| Dedication | Page xiii |

| Preface | xv |

| Introduction, by Professor A. H. Keane, ll.d., f.r.g.s. | xxxi |

| Arrival at Great Zimbabwe—First Impressions—View from Acropolis Hill | 1 |

| Mystic Zimbabwe—Sunday Morning and Midnight in an Ancient Temple—Sunset on the Acropolis | 12 |

| A day at Havilah Camp, Zimbabwe | 31 |

| Zimbabwe District—Chipo-popo Falls—Frond Glen—Lumbo Rocks—“Morgenster” Mission—Wuwulu—Mojejèje, or Mystic Bar—Suku Dingle—Bingura’s Kraal—Motumi’s Kraal—Chipfuko Hill—Chipadzi’s Kraal | 51 |

| Zimbabwe Natives—Natives and the Ruins—Natives (general) | 80 |

| Relics and Finds, Great Zimbabwe, 1902–4 | 102 |

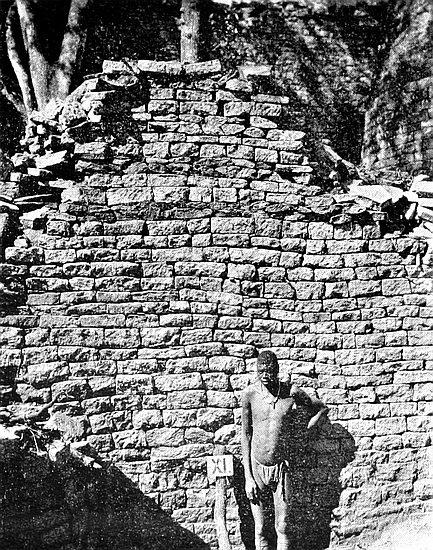

| Notes on Ancient Architecture at Zimbabwe—Introduction—Durability of Walls—Dilapidations—Makalanga Walls—Remains of Native Huts found in Ruins—Passages—Entrances and Buttresses | 135 |

vi

CHAPTER VIII |

|

| Notes on Ancient Architecture at Zimbabwe (continued)—Drains—Battering of Walls—Soapstone Monoliths and Beams—Granite and Slate Beams—Cement—Dadoes—Built-up crevices—Holes in Walls other than Drains—Blind Steps—Platforms—Ancient Walls at a Distance from Main Walls—Caves and Rock Holes | 168 |

| The Elliptical Temple—Plan—Construction, Measurements—Summit and Foundations of Main Wall—Chevron Pattern—Ground Surface of Exterior | 193 |

| The Elliptical Temple (continued)—Main Entrances | 216 |

| The Elliptical Temple (continued)—Enclosures Nos. 1 to 7 | 225 |

| The Elliptical Temple (continued)—Sacred Enclosure—Conical Tower—Small Tower—Parallel passage | 237 |

| The Elliptical Temple (continued)—The Platform—Enclosures Nos. 9 to 15—Central Area—Platform Area—Inner Parallel Passage—South Passage—West Passage—North-East Passage—Outer Parallel Passage | 251 |

| Acropolis Ruins—South-East Ancient Ascent—Lower Parapet—Rock Passage—Upper Parapet—Western Enclosure | 276 |

| Acropolis Ruins (continued)—The Western Temple | 297 |

| Acropolis Ruins (continued)—Platform Enclosure—Cleft Rock Enclosure—The Platform—Balcony Wall—Little Enclosure—Winding Stairs—Upper Passage—East Passage—Buttress Passage—South Enclosures A, B, and C—South Cave—South Passage—Central Passage | 310 |

| vii Acropolis Ruins (continued)—Eastern Temple—Ancient Balcony—Balcony Enclosure—Balcony Cave—“Gold Furnace” Enclosure—Pattern Passage—Recess Enclosure—North Plateau—North Parapet | 323 |

| Acropolis Ruins (continued)—North-West Ancient Ascent—Watergate Ruins—Terraced Enclosures on North-West Face of Zimbabwe Hill—South Terrace—Ruins on South Face of Zimbabwe Hill—Outspan Ruins | 344 |

| “The Valley of Ruins”—Posselt, Philips, Maund, Renders, Mauch Ruins, and South-East Ruins | 363 |

| “The Valley of Ruins” (continued)—No. 1 Ruins—Ridge Ruins—Camp Ruins Nos. 1 and 2 | 398 |

| Ruins near Zimbabwe—East Ruins—Other Ruins within the Zimbabwe Ruins’ Area | 420 |

| Notes and Addenda | 433 |

| Index | 451 |

viii

ix

xiv

IN preparing this detailed description of the ruins of Great Zimbabwe—the first given to the world in modern times—the author has aimed at permitting the actual ruins themselves to relate their own story of their forgotten past unweighted by any consideration of the many traditions, romances, and theories which—especially during the last decade—have been woven concerning these monuments.

The only apology offered for this apparently lengthy Preface is the mention of the fact that the operations at Great Zimbabwe were carried on for six months after the text of this volume had been sent to the publishers in England. The Preface, therefore, thus affords an opportunity of bringing down the results of these operations to a recent date.

The recent examination of the district surrounding the ruins now shows the Ruins’ Area to be far larger than either Mr. Theodore Bent (1891) or Sir John Willoughby (1892) supposed. Instead of the area being confined to 945 yds. by 840 yds., it is now known to be at least 2 miles by 1¼ miles, and even this larger limit is by no means final, as traces of walls and of walls buried several feet under the veld have been discovered, not only in Zimbabwe Valley, but in the secluded valleys and gorges and on the hillsides which lie a mile and even two miles beyond the extended xviarea. Huge mounds, many hundred feet in circumference, with no traces of ruins, covered with large full-grown trees and with the remains on the surface of very old native huts, on being examined have been found to contain well-built ruins in which were unearthed small conical towers, gold ornaments, a few phalli, and in one instance a carved soapstone bird on a soapstone beam 4 ft. 8 in. high, which is more perfect and more ornate than any other soapstone bird on beam yet found at Zimbabwe. The examination of such spots and of all traces of walls which lie at the outer edge of the extended Ruins’ Area would, even with a large gang of labourers, occupy almost a lifetime.

Mr. Bent spoke of Zimbabwe as a “city,” and recent discoveries show the employment of this title to be fully justified, for not only is the Ruins’ Area vastly extended, but the formerly conjectured area can now be shown by recent excavations to have been much more crowded with buildings than could possibly have been seen in 1891. For instance, 2,300 ft. of passages have recently been discovered within the heart of the old Ruins’ Area buried some feet under the silted soil below the veld in spots where the siltation is rapid, the existence of which structures had been altogether unsuspected. In some instances the native paths, used by visitors inspecting the ruins, crossed these passages from 3 ft. to 5 ft. above the tops of the passage walls. The enormous quantity of débris, evidencing occupations in several periods, scattered over both the old and the extended area, is simply astonishing, and judging by the value of “finds” made during the recent work, it seems quite possible that further exploration would, in the intrinsic value of relics as relics, largely reimburse the expense of its continuance, while securing the opening up of fresh features of architecture and probably some definite clues as to the original builders of the numerous periods of occupation respectively; would bring an immense addition to scientific knowledge, while the more importantxvii ruins themselves, having been cleared of silted and imported soils and wall débris, are now ripe for the further examination for relics.

The secluded valleys, and also the caves in hills, for a distance of six miles, and in some cases as far as ten miles, from Zimbabwe have been systematically searched in the hope of discovering the burial place of the old gold-seekers. The neighbourhood of Zimbabwe contains several extensive ranges of granite hills each enclosing many secluded and Sinbad-like valleys and gorges, where natives state white men had never previously entered. Such spots on the whole of the Beroma Hills to the east of Zimbabwe, the south end of the Livouri Range to the west, the Bentberg Range to the south, and several hills in the Nini district, as well as several parts in the Motelekwe Valley, have been systematically searched without avail, though there are in certain of these secluded places traces of walls and artificially placed upright stones and other signs of human presence which require some explanation. The siltation of soil from the steep hillsides of many of these most romantically situated valleys has been very extensive. These searches could only be carried on after veld fires had swept the district of the rank grass which here grows to a height of 12 ft. Mr. Bent and other writers have shown that the old Arabians religiously preserved their dead, burying them in secluded spots at some considerable distance from any place of occupation. The writer is not without hope that these burial-places may yet be found. The population of Zimbabwe at several different periods must have been immense, and, judging by the remains found near some of the oldest types of ruins in other parts of the country where the amount of gold ornaments buried with each corpse ranged from 1 oz. to 72 oz., the discovery of such places in the Zimbabwe district would yield importantxviii results, especially as, for many reasons, Zimbabwe undoubtedly appears to have been the ancient metropolitan capital and the centre of gold-manufacturing industry of the original and later Arab gold miners, and the place so far has yielded the richest discoveries of gold in every form.

