| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/christophercolum00camp |

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Joachim Heinrich Campe

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1911

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1911

Published September, 1911

THE · PLIMPTON · PRESS

[W · D · O]

NORWOOD · MASS · U · S · A

There are five representatives of the Columbus family more or less famous in the history of exploration, viz., Christopher, the discoverer of America; Bartolomeo, brother of Christopher, governor of Isabella and founder of San Domingo; Diego, brother of Christopher, who accompanied him on his second voyage and subsequently entered the priesthood; Diego, son of Christopher, and his successor as governor of Hispaniola; Ferdinand, illegitimate son of Christopher, who accompanied his father on his fourth voyage and became his biographer; and Colon, grandson of Christopher, who was made Duke of Veraqua, Marquis of Jamaica, and Captain-general of Hispaniola; but all of them shine in the reflected light of Christopher, except his brother Bartolomeo, who, while not as skilful a navigator and explorer as his brother, was a great soldier, an experienced administrator, and the principal support of Christopher in his many difficulties and hardships.

The story of Columbus, apart from his discovery of America and his many thrilling adventures in the West Indies, should be one of absorbing interest to youth. It is the story of a man who in his youthful days conceived a vast project, for his time, adhered to it with inflexible resolution though confronted with obstacles which would have discouraged any ordinary man, suffered privations and hardships of the most trying kind, meeting threats against his life, shipwreck, physical ailments, poverty, malicious attacks of bitter enemies, shameful calumnies, the disgrace of being sent to Spain in fetters by Bobadilla, his jealous and cruel rival, and the ingratitude and dishonesty of the King of Spain, and yet accomplished a purpose even greater than that which first inspired him, for he died not knowing that he had discovered a new continent. He supposed to the last that the region he had found was the East Indies. The great navigator, seaman, and explorer passed his last days in poverty and neglect, and the rewards which the King had promised were enjoyed not by him but by his son Diego. But his fame is immortal.

G. P. U.

Chicago, July, 1911.

The ancient Greeks were not the only nation which imagined there was a region in the Atlantic Ocean, an island beyond the Pillars of Hercules, the sea highway, now called the Straits of Gibraltar. The traditions of other people tell of a land where only happy mortals dwell. Greek poetry assigned this region to the ocean, which was supposed to surround the world as it was known at that time. The Romans also believed in this distant western land, and in the Christian Middle Ages these same traditions were carefully preserved. It was told that many an adventurer sought these Islands of the Blest but never returned home.

The seafarers of the Middle Ages must have been timid navigators for they never reached the open sea but contented themselves with cruising along its shore. At last the Genoese and Venetians, whose cities were very prosperous in the fourteenth century, because of their expanding commerce, ventured out of the Straits of Gibraltar. Their course, however, was not southward but north of the straits which connect the Mediterranean Sea with the ocean, for it is well known that the Venetians in 1318 reached Antwerp by vessel.

Simultaneously with these efforts of the Italians to reach the north, the Portuguese were striving to discover a passage to the rich Indies in vessels manned almost entirely by Italian sailors. The Genoese also undertook independent voyages of discovery. Two ships which passed through the Straits of Gibraltar at the close of the thirteenth century never came back. A Genoese expedition at the beginning of the fourteenth century discovered the Canary Islands, but the explorers declared they were not the Islands of the Blest. Before the year 1335 a Portuguese vessel returned to Lisbon from the Canaries with products of the soil and kidnapped natives. In July, 1341, two large and well armed vessels, under command of a Genoese and a Florentine, reached the Canaries in five days from Lisbon. They held possession of the islands until November. It is also known that Europeans stopped for some time at Teneriffe,[1] where they found almost naked but fierce natives who lived in stone houses, tilled the soil, and worshipped idols. About the close of the fourteenth century thirteen friars attempted the conversion of the natives of the larger Canaries but were massacred by the savages.

About this time the islands of Madeira and the Azores were discovered but they were uninhabited. The Canaries alone had inhabitants, called Guanches.[2] These Guanches lived upon seven islands, but, as there were no means of communication between them, they knew little of each other. Their dialects indeed were so different that they could not understand one another. Wheat and barley were cultivated. The natives on the islands of Gomera and Palma went naked, lived in caves, and subsisted upon roots and goats’ milk, and were dangerous enemies with their stone weapons and horn-tipped spears. The natives on the larger Canaries were the most civilized and had two large cities and thirty-three communities. Their two kings were at constant variance. The warlike Guanches were only subjugated after fierce encounters, for they climbed with the ease of goats and were such fleet runners that they could overtake the hare. When asked about their origin, they replied: “After the submission of our ancestors the gods placed us in these islands, left us here, and forgot us.”

Remarkable success crowned the explorations of the Portuguese owing to the enterprise and zeal of the Infante, Henry,[3] third son of King John the First, who was surnamed by posterity “The Navigator.” His lean, angular person hardly bespoke his real greatness. His perseverance and indomitable resolution were apparent alone in his clear, open look. He was a man of great abstemiousness. Wine never passed his lips. He spent his revenues upon exploration and conquests on the west coast of Africa. The voyages of the Portuguese discoverers began in the Autumn of 1415 but the first navigators returned after reaching Cape Bajador, for they dared not venture out into the open sea because of the breakers and dangerous ledges. Four years later two explorers, driven out to sea by a storm, reached the island of Porto Santo, previously discovered by the Italians, and from there went to Madeira, or the “Forest Island,” as it was called. It was not until 1434 that Cape Bajador was circumnavigated by a daring man who had offended the Infante and by this exploit regained his favor. He brought back flowers in earthen vessels to prove that floral beauty was not lacking on the other side of the dreaded cape.

Further attempts were made in succeeding years. The Portuguese continually advanced and once brought home fish nets which they had taken from the natives to prove that the lands beyond the Cape were inhabited. Soon they penetrated to regions where they found gold-dust and other valuable products, which were taken in honor of the Infante. In consideration of the tremendous expense and the incalculable exertion involved in these voyages the matter of profit was alone taken into account. Naturally no heed was paid to their scientific importance. Explorations beyond the Cape at last proved very profitable and many vessels returned with large cargoes of slaves, for Europeans at that time were not ashamed of man-stealing. They hunted their human victims openly and even used dogs to run down their prey. Slavery was not abhorrent to them. They thought it natural that God should reward their man-stealing with success. A chronicle of the year 1444 says: “At last it pleased God to compensate them for their great suffering in His service with a glorious day’s efforts, for altogether, in men, women, and children, they captured one hundred and sixty-five head.”

An important discovery in the year 1445 removed many erroneous conceptions. Dinas Diaz in that year sailed farther south than any navigator had gone before. He passed Cape Blanco, reached the southern line of the Great Desert, and found a region green with palms, and people with black skins. The spot he discovered was called the “Green Cape.” He proved that the theory that the tropics were uninhabitable was false. Aristotle had maintained that the tropical regions must be unpeopled because the overpowering heat of the sun’s rays would destroy all vegetation. Other scholars, among them Ptolemy, were of the same opinion. The theory indeed was so universally accepted at the beginning of the fifteenth century that many a bold adventurer was deterred from making explorations in that direction.

In the same year, however, the Senegal, which Diaz had passed unobserved, was discovered on a second voyage. The river was declared to be a branch of the Egyptian Nile. In the following year the Portuguese met with a serious disaster on the African coast. Two vessels, owing to the misplaced confidence of their commanders in the negroes, ventured too near and were greeted by a shower of poisoned arrows. The wounded explorers died after reaching Lisbon, two months later, without having seen anything but sky and water. This disaster, however, did not deter other brave navigators from undertaking further explorations beyond the Green Cape, though they dreaded the poisoned arrows of the natives more than any hardships or perils of the sea.

