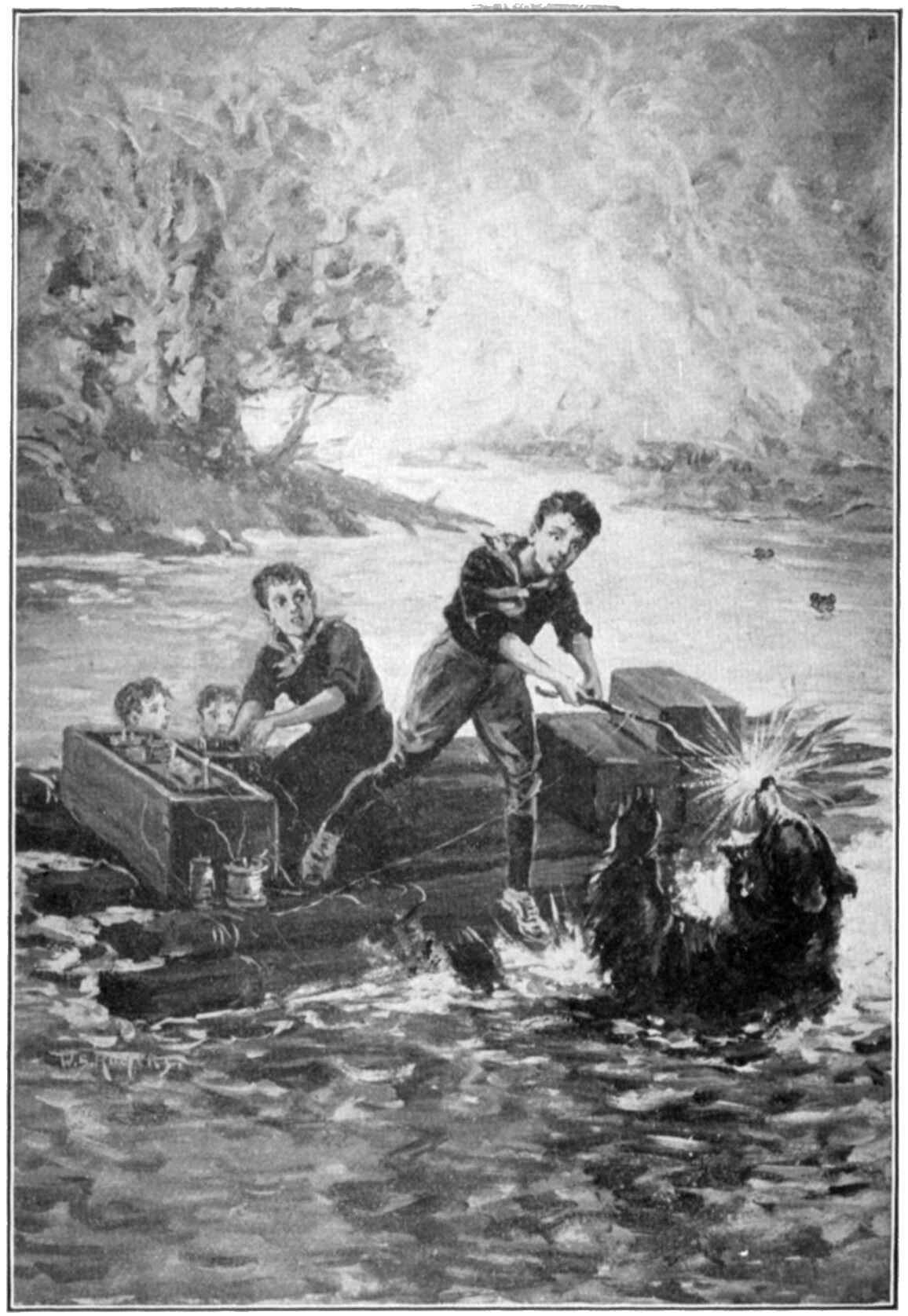

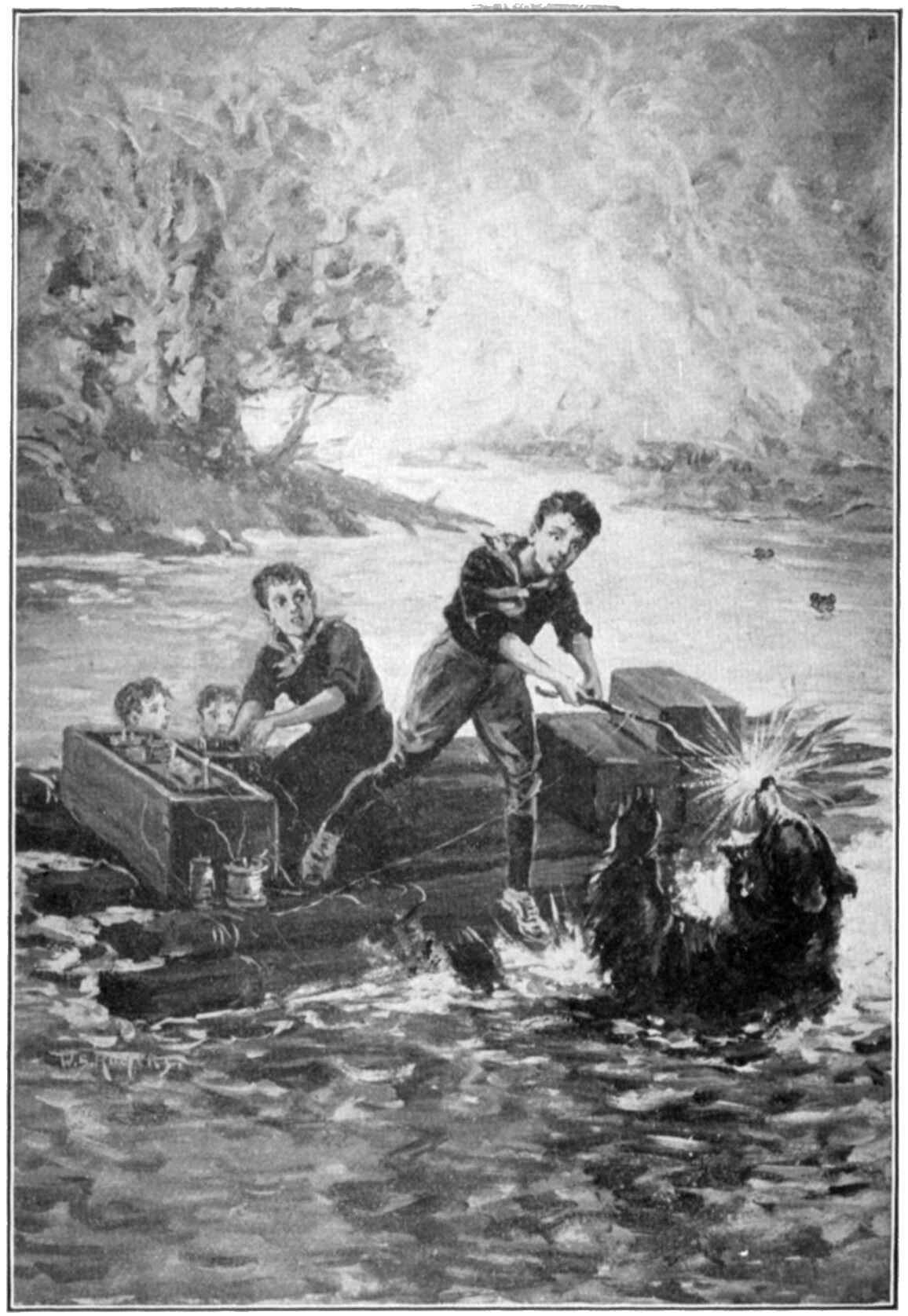

A blue streak crackled between the terminal and the bear’s nose.

A blue streak crackled between the terminal and the bear’s nose.

There are two aspects of radio as a vital factor in saving life and property which are very vividly brought out in this interesting volume of the Radio Boys Series—namely its use in connection with the patrol work in detecting forest fires, and the regular international ice patrol in the dangerous waters of the north Atlantic. So splendidly have these two functions of radio been developed, that they have become accepted as commonplace in our lives, and it is only by such stories as “The Radio Boys with the Forest Rangers” that we are awakened to their importance.

Another interesting account in this volume is the detailing of the experimental work recently carried out at the Schenectady broadcasting station, when the voice which was radiated through the ether was actually reproduced from an ordinary moving picture film.

Just think of the marvel of this. The words of the speaker were photographed on a film, and held in storage for several weeks, before the streaks of light were re-converted into electric impulses, and then transferred into faithful reproduction of speech in a million homes. How great are the possibilities thus unfolded to the immediate future. Here we have a record that is better than that of the phonograph, because there will be no scratchiness from a needle in its reproduction to mar the original tones.

The period over which the Radio Boys Series has been produced has seen the most remarkable all-around development of radio in history. Now upon the publication of the latest volume in the series there comes the announcement that a Hungarian scientist has been successful in transmitting an actual picture of a current event as it is occurring.

