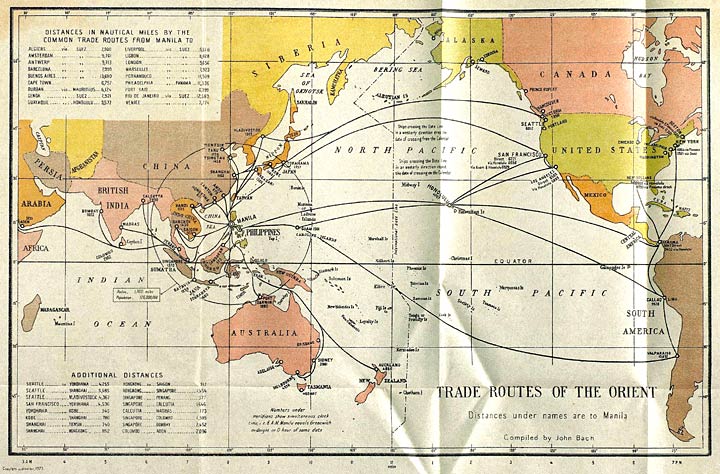

The Philippine Archipelago is a compact group of islands. The distances between each

island require only a few hours of sailing. They therefore have been said to possess

strategic unity. From the northernmost port, Aparri, to the southernmost Zamboanga,

the total distance is 895 miles. It takes only 36 hours from Manila to Aparri and

about 72 from Manila to Zamboanga. With faster boats, the time required will be much

less.

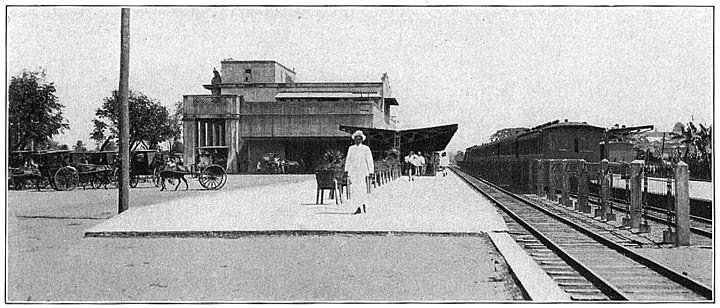

In each island the provinces and the important towns are easily accessible. They are

connected by good roads. In the bigger islands the Manila Railroad operates lines,

such as in Luzon, Cebu, and Iloilo.

The trip through the provinces should be taken whenever possible. Barring the usual

discomforts of a tropical clime, there are delights galore for everyone, even for

the hardy sportsman—pristine forests, crystal streams, splashing falls. The panoramas

that unfold as the traveler motors from province to province or cruises about from

island to island present a continuous series of scenic pictures of infinite variety.

In other lands nature and man have combined their efforts in forming recreation spots

of compelling charm. In the Philippines it is only nature that has done the work.

The services of a guide should in all cases be secured in order to expedite the visits.

Applications for guides should be made to the Director of the Bureau of Commerce and

Industry.

LAGUNA PROVINCE.—The Province of Laguna is situated on a narrow plain which lies to the east, south,

and southeast of Laguna Lake, commonly known as Laguna de Bay. It is a very fertile

province and has a very pleasant [70]climate, the usual temperature being several degrees cooler than Manila. It produces

coconuts, rice, sugar-cane, abaca, corn and a great variety of fruits and vegetables.

In industrial enterprises the province is very progressive. Some of the largest kind

of hemp cables are made in the rope factory of Santa Cruz. Buntal hats and pandan

mats are made in Majayjay and Luisiana, pandan hats in Cavisti, Sabutan hats in Mavitac,

rattan chairs in Paquil and Los Baños, wooden slippers in Biñan and Calamba, and abacá

slippers in Lilio. Furniture is also made in Paete, soap in Santa Cruz, crude pottery

in Lumban, better grade of glazed pottery in San Pedro Tunasan, coconut wine in the

upper towns, and embroidery in Lumbang. Mineral waters are bottled in Los Baños, Pagsanjan,

and Magdalena. A steam saw mill is located in Santa Maria. In Los Baños is a stone

quarry that supplies crushed stone for the Provinces of Bulacan, Rizal, Cavite, Batangas,

and Tayabas.

The province, besides having a rich soil, has an abundance of water supply. The Laguna

de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, permits of easy and cheap transportation.

Fifteen of the 28 municipalities are reached by water and a line of steam launches

provides a daily service between the lake and the city of Manila. The lake abounds

in fish. The swamps along its eastern shores are overgrown with pandan groves. The

bay is covered during the rainy season with the pink-flowered lotus plant. Along the

low shores are veritable hunting grounds which abound in snipe and wild ducks.

The province also abounds in picturesque sceneries, in the San Pablo Valley there

are nine beautifully-set crater lakes. Banahaw, a mountain having an elevation of

7,382 feet, is covered with vegetation of all kinds. In the crater of San Cristobal

which has an elevation of about 5,000 feet there is a beautiful fresh water lake.

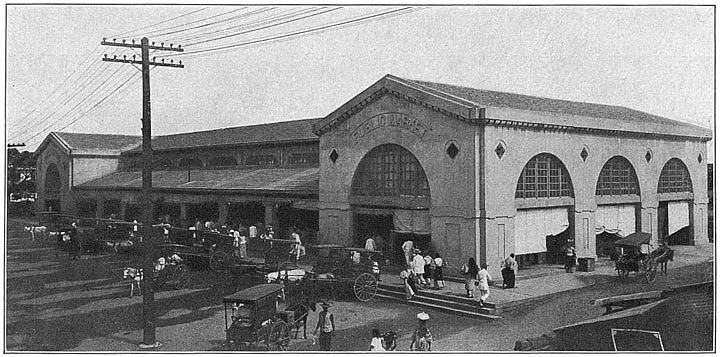

San Pablo is a progressive town well worth visiting. It is one of the largest towns

in the Islands and is up-to-date in every respect. A large park overlooks a lake of

rare beauty with the majestic San Cristobal mountains in the [71]background. A long flight of white stone steps leads from the cliff above down to

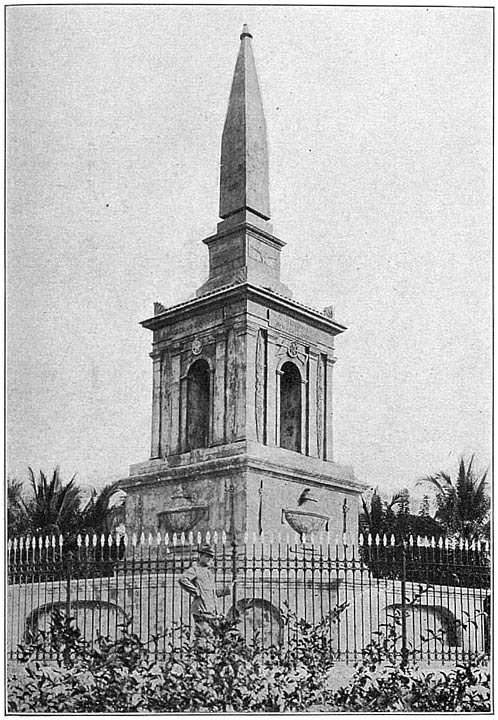

the lake shore, and the park is a favorite picnic ground. The veteran’s monument at

this point always attracts much attention. The town has numerous private residences

of striking architectural design.

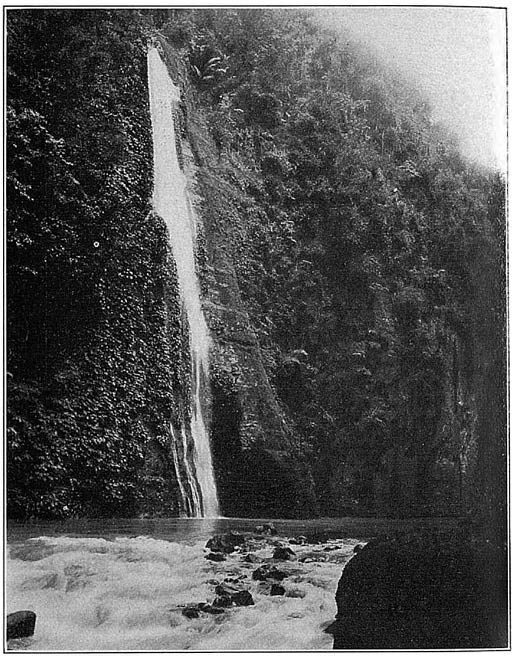

Pagsanjan Falls

One of the prettiest and wildest spots lies within easy reach of Manila—Pagsanjan

Falls. Pagsanjan, the town, in itself worth seeing for its beautiful residences and

the surrounding forests, can be reached in three and one-half hours by train or automobile

through a lovely coconut country. There are good hotel accommodations with clean beds

and food. Everything is done for the tourist; arrangements are made for boats and

guides, and launches are provided.

From the hotel you walk a short distance to a long row of bancas, prow on shore, and

a noisy throng of men clamoring for the favor of your patronage; but you have probably

chosen men at the hotel and are conducted to certain boats by your guide. In the center

of your boat is the seat, a split bamboo chair with reclining back and bottom of bamboo

splints. The two boatmen take their places at the ends of the boat and push off into

the small stream for a few hundred yards to Pagsanjan River.

The boat is paddled up the river past large rafts of coconuts, by great trees dipping

their leaves into the water. Along the shores are parties of laughing people—some

bathing and some washing clothes. Now there are long reaches of quiet water, clear

and deep; then banks begin to rise above you; there is a swirl here, a ripple there,

and a swish below the gunwales. You are drawing toward the rapids. The boatmen get

put into the water and pull and tug and shove; the water sucks viciously. The boat

enters the gorge and its shadows. The river becomes silent stretches of black water,

and the air is cold. Above, for hundreds of feet, tower the great cliffs of Pagsanjan

to which cling vines, desperate trees, and dripping shrubs. On all sides are falls

breaking upon the rocks and filling the canyon with a pleasant murmur; then more rapids

and sweeps of fierce [72]water. Great boulders have fallen into the river. Unable to paddle against the current

or to wade, the men now fight painfully forward by clinging to vines, the rocks, anything.

Then out of the boat again, lifting it and you bodily up steps of pouring water, around

corners, shooting across a quiet pool into a fury of cascading foam. At times you

scramble out of the boat and detour a little over intervening rocks, while the fight

with the river goes on. For two hours the journey continues, until you come to the

end—a large pool—above you, Pagsanjan Falls, the largest waterfall in the Islands,

around, the insurmountable cliffs fringed above by shining palms. Monkeys and iguanas

scurry over the slippery bluffs complaining at intrusion.

