AND OTHER STORIES

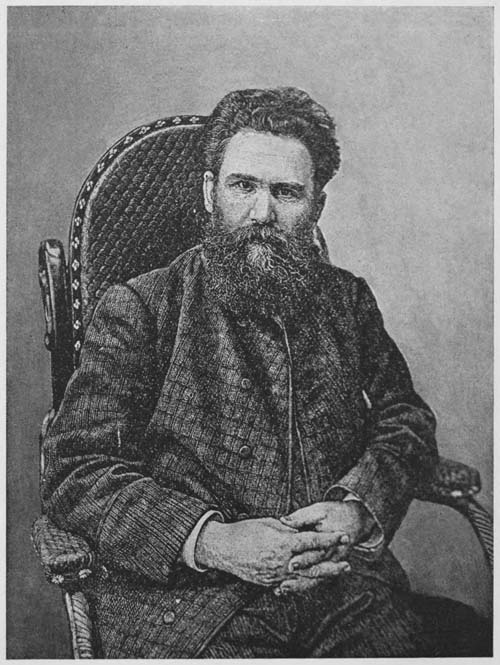

VLADIMIR KOROLENKO

MAKAR’S DREAM

AND OTHER STORIES

BY

VLADIMIR KOROLENKO

TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN WITH AN

INTRODUCTION BY

MARIAN FELL

NEW YORK

DUFFIELD AND COMPANY

1916

Copyright, 1916, by

DUFFIELD & CO.

The writings of Vladimir Korolenko have been likened to “a fresh breeze blowing through the heavy air of a hospital.” The hospital is the pessimistic literature of the modern Russian intellectuals; the fresh breeze is the voice of the simple-hearted children of “Mother Russia.” These are for the most part tillers of the soil and conquerors of waste places; peasants, pioneers, and Siberian exiles; they often belong to the great class of “the insulted and the injured”: they suffer untold hardships, but their heads are unbowed and their hearts are full of courage and the desire for justice. Among them the great writer’s early life was spent.

Vladimir Korolenko was born on June 15th, 1853, in Zhitomir, a small town in Southwestern or Little Russia. On his father’s side he came of an old Cossack family, his mother was the daughter of a Polish landowner of Zhitomir. The boy’s early life was spent amidst picturesque surroundings; he grew up among the Poles, Jews, and light-hearted, dark-eyed peasants that make up the population of Little Russia, and he never lost the poetic love of nature and the wholesome sense of humour that were nurtured[viii] in him under those warm, bright skies. In his story entitled “In Bad Company” he has vividly described the romantic little town that was the home of his childhood. The stern but just judge of that tale is more or less the prototype of his own father. The elder Korolenko was distinguished for an impeccable honesty of practice rare in an official of those times; consequently, when he died in 1870, he left his widow and five children without the slightest means of support. Thanks, however, to the energy of his heroic mother, Vladimir was enabled at seventeen to enter the School of Technology in Petrograd.

Then followed three years of struggle to combine his schooling with the necessity for earning a living, during which Korolenko himself says that he does not know how he managed to escape starvation. Even a cheap dinner of eighteen copecks or nine cents was such a luxury to him in those days that he only treated himself to it six or seven times during the course of one whole year.

In 1874 the young student went to Moscow with ten hard-earned roubles in his pocket and entered the Petrovski Academy, but he was soon expelled from that seat of learning for presenting a petition from his fellow-students to the Director of the College. He returned to Petrograd where his family were now living, and he and his brother made a desperate attempt to support themselves and their brothers and sisters by proof-reading. The future[ix] author began sending articles to the newspapers and magazines, and it was then that occurred the first of the series of arrests to which he was subjected for what were considered his advanced social doctrines. He was sent first to Kronstadt for a year and then to Viatka; thence he travelled to Perm, and from Perm to Tomsk; at last he was finally exiled to the distant eastern Siberian province of Yakutsk.

There he spent nearly six years, the most valuable, to him, of his whole life. The vast forest that clothes those far northeastern marshes, grand, gloomy, and held forever in the grip of a deadly cold, made an indelible impression on the imagination of the young artist. He was profoundly moved by the sorrows of the half-savage pioneers inhabiting its trackless solitudes, by the indomitable spirit of his fellow-exiles, and by the adventurous life of the “brodiagi” or wanderers, convicts escaped from prison who return secretly on foot to their “Mother Russia” across the whole breadth of the Siberian continent.

Korolenko was released from exile in 1885, and immediately on his return to Russia published his beautiful “Makar’s Dream.”

The success of the story was immediate, the fame of the author was at once assured. No politics, no social doctrines were here; the appeal of Makar’s plea was universal; liberal and conservative critics alike united in a chorus of praise. The Russian reading public was charmed by the originality of the[x] subject, the radiant conciseness of the author’s style, and the lyric beauty of the story’s end which illuminates with deep significance every detail that has gone before. Poor Makar, most lonely dweller in the Siberian forest, leading a life of incredible labour and hardship, finally dies, and for his sins is condemned at the Judgment of the Great Toyon, or Chief, to suffer in the life hereafter sorrows and toil more grievous than any he has known on earth. Here is the type of “the insulted and the injured” beloved of Dostoievsky and Tolstoi, but with one supreme difference: Makar does not suffer misfortune in passive dejection, he protests. He protests indignantly against the injustice of the judgment of the Great Toyon. Life for him has been desperately hard; it is unjust to judge him by the standards set for the righteous whom the Toyon loves, “whose faces are bathed in perfume and whose garments are sewn by other hands than their own.” This protest, combined with a warm love for all humanity, was to become the keynote of Korolenko’s writings.

His next story, “In Bad Company,” appeared in the same year, and added still more to the young author’s popularity. It is a general favourite in Russia to this day. Though its style is slightly tainted with a flowery Polish exuberance, the descriptions of the old feudal ruins are full of poetry, the children are drawn with sympathy and insight, and the vagabond Turkevich, in his tragi-comic rôle[xi] of the Prophet Jeremiah, sounds an unmistakable note of protest.

“The Murmuring Forest” was published in 1886, and is a darkly romantic tale of the dreaming pine forests of Southern Russia, written in the style of an ancient legend. Here the protest of the Cossack Opanas and the forester Raman is blind and rude and brings death to their highborn oppressor, but the plot is laid in feudal times and the need of the serfs was great. The voice of the wind in the tree-tops dominates the unfolding of the simple story like a resonant chord, and when at last fierce justice is done to the tyrant Count, its advent seems as inevitable as the breaking of the thunder-storm that, during the whole course of the tale, has been brewing over the forest.

“The Day of Atonement” is one of Korolenko’s lightest and gayest stories. In describing the merry life of the South, the Little Russian’s kindly humour joins hands with his glowing imagination, and we have a vivid glimpse of a cosy village surrounded by cherry gardens and bathed in warm moonlight; of black-eyed girls, of timid, bustling Jews, of superstitious townsmen, of a canny miller; in short, of all the busy, active life of a town within the Jewish Pale.

But grave or gay, merry or sad, Korolenko is above all things an optimist in his outlook on the world. Through thick and thin, through sorrow and misfortune, the poor, artless heroes of his stories all[xii] turn their faces towards the light. The writer’s kind heart never ceases its search for the “eternally human” in every man, and deeply does he sympathise with mankind’s unquenchable desire for freedom and justice, which can face evil unafraid. He himself has said in a letter to a friend: “The Universe is not the sport of accidental forces. Determinism, Evolution, and all other theories lead one to confess that there is a law which is drawing us toward something; toward something which we call ‘good’ in all its manifestations, that is to say toward kindness, truth, right, beauty, and justice.”

That is the burden of Korolenko’s message to the world, embodied in all his writings.

On his return from Siberia, Korolenko went to live in Nijni-Novgorod and there took an active part in bettering the conditions of life among “the insulted and the injured” whom he loved. In a year of famine he worked hard to organise free kitchens for the starving poor, and many energetic articles from his pen were published in the papers. He also continued to produce stories, sketches, and several longer novels, of which the best known is the “Blind Musician.”

In 1894 he made a journey to England and America, and on his return wrote an amusing record of his travels entitled: “Without a Tongue.”

In 1895 he became the editor of the magazine, Russkoye Bogatsvo, and since that date the great[xiii] story writer has definitely devoted himself to journalism, and has now become one of Russia’s greatest publicists.