About this time the Azores were colonized by the Portuguese, for these islands had been so little disturbed by man that even the birds could easily be taken by the hand. Henry, the Infante, bestowed the islands upon the explorers as an hereditary tenure.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, during the reign of Alfonso the Fifth, we have very inadequate reports of the progress of Portuguese exploration. We know, however, that the explorers advanced along the rivers of West Africa, especially the Gambia, which stream they ascended to transact business with caravans from the Soudan. It was at that time the European world began traffic in the great and rich resources of Central Africa. On the thirteenth of November, 1460, the Infante died, and the prosperity which had attended Portuguese explorations languished. History has honored him with the surname “Navigator,” though he took no personal part in exploration. Under his encouragement, the Portuguese, who before his time had timidly returned home from Cape Bajador, became bold seafarers. Discoveries rapidly advanced in his lifetime but Alfonso the Fifth wasted his inheritance. He gave no thought to new explorations for those already made were yielding him rich returns. The sugar plantations in Madeira brought him large profits, slaves were exchanged for horses, and the coast supplied great store of gold-dust, musk, ivory, and ginger. Notwithstanding their discouragement, the explorers pushed farther south. Before the close of the fifteenth century they found the Zaira, the Congo of our maps. King John the Second, like “Navigator” Henry, was greatly interested in sea voyages and the sciences. Under his patronage Bartholomew Dias, in 1486, left Lisbon with two small vessels and a supply boat, sailed south, and passed the mouth of the Congo. As the wind was contrary he put out to sea but was so driven about by storms that at last he found the coast of Africa on his left. He had rounded the southern extremity of the Dark Continent and, finding land, he kept on in a northerly direction.[4] His sailors, however, refused to go farther and insisted he should return. As he could not conciliate them, he began the home voyage reluctantly, passing again the mysterious cape, which he named Tormentoso, the name being subsequently changed by John the Second to Good Hope, and reached Lisbon in December, 1487, after an absence of sixteen months and seventeen days. Dias was poorly rewarded for his great discovery. He was not given command of a fleet a second time, but served as a simple captain under Cabral,[5] the discoverer of Brazil, and, in rounding the Cape of Good Hope during a fearful storm, May 23, 1500, was drowned.

Even before Dias had found the Cape of Good Hope an Italian explorer, named Cristoforo Colombo, appeared at the court of John the Second. When subsequently he made Spain his home, he was called Colon.[6] He is best known by his Latin name, Columbus. This extraordinary man was born at Genoa in the year 1456.[7] Genoese contemporaries assure us his father, Domenico, was a wool-comber. Domenico had four children: three sons, Cristoforo, Bartolomeo, and Giacomo (Diego),[8] and one daughter, of whom it is only known that she married an Italian innkeeper. From his earliest youth Christopher loved the sea. As a lad he showed promise of being a skilful sailor and brave man. He was active and courageous, had no delight in indolence or effeminate luxuries, and despised all delicacies which tickle the palate and weaken the health. His highest ambition was to secure all the knowledge he could so as to be of some service to his fellow men. In a short time he learned the Latin language, in which all the scientific books of the time were written, and, although a boy in those days could learn but very little of the sciences, compared with what can be done to-day, yet he acquired sufficient knowledge of them to become an authority. His father, who was comfortably well off, sent him to the University of Pavia where he studied geography, geometry, astronomy, and drawing. At fourteen he had made such advances that he was qualified to become a ship captain and go to sea. He exerted his utmost effort to investigate the ocean and its routes. The saying, “as the twig is bent, the tree’s inclined,” well applies to him. He determined to become a great seafarer and from his earliest youth adhered to the determination until it was fully realized.

Our young hero had his first experience in the Mediterranean Sea, for the voyages of his people at that time did not extend farther. It was much too confined a sphere, however, for a spirit which burned with the desire to accomplish unprecedented achievements. After a voyage to the northern ocean, during which he reached Iceland and gathered valuable experience, he entered the service of a kinsman, a sea-captain, who had fitted out a few vessels at his own expense, with which he cruised at one time against the Venetians, at another against the Turks, seeking to capture their galleys. Upon one of their cruises, the young Columbus would have lost his life had not Providence preserved it for high purposes. In a stubborn fight with the Venetians, in which our young hero performed prodigies of valor, his ship as well as those with which it was engaged took fire. Columbus found himself in a desperate situation but even with death staring him in the face he had no fear. He boldly plunged into the sea, clutched a floating oar, and with its help swam safely to the shore, two miles distant. He landed upon the Portuguese coast and, as soon as he had rested, made his way to Lisbon.

This event had a marked influence upon his future career, for in the Portuguese capital his knowledge and ability were of great service in securing friends among seafarers, with whom plans were discussed for the discovery of a passage to the East Indies. An event soon happened which greatly promoted the ambitious purpose of his life. He married Felipa Perestrelli, daughter of a sea-captain, one of the early colonists and first governor of Porto Santo. This gave him possession of the diaries and charts of his experienced father-in-law, and as he studied them day and night his desire to visit these newly discovered islands grew stronger. He once more went on shipboard, made a voyage to Madeira, and for some time carried on a lucrative business, visiting the Canaries, the African coast, and the Azores in the meantime.

During the short voyages which Columbus made from the Canary Islands he was still busy with the great scheme upon which he was engaged in Lisbon. He often said to himself: “There must be a nearer route by sea to the Indies than that attempted by the Portuguese. If one sails from here across the ocean in a westerly direction he must at last reach a country which is either India or some region adjacent to it. Is not the earth round? And if round, must not God have created countries upon the other side of it, upon which men and other creatures live? Is it at all likely that the whole hemisphere is covered by the ocean? No! No! India certainly is a vaster region than people believe. It must stretch far from the east toward Europe. Then if one sails straight to the west he must eventually reach it.” This was not his only reasoning. Several other considerations strengthened his belief and this one among them: A Portuguese navigator once, sailing far to the west, found curiously wrought sticks floating in the sea, which came from the westward. This fact convinced him there must be an inhabited country in that direction. Columbus’ father-in-law, on one of his voyages, found similar sticks which had been driven by the west winds. Felled trees of a kind unknown there had been found on the west shores of the Azores, evidently blown there by west winds. The bodies of two men had been washed ashore on these same coasts, with strange, broad faces, evidently not Europeans, and unlike the people of Asia and Africa.

Columbus carefully gathered all these facts, pondered over them day and night, and, after comparing with them such information as he found in old as well as contemporary authors, became thoroughly convinced that his theories were correct. He remembered, however, that “to err is human” and that four eyes are better than two. Thinking it unwise to rely upon his own opinions alone, he consulted a man whose learning and wisdom made his advice of the highest value. This was Toscanelli, a Florentine physician, born in 1397. He was very old at this time, but he had already declared his belief to Alfonso the Fifth that a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to the East Indies was perfectly practical, and had sent a chart to Lisbon upon which the distance and choice of routes was traced. Toscanelli approved the scheme of Columbus and not only gave him much valuable advice but urged him to put his plans in operation as soon as possible.

