Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The object of this book is to furnish practical directions for the preparation and presentation of oral and written arguments. Teachers of Argumentation and Debate have come to realize that interest can best be stimulated and practical results best secured by omitting the theoretical forms of reasoning at first, and leading the student directly to the actual work of building up an argument. The technical name of a logical process has little to do with its practical application. This fact is well illustrated by the constant use of arguments in our conversation: moreover, the student who enters upon this work is sufficiently advanced to appreciate the difference between truth and error. For these reasons the book is divided into two parts, the first of which deals with the Practice of Argumentation and Debate. After the student has had some experience in constructing and presenting arguments he is better fitted to make practical application of the theoretical principles of argumentation which are presented in the second part of this book under the head of the Theory of Argumentation and Debate. Those teachers who prefer to follow the old order of presentation can do so by taking up the Theory of Argumentation and Debate after completing the chapter on Collecting Evidence and before taking up the chapter on Constructing the Brief.

Since Argumentation and Debate has come to be a regular course of study in almost every college and university and in many of our larger preparatory and high schools, there has been a tendency among text-book writers to multiply rules regarding every phase of the subject. By consulting various viworks it will be found that no less than sixteen different rules have been formulated for the construction of the brief alone. One book contains as many as thirteen of these. To the average student the result is confusion rather than enlightenment. One of the objects of the author has been to remedy this condition of affairs by attempting to state clear-cut rules, which, though covering all contingencies, are limited to what is essential and practical. In regard to illustrations and examples the same idea has been carried out.

The order in which the subjects are discussed is that dictated by actual practice. The object has been to lead the student step by step, to point out all the difficulties along the way, and to show by precept and example how they may be overcome. After the essential definitions are given and the importance of the subject upon which he is entering is set forth, the student is shown where to find, and how to choose and express, a proposition for argument. He is then directed how to analyze that proposition for the purpose of finding out what he must do in order to establish its truth or falsity. Next, he is informed of the sources of evidence bearing upon the proposition, and how such evidence is to be collected and used. Directions for constructing a brief out of this evidence are then presented and the way in which the finished argument is to be developed is set forth. The psychological development of an argument is here for the first time given full consideration. Following this the student is shown how to defend his own argument and overthrow that of his opponent. Finally, instructions are given for delivering the argument in the most effective manner. Even without the aid of an instructor the student could follow the argumentative process through to the end.

The exercises given are intended to be practical and to assure a thorough working knowledge of the discussion. The material in the appendix may be used at the discretion of viithe instructor. The prevalence of references to the Lincoln-Douglas Debates is intentional and arises from the fact that the circumstances under which these debates occurred, the personalities of the participants, and the argumentative excellence of the discussions make them especially useful to the student.

The writer wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to all those who have heretofore written upon this subject as well as to the students whom it has been his pleasure to instruct. He wishes especially to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Raymond M. Alden, who gave a careful reading to the greater part of the manuscript and made many helpful suggestions.

| PART I | ||||||

| The Practice of Argumentation and Debate | ||||||

| CHAPTER I | ||||||

| DEFINITION AND IMPORTANCE OF ARGUMENTATION | ||||||

| Section | Page | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Definitions | 3 | ||||

| II. | The Object of Argumentation | 5 | ||||

| III. | Educational Importance of Argumentation | 6 | ||||

| IV. | Practical Importance of Argumentation | 7 | ||||

| CHAPTER II | ||||||

| THE PROPOSITION | ||||||

| I. | The Subject-Matter of the Proposition | 9 | ||||

| 1. | The subject must be interesting | 9 | ||||

| 2. | Subjects for first practice should be those of which the debater has a general knowledge | 11 | ||||

| 3. | The subject must be debatable | 12 | ||||

| II. | The Wording of the Proposition | 13 | ||||

| 1. | The proposition should be so narrowed as to embody only one central idea | 14 | ||||

| 2. | The proposition should be stated in the affirmative | 15 | ||||

| 3. | The proposition should contain no ambiguous words | 16 | ||||

| x | 4. | The proposition should be worded as simply and as briefly as is consistent with the foregoing requirements | 18 | |||

| CHAPTER III | ||||||

| ANALYZING THE PROPOSITION | ||||||

| I. | The Importance of Analysis | 21 | ||||

| II. | Essential Steps in Analysis | 22 | ||||

| 1. | A broad view of the subject | 22 | ||||

| 2. | The origin and history of the question | 23 | ||||

| 3. | Definition of terms | 24 | ||||

| 4. | Narrowing the question | 27 | ||||

| (1) | Excluding irrelevant matter | 27 | ||||

| (2) | Admitting matters not vital to the argument | 28 | ||||

| 5. | Contrasting the affirmative arguments with those of the negative | 29 | ||||

| III. | The Main Issues | 36 | ||||

| CHAPTER IV | ||||||

| EVIDENCE | ||||||

| I. | Sources of Evidence | 39 | ||||

| 1. | Personal knowledge | 39 | ||||

| 2. | Personal interviews | 40 | ||||

| 3. | Personal letters | 41 | ||||

| 4. | Current literature | 42 | ||||

| 5. | Standard literature | 45 | ||||

| 6. | Special documents | 46 | ||||

| (1) | Reports and pamphlets issued by organizations | 46 | ||||

| (2) | Reports and documents issued by the government | 48 | ||||

| xiII. | Recording Evidence | 51 | ||||

| 1. | Use small cards or sheets of paper of uniform size | 53 | ||||

| 2. | Place only one fact or point on each card | 53 | ||||

| 3. | Write only on one side of the card | 53 | ||||

| 4. | Express the idea to be put on the card in the simplest and most direct terms | 54 | ||||

| 5. | Make each card complete in itself | 54 | ||||

| 6. | In recording material for refutation put an exact statement of the argument to be refuted at the top of the card | 55 | ||||

| 7. | State the main issue or subject to which the evidence relates at the top of the card | 55 | ||||

| 8. | State the source from which the evidence is taken at the bottom of the card | 56 | ||||

| III. | Selecting Evidence | 58 | ||||

| 1. | The evidence must come from the most reliable source to which it can be traced | 58 | ||||

| 2. | A person quoted as authority must be unprejudiced, in full possession of the facts, and capable of giving expert testimony on the point at issue | 60 | ||||

| 3. | Evidence should be examined to determine whether there are attendant circumstances which will add to its weight | 62 | ||||

| 4. | The selection of evidence must be fair and reasonable | 64 | ||||

| 5. | The position and arguments of the opposition should be taken into consideration | 65 | ||||

| 6. | That evidence which will appeal most strongly to those to whom the argument is to be addressed should be selected | 66 | ||||

| IV. | The Amount of Evidence Required | 68 | ||||

| CHAPTER V | ||||||

| CONSTRUCTING THE BRIEF | ||||||

| I. | The Purpose of the Brief | 72 | ||||

| II. | Method of Constructing the Brief | 73 | ||||

| xiiIII. | Rules for Constructing the Brief | 76 | ||||

| 1. | A brief should be composed of three parts: Introduction, Proof, and Conclusion | 76 | ||||

| 2. | Each statement in a brief should be a single complete sentence | 77 | ||||

| 3. | The relation which the different statements in a brief bear to each other should be indicated by symbols and indentations | 77 | ||||

| 4. | The introduction should contain the main issues together with a brief statement of the process of analysis by which they were found | 79 | ||||

| 5. | The main statements in the proof should correspond to the main issues set forth in the introduction, and should read as reasons for the truth of the proposition | 84 | ||||

| 6. | Every statement in the proof must read as a reason for the statement to which it is subordinate | 85 | ||||

| 7. | Statements introducing refutation must state clearly the argument to be refuted | 87 | ||||

| 8. | The conclusion should be a summary of the main arguments just as they stand in the proof of the brief and should close with an affirmation or denial of the proposition in the exact words in which it is phrased | 89 | ||||

| Specimen student brief | 91 | |||||

| CHAPTER VI | ||||||

| CONSTRUCTING THE ARGUMENT | ||||||

| I. | Attention—Aroused by the Introduction | 95 | ||||

| 1. | Kinds of attention | 96 | ||||

| A. | Natural attention | 96 | ||||

| B. | Assumed attention | 97 | ||||

| 2. | Methods of securing proper attention | 98 | ||||

| A. | Immediate statement of purpose | 98 | ||||

| xiii | B. | Illustrative story | 100 | |||

| C. | Quotations | 101 | ||||

| II. | Interest—Maintained by the Proof | 102 | ||||

| 1. | Necessity | 103 | ||||

| 2. | Methods of maintaining interest | 103 | ||||

| A. | Appropriate treatment | 103 | ||||

| a. | Adaptation to speaker or writer | 103 | ||||

| b. | Adaptation to audience or reader | 103 | ||||

| c. | Adaptation to time or occasion | 106 | ||||

| B. | Logical structure | 106 | ||||

| C. | Style | 107 | ||||

| a. | Elements of style | 108 | ||||

| (1) | Vocabulary | 108 | ||||

| (2) | Sentences | 109 | ||||

| (3) | Paragraphs | 110 | ||||

| b. | Qualities of style | 110 | ||||

| (1) | Clearness | 110 | ||||

| (2) | Force | 117 | ||||

| (3) | Elegance | 120 | ||||

| III. | Desire—Created by the Conclusion | 121 | ||||

| 1. | Necessity | 121 | ||||

| 2. | Interest | 122 | ||||

| A. | Convenience | 122 | ||||

| B. | Pleasure | 123 | ||||

| C. | Profit | 123 | ||||

| 3. | Jealousy, vanity, and hatred | 124 | ||||

| 4. | Ambition | 124 | ||||

| 5. | Generosity | 125 | ||||

| 6. | Love of right and justice | 125 | ||||

| 7. | Love of country, home, and kindred | 125 | ||||

| CHAPTER VII | ||||||

| REBUTTAL | ||||||

| I. | Preparation for Rebuttal | 129 | ||||

| 1. | Sources of material for rebuttal | 129 | ||||

| xiv | A. | Material acquired in constructing the argument | 129 | |||

| B. | Books, papers, and documents | 131 | ||||

| C. | Questions | 133 | ||||

| 2. | Arrangement of rebuttal material | 139 | ||||

| A. | Classification of cards | 140 | ||||

| B. | Arranging books, papers, and documents | 142 | ||||

| C. | The summary and closing plea | 143 | ||||

| II. | Presentation of Rebuttal | 146 | ||||

| 1. | Attention to argument of opponent | 146 | ||||

| 2. | Selecting arguments to be refuted | 147 | ||||

| 3. | Reading quotations | 149 | ||||

| 4. | Teamwork | 149 | ||||

| 5. | Treatment of opponents | 150 | ||||

| 6. | The summary and closing plea | 152 | ||||

| CHAPTER VIII | ||||||

| DELIVERING THE ARGUMENT | ||||||

| I. | Methods of delivering the argument | 153 | ||||

| 1. | Reading | 153 | ||||

| 2. | Memorizing the argument verbatim | 154 | ||||

| 3. | Memorizing the argument by ideas | 155 | ||||

| II. | Physical preparation for delivery | 158 | ||||

| 1. | Position | 159 | ||||

| 2. | Voice | 160 | ||||

| 3. | Emphasis | 162 | ||||

| 4. | Key, rate, and inflection | 162 | ||||

| 5. | Gesture | 164 | ||||

| 6. | Transitions | 165 | ||||

| 7. | Presenting charts | 166 | ||||

| III. | Mental preparation for delivery | 167 | ||||

| 1. | Directness | 167 | ||||

| 2. | Earnestness | 169 | ||||

| 3. | Confidence | 170 | ||||

| xvPART II | ||||||

| The Theory of Argumentation and Debate | ||||||

| CHAPTER I | ||||||

| INDUCTIVE ARGUMENT | ||||||

| I. | The Application of Processes of Reasoning to Argumentation | 175 | ||||

| II. | Inductive Reasoning | 176 | ||||

| III. | The Application of Inductive Reasoning to Inductive Argument | 179 | ||||

