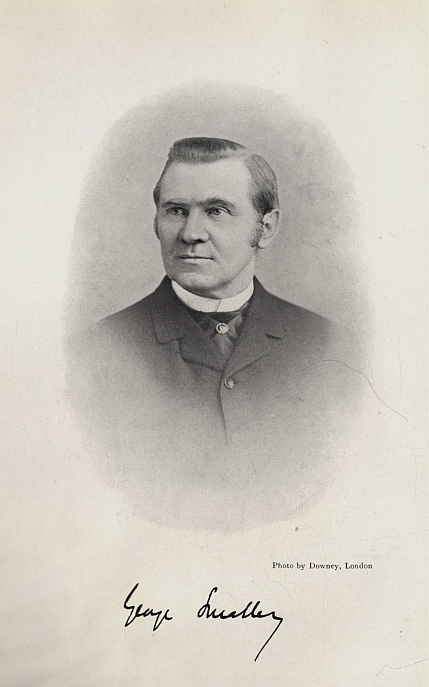

George Smalley

BY

GEORGE W. SMALLEY, M.A.

AUTHOR OF "STUDIES OF MEN,"

"LIFE OF SIR SYDNEY WATERLOW," ETC.

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

1911

Copyright, 1911

BY

GEORGE W. SMALLEY

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

PREFACE

These Memories were written in the first instance for Americans and have appeared week by week each Sunday in the New York Tribune. This may be evident enough from the way in which some subjects are dealt with. But they must stand in great part as they were written since the book is published both in London and New York.

They are, in some slight degree, autobiographical, but only so far as is necessary to explain my relations with those men and women of whom I have written, or with the great journal, the New York Tribune, I so long served. But they are mainly concerned with men of exceptional mark and position in America and Europe whom I have met, and with events of which I had some personal knowledge. There is no attempt at a consecutive story.

LONDON, December, 1910.

Contents

New England in 1850—Daniel Webster

Massachusetts Puritanism—The Yale Class of 1853

Yale Professors—Harvard Law School

How Massachusetts in 1854 Surrendered the Fugitive Slave Anthony Burns

The American Defoe, Richard Henry Dana, Jr

A Visit to Ralph Waldo Emerson

Emerson in England—English Traits—Emerson and Matthew Arnold

A Group of Boston Lawyers—Mr. Olney and Venezuela

Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips and the Boston Mobs

Wendell Phillips—Governor Andrew—Phillips's Conversion

William Lloyd Garrison—A Critical View

Charles Sumner—A Private View

Experiences as Journalist during the Civil War

Civil War—General McClellan—General Hooker

Civil War—Personal Incidents at Antietam

A Fragment of Unwritten Military History

The New York Draft Riots in 1863—Notes on Journalism

How The Prussians after Sadowa Came Home to Berlin

A Talk with Count Bismarck in 1866

American Diplomacy in England

Two Unaccredited Ambassadors

Some Account of a Revolution in International Journalism

Holt White's Story of Sedan and How it Reached the "New York Tribune"

Great Examples of War Correspondence

A Parenthesis

"Civil War?"—Incidents in the 'Eighties—Sir George Trevelyan—Lord Barrymore

Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Alaska Boundary

Annexing Canada—Lady Aberdeen—Lady Minto

Two Governors-General, Lord Minto and Lord Grey

Lord Kitchener—Personal Traits and Incidents

Sir George Lewis—King's Solicitor and Friend—A Social Force

Mr. Mills—A Personal Appreciation and a Few Anecdotes

Lord Randolph Churchill—Being Mostly Personal Impressions

Lord Glenesk and "The Morning Post"

Queen Victoria at Balmoral—King Edward at Dunrobin—Admiral Sir Hedworth Lambton—Other Anecdotes

Famous Englishmen Not in Politics

Lord St. Helier—American and English Methods—Mr. Benjamin

Mrs. Jeune, Lady Jeune, and Lady St. Helier

Lord and Lady Arthur Russell and the "Salon" in England

The Archbishop of Canterbury—Queen Alexandra

A Scottish Legend

A Personal Reminiscence of the Late Emperor Frederick

I. Edward the Seventh as Prince of Wales—Personal Incidents

II. Prince of Wales and King of England—The Personal Side

III. As King—Some Personal and Social Incidents and Impressions

ANGLO-AMERICAN MEMORIES

ANGLO-AMERICAN MEMORIES

My memories begin with that New England of fifty years ago and more which has pretty well passed out of existence. I knew all or nearly all the men who made that generation famous: Everett; Charles Sumner, "the whitest soul I ever knew," said Emerson; Wendell Phillips; Garrison; Andrew, the greatest of the great "War Governors"; Emerson; Wendell Holmes; Theodore Parker; Lowell, and many more; and of all I shall presently have something to say. Earlier than any of them comes the Reverend Dr. Emmons, a forgotten name, for a long time pastor of the little church in the little town of Franklin, where I was born, in Norfolk County, in that State of Massachusetts on which Daniel Webster pronounced the only possible eulogy: "I shall enter on no encomium upon Massachusetts; she needs none. There she is. Behold her, and judge for yourselves. {2} There is her history; the world knows it by heart." Whether the world knows it by heart may be a question. We are perhaps a little too apt to assume that things American loom as large to other eyes as to our own. But whether the world knows Massachusetts by heart or not, we know it; and the rest does not much matter. Every son of hers will add for himself "God bless her."

Dr. Emmons was of the austere school of Calvinists, descending more directly from the still more austere school of Jonathan Edwards. I cannot have been more than three or four years old when I last saw him, but I see him still: tall, slight, bent, wasted; long grey locks floating loosely about his head; his face the face of an ascetic, yet kindly, and I still feel the gentle touch of the old man's hand as it rested on my baby head. And I see the imprint of his venerable feet, which it was his habit to rest on the painted wainscotting of his small, scantily furnished study.

My father was first his colleague, then his successor; then was called, as the phrase is, to the Second Congregational Church in Worcester; whence he passed many years later to the First Presbyterian Church in Troy, N.Y., where he died. Worcester was at that time—1840 to 1860—a charming example of the thriving New England village which had grown to be a town with pleasant, quiet streets—even Main Street, its chief thoroughfare, was quiet—and pleasant houses of colonial and later styles standing in pleasant grounds. A beautiful simplicity of life {3} prevailed, and a high standard; without pretence, not without dignity. The town had given, and was to give, not a few Governors to the Commonwealth: Governor Lincoln, Governor Davis ("Honest John"), another Lieutenant-Governor Davis, and two Governor Washburns: to the first of whom we lived next door in Pearl Street; in the shadow of the Episcopal Church of which the Rev. Dr. Huntington, translated afterward to Grace Church in New York and widely known, was rector. Later I read law for a year in the office of Governor Washburn's partner: afterward that Senator Hoar who in learning and capacity stood second to few in Washington, and in character to none.

Twenty years ago, my mind filled with these images of almost rural charm, I went back on a visit to Worcester. It had grown to be a city of near one hundred thousand people, and unrecognizable. The charm had vanished. The roar of traffic was to be heard everywhere; surface cars raced through the streets; blazing gilt signs with strange and often foreign names emblazoned on them in gigantic letters, plastering and half hiding the fronts of the buildings; mostly new. It might have been a section of New York—at any rate it was given over to the fierce competition of business. Of the tranquillity which once brooded over the town, no trace was left. I suppose it all means prosperity, in which I rejoice; but it was not my Worcester.

If it be still, as we used affectionately to call it, the Heart of the Commonwealth, then I suppose {4} the Commonwealth also has changed; for better or for worse, according to your point of view. Boston certainly has changed, and as certainly for the worse. Where is the old Boston we all loved? What has become of those historic streets which the great men of more than one great generation trod? Where is the dignity, the quaint, old-fashioned beauty, the stamp of distinction, the leisureliness of life, the atmosphere which Winthrop and Endicott, John Hancock and Otis, Everett and Andrew, once breathed? The only Boston they knew is to-day a city of tumult and uproar, amid which the State House and the Common and the Old South Church and State Street itself seem anachronisms and untimely survivals of other and holier days.