You should go prepared to rough it. Only a bathing suit is worn in the boats and except

at times of low water, kodaks had better be left at the hotel, for rapids lap over

the side. Indeed many have been the spills in the swift water. But there is no danger,

and a wetting is of no consequence. The whole trip need cost no more than twenty pesos

nor occupy more than a day and a half.

It is a wonderful trip for those who enjoy the wilds. The gorge is considered one

of the beauty spots of the world.

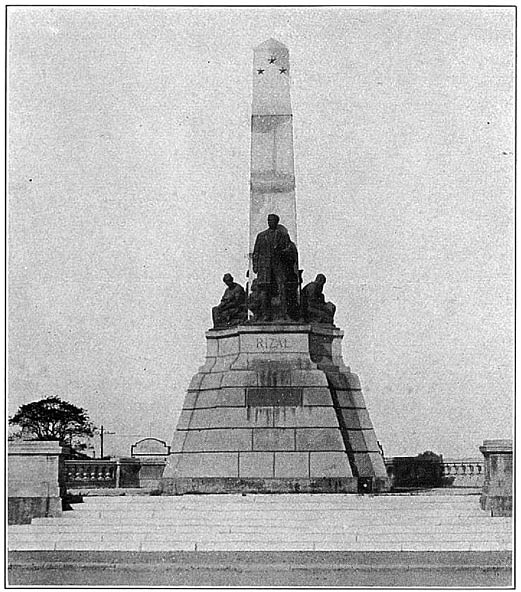

RIZAL PROVINCE.—To the north of Laguna de Bay, is Rizal Province, named after the national hero of

the Filipinos. Pasig, the capital is an important commercial town. It is located on

the Pasig River, a stream which is navigable thruout the year. Malabon, noted for

her fisheries and fish ponds, furnishes the City of Manila with choice fish to the

value of hundreds of thousands of pesos a year. A flourishing poultry industry may

be seen at Pateros. Parañaque is noted for its embroideries while in Mariquina the

chief industry is the making of shoes and slippers. Along the borders of the Pasig

River much grass is cultivated to furnish the Manila market with green fodder for

horses and carabaos.

In this province are the towns of Pasig, San Juan del Monte, and Caloocan where the

first blood of the Philippine [73]Revolution against Spain was shed. Here also is to be found the historic spot of Balintawak

where Andres Bonifacio and his followers sounded the well-remembered “Cry of Balintawak,”

the call for the outbreak of the Revolution.

Antipolo

Antipolo has the shrine of Our Lady of Peace and Prosperous Voyages. It is a town about half

an hour’s ride from Manila. It is built on a mountainous section of the province of

Rizal. The road is rather steep and the scenery quite wild and impressive.

The image of the Virgin, commonly known as the “Virgin of Antipolo,” was originally

brought from Mexico by the Spaniards to insure the safety of the galleons from the

anger of the sea, and from the attacks of the pirates who used to lie in wait in the

San Bernardino Strait and Verde Island Passage.

Shrine

The shrine is the most famous of all Philippine shrines. To it thousands of devout

Filipinos journey annually to pay their respects. The Virgin is dressed in a robe

that falls in a cone stiff with gold and other jewels. It is estimated that the value

of her decoration is as high as ₱1,000,000.

The true history of the image is interesting, but still more remarkable is the crust

of legend with which the facts have become overlaid. It was actually brought to the

Islands in 1626 by Juan Niño de Tabora, who had just been appointed Governor-General,

and in 1672 it was removed to its present home. According to the legends, the Virgin

crossed the Pacific eight or nine times, in addition to the original voyage, and,

on each one, calmed a tempest. On other occasions she is said to have descended and

appeared among the branches of the antipolo or bread-fruit tree (whence the name of

the present church), to have survived the roaring fire in which the Chinese rebels

cast her in 1639, and to have given the Spaniards a complete victory over twelve Dutch

warships off Mariveles!

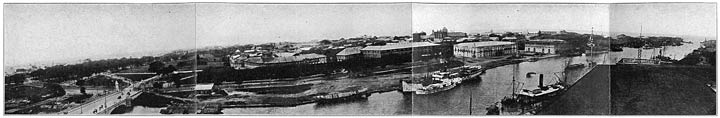

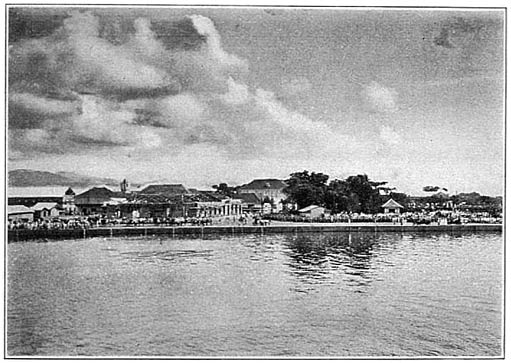

CAVITE PROVINCE.—This province is in the southwestern part of Luzon lying along the shore of Manila

Bay. It has [74]a fine harbor in the city of Cavite, actually the site of the United States Naval

Station.

The most important agricultural products are rice, hemp, sugar, copra, cacao, coffee,

corn, and coconuts.

The city of Cavite, the capital, noted for its dock-yards is just across the bay from

Manila. It is an old town of historic interest. It was there that the ships used in

the Manila-Acapulco trade and in the expeditions against the Mohammedan pirates in

the south were fitted out. In 1647 a Dutch squadron suddenly made its appearance off

the coast of the city and bombarded the fort. It is said that the Dutch fired more

than 2,000 cannon balls at the place, but in the end, however, were forced to withdraw.

In 1872, a military mutiny led by Lamadrid took place in Cavite. This mutiny though

insignificant in itself had important political results. The government made it an

excuse for the execution of three leading native priests, Dr. Jose Burgos and Fathers

Gomez and Zamora, and for the exile of many Filipino leaders of the liberal movement

of 1869–1871.

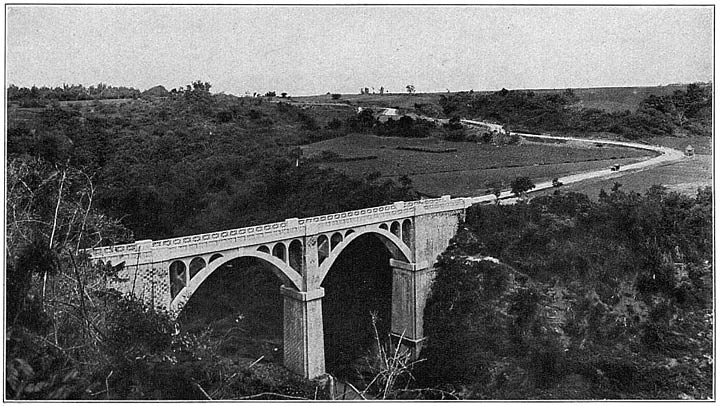

Zapote Bridge

From the beginning to the very end of the Revolution, Cavite Province was the center

of military operations. Zapote bridge, for example, was more than once the scene of

hard fighting. Practically every town in the province was at one time or another fought

over. Many of the leaders of the Revolution, like Emilio Aguinaldo, who was President

of the Philippine Republic, his cousin Baldomero, Noriel, Trias, and others are sons

of Cavite. Moreover, when the Revolutionary Government was established, Bacoor was

really the first capital.

Radio Station

The city of Cavite is the United States’ Navy base and radio station in the Philippine

Islands. The arsenal as well as the modern wireless station in the extreme end of

the peninsula should not be missed. The city is about an hour’s ride by automobile

passing through the towns of Parañaque, Las Piñas, Kawit, Noveleta, and San Roque.

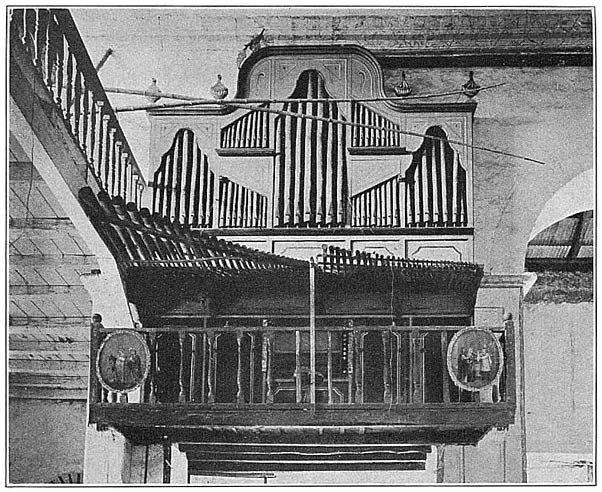

In the church at Las Piñas [75]may be seen the famous bamboo organ, old and quaint, yet still serviceable. It was

made by a priest exclusively from the native bamboo tree. Cavite can also be reached

by water, there being small boats plying between the city and Manila at regular intervals.

Kawit

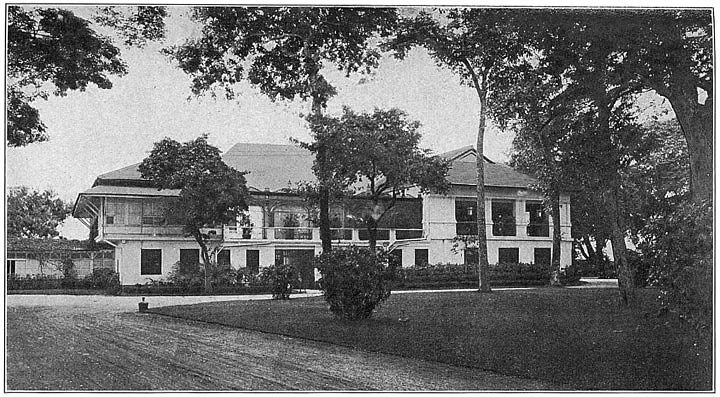

Kawit or Cavite Viejo is the town of General Emilio Aguinaldo. He has his home there, which

is noted for its historic interest. It is preserved as it was during revolutionary

days. Visitors can still see the desk used by the General during the revolution as

well as the holes made by a cannon ball from Admiral Dewey’s flagship “The Olimpia.”

BATANGAS PROVINCE.—Batangas Province is immediately south of Cavite Province. It has an irregular coastline

and has many important ports, such as Nasugbu, Calatagan, Balayan, Calaca, Lemeri,

Taal, San Luis, Batangas, Lobo, and San Juan.

At Laiya on the coast between San Juan and Lobo are the famous Lobo submarine gardens.

