The few instances of inconsistent hyphenation have been retained.

Page 100— Changed Lubeck to Lübeck.

BY

AUGUSTUS J. C. HARE

AUTHOR OF "CITIES OF ITALY," "WANDERINGS IN SPAIN," ETC.

LONDON

GEORGE ALLEN, 156, CHARING CROSS ROAD

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1885

[All rights reserved]

The slight sketches in this volume are only the result of ordinary tours in the countries they attempt to describe. Yet the days they recall were so delightful, and their memory—especially of the tour in Norway—is so indescribably sunny, that I cannot help hoping their publication may lead others to enjoy what is at once so pleasant and so easy of attainment.

Augustus J. C. Hare.

Holmhurst: November 1884.

AT Roosendal, about an hour's railway journey from Antwerp, the boundary between Belgium and Holland is crossed, and a branch line diverges to Breda.

Somehow, like most travellers, we could not help expecting to see some marked change on reaching a new country, and in Holland one could not repress the expectation of beginning at once to see the pictures of Teniers and Gerard Dou in real life. We were certainly disappointed at first. Open heaths were succeeded by woods of stunted firs, and then by fields with thick hedges of beech or alder, till the towers of Breda came in sight. Here a commonplace omnibus took us to the comfortable inn of Zum Kroon, and we were shown into bedrooms reached by an open wooden staircase from the courtyard, and quickly joined the table d'hôte, at which the magnates of the town were seated with napkins well tucked up under their chins, talking, with full mouths, in Dutch, of which to [4]our unaccustomed ears the words seemed all in one string. Most excellent was the dinner—roast meat and pears, quantities of delicious vegetables cooked in different ways, piles of ripe mulberries and cake, and across the little garden, with its statues and bright flower-beds, we could see the red sails of the barges going up and down the canals.

As soon as dinner was over, we sallied forth to see the town, which impressed us more than any Dutch city did afterwards, perhaps because it was the first we saw. The winding streets—one of them ending in a high windmill—are lined with houses wonderfully varied in outline, and of every shade of delicate colour, yellow, grey, or brown, though the windows always have white frames and bars. Passing through a low archway under one of the houses, we found ourselves, when we least expected it, in the public garden, a kind of wood where the trees have killed all the grass, surrounded by canals, beyond one of which is a great square château built by William III. of England, encircled by the Merk, and enclosing an arcaded court. There was an older château of 1350 at Breda, but we failed to find it.

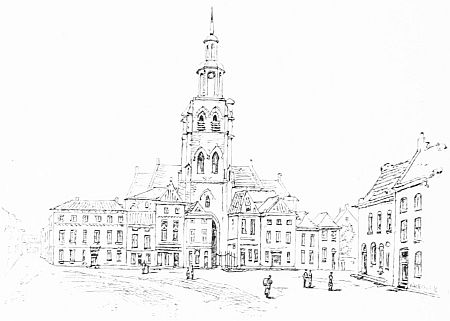

THE MARKET-PLACE AT BREDA.

In stately splendour, from the old houses of the market-place, rises the noble Hervormde Kerk (Protestant Church), with a lofty octagon tower, and [5]a most characteristic bulbous Dutch spire. Here, as we wanted to see the interior, we first were puzzled by our ignorance of Dutch, finding, as everywhere in the smaller towns, that the natives knew no language but their own. But two old women in high caps and gold earrings observed our puzzledom from a window and pointed to a man and a key—we nodded; the man pointed to himself, a door, and a key—we nodded; and we were soon inside the building. It was our first introduction to Dutch Calvinism and iconoclasm, and piteous indeed was it to see so magnificent a church thickly covered with whitewash, [6]and the quantity of statues which it contains of deceased Dukes and Duchesses of Nassau bereft of their legs and petticoats. Only, in a grand side chapel on the left of the choir, the noble tomb of Engelbrecht II. of Nassau, general under the Emperor Maximilian (1505), remains intact. The guide lights matches to shine through the transparent alabaster of the figures; that of the Duke represents Death, that of the Duchess Sleep, as they lie beneath a stone slab which bears the armour of Engelbrecht, and is supported by figures of Cæsar, Hannibal, Regulus, and Philip of Macedon; that of Cæsar is sublime. The tomb of Sir Francis Vere in Westminster Abbey is of the same design, and is supposed to be copied from this famous monument. Outside the chapel is the tomb of Engelbrecht V. of Nassau, with all his family kneeling, in quaint headdresses. The other sights of the church are the brass font in the Baptistery, and a noble brass in the choir of William de Gaellen, Dean of the Chapter, 1539. It will be observed that here, and almost everywhere else in Holland, the names of saints which used to be attached to the churches have disappeared; the buildings are generally known as the old church, or new church, or great church.

After a delicious breakfast of coffee and thick [7]cream, with rusks, scones, and different kinds of cheese, always an indispensable in Dutch breakfasts, we took to the railway again and crossed Zealand, which chiefly consists of four islands, Noordt Beveland, Zuid Beveland, Schouwen, and Walcheren, and is less visited by the rest of the Netherlanders than any other part of the country. The land is all cut up into vast polders, as the huge meadows are called, which are recovered from the sea and protected by embankments. Here, if human care was withdrawn for six months, the whole country would be under the sea again. A corps of engineers called 'waterstaat' are continually employed to watch the waters, and to keep in constant repair the dykes, which are formed of clay at the bottom, as that is more waterproof than anything else, and thatched with willows, which are here grown extensively for the purpose. If the sea passes a dyke, ruin is imminent, an alarm bell rings, and the whole population rush to the rescue. The moment one dyke is even menaced, the people begin to build another inside it, and then rely upon the double defence, whilst they fortify the old one. But all their care has not preserved the islands of Zealand. Three centuries ago, Schouwen was entirely submerged, and every living creature was drowned. Soon after, Noordt Beveland was submerged,[8]> and remained for several years entirely under water, only the points of the church spires being visible. Zuid Beveland had been submerged in the fourteenth century. Walcheren was submerged as late as 1808, and Tholen even in 1825. It has been aptly asserted that the sea to the inhabitants of Holland is what Vesuvius is to Torre del Greco. How well its French name of Pays-Bas suits the country! De Amicis says that the Dutch have three enemies—the sea, the lakes, and the rivers; they repel the sea, they dry the lakes, and they imprison the rivers; but with the sea it is a combat which never ceases.

BERGEN-OP-ZOOM.

The story of the famous siege of 1749 made us linger at Bergen-op-Zoom, a clean, dull little town with bright white houses surrounding an irregular market-place, and surmounted by the heavy tower of the Church of S. Gertrude. In the Stadhuis is a fine carved stone chimney-piece; but there is little worth seeing, and we were soon speeding across the rich pastures of Zuid Beveland, and passing its capital of Goes, prettily situated amongst cherry orchards, the beautiful cruciform church with a low central spire rising above the trees on its ramparts. Every now and then the train seems scarcely out of the water, which covers a vast surface of the pink-green flats, and recalls the description in Hudibras of—

The peasant women at the stations are a perpetual amusement, for there is far more costume here than in most parts of Holland, and peculiar square handsome gold ornaments, something like closed golden books, are universally worn on each side of the face.

So, crossing a broad salt canal into the island of Walcheren, we reached Middleburg, a handsome town which was covered with water to the house tops when [10]the island was submerged. It was the birthplace of Zach Janssen and Hans Lipperhey, the inventors of the telescope, c.1610. In the market-place is a most beautiful Gothic townhall, built by the architect Keldermans, early in the sixteenth century. We asked a well dressed boy how we could get into it, and he, without further troubling himself, pointed the way with his finger. The building contains a quaint old hall called the Vierschaar, and a so-called museum, but there is little enough to see. As we came out the boy met us. 'You must give me something: I pointed out the entrance of the Stadhuis to you.' In Holland we have always found that no one, rich or poor, does a kindness or even a civility for nothing!

The crowd in the market-place was so great that it was impossible to sketch the Stadhuis as we should have wished, but the people themselves were delightfully picturesque. The women entirely conceal their hair under their white caps, but have golden corkscrews sticking out on either side the face, like weapons of defence, from which the golden slabs we have observed before were pendant. The Nieuwe Kerk is of little interest, though it contains the tomb of William of Holland, who was elected Emperor of Germany in 1250, and we wandered on through the quiet streets,[11] till a Gothic arch in an ancient wall looked tempting. Passing through it we found ourselves in the enclosure of the old abbey, shaded by a grove of trees, and surrounded by ancient buildings, part of which are appropriated as the Hotel Abdij, where we arrived utterly famished, and found a table d'hôte at 2.30 P.M. unspeakably reviving.

Any one who sees Holland thoroughly ought also to visit Zieriksee, the capital of the island of Schouwen; but the water locomotion thither is so difficult and tedious that we preferred keeping to the railways, which took us back in the dark over the country we had already traversed, and a little more, to Dortrecht, where there is a convenient tramway to take travellers from the station into the town. Here, at the Hôtel de Fries, we found comfortable bedrooms, with boarded floors and box-beds like those in Northumbrian cottages, and we had supper in the public room, separated into two parts by a daïs for strangers, whence we looked down into the humbler division, which recalled many homely scenes of Ostade and Teniers in its painted wooden ceiling, its bright, polished furniture, its cat and dog and quantity of birds and flowers, its groups of boors at round tables drinking out of tankards, and the landlady and her daughter in their gleaming gold ornaments, sitting knitting, with the [12]waiter standing behind them amusing himself by the general conversation.

