GEORGE ALLEN,

SUNNYSIDE, ORPINGTON, KENT.

1872.

[1]

[1]

My Friends,

1st January, 1872.

I would wish you a happy New Year, if I thought my wishes likely to be of the least use. Perhaps, indeed, if your cap of liberty were what you always take it for, a wishing cap, I might borrow it of you, for once; and be so much cheered by the chime of its bells, as to wish you a happy New Year, whether you deserved one or not: which would be the worst thing I could possibly bring to pass for you. But wishing cap, belled or silent, you can lend me none; and my wishes having proved, for the most part, vain for myself, except in making me wretched till I got rid of them, I will not present you with anything which I have found to be of so little worth. But if you trust more to any one else’s than mine, let me advise your requesting them to wish that you may deserve a happy New Year, whether you get one or not.

To some extent, indeed, that way, you are sure to [2]get it: and it will much help you towards the seeing such way if you would make it a practice in your talk always to say you “deserve” things, instead of that you “have a right” to them. Say that you “deserve” a vote,—“deserve” so much a day, instead of that you have “a right to” a vote, etc. The expression is both more accurate and more general; for if it chanced, which heaven forbid,—but it might be,—that you deserved a whipping, you would never think of expressing that fact by saying you “had a right to” a whipping; and if you deserve anything better than that, why conceal your deserving under the neutral term, “rights”; as if you never meant to claim more than might be claimed also by entirely nugatory and worthless persons? Besides, such accurate use of language will lead you sometimes into reflection on the fact, that what you deserve, it is not only well for you to get, but certain that you ultimately will get; and neither less nor more.

Ever since Carlyle wrote that sentence about rights and mights, in his “French Revolution,” all blockheads of a benevolent class have been declaiming against him, as a worshipper of force. What else, in the name of the three Magi, is to be worshipped? Force of brains, Force of heart, Force of hand;—will you dethrone these, and worship apoplexy?—despise the spirit of Heaven, and worship phthisis? Every condition of idolatry is summed in the one broad wickedness of refusing to worship Force, and resolving to worship No-Force;—[3]denying the Almighty, and bowing down to four-and-twopence with a stamp on it.

But Carlyle never meant in that place to refer you to such final truth. He meant but to tell you that before you dispute about what you should get, you would do well to find out first what is to be gotten. Which briefly is, for everybody, at last, their deserts, and no more.

I did not choose, in beginning this book a year since, to tell you what I meant it to become. This, for one of several things, I mean,—that it shall put before you so much of the past history of the world, in an intelligible manner, as may enable you to see the laws of Fortune or Destiny, “Clavigera,” Nail bearing; or, in the full idea, nail-and-hammer bearing; driving the iron home with hammer-stroke, so that nothing shall be moved; and fastening each of us at last to the Cross we have chosen to carry. Nor do I doubt being able to show you that this irresistible power is also just; appointing measured return for every act and thought, such as men deserve.

And that being so, foolish moral writers will tell you that whenever you do wrong you will be punished, and whenever you do right rewarded: which is true, but only half the truth. And foolish immoral writers will tell you that if you do right, you will get no good; and if you do wrong dexterously, no harm. Which, in their sense of good and harm, is true also, but, even in [4]that sense, only half the truth. The joined and four-square truth is, that every right is exactly rewarded, and every wrong exactly punished; but that, in the midst of this subtle, and, to our impatience, slow, retribution, there is a startlingly separate or counter ordinance of good and evil,—one to this man, and the other to that,—one at this hour of our lives, and the other at that,—ordinance which is entirely beyond our control; and of which the providential law, hitherto, defies investigation.

To take an example near at hand, which I can answer for. Throughout the year which ended this morning, I have been endeavouring, more than hitherto in any equal period, to act for others more than for myself: and looking back on the twelve months, am satisfied that in some measure I have done right. So far as I am sure of that, I see also, even already, definitely proportioned fruit, and clear results following from that course;—consequences simply in accordance with the unfailing and undeceivable Law of Nature.

That it has chanced to me, in the course of the same year, to have to sustain the most acute mental pain yet inflicted on my life;—to pass through the most nearly mortal illness;—and to write your Christmas letter beside my mother’s dead body, are appointments merely of the hidden Fors, or Destiny, whose power I mean to trace for you in past history, being hitherto, in the reasons of it, indecipherable, yet palpably following [5]certain laws of storm, which are in the last degree wonderful and majestic.

Setting this Destiny, over which you have no control whatsoever, for the time, out of your thoughts, there remains the symmetrical destiny, over which you have control absolute—namely, that you are ultimately to get—exactly what you are worth.

And your control over this destiny consists, therefore, simply in being worth more or less, and not at all in voting that you are worth more or less. Nay, though you should leave voting, and come to fighting, which I see is next proposed, you will not, even that way, arrive any nearer to your object—admitting that you have an object, which is much to be doubted. I hear, indeed, that you mean to fight for a Republic, in consequence of having been informed by Mr. John Stuart Mill, and others, that a number of utilities are embodied in that object. We will inquire into the nature of this object presently, going over the ground of my last January’s letter again; but first, may I suggest to you that it would be more prudent, instead of fighting to make us all republicans against our will,—to make the most of the republicans you have got. There are many, you tell me, in England,—more in France, a sprinkling in Italy,—and nobody else in the United States. What should you fight for, being already in such prevalence? Fighting is unpleasant, now-a-days, however glorious, what with mitrailleuses, torpedoes, and [6]mismanaged commissariat. And what, I repeat, should you fight for? All the fighting in the world cannot make us Tories change our old opinions, any more than it will make you change your new ones. It cannot make us leave off calling each other names if we like—Lord this, and the Duke of that, whether you republicans like it or not. After a great deal of trouble on both sides, it might, indeed, end in abolishing our property; but without any trouble on either side, why cannot your friends begin by abolishing their own? Or even abolishing a tithe of their own? Ask them to do merely as much as I, an objectionable old Tory, have done for you. Make them send you in an account of their little properties, and strike you off a tenth, for what purposes you see good; and for the remaining nine-tenths, you will find clue to what should be done in the ‘Republican’ of last November, wherein Mr. W. Riddle, C.E., “fearlessly states” that all property must be taken under control; which is, indeed, precisely what Mr. Carlyle has been telling you these last thirty years, only he seems to have been under an impression, which I certainly shared with him, that you republicans objected to control of any description. Whereas if you let anybody put your property under control, you will find practically he has a good deal of hold upon you also.

You are not all agreed upon that point perhaps? But you are all agreed that you want a Republic. Though England is a rich country, having worked herself literally [7]black in the face to become so, she finds she cannot afford to keep a Queen any longer;—is doubtful even whether she would not get on better Queenless; and I see with consternation that even one of my own personal friends, Mr. Auberon Herbert, rising the other day at Nottingham, in the midst of great cheering, declares that, though he is not in favour of any immediate change, yet, “if we asked ourselves what form of government was the most reasonable, the most in harmony with ideas of self-government and self-responsibility, and what Government was most likely to save us from unnecessary divisions of party, and to weld us into one compact mass, he had no hesitation in saying the weight of argument was in favour of a Republic.”1

Well, suppose we were all welded into a compact mass. Might it not still be questionable what sort of a mass we were? After any quantity of puddling, iron is still nothing better than iron;—in any rarity of dispersion, gold-dust is still gold. Mr. Auberon Herbert thinks it desirable that you should be stuck together. Be it so; but what is there to stick? At this time of year, doubtless, some of your children, interested generally in production of puddings, delight themselves, to your great annoyance, with speculative pudding in the gutter; and enclose, between unctuous tops and bottoms, imaginary mince. But none of them, I suppose, deliberately come in to their mothers, at cooking-time, [8]with materials for a treat on Republican principles. Mud for suet—gravel for plums—droppings of what heaven may send for flavour;—“Please, mother, a towel, to knot it tight—(or, to use Mr. Herbert’s expression, “weld it into a compact mass”)—Now for the old saucepan, mother; and you just lay the cloth!”

