Transcriber's Notes

This text is based on what is called the Grub Street edition of the One Thousand and One Nights, that first appeared in London in 1706. It was translated indirectly by anonymous translator(s) from the French translation of Antoine Galland titled Les mille et une nuits.

The table of contents was moved from the end of the book to the beginning to better suit the ebook format.

Footnotes appearing throughout the text were numbered sequentially and collected at the end of the ebook under Footnotes.

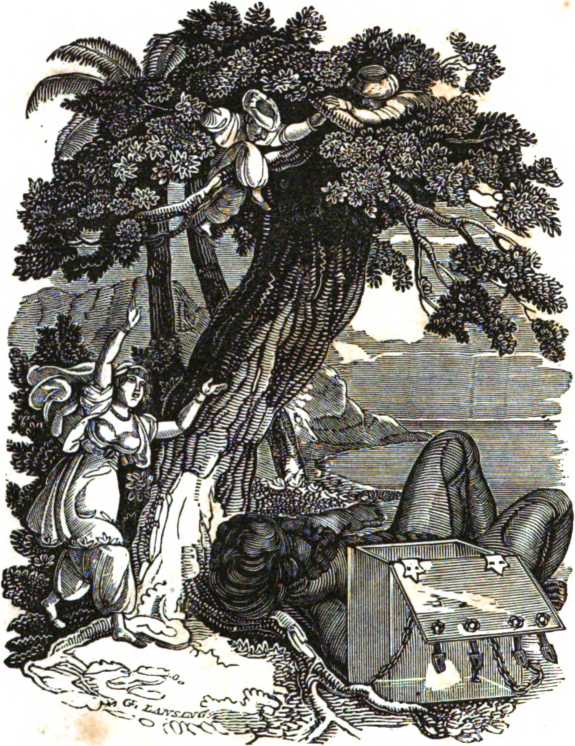

“The lady happening at the same time to look up to the tree, saw the two princes, and made a sign to them with her hand to come down without making any noise. Their fear was extreme when they found themselves discovered, and they prayed the lady, by other signs, to excuse them; but she, after having laid the monster’s head softly down on the ground, rose up, and spoke to them, with a low, but eager voice, to come down to her; she would take no denial. They made signs to her that they were afraid of the genie, and would fain have been excused. Upon which she ordered them to come down, and if they did not make haste, threatened to awake the genie, and bid him kill them.”

THE

EMBELLISHED WITH

A NEW EDITION,

CAREFULLY REVISED AND CORRECTED.

COMPLETE IN ONE VOLUME.

STEREOTYPED BY JAMES CONNER.

NO. 13 MINOR STREET.

The Story of the Genie, and the Lady shut up in a Glass Box

The Fable of the Ass, the Ox, and the Labourer

The Fable of the Dog and the Cock

The Story of the Merchant and the Genie

The History of the first Old Man and the Hind

The Story of the second Old Man and the two Black Dogs

The Story of the Grecian King and the Physician Douban

The Story of the Husband and the Parrot

The Story of the Vizier that was punished

The History of the young King of the Black Isles

The History of the three Calenders, Sons of Kings; and of the five ladies of Bagdad

The History of the first Calender, a King’s Son

The Story of the second Calender, a King’s Son

The Story of the Envious Man, and of him that he envied

The History of the third Calender, a King’s Son

The Story of Sinbad, the Sailor

The Story of the Lady that was murdered, and of the Young Man, her husband

The Story of Noureddin Ali and Bedreddin Hassan

The Story of the little Hunch-back

The Story told by the Christian Merchant

The Story told by the Sultan of Casgar’s Purveyor

The Story told by the Jewish Physician

The Story of the Barber’s eldest Brother

The Story of the Barber’s second Brother

The Story of the Barber’s third Brother

The Story of the Barber’s fourth Brother

The Story of the Barber’s fifth Brother

The Story of the Barber’s sixth Brother

The History of Aboulhassen Ali Ebn Becar, and Schemselnihar, favourite of Caliph Haroun Alraschid

The History of the Princess of China

The Story of Marzavan, with the sequel of that of the Prince Camaralzaman

The Story of the Princess Badoura, after her separation from Prince Camaralzaman

The Story of the Princes Amgiad and Assad

The Story of Prince Amgiad and a Lady of the City of the Magicians

The sequel of the Story of Prince Assad

The Story of Noureddin and the Fair Persian

The Story of Beder, Prince of Persia, and Giahaure, Princess of Samandal

The History of Ganem, Son of Abou Ayoub, and known by the surname of Love’s Slave

The History of Prince Zeyn Alasnam, and the King of the Genii

The History of Codadad and his Brothers

The History of the Princess of Deryabar

The Story of the Sleeper awakened

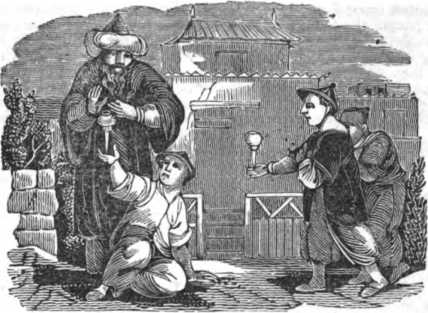

The Story of Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp

The Adventures of the Caliph Haroun Alraschid

The Story of the Blind Man, Baba Abdalla

The Story of Cogia Hassan Alhabbal

The Story of Ali Baba, and the Forty Robbers destroyed by a Slave

The Story of Ali Cogia, a Merchant of Bagdad

The Story of the Enchanted Horse

The Story of Prince Ahmed, and the Fairy Pari Banou

The Story of the Sisters who envied their youngest Sister

Numerous as are the editions of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, and frequently as they have received the embellishments of the artist, yet an Edition was still wanting, more easily accessible to the general reader, and which, while it combined economy, should not be deficient in elegance or illustration. To supply this chasm in the Literature of Romance, is the object of the Edition now offered to the public; and it can scarcely be necessary to observe, that although the Engravings are more numerous than in any preceding Edition, the vigour and spirit with which they are executed, will recommend them even to the admirers of the arts. These Engravings, the whole of which are from original designs, made expressly for this work, are nearly one hundred in number. The subjects have been very happily selected, and it will be seen with how much skill the Artist has embodied the humour and spirit of the Author. Under these circumstances, the Publisher has no doubt but that he will enjoy the double gratification of giving to the public the cheapest Edition of the Thousand and One Tales of the inimitable Oriental Story Teller, and of supplying a work, which, in point of embellishment, may be found worthy of a place in the best libraries.

Of the merits of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, their popularity would be sufficient evidence alone, had not the language of praise both in poetry and prose, long been exhausted on them. They are still the admiration of every person who can appreciate curious and useful information conveyed through the medium of fiction. “They are,” says Colonel Capper, in his Observations on the Passage to India, “by many people erroneously supposed to be a spurious production, and are therefore slighted in a manner they do not deserve. They were written by an Arabian, and are universally read and admired throughout Asia by all ranks of men, both old and young: considered, therefore, as an original work, descriptive as they are of the manners and customs of the East in general, and also of the Arabians in particular, they surely must be thought to merit the attention of the curious; nor are they, in my opinion, destitute of merit in other respects: for, although the extravagance of some of the stories is carried too far, yet, on the whole, one cannot help admiring the fancy and invention of the author, in striking out such a variety of pleasing incidents; pleasing I will call them, because they have frequently afforded me much amusement; nor do I envy any man his feelings, who is above being pleased with them. But before any person decides upon the merit of these books, he should be eye-witness of the effect they produce on those who best understand them. I have more than once seen the Arabians in the desert sitting round a fire listening to these stories with such attention and pleasure, as totally to forget the fatigue and hardship with which an instant before they were entirely overcome. In short, not to dwell any longer on this subject, they are in the same estimation all over Asia, that the adventures of Don Quixote are in Spain; and it is presumed, no man of genius or taste would think of making the tour of that country without previously reading the work of Cervantes.”

Nor is the picture of Oriental manners and customs, as exhibited in the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, that of a remote age; on the contrary, Mr. Dallaway, one of the recent travellers in the East, in his “Constantinople Ancient and Modern,” says, “Much of the romantic air which pervades the domestic habits of the persons described in the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, particularly in inferior life, will be observed in passing through the streets of that city. And we receive with additional pleasure a remembrance of the delight with which we at first perused them, in finding them authentic portraits of every Oriental nation.”

Mr. Hole, in his remarks on these Tales, considers the Sindbad as the Arabian Odyssey, and as descriptive of real places and manners; and he takes no small pains to ascertain the precise local situations of the islands which Sindbad is supposed to visit; but the beauties of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments have never been better described than in the following Sonnet to the Author, by Mr. Thomas Russell, Fellow of New College, Oxford:

“Blessed child of Genius, whose fantastic sprite

Rides on the vivid lightning’s flash, or roves

Through flowery valleys and elysian groves;

Or, borne on vent’rous pinions, takes its flight

To those dread realms, where, hid from mortal sight,

Fierce Genii roam, or where in bright alcoves

Mild Fairies reign, and woo their secret loves:

Whate’er thy theme, whether the magic might

Of the stern kings that dwell ’mid Ocean’s roar,

Or Sindbad’s perils, or the cruel wiles

Of Afric’s curst enchanters, charm us more,

Or aught more wond’rous still our ear beguiles;

Well pleased we listen to thy fabling lore,

And Truth itself with less attraction smiles.”

The present translation is from the Contes Arabes of M. Galland, who appears to have imbibed no inconsiderable portion of the spirit of the Oriental writer; and the utmost care has been taken to render it as correct as possible, consistent with the simplicity of the narration, and the luxuriance of its descriptions.

Although it cannot now be necessary to enter into a critical examination of a work which is equally admired by the learned and the unlearned, the young and the old, yet as the Genii and Fairies form so considerable a part of the machinery of these Tales, it may not be improper to say something respecting them.

