labarte, quoting De Rougé, mentions another of the sixth dynasty:—“On voit au musée Égyptien du Louvre une quantité d’objets d’os et d’ivoire. Ce sont de petits vases, des objets de toilette, des cuillers dont le manche est formé par une femme nue, et une boîte ornée d’une belle tête de gazelle. La pièce la plus curieuse est une autre boîte d’ivoire très-simple, mais d’une excessive antiquité, puisqu’elle porte la légende royale de Merien-ra, qui est placé vers la sixième dynastie.” Dr. Birch in a paper printed among the transactions of the Royal society, on two Egyptian cartouches found at Nimroud, refers to a tablet of the twelfth dynasty, which describes a figure whose “arms are to be made of precious stones, silver and gold, and the two hinder parts of ivory and ebony. In a tomb at Thebes record is made of a statue composed of ebony and ivory, with a collar of gold.”

The date of the Egyptian statuette in the British museum and of numerous smaller objects in that and in the great foreign collections, such as spoons, bracelets, collars, boxes, &c., most of which are earlier than the twenty-fourth dynasty and long before the time of Cambyses, brings us to about the same period as the famous Assyrian ivories, which were found at Nineveh, and which are also preserved in the British museum.

These were chiefly discovered in the north-west palace; and almost all in two chambers of that building. We cannot do better than listen to the general description of them given by Mr. Layard himself:—“The most interesting are the remains of two small tablets, one nearly entire, the other much injured. Upon them are represented two sitting figures, holding in one hand the Egyptian sceptre or symbol of power. Between them is a cartouche containing hieroglyphics, and surmounted by a plume, such as is found in monuments of the eighteenth and subsequent [Pg 16] dynasties of Egypt. The chairs on which the figures are seated, the robes of the figures themselves, the hieroglyphics and the feather above, were enamelled with a blue substance let into the ivory, and the whole ground of the tablet, as well as the cartouche and part of the figures, was originally gilded,—remains of the gold leaf still adhering to them. The forms and style of art have a purely Egyptian character, although there are certain peculiarities in the execution and mode of treatment that would seem to mark the work of a foreign, perhaps an Assyrian, artist. The same peculiarities, the same anomalies, characterise all the other objects discovered. Several small heads in frames, supported by pillars or pedestals, most elegant in design and elaborate in execution, show not only a considerable acquaintance with art, but an intimate knowledge of the method of working in ivory. Scattered about were fragments of winged sphinxes, the head of a lion of singular beauty, human heads, legs and feet, bulls, flowers, and scroll work. In all these specimens the spirit of the design and the delicacy of the workmanship are equally to be admired.”

There are altogether more than fifty of these Assyrian ivories in the British museum: a detailed account of nearly all is given by Mr. Layard in the appendix to his first volume. Dr. Birch says they cannot be later in date than the seventh century b.c.; and thinks it highly probable that they are much earlier. Mr. Layard believes that about the year 950 b.c. is the most probable period of their execution.

There can be no doubt that from the year 1000 b.c. down to the Christian æra there was a constant succession of artists in ivory in the western Asiatic countries, in Egypt, in Greece, and in Italy. Long before ivory was applied in Greece to the making of bas-reliefs and statues it was employed for a multitude of objects of luxury and ornament. Inferior to marble in whiteness, and of course greatly inferior in extent of available surface, ivory exceeds marble in beauty of polish and is less fragile, being an animal substance and of true [Pg 17] tissue and growth. From the time of Hesiod and Homer numerous allusions are to be found in classic authors to various works in this material: such as the decoration of shields, couches, and articles of domestic use. As to statues, Pausanias tells us that, so far as he could learn, men first made them of wood only; of ebony, cypress, cedar, or oak. The passages from the earlier classics have been referred to, over and over again, by all the later writers on the subject; and it would be not merely wearying but unnecessary to repeat them here.

In the sixth century before Christ, ivory statues of the Dioscuri and other deities were made at Sicyon and Argos. Sir Digby Wyatt, in the lecture before referred to, speaks of them as having been rude in character, but there is no evidence left for so disparaging a decision. Other works were statues of the Hours, of Themis, and of Diana. The names of some of the sculptors have been preserved: among them Polycletus, Endoos of Athens, the brothers Medon, and Dorycleides.

The style in which objects of this kind were executed was called Toreutic: from τορεύω, to bore through, to chase, to work in relief; signifying chiefly working the material in the round or in relief. Winckelman, in his history of art, explains the term at first with insufficient exactness: “Phidias inventa cet art appelé par les anciens toreutice, c’est à dire, l’art de tourner.” In his second edition he corrects this, and rightly says, “la racine de cette dénomination est τορός, clair, distinct, épithète qui s’applique à la voix. C’est pourquoi on donne ce nomme au travaux en relief, par opposition au travail en creux des pierres précieuses.” A long disquisition on the meaning of the word, and its etymology, is given by De Quincy.

One of the most famous of such toreutic works, and of which Pausanias has left us a tolerably accurate description, was the coffer which the Cypselidæ sent as an offering to Olympia, about 600 b.c. It seems to have been made of cedar wood, of considerable size; the figures ranged in five rows, one above the other, along the sides which [Pg 18] were inlaid with gold and ivory. The subjects were taken from old heroic stories. De Quincy has given a large plate with a conjectural restoration of the chest; which he supposes to have been oblong with a rounded cover. Others believe it to have been elliptical.

