The mercenaries of the war lords had fought

their last paying fight. They—the war

lords—the civilization was bankrupt—

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction April 1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

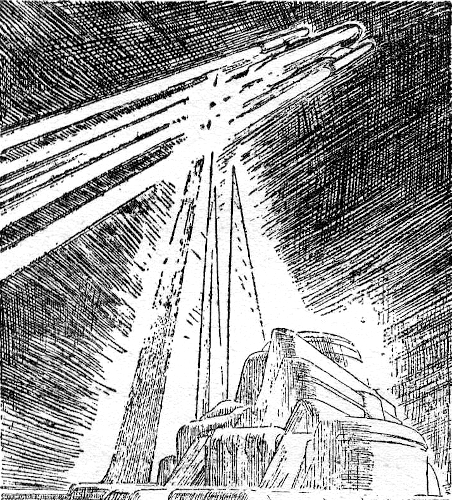

There were no stars. The ruined landing field was lit by dancing shadows from a huge bonfire. With forlorn, hollow eyes the broken towers looked down upon the field, the leaping flames, and the one battered space boat. Beyond the dancing fire the night waited threateningly.

In the shadow of one of the rickety towers a man huddled before a tiny flame and now and then turned his attention to a bubbling pot that hung from a forked stick above the coals. He was lean and broad-shouldered. The flickering coals occasionally lit up his thin face—the somber, gray eyes, the high cheekbones, the wide, sensitive mouth and the yellow curls that fell across a high forehead. The man seemed to be lost in thought, only turning his gaze away from the coals long enough to look up at the dark sky or to stir the pot of stew. When he moved to throw more wood upon the fire it was with the lithe grace of a cat, and even his tattered uniform took on a trim, military look from its wearer.

As the man stared into the fire he was listening to the sound of an approaching ship, half-heard, far above him in the dark sky. The noise of a descending ship increased, changed from a whine to a scream, and from a scream to a roar.

There was a roar and a gush of flame. A long, billowing jet of fire swept over the landing field like a scythe, and another space boat glided across the weed-strewn field. It stopped near the silent space craft. Both the boats were small, battered, patched and repatched—little one-man boats that had gone buzzing about space like wasps—as though the planets and the asteroids were golden fruit ripe for the taking.

The man before the fire made no movement other than to hitch his belt around so that a lean bronzed hand rested upon the worn butt of a pistol. He sat there looking into the fire, though he could hear the sound of feet stumbling through the underbrush. The night was chill, and with his free hand he pulled his patched leather jacket across his chest.

"Hello." The visitor stood before him smiling a cold smile—a little man with wide, drooping shoulders and eyes as blue as chilled steel.

The man before the fire grunted and motioned with his head for the newcomer to be seated.

"Smells good," said the visitor as he sat down and looked into the steaming pot. "That was white of you to build the fire. I'd never've landed without it. Not much power left, either." He sighed.

"That's O. K. I figured there would be more boats along. They're coming home now—those that have power enough in their engines to make the trip. My name's Duane, Jim Duane."

"They call me Captain," said the little man. "I've got other names, but mostly I answer to Captain. I'm a professional soldier." He added with a trace of a cold smile, "Like you."

"Yeah," Duane said wearily, "that's my work. Fightin' for the highest bidder. But when the war lords ran short of uranium they sent me home." He added with a malicious grin, "Like you."

"And damned lucky to get home. Plenty of boys marooned up there." Captain jerked his chin upward toward the dark, mist-swept sky. "But they'll find more uranium. They'll call us back. Twenty years of fightin' can't end this way. The war lords aren't satisfied. There'll be more power for those crates, and guys like us will be gentlemen again, drawin' monthly wages in four figures."

Duane shook his head. "It's gone. They've hunted everywhere. Oh, they found plenty—enough for centuries. But they burned it up in twenty years. They blasted the worlds apart. They fought like mad dogs. An' now it's gone. An' I'm damned glad."