We are upon the very threshold of TELEVISION—the system which converts the etheric vibrations that correspond to vision, and translates them into impulses of electric energy which can be radiated through space, and picked up by specially designed radio receivers. The system of course can also be applied to telegraph and telephone wires.

The development of this promising invention means that in the near future we will be able to see the person to whom we are speaking, whether we use the ordinary telephone or the wireless telephone as a means of communication. This truly is an age of radio wonders!

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I. | A Sudden Alarm |

| II. | Almost a Tragedy |

| III. | Quick Work |

| IV. | Radio, the Fire-Conqueror |

| V. | The Wonderful Science |

| VI. | Thrashing a Bully |

| VII. | Good Riddance |

| VIII. | At Risk of Life |

| IX. | Off for Spruce Mountain |

| X. | The Falling Bowlder |

| XI. | Forest Radio |

| XII. | The Ice Patrol |

| XIII. | Winning Their Spurs |

| XIV. | The Crouching Wildcat |

| XV. | An Underground Mystery |

| XVI. | Swallowed up by the Darkness |

| XVII. | An Old Enemy |

| XVIII. | Pinned Down |

| XIX. | Fire |

| XX. | A Terrible Battle |

| XXI. | Plunged in the Lake |

| XXII. | Fighting Off the Bears |

| XXIII. | A Desperate Chance |

| XXIV. | The Blessed Rain |

| XXV. | Snatched from Death |

“Say, fellows!” exclaimed Bob Layton, as he bounded down the school steps, three steps at a time, his books slung by a strap over his shoulder, “what do you think——”

“We never think,” interrupted Herb Fennington. “At least that’s what Prof. Preston told our class the other day.”

“Speak for yourself,” broke in Joe Atwood. “As for me, thinking is the best thing I do. I’ve got Plato, Shakespeare and the rest of those high-brows beaten to a frazzle.”

“Sure thing,” mocked Jimmy Plummer. “But don’t think because you have notions in your head that you’re a whole department store.”

Bob surveyed his comrades with a withering glare.

“When you funny fellows get through with your per-per-persiflage——” he began.

“Did you get that, fellows?” cried Jimmy. “Persiflage! Great! What is it, Bob? A new kind of breakfast food?”

“I notice it almost choked him to get it out,” remarked Joe, with a grin.

“Words of only one syllable would be the proper size for you fellows,” retorted Bob. “But what I was going to say was that I just heard from Mr. Bentley. You know the man I mean, the one that we saw at my house some time ago and who gave us all that dope about forest fires.”

“Oh, you mean the forest ranger!” broke in Joe eagerly. “Sure, I remember him. He was one of the most interesting fellows I ever met.”

“I’ll never forget what he told us about radio being used to get the best of forest fires,” said Herb. “I could have listened to him all night when once he got going.”

“He’s a regular fellow, all right,” was Jimmy’s comment. “But what about him? When did you see him?”

“I haven’t seen him yet,” explained Bob. “Dad got a letter from him yesterday. You know dad and he are old friends. Mr. Bentley asked dad to remember him to all the radio boys, and said to tell us that he was going to give a talk on radio and forest fires from the Newark broadcasting station before long and wanted us to be sure to listen in.”

“Will we?” returned Joe enthusiastically. “You bet we will! But when’s the talk coming off?”

“Mr. Bentley said that the exact date hadn’t been settled yet,” replied Bob. “But it will be some time within the next week or ten days. He promised to let us know in plenty of time.”

“I wouldn’t miss it for a farm,” chimed in Jimmy. “But if it’s great to hear about it, what must it be to be right in the thick of the work as he is? Some fellows have all the luck.”

“Perhaps there are times when he doesn’t think it luck,” laughed Bob. “Half a dozen times he’s just escaped death by the skin of his teeth. But look, fellows, who’s coming.”

The others followed the direction of Bob’s glance and saw a group of three boys coming toward them. One, who seemed to be the leader, was a big hulking fellow with a pasty complexion and eyes that were set too close together. At his right was a boy slightly younger and on the outside another, younger yet, with a furtive and shifty look.

“Buck Looker, Carl Lutz and Terry Mooney!” exclaimed Bob. “I haven’t come across them since we got back from the woods.”

“Guess they’ve kept out of our way on purpose,” remarked Joe. “You can bet they’ve felt mighty cheap over the way you put it over on them in the matter of those letters.”

“‘There were three crows sat on a tree,’” chanted Jimmy.

“‘And they were black as crows could be,’” finished Herb.

The objects of these unflattering remarks had caught sight of the four boys, and as at the moment they were at a corner, they hesitated slightly, as though they were minded to turn down the side street. But after conferring for a moment, they kept on, their leader assuming a swaggering air. And whereas before the three had been simply conversing as they came along, they now began a boisterous skylarking, snatching each other’s caps and knocking each other about.

Just as they came abreast of the other group, Buck gave Lutz a violent shove and sent him with full force against Joe, who was nearest. The latter was taken unawares and almost knocked off his feet.

Joe had a quick temper, and the malicious wantonness of the act made his blood boil. He rushed toward Buck, who backed away from him, his face gradually losing the grin it wore.

“What did you mean by that?” demanded Joe, clenching his fist.

“Aw, what’s the matter with you?” growled Buck. “How did I know he’d knock against you? It was just an accident. Why didn’t you get out of the way?”

“Accident nothing,” replied Joe. “You’re the same sneak that you always were, Buck Looker. You planned that thing when you stopped and talked together. And now something’s going to happen to you, and it won’t be an accident, either!”

He advanced upon Buck, who hurriedly retreated to the middle of the street and looked about him for a stone.

“You keep away from me, Joe Atwood, or I’ll let you have this,” he half snarled, half whined, stooping as he spoke and picking up a stone as big as his fist.

“You coward!” snapped Joe, still advancing. “Don’t think that’s going to save you from a licking.”

Just then a sharp warning came from Bob.

“Stop, Joe!” he cried. “Here comes Dr. Dale.”

A look of chagrin came into Joe’s face and a look of relief into Buck’s, as they saw the pastor of the Old First Church turning a corner and coming in their direction. Fighting now was out of the question.

“Lucky for you that he turned up just now,” blustered Buck, his old swagger returning as he felt himself safe. “I was just going to give you the licking of your life.”

Joe laughed sarcastically, and before the biting contempt in that laugh Buck flushed uncomfortably.

“Stones seem to be your best friends,” said Joe. “I remember how you used them in the snowballs when you smashed that plate-glass window. And I remember too how you tried to fib out of it, but had to pay for the window just the same.”

By this time Dr. Dale was within earshot, and Buck and his companions slunk away, while Joe picked up his books and rejoined his comrades.

The doctor’s keen eyes had seen that hostilities were threatening but now that they had been averted he had too much tact and good sense to ask any questions.

“How are you, boys?” he greeted them, with the genial smile that made him a general favorite. “Working hard at your studies, I suppose.”

“More or less hard,” answered Bob. “Though probably not nearly as hard as we ought to,” he added.

The doctor’s eyes twinkled.

“Very few of us are in danger of dying from overwork, I imagine,” he said. “But I’ve known you chaps to work mighty hard at radio.”

“That isn’t work!” exclaimed Joe. “That’s fun.”

“Sure thing,” echoed Herb.

“I’ll tell the world it is,” added Jimmy.

“We can’t wait for a chance to get at it,” affirmed Bob.

“Seems to be unanimous,” laughed the doctor. “I feel the same way myself. I never get tired of it, and I suppose the reason is that something new is turning up all the time. One magical thing treads close on the heels of another so that there’s no such thing as monotony. There isn’t a week that passes, scarcely a day in fact, that something doesn’t spring up that makes you gasp with astonishment. Your mind is kept on the alert all the time, and that’s one thing among many others that makes the charm of radio.”

“I see that they’re using it everywhere in the Government departments,” remarked Bob.

“Every single one of them,” replied the doctor. The President himself has had a set installed and uses it constantly. The head of the army talks over it to every fort and garrison and camp in the United States. The Secretary of the Navy communicates by it with every ship and naval station in the Atlantic and Pacific as far away as Honolulu and the Philippines. The Secretary of Agriculture sends out information broadcast to every farmer in the United States who happens to have a radio receiving set. And so with every other branch of the Government.

“That reminds me,” he went on, warming to his subject, as he always did when he got on his favorite theme, “of a talk I had the other day on the train with a man in the Government Air Mail Service. He was a man, too, who knew what he was talking about, for he was the first man to fly the mail successfully both ways between New York and Washington on the initial air mail run.

“He told me that plans are now on foot to fly mail across the continent, daily, both ways, in something like twenty-four hours. Just think of that! From coast to coast in twenty-four hours! That’s five times as fast as an express train does it, and a hundred times as fast as the old pioneers with their prairie schooners could do it.

