“The good man is he who does not lose his child-heart.”—Mencius, 371-288 B.C.

THE EMPEROR OF CHINA

CHILDREN OF CHINA

BY

COLIN CAMPBELL BROWN

AUTHOR OF

“CHINA IN LEGEND AND STORY”

WITH EIGHT COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS

OLIPHANTS LTD.

LONDON EDINBURGH

Uniform with this Volume

Printed in Great Britain by Turnbull & Spears, Edinburgh

Bound by Anderson & Ferrier, St Mary Street, Edinburgh

TO

ROBIN, MARGERY AND HUGH

My dear Boys and Girls,

There is a nook among the hills in far-away China to which, if only I possessed the famous flying carpet, I should very much like to carry you. To know it properly one ought to find it for oneself upon a day in spring. The road to it runs at the foot of steep hills, on which the grey earth peeps through a threadbare carpet of dry grasses.

Above these lower hills the mountain-sides are green, shading into slate-colour and black; and when the sky clouds over, they look dark and angry. The road rounds a corner and passes a wood: a few more steps and the baby valley is in sight.

To leave the path and pick your way through some trees is the work of a moment. You reach an open space like a little lawn. Above the lawn is a bank, on which, among shrubs and scattered trees, many flowers are growing.

A faint scent of almonds breathes in the air. You feast your eyes on great wild roses and azaleas, rose-coloured, magenta, crimson—bushes of red fire burning among ferns and green branches. Here, you notice tufted flowers like feathers carved in ivory: there,[7] white jasmine, clematis and plants whose shining leaves are nearly covered by balls of snow. Over the flowers and under the tree-tops great swallow-tailed butterflies go whirling by. It is as if one of the old men of the hills of whom Chinese stories tell, had opened a doorway in the mountain-side and led you into a sweet wild garden of fairyland.

The daily round of life in China is bare enough, like a worn road winding among hills; but when one comes to know the children of the country, it is like finding a surprise garden where one had only looked for rocks and boulders. The love of boys and girls, and the tenderness and self-denial which they call forth among older people, are the flowers that grow in this enchanted spot.

The flying carpet was lost long ago, when this old world forgot how to be young, but you boys and girls sometimes weave one for yourselves and fly off as far as Pekin or Peru. It is my hope in these pages to join some of you in this pleasant task and carry you to some of the far-off garden nooks of China.

The Chinese by Sir John F. Davies, Child Life in Chinese Homes, by Mrs Bryson, and Chinese Slave Girls, by Miss M. E. Talmage, are books which have helped me to write about the children of China. I am sure they will interest you by and by whenever you can find time to read them. But the big Chinese city in which I live, and the hundreds of villages round it, help me most of[8] all to tell you about China and its boys and girls, and I greatly hope that one day some of you may come and see them for yourselves.

I am,

Your sincere friend,

C. Campbell Brown.

Chinchew, 1909.

| PAGE | ||

| Introductory Letter | 6 | |

| I | The Invisible Top | 11 |

| II | Chinese Babies | 14 |

| III | The Children’s Home | 18 |

| IV | School Days | 23 |

| V | Girls | 30 |

| VI | Games and Riddles | 37 |

| VII | Stories and Rimes | 42 |

| VIII | Religion | 52 |

| IX | Festivals | 58 |

| X | Superstitions | 63 |

| XI | Reverence for Parents | 73 |

| XII | Faithfulness | 76 |

| XIII | The Cry of the Children | 80 |

| XIV | Ministering Children | 87 |

| XV | The Children’s King | 94 |

| The Emperor of China | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Chinese Babies | 16 |

| Child leading Buffalo | 20 |

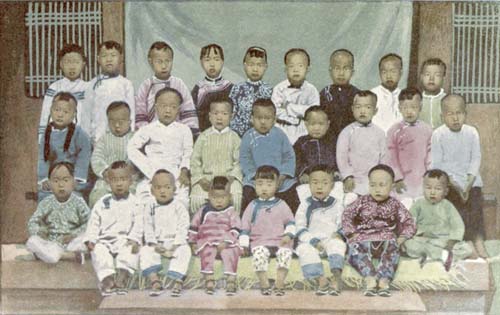

| Kindergarten Pupils | 28 |

| Children at Food and at Play | 40 |

| Going to visit his Idol Mother | 60 |

| Phœnix | 84 |

| Sunday School, Chinchew | 88 |

The beginning of the world, as it is described to Chinese boys and girls, is stranger than a fairy tale. First of all, according to the story, there was something called ‘khi’ which could not be seen, nor touched, but was everywhere. After a time this ‘khi’ began to turn round like a great invisible top. As it whirled round, the thicker part sank downwards and became the earth, whilst the thinner part rose upwards, growing clearer until it formed the sky, and so the heavens and the earth span themselves into being. Presently, for the story changes like a dream, there came a giant named Pwanku. For thousands of years the giant worked, splitting masses of rock with his mallet and chisel, until the sun, moon and stars could be seen through the openings which he had made. The heavens rose higher, the earth spread wider, and Pwanku himself grew six feet taller every day. When he died, his head became mountains, his breath wind, and his voice thunder; his veins changed into rivers, his body into the earth, his bones into rocks and his beard into the stars that stream across the night sky. But though all this is only ‘a suppose story’ of long ago, the first part of it is wonderfully like what wise men in our time have told us about the beginning of things.

[12]Now we must talk of China as it is to-day. The country in which Chinese children live is a land of hills and plains, covered with cities, villages and temples. You can imagine how big it is when you remember that Szechuan, which is but one of its eighteen provinces, is larger than Great Britain and Ireland.

How China grew into a great empire is one of the most wonderful stories of the world. Its people are said to have come from the west, across the middle of Asia, settling at length in what is now the province of Shansi, just where the Yellow River bends sharply eastwards. Small at first and surrounded by savages, the baby kingdom soon began to grow. Like the tiny tent of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, which unfolded until an army could rest beneath the roof, China spread until, a thousand years before the time of Our Lord, its borders on the north and west were pretty much what they are to-day, and it had crept southwards many miles beyond the Yellow River. The nation went on growing, drawing other tribes and peoples into itself, until, not long after King Alfred’s time, the mother kingdom, without counting its subject countries, was fifteen times as large as Great Britain.

What is now the Chinese Empire is said to have been gained in peaceful ways rather than by fighting, and this no doubt is partly true. The people knew more than their neighbours did. Their life was better and happier. One after another the tribes wanted to join them, and so the kingdom grew until one of the great changes of the world was made. This will help you to understand why the Chinese have always believed in peace rather than force, and until lately have not cared for war.

The history of China at first, like that of other nations, is rather misty. In spite of this, however, we can make out that long ago the people had wise and good men to[13] lead them, among whom were Yao and Shun, the model rulers of the empire, and Yu the Great, who drained the waters of a vast flood and cut down forests until the land was fit to dwell in. Much has happened since then. Greece and Rome have risen, flourished, and decayed. This nation, under many different families of rulers, and in spite of some seventeen changes of capital, has outlived them by centuries. Turks, Mongols and Manchus have fought against it, and, as in the present day, at times have conquered the country, only to be conquered in turn by the wonderful Chinese people.

Of all the many changes in China’s story, perhaps none has been more startling than that which happened in 1908, when the Emperor Kwangsu and the Empress Dowager died, within two days of each other. The whole country was thrown into mourning, almost all the people going unshaved for a hundred days, until long hair and bristling faces made the Chinese world look sad indeed.

On the 2nd December of the same year, the Emperor Hsuan Tung, born in 1906, ascended the Dragon Throne, and so the oldest of Empires came to have the youngest of sovereigns for its ruler, and the world discovered that the greatest child on earth was a little Chinese boy. It is said that the baby emperor, frightened by the sight of so many people in state dress, began to cry when he was set upon the throne. He was soon comforted, however, by some of the ladies-in-waiting, and sat quietly until the grand ceremony was finished.

The little man is the first ruler of China who, from the beginning of his reign, has had prayer offered for him by Christian people all over the empire, and we may be sure that blessing will be given to him in answer to these prayers. Boys and girls everywhere[14] ought to ask God to help the boy sovereign of the last great heathen empire of the world.