Our morning at Dortrecht was very delightful, and it is a thoroughly charming place. Passing under a dark archway in a picturesque building of Charles V. opposite the hotel, we found ourselves at once on the edge of an immense expanse of shimmering river, with long rich polders beyond, between which the wide flood breaks into three different branches. Red and white sails flit down them. Here and there rise a line of pollard willows or clipped elms, and now and then a church spire. On the nearest shore an ancient windmill, coloured in delicate tints of grey and yellow, surmounts a group of white buildings. On the left is a broad esplanade of brick, lined with ancient houses, and a canal with a bridge, the long arms of which are ready to open at a touch and give a passage to the great yellow-masted barges, which are already half intercepting the bright red house-fronts ornamented with stone, which belong to some public buildings facing the end of the canal. With what a confusion of merchandise are the boats laden, and how gay is the colouring, between the old weedy posts to which they are moored!

It was from hence that Isabella of France, with Sir John de Hainault and many other faithful knights, [13]set out on their expedition against Edward II. and the government of the Spencers.

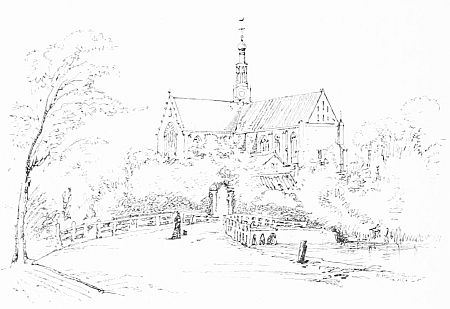

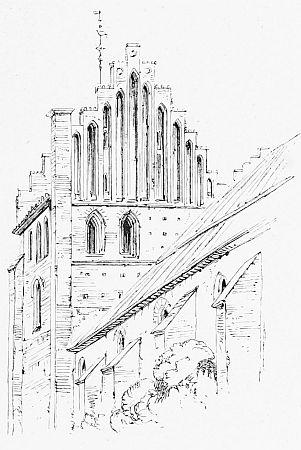

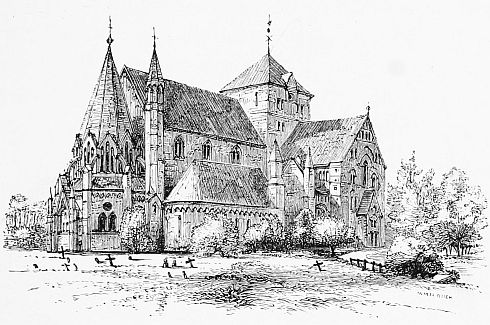

From the busy port, where nevertheless they are dredging, we cross another bridge and find ourselves in a quietude like that of a cathedral close in England. On one side is a wide pool half covered with floating timber, and, in the other half, reflecting like a mirror the houses on the opposite shore, with their bright gardens of lilies and hollyhocks, and trees of mountain ash, which bend their masses of scarlet berries to the still water. Between the houses are glints of blue river and of inevitable windmills on the opposite shore. And all this we observe standing in the shadow of a huge church, the Groote Kerk, with a nave of the fourteenth century, and a choir of the fifteenth, and a gigantic brick tower, in which three long Gothic arches, between octagonal tourelles, enclose several tiers of windows. At the top is a great clock, and below the church a grove of elms, through which fitful sunlight falls on the grass and the dead red of the brick pavement (so grateful to feet sore with the sharp stones of other Dutch cities), where groups of fishermen are collecting in their blue shirts and white trousers.

GROOTE KERK, DORTRECHT.

There is little to see inside this or any other church in Holland; travellers will rather seek for the [14]memorials, at the Kloveniers Doelen, of the famous Synod of Dort, which was held 1618-19, in the hope of effecting a compromise between the Gomarists, or disciples of Calvin, and the Arminians who followed Zwingli, and who had recently obtained the name of Remonstrants from the 'remonstrance' which they had addressed eight years before in defence of their doctrines. The Calvinists held that the greater part of mankind was excluded from grace, which the [15]Arminians denied; but at the Synod of Dort the Calvinists proclaimed themselves as infallible as the Pope, and their resolutions became the law of the Dutch reformed Church. The Arminians were forthwith outlawed; a hundred ministers who refused to subscribe to the dictates of the Synod were banished; Hugo Grotius and Rombout Hoogerbeets were imprisoned for life at Loevestein; the body of the secretary Ledenberg, who committed suicide in prison, was hung; and Van Olden Barneveldt, the friend of William the Silent, was beheaded in his seventy-second year.

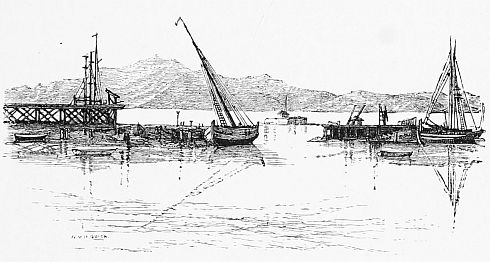

CANAL AT DORTRECHT.

There is nothing in the quiet streets of Dortrecht to remind one that it was once one of the most important commercial cities of Holland, taking precedence even of Rotterdam, Delft, Leyden, and Amsterdam. It also possessed a privilege called the Staple of Dort, by which all the carriers on the Maas and Rhine were forced to unload their merchandise here, and pay all duties imposed, only using the boats or porters of the place in their work, and so bringing a great revenue to the town.

More than those in any of the other towns of Holland do the little water streets of Dortrecht recall Venice, the houses rising abruptly from the canals; only the luminous atmosphere and the shimmering water changing colour like a chameleon, are wanting.

Through the street of wine—Wijnstraat—built over storehouses used for the staple, we went to the Museum to see the pictures. There were two schools of Dortrecht. Jacob Geritse Cuyp (1575), Albert Cuyp (1605), Ferdinand Bol (1611), Nicolas Maas (1632), and Schalken (1643) belonged to the former; Arend de Gelder, Arnold Houbraken, Dirk Stoop, and Ary Scheffer are of the latter. Sunshine and glow were the characteristics of the first school, greyness and sobriety of the second. But there are few good pictures at Dort now, and some of the best [17]works of Cuyp are to be found in our National Gallery, executed at his native place and portraying the great brick tower of the church in the golden haze of evening, seen across rich pastures, where the cows are lying deep in the meadow grass. The works of Ary Scheffer are now the most interesting pictures in the Dortrecht Gallery. Of the subject 'Christus Consolator' there are two representations. In the more striking of these the pale Christ is seated amongst the sick, sorrowful, blind, maimed, and enslaved, who are all stretching out their hands to Him. Beneath is the tomb which the artist executed for his mother, Cornelia Scheffer, whose touching figure is represented lying with outstretched hands, in the utmost abandonment of repose.

An excursion should be made from Dortrecht to the castle of Loevestein on the Rhine, where Grotius, imprisoned in 1619, was concealed by his wife in the chest which brought in his books and linen. It was conveyed safely out of the castle by her courageous maid Elsje van Houwening, and was taken at first to the house of Jacob Daatselaer, a supposed friend of Grotius, who refused to render any assistance. But his wife consented to open the chest, and the philosopher, disguised as a mason, escaped to Brabant.

It is much best to visit Rotterdam as an excursion [18]from Dortrecht. We thought it the most odious place we ever were in—immense, filthy, and not very picturesque. Its handsomest feature is the vast quay called the Boompjes, on the Maas. Here and there a great windmill reminds you unmistakably of where you are, and the land streets are intersected everywhere by water streets, the carriages being constantly stopped to let ships pass through the bridges. In the Groote Markt stands a bronze statue of Desiderius Erasmus—'Vir saeculi sui primarius, et civis omnium praestantissimus,' which is the work of Hendrik de Keyser (1662), and in the Wijde Kerkstraat is the house where he was born, inscribed 'Haec est parva domus, magnus qua natus Erasmus, 1467,' but it is now a tavern. The great church of S. Lawrence—Groote Kerk—built in 1477-87, contains the tombs of a number of Dutch admirals, and has a grand pavement of monumental slabs, but is otherwise frightful. The portion used for service is said to be 'so conveniently constructed that the zealous Christians of Rotterdam prefer sleeping through a sermon there, to any other church in the city.' Part of the rest is used as a cart-house, the largest chapel is a commodious carpenter's shop, and the aisles round the part which is still a church, where there has been an attempt at restoration in painting the roof yellow and [19]putting up some hideous yellow seats, are a playground for the children of the town, who are freely admitted in their perambulators, though for strangers there is a separate fee for each part of the edifice they enter.

We went to see the pictures in the Museum bequeathed to the town by Jacob Otto Boyman, but did not admire them much. It takes time to accustom one's mind to Dutch art, and the endless representations of family life, with domestic furniture, pots and pans, &c., or of the simple local landscapes—clipped avenues, sandy roads, dykes, and cottages, or even of the cows, and pigs, and poultry, which seem wonderfully executed, but, where one has too much of the originals, scarcely worth the immense amount of time and labour bestowed upon them. The calm seas of Van de Welde and Van der Capelle only afford a certain amount of relief. The scenes of village life are seldom pleasing, often coarse, and never have anything elevating to offer or ennobling to recall. We thought that the real charm of the Dutch school to outsiders consists in the immense power and variety of its portraits.

