To the South lay Propontis, capital of

Mars. But between it and the homesick

Earth-youth stretched a burning desert—lair

of the deadly Avis Gladiator!

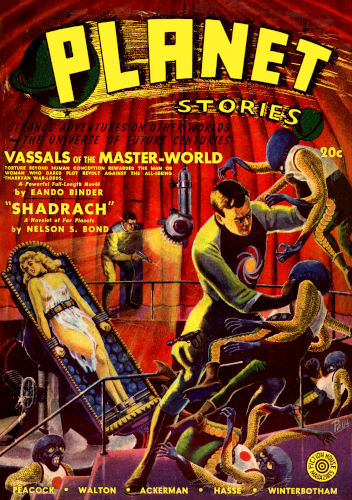

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Fall 1941.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It wasn't the grim thought that he would be dead in a few moments that filled the mind of Don Moffat so much as the bitter realization that a sixteen-year-old suspicion had been confirmed too late.

Across the small room a mad light burned in the blood-shot eyes of his uncle. In spite of the raw liquor he had drunk, the grimy paw that held the old electronic gun was steady.

Beyond the battered hut's open door heat-blasted desert pulsated as a tiny sun beat savagely down on the arid, sterile wastes from the inferno's distant rim.

It was that southern rim, a mere uneven thread of rust, to which Don had raised his eyes so many times that day, his heart light with the thought that he was going to Propontis. And from Propontis to a greener world beyond—a world he had dreamed of one day seeing; a world where water wasn't priceless. Earth!

Just entering his twenties, he had spent his life on the Martian wastelands, a motherless kid who had trailed a diamond-mad father over the wilderness of sand and rock.

Don had been seven when they struck the Suzie lode. There were plenty of the rough stones, and his father sent for the boy's uncle and his own brother. Together they were to mine and share alike.

Shortly after his uncle had arrived Don found his father with a charred hole in his heart, bleaching on the sand. Uncle Fred had cursed at him when he wept. Later, though, the man explained that it must have been one of the native Martians. Don believed him then, but as he grew and came to know his uncle, he began to doubt.

That morning Uncle Fred had abruptly announced that they were through, that the last gem had been mined from the Suzie lode. But there were many diamonds in the plastic boxes, enough to satisfy any man. They would pack their Iguana, Gecko, and make ready for the long trek.

So Don had stowed the saddle-bags and water-tanks. Gecko was ready and waiting outside. Don's last act was to gather his own scanty belongings. He was in the hut alone when Uncle Fred came in. Don raised his eyes to find himself staring into the belled muzzle of the electronic gun.

"Desert brat," said Uncle Fred thickly. "I'll blow you so wide open that there won't be a square meal left for a Wirler!"

And now Don knew that he was to die by the same hand that had killed his father. And Fred was through with him. The boy had helped to mine the gems, but his uncle had never intended that he should live to share them. That was why Uncle Fred had been drinking all day—to bolster up his courage to do deliberate murder. He raised the gun an inch. Don saw his finger tighten on the trigger. He closed his eyes, knowing that it would be all over in a moment.

The paper-thin walls of the hut vibrated with the thunderous crash of an electronic pistol. Donald's jaw went slack. For a paralyzing second he could only gape at his uncle. The man had uttered a choking cry, his fingers loosening the gun. Then he pitched to the floor in a limp heap.

In the open doorway stood a bullet-headed, brown-eyed man, holding a still-glowing electronic pistol. Over his shoulder peered a bearded, thick-lipped companion.

Bullet-head shifted his gaze to the boy.

"Glad we showed up?" he asked, grinning.

"Sure am. Thanks," said Don, eying the two men closely. They weren't settlers nor native-born sons of settlers. For the strangers walked with difficulty. They had yet to learn the gliding stride that was second nature to Don. And their complexions had never been won on Mars.

"You must be Don," said Bullet-Head.

"Right," said Don shortly. "What's your tag?"

"Call me Pete. I heard about you from your uncle last time he was in Strada." Strada was the diamond center of Mars, Don knew. His uncle had been there a month ago with some specimens. There were only three kinds of people in Strada, the boy thought; business men, police and thieves. Hastily he ruled out the first two. His uncle must have told too much about his pay-load. These men had decided to cash in before it had reached a civilized city.