The writer is now perfectly assured that no burial-places of the original builders will be found under the interior of the Elliptical Temple or within 30 yds. of the exterior. Holes have been sunk at regular intervals within the temple and immediately outside the walls, and boring-rods have been systematically employed, and the position and lie of the formation rock ascertained throughout, so that sections and levels have been made of the soil and rock under the temple. All the results gained from each hole and boring are recorded. But beyond discovering buried foundations at the higher level, only virgin soil, never before disturbed, was gone through. French and German archæologists who visited Zimbabwe during the operations confirmed what British scientists have affirmed, that no burials of people of Semitic stock would be found within or near to any building so frequently in use as the great temple must have been. The severe restrictions with regard to cleanliness and sanitation, especially as to the dead, are among the most notable features of the old Semitic nations.

No ancient writing has been discovered, though close attention has been paid to all stones and pottery likely to bear it, and notwithstanding that the interiors of some of the more ancient portions of the ruins have been cleared down to the old floors where, if any existed, they might reasonably have been expected to be found. Post-Koranic lettering was found on highly glazed pottery, also on glass, but all such specimens are of a fragmentary character; but experts such as Mr. Wallace Budge, the Head Keeper of Egyptianxix and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum, state that the glass and other “finds” of pottery are not older than the thirteenth or fourteenth century of this era. Other pottery thickly covered with dull-coloured glazes—mainly purples, greens, and browns—is thought to be somewhat older than that on which the lettering was found. Still, as such a very large portion of what may be considered as the more ancient of the ruins remains to be examined, it may yet be possible to unearth older specimens of Arab writing.

Gold in a manufactured form is found on the lowest and original floors of the most ancient portions of the Zimbabwe ruins. In several ruins this was found as thickly strewn about the cement floors as nails in a carpenter’s shop. Gold ornaments discovered at this depth, in some instances from 3 ft. to 5 ft. below any known native floors, were always found in association with the oldest form of relics yet unearthed at Zimbabwe. Such gold articles are of most delicate make, and are doubtless of an antique character, and expert opinion recently obtained in England confirms this conclusion.

But there are other gold articles which are ruder in design and make, and these by no means are entitled to claim such antiquity. In fact, expert opinion declines to recognise them as being in any sense ancient; for instance, beaten gold of irregular shape showing the rough hammer marks of some very crude instrument, and with holes round the edges of such plates very rudely cut—or rather torn—and placed in imperfect rows altogether in a haphazard style. This form of gold plates is identical in every detail with the copper sheathing with which it is always found associated. The same remarks apply equally to the gold beads also found with this class of plates which betoken crude workmanship, as well as to the iron instruments decorated with small gold knobs.

xx

With regard to the location of the later-period gold articles there is ample evidence that these are of very old native origin. Such ornaments are commonly met with on the floors of, or in close proximity to, the old native huts of the types of Nos. 2 and 3 (see Architecture, s.s. Native Huts found in Ruins, pp. 154, 155, post), and also in the cement huts with small radiating walls on levels several feet above any ancient floorings. In every instance such gold ornaments are found in association with articles of old native make—such as double iron gongs, copper sheathing, and copper assegai- and arrow-heads.

In 1902 the floor of the North Entrance to the temple was exposed to a depth of 5 ft. below the surface, as shown in Mr. Bent’s book (p. 106), while a flight of steps in perfect condition leading up to the entrance from the exterior was discovered at a depth of 9 ft. below the old surface. This entrance, showing a bold conception and admirable construction, is now considered as one of the principal show features at Zimbabwe. Further, it is the oldest form of entrance and steps as well as the finest of any yet discovered in Rhodesia. A quantity of gold was found on the floor and steps of this entrance, which were once covered with fine granite cement, also a few true phalli.

This has been cleared throughout to a depth of at least 3 ft., and in one place 7 ft. Cement floors were exposed, and these were found to be divided into small catchment areas with a drain from each passing outwards through the main wall. Five additional drains were discovered in thisxxi passage. Here were found eight ornate phalli, a portion of a gold bangle, some beaten gold and gold tacks of microscopic size, and fragments of carved soapstone beams.

This was cleared out to a depth of 4 ft. throughout its whole area, and a few phalli of unmistakable form were found, and old granite cement floors and steps were uncovered. Explorers and relic hunters had worked in this enclosure, and had double trenched it from end to end.

A remarkable discovery was made here of distinct traces of granite cement dadoes, 7 ft. high, round the interior faces of the walls of this enclosure. In some other enclosures the remains of dadoes can still be seen.

The small conical tower in this enclosure has during the last ten years been seriously damaged by the large trunk of a tree pushing over the summit of the cone. Photographs of this small tower taken in 1891 show that it was then almost intact.

This open area, lying to the west and north of the Conical Tower and the Platform, corresponds to the open areas immediately in front of the altars in old Grecian temples. This was Mr. Bent’s opinion, and possibly it answered at Zimbabwe a similar purpose of accommodating the worshippers. The area, some 120 ft. by 60 ft., has been cleared out of large trees, and of about 6 ft. of soil throughout, and floors—both cement and clay—were disclosed, also a fine circular structure of excellent granite cement, and ascended by two steps. On and close to this structure were found fragments, mainly bases, of carved soapstone beams of slender appearance, also some phalli and gold. This platform lies slightly off the north line between the Conical Tower and the Main North Entrance.

xxii

Some of the walls surrounding this area on the west and north sides, once considered to be ancient, can now be seen to cross over very old native clay huts and native copper and iron-smelting furnaces. The soil contained some phalli, which had been converted by the natives into amulets, also some Arabian glass—thirteenth and fourteenth centuries—Venetian beads, gold wire-work, beaten gold, gold scorifiers of native pottery, iron pincers, and fragments of carved soapstone bowls with geometric designs.

Gold-smelting operations must have, at some late period, been extensively carried on in these enclosures, for on removing from each enclosure all débris and fallen stones to a depth of from 4 ft. to 7 ft., there were found burnishing stones of fine grain and still covered with gold, gold scorifiers with gold in the flux, cakes of gold, gold furnace slag, beaten gold, and gold dust.

At a still lower depth in No. 6 Enclosure a quantity of granite clay crucibles, showing gold richly, were met with, and these are undoubtedly of older type than the native pottery scorifiers, also some ingot moulds of soapstone of the double claw-hammer or St. Andrew’s cross pattern.

This area is only partially excavated, it being covered with old native-built walls which cross over bone and ash débris, old native huts, an iron furnace, and rich black mould in which the vegetable matter was still undecayed. Experimental holes and boring-rods showed that some very old foundations ran below the soil upon which the later and poorer walls are built. However, a key has now been found which will enable further excavations to be made within this area without injury to the upper walls.

xxiii

Along the summit of the east main wall, and only over the chevron pattern which faces east, have recently been discovered the traces of foundations of small circular towers, both on the inner and outer edges of the wall. These correspond in measurement and relative position to the small conical towers on the west wall of the Western Temple at the Acropolis Ruins, which is decorated with monoliths. Some of the best-known surveyors and practical builders in Rhodesia are prepared to certify as to the traces of these foundations. This is entirely a new discovery, as is also the fact that at one time the summit of the wall, only over the chevron pattern, bore beautifully rounded soapstone monoliths, the bases being found displaced under the ruck of loose blocks which runs along the centre of the summit of this part of the main wall. Some carved splinters of these monoliths were found at the bases of the wall. A collection of these “finds” has been sent to the Salisbury Museum.

All the walls of the Elliptical Temple are not ancient; that is, not ancient in the sense applying to the suggested Sabæo-Arabian occupation of Rhodesia and also to that of the Solomonic gold period. The evidences pointing to this conclusion, and now for the first time available, are so obvious and general, and the ocular demonstration so positive, that one of the many popular myths concerning Great Zimbabwe must, even at the risk of committing a vandalism on cherished romantic theories and beliefs, go by the board. The writer prefers that the ruins should tell their own story, and this can now be read in the walls, in the débris heaps, and in the relics and their associated “finds” and locations.