My friends, I quoted to you last year the foolishest thing, yet said, according to extant history, by lips of mankind—namely, that the cause of starvation is quantity of meat.2 But one can yet see what the course of foolish thought was which achieved that saying: whereas, though it is not absurd to quite the same extent to believe that a nation depends for happiness and virtue on the form of its government, it is more difficult to understand how so large a number of otherwise rational persons have been beguiled into thinking so. The stuff of which the nation is made is developed by the effort and the fate of ages: according to that material, such and such government becomes possible to it, or impossible. What other form of government you try upon it than the one it is fit for, necessarily comes to nothing; and a nation wholly worthless is capable of none.

Notice, therefore, carefully Mr. Herbert’s expression “welded into a compact mass.” The phrase would be likely enough to occur to any one’s mind, in a midland district; and meant, perhaps, no more than if the [9]speaker had said “melted,” or “blended” into a mass. But whether Mr. Herbert meant more or not, his words meant more. You may melt glass or glue into a mass, but you can only weld, or wield, metal. And are you sure that, if you would have a Republic, you are capable of being welded into one? Granted that you are no better than iron, are you as good? Have you the toughness in you? and can you bear the hammering? Or, would your fusion together,—your literal con-fusion—be as of glass only, blown thin with nitrogen, and shattered before it got cold?

Welded Republics there indeed have been, ere now, but they ask first for bronze, then for a hammerer, and mainly, for patience on the anvil. Have you any of the three at command,—patience, above all things, the most needed, yet not one of your prominent virtues? And, finally, for the cost of such smith’s work,—My good friends, let me recommend you, in that point of view, to keep your Queen.

Therefore, for your first bit of history this year, I will give you one pertinent to the matter, which will show you how a monarchy, and such a Republic as you are now capable of producing, have verily acted on special occasion, so that you may compare their function accurately.

The special occasion that I choose shall be the most solemn of all conceivable acts of Government; the adjudging and execution of the punishment of Death. [10]The two examples of it shall be, one under an absolutely despotic Monarchy, acting through ministers trained in principles of absolute despotism; and the other in a completely free Republic, acting by its collective wisdom, and in association of its practical energies.

The example of despotism shall be taken from the book which Mr. Froude most justly calls “the prose epic of the English nation,” the records compiled by Richard Hakluyt, Preacher, and sometime Student of Christchurch in Oxford, imprinted at London by Ralph Newberie, anno 1599, and then in five volumes, quarto, in 1811, two hundred and seventy copies only of this last edition being printed.

These volumes contain the original—usually personal,—narratives of the earliest voyages of the great seamen of all countries,—the chief part of them English; who “first went out across the unknown seas, fighting, discovering, colonizing; and graved out the channels, paving them at last with their bones, through which the commerce and enterprise of England has flowed out over all the world.”3 I mean to give you many pieces to read out of this book, which Mr. Froude tells you truly is your English Homer; this piece, to our present purpose, is already quoted by him in his essay on England’s forgotten worthies; among whom, far-forgotten [11]though they be, most of you must have heard named Sir Francis Drake. And of him, it now imports you to know this much: that he was the son of a clergyman, who fled into Devonshire to escape the persecution of Henry VIII. (abetted by our old friend, Sir Thomas of Utopia)—that the little Frank was apprenticed by his father to the master of a small vessel trading to the Low Countries; and that as apprentice, he behaved so well that his master, dying, left him his vessel, and he begins his independent life with that capital. Tiring of affairs with the Low Countries, he sells his little ship, and invests his substance in the new trade to the West Indies. In the course of his business there, the Spaniards attack him, and carry off his goods. Whereupon, Master Francis Drake, making his way back to England, and getting his brother John to join with him, after due deliberation, fits out two ships, to wit, the Passover of 70 tons, and the Swan of 24, with 73 men and boys (both crews, all told,) and a year’s provision; and, thus appointed, Master Frank in command of the Passover, and Master John in command of the Swan, weigh anchor from Plymouth on the 24th of May, 1572, to make reprisals on the most powerful nation of the then world. And making his way in this manner over the Atlantic, and walking with his men across the Isthmus of Panama, he beholds “from the top of a very high hill, the great South Sea, on which no English ship had ever sailed. Whereupon, he lifted [12]up his hands to God, and implored His blessing on the resolution which he then formed, of sailing in an English ship on that sea.” In the meantime, building some light fighting pinnaces, of which he had brought out the material in the Passover, and boarding what Spanish ships he can, transferring his men to such as he finds most convenient to fight in, he keeps the entire coast of Spanish America in hot water for several months; and having taken and rifled, between Carthagena and Nombre de Dios (Name of God) more than two hundred ships of all sizes, sets sail cheerfully for England, arriving at Plymouth on the 9th of August, 1573, on Sunday, in the afternoon; and so much were the people delighted with the news of their arrival, that they left the preacher, and ran in crowds to the quay, with shouts and congratulations.

He passes four years in England, explaining American affairs to Queen Elizabeth and various persons at court; and at last in mid-life, in the year 1577, he obtains a commission from the Queen, by which he is constituted Captain-general of a fleet of five ships: the Pelican, admiral, 100 tons, his own ship; the Elizabeth, vice-admiral, 80 tons; the Swan, 50 tons; Marigold, 30; and Christopher (Christbearer) 15; the collective burden of the entire fleet being thus 275 tons; its united crews 164 men, all told: and it carries whatever Sir Francis thought “might contribute to raise in those nations, with whom he should have any intercourse, the highest [13]ideas of the politeness and magnificence of his native country. He, therefore, not only procured a complete service of silver for his own table, and furnished the cook-room with many vessels of the same metal, but engaged several musicians to accompany him.”

I quote from Johnson’s life of him,—you do not know if in jest or earnest? Always in earnest, believe me, good friends. If there be jest in the nature of things, or of men, it is no fault of mine. I try to set them before you as they truly are. And Sir Francis and his crew, musicians and all, were in uttermost earnest, as in the quiet course of their narrative you will find. For arriving on the 20th of June, 1578, “in a very good harborough, called by Magellan Port St. Julian, where we found a gibbet standing upon the maine, which we supposed to be the place where Magellan did execution upon his disobedient and rebellious company; … in this port our Generall began to inquire diligently of the actions of M. Thomas Doughtie, and found them not to be such as he looked for, but tending rather to contention or mutinie, or some other disorder, whereby (without redresse) the successe of the voyage might greatly have bene hazarded; whereupon the company was called together and made acquainted with the particulars of the cause, which were found, partly by Master Doughtie’s owne confession, and partly by the evidence of the fact, to be true; which when our Generall saw, although his [14]private affection to M. Doughtie (as hee then in the presence of us all sacredly protested) was great, yet the care he had of the state of the voyage, of the expectation of her Maiestie, and of the honour of his countrey, did more touch him (as, indeede, it ought) than the private respect of one man: so that, the cause being thoroughly heard, and all things done in good order, as neere as might be to the course of our lawes in England, it was concluded that M. Doughtie should receive punishment according to the qualitie of the offence: and he, seeing no remedie but patience for himselfe, desired before his death to receive the Communion, which he did at the hands of M. Fletcher, our Minister, and our Generall himselfe accompanied him in that holy action: which being done, and the place of execution made ready, hee having embraced our Generall, and taken his leave of all the companie, with prayer for the Queen’s Maiestie and our realme, in quiet sort laid his head to the blocke, where he ended his life. This being done, our Generall made divers speaches to the whole company, persuading us to unitie, obedience, love, and regard of our voyage; and for the better confirmation thereof, willed evry man the next Sunday following to prepare himselfe to receive the Communion, as Christian brethren and friends ought to doe, which was done in very reverent sort, and so with good contentment every man went about his businesse.” [15]

Thus pass judgment and execution, under a despotic Government and despotic Admiral, by religious, or, it may be, superstitious, laws.

