Their captors had a very curious system, a very

curious motivation. The captives were allowed

to—even encouraged to—build devices to bring

about their escape. Only at the last moment,

mysteriously, the captors always stopped them—

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction September 1943.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Dr. Little woke up abruptly, with a distinct sensation of having just stepped over a precipice. His eyes flew open and were greeted by the sight of a copper-colored metal ceiling a few feet above; it took him several seconds to realize that it was keeping its distance, and that he was not falling either toward or away from it. When he did, a grimace of disgust flickered across his face; he had lived and slept through enough days and nights in interstellar space to be accustomed to weightlessness. He had no business waking up like a cadet on his first flight, grasping for the nearest support—he had no business waking up at all, in these surroundings! He shook his head; his mind seemed to be working on slow time, and his pulse, as he suddenly realized as the pounding in his temples forced itself on his awareness, must be well over a hundred.

This was not his room. The metal of the walls was different, the light was different—an orange glow streaming from slender tubes running along the junction of wall and ceiling. He turned his head to take in the rest of the place, and an agonizing barrage of pins and needles shot the length of his body. An attempt to move his arms and legs met with the same result; but he managed to bend his neck enough to discover that he was enveloped to the shoulders in a sacklike affair bearing all the ear-marks of a regulation sleeping bag. The number stenciled on the canvas was not his own, however.

In a few minutes he found himself able to turn his head freely and proceeded to take advantage of the fact by examining his surroundings. He found himself in a small chamber, walled completely with the coppery alloy. It was six-sided, like the cells in a bee-hive; the only opening was a circular hatchway in what Little considered the ceiling—though, in a second-order flight, it might as well have been a floor or wall. There was no furniture of any description. The walls were smooth, lacking even the rings normally present to accommodate the anchoring snaps of a sleeping bag. There was light shining through the grille which covered the hatchway, but from where he was Little could make out no details through the bars.

He began to wriggle his toes and fingers, ignoring as best he could the resulting sensations; and in a few minutes he found himself able to move with little effort. He lay still a few minutes longer, and then unsnapped the top fasteners of the bag. The grille interested him, and he was becoming more and more puzzled as to his whereabouts. He had no recollection of any unusual events; he had been checking over the medical stores, he was sure, but he couldn't recall retiring to his room afterward. What had put him to sleep? And where had he awakened?

He grasped the top of the bag and peeled it off, being careful to keep hold of it. He started to roll it up and paused in astonishment. A cloud of dust, fine as smoke, was oozing from the fibers of the cloth with each motion, and hanging about the bag like an atmosphere. He sniffed at it cautiously and started coughing; the stuff was dry, and tickled his throat unpleasantly. There could be only one explanation; the bag had been drifting in open space for a length of time sufficient to evaporate every trace of moisture from its fibers. He unrolled it again and looked at the stenciled number—GOA-III-NA12-422. The first three groups confirmed his original belief that the bag had belonged to the Gomeisa; the last was a personal number indicating the identity of the former owner, but Little could not remember whose number it was. The fact that it had been exposed to the void was not reassuring.

Dismissing that phase of the problem for the moment, the doctor rolled the bag into a tight bundle. He was drifting weightless midway between ceiling and floor, almost in the center of the room; the hatchway was in one of the six corners of the ceiling. Little hurled the bundle in the opposite direction. It struck the far corner and rebounded without much energy; air friction brought it to a halt a few feet from the wall. The doctor drifted more slowly in the direction of the grating. His throw had been accurate enough to send him within reach of it; he caught hold of one of the bars and drew himself as close as possible.

Any lingering doubt that might have remained in his still befuddled brain as to whether or not he were still on board the Gomeisa was driven away as he caught his first glimpse through the grille. It opened—or would have opened had it been unlocked—onto a corridor which extended in two directions as far as the doctor's limited view could reach. The hallway was about thirty feet square, but there its orthodox characteristics terminated. It had been built with a sublime disregard for any possible preferred "up" or "down" direction. Hatches opened into all four sides; those opposite Little's station were circular, like his own, while those in the "side" walls were rectangular. From a point beside each opening, a solidly braced metal ladder extended to the center of the corridor, where it joined a heavy central pillar plentifully supplied with grips for climbing. Everything was made of the copperlike material, and the only light came from the orange-glow tubes set in the corners of the corridor.

Dr. Little maintained his position for several minutes, looking and listening; but no sound reached his ears, and he could perceive nothing through the gratings which covered the other hatchways. He also gave a few moments' attention to the lock on his own grating, which evidently was operated from either side; but it was designed to be opened by a complicated key, and the doctor had no instruments for examining its interior. With a sigh he hooked one arm about a bar of the grating and relaxed, trying to reason out the chain of events which had led up to these peculiar circumstances.

The Gomeisa had been a heavy cruiser, quite capable of putting up a stiff defense to any conceivable attack. Certainly no assault could have been so sudden and complete that the enemy would be in a position to use hand weapons on the crew before an alarm was raised—the idea was absurd; and fixed mount projectors of any type would have left more of a mark on the doctor than he could find at this moment. Furthermore, the ship had been, at the last time of which Little had clear recollection, crossing the relatively empty gulf between the Galaxy proper and the Greater Magellanic Cloud—a most unpropitious place for a surprise attack. The star density in that region is of the order of one per eight thousand cubic parsecs, leaving a practically clear field for detector operations. No, an attack did not seem possible; and yet Little had been deprived of consciousness without warning, had been removed from the Gomeisa in that state, and had awakened within a sleeping bag which showed too plainly the fact that part, at least, of the cruiser had been open to space for some time.

Was he in a base on some planet of one of those few stars of the "desert," or in some ship of unheard-of design? His weightlessness disposed of the first idea before it was formulated; and the doctor glanced at his belt. Through the glass window in its case, he could see the filament of his personal equalizer glowing faintly; he was in a ship, in second-order flight, and the little device had automatically taken on the task of balancing the drive forces which would, without it, act unequally on each element in his body. As a further check, he felt in his pocket and drew out two coins, one of copper and one of silver. He held them nearly together some distance from his body, released them carefully so as not to give them velocities of their own, and withdrew his hand. Deprived of the equalizer field, they began to drift slowly in a direction parallel to the corridor, the copper bit moving at a barely perceptible crawl, the silver rapidly gaining. The corridor, then, was parallel to the ship's line of flight; and the coins had fallen forward, since the silver was more susceptible to the driving field action.

Little pushed off from the ceiling and retrieved the coins, restoring them to his otherwise empty pocket. He had not been carrying instruments or weapons, and had no means of telling whether or not he had been searched while unconscious. Nothing was missing, but he had possessed nothing worth taking. The fact that he was locked in might be taken to indicate that he was a prisoner, and prisoners are customarily relieved of any possessions which prove helpful in an escape. Only beings who had had contact with humanity would logically be expected to identify which of the numerous gadgets carried by the average man are weapons; but the design of this craft bore no resemblance to that of any race with which Little was acquainted. He still possessed his wrist watch and mechanical pencil, so the doctor found himself unable to decide even the nature of his captors, far less their intentions.

Possibly he would find out something when—and if—he was fed. He realized suddenly that he was both hungry and thirsty. He had been unconscious long enough for his watch to run down.

Little's pulse had dropped to somewhere near normal, he noticed, as he drifted beside the hatch. He wondered again what had knocked him out without leaving any mark or causing some sensation; then gave up this line of speculation in favor of the more immediate one advocated by his empty stomach. He fell asleep again before he reached any solution. He dreamed that someone had moved Rigel to the other side of the Galaxy, and the navigator couldn't find his way home. Very silly, he thought, and went on dreaming it.