The Genn or Ginn of the Arabians, is the same with the Div or Ganman of the Persians, the Deuta of the Indians, and the Turks’ Ginler, and signifies a genie or demon, who has a body formed of a more subtle matter than those of men, and like elementary fire. They are supposed to have been created and to have governed the world before Adam, and are divided into good and evil angels, and even giants, who, in the early times, made war against men, but have since been confined to one region, denominated from them Gimristan, the fairy land of our old romances. Gian ben Gian was the sovereign of these creatures, or of the Peris or fairies, who governed the world two thousand years; after which Eblis was sent by God to drive them into a distant part of the world, and there confine them, because of their rebellion. The shield of this prince is as famous as that of Achilles among the Greeks, and, like it, seven-fold and destructive of all enchantments, and was possessed by three successive Solomons, who performed with it marvellous but fabulous exploits, and fell at last into the hands of a hero named Tahmurath, surnamed Divbend, or the Conqueror of Giants.

Solomon, the son of David, is said by the eastern historians to have had not only men, but good and evil spirits, the birds and the winds, subjected to him by God; and to have been possessed of a ring of wonderful virtues, which seems to be nothing more than the extraordinary wisdom with which he was divinely endowed. All that we find in these writers about the marvellous actions and unrivalled empire of Solomon over men and devils, is drawn from the Scripture account of the extraordinary wisdom, and virtues, and throne of this monarch.

Peri are those beautiful creatures, which are neither men, angels, nor devils. Some have supposed them the female genies, but the Peris are of both sexes, and are good beings; on whom the Div or genies frequently make war, and shut up their prisoners in cages suspended on the highest trees, where their companions come and feed them with the finest odours, which are their common food, and defend them from the Div, who feel a sudden change to melancholy as soon as they approach them.

Benon, or Beni al Giam, is another name for these good spirits, who separated from the rebellious ones headed by Eblis or Lucifer. —D’Herbelot, voc. Genn, Gian, Peri. Solomon.

The chronicles of the Sussanians, the ancient kings of Persia, who extended their empire into the Indies, over all the islands thereunto belonging, a great way beyond the Ganges, and as far as China, acquaint us, that there was formerly a king of that potent family, the most excellent prince of his time: he was as much beloved by his subjects for his wisdom and prudence, as he was dreaded by his neighbours, because of his valour, and his warlike and well disciplined troops. He had two sons; the eldest, Schahriar, the worthy heir of his father, and endowed with all his virtues. The youngest, Schahzenan, was likewise a prince of incomparable merit.

After a long and glorious reign, this king died, and Schahriar mounted his throne. Schahzenan, being excluded from all share of the government by the laws of the empire, and obliged to live a private life, was so far from envying the happiness of his brother, that he made it his whole business to please him, and effected it without much difficulty. Schahriar, who had naturally a great affection for that prince, was so charmed with his complaisance, that out of an excess of friendship, he would needs divide his dominions with him, and gave him the kingdom of Great Tartary. Schahzenan went immediately, and took possession of it, and fixed the seat of his government at Samarcande, the metropolis of the country.

After they had been separated ten years, Schahriar, having a passionate desire to see his brother, resolved to send an ambassador to invite him to his court. He made choice of his prime vizier for the embassy, sent him to Tartary with a retinue answerable to his dignity, and he made all possible haste to Samarcande. When he came near the city, Schahzenan had notice of it, and went to meet him with the principal lords of his court, who, to put the more honour on the sultan’s minister, appeared in magnificent apparel. The king of Tartary received the ambassador with the greatest demonstrations of Joy; and immediately asked him concerning the welfare of the sultan his brother. The vizier having acquainted him that he was in health, gave him an account of his embassy. Schahzenan was so much affected with it, that he answered thus:— Sage vizier, the sultan, my brother, does me too much honour; he could propose nothing in the world so acceptable; I long as passionately to see him, as he does to see me. Time has been no more able to diminish my friendship than his. My kingdom is in peace, and I desire no more than ten days to get myself ready to go with you; so that there is no necessity for your entering the city for so short a time; I pray you to pitch your tents here, and I will order provisions in abundance for yourself and your company.

The vizier did accordingly, and as soon as the king returned, he sent him a prodigious quantity of provisions of all sorts, with presents of great value.

In the meanwhile, Schahzenan made ready for his journey, took orders about his meet important affairs, appointed a council to govern in his absence, and named a minister, of whose wisdom he had sufficient experience, and in whom he had an entire confidence, to be their president. At the end of ten days, his equipage being ready, he took his leave of the queen his wife, and went out of town in the evening with his retinue, pitched his royal pavilion near the vizier’s tent, and discoursed with that ambassador till midnight. But willing once more to embrace the queen, whom he loved entirely, he returned alone to his palace, and went straight to her majesty’s apartment, who, not expecting his return, had taken one of the meanest officers of her household to her bed, where they lay both fast to sleep, having been in bed a considerable while.

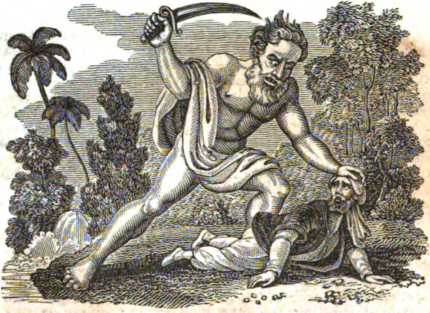

The king entered without any noise, and pleased himself to think how he should surprise his wife, who, he thought, loved him as entirely as he did her: but how great was his surprise, when by the light of the flambeaux, which burn all night in the apartments of those eastern princes, he saw a man in her arms! He stood immoveable for a time, not knowing how to believe his own eyes; but, finding that it was not to be doubted, How! says he to himself, I am scarce out of my palace, and but just under the walls of Samarcande, and dare they put such an outrage upon me! Ah! perfidious wretches! your crime shall not go unpunished. As king, I am to punish wickedness committed in my dominions; and as an enraged husband, I must sacrifice you to my just resentment. In a word, this unfortunate prince, giving way to his rage, drew his scimitar, and, approaching the bed, killed them both with one blow, turning their sleep into death; and afterwards taking them up, threw them out of a window, into the ditch that surrounded the palace.

Having avenged himself thus, he went out of town privately, as he came into it; and, returning to his pavilion, without saying one word of what had happened, he ordered the tents to be struck, and to make ready for his journey. This was speedily done; and before day he began his march, with kettle-drums and other instruments of music, that filled every one with joy, except the king, who was so much troubled at the disloyalty of his wife, that he was seized with extreme melancholy, which preyed upon him during his whole journey.

When he drew near the capital of the Indies, the sultan Schahriar and all his court came out to meet him; and the princes were overjoyed to see one another, and alighting, after mutual embraces, and other marks of affection and respect, they mounted again, and entered the city, with the acclamations of vast multitudes of people. The sultan conducted his brother to the palace he had provided for him, which had a communication with his own, by means of a garden; and was so much the more magnificent, that it was set apart as a banqueting-house for public entertainments, and other diversions of the court, and the splendour of it had been lately augmented by new furniture.

Schahriar immediately left the king of Tartary, that he might give him time to bathe himself, and to change his apparel; and as soon as he had done, he came to him again, and they sat down together upon a sofa or alcove. The courtiers kept at a distance, out of respect, and those two princes entertained one another suitably to their friendship, their nearness of blood, and the long separation that had passed betwixt them. The time of supper being come, they ate together, after which they renewed their conversation, which continued till Schahriar, perceiving that it was very late, left his brother to rest.

The unfortunate Schahzenan went to bed; and though the conversation of his brother had suspended his grief for some time, it returned upon him with more violence; so that, instead of taking his necessary rest, he tormented himself with cruel reflections. All the circumstances of his wife’s disloyalty presented themselves afresh to his imagination, in so lively a manner, that he was like one beside himself. In a word, not being able to sleep, he got up, and giving himself over to afflicting thoughts, they made such an impression upon his countenance, that the sultan could not but take notice of it, and said thus to himself: What can be the matter with the king of Tartary, that he is so melancholy? Has he any cause to complain of his reception? No, surely; I have received him as a brother whom I love, so that I can charge myself with no omission in that respect. Perhaps it grieves him to be at such a distance from his dominions, or from the queen his wife. Alas! if that be the matter, I must forthwith give him the presents I designed for him, that he may return to Samarcande when he pleases. Accordingly, next day Schahriar sent him part of those presents, being the greatest rarities and the richest things that the Indies could afford. At the same time he endeavoured to divert his brother every day, by new objects of pleasure, and the finest treats; which, instead of giving the king of Tartary any ease, only increased his sorrow.

One day, Schahriar, having appointed a great hunting match, about two days’ journey from his capital, in a place that abounded with deer, Schahzenan prayed him to excuse him, for his health would not allow him to bear him company. The sultan, unwilling to put any constraint upon him, left him at his liberty, and went a hunting with his nobles. The king of Tartary being thus left alone, shut himself up in his apartment, and sat down at a window that looked into the garden. That delicious place, and the sweet harmony of an infinite number of birds which chose it for a place of retreat, must certainly have diverted him, had he been capable of taking pleasure in any thing; but being perpetually tormented with the fatal remembrance of his queen’s infamous conduct, his eyes were not so often fixed upon the garden, as lifted up to heaven to bewail his misfortunes.