Here is a description which opens a window for us into his nursery: “Young as he is, the emperor shows a great love of soldiers, and has little spears and swords and horses among his playthings. The sight of toy weapons will stop him from crying and make him laugh. His Majesty is much pleased when a horse is shown to him, and will not be satisfied until he has been lifted on to its back and taken for a ride.”

A difference is made between boys and girls in China, but it is not so great as the following lines might lead you to think:

In winter time little King Baby is rolled in clothes until he looks like a ball, though his feet and part of his[15] legs are usually bare. When asleep he is laid in a bamboo cradle, on rough rockers which loudly thump the floor. A red cord is tied to his wrist, lest he should be naughty when grown up, and people should say, “They forgot to bind your wrist when you were little.” Ancient coins are hung round his neck by a string to drive away evil spirits and to make him grow up an obedient child. When he is a month old, friends and relatives bring him presents, a feast is made and Master Tiny has his head shaved in front of the ancestral tablets, which stand on a narrow table at the back of the chief room of the house. The barber who takes off the black fluff from the little round head, receives a present of money; baby, for his part, becoming the proud possessor of a cap, with a row of gilded images in front, which is presented to him by his grandmother, together with a pair of shoes[2] having a pussy’s face worked upon each toe in the hope that “he may walk as safely through life as a cat does on a wall.” Baby-boy also receives what is called his ‘milk-name,’ which serves him until he goes to school. Some of the names given to babies sound strange: Dust-pan, Pock-marked Boy, Winter Dog, One Hundred and Ten. Ugly names are sometimes given, in the hope that the spirits may think that babies so called are not worth troubling about and thus may leave them to grow up unharmed. In the same way an ear-ring is put in a little boy’s ear, and he is called Little Sister to make the demons imagine that he is only a girl, and so not worthy of their notice, or his head is clean-shaved all over, and he is dressed like a monk for the same purpose.

Girl babies, like their little brothers, are shaved at the end of the first month, but with less ceremony.[16] They are called Water Fairy, Slave Girl, Likes to Cry, Golden Needle, or some such name. Though some of the little ones suffer from neglect and hardship, many of them are happy in their babyhood. The people say, “Children are one’s very flesh, life, heart,” and when the traveller sees a father or a mother proudly carrying one of them about, or patiently bearing with its naughtiness, he can well believe that they mean what they say. Sometimes a mother pretends to bite her baby, saying, “Good to eat, good to eat”; sometimes she presses her nose against its tender cheek, as if smelling it, and kisses it again and again. The little things have shining black eyes, with long dark lashes which look so nice against the faint olive tint of the delicate skin.

When Master Tiny is a year old, another feast is made, and brightly-coloured shoes and hats are given to him. After the feast is over the little fellow is put on a table in the room where the ancestors of the family are worshipped. Round him are placed various things, such as a pen, a string of cash, a mandarin’s button, etc. Then everyone waits to see which he will stretch out a fat hand to seize, for it is supposed that the thing which he chooses will show what he is going to be or to do in the world, by and by. If baby grabs the pen, he will be a scholar; if the money takes his fancy, he will go into business; but if his eager fingers grasp the shining mandarin button, his father and mother hopefully believe that he will be a great man some day.

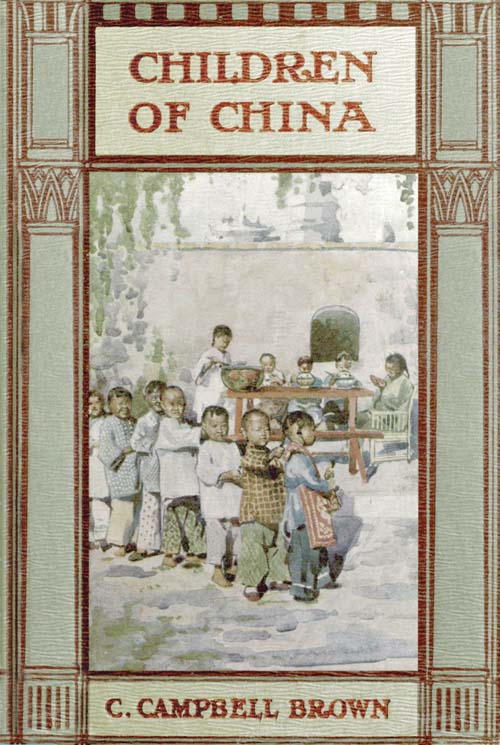

CHINESE BABIES

The Chinese are wonderfully patient and kind in treating their babies. Much of the gladness of their lives and of their homes is bound up with the boys and girls who play about their houses. They love their children, in spite of things which sometimes seem to prove that they do not When the little ones learn,[17] at church or Christian school, to know the Saviour, they bring a new gladness into the home. Not a few Chinese children have been able to interest their fathers and mothers and other friends in the Gospel, as you shall hear later on, and so the words “A little child shall lead them,” have found a new meaning in far-away China.

Here is the picture of two little twin-boys, four years old. Some time ago, one of them said to his sister: “God does not sleep at night.” His father, who had heard the words, asked, “Lien-a, how do you know that God does not sleep at night?”

“The hymn says, ‘God night and day is waking, He never sleeps,’” answered the little fellow.

“But can’t you think of something yourself which shows that God is awake at night?” asked his father.

“I hear the wind at night,” said the child, after a little pause, “and see the moon and stars.” He meant God must be awake to keep the wind blowing and the moon and stars shining.

One day a friend gave each of the twins a bright new five-cent piece. Their mother took care of the coins, saying, “I will keep them for you, until we can get enough to use as buttons for your next new jackets,” and the little fellows were ever so happy. Not long after, people were gathering money to build a new church, and the little boys’ father said to them: “Children, have you got anything which you can give to help to build the new church?” The little boys thought and thought, then one of them said, “Yes, we have our silver buttons.” So they gave their treasured little shining pennies most gladly. But I think that God was gladder still.

Homes differ as much in China as in other lands. Some are palaces, some poor huts, some are caves cut into the face of cliffs, some are boats upon rivers, where thousands of boys and girls learn to handle the oar from their earliest childhood. Some are in dusty villages by the roadside, others are set between stairs of green rice fields upon mountain slopes, or built upon flat plains among giant millet and other crops.

A large number of children are brought up in cities. You cannot easily get at their homes because of the streams of blue-clad people who throng the streets. Come for a walk among the busy shops, so that you may know something of the place where Chinese boys and girls spend so much of their time. Sedan-chairs, carried by strong men, push through the crowd, shaving butchers’ stalls and narrowly missing the heads of running children. Burden bearers, with bags of rice on their backs, or loaded with vegetables, pigs in open baskets, bales of cotton or tobacco, follow one another over the slippery pavement.

Here comes a pedlar selling tapes, needles and bits of silk. He is called a ‘bell shaker,’ because he tinkles a little bell to call attention to his wares. That poor man, with shaggy hair and half-naked skin, is ‘a cotton-rags fairy,’ or beggar. He lives in a ‘beggars’ camp’ not far away.

Look in at this temple. The heavy scent, reminding you of rose-leaves and stale tobacco, which comes through the open doorway, is the smell of incense. Beyond the court, inside the door, is a big room where[19] idols, once bright with gilding, now blackened with smoke, sit each upon its throne. Those spots of light inside the hall are made by candles burning on the altar beneath the gloomy roof.

Boys and girls do not care to go inside, unless their mothers bring them to bow before the idols. Some of the images have ugly faces, blue, black and fiery red, which children can scarcely look at without being afraid. Some are gilt and have a strange smile upon their lips. Here is description of an idol in its temple:

Let us turn down this narrow lane. Now we have left the shops and the busy street. Look at the rows of smallish houses, each with a bit of plain wall and a bamboo screen hanging in front of the door. You hear the sound of children’s voices within as you pass. How happy that little boy is, running along in bright red trousers, flying his kite. His home is near by; when he is older he will go to school, or learn a trade in one of the shops not far away.

Here the streets are narrower. What strange names they have! Stone Bird Lane, Grinding Row, Old Woo’s Lane, Bean Curd Lane, Family Ma’s Market.

Look at this big house. Turn in by the opening at the right of the front door. Now we are inside the first court, an open space with rooms all around. The[20] room in front of us is the largest in the house. A wooden cabinet stands on the narrow table against the back wall: it is full of slips of wood, each about a foot high. These slips of wood are called ‘ancestral tablets,’ because the Chinese think that the souls of their ancestors live in them. Each one has writing upon it, telling the name of the person whose soul is said to be inside.