A gonglike note, as penetrating as though his own skull had been used as the bell, woke him the second time. He was alert at once, and instantly perceived the green, translucent sphere suspended a few feet away. For a moment he thought it might be one of his captors; then his nose told him differently. It was ordinary lime juice, as carried by practically every Earth cruiser. A moment's search served to locate, beside the hatchway, the fine nozzle through which the liquid had been impelled. The doctor had no drinking tube, but he had long since mastered the trick of using his tongue in such circumstances without allowing any other part of his face to touch the liquid. It was a standard joke to confront recruits, on their first free flight, with the same problem. If nose or cheek touched the sphere, surface tension did the rest.

Little returned to the door and took up what he intended to be a permanent station there. He was waiting partly for some sign of human beings, partly for evidence of his captors, and, more and more as time wore on, for some trace of solid food. He waited in vain for all three. At intervals, a pint or so of lime juice came through the jet and formed a globe in the air beside it; nothing else. Little had always liked the stuff, but his opinion was slowly changing as more and more of it was forced on him. It was all there was to drink, and the air seemed to be rather dry; at any rate, he got frightfully thirsty at what seemed unusually short intervals.

He wound his watch and discovered that the "feedings" came at intervals of a little over four hours. He had plenty of chance to make observations, and nothing else to observe; it was not long before he was able to predict within a few seconds the arrival of another drink. Later, he wished he hadn't figured it out; the last five or ten minutes of each wait were characterized by an almost agonizing thirst, none the less painful for being purely mental. Sometimes he slept, but he was always awake at the zero minute.

With nothing to occupy his mind but fruitless speculation, it is not surprising that he lost all track of the number of feedings. He knew only that he had slept a large number of times, had become deathly sick of lime juice, and was beginning to suffer severely from the lack of other food, when a faint suggestion of weight manifested itself. He looked at his equalizer the instant he noticed the situation and found it dark. The ship had cut its second-order converters, and was applying a very slight first-order acceleration in its original line of flight—the barely perceptible weight was directed toward what Little had found to be the stern. Its direction changed by a few degrees on several occasions, but was restored each time in a few seconds. The intensity remained constant, as nearly as Little could tell, for several hours.

Then it increased, smoothly but swiftly, to a value only slightly below that of Earthly gravity. The alterations in direction became more frequent, but never sudden or violent enough to throw Little off his feet—he was now standing on the rear wall, which had become the floor. Evidently the ship's pilot, organic or mechanical, well deserved the name. For nearly half an hour by the watch, conditions remained thus; then the drive was eased through an arc of ninety degrees, the wall containing the hatchway once more became the ceiling, and within a few minutes the faintest of tremors was perceptible through the immense hull and the direction of gravity became constant. If this indicated a landing, Little mentally took off his hat to the entity at the controls.

The doctor found himself badly placed for observation. The hatch was about four feet above the highest point he could reach, and even jumping was not quite sufficient to give him a hold on the bars. He estimated that he had nearly all of his normal hundred and ninety pounds Earth weight, and lack of proper food for the last several days had markedly impaired his physical powers. It was worse than tantalizing; for suddenly, for the first time since he had regained consciousness in this strange spot, he heard sounds from outside. They were distorted by echoes, sounding and reverberating along the corridor outside, and evidently originated at a considerable distance, but they were definitely and unmistakably the voices of human beings.

For minutes the doctor waited. The voices came no nearer, but on the other hand they did not go any farther away. He called out, but apparently the group was too large and making too much noise of its own to hear him. The chatter went on. No words were distinguishable, but there was a prevailing overtone of excitement that not even the metallic echoes of the great hull could cover. Little listened, and kept his eyes fixed on the hatchway.

He heard nothing approach, but suddenly there was a faint click as the lock opened. The grille swung sharply inward until it was perpendicular to the wall in which it was set; then the side bars of its frame telescoped outward until they clicked against the floor. The crossbars separated simultaneously, still maintaining equal distances from each other, and a moment after the hatch had opened a metal ladder extended from it to the floor of the room. It took close examination to see the telescopic joints just below each rung. The metal tubing must be paper-thin, Little thought, to permit such construction.

The doctor set foot on the ladder without hesitation. Presumably, his captors were above, and wanted him to leave the room in which he was imprisoned. In this wish he concurred heartily; he was too hungry to object affectively, anyway. He made his way up the ladder to the corridor, forcing his shoulders through the narrow opening. The human voices were still audible, but they faded into the background of his attention as he examined the beings grouped around the hatch.

There were five of them. They bore some resemblance to the nonhumans of Tau Ceti's first planet, having evidently evolved from a radially symmetric, star-fishlike form to a somewhat more specialized type with differentiated locomotive and prehensile appendages. They were five-limbed and headless, with a spread of about eight feet. The bodies were nearly spherical; and if the arms had been only a little thicker at the base it would have been impossible to tell where body left off and arm began. The tube feet of the Terrestrial starfish were represented by a cluster of pencil-thick tendrils near the tip of each arm and leg—the distinction between these evidently lying in the fact that three of the appendages were slightly thicker and much blunter at the tips than the two which served as arms. The tendrils on the "legs" were shorter and stubbier, as well. The bodies, and the appendages nearly to their tips, were covered with a mat of spines, each several inches in length, lying for the most part nearly flat against the skin. These either grew naturally, or had been combed away from the central mouth and the five double-pupiled eyes situated between the limb junctions.

The beings wore metal mesh belts twined into the spines on their legs, and these supported cases for what were probably tools and weapons. Their "hands" were empty; evidently they did not fear an attempted escape or attack on the doctor's part. They made no sound except for the dry rustle of their spiny armor as they moved. In silence they closed in around Little, while one waved his flexible arms toward one end of the passageway. A gentle shove from behind, as the doctor faced in the indicated direction, transmitted the necessary command, and the group marched toward the bow. Two of the silent things stalked in front, two brought up the rear; and at the first opportunity, the other swarmed up one of the radial ladders and continued his journey directly over Little's head, swinging along by the handholds on the central beam.

As they advanced, the voices from ahead grew slowly louder. Occasional words were now distinguishable. The speakers, however, were much farther away than the sound of their voices suggested, since the metal-walled corridor carried the sounds well if not faithfully. Nearly three hundred yards from Little's cell, a vertical shaft of the same dimensions as the corridor interrupted the latter. The voices were coming from below. Without hesitation, the escort swung over the lip of the shaft and started down the ladder which took up is full width; Little followed. On the way, he got some idea of the size of the ship he was in. Looking up, he saw the mouths of two other corridors entering the shaft above the one he had traversed; at the level of the second, another hallway joined it from the side. Evidently he was not near the center line of the craft; there were at least two, and possibly three, tiers of longitudinal corridors. He had already seen along one of those corridors; the ship must be over fifteen hundred feet in length. Four vessels the size of the Gomeisa could have used the immense hull for a hangar, and left plenty of elbow room for the servicing crews.

Below him, the shaft debouched into a chamber whose walls were not visible from Little's position. His eyes, however, which had become exceedingly tired of the endless orange radiance which formed the ship's only illumination, were gladdened at the sight of what was unquestionably daylight leaking up from the room. As he descended, two of the walls became visible—the shaft opened near one corner—and in one of them he finally saw an air lock, with both valves open. He went hastily down the remaining few feet and stopped as he touched the floor. His gaze took in on the instant the twenty-yard square chamber, which seemed to occupy a slight outcrop of the hull, and stopped at the corner farthest from the air lock. Penned in that corner by a line of the starfish were thirty-eight beings; and Little needed no second glance to identify the crew of the Gomeisa. They recognized him simultaneously; the chatter stopped, to be replaced by a moment's silence and then a shout of "Doc!" from nearly two score throats. Little stared, then strode forward and through the line of guards, which opened for him. A moment later he was undergoing a process of handshaking and back-slapping that made him wonder. He didn't think he had been that popular.