The Russian heart is essentially charitable and full of human kindness. Thoroughly democratic in their relations with one another, the Russian people have the misfortune to labour under the harshest political régime in Europe. Like many of his countrymen, Korolenko now devotes his life to the cause of the suffering and the downtrodden, and to helping those who are the victims of social and political injustice.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | v |

| Makar’s Dream | 1 |

| The Murmuring Forest | 49 |

| In Bad Company | 89 |

| The Day of Atonement | 191 |

A CHRISTMAS STORY

This dream was dreamed by poor Makar, who herded his calves in a stern and distant land, by that same Makar upon whose head all troubles are said to fall.

Makar’s birth place was the lonely village of Chalgan, lost in the far forests of Yakutsk. His parents and grandparents had wrested a strip of land from the forest, and their courage had not failed even when the dark thickets still stood about them like a hostile wall. Rail fences began to stretch across the clearing; small, smoky huts began to crowd thickly upon it; hay and straw stacks sprang up; and at last, from a knoll in the centre of the encampment, a church spire had shot toward heaven like a banner of victory.

Chalgan had become a village.

But while Makar’s forbears had been striving with the forest, burning it with fire and hewing it with steel, they themselves had slowly become savage in their turn. They married Yakut women, spoke the language of the Yakuts, adopted their customs, and gradually in them the characteristics of the Great Russian race had been obliterated and lost.

Nevertheless, my Makar firmly believed that he was a Russian peasant of Chalgan, and not a nomad[4] Yakut. In Chalgan he had been born, there he had lived and there he meant to die. He was very proud of his birth and station, and when he wished to vilify his fellow-townsmen would call them “heathen Yakuts,” though if the truth must be told, he differed from them neither in habits nor manner of living. He seldom spoke Russian and, when he did, spoke it badly. He dressed in skins, wore “torbas” on his feet, ate dough-cakes and drank brick-tea, supplemented on holidays and special occasions with as much cooked butter as happened to be on the table before him. He could ride very skilfully on an ox, and when he fell ill he always summoned a wizard, who would go mad and spring at him, gnashing his teeth, hoping to frighten the malady out of his patient and so drive it away.

Makar worked desperately hard, lived in poverty, and suffered from hunger and cold. Had he a thought beyond his unceasing anxiety to obtain his dough-cakes and brick-tea? Yes, he had.

When he was drunk, he would weep and cry: “Oh, Lord my God, what a life!” sometimes adding that he would like to give it all up and go up on to the “mountain.” There he need neither sow nor reap, nor cut and haul wood, nor even grind grain on a hand millstone. He would “be saved,” that was all. He did not know exactly where the mountain was, nor what it was like, he only knew that there was such a place, and that it was somewhere far away,[5] so far that there not even the District Policeman could find him. Of course there he would pay no taxes.

When sober he abandoned these thoughts, realising perchance the impossibility of finding that beautiful mountain, but when drunk he grew bolder. Admitting that he might not find that particular mountain, but some other, he would say: “In that case I should die.” But he was prepared to start, nevertheless. If he did not carry out his intention, it was because the Tartars in the village always sold him vile vodka with an infusion of mahorka[A] for strength, and this quickly made him ill and laid him by the heels.

It was Christmas Eve, and Makar knew that to-morrow would be a great holiday. This being the case, he was overpowered with a longing for drink, but to drink there was nothing. His resources were at an end. His flour was all gone, he was already in debt to the village merchants and Tartars, yet to-morrow was a great holiday, he would not be able to work, what could he do if he did not get drunk? This reflection made him unhappy. What a life it was! He had not even one bottle of vodka to drink on the great winter holiday.

Then a happy thought came to him. He got up and put on his ragged fur coat. His wife, a sturdy,[6] sinewy woman, remarkably strong and equally remarkably ugly, who saw through all his simple wiles, guessed his intentions as usual.

“Where are you going, you wretch? To drink vodka alone?”

“Be quiet. I’m going to buy one bottle. We’ll drink it together to-morrow.”

He gave her a sly wink and clapped her on the shoulder with such force that she staggered. A woman’s heart is like that; though she knew that Makar was deceiving her, she surrendered to the charms of that conjugal caress.

He went out of the house, caught his old piebald pony in the courtyard, led him by the mane to the sleigh, and put him in harness. The piebald soon carried Makar through the gates and then stopped and looked enquiringly at his Master, who was sitting plunged in thought. At this Makar pulled the left rein, and drove away to the outskirts of the village.

On the edge of the village stood a little hut out of which, as out of the other huts, the smoke of a little fire rose high, high into the air, veiling the bright moon and the white, glittering hosts of stars. The flames crackled merrily and sparkled through the dim icicles that hung about the doorway. All was quiet inside the courtyard gates.

Strangers from a foreign land lived here. How they had come, what tempest had cast them up in[7] that lonely clearing, Makar knew not, neither cared to know, but he liked to trade with them, for they neither pressed him too hard nor insisted upon payment.

On entering the hut, Makar went straight to the fireplace and stretched out his frozen hands over the blaze, crying “Tcha” to explain how the frost had nipped him.

The foreigners were at home; a candle was burning on the table although no work was being done. One man was lying on the bed blowing rings of smoke, pensively following their winding curves with his eyes, and intertwining with them the long threads of his thoughts.

The other was sitting over the fire thoughtfully watching the sparks that crept across the burning wood.

“Hello!” said Makar, to break the oppressive silence.

He did not know—how should he—the sadness that filled the hearts of the two strangers, the memories that crowded their brains that evening, the visions they saw in the fantastic play of fire and smoke. Besides, he had troubles of his own.

The young man who sat by the chimney raised his head and looked at Makar with puzzled eyes, as if not recognising him. Then, with a shake of his head, he quickly got up from his chair.

[8]“Ah, good evening, good evening, Makar. Good. Will you have tea with us?”

“Tea?” Makar repeated after him. “That’s good. That’s good, brother; that’s fine.”

He began quickly to take off his things. Once free of his fur coat and cap he felt more at his ease, and, seeing the red coals already glowing in the samovar, he turned to the young man with exaggerated enthusiasm.

“I like you, that is the truth. I like you so, so very much; at night I don’t sleep——”

The stranger turned, and a bitter smile crept over his face.

“You like me, do you?” he asked. “What do you want?”

“Business,” Makar answered. “But how did you know?”

“All right. When I’ve had tea I’ll tell you.”

As his hosts themselves had offered him tea, Makar thought the moment opportune to press the point farther.

“Have you any roast meat?” he asked. “I like it.”

“No, we haven’t.”

“Well, never mind,” replied Makar soothingly. “We’ll have that some other time, won’t we?” And he repeated his question: “We’ll have that some other time?”

“Very well.”

Makar now considered that the strangers owed[9] him a piece of roast meat, and he never failed to collect a debt of this kind.

Another hour found him seated once more in his sled, having made one whole rouble by selling five loads of wood in advance on fairly good terms. Now, although he had vowed and sworn not to drink up the money until to-morrow, he nevertheless made up his mind to do so without delay. What odds? The pleasure ahead silenced the voice of his conscience; he even forgot the cruel drubbing in store for his drunken self from his wife, the faithful and the deceived.

“Where are you going, Makar?” called the stranger laughing, as Makar’s horse, instead of going straight ahead, turned off to the left in the direction of the Tartar settlement.

“Whoa! Whoa! Will you look where the brute is going?” cried Makar to exculpate himself, tugging hard at the left rein nevertheless and slyly slapping his pony’s side with the right.

The clever little horse stumbled patiently away in the direction required by his master, and the scraping of the runners soon stopped in front of a Tartar house.

At the gate stood several horses with high-peaked Yakut saddles on their backs.

The air in the crowded hut was stifling and hot; a dense cloud of acrid mahorka smoke hung in the[10] air and wound slowly up the chimney. Yakut visitors were sitting on benches about the room or had clustered around the tables set with mugs full of vodka. Here and there little groups were gathered over a game of cards. The faces of all were flushed and shining with sweat. The eyes of the gamblers were fiercely intent on their play, and the money came and went in a flash from pocket to pocket. On a pile of straw in a corner sat a drunken Yakut, rocking his body to and fro and droning an endless song. He drew the wild, rasping sounds from his throat in every possible key, repeating always that to-morrow was a great holiday and that to-day he was drunk.