Pete's brown eyes wrinkled. "Right, son," he said amiably. "We're here for the diamonds. Consider yourself lucky to be alive. Now just keep your mouth shut and pack that lizard of yours. We're going to Propontis."

Don didn't ask any more questions. While he was filling the water tanks from their stores he thought with desperate clarity and speed. They were city men—earthmen, and could have hoofed it all the way. He knew how an Iguana could go sullen and completely intractable if it were mishandled; that, he guessed, was what had happened to the outlaw's pack-lizards. From the thin crust of sand on their boots the boy guessed that they hadn't had to walk more than a few miles.

Don turned, and caught a glance that the two outlaws exchanged. In that look the boy read an answer to any other question in his mind. Don knew then that he had escaped death at his uncle's hands only to face it eventually from these two.

Pete eyed him quizzically. "Let's get going," said the outlaw. "We'll put some distance between us and this shack before we camp for the night."

The boy gave Gecko a friendly whack on the tail. The lizard cocked a lazy eye and ambled off, the rest following.

Behind him Don could hear the two men talking in low undertones. Only one snatch of conversstion was clear. "Dumb Martian!" Pete had grunted, and his friend had snickered agreement.

The boy smiled to himself. Yes, he thought, he was a dumb Martian. What chance had he had to learn in a land where everything withered under the scorching sun, and where only ugly venomous creatures survived? True, he had read his father's old books, but he had only half understood them. They were mostly treatises on practical mining and engineering, the rest unreal blood-and-thunder tales of life in the space lanes.

Two hours later Pete called a halt. He never took his eyes off Don as preparations were made for the night camp. His companion cooked a meal out of tins; the outlaws ate most of it and flung the scraps to the boy.

"Brought plenty of water?" asked Pete, tilting a canteen.

Don nodded.

"That's good. Because if we run short you'll be the first to do without. When's the soonest we can expect to get to Propontis?"

"Four days," said Don shortly.

Pete raised his brows. "That long?" he asked. "We'd better bunk for the night." He pulled out his sleeping bag and dropped it on the bare sand. Don smiled grimly. That was no way to live on the desert, he knew. The boy burrowed down until he struck the red layer of sand that retained the day's heat. There he spread his sleeping-bag and crawled carefully in after taking off his heavy sand-shoes. With his free arms he banked the red sand over his legs before unfolding the top flap.

"Kid!" called out Pete.

"Yes?" said Don, stopping short in his preparations.

"I thought I'd tell you—I have my blaster under my pillow. And I'm a light sleeper. Get that?"

"Yes," said Don coolly. He went on with his bedding. The boy had no intention at all of running away. The desert was his friend, but the most implacable enemy that these city men could hope to find.

Whether or not Pete slept lightly Don didn't know. He awoke snug and warm when dawn was striping the wastelands with rosy hues. As he looked into the horizon he knew that the day would be a blistering one.

The outlaws awoke stiff and lame, barely able to crawl out of their sleeping-bags and not even knowing that they had made the mistake of sleeping on the hard-packing top layer of sand.

By the time they had started and eaten a meager breakfast the outlaws had swilled down a full quart of water apiece. Don wisely contented himself with the moisture to be found in the green food he had packed.

As the full glare of the sun began to strike the scorching sands the two Earthmen began to lag. Don slowed his gait for them. They called for water often; so often that at last he was forced to remind them that they were drinking too much.

Pete glared at him out of his red-rimmed eyes, false geniality gone. "Brat!" he snarled. "You'd like to see us die of thirst, wouldn't you?"

Don didn't answer, and silently gave them water whenever they called for it. By noon both men were suffering from the choking heat. In the early afternoon Pete called a halt, coughing dryly.

"We're stopping here," he said hoarsely, raising a limp arm at an outcropping of rock that shelved over a stretch of sand, casting a jet-black shadow. The boy did not speak, but he knew that these rock formations were little less than refractory furnaces, concentrating in one innocuous spot the terrible radiations of the desert sun. Pete coughed again, his smooth skin paling. Suddenly a sort of sympathy came over the boy.