Columbus was now fully determined to set about his work but he needed assistance in his preparations. Some government must help him and to which one should he give the preference? He promptly decided that his own dear fatherland should participate in the honor of his discoveries. He submitted his scheme to the Genoese Council and asked for the necessary assistance. The Council, however, attached no importance to it, regarded him as an inexperienced man, and rejected his proposals. He was discouraged by its decision but, feeling that he had at least performed his duty to his fatherland, he went to Lisbon to submit his plans to the Court, which at this time was more friendly to expeditions than any other. He waited upon King John the Second and asked permission of him and his Council to carry out the scheme upon which he had been engaged so many years. His proposition was favorably considered but subsequently his plan was stolen little by little and he found himself the victim of most despicable treachery. The Portuguese hastily fitted up a vessel and placed it in command of another leader, who sailed away on Columbus’ course; but he had neither the latter’s skill nor courage and, after a short western voyage, abandoned the undertaking as hopeless and returned to Lisbon. Indignant at such treachery, Columbus forsook a Court which had treated him so meanly and went with his son, Diego, to Madrid. As his wife had died some time before this he never returned to Lisbon. Fearing possibly that his scheme might not be accepted at the Spanish Court, he sent his brother Bartolomeo, who was familiar with all the details of his plan, to England, to ascertain whether he could expect help in that quarter.

Ferdinand of Arragon was the ruler of Spain at this time (1484). His cautious and suspicious nature led him to regard with disfavor any scheme which was in the least doubtful. His consort, Isabella of Castile, was much bolder, but she depended entirely upon her husband and would not engage in anything that met with his disapproval. Unfortunately also at this time the King was at war with the Moors, who were in power at Grenada. Under such circumstances what could Columbus expect from the King? Eventually he was hospitably received by Ferdinand and Isabella and was listened to attentively. Before making a decision one way or the other, however, the King decided to submit the scheme to other advisers who unfortunately had not sufficient knowledge to examine it intelligently. They interposed silly objections. One maintained that the ocean between Europe and the Indies was so immeasurably vast that even the most favorable voyage from Europe to the nearest land would take at least three years. Another, in view of the roundness of the earth, insisted that one sailing west would be going down hill and that when he wished to return he would have to come up hill, which would be impossible, however propitious the wind might be. Others were insolent enough to ask him whether he imagined he was the only wise man among the millions of the world, and, if there really was land on the other side, how it happened that it had remained unknown for centuries.

Columbus needed all his resolution and patience to endure the ignorance and insolence of his critics, but he retained his composure and answered each foolish objection seriously. But of what avail was it? After striving in vain for five years to convince these and other ignoramuses that his scheme was feasible, he had the added mortification of learning that the King sided with them. He received from the Court the unfavorable reply that so long as the war with the Moors continued the King could not consider any other undertaking. Columbus, of course, was disappointed and had lost much valuable time, but he steadfastly adhered to his purpose. Far from abandoning it, he applied to two Spanish dukes[9] who were wealthy enough to fit up a small exploring squadron. They were lacking, however, in faith and courage and did not care to engage in a scheme which was too expensive for the King. Columbus was again disappointed but concealed his vexation and, without wasting any more time on useless applications, made preparations to bid farewell to Spain (1491) and go to the King of France from whom he had received an encouraging letter while at the Spanish Court. He started for that country with his son Diego. Arrived at the flourishing seaport of Palos[10] he knocked at the door of a Franciscan monastery[11] and asked the doorkeeper for bread and water for his exhausted son. The learned Brother, Juan Perez de Marchena, guardian of the monastery, who was father confessor to the Queen, observed the wanderers. He entered into conversation with Columbus, who acquainted him in a most interesting manner with his plans and his misfortunes. The Brother listened to his statements with eager attention, believed his scheme reasonable, and urged him to remain until he could write to the Queen and receive her reply.

Columbus assented. The Brother wrote the letter and made such a convincing statement as to the feasibility of the scheme that Isabella suddenly changed her mind and wrote a reply, urging Columbus to return to the Court. The sorely tried and much disappointed man took heart again and obeyed the Queen’s summons. Isabella received him graciously and expressed the hope that his scheme would prove successful; but, alas, the timid, wavering King marred all. He called the same ignoramuses in council again and, as they made the same report, he would hear nothing of western voyages and notified Isabella to break off the intercourse with Columbus.

Columbus’ spirit, however, was stronger than that of his enemies. He roused himself anew and was making preparations to go to England and offer her King the great reward which three governments had contemptuously refused, when the news came that the Moors had been vanquished and their power in Spain ended. Ferdinand and Isabella were delighted with the outcome of the struggle which made them rulers of all Spain. Two friends of Columbus took advantage of the situation to urge his scheme upon the Queen’s consideration and convince her that the royal authority would be greatly extended by it. Owing to the zeal and enthusiasm with which they espoused his cause, the King and Queen at last decided to make no further opposition. A messenger was despatched to Columbus and he was brought back in triumph to the Court, where the Queen impatiently awaited him. Forgetting all his sickening disappointments and blighted hopes, Columbus submitted his terms and when they were finally accepted he felt that at last his dearest wishes were realized. He asked for himself and his heirs elevation to the nobility, the rank of admiral, the authority of vice-royalty over all he should discover, and a tenth of all gains by conquest in trade.

COLUMBUS PLANNING THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA

It is not strange the King was reluctant to give up any part of such valuable revenues and to concede such important privileges, especially as the new country might be larger than the mother country, and the representative of the King more powerful than the King himself—but Isabella was fully determined to recognize Columbus’ undertaking and would not listen to any objections. She said: “I will pledge my crown of Castile for the success of this scheme and my jewels also if sufficient money is not raised to carry it out.”

Columbus was overjoyed at the success which at last crowned his efforts and at once began actively fitting out the necessary vessels. Those which the King placed at his disposal were so small and poorly built that no man but Columbus would have trusted himself in them upon a vast, unknown sea whose dangerous spots were uncharted. The vessel which he commanded was named the Santa Maria; the second, the Pinta; and the third, the Nina. The last two were hardly larger than good-sized boats. The little squadron was provided with subsistence for twelve months and ninety men.[12] The cost of the expedition was not more than 5300 ducats, a sum which at that time seemed so large to the impoverished Court that the whole undertaking might have been abandoned had it not been that the citizens of Palos provided two of the vessels, the King sending only one. At last all the preparations were made and the vessels lay at their anchors ready to sail.

Before weighing anchor, however, Columbus considered it a duty to invoke the favor of the Creator of the ocean, the Creator and Ruler of all the earth, for the expedition which he had so much at heart, for it was also his purpose to spread the knowledge of the only true God in the ignorant wilderness whither Divine Providence was to conduct him. Accompanied by all his companions, Columbus went in solemn procession to a monastery in the vicinity of Palos and there publicly implored divine help, his seamen following his pious example. Then they returned, full of confidence in the Most High. The next morning, August 3, 1492, they set sail in God’s name amid the cheers of a great multitude of spectators. Columbus commanded the larger vessel, the Santa Maria, and the two brothers, Martin and Vicente Pinzon, the two smaller vessels.

According to Columbus’ plans the fleet was to sail first to the Canaries, but on the second day out a slight accident happened which might have ruined the expedition if Columbus had been as weak as his superstitious comrades. The rudder of the Pinta was broken, purposely, it is believed, by the helmsman, who was afraid of the voyage and hoped in this manner to force Columbus to go back. The crew declared that the accident foretold disaster. “We shall be lost,” they shouted, “if we do not go back at once.”

“But why?” asked Columbus.

“Why?” they replied. “Heaven has already shown clearly enough by this broken rudder that it will be disastrous if we do not abandon the undertaking at once.”

“I really do not know,” answered Columbus, “how you have learned that this unexpected event is a sign of coming disaster. So far as I know, a broken rudder only means that we must mend it.”

“The Admiral is a freethinker,” the seamen whispered to each other; “he does not believe in signs.”