Hating Rotterdam, we thankfully felt ourselves speeding over the flat, rich lands to Gouda, where we found an agricultural fête going on, banners half way down the houses, and a triumphal arch as [20]the entrance to the square, formed of spades, rakes, and forks, with a plough at the top, and decorated with corn, potatoes, turnips, and carrots, and cornucopias pouring out flowers at the sides. In the square—a great cheese market, for the Gouda cheese is esteemed the best in Holland—is a Gothic Stadhuis, and beyond it, the Groote Kerk of 1552, of which the bare interior is enlivened by the stained windows executed by Wonter and Dirk Crabeth in 1555-57. We were the better able to understand the design of these noble windows because the cartoon for each was spread upon the pavement in front of it; but one could not help one's attention being unpleasantly distracted by the number of men of the burgher class, smoking and with their hats on, who were allowed to use the church as a promenade. Gouda also made an unpleasant impression upon us, because, expensive as we found every hotel in Holland, we were nowhere so outrageously cheated as here.

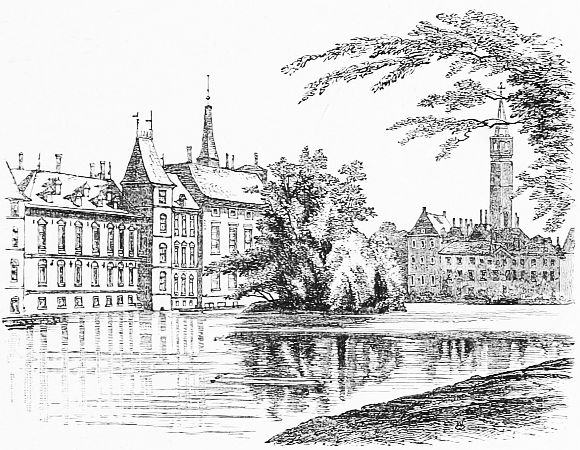

THE VIJVER.

It is a brief journey to the Hague—La Haye, Gravenhage—most delightful of little capitals, with its comfortable hotels and pleasant surroundings. The town is still so small that it seems to merit the name of 'the largest village in Europe,' which was given to it because the jealousy of other towns prevented its having any vote in the States General till the time of [21]Louis Bonaparte, who gave it the privileges of a city. It is said that the Hague, more than any other place, may recall what Versailles was just before the great revolution. It has thoroughly the aspect of a little royal city. Without any of the crowd and bustle of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, it is not dead like the smaller towns of Holland; indeed, it even seems to have a quiet gaiety, without dissipation, of its own. All around are parks and gardens, whence wide streets lead speedily through the new town of the rich bourgeoisie to the old central town of stadholders, where a beautiful lake, the Vijver, or fish-pond, comes as a [22]surprise, with the eccentric old palace of the Binnenhof rising straight out of its waters. We had been told it was picturesque, but were prepared for nothing so charming as the variety of steep roofs and towers, the clear reflections, the tufted islet, and the beautiful colouring of the whole scene of the Vijver. Skirting the lake, we entered the precincts of the palace through the picturesque Gudevangen Poort, where Cornelius de Witte, Burgomaster of Dort, was imprisoned in 1672, on a false accusation of having suborned the surgeon William Tichelaur to murder the Prince of Orange. He was dragged out hence and torn to pieces by the people, together with his brother Jean de Witte, Grand Pensioner, whose house remains hard by in the Kneuterdijk.

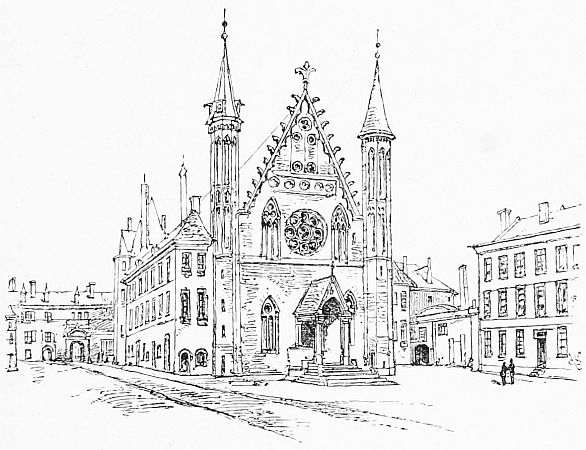

The court of the Binnenhof is exceedingly handsome, and contains the ancient Gothic Hall of the Knights, where Johann van Olden Barneveld, Grand Pensioner, or Prime Minister, was condemned to death 'for having conspired to dismember the States of the Netherlands, and greatly troubled God's Church,' and in the front of which (May 24, 1619) he was beheaded.

HALL OF THE KNIGHTS, THE HAGUE.

Close to the north-east gate of the Binnenhof is the handsome house called Mauritshuis, containing the inestimable Picture Gallery of the Hague, which will bear many visits, and has the great charm of not [23]being huge beyond the powers of endurance. On the ground floor are chiefly portraits, amongst which a simple dignified priest by Philippe de Champaigne, with a far-away expression, will certainly arrest attention. Deeply interesting is the portrait by Ravesteyn of William the Silent, in his ruff and steel armour embossed with gold—a deeply lined face, with a slight peaked beard. His widow, Louise de Coligny, is also represented. There is a fine portrait by Schalcken of our William the Third. Noble likenesses of Sir George Sheffield and his wife Anna Wake, by Vandyke, are a pleasing contrast to the many works of [24]Rubens. There are deeply interesting portraits by Albert Dürer and Holbein.

On the first floor we must sit down before the great picture which Rembrandt painted in his twenty-sixth year (1632) of the School of Anatomy. Here the shrewd professor, Nicholaus Tulp, with a face brimming with knowledge and intelligence, is expounding the anatomy of a corpse to a number of members of the guild of surgeons, some of whom are full of eager interest and inquiry, whilst others are inattentive: the dead figure is greatly foreshortened and not repulsive. In another room, a fine work of Thomas de Keyser represents the Four Burgomasters of Amsterdam hearing of the arrival of Marie de Medicis. A beautiful work of Adrian van Ostade is full of light and character—but only represents a stolid boor drinking to the health of a fiddler, while a child plays with a dog in the background.

A group of admirers will always be found round 'the Immortal Bull' of Paul Potter, which was considered the fourth picture in importance in the Louvre, when the spoils of Europe were collected at Paris. De Amicis says, 'It lives, it breathes; with his bull Paul Potter has written the true Idyl of Holland.' It is, however—being really a group of cattle—not a pleasing, though a life-like picture. Much more [25]attractive is the exquisite 'Presentation' of Rembrandt (1631), in which Joseph and Mary, simple peasants, present the Holy Child to Simeon, a glorious old man in a jewelled robe, who invokes a blessing upon the infant, while other priests look on with interest. A wonderful ray of light, falling upon the principal group, illuminates the whole temple. Perhaps the most beautiful work in the whole gallery is the Young Housekeeper of Gerard Dou. A lovely young woman sits at work by an open window looking into a street. By her side is the baby asleep in its cradle, over which the maid is leaning. The light falls on the chandelier and all the household belongings of a well-to-do citizen: in all there is the same marvellous finish; it is said that the handle of the broom took three days to paint.

There is not much to discover in the streets of the Hague. In the great square called the Plein is the statue of William the Silent, with his finger raised, erected in 1848 'by the grateful people to the father of their fatherland.' In the fish-market, tame storks are kept, for the same reason that bears are kept at Berne, because storks are the arms of the town. But the chief attraction of the place lies in its lovely walks amid the noble beeches and oaks of the Bosch, beyond which on the left is Huis ten Bosch, the Petit Trianon of the Hague, the favourite palace of Queen [26]Sophie, who held her literary court and died there. It is a quiet country house, looking out upon flats, with dykes and a windmill. All travellers seem to visit it,—which must be a ceaseless surprise to the extortionate custode to whom they have to pay a gulden a head, and who will hurry them rapidly through some commonplace rooms in which there is nothing really worth seeing. One room is covered with paintings of the Rubens school, amid which, high in the dome, is a portrait of the Princess Amalia of Solms, who built the house in 1647.

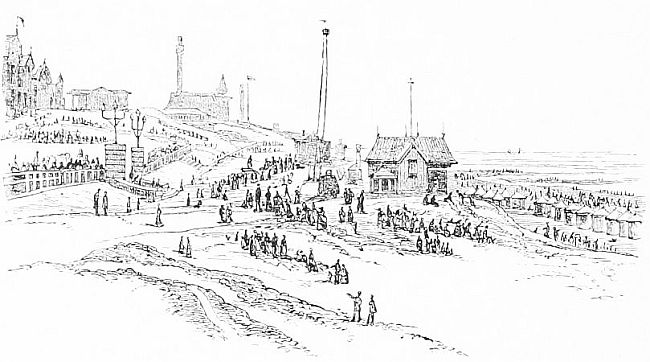

SCHEVENINGEN.

A tram takes people for twopence halfpenny to Scheveningen through the park, a thick wood with charming forest scenery. As the trees become more scattered, the roar of the North Sea is heard upon the shore. Above the sands, on the dunes or sand-hills, [27]which extend from the Helder to Dunkirk, is a broad terrace, lined on one side by a row of wooden pavilions with flags and porticoes, and below it are long lines of tents, necessary in the intense glare, while, nearer the waves, are thousands of beehive-like refuges, with a single figure seated in each. The flat monotonous shore would soon pall upon one, yet through the whole summer it is an extraordinary lively scene. The placid happiness of Dutch family life has here taken possession. On Sunday afternoons, especially, the sands seem as crowded with human existence as they are represented in the picture of Lingelbach, which we have seen in the Mauritshuis, portraying the vast multitude assembled here to witness the embarkation of Charles II. for England.