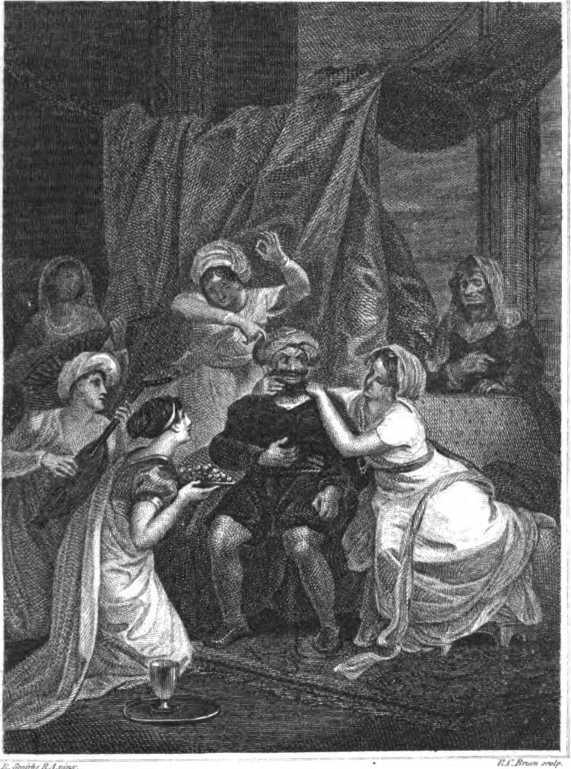

While he was thus swallowed up with grief, an object presented itself to his view, which quickly turned all his thoughts another way. A secret gate of the sultan’s palace opened all of a sudden, and there came out of it twenty women, in the midst of whom walked the sultaness, who was easily distinguished from the rest by her majestic air. The princess, thinking that the king of Tartary was gone a hunting with his brother the sultan, came up with her retinue near the windows of his apartment; for the prince had placed himself so that he could see all that passed in the garden, without being perceived himself. He observed, that the persons who accompanied the sultaness threw off their veils and long robes, that they might be at more freedom; but was wonderfully surprised when he saw ten of them to be blacks, and that each of them took his mistress. The sultaness, on her part, was not long without her gallant. She clapped her hands, and called Masoud, Masoud; and immediately a black came down from a tree, and ran to her in all haste.

Modesty will not allow, nor is it necessary, to relate what passed between the blacks and the ladies. It is sufficient to say, that Schahzenan saw enough to convince him that his brother was as much to be pitied as himself. This amorous company continued together till midnight, and having bathed all together, in a great piece of water which was one of the chief ornaments of the garden, they dressed themselves, and re-entered the palace by the secret door, all except Masoud, who climbed up his tree, and got over the garden wall the same way as he came in.

All this having passed in the king of Tartary’s sight, occasioned him to make a multitude of reflections. How little reason had I, says he, to think that no one was so unfortunate as myself! It is certainly the unavoidable fate of all husbands, since the sultan, my brother, who is sovereign of so many dominions, and the greatest prince of the earth, could not escape it. The case being so, what a fool am I to kill myself with grief! I am resolved that the remembrance of a misfortune so common shall never more disturb my quiet.

From that moment he forbore afflicting himself. Being unwilling to sup till he saw the whole scene that was acted under his window, he called then for his supper, eat with a better appetite than he had done at any time since his coming from Samarcande, and listened with some degree of pleasure to the agreeable concert of vocal and instrumental music, that was appointed to entertain him while at table.

He continued after this in very good humour; and when he knew that the sultan was returning, he went to meet him, and paid him his compliments with great gayety. Schahriar at first took no notice of this alteration; but politely expostulated with him, why he would not bear him company at hunting the stag; and without giving him time to reply, entertained him with a relation of the great number of deer and other game they had killed, and what pleasure he had in the sport. Schahzenan heard him with attention, gave answer to every thing, and being free from that melancholy which formerly overclouded his wit, he said a thousand agreeable and pleasant things to the sultan.

Schahriar, who expected to have found him in the same state as he left him, was overjoyed to see him so cheerful, and spoke to him thus: Dear brother, I return thanks to Heaven for the happy change it has made in you during my absence; I am extremely rejoiced at it; but I have a request to make to you, and conjure you not to deny me. —I can refuse you nothing, replied the king of Tartary; you may command Schahzenan as you please; speak, I am impatient till I know what you desire of me. —Ever since you came to my court, replied Schahriar, I found you swallowed up by a deep melancholy, and I in vain attempted to remove it by all sorts of diversion. I imagined it might be occasioned by reason of your distance from your dominions, or that love might have a great share in it, and that the queen of Samarcande, who, no doubt, is an accomplished beauty, might be the cause of it. I do not know if I be mistaken; but I must own, that it was for this very reason I would not importune you upon the subject, for fear of making you uneasy. But without my having contributed any thing towards it, I find now, upon my return, that you are in the best humour that can be, and that your mind is entirely delivered from that black vapour which disturbed it. Pray do me the favour to tell me why you were so melancholy, and why you are no longer so.

Upon this, the king of Tartary continued for some time, as if he had been meditating, and contriving what he should answer; but at last replied as follows: You are my sultan and master; but excuse me, I beseech you, from answering your question. —No, dear brother, said the sultan, you must answer me; I will take no denial. Schahzenan, not being able to withstand these pressing instances, answered, Well, then, brother, I will satisfy you, since you command me; and having told him the story of the queen of Samarcande’s treachery, This, says he, was the cause of my grief; judge whether I had not reason enough to give myself up to it.

Oh! my brother, says the sultan, (in a tone which showed what an interest he took in the king of Tartary’s story,) what a horrible story do you tell me! How impatient was I till I heard it out! I commend you for punishing the traitors who offered you such an outrage. Nobody can blame you for that action: it was just; and, for my part, had the case been mine, I should scarce have been so moderate as you. I would not have satisfied myself with the life of one woman; I verily think I should have sacrificed a thousand to my fury. I cease now to wonder at your melancholy. The cause of it was too sensible and too mortifying, not to make you yield to it. O heaven! what a strange adventure! Nor do I believe the like ever befel any man but yourself. But, in short, I must bless God, who has comforted you; and since I doubt not but your consolation is well grounded, be so good as to let me know what it is, and conceal nothing from me. Schahzenan was not so easily prevailed upon in this point, as he had been in the other, because of his brother’s concern it; but being obliged to yield to his pressing instances, answered, I must obey you, then, since your command is absolute; yet I am afraid that my obedience will occasion your trouble to be greater than ever mine was. But you must blame yourself for it, since you force me to reveal a thing which I should otherwise have buried in eternal oblivion. What you say, answers Schahriar, serves only to increase my curiosity. Make haste to discover the secret, whatever it be. The king of Tartary being no longer able to refuse, gave him the particulars of all that he had seen of the blacks in disguise; of the ungoverned passion of the sultaness and her ladies; and he did not forget Masoud. After having been witness to those infamous actions, says he, I believed all women to be naturally inclined thereto, and that they could not resist their inclination. Being of this opinion, it seemed to me to be an unaccountable weakness in men to place any confidence in their fidelity. This reflection brought on many others; and, in short, I thought the best thing I could do was to make myself easy. It cost me some pains, indeed, but at last I effected it; and if you will take my advice, you will follow my example.

THE LADY OF THE GLASS CASE.

Though the advice was good, the sultan could not relish it, but fell into a rage. What! says he, is the sultaness of the Indies capable of prostituting herself in so base a manner? No, brother, I cannot believe what you say, except I saw it with my own eyes; your’s must needs have deceived you: the matter is so important, that I must be satisfied of it myself. Dear brother, answers Schahzenan, that you may without much difficulty. Appoint another hunting match; and when we are out of town with your court and mine, we will stop under our tents, and at night let you and I return alone to my apartments; I am certain the next day you will see what I saw. The sultan, approving the stratagem, immediately appointed a new hunting-match; and that same day the tents were set up at the place appointed.

Next day the two princes set out with all their retinue; they arrived at the place of encampment, and staid there till night. Then Schahriar called his grand vizier, and without acquainting him with his design, commanded him to stay in his place during his absence, and suffer no person to go out of the camp upon any account whatever. As soon as he had given this order, the king of Grand Tartary and he took horse, passed through the camp incognito, returned to the city, and went to Schahzenan’s apartment. They had scarce placed themselves in the same window where the king of Tartary had beheld the scene of the disguised blacks, but the secret gate opened, the sultaness and her ladies entered the garden with the blacks, and she, having called upon Masoud, the sultan saw more than enough to convince him fully of his dishonour and misfortune.

O heavens! cried he, what an indignity! what horror! Can the wife of a sovereign such as I am, be capable of such an infamous action? After this, let no prince boast of his being perfectly happy. Alas! my brother, continued he, (embracing the king of Tartary,) let us both renounce the world; honour is banished out of it; if it flatters us one day, it betrays us the next! Let us abandon our dominions and grandeur; let us go into foreign countries, where we may lead an obscure life, and conceal our misfortunes. Schahzenan did not at all approve of this resolution, but did not think fit to contradict Schahriar in the heat of his passion. Dear brother, says he, your will shall be mine; I am ready to follow you whither you please: but promise me that you will return if we can meet with any one that is more unhappy than ourselves. I agree to it, says the sultan, but doubt much whether we shall. I am not of your mind in this, replies the king of Tartary; I fancy our journey will be but short. Having said thus, they went secretly out of the palace by a different way from that by which they came. They travelled as long as it was day, and lay the first night under trees; and getting up about break of day, they went on till they came to a fine meadow upon the bank of the sea, that was besprinkled with great trees. They sat down under one of those trees to rest and refresh themselves, and the chief subject of their conversation was the infidelity of their wives.