You shall next see how judgment and execution pass on the purest republican principles; every man’s opinion being held as good as his neighbour’s; and no superstitious belief whatsoever interfering with the wisdom of popular decision, or the liberty of popular action. The republicanism shall also be that of this enlightened nineteenth century: in other respects the circumstances are similar; for the event takes place during an expedition of British—not subjects, indeed, but quite unsubjected persons,—acknowledging neither Queen nor Admiral,—in search, nevertheless, of gold and silver, in America, like Sir Francis himself. And to make all more precisely illustrative, I am able to take the account of the matter from the very paper which contained Mr. Auberon Herbert’s speech, the ‘Pall Mall Gazette’ of 5th December last. In another column, a little before the addresses of the members for Nottingham, you will therein find, quoted from the ‘New York Tribune,’ the following account of some executions which took place at “the Angels” (Los Angeles), California, on the 24th October.

“The victims were some unoffending Chinamen, the executioners were some ‘warm-hearted and impulsive’ Irishmen, assisted by some Mexicans. It seems that [16]owing to an impression that the houses inhabited by the Chinamen were filled with gold, a mob collected in front of a store belonging to one of them named Yo Hing with the object of plundering it. The Chinamen barricaded the building, shots were fired, and an American was killed. Then commenced the work of pillage and murder. The mob forced an entrance, four Chinamen were shot dead, seven or eight were wounded, and seventeen were taken and hanged. The following description of the hanging of the first victim will show how the executions were conducted:—

“Weng Chin, a merchant, was the first victim of hanging. He was led through the streets by two lusty Irishmen, who were cheered on by a crowd of men and boys, most of Irish and Mexican birth. Several times the unfortunate Chinaman faltered or attempted to extricate himself from the two brutes who were leading him, when a half-drunken Mexican in his immediate rear would plunge the point of a large dirk knife into his back. This, of course, accelerated his speed, but never a syllable fell from his mouth. Arriving at the eastern gate of Tomlinson’s old lumber yard, just out of Temple Street, hasty preparations for launching the inoffensive man into eternity were followed by his being pulled up to the beam with a rope round his neck. He didn’t seem to ‘hang right,’ and one of the Irishmen got upon his shoulders and jumped upon them, breaking his collar-bone. What with shots, stabs, and strangulation, and other modes of civilized torture, the victim was ‘hitched up’ for dead, and the crowd gave vent to their savage delight in demoniac yells and a jargon which too plainly denoted their Hibernian nationality.

[17]

“One victim, a Chinese physician of some celebrity, Dr. Gnee Sing, offered his tormentors 4,000 dollars in gold to let him go. His pockets were immediately cut and ransacked, a pistol-shot mutilated one side of his face ‘dreadfully,’ and he too was ‘stretched up’ with cheers. Another wretched man was jerked up with great force against the beam, and the operation repeated until his head was broken in a way we cannot describe. Three Chinese, one a youth of about fifteen years old, picked up at random, and innocent of even a knowledge of the disturbance, were hanged in the same brutal manner. Hardly a word escaped them, but the younger one said, as the rope was being placed round his neck, ‘Me no ’fraid to die; me velly good China boy; me no hurt no man.’ Three Chinese boys who were hanged ‘on the side of a waggon’ struggled hard for their lives. One managed to lay hold of the rope, upon which two Irishmen beat his hands with clubs and pistols till he released his hold and fell into a ‘hanging position.’ The Irishmen then blazed away at him with bullets, and so put an end to his existence.”

My republican friends—or otherwise than friends, as you choose to have it—you will say, I presume, that this comparison of methods of magistracy is partial and unfair? It is so. All comparisons—as all experiments—are unfair till you have made more. More you shall make with me; and as many as you like, on your own [18]side. I will tell you, in due time, some tales of Tory gentlemen who lived, and would scarcely let anybody else live, at Padua and Milan, which will do your hearts good. Meantime, meditate a little over these two instances of capital justice, as done severally by monarchists and republicans in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries; and meditate, not a little, on the capital justice which you have lately accomplished yourselves in France. You have had it all your own way there, since Sedan. No Emperor to paralyze your hands any more, or impede the flow of your conversation. Anything, since that fortunate hour, to be done,—anything to be said, that you liked; and in the midst of you, found by sudden good fortune, two quiet honest and brave men; one old and one young, ready to serve you with all their strength, and evidently of supreme gifts in the way of service,—Generals Trochu and Rossel. You have exiled one, shot the other,4 and, but that, as I told you, my wishes are of no account that I know of, I should wish you joy of your “situation.”

Believe me, faithfully yours,

JOHN RUSKIN. [1]

1 See ‘Pall Mall Gazette,’ Dec. 5th, 1871. ↑

2 Letter IV. p. 21. Compare Letter V. p. 5; and observe, in future references of this kind I shall merely say, IV. 21; V. 5, etc. ↑

3 J. A. Froude, ‘Short Studies on Great Subjects.’ Longmans, 1867. Page 297. ↑

4 “You did not shoot him”? No; my expression was hasty; you only stood by, in a social manner, to see him shot;—how many of you?—and so finely organized as you say you are! ↑

Denmark Hill,

1st February, 1872.

My Friends,

In going steadily over our ground again, roughly broken last year, you see that, after endeavouring, as I did last month, to make you see somewhat more clearly the absurdity of fighting for a Holy Republic before you are sure of having got so much as a single saint to make it of, I have now to illustrate farther the admission made in page 8 of my first Letter, that even the most courteous and perfect Monarchy cannot make an unsaintly life into a saintly one, nor constitute thieving, for instance, an absolutely praiseworthy profession, however glorious or delightful. It is indeed more difficult to show this in the course of past history than any other moral truth whatsoever. For, without doubt or exception, [2]thieving has not only hitherto been the most respected of professions, but the most healthy, cheerful, and in the practical outcome of it, though not in theory, even the honestest, followed by men. Putting the higher traditional and romantic ideals, such as that of our Robin Hood, and the Scottish Red Robin, for the time, aside, and keeping to meagre historical facts, could any of you help giving your heartiest sympathy to Master Francis Drake, setting out in his little Paschal Lamb to seek his fortune on the Spanish seas, and coming home, on that happy Sunday morning, to the unspeakable delight of the Cornish congregation? Would you like to efface the stories of Edward III., and his lion’s whelp, from English history; and do you wish that instead of pillaging the northern half of France, as you read of them in the passages quoted in my fourth Letter, and fighting the Battle of Creçy to get home again, they had stayed at home all the time; and practised, shall we say, upon the flute, as I find my moral friends think Frederick of Prussia should have done? Or would you have chosen that your Prince Harry should never have played that set with his French tennis-balls, which won him Harfleur, and Rouen, and Orleans, and other such counters, which we might have kept, to this day perhaps, in our pockets, but for the wood maid of Domremy? Are you ready, even now, in the height of your morality, to give back India to the Brahmins and their [3]cows, and Australia to her aborigines and their apes? You are ready? Well, my Christian friends, it does one’s heart good to hear it, providing only you are quite sure you know what you are about. “Let him that stole steal no more; but rather let him labour.” You are verily willing to accept that alternative? I inquire anxiously, because I see that your Under Secretary of State for India, Mr. Grant Duff, proposes to you, in his speech at Elgin, not at all as the first object of your lives to be honest; but, as the first, to be rich, and the second to be intelligent: now when you have all become rich and intelligent, how do you mean to live? Mr. Grant Duff, of course, means by being rich that you are each to have two powdered footmen; but then who are to be the footmen, now that we mustn’t have blacks? And granting you all the intelligence in the world on the most important subjects,—the spots in the sun, or the nodes of the moon, as aforesaid,—will that help you to get your dinner, unless you steal it in the old fashion? The subject is indeed discussed with closer definition than by Mr. Grant Duff, by Mr. William Riddle, C.E., the authority I quoted to you for taking property “under control.” You had better perhaps be put in complete possession of his views, as stated by himself in the ‘Republican,’ of December last; the rather, as that periodical has not had, according to Mr. Riddle, hitherto a world-wide circulation:— [4]

“THE SIMPLE AND ONLY REMEDY FOR THE WANTS OF NATIONS.”