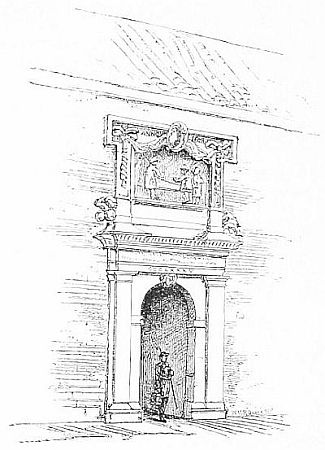

An excursion must be made to Delft, only twenty minutes distant from the Hague by rail. Pepys calls it 'a most sweet town, with bridges and a river in every street,' and that is a tolerably accurate description. It seems thinly inhabited, and the Dutch themselves look upon it as a place where one will die of ennui. It has scarcely changed with two hundred years. The view of Delft by Van der Meer in the Museum at the Hague might have been painted yesterday. All the trees are clipped, for in artificial Holland every work of Nature is artificialised. At [28]certain seasons, numbers of storks may be seen upon the chimney-tops, for Delft is supposed to be the stork town par excellence. Near the shady canal Oude Delft is a low building, once the Convent of S. Agata, with an ornamented door surmounted by a relief, leading into a courtyard. It is a common barrack now, for Holland, which has no local histories, has no regard whatever for its historic associations or monuments. Yet this is the greatest shrine of Dutch history, for it is here that William the Silent died.

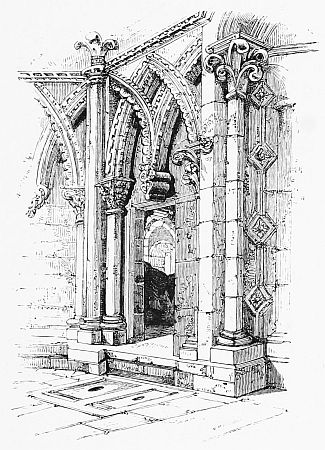

ENTRANCE TO S. AGATA, DELFT.

Philip II. had promised 25,000 crowns of gold to any one who would murder the Prince of Orange. An attempt had already been made, but had failed, and William refused to take any measures for self-protection, saying, 'It is useless: my years are in the hands of God: if there is a wretch who has no fear of death, my life is in his hand, however I may guard it.' At length, a young man of seven-and-twenty appeared at Delft, who gave himself out to be one Guyon, a Protestant, son of Pierre Guyon, executed at Besançon for having embraced Calvinism, and declared that he was exiled for his religion. Really he was Balthazar Gerard, a bigoted Catholic, but his conduct in Holland soon procured him the reputation of an evangelical saint. The Prince took him into his service and sent him to accompany a mission from the States of Holland to the Court of France, whence he returned to bring the news of the death of the Duke of Anjou to William. At that time the Prince was living with his court in the convent of S. Agata, where he received Balthazar alone in his chamber. The moment was opportune, but the would-be assassin had no arms ready. William gave him a small sum of money and bade him hold himself in readiness to be sent back to France. With the money Balthazar bought two pistols from a soldier [30](who afterwards killed himself when he heard the use which was made of the purchase). On the next day, June 10, 1584, Balthazar returned to the convent as William was descending the staircase to dinner, with his fourth wife, Louise de Coligny (daughter of the Admiral who fell in the massacre of S. Bartholomew), on his arm. He presented his passport and begged the Prince to sign it, but was told to return later. At dinner the Princess asked William who was the young man who had spoken to him, for his expression was the most terrible she had ever seen. The Prince laughed, said it was Guyon, and was as gay as usual. Dinner being over, the family party were about to remount the staircase. The assassin was waiting in a dark corner at the foot of the stairs, and as William passed he discharged a pistol with three balls and fled. The Prince staggered, saying, 'I am wounded; God have mercy upon me and my poor people.' His sister Catherine van Schwartzbourg asked, 'Do you trust in Jesus Christ?' He said, 'Yes,' with a feeble voice, sat down upon the stairs, and died.

Balthazar reached the rampart of the town in safety, hoping to swim to the other side of the moat, where a horse awaited him. But he had dropped his hat and his second pistol in his flight, and so he was traced and seized before he could leap from the wall. [31]Amid horrible tortures, he not only confessed, but continued to triumph in his crime. His judges believed him to be possessed of the devil. The next day he was executed. His right hand was burnt off in a tube of red-hot iron: the flesh of his arms and legs was torn off with red-hot pincers; but he never made a cry. It was not till his breast was cut open, and his heart torn out and flung in his face, that he expired. His head was then fixed on a pike, and his body cut into four quarters, exposed on the four gates of the town.

Close to the Prinsenhof is the Oude Kerk with a leaning tower. It is arranged like a very ugly theatre inside, but contains, with other tombs of celebrities, the monument of Admiral van Tromp, 1650—'Martinus Harberti Trompius'—whose effigy lies upon his back, with swollen feet. It was this Van Tromp who defeated the English fleet under Blake, and perished, as represented on the monument, in an engagement off Scheveningen. It was he who, after his victory over the English, caused a broom to be hoisted at his mast-head to typify that he had swept the Channel clear of his enemies.

The Nieuwe Kerk in the Groote Markt (1412-76) contains the magnificent monument of William the Silent by Hendrik de Keyser and A. Quellin (1621). [32]Black marble columns support a white canopy over the white sleeping figure of the Prince, who is represented in his little black silk cap, as he is familiar to us in his pictures. In the recesses of the tomb—'somptueux et tourmenté,' as Montégut calls it—are statues of Liberty, Justice, Prudence, and Religion. At the feet of William lies his favourite dog, which saved his life from midnight assassins at Malines, by awakening him. At the head of the tomb is another figure of William, of bronze, seated. In the same church is a monument to Hugo Grotius—'prodigium Europae'—the greatest lawyer of the seventeenth century, presented to Henri IV. by Barneveld as 'La merveille de la Hollande.'

On leaving the Hague a few hours should be given to the dull university town of Leyden, unless it has been seen as an afternoon excursion from the capital. This melancholy and mildewed little town, mouldering from a century of stagnation, the birthplace of Rembrandt, surrounds the central tower of its Burg—standing in the grounds of an inn, which exacts payment from those who visit it. Close by is the huge church of S. Pancras—Houglansche Kerk—of the fifteenth century, containing the tomb of Van der Werff, burgomaster during the famous siege, who answered the starving people, when they came demand[33]ing bread or surrender, that he had 'sworn to defend the city, and, with God's help, he meant to keep his oath, but that if his body would help them to prolong the defence, they might take it and share it amongst those who were most hungry.' A covered bridge over a canal leads to the Bredenstrasse, where there is a picturesque grey stone Stadhuis of the sixteenth century. It contains the principal work of Cornelius Engelbrechtsen of Leyden (1468-1533), one of the earliest of Dutch painters—an altarpiece representing the Crucifixion, with the Sacrifice of Abraham and Worship of the Brazen Serpent in the side panels, as symbols of the Atonement: on the pedestal is a naked body, out of which springs a tree—the tree of life—and beside it kneel the donors. The neighbouring church of S. Peter (1315) contains the tomb of Boerhaave, the physician, whose lectures in the University were attended by Peter the Great, and for whom a Chinese mandarin found 'à l'illustre M. Boerhaave, médecin, en Europe,' quite sufficient direction. Boerhaave was the doctor who said that the poor were his best patients, for God paid for them.

The streets are grass-grown, the houses damp, the canals green with weed. The University has fallen into decadence since others were established at [34]Utrecht, Groningen, and Amsterdam; but Leyden is still the most flourishing of the four. When William of Orange offered the citizens freedom from taxes, as a reward for their endurance of the famous siege, they thanked him, but said they would rather have a university. Grotius and Cartesius (Descartes), Arminius and Gomar, were amongst its professors, and the University possesses an admirable botanical museum and a famous collection of Japanese curiosities.

The Rhine cuts up the town of Leyden into endless islands, connected by a hundred and fifty bridges. On a quiet canal near the Beesten Markt is the Museum, which contains the 'Last Judgment' of Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), a scholar of Engelbrechtsen, and one of the patriarchs of Dutch painting.

A few minutes bring us from Leyden to Haarlem by the railway. It crosses an isthmus between the sea and a lake which covered the whole country between Leyden, Haarlem, and Amsterdam till 1839, when it became troublesome, and the States-General forthwith, after the fashion of Holland, voted its destruction. Enormous engines were at once employed to drain it by pumping the water into canals, which carried it to the sea, and the country was the richer by a new province.

MARKET-PLACE, HAARLEM.

Haarlem, on the river Spaarne, stands out distinct in recollection from all other Dutch towns, for it has the most picturesque market-place in Holland—the Groote Markt—surrounded by quaint houses of varied outline, amidst which rises the Groote Kerk of S. Bavo, a noble cruciform fifteenth-century building. The interior, however, is as bare and hideous as all other Dutch churches. It contains a monument to the architect Conrad, designer of the famous locks of Katwijk, 'the defender of Holland against the fury of the sea and the power of [36]tempests.' Behind the choir is the tomb of the poet Bilderdijk, who only died in 1831, and near this the grave of Laurenz Janzoom—the Coster or Sacristan—who is asserted in his native town, but never believed outside it, to have been the real inventor of printing, as he is said to have cut out letters in wood, and taken impressions from them in ink, as early as 1423. His partisans also maintain that whilst he was attending a midnight mass, praying for patience to endure the ill-treatment of his enemies, all his implements were stolen, and that when he found this out on his return he died of grief. It is further declared that the robber was Faust of Mayence, the brother of Gutenberg, and that it was thus that the honour of the invention passed from Holland to Germany, where Gutenberg produced his invention of movable type twelve years later. There is a statue of the Coster in front of the church, and, on its north side, his house is preserved and adorned with his bust.