Makar paid his rouble and received in return a bottle of vodka. He slipped it into the breast of his coat and retired unnoticed into a corner. There he filled mug after mug in rapid succession and gulped them down one after another. The liquor was vile, diluted for the holiday with more than three quarters of water, but if the dole of vodka was scant, the mahorka had not been stinted. Makar caught his breath after each draught, and purple spots circled before his eyes.

The liquor soon overpowered him; he also sank down on the straw, folded his arms around his knees, and laid his heavy head upon them. The same dreary, rasping sounds burst of their own accord from his throat; he sang that to-morrow was a[11] great holiday and that he had drunk up five loads of wood.

Meanwhile the hut was filling with other Yakuts who had come to town to go to church and to drink Tartar vodka, and the host saw that soon there would be no room for more. He rose from the table and looked at the company, and, as he did so, his eye fell upon Makar and the Yakut sitting in their dark corner. He made his way to the Yakut, seized him by the coat collar, and flung him out of the hut. Then he approached Makar.

As a citizen of Chalgan, the Tartar showed him greater respect; he threw the door open wide and gave the poor fellow such a kick from behind that Makar shot out of the hut and buried his nose in a snow-drift.

It would be difficult to say whether Makar was offended by this treatment or not. He felt snow up his sleeves and on his face, picked himself up somehow out of the drift, and staggered to where his piebald was standing.

The moon had by now risen high in the heavens and the tail of the Great Bear was dipping toward the horizon. The cold was tightening its grasp. The first fiery shafts of the Aurora were flaring up fitfully out of a dark, semicircular cloud in the north and playing softly across the sky.

The piebald, realising, it seemed, his master’s condition, trudged carefully and soberly homeward.[12] Makar sat in his sled, swaying from side to side, and continued his song. He sang that he had drunk away five loads of wood, and that his old woman would kill him when he got home.

The sounds that burst from his throat rasped and groaned so dismally through the evening air that his friend the foreigner, who had climbed up on to his roof to close the mouth of the chimney, felt more than ever unhappy at the sound of Makar’s song.

Meanwhile the piebald had drawn the sled to the top of a little hill from where the surrounding country could be distinctly seen. The snowy expanse lay shining brightly, bathed in the rays of the moon, but from time to time the moonlight faded and the white fields grew dark until, with a sudden flash, the radiance of the Northern Lights streamed across them. Then it seemed as if the snowy hills and the forest that clothed them were coming very close, to withdraw once again into the distant shadow. Makar spied plainly through the trees the silvery bald crown of the little knoll behind which his traps were waiting for all the wild dwellers of the forest. The sight of this hill changed the tenor of his thoughts. He sang that a fox had been caught in one of his snares; he would sell the pelt in the morning, and so his wife would not kill him.

The first chimes of the church bells were ringing through the frosty air as Makar re-entered his hut. His first words were to tell his wife that a fox had[13] been caught in one of his traps, and as he had forgotten entirely that the old woman had not shared his vodka, he was violently surprised when she gave him a cruel kick, without paying any attention to his good news.

Later, as he lay prostrate on the bed, she managed to give him another blow in the back with her fist.

Meanwhile the solemn, festal chiming of the bells broke over Chalgan and floated far, far away into the distance.

He lay on his bed with his head burning and his vitals on fire. The strong mixture of vodka and mahorka was coursing through his veins, and trickles of melted snow were running down his face and back.

His wife thought him asleep, but he was not sleeping. He could not get the idea of that fox out of his head. He had succeeded in convincing himself absolutely that a fox had been caught in one of his traps, and he even knew which trap it was. He saw the fox pinned under the heavy log, saw it tearing at the snow with its claws and struggling to be free, while the moonbeams stole into the thicket and played over its red-gold fur. The eyes of the wild creature were glowing at his approach.

He could stand it no longer. He rose from his bed, and started to find his faithful pony who was to carry him into the forest.

But what was this? Had the strong arms of his[14] wife really seized him by the collar of his fur coat and thrown him back on the bed?

No, here he was, already beyond the village. The runners of his sleigh were creaking smoothly over the hard snow. Chalgan had been left behind. The solemn tones of the church bells came floating along his trail, and on the black line of the horizon bands of dark horsemen in tall, pointed hats were silhouetted against the bright sky. The Yakuts were hurrying to church.

The moon went down, and a small, whitish cloud appeared in the zenith, shining with suffused, phosphorescent lustre. It gathered size, it broke, it flickered, and rays of iridescent light spread swiftly from it in all directions, while the dark, semicircular cloud in the north grew blacker and blacker, more sombre than the forest which Makar was approaching.

The road wound through a dense, low thicket with little hills rising on either hand; the farther it advanced, the higher grew the trees, until at last the taiga[B] closed about it, mute and pregnant with mystery. The naked branches of the larches drooped under their loads of silvery rime. The soft radiance of the Aurora filtered through the tree-tops, and strayed across the frosty earth, unveiling now an icy glade, now the fallen trunk of some giant of the forest half buried in the snow.

Another moment, and again all was sunk in murky[15] darkness, full-fraught with secrecy and silence. Makar stopped. Here, almost at the side of the road, were set the first units of an elaborate system of traps. He could see clearly in the phosphorescent light the low stockade of fallen timber and the first trap—three long, heavy logs resting upon an upright post, and held in place by a complicated arrangement of levers and horse-hair ropes.

To be sure, these traps were not his, but might not a fox have been caught in them, too? Makar quickly got out of his sled, left the clever piebald standing in the road, and listened attentively.

Not a sound in the forest! Only the solemn ringing of the church bells came floating as before from the distant, invisible village.

There was nothing to fear. Aliosha, the owner of the traps and Makar’s neighbour and bitter enemy, was no doubt in church. Not a track could be seen on the smooth breast of the new-fallen snow.

Makar struck into the thicket—no one was there.

The snow creaked under foot. The log traps lay side by side like a row of cannon with gaping jaws, in silent expectation.

Makar walked up and down the line without finding anything, and turned back to the road.

But what was that? A faint rustle! The gleam of red fur near at hand in a spot of light! Makar saw clearly the pointed ears of a fox; it waved its bushy tail from side to side as if to beckon him[16] into the forest, and vanished among the tree-trunks in the direction of his traps. Next moment a dull, heavy thud resounded through the forest, ringing out clearly at first, and then echoing more faintly under the canopy of trees, until it died softly away in the dark abysses of the taiga.

Makar’s heart leapt—a trap had fallen!

He sprang toward the sound, pushing his way through the undergrowth. The icy twigs whipped his eyes and showered snow in his face; he stumbled and lost his breath.

At last he ran into a clearing that he himself had made. Hoary white trees surrounded the little glade, and a shrinking path crept across it, with the mouth of a large trap guarding its farther end. A few steps more and——

Suddenly, the figure of a man appeared on the path near the trap—appeared and vanished. Makar recognised Aliosha. He saw distinctly his short, massive, stooping form and his walk like a bear’s. His dark face looked blacker than he had ever seen it, Makar thought, and his large teeth showed in a wider grin than ever.

Makar was seized with genuine anger. “The scoundrel! He has been at my traps!” It was true that Makar had just made the round of Aliosha’s traps, but that was a different matter. The difference was that when he visited other men’s traps he felt afraid of being discovered, but when others came[17] to his traps, he felt indignation and a longing to lay hands on the man who had violated his rights.

He darted toward the fallen trap. There was the fox! Aliosha, too, was approaching with his shuffling bear’s walk; Makar must reach the trap first!

There lay the fallen log and under it glistened the ruddy coat of the captive creature. The fox was scratching at the snow with its paws exactly as Makar had seen it scratch in his dream, and was watching his approach with bright, burning eyes, just as he had dreamt that it would.

“Titima! (Don’t touch it!) It is mine!” cried Makar to Aliosha.

“Titima!” came Aliosha’s voice like an echo. “It is mine!”

Both men ran up at the same moment, and both began quickly to raise the log, freeing the animal beneath it. As the log was lifted the fox rose too. It gave a little jump, stopped, looked at the two men with mocking eyes, and then, lowering its nose, licked the place that had been caught under the log. This done it hopped gaily away with a farewell flirt of its tail.

