The Project Gutenberg EBook of Exit From Asteroid 60, by D. L. James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Exit From Asteroid 60 Author: D. L. James Release Date: April 16, 2020 [EBook #61843] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EXIT FROM ASTEROID 60 *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Strange things were happening on Echo, weird

Martian satellite. But none stranger than

the two Earthlings who hurtled into the

star-lanes from its deep, hidden core.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Echo is naturally magnetic, probably more so than any other planetoid—and Neal Bormon cursed softly, just to relieve his feelings, as that magnetism gripped the small iron plates on the soles of the rough boots with which the Martians had provided him. Slavery—and in the twenty-ninth century! It was difficult to conceive of it, but it was all too painfully true. His hands, inside their air-tight gauntlets, wadded into fists; little knots of muscle bulged along his lean jaw, and he stared at the darkness around him as if realizing it for the first time. This gang had plenty of guts, to shanghai men from the Earth-Mars Transport Lines. They'd never get by with it.

And yet, they had—until now. First, Keith Calbur, and then himself. Of course, there had been others before Calbur, but not personal friends of Neal Bormon. Men just disappeared. And you could do that in the Martian spaceport of Quessel without arousing much comment—unless you were a high official. But when Calbur failed to show up in time for a return voyage to Earth, Bormon had taken up the search.

Vague clews had led him into that pleasure palace in Quessel—a joint frequented alike by human beings and Martians—a fantasmagoria of tinkling soul-lights; gossamer arms of frozen music that set your senses reeling when they floated near you; lyric forms that lived and danced and died like thoughts. Then someone had crushed a bead of reverie-gas, probably held in a Martian tentacle, under Bormon's nostrils, and now—here he was on Echo.

He gave an angry yank at the chain which was locked around his left wrist. The other end was fastened to a large metal basket partly filled with lumps of whitish-gray ore, and the basket bobbed and scraped along behind him as he advanced. Of the hundred or more Earthmen, prisoners here on Echo, only seven or eight were within sight of Bormon, visible as mere crawling spots of light; but he knew that each was provided with a basket and rock-pick similar to his own. As yet he had not identified anyone of them as Keith Calbur. Suddenly the metallic voice of a Martian guard sounded in Bormon's ears.

"Attention. One-seven-two. Your basket is not yet half filled, your oxygen tank is nearly empty. You will receive no more food or oxygen until you deliver your quota of ore. Get busy."

"To hell with you!" fumed Bormon—quite vainly, as he well knew, for the helmet of his space suit was not provided with voice-sending equipment. Nevertheless, after a swift glance at the oxygen gauge, he began to swing his rock-pick with renewed vigor, pausing now and then to toss the loosened lumps of ore into the latticed basket. On Earth, that huge container, filled with ore, would have weighed over a ton; here on Echo its weight was only a few pounds.

Neal Bormon had the average spaceman's dread of oxygen shortage. And so, working steadily, he at last had the huge basket filled with ore—almost pure rhodium—judging by the color and weight of the lumps. Nearby, a jagged gash of light on the almost black shoulder of Echo indicated the location of that tremendous chasm which cut two-thirds of the way through the small asteroid, and in which the Martians had installed their machine for consuming ore.

Locating this gash of light, Bormon set out toward it, dragging the basket of ore behind him over the rough, rocky surface.

The ultimate purpose of that gargantuan mechanism, and why this side of the planetoid apparently never turned toward the sun, were mysteries with which his mind struggled but could not fathom.

Presently, having reached the rim of the abyss, with only a narrow margin of oxygen left, he commenced the downward passage, his iron-shod boots clinging to the vertical wall of metallic rock, and as he advanced this magnetic attraction became ever more intense. The blaze of lights before him grew brighter and seemed to expand. Dimly, two hundred yards over his head, he could glimpse the opposite wall of the chasm like the opposing jaw of an enormous vise.

He joined the slow-moving stream of workers. They were filing past a guard and out on a narrow metal catwalk that seemed to be suspended—or rather poised—by thin rods in close proximity to a spacious disk which extended from wall to wall of the chasm. They moved in absolute silence. Even when tilted ore-baskets dumped a ton or more ore into the gaping orifice in the center of the disk, there was still no sound—for Echo, small and barren of native life, lacked even the suggestion of a sound-carrying atmosphere.