Pausanias, in his description of Greece, mentions the existence in his time of numerous ivory statues and of chryselephantine works. In the first section of the seventeenth chapter of the fifth book he enumerates ten or fifteen, which he says were all made of ivory and gold; and a table of ivory. At Megara he saw an ivory statue of Venus, the work of Praxiteles; at Corinth, many chryselephantine statues; near Mycenæ, a statue of Hebe, the work of Naucydes; in Altis, the horn of Amalthea; and in another treasury there, a statue of Endymion entirely of ivory, except his robe; at Elis, a statue made of ivory and gold, the work of Phidias; near Tritia, in Achaias, an ivory throne with the sitting figure of a virgin; at Ægira, a wooden statue of Minerva of which the face, hands, and feet were ivory. And, to name no more, a statue of Minerva, the work of Endius, all of ivory, long preserved at Tegea, but at the time when he wrote placed at the entrance of the new forum at Rome, having been taken there by Augustus.

There are two men whose travels and the sights they saw we cannot but envy; one was Pausanias, the other our own Leland.

It should be observed that Pausanias believed ivory to be the horn and not the tooth of the elephant: and he has a long argument about it in his fifth book, where he refers to and mentions the Celtic stag. Declaring it to be horn, he says that, like the horns of oxen, ivory can be softened by fire and changed from a round to a flat shape.

The famous chryselephantine statues of Phidias and his contemporaries were somewhat later than the statues of the Dioscuri and the chest at Olympia. One of the most celebrated was the figure of Minerva in the Parthenon, which was in height nearly forty English feet. It would be [Pg 19] wrong to omit all notice of the attempt to reproduce this statue which was made by order of the late Duc de Luynes, and was shown in the Paris Exhibition of 1855. “M. Simart, qui l’a exécutée, s’est montré le digne interprète de Phidias, et a su retrouver, par ses études approfondies, le vrai sentiment de l’art antique. La statue, de trois mètres de hauteur, est d’ivoire et d’argent: la face, le cou, le bras et les pieds, la tête de Méduse placée sur son égide, ainsi que le torse de la Victoire qu’elle tient dans la main droite, sont d’ivoire de l’Inde. La lance, le bouclier, le casque, et le serpent sont de bronze; la tunique et l’égide d’argent ont été repoussées et ciselées.”

Even more colossal than the figure of Minerva was the Jupiter at Olympia; the god was represented sitting, and reached to the height of about fifty-eight feet. De Quincy has some conjectural restorations of this statue engraved in his book.

We remember the destruction of these and similar works with the utmost regret; and the more so, because that destruction was owing in many instances to the mad violence of Christian fanatics; the iconoclasts of the eighth century. The remains which we possess even of smaller objects are not only of excessive rarity, but they cannot with any certainty be attributed to artists working in Greece itself. Ivory and metal have perished under conditions which have left uninjured fragile vases. There are some examples of carvings in ivory in the British museum, and especially in the collection lately purchased from signor Castellani which have been found in Etruscan tombs. Many of these are perhaps the work of Greek artists.

Etruscan sculpture was probably derived at first from Egypt: but the art of the one was entirely and unchangingly conventional, and never seems to vary from a certain fixed style. The Etrurian, on the contrary, soon cleared itself from the bondage of old traditions and, even when rudest, was free and attempted to imitate nature in the representation of muscles, hair, and draperies. [Pg 20]

Neither the beauty nor the wonderful spirit of the execution of some of the ivories in the British museum has been exceeded or perhaps equalled in any later time. Among them the following ought to be particularly mentioned:—

A large bust of a woman, of the Roman republican period, and a small carving of the head of a horse, scarcely inferior to the work of any Greek artist of the best time. A very important head of a Gorgon, as seen on Athenian coins, with eyes inlaid in gold, about two inches in diameter; probably the button of a woman’s dress. Two lions, the heads and part only of the bodies, lying across each other, very admirable and full of character; and another lion’s head, the top perhaps of the handle of a mirror. These were chiefly discovered, with numerous other fragments, at Chiusi and Calvi. At Chiusi also were found the panels of two small caskets which have been put together; both are of early date; one it may be of the fourth century b.c. and Phœnician in style. There is also in the same case a fine small ivory statuette, much later, perhaps of the second century: a boy, still partly embedded in the mortar or refuse in which it was found.

The workers in ivory during the first centuries of our æra were, as a class, sufficiently numerous to be exempted by law from some personal and municipal obligations. Pancirolus, in his “Notitiæ,” gives a list of these bodies of artificers. He mentions as exempt, architects, medical men, painters, and others, with references to the various laws under which they were excused; and among them are “workmen in ivory, who make chairs, beds, and other things of that sort.”

Nevertheless, carvings in ivory of the Roman imperial times before Constantine are extremely scarce. In the superb collection in the South Kensington museum there are two only which can safely be so attributed. One is the fragment, no. 299; the other is the beautiful leaf, no. 212.

The British museum (not to mention a large number of fragments chiefly [Pg 21] of caskets or decorations of furniture, tesseræ and tickets of admission to theatres and shows, dice, and the like) possesses a few pieces, of which one is extremely fine in character and in good preservation. The subject is Bellerophon, who is represented on Pegasus, killing the Chimæra; and it is executed in open work. The age is somewhat doubtful. Professor Westwood places it as early as the third century, and his judgment must be treated with great deference. Others, of no slight authority, are indisposed to give it an earlier date than the fourth century. This admirable ivory has somewhat of the character of the book-cover in the Barberini collection, engraved by Gori, in the second volume of his great work on diptychs. That famous piece is not perfect, nor is there any name upon it. Gori fairly argues that it represents the emperor Constantius, about the year 357. The Bellerophon is of finer work.