During fair weather the water here is as clear as crystal and the submarine growth

may be seen in all its varied colors.

The valleys and slopes of the province are extremely fertile because of the disintegrated

volcanic rock that is carried down from the mountains by the river. Sugar, hemp, citrus

fruits, coconut, corn, mangoes, and other fruits and vegetables are grown in abundance.

The province is especially noted for its delicious oranges, grown in Tanawan and Santo

Tomas. Great herds of horses famous throughout the archipelago as well as carabaos

and cattle are raised on the mountain slopes. Bawan and Lemeri are famous for the

fine jusi and piña cloths manufactured there and for the knotted abaca that is sent

to Japan for the manufacture of hats.

Historical Incidents

Throughout the 17th century the coast towns of Batangas suffered greatly from Moro

attacks. Stone forts were erected at various points along the coast—in Lemeri, Taal,

Bawan, and Batangas—but still the Moros came. In 1754 [76]as many as 38 Moro vessels appeared off the coast. In 1763 the northern part of the

province was visited by the British in search of the treasure of the galleon “Philippine.”

The expedition failed to find the treasure but went as far as Lipa and plundered the

town. Batangas was one of the first provinces to start the revolution of 1896. Two

of the great leaders of the period were sons of the province, namely, the great lawyer

and statesman, Apolinario Mabini, and Miguel Malvar, the famous general.

Attractions

Among the attractions are the old picturesque buildings of Lipa and Taal, the San

Juan sulphur springs, the Bawan hot springs, and the Rosario fresh water spring. There

are also several caves and grottos. The two largest are found in the slopes of Mount

Pulan, Suya, and Kamantigue of San Juan. One of the caves has an opening of 40 meters

in circumference. Issuing therefrom is an underground river which empties into Lake

Taal. Along its course are extensive galleries and chambers lined with fantastically

shaped stalactites and stalagmites. At the approach of an eruption of the Taal Volcano

nearby, the cave emits a weird sound, audible at great distances.

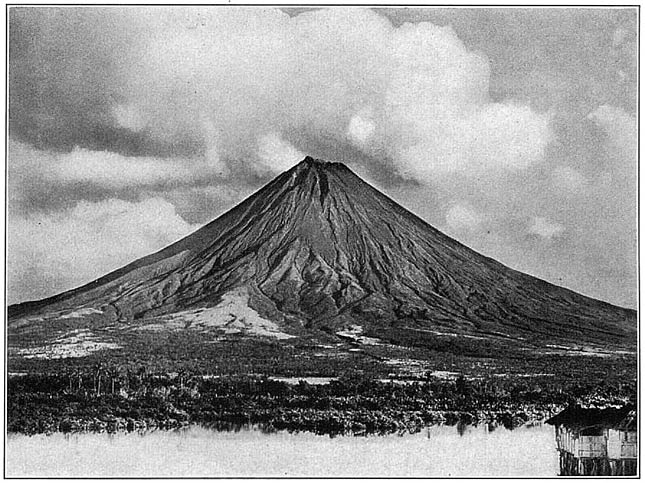

Taal Volcano

Taal Volcano is the great scenic asset of the province. Almost at the doors of Manila it is easily

reached with practically none of the discomfort which a trip to nature’s wild spots

usually involves. The volcano is commonly known as the “cloud maker” and “the terrible.”

How long this volcano has been emitting sulphurous smoke is not known; all that is

known is that back in the geologic past, volcanic outbursts of enormous magnitude

disturbed the regions about it. In the 18th century the volcano erupted several times,

and ruined many towns in the neighborhood. The last and perhaps the worst eruption

occurred in January, 1911.

Then, after a long interval, old Taal, in a paroxysm of volcanic activity, showed

that he was still lusty and capable of making a huge disturbance. In addition to the

steam [77]which had been coming from the crater more or less continuously, the volcano began

throwing out mud. This activity increased, and culminated in a great explosion at

about half past 2 on the morning of January 30th. The hot water, mud, and ashes completely

devastated about 90 square miles of country; while some mud and fine ashes fell over

an area of more than 800 square miles. Many villages were destroyed and the official

estimate of the dead was 1,335. The spasm of activity died away until the volcano

again assumed its normal state about February 8th. Since then it has been very quiet,

though a small mud geyser has started up along the old fault line which extends from

Taal to the coast. This is located on the beach at the village of Sinisian.

Before the eruption the floor of the crater stood about five feet above the level

of Lake Bombon. In it were four prominent features: Two small lakes of hot water,

one green, the other more or less red; near the center a gas vent five or six feet

in diameter, from which the hot gases roared as from a blast furnace; and just a little

distance away a triangular obelisk of hard volcanic rock. During the eruption all

of the material in the bottom of this crater, to a depth of about 230 feet, was heaved

up and spread broadcast over the country. Later on, this hole filled up with water,

which seeped in from the lake almost up to the level of the old floor, or about that

of the lake itself. There is now one large body of steaming water in place of the

former features, but the old obelisk still stands defiantly in its place.

The volcano consists of an active crater near the center of a low island not over

5½ miles in its longest diameter. The island is situated at the center of Taal Lake

(Bombon) which is about 17 miles long and 10½ miles wide. The lake is 10 meters deep

and is 2.5 meters above sea level.

A small launch carries those who would look down into the crater across the lake to

the island from which the volcano rises. The volcano is about a thousand feet in height

and is fairly easy to climb.

[78]

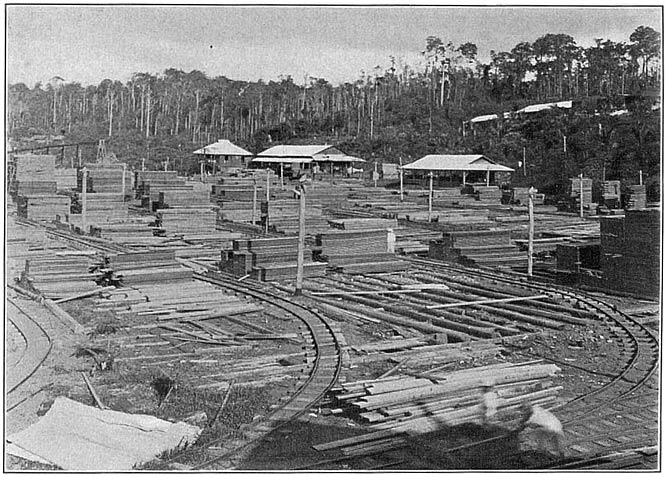

TAYABAS PROVINCE, the second largest, is on the Pacific coast of the Philippine Islands. The province

is noted for its copra, abacá and corn which are raised for export. Mineral resources

are abundant in the Bondoc Peninsula where gold, coal, and petroleum are found. Aside

from agriculture and mining, however, there are other industries such as hat-making

and lumbering. There is a lumber camp at Guinayañgan and a modern saw and planing mill in Lucena. The Botocan Falls, where a stream 40 feet wide makes a leap of 190 feet, could supply the entire province

with light and power for all its needs.

Lucena and Atimonan

The spin to Lucena and Atimonan, both in the Province of Tayabas over the South Road,

is a favorite one. On the east are the little town of Binañgonan de Lampon, a celebrated

port in the sixteenth century in the galleon trade, and the landlocked harbor of Hondagua,

destined to be the direct port of call of steamers coming from the Pacific Coast of

the United States and Canada.

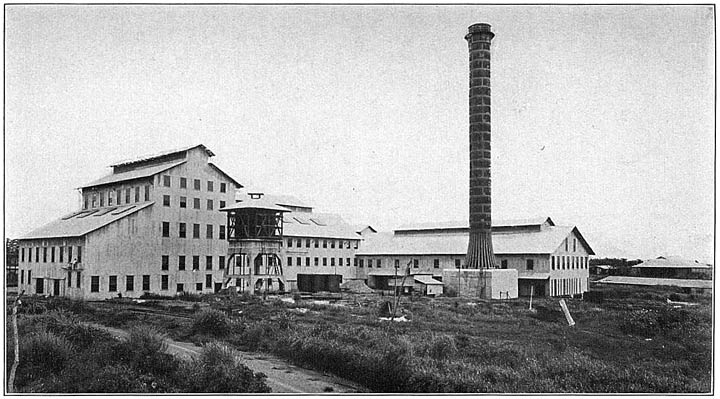

On the way, stop can readily be made at the town of Calamba, Laguna, about 37 miles from Manila. This is the birthplace of the Filipino author,

and patriot Dr. Jose Rizal. Although the house where he was born is no longer standing,

the site can easily be found opposite the church and market. Calamba has an added

importance in that the town has a modern sugar central, which the traveler should

not fail to visit.

Los Baños

A short detour can readily be made also at Los Baños (“The Baths”), a town which owes its name and its importance to the hot mineral springs

which abound in the neighborhood and have been found to be of great medicinal value

especially for the treatment of certain skin diseases and rheumatism. The springs

have been known for a great length of time. Even during the Spanish days the town

was a much frequented resort, a hospital with pools and vapored rooms having been built as far

back as 1571.

[79]

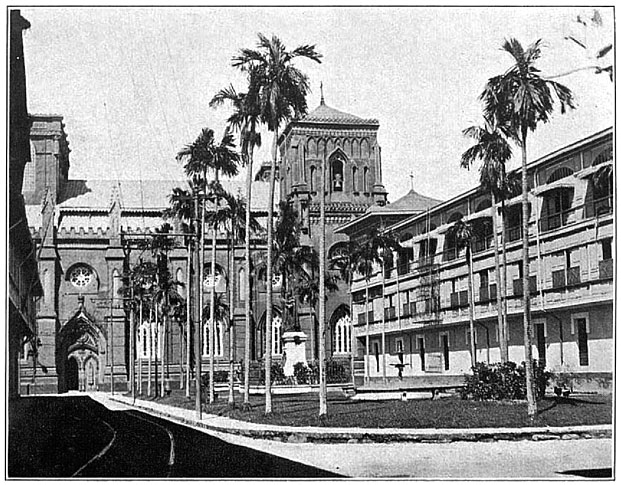

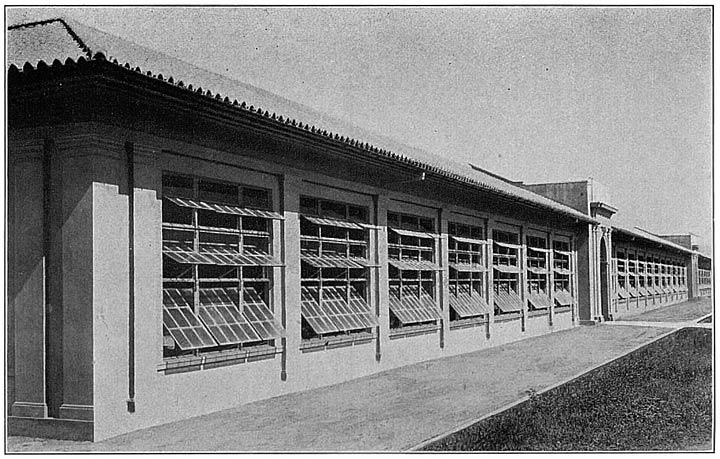

College of Agriculture

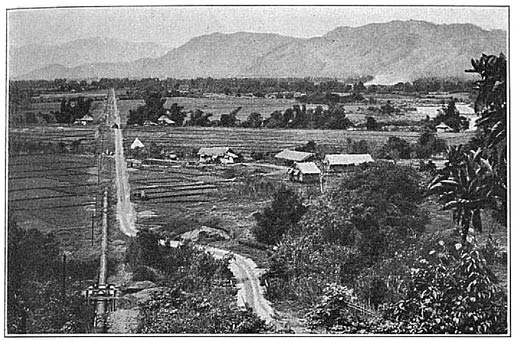

A short distance from Los Baños, and occupying an extremely picturesque side are the

palms and buildings of the College of Agriculture of the University of the Philippines, an institution which trains young Filipinos

in a calling which must for many years to come be the foundation of the economic prosperity

of the islands.