Columbus, who knew their thoughts, realized the necessity of overcoming as far as possible the superstition of his ignorant companions, as a hundred opportunities might occur for similar outbreaks. He explained the matter to them in detail and showed them how unreasonable it was to regard it as a sign of future disaster, for God had never promised He would make the future known by signs. Wisely and mercifully Heaven had concealed the future from us. Therefore it was useless and foolish to expect disaster because of any sign. All that a wise and pious man could do was to perform his duties faithfully and industriously all his days, trusting in divine oversight and having no fear of the future. “Let this be the rule to govern us throughout our voyage,” said he. By representations of this kind Columbus, although he could not entirely remove their superstitious fears, rendered them less dangerous. Nothing further of particular consequence happened and at last they came to anchor at the Canary Islands. There the necessary repairs were made and on the sixth of September they weighed anchor and started upon their great western voyage over the uncharted sea.

Little progress was made the first day, as they were becalmed, but on the second, some say the third, the Canaries disappeared from view. They were hardly out of sight of land when the seamen began to lose courage. They wept, beat their breasts, and cried aloud as if they were going to instant destruction. Columbus stood steadfast as a rock in the ocean, undisturbed by their deafening wails, and showing such composure and confidence that the cowards plucked up a little courage. He made them ashamed of their weakness, and so clearly explained to them the honor and profit which they would receive at the end of the voyage that all were inspired by his words and promised to follow wherever he should lead.

Columbus devoted most of his time on the deck of his vessel to the plummet and instruments of observation. The plummet, a heavy piece of lead, attached to a long rope, was let down into the water to ascertain its depth, and thus avoid the danger of stranding. The exact location of the vessel at any given time was ascertained in Columbus’ day by the astrolabe,[13] with the help of the location of the stars and their distance from each other. To-day mariners have much more perfect instruments for observation. Columbus made all his measurements and observations himself. He gave only a few hours to sleep and rest, in the meantime exhibiting such composure as to impress even the weakest of his sailors with confidence in him and his undertaking. Only to such a man was this great task possible. In the hands of a man of less courage, foresight, and ability it must have failed.

On the second day after leaving the Canary Islands they made but eighteen miles, owing to light winds. As Columbus foresaw that nothing would intimidate his ignorant crew so much as the length of the voyage, he decided to play an innocent trick upon them by keeping one reckoning of distance for himself and another for them. He told them therefore that they had sailed only the first fifteen miles westward.

On the twelfth of September, six days after their departure, they had sailed one hundred and fifty miles to the west of the Canary Island of Ferro. On that day they observed the trunk of a great tree which evidently had been drifting about a long time. The sailors took it for a sign that land was not far distant and felt much encouraged, but the encouragement did not last long, for after sailing about fifteen miles farther a strange thing happened which astonished them all and even excited the wondering Columbus—the compass needle, which had steadily pointed to the pole star, changed a whole degree to the west from its customary direction. The phenomenon was new to Columbus, as well as to his sailors. The latter were greatly excited and declared the earth was out of joint, for the needle no longer pointed right. The distance which they had traversed already seemed to them endless although their leader insisted that he was not a third of a mile out of his reckoning, but now all seemed hopeless since the needle, their only guide, had abandoned them. Columbus, whose ingenuity in discovering methods of reassuring his weak companions was inexhaustible, invented a plausible reason for this unexpected phenomenon which quieted them though it was far from being satisfactory to himself. In an ingenious manner he altered the action of the compass so that the needle pointed right again.

Hardly had the crew recovered from this shock before a new trouble arose. They had come to the region of the trade-winds, which were unknown at that time. They shuddered as they thought that if these winds continued to blow they might never reach home again. One unfortunate thing followed another. On the sixteenth of September their fear was greatly increased. They suddenly observed that the ocean, as far as the eye could reach, was covered so completely with a green weed that it seemed as if they were sailing over a vast meadow.[14] In some places it was so thick they could hardly make their way through it. The sailors said to themselves, “We have come to the end of the navigable ocean. Under this sea-weed there must be reefs and shallows which will wreck our vessels. Why should we, wretched unfortunates, longer consent to follow this foolhardy leader?” Columbus again quieted them and inspired fresh hope. He said to them, “Why should you be troubled about a matter which shows that we are now approaching the wished-for goal? Does not vegetation grow by the sea? Is it not certain that we are not far from the shores where this sea-weed grew?”

The crew was greatly encouraged by his words, especially as at the same time various birds were seen flying to the west. Fear changed to hope again and so they sailed on once more with glad anticipation of a fortunate end to their undertaking.

The hope which the floating sea-weed and the flight of birds had aroused among the seamen soon vanished, for, although they had now sailed seven hundred and seventy miles to the west, no land had yet been seen. Fortunately no one except the Admiral knew how to calculate the distance. Columbus continued to conceal a considerable part of it and announced that they had sailed five hundred and fifty miles.

But even this distance from the fatherland seemed much too long to them. They began anew to sigh and groan and murmur, lamented their credulity in accepting Columbus’ idle assurances, and uttered bitter reproaches against Queen Isabella for having allowed them to risk their lives in such a foolhardy venture. They resolved that now was the time for them to return, in case the incessant east wind did not render it impossible, and that their leader must be compelled to abandon his scheme. The boldest among them even advised throwing him overboard, thereby ridding themselves of such a dangerous leader, and assured the others that upon their return to Spain a thorough investigation would justify them for the death of a man who had toyed with the lives of so many.

Columbus realized the danger hanging over him but was not alarmed. Conscious of the overwhelming importance of his plans and confiding in the protection of the Almighty, he appeared among his sailors like one inspired with success. With gentle earnestness he rebuked them for their conduct and sought in every way his knowledge of human nature suggested to rouse their hopes and courage anew. At one time he reminded them of their duty by cordial and flattering appeals; at another he displayed the masterful authority of a leader and threatened them with the displeasure of the Queen, as well as the severest penalties, if they dared to hold back when so near the successful result of a glorious achievement.

It is the prerogative of great spirits to bend the hearts of weaker and ordinary men like wax. He succeeded in quieting his companions, and the heavens themselves aided him. The wind, which hitherto had been persistently east, changed to the southwest, so that return was impossible even if they attempted to carry out their purpose. The Admiral called their attention to this and, as many other signs of land appeared, fresh hope was awakened and they sailed on once more in the name of God.

On the twenty-fifth of September Martin Alonzo Pinzon, commander of the Pinta, which was in the lead, came alongside of the Admiral’s vessel and informed him he believed land was only about fifteen miles away to the north. At the word “land” the greatest excitement prevailed. They thanked God by singing a Gloria in Excelsis and begged the Admiral to change his course and sail to the northward. But Columbus was convinced Pinzon was in error and would not change. He persisted in carrying out his plan to keep steadily to the west and the result proved he was correct.

On the following day a multitude of birds were seen, which convinced Columbus that they had not flown far and that they were evidences of the land he was rapidly approaching. The plummet, however, indicated a depth of two hundred fathoms which conflicted with his conviction, for the depth of the sea should diminish with approach to shore. On the following evening singing birds lit on the masts, remaining there all night, and flying toward the west at daybreak. Shortly after this they saw a new and remarkable sight—a school of flying-fish skimming the surface of the water. Some of them fell upon the decks and were picked up by the seamen, who curiously noted the long fins which answer for wings. On the same day the sea was covered with weeds, another hopeful sign that land was near. But the goal seemed to recede day by day, and the higher their expectations were raised the greater was their disappointment in not realizing them. The spirit of unrest and even mutiny broke out anew on all three vessels, and even the officers sided with the crews against the Admiral.

Threatened upon every side and forsaken by all, Columbus stood amidst the tumult of his excited companions like a lone oak in the tempest and composedly faced the fury of the mutineers who desired his death, or, what was tenfold worse than death, the abandonment of his project. Once more he employed every resource to quiet them but it was useless. They cursed him and threatened death if he did not at once return to the fatherland. In these desperate circumstances he at last realized the necessity of compromising with them. Accordingly he promised that he would yield to their demands if they would obey his orders three days longer. Should he not discover land by that time he would take them back to Spain. Great as was their anger against their leader, they had to acknowledge the fairness of the proposition and the agreement was made.