The gradual and uninterrupted decline of art from the days of Augustus is to be traced as distinctly in the ivories which have been preserved as in ancient buildings. But we can scarcely agree with D’Agincourt as regards its rapidity. Speaking of sculpture generally, he says: “On vit celle-ci successivement grande, noble, auguste sous le prince qui mérita ce nom; licencieuse et obscène sous Tibère; grossièrement adulatrice sous Caracalla; extravagante sous Néron, qui faisait dorer les chefs-d’œuvre de Lysippe.” D’Agincourt probably refers to the barbarism of Caligula, who proposed to put a head of himself upon the Olympic Zeus by Phidias; or to Claudius, who cut the head of Alexander out of a picture by Apelles, to replace it with his own. Suetonius has recorded the first of these atrocities (can we speak of them by a lighter name?) and Pliny the last.

In the collection given to the town of Liverpool by Mr. Mayer there are two very celebrated pieces, possibly of the third century; they were originally the leaves of a diptych. On one is Æsculapius, on the other Hygieia.

From the middle of the fourth century down to the end of the sixteenth we have an unbroken chain of examples still existing. Individual pieces may, perhaps, in many instances be of questionable origin as regards the country of the artist, and, sometimes, with respect to the exact date within fifty or even a hundred years. But there is no doubt whatever that, increasing in number as they come nearer to the middle ages, we can refer to carved ivories of every century preserved in museums in England and abroad. Their importance with reference to the history of art cannot be overrated. There is no such continuous chain in manuscripts, or mosaics, or gems, or textiles, or porcelain, or enamels. Perhaps, with the exception of manuscripts, there never was in any of these classes so large a number executed nor the demand for them so great. The material itself or the decorations by which other works were surrounded very probably tempted people to destroy them; and we may thank the valueless character of many a piece of carved ivory, except as a work of art, for its preservation to our own days.

The most important ivories before the seventh century are the consular diptychs. The earliest which still exists claims to be of the middle of the third century, the latest belongs to the middle of the sixth. Anything doubled, or doubly folded, is a diptych: δίπτυχον; but the [Pg 23] term was chiefly applied to the tablets used for writing on with metallic or ivory styles by the ancients. When these tablets had three leaves they were called triptychs, and of five or more leaves pentaptychs or polyptychs. Inside, each leaf was slightly sunk with a narrow raised margin in order to hold wax; outside, they were ornamented with carvings. They were not always of ivory; frequently of citron or of some less costly wood, and for common use were probably of small size, convenient for the hand and for carrying about.

Homer, in the sixth book of the Iliad, speaks of such tablets, and there are frequent references to them in Latin writers; in Juvenal, Martial, and other authors. Many passages are to be found quoted in books upon the ancient Roman diptychs. It happens also that two ancient specimens have been found. Both were discovered in gold mines in Transylvania, and have been described by Massmann in a volume published at Leipsic in 1841. Each consists of three leaves, one of fir-wood, the other of beech, and about the size of a modern octavo book. The outer part exhibits the plain surface of the wood, the inner part is covered with wax surrounded by a margin. The edges of one side are pierced that they might be fastened together by means of a thread or wire passed through them. The wax is not thick on either set of tablets; it is thinner on the beechen set, in which the stylus of the writer has in places cut through the wax into the wood. There is manuscript still remaining on both of them: the beginning of the beechen tablets containing some Greek letters. The writing on the other is in Latin, a copy of a document relating to a collegium. The name of one of the consuls is given, determining the date to be a.d. 169. An abridged account of these very curious tablets is given in Smith’s “Dictionary of antiquities” under the word “tabulæ.”

The consular diptychs were of much larger size than those made for everyday use: generally about twelve inches in length by five or six in breadth. Diptychs of this kind were part of the presents sent by new consuls on their appointment to very eminent persons; to the senators, [Pg 24] to governors of provinces, and to friends. Each consul probably sent many such gifts, and duplicates of more than one example have been preserved. These naturally varied greatly, not only in the workmanship but in the material. For persons in high station or authority the diptychs would be carved by the best artists of the time, and if not made entirely of some metal very costly and valuable the material would be ivory, perhaps also mounted in gold. As we find in the fifth book of the letters of Symmachus (consul, a.d. 391), “Domino principi nostro auro circumdatum diptychon misi, cæteros quoque amicos eburneis pugillaribus et canistellis argenteis honoravi.” For others of lower rank or for dependents, they would be roughly finished and of bone or wood.

It is to the custom of sending these diptychs to people of rank in the provinces that we owe the preservation of some still extant, and which have been kept in the country into which they came by gift or otherwise in very early times. Generally, in somewhat later days, they were given or bequeathed to churches; and, having been first used in the public services, were afterwards laid by in their treasuries.