The oldest walls of the temple for which great antiquityxxiv may be claimed are—the main east wall from north to south, the Conical Tower, the Platform, portions of the inner wall of the Parallel Passage (reconstructions are present here), and some adjoining walls, and some buried walls and foundations, and possibly some other walls on the south side, concerning which some doubt exists, as also the west wall of the West Passage, a well-built structure which once was extended at either extremity. As to the question of obviously much later walls, this is involved in the following section of this preface.

The writer is fully convinced that the original west wall of the temple once extended outwards further west, and that the present west wall extending towards the south is of much more recent construction and is built on a shorter curve, also that most of the structures of the central and western portions of the building are also of much later construction, and this for many substantial reasons, some of which are here briefly stated:—

(a) The west wall is considered by all practical builders and architects to be far slighter, much inferior in construction, fuller of defects, and to contain to a greater extent ill-shaped stones than the main wall on the east side, while the foundations are at many points far more irregular, and the batter-back of the interior face of the west wall is less severe than is the case of the east side. Lengths of 25 ft. each of both walls have been examined and compared and photographed, and the number of defects of construction recorded. The number of false and “straight joints,” false and disappearing courses, and stones supported at their corners by granite chips, which the west wall contains, is roughly about forty odd to every one of such defects in the east wall, which is the architectural marvel for symmetry, grand proportion, true courses of most carefully selected and assorted blocks (somexxv of which have been dressed with metal tools) of any other ancient architectural features at Zimbabwe. All this is an ocular demonstration, and is commented upon by the most casual visitor to these ruins. This, too, is very patent when seen from the summit of Zimbabwe Hill, the view looking down upon the temple revealing most obviously the different characters of the walls.

(b) In 1903 the writer cleared the soil away from the gap between the older and later walls, and found that they were widely different in construction; that the later and narrower wall approached the older and well-built and wider wall at an oblique angle; and that the end of the older wall is broken and not finished off as are other ends of ancient walls. In a trench made at a distance of twelve yards west of the gap, and on the curve the older wall, if continued, would have passed, a mass of buried masonry, which might have been a portion of the old wall, was disclosed.

(c) Dr. Hahn, the leading expert in South Africa in chemical metallurgy, analysed the soil underlying the foundation of the west wall, and pronounced it to be composed of disintegrated furnace slag and ashes containing gold and iron. The ground to the west of the west wall has always been the spot at which gold prospectors have washed the soil for gold, and here gold crucibles and scorifiers are to be found. This soil contains 73 per cent. of silica, and would make an excellent foundation for walls, and the west wall is built right along this bed of furnace slag, which is about 2 ft. in depth, many yards wide, and extends from north to south.

(d) At a few feet from the exterior of the west wall, and at a depth of four feet below the level of its foundation, and extending as shown in trenches and cross-cuts for at least thirty yards from north to south, is a floor of granite cement laid on the formation rock, hiding its irregularities and making a perfectly level surface. The full extent of thisxxvi flooring has not yet been ascertained. For two feet between the level of this cement flooring and the furnace-slag soil under the foundations of the west wall is fine silted soil. Evidently the later wall was erected at a very considerable period subsequently to the laying of the cement flooring and after the siltation of the soil, and also after the gold-smelting operations had been extensively carried on for a long period.

(e) No single relic of any great antiquity has been found by any explorer or prospector in the western portion of the temple, while the eastern portion has yielded at depth great quantities of phalli and of every relic believed to be associated with the earliest occupiers.

The oldest “find” in the western half of the building is pronounced by Dr. Budge to be of a period dating from between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries of this era, and other “finds” relate to the same and later periods.

The writer is now and for the above and further considerations, and after two years’ residence within the ruins, perfectly convinced of the following:—

(1) That on the departure of the ancient builders and occupiers the temple became a ruin, and remained as such for some centuries, the west wall disappearing in the meantime (as explained later); (2) that some organised Arab people, possibly a split of the numerous Arab colonies and kingdoms which existed down the East African coast, possibly of the Magdoshu kingdom, who, according to De Barros, reached Sofala (1100 a.d.), exploited the gold mines, and formed a mixed population between the Arabs and natives, or possibly the Arabs of Quiloa, who secured as suzerain power Sofala and the kingdom of the Monomotapa (Rhodesia). One of these peoples is believed to be responsible for the ruins of Inyanga, which the writer after examining these remains does not consider to be ancient inxxvii the fullest sense of the term. One of these peoples are also believed to be responsible for making the “old workings,” the distinction between which and the “ancient workings” must always be kept in mind, a distinction which the late Mr. Telford Edwards always pointed out and insisted upon, and concerning which recent investigations prove him to have been correct; (3) that these Arabs made Zimbabwe their headquarters, to which the washed gold dust was brought to be converted into ingots for transport; (4) that these Arabs carried on extensive gold-smelting operations at the west end of the temple in the shelter of the massive walls, which would protect them against the prevailing winds and drifting rains; (5) that after carrying on these gold-smelting operations extensively and for a considerable period, they built a wall across the open space and upon their furnace-slag beds, possibly employing native labour (the Makalanga being notorious for their skill in wall building); and (6) that these Arabs also built several of the enclosures in the central and western parts of the temple to suit their special convenience, and altogether regardless of the buried foundations of the ancient builders.

It may be asked what caused the destruction of the original west wall. Its disappearance may be accounted for as follows. The south and west walls have for centuries borne the full brunt of all the torrential rain and storm water which rushes to these points from the Bentberg Kopjes, which lie close to the temple on the south side. This accounts for the great depth of silted soil which buries the old cement flooring. This must have washed the lower portions of the walls till the cement foundations decomposed and brought down the structure as it has done at other ruins at Zimbabwe. The writer at the commencement of his first rainy seasonxxviii at Zimbabwe found a large pool about 30 yds. in length, 15 yds. in breadth, and 2 ft. in depth up against the present west wall, towards which all surface water from the higher ground rushed unchanged. This had been going on every rainy season for many generations, with the result of forming large cavities under the foundations, and of keeping the wall in a constant drip with damp even at noontide, and of causing the spread of large moss over the walls, while shrubs and small trees grew out of the walls at some height from their base. Trenches and runs-off and banks soon cured this evil, and now the walls have changed from being black with damp to being grey with dryness. The moss has naturally flaked off, and the trees and shrubs in the walls are dead, owing to lack of moisture.

Operations in this temple since the description of the earlier work was embodied in the text of this volume have been carried on to June, 1904. Soil to a depth of from 3 ft. to 5 ft. was removed from the whole of the eastern portion of this area. The excavations showed several layers of native clay floors one above another. The “finds” were those known to be of native origin, though not made by natives of to-day. The later or native period of gold manufacture was greatly in evidence, beaten gold, gold tacks, and gold wire being frequently met with in association with copper sheathing, copper assegai- and arrow-heads, the copper containing no alloy.

A trial hole sunk to a depth of 6 ft. below this cleared portion of the temple area, or 9 ft. below the surface as it appeared in 1903, showed in its sides the lines of several clay floors and the side of a Kafir clay hut, now quite dexxixcomposed and soft. At the bottom of the pit a rough pavement of closely-fitting stones of irregular shape and size was come upon, and the articles found were identical with those discovered at a higher level.

The clearing of the area also disclosed clay sides of huts with the remains of short walls of stone radiating from the sides of the huts. The wall which Mr. Bent considered might have been the “altar” was found to be the radiating wall of a similar hut built upon a higher level. These small radiating walls are a general feature of exceedingly old native huts found at several places at Zimbabwe.

A large circular platform of granite cement was also disclosed. This spot yielded beaten gold of native make.