In the meantime Columbus was certain that he could not lose, for the signs of land were so numerous he was confident he should reach it by the end of the stipulated time. For several days the plummet had shown decreasing depth and the kind of earth it brought up could only come from the near land. Whole flocks of birds, which were not capable of long flights, flew to the west. Floating branches covered with fresh red berries were observed, the air grew milder, and the wind, especially at night, was very changeable. So assured was the Admiral now of success that on the following evening he reminded the crew of their duty of gratitude to God for their protection on this dangerous voyage, and ordered that they should lay to, as he was anxious not to make a landing at night. He also reminded them of the Queen’s promise of a bounty of ten thousand maravedis to the one who first discovered land, and promised to add a like sum to it. The crew remained on deck all night watching with anxiously beating hearts for a sight of land.

It was two hours before midnight when Columbus, standing on the quarter-deck, thought that he saw a light in the distance. He called one of the royal pages and pointed it out to him as well as to another who accompanied him. All three noticed that the light moved from one place to another and they decided it must be carried by some traveller. Columbus was so delighted with this certain proof that his great journey was at an end that he did not close his eyes that night.

About two hours after midnight on Friday, October 12, the loud shout of “Land, land!” was sent up on the Pinta, which was in the advance, and all hearts were rejoiced. Between fear and hope they waited for the dawn to convince them it was not a dream. Every minute seemed an hour, every hour a day. At last the eastern sky began to glow. The sun rose in splendor and all together the crew of the Pinta with joyous voices sang, “Lord, God, we praise Thee.” Those on the other vessels joined with them in their thankful outburst as the long-looked-for land lay before their eyes.

IN SIGHT OF THE NEW WORLD

Hardly had the song of gratitude ended when they bethought themselves of the duty they owed their commander. With overflowing hearts and tearful eyes they prostrated themselves at his feet and implored his pardon. Wonderful as his steadfastness had been when confronting their fury, still more wonderful was his composure as he overlooked their behavior and promised to forget it.

Columbus first landed upon one of the islands commonly known as the Bahamas.[15] One of them is called Guanahani, and this is the one first discovered. Columbus named it San Salvador, the Island of Deliverance, but it is no longer known by that name. The delighted mariners stood for some time and gazed with astonished eyes at a part of the world they had never seen before, now brightly illuminated by the rising sun. They could hardly satisfy themselves with the sight of this smiling, fruitful land, interspersed with beautiful forests and gracefully winding streams. Columbus ordered the boats lowered and, stepping into one, was rowed ashore, with banners flying, to the sound of martial music, followed by his leaders and an armed force. As they neared the shore they observed a great crowd of natives, who gazed with surprise at the European vessels lying together off the beach. When they reached land, Columbus, richly clad, with drawn sword in hand, was the first to step upon the soil of the New World discovered by him. His companions knelt, kissed the ground, and, still kneeling, vowed obedience to their great leader, now Vice-king of the new country. After this expression of their joy they set up a crucifix on the shore and, kneeling before it, offered thanks to God for His mercy. Then with the customary ceremonial they took possession in the name of the King and Queen of Spain.

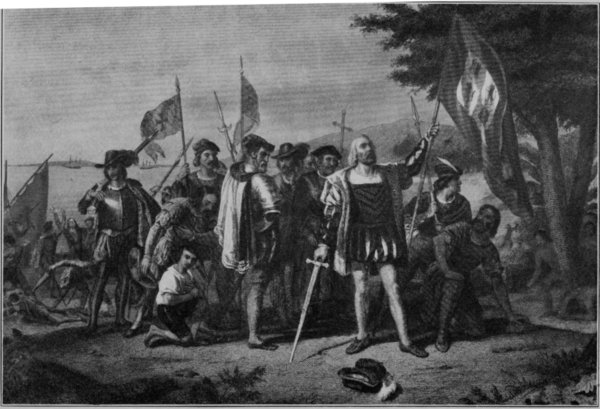

LANDING OF COLUMBUS

During these ceremonies the natives crowded around the Spaniards, gazing in mute astonishment now upon the vessels and again upon the extraordinary beings who had come from them. They saw but knew not what they were seeing, for of all the ceremonies going on before their eyes they understood not one. Had these poor creatures known what was in store for them they would have filled the air with lamentations or have shed their innocent blood in defending themselves against these strangers whom they now regarded with admiration and awe. The longer they stood and gazed the more incomprehensible was everything they saw and heard. The white faces of the Europeans, their beards, their costume, their weapons, and their actions were strange to them. As they heard the roar of cannon and rattle of musketry they huddled together as if seeking shelter from a thunder storm. They thought that these strangers, armed with thunder and lightning, were not human but superhuman beings, children of their divinity, the sun, who had condescended to visit the earth. Some of them regarded the sun, the all-animating, mighty, and beneficent orb, as God himself. Others believed in many deities with human figures, and the rest were so weak mentally that they had no idea of the origin of the world and no knowledge of its daily phenomena. These poor creatures knew nothing of a God and lived in ignorance of whence they came or of what was to become of them. The Spaniards in their turn were as greatly astonished at what they beheld as the natives. The shrubs, plants, and trees were totally unlike those of Europe. The natives seemed to be of an entirely different race from them in their physical appearance and manner of life. They were of a dark copper color, their hair was black and long, their chins beardless, their stature medium, their features strange and peculiar, their manner gentle, and their bodies strangely marked and painted. Some were almost—others completely—naked, except that they wore ornaments of feathers, shells, and disks of gold in their ears and noses and upon their heads. At first they were afraid, but after a little, when they were given presents of beads, ribbons, and other trifles, they felt so much confidence in their celestial guests that toward evening, when the Spaniards returned to their vessels, many of them accompanied them in little canoes, hollowed out of the trunks of trees, some to gratify their curiosity still further, others to exchange gifts. They gave the Spaniards cotton yarn, which they were skilled in making, arrows with tips made of fish bone, fruits, and parrots of various kinds. They were so eager to get the European trifles that they gathered the pieces of broken knick-knacks lying upon the deck and gladly exchanged twenty-five pounds of cotton yarn for a couple of copper coins which were of no use to them. The novelty of these articles and the fact that they belonged to the white people invested them with great value in their esteem.

On the next day Columbus went ashore again, everywhere followed by the natives. He was specially anxious to find out where the gold came from. They assured him it was not on their island but farther south. He decided to act upon this information, for he had assured the King of Spain and his avaricious Court that his discoveries would enrich them. Consequently he went on board again, took seven natives with him as guides, and sailed southward. He observed several new islands but visited only the three largest, which he named Santa Maria del Concepcion, Ferdinand, and Isabella. But he found no gold there. Every one he asked declared it could be found farther south, so he remained there no longer but sailed south again. After a comparatively short voyage he discerned a country different from any he had yet seen, not only in size but in general character. It was not level like the others but had many mountains and valleys, forests, brooks, and rivers. He was in doubt whether it was part of the mainland or a large island. After several days’ observations he was convinced it was an island, called by the natives Cuba. He came to anchor at the mouth of a large river, as he was anxious to get a near view of the people and their country. All of them fled to the mountains at sight of the vessels, leaving their cabins empty. Only one of them had the courage to row out in a small skiff and go aboard. After his confidence had been secured by some little gifts, Columbus sent two Spaniards and one of the natives of Guanahani whom he had taken with him to learn something about the region and conciliate the natives, for he was very anxious they should not flee every time they saw the vessels. The two Spaniards proceeded inland about twelve miles and upon their return submitted the following report to the Admiral:

“We found a great part of the country under cultivation and exceedingly productive. Indian corn or maize and a kind of root, which, when baked, tastes like bread, grows in the fields. We came at last to a village of at least fifty wooden dwellings and about a thousand people. The leaders came out to meet us and when they heard we had natives on board and what kind of people we were, they embraced us and conducted us to their largest house. We sat upon chairs shaped like an animal, its tail serving for the back and its eyes and ears fashioned of gold. When we were seated the natives sat near us on the floor, kissed our hands and feet, and paid us such homage it was easy to see they thought we were superhuman and celestial beings. They gave us to eat of their baked root, which had the flavor of chestnuts. We noticed that all who waited upon us were men. After a little they withdrew and several women entered, who bestowed the same marks of homage as the men. When at last we made ready to return, many of the natives asked permission to accompany us, but we declined, taking with us only the King and his son, who have come with us as a special mark of honor.”