Inside these official diptychs the wax may have been inscribed with the Fasti Consulares or list of names of all preceding consuls, closing with that of the new magistrate, the donor. As Ausonius, himself consul in the year 379, says in one of his epigrams:

This, however, as a rule, is matter of conjecture. Outside, the leaves were carved with various ornaments; sometimes with scrolls, or cornucopiæ, or the bust of the new consul in a medallion. Sometimes—and as the diptychs which we now possess repeat this style the most frequently we may conclude it to have been the usual practice [Pg 25] at least for the more important of those presented—the consul was represented at full length and sitting in the cushioned curule chair: one hand often being uplifted and holding the mappa circensis. He is clothed in the full ceremonial vestments of his office, as used when he was inducted into it. The dress itself seems to be a splendid imitation of that worn by the old generals at the celebration of a triumph; a richly embroidered cloak (toga picta) with ample folds, beneath which is a tunic striped with purple (trabea) or figured with palm leaves (tunica palmata). On his feet are shoes of cloth of gold (calcei aurati), and in one hand the consular staff or sceptre (scipio) surmounted by an eagle or an image of Victory.

The conspicuous representation of a cushion on the seat of the chair is probably not to be overlooked as of small signification or importance. Cushions were permitted only to certain privileged classes during the games of the circus; and Caligula conceded the use of cushions to senators as a graceful compliment at the beginning of his reign.

Some will remember also the advice given by Ovid, in his “Art of Love,” to the lover in attendance on his mistress in the theatre or at public games (he had just before been speaking of the ivory statues carried in the procession):

Not unusually in the lower part of each leaf, in a separate compartment, were representations of the shows which the consul intended to give, of the manumission of slaves, and of the presents, money, bread, &c., which were also to be distributed among the people.

The series of consular diptychs, having each of them in many cases a known date, is of essential value and importance in the history of art, whilst the fashion of them lasted. Similar as they are one to another [Pg 26] in certain respects, nevertheless there is a considerable variety of treatment and undoubtedly various degrees of excellence or inferiority of style and execution. When so many would be required by the consul of the year, it was impossible that all could be made by good artists, and probably one or two of the best kind were roughly copied by common workmen. It was sufficient if the general character, dress, or special ornament of the consul were represented.

Rapidly as art declined during the three centuries after the birth of Constantine, as shown especially in these consular diptychs, we may nevertheless trace a certain grandeur in the figures and in the attitudes which show that earlier and better models of antiquity were still followed by the sculptors. Labarte further observes that the diptychs carved at Constantinople were far superior to those which were made in Italy.

Many of these diptychs are identified by the name of the consul which is carved across the top of one leaf; the full legend generally running across both being equally divided. It has been said that these legends (as well as portions of the sculpture) were sometimes coloured red. We know no extant example, but the following passage from Claudian is important, and not on that particular point alone:

We usually find also a profusion of proper names, according to the fashion and taste of the court of Constantinople and of the last years of the consulate. Following these names was a formula which expressed the style and dignities: “Vir illustris, comes domesticorum equitum, et consul ordinarius.” The “vir illustris” signified that the new consul [Pg 27] had either filled or was of rank great enough to fill high official positions in the state. The “comes domesticorum equitum” was his title as commander of the bodyguard of the emperor. The “consul ordinarius” declared the true consular dignity itself.

Some of the consular diptychs also add the names of the persons or communities to whom they were sent. Thus, the diptych of Flavius Theodorus Philoxenus, a.d. 525, has the following inscription in Greek iambics, part upon one tablet, part upon the other: “I, Philoxenus the consul, offer this gift to the wise senate.”

Another diptych of Flavius Petrus, a.d. 516, has this inscription within a large circle: “I, the consul, offer these presents, though small in value, still ample in honours, to my [senatorial] fathers.” This is given by M. Pulszky, in his essay on antique ivories. The same writer quotes the often-cited decree of the emperor Theodosius; by which, because of the honour attached to the receiving of these diptychs, the presenting of them by anyone but the ordinary consuls was forbidden. The law ought not to be omitted here: “Lex xv. Codex Theodosianus, tit. xi. De expensis ludorum. Illud etiam constitutione solidamus, ut exceptis consulibus ordinariis, nulli prorsus alteri auream sportulam aut diptycha ex ebore dandi facultas sit. Cum publica celebrantur officia, sit sportulis nummus argenteus, alia materia diptycha.”

During the period when these ivory diptychs were in use or fashion, that is (so far as we know) from the first or second centuries to the sixth, the office of consul was entirely in the hands of the emperors, who conferred it on whom they would, and assumed it themselves as often as they thought fit. Augustus was consul thirteen times; Vitellius proclaimed himself perpetual consul; Vespasian eight times; and Domitian seventeen. The consuls, therefore, gradually became mere ciphers in the state. It is true that they presided in the senate and on other public occasions with all the ancient forms; and the mere [Pg 28] title, down to the extinction of the western empire, was nominally the most exalted and honourable of all official positions.