Captain's eyes narrowed. "You don't talk like a fightin' man."

Duane's hand tightened upon his gun. "A man don't talk fight. Want to see how I fight?"

The little man shrugged his broad shoulders. "I only fight for money. Perhaps we'll fight for different war lords some day."

The scuffling of boots through the undergrowth eased the tension between the two. Two figures stumbled toward the fire. Two men in tattered leather coats and ragged pants and worn boots stopped as one, and stood there with downcast eyes as though awaiting an invitation.

"Space-nuts," said Captain none too softly.

One of the men looked up and patted a bulge in his coat. "I got a can of tomatoes." He smiled timidly. He was a thin little man with a sunken chest and a long pointed nose. His sunken eyes were black and dull.

Duane had seen hundreds like the two. There were men who cracked up out there in space, men who broke under the strain of the screaming, bellowing, fire-blasting wars.

"Throw the tomatoes in the pot," he said carelessly. "Sit down and warm. My name's Duane. This is Captain—that's his name, he's not my captain."

The man drew a can opener from his pocket and produced the tin of tomatoes. As he sawed at the lid he said listlessly, "I'm Ted Shafer. Used to have my own ship. But I lost it. 'Bout a year ago I was shippin' on a freighter an' they marooned me here. Said I was nuts. I'm not nuts. You can see that I ain't nuts. Well, I been livin' around here for about a year—livin' off what I could find. There's a ruined town over there. Then I run into this feller about a week ago. His name is ... say, what's your name? I keep forgettin'."

The fourth man, a squat, paunched fellow with a red nose and a thick unkempt beard, snorted. "The name's Belton. Bill Belton. You're gettin' crazier and crazier. I been around here for about six months. Only I wasn't marooned. I jumped ship. You guys got anything to drink?"

Captain swore. "Just a couple of bums. I oughta give 'em the toe of my boot—"

Duane's eyes narrowed. "It's my fire," he said softly.

"O. K., O. K. But they're full of lice, I bet—"

Shafer and Belton sat by the fire, their shoulders slumped forward.

Duane reached behind him into the shadows and brought out a roll of bedding. He produced four plates and four tin spoons and began to ladle out the mulligan. When he served, Shafer and Belton were profuse with their thanks. Captain was contemptuous.

"Mulligan," he swore. "Damn, I've sat at tables with war lords. Twenty courses on silver dishes and wine and liquor enough for all. And everybody dressed like hell."

Duane grinned. "Sorry I ain't a war lord. Maybe you'd like a punch in the nose."

Captain took the proffered plate sullenly. "I'm sorry. I keep forgettin'. Geez, I hope they dig up some more uranium soon. It's hard to take this when you've been used to a monthly salary that runs into four figures."

Duane looked up at the dark sky that was vacant save where a trailing mist tangled with the smoke from the fire.

"They won't find any more uranium. Not soon, anyway. I've thought a lot about it. We weren't ready to conquer space. We made a mess of it. Oh, we had the ships and the guns. Mechanically we were perfect. It was us who was wrong. We conquered space but we hadn't conquered ourselves. That will come some day."

"You sound like a parson," Captain jeered.

Little Shafer mouthed his food wolfishly, now and then drawing the back of his hand across his mouth and the tip of his long pointed nose. "What makes you think we won't find any more uranium?" he asked slyly.

Duane looked at him. The little man's fingers were trembling.

"Oh, we might find it," Duane said, "but there's no organization any more. It's been blown to hell. If we do find uranium, we'll lose it again. We're all washed up—for the time being, anyway. We'll have to dig in here on old Terra and start from scratch. Personally, I'm glad."

Captain snorted. "Nurts."

"There's uranium aplenty left," little Shafer said stubbornly.

Captain's eyes narrowed. "Know where it is, punk?"

Shafer avoided that steely glance. "Maybe I do and maybe I don't," he evaded.

Belton scraped the last bit of grease from his plate and belched contentedly. "I was rich once," he told the fire.