And that weird soundlessness of the action around him brought a giddy sense of unreality to Neal Bormon. Only the harsh, mechanical voice of the Martian guard, intoning orders with cold and impersonal precision, seemed actually real.

"Attention. One-seven-two. Dump your ore...."

These Earthmen were apparently known by numbers only. Bormon's own number—172—was on a thin metal stencil stretched across the outer surface of the glass vision plate of his helmet; he couldn't forget it.

He obeyed the Martian's order. Then he noticed that men with empty baskets were moving along a curved ramp, like a corkscrew, which led to a different level, whether above or below he could not possibly tell without a distinct mental effort.

He decided it was to a lower level as he moved onward, for the huge disk lost its circularity and became like the curving wall of a cylinder, or drum, down the outside of which the ramp twisted. Fresh ore was also being brought from this direction. And seeming to extend out indefinitely into blackness was a misty shaft, like the beam of a searchlight. Presently the ramp gave way to a tunnel-like passage.

Flexible metal-sheathed tubes dangled from the ceiling. These tubes were labeled: OXYGEN, WATER, NUTRIENT.

Bormon, patterning the actions of those he observed around him began to replenish his supply of these three essentials to life. His space suit was of conventional design, with flasks in front for water and nutrient fluid, and oxygen tank across the shoulders. By attaching the proper tubes and opening valves—except the oxygen inlet valve, which was automatic—he soon had his suit provisioned to capacity.

He had just finished this operation when someone touched his arm. He glanced up at the bulky, tall figure—an unmistakable form that even a month's sojourn on Echo had not been able to rob of a certain virility and youthful eclat.

For a moment they stared into each other's eyes through the vision plates of their helmets and Bormon was struck dumb by the change, the stark and utterly nerve-fagged hopelessness expressed on Keith Calbur's features.

Then Calbur tried to grin a welcome, and the effect was ghastly!

For a moment his helmet clicked into contact with Bormon's.

"Neal," he said, his voice sounding far away, "so they got you, too! We can't talk here.... I'm pretty well shot. Lived in this damn walking tent for ages. No sleep, not since they took me.... Some powder, drug, they put in the nutrient fluid—it's supposed to take the place of sleep—and you can't sleep! Only it doesn't.... You come along with me."

The darkness swallowed them up. Bormon had thrown his rock-pick into his empty basket. And now, by keeping one hand in contact with Calbur's basket, as it bobbed and jerked on ahead, he was able, even in the inky blackness, to keep from straying aside.

After seemingly interminable groping and stumbling, Calbur's light flashed on. They had entered a pocket in the rocks, Bormon realized, a small cavern whose walls would prevent the light from betraying their presence to the guard.

Calbur threw himself exhaustedly down, signifying that Bormon should do likewise, and with their helmets touching, a strange conversation ensued.

Bormon explained, as well as he was able, his presence there.

"When you didn't show up, Keith, in time to blast for Earth," he said, "all we could do was to report your absence to the space police. But they're swamped; too many disappearances lately. Moreover, they're trying to relocate that stream of meteoric matter which wrecked a freighter some time back. They know something is in the wind, but they'll never guess this! For weeks they've had the patrol ship, Alert, scouting around Mars. So, after making the run to Earth and back to Mars—I had to do that, you know—I got back in Quessel again and commenced to pry around, sort of inviting the same thing to happen to me that had happened to you—and here we are."

"We're here for keeps, looks like," answered Calbur grimly, his voice having lost part of that overtone of strained nerves. "A man doesn't last long, so the other prisoners say, two months at the most. These Marts use Earthmen because we're tougher, here at least, and last longer than Marts.... Hell, what wouldn't I give for a smoke!"

"But the purpose, Keith? What's the scheme?"

"I thought you knew. Just Marts with fighting ideas—a crowd backed by wealthy, middle-class Martians who call themselves Lords of Conquest. They're building ships, weapons. First, they're going to take over Mars from the present government, which is friendly to Earth, and then they're going to subdue Earth."