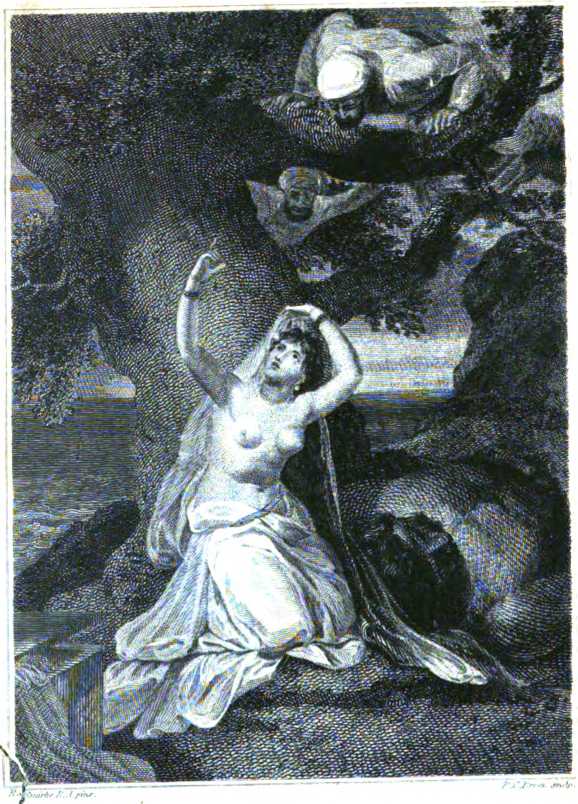

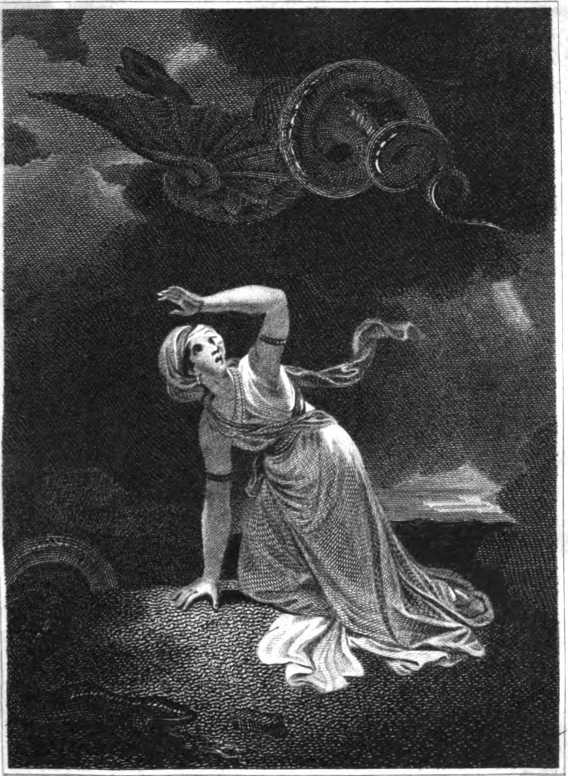

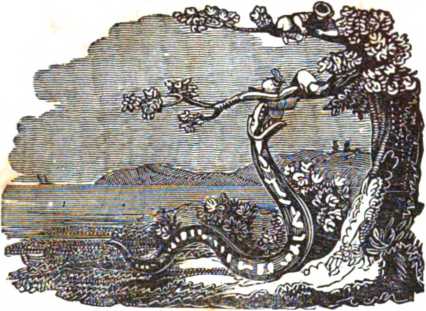

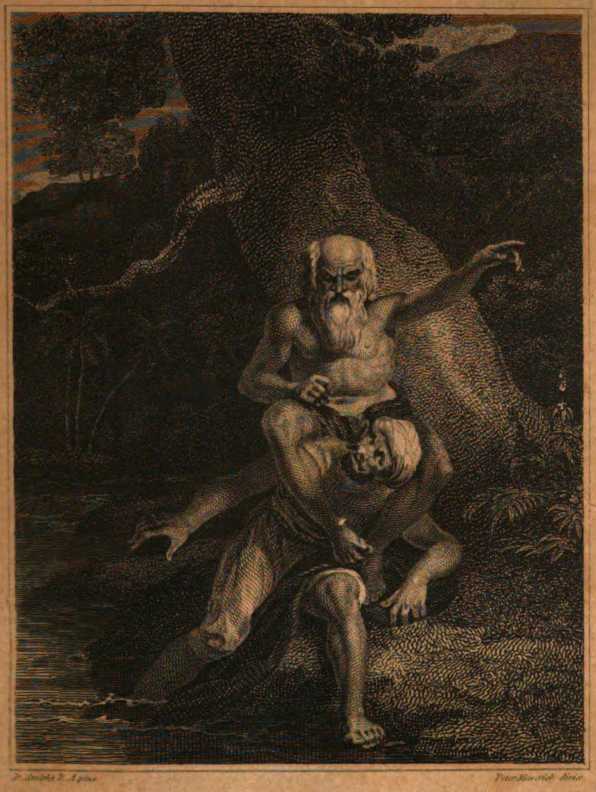

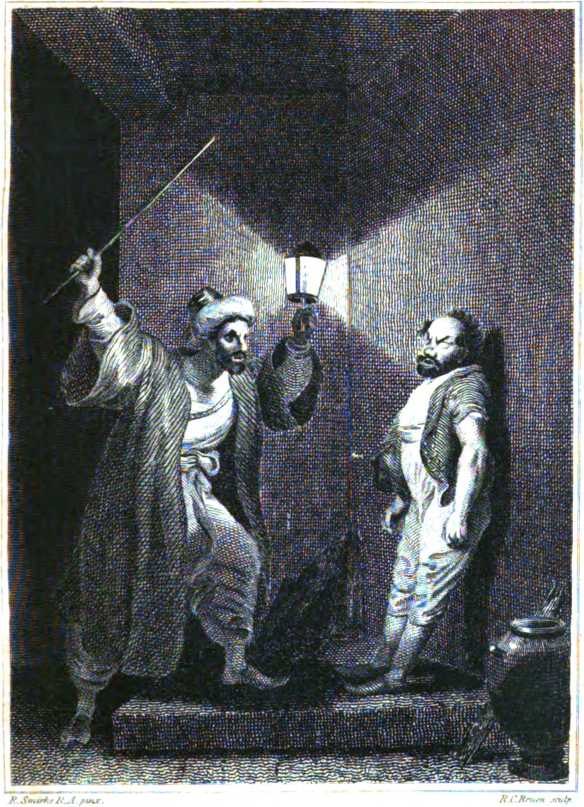

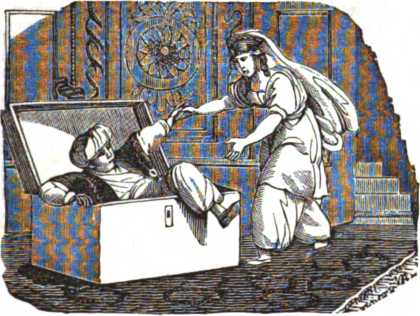

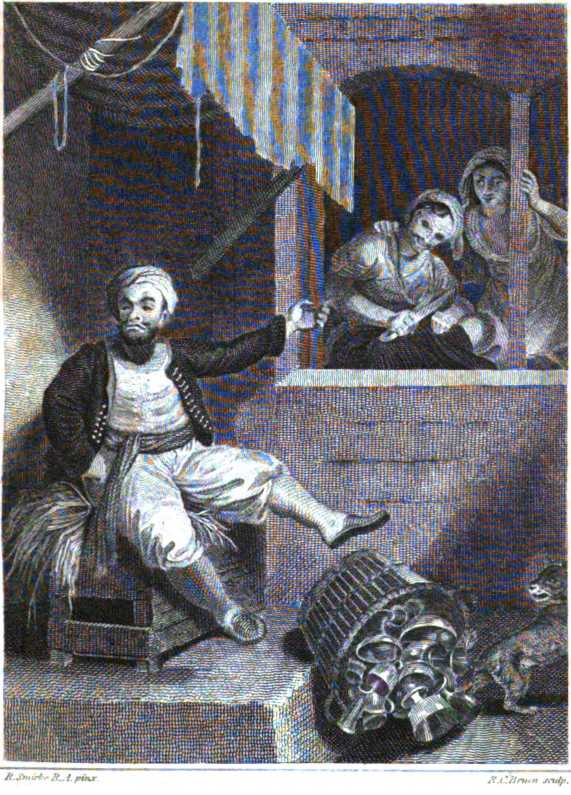

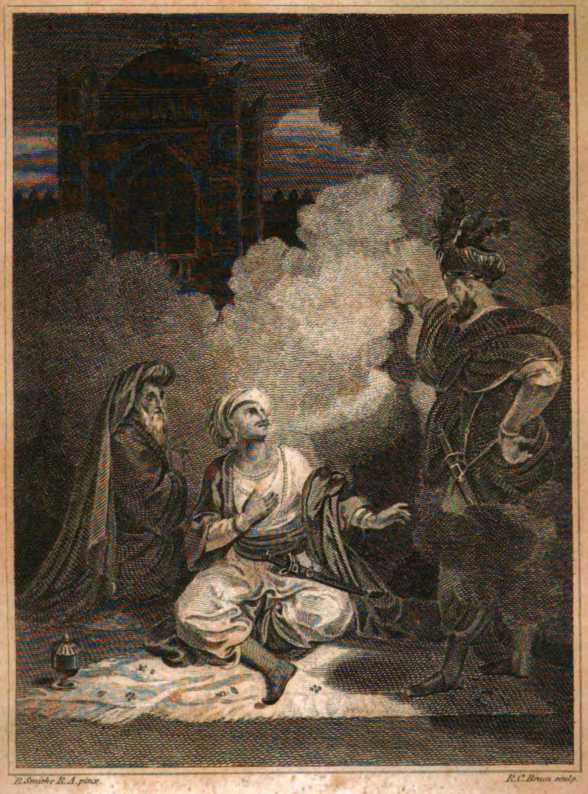

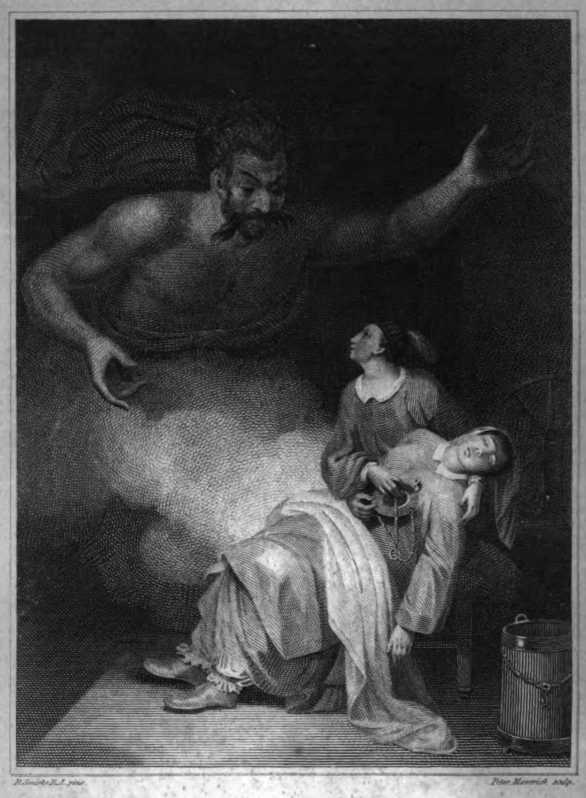

They had not sat long, before they heard a frightful noise from the sea, and a terrible cry, which filled them with fear; then, the sea opening, there arose up something like a great black column, which reached almost to the clouds. This redoubled their fear, made them rise speedily, and climb up into a tree to hide themselves. They had scarce got up, till looking to the place from whence the noise came, and where the sea opened, they observed that the black column advanced, winding about towards the shore, cleaving the water before it. They could not at first think what it should be; but in a little time they found that it was one of those malignant genii that are mortal enemies to mankind, and are always doing them mischief. He was black, frightful, had the shape of a giant, of a prodigious stature, and carried on his head a great glass box, shut with four locks of fine steel. He entered the meadow with his burden, which he laid down just at the foot of the tree where the two princes were, who looked upon themselves to be dead men. Meanwhile the genie sat down by his box, and opening it with four keys that he had at his girdle, there came out a lady magnificently apparelled, of a majestic stature, and a complete beauty. The monster made her sit down by him, and eying her with an amorous look, Lady, says he, nay, most accomplished of all ladies who are admired for their beauty, my charming mistress, whom I carried off on your wedding-day, and have loved so constantly ever since, let me sleep a few moments by you; for I found myself so very sleepy, that I came to this place to take a little rest. Having spoken thus, he laid down his huge head upon the lady’s knees, and stretching out his legs, which reached as far as the sea, he fell asleep presently, and snored so that he made the banks echo again.