| IV. | Requirements for an Effective Inductive Argument | 182 | ||||

| 1. | Perfect inductions | 182 | ||||

| 2. | Imperfect inductions | 183 | ||||

| A. | The number of specific instances supporting the conclusion must be sufficiently large to offset the probability of coincidence | 183 | ||||

| B. | The class of persons, events, or things about which the induction is made must be reasonably homogeneous | 185 | ||||

| C. | The specific instances cited in support of the conclusion must be fair examples | 186 | ||||

| D. | Careful investigation must disclose no exceptions | 187 | ||||

| E. | The conclusion must be reasonable | 188 | ||||

| CHAPTER II | ||||||

| DEDUCTIVE ARGUMENT | ||||||

| I. | Deductive Reasoning | 190 | ||||

| II. | The Application of Deductive Reasoning to Deductive Argument | 196 | ||||

| III. | The Enthymeme | 201 | ||||

| xviCHAPTER III | ||||||

| ARGUMENT FROM CAUSAL RELATION | ||||||

| I. | Argument from Effect to Cause | 208 | ||||

| 1. | The alleged cause must be sufficient to produce the effect | 210 | ||||

| 2. | No other cause must have intervened between the alleged cause and the effect | 211 | ||||

| 3. | The alleged cause must not have been prevented from operating | 212 | ||||

| II. | Argument from Cause to Effect | 213 | ||||

| 1. | The observed cause must be sufficient to produce the alleged effect | 215 | ||||

| 2. | When past experience is invoked it must show that the alleged effect has always followed the observed cause | 215 | ||||

| 3. | No force must intervene to prevent the observed cause from operating to produce the alleged effect | 216 | ||||

| 4. | The conclusion established should be verified by positive evidence whenever possible | 217 | ||||

| III. | Argument from Effect to Effect | 218 | ||||

| CHAPTER IV | ||||||

| ARGUMENT FROM ANALOGY | ||||||

| I. | The two factors in the analogy must be alike in all particulars which affect the conclusion | 228 | ||||

| II. | The alleged facts upon which the analogy is based must be true | 231 | ||||

| III. | The conclusion established by the analogy should be verified by positive evidence whenever possible | 232 | ||||

| xviiCHAPTER V | ||||||

| FALLACIES | ||||||

| I. | Fallacies of Induction | 235 | ||||

| 1. | The number of specific instances relied upon to support the conclusion should be determined | 235 | ||||

| 2. | The class of persons, events, or things about which the induction is made should be scrutinized with a view to determining whether it is homogeneous | 236 | ||||

| 3. | Whether or not the specific instances cited in support of the conclusion are fair examples should be determined | 236 | ||||

| 4. | A search should be made for exceptions to the rule stated by the induction | 237 | ||||

| 5. | The induction should be examined with a view to determining its reasonableness | 237 | ||||