Young Captain Albee was the first to speak coherently.

"It's good to see you again, sir. Everyone but you was accounted for, and we'd begun to think they must have filed you away in formaldehyde for future reference. Where were you?"

"You mean I was the only one favored with solitary confinement?" asked Little. "I woke up in a cell upstairs, about two thirds of the way back, with less company than Jonah. I could see several other sets of bars from my stateroom door, but there was nothing behind any of them. I haven't seen or heard any living creature but myself since then. I can't even remember leaving, or being removed from the Gomeisa. Does anyone know what happened?"

"How is it that you don't?" asked Albee. "We were attacked; we had a fight, of a sort. Did you sleep through it? That doesn't seem possible."

"I did, apparently. Give me the story."

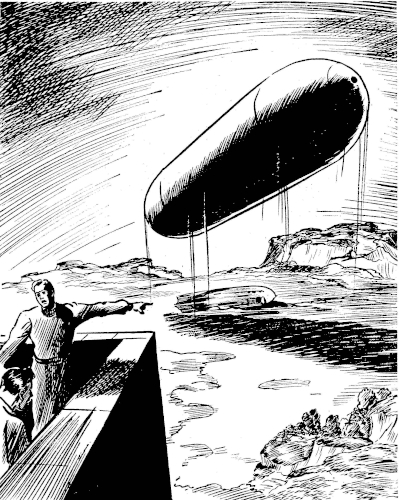

"There's not much to give. I was about to go off watch when the detectors picked up a lump that seemed highly magnetic, and something over eighty million tons mass. We hove to, and came alongside it while Tine look a couple of pictures of the Galaxy and the Cloud so that we could find it again. I sent out four men to take samples, and the instant the outer door was opened these things"—he jerked his head toward the silent guards—"froze it that way with a jet of water on the hinge and jamb. They were too close to use the heavy projectors, and we still had no idea there was a ship inside the meteoric stuff. They were in spacesuits, and got into the lock before we could do anything. By the time we had our armor on they had burned down the inner lock door and were all through the ship. The hand-to-hand fighting was shameful; I thought I knew all the football tricks going, and I'd taught most of them to the boys, but they had every last one of us pinned down before things could get under way. I never saw anything like it.

"I still can't understand what knocked you out. They used no weapons—that annoyed me—and if you didn't put a suit on yourself I don't see how you lived when they opened up your room. The air was gone before they started going over the ship."

"I think I get it," said Little slowly. "Geletane. Four cylinders of it. Did you broadcast a general landing warning when you cut the second-order to examine that phony Bonanza? You didn't, of course, since we weren't in a gravity field of any strength. And the 'meteor' was magnetic, which made no difference to our berylium hull, but made plenty to the steel geletane cylinders, one of which I had unclamped for a pressure test and had left in the tester. I went on about my business, and the field yanked the cylinder out of the tester and against the wall. It didn't make enough noise to attract my attention, because I was in the next room. With the door open. And the valve cracked just a trifle—just enough. I didn't need a suit when these starfish opened my room; I must have been as stiff as a frame member. I had all the symptoms of recovery from suspended animation when I woke up, too, but I never thought of interpreting them that way. The next ship I'm in, see if I don't get them to rig up an automatic alarm to tell what the second-order fields are doing—"

"You might also put your geletane cylinders back in the clamps when, and if, this happy state of affairs eventuates," remarked Goldthwaite, the gloomy technical sergeant. "May I ask what happens now, captain?"

"I'm afraid it isn't up to me, Goldy," returned Albee. "But I don't suppose they plan to keep us in this corner indefinitely."

Probably they didn't, but Albee was beginning to doubt his own statement before anything else happened. The sun had risen so that it was no longer shining directly into the port, and the great chamber had grown darker as the shadow of the vast interstellar flier crept down and away from its outer wall, when a new party came through the air lock from outside. Two of the pentapods came first, and came to a halt on either side of the inner door; after them crept painfully the long, many-legged, gorgeously furred body of a Vegan. Its antennae were laid along its back, blending with the black and yellow stripes: the tiny, heavily lidded eyes opened wide in the effort to see in what, to the native of the blue star, was nearly total darkness. The line of guards penning in the Earthmen opened and formed a double-walled lane between humans and Vegan.

Albee stepped forward, and at the same moment the interior lights of the chamber flashed on. The Vegan relaxed for a moment as its eyes readjusted themselves; then its antennae snapped erect and began to sway slowly in the simple patterns of the sign language of its race.

"I assume that some of you, at least, understand me," it said. "Our captors, having learned a little of my language in the months I have spent here, hope to save themselves trouble by using me as an interpreter. Do you wish to acknowledge acquaintance with my speech, or do you think it better to act as though our races had never encountered each other? I was not captured near my home planet, so you might get away with such an act."

Most of the Earthmen had some knowledge of Vegan speech—the two systems are near neighbors, and enjoy lively commercial relations—and all looked to Albee for a decision. He wasted little time in thought; it was evident that they would be better off in communication with their captors than otherwise.

"We might as well talk," he answered, forming the signs as well as he could with his arms. "We should like to find out all you can tell us about these creatures, and it is unlikely that we would be given the chance to communicate secretly with you. Do you know where we are, and can you tell us anything about this planet and its people?"

"I know very little," was the answer. "I believe this world is somewhere in the Cloud, because the only time one of us was ever outside the fort at night he could see the Galaxy. Neither I nor my companions can tell you anything about the planet's own characteristics, for we have been kept inside the base which these creatures have established here ever since our capture. We move too slowly in this gravity to escape from them, and, anyway, the sun has not sufficient ultraviolet light to keep us alive. Our captors, we are sure, are not natives of the planet; they seldom venture outside the walls themselves, and always return before nightfall. Furthermore, they live on provisions brought by their interstellar ships, rather than native food.

"They have not told us the reason for our capture. They allow us to prepare everything we need for existence and comfort, but every time we try to divert supplies to the production of weapons, they seem to know it. They let us nearly finish, and then take it away from us. They never get angry at our attempts, either. We don't understand them."

"If they are so careful of your well being, why do they try to drive us crazy on a steady diet of lime juice?" interrupted Little.

"I could not say; but I will ask, if you wish," returned the Vegan. He swung his fusiform body laboriously around until he was facing one of the creatures who had accompanied him to the ship, and began semaphoring the question. The men watched silently; those who had not understood the preceding conversation were given the gist of it in brief whispers by their fellows. Little had not had a chance to ask if the others had been fed as he had been; their silent but intense interest in the answer to his question indicated that they had. The chronic slowness of Vegan communication rendered them all the more impatient to know the reason, as the black and yellow creature solemnly waved at the motionless pentapod.

There was a brief pause before the latter began to answer. When it did, the Earthman understood why an interpreter was necessary, even though both sides knew the same language. The arms of the creature were flexible enough in front-to-rear motion, as are human fingers; but their relatively great width hampered them in side-to-side waves, and put them at a severe disadvantage in using the Vegan language. The Vegan himself must have had difficulty in comprehending; the Earthman could not make out a single gesture.

Finally the interpreter turned back to the human listeners and reported the result of his questioning:

"The green liquid is all that our captors found in the canteens of your space armor. Since there was a large supply of it on your ship, they assumed it was the principal constituent of your diet. They have, however, salvaged practically all of the contents of your vessel, and you will be allowed shortly to obtain your foodstuffs, cooking equipment, and personal belongings, with the natural exception of weapons. I might add, from my own experience, that their unfamiliarity with your weapons will not help you much if you attempt to smuggle any from the stores. We never could get away with it."