Calbur had switched off his light, as a matter of precaution, and his voice came to Bormon from a seemingly far distant point—a voice from out of the darkness, fraught with fantastic suggestion.

"Ships? You say they're building ships? Where?" Bormon asked, his own voice reverberating harshly within the confines of his helmet.

"In a cavern they've blasted out near the south magnetic pole of Mars. You know that's an immense, barren region—lifeless, cold—bordered on the north by impenetrable reed thickets. They need rhodium in large quantities for hull alloys and firing chambers. That's why they're mining it, here on Echo."

"They'll never get it to Mars," Bormon declared quickly. "Every freighter is checked and licensed by the joint governments of Earth and Mars."

"They won't?" Calbur laughed, distantly. "Listen, Neal—every crateful of ore that's dumped into their machine, here on Echo, gets to Mars within a few hours. And it isn't carried by ships, either!"

"You mean—?"

"I didn't get the answer, myself, until I'd been here for some time. You see, Echo is just a gob of metal—mostly magnetite, except for these granules of rhodium—forty miles in diameter, but far from round. Then there's that chasm, a mammoth crack that's gaped open, cutting the planetoid almost in half. The whole thing is magnetic—like a terrestrial lodestone—and there's a mighty potent field of force across that gap in the chasm. The walls are really poles of a bigger magnet than was ever built by Martians or human being. And of what does a big magnet remind you?"

After a moment of thought, Bormon replied, "Cyclotronic action."

There was a short silence, then Calbur resumed. "These Marts shoot the ore across space to the south magnetic pole of Mars. A ground crew gathers it up and transports it to their underground laboratories. As a prisoner explained it, it was simple; those old-time cyclotrons used to build up the velocity of particles, ions mostly, by whirling them in spiral orbits in a vacuum-enclosed magnetic field. Well, there's a vacuum all around Echo, and clear to Mars. By giving these lumps of ore a static charge, they act just like ions. When the stream of ore comes out of the machine, it passes through a magnetic lens which focuses it like a beam of light on Mars' south pole. And there you have it. Maybe you saw what looked like a streak of light shooting off through the chasm. That's the ore stream. It comes out on the day side of Echo, and so on to Mars. They aim it by turning the whole planetoid."

"Hm-m-m, I understand, now, why it's always dark here—they keep this side of Echo facing away from Mars and the sun."

"Right," said Calbur. "Now we'll have to move. These Marts are heartless. They'll let you die for lack of oxygen if you don't turn in baskets of ore regularly. But we'll meet here again."

"Just give me time to size things up," Bormon agreed. The effects of the reverie-gas was wearing off and he was beginning to feel thoroughly alive again and aware of the serious situation which confronted them. "Don't let it get you down, Keith," he added. "We'll find a way out."

But his words expressed a confidence that the passing of time did not justify.

Again and again he filled his ore-basket, dragged it to the hungry mouth of that prodigious mechanism in the abyss, and in return he received the essentials for continued life.

During this time he formed a better idea of conditions around him. Once he wandered far from the Martian's headquarters, so far that he nearly blinded himself in the raw sunlight that bombarded the day side of the tiny planetoid. Again, he was strangely comforted with the discovery of a small space ship anchored deep in the abyss although he was not permitted to go near it.

He soon found that nothing was to be expected of the horde of Earthmen who slaved like automatons over the few miles of Echo immediately adjacent to the chasm's rim. The accumulative effect of the drug seemed to render them almost insensible of existence.

But with Calbur, who had served for a shorter time, it was different.

"Keith, we've got to tackle one of the Mart guards," Bormon told him, during one of their conferences in the cave. "We'll take its ray-tubes, fight our way to that ship they've cached in the chasm below the cyclotron power plant, and blast away from here."

"How?" asked Calbur. "If you make a move toward one, it'll burn you down—I've seen it happen!"

"Listen, I've spent hours figuring this out. Suppose one of us were to stay here in this cave, helmet-light on, and near enough to the opening so that his light would show dimly on the outside. Wouldn't a Mart guard be sure to come along to investigate?"

