WILLIAM PENN

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Hugo Oertel

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. MCCLURG & CO.

1911

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1911

Published September, 1911

THE · PLIMPTON · PRESS

[W · D · O]

NORWOOD · MASS · U · S · A

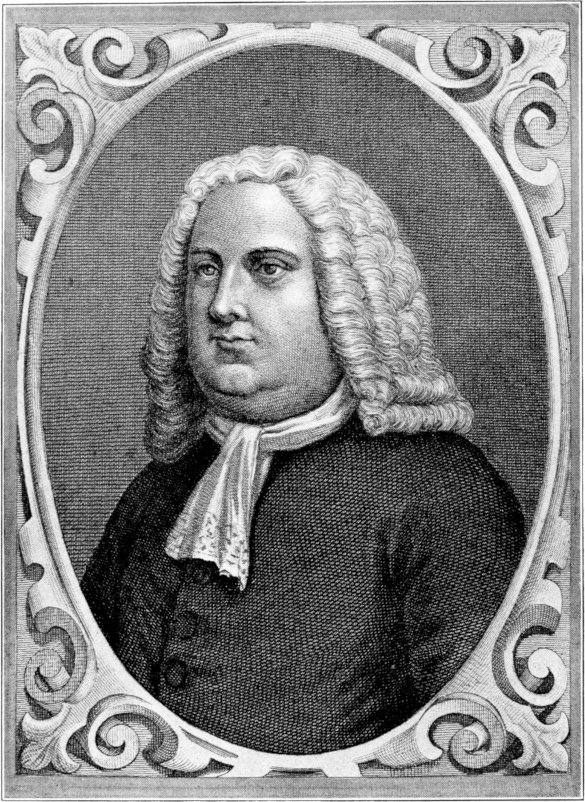

The life of William Penn is one which cannot be too closely studied by American youth, and the German author of this little volume has told its story in most attractive style. Not one of the early settlers of the United States had loftier purpose in view, more exalted ambition, or nobler character. The brotherhood of man was his guiding principle, and in seeking to carry out his purpose he displayed resolute courage, inflexible honesty, and the highest, noblest, and most beautiful traits of character. He encountered numerous obstacles in his great mission—imprisonment and persecution at home, slanders and calumnies of his enemies, intrigues of those who were envious of his success, domestic sorrows, and at last, and most deplorable of all, the ingratitude of the colonists as the settlement grew, and in some cases their enmity. It is a shining example of his lofty character and fair dealing that the Indians, who were always jealous of white men and suspicious of their designs, remained his stanch friends to the end, for he never broke faith with them. His closing days were sad ones, and he died in comparative seclusion, but his name will always be preserved by that of the great commonwealth which bears it and his principles by the name of the metropolis which signifies them. This world would be a better one if there were more William Penns in it.

G. P. U.

Chicago, July, 1911

William Penn was descended from an old English family which, as early as the beginning of the fifteenth century, had settled in the county of Buckinghamshire in the southern part of England, and of which a branch seems later to have moved to the neighboring county of Wiltshire, for in a church in the town of Mintye there is a tablet recording the death of a William Penn in 1591. It was a grandson and namesake of this William Penn, and the father of our hero, however, who first made the family name distinguished. Brought up as a sailor by his father, the captain of a merchantman, with whom he visited not only the principal ports of Spain and Portugal, but also the distant shores of Asia Minor, he afterward entered the service of the government and so distinguished himself that in his twentieth year he was made a captain in the royal navy. In 1643 he married Margaret Jasper, the clever and beautiful daughter of a Rotterdam merchant, and from this time his sole ambition was to make a name for himself and elevate his family to a rank they had not hitherto enjoyed. In this he succeeded, partly by policy, but also unquestionably by natural ability; for although the name of Penn is scarcely enrolled among England’s greatest naval heroes, yet at the early age of twenty-three he had been made a rear-admiral, and two years later was advanced to the rank of vice-admiral—this too at a time when advancement in the English navy could only be obtained by real merit and valuable service.

Penn’s father was also shrewd enough to take advantage of circumstances and turn them to his profit. Although at heart a royalist, he did not scruple to go over to the revolutionists when it became evident that the monarchy must succumb to the power of the justly incensed people and Parliament; and when the head of Charles the First had fallen under the executioner’s axe and Oliver Cromwell had seized the reins of government, Admiral Penn was prompt to offer his homage. Cromwell on his part may have had some justifiable doubts as to the sincerity of this allegiance, but knowing Penn to be an ambitious man of the world, he felt reasonably sure of winning him over completely to the side of the Commonwealth by consulting his interests. He had need of such men just then, for the alliance between England and Holland, which he was endeavoring to bring about, had just been frustrated by the passage by Parliament of the Navigation Act of 1651, requiring that foreign merchandise should be brought to England on English vessels only. This was a direct blow at the flourishing trade hitherto carried on by the Dutch with English ports, and a war with Holland was inevitable. As this must of necessity be a naval war, Cromwell was quite ready to accept the services of so able and experienced an officer as William Penn. The young admiral fully justified the Protector’s confidence, for it was largely owing to his valor that the war, during which ten great naval battles were fought, ended in complete victory for the English.

Scarcely less distinguished were his services in the subsequent war with Spain, when he was given the task of destroying that country’s sovereignty in the West Indies. He conquered the island of Jamaica, which was added to England’s possessions, but was unable to retrieve an unsuccessful attempt of the land forces assisting him to capture the neighboring island of Hispaniola. He had been shrewd enough to make terms with Cromwell before sailing for the West Indies. In compensation for the damages inflicted on his Irish property during the civil war he was granted an indemnity, besides the promise of a valuable estate in Ireland, and the assurance of protection for his family during his absence. It was well for Penn that he did so, for on his return he was summarily deprived of his office and cast into prison—ostensibly for his failure to conquer Hispaniola. The real reason, however, for this action on the part of Cromwell was doubtless due to his knowledge of certain double dealing on the part of Penn, who, shrewdly foreseeing that the English Commonwealth was destined to be short-lived and that on the death of Cromwell the son of the murdered King would doubtless be restored to the throne, had secretly entered into communication with this prince, then living at Cologne on the Rhine, and placed at his disposition the entire fleet under his command. The offer had been declined, it is true, Charles at that time being unable to avail himself of it, but it had reached the ears of Cromwell, who took this means of punishing the admiral’s disloyalty.

That our hero should have been the child of such a father proves the fallacy of the saying, “The apple never falls far from the tree.” His mother, fortunately, was of a very different and far nobler stamp. She seems to have felt no regret at her son’s religious turn of mind, for later, when the father, enraged at his association with the despised Quakers, turned him out of doors, she secretly sympathized with the outcast and supplied him with money.

This son, our William Penn, was born in London on the fourteenth of October, 1644, as his father was floating down the Thames in the battleship of which he had just been placed in command. For his early education he was indebted entirely to his mother, his father’s profession keeping him away from home most of the time. From what is known of her, this must have been of a kind firmly to implant in the child’s heart the seeds of piety, for such a development of spirituality can only be ascribed to impressions received in childhood. William was only eleven at the time of his father’s disgrace, but old enough to understand and share his mother’s distress at the misfortune which fell like a dark shadow across his youthful gayety. Even then the boy may have realized how little real happiness is to be found in a worldly career, and how poor are they whose whole thoughts are centred on the things of this life.

The admiral’s imprisonment did not last long, however. A petition for pardon having been sent to the Protector, he was released and retired with his family to bury his blighted ambitions on the Irish estate near Cork which he had received as a reward for his achievements in the war with Holland. Two more children had been born to them in the meantime, a daughter, Margaret, and a second son, who was named Richard. Here, amid the pleasures and occupations of a country life to which he devoted himself with the greatest zest and enjoyment, young William grew into a slender but stalwart youth. When it became time to consider his higher education, for which there were no suitable opportunities at home, it was decided to send him to Oxford—a plan which was deferred for a time, however, owing to an event which was of more concern to Admiral Penn than his son’s education, since it opened fresh fields for his ambition.