“But in order to do this, a gap of about a thousand miles must be flown at night. And here is where the radio comes in. In order to be able to find his way in the dark, the flier uses his ears instead of his eyes. He wears a radio-telephone helmet that excludes the noise of the motor. A coil of wire is wound on his plane and is connected to a radio receiving set on board. Along his route at stated intervals are transmission stations whose signals come up to the aviator. When the pilot’s direction finder is pointed toward these stations that mark out his path the signals are loudest. The minute he begins to get off his path, either on one side or the other, the signals begin to get weaker.

“Now, you see, all that the pilot has to do is to keep along the line where the signals are loudest. If he goes a little to the right and finds the signals getting weaker, he knows he must shift a little back to the left again until he gets on the loudest sound line. The same process has to be followed if he gets off to the left. You see, it’s just as if the plane were running along a trolley line miles below it. Only in this case the trolley line instead of being made of wire is made of sound. That loudest sound line will stretch right across the continent, and all the flier has to do is to run along it. If he does this, he’ll get to his destination just as certainly as does the train running along the rails that lead to the station.”

“It’s wonderful!” exclaimed Bob.

“Sounds like witchcraft,” commented Joe.

“You see how easy that makes it for the aviator,” resumed the doctor. “It may be as black as Egypt, but that makes no difference to him. He may be shrouded in fog, but that can’t bewilder him or shunt him off his course. He can shut his eyes and get along just as well. All he’s got to do is not to go to sleep. And when the dawn breaks he finds himself a thousand miles or so nearer to his destination.”

“Suppose he gets to his landing field in the night time or in a heavy fog,” said Joe thoughtfully. “How’s he going to know where to come down?”

“Radio attends to that too,” replied the doctor. “At each landing place there will be a peculiar kind of radio transmission aerial, which transmits vertically in the form of a cone that gains diameter as it goes higher. At a height of about three thousand feet above the field, such a cone will have a diameter of nearly half a mile. In other words this sound cone will be like a horn of plenty with the tip on the ground and its wide opening up in the air. The pilot will sail right into this wide mouth of the horn which he will recognize by its peculiar signal. Then he will spiral down on the inside of the cone, or horn, until he reaches the tip on the ground. This will be right in the middle of the landing field, and there he is safe and sound.

“But here I am at my corner,” Dr. Dale concluded. “And perhaps it’s just as well, for when I get to talking on radio I never know when to stop.”

He said good-by with a wave of his hand while the four boys looked after him with respect and admiration.

“He’s all to the good, isn’t he?” said Bob.

“You bet he is!” agreed Joe emphatically.

“He’s—Hello! what’s the matter?”

A sudden commotion was evident up the street. People were running excitedly and shouting in consternation.

The boys broke into a run in the direction followed by the crowd.

“What’s happened?” Bob asked, as he came abreast of a panting runner.

“There’s been an explosion up at Layton’s drug store,” the man replied. “They say an ammonia tank burst and everybody up there was killed.”

Bob’s face grew ashen.

“My father!” he cried, and ran toward the store in an agony of grief and fear.

With his heart beating like a triphammer and his lungs strained almost to bursting, Bob ran on as he had never run before. And yet it seemed to him as though he were terribly slow and that his limbs were dragging as though he were in a nightmare.

Joe, Herb and Jimmy were close behind him as he rushed along, elbowing his way through the throng that grew denser as he neared the building in which his father’s store was located. The alarm had spread with almost lightning rapidity, and it seemed as if half the people of the town were on their way to render whatever help might be possible.

In what seemed to be an age, but was in reality less than two minutes, the boys had reached the store. What they saw was not calculated to relieve their fears. Choking fumes of what seemed to be ammonia were pouring out into the streets through the store windows that had been shattered by the explosion. People who had come within twenty feet of the place were already choking and staggering, and one man who had approached too near had fallen prone on the sidewalk and was being dragged by others out of the danger zone.

Bob plunged headforemost through the crowd and was making for the door when cries of warning rose and many hands grasped him and pulled him back.

“Let me go!” he shouted frantically. “My father is in there! Perhaps he is dying! Let me go!”

But despite his frantic appeals, his captors held him until he unbuttoned his jacket and, wriggling out of it like an eel, again made a dash for the door. The fumes struck him full in the face, and he staggered as under a blow. Before he could recover and make another attempt, strong arms were around him and this time held him fast.

“No use, Bob, my boy,” said the firm but kindly voice of Mr. Talley, a warm friend both of Bob and his father. “It’s simply suicide to go in there until the fumes thin out some. Here comes the fire engine now. The firemen have smoke helmets that will protect them against the fumes, and if your father is in there, they’ll have him out quickly.”

Up the street, with a great clangor of bells, came tearing the engine. The crowd made way for it, while the firemen leaped from the running board before it came to a stop.

“I’ve got to do something!” gasped Bob. “Let me go!”

“No use, my boy,” said Mr. Talley.

Just then Joe had an inspiration.

“Bob,” he shouted, “there’s that passageway from the old factory that leads right to the back of the store. Perhaps we can get in from that. What do you say?”

In a flash, Bob remembered. He tore himself loose from Mr. Talley’s grasp and was off after Joe, running like a deer.

And while the boys are frantically seizing this chance of rescue, it may be well for the benefit of those who have not read the preceding volumes of this series to tell briefly who the Radio Boys were and what had been their adventures up to the time this story opens.

Bob Layton, who at this time was about sixteen years old, had been born and brought up in Clintonia, a wide-awake, thriving town with a population of over ten thousand. It was pleasantly located on a little stream called the Shagary River, less than a hundred miles from New York City. Bob’s father was a leading citizen of the town and a prosperous druggist and chemist. No one in the town was more highly respected, and although not rich, he had achieved a comfortable competence.

Bob was a general favorite with the people of the town because of his sunny temperament and his straightforward, manly character. He was tall, sinewy, of dark complexion and a leader among the young fellows of his own age in all athletic sports, especially in baseball and football. On the school nine and eleven he was a pillar of strength, cool, resourceful and determined. His courage was often tested and never failed to meet the test. He never looked for trouble, but never dodged it when it came.

His closest friend was Joe Atwood, whose father was a prominent physician of Clintonia. Joe was of fair complexion, with merry blue eyes that were usually full of laughter. They could flash ominously on occasion, however, for Joe’s temper was of the hair-trigger variety and sometimes got him into trouble. He seldom needed a spur, but more than once a brake was applied by Bob, who had much more coolness and self-control. The pair got on excellently together and were almost inseparable.

Closely allied to this pair of friends were two other boys, slightly younger but near enough to their ages to make congenial comrades. One of these was Herb Fennington, whose father kept the largest general store in town. Herb was a jolly likeable young fellow, none too fond of hard work, but full of jokes and conundrums that he was always ready to spring on the slightest encouragement and often without any encouragement at all.

The fourth member of the group was Jimmy Plummer, whose father was a carpenter and contractor. Nature never intended Jimmy for an athlete, for he was chunky and fat and especially fond of the good things of life; so much so in fact that he went by the nickname of “Doughnuts” because of his liking for that delectable product. He was rollicking and good-natured, and the other boys were strongly attached to him.

They would have been warm friends under any circumstances, but they were drawn still more closely together because of their common interest in the science of radio. The enthusiasm that swept the country when the marvels of the new science became known caught them in its grip and made them the most ardent of radio “fans.” They absorbed anything they could hear or read on the subject, and almost all their spare time was spent in delving into the mysteries of this miracle of modern days.

While the Radio Boys, as they soon began to be called, were popular with and friendly to almost all the other Clintonia boys, there was one group in the town with whom they were almost constantly at odds. Buck Looker and two of his cronies, Carl Lutz and Terry Mooney, were the special enemies of the Radio Boys and never lost an opportunity, if it were possible to bring it about, of doing them mischief in a mean and underhand way.

Buck’s father was one of the richest men in the town, and this enabled Buck to lord it over Lutz, slightly younger than he, and Mooney, younger yet, both of them sneaks and trouble-makers, who cringed to Buck because of his father’s wealth.

The boys might not have made such rapid progress with their radio had it not been for the help and inspiration given them by Dr. Dale, the pastor of the Old First Church, who was himself keenly interested and very proficient in the science. He understood boys, liked them and was always ready to help them out when they were perplexed in any phase of their sending or receiving. They in turn liked him thoroughly, a liking that was increased by their knowledge that he had been a star athlete in his college days.

Another thing that stimulated their interest in radio was the offer of prizes by Mr. Ferberton, the member of Congress for their district, for the best radio sets turned out by the boys themselves. Herb was a bit lazy and kept out of the contest, but Bob, Joe and Jimmy entered into the competition with zest.

An unexpected happening just about this time led the boys into a whole train of adventures. A visitor in town, a Miss Nellie Berwick, lost control of the automobile she was driving and the machine dashed through the windows of a store. A fire ensued and the girl might have lost her life had it not been for the courage of the Radio Boys who rescued her from her shattered car.

How the boys learned of the orphan girl’s story; how by the use of the radio they got on the track of the fellow who had defrauded her, how Buck Looker and his gang attempted to ruin their chances in the radio competition, can be read in the first volume of this series, entitled: “The Radio Boys’ First Wireless; Or, Winning the Ferberton Prize.”