"Yes, practically sure," agreed Calbur, but with no great interest. Hour by hour he was sinking closer to that animate coma which gripped the other Earthmen. "But what would that get you? If you lose too much time, you'll be cut off from rations."

"I know, but suppose also that one of us—I, for instance—was hiding in the rocks above the cave, with a big chunk of ore, ready to heave it down on the Mart?"

Calbur seemed to be thinking this over, and for a moment there was silence.

"When shall we try it?" he demanded suddenly, and there was a note of eagerness and hope in his voice. "It's simple enough. It might actually work."

"Right now! If we put it off, it'll soon be too late."

They discussed details, laying their plans carefully, Bormon prudently refraining any suggestion that this move was one born of sheer desperation on his part.

Everything settled, Calbur moved up near the opening, so that his helmet-light could be dimly seen from outside the cave. Bormon, dragging his ore-basket, climbed up in the rocks directly over the entrance, and presently found concealment that suited him. Near at hand he placed a loose chunk of rock which on Earth would have weighed perhaps eighty pounds. The trap was set.

He settled himself to wait. His own light was, of course, extinguished. Far off he could see crawling blobs of luminance as guards and human workers moved slowly over the surface of Echo. Otherwise stygian darkness surrounded him. But he had chosen a position which, he hoped, would not be revealed by the light of any Martian bent on investigating the cave.

There were, he had learned, actually less than a score of Martians here on Echo; about half of them stayed around that cyclotronic ore-hurler in the chasm. They depended on secrecy, and were in constant communication, by ether-wave, with spies not only on Earth and Mars but among the personnel of the space police itself. These spies were in a position to warn them to shut down operations in case the ore stream through space attracted notice and was in danger of being investigated. It was all being conducted with true Martian insidiousness.

Thus Bormon's thoughts were wandering when, at last, he became aware that a Martian guard was approaching. His cramped muscles suddenly grew tense. His heart began to pound; it was now or never—and he must not fail!

The Martian, reeling along rapidly on the mechanical legs attached to its space armor, appeared to suspect nothing. It approached amid a rosette of light which seemed to chase back the shadows into a surrounding black wall. It had evidently seen the gleam of Calbur's helmet-light, for it was heading directly toward the mouth of the cave above which Bormon crouched.

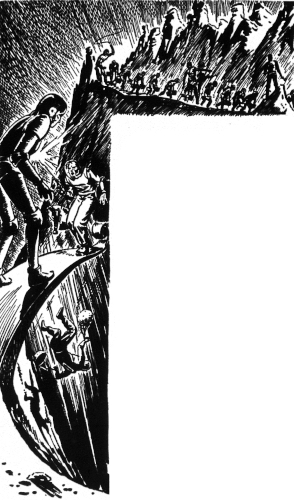

The moment for action arrived. Tense as a tirhco spring, Bormon leaped erect, hurled the jagged lump of rock down on the rounded dome of the Martian's armor. Then, without pausing to ascertain the result, he grasped the rim of his ore-basket and swinging it in a wide arc before him, leaped downward—

For a moment Martian, basket and Earthman were in a mad tangle. Bormon realized that the Martian had been toppled over, and that one of its ray-tubes was sending out a coruscating plume of fire as it ate into the rocks. The moment seemed propitious to Bormon!

Hands gripping and searching desperately, he found the oddly-shaped clamp that bound the two halves of the Martian's space armor together—and released it.

There was a hiss of escaping gas. Abruptly those metal handlers ceased to thrash about....

Bormon, thrilling with success, rose to his feet, turned off the Martian's ray-tube just as Calbur, delayed with having to drag his ore-basket, through the rather narrow opening, dashed into view.

There was no need for words. Bormon handed him a ray-tube.

Within a matter of seconds, each had burned through a link of the chain around his wrist. They were free from those accursed baskets! Calbur secreted the weapon in a pouch of his space suit, then swiftly they set to work, for their next move had been carefully planned.

Opening the armor fully, they began to remove the dead Martian, puffed up like a kernel of pop-corn by the sudden loss of its air pressure.

