The Project Gutenberg EBook of Emperor William First, by A. Walter

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Emperor William First

The Great War and Peace Hero (Life Stories for Young People)

Author: A. Walter

Translator: George P. Upton

Release Date: June 22, 2020 [EBook #62451]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EMPEROR WILLIAM FIRST ***

Produced by D A Alexander, Stephen Hutcheson, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

EMPEROR WILLIAM FIRST

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

A. Walter

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1909

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1909

Published August 21, 1909

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

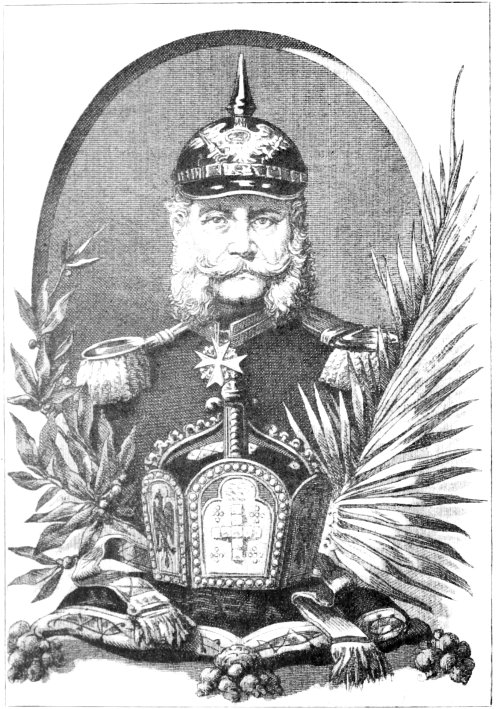

Upon the titlepage of the original of this little volume stands inscribed, “A life picture for German youth and the German people.” It might, with equal pertinency, have been written, “A life picture for all youth and all people.” Emperor William First was a delicate child, but was so carefully nurtured and trained that he became one of the most vigorous men in Germany. At an early age he manifested a passionate interest in everything pertaining to war. In his youth he received the Iron Cross for bravery. He served under his father in the final wars of the Napoleonic campaign, and in his twenty-third year mastered not only the military system of Germany, but those of other European countries. During the revolutionary period of 1848 he was cordially hated by the Prussian people, who believed that he was wedded to the policy of absolutism, but before many years he was the idol of all his kingdom, and in the great war with France (1870), all Germans rallied round him.

After the close of this war he returned to Berlin and spent the remainder of his days in peace, the administration of internal affairs being left largely to his great coadjutor, Prince Bismarck. In connection with Von Moltke, these two, the Iron Emperor and the Iron Chancellor, made Germany the leading power of Europe. In simpleness of life, honesty of character, devotion to duty, love of country, and splendor of achievement, the Emperor William’s life is a study for all youth and all people.

G. P. U.

Chicago, May 10, 1909.

King Frederick William Second was still upon the throne of Prussia when his son and successor, afterward Frederick William Third, was married to the lovely Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The memory of this noble pair is treasured in every Prussian heart, and their self-sacrificing devotion to the people, their benevolence and piety, will serve as a shining example for all time.

On the fifteenth of October, 1795, a son was born to them, the future King Frederick William Fourth, and on the twenty-second of March, 1797, the Crown Princess gave birth to a second son, whose name was destined to be inscribed in golden letters in the book of the world’s history. Although a handsome boy, his health was so delicate as to cause his parents much anxiety, and it seems almost like a special dispensation of Providence that he should have lived to an age far beyond that usually allotted to the fate of mortals.

On the third of April the christening took place in the Crown Prince’s palace. Chief Councillor of the Consistory Sack stood before the altar, which was ablaze with lighted tapers, and ranged before him in a wide semicircle were the priests, the Crown Prince, and the godparents. Others present were the King and Queen; the widowed Princess Louise, a sister of the Crown Princess and afterward Queen of Hanover; Princes Henry and Ferdinand of Prussia, brothers of Frederick the Great, with their wives; Princes Henry and William, brothers of the Crown Prince; their sister, the Electress of Hesse-Cassel; Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt, and the hereditary prince Frederick William of Orange. Proxies had been sent by the Czar and Czarina of Russia, Prince William of Nassau, the Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt, and the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel. The principal governess, Countess Voss, handed the child to the King, who held him during the ceremony. He received the names Frederick William Louis, with the understanding that William was the one by which he should be known.

On the sixteenth of November of that same year Frederick William Second was gathered to his forefathers, and the father of our hero ascended the throne of Prussia. Their assumption of royal honors made no change in the simplicity of the august pair’s affection for each other or their devotion to their children, and whenever time and opportunity permitted, they gladly laid aside the oppressive form and ceremony of the court for the pure and simple pleasures of home life. Every morning and evening they went hand in hand to the nursery to enjoy the growth and development of their children, or, bending with loving caresses over their cradles, committed them to the fatherly care of the Almighty. The simple cradle with its little green curtains in which Prince William dreamed away his infancy is still preserved in the Hohenzollern Museum at the Monbijou Palace, a touching reminder of the delicate child who was afterward to be so famous and to serve as an instrument for the fulfilment of the mighty decrees of Providence for the welfare of his people.

The early years of Prince William’s life passed happily and peacefully by. Watched over with tenderest love and care by his noble parents, their devotion and piety, their readiness to sacrifice themselves for each other or for their people, their prompt and cheerful fulfilment of duty, and the courage that never failed them even in the darkest hours, all made a deep impression on the child’s sensitive nature and helped to form the character that distinguished the heroic Emperor up to the last days and hours of his life.

There was little prospect at that time of William’s ever wielding the sceptre, for his elder brother was a strong, healthy lad, and the crown seemed in all human probability likely to descend to him and his heirs. It was important, therefore, for the younger son to choose some vocation which would enable him to be of use to the Fatherland and prove himself worthy of his illustrious ancestors.

The Prince’s devoted tutor, Johann Friedrich Gottlieb Delbrück, carefully fed his mind with the history and glories of the house of Brandenburg, a study of which he never tired and to which he applied himself with untiring zeal. Learning from this that a well-disciplined standing army, firmly supported by public sentiment, was the first and most important requisite for the advancement and maintenance of the monarchy, he determined to devote himself to a military career and use all his energy to fit himself for that high and difficult calling, that he might furnish a stout support to his brother’s throne. But he had shown a natural fondness for soldiers at an early age, long before arriving at this maturer resolution, an inclination which his father had carefully encouraged. The two little Princes, with their cousin Frederick, son of the deceased Prince Louis, received their first military instruction in Potsdam from a noncommissioned officer of the first Battalion of the Guard, named Bennstein, and in Berlin from Sergeant Major Cleri of the Möllendorf Regiment. The King was often present at these exercises to note their progress, praise or criticise, and as a reward for their industry, arranged a delightful surprise for them.

It was Christmas Eve of the year 1803. In the royal palace at Berlin the lighted Christmas-tree glittered and sparkled, its branches bending with the weight of gifts provided by the royal parents for their children. All was silent, for the family were still at divine service, with which they always began the celebration of the holy festival. Suddenly the clear stroke of a bell sounded through the quiet room, the great doors flew open as if of their own accord, and the King and Queen entered with their excited children. A perfect sea of light streamed toward them from the huge tree that towered almost to the ceiling and filled the air with its spicy fragrance, while red-cheeked apples and gilded nuts nodded a friendly greeting from its branches. Here the beautiful Louise, Prussia’s beloved Queen, reigned supreme, gayly distributing gifts and enjoying the delight of her precious children, while the King stood quietly by, his eyes shining with fatherly happiness. All at once the six-year-old William gave a shout of joy. Before him, carefully tucked away under the boughs of the tree, he saw a gay little uniform. What joy! what bliss! The red dolman with its white cords and lacings, the blue furred jacket, the bearskin cap, and the sabre filled his cup of happiness to overflowing, and the happy little fellow could find no words to thank the kind parents who had so unexpectedly granted his heart’s desire. It was the uniform of the Rudorff Regiment, now the Ziethen Hussars, and the Christ-child had brought his brother, the Crown Prince, that of the body-guard, and his cousin Frederick that of a dragoon. The next morning the three boys dressed up in their new costumes and the delighted father presented them to the Queen as the youngest recruits in his army. But none of them was so proud as William, and very fine he looked in his first soldierly dress.