"Look," he said, tossing a bit of vegetation under the rock. It crisped and blackened. The outlaws stared, first at the cinder and then at Don. Pete's face twitched with strain as he spoke: "Smart kid? Maybe you're too smart for us!" His hand fell to his belt, where he wore his bell-mouthed electronic pistol.

The other of the two laid a hand on his arm. "Cut that out," he said slowly. Then, turning to Don, "Thanks, kid." Stolidly he spread out his sleeping-bag and squatted down on it to await the night. Pete sprawled face-down, breathing heavily till the darkness fell. Then Don, who had bedded down Gecko the Iguana, and the other slid him into the sleeping-bag.

Before he put up the flap of his own bag Don turned to the silent outlaw and said: "Half a tank of water left. Ought to hold out if we're easy on it. There's a water-hole ahead—there was once, I mean. Maybe it isn't dried up. But it's the wrong season."

"Right," said the outlaw.

Nothing more was said that night.

In the morning, after packing, Don measured out the remaining water into three canteens. He gave one to each of the outlaws and put his own on Gecko's back.

The heat was worse than the day before. By noon Gecko was voluntarily picking up speed, the spines on his horny back moving first one way and then the other. Don knew the signs. The lizard sensed water ahead.

"We can't be sure," Don shortly told the Earthmen. "It might not be drinking water—for us."

Thirty minutes later they came upon it, a small patch of rust-red mud and slime. One of the outlaws groaned.

"Dried up," whispered Pete dully.

Don said nothing. There was some coarse growth that the pack-lizard began to eat. The boy was glad of that. He had begun to worry about Gecko, but now the Iguana would be good for a longer trek than the one before them.

Pete was on his knees, clawing at the mud. The other watched him for a moment, then looked at Don inquiringly, who shook his head. "He'll only poison himself," said the boy.

The outlaw took his companion by the collar, hoisted him to his feet. "Take this," he said slowly, offering his canteen. "That mud's deadly."

Pete took the canteen and tilted it, swallowing convulsively. His companion pulled away the precious container. "That's enough," he said. "It has to last."

A wild curse ripped from Pete's lips. He snatched back the canteen and drew his gun. In a voice that was hard to recognize as human, he rasped: "Stand back—you an' the brat!"

His finger whitened on the trigger of the blaster.

And then there sounded about them a curiously soft, derisive hooting, seemingly from every point of the horizon. Pete stared wildly about him. There had risen from the sand, it seemed, ghostly shapes—tall, spindly creatures holding recognizable blowguns against their lips. The outlaw's gun lowered, and he looked at Don.

"Native Martians," said the boy. "Don't shoot—they know how to use those blowguns. They might not harm us." There was no time to say more, for the weird creatures had noiselessly advanced on them, holding spread before them what seemed to be heavy draperies.

Don hadn't even to wonder before one of the things was clapped over his head. He felt himself being picked up and carried.

Part of the time consumed by the enforced journey he dozed fitfully, but while he was awake he thought with strange clarity and precision, dreaming of the other greener world he had hoped to see. The boy was almost stifled under the heavy folds of the blanket when, after hours of travel, the Martians removed it.

Free of the torment, he drew a deep breath, blinking his eyes as he looked about him. The first thing he saw were the two Earthmen peering dazedly about them, their eyes not yet accustomed to the sudden change of light.

And when Don looked beyond the outlaws he gasped in stunned astonishment. Fronting them were the ruins of an old city!

That, he thought, must have been why they had been covered with the blankets. The Martians wanted to keep the location of the place a secret.

It seemed to the wondering boy that giants had played here a while. He saw great statues, perhaps of forgotten gods, misshapen things with cruel faces, tumbled over on one side. He saw vast paving-stones, hewn from solid rock, thrust up from their bed of sand, standing at all angles, cracked and split. He saw great buildings, strong as fortresses, fallen into ruins. In one place that must have been a public square a tide of sand broke in still waves about the base of a truncated pyramid.

"Where are we?" choked Pete, the first of the three to recover from the shock. He stared about blankly. "It's like a city of the dead," he whispered hoarsely.

"You're right," Don told him. "It is a city of the dead. An ancient, long deserted city of the Martians, the ancestors of the degenerates who hold us captive. This band uses it as their base from which they launch raiding parties."