To right and left of the chief room are two smaller ones, used as bedrooms. Behind these again is another court, with rooms ranged round it like the front one, and behind it perhaps another. Some houses have ‘five descents’; for Chinese storeys, which are called ‘descents,’ are put one behind the other, instead of being piled upwards as are ours.

You may see a girl seated at a loom, driving the shuttle to and fro. How slowly the cloth grows. Every time the shuttle flies across, the web gains a line. Thread by thread it lengthens, just as a child’s life lengthens day by day; that is why the Chinese proverb says, “Days and months are like a shuttle, light and dark fly like an arrow.” The older boys of the household are at school or at work. That woman who is washing rice in an earthen pot, has a baby slung by a checked cotton cloth upon her back. The child rolls its bullet head and sucks a fat thumb, whilst one dumpy foot sticks out below its mother’s arm. The lady in a blue tunic, with bright flowers in her hair, is the mistress of the house; see how she sways on her tiny bound feet, as she moves across the tiled floor.

CHILD LEADING BUFFALO

If the head of the house is a scholar he wears long robes of cotton or silk, blue and grey, one above the other, or in the hot weather white ‘grass cloth,’ thin as muslin. He has the top of his head shaved and wears his back hair in a long plait or queue. On New Year’s[21] day or at other special times, he puts on a pointed hat, with a flossy red tassel, top-boots and a silk jacket on which is embroidered a stork or some other bird, to show his literary rank. An officer in the army would have a bear or some other fierce animal embroidered on his jacket instead of a bird.

In country homes a mill for taking the husk off rice stands inside the door, where perhaps you might expect to find a hatstand. Sometimes a sleek brown cow moos softly on the other side of the porch. Jars, full of salted vegetables, share the front court with the usual pigs, chickens and dogs. Look at that mandarin duck, bobbing her head and throwing forward her bill, as if trying to bring up a bone which had stuck in her throat just as she was in the act of curtsying to you. She bows and curtsies all day, until even the fat baby, lying on a kerb-stone at the edge of the court, grows tired of watching her antics.

Children run in and out of the house. One plays with a big, green grasshopper, which struggles hopelessly at the end of a string. Somewhere outside, a little boy or girl is sure to be leading a buffalo by a rope, on the edge of the rice fields. Farther away some boys and girls are gathering leaves, or cutting fern on the hillside.

About noon the household gathers for dinner. The men go to the kitchen and return with bowls of rice and sweet potatoes or vermicelli. In the middle of the table they have salted vegetables, bean-curd cake cut into small pieces, dried shrimps, and on feast days, pork hash in soy, all in different dishes. Each man has two pieces of bamboo, rather thicker than wooden knitting-needles, which he holds between the thumb and first three fingers of his right hand. With these chopsticks, as they are called, he picks up a bit of[22] meat or vegetable and begins to eat it, but before it is swallowed he puts his bowl to his lips, and holding it there, pushes some rice or potatoes into his mouth. One mouthful follows another, and in no time the bowl is empty. Now you know how to answer the Chinese riddle: “Two pieces of bamboo drive ducks through a narrow door.” The ‘narrow door’ of course is a mouth, the ‘ducks’ are bits of pork and fish, the pieces of bamboo are chopsticks.

Sometimes the country people do not eat at a table, but sit in the shadow of the porch, or on the edge of the stone coping which surrounds the front court. The story is told of a poor boy, who used to eat his meals in this way. The stone on which he sat had a crack in it. When the boy began to study, he used to bring his book and a basin of food, so that he might read as he sat on the broken slab eating his dinner. By and by he became a great scholar and viceroy or ruler of the province of Szechuan. When he returned to his native place, full of riches and honour, he rebuilt the old home and made it beautiful, but he kept the broken kerb-stone unaltered, in front of the dining-room. It was left with the crack in it to remind him of the time when he was a barefoot boy and used to sit by the edge of the court, eating rice or learning his lessons.

When the men have finished their meal, the women and children have theirs. How the fat little boys and girls love sweet potatoes! They take them, pink and yellow skinned ones, in their chubby fingers and stuff them down their throats, dogs and chickens waiting eagerly meanwhile to pick up the skins and stringy bits which drop upon the ground.

Though eating apart, girls and women mix more freely with the men in these country homes than in those of educated townspeople, where they must keep to their[23] own rooms at the back of the house. Into the homes of China, so different from each other in some things, so alike in others, the message of the Saviour’s love finds its way. Here one, there another—man, woman or child, believes the Gospel and begins to serve God. In spite of persecution and unkindness, the new convert remains faithful. By and by another member of the family is won: sometimes the whole household is changed, and the home becomes a Christian home.

The Chinese people think so much of learning that they say, “Better to rear a pig than bring up a son who will not read!”

When the time comes for a boy to go to school, a lucky day is chosen by a fortune-teller, and young Hopeful, spotless in dress, and with head well shaved, is taken to be introduced to his teacher. In the neat bundle which he carries as he trots along by his father’s side he has ‘the four gems of the study’ ready for use, that is to say, a pen which has a brush for a nib, a cake of ink, a stone slab for rubbing down the ink with water, and a set of books. As soon as the new pupil has been taken into the school and introduced in the proper way, the teacher asks the spirit of Confucius to help the little scholar with his work. Then the master sits down and the boy bows his head to the ground, beseeching his master to teach him letters. After this a ‘book-name,’ such as Flourishing Virtue, Literary Rank, Opening Brightness, is[24] chosen and given to the lad; for a Chinese boy gets a new name when he goes to school. The room in which the budding scholar will sit at a little black table for many a day to come is often dark and dingy, with tiny windows and a low tiled roof.

A book, called The Juvenile Instructor, tells how children used to be trained, in the good old days of China’s greatness. It says: “When able to talk, lads must be instructed to answer in a quick, bold tone, and girls in a slow and gentle one. At the age of seven they should be taught to count and name the points of the compass, but at this age boys and girls should not be allowed to sit on the same mat nor to eat at the same table. At eight they must wait for their superiors and prefer others to themselves.... Let children always be taught to speak the simple truth, to stand erect in their proper places, and to listen with respectful attention.”

At an old-fashioned Chinese school the pupils have no A B C; but they have to learn by heart ‘characters,’ that is, the signs which stand for words in their books. Boys who expect afterwards to go into business are taught to do sums by a clerk or shopkeeper, who is hired to teach them; but the ordinary schoolboys are taught no arithmetic, or geography, or dates. Perhaps you think you would like to go to a Chinese school! But wait a bit until you hear what Chinese boys have to learn.

Beginners stand in a row before the master’s table and are taught to read the first line of the Three Character Classic, until they know it pretty well. Then they sit in their places and repeat it aloud. If one of them forgets a word, he goes up to the table again and asks his master how to read it, but he must not go too often.

[25]What a din there is with some twenty boys all reading at the pitch of their voices! The teacher does not scold them, for the busier his pupils are at their work, the noisier they become. Whenever one of the class knows his task, he hands in his book, and turning his face away, so that his back is to his master, he repeats his lesson aloud. This ‘backing the book’ (as it is called), is to prevent a dishonest pupil from using his sharp black eyes to peep over the top of the page and help himself along.

After the Three Character Classic and The Hundred Surnames, which gives a list of the family names used in China, the schoolboy reads a book called The Thousand Character Classic. This book, made up of exactly a thousand characters, is said to have been written, by order of an emperor of China, in a single night. The scholar who wrote it worked so hard, that his hair, which was black when he began his task, had turned white when the book was finished next morning. The Four Books and other Classics, as the standard books of Chinese literature are called, are next begun by the pupil.

Boys do a great deal of writing at a Chinese school: when they are able to read and to repeat quotations from their famous books, they must go on to the higher art. First they are taught how to hold the brush pen. Each boy is given a small book of red characters. He dips his sharp-pointed brush in ink and holding it straight up and down begins painting the red letters over. After a time he goes on to tracing letters on thin paper over a copy. A square of wood, painted white, serves him as a slate. On this he writes characters, which balance one another, as heaven and earth, fire and water, light and darkness. By and by he begins essay and letter-writing, which is very[26] difficult in Chinese. Pupils used to spend many years on this, but nowadays schoolboys in China have to do more sums and less writing than their fathers did.