Having cleared the armor, Bormon climbed inside—space suit and all—folding up like a pocket knife so as to resemble somewhat the alien shape it was intended to hold, and tested the semi-automatic controls. Everything appeared to be in working order. Assuring himself of this as well as his knowledge of Martian mechanics would permit, he crawled out again to help Calbur.

Calbur was scrambling to collect ore. And under their combined efforts one of the baskets was presently filled—for the last time, Bormon fervently hoped!

Again he entered that strange conveyance, the Martian's armor, and after some experimental manipulation of the push-button controls, managed to get the thing upright on its jointed, metal legs and start it moving awkwardly in the direction of the chasm.

Behind him came Calbur, dragging the basket of ore—for lacking a disguise such as Bormon's, he must have some excuse for returning to the cabin, and he had wrapped the chain around his wrist to conceal the fact that it had been severed.

Bormon, in the narrow confines of his armor, disconnected the mechanical voder used by its deposed owner, for all Martians are voiceless.

His greatest fear was that one of the Martian guards would attempt to communicate with him. This would disclose the imposture immediately, since he would be unable to reply. For all Martian communication, even by ether-wave, is visual—the medium being a complicated series of symbols based on their ancient sign language, the waving of tentacles, which no human brain has ever fully understood. The means of producing these conventionalized symbols was a tiny keyboard, just below an oval, silvery screen, and as Bormon sent his odd conveyance stalking down the side of the chasm, toward that sweeping disk which he now knew to be formed by the ends of two cyclotronic D-chambers facing each other, he kept one eye on this silvery screen, but it remained blank.

He moved on down past the catwalk to the lower ramp. Here he must pass close to a Martian guard.

But this Martian seemed to give him no attention whatever.

Reaching a point opposite the ship, Bormon stepped from the ramp. Still that oval screen remained blank. No Martian was apparently paying enough attention to him to question his movements.

Again he caused the armor to advance slowly, picking his way along the rock surface. He reached the ship.

For a moment he was hidden behind the hull. One glance sent his hopes plunging utterly. Neither of the two fuel caps were clamped down, which could mean but one thing—the ship's tanks were empty!

It was a stunning blow. No wonder the Martians felt safe in leaving the ship practically unguarded. After a moment, anger began to mount above Bormon's disappointment. He would start to kill off Martians! If he and Calbur couldn't get away from Echo, then he'd see that at least some of these Marts didn't either. He might even wipe them all out. Calbur, too, had a ray-tube.

But what of Calbur? Quickly Bormon moved from behind the ship. Calbur was loitering on the ramp, ore-basket empty, evidently on the point of making a break to join him.

Frantically, Bormon focused the ether-wave on Calbur's helmet, hurling a warning.

"Stay where you are. It's a washout! No fuel...."

He began moving across the rocks toward the power-plant. That was the most likely spot to commence—more Marts close at hand. He'd take them by surprise.

Suddenly he was cold, calculating, purposeful. After all, there wasn't much chance of wiping them all out—and yet he might. He should strike at a vital point, cripple them, so as to give Calbur and the others a chance in case he only managed to kill a few before passing out of the picture.

A glittering neutrochrome helix on top of the power-plant gave him a suggestion. Why not destroy their communications, fix things so they couldn't call for help from Mars?

Abruptly he realized something was wrong. That silver oval six inches from his face was flashing a bewildering complexity of symbols. Simultaneously the Martian on the ramp began to move quickly and questioningly toward him.

The moment had arrived. Bormon swung the metal handler bearing the ray-tube into line and pressed the firing button....

Amid a splatter of coruscating sparks the Martian went down.

"Number one!" growled Bormon. Everything now depended on prompt action and luck—mostly luck! As quickly as possible he heeled around, aimed at the helix on the power-plant. It swayed slowly as that pale blue shaft ate into its supports, then drifted away.

He had lost sight of Calbur. Absolute silence still reigned, but on airless Echo that silence was portentous. Along the rim of the chasm he could see the glitter of Martian armor against the blackness of space. The alarm had been given. But for the moment he was more concerned with the imminent danger from those who tended the intricate controls in the power-plant, and the guard at the far end of the catwalk. This guard was protected by the catwalk itself and the stream of Earthmen slaves still moving uncomprehendingly along it. Bormon sent his space armor reeling forward, intent on seeking shelter behind the bulk of the power-plant.