In the old Worcester—and, for aught I know, in the new—far up on Elm Street as it climbs the hill and pushes toward the open country, stood Governor Lincoln's house—square, white, well back from the street; a fence enclosing the broad lawn, steps and an arched iron gateway in the centre. To me ever memorable because there I first saw Daniel Webster. He had come to Worcester campaigning for Taylor, whose nomination for the Presidency, over his own head, he had at first declared "unfit to be made." He arrived in the dusk of evening, and drove in Governor Lincoln's open landau to the house. A multitude waiting to greet him filled the street. Webster descended from the carriage, went up the three steps from the sidewalk to the gateway, {5} turned, and faced the cheering crowd. The rays from the lighted lantern in the centre of the arch fell full on his face. I do not remember whether I thought then, but I have often thought since of what Emerson said:

"If Webster were revealed to me on a dark night by a flash of lightning, I should be at a loss to know whether an angel or a demon stood before me."

That night, at any rate, there was a touch of the demon. His advocacy of the successful soldier was an act of renunciation. The leadership of the Whig party belonged to him and not to Zachary Taylor; or if not to Webster, it belonged to Henry Clay. He had not forgiven his successful soldier-rival. He never forgave him. Nor could he all at once put to sleep for another four years his honourable ambition. His eyes blazed with a fire not all celestial. The grave aspect of the man and grave courtesy of his greeting to the people before him only half hid the resentment which fed their inward fire. But he stood a pillar of state—

... deep on his front engraven

Deliberation sat and public care.

A colossal figure. We boys in Massachusetts were all brought up to worship Webster, and worship him we did; till the Fall came, and the seventh of March speech turned reverence into righteous wrath.

There was a certain likeness in feature between Mr. Webster and Mr. Gladstone. The eyes in both were dark, deep set, and wide apart, beneath heavily overhanging brows. In both the flame was volcanic. The features in both were chiselled strongly, the lines clear cut, the contour of the face and the air of command much the same in the great American and the great Englishman; but Mr. Gladstone had, before the political disasters of his later years had angered him, a benignity which Webster lacked. In stature, in massiveness of frame, in presence, in that power which springs from repose and from the forces of reserve, there was no comparison. Webster had all this, and Gladstone had not. I have before me as I write a private photograph of Mr. Gladstone, from the camera of a lady who had something more than technical skill, who had a sympathetic insight into character and an art-sense. Among the hundreds of photographs of the Tory-Liberal, the Protectionist-Free Trader, the Imperialist-Home Ruler, this is the finest and truest I have seen. But it is one which brings out his unlikeness to Webster far more clearly than those resemblances I have noted. If those resemblances have not before been remarked, there are, I imagine, few men living who have seen both men in the full splendour of their heroic mould.

The records of those later days are full not only of admiring friendship for Webster, but also of that bitterness which his apostasy—for so we thought it—begot. Even friends turned against {7} him after his support of the Fugitive Slave Law. As for his enemies, there was no limit to their language. A single unpublished incident will show what the feeling was. At a meeting of the Abolitionists in the Boston Melodeon, Charles Lenox Remond, a negro, in the course of a diatribe against the white race, called Washington a scoundrel. Wendell Phillips, who was on the platform, intervened:

"No, Charles, don't say that. Don't call Washington a scoundrel. The great Virginian held slaves, but he was a great Virginian still, and a great American. It is not a fit word to use. It is not descriptive.

"Besides, if you call Washington a scoundrel, how are you going to describe Webster?"

Besides, again, the Fugitive Slave Law wrought the redemption of Massachusetts; and we owe that redemption to Webster, indirectly. It was the rendition of Anthony Burns, in 1854, two years after Webster's death, which completed the conversion of the Bay State from the pro-slavery to the anti-slavery faith. But what I can tell of the unwritten history of those black days must be for another time.

Whatever Webster's faults, and whatever resentment he aroused in 1850, he remained, and will long remain, the foremost citizen of Massachusetts in that generation. Go to his opponents if you want testimony for that. Ask Wendell Phillips, and he answers in one of his finest sentences, pouring scorn on the men who took up, {8} so late as 1861, Webster's mission to crush anti-slavery agitation:

It was Webster who announced from the steps of the Revere House that he would put down this agitation. The great statesman, discredited and defeated, sleeps at Marshfield by the solemn waves of the Atlantic. Contempsi Catiline gladios; non tuos pertimescam. The half-omnipotence of Webster we defied; who heeds this pedlar's empty speech?

Ask Theodore Parker, who delivered in the Music Hall of Boston a discourse on Webster's death; half-invective, more than half-panegyric, whether he would or no. It was, I think, Parker who said of him that four American masterpieces in four different kinds were Webster's. The ablest argument ever heard in the Supreme Court of the United States, that in the Dartmouth College case, was his. His was the noblest platform speech of his time at the dedication of Bunker Hill Monument. His the most persuasive address to an American jury, in the White murder case at Salem, with its tremendous epigram, "There is no refuge from confession but suicide; and suicide is confession." His, finally, the profoundest exposition of constitutional law, the reply to Hayne in the United States Senate. All these were Webster's, and to Webster alone could any such tribute be paid.

When I heard Webster in Faneuil Hall, where he was perhaps at his best and most at home, it seemed to me it mattered little what he said. {9} The authority of the man was what told. Before he had uttered a word he had possession of the minds of the three thousand people who stood—for we were all standing—waiting for the words we knew would be words of wisdom.

Twice I have seen a similar effect by very different artists. Once by Rachel at the Boston Theatre, as Camille in Corneille's Horace, when the mere apparition of that white-robed figure and the first rays from those deep-burning eyes laid a spell on the audience. Not once, but many times, by Aimée Declée, at the Princess's Theatre in London and at the Gymnase in Paris. Of her I shall have something to say by and by, but I name her now because she had that rarest of gifts, the power of gathering an audience into her two small hands while still, silent and motionless; and thereafter never letting them go. In her it was perhaps a magnetic force of emotion, for she was the greatest of emotional actresses. In Webster it was the domination of an irresistible personality, with an unmatched intellectual supremacy, and the prestige of an unequalled career.

Whatever it was, we all bowed to it. We were there to take orders from him, to think his thoughts, to do as he would have us. He might have talked nonsense. We should not have thought it was nonsense. He might have reversed his policy. We should have held him consistent. We should have followed him, believing the road was the same we had always travelled together. He was still the man whom Massachusetts delighted to {10} honour. The forces of the whole State were at his disposal, as they had been for thirty years.

He stood upon the platform an august, a majestic figure, from which the blue coat and buff trousers and the glitter of gilt buttons did not detract. Once, and only once, have I found myself under the sway of an individuality more masterful than Webster's, much later in life, so that the test was more decisive; but it was not Mr. Gladstone's.

Massachusetts was in those days, that is, in the middle of the last century, in the bonds of that inherited and unrelaxing Puritanism which was her strength and her weakness. Darwin had not spoken. The effort to reconcile science and theology—not religion—had only begun. Agassiz's was still the voice most trusted, and he, with all his scientific genius and knowledge, was on the side of the angels. The demand for evidence had not yet overcome the assertion of ecclesiastical authority in matters of belief. The spiritual ascendancy of the New England minister was little, if at all, impaired, and his political ascendancy had still to be reckoned with. There were, I suppose, no two places in the world so much under the dominion of one form or another of priestly rule as the six New England States and Scotland; and therefore no two between which spiritual and political resemblances were so close.

