“They saw the Equator making off, a mile or two away”

THE RUNAWAY

EQUATOR

And the Strange Adventures of a

Little Boy in Pursuit of It

BY

LILIAN BELL

AUTHOR OF “THE LOVE AFFAIRS OF AN OLD MAID,”

“THE EXPATRIATES,” “ABROAD WITH THE JIMMIES,”

“HOPE LORING,” “AT HOME WITH THE JARDINES,” ETC.

Illustrated by

PETER NEWELL

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1910, 1911, by

The Curtis Publishing Company

Copyright, 1911, by

Frederick A. Stokes Company

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign

languages, including the Scandinavian

TO

JIMMIE BELL, JUNIOR

SECOND INFANTRY, U.S.A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In which Billy Meets Nimbus | 3 |

| II. | The Enchanted Trolley Car | 13 |

| III. | The Equator Is Loose | 23 |

| IV. | The Equine Ox and the Evening Star | 37 |

| V. | In Pursuit | 47 |

| VI. | On the Passive Volcano | 55 |

| VII. | Jack Frost | 63 |

| VIII. | The Compass | 73 |

| IX. | The Trail of the Runaway | 83 |

| X. | Where Night Is Six Months Long | 93 |

| XI. | The End of the Chase | 105 |

| XII. | Across the Rainbow | 115 |

| “THEY SAW THE EQUATOR MAKING OFF A MILE OR TWO AWAY” | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page | |

| “WE’LL TAKE THIS SUNBEAM WITH US” | 6 |

| “NIMBUS FOLDED THE TRANSFER INTO A TINY WAND AND SAID: ‘THIS CAR FOR THE EQUATOR!’” | 10 |

| “BOTH THE PLUMBER’S APPRENTICES JUMPED HASTILY TO THE GROUND” | 14 |

| “STRAIGHT INTO A GREAT PILE OF SNOW WENT THE CAR” | 28 |

| “PRESENTLY THEY BEGAN TO CRY AS HARD AS EVER THEY COULD” | 32 |

| “NOW, SIR, WHERE IS THAT EQUATOR?” | 40 |

| “THERE SUDDENLY APPEARED SEVEN LITTLE CHAPS” | 48 |

| “WITH A GREAT CRACKLING NOISE THEY SHOT INTO THE VOID” | 50 |

| “BILLY TOOK A SHARP STICK AND POKED THE EQUATOR SMARTLY” | 60 |

| “SEATING HIMSELF ON THE EDGE OF THE CLIFF, HE SANG” | 66 |

| “CONFRONTING THE EQUINE OX WAS THE CONDUCTOR, WAVING HIS HANDS AND SHOUTING” | 76 |

| “THEY TIED THE TROLLEY ROPE TO HIS HORN AND SECURED HIM TO THE CAR” | 78 |

| “A METEOR DROPPED AMONG THEM” | 80 |

| “‘LISTEN,’ SAID THE EQUINE OX, AND THROWING BACK HIS HEAD, HE SANG” | 84 |

| “THE EQUINE OX CROWDED INTO THE REAR DOOR” | 90 |

THE RUNAWAY

EQUATOR

MOTHER had been helping Billy with his geography lesson, sitting in the garden on a lovely day early in spring, and showing Billy how the earth revolves on its axis. To illustrate this difficult matter and to make it interesting, she had taken a big yellow orange to represent the Earth and had used a stick of lemon candy for the Pole. She made the Equator out of a black rubber band such as you put around fat envelopes.

Then, when Billy said that he understood, Mother dug a hole in the orange and stuck the lemon stick in it and, handing it to Billy, said with a droll twinkle in her blue eyes, which always seemed to be laughing:

“Would you like to eat up the Earth through the North Pole?”

Now Billy had never before tasted the joys of an orange eaten through a stick of lemon candy; so when Mother, who had a trick of remembering nice things from her own[4] childhood, showed Billy how it was done, he settled down to a blissful half hour in which he meant to devour the whole earth.

It tasted so good that he rolled over on the short grass, under a lilac-bush in full bloom, and only took his lips from the North Pole long enough to tell his mother that it tasted “bully.”

“Well,” said his mother, standing up and shaking out her blue dress, “I must go now. Here is your geography. Don’t forget to bring it in when you come, and don’t lose the Equator off the Earth, even if you are eating it. I don’t know what would become of us if the Equator really should get away!”

Billy laughed aloud. It really was no trouble at all to understand things when Mother made them appear so funny.

He lay on his back looking up into the sky, which was just the color of his mother’s blue dress. White clouds, like mountains of white feathers which must be very soft to sleep on, were over his head.

A bee was buzzing lazily over the lavender blossoms of the lilacs. A soft wind was blowing. It was indeed very pleasant.

What if the bee should turn into a fairy!

“Why don’t you?” said Billy aloud.

The bee, being puzzled, scratched his head with his left hindfoot and answered:

[5]“Why don’t I what?”

“Why don’t you be one?”

“I am one bee!” answered the bee, striking a match on Billy’s orange and lighting a grapevine cigarette.

“Could you be a fairy?” asked Billy.

“I am always beeing things—flowers and honey—so of course I could bee a fairy. How do you know that I am not one? Look at me!”

Billy sat up and looked.

“Well, I never!” exclaimed Billy. “A minute ago I thought you were a bee!”

“I can bee anything I choose,” said the Fairy. “That’s why you thought I was a bee. Because I can bee!”

“Who are you now?” asked Billy.

“I am the Geography Fairy,” answered the stranger.

He held out his hand and then looked at it.

“It’s not raining yet,” he observed; “still——”

Without finishing his sentence he unfolded a pink parasol and tossed it into the air. It sailed away, slowly at first, then more rapidly as the light wind caught it and carried it out of sight beyond the lilac-bush.

“I won’t need it till it begins to rain,” he explained, “so they might as well have it.”

“Who?” gasped Billy.

“The sunbeams. If a sunbeam gets wet he’s done for. Haven’t you ever noticed that?”

Billy thought he had noticed something of the kind.[6] Anyway the sunbeams all disappeared directly it began to rain. But being just an ordinary little boy, he was much more interested in the conversation of the wonderful stranger than he was in sunbeams, and that is why he asked:

“What is your name, if you please?”

“My name is Nimbus and I live in the clouds with the other fairies. I was named after one of the clouds.”

“But,” objected Billy, “I don’t believe in fairies.”

“Very well,” said Nimbus briskly, “keep right on don’t believing. It doesn’t disturb me in the least.”

“And besides,” said Billy, “there couldn’t be such a thing as a Geography Fairy.”

“How do you know?” demanded Nimbus.

“Because,” said Billy, “I have never seen one.”

“Nonsense!” returned Nimbus. “Did you ever see a noise?”

“No,” Billy admitted, “I don’t think I ever did. At least I don’t remember ever having seen one.”

“Well, do you believe that there aren’t any noises?”

Billy had no reply that seemed suitable, and so he said nothing.

Apparently not caring whether he got an answer or not, Nimbus leaped lightly from the lilac blossom and, picking up an irregular sunbeam that filtered through the bush, he set it carefully on edge against the brim of Billy’s hat.

“We’ll take this sunbeam with us”

[7]“They get tired lying flat on their backs so much,” he said. “We’ll take this one with us when we go. When we’re hungry we’ll eat it.”

“But we’re not going anywhere,” said Billy. “At least I am not. I’ve got to go into the house and put the toys away in a few minutes.”

“Tut! tut!” said Nimbus. “Doesn’t the proverb say ‘Never do anything to-day you can just as well put off until to-morrow’? Let’s enchant a trolley car and go look after the Equator. I ought to be there now. That’s my job, looking after the Equator. I’ve left the Equine Ox there, but he has such a habit of getting indigestion in one of his four stomachs, and sometimes in all of them, that he is very inattentive to business.”

“Indigestion in four stomachs must be terribly distressing,” said Billy. “But what is an Equine Ox?”

“You surely see one twice a year,” said Nimbus. “But they are always around. They have to be somewhere.”

“I suppose they do,” said Billy, “but what are they?”

“Their names are Vernal and Autumnal. Here’s a poem I wrote about them once. My friends say I am conceited about my poetry, but I’m not. I don’t think it is as good as it really is.”

“That,” said Nimbus, “will give you an excellent idea of the Equine Ox. Now let us enchant that trolley car and be off about our business.”

“Pooh!” said Billy, “you can’t enchant a trolley car.”

“There you go again,” said Nimbus, “never believing in things. Bring me a trolley car and I’ll show you whether or not I can enchant it.”

“I can’t bring you a trolley car,” said Billy. “You’ll have to hail one on the street if you want one. Anyway they don’t go to the Equator; they only go to town.”

“We’ll see where they go,” returned Nimbus. “If I were going alone I’d go on a cloud, but I don’t suppose you could sit on a cloud, could you?”