Captain sneered. "You ain't ever had the price of an extra drink in your pocket."

"I was rich once, just the same." Bill Belton looked from face to face pleadingly. A coal sputtered into the flame and lit the high color on his bulby nose and swollen cheeks. "I was rich once, richer than dirt."

"O. K.," Duane told him. "Maybe you were. Go ahead and tell your tale and get it off your mind. I'm not sleeping tonight, anyway."

"It'll be a rum-soaked, mangy lie that he dreamed up between panhandling and fightin' pink lizards." Captain yawned.

Belton looked hurt and lowered his eyes to the fire.

"I was rich once. I was runnin' a one-man mining boat out of Achilles. It wasn't much of a boat, but it was mine. An' all of a sudden I came across a freighter, a drifter. A meteor had torn about a fourth of her away, and she was driftin' and spinnin' alone out there in space with all the stars a-twinklin' down at her like diamonds sparklin' on black velvet.

"So I boarded her, and every bit of oxygen had been ripped from her, and there was all the poor boys there, dead and frozen in Old Father Time's icebox. Well, that ship was loaded with furs. She had been outward bound from Pallas, I reckon. An' those furs were all mine by rights of salvage. A king's ransom. I packed my boat with 'em until I hardly had room to move about it.

"An' then, just off Mars, a damned bunch of hellhounds boarded me and cleaned me out and set me adrift in one of those dinky little emergency boats. I've thought of it and thought of it. Those furs were mine. I was rich. They robbed me. But I got the name of that boat. I saw the name. Some day I'll catch some of those fellows. Or even one—"

While Belton was talking, little Shafer slowly slumped over the fire and held his hands over the coals. His fingers were shaking as though he had a chill. His dull, close-set eyes glanced this way and that furtively.

And two pairs of eyes were upon him, Captain's and Duane's. Captain reached into an inner pocket of his leather jacket and produced a flask. Slowly he uncorked it and held it toward the little man, then drew it back temptingly. Shafer's clutching, trembling fingers followed the flask.

"You seem like a good little guy," Captain said. "An' you look sick. Take it all. It's all I've got, but—" He shrugged his broad shoulders and smiled his cold smile.

Duane watched the little play before him. In his deep eyes was pity for this little derelict and contempt for the man who was leading him on.

"He thinks you know where some uranium is buried," he said mockingly. "He'll trade you a drink for a ton of uranium."

"Go to hell," Captain told him. And then to Shafer, "Go ahead. Drink her down. Don't mind this space lawyer."

The little man obliged. Belton watched, fascinated.

"Hell, don't I get a nip?" he objected.

"Not a drop," Captain's cold eyes were murderous. "Can't you see, this little fellow's a gentleman? I bet he's seen better days—"

"Haven't we all?" Duane interrupted.

"Leave the little guy alone." Captain thumped Shafer on the back lustily. The little man smiled timidly and tilted the flask again.

"Thanks." He drew the back of his hand across his mouth and held out the flask to Captain.

Captain waved it away airily.

"Nix, I can tell when a guy needs a drink better than I do. I bet you've seen better days. Bet you were richer than this mug who yaps about findin' a load of furs—like he was a damned scavenger."

Belton flushed. "Listen." One hand stole within his tattered jacket.

"Easy," Duane said, and patted the worn butt of his gun. Belton slumped back over the fire and began to mutter to himself.

Shafer had taken another pull at the flask. A feverish light was coming into his dull eyes.

"Furs," he snorted contemptuously. "Dirty, stinkin' furs! Who gives a damn about furs? Why, I got a corner on all the wealth in the world. The overlords will be beggin' after me some day. I'm richer than all the stars 'cause I got what everybody wants."

"I knew a guy who talked like that once," put in Duane softly. "He was singin' a tune just like that in a two-bit bar. But he didn't have money enough to pay for his last drink and they threw him out into the street."

"Shut up." Captain smiled, confident that Duane had played into his hand. "Never mind this cynic."