| II. | Fallacies of Deduction | 238 | ||||

| 1. | Material fallacies | 238 | ||||

| 2. | Logical fallacies | 239 | ||||

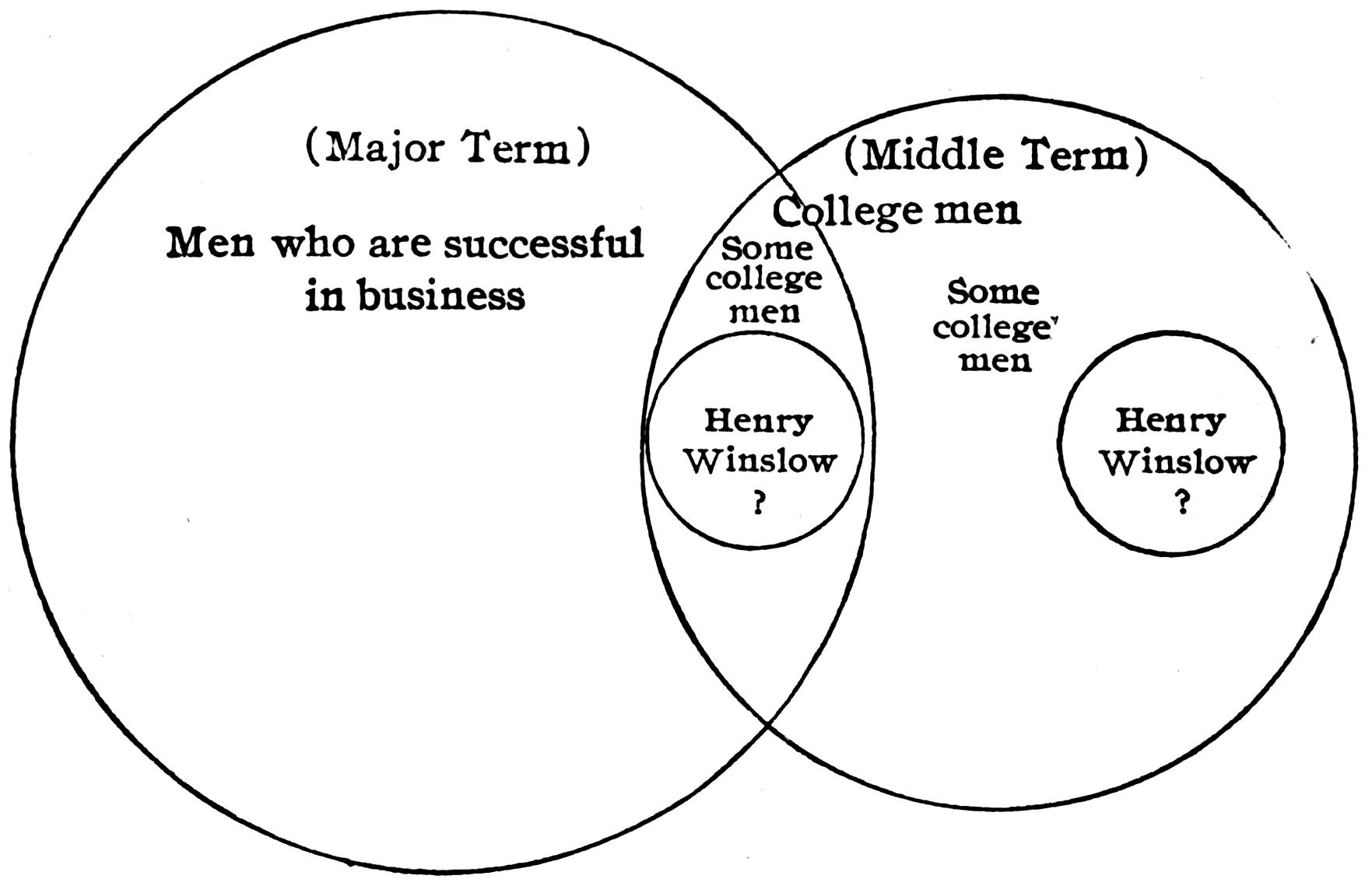

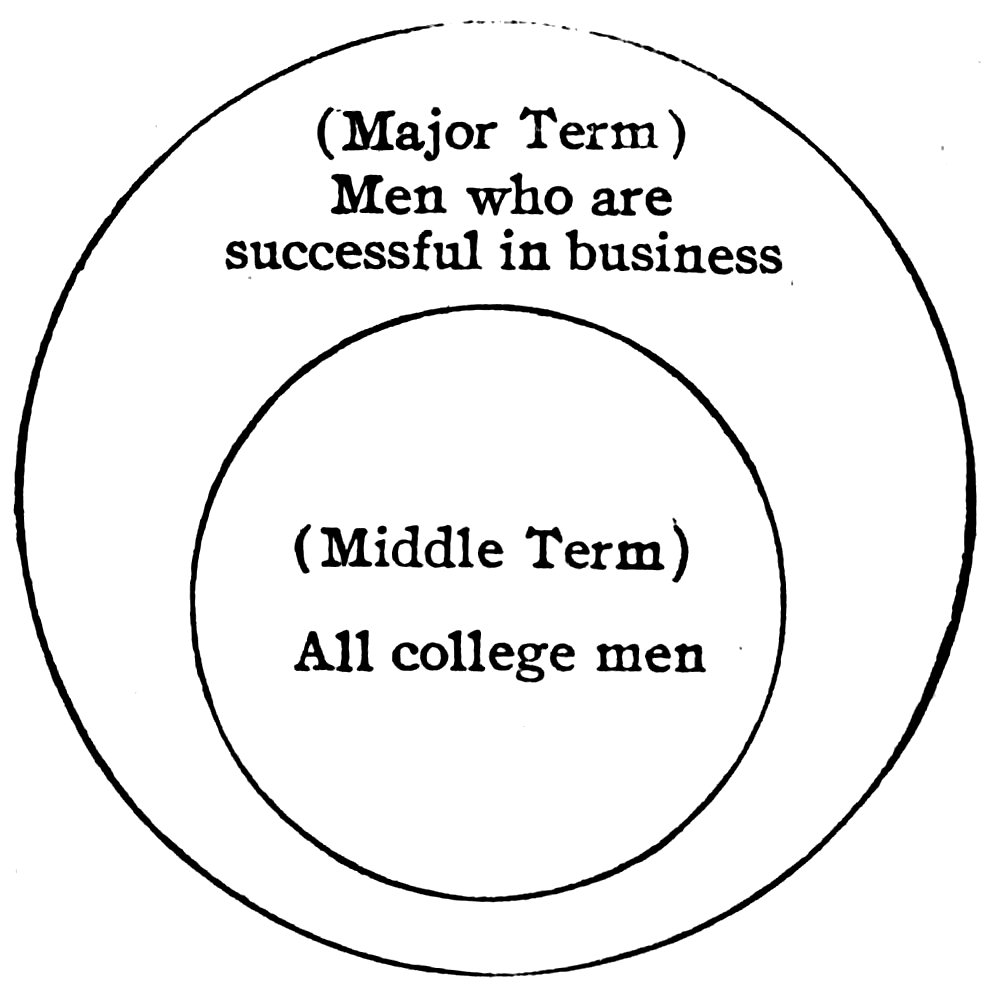

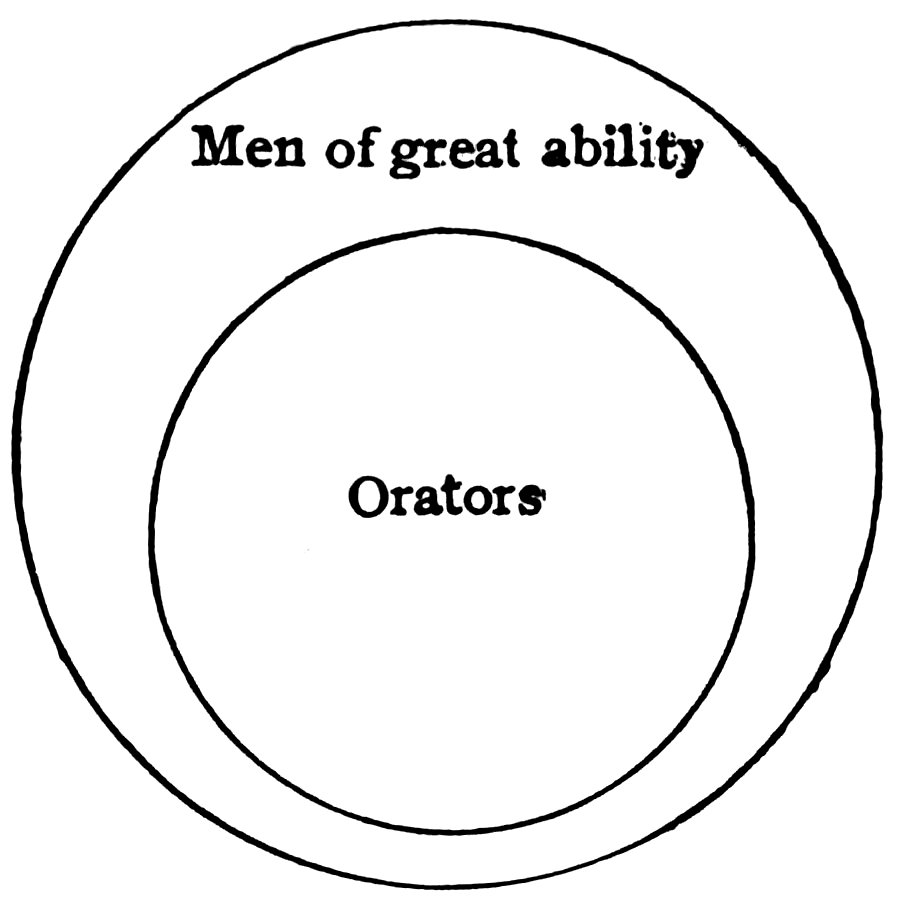

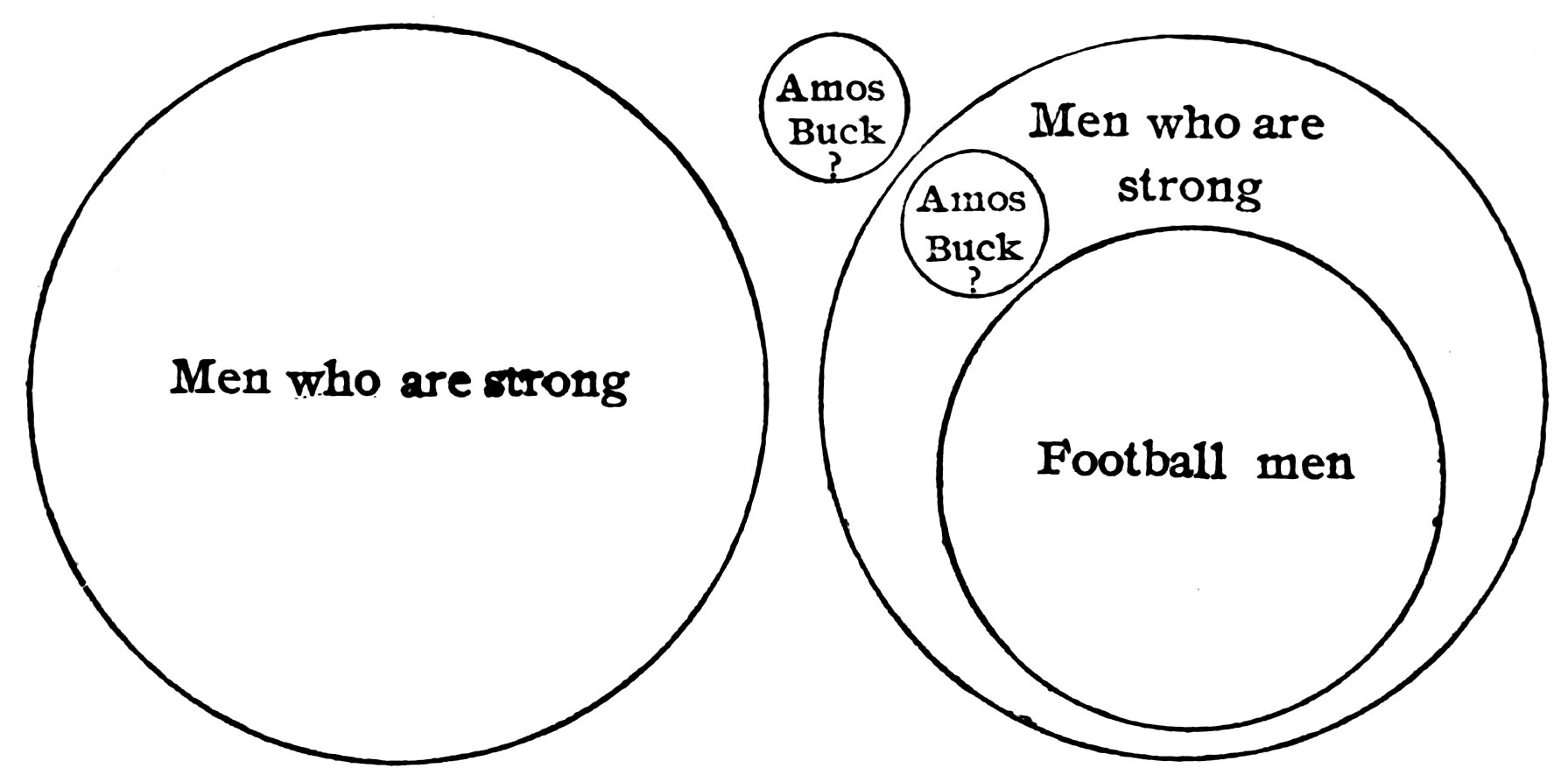

| (1) | The undistributed middle | 239 | ||||

| (2) | The illicit process | 244 | ||||

| (3) | Irrelevancy of the premises, or ignoring the question | 245 | ||||

| A. | The appeal to passion, prejudice, or humor | 246 | ||||

| B. | The personal attack upon an opponent | 246 | ||||

| C. | The personal attack upon the person or persons concerned in the controversy | 246 | ||||

| D. | The appeal to custom and tradition | 247 | ||||

| E. | Shifting ground | 248 | ||||

| F. | Refuting an argument which has not been advanced | 248 | ||||

| G. | Arguing on a related proposition | 248 | ||||

| (4) | Begging the question | 249 | ||||

| A. | Arguing in a circle | 249 | ||||

| xviii | B. | Directly assuming the point at issue | 250 | |||

| C. | Indirectly assuming the point at issue | 251 | ||||

| III. | Fallacies of Causal Relation | 252 | ||||

| 1. | Fallacies of the argument from effect to cause | 252 | ||||

| (1) | Mistaking coincidence for cause | 253 | ||||

| (2) | Mistaking an effect for a cause | 254 | ||||

| (3) | Mistaking a subsequent cause for a real cause | 254 | ||||

| (4) | Mistaking an insufficient cause for a sufficient cause | 255 | ||||

| 2. | Fallacies of the argument from cause to effect | 255 | ||||

| 3. | Fallacies of the argument from effect to effect | 256 | ||||

| IV. | Fallacies of the Argument from Analogy | 256 | ||||

| CHAPTER VI | ||||||

| REFUTATION | ||||||

| I. | Revealing a Fallacy | 261 | ||||

| II. | Reductio ad Absurdum | 262 | ||||

| III. | The Dilemma | 263 | ||||

| IV. | Residues | 265 | ||||

| V. | Inconsistencies | 267 | ||||

| VI. | Adopting an Opponent’s Evidence | 268 | ||||

Argumentation is the art of persuading others to think or act in a definite way. It includes all writing and speaking which is persuasive in form. The salesman persuading a prospective customer to buy goods, the student inducing his fellow-student to contribute to the funds of the athletic association, the business or professional man seeking to enlarge his business and usefulness, and the great orator or writer whose aim is to control the destiny of nations, all make use of the art of argumentation to attain their various objects. These illustrations serve but to indicate the wide field of thought and action which this subject includes. Each instance in this broad field, which demands the use of the art of argumentation, is subject to the same general laws that govern the construction and presentation of formal arguments. Formal arguments may be either written or oral, but by far the greater benefit to the student of argumentation results from the delivery of oral arguments, for it is in this form that he will be most frequently railed upon to use his skill.

4Debating is the oral presentation of arguments under such conditions that each speaker may reply directly to the arguments of the opposing speaker. The debate is opened by the first speaker for the affirmative. He is then followed by the first speaker for the negative, each side speaking alternately until each man has presented his main speech. After all the main speeches have been delivered the negative opens the rebuttal. The speakers in rebuttal alternate negative and affirmative. This order gives the closing speech to the affirmative. Practice in this kind of formal debate should go hand in hand with the study of the text after the first five chapters have been mastered. The first arguments, however, should be individual arguments written out for the purpose of enabling the student to apply the rules regarding their form and development.