He almost reached that protection. But suddenly sparks plumed around him, and his armor slumped forward—one leg missing. He fell, fortunately, just within the shelter of the power-plant.

Desperately he struggled to open the armor, so as to get the ray-tube in his own hand. But when he finally crawled forth it was to face three Martians grouped around him, their weapons—six in number—unwaveringly centered on him.

"Earthman," said the mechanical speaker coldly inside his helmet, "you have killed a Martian."

And then, with true Martian decisiveness and cruelty, they pronounced inhuman judgment on him.

"We in our kindness shall not immediately demand your life as forfeit. You shall wander unhindered over Echo, dying slowly, until your oxygen is gone. Do not ask for more; it is sealed from you. Do not again enter the chasm; it is death to you. Now go."

Hours later Bormon was indeed wandering, hopeless as a lost soul, over nighted Echo, awaiting the consummation of his sentence, which now seemed very near. Already his oxygen gauge indicated zero and he was face to face with the "dying slowly" process promised by the Martians—the terrible death of suffocation.

Now, as things began to seem vague and unreal around him, Bormon was drawing near that hidden cave where he and Calbur had often met for like a final flash of inspiration had come the thought that here, if anywhere, he would find Calbur.

It was strange, he reflected, how the life in a man forces him on and on, always hoping, to the very end. For now it seemed that the most important thing in the universe was to find Calbur.

He had husbanded the last of his oxygen to the utmost. But panting, now, for breath, he opened the valve a fraction of a turn and staggered on in the darkness. And suddenly, dimly as in a dream, he knew that at last he had found Calbur....

And Calbur was doing a queer thing. Gauntleted hands moving hastily in the chalky radiance cast by his helmet-light, he was tossing chunks of rhodium from his filled ore-basket—

Then their helmets clicked together, and he heard Calbur's voice, faint, urgent:

"Climb in the basket! I'll cover you with ore so they won't see you. I'll drag you in. Well get your tank filled—I swear it!"

The next instant, it seemed, Bormon felt himself being tumbled into the ore-basket. Chunks of ore began pressing down lightly on his body. Then the basket commenced to pitch and scrape over the rocks.

But his lungs were bursting! Could he last? He had to. He couldn't fool Calbur by passing out—not now. Something like destiny was working, and he'd have to see it through.

Something was tapping on his helmet. Bormon opened his eyes, and light was trickling down between the chunks of ore. No longer was there any scraping vibrations. Something, metallic, snakelike, was being pressed into his hand.

And then Bormon remembered. The oxygen tube! With a final rallying of forces only partly physical, he managed to stab the tube over the intake of his tank. The automatic valve clicked and a stream of pure delight swept into his lungs!

For a time he lay there, his body trembling with the exquisite torture of vitality reawakening, slowly closing the helmet-valve to balance the increase of pressure in the tank.

Suddenly that snakelike tube was jerked away from between the chunks of ore, and again the basket began a scraping advance.

Bormon's new lease on life brought its problems. What was about to happen? In a moment, now, Calbur would be ordered by the guard to dump his ore. They wouldn't have a chance, there on the catwalk. For Bormon's abrupt reappearance would bring swift extinction, probably to both.

The basket stopped. They had reached the ore-dump. Calbur's head and shoulders appeared. Behind the vision plate in his helmet there was a queer, set expression on his thin face. He thrust the ray-tube into Bormon's hands.

Bormon sprang erect, leaped from the basket. For a moment he stared around, locating the guard at the end of the catwalk. As yet the guard appeared not to have noticed anything unusual. But where was Calbur?

"Attention. One-six-nine. Dump your ore," ordered the guard, coldly, mechanically.

Something seemed to draw Bormon's eyes into focus on his own number stencil. One-six-nine, he read. Calbur's number! And then, suddenly, he realized the dreadful, admirable thing Keith Calbur had done....