Summer had come by that time and the Radio Boys went with their parents to a little bungalow colony on the seashore. They carried their radio sets with them, though they had no inkling of what an important and thrilling part those sets were to play. What advances they made in the practical knowledge of the science; how in a terrible storm they were able to send out radio messages that brought help to the steamer on which their own people were voyaging; all these adventures are told in the second book of the series, entitled: “The Radio Boys at Ocean Point; Or, the Message that Saved the Ship.”

Several weeks still remained of the vacation season, and the boys had an opportunity of saving the occupants of a rowboat that had been heartlessly run down by thieves in a stolen motor-boat. Two of the rescued people were Larry Bartlett and a friend who were vaudeville actors, between whom and the boys a warm friendship sprang up. How they exonerated Larry from a false charge of theft brought by Buck Looker; how when an accident crippled Larry they obtained for him a chance to use his talents in a broadcasting station; how this led eventually to themselves being placed on the program can be seen in the third volume of the series, entitled: “The Radio Boys at the Sending Station; Or, Making Good in the Wireless Room.”

The boys reluctantly bade farewell to the beach and returned to Clintonia for the fall term of high school. But their studies had not continued for many weeks before an epidemic in the town made it necessary to close the school for a time. This proved a blessing in disguise, for it gave the Radio Boys an opportunity to make a visit to Mountain Pass, a popular resort in the hills. Here they made the acquaintance of a Wall Street man to whom they were able to render a great service by thwarting a gang of plotters who were working for his undoing. By the use of radio they were able to summon help and save a life when all the passes were blocked with snow. They trapped Buck Looker and his gang in a clever way just when it seemed that the latter’s plots were going through, and had a host of other adventures, all narrated in the fourth volume of the series, entitled: “The Radio Boys at Mountain Pass; Or, the Midnight Call for Assistance.”

Shortly after the boys had returned to Clintonia, they were startled to learn that the criminal Dan Cassey, with two other desperate characters, had escaped from jail. A series of mysterious messages over the radio put them on the trail of the convicts. How well the boys played their part in this thrilling and dangerous work is told in the fifth volume of the series, entitled: “The Radio Boys Trailing a Voice: Or, Solving a Wireless Mystery.”

And now to return to Bob and Joe, as, panting with their exertions and followed by their comrades, they rushed toward the old factory from which they hoped to reach the rear of Mr. Layton’s store.

The place had formerly been used by a chemical concern with which Mr. Layton was connected in an advisory capacity. He was skilled in his profession and his services had been highly appreciated. An amalgamation of several similar concerns had now been effected, and for purposes of economy the headquarters of the company had been removed to another city and the old factory had been abandoned.

While it had been in operation it had been connected with the rear of Mr. Layton’s store by an underground tunnel that was just large enough to permit easy access from one place to the other. A large door closed it at the factory end, while at the rear of the store a flight of steps led up to a large, square trapdoor set in the floor.

Bob’s mind was in a tumult of emotions as he ran along. It was a long time since he had been in the factory, and in the confusion of his thoughts he could not remember whether the great door was locked or not. And even if he succeeded in gaining access there, the possibility remained that the trapdoor at the other end might prove to be bolted. In either case, it would be impossible to get into the store until it was too late to be of any use. And at this very moment his father might be gasping out his life in those terrible fumes!

He reached the factory, flung himself through the open outer door and made for the door leading into the passageway. He pulled frantically at the knob, but it resisted his efforts. Was it locked, after all? The answer was supplied the next moment when Joe added his strength to Bob’s, and yielding to their united efforts the heavy door, groaning and creaking on its rusted hinges, swung outward. Jimmy and Herb had been outdistanced and were nowhere to be seen.

With an inward prayer of gratitude Bob plunged into the dusty passage that had been unused for years. Fortunately it ran in a straight line, and although he had no light he had little difficulty in finding his way, despite the fact that he abraded his hands and shins against the sides, owing to the rate at which he was going. But in his excitement the youth did not even feel the bruises.

In a moment he had reached the foot of the steps, bounded up them and was pushing with all his might at the trapdoor at the head. It yielded under his efforts enough to show that it was not bolted. For a moment though, it seemed as though it might as well have been, for some heavy object or objects lying on it defied his strength. By this time Joe was at his side, and together they strained at the door, while the veins stood out in ridges along their arms and shoulders. Had they not been strung up to such a pitch, they could never have succeeded, but sheer desperation gave them strength far beyond the normal, and gradually they forced the trap upward and rolled over to one side what had been holding it down.

In a twinkling both the boys were up in the store. The fumes had thinned out somewhat, but were still thick enough to make them gasp and choke. Whatever they had to do must be done quickly.

The room into which the boys had leaped was a small laboratory fitted up in the rear of the store. As Bob’s eyes ranged about, they fell on two bodies lying at the side of the trapdoor. These were what had been holding the trapdoor down. A glance sufficed to show Bob that one was the body of his father and the other that of Thompson, one of the clerks of the store.

In a moment Bob was on his knees at his father’s side.

“Dad!” he cried. “Dad! Are you alive? Speak to me!”

But no answer came from the motionless lips.

Bob put his hand on his father’s heart. It was still beating, though slowly and fitfully.

“Quick, Joe,” shouted Bob. “Help me get him out of this.”

Joe responded instantly, but at this moment the firemen, who had been groping about in the blinding fumes, stumbled into the room. Willing hands grasped the bodies of Mr. Layton and the clerk and carried them out to the sidewalk. Here a cordon was quickly formed to keep the crowd back.

The telephone had been busy while these events were happening, and all the physicians in the town had been summoned. Oxygen tanks and pulmotors had also been requisitioned from the hospital and the ambulance containing them arrived just as the rescues were being effected. Dr. Atwood, Joe’s father, and Dr. Ellis were already on the scene, and the former took charge of Mr. Layton, while Dr. Ellis devoted himself to the clerk.

Then followed moments full of heartbreaks for Bob, while he waited for the doctor’s verdict. Both the physicians worked with skill and quickness, but it was some time before their efforts were rewarded.

Joe placed his arm affectionately about his friend’s shoulder, while Herb and Jimmy also added words of encouragement. Bob tried to be brave, but his heart was rent with anguish while he waited for the words that would mean life or death.

Finally, after what seemed an age, Dr. Atwood rose to his feet with relief and satisfaction in his eyes.

“He will live,” he said, and with the words Bob felt as though the weight of a thousand tons had been lifted from his heart. “For a while it was a case of touch or go, but you got him out just in time. Two minutes more and it would have been too late. All he needs now is rest and good nursing, and he’ll be as well as ever in a couple of weeks.”

At the same moment Mr. Layton opened his eyes and looked around. His gaze was vague and uncertain at first, but as his eyes fell upon Bob they lighted up with a smile of recognition, and he tried to reach out his hand to him. But he was too weak, and the hand fell helplessly at his side. In a moment Bob was kneeling beside him and patting his hand.

“Dad, Dad,” he cried. “Thank God!” And then because his heart was too full he could say no more.

Dr. Ellis also announced that Thompson was out of danger, and the patients were lifted into the ambulance and conveyed to their respective homes.

The week that followed was a trying one for Bob and his mother. The latter was assiduous at the bedside of her husband, who, although steadily recovering, mended slowly. Bob, apart from his anxiety over his father’s condition, found a great deal of responsibility placed on his shoulders. The store had to be repaired and put in order for carrying on the business. Insurance also had to be attended to, and a host of other details forced themselves upon his attention. Fortunately the head clerk, a Mr. Trent, who had been absent at the time of the accident, was an expert pharmacist and a good manager; so that, after the first few days, business had been resumed and was going on as usual. Still, Bob was heavily taxed with matters that were comparatively new to him. He rose to the occasion, however, in a way that made his father proud of him.

“You’re my right hand, Bob,” his father said to him one day, as he sat by his bedside. “I don’t know what I’d do without you. You’ve carried on affairs as though you were an old hand at the business. It’s too bad that all this had to be shoved on you so suddenly, but you’ve stood the test nobly.”

“Oh, that’s nothing,” replied Bob, making light of the matter, though his father’s praise was sweet to him. “All you’ve got to do is to get well and nothing else matters.”

“I’ve been trying to figure out how the thing happened,” mused his father, “but to save my life I can’t understand it. All I was conscious of was a terrific noise and a shock as though I had been hit on the head by a triphammer. Then everything went black and I knew nothing more until I saw you standing beside me on the sidewalk.”

“Don’t excite yourself by trying to remember,” replied Bob soothingly. “The important thing is that you’re alive. All the rest is nothing.”

Bob’s chums had also felt an anxiety only second to his own. They were full of sympathy and showed it by doing everything they could to help him and lighten the load that he was carrying. All the spare time they had they spent with him at his home or at the store. The calamity had served to cement the ties that bound the friends together.

By the time a week had passed, matters took an upward turn. Mr. Layton began to progress rapidly, and Dr. Atwood prophesied that in a few days he could begin to attend to business, although at first he could devote only a few hours a day to it, lengthening the time as his strength came back. Affairs in the Layton household resumed their normal course and Bob had time to catch up with his studies that had been temporarily neglected and devote himself once more to his beloved radio.