A proposition in argumentation is the formal statement of a subject for debate. It begins with the word “Resolved,”—followed by the statement of the subject matter of the controversy, and worded in accordance with the rules laid down in the next chapter. In formal debate it is always expressed; as for example, “Resolved, that the Federal Government should levy a progressive income tax.” In other forms of argumentation it may be only implied, as in the case of the salesman selling goods, the student soliciting subscriptions, the business man arguing for consolidation, or the politician pleading for reform. Nevertheless, it is always advisable for the speaker or writer to have clearly in mind a definite proposition as a basis upon which to build his argument. The proposition for the salesman might be, “Resolved, that James Fox ought to buy a piano;” for the student solicitor, “Resolved, that George Clark ought to give ten dollars to the athletic fund;” for the business man, “Resolved, that all firms engaged in the manufacture of matches should consolidate;” and for the politician, “Resolved, that the tariff 5schedule on necessaries should be lowered.” This framing of a definite, clear-cut proposition will prevent wandering from the subject and give to the argument the qualities of clearness, unity, and relevancy.

Referring to the definition with which this chapter opened the student should note that it defines argumentation as an art. While it is true that argumentation must be directed in accordance with scientific principles, and while it is also true that it has an intimate relation with the science of logic, yet it is primarily an art in which skill, tact, diplomacy, and the finer sensibilities must be utilized to their fullest extent. In this respect argumentation is an art as truly as music, sculpture, poetry, or painting. The successful debater must be a master of this art if he hopes to convince and persuade real men to his way of thinking and thus to direct their action.

The object of argumentation is not only to induce others to accept our opinions and beliefs in regard to any disputed matter, but to induce them to act in accordance with our opinions and beliefs. The end of argumentation is action. The form which this action is to take depends upon the nature of the disputed matter. It may be only an action of the mind resulting in a definite belief which will exert an influence in the world for good or evil. It may be the desire of the one who argues to persuade his hearers to advocate his opinions and beliefs and thus spread his doctrines to many other individuals. It may be that some more decided physical action is desired, such as the casting of a vote, or the purchase of a certain article or commodity. It may be the taking up of arms against a state, race, or nation, or the pursuit of a definite line of conduct throughout the remainder of the life of the individual addressed. These and many other phases of action may be the objects of the debater.

From the standpoint of mental discipline no study offers more practical training than does argumentation. It cultivates that command of feeling and concentration of thought which keeps the mind healthily active. The value of this kind of mental exercise cannot be overestimated. Especially is it valuable when the arguments are presented in the form of a debate, in which the speaker is assigned to defend a definite position and must reply to attacks made on that position. Such work brings forth the best powers of mind possessed by the student. It cultivates quickness of thought, and the ability to meet men on their own ground and conduct a successful encounter on the battlefield of ideas.

Another faculty of mind which debating develops is tact in the selection and presentation of material. Since the object of debate is action, it is not enough that the speaker show his position to be the correct one. He must do more than this; he must make the hearer desire to act in accordance with that position. Otherwise the speaker will be in the same position as the savage who induces his fellows to conform to his ideas by the use of a club,—the moment the influence of the club is removed the subject immediately reverts to his former habits of thought and action. If you convince a man that he is wrong by the mere force of argument, he may be unable to answer your argument but he will feel like a man who has been whipped in a physical encounter—though technically defeated he still holds to his former opinions. There is much truth in the old saying that, “He who is convinced against his will is of the same opinion still.” Therefore, the debater must do more than merely convince his hearer; he must persuade him. He must appeal to the reason, it is true, but he must also appeal to the emotions in such a way as to persuade his hearer to take some definite action in regard to the subject of dispute. Thus there are two things 7which the debater must attempt—conviction and persuasion. If he convinces his hearer without persuading him, no action is likely to follow. If he persuades his hearer by appealing to his emotions, the effect of his efforts will be short lived. Therefore, the debater must train himself to persuade his hearer to act in accordance with his wishes as well as to find reasons for such action and give them.

Finally, debating cultivates the ability to use clear and forcible language. Practice of this kind gives the student a wealth of expression and a command of language which is not otherwise possible. The obligation to reply directly to one’s opponents makes it necessary for the student to have such command of his material that he can make it apply directly to the arguments he has just heard.

The educational value of debating is greater than that of any other form of oral or written composition because it cultivates: (1) The command of feeling and concentration of thought which keep the mind healthily active, (2) The ability to state a clear-cut proposition, and to analyze it keenly by sifting the essential from the trivial, thus revealing the real point at issue, (3) The ability to find reasons and give them, (4) The power to state facts and conditions with that tact and diplomacy which success demands, (5) The power to persuade as well as convince, (6) The power of clear and forcible expression. Certainly any subject which tends to develop these qualities ought to receive the most careful attention of the student.

From the practical standpoint no study offers better preparation for the everyday affairs of life than does argumentation and debate. Success in life is largely a matter of reducing every situation to a definite, clear-cut proposition, analyzing that proposition or picking out the main points 8at issue, and then directing one’s efforts to the solution of the problem thus revealed. To be more concrete: One young man accepts the first situation which is brought to his notice when he graduates, and stays in a mediocre position for years; another young man thinks carefully over the matter, picks out a place where he is most likely to succeed, and secures rapid promotion. Instances might be multiplied indefinitely to show the practical value of argumentative training. The man who is an expert in the use of argument holds the master key to success in all lines. It is an invaluable asset to every one who has to deal with practical affairs. It matters not whether you are to address one individual or a thousand—whether you wish to persuade to a certain course of action, your employer, a committee, a board of directors, a town council, the senate of the United States, or an auditorium full of people, knowledge of the use and application of the rules of argumentation, and good training in the art of debate is a most valuable asset. The business world, the professional world, and the political world eagerly welcome the man who can think and who can effectively present his thoughts. In every business, in every profession, and in every department of government the skilled debater becomes the leader of men.

Argumentation demands a definite concrete subject. This subject must be one about which there is a dispute; as for example, the liquor question. There is a great controversy as to what ought to be done in this matter. Many people contend that Prohibition, or the absolute forbidding of the making or selling of all intoxicating liquors, is the best method of procedure. On the other hand many people contend that High License, or the regulating of the sale of such liquor, is the best method of procedure. This is a proper subject for a written argument or an oral debate, because the writer or speaker may take either Prohibition or High License and show why, and in what way, it would benefit the community. If he defends Prohibition he must prove that it will benefit the community more than High License. If he defends High License he must prove that it will benefit the community more than Prohibition. This example illustrates what is meant by a definite, concrete subject about which there is a dispute.

In selecting a subject for debate the following requirements should be carefully observed:

The subject must be one in which both speaker and audience have a real interest. If the argument is written the subject must be one in which the readers are interested. 10With this object in view, the question selected should be practical rather than theoretical. That is, it should be a question the final determination of which will affect the welfare of the individual, the community, or the nation. No longer can interest be aroused in a discussion of whether the pen is mightier than the sword, or whether fire is more destructive than water. Objectionable in like manner are the following questions taken from a book on debating published in 1869: “Who is the most useful to society: the farmer or the mechanic?”, “From which do we derive the greatest amount of pleasure: hope or memory?”, “Are lawyers a benefit or a curse to society?”, “Is there more pleasure in the pursuit than in the possession of a desired object?”, “Who most deserves the esteem of mankind: the poet, the statesman, or the warrior?”, and “Whether there is more pleasure derived from the eye or the ear?” These and all similar subjects should be avoided chiefly because they lack interest, since no practical result can follow their determination. As well might one try to interest a modern audience in the discussions of the ancient schoolmen, who grew eloquent over a dispute as to how many angels could dance on the point of a needle, whether there could be two hills without an intervening valley, and whether God could make a yardstick with only one end. If men are to be interested the speaker or writer must get close to the questions which affect their everyday life at home and at work. If he does this and his ideas are worth defending he will always find willing hearers and readers.

Among interesting subjects for debate, questions of a local character hold an important place. The advisability of building a town hall, an athletic field, or a new bridge is very often more productive of genuine interest than some weighty problem of national politics. Such questions come close to the tax-payers and residents of any community, and at the 11same time appeal to their pride, prejudice, and ambition. If the student will but look about him he will find an abundance of controverted local matter which will furnish excellent subjects for oral or written arguments.

After the student has exhausted local subjects he may turn his attention to the broader controversies of state and nation. Here the questions of taxation, tariff, commerce, and international affairs afford ample scope for the full development of the debater’s powers. The list of subjects in the appendix may be found helpful in making a proper selection, but preference should always be given to questions in which the people at large are showing an active interest at the time of the debate. What this interest is may be determined by consulting the current numbers of the most widely circulating magazines and newspapers, such as the “Independent,” “Nation,” “Harper’s Weekly,” and the various city newspapers.

Since the object of the first few debates is to make the student familiar with rules and forms, the subjects chosen should be within the range of his information and experience. For this purpose subjects of a local character are best adapted. The student should have had some actual practice in debating before he attempts to take up questions which require extended investigation. Such propositions as those relating to the tariff, taxation, municipal problems, and Federal control of industrial and commercial activities should be reserved for more mature efforts.

The following subjects are fair examples of desirable questions for first practice: (1) Should students who attain a rank of ninety per cent, or higher, in their daily work be excused from examinations?, (2) Should gymnasium work 12be made compulsory?, (3) Should first year students at —— be allowed to engage in intercollegiate athletics?, (4) Should the class rushes at the beginning of the college year be discontinued?, (5) Should the game of football be abolished?

If the first two requirements in regard to the choosing of a subject are observed it is not probable that the question will be undebatable. However, since it is always advisable to keep as far as may be from one-sided questions, it is well to give this requirement some consideration.

In the first place, the question must not be obviously true or obviously false. The clearest examples of subjects objectionable because obviously true are found in geometry. It is plain that an intelligent debate cannot be held on the proposition, “Resolved, that the sum of the three angles of a triangle is always equal to two right angles.” Equally useless from the standpoint of argumentation is it to dispute that “All men are mortal,” that “Huxley was a great scientist,” or that “Health is more desirable than sickness.” Nevertheless questions just as obvious as these are sometimes debated because their real character is concealed under cover of confused language. The following question is a good example of this, “Resolved, that breach of trust in high office is reprehensible.” A moment’s thought will convince the reader that such a proposition is not debatable because obviously true. On the other hand propositions which are obviously false are sometimes worded so as to have an appearance of validity. Such is the following, “Resolved, that the only way to benefit humanity is to destroy the trusts.” To prove this proposition it is necessary to show that education, religion, and commerce cannot be made to benefit humanity. The proposition is not debatable because it is obviously false.