“It is with great grief that I hear that your periodical finds but a limited sale. I ask you to insert a few words from me, which may strike some of your readers as being important. These are all in all. What all nations want, Sir, are—1, Shelter; 2, Food; 3, Clothes; 4, Warmth; 5, Cleanliness; 6, Health; 7, Love; 8, Beauty. These are only to be got in one way. I will state it. 1.—An International Congress must make a number of steam engines, or use those now made, and taking all property under its control (I fearlessly state it) must roll off iron and glass for buildings to shelter hundreds of millions of people. 2.—Must, by such engines, make steam apparatus to plough immense plains of wheat, where steam has elbow-room abroad; must make engines to grind it on an enormous scale, first fetching it in flat-bottomed ships, made of simple form, larger than the Great Eastern, and of simple form of plates, machine fastened; must bake it by machine ovens commensurate. 3.—Machine looms must work unattended night and day, rolling off textile yarns and fabrics, and machines must make clothes, just as envelopes are knocked off. 4.—Machinery must do laundress work, iron and mangling; and, in a word, our labour must give place to machinery, laid down in gigantic factories on common-sense principles [5]by an International leverage. This is the education you must inculcate. Then man will be at last emancipated. All else is utter bosh, and I will prove it so when and wherever I can get the means to lecture.

“Wm. Riddle, C.E.

“South Lambeth, Nov. 2.”

Unfortunately, till those means can be obtained, (may it be soon), it remains unriddled to us on what principles of “international leverage” the love and beauty are to be provided. But the point I wish you mainly to notice is, that for this general emancipation, and elbow-room for men and steam, you are still required to find “immense plains of wheat abroad.” Is it not probable that these immense plains may belong to somebody “abroad” already? And if not, instead of bringing home their produce in flat-bottomed ships, why not establish, on the plains themselves, your own flat-bottomed—I beg pardon,—flat-bellied, persons, instead of living here in glass cases, which surely, even at the British Museum, cannot be associated in your minds with the perfect manifestation of love and beauty? It is true that love is to be measured, in your perfected political economy, by rectangular area, as you will find on reference to the ingenious treatise of Mr. W. Stanley Jevons, M.A., Professor of Logic and Political Economy in Owens College, Manchester, who informs you, among other interesting facts, that pleasure and pain “are the ultimate objects of the calculus of [6]economy,” and that a feeling, whether of pleasure or pain, may be regarded as having two dimensions—namely, in duration and intensity, so that the feeling, say of a minute, “may be represented by a rectangle whose base corresponds to the duration of a minute, and whose height is proportioned to the intensity.”1 The collective area of the series of rectangles will mark the “aggregate of feeling generated.”

But the Professor appears unconscious that there is a third dimension of pleasure and pain to be considered, besides their duration and intensity; and that this third dimension is to some persons, the most important of all—namely, their quality. It is possible to die of a rose in aromatic pain; and, on the contrary, for flies and rats, even pleasure may be the reverse of aromatic. There is swine’s pleasure, and dove’s; villain’s pleasure, and gentleman’s, to be arranged, the Professor will find, by higher analysis, in eternally dissimilar rectangles.

My friends, the follies of Modern Liberalism, many and great though they be, are practically summed in this denial or neglect of the quality and intrinsic value of things. Its rectangular beatitudes, and spherical [7]benevolences,—theology of universal indulgence, and jurisprudence which will hang no rogues, mean, one and all of them, in the root, incapacity of discerning, or refusal to discern, worth and unworth in anything, and least of all in man; whereas Nature and Heaven command you, at your peril, to discern worth from unworth in everything, and most of all in man. Your main problem is that ancient and trite one, “Who is best man?” and the Fates forgive much,—forgive the wildest, fiercest, cruellest experiments,—if fairly made for the determination of that. Theft and blood-guiltiness are not pleasing in their sight; yet the favouring powers of the spiritual and material world will confirm to you your stolen goods; and their noblest voices applaud the lifting of your spear, and rehearse the sculpture of your shield, if only your robbing and slaying have been in fair arbitrament of that question, “Who is best man?” But if you refuse such inquiry, and maintain every man for his neighbour’s match,2—if you give vote to the simple, and liberty to the vile, the powers of those spiritual and material worlds in due time present you inevitably with the same problem, [8]soluble now only wrong side upwards; and your robbing and slaying must be done then to find out “Who is worst man?” Which, in so wide an order of merit, is, indeed, not easy; but a complete Tammany Ring, and lowest circle in the Inferno of Worst, you are sure to find, and to be governed by.

And you may note that the wars of men, in this winnowing or sifting function, separate themselves into three distinct stages. In healthy times of early national development, the best men go out to battle, and divide the spoil; in rare generosity, perhaps, giving as much to those who tarry by the stuff, as to those who have followed to the field. In the second, and more ingenious stage, which is the one we have reached now in England and America, the best men still go out to battle, and get themselves killed,—or, at all events, well withdrawn from public affairs,—and the worst stop at home, manage the government, and make money out of the commissariat. (See § 124 of ‘Munera Pulveris,’ and my note there on the last American War.) Then the third and last stage, immediately preceding the dissolution of any nation, is when its best men (such as they are)—stop at home too!—and pay other people to fight for them. And this last stage, not wholly reached in England yet, is, however, within near prospect; at least, if we may again on this point refer to, and trust, the anticipations of Mr. Grant Duff, ‘who racks his brains, without success, to think of any [9]probable combination of European events in which the assistance of our English force would be half so useful to our allies as money.’

Next month I will give you some farther account of the operations in favour of their Italian allies in the fourteenth century, effected by the White company under Sir John Hawkwood;—(they first crossed the Alps with a German captain, however,)—not at all consisting in disbursements of money; but such, on the contrary, as to obtain for them—(as you read in my first Letter) the reputation, with good Italian judges, of being the best thieves known at the time. It is in many ways important for you to understand the origin and various tendencies of mercenary warfare; the essential power of which, in Christendom, dates, singularly enough, from the struggle of the free burghers of Italy with a Tory gentleman, a friend of Frederick II. of Germany; the quarrel, of which you shall hear the prettiest parts, being one of the most dramatic and vital passages of mediæval history. Afterwards we shall be able to examine, more intelligently, the prospects in store for us according to the—I trust not too painfully racked,—brains of our Under Secretary of State. But I am tired to-day of following modern thought in these unexpectedly attenuated conditions; and I believe you will also be glad to rest, with me, by reading a few words of true history of such life as, in here and there a hollow of the rocks of Europe, just persons have sometimes [10]lived, untracked by the hounds of war. And in laying them before you, I begin to give these letters the completed character I intend for them; first, as it may seem to me needful, commenting on what is passing at the time, with reference always to the principles and plans of economy I have to set before you; and then collecting out of past literature, and in occasional frontispieces or woodcuts, out of past art, what may confirm or illustrate things that are for ever true: choosing the pieces of the series so that, both in art and literature, they may become to you in the strictest sense, educational, and familiarise you with the look and manner of fine work.

I want you, accordingly, now to read attentively some pieces of agricultural economy, out of Marmontel’s ‘Contes Moraux,’—(we too grandly translate the title into ‘Moral Tales,’ for the French word Mœurs does not in accuracy correspond to our Morals); and I think it first desirable that you should know something about Marmontel himself. He was a French gentleman of the old school; not noble, nor, in French sense, even “gentilhomme;” but a peasant’s son, who made his way into Parisian society by gentleness, wit, and a dainty and candid literary power. He became one of the humblest, yet honestest, placed scholars at the court of Louis XV., and wrote pretty, yet wise, sentimental stories, in finished French, which I must render as I can in broken English; but, however rudely translated, the sayings and thoughts in them deserve your extreme attention, for in their fine, [11]tremulous way, like the blossoming heads of grass in May, they are perfect. For introduction then, you shall have, to-day, his own description of his native place, Bort, in central south France, and of the circumstances of his child-life. You must take it without further preamble—my pages running short.