This was the death of Oliver Cromwell on September 3, 1658. The news revived Penn’s still cherished plans for assisting in the restoration of Charles the Second, thereby laying the foundation of a new and brilliant career at the court of the young King, whose favor he had already propitiated by his offer of the fleet. These schemes he did not dare to put into immediate execution for fear of involving himself in fresh troubles, the parliamentary party still being in power and Cromwell’s son Richard chosen as his successor. But no sooner had the latter, realizing his inability to guide affairs with his father’s strong hand, resigned the honor conferred upon him, no sooner was it announced that Parliament had received a message from Charles the Second and was favorably inclined toward his restoration to the throne, than the aspiring admiral lost not a moment in hastening over to Holland to be among the first to offer homage to the new King.

The knighthood which he received from that grateful monarch served only as a spur to still greater zeal in his interests, to which he devoted himself with such success that he not only won over the navy to the royal cause by his influence with its officers, but having accomplished his election to Parliament, was thus able to assist in the decision to recall the exiled sovereign. Again he was among the first to carry this news to Holland, thereby establishing himself still more firmly in the King’s favor. Not till these affairs were settled and a brilliant future assured for himself and his family did Sir William find time to think of his son, who was accordingly sent to Christ Church, Oxford.

The young man must have soon discovered the deficiencies of his previous education and realized that he was far behind other students of his own age, but he applied himself to his studies with such diligence that he made rapid progress and earned the entire approbation of his instructors, while his amiability and kindness of heart, as well as his skill in all sorts of manly sports, made him no less popular with his fellow students. But skilful oarsman, sure shot, and good athlete as he was, he never lost sight of the deeper things of life. Indefatigably as he devoted himself to acquiring not only a thorough knowledge of the classics, but also of several modern languages, so that he was able to converse in French, German, Dutch, and Italian, he showed an even greater fondness for the study of religion. He was especially interested in the writings of the Puritans, which were spread broadcast at this time, glowing with Christian zeal and denouncing the efforts made by the court to introduce Catholic forms and ceremonies into divine worship in the universities as well as elsewhere. Feeling it a matter of conscience to protest against these innovations, Penn, with a number of his fellow students, reluctantly determined to resist the orders of the King, with whom his father stood in such high favor, but whose dissolute life could win neither respect nor loyalty from the earnest and high-minded youth.

About this time there appeared at Oxford a man whom William had already seen as a child and who even then made a deep impression on him. This was Thomas Loe, a follower of Fox, the Quaker whose teachings he was endeavoring to spread throughout the country. He had visited Ireland for this purpose and, doubtless at the suggestion of Sir William’s pious lady, was asked to hold a meeting at their house. The eleven-year-old William never forgot the effect produced by this sermon. Even his father, not usually susceptible to religious feeling, was moved to tears, and the boy thought what a wonderful place the world would be if all were Quakers.

Now that this same Thomas Loe had come to Oxford, what could be more natural than that the young zealot, already roused to opposition and imbued with Puritan ideas, should attend these Quaker meetings with companions of a like mind? Strengthened in his childish impressions and convinced that divine truth was embodied in Loe’s teachings, Penn and his friends refused to attend the established form of service, with its ceremonies, for which they openly expressed their abhorrence and contempt. He was called to account and punished by the college authorities for this and for attending the Quaker meetings, but it only added fuel to the flame. Indignant at this so-called violation of their principles, against the injustice of which they felt it a sacred duty to rebel, they began to hold meetings among themselves for devotional exercises, and only awaited a pretext for open revolt. This was soon furnished by an order from the King prescribing the wearing of collegiate gowns by the students. The young reformers not only refused to wear them, but even went so far as to attack those who did and tear the objectionable garments off from them by force—a proceeding which naturally led to their expulsion after an official examination, during which Penn had spoken boldly and unreservedly in his own and his companions’ defence.

The effect of this on the worldly and ambitious father may easily be imagined. He had looked to his eldest son, on whom he had built such high hopes, to carry on his aspiring schemes after his own death, and totally unable to comprehend how a mere youth could be so carried away by religious enthusiasm, the disgrace of William’s expulsion from the university was a bitter blow to his pride. It was but a cold reception therefore that the young man met with on his return to the paternal roof. For a long time his father refused even to see him, and when he did it was only to overwhelm him with the bitterest reproaches. He sternly commanded him to abandon his absurd religious beliefs and break off all communication with his Oxford associates, and when William respectfully but firmly refused to do this until he should be convinced of their absurdity, the admiral, accustomed as an officer to absolute obedience, flew into such a passion that he seized his cane and ordered his degenerate son out of the house.

On calmer reflection, however, he became convinced of the uselessness of such severity, for William, he discovered, though moping about, dejected and unhappy, was still keeping up a lively correspondence with his Quaker friends, so he resolved to try other methods. Knowing by experience the power of worldly pleasures to divert the mind of youth and drown serious thought in the intoxication of the senses, he determined to resort to this dangerous remedy for his son, whose ideas of life, to his mind, needed a radical change. He therefore arranged for William to join a party of young gentlemen of rank who were about to set out on a tour of the continent, first visiting France and its gay capital, reckoning shrewdly that constant association with young companions so little in sympathy with Quaker ideas and habits would soon convert his son to other views. Or if this perhaps did not fully accomplish the purpose, the allurements of Paris, where King Louis the Fourteenth and his brilliant court set such an example of luxury and licentiousness, could not fail to complete the cure.

Little to young Penn’s taste as was this journey, and especially the society in which he was to make it, he did not care to renew his father’s scarcely cooled anger by opposing it, nor was life at home under existing circumstances especially pleasant or comfortable. He yielded therefore without protest to his father’s wishes and set out for Paris with the companions chosen for him, well provided with letters of introduction which would admit him to the highest circles of French society.

The correctness of the admiral’s judgment proved well founded, and the associations into which he had thrown his son only too well fitted to work the desired change. In spite of his inward resistance young Penn found himself drawn into a whirl of gayety and pleasure for which he soon grew to have more and more fondness and which left him no time for serious thought. He was presented to the King and became a welcome and frequent guest at that dissolute court. The life of license and luxury by which he was surrounded and against which he had almost ceased to struggle failed, however, entirely to subdue his better nature, as the following incident will show.

Returning late one evening from some gathering wearing a sword, as French custom demanded, his way was suddenly stopped by a masked man who ordered him to draw his sword, demanding satisfaction for an injury. In vain Penn protested his innocence of any offence and his ignorance even of the identity of his accuser, but the latter insisted that he should fight, declaring Penn had insulted him by not returning his greeting. The discussion soon attracted a number of auditors, and under penalty of being dubbed a coward by refusing to cross swords with his adversary, Penn was obliged to yield. But if, as is not unlikely, the whole affair was planned by his comrades to force him to use arms, a practice forbidden among the Quakers, the youth who undertook the role of challenger was playing rather a dangerous game; for among his other acquirements Penn had thoroughly mastered the art of fencing and quickly succeeded in disarming his adversary. Instead of pursuing his advantage, however, as the laws of duelling permitted, the spectators were astonished to see him return the rapier with a courtly bow to his discomfited foe and silently withdraw. He might yield to the prevailing custom so far as to draw his sword, but his conscience would not permit him to shed human blood.

THE DUEL

It was with the greatest satisfaction that Sir William learned of the change that had been wrought in his son, and to make it yet more permanent and effectual he ordered him to remain abroad, extending his travels to other countries. He was now in a position to afford this, as through the favor of the King’s brother, the Duke of York, he had received an important and lucrative post in the admiralty, but he would gladly have made any sacrifice to have his son return the kind of man he wished him to be. But the father’s hopes ran too high. Although outwardly become a man of the world, William had by no means lost all serious purpose in the vortex of Parisian life, for he spent some time at Saumur, on the Loire, attracted thither by the fame of Moses Amyrault, a divine, under whose teaching he remained for some time and of whom he became a zealous adherent. From there, by his father’s orders, he travelled through various parts of France and then turned his steps toward Italy in order to become as familiar with the language as he already had with French, and to cultivate his taste in art by a study of the rich treasures of that country.