In the second place, the question must be one which is 13capable of approximate proof. It is not debatable if it cannot be proved approximately true or false. The debater must be able, by means of reasoning based upon the facts of the case, to arrive at a conclusion either for or against the proposition. To make this possible, there must be a common standard of comparison. This common standard does not exist in the proposition “Resolved, that the lawyer is of more use to society than the doctor,” because their work is entirely unlike and both are necessary to the well-being of modern society. On the other hand it does exist in the proposition “Resolved, that Federal control of life insurance companies is preferable to State control.” This question hinges on the comparative efficiency of the two means of control, namely,—Federal and State, both of which are governmental in character. Therefore a common standard of comparison exists which enables the debater to show why one or the other method should be adopted.

Thus far we have dealt with the subject-matter of the proposition and have seen that it must meet the three foregoing requirements. We must now turn our attention to the phrasing of this subject in such a way that it will form a suitable proposition for debate.

1. The subject must be interesting.

2. Subjects for first practice should be those of which the debater has a general knowledge.

3. The subject must be debatable.

To those unfamiliar with the art of debate it often seems that when the subject is chosen but a moment’s time is required to whip it into the form of an acceptable proposition for a debate. This, however, is not the case; the work is only 14half done. After an interesting, suitable, and debatable subject has been chosen there still remains the important task of expressing that subject in proper form.

The subject for debate should be stated in the form of a resolution. One form of such resolution would be, “Resolved, that the Federal government should levy a progressive income tax.” A mere statement of the subject is not enough. One may write a description of “The Panama Canal,” or a narrative on “The Adventures of a Civil Engineer in Panama,” or an exposition on “The Cost of Building the Panama Canal,” but for an argument one must take one side or the other of a resolution, as for example, “Resolved, that the United States should fortify the Panama Canal.” This resolution is usually termed the Proposition, and corresponds to the motion, resolution, or bill presented in deliberative assemblies such as state legislatures or the branches of Congress. The proposition must contain one definite issue. In it there must be no ambiguous words or phrases. Otherwise the debate is liable to degenerate into a mere quibble over words or a dispute as to the meaning of the proposition. Hence no issues will be squarely joined and after the debate is over, neither the debaters, the judges, nor the audience will feel satisfied or have reason to believe that any progress has been made toward a right solution of the question.

The proposition for debate should be worded in accordance with the following rules:

In the beginning there is always a tendency to make the proposition cover too broad a field. This is rather a defect of wording than of subject-matter. Let us take a proposition which is too broad, and narrow it so that it will contain but 15a single idea. For this purpose we may select the proposition, “Resolved, that freshmen should not be permitted to take part in athletics.” As it stands, this proposition includes all freshmen everywhere and prohibits them from taking part in athletics of every kind. In other words the field which it covers is too broad. The proposition treats of two things, freshmen and athletics. Let us first make the provision in regard to freshmen definite, that is, narrow it down to a field with definite limits. We can do this by making it apply only to the freshmen of Columbia University or of any other specified institution. Thus the collecting of material as well as the determination of the issues involved becomes a much simpler matter. In the second place let us make the provision in regard to athletics more definite. As the proposition stands it excludes freshmen from all athletics whatsoever, including inter-class and inter-society as well as intercollegiate. Here again the field is too wide and some restriction must be placed upon the subject-matter. Therefore we insert the word “intercollegiate” before the word “athletics” in order that the field for discussion may be narrowed down to a single, definite issue. With these modifications the proposition now stands, “Resolved, that freshmen at Columbia University should not be permitted to take part in intercollegiate athletics,” which is an entirely satisfactory proposition because it narrows the field of discussion to one definite, central idea.

Though this difficulty will doubtless present itself in a variety of forms, the principles stated above as well as the illustration, if kept in mind by the student, will enable him to keep clear of this fault.

The first argument is always presented by the affirmative. Upon the affirmative rests the burden of proof and if the affirmative 16proves nothing the decision goes to the negative. “He who affirms must prove.” The affirmative has the burden of proving the proposition to be true, the negative that of proving it false. Therefore the proposition must be worded in the affirmative. This insures that some progress will have been made at the end of the first speech.

The burden of proof rests upon the party who has the risk of non-persuasion. The risk of non-persuasion rests upon the party who would fail if no evidence were introduced. We have seen that the affirmative would fail if no evidence were introduced, because he who alleges must prove. Therefore the risk of non-persuasion rests on the affirmative. To be more concrete, if you are attempting to prove to a friend that he ought to do (or ought not to do) a certain thing, you take the risk of not persuading him to do the thing that you ask, i. e. the risk of non-persuasion is on you. Likewise the salesman who approaches a customer with the purpose of selling him a bill of goods incurs this same risk of non-persuasion, because he may not be able to induce the customer to buy. Since, as in the above cases, the affirmative must be given a chance to prove something before the negative can reply, the proposition should always be worded in the affirmative.

After the proposition has been narrowed down to a single idea and has then been stated in the affirmative, it should be carefully scrutinized in order to determine whether it contains any ambiguous words. Ambiguous words have a meaning so broad that they may be taken in more than one sense. Such a word is “Anarchist.” This word may refer to a lawless individual bent on assassination, or to a peaceable individual who has merely the beliefs of an anarchist with no intention of putting them into practice. Almost all general 17terms such as “Anarchist,” “Monroe Doctrine,” “Civilization,” “Policy,” and “Trusts,” should be avoided because they tend to make the proposition ambiguous. When such terms are used they should be almost invariably accompanied by explanatory words. The words selected for use in the proposition should have but one meaning and should be so plain that there can be no reasonable dispute as to their significance. If this rule is not complied with the discussion will become a foolish quibble over the meaning of the proposition rather than an intelligent debate upon the merits of the question.

In the question, “Resolved, that trusts should be suppressed by law,” there are three ambiguous words, (1) trusts, (2) suppressed, and (3) law. While these words may not be ambiguous in ordinary speaking or writing, they are not sufficiently definite to be used in a proposition. The word “Trust” has several meanings and several shades of meaning. Among these is the meaning which has recently been given to it, indicating a combination of firms engaged in some special line of business, as for example, “The Sugar Trust”, “The Oil Trust”, “The Steel Trust”, etc. Even this one meaning has different variations. The term “trust” as used in this sense may refer to a mere combination of manufacturers, to a monopoly, or to a monopoly in restraint of trade. In order to make the meaning of the proposition clear we may strike out the ambiguous term “trusts” and insert “monopolies in restraint of trade.”

The word “suppressed” in this connection may have two well defined meanings. It may mean either destruction or regulation. If the intent is that the question shall hinge on whether or not monopolies in restraint of trade should be destroyed or wiped out altogether, the word “dissolved” or “destroyed” should be used. If, on the other hand, it is intended that the issue shall be whether such organizations 18be allowed to exist in their present form, but subject to governmental regulation which will suppress their evil effects on trade, the word “regulated” should be used. For the purpose in hand let us choose the latter meaning.

The term “law” is also somewhat ambiguous, because there is more than one legal agency which could deal with such organizations. Therefore we will make plain which agency is intended by modifying the word “law” by the word “Federal.” This makes the proposition, as corrected, read, “Resolved, that monopolies in restraint of trade should be regulated by Federal law.” The proposition as thus worded is fairly free from ambiguity and leaves little opportunity for quibbling over the meaning of the words in which it is stated.

The proposition must be so worded as to have the same meaning for both the affirmative and the negative, and this meaning must be absolutely clear and unambiguous.

After the proposition has been worded in accordance with the foregoing rules it should be carefully scrutinized to determine whether or not there is a simpler form in which it may be cast without sacrificing any of its excellencies. The simpler the wording of the proposition the easier will be the work of determining the main issues and the subsequent work of preparing the argument.

In dealing with broad general problems such as questions of finance, commerce, and taxation, it sometimes happens that some issue is brought in which is aside from the real merits of the controversy and yet so vitally connected with it as to be logically inseparable. Either side may present such material, with disastrous results if their opponents have dealt solely with the real merits of the controversy. An instance 19of this difficulty appeared in the debates of one of the Inter-State leagues. For three or four successive years the questions chosen for the annual debates were of the character indicated above. In many of the debates one or the other side of the controversy would bring up the constitutionality of the proposed measures. The charge would be made that the proposition could not be decided in the affirmative because the proposed measure was contrary to the constitution of the United States. In almost every case this question vitally affected the final adoption of the resolution, although it could well be excluded from a discussion on the merits of the problem. The question was especially exasperating, inasmuch as the judges for the debates were almost always selected from the bench of the Supreme Court of the states composing the league and from the Federal Courts. It was finally determined by the official board of the league to append the phrase “Constitutionality conceded,” to all propositions in which there was any likelihood that the question of constitutionality could be made an issue. Thus in one instance the proposition adopted was, “Resolved, that the Federal Government should levy a progressive inheritance tax. Constitutionality conceded.”

This did not in any way interfere with the simple wording of the proposition, and it did effectually prevent the debate from hinging on an issue which would have prevented a full discussion of the merits of the question. This method of excluding undesirable matter is preferable to an attempt to include any restriction in the body of the proposition. The latter method is quite likely to lead to difficulties, in the form of ambiguities and their attendant evils, almost impossible to foresee when the proposition is framed.

In conclusion, the debater must not forget that time spent in selecting a proper subject and wording it in accordance with the foregoing rules is time well spent. It will make the 20great task which lies before him much easier, and it will enable him to arrive at definite conclusions.

1. The proposition should be so narrowed as to embody only one central idea.

2. The proposition should be stated in the affirmative.

3. The proposition should contain no ambiguous words.

4. The proposition should be worded as briefly and simply as is consistent with the foregoing rules.

1. Write out three propositions in accordance with the rules stated in this chapter. The subject-matter of these propositions should be purely local in character as suggested in the first and second sections.

2. Phrase, in proper form, one proposition on each of the following subjects.

A. Sunday baseball.

B. Interstate commerce.

C. Labor unions.

D. United States Senators.

E. Prohibition.

F. Reciprocity.

3. Apply the appropriate rules to each of the following propositions and point out where each is defective.

Resolved, that—

A. We derive more pleasure from hope than from memory.

B. Wit and humor are the same.

C. Education ought to be compulsory.

D. The law is a better profession than medicine.

E. The Federal Government should levy a tax on large incomes and limit the amount of wealth which one man may possess.

F. It is expedient for the United States to build a larger navy.

The subject for argument has been determined and it has been reduced to a satisfactory proposition. The next step is to analyze this proposition. It is well to consider first the importance of this analysis in order that its true value may be appreciated, and this preliminary step be not passed over hurriedly. Upon the success of the analysis depends in large measure the success of the argument. This is true because the analysis shows just what must be proved in order to sustain or overthrow the proposition. If the work has been done carefully the student will have confidence in the solidity of his argument. He cannot feel secure if he suspects that his analysis is defective.