“Bort, situated on the river Dordogne, between Auvergne and the province of Limoges, is a frightful place enough, seen by the traveller descending suddenly on it; lying, as it does, at the bottom of a precipice, and looking as if the storm torrents would sweep it away, or as if, some day, it must be crushed under a chain of volcanic rocks, some planted like towers on the height which commands the town, and others already overhanging, or half uprooted: but, once in the valley, and with the eye free to wander there, Bort becomes full of smiles. Above the town, on a green island which the river embraces with equal streams, there is a thicket peopled with birds, and animated also with the motion and noise of a mill. On each side of the river are orchards and fields, cultivated with laborious care. Below the village the valley opens, on one side of the river, into a broad, flat meadow, watered by springs; on the other, into sloping fields, crowned by a belt of hills whose soft slope contrasts with the opposing rocks, and is divided, farther on, by a torrent which rolls and leaps through the forest, and falls into the Dordogne in one of the most beautiful cataracts on the Continent. Near that spot is situated [12]the little farm of St. Thomas, where I used to read Virgil under the blossoming trees that surrounded our bee-hives, and where I made delicious lunches of their honey. On the other side of the town, above the mill, and on the slope to the river, was the enclosure where, on fête days, my father took me to gather grapes from the vines he had himself planted, or cherries, plums, and apples, from the trees he had grafted.

“But what in my memory is the chief charm of my native place is the impression of the affection which my family had for me, and with which my soul was penetrated in earliest infancy. If there is any goodness in my character, it is to these sweet emotions, and the perpetual happiness of loving and being loved that I believe it is owing. What a gift does Heaven bestow on us in the virtue of parents!

“I owed much also to a certain gentleness of manners which reigned then in my native town; and truly the sweet and simple life that one led there must have had a strange attraction, for nothing was more unusual than that the children of Bort should ever go away from it. In their youth they were well educated, and in the neighbouring colleges their colony distinguished itself; but they came back to their homes as a swarm of bees comes back to the hive with its spoil.

“I learned to read in a little convent where the nuns were friends of my mother. Thence I passed to the school of a priest of the town, who gratuitously, and for [13]his own pleasure, devoted himself to the instruction of children; he was the only son of a shoemaker, one of the honestest fellows in the world; and this churchman was a true model of filial piety. I can yet remember, as if I had seen it but a moment since, the air of quiet courtesy and mutual regard which the old man and his son maintained to each other; the one never losing sight of the dignity of the priesthood, nor the other of the sanctity of the paternal character.”

I interrupt my translation for a moment to ask you to notice how this finished scholar applies his words. A vulgar writer would most probably have said “the sanctity of the priesthood” and “the dignity of the paternal character.” But it is quite possible that a priest may not be a saint, yet (admitting the theory of priesthood at all) his authority and office are not, therefore, invalidated. On the other hand, a father may be entirely inferior to his son, incapable of advising him, and, if he be wise, claiming no strict authority over him. But the relation between the two is always sacred.

“The Abbé Vaissère” (that was his name), “after he had fulfilled his duty at the church, divided the rest of his time between reading, and the lessons he gave to us. In fine weather, a little walk, and sometimes for exercise a game at mall in the meadow, were his only amusements. For all society he had two friends, people of esteem in our town. They lived together in the most peaceful intimacy, seeing each other every day, and [14]every day with the same pleasure in their meeting; and for fulfilment of good fortune, they died within a very little while of each other. I have scarcely ever seen an example of so sweet and constant equality in the course of human life.

“At this school I had a comrade, who was from my infancy an object of emulation to me. His deliberate and rational bearing, his industry in study, the care he took of his books, on which I never saw a stain; his fair hair always so well combed, his dress always fresh in its simplicity, his linen always white, were to me a constantly visible example; and it is rare that a child inspires another child with such esteem as I had for him. His father was a labourer in a neighbouring village, and well known to mine. I used to walk with his son to see him in his home. How he used to receive us, the white-haired old man,—the good cream! the good brown bread that he gave us! and what happy presages did he not please himself in making for my future life, because of my respect for his old age. Twenty years afterwards, his son and I met at Paris; I recognized in him the same character of prudence and kindness which I had known in him at school, and it has been to me no slight pleasure to name one of his children at baptism.

“When I was eleven years old, just past, my master judged me fit to enter the fourth class of students; and my father consented, though unwillingly, to take me to [15]the College of Mauriac. His reluctance was wise. I must justify it by giving some account of our household.

“I was the eldest of many children; my father, a little rigid, but entirely good under his severe manner, loved his wife to idolatry; and well he might! I have never been able to understand how, with the simple education of our little convent at Bort, she had attained so much pleasantness in wit, so much elevation in heart, and a sentiment of propriety so just, pure, and subtle. My good Bishop of Limoges has often spoken to me since, at Paris, with most tender interest, of the letters that my mother wrote in recommending me to him.

“My father revered her as much as he loved; and blamed her only for her too great tenderness for me: but my grandmother loved me no less. I think I see her yet—the good little old woman! the bright nature that she had! the gentle gaiety! Economist of the house, she presided over its management, and was an example to us all of filial tenderness, for she had also her own mother and her husband’s mother to take care of. I am now dating far back, being just able to remember my great-grandmother drinking her little cup of wine at the corner of the hearth; but, during the whole of my childhood, my grandmother and her three sisters lived with us, and among all these women, and a swarm of children, my father stood alone, their support. With little means enough, all could live. Order, economy, and labour,—a little commerce, but above all things, frugality” [16](Note again the good scholar’s accuracy of language: “Economy” the right arrangement of things, “Frugality” the careful and fitting use of them)—“these maintained us all in comfort. The little garden produced vegetables enough for the need of the house; the orchard gave us fruit, and our quinces, apples, and pears, preserved in the honey of our bees, made, during the winter, for the children and old women, the most exquisite breakfasts.”

I interrupt again to explain to you, once for all, a chief principle with me in translation. Marmontel says, “for the children and good old women.” Were I quoting the French I would give his exact words, but in translating I miss the word “good,” of which I know you are not likely to see the application at the moment. You would not see why the old women should be called good, when the question is only what they had for breakfast. Marmontel means that if they had been bad old women they would have wanted gin and bitters for breakfast, instead of honey-candied quinces; but I can’t always stop to tell you Marmontel’s meaning, or other people’s, and therefore if I think it not likely to strike you, and the word weakens the sentence in the direction I want you to follow, I omit it in translating, as I do also entire sentences, here and there; but never, as aforesaid, in actual quotation.

“The flock of the fold of St. Thomas, clothed, with its wool, now the women, and now the children; my [17]aunt spun it, and spun also the hemp which made our under-dress; the children of our neighbours came to beat it with us in the evening by lamp-light, (our own walnut trees giving us the oil,) and formed a ravishing picture. The harvest of our little farm assured our subsistence; the wax and honey of our bees, of which one of my aunts took extreme care, were a revenue, with little capital. The oil of our fresh walnuts had flavour and smell, which we liked better than those of the oil-olive, and our cakes of buck-wheat, hot, with the sweet butter of Mont Dor, were for us the most inviting of feasts. By the fireside, in the evening, while we heard the pot boiling with sweet chestnuts in it, our grandmother would roast a quince under the ashes and divide it among us children. The most sober of women made us all gourmands. Thus, in a household, where nothing was ever lost, very little expense supplied all our further wants; the dead wood of the neighbouring forests was in abundance, the fresh mountain butter and most delicate cheese cost little; even wine was not dear, and my father used it soberly.”

That is as much, I suppose, as you will care for at once. Insipid enough, you think?—or perhaps, in one way, too sapid; one’s soul and affections mixed up so curiously with quince-marmalade? It is true, the French have a trick of doing that; but why not take it the other way, and say, one’s quince-marmalade mixed up with affection? We adulterate our affections [18]in England, now-a-days, with a yellower, harder, baser thing than that; and there would surely be no harm in our confectioners putting a little soul into their sugar,—if they put in nothing worse?