His interest in the latter was further heightened by the receipt of a letter that came one morning to his father, and whose contents Bob proceeded at once to share with his comrades.

“That talk by Mr. Bentley over the radio is fixed for to-morrow night, fellows,” he told them eagerly, as they started off for school. “Don’t make any other engagement and be sure to be on hand. Suppose you come round to my house to listen in. I’ve been tinkering on my set this last day or two, and I’ve got it tuned to the queen’s taste. And if it’s as cool to-morrow as it is to-day, old static won’t be butting in to any extent.”

“Let’s hope not,” replied Joe. “I don’t want to miss a single word.”

“Same here,” echoed Herb. “That Bentley has something to say and he sure knows how to say it.”

“It’s always worth while listening when a he-man talks,” commented Jimmy, whose imagination had been captured by the breezy personality of the bronzed forest ranger.

Promptly at eight o’clock on the following night the Radio Boys gathered at Bob’s house to listen to Mr. Bentley’s talk over the radio on radio and forest fires. Even Jimmy, who as a rule lingered long at the supper table and could usually be depended on to be at the tail end of any procession, had made an exception on this occasion, and appeared before the clock struck, although slightly out of breath.

“You’re puffing like a grampus,” remarked Herb, as he surveyed his rotund friend critically.

“I don’t know what a grampus is,” returned Jimmy; “but I wouldn’t blame him for puffing if he’d hurried through his supper the way I did. Had some fresh doughnuts, too, for dessert, but I cut short on them.”

“Cut short!” snorted Herb, in frank disbelief. “How many did you eat?”

“Only seven,” returned Jimmy, unabashed. “I’m usually good for ten.”

“What’s making your pockets bulge so?” asked Joe suspiciously.

“Those are the other three doughnuts,” explained Jimmy placidly, as he took one out and began to munch on it. “I’ve got to keep up my strength, you know.”

“Well, here’s where you grow weaker,” declared Joe, as he made a dive for Jimmy’s pocket and snatched out one of the remaining doughnuts and began to devour it.

Jimmy made a wild dive for it, which gave Herb a chance to pull the last one from his pocket, a chance of which he availed himself with neatness and dispatch.

They dodged about the room while Jimmy tried in vain to regain his treasures, which, however, soon vanished to the last crumb.

“This joint ought to be pinched,” Jimmy said, in pronounced disgust, when all hope had gone. “I didn’t think that I was coming into a nest of crooks.”

“Never mind, Jimmy,” Bob laughed. “There’s a delicious apple pie in the pantry that mother has laid aside for us, and I’ll see that your slice is twice as big as those of these two highbinders.”

Jimmy brightened up visibly at this, and further hostilities were averted.

In deference to Mr. Layton’s condition, the loud speaker was not used that night, and the boys adjusted their respective earphones and prepared to listen in to the entertainment furnished by WJZ, the signal letters of the Newark broadcasting station.

Mr. Bentley’s talk was scheduled on the program to take place at nine, and the boys were so impatient for this to begin that they did not pay as much attention as usual to the other features that preceded it. Not but what they were well worth listening to. There was a glorious violin solo played by a celebrated master, the rich notes rising and falling in wonderful bursts of melody. Then there was a talk by a star third baseman of national reputation, telling how he played the “difficult corner” and narrating some ludicrous happenings in the great game. Following this was a jazz rendition of the “Old Alabama Moon,” and then came one of Sousa’s band pieces that set feet to jigging in time with the music. WJZ was surely putting on a most interesting program.

At last came the announcement for which the Radio Boys were waiting, and they straightened up in an attitude of intent listening.

“Mr. Payne Bentley, of the United States Forest Service,” stated the announcer, “will tell us of the work done by radio in the prevention and extinction of fires in the national forests. Mr. Bentley has spent many years in this important and hazardous work, both as aviator and radio operator, and speaks with authority.”

There was a moment’s pause, and then came the clear strong voice that the boys had been waiting for and which they recognized at once.

“There’s the old boy, sure enough,” murmured Jimmy delightedly.

“S-sh,” came from the others, as they settled down to listen.

“I am not a practiced orator,” Mr. Bentley began after the customary salutation to his invisible audience, “and if my talk shall prove of any interest to you, it will be due not to the way in which I express myself but to the importance of my subject.”

After this modest opening he plunged into his theme, and for a space of perhaps twenty minutes presented an array of facts and incidents that riveted the closest attention of his great audience. At least, that was the way it affected the Radio Boys, and they had no doubt that thousands of others were listening with the same fascinated interest. Nor was this due simply to the personal attraction the speaker had for the boys. Had they not known him at all, the subject matter of his talk would have been sufficient to hold them enchained.

With a few broad strokes the speaker sketched the awakening of the national Government to the value of its forest riches and the necessity of conserving them. Uncle Sam, he said, had been in the position of a prodigal father, so rich that he believed his wealth would never be used up, therefore perfectly willing that his sons should scatter it broadcast. Why worry, when there were millions and millions of acres teeming with trees that could scarcely be numbered? So he had shut his eyes to the denuding of the forests.

But suddenly he had awakened with a shock. For he had realized after all that his wealth was not limitless. Great tracts had been stripped of their trees to such an extent that the watercourses in their vicinity had dried up or greatly diminished in volume. After the great trunks had been borne away, tons of branches had been left to dry until they became like tinder needing only a spark to fan them into a holocaust of flame that swept over thousands of acres, leaving only blasted and charred skeletons of what had been living trees. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of valuable timber had literally vanished in smoke.

Fortunately the Government had not aroused itself too late. It was not a case of locking the stable door after all the horses had been stolen. There was still enough left, with careful husbanding, to provide against national disaster. But the waste must stop right here. Reforesting must keep pace with deforesting. For every tree taken away, another must be grown to take its place. And above all, the fires that had been taking such fearful toll of our forest wealth must be prevented as far as possible. And where prevention was unavailing, the best and most improved methods of getting the fires under control and extinguishing them must be adopted and applied.

So the United States Forestry Service had come into being, and the fire loss had been immeasurably reduced. Stations had been established in great tracts of woodland from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Men with special qualities had been picked for the hard and dangerous work of forest rangers. They were the policemen of the woods, authorized to take action against many grades of human malefactors, but cautioned to be on their guard especially against the great archdemon—Fire!

In the woods as in the cities, the speaker pointed out, time is the greatest element in the curbing of fire. That is why the great engines go thundering down city streets at such tremendous speed. The loss of one minute of time may mean the loss of millions of dollars. Time to a city fireman is measured not in minutes but in seconds, and sometimes even in tenths of a second.

The same thing was true in forest fires. The alarm must be given instantly. It must be flashed to scores of villages and settlements lying in the threatened area. It must call hordes of settlers and woodmen to join in the work of getting the fire under control. How could this most effectively be done? The answer was in one word. Radio!

For Uncle Sam had come to realize that in this wonderful agency he had found the solution of his problem. He had tried many others. There had been lofty stations that had wig-wagged signals from one height to another, but this method had only a limited range and was ineffective under conditions of cloud and fog and darkness. Telegraph and telephone lines had been strung through the woods between stations, but in many cases the trees to which they had been strung and the wires themselves had been burned in the very fire that the operators had been trying to control.

But radio had none of these handicaps. It could work by night as well as by day. There were no wires to be melted. It worked in the valleys as easily as in the hills. The tiniest glint of fire, the smallest thread of smoke—and instantly the message was flung out into the ether, reaching every camp, every settlement, every party in the woods who carried their radio receiving sets with them, telling them just where the fire was starting and summoning them to help.

And it did more than that. As soon as the fire was located, aviators whose planes were equipped with radio hovered above the line of flame and gave directions by wireless to the workers below. Those on the ground, blistered and blinded by the flame and smoke against which they were waging war, could not see where the fire was spreading nor the best means to combat it. But the aviator from his lofty perch surveyed the whole scene, could call the fire fighters to the point where they were most needed, could point out the place where ditches should be cut or backfires started, and in general direct the whole campaign.

It was not to be supposed, the speaker said, that the value of radio for this purpose was instantaneously recognized. Large bodies move slowly, and the national Government was very conservative and, like the man from Missouri, wanted to be “shown.” Objections were raised that the cost of carrying and setting up the radio apparatus in the wilderness would be prohibitive. But there were men of vision who knew better and they kept pounding away until their plans were put into execution. In the end the advocates of radio won. And what that wonderful radio has saved to the United States Government has run up already into the hundreds of millions.

Many incidents, some amusing, others thrilling, connected with the Forest Service were narrated by the speaker, who then finished his remarks in this fashion:

“Before I close, let me say that if the Radio Boys of Clintonia are listening in, I am sending my regards and will soon call upon them again.”

The effect of this closing sentence on the Radio Boys was electric. They had been engrossed in the subject of the talk, and the personal twist that came at the end took them utterly by surprise. Bob jumped as though he had been shot, and Jimmy nearly fell off his chair.