Writing essays and verses used to be the chief lessons at a Chinese school; for when scholars were fairly good at these, they entered for the examinations. It was a difficult thing for a boy to go into the great examination hall among two or three thousand men, and, after having been searched to make sure that he had no books or cribs up his sleeves, to go and sit at a bench and write his essay. Yet many gained degrees when very young.

One of these was called Ta Pin. He had a wonderful memory and when he had read the Five Classics once over, he could remember them every word! When eight years old, Ta Pin was in the house of an elderly scholar, who was pleased by his good manners and wise ways. Seeing that he behaved more like a grown-up man than a boy, the old gentleman pointed to a chair and said: “With a cushion made of tiger’s skin, to cover the student’s chair.” Then he waited to see if Ta Pin could answer this bit of poetry as a grown-up scholar would have done, by a second line of verse, which would match what he had just said. “With a pencil made of rabbit’s hair, to write the graduate’s tablet,” answered Ta Pin, every word of his line pairing with the corresponding word in the old gentleman’s verse, ‘pencil’ with ‘cushion,’ ‘rabbit’ with ‘tiger,’ etc. The scholar struck the table with delight and gave a present to the boy. When Ta Pin was thirteen he became a Master of Arts, coming out higher than all the other competitors but one. He was afterwards second in the examination for the degree of Doctor of Letters and won the highest degree[27] of all next year. This clever boy lived over four hundred years ago, when the Ming emperors ruled in China.

The story of how Mencius’ mother looked after him whilst he was at school, is very interesting. At first they lived together near a cemetery and little Mencius amused himself with acting the various scenes which he saw at the graves. “This,” said his mother, “is not the place for my boy.” So she went to live in the market street. But the change brought no improvement. The little boy played then at being a shopkeeper, offering things for sale and bargaining with imaginary customers. His devoted mother then took a house beside a public school. Now the child was interested by the things which the scholars were taught, and tried to imitate them. The mother was pleased and said: “This is the proper place for my son.” Near their new house was a butcher’s shop. One day Mencius asked what they were killing pigs for. “To feed you,” answered his mother. Then she thought to herself, “Before this child was born I wished him to be well brought up, and now that his mind is opening I am deceiving him; and this is to teach him untruthfulness.” So she went and bought a piece of the pork, to make good her words. After a time, Mencius went to school. One day when he came home from school his mother looked up from the loom at which she was sitting, and asked him how far he had got with his books. He answered carelessly that “he was doing well enough.” On which she took a knife and cut through the web she was weaving. The idle little boy, who knew the labour required to weave the cloth, now spoilt, was greatly surprised and asked her what she meant. Then she told him that cutting through the web and spoiling her work was like his neglecting his tasks. This made[28] the lad think and determine not to spoil the web of his life by idle ways; so the lesson did not need to be repeated.[3] Thanks to the care of this wise and patient mother, Mencius grew up to be a famous man.

An old-fashioned Chinese school opens about the sixteenth of the first moon, or month, and continues for the rest of the year. The teacher often goes home to attend feasts, weddings, birthdays or funerals; or when the rice is cut, so that he may get his share of the harvest from the family fields. In the third month he has to be away worshipping at the graves of his ancestors; and in the fifth month, when the dragon boats race each other, and on other festivals in the seventh, tenth and eleventh months he will probably go home for a day or two. Whenever the master is away, the boys play and idle in the streets, unless they have to help with the harvest or run messages for their parents. So you see, although they do not have regular Easter and summer holidays, they do not fare badly.

But such schools as this will soon be left only in country villages. In the larger cities pupils and teachers alike are giving up the old slow-going ways. In the Government schools the boys wear a uniform and look like young soldiers. The classes are distinguished by stripes, like those worn on their arms by privates, corporals, sergeants and so forth. You can tell the class a boy belongs to by looking at his arm. When a visitor enters the school a bell tinkles and all the boys stand up and touch their caps, as soldiers do when saluting an officer. Inspectors visit the new schools to see how masters and scholars are doing their work.

KINDERGARTEN PUPILS

Kindergartens, where little boys and girls go to learn their first lessons, though new to China, are much [29]liked by the children and their parents, and before long will become a great power for good in the land. The little ones love to sing and march in time. Their tiny fingers are clever at making hills and islands out of sand, or counting coloured balls and marbles. Their sharp eyes are quick to see picture lessons, which are drawn for them upon the blackboard, and their ears attentive to the teacher who explains them. Ears, eyes, hands, feet, all help the little heads to learn, as reading, writing, geography and arithmetic are changed from lessons into delightful games, by the Kindergarten fairy.

When the closing day comes, crowds gather to see the clever babies march and wave their coloured flags. Fathers and mothers are ever so proud when they hear their own little children sing action-songs, and repeat their lessons without a mistake, and they gladly give money to put up buildings and train teachers for the ‘children’s garden,’ for that is what Kindergarten means.

Chinese boys and girls are fond of study, and so they will surely make their country famous once more. The romance of China is not connected with making love or fighting; it gathers round the boy who is faithful at his tasks, who takes his degree early and rises to be a great official. When the reward of years of hard work comes, he goes back to the old home, bringing comfort and honour to all his friends. This is the hope which has helped on many a little scholar and made his school life glad.

This Chinese love of learning has opened a door by which the Gospel may enter the minds of the people. Wherever missionaries have gone, they have established schools, in which many children have learnt to know God’s truth and love the Saviour.

It is hard to begin life as one who is not wanted. Many a Chinese girl cannot help knowing that she has come into the world bringing disappointment to her father and mother.

“What is your little one’s name?” said a foreigner to a woman, who was walking along with a small child near Amoy.

“It is a girl,” was the reply, as much as to say, “You need not trouble to waste time asking about her.”

“I know, venerable dame,” said the foreigner, “but what is her name?”

“Not Wanted,” was the strange answer.

“You should love your little girl as much as a boy. Why do you speak so unkindly of her?” said the foreigner, thinking that the mother meant she did not want her child. The woman laughed, but said nothing.

“Now tell me her name,” persisted the foreigner, anxious to show interest in the despised girl.

“Not Wanted,” repeated the woman again.

“Not ...” began the stranger once more, meaning to tell the ignorant woman not to speak so unkindly of her little girl.

“Not Wanted is her name,” said the woman quickly, before the foreigner could finish the sentence.

It would be sad indeed to know one was not wanted, but it would be harder still to be reminded of it every time one was called by one’s own name. How would an English girl like to be so treated?[31] “Not Wanted, come and have your hair brushed.” “Not Wanted, where are you?” “Not Wanted, come and play with your little brother,” and so forth. When a baby girl’s fortune, as told by the fortune-tellers, is not a lucky one, she may perhaps be handed over to Buddhist nuns, who will give her rice, potatoes and vegetables, but no fish or meat or eggs. The little one, if she lives to grow up, will serve in the nunnery and help with the worship offered to the idols. When old enough to become a nun she will have her head shaved, till it looks as round as a bullet, and wear tight black trousers, a short blue coat and a close-fitting cap of black cloth; and she will learn to do the fine embroideries, most of which are the work of Buddhist nuns.

Sometimes, when the fortune-teller says a little girl will bring bad luck to her own family, she is given to another household, where she will be brought up to be the wife of one of the sons, when he is old enough to marry. This often happens, but it is not a good plan and leads to unhappiness, as you will hear later on.

The everyday dress of Chinese girls is simple enough. When they first begin to walk they are odd little bundles of clothes, topped by a little jacket and a cloth cap, which covers their head and ears and neck, leaving the face open. When they grow older they wear jackets of cotton,—blue stamped with white flowers is a favourite pattern,—loose coloured trousers and tiny embroidered shoes. They wear ear-rings, silver bangles on their ankles, and sometimes a ring on one finger. When they are engaged to be married, they wear a bangle on one arm. Their hair, which has been worn in a plait behind, is, when they are old enough to be married, put up in a neat coil at the back of the head, and pretty pins and flowers are stuck into[32] it. It is a great day in a girl’s life when her hair is done up in this way.