Don had no time to say more. The Martians goaded their captives ahead of them down streets that had once echoed to the tread of a thousand feet. The humans picking through squares where multitudes had shouted saw no other living thing but a shimmering green lizard that basked on a fallen god. There was no sound but that of the ever-creeping sands. The old people were gone leaving only ghosts, and the hand of Time in its unhurried way had long since set about the task of wiping out all trace of their existence.

The party turned suddenly around the jutting corner of an immense white stone edifice. Then Don saw something that took his breath away.

Before him was a great towering structure, a temple judging by the cryptic signs that adorned its face. Before the temple was a sunken triangular amphitheater of shining yellow stuff. A glance told Don that the great pit was made of shining bars and heavy slabs of hand-hammered and hand-polished metal.

Don wondered why the outlaws were eying the sunken pit so intently. Since he had been raised on Mars, Don had never heard of gold.

But it was the birds perched on the top ledge of the amphitheater that caught Donald's attention as he neared the temple.

There were hundreds of them—Wirlers with plump bodies and pinkish eyes, iridescent Zloth poking busily with their long, sharp beaks, spotted Cotasi standing in somber dignity, and everywhere huge black Sominas. Don paused. These birds made him cold in his stomach.

"What are those?" asked Pete, his smooth face uneasy.

"Birds native to Mars," said the boy. "But I've never seen them in such numbers." The Martians and their prisoners halted before a small, square stone building.

Pete was singled out by one of the gangling creatures, and yanked inside the little structure. The other outlaw was forced in after him. Don watched with a strange feeling of detachment as the two vanished into the building. It was the heat, the withering heat, that caused that. It sapped all the strength from one's body and left him feeling slow and dim-witted.

As he stood there he noticed belatedly something he had been looking at all the while but had not really noticed. It was a small clump of stunted trees, growing a few paces back from the edge of the amphitheater. Their crooked branches were overladen with the globes of some bright red fruit.

A sudden impulse came on him. He could just touch one of the limbs. A moment later one of the red fruit was in his pocket. He forgot about the thing as soon as he saw Pete and his guards emerge from the building. "What happened?" the boy asked.

The outlaw coughed dryly. "They showed me some kind of machine—motor—something. I don't know what they wanted." He grinned feebly. A moment later the man backed away in alarm as one of their captors approached him. Deliberately the Martians flung the contents of a clay gourd into the outlaw's face. The Martian laughed, a hollow, croaking boom that sounded like sacrilege in that city of the dead. He gave some order in his gobbling tongue, and two Martians unceremoniously shoved the weakly struggling Earthman into the deep pit of the amphitheater.

The Martians looked on stolidly as the outlaw raved and cursed, berating them. Then, suddenly, the air above the pit seemed to blast wide open. A shrieking, unhuman sound beat at the ears of the boy; he jerked his arms up to shield his face. For the hundreds of birds clustered grimly about the city were in flight—necks outstretched, eyes glittering, feathered bullets.

Pete screamed faintly and fell to the ground shielding himself. Then he was overwhelmed by the dark, whirring mass.

The birds had gone berserk. They drove straight for the man's face, hundreds of them. His flailing arms smashed against their soft bodies, batting them out of the air, crushing them to the ground, but hundreds more took their places, pecking at him with frenzied beaks, uttering harsh, discordant cries.

It had all happened so quickly that it caught Don off guard. It was incredible—birds attacking a human being! He jerked forward. Immediately Martians rushed to the aid of his guards. His young muscles strained to break their grip, but in their hands he was powerless. Agonized, he watched Pete die, a swaying, staggering figure seen dimly through a heaving whir of wings and stabbing beaks.

Finally it was over and the birds, flying heavily, reeled through the air to their old posts, leaving behind them a hundred dead and dying of their kind, the result of the outlaw's frantic blows.

The boy turned his eyes away from the gory mess on the floor of the amphitheater. In spite of his horror his mind was working with desperate clarity. Birds do not attack human beings. It was against nature. What had maddened them to their deed?

His eyes widened as he saw the second of the outlaws dragged from the little building, his face dripping with the fluid. And then a forgotten memory linked itself with what he saw. The liquid that had been poured on the Earthmen was Xtholla—Martian language for "bird-lure." It could be distilled from certain wasteland plants which the birds ate as a natural tonic and medicine. But the concentrate of these plants had no mild effect of stimulation. Birds went mad when they smelled its faint pungent odor. It had a tropic effect on their ganglia; they had to go to it, gobble it down and wallow in the stuff. They pecked savagely at anything that had on it the slightest trace of the distillate.