Aliosha would have thrown himself after it, but Makar caught him by the coat tails.

“Titima!” he cried. “It is mine!” And he started after the fox.

“Titima!” echoed Aliosha’s voice again, and Makar[18] felt himself seized, in turn, by the tails of his coat, and saw Aliosha dart forward.

Makar was furious. He forgot the fox and rushed after Aliosha, who now turned to flee.

They ran faster and faster. The twigs of the larches knocked the cap from Aliosha’s head, but he could not stop to regain it. Makar was already upon him with a fierce cry. But Aliosha had always been more crafty than poor Makar. He suddenly stopped, turned round, and lowered his head; Makar ran straight into it with his stomach and turned head over heels in the snow. As he fell, that infernal Aliosha snatched the cap from his head and vanished into the forest.

Makar rose slowly to his feet. He felt thoroughly beaten and miserable. The state of his mind was pitiful. The fox had been in his hands and now—he thought he saw it again in the darkening forest wave its tail gaily once more and vanish forever.

Darkness was falling. The little white cloud in the zenith could barely be seen, and beams of fading light were flowing wearily and languidly from it as it gently melted away.

Sharp rivulets of icy water were running in streams over Makar’s heated body; the snow had gone up his sleeves and was trickling down his back and into his boots. That infernal Aliosha had taken away his cap and Makar well knew that the pitiless[19] cold does not jest with men who go into the taiga without gloves and without a hat.

He had already walked far. According to his calculations he should long since have been in sight of the church steeple, but here he was still in the forest. The taiga held him in its embrace like a witch. The same solemn ringing came to his ears from afar; he thought he was walking toward it, but the sound kept growing more and more distant, and a dull despair crept into Makar’s heart as its echoes came ever more faintly to his ears.

He was tired; he was choking; his legs were shaking under him. His bruised body ached miserably, his breathing strangled him, his feet and hands were growing numb, and red-hot bands seemed tightening around his bare head.

“I shall die!” came more and more frequently into his mind, but still he walked on.

The taiga held its peace. It closed about him with obdurate hostility and gave him no light and no hope.

“I shall die!” Makar kept thinking.

His strength left him altogether. The saplings now beat him squarely in the face without the least shame, in derision at his helpless plight. As he crossed one little glade a white hare ran out, sat up on its hind legs, waved its long, black-tipped ears, and began to wash its face, making the rudest grimaces at Makar. It gave him to understand that it[20] knew him well, knew him to be the same Makar who had devised cunning means of destruction for it in the forest; but now it was its turn to jeer.

Makar felt bitterly sad. The taiga grew more animated, but with a malign activity. Even the distant trees now threw their long branches across his way, snatched at his hair, and beat his face and eyes. The ptarmigans came out of their secret coverts and fixed their round, curious eyes upon him, and the wood-grouse ran in and out among them with drooping tails and angry, spreading wings, loudly telling their mates of him, Makar, and of his snares. Finally, a thousand fox-faces glanced from the distant thickets; they sniffed the air and looked derisively at him, pricking their sharp ears. Then the hares came and stood on their hind legs before him and shouted with laughter as they told of Makar’s misfortune.

That was too much.

“I shall die!” thought Makar, and he decided to do so as quickly as possible.

He lay down on the snow.

The cold increased. The last rays of the Aurora flickered faintly and stretched across the sky to peep at Makar through the tree-tops. The last echoes of the church bells came floating to him from far-away Chalgan.

The Northern Lights flared up and went out. The bells ceased ringing.

He did not notice how this came to pass. He knew that something should come out of him, and waited, thinking every moment it would come, but nothing appeared.

Nevertheless, he realised that he was now dead, and he therefore lay very still; he lay so long that he grew tired.

The night was dark when Makar felt someone push him with his foot. He turned his head and opened his eyes.

The larches were now standing meekly and quietly over him, as if ashamed of their former pranks. The shaggy spruces stretched out their long snow-covered arms and rocked themselves gently, gently, and the starry snowflakes settled softly through the air.

The kind, bright stars looked down through the branches from the dark blue sky, and seemed to be saying: “See, a poor man has died!”

Over Makar’s prostrate form and prodding him with his foot stood the old priest Ivan. His long cassock was white with snow; snow lay upon his fur hat, his shoulders, and his beard. Most surprising of all was the fact that this was the same Father Ivan who had died five years ago.

He had been a good priest. He had never pressed Makar for his tithes and had not even asked to be paid for the services of the church; Makar had always[22] fixed the price of his own christenings and requiems, and he now remembered with confusion that it had sometimes been extremely low and that sometimes he had not even paid it at all. Father Ivan had never resented this, he had only required one thing: a bottle of vodka on every occasion. If Makar had no money, Father Ivan would send him for the bottle himself, and they would drink it together. The good priest always grew as drunk as a lord, but he fought neither fiercely nor often. Makar would see him home, and hand him over, helpless and defenseless, to the care of the Mother Priestess, his wife.

Yes, he had been a good priest, but his end had been bad.

One day, when there was no one else at home, the fuddled Father, who was lying alone on the bed, had taken it into his head to smoke. He got up and staggered toward the great, fiercely heated fireplace to light his pipe at the blaze. But he was too drunk, he swayed and fell into the fire. When his family returned, all that remained of the little Father were his feet.

Every one regretted good Father Ivan, but no doctor on earth could have saved him, as only his feet remained. So they buried the feet, and a new priest was appointed to fill the place of Father Ivan.

And now Ivan himself, sound and whole, was standing over Makar, prodding him with his foot.

[23]“Get up, Makar, old man!” he was saying, “and let us be going.”

“Where must I go?” asked Makar with displeasure. He supposed that once dead he ought to lie still, and that there was no need for him now to be wandering about the forest, losing his way. If he had to do that, then why had he died?

“Let us go to the great Toyon.”[C]

“Why should I go to him?” Makar asked.

“He is going to judge you,” answered the priest in a sorrowful, compassionate voice.

Makar recollected that, in fact, one did have to appear at some judgment after one died. He had heard that at church. The priest was right after all; he would have to get up.

So Makar rose, muttering under his breath that they couldn’t even let a man alone after he was dead.

The priest walked before and Makar followed. They went always straight ahead, and the larches stood meekly aside and allowed them to pass; they were going eastward.

Makar noted with surprise that Father Ivan left no tracks in the snow behind him; he looked under his own feet and saw no tracks either; the snow lay as fresh and smooth as a table cloth.

How easy it would be now, he reflected, to rob other men’s traps, as no one could find him out! But the priest must have read his secret thought, for he[24] turned and said: “Kabis! (stop that!). You don’t know what you will get for thoughts like that.”

“Well, I declare!” exclaimed the disgusted Makar. “Can’t I even think what I please? What makes you so strict these days? Hold your tongue!”

The priest shook his head and walked on.

“Have we far to go?” asked Makar.

“Yes, a long way,” answered the priest sadly.

“And what shall we have to eat?” Makar inquired with anxiety.

“You have forgotten that you are dead,” the priest answered turning toward him. “You won’t have to eat or drink now.”

Makar did not like that idea in the least. Of course it would be all right in case there were nothing to eat, but then one ought to lie still, as he did at first after his death. But to walk, and to walk a long way, and to eat nothing, that seemed to him to be absolutely outrageous. He began muttering again.

“Don’t grumble!”

“All right!” he answered in an injured voice and went on complaining and growling to himself about such a stupid arrangement.

“They make a man walk and yet he needn’t eat! Who ever heard of such a thing?”

He was extremely discontented as he followed the priest. And they walked a long way. Though Makar could not see the dawn, they seemed, by the[25] distance they had covered, to have been walking a week. They had left so many ravines and hills behind them, so many rivers and lakes, so many forests and plains! Whenever Makar looked back, the dark taiga seemed to be running away behind them and the high, snowclad mountains seemed to be melting into the murky night and hiding swiftly behind the horizon.

They appeared to be climbing higher and higher. The stars grew larger and brighter; from the crest of the height to which they had risen they could see the rim of the setting moon. It seemed to have been in haste to escape, but Makar and the priest had overtaken it. Then it rose again over the horizon, and the travellers found themselves on a level, very high plain. It was light now, much lighter than early in the night, and this was due, of course, to the fact that they were much nearer the stars than they had been before. Each one of these, in size like an apple, glittered with ineffable brightness; the moon, as large as a huge barrel-head, blazed with the brilliance of the sun, lighting up the vast expanse from one edge to the other.