“Well! what do you think of that?” exclaimed Joe, as soon as he got his breath.

“Wasn’t that dandy of the old scout?” sputtered Herb, not yet recovered from his surprise.

“Talking to hundreds of thousands and yet taking time to send a special message to us!” remarked Bob, with deep gratification.

“Radio Boys of Clintonia!” chuckled Jimmy. “Guess we’re some pumpkins, say, what?”

“How I wish we could answer back and tell him what we thought of his address,” observed Joe regretfully.

“You’ll have a chance to do that when you see him face to face,” Bob reminded him. “You remember that he said he’d call on us soon.”

“Can’t be too soon to suit me,” declared Herb emphatically.

“And that’s the man who began by saying that he wasn’t a practiced orator!” commented Bob. “Gee, I think it was one of the most eloquent things I ever heard. I wouldn’t have missed a word of it. I’ll bet that if he’d have delivered that in a crowded hall his hearers would have raised the roof.”

“He’s there with the goods all right,” agreed Joe. “And did you notice how modest he was? Not a word about his own personal adventures, but boosting the other fellows to beat the band. I tell you, that fellow’s a real man.”

“We were in luck when we got acquainted with him,” declared Bob. “And by the way, fellows, did you ever stop to think how many fine fellows we’ve met in the radio line? There’s Frank Brandon and Brandon Harvey and Payne Bentley, all of them princes.”

“Not to mention Doctor Dale,” put in Herb. “Of course we knew him before, but we never got real close to him until we took up this radio work.”

“What a treat it would be to get those four together and get them started talking about radio!” ejaculated Joe. “Maybe we wouldn’t learn something!”

“You said it,” affirmed Jimmy. “I wouldn’t want to say a word but just sit still and listen.”

There were still other numbers on the program of WJZ, but the boys were so absorbed in Mr. Bentley and his talk that they did not care for anything else that night. They sat talking it over until Joe, looking at his watch, was startled to find that it was nearly midnight.

“Guess we’d better be making tracks,” he said, reaching for his cap.

Jimmy was the only one of the visitors who did not follow his example.

“Glued to the chair?” inquired Herb flippantly. “Going to make Bob twice glad by staying all night?”

“I was thinking,” said Jimmy dreamily, “of a little word that I heard earlier in the evening. A very little word it was, but it means a lot in my young life. Only three letters. Let me see! P-i-e. Yes, that’s it. Pie. I knew I’d be able to recall it.”

“That’s a safe bet,” said Joe. “If you remembered your lessons half as well, you’d stand higher in your classes.”

Bob, recalled to his duties as host, hurried to the pantry, whence he returned bearing one of the apple pies for which Mrs. Layton was famous.

“Do you think you’d better eat anything so late at night, Jimmy?” asked Herb, with mock solicitude.

“I don’t think—I know,” returned Jimmy, with emphasis. “It may kill me, but at least I’ll die happy. But I don’t believe it will kill me. Do you remember what I did in that pie-eating contest up in the woods? Don’t forget that I’m a champion.”

Bob started to cut the pie into four equal pieces, when Jimmy intervened.

“Remember your promise, Bob,” he said. “I was to have twice as much as these crooks who robbed me of my doughnuts. Cut it into five pieces and give me two of them.”

“Your figuring is rotten, Jimmy,” declared Joe. “That would give you twice as much as either Herb or me, and so far it’s all right. But it would also give you twice as much as Bob, and that wasn’t in the bargain. He didn’t swipe one of your doughnuts.”

Jimmy looked perplexed. He was not especially strong in mathematics.

“That’s so,” he admitted. “Suppose then we cut it into six pieces. That will be two for Bob, two for me and one apiece for you crooks.”

“There again you’re wrong,” persisted the implacable Joe. “It’s all right for you to have double what we have, but where does Bob come in to have two to our one? We didn’t rob him of a doughnut.”

Now poor Jimmy was puzzled indeed. It was clear to him that if the pie were cut in five pieces, of which he had two, he would have an unfair advantage over Bob. There was no reason why he should have twice what Bob had. On the other hand if it were cut in six pieces, of which Bob had two, Bob for no reason whatever would have twice as much as Herb or Joe. How could the pie be cut so that Bob would have his fair share and no more and yet Jimmy have twice as much as either Herb or Joe? Into exactly how many equal pieces must it be divided so that justice might be done?

Perhaps some of our young readers might be puzzled to answer the question. Jimmy certainly was. So much so in fact that he made a virtue of necessity and decided to be generous.

“Oh, all right,” he said with a magnificent gesture. “Cut it into four equal pieces and let it go at that. I’ll get even with you fellows some other way.”

“How sweet of you,” replied Joe, grinning, hastening to grab his quarter before Jimmy should repent of his offer. “Only I’m not sure whether this is softness of heart or softness of brain. You’d never have done it if you hadn’t got mixed up in your figuring.”

Jimmy tried to think of some crushing retort, but by that time he had started to eat the pie, and he put his whole attention so thoroughly on the work that less important things were forgotten.

The next afternoon, as Bob was going down to his father’s store, he ran across Dr. Dale. After the doctor had made inquiries as to how Mr. Layton was progressing, Bob asked him:

“By the way, Doctor, were you listening in at WJZ last night?”

“No, I wasn’t,” replied the doctor. “Was there anything that was especially interesting?”

“We found it so,” responded Bob, and then proceeded to give an outline of the talk of the forest ranger.

“It must have been fine,” Dr. Dale commented when Bob had concluded. “I have a personal interest in forestry work for reasons that I will tell you about when I have more time. I’m glad to hear that Mr. Bentley is going to visit you, and I would like to come round and get acquainted with him.”

“I’ll tell you when he comes,” promised Bob.

“One reason that I missed his talk last night,” the doctor went on, “was that for the greater part of the evening I was listening in at WGY. Those, you remember, are the call letters of the Schenectady station. They’ve got a wonderful new contrivance there that’s going to make a sensation in the radio world when it becomes generally known.”

“One more miracle to be put down to the account of radio, I suppose,” replied Bob, with an appreciative smile.

“You might almost call it that,” replied the doctor. “Some weeks ago WGY told its audience that a new device different from the phonograph was being used to talk into the radio transmitter. But at the time they didn’t give any explanation of what the contrivance was. I suppose they wanted to test it out under all conditions before they let the public in on it. But last night they told us all about it. It’s a film that does the talking.”

“A film!” exclaimed Bob, in surprise.

“That’s just what it is,” affirmed Dr. Dale. “They showed it to Edison when he was up there the other day, and he was astonished. And anything that astonishes that wizard must be pretty good.”

“I should say so!” acquiesced Bob. “Please tell me just what it is and how it works.”

“It’s something like this,” replied the doctor. “I’ll try to give it to you as nearly as I can in the very words that were used in explaining it. The purpose of the device is to record sounds on a photographic film so that the sound may later on be exactly reproduced in ordinary telephones and loud speakers. The record is made by causing the sound waves to produce vibrations on a very delicate mirror. A beam of light reflected by this mirror strikes a photographic film which is constantly in motion.

“When the film is developed it shows a band of white with faint markings on the edges which correspond to the sound which has been reproduced. On account of the exceedingly small size of the mirror, it has been found possible to produce a sound record which includes the delicate overtones which give quality to speech and musical sounds. Do you get my meaning?”

“I can understand how the film is made,” responded Bob thoughtfully. “But after it is made, how is the sound reproduced?”

“I was coming to that,” replied the doctor. “The reproduction of the sound from the film is brought about by moving the film in front of an exceedingly delicate electrical device which produces an electromotive force that varies with the amount of light that falls upon it. By an ingenious combination of vacuum tubes, there has been produced an apparatus which responds to variations in the light falling on it with the speed of light itself or with the speed of propagation of wireless waves into space. Therefore, when this film is moved continuously in front of such a device, the device produces an electric current which corresponds very accurately to the original sound wave. This electric current may be used to actuate a telephone or loud speaker.

“When this was told to us last night, I thought that it was the announcer who was talking. But, as a matter of fact, it was the film that was talking. The voice of the announcer had first been recorded on the film and then was sent out with such accuracy that we were all fooled into believing that the announcer himself was speaking to us at first hand.”

“That certainly showed how good it was!” exclaimed Bob. “It’s nothing less than magic! It sometimes seems as though it couldn’t be real—as if radio must be a dream.”

“A dream that has come true,” answered the doctor, as he smilingly said good-by and went on his way.

The next morning Bob was on his way to school when on passing the Sterling House, the most prominent hotel in town, he caught sight of the figure of a girl on the porch that looked somewhat familiar to him. He looked again and recognized Nellie Berwick, the orphan girl to whom he and the rest of the Radio Boys had rendered such valuable service when her automobile had run wild and dashed through the window of a store.

At the same moment her eyes fell upon Bob and her face lighted up with pleasure. She waved her hand in greeting, and in a moment Bob had run up the steps and was taking her outstretched hand.

“I’m so glad to see you,” she said, and there was evident sincerity in her voice. “I was just thinking of you before you came in sight.”