"The pit!" called the boy frantically. "Don't let them—" but one of his guards struck his mouth and he fell silent, knowing that there was nothing more he could do to avert the fate that was before the outlaw.

The man was wholly paralyzed with fear. The Martians laughed as they hurled him into the pit. Again the birds swooped, converging on the terror-stricken man from all points of the compass. They flung their soft bodies against him at murderous speed, sharp beaks stabbing till he bled from a myriad wounds.

When Don looked up again the birds were reeling back through the air. The boy could not bring himself to look at the thing in the arena. A sudden chill gripped him as his guards grimly took his arms. They were leading him to the little building from which had come the Earthmen, he thought swiftly, and he was to undergo a life-or-death test. He held himself tense as they passed through the ancient doors of the structure.

The walls, he saw, were studded with tubes that had not lit for untold millennia; machinery of bizarre design covered the floor. The boy jumped as a Martian touched his arm. The gangling travesty on humanity pointed grimly at a device that alone of the machinery seemed to have been dusted off and wiped with oil.

It was a small motor. The motionless belts and brushes seemed oddly familiar to the boy. Then he had it! He had seen pictures of just such motors in one of the old books of his father. But what did the Martians expect him to do? Obviously the natives wanted him to start their machine but how could he? He had none of the sources from which electricity was derived—no steam, no water-power, as they called it on his father's planet.

As Don glanced at the open door and saw the crowd of demoniac faces framed in its portals, he knew what fate awaited him if he failed. The same ruthless sentence that had been executed on the outlaw Earthmen would fall on him.

The eyes of his guard became dull and deadly as he saw Don did nothing to the motor.

Then the idea came. Feverishly the boy went to work, racking his brains for all the details in that old book, "Electricity for the Practical Miner." He remembered the title clearly, and ground his knuckles into his eyes to bring before them the simple diagrams that he once had learned.

Hesitantly he salvaged from a pile of scrap in one corner of the room two metal plates and lengths of wire. One, he fervently prayed, was copper and the other zinc. But he could not be sure. The boy clumsily connected the two terminal wires of the motor, one to each of the plates.

Then he did what seemed a foolish thing. He took the globe of red fruit from his pocket and sliced it neatly into thin layers. Don laid the dripping slices atop the copper plate, and then, his heart cold as ice, laid the zinc plate atop the fruit.

The Martians watched coldly, grunting to themselves. Their eyes were on the world-old motor. Slowly, incredibly, the thing turned over. The straps sped over the drums; the brushes fizzed and emitted inch-long blue sparks.

And from overhead came a sudden, terrifying wail like nothing that had been heard on Mars for countless ages. It was not the cry of an animal nor of a man—that was all the boy knew as he backed against a wall of the building. The noise rose sickeningly in a demoniacal shriek. The Martians seemed paralyzed by the awful sound. Then, with choking cries, they broke ground and ran, their eyes popping and the shout, "Kursah-ekh!" bursting from their lips. Don knew little of the language, but he did know that their cry was "Demons!"

The natives fled with the speed of wild things, and the boy found himself alone. No, not quite alone, for into the door of the little building poked the familiar old head of Gecko, Don's pack-lizard. He nearly embraced the ugly creature. It would have been hell to go without water for another minute. From the canteen on the Iguana's back Don took a long, refreshing swig. Then he turned again to the motor.

It was still turning over, but more slowly. He was about to separate the plates when it stopped of its own accord and the fiendish wail from above died away. The boy nimbly scaled the web-work construction and pried about the tangle of machinery until he found the obvious answer. It had been a blower operated by the motor, to which had been attached a simple siren. Burglar-alarm, perhaps, or danger signal, he thought. At any rate it had saved him.

He laughed as he descended slowly. The old book had been right. Fruit acid between zinc and copper made the simplest sort of generating battery cell. What knowledge he had possessed he had used to the full. He drank again from the canteen.

And a few moments later with Gecko at his side, he left the city of the dead behind, Don was going to a greener world.