Every snowflake on the plain was sharply discernible, and countless paths stretched across it, all converging toward the same point in the east. Men of various aspects and in many different garbs were walking and riding along these roads.

[26]Makar looked sharply at one horseman, and then suddenly turned off the road and pursued him.

“Stop! Stop!” cried the priest, but Makar did not even hear him. He had recognised a Tartar, an old acquaintance of his, who had stolen a piebald horse from him once, and who had died five years ago. There was that same Tartar now, riding along on the very same horse! The animal was skimming over the ground, clouds of snowy dust were rising from under its hoofs, glittering with the rainbow colours of twinkling stars. Makar was surprised that he should be able, on foot, to overtake the Tartar so easily in his mad gallop. Besides, when he perceived Makar a few steps behind him, he stopped with great readiness. Makar fell upon him with passion.

“Come to the sheriff with me!” he cried. “That is my horse; he has a split in his right ear. Look at the man, how smart he is, riding along on a stolen horse while the owner follows on foot like a beggar!”

“Gently,” said the Tartar. “No need to go for the sheriff! You say this is your horse, take him and be damned to the brute! This is the fifth year I have been riding him up and down on one and the same spot! Every foot-passenger overtakes me. It is humiliating for a good Tartar, it is indeed!”

He threw his leg over the saddle in act to alight, but at that moment the panting priest came running up and seized Makar by the arm.

“Unfortunate man!” he cried. “What are you[27] about? Can’t you see that the Tartar is fooling you?”

“Of course he is fooling me!” shouted Makar waving his arms. “That was a lovely horse, a real gentleman’s horse; I was offered forty roubles for him before his third spring. Never you mind, brother! If you have spoilt that horse for me I shall cut him up for meat, and you shall pay me his full value in money! Do you think, because you are a Tartar, there are no laws for you?”

Makar was flying into a passion and shouting in order to draw a crowd about him, for he was afraid of Tartars from habit, but the priest broke in on his outburst.

“Gently, gently, Makar, you keep forgetting that you are dead! What do you want with a horse? Can’t you see that you travel much faster on foot than the Tartar does on horseback? Would you like to be forced to ride for a whole thousand years?”

Makar now understood why the Tartar had been so willing to give up his horse.

“They’re a crooked lot!” he thought, and he turned to the Tartar.

“Very well then,” he said. “Take the horse, brother; I forgive you!”

The Tartar angrily pulled his fur cap over his ears and lashed his horse. The pony galloped madly, and clouds of snow flew from under its hoofs,[28] but long as Makar and the priest stood still, the Tartar did not budge an inch from their side.

He spat angrily and turned to Makar.

“Listen, friend, haven’t you a bit of mahorka with you? I do want to smoke so badly, and I finished all mine five years ago.”

“You’re a friend of dogs but no friend of mine,” retorted Makar in a rage. “You have stolen my horse and now you ask for mahorka! Confound you altogether, I’m not sorry for you one bit!”

With these words Makar moved on.

“You made a mistake not to give him a little mahorka,” said Father Ivan. “The Toyon would have forgiven you at least one hundred sins for that at the Judgment.”

“Then why didn’t you tell me that before?” snapped Makar.

“Ah, it is too late to teach you anything now. You should have learnt it from your priest while you were alive.”

Makar was furious. He saw no sense in priests who took their tithes and did not even teach a man when to give a leaf of mahorka to a Tartar in order to gain forgiveness for his sins. One hundred sins were no joke! And all for a leaf of tobacco! The mistake had cost him dear.

“Wait a moment!” he exclaimed. “One leaf will do very well for us two. Let me give the other four[29] to the Tartar this minute, that will mean four hundred sins!”

“Look behind you,” answered the priest.

Makar looked round. The white, empty plain lay stretched out far behind them; the Tartar appeared for a second upon it, a tiny, distant dot. Makar thought he could distinguish the white cloud rising from under the hoofs of his piebald, but next moment the dot, too, had vanished.

“Well, well, the Tartar will manage all right without his mahorka. You see how he has ruined my horse, the scoundrel!”

“No, he has not ruined your horse,” answered the priest. “That horse was stolen. Have you not heard the old men say that a stolen horse will never go far?”

Makar had certainly heard this from the old men, but as he had often seen Tartars ride all the way to the city on horses that they had stolen, he had never put much belief in the saying. He now concluded that old men were sometimes right.

They now began to pass many other horsemen on the plain. All were hurrying along as fast as the first; the horses were flying like birds, the riders dripping with sweat, yet Makar and the priest kept overtaking them and leaving them behind.

Most of these horsemen were Tartars, but a few were natives of Chalgan; some of the latter were[30] astride stolen oxen and were goading them on with lumps of ice.

Makar looked with hatred at the Tartars, and muttered every time he passed one that the fellow had deserved much worse than this, but when he met a peasant from Chalgan he would stop and chat amicably with him, as they were friends, after all, even if they were thieves! Sometimes he would even show his fellow-feeling by picking up a lump of ice and diligently beating the ox or horse from behind, but let him take so much as one step forward himself, and horse and rider would be left far in the rear, a scarcely visible dot.

The plain seemed to be boundless. Though Makar and his companion occasionally overtook these riders and pedestrians, the country around was deserted, and the travellers seemed to be separated by hundreds of thousands of miles.

Among others, Makar fell in with an old man unknown to him, who plainly hailed from Chalgan; this could be discerned from his face, his clothes, and even from his walk, but Makar could not remember ever having seen him before. The old man wore a ragged fur coat, a great shaggy hat, tattered and worn leather breeches, and still older calf-skin boots. Worst of all, he was carrying on his shoulders, in spite of his old age, a crone still more ancient than himself, whose feet trailed on the ground. The old man was wheezing and staggering along,[31] leaning heavily on his stick. Makar felt sorry for him. He stopped and the old man stopped too.

“Kansi! (Speak!)” said Makar pleasantly.

“No,” answered the greybeard.

“What have you seen?”

“Nothing.”

“What have you heard?”

“Nothing.”

Makar was silent for a while, and then thought he might ask the old man who he was and whence he had crawled.

The old man told his name. Long since, he said—he did not know himself how many years ago—he had left Chalgan and gone up to the “mountain” to save himself. There he had done no work, had lived on roots and berries, and had neither ploughed nor sowed nor ground wheat nor paid taxes. When he died he went to the Judgment of the Toyon. The Toyon asked him who he was, and what he had done. He answered he had gone up on the “mountain” and had saved himself. “Very well,” the Toyon answered, “but where is your wife? Go and fetch her here.” So he went back for his old woman. But she had been forced to beg before she died, as there had been no one to support her, and she had had neither house, nor cow, nor bread. Her strength had failed, and now finally she was not able to move her legs. So he was obliged to carry her to the Toyon on his back.

[32]As he said this, the old man burst into tears, but the old woman kicked him with her heels as if he had been an ox, and cried in a weak, cross voice:

“Go on!”

Makar felt more sorry than ever for the old man, and heartily thanked his stars that he had not succeeded in going to the “mountain” himself. His wife was large and lusty, and his burden would have been even heavier than that of the old man; if, in addition to this, she had begun to kick him as if he were an ox, he would certainly have died a second death.

He tried to hold the old woman’s feet out of pity for his friend, but he had scarcely taken three steps before he was forced to drop them hastily, or they would certainly have remained in his hands; another minute, and the old man and his burden were left far out of sight.

For the remainder of his journey Makar met no more travellers whom he honoured with marked attention. Here were thieves crawling along step by step, laden like beasts of burden with stolen goods; here rode fat Yakut chieftains towering in their high saddles, their peaked hats brushing the clouds; here, skipping beside them, ran poor workmen, as lean and light as hares; here strode a gloomy murderer, blood-drenched, with haggard, furtive eyes. He kept casting himself in vain into the pure snow, hoping to wash out the crimson stains;[33] the snow around him was instantly dyed red, but the blood upon the murderer started out more vividly than ever, and in his eyes there gleamed wild horror and despair. So he ran on, shunning the frightened gaze of all men.