"What surprises me," remarked Albee in English, "is that we are allowed at the supplies at all. These creatures must be extremely confident in their own abilities to take a chance."

"From what you told me of the hand-to-hand fighting, such confidence may be justified," remarked Little with a grin. "Didn't you say that they more or less wiped up the floor with the boys?"

"True," admitted the captain, "but there's no need to rub it in. Why are they so stuck up about it?"

"Stuck up? I was getting a strong impression that, as a race, they must be unusually modest." Albee stared at the doctor, but could not get him to amplify the remark. The Vegan interrupted further conversation, attracting their attention with a flourish of its long antennae.

"I am told that your supplies have been unloaded through another port, and are lying on the ground outside the fort. You are to accompany me and the guards to the pile, and take all the food you wish—you may make several trips, if necessary, to get it all to your quarters in the fort."

"Where is this fort, in relation to the ship?" asked Albee. "What sort of land is around it?"

"The ship is lying parallel to the near wall of the fort, about two hundred yards from it. This air lock is near the nose of the ship, and almost opposite the main valves of the fort. In front of the ship the ground is level for about a quarter of a mile, then dips down into what seems to be a heavily forested river valley. I don't know what lies beyond, in that direction; this sunlight is too dim for me to make out the details of objects more than a mile or two distant. I do get the impression of hills or mountains—you will be able to see for yourselves, outside. Your eyes are adapted to this light.

"In the other direction, toward the stern, the level plain extends as far as I can see, without any cover. Anyway, you'd be between the ship and the fort for the first five hundred yards, if you went that way, and could easily be cornered. I warn you again that these creatures will outguess you, but—good luck. I've told you all I know."

"I guess we might as well go along and get our stuff, then," remarked Albee to his crew. "Don't do anything rash without orders. We'll wait until we see how the supplies are arranged. Maybe we'll have to move some apparatus to get at the food."

The black bodies of the guards had ringed them, almost statuesque in their motionlessness, during the conversation. As the Vegan concluded his speech, he had turned toward the lock; Albee had spoken as the men began to follow. The air of the planet was evidently similar to that of Earth, Vega Five, and the home planet of the pentapods, since both valves of the air lock were open. It had the fresh-air smell which the filtered atmosphere of a spaceship always seems to lack, and the men almost unconsciously squared their shoulders and expanded their chests as they passed down the ramp in the wake of the heavily moving Vegan. The scene before them caught all eyes; the interpreter's description had been correct, but inadequate.

The hull of the interstellar cruiser curved high above their heads. The lock chamber occupied a relatively tiny gondola that projected far enough, from its location well to one side of the keel, to touch the ground. The outside of the vessel gleamed with a brilliant silvery luster, in contrast to the coppery glow of the interior. The fort, directly in front of them, was an imposing structure of stone composition half a mile in length and two hundred feet high on the side facing them. The walls were smoothly polished, and completely lacking in windows.

To the left, beyond the nose of the craft, the level meadow continued for several hundred yards, and then dipped abruptly downward. As the Vegan had intimated, the background was filled by a range of rugged-looking mountains, the nearest several miles away. The sun was now nearly overhead, thereby robbing the landscape of the shadows that would have given the Earthman a better idea of its relief. Albee wasted little time looking for what he wouldn't be able to see; he strode on toward the great gate of the fort. In front of the portals were several large heaps of articles, and even at this distance some of them could be recognized as pieces of equipment from the unfortunate Gomeisa. The guards closed around the group of human beings and proceeded at the pace set by the captain, leaving the Vegan prisoner to follow at his own speed.

It was evident that a thorough job of looting had been done on the Terrestrial warship. Food and medical supplies, bunks, kitchen equipment, blankets and miscellaneous items of field apparatus were included in the half dozen heaps laid out beneath the glistening black walls. Mixed in with the rest were hand tools and weapons, and Albee, in spite of the Vegan's warning, began promptly to make plans. At his orders, each of the men dragged a shoulder pack out of one of the piles and began filling it with containers of food and drink. The pile of lime-juice bottles was pointedly ignored until Albee, glancing at it, noticed that one case of bottles was not green in color. He went over for a closer look, then extracted one of the plastic containers, opened it and sniffed. His voice, as he turned to the watching men, was just a little louder than usual:

"Would anyone know where they found this stuff?" His eyes wandered over the faces of the crew. It was Sergeant Goldthwaite who finally answered, hesitantly.

"They might have looked between the bulkheads at the cap end of the storage room, cap'n. It was pretty cool there, and seemed like a good place—"

"Not too easy to visit often, in flight," remarked the captain quizzically.

"I never visited it, sir—you can see it hasn't been touched. But you said we would probably touch at Ardome, and I was thinking it might be possible to get rid of it there."

"It probably would. But they have good customs inspectors, and war vessels aren't immune to search. I shudder to think of what would have happened to our reputation if we had made Ardome. Consider yourself responsible for this stuff."

The sergeant gulped. The case of liquor weighed eighty pounds, and could not possibly be crammed into a shoulder pack. He realized gloomily that the captain had inflicted about the only possible punishment, under the circumstances. He put five of the bottles into his pack and began a series of experiments to find out which way his arms went most easily around the case. A small group of pentapods regarded the struggle with interest, their spines waving slowly like a field of wheat in a breeze.

Albee watched, too, for a moment; then he went on, without altering the tone of his words:

"Most of you should have a decent supply of food by now. This planet probably has good water, since the vegetation and clouds appear normal. We should be able to live here without the aid of our generous captors, but we may have some difficulty in avoiding their well-meant ministrations. The Vegan said his people had never been able to fool these pincushions into letting them make or steal a weapon. Remembering that, use every caution in carrying out the orders I am about to give.

"When I have stopped talking, each of you count thirty, slowly, meanwhile working your way toward the handiest tool or weapon in the neighborhood. When you reach thirty, dive for the object of your choice and do your best to get to that forest. You have all, except the doctor, had some experience of the rough-and-tumble tactics of these creatures; the problem, I should say, is to get past them without a fight and into the open. I think we can outrun, on the level, any invertebrate alive. If someone is caught, don't stay to help him; right now, I want to get at least a small crew away from here, where we can work out at our leisure rescue plans for the unlucky ones. Don't all try to get guns; we'll find cutting tools just as useful in the woods. You may start counting."

Without haste, Albee counted over the contents of his pack, swung it to his shoulders. The guards, spines twitching slowly, watched. Reiser, the senior navigator, was helping one of Goldthwaite's engineers drag the ship's electric stove from a pile which chanced also to contain several ion pistols. Little picked up and tested briefly a hand flash, conscious of the fact that guards were watching him closely. The action had some purpose; the flash was almost exactly similar to the pistols. He tightened the straps of his own pack—and someone reached the count of thirty. Albee had chosen that number to give the men time enough to prepare, but not enough to get very far out of pace in the counting.

Almost as one, the human beings turned and sprinted for the bow of the warship. Almost simultaneously, the guards went into action, each singling out a man and going to work. Little, who had not experienced the tactics of the creatures, managed to avoid them for perhaps five yards; then one of them twined its tendrils about his wrist and literally climbed up onto his back. A moment later, the doctor was face down on the grass, arms and legs held motionless in the grip of the clumsy-looking, stubby limbs. The spines of his captor were not stiff enough to penetrate clothing or skin, but their pressure on the back of his neck was unpleasant. He managed to turn his head sufficiently to see what was going on.