“It’s pleasant to be remembered,” replied Bob.

“I have good cause for remembering,” she said, pointing across the street. “There’s the very place where I came so near to losing my life, and probably would have lost it if it hadn’t been for you.”

“I simply had the good luck to be on hand at the time,” replied Bob. “Anyone else would have done as much. But what is it that brings you to Clintonia? Are you going to stay for some time?”

“No,” she responded, “I expect to go back home this afternoon. I came to Clintonia to see your Doctor Dale, the pastor of the Old First Church. You know him, I suppose.”

“Know him!” replied Bob. “I should say I do. He’s one of the finest men that ever lived. It was only yesterday that I had a long talk with him. If I had time this morning, I’d take you up and introduce you to him.”

“Thank you just as much,” Miss Berwick answered. “I’m going to see him about the services in his church that are carried to other churches by radio. The little church in our town isn’t large enough to support a pastor and I’ve heard of so many little churches that are supplied by him that I thought we might make similar arrangements. I wanted to learn from him just what kind of receiving sets are best for the purpose and just how one can be installed.”

“He’ll be glad to give you any information that you want,” Bob assured her. “He’s doing great work by radio, and by this time there must be thousands who listen to him every Sunday. He’ll be only too pleased to have your church added to the list. And say,” he added, “when you’ve picked out your set, some of the other fellows and I will come over and rig it up.”

“That’s awfully good of you,” she said gratefully. “We’ll certainly need some help of that kind, for I don’t know any of our own people that are experts at radio.”

“We don’t call ourselves experts,” disclaimed Bob. “But I’m sure we can set your apparatus up so that you’ll have no trouble in receiving.”

“By the way,” remarked Miss Berwick, “you remember Dan Cassey?”

“Will I ever forget him?” replied Bob, and before him rose that night of storm and darkness when he had been engaged in a life-and-death struggle with the scoundrel.

“I saw him the other day,” went on Miss Berwick.

“What!” cried Bob, with a start. “You don’t mean that the rascal has escaped again?”

“Oh, no,” returned the girl. “I saw him in prison.”

“Oh!” said Bob, in great relief. “That’s better. That’s where the villain belongs. But how on earth did you happen to see him?”

“It was quite accidental,” was the reply. “I went with a friend of mine who is acquainted with the wife of the prison warden. A radio concert was to be given for the benefit of the prisoners and the warden’s wife had invited her to attend and bring any friend she liked with her. I didn’t have Cassey in mind—didn’t know, in fact, that he was in that special prison. You can imagine then how startled I was when in looking over the rows of prisoners in the prison chapel where the concert was given I recognized Cassey. He looked up and saw me too, and I never saw such a black and wicked look on any man’s face as came into his. He looked as though he would like to tear me to pieces.”

“No doubt he would if he had the chance,” replied Bob. “I imagine I wouldn’t fare very well either if he could get a hack at me. He’s bad medicine, through and through. Had you heard that he escaped once?”

“No,” replied Miss Berwick, in surprise. “Tell me about it.”

In response, Bob narrated the incident of Cassey’s escape and how he and the other Radio Boys had been instrumental in his capture.

“So you see,” he concluded, with a laugh, “Cassey must think I’m his hoodoo. I’d have a mighty slim chance if he ever had me helpless in his hands.”

But here, Bob, glancing at his watch, saw that he had barely time to reach the high school before the bell rang, and with cordial farewells they parted.

As the hours wore on the day grew unbearably hot, unseasonably so, since it was only the month of May. The day seemed excessively long, the lessons dragged, and into the minds of the boys came thoughts of cool green waters and ocean breezes.

“Oh, for Ocean Point once more!” ejaculated Joe, as at the close of the school day he wiped the perspiration from his forehead. “Say, fellows, how would it be just now to slip on our bathing suits, run down to the surf and plunge into the breakers? Oh, me, oh, my!”

“What’s the use of tantalizing a fellow?” grumbled Herb. “It’ll be at least a month or six weeks before we can get to the beach.”

“Let’s hope this weather doesn’t keep up,” remarked Bob. “But what’s the use of waiting for Ocean Point? If we can’t get the whole loaf, let’s take a slice. What do you say to taking a dip in the swimming hole down on the old Shagary? It’ll cool us off anyway, and that’s something on a day like this.”

“Just what the doctor ordered,” declared Jimmy, and his comrades murmured their approval.

It was the work of only a few minutes to reach their homes, leave their books, get their swimming trunks and towels and make for the banks of the Shagary. It was only a small stream, but the water was clear and in several places deep enough to afford excellent sport. There was one spot especially that was in high favor with the boys, because there the stream widened out so that there was some fun in racing from bank to bank. It bore the designation of the “swimming hole,” and it was there that the boys proceeded.

A hundred yards away, Bob started on a sprint.

“The last one in is a Chinaman,” he cried.

All sought to avoid having that name tacked on to him, and Herb and Joe gave Bob a genuine race, arriving with him at the river bank almost neck and neck. Jimmy was handicapped by his weight and shorter legs, and by the time he got there they had already removed some of their clothes.

“I ought to have had a twenty-yard start,” he grumbled, as he fumbled with his buttons.

In his haste, he had taken up a position too close to the edge of the bank, and as he stood on one leg while he lifted up the other to remove the leg of his trousers, he got slightly off his balance. He staggered a moment in trying to regain it, but it was no use. Over he went head first into the river, the yell of consternation that he emitted being suddenly cut short as he struck the water.

Bob, who was standing nearest him, had seen him stagger and had reached out his hand to catch him. But he had only grazed his sleeve and had all he could do to escape toppling into the water himself.

Up came Jimmy, gasping and spluttering, for as his mouth had been open when he struck the water he had swallowed a lot of it. His hair was plastered over his head, and there was a comical look of surprise and chagrin on his round face.

As he reached the bank and waded out, one leg of his trousers still clinging about him and the other trailing behind him, he presented such a ludicrous appearance that the boys fairly doubled up with laughter.

Jimmy glared at them indignantly, but this only made them laugh the more.

“That’s right, you laughing hyenas!” snorted Jimmy. “Go right ahead and cackle.”

“You’re getting your figures mixed, Jimmy,” chuckled Herb. “Hyenas don’t cackle. You’re thinking of hens.”

“I know I made a mistake,” admitted Jimmy. “I ought to have spoken of the braying of jackasses.”

“Never mind, Jimmy,” consoled Bob. “You’re not a Chinaman anyway. You weren’t the last one in.”

This seemed to bring but scant comfort to Jimmy, but he soon had plenty to occupy his mind in squeezing out his dripping clothes and spreading them in the sun to dry.

Whatever irritation he felt, however, was soon dissipated when he joined his companions, who were sporting about in the cool water. It was their first swim of the season and they enjoyed it beyond measure, diving, swimming, floating and racing until a look at the western sun told them that it was time to think about getting home.

By this time, Jimmy’s clothes were fairly dry, although they stood sadly in need of pressing. They all dressed quickly and started for the town.

Their road led for part of the way along the river bank, and they had proceeded perhaps an eighth of a mile when they heard cries of protest coming from the river mingled with mocking laughter.

At this point the road curved a little and was bordered with bushes. Joe peered through the bushes and then beckoned to his companions.

“It’s Buck Looker and his gang up to one of their usual tricks,” he whispered.

They looked and saw Buck, with Carl Lutz and Terry Mooney, sitting on the grass a little way from the river. They were laughing boisterously, as though at some huge joke.

At their feet were two suits of clothes, and in the river with the water up to their waists were standing two boys who seemed to be about ten or eleven years old. They were evidently the owners of the clothes in question and were begging Buck and his cronies to give them up.

“I told you you could have them,” Buck was saying. “All you have to do is to come and get them. But the minute you step foot on the bank, I’ll throw your shoes into the water.”

Between the offer and the threat, the small boys were in a dilemma. It was evident that they had been in the water a long time, for they were shivering and their teeth were chattering. They wanted their clothes badly, but they did not want to lose their shoes. So they stood there half whimpering with rage and cold.

The quandary in which Buck had placed his small victims seemed the very essence of humor to him and his cronies, who roared with laughter and slapped each other on the back.

At last, one of the boys in the water advanced timidly to the shore, hoping perhaps that Buck would give him back his clothes without making good his threat about the shoes. But the moment the boy stepped on the shore, Buck took up one of his shoes and hurled it into the water.

The little fellow looked after it for a moment, and then his overstrained nerves gave way and he burst into tears.

This was too much for the Radio Boys, and they burst through the bushes and came on a run toward Buck and his gang. The latter looked up in alarm at the unexpected interruption and got up quickly on their feet.

“You cowardly, hulking bully!” cried Bob. “What do you mean by treating these little fellows that way? You ought to be thrashed within an inch of your life.”

“You mind your business,” growled Buck sullenly. “Who gave you a license to butt in, anyway?”

“I’ll show you in a minute where I got my license,” replied Bob. “Don’t let him get away, fellows. Here, boys,” he called to the boys in the water, “come here and get your clothes. There’s only one more shoe going into the water, and it won’t be yours.”