From time to time the little souls of children came flying through the air like birds, winging their way in great flocks, and this was no surprise to Makar. Bad, coarse food, dirt, the heat from the fireplaces, and the cold draughts in the huts drove them from Chalgan alone in hundreds. As they overtook the murderer, the startled flocks wheeled swiftly aside, and long after their passage the air was filled with the quick, anxious whirring of their little pinions.

Makar could not help remarking that, in comparison with the other travellers, he was moving at a fairly swift pace, and he hastened to ascribe this to his own virtue.

“Listen Asabit! (Father!)” he said. “What do you think, even if I was fond of drinking I was a good man, wasn’t I? God loves me, doesn’t he?”

He looked inquiringly at Father Ivan. He had a secret motive for asking this question, he wanted to find out something from the old priest, but the latter answered curtly:

“Don’t be conceited! We are near the end now. You will soon find that out for yourself.”

Makar had not noticed until then that a light seemed to be breaking over the plain. First a few[34] lambent rays flashed up over the horizon, spreading swiftly across the sky and extinguishing the bright stars. They went out, the moon set, and the plain lay in darkness.

Then mists arose on the plain and stood round about it like a guard of honour.

And at a certain point in the east the mists grew bright like a legion of warriors in golden armour.

And then the mists stirred, and the warriors prostrated themselves upon the ground.

And the sun rose from their midst, and rested upon their golden ranks, and looked across the plain.

And the whole plain shone with a wonderful, dazzling radiance.

And the mists rose triumphantly in a mighty host, parted in the south, swayed, and swept upwards.

And Makar seemed to hear a most enchanting melody, the immemorial pæan with which the earth daily greets the rising sun. He had never before given it due attention, and only now felt for the first time the beauty of the song.

He stood and hearkened and would not go any farther; he wanted to stand there forever and listen.

But Father Ivan touched him on the arm.

“We have arrived,” he said. “Let us go in.”

Thereupon Makar noticed that they were standing before a large door which had previously been hidden by the mist.

[35]He was very loath to proceed, but could not fail to comply.

They entered a large and spacious hut, and not until then did Makar reflect that it had been very cold outside. In the middle of the hut was a chimney of pure silver marvellously engraved, and in it blazed logs of gold, radiating such an even heat that one’s whole body was penetrated by it in an instant. The flames in this beautiful fireplace neither scorched nor dazzled the eyes, they only warmed, and once more Makar wanted to stand there and toast himself forever. Father Ivan, too, came and stood before the fire, stretching out his frozen hands to the blaze.

Four doors opened out of the room, and of these only one led into the open air; through the other three young men in long white gowns were coming and going. Makar imagined that they must be the servants of this Toyon. He seemed to remember having seen them somewhere before, but could not recollect exactly where. He was not a little surprised to note that each servant wore a pair of large white wings upon his back, and decided that the Toyon must have other workmen beside these, for surely they, encumbered with their wings, could never make their way through the forest thickets when they went to cut wood or poles.

One of the servants approached the fire, and, turning his back to the blaze, addressed Father Ivan.

“There is nought to say.”

“What did you hear in the world?”

“Nothing.”

“What did you see?”

“Nothing.”

Both were silent, and then the priest said:

“I have brought this one.”

“Is he from Chalgan?” asked the servant.

“Yes, from Chalgan.”

“Then we must get ready the big scales.”

He left the room to make his preparations, and Makar asked the priest why scales were needed, and why they must be large.

“You see,” answered the priest a trifle embarrassed, “the scales are needed to weigh the good and evil you did when you were alive. With all other people the good and evil almost balance one another, but the inhabitants of Chalgan bring so many sins with them that the Toyon had to have special scales made with one of the bowls extra large in order to contain them all.”

At these words Makar quailed, and felt his heart-strings tighten.

The servant brought in and set up the big scales. One bowl was small and of gold, the other was wooden and of huge proportions. A deep black pit suddenly opened under the wooden bowl.

Makar approached the scales, and carefully inspected[37] them to make sure they were not false. They proved to be correct; the bowls hung motionless, without movement up or down.

To tell the truth, he did not exactly understand their mechanism, and would have preferred to have done business with the simple balances by whose aid he had learned to buy and sell with great profit to himself during the course of his long life.

“The Toyon is coming!” cried Father Ivan suddenly, and hastily began to pull his cassock straight.

The central door opened and in came an ancient, venerable Toyon, his long silvery beard hanging below his waist. He was dressed in rich furs and tissues unknown to Makar, and on his feet he wore warm velvet-lined boots, such as Makar had seen depicted on antique ikons.

Makar recognised him at a glance as the same old greybeard whose picture he had seen in church, only here he was unattended by his son. Makar decided that the latter must have gone out on business. The dove flew into the room, however, and after circling about the old man’s head, settled upon his knee. The old Toyon stroked the dove with his hand as he sat on the seat that had been especially prepared for him.

The Toyon’s face was kind, and when Makar became too downcast he looked at it and felt better.

His heart was heavy because he was suddenly remembering all his past life down to the smallest[38] detail; he remembered every step he had taken, every blow of his axe, every tree he had felled, every deceit he had practiced, every glass of vodka he had drunk.

He grew frightened and ashamed, but he took heart as he looked at the face of the old Toyon.

And as he took heart it occurred to him that there might be some things he could manage to conceal.

The old Toyon looked searchingly at him and asked him who he was and whence he had come, what his name was and what his age might be.

When Makar had replied to his questions, the old Toyon asked:

“What have you done in your life?”

“You know that yourself,” answered Makar. “Surely it is written in your book!”

Makar wanted to test the Toyon and find out whether everything was really inscribed there or no.

“Tell me yourself,” answered the old Toyon.

Makar took courage.

He began enumerating all his works, and although he remembered every blow he had struck with his axe, every pole he had cut, and every furrow he had ploughed, he added to his reckoning thousands of poles and hundreds of loads of wood and hundreds of logs and hundreds of pounds of sown seed.

[39]When all had been told, the old Toyon turned to Father Ivan and said:

“Bring hither the book.”

Makar saw from this that Father Ivan was secretary to the Toyon, and was annoyed that the other had given him no friendly hint of the fact.

Father Ivan brought the great book, opened it, and began to read.

“Just look and see how many poles are inscribed there,” said the old Toyon.

Father Ivan looked and answered sorrowfully:

“He added a round three thousand to his reckoning.”

“It’s a lie!” shouted Makar vehemently. “He must be wrong because he was a drunkard and died a wicked death!”

“Be quiet!” commanded the Toyon. “Did he charge you more than was fair for christenings and weddings? Did he ever press you for tithes?”

“Why waste words?” answered Makar.

“You see,” the Toyon said, “I know without assistance from you that he was fond of drink——”

And the old Toyon lost his temper. “Read his sins from the book now; he is a cheat, and I can’t believe his words!” he cried to Father Ivan.

Meanwhile the servants were heaping into the golden bowl all Makar’s poles, and his wood, and his ploughing, and all his work. And there proved to be so much that the golden bowl sank, and the[40] wooden bowl rose out of reach, high, high into the air. So the young servants of God flew up to it on their pinions and hundreds of them pulled it to the floor with ropes.

Heavy is the labour of a native of Chalgan!

Then Father Ivan began adding up the number of frauds that Makar had committed, and there proved to be twenty-one thousand, three hundred and three. Then he added up the number of bottles of vodka he had drunk, and there proved to be four hundred. And the priest read on and Makar saw that the wooden bowl was pulling on the gold one; it sank into the hole, and, as the priest read, it descended ever deeper and deeper.

Makar realised then that things were going badly for him; he stepped up to the scales and furtively tried to block them with his foot.

But one of the servants saw it, and a clamour arose amongst them.

“What is the matter there?” asked the old Toyon.

“Why, he was trying to block the scales with his foot!” cried the servant.

At that the Toyon turned wrathfully to Makar, exclaiming:

“I see that you are a cheat, a sluggard, and a drunkard. You have left your arrears unpaid behind you, you owe tithes to the priest, and the policeman is steadily sinning on your account by swearing every time he speaks your name.”

[41]Then, turning to Father Ivan, the old Toyon asked:

“Who in Chalgan gives the heaviest loads to his horses to pull, and who works them the hardest?”