The Admiral expressed his gratitude to the two and entertained them on board his vessel most hospitably. In reply to inquiries as to the locality of the gold country they pointed to the east, but could not understand why white men should be so eager to find a metal which to them was valueless except as an ornament. The whites wondered still more at the simplicity of these people. Columbus shortened his stay, as he was anxious to start in the direction they had indicated and search for the much coveted gold in a country which was called Haiti by the natives.

Columbus left Cuba November 19 and took twelve of the natives with him with the intention of carrying them to Spain when he returned. They left their fatherland without much regret, for he had left nothing undone to make their condition agreeable. As the winds were contrary and Columbus’ large vessel could make only slow progress, Alonzo Pinzon, captain of the Pinta, having the swiftest of the ships, determined to slip away from the Admiral, get to the gold country first, and fill his sacks before the rest got there. Columbus knew Pinzon’s purpose and signalled him to wait, but Pinzon paid no heed and sailed away as fast as he could to satisfy his greed for gold.

The Admiral had to submit to what he could not change but, as it soon became so stormy that it was dangerous to keep out to sea, he was forced to return to Cuba and anchor again in a secure harbor. He passed the time in making closer observations of the country and the natives. He noticed one peculiarity in their eating, which at first disgusted the Spaniards. They were particularly fond of a kind of large spider, worms which they found in rotting wood, and half cooked fish, which they ate ravenously. After a little some of the Spaniards tried to eat them but had to abandon the experiment. As soon as the weather favored, Columbus started anew to seek for Haiti and his faithless comrade, Pinzon. He had but sixteen miles to go and was soon there. He arrived at Haiti December 6, and named the island Hispaniola, or Little Spain. Upon his arrival the natives fled to the woods and nothing was seen or heard of the Pinta. The Admiral shortly left the harbor into which he had run and began a cruise along the coast to the north. He soon reached another harbor and there his desire to get acquainted with the natives was gratified. In general appearance and habits they resembled the natives of Guanahani and Cuba. They went unclad, were copper colored, and were simple, gentle, and ignorant like the others. They also thought the Spaniards were not human but celestial beings. They wore more gold ornaments than the others and cared so little for gold that they willingly exchanged it for beads, pins, bells, and other trifles. But when Columbus inquired for the place where it was to be found, they pointed to the east, so once more he set sail in the hope of finding the source of this inexhaustible treasure.

While the ships were lying at anchor in an inlet of the same island of Hispaniola the cacique who ruled that region heard of the arrival of these wonderful white men and condescended to make the Admiral a visit. His retinue was quite imposing. He himself was borne in a litter by four men, his princely body almost as destitute of clothing as those of his dependents.

The cacique went on board without the slightest hesitation and, observing that the Admiral was seated at table, entered the cabin, accompanied by two old men who appeared to be his councillors, and sat down familiarly but respectfully by the side of Columbus, the old men reclining at his feet. The Admiral offered him food and wine, which he tasted, sending what was left to his people on deck. After the meal was finished he presented the Admiral with some gold ornaments and a skilfully made girdle, Columbus, in turn, presenting him a string of amber beads and a pair of red slippers, besides a rug and a flask of orange-flower water. The cacique was so delighted that he assured Columbus everything in his country was at Columbus’ disposal.

The attitude of the cacique toward his own people was very stately but with the Spaniards he was quite familiar. He paid close attention to everything and expressed great admiration for all that he saw. Toward evening he expressed the desire to go ashore again. His wish was gratified and, the more deeply to impress him, the Admiral saluted his departure with cannon. Thereupon he declared they must be of heavenly origin for they could control the thunder and lightning. The awe with which his servants regarded them was so great that they kissed the footprints left by the Spaniards. As the cacique’s country, however, did not contain the rich gold mines, which were now the only object of Columbus’ quest, he weighed anchor again and sailed still farther eastward.

All the information received by Columbus was to the effect that the gold was in a mountainous country ruled by a powerful cacique. Thither he hastened but, had he known of the serious disaster which was to happen on his short voyage, he would have given up the gold itself rather than pay such a heavy cost for the effort of finding it. On this voyage they came to a cape, where the sea was so calm they might easily have anchored a short distance from shore. He had not slept for two days and nature at last claimed her rights. Entrusting the tiller to a helmsman, he urged him to be careful, and went below to take a little rest. Hardly had he fallen asleep before the careless sailors imitated his example, deserted their posts, and went to sleep also. Even the helmsman, who thought there was no danger in such quiet waters, disregarded his superior’s orders, turned his duties over to an ignorant cabin-boy, and went to sleep. This boy was the only one awake on the vessel. While all were sleeping the ship was driven by a strong current toward the shore. A sudden shock forced the tiller from the boy’s hands. Awakened by his shouts, Columbus rushed upon deck, saw the rocks, and instantly knew that the vessel had struck upon them. There was immediate confusion. Columbus alone kept his presence of mind and made preparations to save the vessel. He ordered a boat’s crew to drop anchor at some distance away so that they might, if possible, warp it off the rocks. The boat’s crew were so frightened, however, that his orders were not obeyed. They thought only of their own safety and rowed to the Nina. Its commander, however, refused to take on board the men who had been so forgetful of duty as to leave their commander in the lurch. Columbus in the meantime cut the masts and threw everything overboard that was useless, hoping to lighten the vessel, but its keel was split and the water poured in so fast and continuously that at length the Admiral and crew abandoned it and rowed to the Nina.

On the next morning he sent a message to the cacique telling him of the disaster which had occurred and asking the assistance of his people in saving the valuables on board the wrecked vessel. The cacique, whose name was Guakanahari, was greatly distressed by the news and, shedding tears over it, hastened to the relief of the unfortunate Europeans, accompanied by many of his people.

These kindly natives did not improve the opportunity to steal but exerted themselves to the utmost to save everything. They collected a number of canoes and, by their united exertions, everything of importance was taken ashore. The noble Guakanahari took charge of the valuables and from time to time sent one of his kinsmen, who implored Columbus with tearful eyes not to grieve, for the cacique would give him all he had if it were necessary. The latter took the valuables to his own house and stationed a strong guard to watch them until they should be needed by Columbus, although it seemed unnecessary, for the natives deplored the disaster as keenly as if it had happened to themselves. In the report which Columbus made to the Court of Spain he paid a glowing tribute to these noble natives. “In reality, Your Majesty,” he said, “these people are so gentle and peaceful, I can assure you there can be no better people in the world. They love their neighbors as themselves. Their demeanor is always pleasant and agreeable. They are invariably cheerful and kind and they speak to you with a smile. Though it is true that they go naked, Your Majesty may be assured that they are modest and exemplary in their habits. Their King is treated with the highest respect and he himself is so noble and generous that it is a great pleasure to have known him. He and his people will always live in my pleasant memory.”