Shafer looked at Duane and tried to sneer. "Think I'm lyin', eh? Well, you'll see. I used to own my own boat, I did. An' I found a mine, a nice, floatin' mine. I didn't have to stake it, 'cause I'm the only one who knows where it is."

"Sure," said Captain.

"Tons and tons of uranium." Shafer turned the words over in his mouth as though they were bon-bons.

"Sure," said Captain softly. "Enough for all. We'll live like kings."

Shafer straightened and looked about him, frightened. His eyes dulled again. "You're trying to get me to talk. No, it's mine. All mine. I found it. Nobody else knows where it is."

Again Captain patted Shafer's thin shoulders. "We were just interested in your story, weren't we, men?"

Duane grunted his contempt.

Little Shafer took another pull at the flask. "Yes, sir," he said dreamily. "I was cruisin' out there in space, 'way off the space lanes, when I bumped into it. A little asteroid not over half a mile across. And solid uranium. I chartered it. I figgered out its orbit to an inch. I used to could do that. An' it's mine. Over an' over I keep repeatin' those figures to myself.

"I may forget other things but I won't forget that orbit. An' I'll write it down when someone puts the cold cash in my hand."

He was silent for a moment. Then he took another drink and began to talk to himself. "Yes, sir, I found an asteroid that's solid uranium. There I was, down on my luck, an' cruisin' around in my own ship, the Billikins—"

His thin hand went to his mouth as though to stop the words. His eyes were filled with fear. A scream slipped between his bony fingers.

Bill Belton was on his feet, a groping hand within his coat.

"You," he screamed. "Damn it, I'd know the name of that ship in hell. It was your ship. You took my furs."

The little man's trembling hands were thrust out in protest.

"No!" he screamed. "No, no, no!"

Slowly Belton's hand came from his coat. His stubby, grimy fist clutched a long knife. "It was you," he cried. He raised the knife in a shining arc.

Then little Shafer's fear changed to desperation. With a scream he jumped back and clawed at his coat. He was quick now. Fear had maddened him. A mean little pistol appeared in his hand. He fired point-blank at Belton's face.

Belton staggered and fell. His hands came up to a bleeding face that was a face no more. He screamed a wild, bubbly scream. Then he rolled into the fire, screamed again, struggled to his feet, and fell again—and lay still.

"You tricked me, damn you all." Shafer stood above the two seated men and brandished his gun. His eyes were burning now, little close-set pools of mad fire. His shaking hand steadied and lowered the gun toward Duane.

Duane's hand moved like a rattlesnake striking. Two stabs of flame lanced into the night. Shafer stumbled and fell.

Duane turned his attention to Captain. The little man was nursing a broken arm. A gun that had been levelled at Duane was slipping from deadened fingers.

"You fool," he cried. "You killed him. I believed that story. He knew where the uranium was."

Duane shrugged. "He was crazy. A killer. I know your kind, Captain. I knew what you were thinking when he hinted that he knew where a load of uranium was. You were figuring then that only you and Shafer would go away from this fire. You had your gun on me just then, ready to polish me off if Shafer missed."

"Damned blundering idiot," Captain swore. "Oh, I wish I had some of my men here."

"Leave your gun and get out," Duane told him.

"But it's dark. I can't go out there in the dark without a gun."

"Get out!" Duane's words were like icy barbs. "Mornin' will be here soon."

Captain struggled to his feet. He was sobbing with fear and rage and pain. Slowly he moved away from the fire.

"And remember what I said," Duane called after him. "Men will conquer the stars some day—after they have conquered themselves."

Captain's retreating figure faded into the night. The sound of his stumbling footsteps died away.

Duane sat there before the little fire, staring intently into the coals, oblivious of the two fallen figures that lay there in the shadows. At length he arose. In the east a bit of silver was appearing. As he watched, the silver grew brighter; and long spars of purple and rose stretched across the sky.

And as morning dawned the sweeping mists faded and disappeared. The sky was empty—but clear and shining with promise.