THE BICOL PROVINCES.—Farther south, are the provinces of Albay, Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, and Sorsogon,

known as the Bicol Provinces, because inhabited by Bicolanos. All four provinces are

noted for their beautiful mountain views and extensive plantations of coconut and

hemp. In Albay the forests are extensive, providing timber, rattan, pili-nuts, and gum for export.

Gutta-percha and Para rubber trees are extensively cultivated. There are wide pasture

grounds for horses, cattle, carabaos, goats, and sheep. The temperature is even and

the nights are cool and refreshing. There are also salubrious mineral springs, the

best known being the Tiwi Hot Sulphur Springs in the town of Naga.

The Province of Catanduanes abounds in gold, copper, and iron. The Batan coal mines

which are being operated are supplying several manufacturing and gas plants. There

are quarries of marble in Pantaon; gypsum deposits in Ligao; and lime in Guinobatan

and Camalig.

Camarines Norte is rich in mineral resources. Gold is found in many places, exploitation being actually

carried on in Paracale. There are also deposits of iron, silver, lead, and copper.

Camarines Sur, on the valley of Bicol River and the Caramoan Peninsula, is noted for its rattan

industry. Hemp planting and fishing and coconut growing are the other principal industries.

Sorsogon occupies the southernmost tip of the Bicol Peninsula. The largest indenture in its

irregular coast is the gulf of Sorsogon, a land-locked body of water and one of the

finest harbors in the Philippines. The land is mountainous and covered with excellent lumber suitable

for ship-building [80]and furniture making. In the forests rattan grows in abundance and is exported to

all the provinces. The chief products are abaca and coconuts.

Sorsogon, the capital, located on the gulf, is an important commercial town. Pilar

is noted for her shipyards; ships, lorchas, and boats are built here from the fine

timber grown nearby.

Sceneries

Among the sceneries are the Guinulajon waterfalls, near the capital, the wild vegetation

and the cataracts along the Irosin River, the medicinal hot springs of Mombon, Bujan,

and Mapaso, together with the beautiful panorama from the Bulusan Volcano are especially

striking. Like Mount Vesuvius, Mount Bulusan has an old crater, and a new cone that

has appeared on the slopes. Inside the crater, about 500 feet deep, are two pools

of hot water which form the basin from which the Irosin River rises.

A great event in the history of Sorsogon was the invention of a hemp-stripping machine

by a priest named Espellargas, about 1669. The invention was made in Bacon, where

it seems hemp then abounded. The contrivance was ingeniously constructed and was quite

well adapted to local conditions.

Historical Incidents

Many of the galleons that the Spanish Government used in the Manila-Acapulco trade

were built in Sorsogon, especially on the Island of Bagatao, at the entrance of Sorsogon

Bay. Many of these ships were wrecked while navigating the waters of Sorsogon, because

they laid their course for Mexico via the San Bernardino Strait, a passage which abounds

in dangerous currents, shoals, and rocks. The galleon San Cristobal was wrecked in 1733 near the Calantas Rock. In 1793, the galleon Magallanes also ran aground at this place. Other vessels went down in this neighborhood from

time to time, as the Santo Cristo de Burgos, in 1726, near Ticao, and the San Andres, in 1798, near Naranja Island.

[81]

Volcanoes

Peerless Mayon of the perfect cone is in Albay, the volcano of Isarog in Ambos Camarines,

and Bulusan in Sorsogon.

For those who love mountain climbing, the ascent to the peak of Mayon Volcano should

not be missed.

The actual ascent, though arduous, is perfectly practicable. It requires from a day

and a half to two days from Albay. By leaving the latter place on horseback at noon

it is possible to ride one-third of the way up before dark. Leaving the horses at

the camping place, the summit can be reached and the return trip made to Albay on

the following day. A vivid description of the trip, written by Dr. Paul C. Freer,

Director of the Bureau of Science, follows:

“This great volcano rises from the seacoast, between Legaspi and Tabaco, in the form

of an almost perfect cone—the white houses and church towers of the surrounding settlements

and the deeper-colored verdure of the trees at its base, higher up the brilliant green

of the bare glass streaked here and there by old lava flows, and still higher a grayish

black cinder and ash cone tapering to the peak, with a small plume of steam escaping apparently from the extreme

summit. The ascent is interesting, but may, if proper precautions are not taken, be

dangerous. The rise of the land in the first part is scarcely perceptible, the road

winding through forest interspersed with great plantations of manila hemp; above,

as it becomes steeper, the latter give way almost entirely to tropical jungle; and

finally the path emerges into cogonal, which extends as far as the angle of the slope

will permit. Here and there the entire slope is cut by deep ravines, indicating old

lava flows. The way up the cone at first invariably lies in one of these ravines,

but now and again the mountain climber is compelled to cross rolling cinder beds only

a few inches deep, and lying upon a harder base, almost invariably with an abrupt

descent below. The angle is so great that every precaution must be taken, as a slip

would prove fatal. A good steelshod alpenstock is practically indispensable. The last

five hundred feet are along the perpendicular lava and tuff crags of the summit, the

ambitious climber clinging to the latter with hands and toes, wherever support is

possible and slowly [82]working his way to the edge of the crater. Finally, standing upon the rotten foothold

afforded by the latter he looks down into what appears to be a deep dark well from

which small quantities of sulphur-laden gas escape. Around him on the margin jets

of steam arise; the ground on which he stands is hot, the boys carrying the canteens

are far below, the dry breeze helps the evaporation, and he realizes that he is very,

very thirsty. However, the view from the top repays all effort. The entire southern

portion of Luzon is visible, stretching away in a succession of fields, forests, and

diminutive villages, to the straits of San Bernardino, across which Samar may be seen,

and even Leyte, on a clear day. The lake of Bato, the interisland waters, and finally

Burias are seen to the west; to the north there appears apparently one unbroken stretch

of land with here and there a glimpse of the sea; and the Gulf of Albay with the towns

of Legaspi, Tabaco, and Daraga, as well as the smaller islands to the east, seem to

be almost within a stone’s throw. I have been high up on the slopes of Etna, at the

entrance to the Val del Bobe, from which many travelers maintain the finest in the

world is to be obtained, but I certainly think that from the summit of Mayon the vista

surpasses the one from its sister volcano in Sicily.… Mayon Volcano is decidedly one of the show places of the Philippines, and the wonder is that many of our visitors

do not take the opportunity to make the ascent.”

BULACAN PROVINCE is named from the Tagalog word “bulac” meaning “cotton” which was once the principal

product of the region. Together with the Provinces of Pampanga, Tarlac, and Nueva

Ecija, the province forms what is commonly known as the region of Central Luzon.

Description and History

The soil, which is of alluvial and volcanic origin, is rich. Rice, corn, sugar, pineapples,

bananas, betel nut, mangoes, and all sorts of vegetables are raised in the well irrigated

and low-lying lands. The nipa swamps which supply most of the nipa thatches, vinegar,

and alcohol are the principal stand-by of a great many people. The forests cover over

89,980 hectares and yield good commercial timber and many minor forest products.

[83]

Aside from agriculture and mining, the industries of the province are making hats

(Baliuag) and silk textiles, weaving, tanning, fish breeding, distilling alcohol,

and furniture-making. Baliuag, Meycauayan, Obando, Polo, Hagonoy, and San Miguel are

the centers of these industries.

In the events which followed the arrival of the British in 1762, the province figured

conspicuously, serving as a center of resistance during British occupation of Manila.

The Spanish Governor, Anda, just before the capitulation of Manila escaped to this

province where he organized a government of his own to carry on hostilities against

the British and to hold the country in its loyalty to Spain. In the encounters, however,

between Anda’s forces and the British, Anda’s resistance was overcome, and Bulacan

like the other provinces fell into British hands.

Some of the most notable events in the Philippine revolution took place in Bulacan

Province. It was at Biac-na-Bato, in the mountains of Bulacan, where in December of 1897 the famous Pact of Biac-na-Bato

was concluded, and the town of Malolos was for some time the capital of the Philippine Republic. Here, in the historic church

of Barasoain, the Congress which drafted the Constitution of the Republic held its

sessions. Conspicuous figures of the revolution like M. H. del Pilar and Mariano Ponce

whose names are connected with the period of propaganda are sons of this province.

Attractions

Among the other attractions are the Mineral Baths at Marilao, on the Manila north road, and Sibul Springs near San Miguel de Mayumo. This is a popular health resort only about three hours

ride from Manila. The water of the springs have enjoyed a considerable reputation

for a long time. They are very beneficial in diseases of the intestinal tract, especially those of a chronic and catarrhal nature. Owing to the gases which the

water contains the baths are most refreshing.

PAMPANGA PROVINCE is said to be the lowest and most level of all the provinces. It is the chief sugar

raising province in Luzon. Some of the islands’ modern sugar [84]centrals are there. Besides farming, sugar making, lumbering, and fishing, the people

are engaged in several other industries such as distillation of alcohol, buri hat

making, and pottery.