But as to the simplicity—or, shall we say, wateriness,—of the style, I can answer you more confidently. Milkiness would be a better word, only one does not use it of styles. This writing of Marmontel’s is different from the writing you are accustomed to, in that there is never an exaggerating phrase in it—never a needlessly strained or metaphorical word, and never a misapplied one. Nothing is said pithily, to show the author’s power, diffusely, to show his observation, nor quaintly, to show his fancy. He is not thinking of himself as an author at all; but of himself as a boy. He is not remembering his native valley as a subject for fine writing, but as a beloved real place, about which he may be garrulous, perhaps, but not rhetorical. But is it, or was it, or could it ever be, a real place, indeed?—you will ask next. Yes, real in the severest sense; with realities that are to last for ever, when this London and Manchester life of yours shall have become a horrible, and, but on evidence, incredible, romance of the past.

Real, but only partially seen; still more partially told. The rightnesses only perceived; the felicities only remembered; the landscape seen as if spring lasted always; the trees in blossom or fruitage evermore: no [19]shedding of leaf: of winter, nothing remembered but its fireside.

Yet not untrue. The landscape is indeed there, and the life, seen through glass that dims them, but not distorts; and which is only dim to Evil.

But now supply, with your own undimmed insight, and better knowledge of human nature; or invent, with imaginative malice, what evil you think necessary to make the picture true. Still—make the worst of it you will—it cannot but remain somewhat incredible to you, like the pastoral scene in a pantomime, more than a piece of history.

Well; but the pastoral scene in a pantomime itself,—tell me,—is it meant to be a bright or a gloomy part of your Christmas spectacle? Do you mean it to exhibit, by contrast, the blessedness of your own life in the streets outside; or, for one fond and foolish half-hour, to recall the “ravishing picture” of days long lost? “The sheep-fold of St. Thomas,” (you have at least, in him, an incredulous saint, and fit patron of a Republic at once holy and enlightened), the green island full of singing birds, the cascade in the forest, the vines on the steep river-shore;—the little Marmontel reading his Virgil in the shade, with murmur of bees round him in the sunshine;—the fair-haired comrade, so gentle, so reasonable, and, marvel of marvels, beloved for being exemplary! Is all this incredible to you in its good or in its evil? Those children rolling on the heaps of [20]black and slimy ground, mixed with brickbats and broken plates and bottles, in the midst of Preston or Wigan, as edified travellers behold them when the station is blocked, and the train stops anywhere outside,—the children themselves, black, and in rags evermore, and the only water near them either boiling, or gathered in unctuous pools, covered with rancid clots of scum, in the lowest holes of the earth-heaps,—why do you not paint these for pastime? Are they not what your machine gods have produced for you? The mighty iron arms are visibly there at work;—no St. Thomas can be incredulous about the existence of gods such as they,—day and night at work—omnipotent, if not resplendent. Why do you not rejoice in these; appoint a new Christmas for these, in memory of the Nativity of Boilers, and put their realms of black bliss into new Arcadias of pantomime—the harlequin, mask all over? Tell me, my practical friends.

Believe me, faithfully yours,

JOHN RUSKIN. [21]

I must in future reserve a page, at the end of these Letters, partly for any chance word of correspondence; partly to give account of what I am doing, (when it becomes worth relating,) with the interest of the St. George’s Fund.

To-day I wish only to invite the reader’s attention to the notice, which is sent out with each volume of the revised series of my works, that I mean to sell my own books at a price from which there shall be no abatement—namely, 18s. the plain volumes, and 27s. 6d. the illustrated ones; and that my publisher, Mr. G. Allen, Sunnyside, Orpington, Kent, will supply them at that price without abatement, carriage paid, to any person in town or country, on remittance of the price of the number of volumes required.

This absolute refusal of credit or abatement is only the carrying out of a part of my general method of political economy; and I adopt this system of sale, because I think authors ought not to be too proud to sell their own books, any more than painters to sell their own pictures.

I intend the retail dealer to charge twenty shillings for the plain volumes, and thirty shillings for the others. If he declines offering them for that percentage, it is for the public to judge how much he gets usually. [1]

1 I quote from the ‘Pall Mall Gazette’ of January 16th. In the more elaborate review given in the ‘Fortnightly,’ I am glad to see that Professor Caird is beginning to perceive the necessity of defining the word “useful;” and, though greatly puzzled, is making way towards a definition: but would it not be wiser to abstain from exhibiting himself in his state of puzzlement to the public? ↑

2 Every man as good as his neighbour! you extremely sagacious English persons; and forthwith you establish competitive examination, which drives your boys into idiotcy, before you will give them a bit of bread to make their young muscles of! Every man as good as his neighbour! and when I told you, seven years ago, that at least you should give every man his penny of wages, whether he was good or not, so only that he gave you the best that was in him, what did you answer to me? ↑

Denmark Hill,

1st March, 1872.

My Friends,

The Tory gentleman whose character I have to sketch for you, in due counterbalance of that story of republican justice in California, was, as I told you, the friend of Friedrich II. of Germany, another great Friedrich preceding the Prussian one by some centuries, and living quite as hard a life of it. But before I can explain to you anything either about him, or his friend, I must develop the statement made above (XI. 6), of the complex modes of injustice respecting the means of maintenance, which have hitherto held in all ages among the three great classes of soldiers, clergy, and peasants. I mean, by ‘peasants’ the producers of food, out of land or water; by ‘clergy,’ men who live by teaching or exhibition of behaviour; and by ‘soldiers,’ those who live by fighting, [2]either by robbing wise peasants, or getting themselves paid by foolish ones. Into these three classes the world’s multitudes are essentially hitherto divided. The legitimate merchant of course exists, and can exist, only on the small percentage of pay obtainable for the transfer of goods; and the manufacturer and artist are, in healthy society, developed states of the peasant. The morbid power of manufacture and commerce in our own age is an accidental condition of national decrepitude; the injustices connected with it are mainly those of the gambling-house, and quite unworthy of analytical inquiry; but the unjust relations of the soldier, clergyman, and peasant have hitherto been constant in all great nations;—they are full of mystery and beauty in their iniquity; they require the most subtle, and deserve the most reverent, analysis.

The first root of distinction between the soldier and peasant is in barrenness and fruitfulness of possessed ground; the inhabitant of sands and rocks “redeeming his share” (see speech of Roderick in the ‘Lady of the Lake’) from the inhabitant of corn-bearing ground. The second root of it is delight in athletic exercise, resulting in beauty of person and perfectness of race, and causing men to be content, or even triumphant, in accepting continual risk of death, if by such risk they can escape the injury of servile toil.

Again, the first root of distinction between clergyman and peasant is the greater intelligence, which instinctively [3]desires both to learn and teach, and is content to accept the smallest maintenance, if it may remain so occupied. (Look back to Marmontel’s account of his tutor.)

The second root of distinction is that which gives rise to the word ‘clergy,’ properly signifying persons chosen by lot, or in a manner elect, for the practice and exhibition of good behaviour; the visionary or passionate anchorite being content to beg his bread, so only that he may have leave by undisturbed prayer or meditation, to bring himself into closer union with the spiritual world; and the peasant being always content to feed him, on condition of his becoming venerable in that higher state, and, as a peculiarly blessed person, a communicator of blessing.

Now, both these classes of men remain noble, as long as they are content with daily bread, if they may be allowed to live in their own way; but the moment the one of them uses his strength, and the other his sanctity, to get riches with, or pride of elevation over other men, both of them become tyrants, and capable of any degree of evil. Of the clerk’s relation to the peasant, I will only tell you, now, that, as you learn more of the history of Germany and Italy in the Middle Ages, and, indeed, almost to this day, you will find the soldiers of Germany are always trying to get mastery over the body of Italy, and the clerks of Italy are always trying to get mastery over [4]the mind of Germany;—this main struggle between Emperor and Pope, as the respective heads of the two parties, absorbing in its vortex, or attracting to its standards, all the minor disorders and dignities of war; and quartering itself in a quaintly heraldic fashion with the methods of encroachment on the peasant, separately invented by baron and priest.