The writer believes that between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, or slightly earlier, a great influx of people took place at Zimbabwe, and that the majority of the minor ruins in the Valley of Ruins were built about this period. This is shown by the number of walls built across exceedingly old débris heaps of native origin, by the “finds” of Arabian articles on their lowest floors, and by the fact that no relic of greater age than that period has been found. Two or three of the better-built minor ruins have the appearance of greater age, and some of the relics found in this class of ruins are of the oldest type. No one who had not spent considerable time at Zimbabwe could have any possible conception of the immense population present here at a period of but a few centuries ago. The remains of their stone walls are scattered thickly over the valleys and hillsides of Zimbabwe. The Makalanga state these are all Makalanga of generations long passed away. Some are constructions by indigenous peoples, and certainly they are not ancient, though largely built of stones quarried from the ancient ruins, and the “finds” are those of old native type, including Arab articles.

xxx

The thanks of all scientific circles, and of South Africans generally, are due to Sir W. H. Milton, Administrator of Rhodesia, whose great interest in the preservation of the ancient monuments in these territories is well known, and to whose direction is due the recent and timely preservation work at Great Zimbabwe. The author desires to express his personal indebtedness to Sir William Milton for the adequate arrangements made by him while engaged in his recent researches at the Great Zimbabwe.

The clearing of the Elliptical Temple and its vicinity has enabled Mr. Franklin White, m.e., Bulawayo, to prepare the latest and so far the most perfect plan of that building, and this he has kindly placed at the service of the author.

Indebtedness is also expressed to Professor A. H. Keane, ll.d. (author of The Gold of Ophir), for the contribution of the Introduction to this volume; to Mrs. Theodore Bent for generously permitting the use in this volume of illustrations from The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland; to Mr. Gray, Chief Veterinary Surgeon, Salisbury, Mr. H. S. Meilandt, Government Roads Inspector, Bulawayo, and Trooper Wenham, b.s.a.p., Victoria, for permission to reproduce certain photographs of the ruins, and also to the Directors of the British South Africa Company for permission to include the map of Rhodesia in this work.

AN archæological work of absorbing interest, such as the volume here presented to the reader, needs no introduction. Nor are the following remarks meant to be taken in that sense, but only as a sort of “missing link” in the chain of evidence between past and present, between the Arabian Himyarites and the Rhodesian monuments, the forging of which the author has entrusted to me. In The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia, of which Great Zimbabwe is the inevitable outcome, Messrs. Hall and Neal did not discuss the problem of origins, speculation was distinctly eschewed, and although their personal views were, and are, in harmony with those of all competent observers, they made no dogmatic statement on the subject, leaving the main conclusion to be inferred from the great body of evidence which they patiently accumulated on the spot and embodied in their monumental work. In Great Zimbabwe, of which Mr. Hall is sole author, and the rich materials for which he has alone brought together, the same attitude of reserve is still maintained, perhaps even more severely, and therefore it is that he has now invited me to develop the argument by which, as he hopes and I believe, the wonderful prehistoric remains strewn over Southern Rhodesia, but centred chiefly in the Great Zimbabwe group, may be finally traced to their true source in South Arabia, Phœnicia, and Palestine.

In The Gold of Ophir, whence Brought and by Whom,[2] xxxiiwhere several chapters are devoted to this subject, I inferred, on plausible grounds, that the Havilah of Scripture—“the whole land of Havilah where there is gold”—was the mineralised region between the Zambesi and the Limpopo, and that the ancient gold-workings of this region were first opened and the associated monuments erected by the South Arabian Himyarites, followed in the time of Solomon by the Jews and Phœnicians. I further endeavoured to show that all these Semitic treasure-seekers reached Havilah (the port of which was Tharshish, probably the present Sofala) through Madagascar, where they had settlements and maintained protracted commercial and social intercourse with the Malagasy natives; and lastly, that the produce of the mines was by them sent down to the coast and shipped at Tharshish for Ophir, the great Himyaritic emporium on the south coast of Arabia, whence it was distributed over the eastern world. It followed that the scriptural “gold of Ophir” did not mean the gold mined at Ophir, which was not, as hitherto supposed, an auriferous land, but a gold mart.[3] The expression meant the gold imported by the Jews and Phœnicians from Havilah (Rhodesia), viâ Tharshish, Ophir, and Ezion-geber in Idumæa, at the head of the Red Sea.

It is needless here to recapitulate in detail the arguments that I have advanced in support of this general thesis. But I should like to point out that if one or two of them have been invalidated by my critics, several have been greatly strengthened by the fresh evidence that has accumulated since the appearance of The Gold of Ophir.

Of course, incomparably the most important mass of fresh evidence is that which has been brought together by Mr. Hall himself during his two years’ researches amid the central xxxiiigroup of ruins, and is now permanently embodied in Great Zimbabwe. Yet the work has in a sense been but begun; it has reached down only to the ancient flooring which has still to be explored; and we are assured by Sir John Willoughby, a most competent authority, that after two months’ exploring the wonderful Elliptical Temple with a large gang of labourers, two years will yet be needed to complete the surface work of that structure alone, without touching the old floors. Mr. Hall infers that three further years will be required for the Acropolis itself, besides the “Valley of Ruins,” with the groups of buildings extending in all directions for over a mile from the temple. A mere glance at some of the finely reproduced photographs creates a sense of awe and amazement at the huge size and solidity of the containing walls with their patiently interwoven chevron and other patterns, and at the vast extent of the ground covered by these great monuments of a forgotten past. Their erection must have taken many scores of years, one might say centuries, and their builders must consequently have dwelt for many generations in the land which they so diligently exploited for its underground treasures. Here and in all the other strictly mining districts they carried on their operations in the midst of hostile native populations, as is sufficiently evident from the strongholds crowning so many strategical heights, from the formidable ramparts and the immense strength of the outer walls, everywhere rounding off in long narrow passages leading to the inner enclosures.

Under such conditions it will naturally be asked, whence did the foreign intruders obtain their food supplies? The answer to this question is suggested in The Ancient Ruins, where it is pointed out (p. 208) that the auriferous reefs of the central Zimbabwe district, and generally of all the districts in immediate proximity to the fortified stations, show no traces of having ever been worked for the precious metal. “Possibly the reason for the ancients ignoring the gold-reefsxxxiv of this district [Zimbabwe] lies in the fact that the country round about is exceedingly well suited for agricultural purposes, the soil being rich and water plentiful, and all vegetable growths prolific and profuse. The large population of ancients, together with the enormous gangs of slaves, would naturally consume a vast quantity of grain, and this necessity would create a large agricultural class, who, for their own safety and for the protection of their crops and fruits, would naturally carry on their operations within such an area as could be safeguarded by the fortresses of Zimbabwe.”

It might at first sight be supposed that the food supplies were drawn chiefly from the extensive agricultural settlements of the Inyanga territory, on the northern slopes of Mashonaland, which drain through the Ruenga and its numerous affluents to the right bank of the Zambesi. This Inyanga district may be roughly described, from the archæological point of view, as an area of old aqueducts, of old terraced slopes, and of old ruins of a less imposing type than the Zimbabwe remains. In a notice of The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia contributed to the Geographical Journal for April, 1902, I first drew attention to the surprising analogy, or rather identity, between these terraces and those of the South Arabian uplands visited by General E. T. Haig in the eighties. So close is the parallelism that Haig’s description might almost change places with Mr. Telford Edwards’ account of the Inyanga works quoted in The Ancient Ruins, p. 353 sq., as thus:—

TERRACED SLOPES (SOUTH ARABIA) |

TERRACED SLOPES (SOUTH AFRICA) |

|---|---|

|

“In one district the whole mountain side, for a height of 6,000 ft., was terraced from top to bottom. Everywhere, above, below, and all around, endless flights of terraced walls meet the eye. One can hardly realise the enormous amount of labour, toil, and perseverance which these represent. The terraced walls are usually from 4 to 5 ft. in height, but towards the top of the mountain they are sometimes as much as 15 or 18 ft. They are built entirely of rough stone laid without mortar. I reckoned on an average that each wall retains a terrace not more than twice its own height in width, and I do not think I saw a single breach in one of them unrepaired” (Haig, Proceedings Geographical Society, 1887, p. 482). |

“The extent of these ancient terraces is astonishing, and there is every evidence of the past existence of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants. It would be quite impossible to convey any idea of xxxvthe immensity of labour implied in the enormous number of these ancient terraces. I saw at least 150 square miles composed of kopjes from 100 to 400 ft. in height literally strewn with the ruins. A contemplation of the enormous tonnage of stones and earth rudely built into these terraces left me amazed. It appears to be abundantly clear that the terraces were for the purpose of cultivating cereals of some sort. The terraces as a rule rise up in vertical lifts of about 2 or 3 ft., and extend backwards over a distance of mostly 7 to 12 ft. The terraces are all made very flat and of dry masonry, not of hewn stone.” |

But Mr. Hall, who visited the Inyanga territory in May, 1904, now finds that the terraced slopes,[4] the so-called “slave-pits,” and the other remains, although “old,” are not “ancient.” That is to say, they date not from Himyaritic times, but probably from the eleventh or twelfth century of the new era, when parts of Rhodesia were reoccupied by large numbers of Moslem Arabs from Quiloa and their other settlements along the east coast. Hence, although the terraced slopes still form a connecting link between South Africa and South Arabia, the South Arabia here in question is that, not of pre-, but of post-Koranic times.