In 1664 another war broke out between England and Holland, owing to the refusal of the latter to allow the existence of English colonies on the coast of Guinea, where the Dutch had hitherto enjoyed the exclusive trade. Admiral de Ruyter was ordered to destroy these settlements and a declaration of war followed. The Duke of York, then Lord High Admiral of England, believing the services of his friend Admiral Penn indispensable at such a juncture, appointed him to the command of his own flagship with the title of Great Commander. This compelled Sir William to recall young Penn to take charge of the family affairs during his absence. Rumors of Louis the Fourteenth’s favorable disposition toward the Dutch also made him fear for his son’s safety in France. The change wrought in William by his two years’ absence could not fail to delight the admiral. The seriousness of mind which had formerly led him to avoid all worldly pleasures had vanished and was replaced by a youthful vivacity of manner and a ready wit in conversation that were most charming. In appearance too he had improved greatly, having grown into a tall and handsome man, his face marked by an expression of singular sweetness and gentleness, yet full of intelligence and resolution.

To prevent any return to his former habits, his father took pains to keep him surrounded by companions of rank and wealth and amid the associations of a court little behind that of France in the matter of license and extravagance. He also had him entered at Lincoln’s Inn as a student of law, a knowledge of which would be indispensable in the lofty position to which he aspired for his son and heir. And why should not these hopes of future distinction be realized? Was he not in high favor not only with the King, but also with the Duke of York, who must succeed to the throne on the death of Charles? Nevertheless, the admiral must still have had doubts as to the permanence of this unexpected and most welcome change, for when he sailed with the Duke of York in March, 1665, he took William with him, feeling it safest, no doubt, to keep him for a time under his own eye and away from all temptation to relapse into his old ways. These prudent calculations were soon upset, however, for three weeks later, when the first engagement with the Dutch fleet took place, young Penn was sent back by the Duke of York with despatches to the King announcing the victory. As the bearer of these tidings he was naturally made welcome at court and remained in London, continuing his law studies.

Then came the plague, which broke out in London with such violence as to terrify even the most worldly and force upon them the thought of death. Persons seemingly in perfect health would suddenly fall dead in the streets, as many as ten thousand deaths occurring in a single day. All who were able to escape fled from the city, while those who could not get away shut themselves up in their houses, scarcely venturing forth to obtain even the necessities of life. The terrible scenes which met the eye at every turn quickly banished William’s newly acquired worldliness and turned his thoughts once more to serious things. Religious questions absorbed his whole mind and became of far greater importance to him than those of law, with which he should have been occupying himself.

Sir William observed this new change with alarm and displeasure on his return with the fleet, and even more so when his services were rewarded by the King not only by large additions to his Irish estates, but also by promises of still higher preferment in the future. Of what use would these honors be if the son who was to inherit them insisted on embracing a vocation that utterly unfitted him for such a position? Again he cast about for a remedy that should prove as effectual as the sojourn in France had been, and this time he sent his son to the Duke of Ormond, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, whose court, though a gay and brilliant one, was not so profligate as those at Paris and London. The admiral had overlooked one fact, however, in his choice of residence for his son; namely, that there were many Quakers in Ireland.

The letters which he carried procured young Penn an instant welcome to court circles in Dublin, where his attractive person and his cleverness soon made him popular. Again he found himself plunged into a whirl of gayety and pleasure, to which he abandoned himself the more readily as it involved no especial reproach of conscience. Soon after his arrival he volunteered to join an expedition commanded by the Duke’s son, Lord Arran, to reduce some mutinous troops to obedience, and bore himself with so much coolness and courage that the viceroy wrote to Sir William expressing his satisfaction with young Penn’s conduct and proposing that he should embrace a military career, for which he seemed so well adapted. Greatly to William’s disappointment, however, the admiral refused his consent, having other plans for the future. There was also work for him now wherein he could utilize his knowledge of law, some question having arisen as to the title of the large estates recently granted the admiral by Charles the Second. The matter having to be settled by law, William was intrusted by his father with the trial of the case, which he succeeded in winning.

One day while at Cork, near which his father’s property was situated, he recognized in a shopkeeper of whom he was making some purchases one of the women who had been present at that never-to-be-forgotten meeting held at his father’s house by Thomas Loe. Much pleased at thus discovering an old acquaintance, the conversation naturally turned to religious subjects, and on William’s expressing the wish that he might again see and hear the famous preacher, the Quakeress informed him that Loe was then living in Cork and would hold one of his usual meetings the following day. It is needless to say that young Penn was present on that occasion and his Oxford experience was repeated. Loe’s sermon seemed aimed directly at him, for it was on “the faith that overcometh the world and the faith that is overcome by the world.” As the first part of the sermon, wherein the preacher depicted with glowing enthusiasm the splendid fruits of that faith that overcometh, awoke in the young man’s heart memories of the true peace and happiness that had been his so long as he had remained true to his beliefs, so the second part, dealing with the faith that succumbs to worldly temptations, fell like blows upon his conscience. Bitter remorse for his frivolous life of the last few years overwhelmed him, and Loe, to whom he presented himself at the close of the meeting, perceiving his state of mind, did not fail to strengthen the effect of his discourse by the most solemn exhortations.

For a time filial duty and worldly ambition struggled against the voice of awakened conscience, but the latter finally triumphed. Penn now became a regular attendant at the Quaker meetings and belonged, in heart at least, to the persecuted sect. In September, 1667, while present at one of these meetings, usually held with as much secrecy as possible, in order to avoid the jeers of the rabble, the place was suddenly invaded by order of the mayor and all the participants arrested. Finding the son of so distinguished a personage as Sir William Penn among the prisoners, the astonished official offered to release him at once if he would promise not to repeat the offence, but Penn refused to enjoy any advantages over his companions and went with them to prison. While there he wrote to the Earl of Orrery, complaining of the injustice of his imprisonment, since the practice of religious worship could be called neither a criminal offence nor a disturbance of the peace. On receipt of this letter an order was given for his immediate release, but the report that he had joined the Quakers quickly spread, calling forth both derision and indignation among his friends at court.

When this rumor reached the admiral, who feared nothing so much as ridicule, he promptly ordered his son to join him in London. Finding him still in the dress of a gentleman with sword and plume, he felt somewhat reassured and began to hope that after all he might have been misinformed, but the next day, when he took William to task for keeping his hat on in his presence, the youth frankly confessed that he had become a Quaker. Threats and arguments proving alike useless, the admiral then gave him an hour’s time to consider whether he would not at least remove his hat before the King and the Duke of York, that his future prospects and position at court might not be ruined. But William’s resolution had been fully matured during his imprisonment at Cork, and his conversion was a serious matter of conscience. He was forced to admit to himself therefore that such a concession would be a violation of his principles, and announced at the end of the time that it would be impossible for him to comply with his father’s wishes. At this the admiral’s hitherto restrained anger burst all bounds. Infuriated because all his plans and ambitions for the future were baffled by what seemed to him a mere notion, he heaped abuse and reproaches on his son and finally ordered him from the house with threats of disinheritance.

This was a severe test of Penn’s religious convictions. Not only was he passionately devoted to his mother, on whose sympathy and support he could always count, but he also had the deepest respect and regard for his father, in spite of their widely different views, but his conscience demanded the sacrifice and he made it, leaving his home and all his former associations. Now that the die was cast he laid aside his worldly dress and openly professed himself as belonging to the Friends, as they were called, who welcomed him with open arms. It would have fared ill with him, however, accustomed as he was to a life of affluence and ease, had it not been for his mother, who provided him with money from time to time as she found an opportunity.