The most complete list which we have of the existing consular diptychs is given by professor Westwood in a carefully written paper read before the Oxford architectural society, and printed in their proceedings for 1862. These are supposed to have been all identified, and, in most instances, by the inscription on the ivory. Nevertheless, we must still acknowledge to a grave doubt about more than one:—

| A.D. | ||

| 1. | M. Julius Philippus Augustus. In the Meyer collection at Liverpool. One leaf | 248 |

| 2. | M. Aurelius Romulus Cæsar. In the British museum. One leaf | 308 |

| 3. | Rufius Probianus. At Berlin. Both leaves | 322 |

| 4. | Anicius Probus. In the treasury of the cathedral of Aosta. Both leaves | 406 |

| 5. | Flavius Felix. Bibliothèque Impériale, Paris. One leaf | 428 |

| 6. | Valentinian III. In the treasury of the cathedral of Monza. Both leaves | 430 |

| 7. | Flavius Areobindus. At Milan, in the Trivulci collection. Both leaves | 434 |

| 8. | Flavius Asturius. At Darmstadt. One leaf | 449 |

| 9. | Flavius Aetius. At Halberstadt. One leaf | 454 |

| 10. | Narius Manlius Boethius. In the bibl. Quiriniana at Brescia. Two leaves | 487 |

| 11. | Theodorus Valentianus. At Berlin. Both leaves | 505 |

| 12. | Flavius Dagalaiphus Ariobindus. At Lucca; both leaves. At Zurich; both leaves. | |

| And in private possession at Dijon; one leaf | 506 | |

| 13. | Flavius Taurus Clementinus. In the Meyer collection at Liverpool. Both leaves | 513 |

| 14. | Flavius Petrus Justinianus. Bibliothèque Impériale, at Paris; one leaf. | |

| And at Milan, in the Trivulci collection; both leaves | 516 | |

| 15. | Flavius Anastasius Paulus Probus Pompeius. At Berlin; one leaf. | |

| The other leaf in South Kensington museum. | ||

| Bibliothèque Impériale, Paris; both leaves. And Verona; one leaf | 517 | |

| 16. | Flavius Paulus Probus Magnus. Two in the Imperial library at Paris; each one leaf. | |

| Another, so attributed, in the Mayer collection at Liverpool; one leaf | 518 | |

| 17. | Flavius Anicius Justinus Augustus. At Vienna; one leaf | 519 |

| 18. | Flavius Theodorus Philoxenus. Bibliothèque Impériale, Paris; both leaves. | [Pg 29] |

| And in the Mayer collection; one leaf; very doubtful | 525 | |

| 19. | Flavius Anicius Justinianus Augustus. At Paris | 528 |

| 20. | Rufinus Orestes. South Kensington museum. Both leaves | 530 |

| 21. | Anicius Faustus Albinus Basilius. In the Uffizii, at Florence; one leaf. | |

| The companion leaf is in the Brera, at Milan | 541 | |

A few remarks may be of use to the student with reference to some of these important diptychs. The leaves of no. 3 now form the covers of a manuscript life of St. Ludgerus. This diptych is erroneously named by Labarte as the most ancient known to exist.

Of no. 5, the other leaf was lost or stolen during the French revolution of 1792.

Mr. Oldfield, a very high authority, suggests that no. 6 should be given to Valentinian II., in which case the date would be about a.d. 380. The earlier date is supported by the great beauty and admirable execution of the diptych.

No. 7 has no inscription: it bears a monogram which contains all the letters of the name Areobindus. It is engraved in the Thesaurus of Gori.

No. 8 was formerly in the church of St. Martin at Liége, and it was long supposed to be lost. Professor Westwood, however, has found the greater portion of one leaf, used as the cover of a book of the gospels in the royal library at Darmstadt. This, probably, is not a fragment of the Liége diptych, but of another of the same consul. The two leaves are engraved in Gori.

A folio volume of more than 200 pages was edited by Hagenbuch in 1738, containing a number of learned essays on the diptych of Manlius Boethius, no. 10. It has at the beginning engravings of both leaves: and the consul is represented on one in a standing position; on the other, sitting and holding the mappa in his right hand. The inscription is unusually obscure: how much so may be judged from the [Pg 30] fact that the editor of the book has collected more than half a dozen different interpretations of it. Some of them are amusing. The inscription on one leaf runs thus: NARMANLBOETHIVSVCETINL, on the other, EXPPPVSECCONSORDETPATRIC. The members of the Academy at Paris, to whom the difficulty had been referred, proposed to read “Natales regios Manlius Boethius vir clarissimus et inlustris ex propria pecunia voto suscepto edixit celebrandos consul ordinarius et patricius.” But a more probable reading is, “Narius Manlius Boethius vir clarissimus et inlustris, expræfectus prætorio, præfectus, et comes, consul ordinarius et patricius.” Again, against this last some have disputed that the PPP meant three times prefect, and CC twice consul.

We must remember that artists in ivory were driven, because of the narrow limits at their disposal, to use extreme forms of contractions and symbols, scarcely intelligible even in their own time, instead of words: far more so, indeed, than were the carvers of inscriptions upon monumental stones, altars, and sarcophagi.

Professor Westwood leaves the date of no. 11 doubtful: it is remarkable, as representing in a medallion, between the busts of the emperor and empress, the head of Christ with a cruciferous nimbus.

The Paris diptych of the consul Anastasius was long known as the diptych of Bourges, under which name it is well engraved in Montfaucon’s “Antiquities”: and no. 18 as the diptych of Compiegne; having been given by Charles the Bald in the ninth century to the abbey church of St. Corneille, where the leaves were preserved until its destruction in 1790, and were then transferred to Paris. The diptych is admirably figured in the Trésor de numismatique et de glyptique of Lenormant, who refers also to previous writers on this diptych.

Basilius, consul of Constantinople, whose name is attached to no. 21, was the last of the long and illustrious line of consuls. They had [Pg 31] continued, with a few short interruptions of the tribunes, for more than a thousand years. After Basilius, the emperors of the East took the title, until at length it fell into oblivion. The last consul of Rome was Decimus Theodorus Paulinus, a.d. 536. The second leaf of this diptych has been identified by professor Westwood: M. Pulszky believed it to have been lost. It is but a fragment of the right wing of the diptych, the upper half. Gori gives figures of both leaves: he decides against their being of the same pair. Mr. Westwood, however, says that “it is certainly the companion” to the leaf in the Uffizii.