When Guakanahari discovered how fond of gold the Europeans were, he made them many golden presents to console them for their misfortune and promised to get more for them from a place he called Cibao.[16] Many of his people also brought gold and were delighted to exchange it for European knick-knacks. One of them, holding a large piece in one hand, extended the other to a Spaniard, who placed a bell in it. The native dropped the gold and fled, thinking he had cheated the white man and would be looked upon as a thief.

The Spaniards now began to enjoy their stay there but in the meantime Columbus was harassed by anxiety night and day. His best vessel was lost. The faithless Pinzon had deserted him. The only one of his vessels left was so small and poorly built that it would not accommodate his men nor was it sufficiently seaworthy for the long return voyage. At last he decided that he would take a few men and try to go back, notwithstanding all dangers, so that the news of his discovery should reach the Court, and leave the others as colonists in Hispaniola. His decision was universally approved and a sufficient number expressed their willingness to remain. The cacique was greatly pleased when he learned that the celestial visitants were going to remain and protect him and his people against their enemies. According to his statement a savage, warlike race, called Caribs, lived on certain islands to the southeast. From time to time, he asserted, his country was invaded by them and, as his people were too weak to resist them and dared not remain in their vicinity, they had to flee to the mountains.[17]

Columbus promised to protect them and, to impress them with his power, ordered his people to perform some military manœuvres in their presence. They were greatly astonished, but when the cannon which had been taken off the wrecked vessel were fired, they were so frightened that they threw themselves upon the ground and covered their faces. Guakanahari himself was greatly alarmed and his fear was not allayed until Columbus assured him that the thunder should harm only his enemies. That he might fully realize its destructive effect he aimed a cannon at the wrecked vessel and fired. The ball went through it and struck the water on the other side. This sight so amazed the cacique that he went home, being firmly convinced his guests were from the skies and that they controlled the thunder and lightning.

Several days were now spent in the erection of a small fort and the kindly natives lent all possible assistance, little dreaming, however, that they were forging the fetters which one day would bind them. Whenever the Admiral was on shore the cacique lavished favors upon him which he generously requited. Once he received Columbus with a golden crown on his head and conducted him to a richly decorated house. Then he took off the crown and with great reverence placed it upon Columbus. The latter took a necklace of small pearls which he was wearing and placed it around the cacique’s neck. Then he took off his handsome cloak and put it on the Prince, and placed a silver ring upon his finger. Not content with this, he drew off a pair of red buskins and gave them to him. With this interchange of tokens of good-will a bond of friendship was established between them.

The fort was finished in ten days and Columbus selected forty-three men who were to garrison it under command of the nobleman, Diego de Cerana. He ordered them to render him absolute obedience to preserve the good-will of Guakanahari and his people in every way and to acquaint themselves with their language. The place where he left them he named La Navidad.

After this, Columbus went on board the little vessel and on January 4, 1493, weighed anchor. A bold venture! In a small, unseaworthy vessel he determined to recross the vast and still little known ocean. To remove every vestige of doubt at the suspicious Court and convince the King of the truth of his discoveries, he took with him as evidence not only gold but several of the natives, besides unknown birds of various species. On his voyage eastward he kept his course for some time along the coast of Hispaniola to get a view of the adjacent region. On the second day he saw a vessel in the distance. He at once sailed in its direction and found it to be the vessel of the faithless Pinzon, of which he had had no trace for six weeks. Pinzon came on board and tried to convince Columbus it was all the fault of stormy weather which had driven him out to sea. Columbus knew this was false but, naturally magnanimous, he affected to believe it and took him into his favor, highly pleased that the results of his great discoveries no longer depended upon the safety of one small vessel. Pinzon also had been cruising along the coast of Hispaniola but in a different direction, bartering for gold.

A fresh west wind, which fortunately had sprung up, carried the vessels swiftly along and the joyful crews already fancied themselves in Spain telling their astonished listeners the story of the wonders of the New World. Then suddenly a storm cloud arose in the western sky. The storm rapidly approached. It grew darker and darker and the frightened sailors, in anxious expectancy of what might happen, stood around the deck watching the Admiral who, with his customary composure, issued the necessary orders.

Now the waves of the broad ocean began to rise, the vessels were tossed about, the cordage rattled, and the wind howled fearfully through the rigging. It lightened, then again was dark as night. It thundered and a tempest of rain beat upon the tossing vessels. The storm burst upon them in all its fury. The lightning flashed, the thunders crashed, the waves rushed along, the winds howled, and the reeling vessels were now hurled high in air by the mighty billows and now plunged into deep abysses. The sailors were overcome with fear. Some of them fell upon their knees and prayed with uplifted hands that their lives might be spared. Others stood or lay prostrate, paralyzed with fright, and appeared more dead than alive; still others sought shelter in superstitions and promised if Heaven would save them they would make a barefooted pilgrimage to some church dedicated to the Virgin in the first Christian country they reached. They were really in a desperate plight. They swung as it were between death and life and every mountainous wave which lifted them upon its mighty crest and hurled them down again into the watery abyss seemed to them the messenger of their doom. In vain Columbus sought to employ every means of safety suggested by his skill and experience; in vain he tried to encourage them and to rouse them to activity. They were soulless bodies capable of no effort while the storm raged on with irresistible fury. At last, when he was convinced that human help was impossible, he betook himself with sorrowing heart to his cabin to provide in some way that his great discoveries should not be lost to the world. Nothing troubled him so much as the thought that the important intelligence he was taking to Europe might be lost. It pierced his great heart like a sharp two-edged sword and moved him to think not so much of himself and his own safety as of some means to avert what in his estimation was the greatest of calamities. With death staring him in the face this unterrified man was still capable of thinking clearly and quietly, of formulating concise decisions, and putting them into effect.

Columbus took a parchment, inscribed upon it an account of his discoveries, wrapped it in oilcloth and sealed it with wax. This packet he placed in a well protected cask and threw it into the ocean, hoping it would be washed ashore where some one was living who would open it and thus become acquainted with his discoveries. Some time after this he fastened a second cask with a similar package to the stern of his vessel so that it should go with him if the vessel went down with him and his people.

In the meantime, to increase the terror of the frightful death which menaced the crew every moment, the darkest and most cruel of all nights came on. No mild stars, such as bring hope to the despairing, shone in the heavens. Sky and sea were enveloped in dense darkness and the raging hurricane continued without the least abatement of its fury. Thus they alternated between life and death, only half alive. But the dreadful night passed at last and in the first glimmer of dawn, to the unspeakable delight of the wretched crew, land was seen in the distance. The Azores lay before their eyes but, as the storm had not yet abated, Columbus could not get near the shore. They had longed for a speedy landing but, in view of the danger, they found it necessary to hold off for four days. The Pinta had disappeared and it was uncertain whether it had gone down or whether Pinzon had taken advantage of the storm and the darkness to forsake the Admiral and reach Spain with the first news of the discoveries. At last the storm subsided and Columbus lost no time in coming to anchor. Several Portuguese came to the vessel and offered food for sale and inquired whence they had come and whither they proposed to go.