Two years later he saw the uhlan regiment Towarczysz, at that time the only one in Prussia, and was so charmed with its singular uniform that he begged his father for one like it. The King, always ready to encourage his military tastes, granted his wish, and from that time he alternated between a uhlan and a hussar. That year he also saw the famous old dragoon regiment Ansbach-Baireuth of which the Queen was commander, and the sight of his mother in her regimental colors made a deep impression upon him.

Though he was passionately devoted to soldiering, childish sports and games were not neglected, especially during the Summer, when the royal family went for a few weeks to their country place at Paretz. Here the King and Queen encouraged their children to associate freely with all classes—from the village children to future army officers at military schools. It was naturally among the latter that the Princes found most of their playmates. The knowledge of the people he gained in this way proved a great and lasting benefit to Prince William.

Thus happily and peacefully, surrounded by luxury and splendor, watched over with tenderest care, our hero’s life slipped by till the end of his eighth year, when a storm burst over the country that shook the Prussian throne to its foundations.

The throne of France was occupied at that time by the insatiable Napoleon I. Born on the island of Corsica, the son of an advocate, he entered the French army during the Revolution and rose step by step until by his remarkable talents and ability he attained the highest honors of state. His ambition was to make France mistress of the world, and aided by the blind devotion of the people he seemed in a fair way of realizing this dream, for one country after another succumbed with astonishing rapidity to his victorious legions.

Prussia was spared for some time, but in 1806 King Frederick William Third, unable for his own honor or that of his country longer to endure Napoleon’s aggressions, was reluctantly forced to declare war, and the country’s doom was sealed. Deluded by the traditions of former glories under the great Frederick, the army and its leaders thought it would prove an easy task for the battalions that had once withstood the onset of half Europe to protect the frontiers of the Fatherland against the Corsican conqueror, but disaster followed swiftly. The guns of Jena and Auerstädt scattered those golden mists of self-delusion and betrayed with startling clearness the degeneracy of the military organization, which, like the machine of government, bore little trace of Frederick the Great’s influence save in outward forms.

The defeat of October 14, 1806, decided the fate of Prussia. Like a roaring sea the French swept over the country, and two days later it became necessary for the safety of the royal children to remove them from Berlin. Their nearest refuge was the castle at Schwedt on the Oder, where their mother joined them, prepared to share with her darlings the cruel fate that had befallen them. Sitting with her two eldest sons and their tutor Delbrück that evening, she spoke those stirring words that proved such a help and inspiration to Emperor William in after years.

“In one day,” she said, “I have seen destroyed a structure which great and good men have labored for two hundred years to build up. There is no longer a Prussian kingdom, no longer an army, nor a national honor. Ah, my sons, you are already old enough to appreciate the calamity that has overtaken us. In days to come, when your mother is no longer living, think of these unhappy times and weep in memory of the tears I now am shedding. But do not weep only! Work, work with all your strength! You yet may prove the good geniuses of your country. Wipe out its shame and humiliation, restore the tarnished glory of your house as your ancestor, the great Elector, avenged at Fehrbellin his father’s disgraceful defeat in Sweden! Do not allow yourselves to be influenced by the degeneracy of the age! Be men, and strive to attain the glorious fame of heroes! Without such aims you would be unworthy the name of Prussian princes, successors of the great Frederick; but if all your efforts are powerless to uplift your fallen country, then seek death as Prince Louis Ferdinand sought it!”

Their stay in Schwedt was but a short one. The rapid advance of the French army, driving the retreating Prussians before them, compelled the Queen and her children to flee to Dantzig and Königsberg, where they would be safe for a time at least. But what a journey it was! There was no time to make any preparations for their comfort. Day and night they pressed on, without stopping to rest, in any kind of a vehicle that could be obtained, over rough roads and through a strange part of the country, often suffering from hunger and thirst, their hearts full of sorrow and anxiety for the beloved Fatherland.

Emperor William used to relate an incident connected with this journey which makes a touching picture of those dark days. “While my mother was fleeing with us from the French in that time of tribulation,” he said, “we had the misfortune to break one of the wheels of our coach, in the middle of an open field. There was no place for us to go, and we sat on the bank of a ditch while the damage was being repaired as well as possible. My brother and I were tired and hungry, and much put out by the delay. I remember that I especially, being rather a puny lad, troubled my dear mother greatly with my complaints. To divert our minds, she arose and, pointing to the quantities of pretty blue flowers with which the field was covered, told us to pick some and bring them to her. Then she wove them into wreaths as we eagerly watched her dexterous fingers. As she worked, overcome with thoughts of her country’s sorrowful plight and her own danger and anxiety for the future of her sons, the tears began to drop slowly from her beautiful eyes upon the cornflower wreaths. Smitten to the heart by her distress and completely forgetting my own childish troubles, I flung my arms about her neck and tried to comfort her, till she smiled and placed the wreath upon my head. Though I was only ten years old at the time, this scene remains undimmed in my memory, and after all these years I can still see those blossoms all sparkling with my mother’s tears, and that is why I love the cornflower better than any other flower.”

The cornflower wreaths

At Königsberg the Queen was attacked with a fever, but this did not prevent her from continuing her flight to Memel with her children in January, 1807. It seemed doubtful at one time if she would live to get there, but she insisted upon pressing on, through cold and storm, ill as she was. Once, almost at the point of death, she was forced to spend the night in a poor peasant’s hut, without proper food or covering, the freezing wind blowing through the broken windowpanes and scattering snowflakes on her wretched cot. But God did not forsake the heroic Queen, and she succeeded at last in reaching Memel, there to await the no longer doubtful issue of the war, which cost Frederick William Third half of his kingdom. This sudden change from peace and prosperity to deepest humiliation was the anvil on which Providence forged the sword that was one day to make Germany a united and powerful nation, and some words of the Queen’s, written at this time to her father, are significant and memorable.

“It may be well for our children to have learned the serious side of life while they are young. Had they grown up surrounded by ease and luxury, they would have accepted such things as a matter of course; that must always be so. But alas! their father’s anxious face and their mother’s tears have taught them otherwise.”

Our hero was ten years old when the King was forced to sign the disastrous peace of Tilsit, and according to the usual custom he was raised at this age to the rank of officer. The great event should properly have taken place March 22, 1807, but owing to the unsettled state of the country his father presented him with his appointment on New Years’ Day, just before the royal family left Königsberg for Memel, and he was made ensign in the newly formed regiment of foot-guards. At Christmas he was advanced to a second-lieutenantship, and on June 21, 1808, marched with his regiment back to Königsberg. A report made about this time states: “Prince William, during his first two years of service with the Prussian infantry, has become familiar with every detail of army life and is already heart and soul a soldier,”—a tribute well deserved by the young officer, for he was faithful and industrious and devoted to his profession. The two following years that the royal family remained in Königsberg were an important period in the life of Prince William. The sole tuition of Delbrück no longer satisfied the Queen, and on the advice of Baron von Stein, she appointed General Diericke and Colonel Gaudy as governors for the Crown Prince, and Major von Pirch and Professor Reimann for Prince William. At the same time Karl August Zeller, a pupil of the Queen’s honored Swiss teacher Pestalozzi, was summoned to Königsberg and given charge of the school system. He also assisted in the education of Prince William, whose untiring zeal and industry caused him to make steady and rapid progress in all branches of learning. His best efforts, however, were given to his military duties, and he eagerly treasured up everything that was said at court of famous generals and heroes.