The first great trial which a Chinese girl has to meet is when she has her feet bound. Her toes are pulled towards the heel, by winding a strip of cotton cloth round them and drawing it tight. Tiny girls of six or seven sometimes have to bear the pain of having their poor little feet pinched together in this way, though eight or nine is the more common age to begin. It must be extremely painful to have the bones twisted and the flesh crushed, until it decays and dries; but when the pain is over, and a girl has ‘golden lilies,’ only two or three inches long, she is very proud of them, and people praise the child’s mother for all the trouble she has taken to make her daughter look so beautiful! So strong is the desire to be admired, that often girls beg to have their feet bound, in spite of all the pain they will have to bear.

Foot-binding, being foreign to Manchu customs, is not allowed in the Palace. Some years ago, the Empress Dowager herself issued an edict to the people saying: “Not to bind is better.” Children brought up in God-fearing homes seldom or never have to suffer the torture of being thus lamed for life. And now, in many parts of China, fathers and mothers, who do not wish their little girls to be crippled, have joined themselves into what is called ‘The Natural Foot Society.’ Let us hope that before long there will be no more foot-binding in China.

Girls brought up in wealthy homes are seldom seen out of doors, but poorer children, at a very early age, have to do something to help to earn their living. They gather firing; they nurse the baby; they cook and sew; they learn to scrape the soot from the bottom of the family rice pot with a hoe; and, in some places,[33] they very early begin to carry loads, slung from a pole on their shoulders. Some sit beside their mothers and help to make paper money to be offered to idols. Some paste rags on a board, one on the top of the other, to be afterwards made into soles for shoes; or they weave coloured tape, or twist fibre into rough string. In some parts of China they make embroidery, working beautiful birds and flowers with their clever fingers. All Chinese girls learn to embroider and make up their own shoes and the embroidered bands which they wear round their distorted ankles. Sometimes they feed silk-worms with mulberry leaves, and afterwards wind the threads off the cocoons which the worms have spun. When a little older some girls may be seen making silver ornaments for women’s hair-pins, but this is work usually done by men and boys; sometimes poor girls, while they are quite young, sell cakes and sweets in the streets, to help their parents; often they spin cotton and weave it into cloth, to make clothes for all the family.

With the exception of a very few daughters of scholars, who were taught to read and write by their fathers, girls used never to be troubled with learning. In spite of this, there are books giving the names of wise and learned women, some of whom, especially in the time of the T’ang Dynasty, wrote famous poems. This shows that ages ago women in China were educated, but as a rule in later days they were left untaught, to learn by slow degrees the ‘three dependencies of woman,’ “who,” as the Chinese say, “depends upon her father when she is young, on her husband when she is older, and upon her son when she is very old.” The story is told of a girl, who used to sing as she toiled at her daily tasks: “Oh, the tea-cup, the tea-cup, the beautiful, beautiful[34] tea-cup”—that was all the song she knew! When Christianity comes, it brings new hope and new songs, and teaches girls and boys alike to know of God and Heaven and a life away beyond the narrow courts of the houses in which the earthly lives of so many Chinese girls are shut up.

As we have seen already, a change has come over China. At the beginning of 1909 there were said to be thirty-seven girls’ schools in Canton alone, one of which had over three hundred pupils, and every year adds to the number of such schools, all over the land. Christian girls teach in these schools. Not long ago a girl refused to become teacher in a Government school because she would not be allowed to read the Bible with the scholars there. Twice she said she would not go, although offered more money each time. At last the authorities said: “We must have you in our school; you may do what you like; you may teach the Bible—only you must come.” Some Christian girls, after leaving school, study in the women’s hospitals and become nurses and doctors. At first they help the missionary lady doctors, and afterwards, in some cases, they earn their living by going out to care for sick women and children. Thus Christianity has opened up a new way by which women may support themselves in China.

When they are tiny little children girls are often engaged to be married and go to live in their future husbands’ homes. They are married, too, when very young. Sometimes a little girl is told only a short time before that she is to be sent away in a great red chair and become somebody’s wife in another home. Poor little thing, she is often very frightened and unwilling to go.

The story of Pink Jade will help you to understand[35] about girls’ marriages in China. The first hint she had of what was going to happen was when an old woman, called the ‘go-between,’ came to her father’s house with a silver bracelet and some hair ornaments for her, as a present from her future husband’s family. A paper stamped with a dragon had already been sent to her parents, giving a description of the young man she was to marry, and a paper stamped with a phœnix, giving a description of herself, had been sent in exchange.

Pink Jade’s father gave her many nice clothes and dresses, five pairs of embroidered shoes, three pairs of red wooden heels, seven pairs of silver finger-rings, bracelets and hair ornaments. These gifts were packed in four red boxes and a dressing-case. Then there was some bedding in a red box, five washing tubs, a wardrobe, a table and two red lanterns. On her wedding-day Pink Jade was dressed in black trousers and petticoat trimmed with embroidery, an embroidered green satin jacket, a beautiful head-band, the gift of her mother-in-law, and many hair ornaments. Before she left her home a thick veil of red and gold, about a foot square, was fastened to her head-band by a few stitches.

A little before noon the great red chair, in which she had been carried by several men, drew near to the bridegroom’s house. The burden-bearers now went on in front with the red boxes and other things, the little bride following behind in her chair, attended by the ‘go-between,’ and four men carrying lanterns.

It was a shy little maiden that entered the new home; then came the ceremony of bride and bridegroom together worshipping heaven and earth, after which they bowed down before the bridegroom’s parents and their ancestral tablets. Some hours later, the husband[36] cut the stitches of the veil, and for the first time saw the face of his bride. She did not see him, however, for she dared not lift her eyes. Crowds of women from among the guests and neighbours came to look at her, saying very freely if they thought the bride pretty or ugly, which it is considered quite polite to do at weddings. Later in the evening she was shown to the men friends of the family, who repeated good wishes in verse, the poor little bride having to stand all the time while this and the other ceremonies were gone through.

On the second day Pink Jade had to cook a meal and wash some clothes, to show she understood her new duties. Her mother and sisters-in-law were pleased with the little bride, so she was happy in her new home. But before very long her husband went abroad, coming back to China only now and then.

When but a little girl of ten years old, Pink Jade had gone with her grandmother to live in a city where there was a Christian church. She was curious to see what happened inside the church, so she went to service there several times; but the singing, reading and praying all seemed strange to her, for she did not understand what they meant. Her husband had also been in church when young, but he did not like the ‘new religion,’ and would have nothing to do with worshipping God.

But it happened that after she was married, Pink Jade took ill and went to the Mission Hospital at Swatow, where she heard about Our Lord Jesus Christ, and how He came to save sinners from their sins. She became so much interested that she persuaded her husband to attend the services in the Hospital chapel, and before long he himself believed in Jesus Christ, and was received into the church by baptism. Pink[37] Jade learned to read and in time gave her heart, too, to God’s service.[4]

Here is a simple rime which girls learn to repeat, so that they may know what to do, when afterwards they go as brides to their new homes.

In China, as in other lands, the Gospel of Our Lord Jesus Christ brings new love and new happiness to girls and women alike. It frees them from being despised and ill-treated, and gives them their true place in the home, for it teaches men that “there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female; for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Chinese children are kept so busy at work or study that a stranger might at first be tempted to think their lives were all work and no play. In time, however, one discovers that they have many kinds of amusements.

A favourite game is played with a ball of tightly[38] wound cotton thread, which is bounced upon the pavement, the player trying to whirl round as often as possible, before giving another pat to make it jump again. Boys are fond of ‘kicking the shuttlecock.’ They are wonderfully clever with their feet, and send the shuttlecock flying from one to another, turning, dodging, leaning this way and that, so as to kick freely. The shuttlecock is kept on the wing for a long time in this way without once falling to the ground. They play tipcat too, but their game is more difficult than ours. ‘Knuckle-bones’ and a guessing game, played with the fingers, like the Italian Mora, are also favourite amusements.

Another game is ‘tiger trap.’ To play it, a number of boys and girls take hands and stand in two lines, facing each other. One waits at the end of the double row of children and bleats, as a kid does in a trap set for Mr Stripes. Then the tiger darts in between the lines to catch the kid. The moment he does so, the children at the ends close up. Unless the tiger bounces out very quickly he is caught and the kid runs away.