There were, however, influences which while less visible were sometimes more potent. The pastor was the figurehead of a Congregational Church; or, to use Phillips's simile, he was the {12} walking-beam which the observer might think the propelling force of the steamboat. "But," said Phillips, "there's always a fanatic down in the hold, feeding the fires." The fanatics were the deacons. They often had in them the spirit of persecution. They encroached upon, and sometimes usurped, the rightful authority of the true head of the Church, the pastor, in matters of faith and matters of conduct alike. They constituted themselves the guardians of the morals of the flock, the pastor and his family included. My father was a man whose mind ran strongly toward Liberalism. He had nothing of the inquisitor about him. But his deacons were possessed with a school-mastering demon. They had the vigilance of the detective policeman and a deep sense of responsibility to their Creator for the behaviour of their fellow-men. Good and conscientious citizens all of them, but indisposed to believe that men who held other opinions than theirs might also be good. Their individual consciences were to be the guide of life to the rest of the world. If they had not the ferocity of Mucklewraith they had his intolerance. They would have made absence from divine service a statutory offence, as the earlier Puritans did. Two services each Sunday, a Sunday-school in between, and prayer-meetings on Wednesdays—all these must be punctually attended by us children, and were.

When a decision had to be taken about my going to college, I wished to be sent to Harvard, {13} as every Massachusetts boy naturally would. But Harvard was a Unitarian college, and the deacons persuaded my father that the welfare of my immortal soul would be imperilled if I was taught Greek and Latin by professors who did not believe in a Trinitarian God. This spirit of theological partisanship prevailed and I was sent to Yale. At that admirable seat of learning there was no danger of laxity or heresy. The strictest Presbyterianism was taught relentlessly and the strictest discipline enforced. Chapel morning and evening, three or perhaps four services on Sunday—in all let us say some eighteen separate compulsory attendances on religious exercises each week. Would it be wonderful if a boy who had undergone all this for four years should consider that he had earned the right to relaxation in after days?

None the less willingly do I acknowledge my debt to Yale, a debt which would have been heavier had I been more industrious. The President of the University in our time was the Reverend Dr. Wolseley—learned, austere, kindly, but remote. We boys saw little of him except on a pedestal or in the pulpit. When he bade the class farewell, he made us a friendly little speech and proposed a toast: "The Class of 1853. I drink their healths in water. May their names not be writ in water." Nor were they. Perhaps no class contained so many members who have filled larger spaces for a longer time in the public eye and the public press.

There was Stedman, the poet and poet critic. He left poems which will live forever, but no such body of poetical achievement as he might have produced had not circumstances obliged him to devote to business and to editorial work abilities superior to either. He is not remembered pre-eminently as a poet of patriotism, but the only poem of Stedman's included in Emerson's Parnassus is his "John Brown of Osawatomie," written—was it not for The Tribune?—in November, 1859, while Brown lay in his Virginian jail waiting to be hanged. Stedman, his genius flowering in a prophetic insight, warned them; but his "Virginians, don't do it" rang unavailingly through the land; and his

...Old Brown,

Osawatomie Brown,

May trouble you more than ever when you've nailed

his coffin down

never reached the Virginian mind till Northern regiments sang their way through Southern States to the tune of "John Brown's Body." Stedman's range was wide. He set perhaps most value on his Lyrics and Idylls. That was the title he gave to the volume of poems published in London in 1879; selected by himself for his English readers. His American friends will like to be reminded that the first third of the volume is given to "American Lyrics and Idylls," including "Old Brown," and that tender monody on Horace {15} Greeley which no Tribune reader can have forgotten.

There was Charlton Lewis, an Admirable Crichton in his versatility,—if the serious meaning of that name has survived Mr. Barrie's travesty of it on the stage. We knew him at Yale as a mathematician who played with the toughest problems proposed to us by mathematical tutors and professors; whose very names I forget. We knew him afterward as lawyer, insurance expert, Latin lexicographer, journalist, financier, and editor of Harper's Book of Facts, the best of all books of facts; but now, or when I last inquired, out of print and not easily procurable. He understood cards also. Playing whist, which I think was forbidden in college, he dealt to his partner and two adversaries the usual miscellaneous hand; and to himself, by way of jest, all thirteen trumps. When the enemy remonstrated Lewis answered: "If you will specify any other order in which it is mathematically more probable that the hands would be distributed, I will admit that this is not the product of chance." An answer to which there was no answer. He delighted in puzzling minds less acute and less scientific than his own. Few men have had a more serviceable brain than his, or known better how to use it; and his power of work knew no limit.

There was Mr. Justice Shiras of the United States Supreme Court. There was Fred Davies, a dignitary of the Church—in whom professional decorum never extinguished a natural sense of {16} fun and good-fellowship. There was, and happily still is, Andrew White, historian, writer of books, President of Cornell University, Ambassador, and, in a forgetful moment, one of President Cleveland's commission to determine the boundary line between a British colony and a foreign state; neither of whom had asked him to draw it. There was Isaac Bromley, one of the world's jesters who make life amusing to everybody but themselves; whom all his colleagues on The Tribune valued for qualities which were his own and not ours. Not the least of the many eulogies which death brought him was the testimony of those who knew him best, that his humour was good-humoured.

The most casual reader must have noticed how various are the talents and characters among the hundred and six graduates of 1853. There are many more. There is Wayne MacVeagh, the most delightful of companions, counsel in great causes all his life, Attorney-General of the United States, Ambassador to Rome, one of the men who paid least respect to social conventionalities, yet in Washington a central figure in society. But neither law nor society gave full scope for the restless energy of his mind. During all the later years I have known MacVeagh he has been a thinker, serious, daring, too often unsound. His reading has been largely among books dealing with those new social problems which vex the minds of men, often needlessly, and disturb clear brains. Novelties interested him; and the drift of his thoughts was toward radical reconstruction {17} and toward one form or another of socialism. He espoused new opinions with vehemence; and sometimes reverted with vehemence to the old. We met again in London some five and twenty years ago. MacVeagh delivered to a little company at lunch a brief but reasoned and rather passionate discourse against our diplomatic service in Europe. When I suggested that we had none, he retorted:

"But we have Ministers and Legations and though some of our Ministers are good and able men, they are wasted. No Minister is needed. All the business of the United States in Europe could be done and ought to be done by Consuls, and all the Legations ought to be abolished, and the Ministers recalled."

I forget just how long it was after this outburst that MacVeagh was appointed Minister to Constantinople; and accepted and served; with credit and distinction, and afterward more efficiently still as Ambassador to Rome.

He had a pretty wit in conversation, and a power of repartee before which many an antagonist went down. A celebrated American causeur once attacked him as a Democrat. "Yes," answered MacVeagh, "I am a Democrat and know it. You are a Democrat and don't know it. You have just been made President of a great railroad corporation. The stock sells to-day at a hundred and twenty; but before you have been President three years, you will have brought it within reach of the humblest citizen."

An unfulfilled prophecy, but that is what makes prophecy so useful as an instrument of debate. Only time can prove it false.

These men and many more gave distinction to the class. Randall Gibson, of Louisiana, afterward Confederate General and United States Senator, cannot be omitted from the briefest catalogue. He was one of a small band of Southerners at Yale. When you came to know him you understood what the South means by the word gentleman; and by its application of the title to the best of its own people, or to the ruling class in the South as a whole. Already, of course, and even in this younger brood, the clash of interests and sentiments, the "prologue to the omen coming on," the strained relations between South and North, were visible, and vexatious enough in social intercourse. Randall Gibson was saturated with Southern ideas, and perhaps had the prejudices of his race, but he kept them to himself or did not impart them to us of the North. He lived in the upper air, yet he looked down on nobody. There was no more popular man, yet no man who held himself so completely aloof from the familiarities common enough as between classmates.

In after life, from the havoc of war and other causes, he suffered much and bore disaster with courage. He was a man with reference to whom it is possible, and was always possible, to use the much-abused word chivalrous, with the certainty it could not be misunderstood. When he died {19} there passed away a beautiful example of a type common in literature, rare in life, rarest of all in this generation, the grand seigneur.

There was lately an Englishman, Earl Spencer, whom Randall Gibson resembled: slightly in appearance, closely in those essential traits which go to the making of character. The same urbanity; the same considerateness to others; the same loyalty of nature; the same shining courage; the same unfailing effort to conform to high ideals. Both men had the pride of race and of descent. In both it turned to fine effects. I have known Lord Spencer to submit—I may be forgiven this distant allusion—to what can only be called an extortion rather than engage in a legal controversy he thought undignified, yet out of which he would have come victorious. I have known Randall Gibson to accept the verdict of fate, the award of undeserved adversity, rather than defend himself when his success might have exposed his comrades to censure. The world may call it in both of them quixotic, but the world would be a much better place to live in if quixotry of this sort were commoner than it is. Neither of these two men railed against the world, or complained of its ethical standard. All they did was to have each a standard of his own and to govern their own lives accordingly.