The lady happening at the same time to look up to the tree, saw the two princes, and made a sign to them with her hand to come down without making any noise. Their fear was extreme when they found themselves discovered, and they prayed the lady, by other signs, to excuse them; but she, after having laid the monster’s head softly down on the ground, rose up and spoke to them with a low, but eager voice, to come down to her; she would take no denial. They made signs to her that they were afraid of the genie, and would fain have been excused. Upon which she ordered them to come down, and if they did not make haste, threatened to awake the genie, and bid him kill them.

These words did so much intimidate the princes, that they began to come down with all possible precaution, lest they should awake the genie. When they came down, the lady took them by the hand, and going a little farther with them under the trees, made a very urgent proposal to them. At first they rejected it, but she obliged them to accept it by her threats. Having obtained what she desired, she perceived that each of them had a ring on his finger, which she demanded of them. As soon as she received them, she went and took a box out of the bundle, where her toilet was, pulled out a string of other rings of all sorts, which she showed them, and asked them if they knew what those jewels meant. No, said they, we hope you will be pleased to tell us. These are, replied she, the rings of all the men to whom I have granted my favours. There are full fourscore and eighteen of them, which I keep as tokens to remember them; and asked your’s for the same reason, to make up the hundred. So that, continued she, I have a hundred gallants already, notwithstanding the vigilance of this wicked genie, who never leaves me. He may lock me up in this glass box, and hide me in the bottom of the sea; I find a way to cheat his care. You may see by this, that when a woman has formed a project, there is no husband or lover that can hinder her putting it into execution. Men had better not put their wives under such restraint, as it only serves to teach them cunning. Having spoken thus to them, she put their rings upon the same string with the rest, and sitting down by the monster, as before, laid his head again upon her lap, and made a sign for the princes to be gone.

They returned immediately by the same way they came, and when they were out of sight of the lady and genie, Schahriar says to Schahzenan, Well, brother, what do you think of this adventure? Has not the genie a very faithful mistress? And do not you agree that there is no wickedness equal to that of woman? Yes, brother, answers the king of Tartary; and you must also agree that the monster is more unfortunate, and more to be pitied than we. Therefore, since we have found what we sought for, let us return to our dominions, and let not this hinder us from marrying. For my part, I know a method by which to keep inviolable the fidelity that my wife owes me. I will say no more of it at present, but you will hear of it in a little time, and I am sure you will follow my example. The sultan agreed with his brother; and continuing their journey, they arrived in the camp the third night after they left it.

The news of the sultan’s return being spread, the courtiers came betimes in the morning before his pavilion, to wait on him. He ordered them to enter, received them with a more pleasant air than formerly, and gave each of them a present: after which he told them he would go no farther, ordered them to take horse, and returned speedily to his palace.

As soon as he arrived, he ran to the sultaness’s apartment, commanded her to be bound before him, and delivered her to his grand vizier, with an order to strangle her, which was accordingly executed by that minister without inquiring into her crime. The enraged prince did not stop here, but cut off the heads of all the sultaness’s ladies with his own hand. After this rigorous punishment, being persuaded that no woman was chaste, he resolved, in order to prevent the disloyalty of such as he should afterwards marry, to wed one every night, and have her strangled next morning. Having imposed this cruel law upon himself, he swore that he would observe it immediately after the departure of the king of Tartary, who speedily took leave of him, and being laden with magnificent presents, set forward on his journey.

Schahzenan being gone, Schahriar ordered his grand vizier to bring him the daughter of one of his generals. The vizier obeyed; the sultan lay with her, and putting her next morning into his hands again, in order to be strangled, commanded him to get him another next night. Whatever reluctance the vizier had to put such orders in execution, as he owed blind obedience to the sultan his master, he was forced to submit. He brought him then the daughter of a subaltern, whom he also cut off next day. After her he brought a citizen’s daughter; and, in a word, there was every day a maid married, and a wife murdered.

The rumour of this unparalleled barbarity, occasioned a general consternation in the city, where there was nothing but crying and lamentation. Here, a father in tears, and inconsolable for the loss of his daughter! and there, tender mothers, dreading lest their daughters should have the same fate, making the air to resound beforehand with their groans: so that, instead of the commendations and blessings which the sultan had hitherto received from his subjects, their mouths were now filled with imprecations against him.

The grand vizier, who, as has been already said, was the executioner of this horrid injustice, against his will, had two daughters, the eldest called Scheherazade, and the youngest Dinarzade. The latter was a lady of very great merit; but the elder had courage, wit, and penetration infinitely above her sex. She read much, and had such a prodigious memory, that she never forgot any thing she had read. She had successfully applied herself to philosophy, physic, history, and the liberal arts; and for verse exceeded the best poets of her time. Besides this, she was a perfect beauty, and all her fine qualifications were crowned by solid virtue.

The vizier passionately loved a daughter so worthy of his tender affection; and one day, as they were discoursing together, she says to him, Father, I have one favour to beg of you, and most humbly pray you to grant it me. I will not refuse it, answers he, provided it be just and reasonable. For the justice of it, says she, there can be no question, and you may judge of it by the motive which obliges me to demand it of you. I wish to stop the course of that barbarity which the sultan exercises upon the families of this city. I would dispel those unjust fears which so many mothers have of losing their daughters in such a fatal manner. Your design, daughter, replies the vizier, is very commendable; but the evil you would remedy to me seems incurable; how do you pretend to effect it? —Father, says Scheherazade, since by your means the sultan makes every day a new marriage, I conjure you by the tender affection you bear to me, to procure me the honour of his bed. The vizier could not hear this without horror. O heavens! replied he, in a passion, have you lost your senses, daughter, that you make such a dangerous request to me? You know the sultan has sworn by his soul that he will never lie above one night with the same woman, and to order her to be killed next morning: and would you have me propose you to him? Consider well to what your indiscreet zeal will expose you. —Yes, dear father, replies the virtuous daughter, I know the risk I run; but that does not frighten me. If I perish, my death will be glorious; and if I succeed, I shall do my country an important piece of service. No, no, says the vizier, whatever you can represent to engage me to let you throw yourself into that horrible danger, do not think that ever I will agree to it. When the sultan shall order me to strike my poinard into your heart, alas! I must obey him; and what an employment is that for a father! Ah! if you do not fear death, yet at least be afraid of occasioning me the mortal grief of seeing my hand stained with your blood. Once more, father, says Scheherazade, grant me the favour I beg. Your stubbornness, replies the vizier, will make me angry; why will you run headlong to your ruin? They that do not foresee the end of a dangerous enterprise, can never bring it to a happy issue. I am afraid the same thing will happen to you that happened to the ass, which was well, and could not keep himself so. What misfortune befell the ass? replies Scheherazade. I will tell you, says the vizier, if you will hear me.

FABLE.

The Ass, the Ox, and the Labourer.

A very wealthy merchant possessed several country-houses, where he kept a large number of cattle of every kind. He retired with his wife and family to one of these estates, in order to improve it under his own direction. He had the gift of understanding the language of beasts, but with this condition, that he should not, on pain of death, interpret it to any one else. And this hindered him from communicating to others what he learned by means of this faculty.

He kept in the same stall an ox and an ass. One day as he sat near them, and was amusing himself in looking at his children who were playing about him, he heard the ox say to the ass, Sprightly, O! how happy do I think you, when I consider the ease you enjoy, and the little labour that is required of you. You are carefully rubbed down and washed, you have well-dressed corn, and fresh clean water. Your greatest business is to carry the merchant, our master, when he has any little journey to make, and were it not for that you would be perfectly idle. I am treated in a very different manner, and my condition is as deplorable as yours is fortunate. Daylight no sooner appears than I am fastened to a plough, and made to work till night, which so fatigues me, that sometimes my strength entirely fails. Besides, the labourer, who is always behind me, beats me continually. By drawing the plough, my tail is all fleaed; and in short, after having laboured from morning to night, when I am brought in they give me nothing to eat but sorry dry beans, not so much as cleansed from dirt, or other food equally bad; and to heighten my misery, when I have filled my belly with such ordinary stuff, I am forced to lie all night in my own dung; so that you see I have reason to envy your lot.

The ass did not interrupt the ox; but when he had concluded, answered, They that called you a foolish beast did not lie. You are too simple; you suffer them to conduct you whither they please, and show no manner of resolution. In the mean time, what advantage do you reap from all the indignities you suffer? You kill yourself for the ease, pleasure, and profit of those who give you no thanks for your service. But they would not treat you so, if you had as much courage as strength. When they come to fasten you to the stall, why do you not resist? why do you not gore them with your horns, and show that you are angry, by striking your foot against the ground? And, in short, why do you not frighten them by bellowing aloud? Nature has furnished you with means to command respect; but you do not use them. They bring you sorry beans and bad straw; eat none of them; only smell and then leave them. If you follow my advice, you will soon experience a change, for which you will thank me.