Father Ivan answered:

“The church warden. He carries the mail and drives the district policeman.”

To that the Toyon answered:

“Hand over this sluggard to the church warden for a horse and let him pull the policeman until he drops—we shall see what will happen next.”

Just as the Toyon was saying these words, the door opened; his son entered the hut and sat down at his right hand.

And the son said:

“I have heard the sentence pronounced by you. I have lived long on the earth, and I know the ways of the world. It will be hard for the poor man to take the place of the district policeman’s horse. However, so be it, only mayhap he still has something to say: speak baraksan! (poor fellow!)”

Then there happened a strange thing. Makar, the Makar who had never before in his life uttered more than ten words at a time, suddenly felt himself possessed of the gift of eloquence. He began speaking, and wondered at himself. There seemed to be two Makars, the one talking, the other listening and marvelling. He could scarcely believe his ears. His discourse flowed from his lips with fluency and passion;[42] the words pursued one another swiftly, and ranged themselves in long and graceful rows. He did not hesitate. If by any chance he became confused, he corrected himself and shouted twice louder than before. But above all he felt that his words were carrying conviction.

The ancient Toyon, who had at first been a little annoyed by his boldness, began listening with rapt attention, as if he were being persuaded that Makar was not the fool that he seemed to be. Father Ivan had been frightened for an instant and had plucked Makar by the coat-tails, but Makar had pushed him aside and continued his speech. The fears of the old priest were quickly allayed; he even beamed at Makar as he heard his old parishioner boldly declaring the truth, and saw that that truth was pleasing to the heart of the ancient Toyon. Even the young servants of the Toyon with their long gowns and their white wings came out of their quarters and stood in the doorways listening with wonder to Makar’s words, nudging one another with their elbows.

Makar commenced his plea by saying that he did not want to take the place of the church warden’s horse. Not because he was afraid of hard work, but because the sentence was unjust. And because the sentence was unjust, he would not submit to it; he would not do a stroke of work nor move one single foot. Let them do what they would with him! Let[43] them hand him over to the devils forever, he would not haul the policeman, because to condemn him to do so was an injustice. And let them not imagine that he was afraid of being a horse. Although the church warden drove his horse hard, he fed him with oats, but he, Makar, had been goaded all his life, and no one had ever fed him.

“Who has goaded you?” asked the Toyon.

Yes, all his life long he had been goaded. The bailiff had goaded him; the tax assessor and the policeman had goaded him, demanding taxes and tallage; hunger and want had goaded him; cold and heat, rain and drought had goaded him; the frozen earth and the ruthless forest had goaded him. The horse had trudged on with its eyes on the ground, ignorant of its journey’s end; so had he trudged through life. Had he known the meaning of what the priest read in church or for what his tithes were demanded? Had he known why his eldest son had been taken away as a soldier and whither he had gone? Had he known where he had died and where his poor bones had been laid?

He had drunk, it was charged, too much vodka; so he had, for his heart had craved it.

“How many bottles did you say that he drank?” the Toyon asked.

“Four hundred,” answered Father Ivan, with a glance at the book.

That might be so, pleaded Makar, but was it[44] really all vodka? Three quarters of it was water; only one quarter was vodka, and that was stiffened with vile mahorka. Three hundred bottles might well be deducted from his account.

“Is what he says true?” asked the ancient Toyon of Father Ivan, and it was plain that his anger was not yet appeased.

“Absolutely true,” the priest answered quickly, and Makar continued his tale.

It was true that he had added three thousand poles to his account, but what if he had? What if he had only cut sixteen thousand? Was that so small a number? Besides, while he had cut two thousand his first wife had been ill. His heart had been aching, he had longed to sit by her bedside, but want had driven him into the forest, and in the forest he had wept, and the tears had frozen on his eye-lashes, and because of his grief, the cold had struck into his very heart, and still he had chopped.

And then his old woman had died. He had to bury her, but he had no money to pay for the burial. So he had hired himself out to chop wood to pay for his wife’s abode in the world beyond. The merchant had seen how great was his need, and had only paid him ten kopecks—and his old woman had lain all alone in the icy hut while he had once more chopped wood and wept. Surely each one of those loads should be counted as four or even more!

Tears rose in the eyes of the old Toyon, and Makar[45] saw the scales trembling and the wooden bowl rising as the golden one sank.

And still he talked on.

Everything was written down in their book, he said, let them look and see if any one had ever done him a kindness or brought him happiness and joy! Where were his children? If they had died his heart had been heavy and sad; if they had lived to grow up they had left him, to carry on their fight alone with their own grinding needs. So he had remained to grow old with his second wife, and had felt his strength failing and had seen that a pitiless, homeless old age was creeping upon him. They two had stood solitary as two lorn fir-trees on the steppe, buffeted on every hand by the merciless winds.

“Is that true?” asked the Toyon again, and the priest hastened to answer:

“Absolutely true.”

And the scales trembled once more—but the old Toyon pondered.

“How is this?” he asked. “Have I not many on earth who are truly righteous? Their eyes are clear, their faces are bright, and their garments are without a stain. Their hearts are mellow as well tilled soil in which flourishes good seed, sending up strong and fragrant shoots whose odour is pleasant to my nostrils. But you—look at yourself!”

All eyes were now turned on Makar, and he felt ashamed. He knew that his eyes were dim, that his[46] face was dull, that his hair and beard were unkempt, that his raiment was torn. And though for some time before his death he had intended to buy a pair of new boots in which to appear at the Judgment, he somehow had always managed to drink up the money, and now stood before the Toyon in wretched fur shoes like a Yakut.

“Your face is dull,” the Toyon went on. “Your eyes are bleared and your clothes are torn. Your heart is choked with weeds and thistles and bitter wormwood. That is why I love my righteous and turn my face from the ungodly such as you.”

Makar’s heart contracted and he blushed for his own existence. He hung his head for a moment and then suddenly raised it and took up his tale once more.

Which righteous men did the Toyon mean? he asked. If he meant those that lived on earth in rich houses at the same time that Makar was there, then he knew all about them! Their eyes were clear because they had not shed the tears he had shed; their faces were bright because they were bathed in perfume, and their spotless garments were sewn by other hands than their own.

Again Makar hung his head, and again raised it.

And did not the Toyon know that he too had come into the world as they had with clear, candid eyes in which heaven and earth lay reflected? That he had been born with a pure heart, ready to expand to[47] all the beauty of the world? Whose fault was it if he now longed to hide his besmirched and dishonoured head under the ground? He could not say. But this he did know, that the patience of his soul was exhausted!

Of course Makar would have been calmer could he have seen the effect that his speech was having on the Toyon, or how each of his wrathful words fell into the golden bowl like a plummet of lead. But he saw nothing of this because his heart was overwhelmed with blind despair.

He had gone over again the whole of his bitter existence. How had he managed to bear the terrible burden until now? He had borne it because the star of hope had still beckoned him onward, shining like a watch-fire through mists of toil and doubt. He was alive, therefore he might, he would, know a happier fate. But now he stood at the end, and the star had gone out.

Darkness fell on his soul, and rage broke over it as a tempest breaks over the steppe in the night. He forgot who he was and before whose face he stood; he forgot all but his wrath.

But the old Toyon said to him:

“Wait a moment, baraksan! You are not on earth. There is justice here for you, also.”

At that Makar trembled. The idea that some one pitied him dawned upon his mind and filled and softened[48] his heart, but because his whole miserable existence now lay exposed before him from his first day to his last, unbearable self-pity overwhelmed him and he burst into tears.

And the ancient Toyon wept with him. And old Father Ivan wept, and the young servants of God shed tears and wiped them away with their wide sleeves.

And the scales wavered, and the wooden bowl rose ever higher and higher!

A LEGEND OF THE POLYESIE[D]

The forest was murmuring.

There was always a murmuring in this forest, long-drawn, monotonous, like the undertones of a distant bell, like a faint song without words, like vague memories of the past. There was always a murmuring in the forest because it was a dense wood of ancient pines, untouched as yet by the axe and saw of the timber merchant. The tall, century-old trees with their mighty red-brown trunks stood in frowning ranks, proudly thrusting their green, interwoven tops aloft. The air under them was still and sweet with resin; bright ferns pierced the carpet of needles with which the ground was clothed, and superbly displayed their motionless, fringed foliage. Tall, green grass-blades had shot upward in the moist places, and there, too, white clover-heads drooped heavily, as if overcome with gentle languor. And always overhead, without a pause and without an end, droned the voice of the forest, the low sighing of the ancient pines.