It was not long, however, before the admiral relented, owing chiefly to her efforts in his behalf, and allowed him to return home, though still refusing to see or hold any communication with him. It must indeed have been a crushing blow to the proud and ambitious man of the world to have his son and heir travelling about the country as a poor preacher, for it was about this time, 1668, that William first began to preach. He also utilized his learning and talents by writing in defence of the new doctrines he had embraced. One of these publications, entitled “The Sandy Foundation Shaken,” attracted much attention. In it he cleverly attempted to prove that certain fundamental doctrines of the established church were contrary to Scripture—a heresy for which the Bishop of London had him imprisoned. Indeed his malicious enemies went so far as to claim that Penn had dropped a letter at the time of his arrest, written by himself and containing treasonable matter, but although his innocence on this point was soon established, he was forced, nevertheless, to remain for nine months in the Tower. Even the King, to whom Sir William appealed on his son’s behalf, did not dare to intervene for fear of increasing the suspicion, in which he already stood, of being an enemy to the church. All he could do was to send the court chaplain to visit Penn and urge him to make amends to the irate Bishop, who was determined he should publicly retract his published statements or end his days in prison. But this the young enthusiast refused to do, replying with the spirit of a martyr that his prison should be his grave before he would renounce his just opinions; that for his conscience he was responsible to no man.

This period of enforced idleness was by no means wasted, however. While at the Tower he wrote “No Cross, No Crown,” perhaps the best known and most popular of all his works, wherein for his own consolation as well as that of his persecuted brethren he explained the need for all true Christians to bear the cross. Another, called “Innocence with her Open Face,” further expounded certain disputed passages in the Holy Book that had shared his imprisonment. The manly firmness and courage with which Penn bore his long confinement without allowing his newly adopted beliefs to be shaken forced universal respect and sympathy and even softened his father’s wrath at last. The admiral himself had been having troubles. False accusations made against him by his enemies had so preyed on his mind that his health had given way, and he had been forced to resign his post in the admiralty and retire to private life. He visited his son several times in prison, and his appeals to the Duke of York finally secured William’s release, without the recantation demanded by the Bishop. Further residence in London at that time being undesirable, however, he went back to his father’s estate in Ireland. Here he labored unceasingly for the liberation of his friends in Cork, who were still languishing in prison, and at last had the joy of seeing his efforts crowned with success by securing their pardon from the Duke of Ormond.

At the end of eight months he returned again to England at the wish of his father, whose rapidly failing health made him long for his eldest son. He had fully relented toward him by this time and a complete reconciliation now took place, greatly to the joy of all parties. But the year 1670, which brought this happiness to Penn, was also one of trial for him, owing to the revival of the law against dissenters, as all who differed from the doctrines of the established church were called, declaring assemblies of more than five persons for religious purposes unlawful and making offenders punishable by heavy fines or even banishment. Among the thousands thus deprived of liberty and property, being at the mercy of the meanest informer, one of the first to suffer was William Penn.

On the fourteenth of August, 1670, the Quakers found their usual place of meeting in London closed and occupied by soldiery. When Penn arrived on the scene with his friend William Mead he attempted to address the assembled crowd, urging them to disperse quietly and offer no resistance, which would be quite useless. But as soon as he began to speak both he and Mead were arrested and taken to prison by warrants from the mayor of London for having attended a proscribed meeting and furthermore caused a disturbance of the peace. The prisoners were tried before a jury on September third. Although the three witnesses brought against them could produce no testimony to confirm the charge, Penn voluntarily confessed that he had intended to preach and claimed it as a sacred right. In spite of all the indignities and abuse permitted by the court, he pleaded his cause so stoutly and so eloquently that the jury pronounced a verdict of not guilty. This was far from pleasing to the judges, who were bent on having Penn punished, so the jury were sent back to reconsider, and when they persisted were locked up for two days without food or water and threatened with starvation unless a verdict were reached which could be accepted by the court. Even this proving ineffectual they were fined for their obstinacy, and refusing to pay these fines were sent to prison, while Penn and his friend Mead, instead of being released, were still kept in confinement for refusing to pay a fine which had been arbitrarily imposed on them for contempt of court.

The admiral, however, whose approaching end made him more and more anxious to have his son at liberty, sent privately and paid both fines, thus securing the release of both prisoners. Penn found his father greatly changed. The once proud and ambitious man had experienced the hollowness of worldly things and longed for death. “I am weary of the world,” he said to William shortly before his death. “I would not live over another day of my life even if it were possible to bring back the past. Its temptations are more terrible than death.” He charged his children, all of whom were gathered about him, “Let nothing tempt you to wrong your conscience; thus shall you find an inward peace that will prove a blessing when evil days befall.”

He talked much with William, who doubtless did not fail to impress upon his dying father the comfort of a firm religious faith, and before he died expressed his entire approval of the simple form of worship adopted by his eldest and favorite son. Sir William died on the sixteenth of September, 1670. Shortly before the end he sent messages to the King and to the Duke of York with the dying request that they would act as guardians to his son, whom he foresaw would stand greatly in need of friends and protectors in the trials to which his faith would expose him. Wealth he would not lack, for the admiral left an estate yielding an annual income of about fifteen hundred pounds, besides a claim on the royal exchequer for fifteen thousand pounds, which sum he had loaned at various times to the King and his brother.

After his father’s death Penn became more absorbed than ever in his chosen mission of spreading the gospel as interpreted by Fox, which seemed to him the only true form of religion. The restraint he had hitherto felt obliged to impose on himself in this respect, out of deference to his father’s prejudices, was now no longer necessary and he was free to follow the dictates of his soul. But he was soon to suffer the consequences of having drawn upon himself the displeasure of the court by his bold defence during the recent trial, and still more by a pamphlet issued soon after his father’s death in which he fearlessly denounced the unjust and arbitrary action of the judges not only toward the accused, but also toward the jury. Just before the new year of 1671 Penn was again arrested on the charge of having held unlawful meetings and was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment at Newgate, during which time he wrote several important works, chiefly urging the necessity of liberty of conscience in England.

After his release Penn made a journey to Holland and Germany, whither many of the Quakers had fled to escape the continual persecutions to which they were subjected in their own country. Others had crossed the ocean to seek in America an abode where they could live without hinderance according to their convictions, and the letters written by these drew large numbers to this land of promise; for in spite of the hardships of the voyage thither, the emigrants drew such glowing pictures of the beauty and fertility of the country and the happiness of enjoying religious worship undisturbed as could not fail to appeal to their unfortunate brethren so sorely in need of this blessing.

During his travels Penn had seen many of these letters and heard the subject of emigration freely discussed, and gradually he formed a plan which indeed had been the dream of his youth, although there had then seemed no prospect of its ever being realized. This plan, however, was forced into the background for a time by an event of more personal importance; namely, his betrothal to Guglielma Maria Springett, daughter of Sir William Springett of Sussex, who had greatly distinguished himself as a colonel in the parliamentary army and died during the civil wars at an early age. His widow and her three children, of whom Guli, the youngest, was born shortly after her father’s death, had retired to the village of Chalfont in Buckinghamshire, where she afterward married Isaac Pennington, one of the most prominent of the early Quakers. It was while visiting Friend Pennington at his home in Chalfont that Penn met and fell in love with the charming Guli, who willingly consented to bestow her hand on this stalwart young friend of her stepfather, whose belief she shared. The marriage took place in 1672 and proved one of lasting happiness on both sides. Conjugal bliss did not divert Penn from his sacred calling, however, for we find him soon on his travels again, with his faithful Guli, who accompanied him everywhere until the birth of their first child made it no longer possible. This was a son, to whom they gave the name of Springett, for his grandfather. But even the joys of fatherhood could not confine Penn to his home, now doubly happy. He travelled about the country constantly, either alone or with other distinguished Friends, and was so active both as a preacher and as a writer that he soon became known as the “sword” of the society.