Historical Incidents

About the middle of the seventeenth century, two great rebellions broke out in the

province. The first of these took place in 1645 as a result of the injustices connected

with the collection of tributes. It spread quickly and extended to Zambales. The second

revolt took place fifteen years later as a result of the forcible employment of natives

in the work of cutting timber and of the failure of the Government to pay for large

amounts of rice collected in Pampanga for the use of the royal officials. The leader

of the rebellion was Francisco Maniago. It spread rapidly among the inhabitants of

the towns along the banks of the Pampanga River, and was only suppressed after drastic

measures were taken by Governor-General de Lara.

Pampanga was one of the first provinces to start the Revolution. During the early

part of the war Mariano Llanera commanded the Revolutionary forces. Later Tiburcio

Hilario took possession of the province as governor in the name of the Revolutionary

Government.

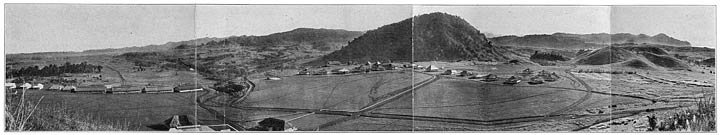

Attractions

Among the attractions are the sugar centrals, Camp Stotsenberg, one of the principal Army posts and an airplane station of the United States, dome-shaped

Mount Arayat, about 3,300 feet in height and fairly easy to climb, and San Fernando,

the capital, with its handsome capitol and school buildings grouped about the pretty

plaza.

Arayat, a picturesque village lying at the foot of the mountain of that name is an ideal

spot for those desiring to camp out. Nearby is the little barrio of Baño where there

is an ancient tile bath constructed by the Spanish Friars. It consists of a tile lined

tank some forty feet in length and of varying depths, filled by a crystal-clear spring

which gushes into it from a grassy bank just above.

[85]

Mount Arayat is a perfect cone that rises majestically from the immense plain of Central

Luzon, and is visible for miles around, presenting the same conical shape no matter

from what direction viewed.

Several trails lead to the top of the mountain from where a wonderful panorama can

be seen. It was an insurgent stronghold during the war, but its heights were scaled

by American troops and its defenders dispersed. Scientists state that the mountain

is an extinct volcano and local tradition has it that the original town of Arayat

was destroyed by an eruption and covered by ashes.

TARLAC PROVINCE is also in the central plain of Luzon. The province has two distinct geographical

areas. The northern and eastern parts consists of an extensive plain while the rest

is covered with mountains which abound in timber suitable for building material and

furniture making. The minor forest products are anahaw, palasan, rattan, honey and

bojo for sawali.

There was an uprising in this province somewhere in 1762 headed by Juan de la Cruz

Palaris. In 1896 the province was one of the original eight provinces where a state

of war was declared to be in existence against the Spaniards. When Malolos was evacuated

by the Philippine Revolutionary Government, the town of Tarlac became for a time the

central headquarters.

Among the attractions are the medicinal springs in O’Donell in the municipality of

Capas and those of Sinait.

NUEVA ECIJA PROVINCE is the rice granary of the Philippine Islands, being first in the production of the

cereal, Pangasinan coming second. The rolling hills towards the mountains are suitable

for pasture lands. The mountains are thick with untouched forests that yield fine

wood and other minor products. In the mountains and rivers gold is found. The province

was one of the first eight provinces to raise the standard of revolt in 1896. It has

a number of flourishing towns at present, due to the continuous boom in the rice market.

There are many mineral hot springs, the [86]ones at Bongabon and Pantabañgan being the most important. Among the attractions are

the irrigation system in San Jose which supplies water over an extensive territory

and the Government Agricultural School at Muñoz which is attended by many students from all the provinces, and which is

noted for its unique method of practical instruction.

Attractions

BATAAN PROVINCE occupies the whole of the peninsula lying between the China Sea and Manila Bay. It

is a province of various peculiar phenomena. Northwest of Dinalupihan is a small conical

mountain, 250 meters high, which has a fresh water lake at the top. In the neighborhood

of Malasimbo are a few shallow marshes, the shores and waters of which are tinted

red by dust said to be formed from the remains of microscopic animalculæ. Near Orani

is a bed of iron hydride which the people of the region used to make into paints for

walls and carriages. There are also deposits of clay of which “pilones” are made.

There is also a large deposit of shells which are burned for lime used in the indigo

and sugar industries. On the shores of Orani is a fresh water spring that rises from

a spot covered daily by the tides. Near the town of Orion is a quaking bog, impassable by either man or beast. Another, smaller one, is found in Ogon, Balanga.

Historical Incidents

During the first two decades of the seventeenth century, the coast of Bataan was more

than once the scene of battles against the Dutch. The first of these encounters took

place in 1600 off the coast of Mariveles. The Dutch were commanded by Admiral Van

Noort, while the Spanish-Filipino army was led by the historian, Antonio de Morga,

then an order of the Manila Real Audiencia. The Spanish-Filipino squadron suffered

heavy losses, but the Dutch were nevertheless forced to retreat. Nine years later,

the Dutch again appeared off the Mariveles coast. This time they were led by Admiral

Wittert, against whom Governor Silva sent a hastily fitted out squadron of six small

vessels manned by Spaniards and Filipinos. The Dutch were defeated. In spite of these

[87]reverses, the Dutch continued their hostile visits to the Philippines. In 1646, they

bombarded Zamboanga, unsuccessfully attacked Cavite, and finally effected a landing

in Abucay, Bataan. Here they committed depredations and massacred more than four hundred

Filipino soldiers who had laid down their arms. They were not driven away until after

a long siege.

Mariveles

The town of Mariveles and Mount Mariveles are the principal attractions. The town has an important harbor where the ships are

detained and fumigated when necessary before entering or leaving Manila Bay. West

of the town is a quarry of white stone called by the Spaniards, “mármol de Mariveles.”

This stone has served as material for the pedestal and column of the statue of Charles

IV in Manila. A well near the quarry produces siliceous water.

There is a beautiful legend connected with the town of Mariveles. A Spanish girl by

the name of Maria Velez, who was a nun in Santa Clara Convent, fell in love with a

friar, with whom she later eloped to Kamaya, there to await a galleon on which they

intended to secure passage for Acapulco. The elopement caused excitement in Manila, and the corregidor (magistrate) with a few men was sent to Kamaya in search of the refugees. It is said

that in memory of the persons involved in this story Kamaya was given the name of

Mariveles, the big island to the south was named Corregidor, the little island to

the west was called Monja (nun) and another small island, off the Cavite coast, was

called Fraile.

Mount Mariveles

Mount Mariveles rises in the midst of the whole peninsula of Bataan. It is about 4,700 feet in height

and forms a conspicuous object from the city especially when illuminated by the brilliant

hues of the sunset sky. Though once an active volcano its sides are now covered with

vegetation and practically the whole of its slopes down to a very short distance off

the shore are virgin tropical jungles. The ascent of the mountain can be conveniently

made from a day and a half to two days from Lamao, where the Philippine Government

maintains [88]a scientific experimental farm. The trail up the mountain passes along a ridge with

here and there steep but short slopes. As the ascent is made the trees become noticeably

smaller and orchids, ferns, mosses and the like much more abundant. From the first

peak 2,800 feet high, the traveler can obtain a view of what Agassiz termed the greatest

wonders of nature—the sea, the mountains, and the tropical forests.

The view from the very top surpasses that from the first peak. To the east lies the

bay, with Manila and Cavite in the distance; to the south nestles Corregidor Island

with the surf beating its shores; beyond is the China Sea, dotted here and there with

specks of vessels bound to and from Hongkong or the other islands; to the north and

west is a semi-circle of forest-covered peaks, standing as sentinels guarding the

amphitheater-like crater; and to the northeast lie the cultivated fields of rice and

sugar cane, studded here and there with the church steeples that mark the sites of

the towns.

ZAMBALES PROVINCE.—North of Bataan along the western coast of Luzon is the Province of Zambales. It

has two important harbors that are well sheltered—Olongapo and Subic. Olongapo is

a naval station which boasts of one of the largest floating dry docks in the world.

Zambales was also visited by the Dutch during the early part of the seventeenth century.

It was in 1617 that Admiral Spielbergen, with a powerful fleet appeared off the coast

of Playa Honda. The Government forces, under the command of Juan Ronquillo, sallied

out and engaged the Dutch squadron. Spielbergen displayed much bravery, but was defeated.

Naval Station

The only points of particular interest are the Naval Station along the coast which is, however, practically abandoned, and the fortifications

on Grande Island, at the entrance to the bay. To visit either of them permits from

the military or naval authorities are necessary. The floating dry-dock Dewey whose voyage [89]from the United States was a matter of much public interest in 1906 is now located

here.

PANGASINAN PROVINCE is the second largest rice producing province in the archipelago. Tobacco and coconuts

are also principal products. The swamp lands and the tide flats are sources of nipa

thatches and alcohol. Mongo, cogon, sugar cane, and mangoes are also raised extensively.

Salt Making and Industries

Along the tidal flats, salt making is so universal that the province has been named “Pangasinan,” meaning, “the place

where there is salt.” Large parts of these same tidal lands are converted into artificial

fish ponds with suitable gates that admit water during high tide. Even as far south

as Bayambang, the overflowed lands of the Agno River have been converted into similar

ponds where quantities of fresh-water fish are obtained and shipped to Manila in large baskets containing water.

The famous Calasiao hat made from the leaf of the buri palm comes from Pangasinan.

Mat-making is an industry in Bani and Bolinao. Lingayen uses the palm fiber for making sugar

sacks and San Carlos for the “salacot” or native helmet. Calasiao, Mañgaldan, and

San Carlos prepare the “tabo” or native cup from the coconut shell. Binmaley and Dagupan

manufacture the “sueco” (wooden shoe), from the woods cut in the Zambales mountains.

San Carlos, Binmaley, Santa Barbara, Malasiqui, and Bayambang have brickyards and

manufactories of pottery. Mañgaldan is famous for its indigo blue and blue-black dyes.

Historical Events

Historically the province is important in that it was there that in 1574 the Chinese

pirate Limahong after his repulse in Manila appeared with his vast army at the mouth

of the Agno River and tried to found a settlement on its banks. This attempt, however,

was a failure.

During the period from 1660 to about 1765, two important revolts occurred in Pangasinan.

The first was in 1660 led by Andres Malong, who attempted to establish a great kingdom

[90]with Binalatoñgan as capital and comprising all of northern and western Luzon as far

south as Zambales and Pampanga. The second revolt was led by the famous Pangasinan

leader, Juan de la Cruz Palaris, often known as “Palaripar.” It took place in 1762,

caused by the injustices of the tribute. Its center was also at Binalatoñgan. It lasted

over two years, ending with the capture and execution of Palaris in 1765.