There are several kinds of blind man’s buff. One is called ‘Catching fishes in the dark.’ Each child chooses the name of a fish, calling himself dragon-shrimp, squid, red chicken, or some other kind of fish. The boy who is to be ‘he’ is blinded. Then the fishes run past, trying to touch the blind man as they go. If one gets caught ‘he’ must name it rightly. If ‘he’ names the wrong fish, away runs the boy. Another kind is ‘Call the chickens home.’ In this game the blind man says ‘Tsoo, tsoo, come seek your mother,’ then the other children, who are the chickens, run up and try to touch him without being caught. If one is caught he becomes blind man.

[39]When playing ‘Eating fishes’ heads and tails,’ several children take hold of each other’s jackets to form the fish. The first one is the head, which is supposed to be too fierce to be captured; the last one is the tail which may be seized and eaten. One of the players stands by himself. Suddenly he begins to chase the fish, trying to catch its tail. Every time he makes a rush the head of the fish faces round, and the players, forming the tail, swing to one side to avoid being caught, as in our ‘Fox and chickens.’

Kite flying is an amusement of which boys as well as grown men are very fond. Little toddlers begin with tiny kites, cleverly made out of folded paper, but the older boys are more ambitious. Some of their kites are made to look like birds and have a bow, strung with a thin flat strip of bamboo, tied behind the wings. When the bird rises in the wind it hovers like a living thing, and the strip of bamboo buzzes with a loud humming noise. Others are shaped like butterflies, centipedes, and other creatures. One of the most beautiful kites is shaped like a fish, so as to curve and sway in the air, much as a fish does in water.

There are several games played with cash, one in which the coins are thrown into a hole scooped by the roadside; another in which they are struck against a wall, so as to rebound and fall beside a certain mark on the ground, but these, as a rule, are a kind of gambling.

Here are names of some other games which may interest you: ‘Threading the needle’; ‘Waiting for the seeker,’ a game like ‘I spy’; ‘Hopping race’; ‘Let the prince cross over’; ‘Circling the field to catch the rat’; ‘The mud turtle’ and ‘The water demon seeking for a den,’ which is played by five children, but otherwise is like ‘Puss in the corner.[40]’ ‘Sawing wood’ is just ‘Cat’s cradle’ under another name.

The children often play at ‘worshipping the idols.’ For a few cash they buy a painted clay idol, about two inches high, which they carry on a small bamboo stool, by means of two sticks. One child goes in front, one behind, with the ends of the sticks upon their shoulders. Others beat a tiny brass gong and carry a burning stick of incense. Then they offer a shrimp, a small fish and some other things as a sacrifice.

In the warm weather you may be sure that the boys and girls take a large share in the fun when their fathers and brothers send up fire-balloons. These rise in the night sky until they look like yellow moons floating over the city. Sometimes a balloon catches fire, flames for a minute, and then only a falling spark shows where its ashes go tumbling to the ground.

The Chinese have many riddles which grown people as well as children play at guessing.

Here are some for you to try your wits upon.

“It was born in a mountain forest. It died in an earthen chamber. Its soul dispersed to the four winds. And its bones are laid out for sale.”

“In a very small house there live five little girls.”

“On his head he has a helmet. His body is covered with armour. Kill him and you will find no blood, open him and you will find his flesh.”

“On the outside is a stone wall. In the inside there is a small golden lady.”

“It takes away the courage of a demon. Its sound is like that of thunder. It frightens men so that they drop their chopsticks. When one turns one’s head round to look at it, lo! it is all turned into smoke.”

“There are two sisters of equal size; one sits inside, the other outside.”

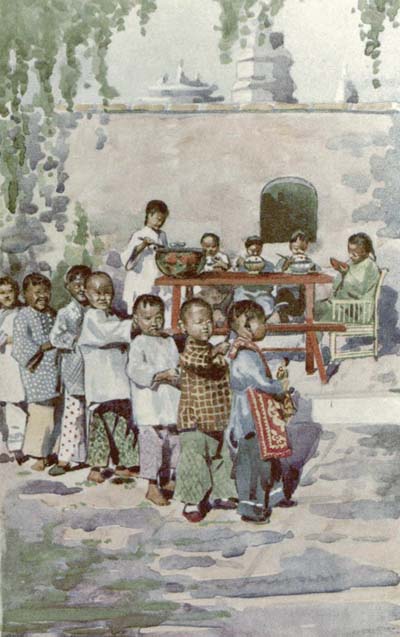

CHILDREN AT FOOD AND AT PLAY

[41]“In the front are five openings; on the sides are two windows; behind hangs an onion stalk.”

“What is it that sits very low and eats more grass than a buffalo?”

Here are the answers: Charcoal, a shoe, a shrimp, an egg, a cannon, a looking-glass, a Chinaman’s head, a Chinese kitchen range (which is generally heated with fern and grass).

Sometimes riddles are painted on lanterns and hung in front of a shop for people to guess: whoever succeeds in guessing right wins a small prize.

Chinese boys and girls have a sweet tooth. Whenever they have cash to do so, they buy sugar-cane, peanut candy and biscuits, some of which are flavoured with sugared kui flowers, which give them a delicious taste. When the man who sells candied peaches and other fruit appears, boys and girls come hopping out of the houses at the sound of his bell, and each one hunts in his little pocket for cash, or begs a few from his mother, to buy some favourite dainty.

The children are filled with glee whenever a feast with plays is given at their home. They are not allowed to sit at the feast, nor are they supposed to look on at the plays, but they have a good share of what is going. As the unfinished dishes are carried from the tables, one after the other, the servants and children have a feast of their own outside. Long before the plays begin, the children watch the erection of the stage in the court or in the street outside the house, and examine the masks and dresses as they are taken out of their boxes and hung up ready for use.

When the music strikes up they choose knowing corners, from which to peep past the shoulders and over the heads of the big people. They love to see the actors dressed like famous heroes who lived long ago,[42] although they cannot recognise the boys now beneath their red and black masks, long beards and rich robes. How the music clamours and the drums beat and the rattles clatter. Warriors shout and stamp, fine ladies wave their fans. When fighting begins upon the stage it would be difficult indeed to catch the boys among the crowd, to send them to bed!

One of the best ways to know boys and girls is to learn something of the stories they like to hear and tell. Here are one or two which will help you to understand our friends the Chinese children much better than pages of talk about their looks and ways.

First, there is the story of how the yellow cow and the water buffalo exchanged their skins. You must know that the yellow cow has a fold of skin which hangs loose beneath her neck, and a loud bellow, while the buffalo has a tight grey skin, that looks some sizes too small for his great round body, and a tiny wheezing voice, which sounds strangely coming from so large a beast. Long ago the buffalo was yellow and his skin fitted well enough, while the cow was grey. Now it happened that one hot day the cow and the buffalo went to bathe in the river, leaving their clothes upon the bank, while they enjoyed themselves in the cool, green water. Presently there was a roar, which told them that the tiger was coming. Out of the water they dashed, and the cow, being the nimbler of the two, scrambled up the bank ahead of the buffalo. In her[43] haste she picked up the first heap of clothes which she came to and began putting them on, hopping into them one leg at a time between the steps as she ran. The buffalo was not far behind, but so frightened lest the tiger should catch him, that he did not notice that the cow had run off with his clothes. He picked up hers and struggled into them somehow, then he ran for his life. He never was very bright, but blown by running and frightened though he was, he soon noticed that his jacket was very tight and that it was the wrong colour. There was the cow running in front of him, and he could see that she had put on his nice yellow suit. He wished her to stop and give him back his clothes, but the tiger was somewhere in the woods not far behind them. So they ran and they ran until at last they were safe from pursuit.

As the cow slowed her pace the buffalo overtook her. Before he had quite made up to her he tried to shout out, “Give me back my clothes,” but he felt so tight and puffed so hard that he could not speak. He was very stiff about the ribs and a little angry, so instead of attempting a long sentence he tried to say, “Oan,” one word only, which means “change.” All he could get out, however, was “Eh-ah, eh-ah,” in a wheezy little voice.

The cow understood his meaning well enough, but she felt so comfortable in her new yellow skin that she only answered “M-ah, m-ah,” “I won’t, I won’t.”

And so the buffalo has been wheezing “Change, change,” and the yellow cow has been mooing “I won’t, I won’t” ever since.

Here is another ‘just-so’ story, which tells how the deer lost his tail. Long ago an old man and his wife lived in a lonely cottage upon a hill not far from forests and rocky places where wild beasts had their holes.