[52]But now these sighs had grown deeper and louder. I was riding along a woodland path, and although the sky was invisible, I knew, under the darkly frowning trees, that a storm was gathering overhead. The hour was late. A few last rays of sunlight were still filtering in here and there between the tree-trunks, but misty shadows had already begun to gather in the thickets. A thunder-storm was brewing for the night. I was forced to abandon all idea of continuing the chase that day, and could only think of reaching a night’s lodging before the storm broke. My horse struck his hoof against a bare root, snorted, and pricked his ears, harkening to the muffled impacts of the forest echo. Then of his own accord he turned his steps into the well-known path that led to the hut of the forest guard.

A dog barked. White plastered walls gleamed among the thinning tree-trunks, a blue wisp of smoke appeared, curling upward under the overshadowing branches, and a lop-sided cottage with a dilapidated roof stood before me, sheltering under a wall of ruddy tree-trunks. It seemed to have sunk down upon the ground, while the proud graceful pines nodded their heads, high, high above it. In the centre of the clearing stood two oak trees, huddling close to one another.

Here lived the foresters Zakhar and Maksim, the invariable companions of my hunting expeditions. But now they were evidently away from home, for[53] no one came out of the house at the barking of the great collie. Only their old grandfather with his bald head and his grey whiskers was sitting on a bench outside the door, braiding shoes of bast. The old man’s beard swept almost to his belt; his eyes were vague as if he were trying in vain to remember something.

“Good evening, daddy! Is any one at home?”

“Eh, hey,” mumbled the old man, shaking his head; “neither Zakhar nor Maksim is here and Motria has gone into the wood for the cow. The cow has run away; perhaps the bears have eaten her. And so there is no one in the cottage.”

“Well, well, never mind. I’ll sit here with you and wait.”

“Yes, sit down and wait!” the old man nodded, and watched me with dim, watery eyes as I tied my horse to the branch of one of the oaks. The old man was failing fast. He was nearly blind and his hands trembled.

“And who are you, lad?” he asked, as I sat down on the bench.

I was accustomed to hearing this question at every visit.

“Eh, hey; now I know, now I know,” said the old man, resuming his work on the shoe. “My old head is like a sieve; nothing stays in it now. I remember people who died a long time ago, oh, I remember them[54] well! But I forget new people. I have lived in this world a long time.”

“Have you lived in this forest long, daddy?”

“Eh, hey; a long time! When the Frenchmen came into the Tsar’s country I was here.”

“You have seen much in your day. You must have many stories to tell.”

The old man looked at me with surprise.

“And what would I have seen, lad? I have seen the forest. The forest murmurs night and day, winter and summer. One hundred years have I lived in this forest like that tree there without heeding the passage of time. And now I must go to my grave, and sometimes I can’t tell, myself, whether I have lived in this world or not. Eh, hey; yes, yes. Perhaps, after all, I have not lived at all.”

A corner of the dark cloud moved out over the clearing from behind the close-growing tree-tops, and the pines that stood about the clearing rocked in the first gusts of wind. The murmur of the forest swelled into a great resonant chord. The old man raised his head and listened.

“A storm is coming,” he said after a pause. “I know. Oi, oi! A storm will howl to-night, and will break the pines and tear them up by the roots. The Master of the forest will come out.”

“How do you know that, daddy?”

“Eh, hey; I know it! I know what the trees are saying. Trees know what fear is as well as we do.[55] There’s the aspen, a worthless tree that’s always getting broken to pieces. It trembles even when there is no wind. The pines in the forest sing and play, but if the wind rises ever so little they raise their voices and groan. This is nothing yet. There, listen to that! Although my eyes see badly, my ears can hear: that was an oak tree rustling. The oaks have been touched in the clearing. The storm is coming.”

And, as a matter of fact, the pair of low, gnarled oak trees that stood in the centre of the clearing, protected by the high wall of the forest, now waved their strong branches and gave forth a muffled rustling easily distinguishable from the clear, resonant notes of the pines.

“Eh, hey; do you hear that, lad?” asked the old man with a childishly cunning smile. “When the oak trees mutter like that, it means that the Master is coming out at night to break them. But no, he won’t break them! The oak is a strong tree, too strong even for the Master. Yes indeed!”

“What Master, daddy? You say yourself it is the storm that breaks them.”

The old man nodded his head with a crafty look.

“Eh, hey; I know that! They tell me there are some people in the world these days who don’t believe in anything. Yes indeed! But I have seen him as plainly as I see you now, and better, because my eyes are old now, and they were young then. Oi, oi! How well I could see when I was young!”

[56]“When did you see him, daddy? Tell me, do!”

“It was an evening just like this. The pines began to groan in the forest. First they sang and then they groaned: oh-ah-o-oh-a-h! And then they stopped, and then they began again louder and more pitifully than ever. Eh, hey; they groaned because they knew that the Master would throw down many of them that night! And then the oak trees began to talk. And toward evening things grew worse until he came whirling along with the night. He ran through the forest laughing and crying, dancing and spinning, and always swooping down on those oak trees and trying to tear them up by the roots. And once in the Autumn I looked out of the window, and he didn’t like that. He came rushing up to the window and, bang-bang, he broke it with a pine knot. He nearly hit my face, bad luck to him! But I’m no fool. I jumped back. Eh, hey; lad, that’s the sort of a quarrelsome fellow he is!”

“But what does he look like?”

“He looks exactly like an old willow tree in a marsh. Just exactly! His hair is like dry mistletoe on a tree, and his beard too; but his nose is like a big fat pine knot and his mouth is as twisted as if it were all overgrown with lichen. Bah, how ugly he is! God pity any Christian that looks like him! Yes indeed! I saw him once quite close, in a swamp. If you’ll come here in the winter you can see him for yourself. You must go in that direction, up that[57] hill—it is covered with woods—and climb to the very top of the highest tree. He can sometimes be seen from there racing along over the tree-tops, carrying a white staff in his hand, and whirling, whirling until he whirls down the hill into the valley. Then he runs away and disappears into the forest. Eh, hey! And wherever he steps he leaves a foot-print of white snow. If you don’t believe an old man come and see for yourself.”

The old man babbled on; the excited, anxious voices of the forest and the impending storm seemed to have set his old blood racing. The aged gaffer laughed and blinked his faded eyes.

But suddenly a shadow flitted across his high, wrinkled forehead. He nudged me with his elbow and said with a mysterious look:

“Let me tell you something, lad. Of course the Master of the forest is a worthless, good-for-nothing creature, that is true. It disgusts a Christian to see an ugly face like his, but let me tell you the truth about him: he never does any one any harm. He plays jokes on people, of course, but as for hurting them, he never would do that!”

“But you said yourself, daddy, that he tried to hit you with a pine knot.”

“Eh, hey; he tried to! But he was angry then because I was looking at him through the window; yes indeed! But if you don’t go poking your nose into his affairs he’ll never play you a dirty trick.[58] That’s what he’s like. Worse things have been done by men than by him in this forest. Eh, hey; they have indeed!”

The old man’s head dropped forward on to his breast and he sat silent for several minutes. Then he looked at me, and a ray of awakening memory seemed to gleam through the film that fogged his eyes.

“I’ll tell you an old story of our forest, lad. It happened here in this very place, a long, long time ago. Almost always I remember it as in a dream. But when the forest begins to talk more loudly, I remember it well. Shall I tell it to you?”

“Yes, do, daddy! Tell me!”

“Very well, I’ll tell you; eh, hey! Listen!”

My father and mother died, you know, a long time ago when I was only a little lad. They left me in the world alone. That’s what happened to me, eh, hey! Well, the village warden looked at me and thought: “What shall we do with this boy?” And the lord of the manor thought the same thing. And at that time Raman, the forest guard, came out of the forest, and he said to the warden: “Let me have that boy to take back to my cottage with me. I’ll take good care of him. It will be company[59] for me in the forest and he will be fed.” That’s what he said, and the warden answered: “Take him!” So he took me. And I have lived in the forest ever since.