The little fellows came out eagerly and then Bob turned to Buck.

“Take off your coat,” he commanded curtly, at the same time peeling off his own and throwing it to the ground.

Buck looked around for help, but Joe had ranged himself alongside of Lutz and Herb was looking after Mooney, and those worthies were not a bit inclined to mix in.

“My, but you’re slow, Buck,” remarked Bob. “You weren’t half as slow when you were picking on those youngsters. Come, get busy.”

There was no help for it, and Buck took off his coat. Then with a roar of rage he rushed at Bob, who sidestepped cleverly and caught Buck in the jaw with a blow that shook him from head to heels. Buck staggered for a moment and then rushed in to a clinch, and in an instant they were at it, hammer and tongs.

As Jimmy described it afterward it was a “peach of a scrap” while it lasted. But it did not last long. Buck was a little the older and considerably the heavier of the two, but he was no match for Bob in strength, cleverness and hard hitting. Bob met his opponent’s rushes with smashing, skilfully placed blows that soon had Buck grunting and bewildered, and at last with a long drive to the point of the jaw stretched him on the ground, where he lay half blubbering with rage and pain.

“Had enough?” asked Bob. “If not, there’s plenty more waiting for you. No trouble to show goods.”

Buck made some unintelligible answer.

“Say enough,” commanded Bob.

“Enough,” growled Buck.

“All right,” said Bob. “Now there’s only one more thing you’ve got to do. Take off one of your shoes.”

“I won’t!” shouted Buck, stung into fury.

“Then stand up and take some more,” commanded Bob. “It’s one thing or the other.”

But Buck had no stomach for any more fighting, and confronted by the two alternatives, he chose the lesser evil and took off one of his shoes.

Bob picked it up and flung it into the river, much to the delight of the two little fellows whom Buck had tormented.

“I guess that will be about all,” remarked Bob, as he put on his coat. “The next time you want to bully little chaps that can’t fight back, take a good look all around and make sure there’s no one about that may interfere with your amusement. Come along, fellows.”

They went on their way, followed by the black looks and enraged mutterings of the discomfited bully and his cronies.

“I’ve heard a good deal about poetic justice, but I never saw such a beautiful specimen as this,” chuckled Joe. “Bob, I take off my hat to you.”

“That’s all right,” laughed Herb. “But for the love of Pete, don’t take off your shoe. Shoes aren’t safe when Bob’s around.”

Buck did not turn up at school on the following day and the Radio Boys thought that they could guess the reason why.

“Don’t think his beauty was improved any by the handling he got yesterday,” laughed Jimmy. “Of course he might use the old gag that he had run against a door in the dark, but I’m afraid it wouldn’t go.”

“A door would hardly be likely to do to him what Bob did,” rejoined Joe with a grin.

“Perhaps he’s down at the river looking for that shoe of his,” chuckled Herb.

Bob himself had said nothing to the rest of his schoolmates about the fight that he had had with Buck. It was enough that he had given the latter the punishment he deserved. He had no liking for the Indian practice of scalping the dead.

Lutz and Mooney were on hand as usual, but they gave the Radio Boys a wide berth, contenting themselves with an occasional malignant glance when chance brought them in their vicinity. But later in the day Jimmy heard Lutz telling one of the schoolboys who had asked him about Buck that the latter had decided to take a little vacation and was going up into the woods for a while. The exact location of the woods was not specified, but the fact that he had gone away at all was so gratifying to Jimmy that he lost no time in carrying the welcome news to his companions.

Joe at first was inclined to be incredulous.

“Too good to be true,” he declared. “To have Buck licked one day and go away the next! Luck doesn’t come that way, like bananas—in bunches.”

“‘Though lost to sight to memory dear,’” quoted Herb.

“It will be a mighty good thing for Clintonia if he goes away and stays away,” affirmed Bob. “He’s been the worst element in the town—a pest that everybody dislikes except a few of his own kind. There doesn’t seem to be a single decent streak in his whole make-up.”

“It would be a good thing if he had taken Lutz and Mooney along with him,” remarked Jimmy.

“Oh, they don’t count,” replied Bob. “They’ll wriggle around as a snake does when its head is cut off, but that’s about all. It was Buck who thought up the low-down tricks and then relied on them to help him carry them out.”

“Well,” said Joe, “if he’s really gone we’ll mark this day with a white stone. And let’s hope that he’ll be gone for a good long while.”

And this was the general verdict of the school, especially of the younger boys whose lives Buck had made a torment by his bullying.

Nearly two weeks passed by when Mr. Layton, who had by this time fully recovered, received a letter from Mr. Bentley, stating that he would be in town the next day. Bob lost no time in conveying the information to the rest of the Radio Boys, who were quite as delighted as he was himself. Mr. Bentley’s stay was to be brief, as he was traveling on Government business, but he would stop over night anyway, and especially mentioned that he hoped to see all the Radio Boys, of whom he retained so many pleasant memories from his previous visit.

“Will we be there?” replied Joe to Bob’s question. “I’d like to see anything that would keep me away. It isn’t every day a fellow gets a chance to talk with a live wire like him.”

The rest of his friends were just as emphatic, and were at Bob’s house the following night even a little before the time appointed.

There, too, was Payne Bentley, tall and bronzed and athletic, bringing with him the breezy suggestion of a man whose life is spent largely in the open.

He greeted the boys with the heartiness that was characteristic of him, and they on their part showed their whole-souled pleasure in meeting him again.

“I’ve got a little surprise for you, fellows,” said Bob. “Here it is,” and he pushed shut a door, revealing Mr. Frank Brandon, who had been standing behind it, and who now advanced with a smile to shake hands with the surprised and delighted boys.

“Wasn’t it you, Joe, who said a little while ago that good luck didn’t come, like bananas, in bunches?” asked Bob. “Well, here’s a case that proves you’re wrong.”

“I surely was,” laughed Joe. “It was a good wind that blew them both here at the same time.”

“You see, Frank and I are old friends,” explained Mr. Bentley, as they all took chairs and settled down for a cosy chat. “We’re both in the Government service, although along somewhat different lines, and every once in a while we run across each other. I met him on the train as I was coming here and persuaded him to drop off with me and stay over night. And I didn’t have to persuade him very much when I told him whom I was going to see, for he thinks you Radio Boys are just about the real thing.”

“That’s putting it a little too strongly, I’m afraid,” replied the delighted Bob.

“Not a bit,” protested Mr. Bentley. “I was willing to agree with him after he told me of how you saved the ship on that stormy night and how you pursued and captured the rascal that tried to kill his cousin. Oh, you see I know all the deep dark secrets of your lives.

“That’s the kind of fellows we’d like to have in the Forest Service when they get old enough,” he went on. “Frank here tells me that he’s got his eye on you for the radio work, but if he doesn’t book you for that, come to me and see how you like the work of a forest ranger.”

“Speaking of forestry work,” said Bob, taking advantage of the opening to turn the conversation away from him and his chums, “I want to tell you, Mr. Bentley, how we enjoyed your talk over the radio. We thought it was splendid from start to finish.”

“And that message at the end almost knocked us off our chairs with surprise and pleasure,” put in Joe.

“So you got that, did you?” returned Mr. Bentley, smiling. “I wasn’t dead sure that you’d be listening, but put it in on a chance. Well, you see I’ve kept my word.”

“And mighty glad we are that you have,” said Herb. “The only trouble with your speech that night was that it was too short. I could have kept on listening all night.”

“I’m glad you felt that way,” replied Mr. Bentley. “I didn’t know but what I was boring my audience stiff. If I’d only been able to see the people I was talking to, I could have told something by the looks on their faces. But the dead silence and the lack of response rather got on my nerves. I’d have felt a lot more comfortable if I’d been fighting a forest fire.”

“Rather queer idea of comfort, don’t you think?” laughed Bob.

Mr. Bentley joined in the general laugh that followed Bob’s remark.

“Well, I don’t suppose it could be called exactly comfortable to have your hands blistered and your hair singed and not know whether the next minute you’re going to be alive or dead,” he admitted. “But after all there’s an excitement in fighting a fire and a sense of victory when you get the better of it that pays for all the work and pain. It’s a funny thing that when you once get into the work you don’t want to leave it. Once a forester always a forester seems to be the rule. I suppose the call of the woods to the forest ranger is like the call of the sea to the sailor.”

“I guess there’ll always be fires, so that you’ll never get out of a job,” suggested Frank Brandon.

“Right you are,” replied Mr. Bentley. “Do you know, that with all the advances that have been made in guarding against fires, more than three hundred thousand acres of woodland were burned over last year? Why, that’s equal to a strip ten miles wide reaching from New York City to Denver. The timber lost in one year would build homes for a city of four hundred thousand people.”

A gasp of astonishment came from every one of the boys.

“Did you ever!”

“Some loss!”

“What a shame to lose so much valuable timber!”

“Just what I say. Why can’t people be more careful with fire?”

“Those are mighty big figures,” commented Frank Brandon. “What are the causes of so many fires?”