A detailed description and arguments about many of these diptychs will be found in the dissertations printed by Gori in his Thesaurus. Other authorities are Du Cange, Mabillon, and Montfaucon. Their statements have been ably and briefly summed up in the very interesting paper already mentioned, read before the architectural society of Oxford, by professor Westwood; and by M. Pulszky in his essay on antique ivories.

A Roman diptych, undescribed, is preserved at Tarragona in Spain, and it is extremely probable that a careful search amongst the treasures still remaining in the churches of that country would discover others. The very learned editor of the Thesaurus of Gori (writing more than a hundred years ago) says: “Suspicio enim invaluit in locupletissimis Hispaniæ sacrariis, quo totius fere orbis donaria confluxerunt, multa hujusmodi abscondi, quæ nusquam adhuc comparuere, quia hactenus nec perquisita nec curata.”

There are several very important Roman diptychs and leaves of diptychs, not consular, still extant; some also of greater beauty than any of the examples in the preceding list. Among them is the diptych (already mentioned) of Æsculapius and Hygieia in the Mayer collection at Liverpool; and another, but smaller, of the same subject in a private collection in Switzerland. This last is described by professor Westwood, who possesses a cast of it, as “in much deeper relief than the Fejérváry diptych, and full of energy in the design. Here Æsculapius holds a palm-branch in his right hand, and supports his club, round which a serpent is twined, with his left; whilst Hygieia holds a snake in her right hand and, apparently, a large melon in her left.” Another is the diptych of cardinal Quirini now at Brescia, having on one leaf, as interpreted by M. Pulszky, Phædra and Hyppolytus; and on the other Diana and Virbius. This is probably of the third century.

Another is the famous diptych, long known as the Tablets of Sens, but now at Paris in the Imperial library and forming the covers of a thirteenth century manuscript, containing “The Office of fools,” or, rather, the Office of the feast of the circumcision. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries some childish and improper jests and plays were allowed in churches on the first day of the year. This “Office of fools” seems to have been a complete arrangement for the day; with [Pg 33] mass, matins, and hours. The whole affair was something like (but without the reverential decorum) the festival of the boy-bishop, celebrated in more than one of our English cathedrals about the same period, and was probably a relic of the heathen Saturnalia.

These tablets, which are somewhat similar in style to the sarcophagi of the third century, are engraved by Labarte in his album. On one leaf is represented Bacchus in a car drawn by centaurs; on the other is Diana in a chariot drawn by two bulls. Both subjects are surrounded by mythological figures. They are engraved also in Lacroix, Arts of the middle ages, as an illustration of book-binding: and in the second volume of the Monumens antiques inédits, by Millin.

There is a diptych of perhaps the fifth century in the treasury of the cathedral of Monza; one leaf representing Calliope sounding the lyre, and the other some unknown philosopher. Mr. Oldfield, in his excellent catalogue with very valuable notes of the Arundel series of fictile ivories, supposes the muse to be some Roman lady in an ideal character. He objects to Gori’s suggestion that the other leaf represents a poet, taking the characteristics to be those certainly of a philosopher. Another is in the public library at Paris, the two leaves having six muses, each of them accompanied by an author. These last have been guessed at by M. de Witte, who places the diptych in the fourth century. Neither M. Pulszky nor professor Westwood is inclined to agree with these guesses, except that one may perhaps be Euripides grouped with Melpomene. The workmanship is rude and the figures carved in high relief. Again, another diptych at Vienna in the cabinet of antiquities, is attributed to the time of Justinian. One leaf has a figure representing Rome; the other, Constantinople.

The above are all named in the essay attached to the catalogue of the Fejérváry collection by M. Pulszky; and professor Westwood very rightly adds to them one leaf of a diptych in the possession of count Auguste de Bastard, the diptych of St. Gall, the mythological figure of Penthea [Pg 34] in the museum of the hôtel Cluny, a perfect diptych in the cathedral of Novara, and another in the basilica of San Gaudenzio at the same place.

There is no example among all these which surpasses in beauty of execution or in the interest of the subject, two ivory tablets which were formerly the doors of a reliquary in the convent of Moutier in France, in the diocese of Troyes. When M. Pulszky wrote his essay both tablets were supposed to be lost; they had been described and engraved in the Thesaurus of Gori, from whose prints alone they were known. Happily both since have been recovered. The left tablet, discovered a few years ago at the bottom of a well, is in the hôtel Cluny, much injured, and the other is in the collection of the South Kensington museum. The South Kensington leaf is probably the most beautiful antique ivory in the world. (See etching.) Each leaf represents a Bacchante; on both they are standing, and the Bacchante on the leaf in the English collection is accompanied by an attendant. Clothed from the shoulders to the feet in a long tunic, she stands near an oak-tree before an altar, on which a fire is lighted, and she is in the act of dropping a grain of incense from a small box held in her left hand. The whole figure is extremely graceful and dignified, the expression of the face earnest and devotional, and the form of the figure rightly expressed beneath the drapery; the hands and feet also well and carefully carved. On the corresponding leaf, preserved at Paris, the Bacchante has no attendant. Her drapery falls negligently suspended from her left shoulder, leaving the right arm and breast exposed. Professor Becker in his “Gallus,” describing the Lycoris of Virgil’s tenth eclogue, says: “Her light tunica, without sleeves, had become displaced by her movements and slidden down over her arm, disclosing something more than the dazzling shoulder.” He adds in a note that “the wide opening for the neck, and the broad holes for the arms, caused the tunica on every occasion of the person’s stooping to slip down over the arm. Artists appear to have been particularly fond of this drapery.” Such an arrangement, or rather disarrangement, of drapery would equally happen when the tunic was fastened over the shoulder by a small fibula, as it is represented upon the right arm of the young attendant in the South Kensington leaf. The Paris Bacchante stands before an altar on which a fire burns, and holds in each hand a torch with the flaming end downwards, as if to extinguish them. Her hair is gracefully bound with a riband decorated with ivy leaves, and falls down her back. A pine tree, stiff in design, stands close behind the altar; not to be compared with the oak-tree on the other leaf.