The three Yale professors whose names after all these years stand out most clearly to me are Thacher, Hadley, and Porter. Professor Thacher taught Latin. They used to say he knew Tacitus by heart—perhaps only a boyish emphasis upon his knowledge of the language and literature. He was, at any rate, a good Latinist, and a good teacher. What was perhaps more rare, he was a genial companion, to whom the distance between professor and pupil was not impassable. He won our sympathies because he gave us his; and our admiration, and almost our affection, went with our sympathies. He was one of the few college dignitaries upon whom the student feels himself privileged to look back as a friend; for on his side the spirit of friendly kindness governed the relations between us.

Of Professor Hadley's Hellenism we expressed our admiration by saying he dreamed in Greek. To us, so long as we were in his hands, Greek was the language of the gods. The modern heresies touching the place of Greek in a liberal education had at that time not been heard of, or had taken no hold upon the minds of either teacher or pupil. {21} We learnt Greek, so far as we learnt it, in the same unquestioning spirit as we read the Bible; so far as we read it. Hadley taught us something more than grammar and prosody. He taught us to look at the world through Greek eyes and to think Greek thoughts. To him the Greek language and literature were not dead but alive, and he sought to make them live again in his pupils. I don't say that he always succeeded; or often, but at least we perceived his aim, and we listened with delight to the roll of Homer's hexameters from his flexible lips. For the time being he was a Greek. To this illusion his dark eyes and olive skin and the soft full tones of his voice contributed. Some of his enthusiasms, if not much of his learning, imparted themselves to us. If we presently forgot what we learned, the influence remained. "I do not ask," said Sainte-Beuve, "that a man shall know Latin or Greek. All I ask is that he shall have known it." A sentence in which there is a whole philosophy of education; a philosophy which the universities that have abolished Greek out of their compulsory courses forgot to take into account.

Professor Porter's mission was to implant in our young minds some conception of Moral Philosophy and of Rhetoric. He taught persuasively, sometimes eloquently, and always with a clearness of thought and purpose which made him intelligible to the dullest and instructive. He had another means of appeal to his students. He was human and sympathetic. We looked {22} upon our professors as, for the most part, beings far removed from us; exalted by their position and virtues above us, and above mankind in general; a sort of demigods who had descended to earth for the good of its inhabitants, to whom, however, they were not of kin. We never thought that of Professor Porter. He had a magical smile; it was the magic of kindness. We fancied that the Faculty dealt with the students in a spirit of strict justice; from their point of view if not always from ours. They were a High Court of Justice which laid down the law and enforced penalties out of proportion to the offence. It was law, and the administration of it was inexorable. Not so Porter. He was never a hanging judge. I know it because I owed to him the privilege of remaining at Yale to the end of my four years. I have quite forgotten what crime I committed, but it was one for which, according to the strict code by which the undergraduates were governed, expulsion was the proper sentence; or perhaps only suspension, which in my case would have meant the same thing. But Professor Porter intervened. There were mitigating circumstances. These he pressed upon his colleagues, and I believe he even made himself answerable for my good behaviour thereafter. I stayed on, and if I did not profit as I ought to have profited by the opportunity I owed to him, I was at least grateful to him, and still am.

Professor Porter became later President of Yale: one on the roll of Chief Magistrates of the {23} University to whom not Yale only but the country is, and for two hundred years has been, indebted. He ruled wisely, fine administrative qualities reinforcing his scholarly distinction. He was beloved, and his name is for ever a part of the history of this great college.

Looking back on those days and on the Professors I have known since, at Yale, Harvard, Columbia, and one or two other American universities, one thing impresses me beyond all others. It is the spirit of devotion in those men; of devotion to learning, to letters, to their colleges, and to their country. Many of them were, and many in these days are, men who had before them other and far more profitable careers. They might have won much wider fame and made a great deal more money. They have been content with the appreciation of their own world, and with salaries which, I believe, never exceed six thousand dollars, and are commonly much less. When English critics, albeit in a friendly spirit, have commented—in private, not in public—on the American love of money-making, I have made this answer, pointing to the absolute unselfishness of one of the highest types of American citizen, all over the land, and to their conception of what is best in American life. I have always added that though others may speak of their renunciation as a sacrifice, they never do. So far as I know them, they are content and more than content; they rejoice in their work and in the modest circumstances which alone their income permits. {24} Now and then we hear of some brilliant scholar as having refused a lucrative post in order to go on teaching and studying. There are many more whom we never hear of publicly, to all of whom the country owes a debt of gratitude if nothing else, which it does not always pay. But here in England if you state the facts you will find them accepted, and welcomed as the best answer to the reproach of money-ambitions—a reproach based on conspicuous exceptions to the general American rule of thrift and simplicity.

After graduating at Yale, and after a year in Mr. Hoar's office at Worcester, I went to the Harvard Law School. Harvard was as much a Unitarian university as ever, but perhaps it was considered that law was a safeguard against loose theology, or perhaps the old reasons were no longer omnipotent. I attempt no comparisons between Yale and Harvard. There is no kind of likeness between undergraduate and post-graduate life. During four years at Yale the discipline had been rigid. At the Law School in Cambridge I cannot remember that we were under any restraint whatever. In New Haven we lived either in the college dormitories or in houses approved by the Faculty; and I am not sure that in my time we did not all sleep within the college limits, insanitary and uncomfortable as many of the buildings then were. But the law student in Cambridge lived where he would and as he would. He went to chapel or not, week-days and Sundays alike, to suit himself. {25} Not even attendance at the law lectures was compulsory. It seems to have been held that students had come to the school upon serious business, and that their own interest and the success of their future careers would be enough to ensure their presence. It was not always so. The very freedom which ought to have put men on their honour sometimes became a temptation. And Boston was a temptation; as it was, and must always be, to undergraduates and graduates alike.

The years were drawing on—it was now 1854—and the sectional antagonism of which there had been evidence enough at Yale was increasing. We were older, and the crisis was nearer. There was a kind of Law School Parliament in which all things were put to the issue of debate, and the air often grew hot. Angry words were exchanged between Southerners and Northerners. The rooted belief of the Southerner, or of many Southerners, that they had a monopoly of courage, was sometimes expressed. More than once challenges were talked of, though I believe none was actually sent. There was a choleric young gentleman from Missouri who put himself forward as champion of slavery, and there was an attempt to deny to us of the North the right to express our opinions on our own soil, which did not succeed. The Missourian was the exception. Of the Southerners in general at Harvard I should say what I have said of those at Yale: if they felt themselves of a superior race they accepted the obligations of superiority, and treated their {26} inferiors with an amiable condescension for which we were not always grateful.

These were not matters of which the authorities of Dane Law School took notice. Their business was to teach Law. Judge Parker was a real lawyer, who afterwards revised the General Statutes of Massachusetts into something like coherence and the symmetry of a Code. He handled the law in a scientific spirit, without emphasis, not without dry humour, and had ever a luminous method of exposition which grew more luminous as the subjects grew more abstruse. His colleague, Mr. Theophilus Parsons, was, I think, what is called a case lawyer, to whom the chose jugée was as sacred as it was more recently to the anti-Dreyfusards. There are always, and I suppose always will be, lawyers to whom decisions are more than principles. Parsons was one of these, while Parker's aim was to present to the student the entire body of law as a homogeneous whole, organic, capable of abstract treatment, capable of being set forth in the dry light of reason. Whether it was the difference in the men or in their methods I know not, but there can be no doubt that Judge Parker's lectures were better attended and more devoutly listened to by the students, and that his system bore fruit. For it created a habit of mind, and under his teaching a legal mind was formed, and became a better instrument for use at the Bar.