Of course, the ruined houses and ruined aqueducts are too much obliterated to supply any clear points of comparison. But their mere presence, and especially the vast extent of ground covered by them, will suffice to confirm Mr. Telford xxxviEdwards’ estimate of the vast numbers of civilised peoples who inhabited the rich Inyanga valleys in prehistoric times, and whom we may now call Sabæans, Minæans, and others Himyarites.

Were the houses still extant, we should expect to find them covered with the same decorative mural motives as are still seen both on the Zimbabwe monuments and on the public buildings of Sana, present capital of Arabia Felix. Manzoni, who visited this city three times between the years 1877 and 1880, figures a mansion six stories high, which is richly ornamented with two such motives—the chevron and the vertical block pattern—closely resembling those everywhere occurring on the more ancient Rhodesian walls. The chevron, which is seen both in single and double courses exactly as on the great walls of the Elliptical Temple, is absolutely identical, while the block design differs only in being quite vertical at Sana, whereas it is slightly tilted, or else two rows of blocks converge to produce the herring-bone pattern on the Rhodesian walls, as at Little Umnukwana and many other places. The reader will find Manzoni’s mansion reproduced in Mr. D. G. Hogarth’s The Penetration of Arabia, 1904, p. 198, and he will there notice that the various motives fill up all the space between two parallel horizontal lines, as is so often the case in Rhodesia.[5] Here, therefore, style, motive, general treatment, everything corresponds between the Rhodesian remains and the decorative fancies still flourishing in Sana, heir to the cultural traditions of the neighbouring Mariaba and of the other ancient Himyaritic capitals in South Arabia.

In The Gold of Ophir frequent reference is made to the relations, social and commercial, established between Palestine and Madagascar certainly as early as the time of Solomon, and possibly even during the reign of his father David. On this point I might have spoken even more confidently, for I have since received a communication from M. Alfred xxxviiGrandidier, by far the greatest living authority on all things Malagasy, who calls my attention to the evidence supplied in his monumental work, Histoire Physique, Naturelle et Politique de Madagascar (1901), of intercourse between the Jews and the natives of Madagascar and neighbouring islands even in pre-Solomonic days. Documents are quoted to show that the Comoros, stepping-stones between Madagascar and Rhodesia, were peopled in the reign of Solomon “by Arabs or rather by Idumæan Jews from the Red Sea,” and that the people of the great island preserve many Israelitish rites, usages, and traditions, cherish the memory of Adam, Abraham, Lot, Moses, Gideon, but have no knowledge of any of the prophets after the time of David, “which seems to show that the Jewish immigrants left their home at a very remote date, since if the exodus had been recent they could not have forgotten the great names posterior to the time of David.” Hence he concludes that “there is nothing surprising in the presence of an Idumæan colony in Madagascar, for we know that from the very earliest times the Arabs of Yemen had frequented the East African seaboard at least as far as Sofala.” These words lend further support to my identification of Tharshish with Sofala, and in a note it is added that “the Jews and Arabian Semites were not the only peoples who had formerly commercial relations with the inhabitants of the African seaboard. From time immemorial these southern waters were navigated by the fleets of the Egyptians, probably even of the Chaldeans, Babylonians, Assyrians, Phœnicians, Tyrians” (op. cit., p. 96). And again at p. 100: “From the earliest times the Indian Ocean was traversed by Chaldean, Egyptian, Jewish, Arab, Persian, Indian, and other vessels.”[6]

xxxviii

My statements regarding the long-standing relations of the Northern Semites with the peoples of Madagascar and South Africa as far as Sofala are thus fully supported by the greatest authority on the subject. But there are some minds so constituted that they seem incapable of accepting a new revelation. They can do nothing but stare super vias antiquas, and will strain every nerve to minimise the force of facts and arguments pointing at conclusions which run counter to their deep-rooted prejudices. I here reproduce the famous “Zimbabwe Zodiac” (Fig. 2.), which was found near Great Zimbabwe, and shows the twelve signs of the Zodiac carved round the rim, as described by the late Dr. Schlichter in the Geographical Journal for April, 1890. This specialist tells us that “the signs coincide in every respect with other finds which Bent and others have made in Zimbabwe. One of the pictures is an image of the sun analogous to the sun-pictures which Mauch and Bent found on the monoliths of Zimbabwe, and analogous also to finds in Asia Minor which belong to the Assyro-Babylonian period.” But a writer in the Guardian attempts to destroy the significance of this document by asserting that the Zodiac or its nomenclature is of Greek origin and consequently of no great age. Now the Hon. Emmeline M. Plunket has recently (1903) published a work on Ancient Calendars and Constellations, in which she maintains that the Babylonian Calendar, with its Zodiacal signs, dates from 6000 b.c., that is, about 8,000 years ago. It is true that this estimate is not clearly made out. But on the other hand, the reader may be assured that Miss Plunket does not hold by the “Greek” theory. Nor does F. Delitzsch, who reminds us that “when we distinguish twelve signs of the Zodiac and call them Ram, Bull, Twins, etc., in all this the Sumero-Babylonian culture is still a living influence down to the present day.”[7] Nor does Sayce, who points out that the Babylonian account of the Flood occurs in the eleventh book xxxixof the epic of Gisdhubar corresponding approximately with the eleventh sign of the Zodiac, at that time Aquarius, just as the fifth book records the death of a monstrous lion by Gisdhubar, answering to the Zodiacal Leo and so on. He further observes that “the Zodiacal signs had been marked out and named at that remote period (certainly before 2000 b.c.), when the sun was still in Taurus at the beginning of spring,”[8] and, let me add, when the Greeks had not yet been heard of, but when the great Gnomon, or Conical Tower, had possibly already been erected by the Semitic builders of Great Zimbabwe.

That this and the numerous other conical towers still standing amid the crumbling ruins of Rhodesia are all cast in a Semitic mould will be at once seen by comparing them with the conical tower of a temple, figured on a medallion found at Byblos in Phœnicia and here reproduced (Fig. 1.). The comparison may also be extended to the two embossed cylinders—one from Great Zimbabwe, the other from the Temple of Paphos, in Cyprus, here also reproduced (Figs. 3 and 4) from Bent’s Ruined Cities, pp. 170, 171. These two objects, so strikingly similar in general design, reminded Bent of Herodian’s description of the sacred cone in the great Phœnician Temple of the Sun at Emessa, in Syria, which was adorned with certain “knobs or protuberances,” a pattern supposed by him to represent the sun, and common in phallic decorations, such as are constantly turning up with every shovelful of débris removed from the Zimbabwe Temple Enclosures.

But although thousands of stones have been washed and carefully examined for inscriptions, none have so far been discovered. As the inscription which stood originally above the gateway of Great Zimbabwe, as reported by the Arabs to the Portuguese pioneers early in the sixteenth century,[9] has since disappeared, there are no known written documents xlconnecting these monuments with South Arabia or Phœnicia, except a few scratches on the rim of an earthenware vessel figured by Bent and by him supposed possibly to be of Himyaritic type.[10] As, on the other hand, South Arabia is covered with Himyaritic rock inscriptions, some of considerable length and hitherto reputed to be of great age, their absence from Rhodesia has naturally caused surprise. This negative argument has even by some of my critics been allowed to outweigh the overwhelming positive evidence derived from the monuments themselves, from the hundreds of old gold-workings already described or recorded, from the multitude of objects—phalli, birds, conic towers—which have been found in the ruins, and are, beyond all doubt, intimately associated with Semitic religious observances. But I think it may now be shown that this “negative argument” is no proof at all of non-Semitic origins, but, on the contrary, affords strong indirect evidence of the great antiquity of these Semitic remains in Rhodesia.