Amongst a crowd of natives with their hats on, talking in church as in the market-place, we waited to hear the famous organ of Christian Muller (1735-38), and grievously were we disappointed with its discordant noises. All the men smoked in church, and this we saw repeatedly; but it would [37]be difficult to say where we ever saw a Dutchman with a pipe out of his mouth. Every man seemed to be systematically smoking away the few wits he possessed.

Opposite the Groote Kerk is the Stadhuis, an old palace of the Counts of Holland remodelled. It contains a delightful little gallery of the works of Franz Hals, which at once transports the spectator into the Holland of two hundred years ago—such is the marvellous variety of life and vigour impressed into its endless figures of stalwart officers and handsome young archers pledging each other at banquet tables and seeming to welcome the visitor with jovial smiles as he enters the chamber, or of serene old ladies, 'regents' of hospitals, seated at their council boards. The immense power of the artist is shown in nothing so much as in the hands, often gloved, dashed in with instantaneous power, yet always having the effect of the most consummate finish at a distance. Behind one of the pictures is the entrance to the famous 'secret-room of Haarlem,' seldom seen, but containing an inestimable collection of historic relics of the time of the famous siege of Leyden.

April and May are the best months for visiting Haarlem, which is the bulb nursery garden of the world. 'Oignons à fleurs' are advertised for sale [38]everywhere. Tulips are more cultivated than any other flowers, as ministering most to the national craving for colour; but times are changed since a single bulb of the tulip 'L'Amiral Liefkenshoch' sold for 4,500 florins, one of 'Viceroy' for 4,200, and one of 'Semper Augustus' for 13,000.

Now we entered Amsterdam, to which we had looked forward as the climax of our tour, having read of it and pondered upon it as 'the Venice of the north;' but our expectations were raised much too high. Anything more unlike Venice it would be difficult to imagine: and there is a terrible want of variety and colour; many of the smaller towns of Holland are far more interesting and infinitely more picturesque.

MILL NEAR AMSTERDAM.

A castle was built at Amsterdam in 1204, but the town only became important in the sixteenth century, since which it has been the most commercial of ancient European cities. It is situated upon the influx of the Amstel to the Y, as the arm of the Zuider Zee which forms the harbour is called, and it occupies a huge semicircle, its walls being enclosed by the broad moat, six and a half miles long, which is known as Buitensingel. The greater part of the houses are built on piles, causing Erasmus to say that the inhabitants lived on trees like rooks. In [39]the centre of the town is the great square called Dam, one side of which is occupied by the handsome Royal Palace—Het Palais—built by J. van Kampen in 1648. The Nieuwe Kerk (1408-1470) contains a number of monuments to admirals, including those of Van Ruiter—'immensi tremor oceani'—who commanded at the battle of Solbay, and Van Speyk, who blew himself up with his ship in 1831, rather than yield to the Belgians. In the Oude Kerk of 1300 there are more tombs of admirals. Hard by, in the Nieuwe Markt, is the picturesque cluster of [40]fifteenth-century towers called S. Anthonieswaag, once a city gate and now a weighing-house.

But the great attraction of Amsterdam is the Picture Gallery of the Trippenhuis, called the Rijks Museum, and it deserves many visits. Amongst the portraits in the first room we were especially attracted by that of William the Silent in his skull-cap, by Miereveld, but all the House of Orange are represented here from the first to the last. We also see all the worthies of the nation—Ruyter, Van Tromp and his wife, Grotius and his wife, Johann and Cornelis de Witt, Johann van Oldenharneveldt, and his wife Maria of Utrecht, a peaceful old lady in a ruff and brown dress edged with fur, by Moreelse. The two great pictures of the gallery hang opposite each other. That by Bartholomew van der Helst, the most famous of Dutch portrait-painters, represents the Banquet of the Musqueteers, who thus celebrated the Peace of Westphalia, June 18, 1648. It contains twenty-five life-size portraits, is the best work of the master, and was pronounced by Sir Joshua Reynolds to be the 'first picture of portraits in the world.' The canvas is a mirror faithfully representing a scene of actual life. In the centre sits the jovial, rollicking Captain de Wits with his legs crossed. The delicate imitation of reality is [41]equally shown in the Rhenish wine-glasses, and in the ham to which one of the guests is helping himself.

The rival picture is the 'Night Watch' of Rembrandt (1642), representing Captain Frans Banning Kok of Purmerland and his lieutenant Willem van Ruytenberg of Vlaardingen, emerging from their watch-house on the Singel. A joyous troop pursue their leader, who is in a black dress. A strange light comes upon the scene, who can tell whence? Half society has always said that this picture was the marvel of the world, half that it is unworthy of its artist; but no one has ever been quite indifferent to it.

Of the other pictures we must at least notice, by Nicholas Maas, a thoughtful girl leaning on a cushion out of a window with apricots beneath; and by Jan Steen, 'The Parrot Cage,' a simple scene of tavern life, in which the waiting-maid calls to the parrot hanging aloft, who looks knowingly out of the cage, whilst all the other persons present go on with their different employments. In the 'Eve of S. Nicholas,' another work of the same artist, a naughty boy finds a birch-rod in his shoe, and a good little girl, laden with gifts, is being praised by her mother, whilst other children are looking up the chimney by which the discriminating fairy Befana is supposed to have [42]taken her departure. There are many beautiful works of Ruysdael, most at home amongst waterfalls; a noble Vandyke of 'William II.' as a boy, with his little bride, Mary Stuart, Charles I.'s daughter, in a brocaded silver dress; and the famous Terburg called 'Paternal Advice' (known in England by its replica at Bridgewater House), in which a daughter in white satin is receiving a lecture from her father, her back turned to the spectator, and her annoyance, or repentance, only exhibited in her shoulders. Another famous work of Terburg is 'The Letter,' which is being brought in by a trumpeter to an officer seated in his uniform, with his young wife kneeling at his side. Of Gerard Dou Amsterdam possesses the wonderful 'Evening School,' with four luminous candles, and some thoroughly Dutch children. A girl is laboriously following with her finger the instructions received, and a boy is diligently writing on a slate. The girl who stands behind, instructing him, is holding a candle which throws a second light upon his back, that upon the table falling on his features; indeed the painting is often known as the 'Picture of the Four Candles.'

Through the labyrinthine quays we found our way to the Westerhoof to take the afternoon steamer to Purmerende for an excursion to Broek, 'the [43]cleanest village in the world.' Crossing the broad Amstel, the vessel soon enters a canal, which sometimes lies at a great depth, nothing being visible but the tops of masts and points of steeples; and which then, after passing locks, becomes level with the tops of the trees and the roofs of the houses. We left the steamer at T Schouw, and entered, on a side canal, one of the trekschuiten, which, until the time of railroads, were the usual means of travel—a long narrow cabin, encircled by seats, forms the whole vessel, and is drawn by a horse ridden by a boy (het-jagerte)—a most agreeable easy means of locomotion, for movement is absolutely imperceptible.

No place was ever more exaggerated than Broek. There is really very little remarkable in it, except even a greater sense of dampness and ooziness than in the other Dutch villages. It was autumn, and there seemed no particular attempt to remove the decaying vegetation or trim the little gardens, or to sweep up the dead leaves upon the pathways, yet there used to be a law that no animal was to enter Broek for fear of its being polluted. A brick path winds amongst the low wooden cottages, painted blue, green, and white, and ends at the church, with its miniature tombstones.

The most interesting excursion to be made from [44]Amsterdam is that to the Island of Marken in the Zuider Zee—a huge meadow, where the peasant women pass their whole lives without ever seeing anything beyond their island, whilst their husbands, who with very few exceptions are fishermen, see nothing beyond the fisher-towns of the Zuider Zee. There are very picturesque costumes here, the men wearing red woollen shirts, brown vests, wooden shoes, fur caps, and gold buttons to their collars and knickerbockers; the women, embroidered stomachers, which are handed down for generations, and enormous white caps, lined with brown to show off the lace, and with a chintz cover for week days, and their own hair flowing below the cap over their shoulders and backs.

An evening train, with an old lady, in a diamond tiara and gold pins, for our companion, took us to the Helder, and we awoke next morning at the pleasant little inn of Du Burg upon a view of boats and nets and the low-lying Island of Texel in the distance. The boats and the fishermen are extremely picturesque, but there is nothing else to see, after the visitor has examined the huge granite Helder Dyke, the artificial fortification of north Holland, which contends successfully to preserve the land against the sea. There is an admirably managed Naval Institute [45]here. It was by an expedition from the Helder that Nova Zembla was discovered, and it was near this that Admirals Ruyter and Tromp repulsed the English fleet. Texel, which lies opposite the Helder, is the first of a chain of islands—Vlieland, Terschelling, and Ameland, which protect the entrance of the Zuider Zee.

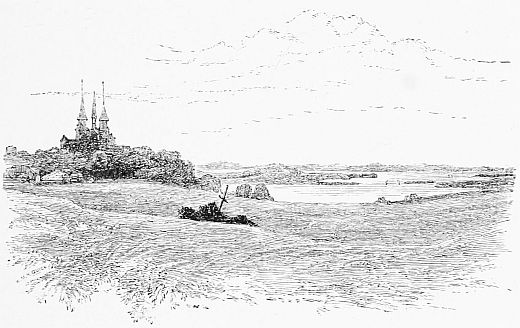

APPROACH TO ALKMAAR.