On November 12, 1808, he paraded for the first time with his regiment. In September of the following year he was present at the placing of the memorial tablets to the first East Prussian Infantry in the palace chapel at Königsberg, and after the court had returned to Berlin, he entered that city with his regiment on his parents’ wedding anniversary, December 24, 1809. It was a melancholy home-coming, and never again did our hero make so sad an entry into his capital, for in spite of the joy with which the citizens welcomed the return of their beloved sovereigns once more, the country’s shameful bondage under the yoke of Napoleon lay heavily on all hearts. No one felt the disgrace more keenly than Queen Louise, however: it rankled in her bosom and gradually consumed her strength till her health began to give way under it.

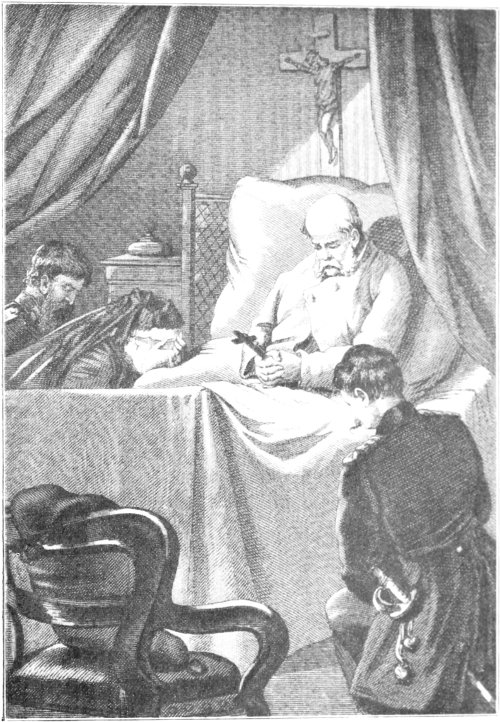

In the Summer of 1810 she visited her father at Strelitz, whither the King soon followed her, and it was decided to make a long stay at the ducal castle of Hohenzieritz, hoping the change and rest might benefit the Queen. Soon after her arrival, she was taken seriously ill with an acute attack of asthma, but recovered sufficiently by the first of July for the King to return to Charlottenburg, where the royal family were then in the habit of spending the Summer. For some days she seemed much better, but the attacks of pain and suffocation soon returned, and on the nineteenth of July the King hastened back to Hohenzieritz, where he found his wife fully conscious but so altered in appearance that he was forced to leave the room, weeping aloud. As soon as he had recovered his self-control he returned to the Queen, who laid her hand in his with the question:

“Did you bring any one with you?”

“Yes, Fritz and William,” replied the King.

“Ah, God! what joy!” she cried. “Let them be brought to me.”

The two boys came in and knelt beside their mother’s bed. “My Fritz, my William!” she murmured repeatedly. Soon the paroxysms seized her again, the children were led away weeping bitterly, and soon afterward the King closed forever those eyes that had been the light of his life’s dark pathway.

The death of their beloved Queen turned all Prussia into a house of mourning, so deeply did the sorrowful news affect the hearts of her subjects. Still deeper and more lasting, however, was the impression made upon Prince William by the early loss of his adored mother. All through his life her memory was treasured as a holy image in his heart, and to his latest days he never forgot her devotion and self-sacrifice, or that nineteenth of July which deprived him of a mother’s care, his father of the best of wives, and the nation of a noble sovereign and benefactress.

The years passed on, but Prussia did not remain in her deep humiliation, prostrate and powerless. A new spirit began to awake, and through the efforts of such men as Stein and Hardenberg, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, who nobly and without hope of reward devoted themselves to the redemption of the Fatherland, a feeling began to stir throughout the country that the day of deliverance must come. And it did come. Arrogant with his successes and thirsting for fresh conquests, Napoleon in the year 1812 aspired to seize the mighty Russian Empire and add it to his dependencies, but there a check was placed on his victorious career. To be sure he penetrated as far as Moscow, expecting to winter there, but the Russians sacrificed their ancient capital and Napoleon with his troops was driven from the burning city out into the open country in the depth of Winter. The Lord of Hosts seemed to have allied himself with the Russians to destroy the disturber of the peace of Europe, for the Winter was an early and unusually severe one and Napoleon was forced to order a retreat. And what a retreat it was! Day after day, through the heavy snows and the bitter cold, plodded the exhausted soldiers, pursued and harried by the Russians like hunted animals. Of the five hundred thousand men who set out in all the proud assurance of victory, only a few thousands returned again to France. It was a bitter blow to the aspiring conqueror—God himself had dealt out judgment to him! He hastily collected together a new army, it is true, but now all Germany was allied with Russia to defeat the tyrant’s schemes. The glorious war of 1813-1815 was about to begin.

Among those great men who had labored untiringly to emancipate Prussia from the yoke of France, the work of reorganizing the army had fallen chiefly to Scharnhorst.

It had been his idea to train the whole population of the smaller outlying States in the use of arms, and thus continually to introduce fresh forces into the army of forty thousand men which Prussia was allowed to support, to take the place of older and well-disciplined regiments which were dismissed. The news of Napoleon’s disastrous experience in Russia filled the Prussians with new hope and enthusiasm, but the King was slow to determine on any decisive action. Napoleon still had powerful resources at his command, and if the struggle for which the people clamored were to go against them, the ruin of Prussia would be complete. Further delay, however, became at last impossible, and on January 22, 1813, Frederick William left Berlin, where his personal safety was still menaced by French troops, and removed the court to Breslau. An alliance was concluded, February 28, between Russia and Prussia, and on March 17 war was declared against Napoleon. That same day General Scharnhorst’s ordinance in regard to the militia was carried into effect and the large body of well-drilled men which he had been quietly training for so long, took their place in the newly formed army.

Shortly before this, on his deceased wife’s birthday, March 10, the King established the order of the Iron Cross.

“With God for King and Fatherland!” was the watchword with which Prussia entered the struggle that was to lift her to her old position of power and independence or end in hopeless ruin. The King issued a call for troops and the whole nation responded. Not a man but would gladly die rather than longer endure the shame of subjection. The lofty spirit of their departed Queen seemed still to inspire the hearts of the people, for they arrayed themselves against the conqueror who had chosen the heroes of Pagan antiquity for his models, with a Christian faith and devotion rarely equalled in the history of the world. Prince William too longed with all his heart to take part in the liberation of Prussia and with tears in his eyes besought his father to allow him to take the field, but out of regard for his son’s health the King was obliged to refuse his prayer, and he remained in Breslau, in bitter discontent, anxiously waiting and hoping for news from the seat of war, at that time so difficult to obtain and so slow in arriving. Even his advance to a first-lieutenantship in the course of the summer failed to cheer him, for he felt that he had done nothing to deserve it. But after the battle of Leipzic, in which the French were routed and driven back across the Rhine, the King returned to Breslau and, handing the Prince a captain’s commission, placed on his shoulders with his own hands the epaulettes then just introduced for army officers, and told him to prepare to join the army. This was joyful news indeed! On to France, on against the foe that so long had held the Fatherland in bondage and sent his adored mother to a premature grave! His heart beat high with pride and courage, and he could hardly wait for the day of departure, which was finally set for November 8.

The French were already driven out of Germany at that time and the victorious allies had pursued them into their own country. On January 1, 1814, the King and his son reached Mannheim, on the Rhine, and were soon across the borders and in the midst of the seat of war. From Brienne and Rosny sounded the thunder of cannon, and at Bar-sur-Aube on February 27 Prince William was permitted for the first time to take part in active service.

Early on the morning of that day the King sent for his two sons (the Crown Prince had been with the army from the beginning of the war) and said to them: “There will be a battle to-day. We have taken the offensive and there may be hot work. You shall watch it. Ride on and I will follow, but do not expose yourselves to danger unnecessarily. Do you understand?”

The brothers dashed off to General Prince Wittgenstein, where their father joined them, and they were soon in the middle of the fight and in constant danger of their lives. Suddenly the King turned to Prince William. “Ride back and find out what regiment it is over yonder that is losing so many men,” he ordered. Like a flash William was off, followed by admiring glances from the soldiers as he galloped calmly through the hail of bullets, obtained the desired information, and rode slowly back. The King made no comment, but General Wittgenstein, who had watched the Prince with apprehension, gave him a kindly glance and shook him warmly by the hand, William himself seeming quite unconscious that he had been in such danger and had just received his baptism of fire.