It is to be noticed, in the first place, that although the Phœnicians are believed to have migrated from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean about three millenniums before the New Era, no Phœnician inscriptions have yet been anywhere discovered in the Mediterranean lands older than about the seventh or the eighth century b.c. Before that time the Phœnicians, like the kindred Canaanites and Israelites, were rude, uncultured peoples, with no knowledge of letters, except, perhaps, of the hieroglyphs, cuneiforms, and other scripts of their Egyptian, Assyro-Babylonian, Hittite, and Cretan neighbours. Even the Moabite Stone, if it be genuine, is post-Solomonic, since its reputed “author” was the Moabite king, Mesha, contemporary of Jehoram of Israel and Jehoshaphat of Judah. How, then, could the unlettered Jews and Phœnicians of the time of David, Solomon, and Hiram leave any written records of themselves in Rhodesia? After that xliepoch the intercourse with South Africa was interrupted, because “Jehoshaphat made ships of Tharshish to go to Ophir for gold; but they went not; for the ships were broken at Ezion-geber” (1 Kings xxii. 48). And then the star of Jacob waned, and the scattering of the Ten Tribes of Israel was presently followed by the dire calamities that fell upon Judah, and put an end for ever to all further quest of treasure in the Austral seas.

In the second place I find that Semitic students are gradually coming to the conclusion that the age of the South Arabian rock inscriptions has been greatly exaggerated, especially by Glaser, whose authority was at first naturally accepted almost without demur. The language is, no doubt, Himyaritic, that is to say, the oldest known form of Arabic. But that language survived for many centuries after the New Era in the Axumite empire, Abyssinia, where it is called Geez, and in Yemen till some time after the Mohammedan irruption, and is still current in the island of Sokotra, and in the Mahra district east of Hadramaut, where it is called Ehkili. Hence the language of the inscriptions is no test of their antiquity, though many afford intrinsic evidence that they date certainly from at least a few hundred years before the New Era. The subject is at present sub judice, and no more can be said until the full results are known of the extensive researches now in progress throughout Yemen. Here a large number of agents of the French Ministère de l’Instruction Publique have been at work since the year 1901, and thousands of impressions or rubbings have already (1903–4) been received in Paris. Some have even begun to appear in the Nouveaux Textes Yéménites, edited by M. Derenbourg, and several of the inscriptions are stated to be in a hitherto unknown alphabet quite different from that of the Himyaritic document which forms the frontispiece of the Gold of Ophir. Great revelations may therefore be pending; but, meanwhile, so much may, I think, be safely inferred, that the Himyaritesxlii who first arrived in Rhodesia, worked the mines, and built the monuments, some dating from apparently 2000 b.c., had little or no knowledge of letters, or at least had not yet begun to cover the rocks of their South Arabian homes with well-formed and carefully constructed inscriptions. Thus is also explained the absence of all such documents from their new homes in Rhodesia, where one may now almost venture to predict that none will ever be found. Nothing can be inferred from the vanished inscription over the Great Zimbabwe gateway, since the gold-workings appear to have been resumed for a time by the later (post-Mohammedan) Arabs, who were fond of decorating the façades of their mosques and other public buildings with the ornamental but relatively recent (eighth century) Cufic characters.

Mention should perhaps here be made of Professor Gustav Oppert’s Tharshish and Ophir (Berlin, 1903), in which the learned author claims to offer “a final solution” of the problem. But he leaves the question exactly as it stood over three decades ago, is still lost in the tangle of time-worn etymologies, and takes no notice at all of the revelations made by Messrs. Hall and Neal in the Ancient Ruins. The vast body of archæological evidence derived in recent years from the Rhodesian remains is thus completely ignored, and fresh light excluded from the only source whence it might have been drawn. On the other hand, Professor Oppert, rather than admit a Tharshish in the Indian Ocean, suggests that the Tharshish of Kings and Chronicles either means “the sea,” possibly the origin of the Greek word [Greek: thalatta] itself, or else was by the authors of those books foisted into the texts instead of Ophir. Hence where Tharshish occurs as the objective of Solomon’s gold expeditions we are to read Ophir, although the original Ophir is allowed to have been where I place it on the south coast of Arabia. Now the Greek word [Greek: thalatta] is Homeric, and when the Homeric poems were first sung there were no Greeks in the Indian Ocean.xliii Hence, even if the wild etymology could be admitted, it would not serve, and this essay cannot be accepted as “a final solution of the old controversy.”[11] It is pleasant to be able to add that my solution has been accepted as final by some of Professor Oppert’s fellow-countrymen—the editor of the Coloniale Zeitung amongst others—who declares that “the problem seems now really solved.”[12]

Let me conclude with a question. Those who still reject my solution, who cast about for the gold of Ophir all over the Indian Ocean—Egypt, Arabia, Persia, India—anywhere except South Africa, what do they propose doing with the hundreds of old Rhodesian workings, which are known to have yielded at least £75,000,000 in their time, and with the stupendous Semitic monuments connected with these workings, of which Mr. Hall here presents the public with scores of photographic reproductions, drawn exclusively from the central Great Zimbabwe group? Where does India, the spoilt child of the etymologists, stand beside these remains, which betray such undoubted evidence of their South Arabian origin?

ON the 21st May, 1902, I arrived at Victoria in Mashonaland, en route to the ruins of the Great Zimbabwe, which lie about seventeen miles south-east of the township. In 1891, when the late Mr. Theodore Bent visited Zimbabwe, he occupied exactly one week in covering the distance between Victoria and the ruins. Unfortunately for him and his party, he had been advised to follow the Moshagashi Valley, instead of taking the higher ground towards the west, and consequently he experienced great difficulty with his wagons in crossing spruits, rivers, and swamps, which are numerous in that direction.

There is now an excellent road to Zimbabwe, and the distance can be covered by a cyclist well within an hour and a half, while visitors driving can now arrive at Zimbabwe early in the morning and spend the whole day among the ruins and yet be in town in ample time for the evening meal. The 2distance by road is seventeen miles, and by a native path cutting across country it is reduced to fifteen miles.

Victoria is a town with barely one hundred white inhabitants. It is the centre of the largest and finest grain country of Southern Rhodesia, and the opening up of the gold, copper, and coal areas of the Sabi district will tend to increase its importance.

The Acting-Civil Commissioner, Mr. Lawlor, arranged for requisitions to be made for stores, plant, etc., required for the work at the ruins, and the Officer Commanding the British South Africa Police provided wagon and ten mules to transport stores out to Zimbabwe. The Native Commissioner, Mr. Alfred Drew, sent out M’Guti, a native police boy, to the chief Mogabe, who lives near the ruins and rules over a large tract of country and is practically independent, to find fifteen “boys” (afterwards increased to forty) to be at our camp at Zimbabwe at sun-up on Saturday. The work of collecting stores and plant filled up the rest of the day.

Early the following morning we loaded up the wagon and left for Great Zimbabwe, arriving at the main ruins at midday. The wagon was off-loaded, and in the shade of a large candelabra-shaped euphorbia tree we lunched, while the “boys” carried the stores up on to a low granite knoll, where were three spacious native huts, built for the Civil Commissioner, and occupied by Lord Milner in 1897. Of course, half the population of Mogabe’s kraal came down the kopje sides in black strings to watch all that took place, and a jabbering, laughing, noisy crowd they were. There was not a pair of trousers or a vest among the lot, and all were absolutely bare, save for their aprons. I liked their appearance better than that of the average Matabele, for they had better and more genial faces, and were not at all haughty and reserved.

The camp is within a few feet of the north side of No. 3 Ruins (see map), and faces the south side of Zimbabwe Hill, 3and the Acropolis Ruins are on the summit of a very precipitous cliff, 90 ft. high, forming part of the side of the hill, the ruins being 220 ft. directly above the camp. The camp of Mr. Theodore Bent, the archæologist, was a third of a mile to the south of our camp. Ours is the more convenient spot, as it is half-way between the two principal ruins, and close to its east side lies “The Valley of Ruins,” beside which the situation is far healthier.