The year 1673 brought fresh persecutions to the Quakers through the passage by Parliament of the so-called Test Act, excluding all dissenters from holding office of any kind under the crown, which King Charles had been forced to sign, much against his will, since it also applied to Catholics. As the Quakers were looked upon as among the worst enemies of the established church, not only on account of their extreme candor and boldness, but also for their contempt of all outward forms of worship, their day of trial was not long delayed. George Fox was one of the first victims, and in order to secure his release Penn once more made his appearance at court after an interval of five years. His guardian and protector, the Duke of York, received him most graciously, reproached him for his long absence, and promised to use his influence with the King in Fox’s behalf. He also agreed to do all in his power to put an end to the oppressive persecution of the Friends, and dismissed Penn with the assurance that he would be glad to see him at any time or be of any service to him. The promised intercession, however, was either forgotten or without avail, for the merciless enactments against dissenters of all kinds continued as before and filled all the prisons in the country. Little wonder that their thoughts turned to emigration, in which some of their brethren had already taken refuge. For deep-rooted as is the Englishman’s attachment to his native land, even patriotism must yield to that inborn love of freedom and the higher demand of the spirit for liberty of conscience.

To Penn especially this idea appealed with irresistible force now that he had at last given up hope of ever securing these rights in England. But whither? Not in Holland or Germany was to be found the longed-for freedom. Refugees in those countries were scarcely less oppressed and persecuted than at home. It was across the sea that Penn’s thoughts flew, to the silent primeval forests of the New World, where no tyrannical power yet held sway; where every man was the builder of his own fortune and the master of his destiny, unfettered by iron-bound laws and customs; where a still virgin Nature, adorned with all the charms of a favored clime, invited to direct communion with the Creator of all things and inspired a peace of mind impossible to secure elsewhere. There was the place to found the commonwealth of which he had dreamed. All that as a boy he had heard from his father’s lips of that wondrous new Paradise beyond the seas; all that as a youth with his intense longing for freedom his fancy had painted of such an ideal community; all that as a man he had learned from the letters of emigrants who had already reached this land of promise, all this combined to create an inspiring vision that ever unfolded fresh beauties to his mind. And when, in 1676, Penn was unexpectedly brought into actual contact with this country, no doubt it seemed to him like the finger of God pointing out to him the land of his dreams.

In that year Charles the Second, who had already disposed of various English conquests and possessions in North America, made over to his brother James, Duke of York, the province of New Netherlands, ceded to him by the Dutch after their defeat in 1665. This was that fertile tract of country lying between the Delaware and Connecticut Rivers, where the Dutch West Indian Trading Company had already made some settlements. The Duke of York kept only a part of this territory, however; that which was named for him, New York. The territory between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers he gave in fee to two noblemen, Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, the latter of whom, having been formerly governor of the channel island of Jersey lying off the French coast, called his part New Jersey. Both these provinces granted full freedom of government and of belief to all sects—a matter not so much of principle perhaps as of policy, to attract thither victims of the penal laws in England, for the greater the number of colonists who settled in these still sparsely populated territories, the more their value and their revenues would increase. Nor were these calculations unfounded. Hundreds of Puritans, among whom were many Quakers, took advantage of this opportunity to seek new homes, and their industry and perseverance soon brought the land to a state of most promising productiveness. Finding the care of these distant possessions burdensome, however, Lord Berkeley sold his share for a thousand pounds to one Edward Billing through his agent John Fenwick. Some dispute concerning the matter having arisen between these two men, both of whom were Quakers, Penn was chosen to settle the controversy and decided in favor of Fenwick, who had emigrated with a large party of Friends to the coast of Delaware and founded the town of Salem.

Penn’s connection with the American province did not end here. Billing, having become embarrassed in his affairs, was forced to resign his interest in the territory to his creditors, who at his request appointed Penn as one of the administrators. This office, though not altogether agreeable to him, he felt obliged to accept in the interest of the many Quakers already settled there; but if his model community were to be founded there, he must have a free hand and not be hampered by any regulations or restrictions which might be made by Sir George Carteret as joint owner of the province of New Jersey. He therefore directed his efforts to securing a division of the territory, in which he finally succeeded, Carteret taking the eastern part, while the western, being sold to the highest bidder for the benefit of Billing’s creditors, came into the sole possession of the Quakers.

For this new State of West New Jersey, Penn drew up a constitution, the chief provision of which was the right of free worship and liberty of conscience. The legislative power was placed almost entirely in the hands of the people, to be exercised by chosen representatives, while all matters of law and justice were intrusted to a judiciary the members of which were to serve for a period of not more than two years. Copies of this constitution were printed and widely circulated among the Quakers, together with a full description of the soil, climate, and natural products of the new colony. The result was amazing. Penn’s home, then at Worminghurst in Sussex, was literally besieged by would-be emigrants seeking for information, in spite of the fact that in these published pamphlets he had strongly urged that no one should leave his native land without sufficient cause and not merely from idle curiosity or love of gain. Two companies were now organized to assist in the work of emigration. The first ship carried over two hundred and thirty colonists, and two others soon following, it became necessary to establish at once a provisional government, consisting of Penn himself with three other members chosen from the two companies.

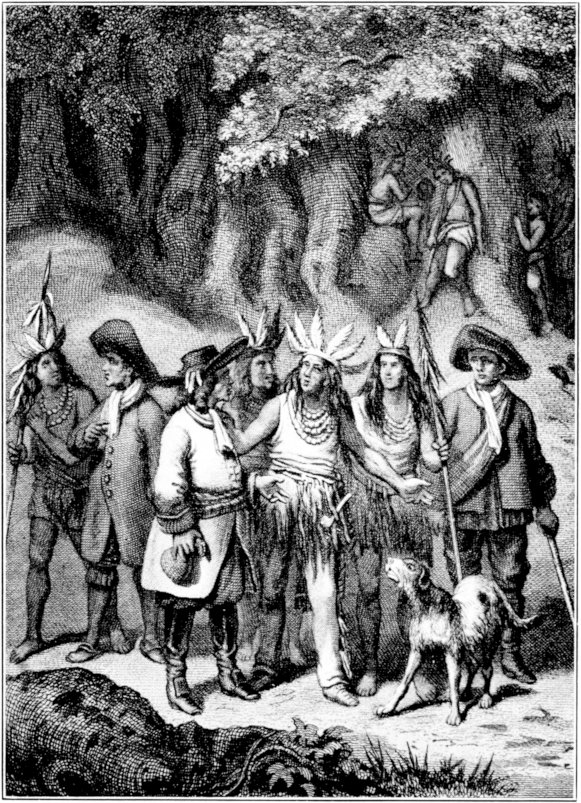

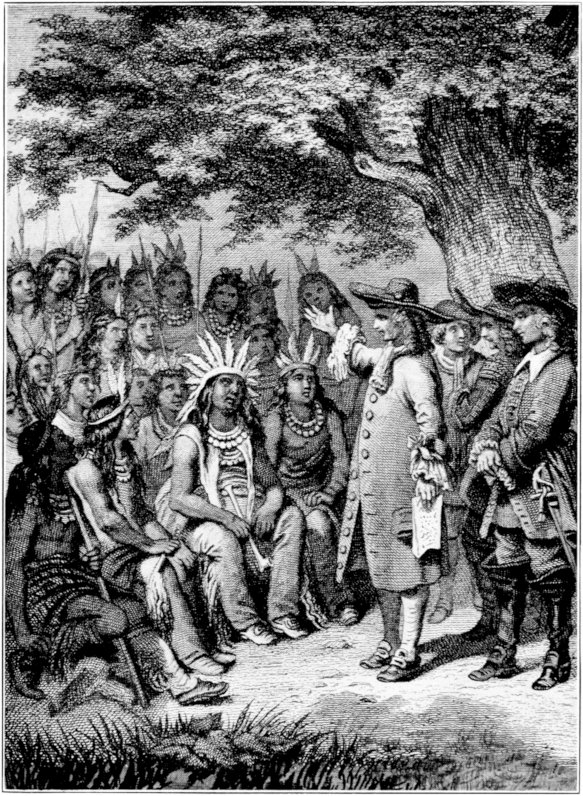

One of the first acts of the settlers, after safe arrival in the New World, was to arrive at an amicable understanding with the native tribes by paying them a good price for the land they had occupied or claimed for their hunting grounds. This was quite a new experience to the Indians, who had hitherto met with only violence and robbery from the white men—treatment for which they had usually taken bloody revenge. They willingly consented, therefore, to bargain with these peaceful strangers, so different from any they had yet seen. “You are our brothers,” they declared in their broken English,” and we will live with you as brothers. There shall be a broad path on which you and we will travel together. If an Englishman falls asleep on this pathway the Indian shall go softly by and say, ‘He sleeps, disturb him not!’ The path shall be made smooth that no foot may stumble upon it.”