MOUNTAIN PROVINCE.—The Mountain Province is the third largest province in the Philippines. It comprises

the vast mountainous territory between the Provinces of Cagayan, Isabela, Nueva Vizcaya,

and the Ilocos. It is made up of several sub-provinces.

Bakun district in the sub-province of Amburayan has some of the most striking rice terraces thousands of feet high. It is a region

surrounded by high precipices, so that parts of the trails to Bakun consist of ladders

hundreds of feet high on the sides of the cliffs.

The sub-province of Apayao contains one of the richest virgin forests in the Philippines but because of the

difficulty of transportation lumber is not cut on a commercial scale. There are also

deposits of copper and ore as well as limestone but they are little explored.

The sub-province of Benguet is at present the most important gold-mining district in the Mountain Province. The

Igorots had exploited the mines long before the coming of the Spaniards and it is

said that because of the experience already acquired, the Igorots are today more skillful

gold miners than those who use their knowledge of chemistry and mining engineering.

Hot springs are found at Klondikes, Daklan, and Bungias. Coal deposits exist in Mount

Kapangan.

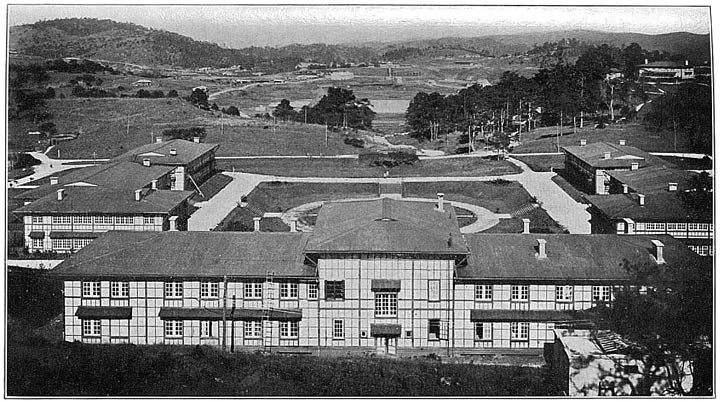

The city of Baguio, the capital of Benguet, is situated in the southwestern part of the province. About

160 miles to the north of Manila, it is built high up among the Benguet mountains.

It ranges in elevation from 4,500 to over 5,500 [91]feet, and is surrounded practically on all sides by high mountains. The city at present

is the summer capital of the Philippines. For a fuller description see page 61.

The sub-province of Bontok is exceedingly mountainous. Besides agriculture and pottery making, the principal

industries consist of basket making, lumbering, weaving, and metal working. The women

by means of their hand-looms weave a great deal of high colored cloth out of yarn

which they get by barter from the people of Isabela and Abra. The men manufacture

head-axes and knives.

Ifugao Rice Terraces

The sub-province of Ifugao is famous for the remarkable rice terraces along its mountain sides. Nowhere in the

Philippines is irrigation developed to the point reached in this sub-province. There

are approximately 100 square miles of irrigated rice terraces that are watered by

great ditches several miles long. The terraces are all buttressed with stone walls

which measure a total length of about 12,000 miles. These terraces have been built

without any knowledge of engineering. It is believed that the construction of the

present terraces and irrigation systems has taken from 1,200 to 1,500 years of time.

Generation after generation had toiled on them patiently. The Ifugaos have so utilized

every drop of available water supply that in most places no more ditches can be constructed

for lack of water.

The terraces are built of stones mined near by, of which there are extensive areas.

No animals are used for field work everything being done by hand. Salt springs and

deposits of rock salts are also found in several places.

The sub-province of Lepanto is next to Ifugao in the number of rice terraces. Camotes, pineapples, sugar cane,

and cotton are also raised. Lepanto and Benguet are the regions having the most minerals

in Luzon. All the mountain ranges have millions of pesos worth of copper ore deposits.

Mankayan is the center of the copper mining industry. Here the Spaniards found the

natives using the Chinese method of mine smelting.

[92]

Gold Mining and Industries

Suyok is the gold mining center. Here is found one of the most striking features of

the world. The whole side of a range of mountains, about 15 kilometers across, slides

down to the valley, and on this slide, named the Palidan Slide, are found parts of

gold veins which must have their connection somewhere else.

The household industries are well developed. Clay products, such as pots, jars, and

pipes are made for export. The men are experts in metal-working. They make weapons,

pots, and spoons out of copper which they mine and smelt by native process. They also

manufacture iron or steel spears, bolos, knives, and tools of all sorts, which they

sell to or barter with the natives of the lowlands. They also carve wood into images,

bowls, ornaments, and other utensils.

The women make sufficient cloths for their own use and for sale. They spin, dye, and

weave the cotton raised there.

LA UNION PROVINCE occupies a narrow strip of land immediately north of the Province of Pangasinan and

west of the Mountain Province. Tobacco, rice, sisal, hemp, sugar, coconuts, corn,

and cotton form the most important products. At the foot of Mount Bayabas is a hot

salt spring. The Manila Railroad operates lines as far as Bauang. San Fernando, the capital, may be reached either by boat or by automobile from Bauang.

Industries

ILOCOS SUR PROVINCE.—Immediately north of La Union is the Province of Ilocos Sur, a region specially adapted

to the cultivation of maguey the fiber of which constitutes the principal export.

But because the soil will not support the population a great many persons have turned

to manufacture and trade. This has given rise to industrial specialization in different

towns. Those along the coast extract salt from the sea water and export it in great

quantities to inland provinces. In San Esteban, there is a quarry of stone from which

mortars and grindstones are made. San Vicente, Vigan, and San Ildefonso specialize

in woodworking, the first in carved wooden boxes and images and the others in household

[93]furniture. Most of the wood used in these handicrafts is imported from Abra and Cagayan.

Bantay is the home of skilled silversmiths. In the other towns saddles, harness, slippers,

mats, pottery, and hats are made and exported to some extent. Sisal and hemp fiber

extraction and weaving of cotton cloth are common household industries throughout

the province.

The province embraces within its confines some of the oldest towns in the Philippines.

Besides Vigan several other towns already existed in this region before the close

of the sixteenth century; namely, Santa, Narvacan, Bantay, Candon, and Sinait.

Just above Narvacan, on the highway which runs along the beach is an ancient watch-tower

and a stretch of road bordered by a curious brick retaining wall of Spanish construction.

Numerous ancient shrines are also to be seen along the Ilocos roads where the pious

prayed that Heavenly favor might be shown them in their journeys.

The towns of Paoay and Batac are noted for their magnificent churches which are worth

traveling a long distance to see.

Historical

Two important uprisings are recorded in the history of Ilocos Sur—the Malong rebellion

in 1660 and the Silang rebellion in 1763. Malong, who was trying to carve out a kingdom

for himself in Pangasinan and the neighboring territory, sent his two able generals,

“Count” Gumapos and Jacinto Macasiag to the north to effect the conquest of this region.

Gumapos and Macasiag, however, proceeded only as far as Vigan, from which place they

were recalled by Malong. Diego Silang, who led the great rebellion of 1762, dominated

the greater part of Ilocos Sur. He fought pitched battles with the Spanish forces

at Vigan and Cabugao and practically succeeded in establishing a government of his

own in Ilocos Sur.

ILOCOS NORTE PROVINCE occupies the whole of the coastal plain in the northwestern corner of Luzon. This

province is noted for the many revolts that occurred there, [94]from the beginning of Spanish rule to the first decades of the nineteenth century.

The two most important were those caused by the general discontent over the tobacco

monopoly and over the wine monopoly, which occurred in 1788 and 1807 respectively.

The mountains surrounding the province are covered with fine timber trees. Resin,

honey, and wax are also found on their slopes. A few grottos or caves are found in the interior. There are a number

of stone quarries. Limestone is found in at least three places, while the beach supplies

a great amount of coral for road building. There are also deposits of manganese and

asbestos which are being exploited.

The weaving of textiles—towels, blankets, wearing apparel, and handkerchiefs—is the

principal industry among women. Mat-making and the pottery industry are also well

developed.

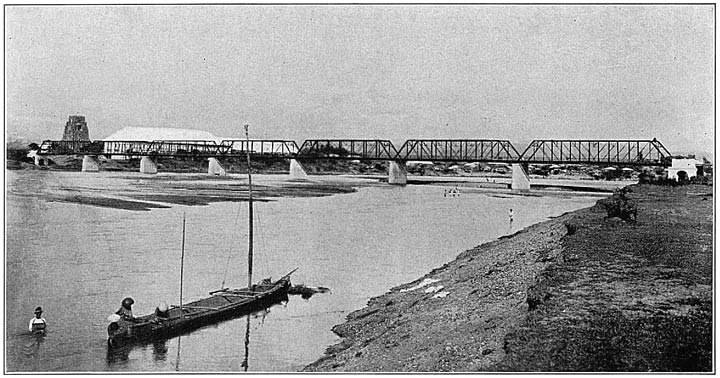

Laoag, the capital, has a population of about 40,000. It is entered from the south

by crossing the longest bridge in the islands. Laoag plaza, on which the provincial

buildings front, is well cared for and the ancient bell tower on the opposite side

is said to resemble a famous Italian campanile.

Bangui is “farthest north” in Luzon where the highway ends. Its climate is cool resembling

that of a California summer. Woolen clothes may be worn with comfort in the cold season.

It is always swept by cool breezes. The view of sea and land from the crest of a hill just before Bangui

is entered will hold the attention of even the most travelled tourist.

ABRA PROVINCE is south of Ilocos Norte. It is a beautiful mountainous region. It is considered

to be the seismic center of Northern Luzon. It is drained by the voluminous Abra River

which is the highway to the Province of Ilocos Sur. The valley drained by this river

and its tributaries is covered with luxuriant vegetation. Corn, tobacco, and rice

are the most important products. The mountains are covered with forests containing

timber eminently suitable for construction. There is gold dust along the Binoñgan

[95]River in the town of Lacub. Of mineral springs that of the Iomin River is the most

important. This has a temperature ranging from 70 degrees to 80 degrees Fahrenheit

with a flow of 3 to 4 cubic centimeters per second.