He regarded Billy doubtfully.

[9]“I’m sure I couldn’t,” said Billy. “Besides, what’s the need of going at all?”

“Oh, I really must go! A foolish Spring Tide broke one of the tropics the other day, and if the other gets broken there will be nothing to hold the Equator down but the meridians, and you know they’re very fragile.”

Billy didn’t know that, but he nodded intelligently. It is always best to pretend to know more about geography than you really do.

“We’ll be back in time for dinner,” continued Nimbus; “that is, if I don’t have to fasten up the tides again.”

“Why,” said Billy, “you don’t mean to say you have to fasten the tides?”

“Certainly!” replied Nimbus. “You know the tides are always trying to put out the Moon, and they go chasing around the Earth after her night and day. Of course the shore stops them after a while and drives them back, and that’s what makes them high and low. They’re high when they run up and try to wash over the shore, and low when the shore drives them back again. But to keep them from going too far we tie them down with meridians. That’s why they call them tides. Each one is tied, don’t you see?”

“Gracious!” exclaimed Billy. “I hope they can’t get untied and put the Moon out.”

“Oh, they won’t,” Nimbus assured him, “while I’m watching them! Sometimes they sneak up on her out of the ocean in little drops that we call mist, but the Sun[10] always catches them at it, and sends them scurrying down in rain again.”

“I almost believe I’ll go,” said Billy, “if you’re sure we can be back in time.”

“Not a doubt of it,” said Nimbus; “I’ll send you back on a meteor if I have to stay.”

Billy excused himself for a minute and ran into the house to tell his mother, but she was nowhere to be found. So he wrote a note in which he explained that he had gone away for a little while with the Geography Fairy. Returning to the garden, he found that Nimbus had now grown to be as large as a middle-sized baby. He was strolling across the lawn on his way to the front gate.

Billy trudged along by his side, and soon they were at the street corner awaiting the coming of a big red trolley car, which Billy hailed at Nimbus’s suggestion.

When the two got in the conductor looked at the queer little stranger in amazement.

But Nimbus only nodded at him coldly, leaped up on the seat and began digging into his pocket, from which he presently pulled a huge blue transfer.

This he held out when the conductor came for the fare.

“That ain’t no good,” said the conductor.

For reply Nimbus folded the transfer up into a tiny wand, touched the conductor on the cap with it and said:

“This car for the Equator. Passengers desiring transfers for the Arctic Circle or the North Pole will kindly mention it before we get to Cuba.”

“Nimbus folded the transfer into a tiny wand and said:

‘This car for the Equator!’”

OF COURSE such an announcement as that made a great commotion in the trolley car. The other passengers, a thin deacon, two plumber’s apprentices and a burglar, wanted to get off immediately.

“I was going back to the shop to get the tools,” said one of the plumber’s apprentices.

“I was on my way to a horse trade,” explained the deacon.

“And I,” said the burglar, “was just looking about for a nice easy house to rob. They don’t have any houses at the Equator, so I would have absolutely nothing to do.”

“Tut! tut!” said the conductor peevishly. “Keep your seats, gents. There ain’t no such a place as the Equator on this line. You’re on the wrong car, young chaps,” he added, turning to Billy and Nimbus.

Billy was troubled at this. Could it be that Nimbus really couldn’t enchant the trolley car after all?

But the Fairy only smiled as the car, which had started away suddenly, came to a stop, as if it had run into something.

“I thought we wouldn’t get past it,” he said.

[14]“Get past what?” inquired Billy and the plumber’s apprentices in a breath.

“That imaginary line,” said Nimbus. “I drew it across the track.”

“But,” said Billy, “no imaginary line really goes anywhere except the Equator.”

“Neither will the trolley car until I let it,” replied Nimbus. “So they are in the same fix.”

The motorman now came into the car.

“Not enough juice,” he growled. “She turns all right, but she don’t get nowhere.”

“Try her again,” advised the conductor anxiously. He was looking at Nimbus and Billy with suspicion. “You kids ain’t been soapin’ the track, have you?” he inquired suddenly.

“Oh, no, sir!” said Billy. “I’m not allowed to do that.”

The motorman again turned on the power, but although the wheels hummed and whirred on the track, not an inch forward did the car go.

“There’s something wrong,” he said, “but I don’t know what it is. She turns all right, and she acts all right, but she don’t go ahead none.”

“She won’t,” said Nimbus, “till these people get off. It would be a shame to take them to the Equator.”

“Certainly it would,” said the deacon. “I for one am going to get off.”

“Me, too,” said the burglar.

“Both the plumber’s apprentices jumped hastily to the ground”

[15]And both of them did.

“It’s all right with us,” said the plumber’s apprentices, settling back in their seats. “Our time will go on just the same.”

“Well, it ain’t with me,” said the motorman. “I’m going to see what’s stopping her.”

He went to the rear door and was about to swing off the steps when he uttered a cry of alarm.

“Great rabbits!” he shouted. “She’s risin’ off’m the track!”

At this both the plumber’s apprentices ran to the platform and jumped hastily to the ground.

The motorman and conductor hurried to the front platform, but when they reached it the car had risen thirty feet in the air and was sailing merrily through space.

The conductor reeled back into the car and sank breathless on a seat. The motorman followed him.

“What kind of a way to do is this?” demanded the conductor of Nimbus. “And me with a wife and five children.”

“There is no danger at all,” said Nimbus soothingly. “We’ll have to come down again, you know. Everything does, that goes up.”

The conductor had got a little over his fright, and was looking out of the window.

“I don’t know where we’re going, Tommy,” he said to the[16] motorman, “but it does look as if we was on our way, don’t it?”

“It’s an outrage!” said the motorman, “and I’ve a good mind to chuck this little feller overboard. It’s all his doings.”

But Nimbus paid no attention to him at all.

“You see,” he said to Billy, “that a trolley car can be enchanted if you go at it right. I could enchant the conductor and motorman if I wanted to. I think I’d turn the motorman into a bull.”

The motorman grew pale at this.

“Now, don’t do nothing like that,” he said. “I like this flying business, honest I do.”

“Very well,” said Nimbus, “but I think you had better go out on the platform and look for stars. We may be running into one any time.”

The motorman was glad to return to his post, and the conductor arose and walked unsteadily to the rear platform, where he held fast to the dashboard rail and gazed with open-mouthed wonder at the scene below.

“We’ll soon be coming to the Dog Star,” Nimbus told Billy. “His name is Sirius, but he isn’t. He’s almost eight million years old, but he still behaves like a Puppy Star at the snow-making season. He worries the Snow Fairies half to death.”

“What are Snow Fairies?” asked Billy.

[17]“They are the people that make the snow. Didn’t you ever hear the proverb, ‘Make snow while the moon shines’?”

Billy wasn’t quite sure. He had heard one very much like that, though, about hay, and he wondered if they made snow in fields and left it out to dry in the moonshine.

“Yes,” said Nimbus, although Billy had not spoken, “it is very much the same. The snowflakes grow on the little stalks that shoot up from the clouds, and the Snow Fairies harvest them and dry them in the moonlight. Then they sift it down on the land and sea, whenever Jack Frost says the little boys and girls are tired of nutting and making autumn-leaf bonfires, and want to coast and throw snowballs.”

“Do they make hail that way, too?” asked Billy.

“Oh! gracious, no. They break the hail off the rain clouds with their hammers, and it freezes on the way down. They soon tire of that, though, so they never keep it up long. That is why you hear people say ‘Hail and Farewell.’ You have to say good-by to a hailstorm almost before you’ve had time to say hello to it.”

“I think it is very ill-mannered of the Dog Star to worry them,” said Billy.

“Oh, Dog Stars have no manners. That is very well shown in the poem I wrote about the Dog Star. Did you ever happen to hear it?”

“No,” said Billy. “I never did.”

[18]“Well,” said Nimbus, “as nearly as I can remember it runs something like this:

“You see,” continued Nimbus, “the Dog Star cares absolutely nothing for manners. He even barks at O’Taurus.”

“And who,” inquired Billy, “is O’Taurus?”

“He’s the Irish Bull,” said Nimbus. “I’ll tell you more about him later. I’ve got to go to meet this Meteor now.”

Billy had noticed that for some time it had been getting[19] brighter and brighter, although the Sun had hidden himself behind a great wall of blue-black clouds. Now he looked through the front windows and saw a great star sweeping rapidly down on them, swishing a long tail behind him.

“Is—is it a comet?” he asked in affright, observing that the motorman rushed into the car, slamming the door after him.

“Comet nothing!” said Nimbus. “It’s only a fourth- class Meteor with a message for me. They’re the A.D.T. boys up here, and he’s probably brought some word from the Equine Ox.”

The Meteor came alongside and Billy read in gold letters across his glowing cap the words:

PLANETARY MESSENGER SERVICE

No. 7,622,451

“My!” he exclaimed, “there are a lot of them, aren’t there?”