The Bar of Massachusetts was at that time in a period of splendour, as it had been for generations. {27} Webster was gone, and there was no second Webster; he was the leader not only of the Massachusetts Bar but of the American Bar. But Rufus Choate was still in his prime, whose eccentricities of manner and of speech could not disguise forensic abilities of almost the first order. Sydney Bartlett, his rival, was as sound as Choate was showy. But Choate also was sound, though he had a spirit of adventure which carried him too far, and a rhetoric not seldom flamboyant. Some of his phrases are historical, as of a witness who sought to palliate his dishonesty by declaring that he never disclosed his iniquitous scheme. "A soliloquy of fraud," retorted Choate. I heard one of his brethren at the Bar say to him as he came into court: "I suppose you will give us a great sensation to-day, Mr. Choate." "No," answered Choate, "it is too great a case for sensation." And he tried it all day with sedateness. Chief Justice Shaw disliked him, or disliked his methods, and sometimes showed his dislike, overruling him rather roughly. The great judge was not an Apollo, and there came a day when Mr. Choate, smarting under judicial censure, remarked in an audible aside to his associate counsel: "The Chief Justice suggests to me an Indian idol. We feel that he is great and we see that he is ugly." But amenities like that were unusual.

General Butler, afterward too famous at New Orleans and Fort Fisher, yet after that the Democratic Governor of Whig Massachusetts, had a none too savoury renown at the Bar. Yet it was {28} said of him by an opponent: "If you try your case fairly, Butler will try his side of it fairly; but if you play tricks he can play more tricks than you can." His sense of humour was his own, sometimes effective and sometimes not. Defending a railway against an action by a farmer whose waggon had been run over by a train, and who alleged that the look-out sign was not, as required by law, in letters five inches long, Butler made him admit he had not looked at the sign. "Then," said Butler to the jury, "it could not have availed had the sign been in letters of living light—five inches long."

The best contrast to Butler was Richard H. Dana, as good a lawyer, or better, and with the best traditions of a high-minded Bar, pursued in the best spirit. But I will leave Dana till I come to the Burns case.

It was in May, 1854, that Anthony Burns of Virginia was arrested in Boston as a fugitive slave and brought before Judge Loring, United States Commissioner under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. I am not going to re-tell the familiar story of his so-called trial and of the surrender of Burns to Colonel Suttle, also of Virginia. The actual military rank held by Suttle I do not know, but I call him Colonel on general principles; or on the principle announced by the late Max O'Rell in his book on America; with its population of sixty millions; "la plupart des colonels." But I will tell what I saw; and what sort of impression the event made at the time upon an eye-witness who belonged to the dominant and most conservative party in the State; the Whig party.

The arrest of Burns made a stir in the old Commonwealth comparable to none other which had occurred down to that time. From Worcester, where I was then reading more or less law with Mr. Hoar, I went to Boston to look on at these proceedings. I went from no particular feeling of sympathy with Burns, nor yet mainly from {30} abhorrence of that subservience to slaveholders in which, until after Webster's Seventh of March speech in 1850, Massachusetts had been steeped. I went from curiosity. I wanted to see how the legal side of it was managed. For though the popular dislike of such proceedings, which neither the Shadrach nor the Sims case had fully roused, was then slumbering, the State had, so long ago as 1843, passed a law forbidding any judge or other officer holding a commission from the State to take any part in the rendition of any person claimed as a fugitive slave under the old Act of Congress of 1793. Yet here was a Massachusetts Judge of Probate sitting as United States Commissioner and doing the work which in the South itself was done by bloodhounds, and by the basest of mankind. I thought I should like to see how such a man looked while engaged upon that task; the more so as he bore a good Massachusetts name; and what kind of a trial a fugitive slave was to have on Massachusetts soil.

Burns was seized on a Wednesday evening, May 24th. He appeared before Judge Loring at nine o'clock Thursday morning, handcuffed, between two policemen. It was obviously intended that the "trial" should begin and end that same morning. Burns had been allowed to see nobody. He had no counsel. When Robert Morris, a coloured lawyer, tried to speak to him the policemen drove him away. By chance, Mr. Richard H. Dana, Jr., and another lawyer of repute, {31} Mr. C. M. Ellis, heard of what was going on, and went to the court-room. Dana intervened, not as counsel, for he had no standing as counsel, but as amicus curiæ, and asked that the hearing be postponed and that Burns be allowed to consult friends and counsel. The black man sat there "stupefied and terrified," as Dana said, incapable of thought or action. After repeated protests by Dana and Ellis, Judge Loring put off the hearing till Saturday. But Burns was still kept in secret confinement. When Wendell Phillips asked to see him to arrange that he should have counsel, the United States Marshal refused. Phillips went to Cambridge to see Judge Loring, and Judge Loring gave him an order of admission to the cell. But he said to Phillips—this Judge-Commissioner said of the cause he was about to try judicially—

"Mr. Phillips, the case is so clear that I do not think you will be justified in placing any obstacle in the way of this man's going back, as he probably will!"

A remark without precedent or successor in Massachusetts jurisprudence, which, before and since, has ever borne an honourable renown for judicial impartiality.

When I went to the Court House on the Saturday it had become a fortress. There were United States Marshals and their deputies, police in great numbers, and United States Marines. The chain had not then been hung about the building nor had Chief Justice Shaw yet crawled beneath it. I was allowed to enter the building, and to {32} go upstairs to the corridor on the first floor, out of which opened the door of the court-room where Burns was being tried, not for his life, but for freedom which was more than life. There I was stopped. The police officer at the door would listen to nothing. The court-room, free by law and by custom to all citizens, was closed by order, as I understood, not of the Commissioner who was holding his slave-court, but by the United States Marshal, who was responsible for the custody of Burns and alarmed by the state of public opinion. While I argued with the police, there came up a smart young officer of United States Marines. He asked what it was all about. I said I was a law student and wished to enter. "Admit him," said the officer of United States Marines. He waited till he saw his order obeyed and the police stand aside from the door; then bowed to me and went his way. So it happened that it was to an officer of an armed force of the United States that I was indebted for the privilege of entering a Massachusetts court-room while a public trial was going on.

Inside they were taking testimony. Mr. Dana and Mr. Ellis were now acting as counsel for Burns, who still seemed "stupefied and terrified." The testimony was only interesting because it concerned the liberty of a human being. Judge Loring sat upon the bench with, at last, an anxious look as if he had begun to realize the storm that was raging outside, and the revolt of Massachusetts against this business of slave-catching {33} by Massachusetts judges. I spoke for a moment with Mr. Dana and then with one or two of the anti-slavery leaders who sat listening to the proceedings. That sealed my fate. When I returned after the adjournment I was again refused admission, and ordered to leave the Court House. When I told the Deputy Marshal I had as much right there as he had and would take no orders from him, he threatened me with arrest. But of this he presently thought better, and finding all protest useless, I went away.

Of the "trial," therefore, I saw and heard little. But of the Faneuil Hall meeting called to protest against the surrender I saw much, though not of the sequel to it in Court Square. Most of the Abolitionist leaders were there, but the Abolitionists at that time would have been lost in the great spaces of Faneuil Hall. The three thousand men who crowded it were the "solid men of Boston," who by this time had begun to think they did not care to see a Virginian slave-holder crack his whip about their ears. The Puritan temper was up. The spirit of Otis and Hancock and Sam Adams burned once more in the hearts of living men. The cheers were incessant; cheers for men who a few days before had been almost outcasts—far outside at any rate, the sacred sphere in which the men of State Street and Beacon Street dwelt. Theodore Parker, who spoke first from a gallery, was cheered, and Phillips was cheered. As the evening drew on, it was evident that violent {34} counsels were likely to prevail. Already there had been, all over the city, talk of a rescue. Parker, ever prone to extreme views, was for it, and made a speech for which he was indicted but of course never tried. The indictment was but a piece of vindictive annoyance. But evidently nothing had been prepared, or, if it had been, these leaders had not been taken into the confidence of the men who meant real business.