Four men, who had been at the pile nearest the forest, had moved fast enough to avoid contact with their guards. They were now running rapidly toward the declivity; none of the creatures was in pursuit. Albee and a dozen others were practically clear, but one of these was pulled down as Little watched. One man found himself in a relatively clear space and made a dash. Guards closed in from either side, but realized apparently that they were not fast enough to corner the fellow. They turned back to other prey, and the runner was allowed to escape.

Goldthwaite had been in a bad position, with almost the whole group to fight through on his way to the woods. Apparently he never thought of disobeying orders, and going the other way. He dropped the case he had been trying to lift, seized a bottle from it with each hand and headed into the mêlée. Curiously enough, he was the only one using weapons; the guards, festooned with implements snapped to their leg belts, fought with their bare "hands," and the men all ignored their guns and knives in the effort to run. Most of the pentapods at the sergeant's end of the group were engaged, and he got nearly halfway through the group before he was forced to use his clubs.

Then a guard saw him and closed in. Goldthwaite was handicapped by the creature's lack of a head, but he swung anyway. The blow landed between the two upper limbs, just above one eye. It didn't seem to bother the pentapod, whose flexible legs absorbed most of the shock, and the tough plastic of the bottle remained unbroken; but the stopper, urged by interior pressure and probably not closed tightly enough—it may have been the bottle investigated by the captain—blew out, soaking the sergeant's sleeve and jacket with liquor. This particular fluid had some of the characteristics of Earthly champagne, and had been considerably shaken up.

Another of its qualities was odor. This, like the taste of Roquefort, required a period of conditioning before one could become fond of it; and this may have been the reason that the guard fell back for a moment as the liquid foamed out. It is more likely, however, that he was merely startled to find an object his people had decided was harmless suddenly exhibit the characteristics of a projectile weapon. Whatever the reason, he hesitated a split second before pressing the attack; and in that moment the sergeant was past.

Ahead of him, three or four more guards—all who remained unoccupied—converged to meet him. Without waiting for them to charge, Goldthwaite swung the other bottle a few times and hurled it into their midst. He was a man quick to profit by experience. Unfortunately, so were the guards. They saw the liquid which had soaked into the sergeant's clothes, and needed no further assurance that it was harmless. They paid no attention to the flying bottle until it landed.

This flask was stoppered more tightly and did not blow out. The pentapods, who had either seen the behavior of the first bottle or had been told of it, decided that the latest arrival was a different sort of weapon and prudently changed course, avoiding the spot where it lay, and the sergeant, with no such scruples, passed over it like a racehorse. It was several seconds before the guards overcame their nervousness over this new form of delayed-action bomb, and before they could circle around it, Goldthwaite was well out of reach across the plateau. By that time the action was over.

Albee had gotten away with about a dozen men. One of these had escaped through the co-operation of the Vegan, who, unable to run himself, had tripped up with an antenna the only guard in position to catch the man. Some twenty-five human beings lay about on the field, each held down by a single pentapod. Two swarms of the creatures were coming rapidly toward them, one from the ship and one from the fort. These formed a ring about the area, and Little found himself once more free to get to his feet. He did so, the others gathering round him.

All guns had disappeared, it seemed. One of the men had tried to use his when he had been intercepted, but his opponent had relieved him of the weapon before any damage had been done. Evidently the information had been broadcast, for all the other ion pistols had been confiscated, though the very similar flash tubes had not been touched. Injuries were confined to bruises.

Little was beginning to get ideas about his captors—he had, indeed, begun to get them some time since, as his cryptic remark to Albee had indicated. Every action they performed gave evidence of most peculiar motivation and thought processes, evidence which was slowly sifting its way through Little's mind. He continued to let it sift as the men, still ringed by pentapods, began to march toward the fort.

The great outer gate opened into a chamber large enough to hold the entire group with room to spare. It was about fifteen feet high, metal walled, and possessed but two doors—the outer valve and another, smaller, in the opposite wall, giving access to the interior of the structure. As though the room were an air lock, the inner portal was not opened until the outer had shut. Then the group passed into a brilliantly lit corridor, stretching on ahead of them far into the bowels of the fort. Hallways branched from this at intervals of a few yards, some brightly lighted like the main passage, others in nearly total darkness. They had gone only a short distance when the men were stopped by their escort in front of a small doorway in the left-hand wall.

One of the guards activated a small control in the wall beside the door, causing the latter to slide open. The small chamber disclosed was evidently an elevator car into which five of the pentapods beckoned an equal number of the men. The door slid to behind them, and several minutes of uneasy silence ensued. Little asked the Vegan if it knew where they were being taken.

"Our quarters are in a superstructure on the roof," gestured the creature. "They may put you there, or on the roof itself. You can live in the open under this sunlight; we need supplementary lighting, both visual and ultraviolet. They have told me nothing. I do not even know whether we will be allowed to communicate any further—though I hope so. My companions and I have long wanted to have someone besides ourselves to talk to."

"I suspect we shall be allowed as much contact as we wish—they may even quarter us in adjoining rooms," remarked Little hesitantly. The Vegan eyed him closely for a moment.

"Ah, you have found a way into their minds, Earthman?" it asked. "I congratulate you. We have never been able to understand their motivation or actions in the slightest degree. It may, of course, be that they think more after your fashion than ours—but that seems unlikely, when your minds and ours are sufficiently alike to agree even on matters of philosophy."

"I am not at all sure I have penetrated their minds," answered Little. "I am still observing, but what I see has so far strengthened the impression I obtained almost at the first. If anything constructive results from my ideas, I will tell, but otherwise I should prefer to wait until I am much more certain of my conclusions."

The return of the elevator interrupted the laborious exchange of ideas. It had been gone many minutes, but the Vegan sign language is much slower than verbal speech, and the two allies had had time for only a few sentences. They watched silently as five more men and their guards entered the car and disappeared. There was little talk in the ensuing wait; most of the beings present were too fully occupied in thinking. One or two of the men exchanged low-voiced comments, but the majority kept their ideas to themselves. The Vegan, of course, was voiceless; and the guards stood about patiently, silent as ever, rock-still except for the slow, almost unceasing, wave of the black, blunt spines. They did not seem even to breathe.

The silence continued while the elevator returned and departed twice more. Its only interruption consisted of occasional faint metallic sounds of indeterminable origin, echoing and re-echoing along the corridors of the vast pile. To Little, they were interesting for the evidence they provided of activity through the place, and therefore of the presence of a very considerable garrison. Nothing was seen to substantiate this surmise, however, although it was possible to view objects at a considerable distance along the well-lighted passage.

The elevator returned for the last time. Little, the few remaining men, and the Vegan entered, accompanied this time by only two of the pentapods, and the upward journey began. The car was lifted by an extremely quiet—or extremely distant—motor; the continuous silence of the place, indeed, was beginning to jar on human nerves. The elevator rose smoothly; there was no sense of motion during the five or six minutes of the journey. Little wondered whether the creatures had some ulterior motive, or were simply economizing on power—if the fort were only two hundred feet high, an elevator journey from ground to roof should take seconds, not minutes. He never discovered the answer.

The car door slid open to reveal another corridor, narrower than the one below. To the right it came to an end twenty yards away where a large circular window allowed the sunlight to enter. Little decided that they must be above the level of the outer wall, since no openings had been visible in it. The wall at this level must be set back some distance, so as to be invisible from a point on the ground near the building.

The party was herded in the opposite direction toward several doors which opened from the hallway. Through a number of these, light even brighter than the daylight was streaming; from others, there emerged only the sound of human voices. The party paused at one of the brightly lighted doorways, and the Vegan turned to Little.