“Seven million nine hundred thousand six hundred and three,” said Nimbus. “What have you got, boy?”

“Message, sir,” said the Meteor briskly, taking off his cap and extracting a blue envelope.

Nimbus took it and ran his eye over it hastily.

“Here’s a pretty kettle of fish,” he said, handing the paper to Billy.

[20]This is what Billy read as he held the paper in his trembling fingers:

“Accidentally went to sleep and the Spring Tide broke the other tropic. Equator trying to get away, and think I can’t hold him long. Please come or send help as soon as possible.

“Regretfully, Vernal E. Ox.”

So! The Equator was trying to do the very thing Mother told Billy not to let him do! He was trying to slip off the earth by way of the South Pole!

“BOTHER that Equine Ox,” said Nimbus. “I might have known he’d do something like that, and just before procession week, too.”

“Procession week?” said Billy wonderingly.

“Yes, the week of the procession of the Equine Oxes. The Sun and the Moon and their oldest daughter, the Evening Star, were coming down to see it, and Jack Frost and Aurora Borealis ought to be there now. And that miserable Equine Ox has gone and spoiled it all. He isn’t fit for anything but a barbecue.”

“What are you going to do?” asked Billy, while the conductor and the motorman gaped in a dazed silence.

“Do? Why, fix it, of course. I only hope we can get there before he breaks away altogether. It would be a beautiful state of affairs to have an Equator charging up and down the world, wouldn’t it?”

“I think it would be fun,” ventured Billy.

“Oh, certainly!” said Nimbus. “When you played under the trees in your front yard, do you think it would be fun to have cocoanuts drop on you instead of acorns? Instead[24] of rabbits and chipmunks in the woods, do you think it would be fun to see lions and tigers and boa-constrictors and laughing hyenas, to say nothing of hippopotamuses with teeth like banisters? Yes, it would be real jolly now, wouldn’t it?”

Billy saw that Nimbus was seriously disturbed and he kept silent.

The Meteor, who had entered the car unasked and taken a seat on the floor, now got up and began to shoot violently from one door to another, sometimes zigzagging so that he bumped the windows. His blazing tail trailed after him, and once or twice Billy had to draw back quickly to keep his face from a severe switching.

The conductor and the motorman were very much annoyed by these antics, and at last the conductor said:

“What’s the matter with him, anyway? Why don’t he sit still?”

“He can’t sit still,” said Nimbus. “A meteor is a shooting star and ever so often he has to shoot.”

“Shootin’ is against the rules,” growled the motorman. “No shootin’ allowed in any cars of this company.”

“He isn’t shooting aloud. He’s shooting to himself,” said Nimbus. “I’ll send him back to the Equator as soon as I compose a message that is strong enough to tell the Equine Ox what I think of him.”

Billy had been looking out of the window. A long way off he noticed a row of enormous signs, each with curious[25] characters on it, all outlined in bright green and blue stars.

“Signs of the Zodiac,” said the Meteor, coming to a sudden stop and looking over Billy’s shoulder. “‘Keep off the sky,’ and ‘No loose dogs allowed,’ and such like. The Aerolites have just turned ’em on. They come right after the twilight.”

“I—I don’t think I understand,” said Billy.

“Neither do I,” said the Meteor, “but I’ll explain it in a minute. I’ve got a few shots in me now that have got to go off.”

He leaped to his feet and began to dart backward and forward in the car till Nimbus, who was writing on a pad of paper, became irritated and slammed the car-door on the Meteor’s tail.

“Isn’t he peevish!” said the Meteor, sinking down at Billy’s side. “But as I was saying about the Aerolites, every night the Sun goes down, as you know, and it would be pitch dark until the Moon and the Stars came up if it wasn’t for them.

“One of them keeps watch until he sees the Sun starting to slide behind a mountain or into the sea, and then he tells the others, and they all hurry around and light the twilights. When they have them all lit there is enough light to see by till the Moon and the Stars get out of bed for the night. After that they can light the Signs of the Zodiac. They get paid for that. Lighting the twilights[26] they have to do for their board and lodging and motive power.”

Nimbus left off writing. “I think that will do,” he said, handing the pad to Billy.

Billy read:

“V. E. Ox, Equator.

“Of all the good-for-nothing, idle, dull-witted, stupid, feather-brained idiots I have met in twelve million years you are easily the worst. Send that Spring Tide to bed for a week. Get the other Equine Ox and a regiment of elephants and sit on the Equator till I get there. If he tries to get away duck him in the ocean. My only regret is that you have but four stomachs instead of ninety-four to get indigestion in.

“Yours disgustedly, Nimbus.”

The Meteor took the paper from Billy’s hand, Nimbus released the tail from the door and he shot forth into the night.

Billy began to be very much distressed about the darkness, remembering his promise to his mother to be home for dinner. Nimbus, noticing his troubled face and feeling better now that he had unburdened himself of his opinion of the Equine Ox, sat beside him and said cheerfully:

“Never mind, Billy, it’s always half dark up here. We’re out of the air, you know, and we have to have air to see the light through, just as your mother has to have opera-glasses to see the play through. We’ll be home in time for dinner. Never fear.”

[27]At this assurance Billy felt much better, and became very eager to see the great fight that he knew would take place when they got down to the Equator and took part in the effort to keep him from escaping.

But the motorman and the conductor were in no such cheerful mood. They sat apart in a corner and talked in whispers; and Billy, listening although he did not mean to, soon learned that they were talking about the Snow Fairies.

“It’s them,” said the conductor, “that spills snow all over the tracks and ties up the lines in winter.”

“Sure it is!” said the motorman. “Let’s get off and fix ’em.”

Billy glanced out of the window. There, right before his eyes, he saw a great number of little people, clad in white uniforms, raking huge masses of what seemed to be white flowers on the upper side of a cloud. Through the dim half-light he watched them working away, with rakes and pitchforks, some of them piling the white flakes into great stacks, while others pulled long rows of them to the edge of the cloud and pushed them over the side.

Billy remembered that it was summer when he left home and he wondered how it happened that snow-making was going on; but following with his eyes the flakes that whirled downward he saw a long chain of mountains far below. He knew, of course, that snow fell on mountains, even in summer time, so he understood.

[28]“I tell you what I’ll do,” the motorman was saying; “I’ll go out and back her sideways and we’ll run through ’em. That’ll knock ’em all off the cloud, and we won’t have no more snow.”

“Great idea,” said the conductor. “We’ll get ’em all at one lick.”

Billy looked anxiously at Nimbus, who overheard, but only chuckled. “Let ’em try it,” he said, “and see what happens.”

Nimbus joined Billy at the window, and the motorman and the conductor, seeing that the Fairy’s back was turned, got up very quietly and went out on the front platform.

The motorman put his lever on the controller and, looking around carefully to make sure that he was not observed, reversed the power.

The car trembled, stopped, then began to go backward with a sidelong motion that took it right into the snow cloud.

Instantly the air grew cold, and the wind howled around the trolley pole and rattled the windows.

Straight into a great pile of snow went the car, and the Snow Fairies, looking up, saw it coming and skipped away in every direction.

There was a shock, snow flew in showers, then the car buried itself in a great white pile up to the window tops and stopped stock still.

Stamping and pawing the snow out of their eyes and[29] mouths, the motorman and conductor came back into the car.

“Pleasant weather, gentlemen,” said Nimbus. “Looks a little like snow, however. Suppose you go out now and clear the track. You’re used to it.”

Angry, but too much ashamed of themselves to show their feelings, the motorman and the conductor got shovels from under the seats and went out to clear away a path for the car.

“It always pays best to let Nature take care of herself, as the boy said who sat on the volcano,” Nimbus observed.

“It will be a dreadful delay, though, and we are in such a hurry to get to the Equator,” said Billy.

“Oh, no, there will be no delay at all! The Cloud is going right in our direction just as fast as we were. We’ll warm up, however, for it’s a trifle cold,” said Nimbus. And taking out the sunbeam he had brought with him from the lilac bush, he hit a piece out of it and handed it to Billy.

“Eat it,” he said. “Nothing so stimulating in cold weather as a sunbeam. We’ll just sit here and wait for an answer to my telegram. And you can act acquainted with the sky people.”

Billy looked out of the window into the sky. Was it true, he wondered, that the Sun and Moon were really sky people?

“What’s the matter?” asked Nimbus.

[30]“I was just wondering if the Stars are all really people,” said Billy.

“Really people!” said Nimbus. “Well I should say they are. And all the Clouds are, too. You see that bunch over there? Well, that is Mrs. Pink-Cloud and Mrs. White-Cloud and Mrs. Pearl-Cloud and Mrs. Mackerel-Cloud and Mrs. Yellow-Cloud sitting together and sewing on party dresses for their children to go to the Star children’s birthday party. It’s warm over there where they are.”