The ox took the ass’s advice in very good part, and owned he was much obliged to him. Dear Sprightly, added he, I will not fail to do as you direct, and you shall see how I will acquit myself. Here ended their conversation, of which the merchant lost not a word.

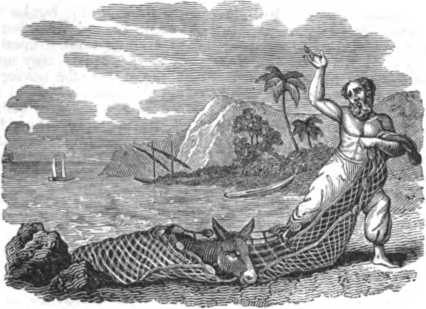

Early the next morning the labourer went for the ox. He fastened him to the plough, and conducted him to his usual work. The ox, who had not forgotten the ass’s counsel, was very troublesome and untowardly all that day, and in the evening, when the labourer brought him back to the stall, and began to fasten him, the malicious beast, instead of presenting his head willingly as he used to do, was restive, and drew back bellowing; and then made at the labourer, as if he would have gored him with his horns. In a word, he did all the ass had advised him. The day following, the labourer came as usual, to take the ox to his labour; but finding the stall full of beans, the straw that he had put in the night before not touched, and the ox lying on the ground with his legs stretched out and panting in a strange manner, he believed him to be unwell and pitied him, and thinking that it was not proper to take him to work, went immediately and acquainted his master with his condition. The merchant perceiving that the ox had followed all the mischievous advice of the ass, determined to punish the latter, and accordingly ordered the labourer to go and put him in the ox’s place, and to be sure to work him hard. The labourer did as he was desired. The ass was forced to draw the plough all that day, which fatigued him so much the more, as he was not accustomed to that kind of labour; besides, he had been so soundly beaten, that he could scarcely stand when he came back.

Meanwhile, the ox was mightily pleased; he ate up all that was in the stall, and rested himself the whole day. He rejoiced that he had followed the ass’s advice, blessed him a thousand times for the kindness he had done him, and did not fail to express his obligation when the ass had returned. The ass made no reply, so vexed was he at the ill-treatment he had received; but he said within himself, It is by my own imprudence I have brought this misfortune upon myself. I lived happily, every thing smiled upon me; I had all that I could wish; it is my own fault that I am brought to this miserable condition; and if I cannot contrive some way to get out of it, I am certainly undone. As he spoke, his strength was so much exhausted that he fell down in his stall, as if he had been half dead.

Here the grand vizier addressed himself to Scheherazade, and said, Daughter, you act just like this ass; you will expose yourself to destruction by your erroneous policy. Take my advice, remain quiet, and do not seek to hasten your death. Father, replied Scheherazade, the example you have set before me will not induce me to change my resolution. I will never cease importuning you until you present me to the sultan as his bride. The vizier, perceiving that she persisted in her demand, replied, Alas! then, since you will continue obstinate, I shall be obliged to treat you in the same manner as the merchant whom I before referred to, treated his wife a short time after.

The merchant understanding that the ass was in a lamentable condition, was desirous of knowing what passed between him and the ox, therefore, after supper he went out by moonlight, and sat down by them, his wife bearing him company. After his arrival, he heard the ass say to the ox, Comrade, tell me, I pray you, what you intend to do to-morrow, when the labourer brings you meat? What will I do! replied the ox, I will continue to act as you taught me. I will draw back from him and threaten him with my horns, as I did yesterday: I will feign myself ill, and at the point of death. Beware of that, replied the ass, it will ruin you; for as I came home this evening, I heard the merchant, our master, say something that makes me tremble for you. Alas! what did you hear? demanded the ox; as you love me, withhold nothing from me, my dear Sprightly. Our master, replied the ass, addressed himself thus to the labourer: Since the ox does not eat and is not able to work, I would have him killed to-morrow, and we will give his flesh as an alms to the poor for God’s sake; as for the skin that will be of use to us, and I would have you give it the currier to dress; therefore be sure to send for the butcher. This is what I had to tell you, said the ass. The interest I feel in your preservation, and my friendship for you, obliged me to make it known to you, and to give you new advice. As soon as they bring you your bran and straw, rise up, and eat heartily. Our master will by this think that you are recovered, and no doubt will recall his orders for killing you; but, if you act otherwise, you will certainly he slaughtered.

This discourse had the effect which the ass designed. The ox was greatly alarmed, and bellowed for fear. The merchant, who heard the conversation very attentively, fell into a loud fit of laughter. His wife was greatly surprised, and asked, Pray, husband, tell me what you laugh at so heartily, that I may laugh with you. Wife, replied he, you must content yourself with hearing me laugh. No, returned she, I will know the reason. I cannot afford you that satisfaction, answered he, and can only inform you that I laugh at what our ass just now said to the ox. The rest is a secret, which I am not allowed to reveal. What, demanded she, hinders you from revealing the secret? If I tell it you, replied he, I shall forfeit my life. You only jeer me, cried his wife; what you would have me believe cannot be true. If you do not directly satisfy me as to what you laugh at, and tell me what the ox and the ass said to one another, I swear by heaven that you and I shall never bed together again.

Having spoken thus, she went into the house, and seating herself in a corner, cried there all night. Her husband lay alone, and finding next morning that she continued in the same humour, told her, she was very foolish to afflict herself in that manner; that the thing was not worth so much; that it concerned her very little to know, while it was of the utmost consequence to him to keep the secret: therefore, continued he, I conjure you to think no more of it. I shall still think so much of it, replied she, as never to forbear weeping till you have satisfied my curiosity. But I tell you very seriously, answered he, that it will cost me my life if I yield to your indiscreet solicitations. Let what will happen, said she, I do insist upon it. I perceive, resumed the merchant, that it is impossible to bring you to reason, and since I foresee that you will occasion your own death by your obstinacy, I will call in your children, that they may see you before you die. Accordingly he called for them, and sent for her father and mother, and other relations. When they were come, and heard the reason of their being summoned, they did all they could to convince her that she was in the wrong, but to no purpose: she told them that she would rather die than yield that point to her husband. Her father and mother spoke to her, and told her that what she desired to know was of no importance to her; but they could produce no effect upon her, either by their authority or entreaties. When her children saw that nothing would prevail to draw her out of that sullen temper, they wept bitterly. The merchant himself was half frantic, and almost ready to risk his own life to save that of his wife, whom he sincerely loved.

Now, my daughter, continued the vizier to Scheherazade, this merchant had fifty hens, and one cock, with a dog, that gave good heed to all that passed. While the merchant was, as I said, considering what he had best do, he saw his dog run towards the cock as he was treading a hen, and heard him say to him: Cock, I am sure heaven will not let you live long; are you not ashamed to act thus to-day? The cock standing up on tiptoe, answered fiercely: and why not to-day as well as other days? If you do not know, replied the dog, then I will tell you, that this day our master is in great perplexity. His wife would have him reveal a secret which is of such a nature, that the disclosure would cost him his life. Things are come to that pass, that it is to be feared he will scarcely have resolution enough to resist his wife’s obstinacy; for he loves her, and is affected by the tears she continually sheds. We are all alarmed at his situation, while you only insult our melancholy, and have the impudence to divert yourself with your hens.

The cock answered the dog’s reproof thus: What, has our master so little sense? he has but one wife, and cannot govern her, and though I have fifty I make them all do what I please. Let him use his reason, he will soon find a way to get rid of his trouble. How? demanded the dog; what would you have him to do? Let him go into the room where his wife is, resumed the cock, lock the door, and take a stick and thrash her well; and I will answer for it, that will bring her to her senses, and make her forbear to importune him to discover what he ought not to reveal. The merchant had no sooner heard what the cock said, than he took up a stick, went to his wife whom he found still crying, and shutting the door, belaboured her so soundly, that she cried out “Enough, husband, enough, forbear, and I will never ask the question more.” Upon this, perceiving that she repented of her impertinent curiosity, he desisted; and opening the door her friends came in, were glad to find her cured of her obstinacy, and complimented her husband upon this happy expedient to bring his wife to reason. Daughter, added the grand vizier, you deserve to be treated as the merchant treated his wife.

Father, replied Scheherazade, I beg you would not take it ill that I persist in my opinion. I am nothing moved by the story of this woman. I could relate many, to persuade you that you ought not to oppose my design. Besides, pardon me for declaring, that your opposition is vain, for if your paternal affection should hinder you from granting my request, I will go and offer myself to the sultan. In short, the father, being overcome by the resolution of his daughter, yielded to her importunity, and though he was much grieved that he could not divert her from so fatal a resolution, he went instantly to acquaint the sultan, that next night he would bring him Scheherazade.

The sultan was much surprised at the sacrifice which the grand vizier proposed to make. How could you, says he, resolve to bring me your own daughter? Sir, answered the vizier, it is her own offer. The sad destiny that awaits her could not intimidate her; she prefers the honour of being your majesty’s wife for one night, to her life. But do not act under a mistake, vizier, said the sultan; to-morrow when I place Scheherazade in your hands, I expect you will put her to death; and if you fail, I swear that your own life shall answer. Sir, rejoined the vizier, my heart without doubt will be full of grief to execute your commands; but it is to no purpose for nature to murmur. Though I am her father, I will answer for the fidelity of my hand to obey your order. Schahriar accepted his minister’s offer, and told him he might bring his daughter when he pleased.

The grand vizier went with the intelligence to Scheherazade, who received it with as much joy as if it had been the most agreeable information she could have received. She thanked her father for having so greatly obliged her; and perceiving that he was overwhelmed with grief, told him, for his consolation, that she hoped he would never repent of having married her to the sultan; and that, on the contrary, he should have reason to rejoice at his compliance all his days.