The country near the Helder is bare and desolate in the extreme. It is all peat, and the rest of Holland uses it as a fuel mine. It was here that the genius of Ruysdael was often able to make a single tree, or even a bush rising out of the flat by a stagnant pool, both interesting and charming to the spectator. We crossed the levels to Alkmaar, which struck us as being altogether the prettiest place in the country and as possessing all those attributes of cleanliness which are usually given to Broek. The streets, formed of bricks fitted close together, are absolutely spotless, and every house front shines fresh from the mop or the syringe. Yet excessive cleanliness has not destroyed the picturesqueness of the place. The fifteenth-century church of S. Lawrence, of exquisitely graceful exterior, rises in the centre of the town, and, in spite of being hideously defaced inside, has a fine vaulted roof, a coloured screen, and, in the chancel, a curious tomb to Florens V., Count of Holland, 1296, though only [46]his heart is buried there. Near the excellent Hôtel du Burg is a most bewitching almshouse, with an old tourelle and screen, and a lovely garden in a court surrounded by clipped lime-trees. And more charming still is an old weigh-house of 1582, for the cheese, the great manufacture of the district, for which there is a famous market every Friday, where capital costumes may be seen. The rich and gaily painted façade of the old building, reflected in a clear canal, is a perfect marvel of beauty and colour; and artists should stay here to paint—not the view given here, but another which we discovered too late—more in front, with gable-ended houses leading up to the [47]principal building, and all its glowing colours repeated in the water.

THE WEIGH-HOUSE, ALKMAAR.

It is three hours' drive from Alkmaar to Hoorn, a charming old town with bastions, gardens, and semi-ruined gates. On the West Poort a relief commemorates the filial devotion of a poor boy, who arrived here in 1579, laboriously dragging his old mother in a sledge, when all were flying from the [48]Spaniards. Opposite the weighing-house for the cheeses is the State College, which bears a shield with the arms of England, sustained by two negroes. It commemorates the fact that when Van Tromp defeated the English squadron, his ships came from Hoorn and on board were two negroes, who took from the English flagship the shield which it was then the custom to fix to the stern of a vessel, and brought it back here as a trophy. Hoorn was one of the first places in Holland to embrace the reformed religion, which spread from hence all over the country, but now not above half the inhabitants are Calvinists.

In returning from Alkmaar we stopped to see Zaandam, quite in the centre of the land of windmills, of which we counted eighty as visible from the station alone. They are of every shade of colour, and are mounted on poles, on towers, on farm buildings, and made picturesque by every conceivable variety of prop, balcony, gallery, and insertion. Zaandam is a very pretty village on the Zaan which flows into the Y, with gaily painted houses, and gay little gardens, and perpetual movement to and from its landing-stage. Turning south from thence, a little entry on the right leads down some steps and over a bridge to some cottages on the bank of a ditch, and inside the last of these is the tiny venerable hovel where Peter the [49]Great stayed in 1697 as Peter Michaeloff. It retains its tiled roof and contains some old chairs and a box-bed, but unfortunately Peter was only here a week.

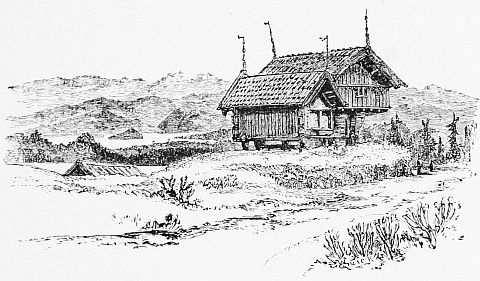

MILL AT ZAANDAM.

PAUSHUIZEN, UTRECHT.

The evening of leaving Zaandam we spent at Utrecht, of which the name is so well known from the peace which terminated the war of the Spanish succession, April 11, 1715. The town, long the seat of an ecclesiastical court, was also the great centre of the Jansenists, dissenters from Roman Catholicism under Jansenius, Bishop of Ypres, condemned by [50]Alexander VII. in 1656, at the instigation of the Jesuits. The doctrines of Jansenius still linger in its gloomy houses. Every appointment of a bishop is still announced to the Sovereign Pontiff, who as regularly responds by a bull of excommunication, which is read aloud in the cathedral, and then immediately put away and forgotten. Solemn and sad, but pre-eminently respectable, Utrecht has more the aspect of a decayed German city than a Dutch town, and so [51]has its Cathedral of S. Martin (1254-67), which, though the finest Gothic building in Holland, is only a magnificent fragment, with a detached tower (1321-82) 338 feet high. The interior as usual is ruined by Calvinism and yellow paint. It contains the tomb of Admiral van Gent, who fell in the battle of Solbay. The nave, which fell in 1674, has never been rebuilt. The S. Pieterskerk (1039) and S. Janskerk offer nothing remarkable, but on a neighbouring canal is the quaint Paushuizen, or Pope's house, which was built by Pope Adrian VI. (Adrian Floriszoom) in 1517. Near this is the pretty little Archiepiscopal Museum, full of mediæval relics.

The interesting Moravian establishment of Zeist may be visited from Utrecht.

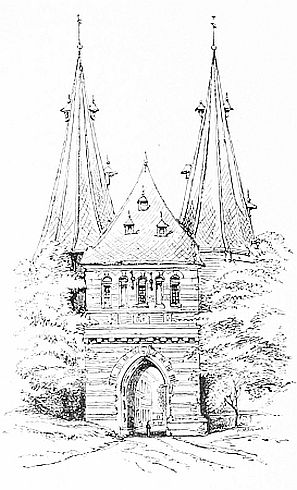

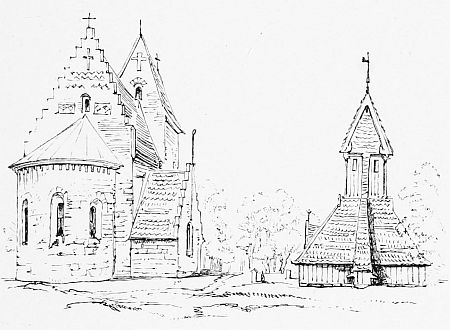

From Utrecht we travelled over sandy flats to Kampen, near the mouth of the wide river Yssel, with three picturesque gates—Haghen Poort, Cellebroeders Poort, and Broeders Poort; and a town hall of the sixteenth century. Here, as frequently elsewhere in Holland, we suffered from arriving famished at midday. All the inns were equally inhospitable: 'The table d'hôte is at 4 P.M.: we cannot and will not be bothered with cooking before that, and there is nothing cold in the house.' 'But you have surely bread and cheese?' 'Certainly not—nothing.'

CELLEBROEDERS POORT, KAMPEN.

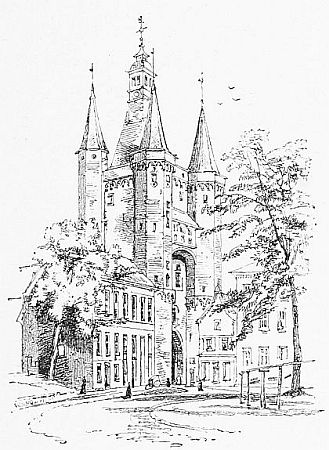

At Zwolle, however, we found the Kroon an excellent hotel with an obliging landlord; and Zwolle, the native place of Terburg (1608), is a charming old town with a girdle of gardens, a fine church (externally), and a noble brick gateway called the Sassenpoort.

SASSENPOORT, AT ZWOLLE.

It was more the desire of seeing something of the [53]whole country than anything else, and a certain degree of misplaced confidence in the pleasant volumes of Harvard, which took us up from Zwolle, through Friesland, the cow-paradise, to Leeuwarden, its ancient capital. Sad and gloomy as most other towns of Holland are, Leeuwarden is sadder and gloomier still. Its streets are wide and not otherwise than handsome, [54]but they are almost deserted, and there are no objects of interest to see unless a leaning tower can be called so, with a top, like that at Pisa, inclined the other way, to keep it from toppling over. An hour's walk from the town there is said to be a fine still-inhabited castle, and, if time had allowed, respect for S. Boniface would have taken us to Murmerwoude, where he was martyred (June 8, 853), with his fifty-three companions. King Pepin raised a hermitage on the spot, and an ancient brick chapel still exists there.

Here and elsewhere in Friesland nothing is so worthy of notice as the helmets—the golden helmets of the women—costing something equivalent to 25l. or 30l., handed down as heirlooms, fitting close to the head, and not allowing a particle of hair to be visible.

In the late evening we went on to Groningen, a university town with a good hotel (Seven Provincen), an enormous square, and a noble tall Gothic tower of 1627, whence the watchman still sounds his bugle. Not far off is Midwolde, where the village church has fine tombs of Charles Jerome, Baron d'Inhausen and his wife, Anna von Ewsum.

As late as the sixteenth century this province was for the most part uninhabited—savage and sandy, and overrun by wolves. But three hundred years of hard [55]work has transformed it into a fertile country, watered by canals, and sprinkled with country houses. Agriculturally it is one of the richest provinces of the kingdom. This is mostly due to its possessing a race of peasant-farmers who never shrink from personal hard work, and who will continue to direct the plough whilst they send their sons to the university to study as lawyers, doctors, or churchmen. These peasant farmers or boers possess the beklemregt, or right of hiring land on an annual rent, which the landlord can never increase. A peasant can bequeath his right to his heirs, whether direct or collateral. To the land, this system is an indescribable advantage, the cultivators doing their utmost to bring their lands to perfection, because they are certain that no one can take away the advantage from themselves or their descendants.