It was no small advantage to these early settlers, struggling against hardships and privations to make a home in the wilderness, to be at peace with the natives and have nothing to fear from their enmity. Often indeed, when threatened with want or danger, they were supplied with the necessities of life by the grateful Indians, who knew how to value the friendship and honesty of their new neighbors.

Thus West New Jersey bade fair to develop into a favorable place for Penn to found that ideal Commonwealth of which he had so long dreamed. But in the preoccupations of this new enterprise Penn did not lose sight of the duties that lay nearest to him. Hearing that the Friends he had formerly visited in Holland and Germany were anxious to learn from his own lips of the settlement in New Jersey, he decided to make another journey to those countries, the more so as it was important to secure for the new colony as many as possible of the German artisans, who at that time held a high reputation for skill and industry.

Penn was also especially desirous of making the acquaintance of a noble lady whom Robert Barclay had first interested in the Quakers and whose influence would be of the utmost importance to the members of that persecuted sect in Germany. This was the Princess Elizabeth of the Rhine, daughter of the Elector Palatine Frederick the Fifth, afterward King of Bohemia. She was closely connected with England, her mother having been a daughter of King James the First, and was deeply interested, therefore, in all that concerned that country. At this time she was living at Herford in Westphalia and was distinguished not only for her learning, but still more for the benevolence and sincere piety that made her the friend and protectress of all persecuted Christians of whatever sect. She had learned from Robert Barclay to feel the greatest respect and admiration for the Quaker form of belief, and much was hoped from her protection.

In 1677, therefore, Penn again sailed for Holland with George Fox, Robert Barclay, and George Keith, all prominent members of the Society of Friends, in a vessel the captain of which had served under Admiral Penn. Rotterdam, Leyden, Haarlem, and Amsterdam were visited in succession and large meetings held, there being many Quakers in each of these cities. At Amsterdam George Fox was left behind to attend a general assembly or conclave, where questions of importance to the Society were to be settled, while Penn and his other two companions went on to Herford. They were most kindly received by the Princess Elizabeth, who not only permitted them to hold several public meetings, but also invited them frequently to her own apartments for religious converse, owing to which she finally became a member of the sect herself.

Robert Barclay now returned to Amsterdam to join Fox, but Penn, accompanied by Keith, who was almost as proficient as himself in the German language, journeyed on by way of Paderborn and Cassel to Frankfort-on-the-Main, where Penn preached with great effect, winning over many influential persons to his own belief. From Frankfort the two Quaker apostles went up along the Rhine to Griesheim near Worms, where a small Quaker community had been formed. Here Penn’s plan for founding a trans-atlantic State for the free worship of their religion was received with the greatest enthusiasm, and large numbers did indeed afterward emigrate to New Jersey, where they took an important place in the colony, being among the first to condemn and abolish the slavery then existing in America, and established a reputation for German worth and integrity beyond the seas.

On his return to Cologne, Penn found a letter from the Princess Elizabeth urging him to go to Mühlheim to visit the Countess of Falkenstein, of whose piety she had already told him. In endeavoring to carry out this request of his royal patroness, however, Penn and his friend met with a misadventure. At the gates of the castle they encountered the Countess’ father, a rough, harsh man with small respect for religion of any sort. He roundly abused them for not taking off their hats to him, and on learning that they were Quakers, he had them taken into custody and escorted beyond the boundaries of his estates by a guard. Here they were left alone in the darkness, at the edge of a great forest, not knowing where they were or which way to turn. After much wandering about they finally reached the town of Duisburg, but the gates were closed and in spite of the lateness of the season they were forced to remain outside till morning.

From Amsterdam Penn went to join Fox again at Friesland, improving this opportunity to make another satisfactory visit to Herford, and parting from the noble Princess as a warm friend with whom he afterward enjoyed a frequent correspondence. Not till early in the winter did the four friends return to England, and the stormy passage, together with his nocturnal adventure at Duisburg, so affected Penn’s health that for some time he was obliged to submit himself to the care of his devoted wife, especially as the importunities of prospective emigrants gave him little chance to recuperate.

The year 1678 seemingly opened with brighter prospects for those who had suffered so severely in the past for their religious beliefs. The clearest sighted members of Parliament must have realized the detriment to England when such numbers of peaceable citizens, blameless in every respect save for their form of worship, were forced to abandon their native land, taking with them their possessions and their industries, and must have realized that such persecutions must end.

Penn, in spite of being a Quaker, had won the esteem of all classes by his high character and his ability and enjoyed the confidence of some of the most influential personages in the kingdom. Hearing of this change of attitude adopted by Parliament, he laid aside for the time being all thoughts of his transatlantic commonwealth and gave himself up to the work of securing recognition of his great principle of liberty of conscience. Profiting by the favor in which he stood with the Duke of York, he endeavored to obtain through him the submission to Parliament of an Act of Toleration. The Duke looked favorably on the plan, but being himself a member of the Church of Rome, maintained that such a law should not be restricted to Protestant dissenters only, but apply also to Catholics. All seemed to be going well and Penn’s efforts bade fair to be crowned with success, when suddenly an event occurred which deferred for years the passage of this act and added fresh fuel to the fires of persecution. This was the invention of the famous Popish Plot by an infamous wretch named Titus Oates. Formerly a clergyman in the Anglican Church, he had been deprived of his living because of his shameful excesses and fled to Spain, where he joined the Jesuits. Expelled from this order also for improper conduct, he revenged himself by turning informer and swore to the existence of a conspiracy among the Jesuits to massacre all the prominent Protestants and establish the Catholic religion in England. Even the King, for permitting the persecution of Catholics in his kingdom, was not to be spared, nor the Duke of York, who was not credited with much real devotion to that faith.

It is doubtful whether there ever was any real foundation for this atrocious charge based by Oates upon letters and papers intrusted to him by the Jesuits and which he had opened from curiosity. Nevertheless the story was generally credited in spite of the absurdity of the statements of such a worthless wretch, and aroused the wildest excitement throughout the country, in consequence of which the established church, alarmed for its safety, enforced more rigorously than ever the edicts against all dissenters. Seeing his hopes of religious freedom in England once more fading, Penn bent his efforts the more resolutely toward the establishment of a haven in America. He had long ago decided the principles by which his new commonwealth was to be governed; namely, the equality of all men in the eyes of the law, full liberty of conscience and the free worship of religion, self-government by the people, and the inviolability of personal liberty as well as of personal property—a form of government which, if justly and conscientiously carried out, must create indeed an ideal community such as the world had never yet seen. Nor was it an impossibility, as was proved by the gratifying success of the New Jersey colony, where a part of these principles, at least, had already been put into practice.

But where was this model State to be founded? It must be on virgin soil, where no government of any kind already existed, and where the new ideas could be instituted from the beginning. As the most suitable spot for this purpose Penn’s glance had fixed upon a tract of land lying west of New Jersey and north of the royal province of Maryland, which had been founded in 1632 by a Catholic nobleman, Lord Baltimore, as a refuge for persecuted members of his own faith, but which also offered liberty to those of other sects. The only occupants of this territory were a few scattered Dutch and Swedish settlers, but they were so small in number and so widely separated that they need scarcely be taken into consideration as possible obstacles to Penn’s plans after the arrival of the class of colonists he favored in numbers sufficient to populate this wide extent of land. For the rest the country was still an unbroken wilderness, where one could wander for days hearing no sound but the songs of the countless birds that filled the vast forests. As to the natives, in spite of their undeniable cruelty and savage cunning when provoked or wronged, it was quite possible to make friends and allies of them by kindness and fair treatment, as the New Jersey settlers had already learned.