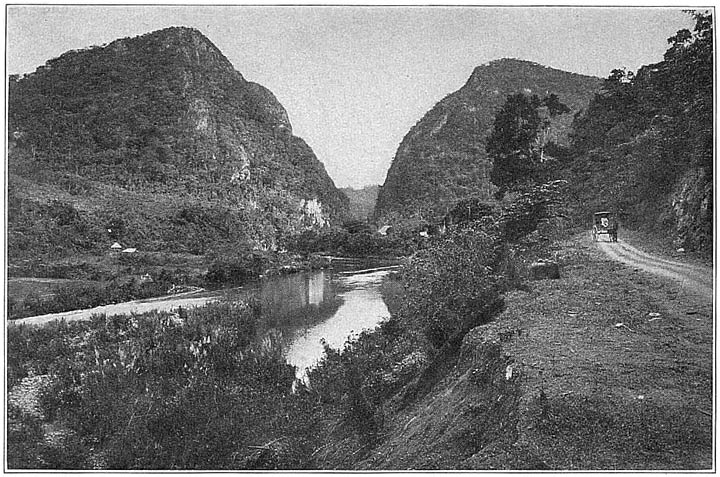

Cagayan River

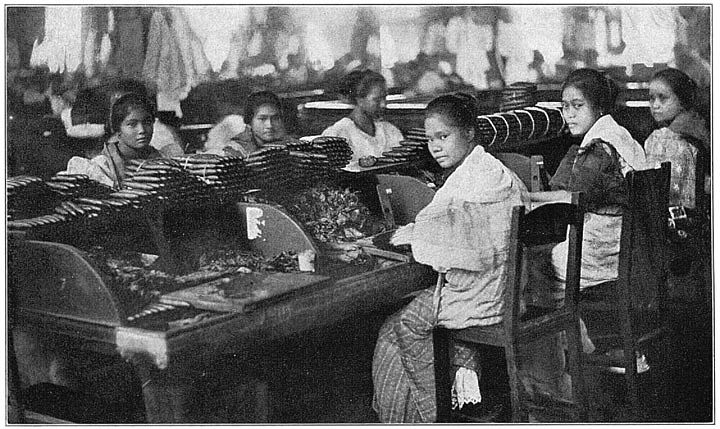

THE CAGAYAN VALLEY.—Adjoining the Mountain Province in the very northeastern corner of Luzon is the Province

of Cagayan. Together with the neighboring Provinces of Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya to

the south it forms what is known as the Cagayan Valley. Something of these great tobacco

provinces can be seen by taking the steamer from Manila to Aparri and then sailing

up the Cagayan River. This is a Mississippi, a Nile of a river, navigable by interisland steamers for twenty-five miles. Its

chief importance lies in its periodical inundations, which, leaving their deposits

of alluvial loam along the strips of lowland by the banks of the stream, make it the

finest tobacco country of this part of the world. This crop has for a very long time

been the staple source of wealth, though other plants can be cultivated with success.

How great is the productivity of the soil, despite the exhausting effect of tobacco

upon it, may be gathered from the following remark made in an official report. “The

‘good land’ was understood to be those parts fertilized annually by the overflow of

the river.… The other land was not considered first class because it could only produce

tobacco for ten or twelve years without enrichment, the subject of fertilizing never

having received any attention from the planters of that region.”

By small boats it is possible to reach Cauayan, Isabela. From there the road is so

nearly completed that autos can be taken to Santa Fé, Nueva Vizcaya, where it divides,

one branch, an automobile road, leading to San Jose, Nueva Ecija, and thence to Manila;

the other a horseback trail to San Nicolas, Pangasinan, a short and easy stage to

the railroad. Among the sights is a salt-incrusted mountain, a dazzling landmark for miles around in Nueva Vizcaya. The people thereabouts often

place small objects, such as baskets, under the drip of the salt springs. These become

coated [96]with salt in such a manner that they appear to be of pure marble.

Isabela and Palanan

Like many other provinces Isabela Province was the scene of important uprisings. In

1763, for example, stirred by the influence of the Silang rebellion in Ilocos, the

people of Isabela revolted, led on by Dabo and Juan Morayac. The centers of rebellion

were Ilagan and Cabagan. Again in 1785, another revolt broke out. This time the rebellion

was led by Labutao and Baladon. The rebellion was caused by the grievances of the

people against the collection of tribute and the enforcement of the tobacco monopoly.

The historical spot of Isabela is the little town of Palanan on Palanan Bay, on the Pacific Coast. The bay is exposed to the weather and the anchorage is reefy,

while the town is separated from the rest of the province by great mountains which

make communication and travel difficult and dangerous. It was in this town that General

Emilio Aguinaldo retreated and maintained his headquarters until his capture by General

Funston by a ruse in March, 1901.

Salinas Salt Springs

NUEVA VIZCAYA PROVINCE is south of Cagayan on the Pacific Coast of Luzon. It contains vast areas of fertile

public lands suitable for rice, tobacco, sugar, coconuts, beans, potatoes, coffee,

and abaca, practically untouched, as well as virgin forests filled with all classes

of valuable timber. The province is the gateway to and granary of the tobacco-producing

provinces to the north. The climatic conditions of the province are unsurpassed. There

are places the climate of which is similar to that of Baguio. There are also places

of scenic beauty, such as Salinas, which are not inferior to world-famous objectives

of tourist travel. The salt springs at Salinas have been from time immemorial the

source of this essential food element to the peoples of even distant regions.

MINDORO PROVINCE is named after the Spanish phrase “mina de oro” or “gold mine,” as mining is said

to have once been a great source of wealth in the region. The province is co-extensive

in territory with the Island of Mindoro, [97]southwest of Luzon. Rice, copra, abacá, sugar, and corn are the principal products.

Along the coast are extensive nipa swamps.

Mineral Deposits

Gold is found in the Rivers of Binabay, Baco, Bongabong, and Magasauan Tubig. Coal

of good quality is found north and west of Bulalacao, white marbles northwest of Mount

Halcon, slate deposits near the headquarters of Pagaban and other rivers of the western

coast, sulphur, and gypsum on Lake Naujan, and south of Calapan, hot springs between

the sea and the northwestern part of Lake Naujan, and salt springs in Damagan, Bulalacao.

Guano deposits are found in the caves.

Submarine Garden

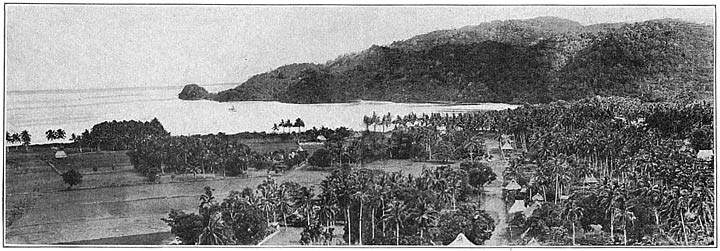

An interesting two-day trip from Manila is that to the landlocked harbor of Puerto Galera at the northern end of the island. The attraction of the place lies in the fine scenery

along the coast and in the unusual transparency of the water, which permits visitors,

especially if glass-bottomed boats are at hand, to inspect the varied life which teems

in the depths below. There is here as on the coast of Batangas a marine garden of bewildering and exquisite beauty. Nature

seems to have made special effort to crowd beneath a few acres of sea all of the most

entrancing wonders of the deep. There is coral of every design, color, and variety.

There are thousands of plants which present a wealthy and gorgeous harmony of color.

There are myriads of wonderful fish which outrival the coral and the vegetation in

variety and richness of hue. Some are as green as grass, others as gold as a guinea.

There are at present no regular boats making the trip and special arrangements will

have to be made in order to be able to visit the place.

PALAWAN.—The province of Palawan occupies the long and narrow Island of Palawan situated between

Mindoro on the north and Borneo on the south. Besides this long and narrow island

the province includes about 200 other small islets. A great part of the island is

still unexplored, the island itself not being accessible to the traveler. The chief

[98]industries of the people are fishing, gathering trepangs, sea-shells, and edible birds’

nest on the limestone cliffs near the shore.

The proximity of the island with the Dutch East Indies and to Borneo puts it in a

very advantageous position commercially. It is also favored by valleys of great fertility

and by well protected harbors.

Iwahig Penal Colony

Among the places of special interest in Palawan may be mentioned Balabac on the island

of the same name. It was to this island that many of the Filipinos were exiled in

1896 because of alleged complicity in the Katipunan which in August of that year raised

the standard of revolt. The Iwahig Penal Colony about 8 miles from Puerto Princesa,

the capital, is also easy of access. This is a novel experiment in the reformatory

treatment of criminals. Here have been gathered under the name of “colonists” over

500 convicts who have conducted themselves well at Bilibid prison in Manila. They

are put at entire liberty without any armed guard or any special restraint. All of

the petty officers are prisoners as are also all the police. Agriculture and various

trades are carried on, and, under certain conditions, the prisoners are given an allotment

of land and their families are allowed to join them.

Culion Leper Colony

To the north of the province is the little Island of Culion where the leper colony

is situated. There is no regular transportation except by the government cutter that

makes periodical trips, and the colony itself is not ordinarily open to visitors.

There are about 2,000 inmates in the colony and they are well taken care of by the Philippine Government, many having been cured completely

of the unfortunate malady. In minor matters the lepers form a self-governing community

electing their own council and supplying the policemen and other subordinate officials.

Underground River

On the west coast of Palawan, almost uninhabited and still largely uncharted, there

is a very remarkable underground [99]river. This has been explored several times by Government officials, a launch having in

one instance entered the mouth and proceeded under the mountain for more than 2 miles.

At present the river can only be reached by taking a long and expensive trip away

from the main routes of travel, but it is destined some time to be known as one of

the remarkable sights of the world.

ROMBLON PROVINCE.—The Province of Romblon has nothing of special interest to the tourist except the

town of Romblon which has one of the best natural harbors in the islands and the extensive

marble deposits which have been quarried and used for years and are now disappearing.

THE VISAYAS.—The “Visayas” is the general name given to the central portion of the Philippine

Archipelago. It includes the large Islands of Panay, Negros, Cebu, Bohol, Leyte, and

Samar, and a very great number of smaller islands and islets. Though greatly broken

up by mountains, these contain the most thickly populated districts in the Islands

and constitute by far the largest area inhabited by a single stock (the Visayan) and

speaking, though with many dialect variations, one language. Within this area are

the best sugar and some of the best hemp lands, and many other important products

of the Islands grow well. To the tourist, perhaps, they do not, outside of the cities

of Cebu and Iloilo, abound in “sights.” But the larger islands exhibit many fine vistas;

and the smaller ones, mostly mountainous, form with the surrounding tropical waters

a combination which, for color and variety of outline, rivals the Inland Sea of Japan

at its best.

SAMAR PROVINCE comprises the whole Island of Samar which is the fourth largest island in the Archipelago.