[Pg 35] This admirable diptych was, perhaps, a gift on the occasion of some marriage between members of the two patrician families whose names are on the labels: NICOMACHORVM. SYMMACHORVM; or it may possibly have formed the cover of the marriage contract itself, the tabulæ nuptiales of which Juvenal speaks; or perhaps it was a joint offering to the temple of Bacchus or Cybele. The last supposition would be confirmed if the omitted word was “religio,” as suggested by Passeri, who believes that the two families took the opportunity of recording upon this diptych, on some occasion of importance common to both of them, their determination to uphold the old heathen worship against the doctrines and influence of Christianity, at that time widely extending.

Before we pass to the large series of ivory carvings executed between the eighth or ninth and the fifteenth centuries, there is one very celebrated piece about which a few words may be said: a superb leaf of a diptych, preserved in the British museum. The other leaf is lost and has probably been destroyed; nor is there any record (it is believed) from whence that museum obtained the ivory. It has been in the collection for many years. [Pg 36]

The plaque itself is one of the largest known: more than sixteen inches in length by nearly six in width. The subject is an angel, standing on the highest of six steps under an arch supported on two Corinthian columns; he holds a globe with a cross above it in his right hand; in his left a long staff, to the top of which, as if half resting on it like a warrior on his lance, the hand is raised above his head. He is clothed in a tunic and an ample cloak or mantle falling round him and over the shoulders in graceful folds. His head is bound round with a fillet, and the feet have sandals. There is no antique ivory carving which surpasses this in grandeur of design, in power and force of expression, or in the excellence of its workmanship. Although some foreign writers are disposed to place the date of it so late as the time of Justinian, we shall be more correct in attributing it, with Mr. Oldfield, to the fifth or even to the end of the fourth century. Nor, looking at it, can we hesitate to claim for the earliest Christian art, after Christianity was recognised by Constantine, a place by the side of the best works of pagan times. If we select this, and the book-covers in the treasury of the cathedral at Milan, and the well-known book-cover in the public library at Paris, we shall find no western work in ivory to equal them in quality and beauty of workmanship from the fifth to the thirteenth century. [Pg 37]

We owe the preservation of many of these consular and mythological diptychs to the circumstance that when the practice of sending them as presents had (it may be) for some time been discontinued, another use was found by adapting them to Christian purposes. In some cases the subjects or titles of the diptychs were altered; as, for example, in one of the diptychs preserved at Monza. This was originally a consular diptych, of late work, coarse in style and manner of execution. The consul is represented on each wing, raising the mappa circensis in the usual way: on one, however, he is standing; on the other he is sitting upon a kind of throne. On one leaf the top of the consul’s head has been shaved, to show the clerical tonsure; and in the blank space of two small panels, immediately beneath the arch under which he stands, the title S[an]C[tu]S GREGoR[ius] is cut in high relief. On the other leaf above the sitting consul, on the corresponding panels, DAVID REX is inscribed in similar letters. Both the wings are engraved by Gori. It must not be omitted that some late writers have argued that this diptych is not a palimpsest; that it is merely an imitation of the preceding consular diptychs, and not earlier than the seventh or eighth century. But the whole character is unlike mere imitation; and the shaving of the head, the alteration of the ornamented top of the sceptre or staff, and the cutting of the inscription on the tablets, might without difficulty have been made for the required and more modern purpose.

It is easy to understand how later possessors of consular diptychs were induced to make presents of them to their bishops and churches; and in some instances, probably, in the sixth century, those originally sent to high ecclesiastical persons were at once transferred to pious uses. Instead of containing the lists of the consuls, the diptychs then inclosed the names of martyrs, saints, or bishops who were to be commemorated in the public service of the Church. These lists were read at mass: of the saints at that part of the canon which is now known as the Communicantes; and of the dead at the Memento, after the consecration of the Eucharist. Frequent reference to the custom is to [Pg 38] be found in the old ritualists, and full information and a cloud of authorities on the subject in the learned work of Salig, on diptychs. The leaves of several such diptychs still exist, and sometimes with the names not written on wax, but carved or incised upon the ivory itself.

One very remarkable example is the diptych, now at Liverpool, of Flavius Clementinus, consul a.d. 513. Upon the back of each leaf a long Greek inscription has been incised, done, beyond doubt, in the first year of pope Hadrian, a.d. 772, when the diptych was given to some church for sacred use. The list of names inscribed, to be prayed for, includes that of the donor.