The relation of the baron to the peasant, however, is all that I can touch upon to-day; and first, note that this word ‘baron’ is the purest English you can use to denote the soldier, soldato, or ‘fighter, hired with pence, or soldi,’ as such. Originally it meant the servant of a soldier, or, as a Roman clerk of Nero’s time1 tells us, (the literary antipathy thus early developing itself in its future nest,) “the extreme fool, who is a fool’s servant;” but soon it came to be associated with a Greek word meaning ‘heavy;’ and so got to signify heavy-handed, or heavy-armed, or generally prevailing in manhood. For some time it was used to signify the authority of a husband; a woman called herself her husband’s2 ‘ancilla,’ (handmaid), and him her ‘baron.’ Finally the word got settled in the meaning of a strong fighter receiving regular pay. “Mercenaries are persons who serve for a regularly received pay; the same are called ‘Barones’ from [5]the Greek, because they are strong in labours.” This is the definition given by an excellent clerk of the seventh century, Isidore, Bishop of Seville, and I wish you to recollect it, because it perfectly unites the economical idea of a Baron, as a person paid for fighting, with the physical idea of one, as prevailing in battle by weight; not without some attached idea of slight stupidity;—the notion holding so distinctly even to this day that Mr. Matthew Arnold thinks the entire class aptly describable under the term ‘barbarians.’

At all events, the word is the best general one for the dominant rank of the Middle Ages, as distinguished from the pacific peasant, and so delighting in battle that one of the most courteous barons of the fourteenth century tells a young knight who comes to him for general advice, that the moment war fails in any country, he must go into another.

“Et se la guerre est faillie,

Départie

Fay tóst de cellui païs;

N’arresté quoy que nul die.”

“And if the war has ended,

Departure

Make quickly from that country;

Do not stop, whatever anybody says to you.”3

But long before this class distinction was clearly established, the more radical one between pacific and warrior nations had shown itself cruelly in the history of Europe. [6]

You will find it greatly useful to fix in your minds these following elementary ideas of that history:—

The Roman Empire was already in decline at the birth of Christ. It was ended five hundred years afterwards. The wrecks of its civilization, mingled with the broken fury of the tribes which had destroyed it, were then gradually softened and purged by Christianity; and hammered into shape by three great warrior nations, on the north, south, and west, worshippers of the storms, of the sun, and of fate. Three Christian kings, Henry the Fowler in Germany, Charlemagne in France, and Alfred in England, typically represent the justice of humanity, gradually forming the feudal system out of the ruined elements of Roman luxury and law, under the disciplining torment inflicted by the mountaineers of Scandinavia, India, and Arabia.

This forging process takes another five hundred years. Christian feudalism may be considered as definitely organized at the end of the tenth century, and its political strength established, having for the most part absorbed the soldiers of the north, and soon to be aggressive on those of Mount Imaus and Mount Sinai. It lasts another five hundred years, and then our own epoch, that of atheistic liberalism, begins, practically necessitated,—the liberalism by the two discoveries of gunpowder and printing,—and the atheism by the unfortunate persistence of the clerks in teaching children what they cannot understand, and employing young [7]consecrated persons to assert in pulpits what they do not know.

That is enough generalization for you to-day. I want now to fix your thoughts on one small point in all this;—the effect of the discovery of gunpowder in promoting liberalism.

Its first operation was to destroy the power of the baron, by rendering it impossible for him to hold his castle, with a few men, against a mob. The fall of the Bastile is a typical fact in history of this kind; but, of course long previously, castellated architecture had been felt to be useless. Much other building of a noble kind vanishes together with it; nor less (which is a much greater loss than the building,) the baronial habit of living in the country.

Next to his castle, the baron’s armour becomes useless to him; and all the noble habits of life vanish which depend on the wearing of a distinctive dress, involving the constant exercise of accurately disciplined strength, and the public assertion of an exclusive occupation in life, involving exposure to danger.

Next, the baron’s sword and spear become useless to him; and encounter, no longer the determination of who is best man, but of who is best marksman, which is a very different question indeed.

Lastly, the baron being no more able to maintain his authority by force, seeks to keep it by form; he reduces his own subordinates to a fine machinery, and obtains the [8]command of it by purchase or intrigue. The necessity of distinction of character is in war so absolute, and the tests of it are so many, that, in spite of every abuse, good officers get sometimes the command of squadrons or of ships; and one good officer in a hundred is enough to save the honour of an army, and the credit of a system: but generally speaking, our officers at this day do not know their business; and the result is—that, paying thirty millions a year for our army, we are informed by Mr. Grant Duff that the army we have bought is of no use, and we must pay still more money to produce any effect upon foreign affairs. So, you see, this is the actual state of things,—and it is the perfection of liberalism,—that first we cannot buy a Raphael for five-and-twenty pounds, because we have to pay five hundred for a pocket pistol; and next, we are coolly told that the pocket pistol won’t go off, and that we must still pay foreign constables to keep the peace.

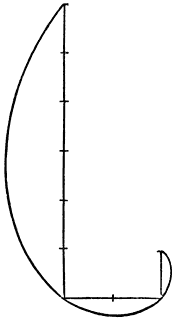

In old times, under the pure baronial power, things used, as I told you, to be differently managed by us. We were, all of us, in some sense barons; and paid ourselves for fighting. We had no pocket pistols, nor Woolwich Infants—nothing but bows and spears, good horses, (I hear, after two-thirds of our existing barons have ruined their youth in horseracing, and a good many of them their fortunes also, we are now in irremediable want of horses for our cavalry,) and bright armour. [9]Its brightness, observe, was an essential matter with us. Last autumn I saw, even in modern England, something bright; low sunshine at six o’clock of an October morning, glancing down a long bank of fern covered with hoar-frost, in Yewdale, at the head of Coniston Water. I noted it as more beautiful than anything I had ever seen, to my remembrance, in gladness and infinitude of light. Now, Scott uses this very image to describe the look of the chain-mail of a soldier in one of these free4 companies;—Le Balafré, Quentin Durward’s uncle:—“The archer’s gorget, arm-pieces, and gauntlets were of the finest steel, curiously inlaid with silver, and his hauberk, or shirt of mail, was as clear and bright as the frost-work of a winter morning upon fern or briar.” And Sir John Hawkwood’s men, of whose proceedings in Italy I have now to give you some account, were named throughout Italy, as I told you in my first letter, the White Company of English,—‘Societas alba Anglicorum,’ or generally, the Great White Company, merely from the splendour of their arms. They crossed the Alps in 1361, and immediately caused a curious change in the Italian language. Azario lays great stress on their tall spears [10]with a very long iron point at the extremity; this formidable weapon being for the most part wielded by two, and sometimes moreover by three individuals, being so heavy and huge, that whatever it came in contact with was pierced through and through. He says, that5 “at their backs the mounted bowmen carried their bows; whilst those used by the infantry archers were so enormous that the long arrows discharged from them were shot with one end of the bow resting on the ground instead of being drawn in the air.”

Of the English bow you have probably heard before, though I shall have, both of it, and the much inferior Greek bow made of two goats’ horns, to tell you some things that may not have come in your way; but the change these English caused in the Italian language, and afterwards generally in that of chivalry, was by their use of the spear; for “Filippo Villani tells us that, whereas, until the English company crossed the Alps, his countrymen numbered their military forces by ‘helmets’ and colour companies, (bandiere); thenceforth armies were reckoned by the spear, a weapon which, when handled by the White Company, proved no less tremendous than the English bayonet of modern times.”

It is worth noting as one of the tricks of the third Fors—the giver of names as well as fortunes—that the name of the chief poet of passionate Italy should have [11]been ‘the bearer of the wing,’ and that of the chief poet of practical England, the bearer or shaker of the spear. Noteworthy also that Shakespeare himself gives a name to his type of the false soldier from the pistol; but, in the future, doubtless we shall have a hero of culminating soldierly courage named from the torpedo, and a poet of the commercial period, singing the wars directed by Mr. Grant Duff, named Shake-purse.