“Oh!” said Billy. “Are they all named?”

“Named! Of course they are! And every Star, too. But nobody can remember them but their own mother, Mrs. Moon. Even their father, Mr. Sun, gets confused sometimes and mixes the boys’ names with the girls’.”

“Are the Clouds people, too?” asked Billy wonderingly.

“Just as much people as you are,” answered Nimbus seriously. “Old General Gray-Cloud and old General Thunder-Cloud are great fighters and have awful battles. You can hear them down on the Earth sometimes. It sounds like thunder and looks like lightning from where you live, but from where we live—Oh, my!”

“Dear me,” said Billy, “how very interesting! And do the mothers teach their children to behave the way our mothers do on the Earth, or are they allowed to do as they please in the sky?”

“Well, you do show your ignorance!” said Nimbus, with such severity that Billy quite blushed for himself. “Why[31] let me tell you what I saw only yesterday when I was under the lilac bush waiting for you.”

“Did you know about me before I saw you?” asked Billy, much flattered.

“Why, certainly I did. I saw you having such a stupid time with a geography lesson which I knew I could make so easy for you that I said to myself: ‘I’ll just wait until I have him all to myself and then I’ll show him!’”

“That was very kind of you,” said Billy, “and I am sure that I shall never forget anything I have seen.”

“That’s just the way with me,” said Nimbus; “so what I saw of the Cloud children I will tell to you, and then it will be just the same as if you had seen it.”

“So it will,” said Billy, who by this time had got to have great faith in the Geography Fairy.

“What do you suppose makes it rain?” asked Nimbus suddenly.

Billy thought intently for a moment. He knew he had heard something about clouds and mist and heat and cold, but for the life of him he couldn’t remember when anybody asked him. That is what makes examinations so hard. You know, but you can’t remember.

“Ah, ha!” said Nimbus. “You can’t think, can you? Well, I’ll tell you, and you’ll never forget this reason. The other day, when their mothers were all sitting and sewing, the Cloud children——”

[32]“What are their names?” asked Billy.

“Well, there happened to be Pinkie Pink-Cloud and Goldie Gold-Cloud and Pearlie Pearl-Cloud. They asked their mothers if they could float over Central Park and watch the Earth children at play. Their mothers said yes, so away they went. At first it was great fun to watch, for it was Mayday and all the children were marching about in their pretty white dresses while nursemaids and fräuleins and mademoiselles by the dozen, and a few mothers, were looking on.

“Then Pinkie and Goldie and Pearlie began to play tag among themselves, nor was it very long before Pinkie said that Goldie did not tag her when she said she did, and Pearlie took sides; so in one moment those little sunny faces grew black with anger and presently they began to cry as hard as ever they could.”

“Well?” said Billy, as Nimbus paused.

“Well,” repeated the Fairy, “don’t you see? Their tears were rain!”

“Oh!” said Billy.

“The next thing that happened was that their mothers looked up from their sewing and saw the dark spot over the park, where, a few minutes ago, it had all been bright and sunny. They knew what had happened, for in April and May the Cloud children are easily upset and cry if you poke your finger at them. So they floated over to the park and, instead of asking the children what the matter was,[33] as most mothers would have done, Mrs. Gold-Cloud told the children to look down at the park.”

“And what did they see?” asked Billy, who never before had thought of looking at the Earth children through the eyes of the clouds.

“Why, the rain spoiling all the pretty white dresses and the children all stopping their play and rushing about for shelter.”

“I know,” said Billy. “I was there myself.”

“Were you?” said Nimbus. “Then you know what happened.”

“I only know it stopped raining,” said Billy.

“But don’t you know why?” asked Nimbus.

Billy shook his head.

“Because Mrs. Gold-Cloud told the children how tears and black looks on their faces always spoiled the pleasure of somebody else, and how smiles and sweet looks and lots of love in the heart brings happiness. When she said this, the Cloud children dried their tears on their mothers’ cloud handkerchiefs and began to smile, and when Pinkie and Goldie kissed each other, the whole sky brightened up. So everything got sunshiny again, and of course the rain stopped as soon as the tears were dried, so in five minutes the little Earth children were running about again as happy as lambs. And the sight of their happiness made the Cloud children glad they had not been so selfish as to quarrel long.”

[34]“They must be nice children,” said Billy thoughtfully. “That story sounds the way my mother tells things.”

“When you go back, you can tell the story to her,” said Nimbus.

“Thank you for telling me,” said Billy politely. “It is a very nice story and I sha’n’t forget it. I’ll have lots of things to tell when I get back. What are you going to do about the Equator?”

“Hello!” The last exclamation was directed at the Meteor, who suddenly appeared through the snow bank and, panting for breath, handed Nimbus a message which Billy read over his shoulder.

The message read:

“Glad to know you are coming, and thanks for your kind words. Equator is loose.

“Respectfully, Equine Ox.”

“I EXPECTED it,” said Nimbus with a sigh. “I might have known the Equine Ox couldn’t hold him.”

“I don’t suppose it is any use to go to the Equator now, is it?” asked Billy. “I don’t see how we can go there if we don’t know where it is.”

“Well, we know where it was, and there’s where we’ll go,” snapped Nimbus. “I have a little speech to make to the Equine Ox that he ought to hear.”

The motorman and the conductor had now got a nice, clean path shoveled through the snow, so they boarded the car and it soon slid off the snow cloud and sped on again.

Presently Billy, looking downward, saw that they were coming closer to the Earth all the time. And what a different Earth it was from any he had ever seen outside of a geography! A curving coast-line laced with filmy surf lay below him, and on the hills that rose from it he could see countless palm trees, each with a little tuft at the top like the long blades of blue grass about the edge of the garden at home, well beyond the reach of the lawn mower.

“Gracious! We must be near where the Equator was,”[38] he exclaimed. “It looks like a conservatory outdoors down there.”

“It’s not,” said Nimbus. “It’s the grandstand. That’s where the procession of the Equine Oxen was to be held.”

“Of course it won’t be held now?” timidly suggested Billy.

“It will, if I have anything to do with it. Just because we never did have a procession without an Equator is no reason we shouldn’t have one. Besides, now that there’s no Equator to watch, unless they parade, those good-for-nothing creatures won’t earn their cuds.”

The car by this time was grating on a hillside, and soon brought up between a couple of slender palm trees.

“I’ve been expecting you,” said a voice—a sad voice that seemed to come from directly above the car.

Looking out of the car window, Billy saw a bright light among the branches of the tree—a light that surrounded like a halo the figure of a very pretty girl.

“Why,” said Nimbus briskly, lifting his hat, “it’s the Evening Star.”

“Yes,” said the Evening Star, “it is I. I came to complain about the Equine Ox. He’s very disconsolate, and he’s singing continually. I wish you’d stop him.”

Billy was very much surprised to find the Evening Star all alone. He was about to ask Nimbus why it was when she said:

“You see, Papa—he’s the Sun—never comes out at[39] night; and Mrs. Moon, who’s my mamma, isn’t up yet, so I had to come alone. Is there anything else you’d like to know, little boy?”

Billy was very much abashed at thus having a question answered before he had asked it, and especially by a young lady whom he had never met. But there was one thing he wanted to know very much, so he said politely:

“Yes, thank you. I should like to know why the Equine Ox sings when he is unhappy.”

“Oh, that’s so people can tell he’s the Equine OX,” said the Evening Star. “He always does things backward. When he’s very angry he rolls on the ground and roars with laughter. When he’s pleased about anything he weeps bitterly, and when he’s unhappy he sings.”

“There he is now,” said Nimbus, who had been listening intently. “Don’t you hear him?”

Billy heard something that first sounded like a long-drawn-out moo, but which he soon recognized as a very familiar air.

“Come on,” said Nimbus.

“Us, too?” inquired the motorman and conductor. “We don’t want to be left alone in these here foreign parts.”

“Yes,” said Nimbus, “come ahead!” and he led the way down a winding pathway that opened through the trees.

The singing grew louder and louder as they proceeded, and shortly they came out into a little open space overgrown[40] with flowers and surrounded by a very dense tropical growth. In the center of it stood a creature that looked a little like an ox, a little like a horse, and very much like a map of the solar system. Billy and the street-car men stopped at a signal from Nimbus. The Equine OX was singing.

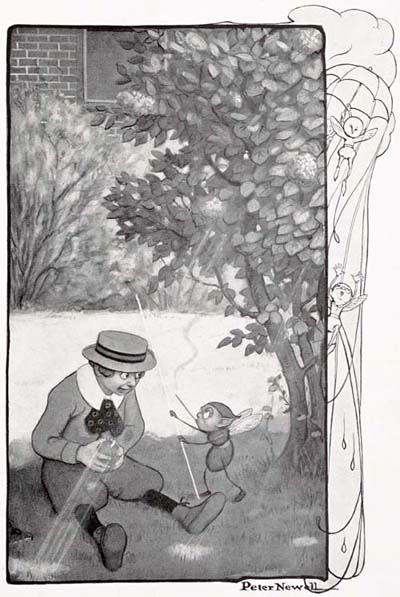

“Now, Sir, where is that Equator?”