On leaving Groningen we traversed the grey, monotonous, desolate district of the Drenthe, sprinkled over at intervals by the curious ancient groups of stones called Hunnebedden, or beds of death (Hun meaning death), beneath which urns of clay containing human ashes have been found. From Deventer (where there is an old weigh-house, and a cathedral of S. Lievin with a crypt and nave of 1334), time did not allow us to make an excursion to [56]the great royal palace of Het Loo, the favourite residence of the sovereigns. The descriptions in Harvard rather made us linger unnecessarily at Zutphen, a dull town, with a brick Groote Kerk (S. Walpurgis) which has little remaining of its original twelfth-century date, and a rather picturesque 'bit' on the walls, where the 'Waterpoort' crosses the river like a bridge.

At Arnhem, the Roman Arenacum, once the residence of the Dukes of Gueldres, and still the capital of Guelderland, we seemed to have left all the characteristics of Holland behind. Numerous modern villas, which might have been built for Cheltenham or Leamington, cover the wooded hills above the Rhine. In the Groote Kerk (1452) is a curious monument of Charles van Egmont, Duc de Gueldres, 1538, but there is nothing else to remark upon. We intended to have made an excursion hence to Cleves, but desperately wet weather set in, and, as Dutch rain often lasts for weeks together when it once begins, we were glad to hurry England-wards, only regretting that we could not halt at Nymegen, a most picturesque place, where Charlemagne lived in the old palace of the Valckhof (or Waalhof, residence on the Waal), of which a fragment still exists, with an old baptistery, a Stadhuis of 1534, and a Groote Kerk containing a [57]noble monument to Catherine de Bourbon (1469), wife of Duke Adolph of Gueldres.

We left Holland feeling that we should urge our friends by all means to see the pictures at Rotterdam, the Hague, and Amsterdam, but to look for all other characteristics of the Netherlands in such places as Breda, Dortrecht, Haarlem, Alkmaar, and Zwolle.

FORMERLY the terrors of a sea-voyage from Kiel deterred many travellers from thinking of a tour in Denmark or Sweden, but now a succession of railways makes everything easy, and while nothing can be imagined more invigorating or pleasant, there is probably no pleasure more economical than a summer in Scandinavia. Those who are worn with a London season will feel as if every breath in the crystal air of Denmark endued them with fresh health and strength, and then, after they have seen its old palaces and its beech woods and its Thorwaldsen sculptures, a voyage of ten minutes will carry them over the narrow Sound to the soft beauties of genial Sweden and the wild splendours of Norway.

Either Hamburg or Lübeck must be the starting-point for the overland route to Denmark, and the old free city of Lübeck, though quite a small place, is one of the most remarkable towns in Germany. We arrived there one hot summer afternoon, after a weary [62]journey over the arid sandy plains which separate it from Berlin, and suddenly seemed to be transported into a land of verdure. Lilacs and roses bloomed everywhere; a wood lined the bank of the limpid river Trave, and in its waters—beyond the old wooden bridge—were reflected all the tallest steeples, often strangely out of the perpendicular, of many-towered Lübeck. A wonderful gate of red brick and golden-hued terra-cotta is the entrance from the station, and in the market-place are the quaintest turrets, towers, tourelles, but all ending in spires. The lofty houses, so full of rich colour, throw cool shade on the streets on the hottest summer day; and we enjoyed a Sunday in the excellent hotel, with wooden galleries opening towards a splashing fountain in a quiet square, where a fat constable busied himself in keeping everybody from fulfilling any avocation whatever whilst service was being performed in the churches, but let them do exactly as they pleased as soon as it was over.

It must, at best, be a weary journey across West Holstein, through a succession of arid flats varied by stagnant swamps. We spent the weary hours in studying Dunham's 'History of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway,' which cannot be sufficiently recommended to all Scandinavian travellers. The glowing [63]accounts in the English guide books of a lake and an old castle beguiled us into spending a night at Sleswig, but it turned out that the lake had disappeared before the memory of man, and that the castle was a white modern barrack. The colourless town and its long sleepy suburb, moored as if upon a raft in the marshes, straggle along the edge of a waveless fiord. At the end is the rugged cathedral like a barn, with a belfry like a dovecot, and inside it a curious altarpiece by Hans Brüggemann, pupil of Albert Dürer, and the noble monument of Frederick I., the first Lutheran King of Denmark; while richly carved doors at the sides of the church admit one to see how the grandmother of the Princess of Wales and various other potentates lie—Danish fashion—in gorgeous exposed coffins without any tombs at all. Everywhere roses grow in the streets, trained upon the house walls; and, up the pavement, crowds of the children were hurrying in the early morning, carrying in their hands the shoes they were going to wear when they were in school. In the evenings these children will not venture outside the town, for over the marshes they say that the wild huntsman rides, followed by his demon hounds and blowing his magic horn. It is the spirit of Duke Abel the fratricide, who, in the fens, murdered his brother Eric VI. of Denmark, and [64]who was afterwards lost there himself, falling from his horse, and being dragged down by the weight of his armour. To give rest to his wandering spirit, the clergy dug up his body and despatched it to Bremen, but there his vampire gave the canons no peace, so they sent the corpse back again, and now it lies once more in the marshes of Gottorp.

Most unutterably hideous is the country through which the railway now travels, wearisome levels only broken here and there by mounds, probably sepulchral. A straight line with tiny hillocks at intervals would do for a sketch of the whole of Sleswig and the greater part of Funen and Zealand. In times of early Danish history it was a frequent punishment to bury criminals alive in these dismal peat mosses. Twelve hours of changelessly flat scenery bring travellers from Hamburg to Frederikshaven, where we embark upon the Little Belt, the luggage-vans of the train being shunted on board the steamer. Immediately opposite lie the sandy shores of Funen, and in a few minutes we are there. Then four hours of ugly scenery take us across the island. It is only necessary to look out at the little town of Odense, called after the old hero-god, which was the birth-place of Hans Christian Andersen in 1805. The cathedral of Odense contains the shrine of the sainted [65]King Canute IV. (1080-86), who was murdered while kneeling before the altar, owing to indignation at the severe taxation to which the love of Church endowment had incited him.

Nyborg, where we meet the sea again, will recall to lovers of old ballads the story of the innocent young knight Folker Lowmanson, and his cruel death here in a barrel of spikes, from the jealousy of Waldemar IV. for his beautiful queen Helwig, and how, to know his fate—

At Nyborg we embark on a miserable steamer for the passage of the Great Belt. It lasts an hour and a half, and is often most wretched. On landing at Korsor travellers are hurried into the train which is waiting for the vessel.

Now the country improves a little. Here and there we pass through great beech woods. Down the green glades of one of them a glimpse is caught of the college of Sorö. It occupies the site of a monastery founded by Asker Ryg, a chieftain who, when he departed on a journey of warfare, vowed that if the child to which his wife, Inge, was about to give birth proved to be a girl, he would give his new building a spire, but a tower if it were a boy. On his return he saw two towers rising in the distance. Inge had given birth to twin sons, who lived to become Asbiorn Snare, celebrated in the ballad of 'Fair Christal,' and Absalon, the warrior Bishop of Roeskilde—'first captain by sea and land.' Absalon is buried here in the church of Sorö, which contains the tomb of King Olaf, the shortlived son of the famous Queen Margaret; of her cruel father, Waldemar Atterdag, whose last words expressed regret that he had not suffocated his daughter in her cradle; and of her grandfather, Christopher II., with his wife, Euphemia of Pomerania. Soon we pass Ringsted, which is scarcely worth stopping at, though its church contains the fine brass of King Erik Menred (1319) and his queen, Ingeborga, and though twenty kings and queens were entombed there before Roeskilde became the royal place of sepulture. Amongst them [67]lies the popular Queen Dagmar, first wife of Waldemar II., still celebrated in ballad literature, for there is scarcely a Dane who is ignorant of the touching story of 'Queen Dagmar's Death,' which begins

and which contains her last touching request to her husband, and her simple confession of the only 'sin' she could remember—

Tradition tells us that the dismal town of Ringsted was founded by King Ring, a warrior who, when he was seriously wounded in battle, placed the bodies of his slain heroes and that of his queen, Alpol, on board a ship laden with pitch, and going out to the open sea, set the vessel on fire, and then fell upon his sword.

In the twilight we pass Roeskilde, and at 10-1/2 P.M. long rows of street lamps reflected in canals show that we have reached Copenhagen.

To those whose travels have chiefly led them southwards there is a great pleasure in the first awaking in Copenhagen. Everything is new—the [68]associations, the characteristics, the history; even the very names on the omnibuses are suggestive of the sagas and romances of the North; and though the summer sun is hot, the atmosphere is as clear as that of a tramontana day in an Italian winter, and the air is indescribably elastic. The comfortable Hôtel d'Angleterre stands in the Kongens Nytorv, a modern square, with trees surrounding a statue in the centre, but there are glimpses of picturesque shipping down the side streets, and hard by is a spire quite ideally Danish, formed by three marvellous dragons with their tails twisted together in the air. Tradition declares that it was moved bodily from Calmar, in the south of Sweden. It rises now from a beautiful building of brick erected in 1624 by Christian IV., brother-in-law of James I. of England, and used as the Exchange.