The question of analysis is not only of supreme importance in relation to a particular proposition for discussion, but it is also of the greatest importance in all the practical affairs of life. No mental quality is so necessary as the analytical habit of mind. Practically all the men whom history calls great have possessed in a large degree the habit of analyzing everything. Lincoln was in the habit of applying this analytical process not only to great affairs of state but to anything and everything which came beneath his notice. He analyzed the actions of his fellow men, the workings of a machine, the nature of moral principles, and the significance of political movements. He was continually penetrating to the point of things, visible and invisible, and laying it bare.

22Everything which comes up for personal action should be analyzed and the vital point at issue determined. Nothing should be done blindly or in a spirit of trusting to luck or chance. Instead of voting as the majority seem to be voting in a class meeting, analyze the issue and vote according to the light revealed by that analysis. Instead of entering some business or profession blindly and in the hope that something will turn up, analyze the situation and determine rationally what ought to be done. For the right determination of these practical affairs no better preparation can be made than the careful analysis of propositions for debate.

In the first place the student must know something about the subject-matter of the proposition. If the question is of a local character and one with which he is familiar, the work of analysis may be begun at once. The proposition can be scrutinized, its exact meaning determined, and the proof for its establishment or overthrow decided upon. If the question be one with which the student is not familiar, his first duty is to become acquainted in a general way with the subject-matter. He should carefully examine the proposition to see just what subject-matter is included and then consult someone familiar with its substance, or read some material which appears to treat the subject in a general way. Here confusion is likely to result if an attempt is made to substitute reading for thinking. The mind of the investigator should be kept open, free, and independent. He should not allow the opinions of men, either oral or written, to cause him to depart from the precise wording of the proposition. His present object is to determine its limits, meaning and significance.

When a general knowledge of the subject has been acquired, sufficient to enable the student to reason about the 23question, he should next consider the origin and history of the question.

The meaning of a question must be determined in the light of the conditions which gave rise to its discussion. For this reason it is well to find out just how this question came to be a subject of debate. For example, the people of this country a few years ago were debating the proposition, “Resolved, that the Federal Government should control all life insurance companies operating within the United States.” To one unacquainted with the facts of the case at that time the proposition appears at first glance to lack point. Why should anyone want Federal control of insurance companies? What difference does it make as to who controls them or whether they are controlled at all? These questions are answered directly when we come to study the origin of the proposition. Until within a few months of the discussions no one had thought of debating this proposition. The insurance companies had always been under the control of the states in which they operated. Then suddenly it came to light that these companies were grossly mismanaged. Dishonesty had characterized the administration of their affairs. This served to cast grave doubt on the efficiency of state control. Therefore the stronger arm of the Federal government was suggested as a remedy for the evils which the states had been unable to prevent. The real heart of the controversy, which a study of the origin of the question revealed was “Will the control of insurance companies by the Federal government be more efficient than that exercised by the state governments?” Thus the real point at issue was made clear through the origin of the question.

In the search for the main issues, the history of the question is often important. However, the tendency of the inexperienced 24debater is to dwell too long upon this part of the argument. Actual practice often reveals the fact that such a history causes the audience or reader to lose interest. This is especially true if its bearing on the argument is not immediately shown.

The history of the question should, however, receive serious consideration, and any facts which bear directly upon its solution should be stated in brief and concise form. When the question has undergone a change because of shifting conditions, its history becomes especially important. Very often the original significance of a controversy becomes entirely changed by subsequent happenings. In such a case the history of the question should be resorted to for the purpose of finding out the changes through which the original dispute has passed and determining the exact issues involved at the present time.

Before proceeding farther it is well to examine each word in the proposition. Now that a general idea of the significance of the proposition has been obtained, and the main point of the controversy reached through the study of the origin and history of the question, the task of defining terms may be undertaken in an intelligent manner.

Let it be understood at the outset that a dictionary definition is not satisfactory. A dictionary gives every meaning which can be attached to a given word and thus covers a broad, general field. But when a word is used in a proposition for debate it is used in a special and restricted sense. The meaning depends largely on the context of the proposition. The origin and history of the question, the meaning which expert writers on this particular subject have attached to the words, and the present conditions must be considered in determining the precise meaning of the terms.

25The words of a proposition which need definition are very often so grouped that the meaning of a phrase or combination of words taken as a whole must be determined. Here it is plain that dictionary definitions, even if satisfactory in other respects, would be entirely inadequate. In the question in the last chapter, “Resolved, that monopolies in restraint of trade should be regulated by Federal law,” we find a necessity for the definition of both a term and a phrase. The term “regulate” may not in this instance be given the broad meaning which a dictionary definition attaches to it. We must first look at the context of the proposition in order to find out to what field of authority we should go for a proper definition.

The proposition specified regulation by Federal law; therefore we must go to the law for our definition of the term which indicates the action the law is to take. But even here we need not be satisfied with the broad legal definition of the term “regulate.” The field included by the question is obviously a commercial field. The agencies which would come under this regulation are for the most part engaged in interstate commerce. Therefore the power to regulate would be placed under that clause of the United States constitution which expressly gives Congress the power to regulate commerce. We may then rely upon the definition which the courts have placed upon the term “regulate” when used in this connection. By consulting Black’s Constitutional Law,[1] an eminent authority on this subject, we find that the power to “regulate” has never been held to include the power to destroy. This eliminates a possible meaning. By consulting some of the decisions of the United States courts in which this term has been defined, we are given to understand that to “regulate” commerce implies that “an intention to promote and facilitate it, and not to hamper or destroy it, is naturally 26to be attributed to Congress.” (Texas & P. R. Co. v. Interstate Commerce Commission, 162 U. S., 197; Interstate Commerce Commission v. Alabama Midland Ry. Co., 74 Fed., 715). Therefore we are warranted in concluding that to “regulate” in this proposition means such control by the Federal law as will promote the best commercial interests of the country at large.

It is thus seen that both the definition of the term and the source from which it is taken are determined by the context of the proposition. If the context of the proposition shows that legal definitions are required, legal authorities must be consulted. If the context of the proposition shows that an economic definition is required, economic authorities should be consulted. In whatever field of knowledge the context of the proposition lies, the authoritative definitions generally accepted in these branches of learning should be consulted.

In defining the phrase “monopolies in restraint of trade” the student should consult the same class of authorities utilized in defining the term “regulate.” The generally accepted definitions used by prominent writers may be relied upon with safety, since they are usually taken directly from authoritative reports and decisions.

One of the most important requisites of a definition is that it be reasonable. It must appear, in the light of all the circumstances of the case, to be the most obvious and natural definition which can possibly be produced. In no case must it appear that the speaker or writer has laboriously searched for a definition which will conform to his view of the proposition. Equally fatal is a highly technical definition which ignores its evident meaning. No trickery based upon a technicality should be tolerated. The definition presented must be so reasonable that everyone concerned (with the possible exception of one’s opponents) will willingly admit its validity.

The next step in the analysis of the question is to narrow it down to the points which must be proved. Now that the meaning of the question is well understood this task ought not to be difficult. Nevertheless it demands the most earnest efforts of the student. There are two steps in this process, (a) Excluding irrelevant matter, (b) Admitting matters not vital to the argument.

The first task is to cut away all surplusage. The proposition as it now stands, should be closely examined in order to determine just what must be proved. Neither the affirmative nor the negative should undertake the burden of proving more than is necessary. In the discussion of the proposition “Resolved, that Prohibition is preferable to High License,” it is not necessary for the affirmative to prove that temperance is a virtue. The task before these debaters is to show only that prohibition is preferable to high license as a method of dealing with the liquor traffic. It is not necessary for the negative to attempt to prove that temperance is not a virtue; their task is to show only that high license is preferable to prohibition. It is true that temperance as an abstract virtue is very closely related to the subject-matter of the proposition, but it is not one of the real points at issue. When the question has been narrowed down to the method of dealing with the liquor traffic, each side may prove this point in the way which appears most effective. Each may assert that its method of control is preferable because theory and practice show it to be better for (a) social, (b) political, and (c) economic reasons. Any other division of the subject which seems effective may be adopted.

It is evident from the above illustration that certain matters which are relevant to the general subject should be 28eliminated in order that the audience may understand just what must be proved. Everything that is not relevant to the proposition as stated should be excluded.

Since the debater should not attempt to prove more than is necessary he should admit, in the beginning, such matters as may be admitted without detriment. Great care should be exercised at this point; nothing should be admitted the full bearing and significance of which the debater does not understand. Only matters which may be admitted with safety should be included. Otherwise an opponent may seize upon the admitted matter and turn it to his own advantage. Furthermore, the language used in making an admission should be carefully guarded lest an opponent ingeniously attach to it a meaning which was not intended.

With these cautions in mind it is well to continue the process of narrowing the question by admitting matters not vital to the argument. These admissions should be made in the beginning in order that they may appear in their true light as free admissions. For example, in the last question discussed both sides may safely admit that neither plan will wholly eliminate intemperance. The object is to adopt the plan which will minimize the effect of this evil. In the question, “Resolved, that physical valuation of the property of a corporation is the best basis for fixing taxation values,” the affirmative may safely admit that no basis for fixing taxation values will work absolute justice to all tax-payers. This places the affirmative speakers in position to make plain to their hearers that the method advocated will come nearer to the goal of absolute justice than any other plan. In advocating any reform it is usually best to admit that it is not a cure-all for existent evils, but that it will remedy such evils to a greater extent than any other measure.

29In conclusion, it is well to remember that these admissions and exclusions should be made plain rather than elaborate. They should be stated in the introduction of the argument with such brevity and clearness that the audience will realize that it is being led directly to the vital issues.

Thus far we have been concerned with finding out the vital point at issue. It is here that the term question is most aptly applied to the proposition for debate, because when this vital point is revealed it is always found to appear in the form of a question. To be more specific, we found that in analyzing the proposition, “Resolved, that the Federal Government should control all life insurance companies operating within the United States,” the vital point at issue as revealed by a study of the origin of the question was “Will the control of insurance companies by the Federal Government be more efficient than that exercised by the State Governments?” This treatment reveals the main point at issue in the form of a question. It shows that the issue is between State control on one side as compared with Federal control on the other. The affirmative must advocate Federal control and the negative must defend State control. The burden of proof is on the affirmative, for it must show that a change should be made in existing conditions. The risk of non-persuasion is upon the affirmative, because, if the position advocated cannot be maintained, existing conditions will continue.