Leaving the “boys” to move the stores and plant from our outspan up to the huts, we started for a visit to the Elliptical Temple, which can be seen from the camp. My friends, Mr. Herbert Hayles, of Victoria, and Mr. J. R. A. Gell (cousin of Mr. Lyttelton Gell, one of the directors of the British South Africa Company), had accompanied me out to Zimbabwe to show me the lie of the Zimbabwe Reserve, and to protect me for the first night of my stay in the event of any visits from ancient ghosts.

Approaching the west entrance to the Elliptical Temple one is confronted by the following notice:—

“The public are warned that digging or prospecting for gold, whether alluvial or otherwise, or for curiosities and relics of any sort within the Zimbabwe Reserve, is strictly prohibited without special permission, and that any person or persons found so doing or in any way damaging any of the ruins or cutting or damaging any tree or trees within such Reserve will be prosecuted. And notice is also hereby given that nobody will be allowed to erect any habitation of any kind whatever within the Reserve without special permission. By Order.”[14]

But turning from this prosaic notice to the walls themselves, one saw that every stone of this stupendous and imposing structure had gained glories from the hands of Time, and yielded a magnificent subject for the painter’s brush. The walls were white with lichen, but on their surfaces were 4splashed art colourings of almost every possible shade—bright orange and red, lemon-black, sea-green, and pale delicate yellow—while drooping from the summits were heavy festoons of the pink-flowered “Zimbabwe creeper.” Over the fallen blocks spread sprays of passion flowers, convolvuli, and other delicate creepers, and clusters of St. John’s lilies and large scarlet gladioli rose stately above beds of rich vegetation. Here was one of Nature’s most perfect chromographs!

To describe this grand ruin in one chapter would be an utterly impossible task, and any statement of one’s first impressions on walking about the temple ’mid its massive Titanic walls must be altogether inadequate. At any rate, one experienced an overwhelming and oppressive sense of awe and reverence. One felt it impossible to speak loudly or to laugh. And yet the ancient builders were what is termed Pagan—Phallic worshippers with Baal and Astoroth among their divinities, but a people so skilled in Zodiacal, astronomical, and other sciences as to amaze and perplex the savants of to-day. Standing close by the Sacred Cone, near which, according to Colonel Conder, the Syro-Arabian archæologist, the altar was placed, one felt disinclined for conversation. Above on a bough was a large owl, with prominent ears and beautiful yellow eyes, who stared at our daring to trespass on the verge of mystery. At our feet lay innumerable cast-off skins of snakes. One thought of the poet Lowell’s Lost Angel, where, speaking of a man so deadening his conscience by constant refusals to listen to the appeals of his attendant good angel, he finds that the angel has at last left him alone. Then was the temple of his heart become desecrated, “the owl and snake inhabit there, the image of the God has gone!” The owl and snake inhabit the Temple of Zimbabwe, the altar of which is now broken down and desecrated, but the odious and unmistakable emblems of Nature Worship are still to be found by the5 score. Reverence of the hoary age of these buildings seizes one, for some accredited archæologists give the age of some of these ruins as anterior to the time of Moses. One wonders whether Professor Keane’s contention is correct, that Ancient Rhodesia was the Havilah of Genesis, especially when one thinks of the estimated £75,000,000 of gold believed to have been taken by the Ancients from the surface of the gold-reefs of this country before and during the Biblical-Ophir period.

But our stay within these massive walls was brief. The writer would have over two years in which to wander in their labyrinthine passages, and to examine their architectural features, and compare them with those of Rhodesian ruins elsewhere, but his friends must start back to Victoria before sunrise next day. On our way to the other important ruins—the Acropolis or Hill Fortress—we visited the grave of Major Alan Wilson and his party[15] who were killed on the Shangani during the flight of King Lo ’Bengula in 1893.

We climbed up the 230 feet to the Acropolis ruins, but our visit here also was brief. We clambered round the summits of the walls of the two temples, which have a score of monoliths still standing, more or less erect, and penetrated some of the most intricate passages. The feeling experienced here was one of intense wonder and bewilderment at the stupendous walls erected at such a height, walls which must have taken years to build, and all of granite blocks. The view from the summit is among the finest in Rhodesia. We watched the sunset glow fading on the white walls of the Elliptical Temple below, and then descended to prepare the huts for the night and arrange the stores in their proper quarters. Later, when the round moon one day off the full was shining, we sat outside the huts watching the effects shown on the western temple on the hill where the monoliths high up above us stood out against the greenish moonlit sky. At 4 a.m. the mules were inspanned in the wagon, 6and my friends took their departure, leaving me alone among ruins and natives.

As soon as the sun was fairly up, M’Guti, the native police boy, arrived from Mogabe’s kraal, followed by a crowd of “boys,” all most anxious for work. The majority were young men, and the total clothing of the crowd did not amount to three square yards of calico. They all squatted down in a semi-circle in front of the main hut while M’Guti delivered a long oration, but as he was wearing khaki regimentals and had his steel handcuffs (evidently a badge of authority) lying in front of him, the sustaining influence of office possessed him. Finally, all the details were settled, a roll was made up, and the names recorded.

Later, the Mogabe, Handisibishe, and his headmen arrived, and a long indaba took place, M’Guti interpreting. Mogabe recognised the likenesses of Mr. and Mrs. Bent, and that of the previous Mogabe—Chipfuno, his brother. Salt and tobacco sent Mogabe happy away, and next day a large gourd of doro (native beer) and some sweet potatoes arrived at the camp as a present.

The view from the summit of the Acropolis may be described as follows:—

South.—Towards the south and in the nearer distance, and 250 feet below in the valley, the venerable and lichened walls of the Elliptical Temple rise out of luxuriantly green vegetation. So much below the Acropolis cliffs is this temple that one sees over its broken north walls into the interior and on to the floors of some of the enclosures. The summit of the conical tower peeps out from among the giant fig-trees that flourish in the interior of the building. At this distance the white monoliths along the eastern wall, though clearly defined against the dark foliage, seem dwarfed. In almost the same line of view, but slightly eastwards and nearer, and on the north-east side of the temple, is the “Valley of Ruins,” full of enclosures, passages, entrances,7 and walls, which up to 1902 had remained practically unexplored by white men. Nearer still is the wagon-track passing Havilah Camp and winding eastwards towards the Mapaku Ruins (“Little Zimbabwe”) and the Motelekwe[16] River seven miles distant. A hundred yards east of the temple on an open granite space overlooking the Valley of Ruins is the site of the camp of Dr. Schlichter, who visited the Zimbabwe ruins in 1897. Immediately behind this spot and between it and the foot of the Bentberg (Motusa) is the veld land ploughed by Messrs. Posselt in 1888–9.

Still looking south and slightly eastwards of the temple is the Schlichter Gorge, down which the Mapudzi flows towards 8the south. At the southern end of the gorge is a succession of ranges of kopjes of fantastic shape descending into, and again rising from, the Mowishawasha Valley, and becoming lost in the blue distance. The Bentberg Kopje, which forms a dark background for the temple, shows its immense flanks of granite glacis and boulders. Here some fifty years ago was the chief local kraal of the Barotse, who had settlements among the Makalanga of this part of the country, and on the north-eastern side of the hill are still to be seen the remains of ancient walls, while a clump of castor-oil trees at the foot of the hill on this side marks the site of Theodore Bent’s camp (June and July, 1891).

Slightly to the west of the temple and almost immediately in front of it are No. 1 Ruins, the walls of which are crowned with aloes and euphorbias. Less than a hundred yards west of these ruins are the Ridge Ruins, on a bare granite ridge, on the east side of which was the camp of Sir John Willoughby, who excavated portions of the ruins (November and December, 1892). Fifty yards behind the Ridge Ruins is the Zimbabwe Spring, marked by a group of trees, where most excellent water can be obtained, even during the driest season. It was close to these trees that Messrs. Posselt had their camp in 1888–9. Nearer than Ridge Ruins is the little graveyard where is the granite tomb of Major Alan Wilson and his party. Just a few yards nearer is Havilah Camp, where one can just see the natives moving to and fro across the open spaces between the huts. Behind the Bentberg and further south is broken country, with Lumbo Rocks, one of the landmarks of the district, rising from the summit of a rugged hill like a column piled up against the sky, its lichen mantle showing brilliant red in the sunset. Here is the line of high ground which separates the plateau of Mashonaland from the lower valley of the Limpopo River, the incline in the contour being both steep and abrupt. This also divides 9the watershed of the Motelekwe from that of the Tokwe.[17] In this southern view are scattered many Makalanga kraals, several of which are perched up in almost inaccessible rocky eyries; also some romantic valleys, kloofs, and stretches of park-like land studded with patches of thick woods.