"These are our quarters," telegraphed the creature. "They have permitted us to set up everything we needed for comfort. I would invite you to enter, but you should first find some means of protecting your skin against the ultraviolet radiators we have arranged. Dark goggles, such as Earthmen usually wear on Vega Five, would also be advisable. I shall tell my friends about you; we will converse again whenever possible. If my ears do not deceive me, your people are quartered along this same corridor, so we can meet freely—as you guessed we might. Farewell." The bulky form turned away and hitched itself through the blue-lit entrance.

The creature's auditory organs had not lied; the human crew was found occupying a dozen of the less strongly illuminated rooms along the corridor. Magill, who as quartermaster was senior officer present, had taken charge and had already begun to organize the group when Little and his companions arrived. One chamber had already been set aside as a storeroom and kitchen, and the food was already being placed therein. When the quartermaster caught sight of Little, he wasted no time in greetings.

"Doctor, I seem to recall that the Vegan said we could make several trips for supplies, if necessary. I wish you'd take a dozen men, try to make these creatures understand what you want, and bring up the rest of the food. Also, Denham wants that stove—he promises a regular meal half an hour after you get it here. Can do?" Little nodded; and the officer told off a dozen men to go with him. The group retraced their steps to the elevator.

Several of the pentapods were loitering at this end of the corridor. They made no objection as the doctor investigated the control beside the elevator door, and finally manipulated it; but two of them entered the car with Little and half of his crew, and accompanied them to the ground level. Little obtained one more bit of information as they started down: the elevator controls were like those of an Earthly automatic car, simply a row of buttons. He indicated the lowest, and made a motion as though to push it, meanwhile looking at one of the guards. This creature came over beside him, and with one of its tendrils touched a stud less than a third of the way down the panel. Little smiled. Evidently the fort was more underground than above, and must be a far larger structure than he had thought. It was nice to know.

They waited at the lower level, while one of the men took the car back for the others; then, accompanied by several more of the guards, they went outside. None of the men could discover how the doors of the entrance chamber were manipulated; none of the creatures accompanying them appeared to touch a control of any sort. The piles of supplies and equipment were still in front of the gate; nothing had been touched. Squads of the pentapods were hurrying this way and that around the great ship; some were visible, clinging to nets suspended far overhead against the hull, evidently repairing, cleaning, or inspecting.

A long line of the creatures was passing continually back and forth between one of the ports of the vessel and a small gate, which the men had not previously noticed, in the wall of the fort. They were bearing large crates, which might have contained anything, and various articles of machinery. Little watched them for a moment, then turned his attention to their own supplies.

The men loaded up and returned to the elevator, into which the food was piled. One man started up with the load and the others went back to the piles. This time Little turned his attention to the stove, which the cook had demanded. It had already been worked out of its pile and was awaiting transportation. The doctor first inspected it carefully, however.

It was an extremely versatile piece of equipment. It contained a tiny iron converter of its own, but was also designed to draw power from any normal standard, if desired. Being navy equipment, it also had to be able to work without electric power, if circumstances required precautions against detection; and a tube connection at the back permitted the attachment of a hydrogen or butane tank—there was even a clamp for the tank.

Little saw a rack of three gas tanks standing by a nearby pile, and was smitten with an idea. He detached one of them and fastened it into the stove clamp which, fortunately, it fitted. Four men picked up the stove and carried it inside. The other tanks were removed from the rack and carried after it. They contained, it is needless to say, neither hydrogen nor butane. Little hoped that none of the watching guards had been present at the actual looting of the Gomeisa, and knew where those tanks came from. He had tried to act normally while he had fitted the cylinder and given orders to bring the others.

The elevator had not yet returned when they reached its door. The men set their burden down. To Little's surprise, none of the guards had accompanied them—they had deduced, from the weight and clumsiness of the device the men were carrying, that watching them would be superfluous until the machine was set up. Or, at least, so reasoned the doctor. He took advantage of the opportunity to tell the men to be very careful of the cylinders they were carrying. They asked no questions, though each man had a fairly good idea of the reason for the order. They already knew that the atomic converter of the stove was in working order, and that heating gas was, therefore, superfluous.

When the elevator finally arrived, Little ordered the man who had brought it to help the others bring the rest of the food from outside. There was still a good deal of it, and it might as well be brought in, though a large supply had already accumulated in the storeroom. He finished his orders with:

"You're free to try any smuggling you want, but be careful. They already know what an ion gun looks like, and we have been told that they're very good at guessing. We don't know, of course, what articles besides weapons they don't want us to have; so be careful in taking anything you think they might object to. I'm going to take this load up." He slid the door to and pressed the top button.

The same group of guards were waiting at the top. They watched with interest as several men helped the doctor carry the stove to the room which was to serve as the kitchen. There was not too much space left, for food supplies filled all the corners. Little smiled as he saw them—it seemed as though Magill were anticipating a long stay. He was probably justified.

Denham, the cook, grinned as he saw the stove. He had cleared a narrow space for it and fussily superintended the placing. He looked at the gas tank attached to it, but before he could express any surprise, Little spoke. He kept his voice and expression normal, for several pentapods had followed the stove into the room.

"Act as if the tank were just part of the stove, Den," he said, "but use the iron burner. I assure you that the gas won't heat anything."

Denham kept his face expressionless and said, "O.K., doc. Good work." As though nothing unusual were occurring, he began digging supplies from the surrounding heaps, preparing the promised dinner. The doctor sought out Magill, who had just completed the task of assigning men to the rooms.

"Have you found out how this place is ventilated?" asked Little, as soon as he could get the quartermaster's attention.

"Hello, doc. Food in? Yes, we located the ventilators. Ceiling and floor grilles. Too small to admit a pair of human shoulders, even if we got the bars out."

"I didn't mean that, exactly. Do you know if the same system handles the rest of the building? And whether those grilles keep blowing if we open the window in a room?"

"We can find out the answer to the second, anyway. Come along."

The two entered one of the rooms, which had been set aside as a sleeping room for three men. All the chambers on this side of the corridor had transparent ports opening onto the roof; after some juggling, Magill got one open. Little, standing beneath the ceiling inlet, was gratified to feel the breeze die away. He nodded slowly.

"I think we should form the habit of keeping the windows open," he remarked. "Of course, not being too pointed about it. It may get a trifle cool at night, but we can stand that. By the way, I forgot to have the men bring up those sleeping bags; I'll tell them the next time the elevator comes up. Do you think our faithful shadows"—Little nodded toward the two pentapods standing in the doorway—"would object if we went out on the roof? They let us open the window, and we could go out that way, in a pinch. There must be some more regular exit."

"No harm in trying," replied Magill. He led the way into the corridor, the two watchers moving aside for them, and after a moment's hesitation turned left, away from the elevator. The guards fell in behind. The room they had been in was the last of those occupied by the Earthmen, and several lightless doorways were passed before the end of the passage was reached. They found it similar in arrangement to the other end, containing a large, transparent panel through which was visible a broad expanse of roof.

Magill, who had opened the window in the room, began to examine the edges of the panel. It proved openable, the control being so high above the floor as to be almost out of reach. The pentapods could, without much effort, reach objects eight feet in the air. The quartermaster, with a little fumbling, finally released the catch and pushed the panel open.

The guards made no objection as the men went out on the roof, merely following a few yards behind. This end of the hall opened to the southeast—calling the sunrise point east—away from the ship. From a position a few yards outside the panel, it was evident that the prison quarters occupied a relatively small, rectangular pimple near the north corner of the half-mile-square roof. The men turned left again and passed along the side of the protuberance. Some of the crew saw them through the windows, which Magill beckoned them to open. Denham had already opened his and cooking odors were beginning to pour forth.