Toward the end some one—name unknown—moved that the meeting adjourn to the Revere House to groan Suttle. Parker, who was not chairman, put the motion and declared it carried, as beyond doubt it was, and with wild shouts the vast audience, too closely packed to move quickly, set their faces to the door and began streaming slowly out. Phillips, who was against this plan and against any violence not efficiently organized, came forward on the platform. The few sentences he uttered have never, I think, been re ported or printed, but I can hear them still. At the first note of that clarion voice the surging throng stopped and turned. Said Phillips:

"Let us remember where we are and what we are going to do. You have said that you will vindicate the fame of Massachusetts. Let me tell you that you will never do it by going to the Revere House to-night to attempt the impossible feat of insulting a kidnapper. The zeal that won't keep till to-morrow never will free a slave."

In that single moment, he had recovered his control of the audience. The movement to the {35} doors had stopped. Every one waited for what was coming. Phillips was at his best. He was master of himself and of those before him. The words of entreaty were words of command. He stood and spoke as one having authority.

But just then came a voice from the other end of the hall. It belonged to Mr. Charles L. Swift, the vehement young editor of a weekly paper called The Commonwealth, and it announced that a mob of negroes had attacked the Court House, which had been turned into a gaol, and wanted help to rescue Burns. That dissolved the spell. Faces were again turned to the door. The shouts which Phillips had silenced broke loose once more; and the three thousand citizens of Boston had become a mob. It was all to no purpose. The hall was long in emptying itself: and long before those who were really in earnest could reach the Court House, the ill-advised and ill-planned attack had been made and failed. Colonel Higginson, who, I believe, devised it and led it, had not at that time any experience in measures of war. He had plenty of courage of the hot-headed kind—the kind not then needed. Perhaps Alcott who, after the rush had been made with no success, marched coolly up the steps leading to the door defended by armed police and troops, umbrella in hand, was as much a hero as anybody. But it was all over, I gathered in a few minutes, and the only casualty was the death of a Marshal's deputy, James Batchelder. I had got away from Faneuil Hall as soon as I could, and the distance {36} to the Court House is short, but I arrived too late to see anything but an empty square and that open doorway with a phalanx of defenders inside.

Burns was not rescued. He was surrendered, and no man who saw it ever forgot that shameful spectacle, nor doubted that it was the rendition of Anthony Burns which completed the conversion of the Old Bay State from the pro-slavery to the anti-slavery faith. Webster had held the Puritan conscience in chains for a generation. It revolted, no doubt, at the Seventh of March speech; it was stirred by the Shadrach and Sims cases; but the final emancipation of the State from its long thraldom to the slave power coincided with the surrender of Burns to Suttle. On that Saturday, men saw for themselves, and for the first time, what fugitive slave-hunting in Massachusetts really meant, and what degree of degradation it brought.

The Court House in chains; the Chief Justice stooping to pass beneath them; the streets and squares crowded with State Militia, guarding the entrance to every street on the route; United States Marines in hollow square with Burns and the United States Marshals in the centre; United States troops preceding and United States artillery following. It was fitting that it should be so. The State and the United States were partners in the crime, equal offenders against the moral law, or against the higher law, which till then had been the heritage of the Puritan {37} Commonwealth, and had sometimes been heard of even in Washington. They shared in the guilt and shared in the infamy. Both have since amply atoned for their sin, but nothing, not even a Four Years' Civil War for Union and Freedom, not even the blood of heroes and martyrs, will ever quite wash out from the memory of those who saw it the humiliations of that day. It blistered and burnt and left a scar for ever. This procession took its course in broad daylight down State Street on its way to Long Wharf, where a United States revenue cutter waited to embark the kidnapped slave—kidnapped by process of law—and his master, Suttle. The steps of the Merchants' Exchange were thronged with Lawrences and Fays and Lorings who had been foremost in trying to crush the anti-slavery agitation. But when this column drew near, these friends and servants of the slave-owner and of the cotton trade suddenly remembered that they were men before they were merchants; and men of Massachusetts at that. They broke into groans and cries of execration, and the troops marched past them to the music of hisses and curses. All this I saw and heard. The re-enslavement of Burns was the liberation of Massachusetts. The next time I saw troops in the streets of Boston was in April, 1861, when the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, answering to the call of President Lincoln, started for Washington via Baltimore, with results known to the world.

One more incident. On the Sunday Theodore Parker preached in the Music Hall, then the largest hall in Boston, what he called a sermon on these events. But Parker's sermons were very often like those of Cromwell's colonels; you heard in them the clash of arms, and in this more than in most. He never cared deeply about measuring his words, and he believed in speaking the truth about men as well as things with extreme plainness. On this Sunday he was in his finest Old Testament mood; the messenger of the wrath of the Almighty. He flung open his Bible with the gesture of a man who draws a sword, and in tones that rang like a cry of battle, thundered out his text:

"Exodus xx. 15. 'Thou shalt not steal.'"

The text was itself a sermon. It was the custom in this Music Hall church to applaud when you felt like it, or even to hiss. A deep murmur, which presently swelled into a roar of applause, greeted the text. The face of the preacher was aflame; so were his words as he told the story of this awful week and set in the clear light of truth the acts and words of the Massachusetts Judge who had brought disgrace upon Massachusetts. When he came to the attack on the Court House, the abortive attempt to rescue Burns, and the death of the Marshal's deputy killed at his post, he burst out:

"Edward Greely Loring, I charge you with the murder of James Batchelder. You fired the shot that made his wife a widow and his children {39} orphans. Yours is the guilt. The penalty a righteous God will exact for that life he will demand from you."

To say that, he left his pulpit, which was but a desk on the Music Hall platform, stepped a little to one side, and stood full in view of the great company which had gathered to hear him on this peaceful Sabbath morning; a fair target for another shot had any hearer been minded to try one. You think that a fanciful suggestion? Then you little know the fierceness of the feelings which in those days raged in Boston. They presently grew fiercer, and reached a climax in 1860 and the early winter of 1861; when men on both sides for many months went armed, and were quite ready to use their arms; and when Phillips and Garrison were in daily peril of their lives from assassination and, less frequently but more deadly, from mobs.

Among all that devoted band there was no braver soul than Parker's. He was by profession and training a scholar, a theologian, a man of books and letters, with a rare knowledge of languages and literature, and the best collection of German ballads in America; shelves full of them in his library at the top of his house. But by temperament he was a fighter; as befitted the grandson of that Captain John Parker who commanded the minute men at Lexington, April 19th, 1775. He wrote much, preached often and well, and for twenty years was a great force in Boston and elsewhere. A fiery little man, with {40} a ruddy face and great dome of a head, spectacles over his pale blue eyes, the love of God and of his fellow-men in his heart; and by them beloved.

Richard Henry Dana, Jr., to whose intervention in the Burns case we owe it that Judge Loring was compelled to grant Burns something in the nature of a trial, was a man whom Massachusetts may well be content to remember as one of her representatives for all time. By descent, and in himself, he was a chosen son of that chosen people. His father, Richard Henry, his grandfather, Francis, his great-grandfather, Richard, were all jurists, all patriots, all men of letters. Take one step more, and you come to Daniel, then to Richard again, who, if not quite a voyager to New England in the Mayflower, is heard of as a resident in Cambridge in 1640. Six Danas—nay, five, since our Dana survived his father but three years—span two centuries and a half: from father to son as they took their march down these eventful years, an unbroken line, a race of gentlemen.

It used to be made a reproach to the Dana of whom I write that he was a gentleman. Beyond doubt he deserved the reproach. When a candidate for Congress in 1868 in the Essex district against Ben Butler that eminent warrior called {42} him a kid-gloved aristocrat. "Not even gloved has my hand ever touched his," answered Dana in the heat of a redhot campaign. Butler's rancour lasted to the end, as we shall see.

This, of course, is no biography of Dana. I am writing of what I saw and heard; or not much more. I dealt with the Burns case as a record of personal impressions. But let me quote as an example of Dana's method of statement his account of Burns's arrest. He said to Judge Loring:

Burns was arrested suddenly, on a false pretence, coming home at nightfall from his day's work, and hurried into custody, among strange men, in a strange place, and suddenly, whether claimed rightfully or claimed wrongfully, he saw he was claimed as a slave, and his condition burst upon him in a flood of terror. This was at night. You saw him, sir, the next day, and you remember the state he was then in. You remember his stupefied and terrified condition. You remember his hesitation, his timid glance about the room, even when looking in the mild face of justice. How little your kind words reassured him.