Directly the song was finished Nimbus strode up to the Equine Ox and, shaking his fist angrily at him, demanded:

“Now, sir, where is that Equator?”

“That’s the question,” said the Equine Ox; “where is he? Who knows the answer?” Then seeing Billy, he added: “Maybe you do!”

“Why, no, sir,” replied Billy in confusion. “I don’t. Not at all.”

“Pay no attention to him,” said Nimbus. “He’s merely trying to avert suspicion from himself.” Then turning to the Equine Ox, he proceeded: “Tell us how he got away. Be quick, there is no time to lose.”

“Oh, yes, there is,” said the Equine Ox; “any quantity of it! I lose a great deal every day and hope to lose a great deal more. As for finding time, now that is another——”

“How did the Equator get away?” said Nimbus sternly.

“Well, you see, it was this way. Night fell on the tropics and the tropics broke.”

“Ho, ho!” exclaimed the conductor. “That’s a joke. Ho, ho!”

[42]“What is the gentleman angry about?” uneasily asked the Equine Ox, who always laughed when he was angry.

“Nothing,” said Nimbus; “go ahead with your explanation.”

“Then a few waves broke,” continued the Equine Ox, “and then day broke and, well—what could the Equator do but break, too?”

“Did you sit on it?” asked Billy eagerly.

The Equine Ox regarded him gravely.

“Did you ever sit on an Equator?” he asked.

“Why, no,” said Billy, embarrassed. “I didn’t.”

“Neither did I,” said the Equine Ox. “Far be it from me to sit on an Equator when it is going anywhere.”

“So it’s completely gone, has it?” asked Nimbus. “Which way did it go?”

“Shall I answer both of those questions first?” said the Equine Ox.

“I’ll answer the last,” volunteered the Evening Star. “It went south and slipped off the South Pole. I saw it.”

Nimbus fell back with a groan and Billy ran forward to catch him.

The motorman and conductor gathered around. “Jab him in the ribs with the crank handle,” suggested the conductor. “It’s the way we do when they faints on the car.”

But Nimbus revived before this became necessary.

“It gave me such a start,” he said.

[43]“The Equator’s got a better one,” said the Equine Ox.

“Everything’s easy once you get a start,” commented the motorman.

Nimbus was now himself, and a very energetic little self he was. First he placed the conductor and the motorman in charge of the Equine Ox, with orders not to let him out of their sight.

“He must be here to-morrow,” he said, “or the procession cannot go on, and if the procession does not go on it will always be summer and the sea will dry up.”

The motorman and the conductor were scarcely eager to undertake the charge, but something in Nimbus’s manner convinced them that it was necessary, so they consented.

“You,” said Nimbus to the Evening Star, “will please go and tell your father that the Equator is off the Earth and that I will try to catch him.”

“And you,” he said to Billy, “come with me. As soon as the Equator is off the Earth, he will shrink up to the size of a barrel hoop, and the meanness in his disposition condensed into that small space will make a perfect fiend of him. He is liable to drop right down on us this very minute and burn us into a cinder before you can say ‘Jack Robinson.’ He gets so hot when he’s angry that he has been known to set an iceberg on fire. By the way,” he added, “how quickly can you say ‘Jack Robinson’?”

“Jackrobinson!” said Billy.

[44]“I thought so!” said Nimbus. “You’d have been dry ashes before you got to a-c-k.”

Hardly had he left off speaking when a Meteor dashed in with a message from the Dog Star.

“Equator coming back to Earth vowing vengeance against Nimbus and Evening Star,” it said.

“FIRST of all,” said Nimbus, “we must find the Rays. Then we’ll go down to the Meteor farm and put all the Meteors who are off watch or on part time, to work doing scout duty.”

“Who are the Rays?” asked Billy.

“They are the Sun’s private messengers. They do all his regular work for him, such as making things grow, and arranging the weather, and building the bridges——”

“Bridges?” Billy inquired.

“Yes, rainbow bridges. How could we fairies get over the ocean if it wasn’t for them?”

“You might go on enchanted trolley cars,” suggested Billy.

“Yes, we might, if trolley cars grew on trees in jungles like monkeys, but they don’t.”

Billy thought it best to make no more suggestions.

“The Rays,” continued Nimbus, “are named Violet, Indigo, Blue, Green, Yellow, Orange and Red. Get them all together and they make a beautiful, clear, white light, and we’ll need such a light to find the Equator.”

[48]There was a rustling of the trees behind them and a sad voice called out: “I wish you’d take me with you. I’m afraid to stay alone.”

Billy looked quickly around and saw the Evening Star standing at a little distance, looking very pretty indeed in the soft light that seemed to sift out of her white frock.

“Oh, nonsense!” said Nimbus. “We’ve men’s work here. You don’t want to go anyway!”

Two bright tears stood in the Evening Star’s eyes and glistened in the glow that surrounded her. Nimbus clapped his hands in delight.

“There you are, you fellows!” he shouted; “come out of that.”

“Who?” cried Billy.

“The Rays—all of them. Don’t you see them hiding in those teardrops? Come, come. No more delay! I’ve important work for you.”

As he spoke, there suddenly appeared before him seven lively little chaps, each clad from head to foot in his own prismatic color, and all dancing excitedly about the ground.

“Go tell the old man that the Equator has got away,” commanded Nimbus. “And then come back here and make us a searchlight. If he isn’t back here where he belongs by to-morrow there’s no telling what will happen.”

Without a word the Rays suddenly united in a brilliant[49] shaft of white light and whisked away over the treetops.

As they vanished Billy thought he heard a sob, and glancing about, saw the Evening Star sitting in the branches of a low palm and crying as if her heart would break.

“Oh, I’m afraid! I’m afraid!” she wailed. “If the Equator should come back and find me here when you’re gone he’ll turn me into a Comet; I just know he will!”

Nimbus’s face grew serious at this.

“There is danger of that,” he said. “Yes, he would be just about contemptible enough to do that very thing.”

“But how could he?” inquired Billy, his bewilderment steadily increasing.

“Easiest thing in the world. He has only to set fire to her hair, and it would stream out behind her in a fan of flame. Then she’d be so frightened that she’d go wandering off through space and become a Comet.”

“Then,” said Billy, “I think we had better take Miss Evening Star with us, don’t you? Unless her father, Mr. Sun, can look after her.”

Nimbus frowned at Billy impatiently.

“My dear boy,” he said, “don’t you know that the Sun never does any night work of any kind? Besides, just now he’s busy on the other side of the world. Yes, we’ll take her with us.”

[50]So Nimbus and the Evening Star and Billy went off to the yard where the Meteors off duty and on part time were assembled.

The inclosure, which was walled in by four fogs, was full of them, jumping hurdles, playing marbles, or racing around after each other.

So busy were they at their sport that it was not until Nimbus had shouted himself hoarse that they paid the slightest attention to him.

At last, however, one of them heard him and shot over to see what he wanted.

“I don’t believe,” said Nimbus, “that you Meteors could hear the rings of Saturn if they rang all at once. Did you know that the Equator had escaped?”

“Goodness, no!” said the Meteor, and instantly shot about among his fellows spreading the dreadful news.

They left off playing immediately, and all lined up before Nimbus for orders.

“You must go find the Equator,” said the Fairy authoritatively. “The Rays have gone to notify the Sun. Ten of you will come with us. The other six million will scatter about the universe and look for him. Let me know the instant you see him, and stop him if he starts to come back to the Earth.”

“Yes, sir,” said the Meteors in a breath. With a great crackling noise they shot away into the void, each taking a different direction so that their going looked like a splendid shower of rockets on the night of the Fourth of July.

“With a great crackling noise they shot into the void”

[51]“I suppose,” said Nimbus, “that the next thing to do is to build a tower so we can see what is going on in the sky.”

“We have nothing to build it of,” said Billy.

“We could make it of Moonbeams if there were any Moon,” replied Nimbus.

“But there isn’t,” said the Evening Star, “so we’d better find a hill to climb.”

“I saw a beautiful hill as we were coming here,” said Billy. “It had a white top, and stood out ever so high over the others.”

“That was a volcano,” said Nimbus. “It’ll be just the place for us.”

“Let’s be starting, then,” said Billy.

So the whole party set out through the trees for the volcano, and in an hour or two were standing on a great lava field looking up at the dark sky, which seemed fairly alive with fiery-tailed meteors hurrying here, there and everywhere on their search for the Equator.

Billy had just settled himself with his back against a comfortable boulder when he noticed right over his head an object which resembled a great, luminous doughnut. “I wonder what that is,” he said, pointing upward.