This was the territory of which Penn now determined to secure possession if possible, a task which promised no great difficulty, as the English crown claimed sovereignty over all that portion of North America lying between the thirty-fourth and the forty-fifth degrees north latitude, on the strength of the discovery of its coast line by English navigators. King James the First had given a patent for part of these possessions to an English company, the grant including all the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and some attempt had been made to found colonies and develop the riches of the country, but later this company was divided into two, one taking the northern portion, the other the southern. This latter, called the London Company, lost no time in fitting up a ship which entered Chesapeake Bay in 1607, sailed up the James River, and landed its passengers at what was afterward called Jamestown, the first English colony in America. These colonists were soon followed by others, and by the year 1621 the settlement had so increased that the London Company, which had retained the right of ownership, exercised through a governor, granted a written constitution to the province, which they named Virginia. In 1624, however, this company, having some disagreement with King James, was dissolved and Virginia became the property of the crown. This being followed by the voluntary withdrawal of the parties owning the northern half of the territory, the tract between the fortieth and forty-eighth degrees, known as New England, was then deeded by James to the Plymouth Company, which made no attempt at colonization itself, but sold land to others, part of which thus came into possession of the Puritan emigrants.

In 1639, however, during the reign of Charles the First, their charter expired and the lands still belonging to them, including what were afterward the States of Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey, again reverted to the crown. The district lying between the Delaware and Hudson Rivers had been claimed by the Dutch—Hudson, the English navigator who discovered it, having been then in the service of Holland; and here between Delaware Bay and the Connecticut River they had founded their colony of New Netherlands. In 1655 the adjoining territory on the west bank of the Delaware, comprising the present State of Delaware and the southern part of Pennsylvania, had been bought from the Indians by a Swedish trading company at the instigation of King Gustavus Adolphus and a settlement founded under the name of New Sweden. Not proving the commercial success hoped for, this was afterward abandoned. England’s acquisition of New Netherlands as the prize of her naval victories over Holland, the formation of the colonies of New York and New Jersey, the possession of the latter by the Quakers and the drafting of its constitution by William Penn,—all these have been related in the preceding chapter.

The territory which Penn now had in mind, therefore, had belonged to the crown since the dissolution of the Plymouth Company and was again at the disposal of the King. As to Penn’s confidence in his ability to obtain possession of it without difficulty, it will be remembered that he had inherited from his father a claim of fifteen thousand pounds against the royal exchequer. As neither the King nor the Duke of York were able to repay this sum, the unpaid interest on which, during the ten years since the admiral’s death, amounted to more than a thousand pounds, Penn felt sure the King would welcome a proposal to cede this tract of land in America as payment of his claim—certainly a simple method of releasing himself from this large debt.

But the affair was not to be so easily settled after all, for the time was past when the sovereign had absolute power to dispose of crown possessions as he would, the privy council now having a voice in the matter, and to obtain their consent was difficult, Penn’s ideas in regard to the government of this new State being regarded not only as preposterous, but also as dangerous to itself and to the crown. He was urged, therefore, by his friends to make no mention of his real purpose in his petition to the King, lest he be forced to renounce his long-cherished plan. Although he accepted this prudent advice, there were still many obstacles to overcome, owing to the difficulty of defining any exact boundaries in that trackless wilderness and the precautions necessary to incorporate in the patent all possible security for the maintenance of crown prerogatives.

While the matter was still before the council and the result by no means certain, Penn took advantage of an opportunity which offered itself of becoming a joint owner of New Jersey, by which, even should his petition be refused, his plans could still be carried out in that province, if only on a small scale. Sir George Carteret, tired of his colonial possessions, offered to sell his ownership, and Penn, with a number of others, concluded the purchase. Again the public confidence in him and his enterprises was shown by the haste with which hundreds of families, especially from Scotland, took advantage of the liberal terms offered to emigrants in his published prospectus and enrolled their names as future colonists. At length, after much deliberation, and owing largely to the influence of the Duke of York, to whom Penn had again applied for assistance, the council agreed to comply with his proposal, partly also, perhaps, from the fear that in case they refused Penn might insist upon the payment of his debt, for which at the moment no means were available.

On the twenty-fourth of February, 1681, the King signed the deed granting to Penn the absolute ownership of all that territory extending from the Delaware River to Ohio on the west and as far as Lake Erie on the north, covering an area equal to the whole of England, and the fifth of March, at a special meeting of the privy council, this patent was delivered to Penn in the presence of the King. As evidence of His Majesty’s high good-humor on this occasion, a popular anecdote is told. As Penn, according to the Quaker custom, neither took off his hat on the King’s entrance nor made the usual obeisance, Charles quietly removed his own hat, although it was the royal prerogative to remain covered on entering an assembly of any kind. To Penn’s astonished query as to the reason for this unusual proceeding he replied smilingly, “It is the custom at court for only one person to remain covered.”

Another proof of the King’s satisfaction at thus being freed from his indebtedness to Penn was shown in choosing a name for the new province. Penn at first suggested New Wales, on account of the mountainous character of the country, but one of the councillors, who was a Welshman and none too well disposed toward the Friends, objected to the idea of giving the name of his native land to an American Quaker colony. His new domain being as thickly wooded as it was hilly, Penn then proposed Sylvania, which met with general approval, the King, however, insisting that Penn’s own name should be placed before it, making Pennsylvania or “Penn’s woodland.” In vain he protested that this would be looked on as vanity in him. Charles would hear of no denial, declaring good-naturedly that he would take the whole responsibility on himself. The name of Pennsylvania was inserted in the patent, and Pennsylvania it remained.

This document is still in existence, carefully preserved among the State archives. It is written in old English script on a roll of stout parchment, each line underscored with red ink and the margins adorned with drawings, the first page bearing the head of King Charles the Second. It was a proud and joyful moment for Penn when he received this deed from the King’s hand, marking the first and most important step toward the realization of his dreams. “It is a gift from God,” he declared reverently. “He will bless it and make it the seed of a great nation.”

The patent conferred upon the new owner the right to divide the province into counties and municipalities; to incorporate towns and boroughs; to make laws with the people’s consent; to impose taxes for public purposes; to muster troops for the defence of the State, and to execute the death sentence according to martial law—all on condition that no laws should be made in opposition to those existing in England, that the royal impost on all articles of commerce should be lawfully paid and allegiance to the crown duly observed. In case of failure to comply with these conditions the King reserved the right to assume control of Pennsylvania in his own person until he should be indemnified to the full value of the land. Parliament also reserved the right to impose taxes on the colonists. By the express desire of the Bishop of London it was stipulated that should twenty or more of the inhabitants of the province desire the services of a clergyman of the established church, he should be permitted to dwell among them unmolested. Lastly, Penn, the owner, in recognition that the land was held in fee of the English crown, was to pay an annual tribute to the King of England of two bear-skins, with the fifth part of all gold and silver found in Pennsylvania at any time.

Penn set to work at once upon the task of drawing up a constitution for his new colony, “with reverence before God and good-will toward men,” as he states in the introduction to this instrument. The sovereign power was to be exercised by the governor, Penn himself, jointly with the citizens of the commonwealth. For legislative purposes a council of seventy-two was to be chosen by the people, one-third of which number was to retire at the end of every year and be replaced by others selected in the same way. This council was to frame laws and superintend their execution; to maintain the peace and security of the province; to promote commerce by the building of roads, trading posts, and harbors; to regulate the finances; to establish schools and courts of justice and generally do all that should be required to promote the welfare of the colony. The only prerogative claimed by Penn for himself was that he and his lawful heirs and successors should remain at the head of this council and have the right of three votes instead of one.