That is the same hand which wrote Two Years Before the Mast—the touch of Defoe, with Defoe's direct simplicity of method and power of getting the effect he wanted by the simplest means; the last word in art, in all arts. Dana was incapable of rhetorical extravagance or of insincerity of any kind. His Two Years Before the Mast is as much a classic in England as at home. One proof of it is the number of pirated editions, before there was an international copyright law. He wrote to me once: "I hear there is a cheap English edition of {43} the book which has had, because of its cheapness, a great circulation. Published, I think, in Hull. Could you send me a copy as a curiosity?" I sent it; a little fat volume with a red cloth cover, much gilt, very closely printed, and sold at a shilling, long before the days of cheap books. It had sold by scores of thousands. It is a book always in print, in one edition or another. Copyright profited Dana no more in America than in England, or not for a long time. Bryant, to whom Dana's father sent the manuscript, hawked it about from one publisher to another in vain, till finally he sold it outright to Harpers for two hundred and fifty dollars, copyright and all. In my copy, with the imprint of James R. Osgood & Co., Boston, is a Preface dated 1869, in which Dana says: "After twenty-eight years the copyright of this book has reverted to me"; and so he presents the first "author's edition" to the public. My copy was a gift from Dana; it is among the treasures I possess and care for most, with this inscription in Dana's clear, quiet handwriting:

My dear Smalley,—Will you accept this volume from me and believe me ever truly yours,

RICH'D H. DANA, JR.

Boston, Feb. 17, 1876.

My real acquaintance with Dana had begun ten years before, when, in June or July, 1866, we crossed the Atlantic together in what was then the crack ship of the Cunard line, the China, the first {44} screw that carried the Cunard flag, capable of fourteen knots. The Cunarders then sailed from Boston, touched at Halifax, and thence steamed to Queenstown direct, and so on to Liverpool. Halifax was an experience; it took us, with all the Cunard seamanship, and there was none better, four hours to get alongside the pier, the currents running I know not how many miles an hour.

The China belonged to the old school; of all new schools the Cunard people, now foremost in everything, had at that time an abhorrence. The saloon aft and tapering to a point, racks over the table filled with table glass, long benches for seats, cabins crowded and dimly lighted with one smoking and smelling oil lamp in a triangular glass case between two cabins; sanitary arrangements unspeakable. I, on my first Atlantic voyage, thought it all the height of luxury; and so it was, for that time. The modern comforts and splendours of sea life date from 1889 with the White Star Teutonic, launched in that year, first of the "floating palaces." The China made her way from Halifax to Queenstown through a continuous fog at undiminished speed. The captain, for an exception among the Cunard captains of those days, regarded a passenger as a human being, and not merely as a parcel to be safely carried from port to port and dumped safely on the wharf, intermediate sufferings of no account. He would answer a question. I asked him, with the audacity of a novice, whether it was safe to steam day and night through a fog at full speed.

"Safe, good God, no."

"Then why do you do it?"

"Why? I will tell you why. First, we have got to get to Queenstown and Liverpool. Second, fogs don't last for ever, and the faster we go the sooner we shall get out of this one. And third, if there's a collision, the vessel going at the greatest speed has the best chance."

So antedating by many years the famous saying of another Cunard captain, summoned to the bridge when a collision seemed imminent, finding the engines reversed, and instantly ordering "full speed ahead"; remarking to the first officer who had reversed the engines: "If there's any running down to be done on this voyage, I propose to do it." But there was none.

When I told Dana of my talk with the China's captain, that experienced seaman and author of The Seaman's Manual observed: "I like a captain to have the courage of his opinions, but not to tell his passengers. Keep it to yourself." And I have kept it for forty years; the captain and ship are gone to Davy Jones's locker. Nothing happened, but something very nearly happened. There had been no chance of an observation since leaving Halifax, and we made the Irish coast rather suddenly, some miles further north than we expected, came near enough to hear the breakers, and swung to the south in safety.

His mind full of sea lore and of sea romance as well, Dana was the most delightful of companions on shipboard. Beneath an exterior which people {46} thought cold, he had a great kindliness of nature. He made no professions; his acts spoke for him. He gave freely of the riches of his mind. He knew England and the ways of the English, and was full of illustrative stories; among them was one of his first visit to the House of Commons.

I heard that night one of the best speeches to which I ever listened: fluent, rich in facts, sound in argument; well phrased and well delivered. I said to myself, "That man must carry the House with him." When he sat down a member rose on the opposite side and spoke for perhaps ten minutes. He stumbled along, hesitated, grew confused, his sentences without beginning or end; nothing but a knowledge of the subject and a great sincerity to recommend him.

But it was perfectly evident that the first speech had no weight with the House, and that the second convinced everybody. The first speaker was Whiteside, a brilliant Irishman and Solicitor-General; the second a county member whose name I never knew. The House thought Whiteside merely an advocate and his speech forensic. His opponent was a man whom everybody trusted. It was character that carried the day. And you will find it generally does with the English.

Dana brought to the study of the law a philosophic mind, and to the trial of causes in court a power of lucid exposition invaluable alike with the Bench and with a jury. The law was to him a body of symmetrical doctrine. He referred everything to principles, the only real foundation for anything. He stood very high at the Bar, for he had learning and would take immense pains, and when he brought a case into court it {47} was a work of art. Moreover, he brought a conscience with it. And he was one of the lawyers, none too numerous, to whom even Chief Justice Shaw listened. Out of many anecdotes I have heard from him I will choose one.

He had defended in the United States Circuit Court a man indicted for aiding in the escape of a fugitive slave. "The case against him," said Dana, "was perfectly clear; there was really no defence; he had beyond a doubt committed the crime of helping rescue a man from slavery. I looked for a conviction as a matter of course. But after the judge had charged the jury, hour after hour went by and still they stayed out. The judge sent for them and asked if they required any further guidance in law or in fact. The foreman said 'No'; but they could not agree, and finally were discharged.

"Some years later," said Dana, "as I stood on the steps of the Parker House, a man came up to me and said, 'You don't remember me, Mr. Dana?' I did not, and he went on:

"'Well, Mr. Dana, I expect you remember trying that case where a man named Tucker was indicted for aiding and abetting in the escape of a fugitive slave. I was on the jury in that case.'

"At this I instantly recalled the facts, and said: 'Since you were on that jury, I wish you would tell me what I have always wanted to know—why they disagreed.'

"'Well, Mr. Dana, I don't mind telling you we {48} stood eleven to one for conviction, and that one obstinate man wouldn't budge. Perhaps you remember it was proved on the trial that the negro was got away from Boston, taken to Concord, New Hampshire, and there was handed over to a man who drove him in a sleigh across the border into Canada.'

"'Oh, yes, I remember that.'

"'Well, Mr. Dana, I was the man who drove him in the sleigh across the border into Canada.'"

I knew something of the preposterous charge against Dana, that in editing Wheaton's International Law he had appropriated the labours of a dull predecessor, Mr. William Beach Lawrence. When President Grant nominated Dana Minister to England in succession to that General Schenck who is still quoted as an authority on poker, the Lawrence charge was pressed before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. It was an ex parte hearing, and Dana had no opportunity to defend himself. Whether that or the unsleeping malignity of General Butler did him the more harm I know not, but President Grant, as his honourable habit was, stood by his nominee; and the Senate rejected Dana by thirty-one votes to seventeen. The matter naturally attracted attention in England, and there were comments, none too just. I wrote a letter to The Times, of which Mr. Delane was then editor. A long letter, something over a column, but Delane published it next morning in his best type, first striking out a number of censorious sentences about Butler {49} and Zach Chandler and other eminent persons who had engineered Dana's defeat. In my wish to do justice to Dana and upon his enemies I had not remembered that I was writing in an English newspaper, and had no business to be rebuking Americans to an English audience. When I read my letter and noted Delane's excisions I saw how wrong I had been, and I wrote to Delane to thank him for suppressing all those ferocities. There came in reply such a note as only Delane would have written.