Her business now was to adorn herself to appear before the sultan; but before she went, she took her sister Dinarzade apart, and said to her, My dear sister, I have need of your assistance in a matter of great importance, and must pray you not to deny it me. My father is going to conduct me to the sultan: do not let this alarm you, but hear me with patience. As soon as I am in his presence, I will pray him to allow you to lie in the bride-chamber, that I may enjoy your company this one night more. If I obtain that favour, as I hope to do, remember to awake me to-morrow an hour before day, and to address me in these or some such words, “My sister, if you be not asleep. I pray you that till day-break, which will be very shortly, you will relate to me one of the entertaining stories of which you have read so many.” I will immediately tell you one; and I hope by this means to deliver the city from the consternation it is under at present. Dinarzade answered that she would with pleasure act as she required her.

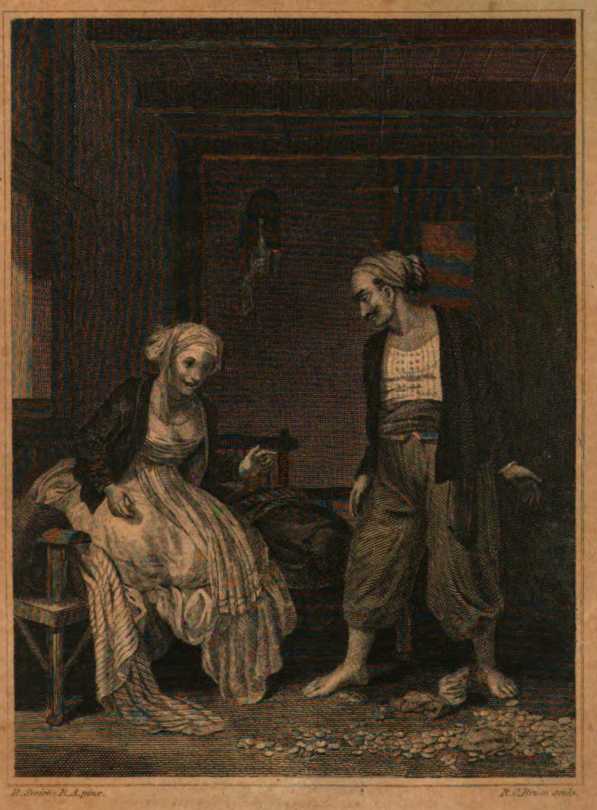

The grand vizier conducted Scheherazade to the palace, and retired, after having introduced her into the sultan’s apartment. As soon as the sultan was left alone with her, he ordered her to uncover her face; he found her so beautiful, that he was perfectly charmed; but perceiving her to be in tears, demanded the reason. Sir, answered Scheherazade. I have a sister who loves me tenderly, and I could wish that she might be allowed to pass the night in this chamber, that I might see her, and once more bid her adieu. Will you be pleased to allow me the consolation of giving her this last testimony of my affection? Schahriar having consented, Dinarzade was sent for, who came with all possible expedition.

An hour before day, Dinarzade failed not to do as her sister had ordered. My dear sister, cried she, if you be not asleep, I pray that until day-break, which will be very shortly, you will tell me one of those pleasant stories you have read. Alas! this may perhaps be the last time that I shall enjoy that pleasure.

Scheherazade, instead of answering her sister, addressed herself to the sultan; Sir, will your majesty be pleased to allow me to afford my sister this satisfaction? With all my heart, replied the sultan. Scheherazade then bade her sister attend, and afterwards addressing herself to Schahriar, proceeded as follows.

FIRST NIGHT.

The Merchant and the Genii.

Sir, —There was formerly a merchant, who had a great estate in lands, goods, and money. He had abundance of deputies, factors, and slaves. He was obliged from time to time to take journeys, and talk with his correspondents: and one day, being under a necessity of going a long journey, about an affair of importance, he took horse, and put a portmanteau behind him, with some biscuits and dates, because he had a great desert to pass over, where he could have no manner of provisions. He arrived, without any accident, at the end of his journey; and having dispatched his affairs, took horse again, in order to return home.

The fourth day of his journey, he was so much incommoded by the heat of the sun, and the reflection of that heat from the earth, that he turned out of the road, to refresh himself under some trees, that he saw in the country. There he found, at the foot of a great walnut tree, a fountain of very clear running water; and alighting, tied his horse to a branch of a tree, and sitting down by the fountain, took some biscuits and dates out of his portmanteau; and as he ate his dates, threw the shells about on both sides of him. When he had done eating, being a good Mussulman, he washed his hands, his face, and his feet, and said his prayers. He had not made an end, but was still on his knees, when he saw a genie appear, all white with age, and of a monstrous bulk; who, advancing towards him with a scimitar in his hand, spoke to him in a terrible voice thus: Rise up, that I may kill thee with this scimitar, as you have killed my son; and accompanied those words with a frightful cry. The merchant, being as much frightened at the hideous shape of the monster as at those threatening words, answered him, trembling, Alas, my good lord, of what crime can I be guilty towards you, that you should take away my life? I will, replies the genie, kill thee, as thou hast killed my son. O, heaven! says the merchant, how should I kill your son? I did not know him, nor ever saw him. Did not you sit down when you came hither? replies the genie. Did not you take dates out of your portmanteau, and, as you ate them, did not you throw the shells about on both sides? I did all that you say, answers the merchant; I cannot deny it. If it be so, replied the genie, I tell thee that thou hast killed my son; and the way was thus: when you threw the nutshells about, my son was passing by, and you threw one of them into his eye, which killed him, and therefore I must kill thee. Ah! my lord, pardon me, cried the merchant. No pardon, answers the genie, no mercy: is it not just to kill him that has killed another? I agree to it, says the merchant, but certainly I never killed your son; and if I have, it was unknown to me, and I did it innocently; therefore I beg you to pardon me, and suffer me to live. No, no, says the genie, persisting in his resolution; I must kill thee, since thou hast killed my son; and then, taking the merchant by the arm, threw him with his face upon the ground, and lifted up his scimitar to cut off his head.

The merchant, all in tears, protested he was innocent, bewailed his wife and children, and spoke to the genie in the most moving expressions that could be uttered. The genie, with his scimitar still lifted up, had so much patience as to hear the wretch make an end of his lamentations, but would not relent. All this whining, says the monster, is to no purpose; though you should shed tears of blood, that shall not hinder me from killing thee, as thou hast killed my son. Why, replied the merchant, can nothing prevail with you? Will you absolutely take away the life of a poor innocent? Yes, replied the genie, I am resolved upon it. As she had spoken these words, perceiving it was day, and knowing that the sultan rose betimes in the morning to say his prayers, and hold his council, Scheherazade held her peace. Lord! sister, says Dinarzade, what a wonderful story is this! The remainder of it, says Scheherazade, is more surprising; and you will be of my mind, if the sultan will let me live this day, and permit me to tell it you the next night. Schahriar, who had listened to Scheherazade with pleasure, says to himself, I will stay till to-morrow, for I can at any time put her to death, when she has made an end of her story. So, having resolved not to take away Scheherazade’s life that day, he rose, and went to his prayers, and then called his council.

THE MERCHANT AND GENIUS.

All this while the grand vizier was terribly uneasy. Instead of sleeping, he spent the night in sighs and groans, bewailing the loss of his daughter, of whom he believed that he himself should be the executioner. And as, in this melancholy prospect, he was afraid of seeing the sultan, he was agreeably surprised when he saw the prince enter the council chamber, without giving him the fatal orders he expected.

The sultan, according to his custom, spent the day in regulating his affairs; and when night came, he went to bed with Scheherazade. Next morning, before day, Dinarzade failed not to address herself to her sister thus: My dear sister, if you be not asleep, I pray you, till day-break, which must be in a very little time, to go on with the story you began last night. The sultan, without staying till Scheherazade asked him leave, bid her make an end of the story of the genie and the merchant, for I long to hear the issue of it. Upon which Scheherazade spoke, and continued the story, as follows:

SECOND NIGHT.

When the merchant saw that the genie was going to cut off his head, he cried out aloud, and said to him, For heaven’s sake, hold your hand! Allow me one word: be so good as to grant me some respite; allow me but time to bid my wife and children adieu, and to divide my estate among them by will, that they may not go to law with one another, after my death; and when I have done so, I will come back to the same place, and submit to whatever you shall please to order concerning me. But, says the genie, if I grant you the time you demand, I doubt you will never return. If you will believe my oath, answers the merchant, I swear by all that is sacred that I will come and meet you here without fail. What time do you demand then? replies the genie. I ask a year, says the merchant; I cannot have less to order my affairs, and to prepare myself to die without regret. But I promise you, that this day twelvemonths I will return under those trees, to put myself into your hands. Do you take heaven to be witness to this promise? says the genie. I do, answers the merchant, and repeat it, and you may rely upon my oath. Upon this, the genie left him near the fountain, and disappeared.

The merchant, being recovered from his fright, mounted his horse, and set forward on his journey; and as he was glad, on the one hand, that he had escaped so great a danger, so he was mortally sorry, on the other, when he thought on his fatal oath. When he came home, his wife and children received him with all the demonstrations of perfect joy; but he, instead of making them suitable returns, fell to weeping bitterly; from whence they readily conjectured that something extraordinary had befallen him. His wife asked the reason of his excessive grief and tears: We are all overjoyed, says she, at your return, but you frighten us to see you in this condition; pray tell us the cause of your sorrow. Alas! replies the husband, the cause of it is, that I have but a year to live; and then he told what had passed between him and the genie, and that he had given him his oath to return at the end of the year, to receive death from his hands.

When they had heard this sad news, they all began to lament heartily. His wife made a pitiful outcry, beat her face, and tore her hair. The children, all in tears, made the house resound with their groans: and the father, not being able to overcome nature, mingled his tears with theirs; so that, in a word, it was the most affecting spectacle that any man could behold.

Next morning, the merchant applied himself to put his affairs in order, and, first of all, to pay his debts. He made presents to his friends; gave great alms to the poor; set his slaves of both sexes at liberty; divided his estate among his children; appointed guardians for such of them as were not come of age; and, restoring to his wife all that was due to her by contract of marriage, he gave her, over and above, all that he could do by law.