In addition to the council of state there was to be an assembly which at first was to include all free citizens of the State, but later, when their number became too large, to consist of not more than five hundred members, to be chosen annually. All laws made by the council must be submitted for approval or rejection to this assembly, which also had the right to select candidates for public offices, of whom at least half must be accepted by the governor.

These were the outlines of Penn’s masterly scheme of government, to which were added some forty provisional laws to remain in force until such time as a council of state could be chosen. These included entire freedom of religious belief and worship, any molester of which was to be punished as a disturber of the peace, and the prohibition of all theatrical performances, games of chance, drinking bouts, sports that involved bloodshed or the torture of animals—all, in short, that could encourage cruelty, idleness, or godlessness. Prisoners must work to earn their support. Thieves must refund double the amount stolen or work in prison until the sum was made up, and all children above the age of twelve years must be taught some useful trade or occupation to prevent idleness. Many of these provisional laws and regulations have remained permanently in force in Pennsylvania, the council being unable to substitute anything better, and their wisdom has been amply proved by the experience of more than two hundred years.

This newly acquired territory, which was henceforth to absorb all Penn’s attention, lay to the north of Maryland and west of New Jersey, of which Penn was now joint owner, reaching from the Delaware River on the east to the Ohio on the west, and north as far as Lake Erie. The eastern and western boundaries were well defined by these two rivers, but on the north and south the lines had yet to be agreed upon with the owners of the adjoining colonies—no easy matter where the land was largely primeval forest, untrodden by human foot save for the Indians who traversed it on their hunting expeditions. The greater part of the tract was occupied by the various ranges of the Allegheny Mountains, whose bare rocky peaks offered no very inviting prospect and held out few hopes as to a favorable climate. But wherever trees could find nourishment for their roots, dense forests extended, untouched as yet by any axe, while verdant meadows lined the countless streams that descended from the mountain heights to empty their waters into the Allegheny and Susquehanna Rivers which flowed through the middle of the State. The only outlet to the ocean was through the Delaware River, which opened into Delaware Bay, where there was a good harbor.

The climate of the country was a diversified one. While in the mountain regions the winters were severe, the eastern slopes toward the Atlantic Ocean, as well as those in the northwest toward the Ohio River and Lake Erie, enjoyed a temperate climate with often great heat in the summer. In these regions the soil was rich and fruitful, promising bountiful returns to the settler after he had once succeeded in clearing the land and making room for the plough. The forests, almost impenetrable in places with masses of sumach bushes and climbing vines, furnished almost every kind of wood already known to the English colonists: cedar, cypress, pine, and sycamore, as well as the full-blooming tulip tree, which flourished in sheltered spots. Game of all sorts abounded and the streams were full of fish. The most delicious grapes and peaches, chestnuts and mulberries grew wild in protected places, and flowers of tropical gorgeousness greeted the eyes of astonished settlers. The gold and silver of which King Charles had been so careful to reserve a share were not found in the province, but there was plenty of iron and an inexhaustible supply of the finest coal. Also there were valuable salt springs, as well as those useful materials, lime, slate, and building stone. In short, it was a country well fitted to supply every need of the settler and offering magnificent prospects for the future.

To be sure, it was inhabited by several tribes of Indians, chief of which were the Lenni Lennapes in the southern part and the Iroquois in the northern, but if they were disposed at first to regard with suspicion this invasion of their domains, they soon found the newcomers fair and honest in their dealings with them and willing to pay for the right to settle there, like the New Jersey colonists. Indeed these semi-savage natives seemed to place little value on the permanent possession of the land over which they claimed sovereignty. They had no fixed abiding place, but roamed about at will, settling down for a time where the hunting was especially good or the streams promised to fill their nets with fish. So long as they were free to hunt and fish as they chose and their women had a small piece of open ground in which to prepare the maize cakes that served them for bread, no hostile attacks were to be feared from them.

Penn himself little suspected that he had received an empire in exchange for his claim against the crown, nor did he realize as long as he lived the full value of his newly acquired territory. The idea of enriching himself or his family was as far from his thoughts as it had been close to his father’s. With him it was purely a question of obtaining a home for his ideal Commonwealth, and he refused all the offers to purchase rights of trade there that poured in upon him as soon as the patent had been granted, even though he was in great need of money at the time and although the sale of such rights was not only perfectly legitimate, but no more than any other in his position would have done without hesitation. One merchant, for instance, offered him six thousand pounds, besides two and a half per cent of the yearly profits, for the exclusive right to trade in beaver hats between the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers. Penn was resolved that trade in his colony should be no more restricted than personal liberty or freedom of conscience, and the more widely his principles of government became known, the larger grew the number of would-be emigrants who wished to settle there. He soon found himself so overrun with agents wishing to consult him as to the sale of lands or the formation of trading companies that he scarcely knew which way to turn. There was hardly a city in the three kingdoms that did not send messengers or petitions, while offers came even from Holland and Germany, where Penn was so well known.

Emigration companies were also formed for the foundation of settlements on a larger scale. To one of these, in Frankfort-on-the-Main, Penn deeded a tract of fifteen thousand acres along the banks of a navigable river, with three hundred acres in the interior on which to found the capital of the new State. A trading company in Bristol concluded a contract for the purchase of twenty thousand acres and set to work at once to fit out a ship, while in London, Liverpool, and Bristol emigrants gathered in such numbers that Penn soon had no fear as to the settlement of his colony. Among these, it is true, were many adventurers in search of a fortune only, which they hoped to make more quickly and easily under Penn’s form of government than elsewhere. But by far the greater number were victims of oppression, seeking to escape the endless persecutions to which they were subjected at home on account of their religious opinions, and taking with them little but good resolution and a pair of useful hands.

Immediately on receiving the patent Penn despatched his cousin, Colonel Markham, with three ships to take possession of the new province in his name, to arrange with Lord Baltimore as to the doubtful boundary lines on the south, and above all to make friends with the Indians by concluding a formal treaty with them for the purchase of such lands as they laid claim to. The kindliness of his nature made it impossible for him to treat the unfortunate natives as other Europeans had done, driving them ruthlessly from their own hunting grounds wherever the land was worth taking possession of and forcing them as far as possible into slavery. The Spanish explorers especially, in their insatiable thirst for gold, had even robbed them of all the precious metals and pearls they had and endeavored by the most shameful cruelty to extort from them knowledge of the location where they found the gold of which their ornaments were made. If they offered the slightest resistance or took up arms to defend themselves or regain their liberty, they were hunted like wild beasts by bloodhounds trained for that purpose, or fell in heaps before the murderous bullets against which their arrows were of no avail. Even the Puritan settlers of New England, who should have practised the Christian virtues of justice and humanity, were guilty of many acts of cruelty and treachery toward the red men, with whom they were perpetually at warfare in consequence.

Penn hoped, by the use of gentler methods, to win the confidence of the Indians, who must have already discovered from the New Jersey settlers that all white men were by no means like those with whom they had first come in contact. It was necessary, in fact, if his colony were to enjoy permanent peace and security, and in spite of the ridicule which such humane ideas was likely to evoke, Markham was charged with the strictest instructions in this regard. He was a bold and determined man, devoted to his kinsman Penn, the wisdom and purity of whose ideas he fully appreciated in spite of his soldierly training. On his arrival in Pennsylvania he lost no time in concluding a treaty with the chiefs or sachems of the principal tribes, conveying to Penn for a fixed sum all lands claimed by them with the solemn assurance in his name that no settler should ever molest or injure them. The next two ships which came over from England brought three agents authorized to make further treaties of peace and friendship, thus strengthening the work begun by Markham, and also an address written by Penn himself to be read to the Indians, expressing it as his earnest wish “by their favor and consent, so to govern the land that they might always live together as friends and allies.”