"It is the first time anybody ever thanked me for using a blue pencil on a correspondent's letter. Thank you."

This was in 1876. Dana's letter to me on my letter about him was characteristic. I think I might print it, but it is with other papers in New York. He was grateful and kindly, but also critical. He was always capable of looking at his own case as if it were a third person's; his mind detached from everything that was personal to himself. He thought the legal points might have been pressed. But the public, especially the English public, will not have too much law. I suppose the Beach-Lawrence suit and the Minister-to-England business troubled Dana more than anything else in his career. He ought, of course, to have been Minister. He would have been such a Minister as Charles Francis Adams was, or as Phelps was, two of the American Ministers whom the English liked best; out of the half-dozen who have held in this country a {50} pre-eminent position among Ministers and Ambassadors, including the present Ambassador and his two immediate predecessors, Hay and Choate. That brilliant list ought to have been enriched with Dana's name; but it was not to be.

Dana came abroad again in 1878, and I saw him once more. He spent his time chiefly in Paris and Rome, and died in Rome, January 7th, 1882. He lies near Keats and Shelley in the Protestant cemetery at Porte Pià; and there is a monument. In Boston he is remembered; whether he is remembered elsewhere I have no means of knowing. But we cannot, in whatever part of America, we cannot afford to forget a man who had all the American virtues in one of the heroic ages of America.

Among the students at Harvard Law School in 1855 was William Emerson, from Staten Island, New York, nephew of Ralph Waldo Emerson. He asked me one day if I would like to know his uncle. I answered that his uncle was the one man whom I most wished to meet, and, with a word of surprise at my fervour, he offered to arrange it.

In these days his surprise may not readily be understood. Emerson has long since taken his place among the Immortals. But at that time his place was still uncertain. The number of his followers was limited; or, as Carlyle said, fourteen years earlier, "Not the great reading public, but only the small thinking public have any questions to ask concerning him." The growth of the thinking mind toward Emerson had, during those fourteen years, been considerable, but it was still, in Matthew Arnold's phrase, only the Remnant to whom Emerson was a prophet or an inspiration. To the majority he was a riddle, and there were not a few of the solid men of Boston who thought him a child of the Devil. The Whigism of Massachusetts had its religious {52} side. To be a good Whig and one of the elect you must be an orthodox Unitarian.

The days when Unitarianism was to be a fashionable religion in Boston were still distant. Emerson was not even a Unitarian; he was an Emersonian. He not only thought for himself, but announced his thought from the housetops; and to think for oneself was, in those conservative days, a dangerous pastime. He came of a race of preachers on both sides, an academic race, six generations of them. For some three years he was himself a preacher, but presently found he could no longer administer the Holy Communion to his congregation, and therefore resumed his place as a layman. The platform superseded the pulpit. His sermons became lectures and essays. He said himself, "My pulpit is the lyceum platform." He became a transcendentalist, as his enemies said, a name he repudiated, preferring to call the transcendental journal he edited The Dial. It was no less an offence to Boston when Emerson's intellectual independence led him into the company of the Abolitionists, though he never wholly identified himself with that rebellious band. His first series of Essays had been published as long ago as 1841, in America, and in the same year in England with a rather patronizing Preface by Carlyle. The second series appeared in 1840, and the Poems in 1846.

In the 'fifties, therefore, Emerson's ideas had had time to become known to those who liked them least. I fell into deep disgrace with a Boston {53} uncle, a lawyer whose office I afterward entered, first as student and then as practitioner, when he heard that I had read Emerson. There was, moreover, an accomplished young lady who asked me if it was true that I believed in Emerson, and then desired to be told what in fact Emerson believed and taught; one of those appalling questions which women sometimes put lightheartedly. I answered as briefly as I could, and she retorted "I think it perfectly horrid." And if that friendship did not come to an end it grew cold, which I then thought a misfortune, and perhaps still do. But society was then intolerant of anything which menaced its foundations, or was thought to. Rightly, I suppose. Since all societies in all ages have wished to live, and not die.

In the Law School we did not discuss Emerson; we ignored him. I can think of no student at that time who had come under his influence. They were busy with the law; what was a prophet to them? If he had readers they kept their reading to themselves. The nephew himself was more a nephew than a disciple. He told me I should find his uncle delightful to know. Presently, to my delight, he brought me an invitation to Concord for Saturday to Monday. We walked the thirteen miles from Cambridge to Emerson's home, arriving in the middle of Saturday afternoon. Photographs have long since made the house familiar, whether in its original state, or after the fire in 1872, and the restoration of it by his fellow townsmen of Concord, and their {54} honourable gift of it to him. A broad gateway led to it from the road, pine trees standing sentinel on either side. Square, with a sloping roof, a porch in the centre, two windows on either side, two stories in height; simple almost to bareness, devoid of architectural pretence, but well proportioned. There was, I think, an ell which ran back from the main building. Inside, your first impression was of spaciousness; the hall and rooms of good size, not very high, and furnished with an eye mainly to comfort; and an easy staircase.

We were taken first into a parlour in the rear of the library which filled one side of the house. Emerson's greeting was something more than courteous—friendly, with a little element of surprise; for though he had long been used to pilgrimages and visits from admiring strangers, to whom his house was a Mecca, there was, perhaps, a novelty in the coming of a law student. A pleasant light, and a strong light, in his fine blue eyes, yet they looked at you in an inquiring, penetrating way as if it was their duty to give an account of you; impartial but sympathetic. You could perceive he was predisposed to think well of people. I had seen Emerson on the platform, but there his attitude was Hebraic: inspired and apostolic. This was the private Emerson, the citizen of Concord, and first of all the host; intent before all things on hospitality. The tall, twisted figure bent toward us, the grasp of the hand was a welcome; the strong face had in it the sunshine of kindliness; the firm lips {55} relaxing into a smile. Delicacy went with his strength, and with the manliness of the man was blended something I can only call feminine, because it was exquisite. Distinction in every line and tone; a man apart from other men. Free from all pretence; of pretence he had no need; he was absolutely himself, and that was all you wanted. There was at first something in his manner you might call shyness or uncertainty, as of a nature which might be embarrassed in unfamiliar company but would go gaily to the stake.

I suppose I am collecting the impressions of this and many later meetings with Emerson, but I cannot distinguish between them, and it does not matter. What was, however, peculiar to this visit was Emerson's almost anxious sense of his duties as host; which seemed not duties, but the inevitable expression of a loving nature. When he heard that we had walked from Cambridge he said we must be tired and hungry and thirsty. We were to sit down there and then, we were to eat and drink. The philosopher bustled gently about, seeking wine and food in the cupboards, and presently putting on the table a decanter of Madeira and a dish of plum cake. He was solicitous that we should partake of both; and to that end set us the example, saying: "I have not walked thirteen miles, but I think I can manage to keep you company at the table." Then he bethought himself that he seldom touched wine; "and indeed I sometimes neither eat nor drink from breakfast to supper." He began at {56} once with questionings about the law school and our way of life and study.

Then to our rooms, plain, pleasant rooms, and then tea in the library. Among the books he seemed more at home than anywhere else; they had been his lifelong friends, for whom he had an affection. He asked again about law and the law school. "A noble study," he said, "one to which you may well devote a great part of your life and mind. As you have chosen it for your profession I am sure you will master it; a man must know his trade or he will do nothing. But law is not everything. It does not perhaps make a demand upon all the resources of the intellect, nor enlarge a man's nature." Which was almost a paraphrase of Burke's famous sentence on the wall in his eulogy on Mr. Grenville:

One of the first and noblest of human sciences; a science which does more to quicken and invigorate the understanding than all the other kinds of learning put together; but it is not apt, except in persons very happily born, to open and to liberalize the mind exactly in the same proportion.

Then Emerson, who seemed always to be seeking the final word, and to condense the whole of his thought into a sentence, added:

"Keep your mind open. Read Plato."