The two inscriptions are to be read across both divisions, and were engraved probably upon the ivory by some one not well skilled in the language. There are several faults, both in spelling and in the letters: for example, we have στομεν sΘεωτωκος; ελεωςd; and ι often instead of η.

The inscription is to this effect: “✠ Let us stand well. ✠ Let us stand with reverence. ✠Let us stand with fear. Let us attend upon the holy oblation, that in peace we may make the offering to God. The mercy, the peace, the sacrifice of praise, the love of God and of the Father and of our Saviour Jesus Christ be upon us, Amen. In the first year of Adrian, patriarch of the city. Remember, Lord, thy servant John, the least priest of the church of St. Agatha. Amen. ✠ Remember, Lord, thy servant Andrew Machera. Holy Mother of God; holy Agatha. ✠ Remember, Lord, thy servant and our pastor Adrian the patriarch. ✠ Remember, Lord, thy servant, the sinner, John the priest.”

Another example is the diptych of Anastasius, a.d. 517, of which one leaf, no. 368, is in the South Kensington collection. Upon this leaf the portion of a single word “GISI” is now alone to be deciphered; when Wiltheim saw it, more than a hundred years ago at Liege, he read “IGISI,” and supposed it to be part of the name of [Pg 39] Ebregisus, the twenty-fourth bishop of Tongres, in the seventh century. But upon the other leaf, which is now preserved at Berlin, Gori was able to make out a considerable portion. “Offerentes ... O ... eorum p. pi ... ecclesia catholica quam eis dominus adsignare dignetur ... facientes commemorationem beatissimorum apostolorum et martyrum omniumque sanctorum. Sanctæ Mariæ Virginis, Petri, Pauli, etc.” But he owns that some even of these words are conjectural.

The diptych of Justinianus, in the public library at Paris, is one more example of the same kind. Inside are written litanies of the ninth century, with the names of saints inserted who were particularly revered at Autun.

Another half of a consular diptych may be mentioned, a single leaf, in which instance the original carving has not only been removed but the ivory has been sawn into two pieces. As it happens, both fragments are in this country—one in the British museum, the other in the South Kensington collection, no. 266. The two together have still sufficient traces left to enable us to recognise the old design: a consul seated in the usual way, under a round arch. Below, there seem to have been the two boys or servants emptying their sacks of money and presents.

This mutilation occurred about the eighth or ninth century; and the other side of the leaf was then carved with subjects taken from the gospels. It was an unnecessary injury to destroy and plane away the first design. As the new purpose was probably to decorate the panels of some shrine or book-cover, the old carvings might have been concealed when the plaques were inlaid, in the same manner as the very curious pieces were treated, now at South Kensington, nos. 253, 254, and 257.

It would be a subject far too extensive to attempt to give a history of the use and purpose of diptychs in the public service of the Christian Church. Their origin is to be traced to the very earliest times; perhaps to the apostolic age. Mention is made of them in the liturgy of St. Mark. Gori (or his author) quotes also the ecclesiastical hierarchy [Pg 40] of Dionysius the Areopagite. This is certainly not the writing of the true Dionysius, the contemporary of St. Paul. Yet, putting the pseudo-Dionysius as late as the fifth century, his evidence is valuable, and he speaks of the use of diptychs as of things long known.

Numerous treaties and dissertations, even long books, have been written on the subject; and it would be idle work to repeat the names of the authors who are referred to, over and over again, by most writers on ivory carvings. In fact, the learning which some of these exhibit might much better have been shown if their subject had been the primitive history and practices of the Church. Except to state the mere fact of their use, the connection of ceremonial ecclesiastical diptychs with sculpture in ivory requires only a few remarks.

The common use of such diptychs is well and shortly summed up in a dissertation printed by Gori in his Thesaurus. The summary may be given in few words, and, moreover, the dissertation itself is written in explanation of the diptych of the consul Clementinus just mentioned, which we are now fortunate enough to possess in England, in the Mayer collection at Liverpool. Inside the leaves, as has been already observed, is an inscription in Greek of the eighth century, to be read during mass, desiring the people to be devout and reverent and to pray for the persons whose names were to be recited.

The Christian diptychs were intended for four purposes. First come those in which the names of all the baptised were entered, a kind of Fasti ecclesiæ, and answering to the registers kept now in every parish. Second, those in which were recorded the names of bishops and of all who had made offerings to the church or other benefactions. This list included the names of many persons still living. Third, those in which were recorded the names of saints and martyrs; and, naturally, in various places the names would be particularly of saints who in their lives had been connected with the locality. Such additions are of the utmost importance in tracing the history of ancient lists which have [Pg 41] come down to our own time. Diptychs of this class were read aloud at mass, as a sign of the communion between the Church triumphant and the Church militant on earth. Fourth, those in which were written the names of dead members of the particular church or district, who having died in the true faith and with the rites of the church were to be remembered at mass.

As regards the living, the continuance of their names in the diptychs was of the highest consequence; to be erased was equal to the denunciation of them as heretics and unworthy of communion.

In the diptychs also were probably sometimes added the names of people who were sick or in trouble.

But besides these four objects for which Christian diptychs were made, there was another which must certainly have caused the production of many large sculptured works in ivory from the seventh to the tenth century: namely, for the purpose of exciting devotion and as a means also of teaching the ignorant. Ivory tablets or diptychs of this description are ordered to be exposed to the people in the old Ambrosian rite for the church of Milan.