Not far off is the principal palace—Christiansborg Slot, often rebuilt, and very white and ugly. It was partially destroyed by fire in 1884. Besides the royal residence, its vast courts contain the Chambers of Parliament, the Royal Library, and a Picture Gallery chiefly filled with the works of native artists, amongst which those of Marstrand and Bloch are very striking and well worthy of attention.

THE DRAGON TOWER, COPENHAGEN.

A queer building in the shadow of the palace, [69]which attracts notice by its frescoed walls, is the Thorwaldsen Museum, the shrine where Denmark has reverentially collected all the works and memorials of her greatest artist—Bertel Thorwaldsen. Though his family is said to have descended from the Danish king Harold Stildetand, he was born (in 1770) the son of one Gottschalk, who, half workman, half artist, was employed in carving figures for the bows of vessels. [70]From his earliest childhood little Bertel accompanied his father to the wharfs and assisted him in his work, in which he showed such intelligence that in his eleventh year he was allowed to enter the Free School of Art. Here he soon made wonderful progress in sculpture, but could so little be persuaded to attend to other studies that he reached the age of eighteen scarcely able to read. In his twenty-third year he obtained the great gold medal, to which a travelling stipend is attached, and thus he was enabled to go to Rome, where, encouraged at first by the patronage of Thomas Hope, the English banker, he soon reached the highest pitch of celebrity. Denmark became proud of her son, so that his visits to his native town in 1819 and 1837 were like triumphal progresses, all the city going forth to meet him, and lodging him splendidly at the public cost; but his heart always clung to the Eternal City, which continued to be the scene of his labours. Of his many works perhaps his noble lion at Lucerne is the best known. He never married, though he was long attached to a member of the old Scottish house of Mackenzie, and he died on a visit to Copenhagen in 1844.

In accordance with Thorwaldsen's own wish, he rests in the centre of his works. His grave has no tombstone, but is covered with green ivy. All around [71]the little court which contains it are halls and galleries filled with the marvellously varied productions of his genius, arranged in the order of their execution—casts of all his absent sculptures and many most grand originals. Especially beautiful are the statue of Mercury, modelled from a Roman boy, of which the original is in the possession of Lord Ashburton, and the exquisite reliefs of the Ages of Love, and of Day and Night, the two latter resulting from the inspiration of a single afternoon. But all seem to culminate in the great Hall of Christ, for though the statues here are only cast from those in the Vor Frue Kirche, they are far better seen in the well-lighted chamber than in the church. The colossal figures of the apostles lead up to the Saviour in sublime benediction; perhaps the statues of Simon Zelotes and the pilgrim S. James are the noblest amongst them. In the last room are gathered all the little personal memorials of Thorwaldsen—his books, pictures, and furniture.

THE ROSENBORG PALACE, COPENHAGEN.

The Museum of Northern Antiquities should also be visited and the Tower of the Trinity Church, with a roadway inside making an easy ascent to the strange view of many roofs and many waters which is obtained from the top. But the most delightful place in Copenhagen is the Palace of Rosenborg, standing at the end of a stately old garden—where it was built by Inigo [72]Jones for Christian IV., and containing the room where the king died, with his wedding dress, and most of his other clothes and possessions. This palace-building monarch, celebrated for the drinking bouts in which he indulged with his brother-in-law, James I. of England, was the greatest dandy of his time, and before we leave Denmark we shall become very familiar with his portraits, always distinguished by [73]the wonderful left whisker twisted into a pigtail falling on one side of the chin. Other rooms in Rosenborg are devoted to each of the succeeding sovereigns, and filled with relics and memorials which carry one back into most romantic corners of Danish history, the ever-alternate succession of Christians and Fredericks making a most terrible bewilderment, down to the two English queens, Louisa the beloved and Caroline Matilda the unfortunate. Most curious amongst a myriad objects of value are the three great silver Lions—'Great Belt, Little Belt, and Sound'—which, by ancient custom, appear as mourners at all the funerals of the sovereigns, accompanying them to Roeskilde and returning afterwards to the palace.

Those interested in such matters will wander as we did through the more ancient parts of Copenhagen in search of old silver and specimens of the older Copenhagen china. Formerly the china imitated that of Miessen, but it has now a more distinctive character, and is chiefly used in reproducing the works of Thorwaldsen. Copenhagen has no other especial manufactures.

No visitors to the Danish capital must omit a visit to Tivoli, the pretty odd pleasure grounds—very respectable too—near the railway station, where all kinds of evening amusements are provided in illuminated[74] gardens and woods by a tiny lake, really very pretty. Here we watched the cars rushing like a whirlwind down one hill and up another, with their inmates screaming in pleasurable agony; and saw the extraordinary feats of 'the Cannon King,' who tossed a cannon ball, catching it on his hands, his head, his feet—anywhere, and then stood in front of a cannon and was shot, receiving in his hands the ball, which did nothing worse than twist him round by its force.

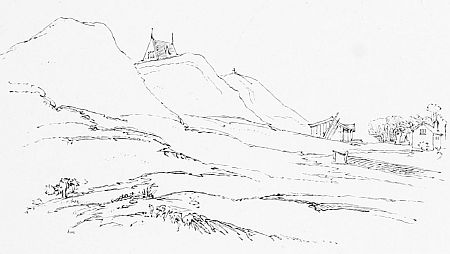

ROESKILDE.

One day we went out—an hour and a half by rail—to Roeskilde, where a church was first founded by William, an Englishman, in the days of King Harold Blaatand (Blue-tooth), brother of Canute the Great. It is dedicated to S. Lucius, because tradition tells that a terrible dragon, who infested the neighbouring fiord and banqueted on the inhabitants, was destroyed for ever when the head of the holy Pope S. Lucius was brought from Rome and presented for his breakfast. The tall spires of the cathedral rise, slender and grey, from the little town, and beneath, embosomed in sweeping cornfields, a lovely fiord stretches away into pale blue distances. Endless kings and queens are buried at Roeskilde. The earlier sovereigns have glorious tombs, amongst which the most conspicuous is that of Queen Margaret—'the Semiramis of the North,' who, born in the prison of Syborg, where her [75]unhappy mother Queen Helwig was imprisoned by Waldemar Atterhag, and allowed to run wild in the forest in her childhood, lived to become one of the wisest of Northern sovereigns, and to unite, by the Act known as 'the Union of Calmar,' the crowns of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, which attained unwonted prosperity under her sway. There are effigies of Frederic II. and Christian IV., the grandfather and uncle of our Charles I., which recall his type of countenance and have the same peaked beard. Christian IV., the great palace-builder, whose birth was believed to have been prophesied by the mermaid Isbrand, was born (April 12, 1577) under a hawthorn tree on [76]the road between Frederiksborg and Roeskilde, as his mother, Sophia of Mecklenbourg, insisted on taking walks with her ladies in waiting far longer than was prudent. This king, his father, and all the later members of his royal house lie, not in their tombs, but in gorgeous coffins embossed with gold and silver upon the floor of the church, which has a very odd effect. The entrance of one of the private chapels is a gate with a huge figure, in wrought ironwork, of the devil with his tail in his hand. In another chapel are fine works of Marstrand (1810-75), the best of the pupils of Eckersberg, who gave the first stimulus to the art of painting in Denmark, where it has since attained to great eminence.

THE CASTLE OF FREDERIKSBORG.

The district around Roeskilde, and indeed the greater part of Denmark, is devoted to corn, for there is no country in Europe, except England and Belgium, which can compete with this as a corn-grower. It is curious that though the neighbouring Sweden and Norway are so covered with pines, no conifer will grow in Denmark except under most careful cultivation. The principal native tree is the beech, and the beech woods are nowhere more beautiful than in the neighbourhood of Copenhagen. The railway to Elsinore passes through the beautiful beech forests which are familiar to us through the stories of Hans [77]Christian Andersen. Here, near a little roadside station, rises the Hampton Court of Denmark, the great Castle of Frederiksborg, the most magnificent of the creations of Christian IV., which John of Friburg erected for that monarch, who looked personally into the minutest details of his expenses, and so raised this structure, glorious as it is, with an economy which greatly astonished his thrifty parliament. In the depths of the beech woods is a great lake, in the centre of which, on three islands united by bridges, rises the palace, most beautiful in its time-honoured hues of red brick and grey stone, with high roofs, richly sculptured windows, and wondrous towers and spires. Each view of the castle seems [78]more picturesque than the last. It is a dream of architectural beauty, to which the great expanse of transparent waters and the deep verdure of the surrounding woods add a mysterious charm. A gigantic gate tower admits the visitor to the courtyard, where Christian IV., with his own hand, chopped off the head of the Master of the Mint, which he had established here, who had defrauded him. 'He tried to cheat us, but we have cheated him, for we have chopped his head off,' said the King. Inside, the palace has been gorgeously restored since a great fire by which it was terribly injured in 1859. The chapel, with the pew of Christian IV.—'bedekammer,' prayer chamber, it is called—is most curious. There is a noble series of the pictures of the native artist Carl Bloch, recalling the works of Overbeck in their majesty and depth of feeling, but far more forcible.

A drive of four miles through beech woods leads to the comfortable later palace of Fredensborg, built as 'a Castle of Peace' by Frederick IV. and Louisa of Mecklenbourg, with a lovely garden, and a view of the Esrom lake down green glades, in one of which is a mysterious assembly of stone statues in Norwegian costumes.

CASTLE OF ELSINORE.