It is well to remember that the burden of proof remains with the affirmative throughout the debate. It is frequently said that the burden of proof “shifts,” that is, that when the affirmative has produced enough evidence to make out a prima facie case, and has shown reason why the plan ought to be adopted, then the burden of proof shifts to the negative 30and it becomes the duty of the negative to show why the plan should not be adopted. This is not the correct view of the situation, for the affirmative is bound to prove the proposition in the face of all opposition. Therefore the burden of proof never “shifts;” it is the duty of producing evidence which “shifts.” When the affirmative shows reason why the proposition should be maintained, it puts upon the negative the duty of producing evidence to show that the affirmative reasoning is unsound or that there are more weighty arguments in favor of the negative. Thus it is that the duty of producing evidence shifts from one side to the other, but the burden of proof remains on the same party throughout the discussion.

The question upon which the debate hinges must be answered in one way by one side and in just the opposite way by the opponents of that side. In the question above referred to, “Will the control of insurance companies by the Federal Government be more efficient than that exercised by the State Governments?”, the affirmative must answer “Yes” and the negative must answer “No.”

At this point the next task of the analyst begins. He must determine the main reasons why the affirmative should answer “Yes” and the negative should answer “No.” These main reasons when discovered and contrasted, those on the affirmative with those on the negative, will reveal the main issues of the proposition. When these are found the process of analysis is completed.

In undertaking the task of contrasting the affirmative contentions with those of the negative, the student must assume an absolutely unbiased attitude toward the proposition. The importance of this impartial viewpoint cannot be too strongly emphasized. To be able to view any subject with a mind free from prejudice is a most valuable asset.

With this proper mental attitude toward the proposition 31the analyst must take up both sides of the question and find the main arguments in support of each. He should not be deluded into thinking that it is only necessary to study one side of the question. A lawyer in preparing his case always takes into consideration the position of his opponent. In fact, so important is this task that many lawyers develop their antagonist’s case before beginning work on their own, and it frequently happens that more time is devoted to the arguments of the opposition than to the case upon which the lawyer is engaged. This careful study of an opponent’s arguments must always be included in the work of the debater, not only in the analysis of the question but throughout the entire argumentative process.

The way in which this part of the analytical process should be carried out is best made plain by a concrete example. We will take the proposition “Resolved, that immigration into the United States should be further restricted by law.” The origin of the question is found in the alarm shown by some people over the large number of undesirable foreigners coming to our shores. The question is “Should any of the immigrants now coming to our shores be prohibited from coming?” The affirmative say “Yes,” and the negative, “No.” Now to take the impartial viewpoint, why should there be any further restriction of immigration; why should the affirmative say “Yes” and the negative “No”? One of the chief affirmative arguments is that some of these immigrants are having a bad effect upon our country. Some of them are anarchists; some are members of criminal societies such as the Black Hand; some group by themselves in certain portions of large cities and form what are known as “Little Germanys”, “Little Spains”, “Little Italys”, etc.; some have contagious diseases; some have a very low standard of living and thus tend to drag down the standard of living of the American workman; some are illiterate and do not make 32good citizens; some are easily made the dupes of city bosses and ward “heelers” and thus exert a harmful influence in our political affairs. These and various other reasons may be brought to support the affirmative argument that immigration is having a bad effect upon our country.

In considering the matter carefully we come to the conclusion that these are the chief reasons why immigration should be further restricted. Now, the unskilled debater would probably be content with framing these reasons into an argument and would proceed with a feeling that his position was impregnable. The skilled debater, however, does not feel content until he has viewed the whole subject impartially. Why do we not have more stringent immigration laws? It must be that the present laws are thought to be satisfactory. Why are they satisfactory? It must be because they now exclude the worst class of immigrants. Upon investigation we find this to be true. Let us look at the problem from a slightly different point of view. Why do we allow all of these immigrants to come in? They must be necessary to our welfare. They are necessary to develop the natural resources of our country; they add to the national power of production, they possess a money value as laborers; they ultimately become American citizens, and their children, educated in our public schools, become the most ardent of young Americans.

The above reflections from the standpoint of the negative lead us to ask a few questions which must be answered before we can answer the main question upon which the proposition hinges, namely: “Should any of the immigrants now coming into the United States be prohibited from coming?” These questions are, so far as we have been able to determine: “Are the present immigration laws satisfactory?”, “Do we need all the immigrants now coming to us?”, “Do the immigrants now coming to us have a bad effect upon our country?” These 33questions if answered “Yes” will establish the affirmative, and likewise if answered “No” will establish the negative. We may therefore conclude that these three questions contain the main issues of the proposition. The issues may be stated in different forms, but, if resolved to their essential elements, they will ultimately be found in these three questions.

The next step in contrasting the arguments is to write them down in such form that corresponding arguments can be set over against each other. For convenience we adopt the following form:

| Proposition:—Immigration should be further restricted by law. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affirmative argument | Negative argument | ||||

| Immigration should be further restricted, because | Immigration should not be further restricted, because | ||||

| I. | It is a detriment to the country, for | I. | It is a benefit to the country, for | ||

| 1. | We now admit extreme socialists and anarchists. | 1. | The worst elements are now excluded. | ||

| 2. | They form undesirable groups of foreigners in the congested parts of cities. | 2. | They are soon assimilated. | ||

| 3. | They lower the standard of living of the American workman. | 3. | They furnish examples of thrift to American workmen. | ||

| 4. | Many of the immigrants now admitted do not make good citizens. | 4. | They ultimately become good citizens. | ||

| II. | The present laws are not satisfactory, for | II. | The present laws are satisfactory, for | ||

| 1. | Black Hand societies show that undesirable persons are admitted. | 1. | No law would exclude all undesirable immigrants. | ||

| 34 | 2. | Diseased persons are admitted. | 2. | All persons having contagious diseases are excluded. | |

| 3. | Steamship lines help to evade the immigrant laws. | 3. | Custom house officials are diligent in enforcing the laws. | ||

| 4. | Paupers are admitted. | 4. | Paupers are not admitted. | ||

| III. | We do not need all the immigrants now coming to us, for | III. | We need all the immigrants now coming to us, for | ||

| 1. | The great necessity for laborers to develop our natural resources has passed. | 1. | We need them to develop our natural resources. | ||

By contrasting the arguments thus tabulated we derive the following main issues.

I. Is immigration under existing conditions a detriment or a benefit to the country?

(The answer depends upon the answers to these subordinate questions.)

1. Is the undesirable element excluded?

2. Have the immigrants assimilated readily?

3. Do they exert a detrimental influence upon the standard of living of the American workman?

4. Do they make good citizens?

II. Are the present laws satisfactory?

1. Are they the most effective in excluding undesirable immigrants that it is possible to enact?

2. Do they exclude diseased persons?

3. Do the present laws exclude paupers?

4. Are the present laws enforced?

III. Do we need all the immigrants now coming to us?

1. Do we still need all the immigrants we can get to develop our natural resources?

This arrangement of the affirmative and negative arguments places the whole matter, so far as it has been worked 35out, before the student in tangible form. It also affords a basis for the formal statement of the main issues. The plan of analysis thus set forth should now be examined with a critical eye. Here arise some of the most difficult problems of argumentation. In the first place, is the analysis presented an exhaustive one? Does it include the entire field of argument? It includes the proposed immigration laws and their probable effects. It includes the present laws and their effects. From these two facts it is evident that the analysis covers the entire field of the proposed change in the immigration laws.

Before passing final judgment upon the thoroughness of the analysis, there are at least two other plans which may be applied to the question to see whether either of them will afford a better method of treatment than the foregoing. The first of these plans includes the division of the question into three parts; viz. (1) political, (2) social, and (3) economic. An examination of the question just discussed will show that all the material suggested in the formal analysis could be grouped under one or the other of these heads. For example, the anarchists, Black Hand societies, etc. would come under “political;” the question of assimilation would come under “social;” while the effect upon the American workman and the question of the development of our natural resources would come under “economic.”

This division may be applied to many questions, but it is well suited to only a limited number. In fact, some eminent authorities are of the opinion that it is almost never to be recommended. It is not as well adapted to the immigration question as the division already made, for the reason that it would be necessary to include some of the subject-matter under two separate heads. For example, the Little Spains, Little Italys, etc., mentioned above, might require treatment under the social and political divisions and even under the 36heading of economics. This is objectionable, because it requires a duplication of the statement of facts under each head, and also because it is not conducive to the clean, clear-cut thinking which is the result of a sharp division of the subject into parts which do not overlap.

The second plan of analysis, which forms a good working basis for many propositions, is that of dividing the subject into three parts, namely, (1) Necessity, (2) Practicability, and (3) Justice. This division of the subject is often applicable to propositions which advocate the adoption of some new plan of action, as, “Resolved, that the Federal Government should levy a progressive inheritance tax,” or “Resolved, that cities of the United States, having a population of over 5,000, should adopt the commission form of government.”

These and similar questions may be analyzed by one of the two plans stated above, but it is well to beware adopting one or the other of these methods merely because it affords an easy way out of the task of analyzing the proposition. That analysis of a question should be adopted which reveals the main issues of the proposition in the clearest and most direct manner.

1. A broad view of the subject.

2. The origin and history of the question.

3. Definition of terms.

4. Narrowing the question.

(1) Excluding irrelevant matter.

(2) Admitting matters not vital to the argument.

5. Contrasting the affirmative arguments with those of the negative.

The process of analysis with which we are dealing has revealed the main issues of the proposition. It now becomes the duty of the debater to arrange the issues in logical and 37climactic order. The most forcible array of argument should come at the end. For example, in the question just analyzed the logical as well as the climactic order of arrangement for the main issues on the affirmative would be as follows:

I. The present laws are not satisfactory.

II. We do not need all the immigrants now coming to us.

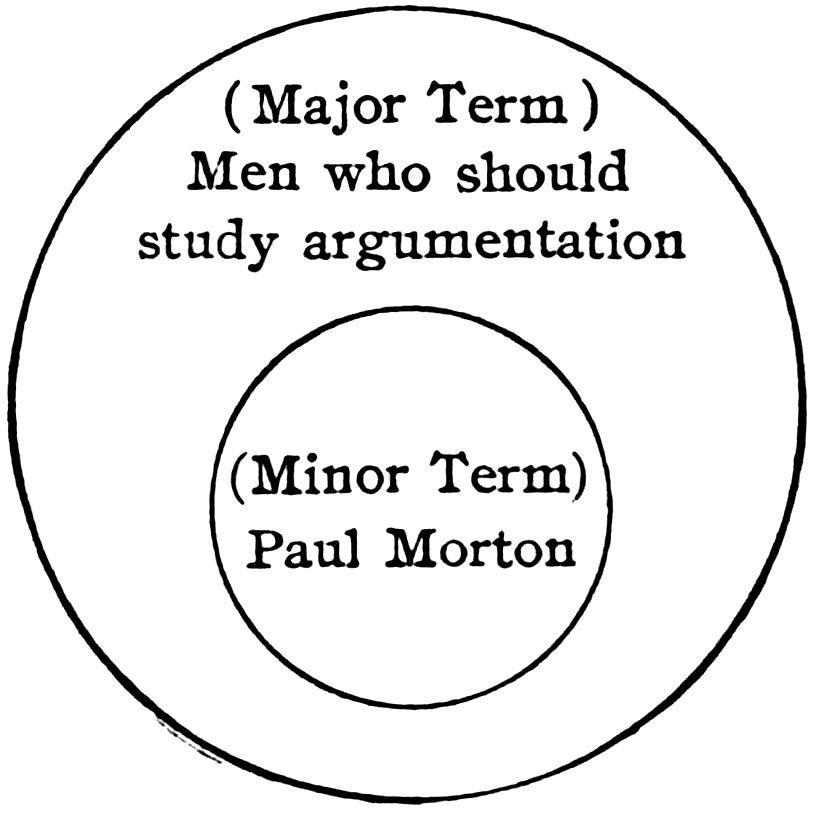

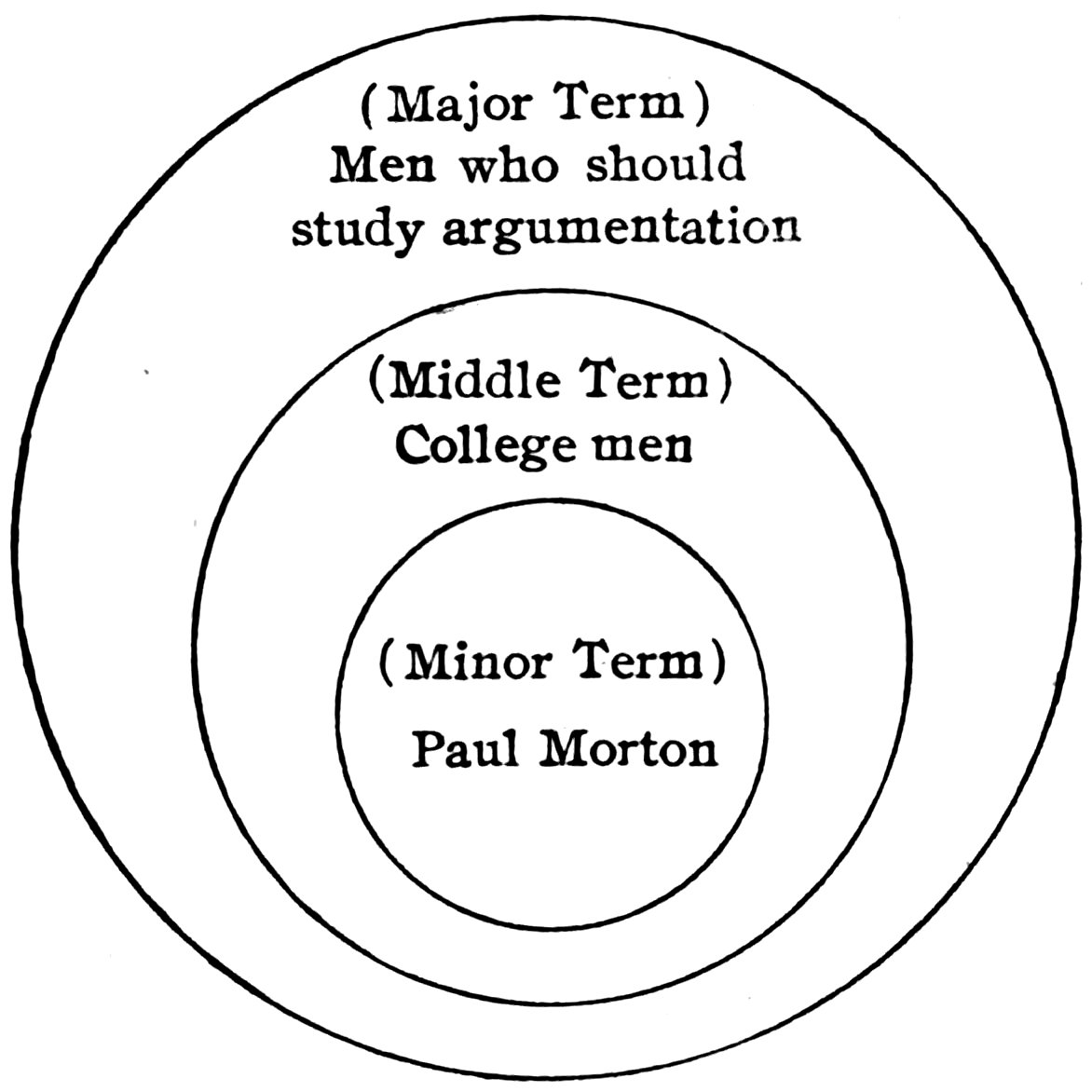

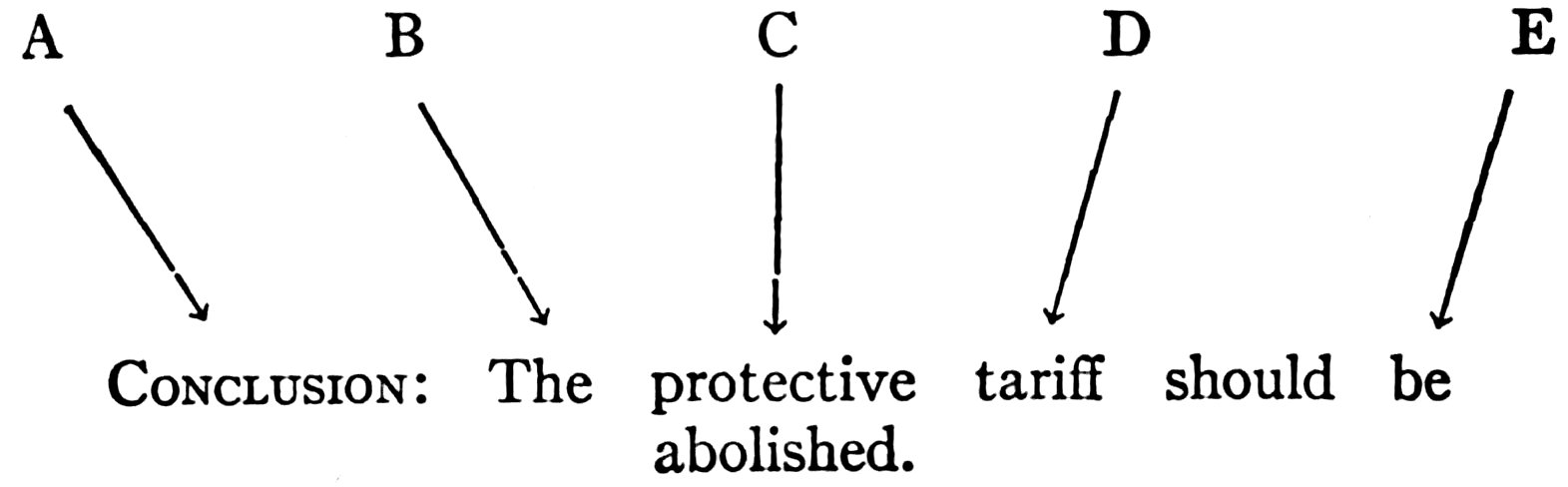

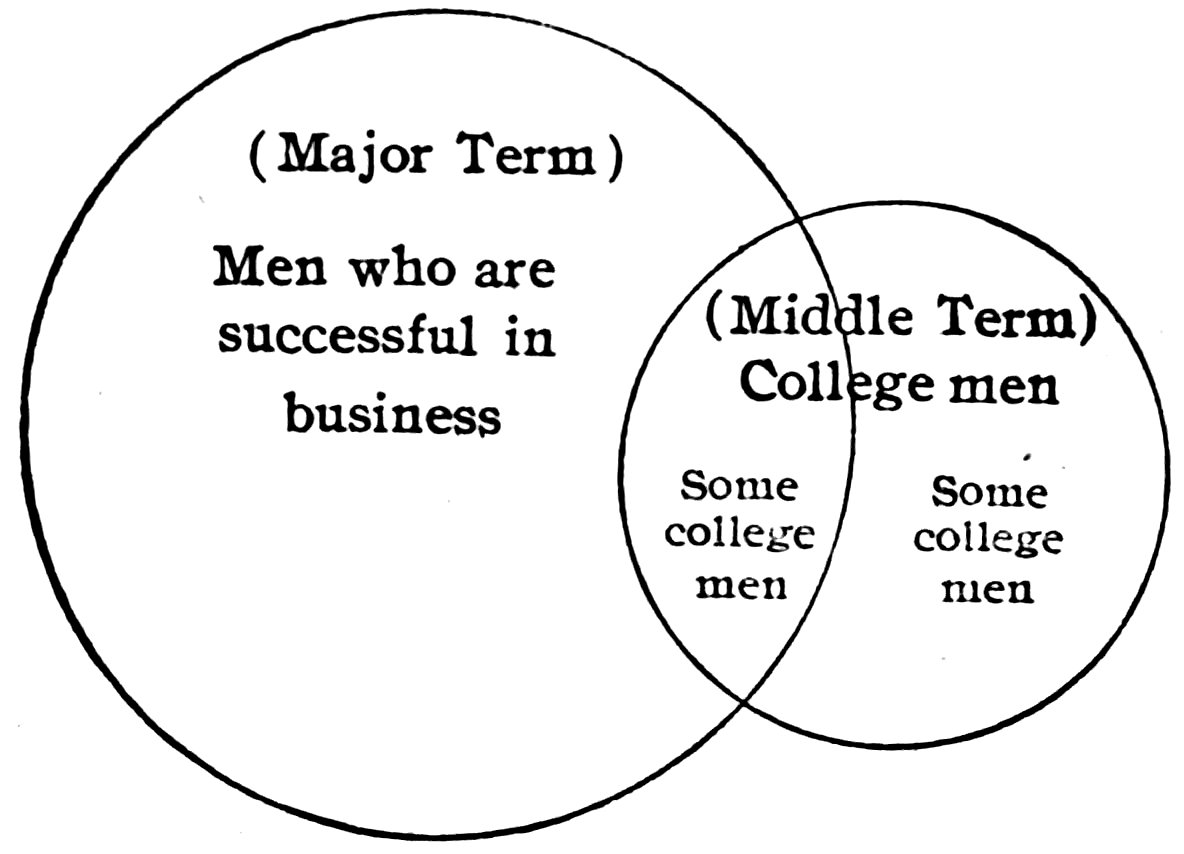

III. Immigration (under the present system) is a detriment to the country.