On March 10, his mother’s birthday, he received from his father’s hand the Iron Cross, and a few days before this the royal allies of Prussia and Russia had bestowed on him the fourth class of the Order of Saint George for his bravery. These two decorations, which can only be won under fire, made the Prince realize for the first time the real meaning of the incident at Bar-sur-Aube.

“Now I know,” he said, “why Herr von Jagow and Herr von Luck pressed my hand and why the others smiled so significantly.”

The Emperor wore these two little crosses to the end of his life, with special pride, as the first honors he ever won, and would never have them replaced by new ones. They were precious relics of his baptism of fire at Bar-sur-Aube.

Swiftly the tide of war rolled on. Battle after battle was won. Napoleon was dethroned and banished to the island of Elba, and on March 31, 1814, Prince William made his first victorious entry into the enemy’s proud capital. Here he took up his quarters in the Hotel of the Legion of Honor and on May 30 received the rank of Major in the army. After visiting England and Switzerland with his father in the course of the Summer, our hero returned to Potsdam on the King’s birthday (August 3), where he was joyously welcomed by his sisters. The following year Napoleon escaped from Elba and regained possession of the throne of France, only to exchange it after a sovereignty of one hundred days for the lonely island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic Ocean.

On June 8 of this year (1815) the confirmation of Prince William took place, having been postponed till that date on account of the war. In the palace chapel at Charlottenburg he took the usual vows and laid down for himself at the same time those principles of life and conduct that are a splendid witness to his nobility of mind, his seriousness of purpose, his sincere piety and faith in the Almighty, and his lofty conception of the duties of his high calling.

After his confirmation Prince William was hastening back to the seat of war when the news of Napoleon’s defeat and banishment reached him. Nevertheless he kept on and entered Paris again with the army. During the three months that he remained there this time he suffered from a sharp attack of pleurisy, from which he quickly recovered, however. This was the last evidence of his early delicacy, for henceforth he enjoyed the most robust health and was able to endure all the hardships of a soldier’s life, devoting himself to his chosen profession with the greatest energy and enthusiasm and striving earnestly to advance the military power and standing of Prussia to a place among the great nations of Europe.

Even during his father’s reign, as well as that of his brother, he was considered the soul of the army and looked upon by the troops as a pattern of all the military virtues, while with his indefatigable activity in all branches of the service he rose rapidly to the highest commands. Frederick William Third was not slow to recognize his son’s abilities, for when in 1818 he made a journey to Russia with the Crown Prince, he intrusted the entire management of military affairs to him during his absence. The following year the Prince received a seat and voice in the ministry of war, thus enabling him to acquire as thorough a knowledge of army organization and administration as he had already gained in practical experience. Thereafter he took part in all military conferences, while special details and commissions of inspection familiarized him by personal observation with army affairs in general.

The close family ties between the royal houses of Prussia and Russia, brought about by the marriage of the Princess Charlotte, William’s sister, to the Grand Duke Nicholas, afterwards Czar, caused our hero to be drawn into active intercourse with St. Petersburg. At the time of the wedding, which took place in Berlin, it fell to his share to accompany his sister to her future home and represent the Prussian throne at the festivities there. He was received with great honors in St. Petersburg and improved the occasion by attending the military manœuvres which were held there and at Moscow. His personal relations with the Russian court were very intimate and were the cause of frequent visits thither in the ensuing years.

The routine of his professional duties was often varied by journeys and visits required by the service—such as that to Italy in 1822, and a long one made in 1826 with his younger brother Charles to the court of Weimar, from which the two Princes carried away the most delightful recollections, especially of the Princesses Marie and Augusta, whose acquaintance they had made on that occasion. Nor was it to end in memories, for Prince Charles’s betrothal to the Princess Marie was soon announced, and on May 26, 1827, the young couple were married. As for William, several visits to the hospitable grand-ducal court convinced him that no other princess possessed to such a degree the qualities necessary to his life’s happiness as the modest and amiable Princess Augusta, and they became betrothed in February, 1829, the marriage following on June 11 of that year.

In May Prince William journeyed to St. Petersburg to invite his sister and her husband to the wedding, and on his return went directly to Weimar to escort his fair bride to Berlin. On June 7 the Princess Augusta bade farewell to her beloved home; two days later the bridal party reached Potsdam, and on the tenth the state entry from Charlottenburg took place. The Prussian capital had not failed to prepare a royal welcome for Prince William’s bride, the fame of whose virtues had preceded her, and all Berlin was agog to see and greet the lovely Princess and the happy bridegroom. The magnificent wedding lasted for three days, after which the royal pair took possession of the so-called Tauenziensche House which had been assigned to the Prince as his official residence. Later it was bought by him and rebuilt by the architect Langhaus in substantially the form in which the present palace at the entrance of the Linden has become familiar to every German as the residence of the Emperor William First.

The home life of the Prince and Princess was charmingly simple and domestic and their marriage a singularly happy one, founded on mutual love and respect. Both were distinguished for deep religious feeling, a strong sense of duty and the responsibilities of their position, as well as a deep-rooted love of the Fatherland. On October 18, 1831, the anniversary of the battle of Leipzic, the Princess Augusta presented her husband with a son, afterward the beloved Emperor Frederick, whose untimely death was so deeply deplored; and on December 3, 1838, she gave birth to a daughter, Louise Marie Elizabeth, the present Grand Duchess of Baden. These new joys brought also new duties into the lives of the royal parents in the education of their children, to which they devoted themselves with the most loving care. While the father endeavoured to develop in his son the qualities requisite to make a good soldier, the clever mother saw to it that his education should not be military only. She was a constant patroness of art and learning and was determined that her Fritz should have a thorough knowledge of science and be a lover of the fine arts, while her daughter Louise was early taught to employ her time usefully and to become accustomed to serious work under her mother’s guidance.

After 1835 the family began to spend the Summer months at the Schloss Babelsberg on the Havel, the site of which had been discovered by Prince William at the time of some army manœuvres in that neighborhood in 1821. After their marriage the artistic young wife had drawn the plans for a country residence there, which was afterward enlarged considerably, and thus arose the Babelsberg palace. The surroundings were soon converted by expert hands into gardens and a magnificent park, and it became the favorite residence of the Emperor in his later years. He used to spend much time there, and far from wishing to hide its beauties from his subjects, he loved to have people come and wander through the beautiful grounds. The minister of war, Van Roon, indeed, tells how the old Emperor once left his work to permit his study to be shown to some visitors who had come a long distance to gaze on the abode of their beloved sovereign.

On June 7, 1840, that sorely tried monarch Frederick William Third, who had borne so much with and for his people, breathed his last, and the Crown Prince ascended the throne as Frederick William Fourth, William receiving the title of Prince of Prussia as had that brother of Frederick the Great who afterward succeeded him, thus being raised to the rank and dignity of a Crown Prince, for the marriage of Frederick William Fourth was childless.

On June 11 the body of the deceased King was laid to rest in the mausoleum at Charlottenburg beside that of his noble and much-lamented Queen. And now began a period of ferment, difficult to understand by those not directly concerned in it or its after effects. Even at the time of the War of Liberation a feeling of discontent had begun to show itself among the people of Germany at the condition of affairs created by the allies at the so-called Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815. There was an ever-increasing demand for popular representation in the legislature, what is now called the Diet or House of Deputies, and also a closer consolidation of the national strength and resources, such as would be afforded by a German Confederation for the purpose of restoring the Empire to its old power and importance. These ideas, as yet but half-formed and visionary, were agitated, especially by the youth of Germany, with a spirit and enthusiasm that appeared so dangerous to the existing order of things as to require suppression. At the time of the French Revolution of 1830, they began to assume more definite form, though under the paternal rule of Frederick William Third no general movement was attempted by his subjects. With the accession of Frederick William Fourth, however, the time seemed to have come to demand the exchange of an absolute monarchy for a constitutional form of government, and also, perhaps, the reëstablishment of the German Empire; but in both respects their hopes were doomed to disappointment. The King’s refusal to grant the people a voice in the government was as firm as his rejection of the offer of an imperial throne. His action aroused a deep feeling of dissatisfaction throughout the country, which was increased by several years of bad crops and famine, until at last the French Revolution of 1848 lighted the torch of insurrection in Germany also.