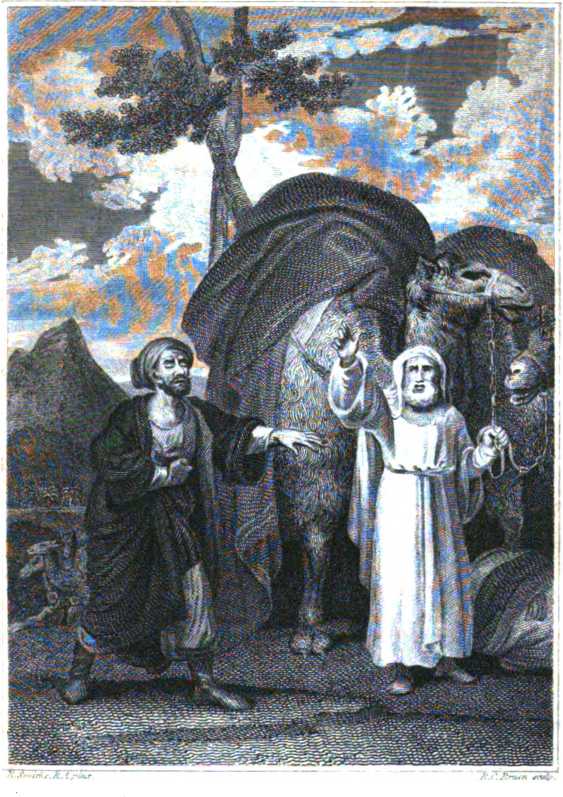

At last the year expired, and go he must. He put his burial clothes in his portmanteau; but never was there such grief seen as when he came to bid his wife and children adieu. They could not think of parting, but resolved to go and die with him; but finding that he must be forced to part with those dear objects, he spoke to them thus: My dear wife and children, says he, I obey the order of Heaven in quitting you; follow my example, submit courageously to this necessity, and consider that it is the destiny of man to die. Having said these words, he went out of the hearing of the cries of his family; and taking his journey, arrived at the place where he promised to meet the genie on the day appointed. He alighted, and setting himself down by the fountain, waited the coming of the genie with all the sorrow imaginable. Whilst he languished in this cruel expectation, a good old man, leading a hind, appeared, and drew near him. They saluted one another; after which the old man says to him, Brother, may I ask you why you are come into this desert place, where there is nothing but evil spirits, and by consequence you cannot be safe? To look upon these fine trees, indeed, one would think the place inhabited; but it is a true wilderness, where it is not safe to stay long.

The merchant satisfied his curiosity, and told him the adventure which obliged him to be there. The old man listened to him with astonishment, and when he had done, cried out, This is the most surprising thing in the world; and you are bound with the most inviolable oath; however, I will be witness of your interview with the genie. And sitting down by the merchant, they talked together. But I see day, says Scheherazade, and must leave off; yet the best of the story is to come. The sultan, resolving to hear the end of it, suffered her to live that day also.

THIRD NIGHT.

Next morning, Dinarzade made the same request to her sister as formerly: My dear sister, says she, if you be not asleep, tell me one of those pleasant stories that you have read. But the sultan, willing to understand what followed between the merchant and the genie, bid her go on with that, which she did, as follows:

Sir, while the merchant, and the old man who led the hind, were talking, they saw another old man coming to them, followed by two black dogs. After they had saluted one another, he asked them what they did in that place. The old man with the hind, told him the adventure of the merchant and genie, with all that had passed between them, particularly the merchant’s oath. He added, that it was the day agreed on, and that he was resolved to stay and see the issue.

The second old man, thinking it also worth his curiosity, resolved to do the like: he likewise sat down by them; and they had scarce began to talk together, but there came a third old man, who addressing himself to the two former, asked why the merchant that sat with them looked so melancholy. They told him the reason of it, which appeared so extraordinary to him, that he also resolved to be witness to the result; and for that end sat down with them.

In a little time, they perceived in the field a thick vapour, like a cloud of dust raised by a whirlwind, advancing towards them, which vanished all of a sudden, and then the genie appeared; who, without saluting them, came up to the merchant with a drawn scimitar, and taking him by the arm, says, Get thee up, that I may kill thee, as thou didst my son. The merchant and the three old men, being frightened, began to lament, and to fill the air with their cries. Here Scheherazade, perceiving day, left off her story; which did so much whet the sultan’s curiosity, that he was absolutely resolved to hear the end of it, and put off the sultaness’s execution till the next day.

Nobody can express the grand vizier’s joy when he perceived that the sultan did not order him to kill Scheherazade: his family, the court, and all the people in general, were astonished at it.

FOURTH NIGHT.

Towards the end of the following night, Dinarzade failed not to awake the sultaness. My dear sister, says she, if you be not asleep, pray tell me one of your fine stories. Then Scheherazade, with the sultan’s permission, spoke as follows:

Sir, when the old man who led the hind saw the genie lay hold of the merchant, and about to kill him without mercy, he threw himself at the feet of the monster, and, kissing them, says to him, Prince of genies, I most humbly request you to suspend your anger, and do me the favour to hear me. I will tell you the history of my life, and of the hind you see; and if you think it more wonderful and surprising than the adventure of the merchant you are going to kill, I hope you will pardon the poor unfortunate man the third of his crime. The genie took some time to consult upon it, out answered at last, Well, then, I agree to it.

The History of the first Old Man, and the Hind.

I shall begin, then, says the old man; listen to me, I pray you, with attention. This hind you see is my cousin; nay, what is more, my wife: she was only twelve years or age when I married her, so that I may justly say, she ought as much to regard me as her father, as her kinsman and husband.

We lived together twenty years without any children; yet her barrenness did not hinder my having a great deal of complaisance and friendship for her. The desire of having children only made me buy a slave, by whom I had a son, who was extremely promising. My wife being jealous, conceived a hatred for both mother and child, but concealed it so well, that I did not know it till it was too late.

Mean time my son grew up, and was ten years old, when I was obliged to undertake a journey. Before I went, I recommended to my wife, of whom I had no mistrust, the slave and her son, and prayed her to take care of them during my absence, which was for a whole year. She made use of that time to satisfy her hatred; she applied herself to magic, and when she knew enough of that diabolical art to execute her horrible contrivance, the wretch carried my son to a desolate place, where by her enchantments, she changed my son into a calf, and gave him to my farmer to fatten, pretending she had bought him. Her fury did not stop at this abominable action, but she likewise changed the slave into a cow, and gave her also to my farmer.

At my return, I asked for the mother and child: Your slave, says she, is dead; and as for your son, I know not what has become of him. I have not seen him these two months. I was troubled at the death of the slave, but my son having only disappeared, as she told me, I was in hopes he would return in a little time. However, eight months passed, and I heard nothing of him. When the festival of the great Bairam happened, to celebrate the same, I sent to my farmer for one of the fattest cows, to sacrifice, and he sent me one accordingly. The cow which he brought me was my slave, the unfortunate mother of my son. I tied her, but as I was going to sacrifice her, she bellowed pitifully, and I could perceive streams of tears run from her eyes. This seemed to me very extraordinary; and finding myself, in spite of all I could do, inspired with pity, I could not find in my heart to give her a blow, but ordered my farmer to get me another.

My wife, who was present, was enraged at my compassion, and, opposing herself to an order which disappointed her malice, she cries out, What are you doing, husband? Sacrifice that cow: your farmer has not a finer, nor one fitter for that use. Out of complaisance to my wife, I came again to the cow, and, combating my compassion, which suspended the sacrifice, was going to give her the fatal blow, when the victim, redoubling her tears and bellowing, disarmed me a second time. Then I put the mallet into the farmer’s hands, and bid him take and sacrifice her himself, for her tears and bellowing pierced my heart.

The farmer, less compassionate than I, sacrificed her; and when he flayed her, found her to be nothing but bones, though to us she seemed very fat. Take her to yourself, says I to the farmer, I quit her to you; give her in alms, or which way you will; and if you have a very fat calf, bring it me in her stead. I did not inform myself what he did with the cow; but, soon after he took her away, he came with a very fat calf. Though I knew not the calf was my son, yet I could not forbear being moved at the sight of him. On his part, as soon as he saw me, he made so great an effort to come to me, that he broke his cord, threw himself at my feet, with his head against the ground, as if he meant to excite my compassion, conjuring me not to be so cruel as to take his life; and did as much as was possible for him to do, to signify that he was my son.

I was more surprised and affected with this action, than with the tears of the cow; I felt a tender pity, which made me interest myself for him, or, rather, nature did its duty. Go, says I to the farmer, carry home that calf, take great care of him, and bring me another in his place immediately.

As soon as my wife heard me say so, she immediately cried out, What do you do, husband? Take my advice, sacrifice no other calf but that. Wife, says I, I will not sacrifice him; I will spare him, and pray do not you oppose it. The wicked woman had no regard to my desire; she hated my son too much to consent that I should save him. I tied the poor creature, and taking up the fatal knife —Here Scheherazade stopped, because she perceived daylight.

Then Dinarzade said, Sister, I am enchanted with this story, which so agreeably calls for my attention. If the sultan will suffer me to live to-day, answers Scheherazade, what I have to tell to-morrow will divert you abundantly more. Schahriar, curious to know what would become of the old man’s son that led the hind, told the sultaness he would be very glad to hear the end of that story next night.

FIFTH NIGHT.

When day began to draw near, Dinarzade put her sister’s orders in execution very exactly, who, being awaked, prayed the sultan to allow her to give Dinarzade that satisfaction; which the prince, who took so much pleasure in the story himself, willingly agreed to.

Sir, then, says Scheherazade, the first old man who lead the hind, continuing his story to the genie, to the other two old men, and the merchant, proceeded thus: I took the knife, says he, and was going to strike it into my son’s throat; when turning his eyes bathed with tears, in a languishing manner towards me, he affected me so that I had no strength to sacrifice him, but let the knife fall, and told my wife positively that I would have another calf to sacrifice, and not that. She used all endeavours to make me change my resolution; but I continued firm, and pacified her a little, by promising that I would sacrifice him against the Bairam next year.