Learning from them that there was an oratory of the Virgin not far from the shore, Columbus permitted half of his men to land and fulfil the promise they had made. He himself had grown lame in both hips owing to his long watching and painful exertions and had to remain on board, but he ordered them to return as soon as possible so that the others might go ashore and perform their vows also. They promised to obey him, disrobed themselves, and went barefooted to the oratory. Several hours passed but none of them came back. He waited hour after hour but no one appeared. At last it was night and still no one came. He grew suspicious but, to learn the true state of affairs, had to wait until morning. Morning came and then he was astonished to discover that the Portuguese had overpowered the pilgrims and placed them under arrest. Columbus was extremely indignant at this treacherous conduct and, as his protests were useless, he at last threatened that he would not sail until he had taken a hundred Portuguese prisoners and laid waste the island. His threat made an impression upon them. They sent messengers to inquire in the name of the governor whether he and his vessels were in the service of the Spanish court. When Columbus had convinced them of this by his letter of credentials they released the prisoners. The governor, it is said, had instructions from his King to seize the person of Columbus, if he could, and imprison him and his people and then quietly take possession of the countries discovered by him. But as this could not be done, because Columbus remained on board, he thought it wiser to give up the prisoners and pretend that they had not known they were Spaniards. Delighted with the fortunate settlement of this troublesome business, Columbus again set sail, pleased with the prospect that all hardships and dangers were ended. But Heaven had decreed that his steadfastness must once more be tested.

The fearful storm broke out anew, the vessel was driven from its course, the sails were torn, the masts wavered, and at every shock of the waves the despairing crew expected to be lost. In this desperate condition, which had now lasted two days, the crew suddenly perceived rocks, upon which the old and shattered vessel was being driven. Had it continued in that direction a moment longer it would have been destroyed, but Columbus’ presence of mind did not forsake him in this appalling crisis. A skilful turn which he made at just the right time saved the vessel and all on board. He soon recognized that he was on the Portuguese coast and certainly at the mouth of the Tagus, so he decided to come to anchor.

At daybreak he sent messengers, one to Madrid to notify the King of Spain of his safe arrival, the other to the King of Portugal at Lisbon to ask permission to come up the Tagus to the city and repair his vessel. Permission being granted, he sailed without delay to Lisbon. The news of the approach of the famous vessel rapidly spread through the city, and all who could, ran to the harbor. The shore was crowded with people and the river with boats, for every one was eager to see the wonderful man who had achieved such an extraordinary undertaking. Some thanked God for the favor He had shown the bold navigator, others deplored the misfortune of their fatherland in rejecting his services. The King of Portugal himself could not now refuse to pay his respects to Columbus notwithstanding his deep regret that by this man’s discoveries Spain would greatly increase its power and secure possessions which, but for the folly of his advisers, he might have had. He ordered his subjects to pay Columbus all possible honor, to provide his men with subsistence, and also wrote a very complimentary letter, inviting him to call upon him. Columbus hastened to accept the royal invitation. Upon his arrival the entire Court, by command of the King, went out to meet him. During the interview the King insisted that Columbus should speak sitting, and with covered head, and displayed a lively interest in the account of the discoveries and sought by flattering appeals to induce him to engage in his service. It was in vain, however. He might have offered him half of his kingdom without causing him to waver in his devotion to the Court to which he had dedicated his services. After a courteous withdrawal and the necessary repairs to his vessel he again set sail for the same Spanish port (March 15) which he had left seven months and eleven days before.

Hardly had the news of Columbus’ approach reached Palos before the people rushed to the harbor to see with their own eyes whether it was true. As the vessel drew near and they recognized upon its deck, one his son, another his brother, a third his friend, and a fourth her husband, a universal outburst of joy rent the air, thousands of arms were outstretched in welcome to the loved strangers, and thousands more shed tears of joy.

As Columbus stepped ashore he was greeted by the roar of cannon, the jubilant clang of bells, and the enthusiastic shouts of the multitude. Unmoved by what would have turned the heads of ordinary men, he made it his first duty to declare that the fortunate outcome of his great undertaking was due not to himself but to God. He went immediately to the church in which he had implored the divine favor before his departure, accompanied by his sailors and all the people. After publicly acknowledging his obligations to the Almighty, he proceeded to Barcelona, a city in Catalonia, where the King and Queen of Spain were holding Court. Pinzon had arrived at another Spanish port several days before Columbus, with the intention of being the first to announce the news to the Court, but the King had ordered him not to appear except in the company of Columbus. Thereupon the conceited Pinzon was so disappointed that he fell ill and died in a few days.

At every place along his route Columbus was welcomed by extraordinary multitudes from the neighboring regions and heard his name pass admiringly from mouth to mouth. At last he reached Barcelona, where the King and Queen impatiently awaited him. The whole Court household went out to pay him honor. The streets were so densely crowded that it was almost impossible for him to make his way. The procession moved in the following order: Several Indians, in their native costumes, whom Columbus had taken with him, were in the advance; behind them, men carried the gold plates, gold-dust, and gold ornaments which he had brought; then followed others with samples of the products of the newly discovered region, such as balls of cotton yarn, chests of pepper, parrots carried upon long reeds, stuffed animals, and a multitude of other objects which had never been seen in Europe before; at last came Columbus himself, the cynosure of all eyes.

THE RETURN OF COLUMBUS FROM HIS FIRST VOYAGE

To pay especial honor to Columbus Their Majesties had caused a magnificent throne to be erected in the public square where they awaited him. As he approached them with the intention of kneeling as usual at the foot of the throne, the King extended his hand to him to be kissed and requested him to sit by his side upon a chair placed there for him. Thereupon he modestly told the story of his discoveries and displayed the proofs of them in the objects he had brought. When he had finished his story, both Their Majesties and the multitude of assembled spectators knelt and thanked God that these great discoveries, so rich in advantage to Spain, had been made in their day. Thereupon all the honors which Columbus had asked as reward were granted. He and his whole family were ennobled, and whenever the King rode out, the much-loved Admiral rode at his bridle, an honor which up to that time had been enjoyed only by princes and the royal family. But what pleased him most was the royal order that an entire fleet for a second expedition should be equipped.

In the meantime the King sent an ambassador to Rome praying the Pope that he would confirm the Spaniards in possession of the newly discovered regions and all that might yet be discovered by them in the ocean. The Pope, Alexander VI, drew upon a globe a line of demarcation from one pole to another, at a distance of a hundred miles from the Azores, and issued a bull declaring that all land discovered beyond that line should belong to Spain. At that time it was the rule that a prince could hold possession of a newly discovered country only when the Pope, as the divine representative upon earth, had confirmed it.

The fleet was fitted out so rapidly that in a short time seventeen excellent vessels waited at Cadiz in readiness to sail. The desire to secure possessions and honor induced an incredible number of men of all classes to apply for participation in the expedition, but Columbus, not being able to accommodate all of them, selected fifteen hundred and paid special attention to the provisioning of the fleet and the procuring of all articles necessary to colonization. All sorts of implements were provided, besides animals unknown in the new world, such as horses, mules, and cows, all the European species of corn, and seeds of many herbs and plants which he believed would grow in that latitude. As he still labored under the delusion that the region discovered by him was a part of India, he gave it the name of West Indies to distinguish it from the real India, because to reach it he had to sail west from Europe. The Indies lying to the eastward were at that time called the East Indies.

Everything being ready, the fleet set sail from Cadiz September 25, 1493. Columbus at first directed his course toward the Canary Islands and arrived there October 5. There he took aboard fresh water, wood, and cattle, besides some swine, and set sail again from Ferro, October 13. In twenty days, aided by favoring winds, the fleet had covered a distance of eight hundred miles. On the second of November, thirty-six days after their departure from Spain, the fleet came to anchor off an island which Columbus named Dominica, because he discovered it on the Sunday which in the later Latin was called “Dies Dominica,” or the “Day of the Lord.” Dominica is one of the Lesser Antilles or Caribbean Islands. As he could not find good anchorage there he sailed farther on and shortly discovered several other islands, some of them of considerable size, such as Marie Galante, Guadeloupe, Antigua, Porto Rico, and St. Martin.