Frederick William Fourth had already assigned to his brother, the Prince of Prussia, the responsible post of guardian of the Rhine, and at the outbreak of these disturbances he made him Governor General of the Rhenish provinces and Westphalia. Before the Prince had left Berlin, however, the uprising had spread to that city also, so he remained in close attendance upon the King, taking a leading part in his councils as first Minister of State. Frederick William Fourth was much disturbed by such an unheard-of state of affairs in Prussia, and possibly failed to appreciate the significance of the outbreak, but rather than come to open conflict with his people he had all the troops sent away from Berlin. Bitter as the recollection must be, it remains a lasting honor to the Prussian army that this trying order was obeyed without a murmur or complaint, and adds another laurel to those since won on many a hard-fought field. The removal of the troops gave the insurgents free scope for a time, and the efforts of the leaders to direct the anger of the deluded populace against the army, that stanch and loyal bulwark of the throne, resulted in setting the turbulent masses against the Prince of Prussia likewise, who was well known as the army’s most zealous friend and patron. They even went so far as to threaten to set fire to his palace, but a few patriotic citizens succeeded in restraining them at the critical moment. To avoid any further occasion for such excesses, the King sent his brother away to England, where he remained until the storm had subsided, returning in May, 1848, to Babelsberg, where he spent several months in retirement. The King was finally forced to recall the troops, then under the command of General von Wrangel, to quell the tumult in Berlin, and shortly afterwards Prussia was given its present constitution, by which the people were granted a chamber of representatives.

The insurrection of 1848, meanwhile, had spread throughout the country and led to a revolution in Baden, which overthrew the existing government and assumed such serious proportions that the Grand Duke besought the help of King Frederick William Fourth, who at once despatched his brother, the Prince of Prussia, to Baden with an army. It was William’s first experience as a commander.

In June, 1849, he proceeded from Mainz to the Palatinate of Bavaria, where he was welcomed with open arms by the inhabitants. With the assistance of his gallant young nephew Frederick Charles, he soon quickly crushed the insurgents who were besieging the Palatinate and pushed on across the Rhine to Baden, where in a succession of engagements he proved an inspiring example of coolness and courage to his enthusiastic troops. After the fight at Durlach, the townspeople brought out bread and wine for the victorious Prussians. The Prince was also offered a piece of bread, which he was about to eat with relish when he saw a hungry soldier watching him with longing glances. Quickly breaking it in two he held out half to the man, saying kindly, “Here, comrade, take some too!”

It was by such acts as this that he won the devotion of his soldiers. On June 25 he entered the capital, Carlsruhe, and was hailed with joy by the citizens, while the leader of the rebellion retired to the castle of Rastall, where, after a few more unsuccessful resistances, the greater part of the insurgents also took refuge. The Prince immediately laid siege to the place, and with such good results that on July 23 it surrendered at discretion, and the Prussians took possession the same day. On August 18 the Grand Duke of Baden returned to his capital, accompanied by the Prince of Prussia, to whom he gave public thanks as the restorer of order in the country, and soon after William set out on his return to Berlin, where he was welcomed with enthusiasm by his family, the populace, and above all by the army.

His duties as military governor of Westphalia and the provinces of the Rhine required him to take up his residence at Coblentz, where he remained till 1857, with occasional journeys made in the interest of the service or for the government. These were unsettled and not very pleasant times, for Austria was perpetually seeking to undermine the power of Prussia and more than once the sword was loosened in its sheath. But there were bright spots also in the lives of the princely pair, such as the marriage of their daughter Louise to the Grand Duke of Baden. Another favorite wish was gratified by the alliance of Prince Frederick with the Princess Royal, Victoria of England, in 1857. Fresh troubles occurred in this year also, for on the occasion of some army manœuvres at Giebichenstein, King Frederick William Fourth was stricken with apoplexy and his brother was appointed to represent him at the head of the government. At first it was hoped that the trouble might be relieved, and the arrangement was made for three months only; but the apoplectic fits continued at intervals, and at the end of a year, finding his condition worse rather than improved, the King was forced to make the Prince of Prussia Regent of the kingdom. Four years later Frederick William Fourth was released from his sufferings, and his brother ascended the throne of Prussia as William First.

Our hero was nearly sixty-four years old when he was called by Providence to assume this exalted position, an age at which men usually begin to look about for a quiet spot wherein to end their days in peace and freedom from care. But for King William, though already on the threshold of age, this was out of the question. This Nestor among German princes had been chosen as an instrument for the restoration of national unity and power. It was his task, as head of the “Holy German Empire,” to overthrow all her enemies and crown her arms with victory and fame. And nobly did the venerable monarch fulfil this trust, keeping a watchful eye on the interests and welfare of the Fatherland for more than twenty-seven years.

The aims and hopes with which he began his reign are set forth in the proclamation issued to his people at that time. It hints too at the serious struggle he saw approaching, in which Prussia would have to fight for her existence against the neighboring countries, jealous of her growing power. It had been the labor of his life to provide the country with a strong, well-disciplined army; his task now as sovereign was to make it equal in size to any demand that might be made upon it. During his regency he had tried to secure the consent of the Diet to a large increase in the standing army, and preliminary measures had already been taken to this effect, but after the Prince’s accession to the throne the House of Deputies withdrew its consent and absolutely refused to grant the necessary appropriation. This was a hard blow to the King, but he felt that his duty to the country required him to persist in his demands, a decision in which he was loyally upheld by his recently appointed councillor, Otto von Bismarck, a man of remarkable talents and ability, to whom might well be applied the poet’s words:

“He was a man, take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again.”

For a time, however, their efforts met with no results, the Diet remaining firm in its refusal, and finally disclaiming any participation in the policy of the government, domestic or foreign. Not until great events had occurred, not until splendid proofs had been furnished of the wisdom of the King’s judgment, were the representatives convinced that the aims of the government were for the country’s best good. Nor was it long before an opportunity for such proofs was offered.

For many years the Kings of Denmark had appropriated to themselves the title of Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, though more as a matter of form than of real sovereignty, for the two sea-girt duchies had retained their own constitution, their laws, and their language. Within the space of ten years, however, it had become more and more apparent that Denmark was aiming at complete absorption and suppression of their nationality. In 1840, and again in 1850, they had struggled to retain their independence, but in vain, being too weak themselves and meeting with insufficient support from their German brethren, who at that time had all they could manage with their own affairs. When, however, on November 15, 1863, King Frederick Seventh of Denmark died and Christian Ninth ascended the throne, Germany decided to interfere in behalf of the duchies. As the various States could come to no agreement, Prussia and Austria, as the two leading powers, took matters into their own hands. The Danish King was called upon to evacuate Holstein within forty-eight hours and to withdraw the form of government introduced into Schleswig, and on his refusal to comply with these demands Schleswig was at once invaded. The general command of the expedition was given to Von Wrangel, Prince Frederick Charles leading the Prussian troops, Field Marshal Lieutenant von Gablenz the Austrians who had come on through Silesia and Brandenburg.

On February 1, 1864, Wrangel gave the order to advance “in God’s name!”—an order which proved the signal for a succession of heroic deeds that covered the German army with glory, for from the Danish War sprang that between Prussia and Austria two years later, and in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War. The first of February, 1864, therefore, surely deserves a place in the pages of history as the starting point of the glorious achievements of the German army and the victorious career of its royal commander.