The Evening Star, quite exhausted with the tramp up the mountain, had been sitting with her bright face in her[52] hands. At Billy’s words she glanced up, and a terrified scream brought Nimbus to his feet.

“There he is!” shouted Nimbus excitedly. “He’s coming this way, and we can never capture him.”

“There who is?” asked Billy.

“The Equator!” said Nimbus.

OF COURSE there was but one thing to do, and that was to escape as quickly as possible. Even Nimbus, powerful as he was, couldn’t control a runaway Equator single-handed, and if the Evening Star were ever turned into a comet it would take years of patient effort on the part of her parents to turn her back into a Star again.

Nimbus looked swiftly about him for a second, and then he said: “Fortunately, this is not an active volcano, so we’ll slip into the crater.”

He led the way toward a cavelike opening right in the summit of the mountain—an opening which led downward diagonally, so that it afforded ample shelter.

Billy hesitated. He had heard about volcanoes, and the thought of bearding it in its crater was very terrifying.

“Don’t be afraid,” said Nimbus; “this is a passive volcano.”

That reassured Billy, and when he was safe inside the crater he asked what a passive volcano was.

“It’s one that isn’t active. There are two kinds of verbs[56] and two kinds of volcanoes—active and passive. The fire in this one has been banked, so it’s perfectly safe.”

Billy was still a little uneasy, and he was by no means cheered by a sound of dull rumbling that came up out of the depths of the crater.

He had little time to worry about this new danger, however, for just then the crater became filled with terrific heat, and its dark recesses were illumined by a brilliant glare.

Billy’s eyes were dazzled at first, then right above him he made out the circular form of the Equator staring blankly down at him.

“Oh, I am lost!” cried the Evening Star, and with a series of leaps she disappeared down the crater.

“The goose, she’ll be burned to death!” said Nimbus, and started after her.

There was a sound of falling gravel, a sharp patter of footsteps, and then silence.

Billy knew that it would be foolish to follow, so he quietly waited for something to happen.

The Equator, meanwhile, was getting a little more accustomed to the darkness. As he peered about he muttered to himself, and Billy caught the words: “I hope she hasn’t got away. There’s no one left but the Equine Ox, and you couldn’t turn him into a Comet any more than you could turn him out of a pasture.”

[57]“You ought not to turn anybody into a Comet,” said Billy. “It isn’t polite.”

The Equator started violently.

“Who are you?” he demanded, scowling at Billy.

“My name is Billy,” said the little boy, “and I am a friend of the Evening Star.”

“Do you think you could be turned into a Comet, Billy?” asked the Equator solicitously.

“I-I hope not,” faltered Billy. “I never tried, though.”

“I’m afraid you couldn’t,” grumbled the Equator. “Perhaps you can tell me where I can find the Evening Star.”

“No,” said Billy decidedly. “I will not.”

“Oh, come now, don’t be rude. I won’t turn her into a very big Comet, you know.”

“I don’t care,” said Billy. “I shall not tell you where she is, and I think you ought to be ashamed of yourself.”

“I was driven to it,” said the Equator; “when the Geographers made me, they wanted to be sure to have enough of me to go around, and I’ve been going around ever since. It got so monotonous after a while that I simply had to get into mischief or explode.”

“Was that why you escaped?” asked Billy.

“Yes; the Equine Ox went to sleep and I broke a meridian and got away. It was quite oxidental, my escaping; I mean accidental.”

[58]“It cannot be very nice, being an Equator,” said Billy thoughtfully; “but it would be far worse to be a Comet.”

“Oh, I don’t know!” said the Equator. “Comets only have to get to a certain place once in two or three hundred years, while an Equator has to be in one place always. I’m very tired,” he said suddenly. “What do you usually do when you’re tired?”

“I sleep,” said Billy.

“Indeed!” said the Equator; “how interesting. How is it done?”

“Why,” exclaimed Billy eagerly, “you lie down somewhere, then you close your eyes, then you think of sheep jumping through a fence and try to count them until you fall asleep.”

“But I can’t think of any sheep jumping through a fence. I never saw a sheep, nor a fence. Do you suppose it would do just as well to count hippopotamuses jumping through a swamp?”

“Perhaps,” said Billy doubtfully, “although I never tried it.”

To his great joy the Equator settled down on the summit of the volcano and closed his eyes. He breathed hard and regularly for a little, and then, as one eye opened, he said: “What do you do when the third and seventh and eleventh hippopotamus is a rhinoceros? Count him, too?”

“Certainly,” said Billy, and again the Equator closed his eyes.

[59]Presently he opened them again. “Look here,” he exclaimed, “I’ve counted all the hippopotamuses and rhinoceroses there are. Now what do I do?”

“Begin on the camels and lions and tigers,” said Billy.

“And when they’re counted?”

“Count the ants,” said Billy with a sudden inspiration, and the Equator troubled him no more.

Billy was delighted. The Equator’s lips moved rapidly for some minutes, and Billy slipped quietly down into the crater to find Nimbus and the Evening Star to tell them to hurry and make their escape.

He wandered about blindly for some little time, then stopped bewildered.

The crater forked in many directions. It seemed hopeless to explore any one of them because his friends might have taken another.

At last he determined to make sure that when they did come back they would have no trouble in escaping.

Returning to the mouth of the crater he saw the Equator still fast asleep.

Billy’s hands went to his pockets, and when they came out they brought a quantity of fish-line, which he always carried for emergencies.

He deftly tied the line to a huge stone, making sure that the knot Was fast, and then very cautiously slipped it through the center of the Equator, making a loose knot, but one that would be reasonably sure to hold him. He[60] doubled and redoubled the string, and when the job was done stood back and surveyed it with considerable pride.

Then, assured that the Equator was at his mercy, he began to hope for him to wake up so that he could enjoy his triumph. He even coughed once or twice in the hope of awakening his captive, but the Equator was very tired and it seemed impossible to arouse him.

At last, unable longer to restrain his impulse, Billy took a sharp stick and poked the Equator smartly once, twice, three times.

The sleeper’s eyes opened, and he tried to yawn and stretch, but the fish-line restrained him. He looked about wrathfully and espied Billy.

Instantly his dull glowing skin became white hot with rage, and the line melted away like straw.

The Equator sprang to his feet, his whole circular body shining like the iron which the blacksmith has just taken from the forge.

“You shall pay for this, young man!” he cried. “I may not be able to turn you into a Comet, but I can maroon you on the Polar Star, which will be quite as satisfactory.”

As Billy stood petrified with fear the Equator swept down upon him.

“Billy took a sharp stick and poked the Equator smartly”

IF YOU’VE never had an Equator sweep down on you, of course you cannot understand in the least how frightened Billy was. Even the Equine Ox grew gray with fear when the Equator was angry, and the Equine Ox was seldom disturbed by anything but indigestion in his four stomachs.

As for Billy, he had never been really frightened before, excepting the time he fell into a tar barrel, and looking back upon it, that experience now seemed a very tame affair.

He shrank back and waited for the worst. To his surprise it did not happen. For just as the Equator was rushing toward him, just as he was trying to say Jack Robinson, and say it so quickly that his life would be spared an instant or two before he was turned to ashes, he heard a voice say:

“Hello, ’Quate! Loose, I see!”

Instantly the Equator, who had been white-hot, turned a sort of sickly yellow, then faded to dull red, and finally to a bluish green. In the meantime he had stopped sweeping[64] down on Billy and was motionless, save for a tremor that ran through his circular frame.

Between Billy and the Equator stood a wiry little fellow dressed all in fluffy white, with a white cap to match. In his hand he held what seemed to be a very straight icicle, which glittered with all the hues of the rainbow.

The Equator glowered upon the newcomer for some seconds before he growled huskily: “Jack Frost!”

“Perfectly correct,” said the stranger cheerfully. “I always did admire a good memory for names.”

“What are you doing here?” demanded the Equator sulkily, and Billy saw to his joy that he was now in no further danger of attack.

“Nothing that I am ashamed of,” returned Jack Frost, “which is more, it seems to me, than you can say.”

The Equator stared at Billy. “I—I—” he faltered.

“What was he doing?” asked Jack Frost, turning suddenly to Billy. Before the little boy could answer the Equator with a flop or two rose in the air, circled once or twice over the trees and sailed rapidly away.

“Bad lot!” commented Jack Frost. “Never take him seriously.”

“But he was going to burn me up,” said Billy.

“Umph!” said Jack Frost. “That’s different. Let’s go and see about it.”

Billy thought he had seen all of the Equator he cared to, but Jack Frost insisted on watching that ill-tempered[65] creature, and so Billy followed him to the very top of the volcano where they could get a clear view of the horizon.

They saw the Equator making off a mile or two away, and Jack Frost, taking Billy by the arm, started down the mountain at a brisk trot. As they hurried along Jack Frost said:

“I suppose you have heard of me.”