[44]One night, when the man and his wife had finished their supper, they were talking together, as they often did before going to bed. In the course of their talk the old man happened to say: “How happy we are in our cottage upon this hill far from the city where thieves and beggars bother and policemen frighten people. We do not fear thieves nor policemen, nor tigers nor demons, nor anything at all, unless it be the Lio—yes, we need not fear anything but the Lio.”

There was a hush in the cottager’s voice when he spoke the last words, and when he had spoken them, both he and his wife were quiet for quite a long time. Now it chanced that a tiger, which had crept down from his cave under one of the blue peaks of the mountain overhead, was prowling round the cottage whilst they were talking together, hoping to pick up the watch-dog or a fat pig, before setting out for a hunt in the valleys far below. Hearing the sound of voices, he stopped outside the door. The family dog, who was far too wise to be out at night near the edge of the forest, smelt him and crept into the corner of the room furthest from the door, under the bedstead. He dared not growl or whimper. There he lay, his brown hair bristling over his shoulders, and he breathed so quietly that the young mice in their hole by the wall were sure that he was dead, although their little grey mother knew better.

At the moment the tiger began to listen to the talking inside the cottage the old man was saying: “We not do fear thieves nor policemen, nor tigers nor demons, nor anything at all, unless it be the Lio.” There was something in the way he spoke the last words and in the way he stopped after saying them, which showed that he really was afraid of the Lio. The tiger, who had never heard of a Lio, wondered what it[45] could be, so he lay down quietly outside the door to listen, hoping to hear more about the terrible beast which frightened people brave enough to fear neither tigers nor thieves nor demons. All was dark and the hill side was very still. Behind the cottage a thief, who had come to rob the lonely couple, was crouching close to the wall. He too heard the old man talking about the Lio and wondered what the terrible creature could be like. Presently he crept round the side of the cottage. The tiger noticed a sound coming moving through the darkness. It was the thief. Though he slipped along as quietly as a pussy cat the tiger heard him with his wonderful wild-beast’s ears. Dark as it was when the thief crept round to the front wall, he felt, rather than saw, that there was something lying beside the door of the little house. “Good luck!” he thought to himself. “This is the old man’s cow.” It was impossible to see, so he stole up gently to try to find out what the creature might be. He put out his hand to feel, and touched the tiger. In a moment he knew that this was no cow. Its hair was harsh and its muscles like iron bands. Could it be—surely it could not be—the dreadful creature of which he had just been hearing. Reckless as he was, the thief felt his heart stand still. Next moment he jumped to one side, climbed the wall of the cottage, and hid on the roof.

Meantime the tiger, making sure that the unseen thing, which had come upon him in the darkness, was nothing less than the Lio itself, got up and fled. He ran and he ran, until he met a deer in the forest. The deer drew respectfully to the side of the path, as in duty bound when meeting his betters. “Where does his Excellency come from in such a hurry?” he inquired in rather a timid voice.

“Oh! from nowhere, from nowhere at all,”[46] answered the tiger, a little bit confused by what had just happened. Then he recovered himself and told the deer how a terrible beast, called the Lio, had touched him in the dark.

“A Lio, your Excellency! Why, I never even heard of a Lio,” said the deer in great surprise. “What is it like?”

“A Lio is very clever,” said the tiger; “it climbs houses and comes on you in the dark. If you would like to know more about it I will take you to where it is. Come, let us go together.”

“But the Lio will catch me, your Excellency, I am but a weak creature,” said the deer, drawing back a little, for he did not wish to be gobbled up. He never had known the tiger so quiet and polite before, and he could see by the gleam of the great green eyes, even in the dark, that his companion was turning his head every now and then, as if he thought the Lio might come gliding through the forest to spring upon them at any moment.

“Don’t be afraid,” said the tiger, growing braver at the thought of having a companion to go back with him, “I will take care of you.”

“But, your Excellency, the Lio will come and you will run away and leave me to be caught,” answered the deer.

“Oh, no, we can tie our tails together, and then it will be all right,” said the tiger. For you must know that at that time the deer’s tail was much longer than it is now.

“Tie our tails together and both get caught at once,” gasped the deer, so surprised that he forgot to be polite.

“Not at all,” said the tiger, with a little growl in his voice. “When the Lio comes I will ‘put forth my[47] strength’ and pull you away with a whisk before it can get hold of you.”

“Ha! ha! ha!” laughed the deer, his spotted sides shaking until the white marks danced again, “what a clever plan.”

So the deer and the tiger tied their tails together, and set off to look for the Lio. They had to walk carefully through the forest, because the bushes and trees would get between them, and as they went along they talked in whispers about the Lio, until the deer felt creepy all over. At last they reached the edge of the wood, where they could just make out the black cottage looking very dark against the sky. A branch cracked as they passed under the last tree.

The thief, who was still crouching on the roof of the cottage, took fright at the sound, and making sure that the terrible beast he had heard of was coming back, jumped down from the tiles, narrowly missing the deer as he reached the ground.

“Help, help, your Excellency, the Lio!” cried the deer, terrified by something, he knew not what, coming tumbling out of the night. The tiger ‘put forth his strength’ and gave a great spring, when crack! the deer’s tail broke off close by the root. The thief ran, the tiger sprang, the deer bounded away, in different directions, each thinking that the terrible Lio was close at his heels. But the Lio none of them ever saw. What was strangest of all, the old man and his wife, who never had seen a Lio in all their lives, went quietly to bed that night without an idea of what was happening outside in the dark. And now you know why the deer has only a white tuft sticking up, where his beautiful long tail used to be.

The following story about a bird is a favourite one with boys and girls in some parts of China.

[48]There is a little grey bird, called the Bean bird, which pipes a sad note in the spring. Its cry is said to be like the Chinese words for “Little brother, little brother, are you there?” According to the story a man, who had one son, married again and had another little boy. The second son’s mother hated the elder brother and wished very much to get rid of him so that her own child might enjoy the family property. Again and again she did her best to get the poor lad into trouble with his father, and too often she succeeded.

One day in spring when the farmers were busy putting their crops into the ground she found some beans in a flat basket with which the elder brother was going to sow his field. The boy was nowhere to be seen, so she popped his beans into the empty rice boiler, and putting some grass into the fireplace below, heated them until those tiny parts which turn into buds and sprout under the soil were killed. Then she put the beans back into their basket and left them to cool. The boy knew nothing of all this, but the younger son, who dearly loved his elder brother, noticed what had been done, and hoping to save him a scolding, quietly put his own beans into the basket and took the roasted ones to use himself. Then they went to the fields and each one sowed his plot of ground. After a time their mother sent the boys to see how the crops were doing. “If the beans have not sprouted in either of your fields you need not come home again,” said she. “We do not wish to have useless, lazy children in this house.”

The elder brother’s little field was covered with green plants, so he went gleefully home and told his stepmother. The younger brother’s plot was brown and bare, not a bean had come up through the soil. He knew there would be trouble for his brother if he went home, so he started off for the mountains, hoping[49] that his elder brother would be left in peace if he were gone. He wandered away and away, until at length a tiger found him and ate him up.

The stepmother was vexed when her son did not come home from the fields, and with many threats and angry speeches sent the elder boy to go and look for him. The lad, who was anxious to find his companion, went everywhere calling, “Little brother, little brother, are you there?” The workers on the upland farms and the grass-cutters on the hills, heard his voice floating faint and far, as he wandered farther and farther away. Now it was here, now there, always calling the same sad cry, “Little brother, little brother, are you there?”

When he could find him nowhere he knelt down in his despair and prayed Heaven to show him where his brother was. As he prayed and wept he knocked his head upon the ground. His head struck a stone, the blood ran and he died. The blood which flowed from his wound was changed into a little grey bird, and every year, when the beans are sprouting in the fields, the bird comes with its plaintive cry, now near, now far, “Little brother, little brother, are you there?” When the children hear its call they say, “Rain is coming,” and surely enough the drops begin to fall before long, as if the skies remembered an ancient wrong and wept for sorrow.

There are many stories of children famous in China long ago. Here is one which shows how even a little child may care for others, thinking and acting wisely in time of danger.