King William himself took no active part in the Danish War. Only about one and a half army corps were mobilized, too small a force to be under the command of the sovereign of so powerful a nation as Prussia. But when after a number of victorious engagements Prince Frederick Charles succeeded in storming Düppel and capturing all the supposedly impregnable intrenchments, thus proving that Prussia’s old valor still survived in a younger generation, King William could no longer keep away from his victorious troops. His arrival in Schleswig was hailed with joy by the people as well as the army, and at Grevenstein he held a review of the columns that had fought so brilliantly at the storming of Düppel, praising and thanking them personally for their bravery. He also visited the hospitals, encouraging the wounded with his presence and kindly words of cheer. The people of Schleswig were assured that their affairs would be brought to a happy issue, and a feeling of confidence in the speedy liberation of their brethren from the power of Denmark spread throughout Germany.

And so it proved, for on June 28 the enemy’s defeat was completed by the capture of the island of Alsen, used by the Danes as a storehouse for arms and provisions. A truce was proclaimed, and on October 30, 1864, the Peace of Vienna was concluded, by which the King of Denmark renounced all his rights to the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg in favor of the King of Prussia and the Emperor of Austria, and agreed to recognize whatever disposition the allies should make of the three States. This treaty, by completely freeing the duchies from the power of Denmark, realized one of the dearest wishes of the people, a wish that had long been cherished in the hearts of patriots; while to Germany it gave a greater increase of territory and influence than had fallen to her share for many years.

In spite of this fact, however, the idea of German unity still seemed far from realization owing to the conflicting interests of the several States, of which there were more than thirty, each jealous of the slightest supremacy of the others. When Prussia proposed, therefore, that the three duchies should be governed by their liberators rather than be added to the German States, of which there were already too many, the plan was bitterly opposed by the majority of the Confederation. But Prussia was determined not to yield, and with the coöperation of Austria succeeded in carrying her point. By the treaty of Gastein it was agreed that Austria should assume the provisional administration of Holstein, and Prussia that of Schleswig, while Lauenburg was made over to the Prussian government for the sum of seven and a half million marks.

It would seem that the army’s splendid achievements might have inclined the Diet to withdraw its long-standing opposition to the plans and wishes of the government, but such was not the case. Not only did the majority of representatives refuse as before to grant any appropriation for increasing the army, but also failed to make provision for the cost of the recent victorious campaign, expecting in this way to force the government to yield. Nothing was farther, however, from the intentions of King William and his trusty councillor, Bismarck. Firmly convinced that they were in the right, it would have seemed treachery to the Fatherland to abandon their purpose. Recognition of their efforts must come some time, and as it proved, that day was not far distant.

At Gastein, as has already been stated, the Schleswig-Holstein affair had been brought to a settlement, but it was only a preliminary one. Fresh disputes soon broke out between the two powers. Austria, already regretting her compliance, inclined more and more to the side of the enemies of Prussia, who wished to restore the independence of Schleswig and Holstein and make them part of the Confederation. The old jealousy broke forth anew, and, unable to reconcile herself to any real increase of Prussian power, Austria attempted to force King William to yield to the wishes of the Confederation. Laying before the Diet the danger of permitting Prussia to have its way, she succeeded in having a motion carried to oppose that power. Convinced that war was again inevitable, King William declared all former negotiations off, and urged Saxony, Hanover, and electoral Hesse to form an alliance preserving their neutrality. But here, too, meeting with a repulse, he was forced to put his whole army in the field and enter the struggle alone. His real feelings on the subject are evident from his parting words to Prince Frederick Charles after war had been declared and the march of troops into the enemy’s country had begun:

“I am an old man to be making war again, and well know that I must answer for it to God and to my conscience. Yet I can truthfully declare that I have done all in my power to avert it. I have made every concession to the Emperor that is consistent with the honor of Prussia, but Austria is bent on our humiliation and nothing short of war will satisfy her.”

Thus with a firm faith in God’s help and the righteousness of his cause the aged monarch placed himself at the head of his army, resolved to perish with it rather than yield in this vital question. Nor did he trust in vain. By forced marches Generals Vogel von Falkenstein and von Manteuffel invaded northern Germany, took possession of Hanover, and forced King George, after a gallant resistance at Langensalza, to capitulate, abdicate his throne, and abandon the country permanently. The main army, divided into three parts, commanded respectively by the Crown Prince, Prince Frederick Charles, and General Herwarth von Bittenfeld, speedily overran the enemy’s country, and before the King had left for the seat of war he was informed by telegraph of the victories of Skalitz and Münchengrätz, of Nachod and Trautenau. The first decisive results had been accomplished by the Crown Prince, and on the morning of June 29 the King joyfully shouted to the people from the open window of the palace: “My son has won a victory—good news from all quarters! All is well—my brave army!” The next day he left Berlin, and on July 2 reached Gitschin in Bohemia, where he was welcomed with joy by Prince Frederick Charles and his victorious troops. On the following day occurred one of the most famous battles of history—that of Königgrätz.

The King had just lain down to rest the previous night on the plain iron camp cot that accompanied him everywhere, when Lieutenant General von Voigts-Rhetz reached Gitschin with the news that the Austrians were stationed between the Prussian army and the Elbe. King William at once summoned his great strategist, General von Moltke, and Adjutant Count von Finkenstein was hastily despatched to the Crown Prince with orders to bring up his army, which was then in the mountains of Silesia. The guns were already booming from the neighboring heights and the smoke of battle beginning to fill the valleys like a mist when the King mounted his favorite mare Sadowa at the little village of Kleinitz, early on the morning of July 3, and dashed into the thick of the fray. The fire was so sharp that his staff, large enough to have been easily taken for a regiment of cavalry, was forced to scatter, but finally reached a position on the Roscoberg, where Count Finkenstein soon appeared with word that the Crown Prince was already on the march. Hour after hour passed, however, and nothing was to be seen of him. The issue was critical, and King William’s anxiety grew more and more intense, until at last, about two o’clock in the afternoon, the guns of the Crown Prince were heard in the enemy’s rear and the day was won. The Austrians were soon in full flight and were pursued as far as the Elbe by the victorious foe.

Soon after the Crown Prince’s arrival the King left the Roscoberg and, followed by his staff, rode down into the battle-field, urging the men to fresh valor by his inspiring presence, and disregard of danger from the enemy’s fire. None of his escort dared remonstrate with him, until at length the faithful Bismarck summoned courage and, riding up beside the King, begged him not to place his life in such jeopardy. Kindly but earnestly he answered: “You have done right, my friend. But when these brave fellows are under fire, the King’s place is with them. How can I retire?”

The results of this splendid victory were decisive, but the chief glory rests with the Crown Prince, whose troops after a long and exhausting march arrived just in time to save the day. It was a touching moment when the father and son met upon the field of battle, and all eyes were wet as the King, embracing Prince Frederick with fatherly pride, pinned on his breast the Order of Merit. The crushing defeat of Königgrätz effectually broke the enemy’s resistance, and the Prussians had advanced almost within sight of Vienna when the announcement of a truce put an end to hostilities.

In southern Germany the army of the Main under General Vogel von Falkenstein had also ended the struggle by a series of successful engagements, and on August 23 a treaty of peace was signed at Prague, by which Austria agreed to withdraw from the German Confederation; and Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover, electoral Hesse, Nassau, and the free city of Frankfort-on-the-Main were permanently incorporated with Prussia. Thus were King William’s labors at last crowned with success. Alone and almost without a friend in Germany he had gone forth to battle against a powerful enemy, and victory had been his. Beyond the Alps, however, he had found a friend in need in King Victor Emmanuel of Italy, who had aided him by attacking Austria at the same time from the south, thus dividing her forces. Covered with laurels, the victorious troops returned, meeting with ovations everywhere, but especially in Berlin. The whole city was en fête to welcome them. Triumphal arches were erected. Countless wreaths, banners, and garlands of flowers decorated the streets. Strains of music, pealing of bells, thunder of cannon proclaimed the arrival of the army, as it entered the city gates, headed by the heroic monarch and greeted with tumultuous shouts by the populace. An altar had been erected in the Lustgarten, where a praise service was held, the troops and people joining in singing “Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott.” The eleventh of November was appointed as a day of general thanksgiving throughout the country, and trees were planted everywhere in commemoration of the joyful occasion.