“Oh, yes,” said Billy. “I have, many times.”

“I’m not so cold as I’m painted,” said Jack Frost.

“I’m sure you are not,” replied Billy respectfully.

“No,” said Jack Frost, “I really am not a bad fellow. Your father probably holds it against me because I freeze the water pipes sometimes, but think how the plumber’s poor little children love me for it.”

“That’s true,” said Billy.

“Sometimes,” continued Jack Frost, “I pinch little boys’ fingers, but that is only to remind them that they forget to ask their mothers if they can go skating.”

“I only did that once,” said Billy, reddening.

“Again,” said Jack Frost, “I nip flowers. I do that to warn them to go back into the ground, because winter is coming.”

“You ought to do it,” said Billy. “I hope they don’t object.”

“They do, though. People often object to things that are good for them, like going to bed early, and washing their hands and geography.”

[66]“Oh, I love geography now,” protested Billy.

“Oh, I’m delighted to hear it. Do you like songs?”

“Yes, indeed. The Equine Ox knows a beautiful one about the Equator.”

“I cannot imagine a beautiful song about the Equator,” said Jack Frost. “See what you think of mine.” And seating himself on the edge of the cliff they had been skirting, with his heels hanging over space, he sang:

THE SONG OF JACK FROST

“And seating himself on the edge of the cliff, he sang”

“I think that is a very pretty song,” said Billy.

“Thank you,” said Jack Frost; “but what has become of the Equator in the meantime?”

Billy looked in every direction, but no sign of the Equator was to be seen.

“I was listening to your song,” he said. “I forgot to keep looking.”

“You are a very nice little boy,” said Jack Frost, patting[68] Billy on the head, “but we have just got to find that Equator. There is no telling what he may be doing.”

“I know what he will try to do,” said Billy.

“That’s something. What is it?”

“Catch Miss Evening Star and make a Comet out of her.”

“Great goodness! Why didn’t you say that before?”

“There wasn’t time,” explained Billy.

“There is always time,” said Jack Frost coldly. “Time is everywhere. The supply is inexhaustible.”

“I’m sorry,” said Billy.

“Never mind,” said Jack Frost kindly. “I dare say it will turn out all right, like the farmer’s wagon that met the automobile. Anyway, here comes the Geography Fairy. He ought to have some tidings.”

Looking over the edge of the cliff, Billy saw Nimbus approaching. He explained afterward that the crater which he and the Evening Star had followed, led right through the volcano and out of the cliff at the bottom.

Jack Frost hailed him, and Nimbus climbed up, bidding his train of Meteors wait until he returned.

He and Jack Frost shook hands cordially, and Nimbus inquired:

“Have either of you seen anything of the Evening Star? I lost track of her when we got out of the crater.”

“Gracious!” said Billy, “I thought she was with you.”

[69]“So she was,” said Nimbus, “but she said she thought she’d like to fly once more, and sailed off to pay the Moon a visit.”

Jack Frost looked up quickly.

“That’s where the Equator’s gone, then,” he said.

“Has the Equator left the top of the volcano?” asked Nimbus excitedly.

“He has,” said Jack Frost. “He was just about to destroy this little boy when I stopped him. He’s afraid of me.”

“More than of any one else in the whole world,” said Nimbus. “But where do you suppose he is now?”

“I don’t suppose,” said Jack Frost; “I can only suspect.”

“And what do you suspect?”

“That he’s trailing the Evening Star, and if he finds her——”

“But he must not find her,” cried Nimbus.

“No,” said Jack Frost, “he must not.”

Out of the darkness above them shone a bright speck that grew larger and larger. As it drew nearer Billy saw that it was a Meteor, a new Meteor which he had never seen before.

“Hey, there!” shouted Nimbus, who had seen him the same moment Billy did; “any message for me?”

“Yes,” puffed the Meteor, who was not within easy talking distance. “Miss Evening Star is being chased by the[70] Equator, and has only got about a thousand miles’ start.”

“Which way are they going?” asked Nimbus and Jack Frost in a breath.

“Gee whiz!” said the Meteor, “I forgot to ask.”

“STRANGE that you fellows never forget to ask for your meals,” said Jack Frost tartly. “Your memory never fails you there.”

“Let us not waste time scolding them,” said Nimbus. “The important thing is to find where the Equator and the Evening Star have gone.”

“Very true,” said Jack Frost. “We’ll establish headquarters immediately, and send out scouts.”

Then he led the way to a little clump of palms which was at the foot of a hill just below them.

The Meteors, like a great flock of fireflies, followed along in their wake, and when they stopped they lined up for orders.

“Now,” said Nimbus, addressing them, “how many points of the compass are there?”

“It depends entirely on the compass,” said one of the Meteors.

“He’s right,” said Jack Frost. “A large compass would have more points than a small one. There’s more room on it.”

[74]“I can box the compass,” chirruped another Meteor proudly.

“I can box ears,” snapped Nimbus peevishly.

Here Jack Frost broke in.

“Tell off a thousand Meteors,” he said, “to count all the points on the largest compass, and then order a scout to go in the direction pointed by each point. That ought to get them.”

“Good,” declared Nimbus. “Go to work, you fellows, and carry out orders. The first one who discovers them, notify Aurora Borealis, and she’ll flash the signal down to us.”

The Meteors, who were always active when there was work to be done, shot forth on their errands.

“How long do you suppose it will be before the Equator can catch the Evening Star?” asked Billy.

“It all depends on whether or not they are both going in the same direction,” replied Jack Frost.

Billy smiled. “Of course,” he said, “if they were going in opposite directions he never would catch her.”

“Wrong,” said Jack Frost. “Supposing I started for the South Pole and you started for the North Pole, and we both kept on going in the same direction after we got there, what would happen?”

Billy thought a minute. “Oh, I see!” he cried; “we’d meet on the opposite side of the earth.”

“We would,” said Jack Frost, “if we didn’t stop on[75] the way. The Equator has probably gone in the opposite direction, intending to meet the Evening Star on the other side of the world. That would surprise her.”

“In that case,” said Nimbus, “Jack Frost and I had better start off in opposite directions and see which gets to the other side of the world first. The one who does can put a stop to this chase.”

“But we don’t know just which part of the other side they’re going to meet on,” objected Jack Frost.

“We can take a chance,” said Nimbus. “That’s what the Meteors will have to do, and we can beat them, because we have no tails to drag after us.”

“What shall I do?” said Billy.

“You can stay here and get him if he happens to pass,” said Nimbus.

Billy was a little troubled about this, but he was not the boy to admit that he was frightened, and, though his mouth trembled a trifle and he winked a little more rapidly than usual, he kept a brave face as his two friends each called a cloud out of the sky and sailed away upon it.

He had stood there but a few minutes when he heard the tinkling of a bell a little distance away. At first it rang slowly and at long intervals, then faster and faster, till at length it sounded like the triangle the man played in one corner of the orchestra in the theater at home.

Thinking there could be no harm in finding out where the sound came from, as the Equator was as little likely[76] to alight in one place as another, he listened very carefully, then proceeded slowly toward the tinkling sound.

Soon he came out into the very clearing where the trolley car had reached the earth, and there stood the trolley car with the face of the Equine Ox protruding from the front door and wearing a very unhappy expression.

Confronting the Equine Ox was the conductor, who was waving his hands and shouting, while the motorman was stooping over, a little way off, gathering up a smooth round stone about the size of an egg.

Meanwhile the tinkle of the bell sounded continuously, and the Equine Ox wriggled and writhed as if very much displeased with his imprisonment.

The motorman being nearest to him, Billy addressed him:

“What are you going to do with that stone?” he inquired.

“Throw it at the Ox,” replied the motorman.

“Oh, don’t do that,” pleaded Billy. “You might hurt him. And he isn’t doing anything bad, I’m sure.”

“He isn’t, isn’t he?” shouted the motorman. “Ain’t he lashing his tail?”

“What of that?” asked Billy. “All animals lash their tails except bears and saddle horses and fox-hunters, which haven’t any tails to lash.”

“Confronting the Equine Ox was the conductor, waving his hand and shouting”

“But his tail is caught in the bell rope,” said the motorman, hurling the stone at the Equine Ox. The stone broke a window, and although it did not reach its target, it[77] annoyed the creature so that he struggled more frantically than before, and the bell jingled furiously.

“Stop,” cried the conductor excitedly. “It’s getting too expensive for me.”

“Expensive!” said Billy in amazement.

“Yes, expensive. Every time he wiggles his tail that way he rings up a fare, and he’s rung up more than thirty-seven dollars’ worth already. I’ve counted ’em all.”

Billy understood why the motorman and the conductor were so worried. The tail of the Ox had become entangled in the rope that led to the fare register, and every tinkle of the bell meant a fare recorded.