Crossing the few yards to the five-foot parapet at the edge of the roof, the men found a series of steps which raised them sufficiently to lean over the two-foot-thick wall. They were facing the forest to which Albee and the others who had escaped had made their dash. From this height they could see down the declivity at its edge, and perceive that a heavy growth of underbrush was present, which would probably seriously impede travel. No sign of the refugees caught the eye.

The bow of the ship protruded from behind the near corner of the structure. Little and Magill moved to this wall and looked down. The line of pentapods was still carrying supplies to the vast ship, whose hull towered well above the level of the two watchers. It hid everything that lay to the northwest. After a few minutes' gaze the officers turned back to the quarters. They were now at the "elevator" end of the superstructure, and found themselves facing the panel which had not yet been opened. Two of the men were visible, watching them from within; and Magill, walking over to the entrance, pointed out the catch which permitted it to open. No outside control was visible.

"The men have come with the rest of the food, sir," said one as soon as the panel opened, "and Denham says that dinner is nearly ready."

"We'll be in shortly," said the quartermaster. "You may tell the men they are free to come out and explore, if they wish."

"I would still like to know if the ventilator intake is on this roof," remarked Little as they walked on. "It must be somewhere, and the wall we saw was perfectly smooth. There doesn't seem to be anything out in the middle of this place, so if it's anywhere, it must be hiding in the shadow of the parapet. Can you see any irregularities near the edges?"

"No," said Magill after straining his eyes in every direction. "I can't. But we're half a mile from two of the walls, and might easily miss such a thing at a much shorter distance. If it's here, one of the men will find it sooner or later. Why do you worry about it, if you want us to use outdoor air directly?"

"I thought it might be a useful item of knowledge," replied Little. "I succeeded in smuggling up my three remaining cylinders of geletane, disguised as part of the stove. I don't suppose there's enough to put the whole garrison out—but still, it would be nice to know their ventilating system."

"Good job, doctor. After we eat we'll find out what else, if anything, the boys succeeded in bringing up, and more or less take inventory. Then perhaps we can arrange some plan for getting out of here. I wish we knew what has become of the Gomeisa; I don't suppose we could manage the controls on that ship outside." Magill made this remark with such perfect seriousness that Little was forced to grin.

"You may be a little optimistic. Keys. Remember the Vegans, who are far from stupid creatures, have been here for some time and have failed to get to first base to date."

"They are handicapped physically, doc. They can't live for long outside without supplementary ultraviolet sources, and they have to plan with that in mind. Furthermore, this gravity is nearly twice that of Vega Five, and they can't move at any rate better than a crawl."

Little was forced to admit the justice of this argument, but remained, in Magill's opinion, pessimistic. He had developed a healthy respect for their captors, along with a slight comprehension of their motives. The trouble was, the Vegan's description of the way the pentapods seemed to guess the purpose of a device before it was completed did not tie in very well with his theory concerning those motives. More thought was indicated. He indulged in it while Magill steered him back to the prison and dinner.

The meal was good. There was no reason why it shouldn't be, of course, since the cook had all the usual supplies and equipment; but Little was slightly surprised to find himself enjoying dinner while in durance vile as much as if he were on his own ship. It didn't seem natural. They ate in the hallway, squatted in a circle in front of the kitchen door. The Vegans, whose quarters were directly opposite, watched from their doorways. They also commented from time to time, but were very seldom answered, since both hands are required to speak Vegan. They would probably have felt slighted if one of them—not the one who had acted as interpreter—had not understood some English. He got about two words in every five, and succeeded in keeping his race in the conversation.

The meal concluded, the meeting of the ways and means committee, which consisted of all human beings and Vegans in the neighborhood, was immediately called to order. The presence of nonmembers, though resented, was perforce permitted, and discussion began under the watchful eyes of eight or ten pentapods. Little, rather than Magill, presided.

"The first thing we need to know," he said, "is everything possible about our five-sided friends. The Vegans have been with them longer, and probably know more than we; but owing to the relative slowness of their speech, we will save their contribution until last. You who understand English may translate the substance of our discussion to your fellows if you wish, but we will hold a second meeting afterward and go over everything in your own language. First, then, will anyone who succeeded in smuggling any weapons or probable-contraband tools up here please report? Keep your hands in your pockets and your eyes on me while you do so; there is a high order of probability that our friends are very good at interpreting gestures—even human gestures."

A man directly across the circle from Little raised a hand. The doctor nodded to him.

"When we were loading food, before we made that break, I dropped my testing kit into my pack first of all. I didn't try to cover it up and I concentrated on boxed articles of food afterward to make it look natural." The speaker was one of Goldthwaite's assistants, a tall fellow with the insignia of a technician's mate. Little knew him fairly well. He had been born on Earth but showed plainly a background of several generations on the colony-planet Regulus Six—big bones, dark skin, quick reactions.

"Good work, Dennis. What is in the kit?"

"Pliers, volt-ammeter, about sixty feet of assorted sizes of silver wire, two-thousand-line grating, midget atomic wire-welder, six plano-convex lenses of various focal lengths, support rod and two mirrors to go with them, and a small stroboscope."

"Item, one portable laboratory," remarked Little. "Congratulations. Leo, I suppose you have outdone your brother?"

Leo Dennis, the twin brother of the first speaker, shook his head. "Just an old-fashioned manual razor. I'll start accepting offers tomorrow." Little smiled and fingered his chin.

"You're too late, unless someone brought scissors to start with. Safety razors weren't built to cope with a ten-day growth, more or less. Never mind, we may find a use for it—it's a cutting tool, anyway. Next?"

There was a pause, with everybody looking expectantly at his neighbor. Evidently the total had been reached. Little spoke again.

"Did anybody try to smuggle something and fail?"

"I tried to salvage Goldy's liquor, and had it taken from me," answered another man. "I guess they're firmly convinced it's lethal. I wish them luck in analyzing the stuff—we never could."

"How far did you get before they took it from you?"

"They let me pick up the bottles that were lying around, and put them in the case; half a dozen of them watched me while I did that. But when I started to carry the case toward the gate—of course, that was some job, as Goldy found out—they all walked up and just took it away. They didn't get violent or anything like that."

"Then it wasn't really a case of detected smuggling; you made no effort to mask your real intentions. Is that right?"

"Yes, sir. I don't quite see how any one could hide either that case or the bottles; I was just sort of hoping against hope."

Little nodded and called for more contributions. A gunner responded.

"I found a couple of cases of grenades and stuck several into my pockets. The next thing I knew, one of the starfish was holding my arms, and another taking them out again. He handled them as though he knew what they were."

"I suppose you checked the safeties before you pocketed the bombs?"

"Of course, sir."

Little nodded wearily. "Of course. And that was enough for our admittedly astute friends. I admit it's usually a very good idea to obey regulations, but there are exceptions to every rule. I think the present circumstances constitute an exception to most of them. Any others?"

Apparently no one else had seen anything he coveted sufficiently to attempt to sneak out of the piles. The doctor didn't care particularly; he believed he had enough data from that source, and an idea was rapidly growing. Unfortunately, the primary principle of that idea required him to learn even more, though not about his captors. Possibly the Vegans could supply the information, but Little was not prepared to bet on it.

Magill closed the discussion by mentioning the anæsthetic which Little had made available, and requesting an early communication of all ideas. The men withdrew into smaller groups, talking in low tones among themselves, and gradually drifted through the doors to their rooms, or out onto the roof. Magill followed to take a small group down again for the sleeping bags.