The results of this war did even more than those of the preceding one with Denmark to prove the wisdom of the King’s position in regard to the army, besides the large increase of territory it brought to Prussia. By far the most important issue of the campaign, however, was the establishment of the North German Confederation and the conclusion of an offensive and defensive alliance between this and the South German States, by which both agreed to respect the inviolability of each other’s territory and bound themselves in time of war to place their whole military force at the other’s disposal, the chief command of the united armies to be intrusted in such case to King William of Prussia. Thus did our august hero advance slowly but surely toward the realization of his hopes and aims, and visions of a restoration of the glories of the ancient holy German Empire already thrilled the hearts of patriots with a promise of the final fulfilment of their long-cherished dreams, as the King in his magnificent speech before the Imperial Diet on February 24, 1867, painted in glowing terms the future of a united Fatherland. Even the Prussian House of Deputies were weary of the long contention, and in the face of the universal recognition and admiration awarded their sovereign’s achievements, it abandoned its opposition to the government, and the King’s courage and perseverance were at last rewarded.

The period immediately following the Austro-Prussian War was a comparatively peaceful one, but the gradual increase of national strength and power in Germany had long since aroused the jealousy of France, and there was little hope of bringing about the unification of the country until the opposition of this hereditary enemy had been ended by a final and decisive struggle. And for this France herself soon furnished a pretext, though without any just cause.

The throne which Napoleon Third had seized by force was weak and crumbling, and it was only with the greatest difficulty that he was able to keep up an appearance of the magnificence for which his court had been famous. Nor was it founded on patriotism and love of liberty, those firm supports of sovereignty; on the contrary, the present occupant of the throne of France had aroused much dislike and condemnation among his subjects, and not without cause. Public dissatisfaction throughout the country increased daily, and the Emperor, alarmed for the future, determined at length that the only resource left him was to occupy the attention of the people by a great war, and give them something else to think of. Should it prove successful, his sinking star would doubtless rise once more to dazzling heights, while if defeated, no worse fate could overtake him than that which now threatened. As to whom the war should involve in order to make the strongest appeal to the sentiments and prejudices of the French, there could be no doubt, for from the earliest times there has been no nation so hated by them as Germany. Ever since the battle of Königgrätz King William and his ministers had felt sure that France would not view Prussia’s increase of power without a protest, though they had been careful to avoid giving her any pretext for making trouble. But there is an English saying, “Where there is a will there is a way,” the truth of which was proved by the French.

After the revolution which had deposed Queen Isabella the Spaniards were looking about for a King, and of the many candidates who offered themselves their choice fell on Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern. This was cause enough for grievance on the part of France, and King William, as head of the house of Hohenzollern, was requested through the French ambassador Benedetti to forbid his kinsman’s acceptance of the Spanish crown. To this our hero replied by refusing to put any constraint on the Prince’s decision; but Leopold, finding that his acquiescence in the wishes of Spain was likely to cause serious complications between France and Prussia, voluntarily withdrew his candidacy, thus, it would seem, removing any cause for trouble between the two powers. France, however, whose chief desire was to humiliate Prussia, had no intention of allowing this opportunity to slip through her fingers. Benedetti was ordered to obtain from King William, who was then staying at Ems, a written declaration that he regretted the annoyance this matter had caused Napoleon and would never again permit Prince Leopold to be a candidate for the throne of Spain.

The King’s behavior on receipt of this insulting demand was worthy of so great a sovereign. Calmly turning his back on the obtrusive Benedetti, he refused to have anything more to say to him and referred him to the ministry in Berlin for further discussion of the subject. This was on the thirteenth of July, 1870, and a stone now marks the spot on the promenade at Ems where this brief conference took place.

War was declared on the following day in Paris, and King William responded by issuing an order for the immediate mobilization of the entire army. The news was hailed with joy throughout the country. Napoleon had already brought about the very thing he most wished to prevent—the unification of all the German-speaking peoples. The whole nation rose in indignation at the insult that had been offered to the aged King, and his return to Berlin was like a triumphal progress. Everywhere crowds assembled to greet him, eager to express their admiration of the dignified way in which he had met the insolence and presumption of France. His appearance in the capital was hailed with wildest enthusiasm by his loyal subjects, and, deeply moved by their devotion, the King turned to his companions, saying: “This is as it was in 1813!” What most gratified him, however, was the despatch that promptly arrived from South Germany, which, but a short time since in arms against Prussia, now that a common enemy threatened the Fatherland, hastened to enroll her whole forces under the banner of the commander-in-chief. Little did France know the people or the spirit of Germany when she counted on the support of the South German States, expecting them to hail her with joy as their deliverer from the yoke of Prussia! Events now crowded fast on one another, yet there was little commotion in the country. Thanks to King William’s splendid organization, even this sudden mobilization of the whole army proceeded quietly and steadily, as if it were no more than the execution of some long-prepared-for manœuvre,—a state of things that served to calm and encourage both army and people. The German forces were divided into three great armies: the first, commanded by General von Steinmetz, stationed along the Moselle; the second, under Prince Frederick Charles, at the Rhine Palatinate; while the third, consisting chiefly of the South German troops under the Crown Prince, occupied the upper Rhine country.

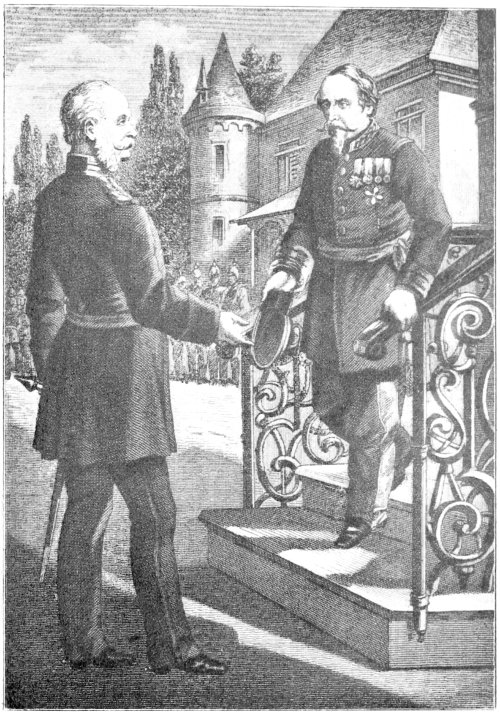

The Two Emperors

The King left Berlin July 31 to take command of the united forces. At half-past five in the afternoon the iron gates of the side entrance to the palace were flung open and the King and Queen drove out in an open carriage drawn by two horses. A roar of welcome greeted the vigorous old hero, who in military cloak and cap sat bowing acknowledgment to the rousing cheers of his enthusiastic subjects, while the Queen at his side seemed deeply affected. The royal carriage could scarcely make its way through the weeping and rejoicing throngs that swarmed about it all the way to the railway station, eager to bid farewell to their beloved sovereign and wish him a happy return. Banners floated from the roofs of houses and handkerchiefs fluttered from open windows,—a scene which was only typical of the feeling that pervaded the whole land. At the station the King’s companions were already awaiting him, his brother Prince Charles, General of Ordnance, and that great trio who had so ably assisted him in the previous war, Bismarck, von Moltke, and Minister of War van Roon, surrounded by a group of other generals. After the Queen had departed, King William entered the waiting train and moved off westward toward the seat of war, followed by the unanimous shout “With God!”

And truly God was “with King and Fatherland,” for in seemingly endless succession the telegraph brought news to the astonished people of one great victory after another. The French were wildly enthusiastic when with two entire army corps they finally forced a single Prussian battalion of infantry and three squadrons of uhlans to retreat after the latter had held out for fourteen days, and then with more than twenty guns bombarded the unprotected town of Saarbrücken; but it was to be their only occasion for rejoicing.

On the fourth of August Queen Augusta received the following message:

“A splendid but bloody victory won by Fritz at the storming of Weissenberg. God be praised for this first glorious achievement.”