It lies southeast of Luzon and is separated from the Province of Sorsogon by the San

Bernardino Strait. The island is very rugged and nearly all of the towns are located

near the coast. Another characteristic feature of the mountain regions is the presence

of caves of which the most noted [100]is the Sohotan cave near Basey. River transportation is the chief means of communication.

Where the Spaniards first landed

To Samar belongs the distinction of being the first island of the Philippine Archipelago

to be discovered by the Spaniards. On March 16, 1521, Ferdinand Magellan sighted the

island, and the day following, landed on the little island of Homonhon. In 1649 the

greatest part of the Island of Samar became involved in a great rebellion which became the

signal of general uprising in the Visayan Islands and in parts of Mindanao. The cause

of the uprising was enforced labor in connection with shipbuilding. It lasted about

a year. The rebels fortified themselves in the mountains and there established an

independent settlement. From here they sallied forth from time to time and harassed

the Spanish forces sent against them.

ILOILO AND CAPIZ.—The Provinces of Iloilo and Capiz occupy the entire eastern portion of the Island

of Panay, immediately south of Romblon Island. They consist of an extensive plain

extending far back to the foot of a range of mountains that traverses the western

part of the island.

The Panay line of the Philippine Railway Company cuts directly through this plain

extending as far as Capiz, the capital of the province of the same name, immediately

north of Iloilo Province.

Attractions

The trip over the railroad takes the traveler past several points of interest. Just

beyond Ventura there are seen to the west of the tract a series of high mountain cliffs

of white coral rock. These are honeycombed by caves of wonderful structure and great

beauty. One of the most beautiful resembles an immense stage, set with elaborate scenery.

Another of great extent and variety is entered by descending through a shaft resembling

a well. An hour’s walk from the entrance leads the traveler to a place where the roof

has collapsed [101]and trees have grown to gigantic heights, the cave continuing to an unknown distance.

The natural bridge of Suhut in the town of Dumalag, Capiz, is also worth visiting.

Near the natural bridge is a spring of sulphurous and salty water.

The City of Iloilo is described elsewhere, page 64.

Haciendas and Sugar Centrals

THE ISLAND OF NEGROS.—This island is divided into two provinces—Occidental Negros and Oriental Negros.

Occidental Negros is about three hours’ ride by boat from the City of Iloilo. It is

the most important sugar producing district in the Philippines. About 75 per cent

of all the exported sugar comes from this province. Bacolod, Bago, Talisay, San Carlos,

Binalbagan, and La Carlota are the centers of the sugar industry. There are about

518 haciendas and about half a dozen sugar centrals in actual operation. The sugar

centrals are well worth the visit and the traveler should not miss them. Other principal places of interest are Mount Canlaon, an active volcano and the Mambucal Hot Springs,

which is recommended by medical authorities.

The trip to Oriental Negros has to be made direct from Manila, although there are

boats from Cebu and Iloilo calling occasionally at Dumaguete, the capital.

Silliman Institute

The principal points of interest in Dumaguete are the old watch-tower on the plaza, built to guard against surprise by piratical

Moro fleets, and the buildings of the Silliman Institute. This latter is a high-grade

Protestant endowed school, with preparatory, classical, and industrial departments;

in it are enrolled some 500 students, representing a wide range of localities. It

was founded in 1901 with a gift of Dr. Horace B. Silliman, of New York, and is now

maintained by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions. The buildings are located

on the beach, about five minutes’ walk from the central part of the town.

[102]

Other Places of Interest

There are a few other places of some interest within a moderate distance of Dumaguete.

Among these are some hot springs, about 6 kilometers (about 4 miles) west of the town.

There is a fairly good horse trail to within a few minutes’ walk of them, and the

scenery along the route is picturesque. Of more interest is the active Volcano of Magaso, which lies 14 kilometers to the south. It is accessible by a good trail; and a horse

can be ridden to the top of the crater. The descent into the latter is not difficult.

CEBU PROVINCE.—The Island of Cebu which is co-extensive with the province of that name was discovered

by Magellan on April 7, 1521. The town was then under the rule of Raja Humabon, a

powerful chief who had eight subordinate chieftains and a force of some two thousand

warriors under him. Magellan made friends with Humabon and succeeded in baptizing

him, his wife, and as many as eight hundred of his men. Magellan also endeavored to

bring the people of Mactan under Spanish influence. In this attempt, he was killed

while engaged in battle with the people of Opon who were then under Chief Lapulapu.

First Spanish Settlement

Forty-four years after Magellan’s time, Legaspi occupied the town of Cebu which was

then under the rule of Tupas. Here Legaspi founded the first Spanish settlement in

the Philippines which he called San Miguel. The town, which was planned in the shape of a triangle, was defended on the land

side by a palisade and on the two sides facing the sea by artillery. The name of the

town was later changed to the City of the Most Holy Name of Jesus “in honor of an

image of the Child Jesus which a soldier had found in one of the houses.”

The establishment of the Spanish settlement in Cebu brought to this island the Portuguese

who then disputed the ownership of the Archipelago. In 1566, 1568, and 1570, Portuguese

expeditionary forces were sent to Cebu to drive away the Spaniards. First in 1568

and again in 1570, the [103]Portuguese blockaded Cebu, but in both cases the blockade resulted in a failure.

The plains yield as many as three crops of corn a year. Coconuts, sugar cane, abaca,

peanuts, bananas, pineapples, camotes, and tobacco are other products.

Industries

The island is rich in minerals, of which gold and coal are the most important. Industries

are well developed in Cebu. Good fishing banks found along the coast furnish the people

with food for local use and for export. Hogs and goats are raised for local use. Poultry

raising enables the people to export chickens and eggs to neighboring islands and

even to Manila. Cotton cloth, woven for local use and sinamay made from the fiber

extracted from banana and pineapple leaves, are exported. Much tuba, a native wine, is collected in the coconut regions.

The town of Cebu, however, existed as a prosperous native settlement before the discovery

of the Philippines by Magellan. For a description of the places of interest in the

city, see page 63.

BOHOL PROVINCE, the island southeast of Cebu, is noted for the two big rebellions against the Spaniards which occurred

in 1622 and 1744, respectively. The leader of the revolt in 1622, which was really

an armed protest against Jesuitical influence, was one by the name of Tamblot. The

uprising rapidly spread throughout the entire island; only the towns of Loboc and

Baclayon remained peaceful. The rebels retreated “to the summit of a rugged and lofty hill,

difficult of access,” and there fortified themselves. It took the government six months

to suppress this rebellion.

Rebellions

Another rebellion, no less formidable than the Tamblot uprising, broke out in 1744.

It gained strength in 1750 under the leadership of Dagohoy, who for a long time was

the whole soul of the movement. The rebellion affected almost the entire island and

lasted for over eighty years. The government sent several expeditions to put it down,

but without success. The rebels [104]established a local government and lived as an independent people. This was, perhaps,

the most successful revolt the Filipinos ever conducted from the viewpoint of duration

of resistance.

Attractions

Among the attractions are the mineral springs in Guindulman as well as those in San

Juan, Candon, Napo, Lubod, and Cambalaguin which are reputed to be efficacious for

curing skin diseases. Edible birds’ nests are gathered in the Cananoan Cave. Other

caves are found in Baclayon, Guindulman, Jagna, and Sierra Bullones. “Buri,” “ticog,” and “salacot” hats are made

in almost every town. The weaving of “piña” and “sinamay” cloth is a specialty in

Baclayon, Loboc, Jagna, and Duero, and “saguaran” weaving in Talibon, Inabanga, Baclayon,

and Jetafe. The commercial exploitation of the pearl and shell banks in the Bohol

seas has only recently been begun. The catching of the flying lemur and the tanning

and preparation of its hide is a new occupation. Most of the towns are found along

the coast so that a great portion of the inhabitants are engaged in coastwise and

interisland trade.

LEYTE PROVINCE and island, one of the largest and most fertile regions in the Visayan group, is

situated southwest of Samar and is separated from Samar by the San Juanico Strait,

said to be one of the most beautiful water-ways in the world. Hemp and copra are the

most important products exported. Coal is found in the towns of Leyte, Ormoc, and

Jaro. Asphalt is being mined in Leyte for street paving purposes. Gold is found in

Pintuyan and San Isidro; sulphur in Mahagnao; mineral springs in the crater of Mahagnao,

Ormoc, San Isidro, Mainit, and Carigara.

Where Mass First Celebrated

Limasawa, a little island south of Leyte, has the unique distinction of being the

place where mass was first celebrated in the Philippines. Toward the end of March,

1521, Magellan discovered this little island, which then appeared to be a prosperous

community. It was here that Magellan met Raja Calambu and Ciagu, who feasted the Spaniards

and exchanged presents with them. The Island of Leyte itself, then called Tandaya,

[105]was the first island of the Philippine Archipelago to receive the name of “Felipina.”

THE ISLAND OF MINDANAO.—This island is the second largest and potentially perhaps the richest of the archipelago.

It is divided into seven provinces—Zamboanga, Misamis, Lanao, Bukidnon, Cotabato,

Davao, Agusan, and Surigao.

Origin of Name

The term “Mindanao” or “Maguindanao” was originally given to the town now known as

Cotabato and its immediate vicinity. (See page 104.) The word is derived from the

root “danao” which means inundation by a river, lake, or sea. The derivative “Mindanao”

means “inundated” or “that which is inundated.” “Maguindanao” means “that which has

inundated.”

Islam

Islam was successfully introduced and firmly established in Mindanao by Sharif Mohammed

Kabungsuwan. He is believed to have established himself in this region toward the

end of the fifteenth century. He was also the founder of the Sultanate so that today

most of the inhabitants of Mindanao are Mohammedans. The Christian population came

from the northern islands. They immigrated into Mindanao to exploit the rich sections

of the islands. They have built their homes along the river basins and near the bays

accessible to commerce. In many cases they hold the important municipal positions

such as tax-collectors and teachers. The Moros who inhabit the interior valleys have

acknowledged the authority of their Christian brothers from the north and are living

peacefully with them.

THE PROVINCE OF ZAMBOANGA includes the whole of the western peninsula of the island. The central portion is

covered with dense forests containing much valuable hardwood timber. Abaca and copra

are the principal products though sugar, cacao, hemp, and rice are cultivated to some

extent. Among the important forest products are guttapercha for insulating cable wires

and almaciga for varnish. Basilan Island nearby is covered with forests, and lumber

mills are in operation. There are also plantations for the growing of rubber in this

island.

[106]

As a whole the interior of the province is not at present very accessible, and most

of the attractions center in the capital City of Zamboanga at the extreme end of the

peninsula, which is described on page 65.