For Calbur had leaped through the ore-chute, into the cyclotron's maelstromic heart! Despairing, he had chosen a way out. He had forfeited his life so that Bormon could take his place.

"Dump your ore," repeated the Martian guard, coldly.

"To hell with you!" snarled Bormon, and blasted with the tube.

He missed the Martian. Still weakened by the ordeal he had just passed through, and overwrought as an effect of Calbur's last despairing act, his aim was not true. Nevertheless, that coruscating shaft was fraught with far-reaching consequence. Passing three feet to the left of the Martian, it snapped two of the rods which braced the catwalk in position over the cyclotron drum. Thus released at the far end, the metal ribbon—for the catwalk was little more than that—curled and twisted like a tirhco spring, pitching Bormon, as from a catapult, straight along the path so recently chosen by Calbur.

Destiny had indeed provided them both with a strange exit from Echo, for in that split second Bormon realized that he was being hurled squarely into the gaping orifice of the cyclotron.

Far out in the vacuity between Echo and Mars, Captain Dunstan sat in his cabin aboard the Patrol Ship Alert—most powerful and, therefore, speediest craft possessed by the Earth-Mars Space Police.

On his desk lay two jagged pieces of ore, whitish-gray in color, which he had been examining.

His speculations were interrupted by the sudden bursting open of the cabin door. An officer, spruce in gray uniform and silver braid, entered hurriedly, his face flushed with excitement.

"Captain Dunstan, the most extraordinary thing has happened! We've just picked up two men—two men drifting with the meteoric stream, and in space suits—and they're alive!"

Captain Dunstan rose slowly. "Alive, and adrift in space? Then it's the first such occurrence in the history of space travel! Who are they?"

"I don't know, sir. So far we've got only one out of his suit. But I have reason to believe they're the men recently reported as missing by the E.M.T. Lines. He babbled something about Echo—that there's hell to pay on Echo. I imagine he means Asteroid No. 60. But—"

"Lead the way," said the captain, stepping quickly toward the doorway. "There's something mighty queer going on."

And so, by a lucky break, Neal Bormon found himself snatched from death and aboard the Alert, arriving there by a route as hazardous and strange as was ever experienced by spaceman.

And no less strange and unexpected came the knowledge of Keith Calbur's arrival there ahead of him.

Bormon, who was last to be drawn in by the grapple-ray and helped out of his space suit by the willing hands of the Alert's crew, was still capable of giving an understandable account of things; although Calbur, until the effects of the Martian drug wore off, would be likely to remain in his somewhat neurotic condition of bewilderment.

"These Marts," said Bormon, after a great deal of explaining on both sides, "don't know that you have discovered their stream of ore. They won't know it until their communications have been repaired."

Captain Dunstan nodded. "That explains why we were able, on this occasion, to approach the meteoric stream without its immediate disappearance. But I cannot understand," he confessed, "how two men could have passed through such an apparatus as you describe, and remain alive."

"Perhaps I can offer a possible explanation," said an officer whose insignia was that of Chief Electrobiologist. "If, as we suspect, this Martian invention is founded on the old and well-known cyclotronic principle, then we have nothing but reciprocal interaction of electric fields and magnetic fields. And these fields, as such, are entirely harmless to living organisms, just as harmless as gravitational fields. Moreover, any static charge carried by the bodies of these men would have been slowly dissipated through the grapple-ray with which they were drawn out of the ore stream."

This explanation appeared to satisfy the captain. "You say," he questioned, addressing Bormon, "that there are other men on Echo—Earthmen being used as slaves?"

"Yes, more than a hundred."

Captain Dunstan's mouth became a fighting, grim line. He gave several swift orders to his officers, who scattered immediately.

Somewhat later, Bormon found his way into the surgery where Calbur lay—not sleeping yet, but resting peacefully.

Assuring himself of this, Bormon, too, let his long frame slump down on a near-by cot—not to sleep, either, but to contemplate pleasantly the wiping-up process soon to take place on Echo, and elsewhere.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Exit From Asteroid 60, by D. L. James

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EXIT FROM ASTEROID 60 ***

***** This file should be named 61843-h.htm or 61843-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/1/8/4/61843/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.