Many hundreds of years ago, in the time of the Sung Dynasty, a boy named Sze Ma Kung was playing with some other boys and girls. When the fun was at its height, one of the party fell into a great big jar of[50] water. The children were so frightened that they all ran away, except Sze Ma Kung, who at once went to try what he could do to save his companion. The edge of the jar was too high for him to reach over, so the little fellow could not get at the sinking child, to pull him out of the water. There was no time to fetch a stool or call for help; another moment and the prisoner would be drowned. A good idea struck him. He rushed off, and picking up as large a stone as he could carry he dashed it against the side of the jar. Crack went the pot and a great hole opened, through which the water all ran away. Then the child crept out like a half-drowned puppy, but not much the worse for his drenching. When people heard of what Sze Ma Kung had done, they knew that if he lived to grow up he would be a useful man, wise and thoughtful and quick to help others.

Stories are told of children diligent at their books, who were famous in after life. One lad, who was too poor to buy oil for his lamp, used to catch fire-flies and read by the pale-green light they gave. He put the fire-flies inside a tiny muslin bag, which he laid upon the page of his book, the light which they gave being just enough to let him follow his lesson, line by line. Another used to read by the light reflected from snow, as the day failed, or when the moon rose. A third used to fasten his book to the horn of the cow he was tending, so as to use the precious hours for study; while a fourth tied his queue to a rafter of the low roof above his head, so that when he became drowsy and nodded over his lesson, he might be wakened by the pain of having his hair pulled.

Another kind of story helps to fix the written ‘characters’ in schoolboys’ memories. One of these tells how a scholar, called Li An-i, went to visit a rich boor[51] named Ti Shing. When he reached the house and asked for the gentleman, a message was brought that he was not at home. Li An-i knew that this was not true, so he wrote the character for ‘afternoon’ on the door of Mr Ti’s house and went away. When asked why he had done so, he said that the character for afternoon meant ‘the ox not putting out its head.’ When you know that the character for afternoon is the same as the one for ox, but without the dot which makes the head of it, and that a stupid person is called an ox in China, much as he would be called an ass at home, you will understand Mr Li’s joke. He meant that the man, who had not ‘put out his head’ to see him, was a stupid ox.

There are plenty of nursery rimes in China, one or two of which will show you that Chinese children are very much like our own. Here is one about our old friends the sparrows.

Another reminds us a little of the pig that would not get over the stile.

The following verse, which is often shouted by boisterous little scholars, pokes fun at a greedy schoolmaster, who has lost the respect of his pupils. The first and third lines are from the Three Character Classic, the first book a child learns; the others are hits at the master.

The boys and girls of China are learning the stories of Joseph, Samuel and Jonathan, of John the Baptist and of Peter. They read the Pilgrim’s Progress, Jessica’s First Prayer, Christie’s Old Organ and many another favourite, which has been put into the Chinese language for them by the missionaries. Best of all they learn the story of our Lord Jesus Christ, and through it come to know the Blessed Saviour Himself.

It is rather strange that the Chinese have three religions, instead of being contented with one like most people. Confucianism is the chief of these. It takes[53] its name from Confucius, a wise man born in 551 B.C., who taught men to be just, to be kind to one another, and to agree together; but he said little or nothing about how to know God and worship Him. The most famous saying of Confucius is: “What you do not wish done to yourself, do not do to others.” These beautiful words are nearer to the teaching of Our Lord Jesus than any others to be found outside the Bible, and ought to be treasured by everyone. Following in the steps of the earlier teachers of China, Confucius taught children to reverence their parents, and in this way he printed the spirit of the Fifth Commandment upon the entire nation. We must remember, however, that Confucius did not begin what is called Confucianism, he only handed on truths which the early Chinese had learnt. Indeed some things, such as the knowledge of God, and of a future life, he taught less clearly than those who had gone before him.

A story is told which shows that, wise as Confucius was, he did not know everything. One day, when out for a walk he found two boys quarrelling. “What are you two quarrelling about?” asked the great man.

One of the boys answered, “The sun. I say that when the sun has just risen it is nearest to us.”

“I say that it is nearest to us at noon,” insisted the other.

“When the sun rises it looks as big as a chariot wheel. When it is high it is quite small, no larger than a saucer. It is plain that when things are far away they look small, and when they are close to us they look big,” said the first youth.

“When the sun rises,” objected the second boy, “it is chill and cold. When the sun is overhead it is as hot as boiling water. Plainly it is cold when it is[54] far away and hot when it is near, so it is nearer to us at noon than it is in the morning.”

When Confucius had heard each of them in turn, he did not know what to say, so he went on with his walk and left them. Then the two boys laughed, and one of them exclaimed: “Who are the people that say that the Sage of the kingdom of Lo is a wise man?”

While Confucius lived, few of his fellow-countrymen would listen to him. The princes, whom he tried to teach to govern wisely, made him sorrowful by refusing to follow his advice. On the last day of his life he was very sad and dragged himself about, slowly saying over and over again to himself:

But his labours were not lost. His wise words were put into a book by his followers, more than a hundred years after his death. Mencius, the greatest of his disciples, carried on his work. His fame spread all over China and far beyond it. Now there are 1500 temples in which he is worshipped by millions of people, and so great is the honour given to him that his followers say:

Confucius told the Chinese people that the most precious teaching handed down to them from long ago was that which taught them to honour their parents and those older than themselves. But both before and after the time of this great man, the Chinese went too[55] far, not only reverencing, but also worshipping the dead. Perhaps we can imagine how this mistake crept in. They were afraid that they might forget their loved ones. Since it was not the custom with them long ago to put names upon gravestones, they wrote them in books and on slips of wood. These slips of wood, or ancestral tablets, were kept most carefully, as we have already seen, in the chief room of the house and in temples. The Chinese believed that each person had three souls, one which went into the unseen world at death, one which stayed in the grave, and one which lived in the slip of wood. They also thought that the souls in tablets or in graves depended on dutiful sons to offer food and sacrifices to them. Girls might not make these offerings, because, when married, they belonged to their husbands’ families. When parents had no baby boys, they were much troubled, not having anyone to grow up and worship their spirits, for they fear more than anything else to become ‘hungry demons’ after death, with no one to care for their needs. Now you know why Chinese people are anxious to have sons rather than daughters.

Fear mixes with the worship of the dead at every turn. When people are sick or lose money or have some other trouble, they think that the spirits in the tablets are angry, and are bringing evil upon their home. They offer food, and burn paper clothes, houses, money, servants and horses to please them, thinking that when burnt, those things pass into the spirit-land, where their relatives enjoy them, and being pleased, give up troubling those on earth.

A man named Wang had sickness in his family and his business was not good. A priest told him that his father’s spirit, which lived in a red and green[56] tablet, was angry with him, and he must offer paper money, incense and other things to pacify it. He offered these things, and fruit, chickens, cakes and pork besides; but all to no purpose, things went just as badly as ever. At last, after spending all his money in this way, he lost faith in the priest and in the tablet. “My father was not unkind to me when he was alive,” said he, “why should his spirit plague me so wickedly when he is dead?” About this time he first heard the Gospel, and in despair of finding comfort elsewhere, began to go to church. He heard that he had a Father in Heaven, and found peace and gladness in His service. This worship of the spirits of the dead is the real religion of China; all the rest of their beliefs are things added on. The fear of those who have gone into the unseen world hangs like a weight upon the people, who are said to spend millions of money every year in trying to please the spirits of their relatives.

Sad as this is, we ought to remember that there is something beautiful and right hidden beneath all that is wrong in this worship, and that is the desire of the Chinese people to reverence and obey those who have gone before them. When they have learned to serve God, what is wrong will pass away, and perhaps they will teach us all to understand the real meaning of the Fifth Commandment better than we have yet done.

In spite of the good in it, Confucianism has been a failure, because it has not taught men and women and children to know the one true God, who alone can help them to follow the teaching of Confucius and be just and kind and obedient.

Taoism, as it is called, is the second religion of China. Its founder is called Lao-tsze or ‘old boy.’ It is said that he was old and wise and had white hair when he[57] was born. After serving his country for a time, he gave up his post and travelled towards the west. At the frontier pass of Han Kuh, the officer in charge of the gate stopped the traveller, and knowing that he was a wise man, persuaded him to write down some of his teaching in a book. Taoism takes its name from Tao, the truth, or the way, the first syllable in the name of the Tao-teh-king, the famous volume which Lao-tsze wrote; but what is now called Taoism does not follow the teaching of this book.