South-west.—Looking towards the south-west and in the near distance is the rising ground between the Bentberg and Rusivanga[18] kopjes, and the native path leading over it to Bingura’s kraal. At the foot of Rusivanga and 150 yards from Havilah Camp, and on a knoll on which is a large old tree, was for some time the camp of Adam Renders, known by the natives as Sa-adama, who rediscovered Zimbabwe in 1868, and who was here visited by Mr. George Philips, the ivory trader of the very early days, and by Dr. Karl Mauch, the latter of whom gave in 1871 the first information of the ruins for almost three hundred years. Here Renders traded extensively for ivory. Previously to Dr. Mauch’s visit Renders lived at Nini, eleven miles south-west of Zimbabwe.

Beyond the nearer ridge is a deep and wide valley on the near side of which is Bingura’s kraal, and from this valley the land rises towards the southern extremity of the Livouri Mountains some ten miles from Zimbabwe, and in the immediate distance, though much nearer the Livouri Range, is Providential Pass, through which the hunter, Mr. F. C. Selous, led the Pioneer Column in 1890. In the same line of view, but slightly nearer, is where Renders’ first station was located.

West.—Looking due west there are two kopjes—Rusivanga and Makuma—which close in the Zimbabwe Valley on that side at a third of a mile distance. Further west of the two kopjes is a wide undulating valley some six or eight miles 10wide which runs along the east side of the Livouri Mountains, and this is studded at intervals with low and bare granite kopjes. The kraal of the dynastic chief Cherimbila is at Rovali, at the southern extremity of the range. The highest point of the Livouri is Niande, a hill in the centre of this range with steep and almost inaccessible sides. Behind the Livouri Range is seen the high conical summit of the Cotopaxi Mountain, which forms one of the principal landmarks of this portion of Southern Mashonaland. Towards the south end of the Livouri Range is a large hill called Mowishawasha. Washa is always associated by the natives with power and authority. The natives never climb to the top of this hill without going through some form of devotion on their way up; also on passing close to the hill they will stop and clap hands. Natives will not state the actual reason. Probably an important Makalanga chief of some past times was buried there. Near to this hill is a smaller one known as Tchib-Fuko, which also has some native superstitions attached to it. It was in this district the wooden platter with the zodiacal signs was discovered by Mr. Edward Muller, also the pot “Fuko-ya-Nebandge.”

North-west.—To the north-west, and on the opposite side of the valley at the foot of Zimbabwe Hill, and beyond the Outer Defence Wall which encloses the Zimbabwe ruins on the west and north sides, is a low granite knoll called Pasosa, with outlying huts belonging to Mogabe’s kraal. A few yards behind the huts is a ruin (Pasosa, No. 1), with a second ruin (Pasosa, No. 2) 60 yards farther north. The country beyond in this direction is the valley land of the Moshagashi River, which is some six to eight miles broad, the horizon showing low hills, over which are the line of houses and trees of Victoria township, fifteen miles distant as the crow flies, and beyond again are the uplands of the range north of Victoria. The principal kraals in this direction are Baranzimba’s (two miles) and M’Tima’s (three and a half miles).

11

North.—In the north is the lower continuation of the Moshagashi Valley, at this point some eight miles broad. Here the granite formation of Zimbabwe terminates and the slate commences. The principal kraal, and by far the largest in this area, is that of Chinongu, which is four miles from Zimbabwe. Extending from N.N.W. to N.N.E. are the high and romantically shaped Besa Mountains, and at their eastern extremity can be seen in the blue distance the Lovugwe country.

North-east.—To the north-east, at a distance of eight miles and cutting the sky-line, is the range of the Inyuni Hills. Their sides are exceedingly steep and, being slate, their contours contrast pleasantly with those of the kopjes of the granite formation. In the nearer distance is Motuminshaba, a granite kopje four miles away, and farther east Tchivi, another granite kopje three miles distant. The land towards the east-north-east descends to the Motelekwe River, the valley of which can be seen with Arowi, a huge, isolated granite kopje rising twelve miles distant, on the far bank of the Motelekwe. In this area kraals are numerous.

East.—The Beroma Range (written by Bent as “Veroma”) fills in the whole of the background towards the east. These hills, which run north and south, appear to be fully four miles long. The most northerly point of this range is formed by a large rounded granite kopje called Sueba,[19] and between this hill and Chenga’s[20] kraal is the path leading over the nek to the Mapaku Ruins (“Little Zimbabwe”) eight miles distant. On the west side of Beroma is a line of lower hills forming its shoulders. The southern end of the Beroma Range is formed by the high rounded Mount Marsgi, with a series of cliffs on its west side, and at its base M’Tijeni’s kraal. Marsgi overlooks the Schlichter Gorge. This is the point from which our description started.

WANDERING about the Elliptical Temple at Zimbabwe on a Sunday morning one is faced at every turn with texts for innumerable “sermons in stones.” The hoary age of these massive walls is grandly and silently eloquent of a dead religion—a religion which was but the blind stretching forth of the hand of faith groping in the Dawn of Knowledge for the Deity and seeking the Unknown. Lowell urges that none should call any faith “vain” which in the evolution of religion has led mankind up to a higher level. The builders were “Pagans.” Granted, but the world four thousand years ago was in its infancy, and infancy is but a necessary prelude to development in any department of life and thought. The progressive stages of Old Testament faith demonstrate this fact most patently. We of the Christian Era, with our two thousand years of religious enlightenment, have yet to learn of the “many things I have to say unto you, but ye cannot bear them now.” The evolution of the Christian Ideal has not yet reached its final stage—it has still to be perfected. But the period of infancy in development should not be too hastily condemned as “vain.”

The spires that adorn our churches, the orientation of ecclesiastical buildings, the eastward position of the dead, the candles on the altars, and what is more, the idea conveyed by sacrificial offering, have their origin in the ancient faiths13 and world-wide litholatrous and solar ideas of the Semitic peoples, whether of Yemen or Phœnicia, who built their temples in every part of the then known world which came under their influence. In these, as in many more such instances, parallelisms become identities, but identities adapted by the Christian Church to convey in an old-world form a figure of a higher faith. The continuity between this old temple at Zimbabwe, Stonehenge, and the modern cathedral, is complete.

When one reviews the forms and practices, so far as they are known, of the Semitic builders of the Great Zimbabwe, what a flood of light shines in upon the history and worship of the Hebrews. The writings of the Prophets live afresh, and the mystic chapters of Job become full of pregnant meaning. A key is provided to the secret of Abraham offering his son, to Jacob’s pile of stones, to Jephthah’s vow, to the Syro-Phœnician woman’s conversation at the well, and to a hundred points of biblical lore which would otherwise barely attract attention, much less provoke interest. These old Semites—of whom the Hebrews were a younger branch—stinted not their worship, and knew the ecstasy of sacrifice. Their best beloved they gave—their dearest, in the belief that the gift which was offered without a pang was not prized by Deity. Bearing this in mind, the Old Testament is found to be replete with unfailing interest, charm, and point; it becomes, in fact, a marvellously new book even to the biblical student.

The builders of the temple at Zimbabwe have now, it is believed, slept through three millenniums, if not four, yet the religious faith of the Semitic family was so strong, so real, and so forceful, that its ramifications can be found in the faith of the Christian Church of to-day. Nor can this be wondered at. One has but to glance round these temple walls to read in granite blocks the fact that to the builders their religious faith was of primal importance. Here is14 clearly envisaged the fact that to them their religion was very real, so much so that were Europe devastated to-morrow, it could scarcely show in proportion to its other buildings such monuments to religious faith as can be seen in Rhodesia to-day. Their finest art, their best constructive skill, and the patient labour of long years, were lavished upon these buildings which thickly stud the country. Thoroughness and devotion are written large on the orientated, massive, and grandly sweeping walls of the Elliptical Temple at Great Zimbabwe. One cannot call their faith “vain” when one realises that it led them out from themselves towards something higher, while for them it must be remembered the True Light had not shined. Struggling though blindly to improve their relationship to Deity provided a no mean factor in the religious progress of the world.