The news quickly spread throughout the country, bringing joy and renewed confidence to all hearts. Two days later word came of a second victory for the Crown Prince. He had completely defeated the great Marshal MacMahon at Wörth, August 6, and King William in his despatch to his wife might with just pride send word to Berlin that “it should be in love with Victoria!”

A series of engagements followed, in the neighborhood of Metz, on the fourteenth, sixteenth, and eighteenth of August, which changed the general plans of the German army. The French Marshal Bazaine had attempted to invade the enemy’s territory from that place, but without success, while MacMahon, who had advanced from Châlons to the borders of the Palatinate and Baden, had suffered such losses at Weissenberg and Wörth that he was forced to fall back to his former position. It was therefore decided that the two French armies should unite in the neighborhood of Châlons and, thus strengthened, offer battle to the enemy. To prevent this, the Germans at once attacked Bazaine, cutting off his retreat to Châlons and occupying him until the arrival of some of their delayed corps. The manœuvre was successful, and after two days of hard fighting at Courcelles on the fourteenth, and Mars la Tour on the sixteenth, the struggle culminated two days later in the great battle of Gravelotte. It was for life or death; the desperate struggle of a brave army—the best, perhaps, that France ever sent into the field. But all in vain. Closer and closer about them drew the iron ring. German courage and tenacity permitted no escape.

At nine o’clock that evening King William sent his wife this despatch from the camp at Rezonville:

“The French army attacked to-day in strong position west of Metz. Completely defeated in nine hours’ battle, cut off from communication with Paris, and driven back towards Metz.

“William.”

In the letter that followed he says:

“It was half-past eight in the evening before the firing ceased.... Our troops accomplished wonders of bravery against an equally gallant enemy who disputed every step. I have not dared to ask what our losses are. I would have camped here, but after several hours found a room where I could rest. We brought no baggage from Pont-à-Mousson, so I have not had my clothes off for thirty hours. Thank God for our victory!”

Bazaine was now shut up in Metz and closely surrounded by the first, seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth corps, under the command of Prince Frederick Charles; MacMahon’s diminished army had retreated to Châlons, where it was met by the Garde Mobile. Except for this the road to Paris was open. It was therefore determined by the Germans to mass all their available forces and advance upon the capital without delay. It was fully expected at headquarters that MacMahon would dispute their way and that another battle must first be fought in the neighborhood of Châlons. Great was the surprise, therefore, when news was brought by scouts that the enemy had abandoned this important post and retired northward. This was inexplicable. Why not have gone to the westward in the direction of Paris? The commander-in-chief was not easily deceived, however, and as for Moltke, one must indeed rise betimes to get the better of him in strategy. MacMahon’s purpose soon became apparent. By a wide circuit from Châlons northeast to the Belgian frontier, and then southward again, he hoped to annihilate the besieging forces at Metz, release Bazaine, and thus reinforced to attack the rear of the army that was advancing on Paris,—a fine plan, but not fine enough to succeed against King William and his generals. A flank movement by the combined German forces to the right was ordered and a series of forced marches made to intercept MacMahon before he could reach Metz. It was a bold and exciting chase, led by the Crown Prince, Frederick William.

The French struggled desperately to gain their end, but all in vain; on the first of September they found themselves completely surrounded at Sedan, a fortress on the Belgian frontier, and forced to a decisive battle. King William himself was in command, and what a battle it was! Prussians, Bavarians, Würtembergers, Saxons vied with one another in deeds of daring and contempt of death against an enemy who, with the courage of despair, accomplished marvels of valor; yet when the day was ended MacMahon’s army had surrendered, and with it the author of all the trouble,—Napoleon himself.

Great were the rejoicings over this victory! King William and his gallant son were hailed on all sides with the wildest enthusiasm, their praises sounded far and wide. The Crown Prince and his cousin Prince Frederick Charles were rewarded for their services to the Fatherland by being made field marshals immediately after the fall of Metz, an event that had never before occurred in the history of the house of Hohenzollern.

The first telegram sent by the King to the Queen after this latest victory ran as follows:

“Before Sedan, September 2, 2.30 P.M.: The capitulation of the entire army in Sedan has just been arranged with General Wimpffen commanding in place of MacMahon, who was wounded. The Emperor only surrendered himself to me personally, since he is not in command, and has left everything to the Regency in Paris. I will decide on his place of residence after the interview which I am to have with him at once. What a fortunate turn of affairs has been vouchsafed by Providence!”

On the third of September this despatch was followed by a letter, from which we quote:

“Vendresse, September 3, 1870.

“By this time you have learned from my telegram the extent of the great historical event that has just happened. It is like a dream, even though one has seen it unroll itself hour by hour.”

Then follows a brief and concise description of the battle and its results:

“On the night of the thirty-first the army took up its prearranged positions about Sedan, and early in the morning firing began in spite of a dense fog. When I arrived at the front about eight o’clock, the large batteries had already opened fire on the fortifications, and a hot fight soon developed at all points, lasting almost the entire day, during which our side gained ground. A number of deep wooded defiles hindered the advance of the infantry and favored the defence, but village after village was captured and a circle of fire gradually closed in about Sedan. It was a magnificent sight from our position on a height behind one of the batteries.

“At last the enemy’s resistance began to weaken, as we could perceive from the broken battalions that were driven back from the woods and villages. Gradually their retreat was turned into a flight in many places, infantry, cavalry, and artillery all crowding together into the town and its environments; but as they gave no intimation of relieving their desperate situation by surrendering, there was nothing left for us but to bombard the town. After twenty minutes it was burning in several places, and with the flaming villages all about the field of battle the spectacle was a terrible one. I therefore had the firing slackened and sent Lieutenant von Bronsart of the general staff with a flag of truce to demand the surrender of the army and citadel. On inquiring for the commander-in-chief, he was unexpectedly taken before the Emperor, who had a letter he wished delivered to me. The Emperor asked his errand, and on learning it replied that he should have to refer him to General von Wimpffen, who had assumed command after MacMahon was wounded, and that he would send his Adjutant General Reille with the letter to me. It was seven o’clock when the two officers arrived; Bronsart was a little in advance, and from him we first learned with certainty that the Emperor was in Sedan. You can imagine the sensation this news caused! Reille then sprang from his horse and delivered to me his Emperor’s letter, adding that he had no other commission. It began as follows: ‘Not having been able to die at the head of my troops, it only remains for me to place my sword in the hands of Your Majesty.’ All other details were left to me.

“My answer was that I regretted the manner of our meeting and requested him to appoint a commission to arrange for a capitulation. After I had handed my letter to General Reille, I spoke a few words with him as an old acquaintance, and he took his departure. On my side I named Moltke with Bismarck to fall back upon in case any political questions should arise, then rode to my carriage and came here, greeted everywhere with thundering shouts by the marching troops that filled the streets, cheering and singing folk-songs. It was most thrilling! Many carried lighted candles, so that at times it was like being escorted by an improvised torchlight procession. I arrived here about eleven o’clock and drank with my staff to the army which had achieved such glorious results. The next morning, as I had heard nothing from Moltke of the negotiations which were to take place at Donchery, I drove as agreed to the battle-field about eight o’clock and met Moltke, who was coming to obtain my consent to the proposed surrender. He told me that the Emperor had left Sedan as early as five o’clock and had come to Donchery. As he wished to speak to me and there was a small château in the neighborhood, I chose this for our meeting.

“At ten o’clock I arrived on the heights before Sedan; at twelve Moltke and Bismarck appeared with the signed articles of capitulation, and at one I started, without Fritz, escorted by the cavalry staff. I alighted before the château, where the Emperor met me. The interview lasted a quarter of an hour; we were both much moved at meeting again under such circumstances. What my feelings were, after having seen Napoleon only three years before at the summit of his power, I cannot describe. [King William had been in Paris in 1867 on the occasion of the World’s Exposition there.]

“After this interview I reviewed all the troops before Sedan; their welcome to me, the sight of their ranks so terribly thinned—all of this I cannot write of to-day. I was deeply touched by so many proofs of loyalty and devotion, and it is with a full heart that I close this long letter. Farewell.”