Little remained with the Vegans. He had a good deal to ask them, and material which could be covered in an hour of verbal conversation would probably take three or four hours of arm-waving. He sat just outside the fan of intense light from one of the doorways, and the creatures formed a semicircle just inside—the door was wide enough for the four of them, since it had been constructed to admit the pentapods. The doctor opened the conversation.

"How long have you been here?" was his first question. It was answered by the individual who had acted as interpreter.

"Since our arrival there have passed about two hundred of the days of this planet. We are not sure just how long they are, but we believe they are about thirty of your hours. We have no idea of the length of time that elapsed between our capture and our arrival at this place, however. We were driving a small private ship on a sightseeing trip to a world which had recently been reported near the galactic center by one of our official exploring vessels, and were near its reported position when we were taken. They simply engulfed us—moved up and dragged our ship into a cargo lock with magnets. We were on their ship a long time before they put us off here and left again, and we were not allowed to obtain any of our belongings except food and ultraviolet lamps until we arrived; so we don't know how long the trip lasted. One of us"—the Vegan indicated the individual—"got up courage enough to venture onto the roof one night and saw what he thinks was the Galaxy; so we believe this world lies in the Cloud. You will be able to tell better for yourselves—you can stand the dark longer than we, and your eyes are better at locating faint details."

"You may be right. We were heading toward the Cloud when we were taken," answered Little. "How freely have you been permitted to move about this fort?"

"We may go almost anywhere above ground level," was the answer. "Some of these watchers"—a supple antenna gestured toward the ever-present guards—"are always with us, and they prevent us from taking the elevators any lower. Then there are a few rooms on the upper levels which are always sealed, and two or three which are open but whose thresholds we are not permitted to cross."

"How do they prevent your entering?"

"They simply get in front of us, and push us back if we persist. They have never used violence on us. They never need to; we are in no position to dispute their wishes. There is no comparison between them and us physically, and we are very much out of our natural environment."

"Have you been able to deduce the nature or purpose of the rooms from which you are barred?"

"We assume that they are control rooms, communication offices, or chart rooms. One of them contains several devices which look like ordinary television screens. Whether they are for long-range use or are merely part of a local system, of course we cannot tell." Little pondered for several moments before speaking again.

"You mentioned constructing several devices to aid in escape, only to have them taken away from you just before they were completed. Could you give me more details on just what happened? What were you doing, and at what stage were you interrupted? How did you expect to get away from the planet?"

"We did not expect to get away. We just wanted to make them go, so we could take over the fort. When we disconnected their tube lights to put in our own, he"—indicating the creature beside him—"managed to retain a sample of the tube. On its walls were absorbed layers of several gases, but neon was the chief component. We had smuggled in the neutrino converters and stabilizers from our ship"—and Keys said these fellows were helpless, thought Little—"and it occurred to us that we might set up a neon-oxygen reaction which would flood the place with ultraviolet. We had already noticed that they could not stand it any better than you. The half life of the process would have been of the order of twelve hours, which should have driven them out for a period of time ample for our purpose. A neutrino jet of very moderate power, correctly tuned, could easily have catalyzed such a reaction in every light tube in the place. We had built the projector, disguising it as another ultraviolet lamp, and were connecting the converter when about fifty of the guards dived in, took the whole thing away, and ran out before the lamps we already had going could hurt them."

Little heroically forbore to ask the creatures why they had not smuggled in their ship while they were about it and flown away. The Vegans wouldn't have appreciated the humor.

"I believe I understand the purpose of the actions of these creatures," he said. "But some of their characteristics still puzzle me. Their teamwork is perfect, better than that of well-trained human fighters, but if my idea is correct their technical knowledge is inferior to ours. I have already mentioned to my captain their apparent lack of conceit—that is also based on my guess as to their motives in capturing us. One thing, however, I do not understand at all. How do they communicate? I have always been reluctant to fall back on the 'explanation' of telepathy; there are reasons which make me doubt that it can ever be a satisfactory substitute for a language."

The Vegans looked at him for a moment, astonishment reflected in the tenseness of their antennae.

"You do not see how they talk?" signaled one at length. "That is the first and only thing we have been able to appreciate in their entire make-up."

Little leaned forward. "Explain, please," he waved tensely. "That may be the most important thing any of us has yet ascertained."

The Vegans explained at length. Great length. The recital was stretched out by Little's frequent questions, and once or twice delayed by his imperfect comprehension of the Vegan language. The sun was low in the west when the conversation ended, but the doctor had at last what he believed to be a complete mental picture of the habits, thoughts, and nature of the pentapods, and he had more than the glimmerings of a plan which might set the human and Vegan prisoners free once more. He hoped.

He left his nonhuman allies, and sought out Magill. He found him at the western corner of the roof, examining the landscape visible beyond the tail of the spaceship. A couple of pentapods were on hand, as usual. Leo Dennis was making himself useful, sketching the western skyline on a pad he carried, with the apparent intention of marking the sunset point. Magill had evidently decided that an assistant navigator should be able to get his own location on a planet's surface as well as in space. Dennis was slightly handicapped by a total lack of instruments, but was doing his best. Little approached the quartermaster.

"Has anything new turned up, Keys?"

The officer shook his head without turning. "The men are all over the roof, to see if there are any ventilator intakes or anything else. One of them pointed out that the lack of superstructure suggested that the roof might be used as a landing place for atmosphere craft, and found some blast marks to back up the idea. No one else has made any worth-while reports. If there are any aircraft, though, I'd like to know where they stow them."

"It might help, though I hope we won't be driven to using them. I suppose the boys have their eyes open for large, probably level-set trapdoors in the roof. But what I wanted to find out was: with whom am I sharing a room?"

"Don't recall, offhand," replied Magill. "It doesn't matter greatly. If there is any one in particular you want—or don't want—to be with, you're at liberty to trade with someone. I told the boys that."

"Thanks. I want to spend some time with the Dennis boys, without making it too obvious. I suppose they're already together. By the way, seeing I'm still a medical officer, has anyone reported sick? The air is just a shade on the thin side, and we've been breathing it long enough for effects to show, if there are going to be any."

Magill shook his head negatively, and Little strolled over to Leo, who had completed his sketch and was trying to mark the position of the sun at five-minute intervals. He was wearing one of the few watches possessed by the party. He was perfectly willing to have his erstwhile roommate replaced by the doctor, especially when Little promised work to be done. He agreed to speak to his brother and to Cauley, who had originally been assigned to their room.

"Tell Arthur to bring his pack, with the kit he sneaked along," added the doctor. "We will probably have use for it." Leo nodded, grinning, and resumed his attempts to fix the position of an object, much too bright to view directly, which had an angular breadth on the order of half a degree. He didn't appear discouraged yet.

Little wandered off across the roof, occasionally meeting and speaking to one of the men. Morale seemed to be good, he noted with relief. He had always considered that to be part of the business of a medical officer, since it was, after all, directly reflected in the health of the men.

A motion in the direction of the setting sun caught his eye. He turned to face it and saw a narrow, dazzling crescent low in the western sky, a crescent that rose and grew broader as he watched. The planet had a satellite, like Mars, so close that its period of revolution was less than one of its own days. Little wondered if a body so close to the planet might not prove useful. He filed the thought away for future reference.

The sun set as he watched, and he realized he had been right about the thinness of the air. Darkness shut down almost at once. The moon sprang into brilliance—brilliance that was deceptive, for details on the landscape were almost impossible to make out. Stars, scattered at random over the sky, began to appear; and as the last traces of daylight faded away, there became visible, at first hazily and then clear and definite, the ghostly shape of the Galaxy. Its sprawling spiral arms stretched across a quarter of the sky, the bulk of the system inclined some thirty degrees from the edge-on position—just enough to show off the tracing of the great lanes of dust that divided the arms.