At first he was shocked to think of this wasteful extravagance, but then he recollected that as the car was not on a regular run the fares couldn’t really be counted against the motorman and the conductor.

They were not at all certain of this when he explained it to them.

“We’re going back, ain’t we?” asked the conductor.

“Oh, yes,” said Billy, “I’m sure we are.”

“Well, when we run the car into the barn they’ll charge me with these fares,” said the conductor. “The car will have been away so long that they’ll be disgusted if it has not earned any money.”

“I tell you,” said Billy; “when Nimbus comes back I’ll get him to enchant the register so it will only charge up the[78] fares you have really collected. That will make it all right.”

This appeased the motorman and the conductor, and in answer to Billy’s questions they explained how the Equine Ox got into the car.

When they were left alone with him he had behaved very badly, rolling on the ground and laughing very heartily, which proved, as they had been told by Nimbus, that he was furiously angry.

Then he began to sing, and at last he actually started to run away.

But they prevented this by tying the trolley rope tightly to his horn and securing him to the car, and then, fearing that the rope might break, they hit upon a stratagem.

They talked eagerly about the comforts and coolness of the inside of the car, until the curiosity of the Equine Ox outran his discretion and he insisted upon going in.

Knowing that he was governed by contraries, they tried to prevent his doing so. This, as they expected, made him all the more determined, and he forced his way past them into the car.

But once inside he found it impossible to get out, and then it was that he began the lashing of his tail, which had resulted in the ringing up of so many fares.

Billy agreed with the motorman and the conductor that the best place for the Equine Ox was in the trolley car,[79] for if he tried too hard to escape they had only to shut the door to keep him there.

So Billy sat down and told the trolley men everything that had happened since he left them, and they became as excited as he was about the chances of the Evening Star’s escape from the Equator.

“I wish I had the Equator in reach of my crank handle,” said the motorman.

“I wish,” said Billy, “that the Evening Star would come past here right now. We’d get Nimbus to enchant the trolley car again, and away we’d go back home with her.”

“Sure,” said the conductor. “We could use her for a headlight on the way home.”

They were all busily discussing what could be done to secure the Evening Star against the Equator when they had her in Billy’s home when a light shone above the trees and soon a Meteor dropped among them.

“I just met the Equator going west-nor’west,” he said. “Where’s Nimbus?”

“In that case,” bellowed the Equine Ox, “I’ll go sou’-sou’east,” and he walked calmly away in that direction, tearing out the forward end of the trolley car as he went.

“Soon a Meteor dropped among them”

WITH wild cries the conductor and the motorman ran after the Equine Ox, but although he appeared to be walking, he went at a tremendous speed, and soon they were compelled to give up the chase.

“Oh! Oh!” wailed Billy, who was terribly distressed at the escape of the Equine Ox, “I wish there was something I could do. But I am so small that I am absolutely useless around here.”

There was a cracking of branches close at hand, and to Billy’s astonishment and delight the Equine Ox reappeared.

“Do you think it is unlucky to be small, Billy?” he inquired.

The motorman and the conductor started forward, but the Equine Ox lowered his horns.

“Never mind that now,” he said to them. “I will give you due notice of my next movements, and on the whole I don’t think I will go at all. I don’t think the Equator will come this way, at all events.”

[84]The conductor and the motorman still advanced, but Billy said:

“I think the Equine Ox is speaking the truth. His eyes look honest.”

“My eyes are honest,” said the Equine Ox. “They never deceived me in my life. But as I was saying, why are you so sorry that you’re small?”

“Because,” said Billy, “I can’t be of any help when things happen.”

“Listen,” said the Equine Ox, and throwing back his head he sang:

THE MELANCHOLY STAR

“Listen, said the Equine Ox, and throwing back his head, he sang”

“I’ll try not to be sorry any more,” said Billy, when the song was finished.

“That’s right,” said the Equine Ox; “and now, if the gentlemen don’t mind, I’d like to go back into the trolley car. It fitted me perfectly, and it was such fun ringing that bell.”

“The trolley car’s broke,” said the conductor. “And if it wasn’t I wouldn’t take a chance on having you ring up any more fares.”

[86]“Very well,” said the Equine Ox, “then we might as well sit quietly and await the reports of the Meteors. They’ll be coming in very soon now.”

But it was not a Meteor who first arrived. It was Jack Frost and Nimbus, coming in from opposite directions almost at the same time. Both had been clear around the world, they said, and neither had seen a sign of the Equator or the Evening Star.

“I suppose,” said Billy, when this dismal report was received, “that we ought to notify the Sun.”

“I can’t notify him,” said Jack Frost. “He and I are utter strangers.”

“I sent the Rays to notify him,” said Nimbus. “But I don’t think it will do any good. He can only travel so fast anyway, not more than a million miles a minute, and that would not do any good.”

“What is there to do, then?” inquired Billy disconsolately.

Hardly were the words out of his mouth when a Meteor came dashing in among them.

“Any news?” asked Jack Frost.

“Lots of it,” said the Meteor. “News is happening every minute.”

“He means any news of the Evening Star or the Equator,” said Nimbus.

“No,” said the Meteor. “In fact I had forgotten all about them in the excitement.”

[87]“What excitement?” demanded Nimbus.

“Why,” said the Meteor, “the most astonishing things are happening. In Chicago grapefruits are growing on Wabash Avenue, monkeys are swarming up the Tribune Building on Madison Street, and they are raising tobacco and watermelons on Drexel Boulevard.”

“Gracious,” said Jack Frost, “and this is the middle of January! What can that mean?”

“Great news,” sang out a voice overhead, and another Meteor settled in among them.

“Snow has all melted in Duluth,” he said, “and there is an unprecedented sale of palmleaf fans all through that part of the country.”

Before any one could express surprise at this astonishing information a third Meteor and a fourth alighted.

“It is ninety degrees in the shade in Winnipeg,” said the third Meteor, “and they are picking cocoanuts in Quebec. The baseball season has opened in Iceland.”

“Hotter still in Norway,” said the fourth Meteor, who had just arrived; “oldest inhabitant never remembers such sultry weather. Eskimos are now wearing mosquito nets instead of furs, and they’re catching crocodiles in the Arctic Ocean. The icebergs have begun to boil.”

“This won’t do!” cried Jack Frost excitedly. “All the work that I’ve been at for centuries is being undone. I’ll soon have to organize a syndicate to attend to my business if this keeps up. Whatever can have happened?”

[88]Another Meteor came in just then with still more tidings.

“Great schools of whales are passing Cape Nome,” he said, “all going north. They’re picking strawberries off the tundras there, and they are advertising hot springs for rheumatism in a glacier.”

Nimbus, who had been sitting with knitted brows, suddenly leaped to his feet, and slapped the conductor on the back with such violence that that gentleman fell forward against the Equine Ox.

“I know what it is,” shouted Nimbus. “The Equator is up there. That’s what’s making all this trouble!”

“Then far be it from me to stay here,” said Jack Frost, preparing to start at once. “I’m not going to have all my good icebergs and glaciers melted like ice cream. It took me countless centuries to make some of them.”

“Oh, never mind your old icebergs and glaciers,” said Nimbus. “The point is that we’ve located the Equator and we can stop him before he catches the Evening Star. He can only thaw a radius of a few miles at one time, now that he’s shrunk so, so you don’t need to worry at all about his undoing your work.”

“Well, anyway, we must go up there,” said Jack Frost.

“We certainly must,” said Nimbus, “and as soon as possible. I expect Aurora Borealis will be reporting him at any time now.”

At that exact moment the sky lighted up with pink[89] splendor that waved and flickered and danced over the heavens.

“There she is now,” cried Nimbus. “Come, let us be off!”

“Please,” said Billy, who was intensely excited, “may I go, too? I should dearly love to help catch him.”

“Why, yes, I guess so,” said Nimbus. “I’ll enchant the trolley car again and we’ll all go in that.”

The trolley car had been very badly damaged by the Equine Ox, but Nimbus merely tapped it with his wand and it became whole again. The motorman regarded him open-mouthed.

“Wouldn’t he be a wonder in a repair shop?” he exclaimed.

“I guess she’ll hold together now,” said Nimbus. “Come on, Jack Frost; come on, Billy,” and he led the way into the car.

The conductor and the motorman took their places, and the Equine Ox at the last moment crowded into the rear door. There was scarcely room for him, but Nimbus did not care to lose any time in putting him out.

The car was speedily got under way and soon was merrily sailing along in the direction of the North Pole.

“The Equine Ox crowded into the rear door”

“IT IS a good thing that both the Evening Star and the Equator shine,” said Billy. “We can find them so easily in the dark.”

“But there isn’t going to be any dark,” said Jack Frost.

“Oh, but there will be at night!” said Billy confidently. “It is always dark at night. It has to be or you wouldn’t know it was night.”

“But there won’t be any night for six months where we are going,” said Jack Frost. “There never is at the North Pole.”