The White Company when they crossed the Alps were under a German captain. (Some years before, an entirely German troop was prettily defeated by the Apennine peasants.) Sir John Hawkwood did not take the command until 1364, when the Pisans hired the company, five thousand strong, at the rate of a hundred and fifty thousand golden florins for six months. I think about fifty thousand pounds of our money a month, or ten pounds a man—Sir John himself being then described as a “great general,” an Englishman of a vulpine nature, “and astute in their fashion.” This English fashion of astuteness means, I am happy to say, that Sir John saw far, planned deeply, and was cunning in military stratagem; but would neither poison his enemies nor sell his friends—the two words of course being always understood as for the time being;—for, from this year 1364 for thirty years onward, he leads his gradually more and more powerful soldier’s life, fighting first for one town and then for another; here for bishops, and there for barons, but mainly for those merchants of Florence, [12]from whom that narrow street in your city is named Lombard Street, and interfering thus so decidedly with foreign affairs, that, at the end of the thirty years, when he put off his armour, and had lain resting for a little while in Florence Cathedral, King Richard the Second begged his body from the Florentines, and laid it in his own land; the Florentines granting it in the terms of this following letter:—

“To the King of England.

“Most serene and invincible Sovereign, most dread Lord, and our very especial Benefactor—

“Our devotion can deny nothing to your Highness’ Eminence: there is nothing in our power which we would not strive by all means to accomplish, should it prove grateful to you.

“Wherefore, although we should consider it glorious for us and our people to possess the dust and ashes of the late valiant knight, nay, most renowned captain, Sir John Hawkwood, who fought most gloriously for us, as the commander of our armies, and whom at the public expense we caused to be entombed in the Cathedral Church of our city; yet, notwithstanding, according to the form of the demand, that his remains may be taken back to his country, we freely concede the permission, lest it be said that your sublimity asked anything in vain, or fruitlessly, of our reverential humility.

“We, however, with due deference, and all possible [13]earnestness, recommend to your Highness’ graciousness, the son and posterity of said Sir John, who acquired no mean repute, and glory for the English name in Italy, as also our merchants and citizens.”

It chanced by the appointment of the third Fors,6 to which, you know, I am bound in these letters uncomplainingly to submit, that, just as I had looked out this letter for you, given at Florence in the year 1396, I found in an old bookshop two gazettes, nearly three hundred years later, namely, Number 20 of the ‘Mercurius Publicus,’ and Number 50 of the ‘Parliamentary Intelligencer,’ the latter comprising the same “foraign intelligence, with the affairs now in agitation in England, Scotland, and Ireland, for information of the people. Publish’d by order, from Monday, December 3rd, to Monday, December 10th, 1660.” This little gazette informs us in its first advertisement, that in London, November 30th, 1660, was lost, in or about this city, a small paper book of accounts and receipts, with a red leather cover, with two clasps on it; and that anybody that can give intelligence of it to the city crier at Bread Street end in Cheapside, “shall have five shillings for their pains, and more if they desire it.” And its last paragraph is as follows:—“On Saturday (December 8), the Most Honourable House of [14]Peers concurred with the Commons in the order for the digging up the carkasses of Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, John Bradshaw, and Thomas Pride, and carrying them on an Hurdle to Tyburn, where they are to be first hang’d up in their Coffins, and then buried under the Gallows.”

The ‘Public Mercury’ is of date Thursday, June 14th, to Thursday, June 21st, 1660, and contains a report of the proceedings at the House of Commons, on Saturday, the 16th, of which the first sentence is:—

“Resolved,—That his Majesty be humbly moved to call in Milton’s two books, and John Goodwin’s, and order them to be burnt by the common hangman.”

By the final appointment of the third Fors, I chanced just after finding these gazettes, to come upon the following passage in my ‘Daily Telegraph’:—

“Every head was uncovered, and although among those who were farthest off there was a pressing forward and a straining to catch sight of the coffin, there was nothing unseemly or rude. The Catafalque was received at the top of the stairs by Col. Braine and other officers of the 9th, and placed in the centre of the vestibule on a rich velvet pall on which rested crowns, crosses, and other devices, composed of tuberoses and camellias, while beautiful lilies were scattered over the corpse, which was clothed in full regimentals, the cap and sword resting on the body. The face, with the exception [15]of its pallor, was unchanged, and no one, unless knowing the circumstances, would have believed that Fiske had died a violent death. The body was contained in a handsome rosewood casket, with gold-plated handles, and a splendid plate bearing the inscription, ‘James Fiske, jun., died January 7th, 1872, in the 37th year of his age.’”

In the foregoing passages, you see, there is authentic account given you of the various honours rendered by the enlightened public of the fourteenth, seventeenth, and nineteenth centuries to the hero of their day or hour; the persons thus reverenced in their burial, or unburial, being all, by profession, soldiers; and holding rank in that profession, very properly describable by the pretty modern English word ‘Colonel’—leader, that is to say, of a Coronel, Coronella, or daisy-like circlet of men; as in the last case of the three before us, of the Tammany ‘Ring.’

You are to observe, however, that the first of the three, Colonel Sir John Hawkwood, is a soldier both in heart and deed, every inch of him; and that the second, Colonel Oliver Cromwell, was a soldier in deed, but not in heart; being by natural disposition and temper fitted rather for a Huntingdonshire farmer, and not at all caring to make any money by his military business; and finally, that Colonel James Fiske, jun., was a soldier in heart, to the extent of being willing to receive any quantity [16]of soldi from any paymaster, but no more a soldier in deed than you are yourselves, when you go piping and drumming past my gate at Denmark Hill (I should rather say—banging, than drumming, for I observe you hit equally hard and straightforward to every tune; so that from a distance it sounds just like beating carpets), under the impression that you are defending your country as well as amusing yourselves.

Of the various honours, deserved or undeserved, done by enlightened public opinion to these three soldiers, I leave you to consider till next month, merely adding, to put you more entirely in command of the facts, that Sir John Hawkwood, (Acuto, the Italians called him, by happy adaptation of syllables,) whose entire subsistence was one of systematic military robbery, had, when he was first buried, the honour, rarely granted even to the citizens of Florence, of having his coffin laid on the font of the House of his name-saint, St. John Baptist—that same font which Dante was accused of having impiously broken to save a child from drowning, in “mio bel San Giovanni.” I am soon going to Florence myself to draw this beautiful San Giovanni for the beginning of my lectures on Architecture, at Oxford; and you shall have a print of the best sketch I can make, to assist your meditations on the honours of soldiership, and efficacy of baptism. Meantime, let me ask you to read an account of one funeral more, and to meditate also on that. It is given in the most exquisite and finished [17]piece which I know of English Prose literature in the eighteenth century; and, however often you may have seen it already, I beg of you to read it now, both in connection with the funeral ceremonies described hitherto, and for the sake of its educational effect on your own taste in writing:—

“We last night received a piece of ill news at our club, which very sensibly afflicted every one of us. I question not but my readers themselves will be troubled at the hearing of it. To keep them no longer in suspense, Sir Roger de Coverley is dead. He departed this life at his house in the country, after a few weeks’ sickness. Sir Andrew Freeport has a letter from one of his correspondents in those parts, that informs him the old man caught a cold at the county-sessions, as he was very warmly promoting an address of his own penning, in which he succeeded according to his wishes. But this particular comes from a Whig justice of peace, who was always Sir Roger’s enemy and antagonist. I have letters both from the chaplain and Captain Sentry, which mention nothing of it, but are filled with many particulars to the honour of the good old man. I have likewise a letter from the butler, who took so much care of me last summer when I was at the knight’s house. As my friend the butler mentions, in the simplicity of his heart, several circumstances the others have passed over in silence, I shall give my reader a copy of his letter, without any alteration or diminution. [18]